Abstract

Objectives

To explore the experiences, and main driving forces of stigma and discrimination among COVID-19 patients, following hospital discharge, in Sri Lanka.

Study design

A qualitative study was used in order to gain insight and explore the depth and complexity of COVID-19 patients’ experiences.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted via telephone in a purposively selected sample of 139 COVID-19 patients. Participants were interviewed during the first 3 weeks following discharge from four main state hospitals that were treating COVID-19 patients during the early phase of the pandemic. Questions on stigma and discrimination were open-ended, enabling patients to provide responses about their different experiences and settings; results were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

The majority of participants were men (n = 80; 57.6%), with a mean age of 43 years (SD = 11.2). In total, up to one-third of the study participants experienced stigma related to COVID-19 and were discriminated against by the community, co-workers and healthcare workers in Sri Lanka. Social discrimination included barriers in accessing basic needs, insulting, blaming, defaming, spreading rumours and receiving no support during emergencies. Workplace discrimination included loss of jobs, not allowing re-entry and loss of earnings due to self-employment. Discrimination by healthcare workers included breaching of confidentiality, lack of respect, not providing health services and communication barriers. Discrimination has led to social isolation, not seeking help and severe psychosocial issues impacting their family relationships. Irresponsible media reporting and sensationalism of news coverage leading to breaching of privacy and confidentiality, defaming, false allegations and reporting household details without consent were perceived as the main factors underlying the views and opinions of the general public.

Conclusions

Stigma and discrimination experienced by COVID-19 patients in society, workplaces and healthcare facilities have serious negative consequences at the individual and family level. Regulations on responsible media reporting, including an effective risk communication strategy to counteract its effects, are strongly recommended.

Keywords: Stigma, Discrimination, COVID-19, Psychosocial

Introduction

After 18 months, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the globe, with >180 million cases and >3.9 million deaths reported.1 Each country heavily relies on collective actions of the society at all levels, from political leadership to the adoption of safety recommendations by the public. Despite these efforts, the pandemic has caused substantial physical, as well as mental health problems across all segments of the global population.2 , 3

Sri Lanka, a South Asian country, experienced its first wave of COVID-19 in March 2020, which was contained successfully with stringent control measures.4 Mandatory hospital admission of all confirmed patients, active surveillance in high-risk populations, home/institutional quarantine of primary contacts and establishing an effective risk communication strategy in the early phase of the outbreak5 , 6 led the country to secure a place within the top 100 safest countries during the pandemic.7 Despite this substantial achievement, adverse impacts of the pandemic on mental health, which has been reported in other countries, are also apparent in the Sri Lankan population.

Past experiences indicate that the psychological impact of a pandemic can be devastating.8 With regards to COVID-19, patients, as well as those without the disease, such as family, close associations and the society at large, have witnessed diverse mental health problems, ranging from mild forms of stress and anxiety to more severe forms, such as depression and deliberate self-harm.9, 10, 11 Studies around the world comprehensively describe how the fear of death, social isolation, loss of employment and impending or actual socio-economic hardships have resulted in disturbances to mental well-being, particularly among COVID-19 patients. In addition, stigma and discrimination shown by some individuals towards COVID-19 patients have been identified as a major cause of psychological ill-health among patients in the current pandemic.12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Stigma and discrimination towards COVID-19 patients has been reported in Sri Lanka.15 In Sri Lanka, stigma towards infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), as well as towards mental health problems, is not uncommon and has been reported among the general public, as well as healthcare professionals.18, 19, 20

Stigma refers to a set of negative beliefs that a society/a group of people hold against a condition/situation persisting in an individual.21 Health-related stigma is characterised by labelling, stereotyping and separation related to a specific disease condition, while discrimination is portrayed by the prejudicial treatment of different categories of people as a result of the stigma attached.22

In addition to the direct effects on the patients themselves, the most severe consequences of stigma and discrimination during epidemics can be at the population level. Individuals with symptoms may show reluctance in seeking medical care, coming forward for voluntary testing and revealing their contact histories, which, in turn, could invariably hamper the community participation in reducing transmission. Public engagement is especially important in the COVID-19 pandemic as it plays a pivotal role in the control of viral spread. Reduced public engagement would have a major impact on countries that have been intensely impacted, such as those in South Asia.

Although many diverse dimensions and driving forces of COVID-19-related stigma and discrimination have been identified in developed countries, these can be quite different from those existing in developing countries, owing to socio-cultural differences.23, 24, 25, 26 Currently, there is limited literature from South Asia on COVID-19-related stigma and discrimination, which had prevented an understanding of the situation and subsequently a lack of preventive measures.17 , 22 , 27 Moreover, the majority of reported studies do not have an in-depth analysis of the different aspects of the impact of stigma on patients in different settings and have paid little attention to determining the driving forces for stigma.

Therefore, we conducted this study to explore the extent of stigma and discrimination experienced by COVID-19 patients in different settings and to describe the main underlying determinants in Sri Lanka. Findings from this study aim to provide recommendations to programme managers to help plan and implement measures to prevent stigma and discrimination towards patients with COVID-19. The results and recommendations are applicable to other countries in South Asia that have similar socio-cultural backgrounds.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this qualitative study, semi-structured interviews were performed with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients who had been discharged from four state hospitals of Sri Lanka; namely, the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID), Colombo East Base Hospital (CEBH), Mulleriyawa; Base Hospital (BH), Welikanda; and BH, Homagama. These are the four main hospitals that have been designated to treat COVID-19 patients in Sri Lanka. Patients who were non-Sri Lankan and those in the medical and nursing professions were excluded from the study, as they may have been treated differently from Sri Lankan COVID-19 patients.

Study instrument and data collection

Patients eligible for the study were identified from discharge registers of the four hospitals as part of a larger study conducted on their clinical course and management in the early phase of the pandemic (March–June 2020). By using the contact details retrieved from hospital records, 182 patients were purposively selected based on the availability of contact details, sex, ethnicity and geographical region. Potential participants were approached for the study via telephone within the first 3 weeks after their hospital discharge. Those who could not be contacted after three attempts were considered to be non-respondents.

Patients providing verbal informed consent underwent semi-structured interviews via telephone on their postdischarge health status. To avoid inter-observer bias, one researcher (a female pre-intern medical graduate) conducted the interviews for all selected patients. The interviews were carried out at a time and place convenient to the participant and took approximately 20–30 min to complete.

Initially, information on their sociodemographic characteristics and new/persisting symptom profiles related to the COVID-19 infection was obtained using a structured questionnaire. Subsequently, specific information on stigma and discrimination experienced by the participants and their perceptions on underlying drivers were explored with open-ended questions. An interview guide was designed for this purpose by the research team in consultation with a consultant physician, community physician and psychologist. The face validity of the questionnaire was established with a few patients representing the target group and its content validity by another panel of experts. During interviews, the interviewer listened carefully for inconsistent or vague comments and clarified them by probe questions at the time of the interview. Each interview was recorded using a separate digital audio recorder and later transcribed into the English language.

As the participants were questioned on sensitive issues, such as stigma and discrimination, all possible measures were taken to minimise any potential psychological harm to participants. All the transcriptions were anonymised to secure the confidentiality of the respondents. The questions were worded to ensure the participant never felt that contracting the disease or any consequence was their fault. If a participant implied the need for any psychological assistance, a referral was arranged through public health teams to a consultant psychiatrist in the region. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the University of Colombo and administrative permission from the Director General of Health Services, Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka.

Data analyses

The interview transcripts were analysed using framework analysis. The transcripts, prepared in a question-by-question format, including quotes, were first read and re-read by the data collector to become familiar with the content and then translated into the English language. All transcripts were re-reviewed independently by another investigator. Three independent investigators coded the transcripts deductively to identify ideas and concepts, which belonged to a-priori themes on perceived stigma, discrimination and underlying drivers. Differences in the themes that emerged were resolved by consensus.

Results

Of the 182 patients initially contacted for the study, 139 agreed to participate in the postdischarge interviews, giving a response rate of 76.4%. There were 80 (57.6%) male and 59 (42.4%) female patients, with a mean age of 43 years (SD = 11.2). The majority of participants were of Sinhalese ethnic origin (n = 94, 67.6%), which represents the main ethnic group in the country, followed by 38 (27.3%) Muslim patients and 3 (0.02%) Tamil patients.

In total, 54 (38.8%) study participants stated that they had experienced stigma and discrimination after being diagnosed with COVID-19. Of these individuals, 64% were male (n = 35), with a mean age of 44 years (SD = 8.9). The majority were of Sinhalese ethnic origin. With regard to postdischarge health status, almost all participants stated that the physical symptoms had resolved after 2–3 weeks. However, the majority of participants complained of relatively new non-specific symptoms, such as 16 (11.5%) having difficulties with mild exertion and 15 (10.7%) experiencing body aches and myalgia even 2 weeks postdischarge. In terms of psychological symptoms, only 6 (4.3%) patients reported symptoms related to anxiety and depression.

The dimensions of stigma and discrimination experienced

Different dimensions related to stigma and discrimination were revealed. Many participants claimed that they are being labelled, set apart and are facing the loss of status and discrimination because of the stigma attached to their illness. It is interesting to note that, in addition to active cases of COVID-19, those who had recovered from the disease were frequently being discriminated. Many of the recovered patients have been stigmatised, discriminated, denied entry into the community that they were living in or workplaces, with the perception that they may still be infective and could transmit the virus to others.

The themes that emerged during the interviews on patients’ experiences of stigma and discrimination were categorised into the following three main domains:1 social discrimination by neighbours and community;2 workplace discrimination; and3 discrimination by healthcare workers.

Stigma and discrimination by neighbours/community

Under social discrimination, barriers in accessing basic needs, insulting, blaming, defaming, spreading rumours and not providing support during emergencies and social ostracism were noted. Table 1 gives a description of selected quotes from individuals.

Table 1.

Subthemes on stigma and discrimination by neighbours/community.

| Subthemes | Example of quotes |

|---|---|

| Social ostracism; insulting and blaming |

Our neighbours try to avoid me and my family as much as possible, they even tried to set fire to my house claiming that we are spreading corona; we are being isolated and we have lost our status in the society due to this disease. People label us as ‘Corona infected’ … (A 52-year-old male tourist guide) |

|

My own children are ignoring me after I got corona. Even after recovery, nobody wants to take care … I am facing financial hardships as well. (A 53-year-old married female) | |

|

When I came home after recovery from COVID-19, my neighbours said hurtful things and ignore me. Some even asked ‘why aren't you dead yet?’. They asked how I survived COVID and cancer both. I feel frustrated … (A 63-year-old married female [breast cancer patient]) | |

|

My father and mother were abused by our own villagers using harsh words and some even tried to hit them claiming that we spread corona in the village. They had even called the police and made a complaint about my family breaking quarantine laws … (A 43-year-old married male) | |

| Character defamation |

My wife and children were discriminated due to me being COVID positive. Villagers spread rumours about my wife. The nearby shops didn't allow us to visit and buy any goods. (A 40-year-old married male navy officer) |

|

Our next-door neighbour tried to change their residence because I was returning home from hospital after COVID-19. Although they had been very friendly with me before, they did not even look at us after I returned. They spread rumours claiming that I got this infection because my character is not good. I was frustrated and depressed, I could not face the society …. (A 46-year-old married housewife) |

Many participants described perceived stigma based on the reactions of the community and neighbours. Many participants felt that they were victims of social ostracism. Some participants, who were in rented houses, were even evicted due to COVID-19.

Character defamation was commonly encountered. An example of this was when the media revealed that the close contacts of several clusters of young males were traced back to commercial sex workers. This led to the public developing certain attitudes and opinions, especially about women having COVID-19.

Rejection was noted at the village and even family levels. A breach in the social network system has led to many repercussions, including social and financial insecurity. In addition to emotional abuse associated with stigma and discrimination, some responses were suggestive of physical abuse/attempted physical abuse and damage to livelihood. Table 1 gives a description of quotes from individuals.

Stigma and discrimination at the workplace

In terms of workplace discrimination, loss of jobs, not allowing re-entry and loss of earnings due to self-employment were noted. Table 2 gives a description of selected quotes from individuals.

Table 2.

Subthemes on stigma and discrimination at workplace.

| Subthemes | Example of quotes |

|---|---|

| Loss of jobs |

I was not summoned to work after full recovery even though I gave several calls requesting for a working shift, I feel desperate without a job. (A 55-year-old male security officer) |

|

I didn't receive my salary since I was contacted with Corona. Even after recovery, my employer has informed us that they will not take us back to work. (A 44-year-old female who works in a cleaning service) | |

| Loss of earnings due to self-employment |

Those who gave orders prior to COVID-19, did not return to collect their clothes. I reminded them once after recovery, they told they don't want it anymore. Even the new ones, hesitate to come for the dressmaking. Now, I am having financial difficulties as well …. (A 46-year-old self-employed female [dress maker]) |

Participants were excluded, isolated and discriminated from the workplace and community due to COVID-19, even after full recovery. Loss of earnings as a result of workplace stigma and discrimination has led to multiple social and financial problems for the affected families.

Stigma and discrimination by healthcare workers

When questioned about discrimination by healthcare workers, breaching of confidentiality, lack of respect, not providing health services and communication barriers were noted. Table 3 provides a description of selected quotes from individuals.

Table 3.

Subthemes on stigma and discrimination by healthcare workers.

| Subthemes | Example of quotes |

|---|---|

| Not providing health services |

The area Public Health Midwife has informed my wife not to bring the child for field weighing when I was at the hospital and even after recovery. (A 35-year-old male navy officer) |

| Breaching of confidentiality |

The public health inspector and Grama Niladhari [officer in charge of the smallest administrative unit of a region] scared all other villagers and discriminated me and my family; neighbours have shown a kind of displeasure towards us. (A 49-year-old male [returnee from abroad]) |

| Lack of respect |

We were treated badly at hospital; doctors and the staff are seeing and treating us from a distance; even the food used to be thrown at us, not served. (A 55-year-old female) |

In healthcare settings, stigma and discrimination were mostly observed from healthcare workers in the lower ranks of the hospital, such as hospital labourers and public health sectors from public health midwives (PHM) and public health inspectors (PHI).

Psychological impact due to stigma and discrimination

Stigmatised individuals have experienced pervasive stress, anxiety and depression. Furthermore, they experienced a sense of social worthlessness due to discrimination. Table 4 provides a description of selected quotes from individuals on psychological impact.

Table 4.

Psychological impact due to stigma and discrimination.

| Example of quotes |

|---|

|

My next-door neighbour who was very close to me before corona, is not even looking at me now. They try to avoid me and my family. I feel so worried and desperate for some company … (This patient started crying when describing her status). (A 49-year-old married female) |

|

Villagers have spread rumours about the way I contracted the disease, they claimed that I have extramarital affairs. I feel ashamed and frustrated. I can't go out as usual even after full recovery. I can't bear this anymore, sometimes I feel like ending my life. (A 30-year-old married female) |

A few participants were found to be depressed and were referred for psychiatric assistance.

The underlying drivers of stigma and discrimination

Irresponsible media reporting and sensationalism of news coverage leading to breaching of privacy and confidentiality, defaming, false allegations and reporting household details without consent were perceived as the main drivers shaping public views and opinion. The majority of patients who have experienced stigma and discrimination complained about the irresponsible behaviour of the media.

Stigmatising language (e.g. ‘COVID patient’) frequently used by the media has the power to influence attitudes and behaviour of the community. Table 5 gives a description of selected quotes from individuals on the underlying drivers of stigma and discrimination.

Table 5.

Underlying drivers of stigma and discrimination.

| Example of quotes |

|---|

|

Actions of the journalists are disgusting, appalling and stressful; worse is the social media reporting false information revealing privacy. (A 27-year-old female) |

|

My house was shown on media and even my job was stated incorrectly, It's such a shame, me and my family members are finding it very difficult to make up our minds. (A 43-year-old female) |

|

Media videoed us without our consent, they have revealed all the personnel details in news and also created false stories about the contact … (A 50-year-old male) |

Media reports highlighted the transportation of confirmed patients to designated COVID-19 hospitals and their contacts to quarantine centres. These stories, which were recorded by journalists without obtaining permission from the patients, were aired during news programmes on almost all of the local television channels. Most patients felt shame and self-rejection (internalised stigma) due to negative media publicity.

Discussion

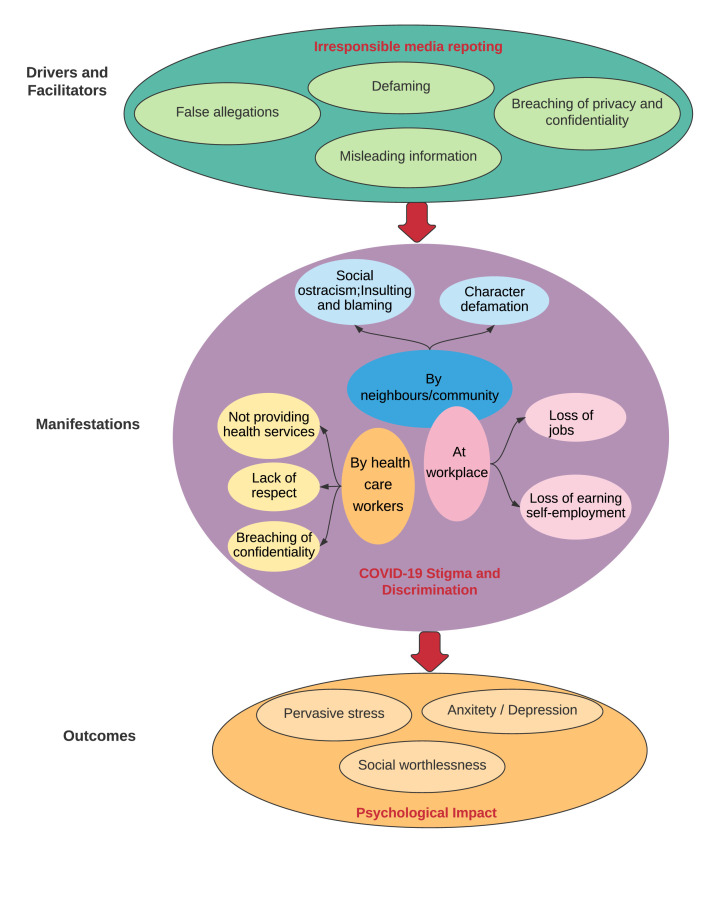

This study provides evidence on the experiences related to stigma and discrimination experienced by patients following COVID-19 infection. The extent of the problem is highlighted, and irresponsible media is identified as one of the main driving forces behind the stigma and discrimination. Fig. 1 illustrates how irresponsible media reporting has contributed to stigma and discrimination in society, the workplace and healthcare settings, and the resulting psychological impacts. The findings of the present study, as shown in Fig. 1, are in line with the ‘Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework’.28 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first in-depth study to explore stigma towards COVID-19 in Sri Lanka.

Fig. 1.

Drivers and facilitators, manifestations and outcomes of stigma and discrimination among COVID-19 patients in Sri Lanka.

The extent of stigma and discrimination related to COVID-19

According to our findings, up to one-third of patients experienced stigma related to COVID-19 and were discriminated against by the community, co-workers and healthcare workers in Sri Lanka. Social discrimination included barriers in accessing basic needs, insulting, blaming, defaming and spreading rumours; whereas, workplace discrimination included loss of jobs, not allowing re-entry and loss of earning due to self-employment. Discrimination by healthcare workers included breaching of confidentiality, lack of respect, not providing health services and communication barriers.

The current study findings further showed that all types of discrimination led to social isolation, not seeking help and complex issues affecting family relationships among patients. Especially in Sri Lanka, where the general public (particularly the poor) rely on free health services, the implications are particularly disruptive because patients who had COVID-19 may be reluctant to seek care for non-COVID-19 health problems, while individuals with probable COVID-19 may decide to conceal their disease status simply to evade stigma and discrimination. Therefore, support strategies should be put in place for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 aimed at coping with fear and anxiety and dealing with stigma, even after recovery.

Discrimination associated with COVID-19 has been documented as part of ‘witch hunt’ hysteria, in which both the infected persons and their contacts are labelled and treated differently.29 However, during the early phase of the pandemic, accusations of spreading the disease were mainly directed towards certain population groups, leading to racial discrimination. For example, verbal and physical harassment had been documented against patients of Chinese and Asian origins30 and African Americans.31 The current study also revealed similar discrimination based on class and ethnicity. At the beginning of the epidemic, individuals returning from overseas were targeted for discrimination in Sri Lanka, as the majority of COVID-19 cases were in this population group. However, over time, discrimination was directed towards specific population groups practising communal living, such as Muslim communities, from which cases and contacts were more frequently reported.32 This suggests that risk communication strategies in a country should be sensitive towards people of different classes, races and ethnicities.

Stigma and discrimination as a result of COVID-19 have been well documented among healthcare workers in Europe, the US, Africa and some parts of Asia, where they are considered as ‘disease spreaders’.33 In contrast, such discrimination among frontline healthcare workers was not apparent to a great extent in our study. This could be in line with the cultural norms of the general public in Sri Lanka, where frontline workers are respected in society as key stakeholders of the health and safety of the country.6 In particular, following the successful containment of the disease during the first wave, the doctors, nurses, public health inspectors, armed forces and police are ‘national heroes in COVID-19’ in recognition of their substantial contribution to COVID-19 control in Sri Lanka.

Media as the main driving force of stigma and discrimination

Stigma in the context of COVID-19 is mainly attributed to fear and excessive anxiety about the disease, along with a lack of proper awareness about its spread.16 In this regard, irresponsible media reporting is directly related to public views on COVID-19 patients and their contacts. For example, stigmatising language (e.g. ‘Chinese virus’, ‘Chinese syndrome’) used in printed and visual media had largely contributed to fuelling discrimination against COVID-19 among the Chinese.30 In concurrence, irresponsible media reporting and sensationalism of news coverage leading to breaching of privacy and confidentiality, defaming, false allegations and reporting household details without consent were perceived as the main drivers of discrimination by the current study participants. This perception is supported by frequent media headlines that are discriminatory towards COVID-19 patients, especially in popular social media and print media published in all major languages in the country.34, 35, 36

Media, through its various portals, contributes substantially to health awareness during an epidemic. However, its versatility as the most powerful tool for sharing information also results in it having a greater potential to disseminate exaggerated information at the same speed. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a complementary ‘infodemic’, in which waves of misinformation on the pandemic have resulted in public anxiety and fear. Such misinformation plays an important role in shaping negative attitudes of the public and ultimately leading to stigma and discrimination.37 In 2018, Heidi Larson predicted that the impact of the next major outbreak would be magnified by emotional contagion that would be digitally enabled.38 Thus, governments should develop public health policies to address the role of media portals in propagating correct information, especially during disasters.

The World Health Organisation has developed coronavirus myth-busting strategies aimed at fighting misinformation.39 However, governments worldwide have responded differently to the infodemic.34 The Sri Lankan Government has identified the importance of dissemination of accurate information regarding the disease and has introduced several risk communication strategies to allay fear and prevent erroneous assumptions on COVID-19.40 However, its implementation at the ground level has been less regulated. In this regard, the Infodemic Response Checklist is a novel tool for promoting more efficient health communication strategies to alleviate the effects of misinformation.37 Such tools should be adopted within cultural contexts while adopting a sensitive style of communication for managing public anxiety. Such communication can further strengthen societal adhesion and unity.

Furthermore, Sri Lanka lacks a strong media policy that safeguards the privacy and rights of individuals and families affected by any disaster, including COVID-19. Media policies should also adopt measures to communicate valid information through effective communication strategies between scientists and the public, thus protecting the public against infodemics.41 Social media platforms should also be strictly monitored and closely reviewed on the contents shared to ensure that false information does not promote harmful perceptions or practices.

Some limitations to this study should be noted. Patients were questioned using telephone interviews, and therefore, we were not able to retrieve as much information as in face-to-face interviews. More in-depth data collection and comprehensive understanding, body language and non-verbal expressions could not be identified and understood. In addition, stimulus material and visual aids could not be used to support the interviews.

Conclusions and recommendations

The results of this study show that stigma and discrimination experienced by COVID-19 patients in society, workplaces and healthcare facilities have serious negative consequences in Sri Lanka at both the individual and family levels. In this regard, irresponsible media reporting and sensationalism of news coverage leading to breaching of privacy and confidentiality, defaming and false allegations without consent have been identified as the main drivers of discrimination. Therefore, regulations on responsible media reporting, including an effective risk communication strategy to counteract its effects, are strongly recommended. Moreover, support strategies should be put in place for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 aimed at coping with fear and anxiety and dealing with stigma, even after recovery. Further research using mixed methods is recommended to corroborate the findings of the current study.

Author statements

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in the study for their time and valuable information provided and the hospital medical administrators for the support extended in granting permission and data collection.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Informed verbal consent was obtained from all study participants prior to data collection.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant received from the World Health Organisation, Country Office, Sri Lanka.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University . Corona Virus Resource Centre; 2021. COVID-19 dashboard by the Centre for Systems Science and Engineering.https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valeria S., Davide A., Vincenzo A. The psychological and social impact of Covid-19: new perspectives of well-being. Front Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577684. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.TRTWorld . 2020. Why Sri Lanka's response to COVID-19 is the most successful in South Asia.https://www.trtworld.com/asia/why-sri-lanka-s-response-to-covid-19-is-the-most-successful-in-south-asia-38998 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epidemiology Unit . 2021. COVID-19 national epidemiological report.https://www.epid.gov.lk/web/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.State Intelligence Services – Combatting COVID-19. https://www.president.gov.lk/.Documents/Concept-Paper-COVID-19-Ver-6-11-May-20-E.pdf. [Accessed 20 February 2021].

- 7.Koetsier J. Forbes; 2020. The 100 safest countries for COVID.https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2020/09/03/the-100-safest-countries-for-covid-19-updated/?sh=3b1ea0a7909e [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maunder Robert G. Was SARS a mental health catastrophe? Gen Hosp Psychiatr. 2020;31(4):316–317. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tucker P., Czapla C.S. Post-COVID stress disorder: another emerging consequence of the global pandemic. Psychiatr Times. 2020;38(1) https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/post-covid-stress-disorder-emerging-consequence-global-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chenthamara D., Murugan P., Robert B., et al. Social and biological parameters involved in suicide ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1178646920978243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahimeh S., Ronak M., Zeinab M.S., Renate R., Sadat B.F., Rosa A., Bentolhoda M.S. A narrative review of stigma related to infectious disease outbreaks: what can be learned in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic? Front Psychiatr. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565919. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):782. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Social stigma associated with COVID-19. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/covid19-stigma-guide.pdf. [Accessed 15 February 2021].

- 15.Bhanot D., Singh T., Sunil K., Sharad S. Stigma and discrimination during COVID-19. Mini Review. Front Publ Health. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.577018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abuhammad S., Alzoubi K.H., Khabour O. Fear of COVID-19 and stigmatization towards infected people among Jordanian people. Int J Clin Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandara G.L.W.M., Thotawaththa I.N., Ranasinghe A.W.I.P. Ground realities of COVID-19 in Sri Lanka: a public health experience on fear, stigma and the importance of improving professional skills among health care professionals. Sri Lanka J Med. 2020;29(1):4–6. doi: 10.4038/sljm.v29i1.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rathnayake R.M.U.K., Rathnayake2 T.L., Narasinghe1 U.S., Ranmuthuge R.T.S., Kumari J.U., Rathnayake R.M.J.B. Prevalence of stigma among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J Postgrad Inst Med. 2020;7(2) doi: 10.4038/jpgim.8269. E112 1–9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National STD/AIDS control programme . Ministry of Health; Sri Lanka: 2017. Zero stigma and discrimination by 2020. Stigma assessment of people living with HIV in Sri Lanka.https://www.aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/resource/stigma-assesment-plhiv-sri-lanka-2017.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernando S.M. School of Health Sciences, University of Wollongong; 2010. Stigma and discrimination toward people with mental illness in Sri Lanka.https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4571&context=theses Doctor of Philosophy thesis. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmedani B.K. Mental health stigma: society, individuals, and the profession. J Soc Work Val Ethics. 2011;8(2):41–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattacharya P., Banerjee D., Rao T.S. The “untold” side of COVID-19: social stigma and its consequences in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42(4):382–386. doi: 10.1177/0253717620935578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ransing R., Ramalho R., de Filippis R., et al. Infectious disease outbreak related stigma and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: drivers, facilitators, manifestations, and outcomes across the world. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:555–558. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Stigma and Prejudice. How to combat the rise in discrimination that has been sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-health-and-covid-19/stigma-and-prejudice. [Accessed 17 February 2021].

- 25.USAID. Disrupting COVID-19 stigma. Fact sheet. https://www.thecompassforsbc.org/sites/default/files/strengthening_tools/Stigma%20Guidance%20During%20COVID-19.pdf. [Accessed 18 February 2021].

- 26.UNICEF . 2020. COVID-19 & stigma: how to prevent and address social stigma in your community.https://www.unicef.org/sudan/covid-19-stigma-how-prevent-and-address-social-stigma-your-community [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh R., Subedi M. COVID-19 and stigma: social discrimination towards frontline healthcare providers and COVID-19 recovered patients in Nepal. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102222. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stangl A.L., Earnshaw V.A., Logie C.H., van Brakel W., Simbayi L.C., Barré I., Dovidio J.F. The health stigma and discrimination framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giovanni Sotgiu G., Dobler C.C. Social stigma in the time of coronavirus. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.02461-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu J., Sun G., Cao W., et al. Stigma, discrimination, and hate crimes in Chinese-speaking world amid Covid-19 pandemic. Asian J Criminol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11417-020-09339-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mays V.M., Cochran S.D., Barnes N.W. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukhopadhyay A. DW.com; May 2020. How Sri Lanka successfully curtailed the coronavirus pandemic.https://www.dw.com/en/how-sri-lanka-successfully-curtailed-the-coronavirus-pandemic/a-53484299 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Timothy D., Alcantara L., Siddiqi S., Barbosu M., Sharma S., Panko T., Pressman E. Risk of COVID-19-related bullying, harassment and stigma among healthcare workers: an analytical cross-sectional global study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046620. orcid.org/0000-0002-9801-4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daily Mirror . 2020. Corona virus and invasion of privacy.https://www.magzter.com/article/Newspaper/Daily-Mirror-Sri-Lanka/Coronavirus-And-Invasion-Of-Privacy Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ethics Eye. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/ethicseye/. [Accessed 23 November 2020].

- 36.Economynext . 2020. Sri Lanka's defence ministry requests media to respect privacy of COVID-19 patients.https://economynext.com/sri-lankas-defence-ministry-requests-media-to-respect-privacy-of-covid-19-patients-68796/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mheidly N., Fares J. Leveraging media and health communication strategies to overcome the COVID-19 infodemic. J Publ Health Pol. 2020;41:410–420. doi: 10.1057/s41271-020-00247-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larson H.J. The biggest pandemic risk? Viral misinformation. Nature. 2018;562(7726):309–310. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-07034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: Mythbusters. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters.

- 40.Ministry of Health and Indigenous Medicine . 2020. Sri Lanka preparedness and response plan – COVID-19.http://www.health.gov.lk/moh_final/english/public/elfinder/files/news/2020/FinalSPRP.pdf April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sholts S. 2020. Accurate science communication is key in the fight against COVID-19. 2020.https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/science-communication-covid-coronavirus [Google Scholar]