Abstract

Objectives:

Rural-urban disparities in the experiences of caregivers of older adults with advanced cancer may exist. This study examined factors associated with caregiver mastery and burden and explored whether rural-urban disparities in caregiver outcomes differed by education.

Materials and Methods:

Longitudinal data (baseline, 4-6 weeks, and 3 months) on caregivers of older adults (≥ 70) with advanced cancer were obtained from a multicenter geriatric assessment (GA) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02107443). Rurality was determined based on 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes. Caregivers’ education was categorized as > some college vs ≤ high school. Caregiver outcomes included Ryff Environmental Mastery (scored 7-35) and Caregiver Reaction Assessment (including self-esteem, disrupted schedules, financial problems, lack of social support, and health problems; each scored 1-5). Separate linear mixed models with interaction term of education and rurality were performed.

Results:

Of 414 caregivers, 64 (15.5%) were from rural areas and 263 (63.5%) completed > some college. Rurality was significantly associated with more disrupted schedules (β=0.21), financial problems (β = 0.17), and lack of social support (β = 0.11). A significant interaction between education and rurality was found, with rurality associated with lower mastery (β = −1.27) and more disrupted schedule (β = 0.25), financial problems (β = 0.33), and lack of social support (β = 0.32) among caregivers with education < high school.

Conclusion:

Our study identifies subgroups of caregivers who are vulnerable to caregiving burden, specifically those from rural areas and with lower education. Multifaceted interventions are needed to improve caregivers’ competency and reduce caregiving burden.

Keywords: Rural-urban disparities, education, geriatric assessments, environmental mastery, caregiving burden

INTRODUCTION

An informal caregiver is a relative, partner, or friend who provides assistance in multiple areas of life.1,2 Informal caregivers play essential roles in caring for the 1.7 million newly diagnosed patients with cancer and 16.9 million cancer survivors in the United States.3–5 Previous studies estimate that the 2.8 to 6.1 million caregivers of patients with cancer4 provide an average of 33 hours of service per week.6 Despite this heavy workload, the majority of caregivers (60%) receive no training for the care they provide and often lack the skills to cope with caregiving burden.

Providing care to patients with cancer poses a significant burden on caregivers’ physical,7–9 mental,7,10 and psychosocial health.7,8,10 This burden may be especially high among caregivers of older adults with cancer who require additional clinical and personal care beyond that required for their cancer and its treatments.2,5,8,11,12 Geriatric assessment (GA) uses validated patient-reported and objective measures to capture domains important to older adults with cancer such as function and cognition.2,13–15 A larger number of GA domain impairments in patients is associated with worse caregiver physical health, psychological health, and quality of life.2 Caregiver mastery measures a caregiver’s competence in managing the living environment and controlling complex external activities.16,17 Mastery has been found to be protective of caregiver health,16 but how patient GA impairments and other factors affect mastery among caregivers of older adults with cancer remains unclear.2

Rural-urban disparity in cancer is defined as the adverse differences in cancer incidence, prevalence, mortality, and survivorship among patients and their caregivers from rural areas vs urban areas.18 Addressing rural-urban disparities has recently become a policy priority of the National Cancer Institute and professional organizations.18,19 Research on rural-urban disparity has focused on patient outcomes.19–22 Rurality has been found to be associated with higher cancer incidence rates,23 worse access to cancer care,24 greater financial hardship,19,21,23 higher mortality rates,19,21,23 and poorer health post-treatment.22,25 Caregivers have generally been excluded in disparity research,18 possibly due to the lack of high-quality caregiver data. For example, caregivers are not included in electronic medical records or public data sources such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Clinical trials often do not enroll caregivers, especially those of older adults.1,14 Therefore, rural-urban disparities in caregiver mastery and burden are not well examined.

One understudied area in rural-urban disparities in cancer is the role of socioeconomic status (SES) that is usually measured by education and/or income.26 SES affects cancer outcomes including caregiving burden,27,28 but the effect of SES on outcomes of patients and caregivers living in rural vs urban areas is not well understood. Patients and caregivers from rural areas have lower education and fewer financial resources than their urban counterparts.20,25 Heterogeneity in education also exists among caregivers from the same geographic region. Understanding the effect of education (a proxy for SES) on rural-urban disparities can help identify vulnerable caregivers and guide the development of interventions and policies.

To address these knowledge gaps, this study aimed to 1) evaluate factors (including patient GA impairments) associated with caregiver mastery and caregiving burden among caregivers of older adults with advanced cancer; 2) examine rural-urban disparities in caregiver mastery and burden; and 3) explore whether rural-urban disparities in caregiver mastery and burden differed by caregiver education.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Sources

This secondary analysis utilized longitudinal data (baseline, 4-6 weeks, and 3 months) on caregivers of older patients with advanced cancer enrolled in the Improving Communication in Older Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers (COACH) study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02107443). COACH was a clustered randomized trial conducted through the University of Rochester (UR) National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) Research Base between October 2014 and April 2017.2,13 Patients and their caregivers were recruited from 31 community oncology practices affiliated with NCORP. This study was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board and the Review Board of each NCORP affiliate.

Study Cohort

COACH enrolled older patients (aged 70+) who were diagnosed with an advanced solid tumor or lymphoma, were receiving cancer treatment with palliative intent, and had at least one GA domain impairment other than polypharmacy. The study protocol defined a caregiver as a valued and trusted person in a patient’s life who is supportive in health care matters by providing valuable social support and/or direct assistive care.13 One caregiver was chosen to enroll voluntarily by the patient using the question: “Is there a family member, partner, friend, or caregiver (age 21 or older) with whom you discuss or who can be helpful in health-related matters?”1,2 Caregivers had to be 21 years of age or older, have an adequate understanding of English, and be able to provide informed consent.2 Of the 610 screened patients, 541 eligible patients (response rate of 88.7%) and 414 caregivers were recruited. Patients who enrolled with a caregiver in both arms were included in this secondary analysis (N=414 patient-caregiver dyads).

Study Procedures and Measures

Caregiver characteristics and outcomes, as well as patient characteristics, were collected. The main independent variables were caregivers’ rurality and their education level. The 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Areas Codes (RUCAs) that incorporate information on both population size and commuting time were merged with caregivers’ zip codes to define rurality.29,30 Caregivers were categorized as urban vs rural based on the Categorization C of RUCAs.29 A further breakdown of rurality was infeasible as our rural sample (N = 64) was relatively small. Education was categorized as high school graduate or less vs some college or more, a reasonable dichotomization in this study population to simplify the comparison.2

Outcome measures included the Ryff Environmental Mastery (Ryff) and Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA). Ryff measures how well caregivers manage their responsibility and environment, an indicator of caregiving competence.16,17 Ryff consists of seven individual items (e.g. In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live) with scores ranging from 1 to 5, resulting in a total score of 7-35.16 Higher numbers of Ryff indicate having a sense of mastery and competence in managing the environment and external activities including caregiving responsibilities. The Cronbach’s alpha of Ryff was 0.79 in our study, suggesting a relatively good reliability. CRA is a multidimensional instrument designed to measure a caregiver’s reactions to caregiving with a variety of chronic illnesses.31 CRA has 24 items and assesses five domains of the caregiving burden: self-esteem (e.g. I feel privileged to care for my partner.), disrupted schedule (e.g. I have to stop in the middle of my work or activities to provide care.), financial problems (e.g. It is difficult to pay for my partner.), lack of family support (e.g. It is very difficult to get help from my family in taking care of my partner.), and health problems (e.g. My health has gotten worse since I’ve been caring for my partner.). The summary score of each CRA subscale was the average of the individual items and ranged from 1-5, with higher numbers indicating more caregiving burden except for self-esteem.31,32 There is no overall score of CRA due to the multidimensional nature of the scale.

Baseline caregiver sociodemographic factors included age, race, and ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White vs other), gender (female vs male), income (<$50,000 vs ≥$50,000 or decline to answer), marital status (married or cohabiting partnership vs other), employment status (employed vs other), relationship with patient (spouse or cohabiting partner vs son/daughter vs other), and caregiver comorbidity (yes vs no) (Table 1).2,13 Caregiver comorbidity was assessed via the Older Americans Resources and Services Questionnaire and defined as having at least three comorbidities or one comorbidity with great interference with activities.33 Baseline patient clinical characteristics were also obtained: cancer type (gastrointestinal vs lung vs other), cancer stage (III vs IV vs other), chemotherapy treatment (yes vs no), and GA impairments.2,13 Patient GA consisted of eight domains derived from validated tools: physical performance, functional status, comorbidity, cognition, nutrition, social support, polypharmacy, and psychological status.2,13,15 The total number (1-8) of GA domain impairments was calculated.13

Table 1.

Descriptive Results of Baseline Caregiver Characteristics and Caregiver Outcomes by Rurality

| Variables | All Caregivers (N=414) |

Urban (N=350) |

Rural (N=64) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N(%) or Mean(SD) |

N(%) or Mean(SD) |

N(%) or Mean(SD) |

|

| Caregiver Characteristics+ | |||

|

| |||

| Age | 66.5 (12.5) | 66.4 (12.2) | 66.9 (13.7) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 369 (89.1%) | 310 (88.6%) | 59 (92.2%) |

| Female | 310 (74.9%) | 264 (75.4%) | 46 (71.9%) |

| Education ≥ some college‡ | 263 (63.5%) | 232 (66.3%) | 31 (48.4%) |

| Incomes ≥ $50,000 or decline to answer | 259 (62.6%) | 221 (63.1%) | 38 (59.4%) |

| Married or cohabiting partnership | 335 (80.9%) | 282 (80.6%) | 53 (82.8%) |

| Employed | 105 (25.4%) | 91 (26.0%) | 14 (21.9%) |

| Relationship with patient | |||

| Spouse and cohabiting partner | 276 (66.7%) | 231 (66.0%) | 45 (70.3%) |

| Son/daughter | 94 (22.7%) | 83 (23.7%) | 11 (17.2%) |

| Other | 41 (9.9%) | 34 (9.7%) | 7 (10.9%) |

| ComorbidityŠ | 162 (39.1%) | 134 (38.3%) | 28 (43.8%) |

|

| |||

| Caregiver outcomes | |||

|

| |||

| RYFF environmental mastery(7-35)§ | 27.6 (4.6) | 27.6 (4.6) | 27.1 (4.6) |

| Caregiver Reaction Assessment (1-5) | |||

| Self-esteem§ | 4.5 (0.5) | 4.5 (0.5) | 4.5 (0.5) |

| Disrupted schedule¶ | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.7) |

| Finance problems¶ | 2.0 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.9) |

| Lack of social support¶ | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.7) |

| Health problems¶ | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.6) |

Note: SD=standard deviation;

Three caregivers had missing demographic data;

P ≤ 0.05 when comparing differences between urban and rural caregivers using t-tests for continuous variables, and Chi-square tests for binary variables;

Comorbidity is defined as having 3 comorbidities or 1 comorbidity with great interference;

Higher number indicates better caregiver outcome;

Higher number indicates worse caregiver outcome.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted to examine caregiver characteristics, caregiver outcomes, and patient clinical and GA information. Bivariate analyses were used to compare characteristics of caregivers and patients by rurality. Separate multivariable regressions were performed to examine rural-urban differences in caregiver mastery and burden adjusted for caregiver and patient characteristics. To account for the longitudinal and nested data structure, linear mixed models (LMMs) with practice site as a random effect were performed, assuming an unstructured working correlation that allows up-to 3 observations per caregiver. Caregivers who died or lost to follow-up were included in the final models as long as they had outcome measures at one time point; about 74% caregivers completed the 3-month assessment. Final fixed effects included caregiver rurality, education, age, gender, relationship with patient, and caregiver comorbidity, as well as patient cancer type and number of geriatric impairments.2,34,35 Study arm was not included, because the primary study demonstrated that GA intervention did not change caregiver mastery or burden and study arm was statistically insignificant in LMMs.13 Caregiver race and marital status as well as patient cancer stage and chemotherapy treatment were not associated with caregiver outcomes in the models and thus were excluded.2 Income was not adjusted because of its strong collinearity with education (χ2= 38.7, P < 0.01). Patient demographics were excluded as they were highly correlated with caregiver characteristics.2 To evaluate the moderation effect of education on rurality, the interaction term of caregiver education and rurality was added into the models; marginal effects of rurality by education were computed after LMMs. Due to the exploratory nature of this study, we considered an effect size of 0.2 (i.e., the coefficient estimate is 0.2 of the standard deviation of the outcome measure) to be clinically meaningful.36

All statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata 16.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX), with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline caregiver characteristics were reported in previous studies (N=414).2,13 Notably, caregivers’ average age was 66.5 years; most caregivers were Non-Hispanic White (89.1%), female (74.9%), and had completed some college or above (63.5%) (Table 1).2 The majority of caregivers reported incomes ≥ $50,000 or declined to answer (62.6%), and 39.1% had comorbidity.2 Over one quarter of caregivers were employed (25.4%), and 64 (15.5%) were from rural areas. No significant differences were observed in characteristics between caregivers from rural and urban areas, except that caregivers from rural areas had lower education levels (P = 0.01).

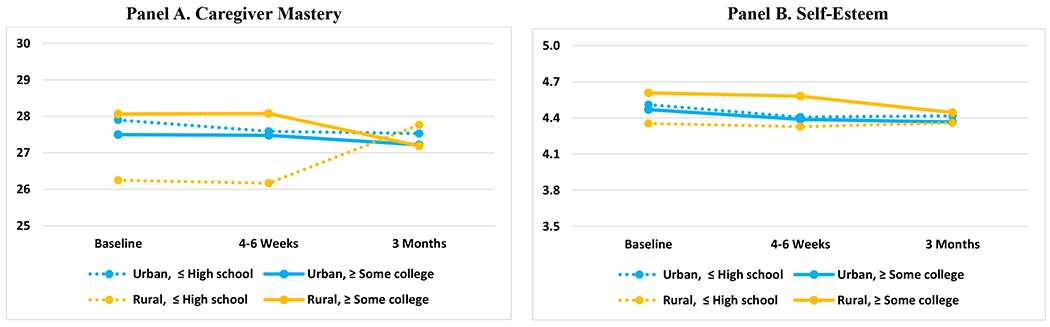

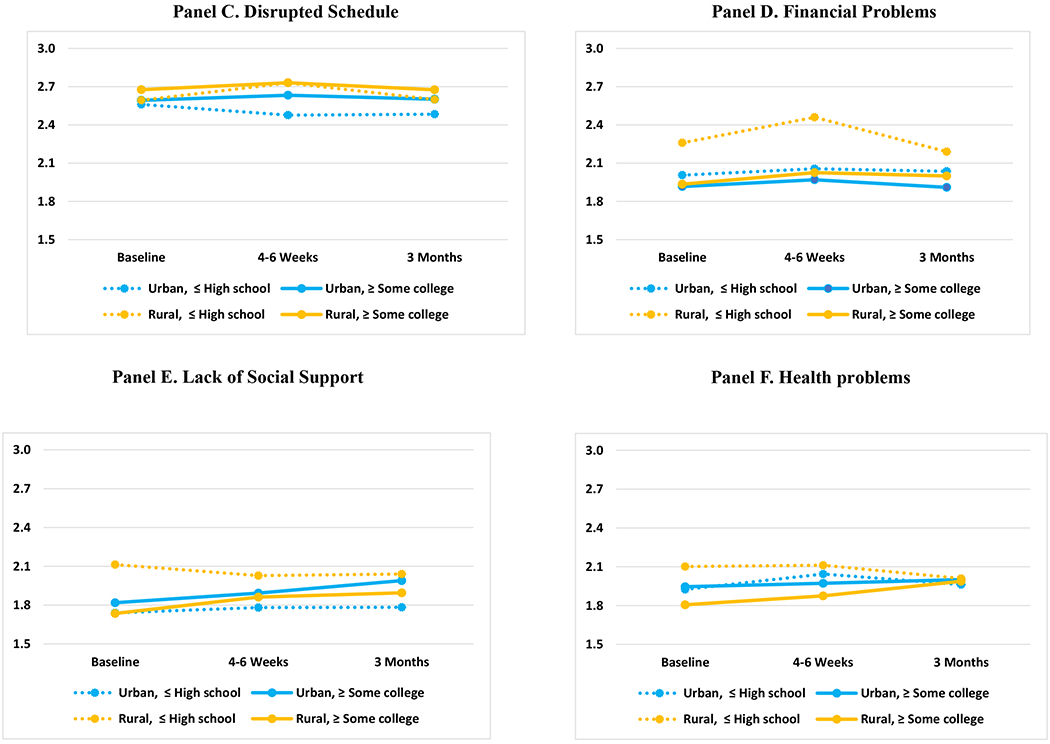

At baseline, caregivers averaged 27.6 in Ryff caregiver mastery. Caregivers reported an average 4.5 in self-esteem, 2.6 in disrupted schedule, 2.0 in financial problems, 1.8 in lack of social support, and 1.9 in health problems (Table 1). No significant differences in mastery or CRA at baseline between caregivers from rural vs urban areas were detected in bivariate analyses (all P > 0.10). Figure 1 presents the time trends of caregiver outcomes over the study period by education and rurality. Overall, caregivers with education ≥ some college or from urban areas reported higher mastery and self-esteem and less problems in CRA subscales. Caregivers from rural areas with education ≤ high school reported the lowest mastery and self-esteem, but the greatest problems in finance, social support, and health.

Figure 1.

Trends of Caregiver Mastery and Caregiving Burden by Education and Rurality

Table 2 presents patient characteristics by rurality for 414 patients who enrolled with a caregiver in the COACH trial. The majority had gastrointestinal and lung cancers (51.2%), stage IV cancer (88.2%), and were receiving chemotherapy (68.1%).2–13 Compared to patients from urban areas, patients from rural areas had fewer GA domain impairments (4.1 vs 4.6) and were less likely to have impaired nutrition (64.6% vs 51.6%) (both P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Descriptive Results of Baseline Patient Characteristics by Rurality

| Variables | All Patients (N=414) |

Urban (N=350) |

Rural (N=64) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N(%) or Mean(SD) |

N(%) or Mean(SD) |

N(%) or Mean(SD) |

|

| Geriatric Assessment impairment | |||

| Number of impairments (1-8)‡ | 4.5 (1.5) | 4.6 (1.5) | 4.1 (1.6) |

| Polypharmacy | 350 (84.5%) | 299 (85.4%) | 51 (79.7%) |

| Cognition | 144 (34.8%) | 125 (35.7%) | 19 (29.7%) |

| Nutrition‡ | 259 (62.6%) | 226 (64.6%) | 33 (51.6%) |

| Physical performance | 389 (94.0%) | 331 (94.6%) | 58 (90.6%) |

| Functional status | 254 (61.4%) | 221 (63.1%) | 33 (51.6%) |

| Comorbidity | 263 (63.5%) | 224 (64.0%) | 39 (60.9%) |

| Psychological status | 112 (27.1%) | 94 (26.9%) | 18 (28.1%) |

| Social support | 91 (22.0%) | 77 (22.0%) | 14 (21.9%) |

| Cancer type + | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 103 (24.9%) | 84 (24.0%) | 19 (29.7%) |

| Lung | 109 (26.3%) | 94 (26.9%) | 15 (23.4%) |

| Other | 201 (48.6%) | 171 (48.9%) | 30 (46.9%) |

| Cancer stage+ | |||

| Stage III | 35 (8.5%) | 30 (8.6%) | 5 (7.8%) |

| Stage IV | 365 (88.2%) | 309 (88.3%) | 56 (87.5%) |

| other | 13 (3.1%) | 10 (2.9%) | 3 (4.7%) |

| Chemotherapy + | 282 (68.1%) | 235 (67.1%) | 47 (73.4%) |

Note: SD=standard deviation;

One patient did not provide clinical information.

P ≤ 0.05 when comparing differences between urban and rural caregivers using t-tests for continuous variables, and Chi-square tests for binary variables;

Multivariable regression results are presented in Table 3 and marginal effects are presented in Table 4. An increasing number of patient GA domain impairments was significantly associated with lower mastery (β = −0.55) and self-esteem (β = −0.04) as well as more disrupted schedule (β = 0.19), financial problems (β = 0.07), lack of social support (β = 0.06), and health problems (β = 0.10). Caregivers with education ≥ some college were less likely to report financial problems (β = −0.18). Female caregivers were significantly more likely to report lower self-esteem (β = −0.11) and more disrupted schedule (β = 0.18) and health problems (β = 0.30). Compared to caregivers from urban areas, caregivers from rural areas reported similar mastery, self-esteem, and health problems but more disrupted schedules (β = 0.21), financial problems (β = 0.17), and lack of social support (β = 0.11) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Multivariable Regressions to Examine Factors Associated with Caregiver Mastery and Caregiving Burden

| Variables | Caregiver Mastery |

Self-Esteem | Disrupted Schedule |

Financial Problems |

Lack Of Social Support |

Health Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) = 27.5 (4.7) | Mean (SD) = 4.4 (0.5) | Mean (SD) = 2.6 (0.9) | Mean (SD)= 2.0 (0.8) | Mean (SD)= 1.9 (0.7) | Mean (SD)= 2.0 (0.7) | |

|

| ||||||

| (Coef, 95% CI) |

(Coef, 95% CI) |

(Coef, 95% CI) |

(Coef, 95% CI) |

(Coef, 95% CI) |

(Coef, 95% CI) |

|

|

Main variables of interest

| ||||||

| Rural (ref: urban) | −1.27** | −0.09 | 0.25** | 0.33*** | 0.32*** | 0.15* |

| (−2.40 - −0.14) | (−0.22 - 0.04) | (0.04 - 0.45) | (0.12 - 0.54) | (0.14 - 0.50) | (−0.00 - 0.31) | |

| Education ≥ some college (ref: ≤ high school) | −0.21 | −0.06 | 0.16*** | −0.14** | 0.09* | 0.06 |

| (−0.86 - 0.44) | (−0.13 - 0.02) | (0.04 - 0.28) | (−0.25 - −0.02) | (−0.01 - 0.19) | (−0.03 - 0.15) | |

| Interaction of rurality and education | 1.44* | 0.18** | −0.06 | −0.25* | −0.32*** | −0.18 |

| (−0.10 - 2.97) | (0.01 - 0.36) | (−0.34 - 0.21) | (−0.53 - 0.02) | (−0.56 - −0.09) | (−0.39 - 0.03) | |

|

| ||||||

|

Caregiver characteristics

| ||||||

| Age | 0.06*** | −0.00* | −0.00 | −0.01*** | −0.01** | −0.00 |

| (0.03 - 0.10) | (−0.01 - 0.00) | (−0.01 - 0.00) | (−0.02 - −0.01) | (−0.01 - −0.00) | (−0.01 - 0.00) | |

| Female (ref: male) | −0.44 | −0.11*** | 0.18*** | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.30*** |

| (−1.11 - 0.22) | (−0.18 - −0.03) | (0.06 - 0.29) | (−0.16 - 0.08) | (−0.08 - 0.12) | (0.21 - 0.40) | |

| Relationship (ref: spouse or cohabiting partner) | ||||||

| Son/Daughter | −0.08 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.17** | −0.05 |

| (−1.05 - 0.89) | (−0.15 - 0.06) | (−0.20 - 0.15) | (−0.18 - 0.16) | (0.02 - 0.32) | (−0.18 - 0.09) | |

| Other | 2.06*** | −0.11* | −0.31*** | −0.04 | 0.17** | −0.16** |

| (1.00 - 3.11) | (−0.23 - 0.00) | (−0.49 - −0.12) | (−0.22 - 0.15) | (0.01 - 0.34) | (−0.31 - −0.02) | |

| Comorbidity | −1.32*** | −0.06* | 0.07 | 0.19*** | 0.22*** | 0.30*** |

| (−1.91 - −0.73) | (−0.13 - 0.00) | (−0.04 - 0.17) | (0.08 - 0.29) | (0.13 - 0.31) | (0.22 - 0.38) | |

|

| ||||||

|

Patient characteristics

| ||||||

| Number of geriatric impairments | −0.55*** | −0.04*** | 0.19*** | 0.07*** | 0.06*** | 0.10*** |

| (−0.73 - −0.36) | (−0.06 - −0.02) | (0.15 - 0.22) | (0.04 - 0.11) | (0.03 - 0.08) | (0.08 - 0.13) | |

| Cancer type (ref: Gastrointestinal) | ||||||

| Lung | −0.94** | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.11** |

| (−1.73 - −0.15) | (−0.05 - 0.13) | (−0.15 - 0.13) | (−0.19 - 0.09) | (−0.13 - 0.11) | (0.00 - 0.22) | |

| Other | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.14** | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.02 |

| (−0.71 - 0.65) | (−0.13 - 0.02) | (−0.26 - −0.02) | (−0.18 - 0.06) | (−0.10 - 0.11) | (−0.11 - 0.08) | |

| Assessment (ref=baseline) | ||||||

| 4-6 weeks | −0.17 | −0.08** | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| (−0.81 - 0.47) | (−0.15 - −0.01) | (−0.09 - 0.14) | (−0.03 - 0.20) | (−0.03 - 0.16) | (−0.02 - 0.15) | |

| 3 months | −0.35 | −0.09** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.13** | 0.07 |

| (−1.01 - 0.32) | (−0.17 - −0.02) | (−0.10 - 0.14) | (−0.09 - 0.14) | (0.03 - 0.23) | (−0.02 - 0.16) | |

| Intercept | 26.93*** | 5.06*** | 1.80*** | 2.67*** | 1.71*** | 1.12*** |

| (23.99 - 29.86) | (4.73 - 5.39) | (1.28 - 2.33) | (2.15 - 3.20) | (1.25 - 2.17) | (0.72 - 1.53) | |

| Observations | 1,051 | 1,066 | 1,065 | 1,064 | 1,062 | 1,067 |

| Unique Caregivers | 400 | 412 | 412 | 412 | 412 | 412 |

| Number of groups | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

Note: SD= standard deviation,CI=confidence interval;

Regressions were based on the linear mixed models adjusted for practice site as random effects, using restricted maximum likelihood, assuming an unstructured working correlation;

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1.

Table 4.

Marginal Effect of Rurality on Caregiver Mastery and Caregiving Burden by Education

| Variables | Caregiver Mastery |

Self-Esteem | Disrupted Schedule |

Financial Problems | Lack of Social Support |

Health Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) = 27.5 (4.7) | Mean (SD) = 4.4 (0.5) | Mean (SD) = 2.6 (0.9) | Mean (SD)= 2.0 (0.8) | Mean (SD)= 1.9 (0.7) | Mean (SD)= 2.0 (0.7) | |

|

| ||||||

|

Main effect

| ||||||

| Rural (ref: urban) | −0.34 | 0.03 | 0.21*** | 0.17** | 0.11** | 0.04 |

| (−1.18 – 0.49) | (−0.07 – 0.12) | (0.06 – 0.36) | (0.01 – 0.32) | (−0.02 – 0.24) | (−0.07 – 0.15) | |

| Education ≥ some college (ref: ≤ high school) | ||||||

| 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.15* | −0.18*** | 0.03 | −0.03 | |

| (−0.58 – 0.61) | (0.09 – −0.04) | (0.04 – 0.26) | (−0.28 – −0.07) | (−0.06 – −0.13) | (−0.05 – 0.12) | |

|

| ||||||

|

Interaction effect

| ||||||

| Rural (ref: urban) | ||||||

| ≤ High school | −1.27** | −0.10 | 0.25** | 0.33*** | 0.32*** | 0.15* |

| (−2.40 – −0.14) | (−0.22 – 0.04) | (0.04 – 0.45) | (0.12 – 0.54) | (0.14 – 0.50) | (0 – 0.31) | |

| ≥ Some college | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.18* | 0.07 | 0 | −0.03 |

| (−0.94 – 1.27) | (−0.03 – 0.22) | (−0.01 – 0.38) | (−0.12 – 0.27) | (−0.17 – 0.17) | (−0.18 – 0.12) | |

| P value of interaction | ||||||

| term | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07 | <0.01 | 0.10 |

Notes: SD= standard deviation;

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1;

Marginal effects were calculated from the linear mixed models in Table 3;

Models adjusted for caregiver age, gender, relationship, comorbidity, and patient cancer type and number of geriatric impairments, time fixed effect, and practice site random effect;

P value measures the significance of the interaction term of rurality and education based on the linear mixed models.

Significant interaction effects of education and rurality were found in self-esteem (P = 0.04), disrupted schedule (P = 0.02), and lack of social support (P < 0.01); marginally significant interaction effects were found in caregiver mastery (P = 0.07) and health problems (P = 0.10) (Table 4). Rurality was associated with lower mastery among caregivers with education ≤ high school (β = −1.27), but not with education ≥ some college. The overall association of rurality and self-esteem was insignificant, but the coefficients differed in the subgroups with education ≤ high school vs ≥some college (both P > 0.05). Rurality was associated with more disrupted schedule (β = 0.25), financial problem (β = 0.33), and lack of social support (β = 0.32) among caregivers with education ≤ high school but not with ≥ some college. Neither rurality nor the interaction term of rurality and education was associated with health problems.

DISCUSSION

In a national sample of caregivers of older patients with advanced cancer, this study demonstrated that a greater number of patient GA domain impairments was associated with lower caregiver mastery and higher caregiving burden. Caregivers with lower education reported lower mastery and higher burden. Compared to caregivers in urban areas, those in rural areas reported more caregiving burden, specifically due to disrupted schedules, financial problems, and lack of social support. Education moderated the association of rurality with self-esteem, disrupted schedule, and lack of social support. Rural residency was associated with lower mastery and more disrupted schedule, financial problems, and lack of social support among caregivers with education ≤ high school but not among those with education ≥ some college.

Older patients with cancer have a higher prevalence of comorbidities than their younger and non-cancer counterparts.5,37,38 Co-existing health problems of one member of the patient-caregiver dyad have the potential to hurt the wellbeing of the other.2,4,34,35 Higher numbers of patient GA domain impairments are associated with reduced caregiver physical health, depression, and diminished quality of life.2,5,11,39,40 Our findings further indicate that patient GA domain impairments were associated with lower mastery and higher caregiving burden. Clearly, strategies are needed to support caregivers who care for vulnerable older patients.

Rural-urban disparities in disrupted schedules, financial problems, and lack of social support found in our study emphasize the vulnerability of caregivers in rural areas. Rurality has been linked to lower employment rates, education, and income.41 Caregivers in rural areas also report fewer workplace benefits such as telecommuting (10% vs 25%), employee assistance programs (15% vs 26%), and paid leave (18% vs 34%).44 In addition, they are more socially and geographically isolated, contributing to the lack of social support and greater disruption in their schedules.42 Together, these factors can lead to a higher caregiving burden.

A major contribution of this study is the finding that SES measured by education moderates the negative effects of rurality on caregiver mastery, self-esteem, disrupted schedule, and financial problems. The effects of rurality on caregiving burden were observed mainly among those with education ≤ high school, suggesting health disparities between rural vs urban settings may be partially explained by socioeconomic variables.27 Higher education level is associated with better income, which may allow caregivers in rural areas to access necessary resources even if they are from a relatively isolated and resource-limited area. Poor education has previously been shown to be associated with more unmet social support needs in older patients with cancer,20,43 and our study demonstrated a similar association for caregivers. Higher education levels may also provide better coping skills or knowledge in managing caregiving activities, leading to lower burden. Interventions to improve caregiving training and financial planning are needed, along with psychosocial interventions to improve self-esteem and coping skills for this vulnerable group of caregivers.11,44

Caregivers in rural areas with education ≤ high school were more likely to experience disruptions in their schedules than their urban counterparts. About one quarter of caregivers were still employed while providing care. Those living in rural areas may have longer commuting times and fewer workplace benefits such as telecommuting and paid leave, which leads to work schedule disruptions.45,46 The disruptions might be stronger among caregivers with low education whose work requires more in-person presence. Interventions in the form of employer-based assistance initiatives such as working from home for caregivers or through telemedicine for patients’ cancer treatment to reduce travel time may help this subgroup of caregivers with low education living in rural areas.

The strengths of our study include a large sample of older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers who were recruited from 31 community oncology practices. A multidimensional measure of mastery and burden was utilized in this study. Some limitations need to be acknowledged. Caregivers included were mostly non-Hispanic White with high levels of education and largely from urban areas; they do not represent the entire US population. The magnitudes of the associations between rurality and outcome measures observed in this study are relatively small (around ¼ - ½ of the SDs). We considered those coefficients to be meaningful given the overall small variation in the outcome measures and minimum changes over time.36 More work is needed to established meaningful cutoffs for Ryff and CRA.

In conclusion, our study identified subsets of caregivers who were vulnerable to caregiving burden. Caregivers of older patients with advanced cancer from rural areas reported more caregiving burden, and education moderated the relationship of rurality and caregiver mastery and caregiving burden. Additional studies are needed to better understand the challenges faced by caregivers of older adults with cancer, especially those from rural areas and with low education. Multifaceted interventions targeted at the patient, caregiver, physician, and healthcare system are needed to improve caregiving competency and reduce caregiving burden.

Acknowledgments:

The work was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program contract (4634 to SGM), the National Cancer Institute at the National Institute of Health (UG1 CA189961 to KM; K99CA237744 to KPL; KL2TR001999 to NG), the National Institute of Aging at the National Institute of Health (K24 AG056589 to SGM; R33 AG059206 to SGM), and the Wilmot Research Fellowship Award (grant number is not applicable; to KPL). This work was made possible by the generous donors to the Wilmot Cancer Institute (WCI) Geriatric Oncology Philanthropy Fund. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors, do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee. We acknowledge Susan Rosenthal, MD, for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Kah Poh Loh serves as a consultant to Pfizer and Seattle Genetics. Dr. Allison Magnuson reports an honorarium for an educational lecture provided at the American Society of Radiation Oncology 2020 Annual meeting. All other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilmore NJ, Canin B, Whitehead M, et al. Engaging older patients with cancer and their caregivers as partners in cancer research. Cancer. 2019;125(23):4124–4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehoe LA, Xu H, Duberstein P, et al. Quality of Life of Caregivers of Older Patients with Advanced Cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(5):969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Applebaum AJ, Breitbart W. Care for the cancer caregiver: a systematic review. Palliat Support Care. 2013;11(3):231–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Applebaum AJ. Care for the Cancer Caregiver. ASCO;2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ornstein KA, Liu B, Schwartz RM, Smith CB, Alpert N, Taioli E. Cancer in the context of aging: Health characteristics, function and caregiving needs prior to a new cancer diagnosis in a national sample of older adults. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(1):75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yabroff KR, Kim Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4362–4373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(10):1013–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girgis A, Lambert S, Johnson C, Waller A, Currow D. Physical, psychosocial, relationship, and economic burden of caring for people with cancer: a review. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(4):197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeong A, Shin D, Park JH, Park K. Attributes of caregivers’ quality of life: A perspective comparison between spousal and non-spousal caregivers of older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(1):82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadambi S, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Garg T, et al. Social support for older adults with cancer: Young International Society of Geriatric Oncology review paper. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(2):217–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, et al. Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(18):2927–2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohile SG, Epstein RM, Hurria A, et al. Communication With Older Patients With Cancer Using Geriatric Assessment: A Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial From the National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program. JAMA Oncol. 2019;6(2):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2326–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohile SG, Velarde C, Hurria A, et al. Geriatric Assessment-Guided Care Processes for Older Adults: A Delphi Consensus of Geriatric Oncology Experts. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(9):1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryff CD. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(1):10–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(4):719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polite BN, Adams-Campbell LL, Brawley OW, et al. Charting the Future of Cancer Health Disparities Research: A Position Statement From the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Cancer Institute. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(26):3075–3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy AE, Vanderpool RC, Croyle RT, Srinivasan S. An Overview of the National Cancer Institute’s Initiatives to Accelerate Rural Cancer Control Research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(11):1240–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zahnd WE, Davis MM, Rotter JS, et al. Rural-urban differences in financial burden among cancer survivors: an analysis of a nationally representative survey. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2019;27(12):4779–4786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zahnd WE, James AS, Jenkins WD, et al. Rural-Urban Differences in Cancer Incidence and Trends in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(11):1265–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDougall JA, Banegas MP, Wiggins CL, Chiu VK, Rajput A, Kinney AY. Rural Disparities in Treatment-Related Financial Hardship and Adherence to Surveillance Colonoscopy in Diverse Colorectal Cancer Survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(11):1275–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, Srinivasan S, Croyle RT. Making the Case for Investment in Rural Cancer Control: An Analysis of Rural Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Funding Trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(7):992–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X, Wang D, Demidenko E, Goodman D. Geographic access to cancer care in the US. Cancer. 2008;112(4):909–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural-urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1050–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adler NE, Ostrove JM. Socioeconomic status and health: what we know and what we don’t. Annals of the New York academy of Sciences. 1999;896(1):3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Connor JM, Sedghi T, Dhodapkar M, Kane MJ, Gross CP. Factors Associated With Cancer Disparities Among Low-, Medium-, and High-Income US Counties. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berndt SI, Carter HB, Schoenberg MP, Newschaffer CJ. Disparities in treatment and outcome for renal cell cancer among older black and white patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(24):3589–3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. Using RUCA Data. 2017; http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-uses.php.Accessed 11/26, 2017.

- 30.Hart G Rural-Urban Commuting Areas Codes (RUCAs) 2010. 2014; https://ruralhealth.und.edu/ruca.Accessed August 1, 2018.

- 31.Nijboer C, Triemstra M, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R, van den Bos GAM. Measuring both negative and positive reactions to giving care to cancer patients: psychometric qualities of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA). Social Science & Medicine. 1999;48(9): 1259–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Courts NF, Barba RE, Tesh A. Family caregivers’ attitudes toward aging, caregiving, and nursing home placement. J Gerontol Nurs. 2001;27(8):44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams GR, Deal AM, Lund JL, et al. Patient-Reported Comorbidity and Survival in Older Adults with Cancer. Oncologist. 2018;23(4):433–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ge L, Mordiffi SZ. Factors Associated With Higher Caregiver Burden Among Family Caregivers of Elderly Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40(6):471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin JY, Lim JW, Shin DW, et al. Underestimated caregiver burden by cancer patients and its association with quality of life, depression and anxiety among caregivers. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(2):e12814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawilowsky SS. New effect size rules of thumb. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods. 2009;8(2):26. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohile SG, Fan L, Reeve E, et al. Association of cancer with geriatric syndromes in older Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Oncol. 2011. ;29(11): 1458–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorgensen TL, Hallas J, Friis S, Herrstedt J. Comorbidity in elderly cancer patients in relation to overall and cancer-specific mortality. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(7): 1353–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowenstein LM, Volk RJ, Street R, et al. Communication about geriatric assessment domains in advanced cancer settings: “Missed opportunities”. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(l):68–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu T Caregivers of Older Adults with Cancer — Unique Challenges and Functional and Socio-Economic Implications. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2014;5:S7. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crouch E, Probst J, Bennett K. Rural-urban differences in unpaid caregivers of adults. Rural Remote Health. 2017;17(4):4351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brazil K, Kaasalainen S, Williams A, Dumont S. A comparison of support needs between rural and urban family caregivers providing palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(1):13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eom CS, Shin DW, Kim SY, et al. Impact of perceived social support on the mental health and health-related quality of life in cancer patients: results from a nationwide, multicenter survey in South Korea. Psychooncology. 2013;22(6):1283–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burgdorf J, Roth DL, Riffin C, Wolff JL. Factors Associated With Receipt of Training Among Caregivers of Older Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):833–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Payne S, Jarrett N, Jeffs D. The impact of travel on cancer patients’ experiences of treatment: a literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2000;9(4):197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henning-Smith C, Lahr M. Rural-Urban Difference in Workplace Supports and Impacts for Employed Caregivers. The Journal of Rural Health. 2019;35(1):49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]