The health workforce is a critical component of any health care system. There is no health care without the people who provide service. As such, the health workforce has a central role in addressing (or maintaining) health disparities.

Health disparities are significant and have worsened over the last 20 years in the United States.1 A growing body of evidence has exposed the role of health care systems in contributing to these disparities. Based on race/ethnicity, sex, sexual identity, socioeconomic status, and geography, communities face disproportionately higher disparities in access, diagnosis, and treatment, ultimately resulting in adverse health outcomes. With coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), it became clear that the inequities are experienced by health workers and those at high risk and who need care. Early challenges with limited personal protective equipment (PPE) increased risks for all health workers but also highlighted the disproportionate risk and lack of PPE for different workers, such as home health care workers who often work at or below minimum wage.2 Evidence suggests Black and other minority health workers have been at higher risk of COVID-19 infection.3

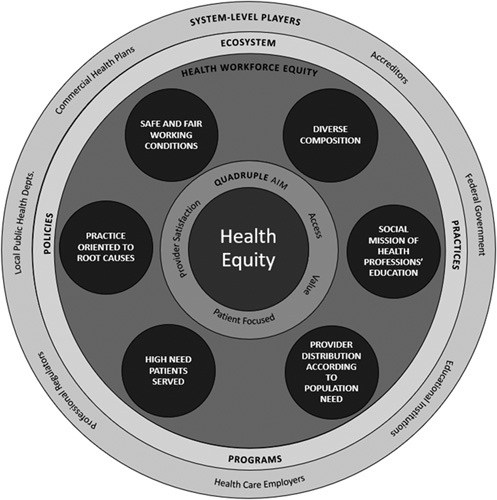

At least 6 critically important factors determine whether and what kind of care our society’s most disadvantaged sectors receive. These include: who enters the workforce (its composition); how they are educated and trained; how they are distributed geographically and by specialty; which patients and communities are served; how their practice is oriented; and, lastly, the working conditions of the entire health workforce—including home health care workers, support staff, allied health professionals, public health, physicians, nurses, and many others.

A HEALTH WORKFORCE EQUITY FRAMEWORK

In examining the health workforce’s role in advancing health equity, it is important to operationalize these domains with measurement. It is also critical that we better understand the impact of different policies and programs on health equity through each of these 6 interconnected domains. The goals of each domain are to advance: (1) a diverse composition of the health workforce; (2) the social mission of health professions’ education; (3) provider distribution according to population need; (4) high-need patients being served; (5) practice patterns that are oriented to addressing root causes of disparities; and (6) safe and fair working conditions for all members of the health workforce.

Diverse Composition

The diversity of the health workforce is critical for health equity. It has implications for access, quality, health equity, and job opportunities in low-income communities. Evidence demonstrates Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and Native American health professionals are more likely to practice in underserved communities.4,5 Students from rural backgrounds are more likely to practice in rural communities.6,7 Female physicians have been shown to practice differently than male physicians and may even achieve better clinical outcomes.8 Early evidence also suggests diversity in health professions education can increase student cultural competence and decrease implicit bias.9,10 A more diverse health workforce can bring various perspectives needed to identify and address the complex structural biases embedded in health care systems. Yet, the health professions continue to struggle with diversity, with a notable dichotomy between higher and lower-income occupations. In many of the higher income professions, the representation of Black clinicians is half that of the comparable US population. The representation of Hispanic clinicians is one third, and the diversity of health professions training programs continues to perpetuate the problem.11 In contrast, 1 in 4 home care workers is a Hispanic woman, and 1 in 3 nursing assistants is a Black woman.12 More work is needed to understand additional aspects of diversity, including socioeconomic background, sexual identity and orientation, disabilities, etc.

Social Mission of Health Professions’ Education

The social mission of a health professions school is the school’s contribution in its mission, programs, and the performance of its graduates, faculty, and leadership in advancing health equity and addressing the health disparities of the society in which it exists.13 The education pipeline plays an important role in determining the future workforce—who enters the workforce, which professions are produced, and whether graduates choose high-need specialties, practice in underserved populations, and have the skills and courage to advance health equity. Yet again, evidence demonstrates significant variation across training programs in their social mission outcomes14,15 and their engagement in social mission activities, such as interprofessional education, training in social determinants of health, and addressing racial equity and inclusion in their institutions.16–20

Provider Distribution According to Population Need

As is the case in many countries, there is a chronic maldistribution of clinicians in the United States, both in terms of specialty and geography. Studies demonstrate that primary care physician supply is associated with lower mortality and better patient outcomes.21,22 However, a rural, underserved, and high-need specialty workforce remains an ongoing challenge. While 16% of the US population lives in rural areas, just 8% of primary care clinicians and 5% of nonprimary care clinicians practice in these areas.23 As of 2021, the Health Resources and Services Administration estimates 83 million people live in primary care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs), 61 million live in dental HPSAs, and 122 million people live in mental health HPSAs.24 These areas include rural and urban communities. Moreover, the production and distribution of physicians by specialty have little to do with population needs, and this situation has been worsening. For example, since 2005, the per capita supply of primary care physicians has decreased, particularly in rural counties.25 Both aspects of maldistribution create serious barriers to access to care for underserved communities.

High-need Patients Served

Distribution of the health workforce is a necessary but insufficient attribute to address access and health equity fully. The health workforce must also serve high-need patients, including Medicaid beneficiaries, the uninsured, underinsured, and high-need populations (eg, LGBTQ+ and individuals with disabilities, complex comorbidities, homelessness, etc.). Provider acceptance rates for Medicaid patients are known to vary.26,27 Whether health care providers serve Medicaid patients at all and how much service they provide are important determinants of health care access for this low-income population. The types of services provided to less advantaged groups are equally important. For example, when primary care providers offer reproductive health and behavioral health services, they enhance access to care for historically marginalized communities.28

Practice-oriented to Root Causes

Historically, and mainly since the creation of Medicare in the 1960s, our health care system has operated under a fee-for-service paradigm that favors quantity of services, in some instances to the detriment of health outcomes, over the value of services measured in patient and population outcomes.29 Studies show that working in interdisciplinary teams, coordinating care across organizations and providers, and engaging with broader cross-sector resources to address social determinants of health are approaches that can address causes of health disparities.30 Further, developing and evaluating new and emerging models (eg, telehealth, community health workers, etc.) can ensure health care reforms advance health and health equity.

Safe and Fair Working Conditions

COVID-19 has exposed many areas of inequities in our society and the extraordinary conditions under which many frontline health workers work. This includes insufficient resources, such as PPE and staffing shortages in many settings. In addition to concerns over personal safety and staffing shortages seen during COVID-19, ongoing challenges around workload, administrative burden, and working in ethically fraught conditions contribute to health worker burnout and moral injury.31,32 For low-wage health care workers, who are disproportionately women and people of color, conditions are even worse. Support personnel in hospitals and direct care workers in skilled nursing facilities and home care, who face challenging, often physically demanding work, earn $12–$14 an hour.33 These health workers are, of course, facing the same challenges as others in their communities: housing instability, food insecurity, childcare challenges, lack of health and dental insurance, and in some cases, racism.

THE HEALTH WORKFORCE EQUITY ECOSYSTEM

The health workforce and the outlined equity domains are part of a complex ecosystem of policies, programs, and practices driven by stakeholder interests. System-level players, including federal, state, and local governments, professional regulators (eg, certifying bodies), education program accreditors, educational institutions, health care organizations (and employers), and commercial health plans, all have a stake and role in the health workforce equity (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Health workforce equity ecosystem.

Educational funding streams at the state and federal level drive priorities and health equity outcomes. For example, federal and state graduate medical education funding for residency training represents the largest public investment in health workforce development. However, the current system focuses largely on the physician workforce. It ties funding to hospitals, skewing workforce priorities to hospitals rather than community needs and creating institutional stakeholders with a strong interest in maintaining the status quo. National organizations, including the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and the National Academy of Medicine, have called for graduate medical education funding reform to address national health workforce needs.34,35 National Institutes of Health funding influences the academic culture and shows a negative correlation to social mission outcomes.14

Regulatory oversight of the professions and education programs influences health workforce equity. Federal, state, or local governments and professional regulatory bodies may regulate the health workforce. Scope of practice laws across states is an active policy area that affects how the health workforce practices. For example, states with more nurse practitioner (NP) scope of practice authority have higher per capita NPs and greater NP presence in rural and underserved communities—an important health workforce equity outcome.36 Accrediting bodies also play a role in advancing the domains of health workforce equity. The Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s introduction of diversity accreditation standards was influential and appeared to bend the curve on female and Black students, improving lagging representation in US allopathic medical schools.37

Health care payment policies and organizational rules drive workflow. These policies may include requirements associated with payment as well as the incentives of existing and new payment models. With COVID-19, several Medicare and Medicaid rules were relaxed to allow flexibility in addressing emergent health workforce needs. These include waivers to support the increased use of telehealth and expanded scope of practice (eg, allowing NPs and physician assistants to order tests and medications that previously required a physician’s order).38 Mental health parity laws increasing payment for mental health services influence the health workforce to increase mental health access. Changes and payment innovations with the Medicaid and Medicare programs will drive health care delivery and health workforce practice.

Many players ultimately determine the “who, where, how, to whom, and under what conditions” health workers deliver services. There is a need to work across the ecosystem in all 6 health workforce equity domains to advance health equity. Research in all domains, metrics, and measurements is required to understand the health workforce’s current state and its role in health disparities. Innovation, evaluation, and the scale and spread of evidence-based practices, programs, and policies are needed, and on all domains, ongoing tracking and accountability should be developed to ensure the health workforce advances health equity.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Patricia Pittman, Email: ppittman@gwu.edu.

Candice Chen, Email: cpchen@gwu.edu.

Clese Erikson, Email: cerikson@gwu.edu.

Edward Salsberg, Email: esalsberg@gwu.edu.

Qian Luo, Email: qluo@gwu.edu.

Anushree Vichare, Email: avichare@gwu.edu.

Sonal Batra, Email: Sonal@gwu.edu.

Guenevere Burke, Email: gburke@gwu.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Odlum M, Moise N, Kronish IM, et al. Trends in poor health indicators among Black and Hispanic middle-aged and older adults in the United States, 1999–2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2025134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sterling MR, Tseng E, Poon A, et al. Experiences of home health care workers in New York City during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1453–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MS, et al. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:E475–E483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodfellow A, Ulloa JG, Dowling PD, et al. Predictors of primary care physician practice location in underserved urban or rural areas in the United States: a systematic literature review. Acad Med. 2016;91:1313–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mertz E, Wides C, Kottek A, et al. Underrepresented minority dentists: quantifying their numbers and characterizing the communities they serve. Health Aff. 2016;35:2190–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, et al. The relationship between entering medical students’ backgrounds and career plans and their rural practice outcomes three decades later. Acad Med. 2012;87:493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacQueen IT, Maggard-Gibbons M, Capra G, et al. Recruiting rural healthcare providers today: a systematic review of training program success and determinants of geographic choices. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, et al. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for Medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:206–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers P, et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes. JAMA. 2008;300:1135–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Ryn MHR, Phelan S, Burgess DJ, et al. Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3546 students: a medical student CHANGES Study Report. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1748–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salsberg E, Richwine C, Westergaard S, et al. Estimation of current and future racial and ethnic representation in the US Health Care Workforce. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e213789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell S. Racial and gender disparities within the direct are workforce: five key findings. PHI; 2017. Available at: https://phinational.org/resource/racial-gender-disparities-within-direct-care-workforce-five-key-findings/. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- 13.Mullan F. Social mission in health professions education: beyond flexner. JAMA. 2017;318:122–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullan F, Chen C, Petterson S, et al. The social mission of medical education: ranking the schools. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:804–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ku L, Han X, Chen C, et al. The association of dental education with pediatric Medicaid participation. J Dent Educ. 2021;85:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greer AG, Clay M, Blue A, et al. The status of interprofessional education and interprofessional prevention education in academic health centers. Acad Med. 2014;89:799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson D, Kinney KS, Gwozdek AE, et al. Interprofessional education in US Dental Hygiene Programs: a national survey. J Dent Educ. 2015;79:1286–1294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parzuchowski A, Wright K, Lipiszko D, et al. Identifying and addressing social determinants of health in the primary care clinical training environment: a survey of the landscape. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(suppl):306–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White Coats for Black Lives. Racial Justice Report Card; 2021. Available at: https://whitecoats4blacklives.org/rjrc/. Accessed February 13, 2021.

- 20.Batra S, Orban J, Guterbock T, et al. Social mission metrics: developing a survey to guide health professions schools. Acad Med. 2020;95:1811–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang C, Stukel TA, Flood AB, et al. Primary care physician workforce and Medicare beneficiaries’ health outcomes. JAMA. 2011;305:2096–2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang C, O’Malley AJ, Goodman D. Association between temporal changes in primary care workforce and patient outcomes. Health Serv Res. 2017;52:634–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willis J Antono B Bazemore A, et al. The state of primary care in the United States: a chartbook of facts and statistics; 2020. Available at: www.graham-center.org/content/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/reports/PrimaryCareChartbook2021.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- 24.Health Resources and Services Administration. Shortage areas; 2021. Available at: https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas. Accessed February 13, 2021.

- 25.Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, et al. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:506–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holgash K, Heberlein M. Physician acceptance of new Medicaid patients: what matters and what doesn’t. Health Affairs Blog; 2019. Available at: www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190401.678690/full/. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- 27.Maxey HL, Norwood CW, Vaughn SX, et al. Dental safety net capacity: an innovative use of existing data to measure dentists’ clinical engagement in state Medicaid programs. J Public Health Dent. 2018;78:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young RA. Maternity care services provided by family physicians in rural hospitals. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saini V, Garcia-Armesto S, Klemperer D, et al. Drivers of poor medical care. Lancet. 2017;390:178–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quiñones AR, Talavera GA, Castañeda SF, et al. Interventions that reach into communities—promising directions for reducing racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2:336–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amoafo E, Hanbali N, Patel A, et al. What are the significant factors associated with burnout in doctors? Occup Med (Lond). 2015;65:117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh P, Aulak DS, Mangat SS, et al. Systematic review: factors contributing to burnout in dentistry. Occup Med (Lond). 2016;66:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wages: 31-1120 Home Health and Personal Care Aides; 2020. Available at: www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes311120.htm. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- 34.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Aligning incentive in Medicare; 2010. Available at: http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/Jun10_EntireReport.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- 35.Institute of Medicine. Graduate medical education that meets the nation’s health needs; 2014. Available at: www.nap.edu/catalog/18754/graduate-medical-education-that-meets-the-nations-health-needs. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- 36.Xue Y, Ye Z, Brewer C, et al. Impact of state nurse practitioner scope-of-practice regulation on health care delivery: systematic review. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64:71–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boatright DH, Samuels EA, Cramer L, et al. Association between the liaison committee on medical education’s diversity standards and changes in percentage of medical student sex, race, and ethnicity. JAMA. 2018;320:2267–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Trump administration makes sweeping regulatory changes to help US Healthcare System Address COVID-19 Patient Surge; 2020. Available at: www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-makes-sweeping-regulatory-changes-help-us-healthcare-system-address-covid-19. Accessed June 30, 2021.