Abstract

Melanoma, the most malignant form of skin cancer, shows resistance to traditional anticancer drugs including paclitaxel (PTX). Furthermore, over 50% of melanoma cases express the BRAFV600E mutation which activates the MAPK pathway increasing cell proliferation and survival. In the current study, we investigated the capacity of the combination therapy of PTX and the MAPK inhibitor, PD98059, to enhance the cytotoxicity of PTX against melanoma and therefore improve treatment outcomes. Synergistic in vitro cytotoxicity was observed when soluble PTX and PD98059 were used to treat the A375 melanoma cell line as evidenced by a significant reduction in the cell viability and IC50 value for PTX. Then, in further studies, TPGS-emulsified PD98059-loaded PLGA nanoparticles (NPs) were prepared, characterized in vitro and assessed for therapeutic efficacy when used in combination with soluble PTX. The average particle size (180 nm d.), zeta potential (−34.8 mV), polydispersity index (0.081), encapsulation efficiency (20%), particle yield (90.8%), and drug loading (6.633 μg/mg) of the prepared NPs were evaluated. Also, cellular uptake and in vitro cytotoxicity studies were performed with these PD98059-loaded NPs and compared to soluble PD98059. The PD98059-loaded NPs were superior to soluble PD98059 in terms of both cellular uptake and in vitro cytotoxicity in A375 cells. In in vivo studies, using A375 challenged mice, we report improved survival in mice treated with soluble PTX and PD98059-loaded NPs. Our findings suggest the potential for using this combinatorial therapy in the management of patients with metastatic melanoma harboring the BRAF mutation as a means to improve survival outcomes.

Keywords: PD98059, paclitaxel, melanoma, BRAF mutation, MEK1/2, nanoparticles

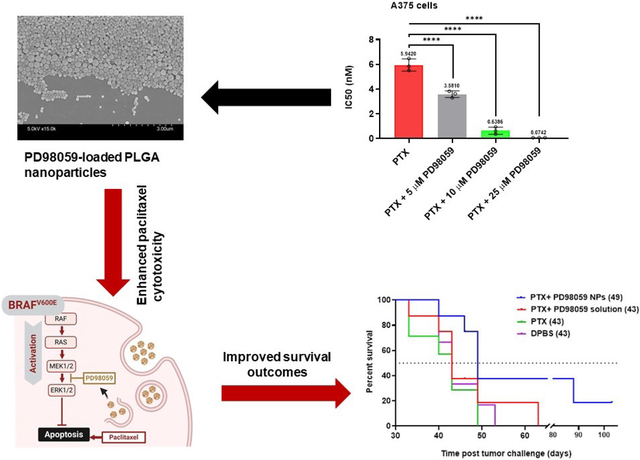

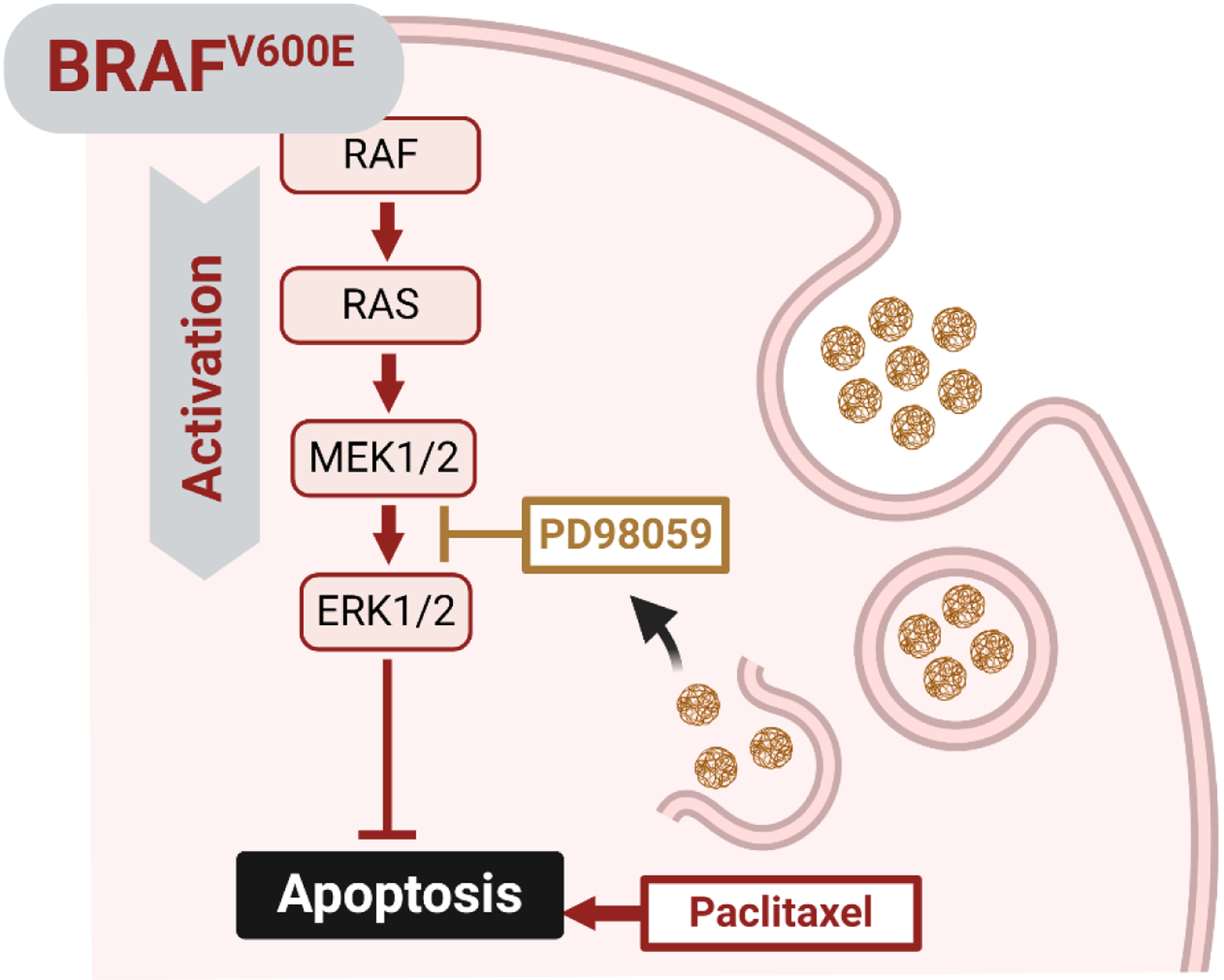

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Melanoma, the most invasive form of skin cancer, is the leading cause of skin cancer-related deaths worldwide comprising approximately 80% of skin cancer mortality rates. In the USA alone, one patient dies of melanoma every hour (Erdei and Torres, 2010). The median survival of patients with advanced metastatic melanoma is 6–10 months (Sosman et al., 2012), and the 5-year survival can be less than 5% (Erdei and Torres, 2010), compared to 98% and 90% in stage I and stage II melanoma, respectively, where surgical resection is the most efficient treatment (Long et al., 2017). Surgical resection though is generally insufficient for more advanced melanoma due to invasiveness or metastasis of the disease (Long et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2020). Mutations in serine-threonine protein kinase BRAF, which signals upstream of the mitogen activating protein kinase (MAPK) cascade were first described in 2002 and are present in ~7% of all cancers. However, BRAF mutations are present in ~50% of all melanoma cases (Flaherty et al., 2012; Larkin et al., 2014; Ribas et al., 2019; Xue et al., 2017). The most common of BRAF mutations are BRAFV600E followed by BRAFV600K, which together comprise ~95% of BRAF mutations in cutaneous melanoma (Flaherty et al., 2012). These mutations result in constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway proteins MEK1, MEK2 (MEK1/2) and ERK1/2. The activation of ERK1/2 promotes anti-apoptotic signals resulting in improved survival of cancer cells and the emergence of chemotherapy resistance (Larkin et al., 2014; Ribas et al., 2019; Xue et al., 2017).

In the past decade, anti-CTLA4 (e.g. ipilimumab, Yervoy®, Bristol Myers Squibb), anti-PD1 (e.g. nivolumab, Opdivo®, Bristol Myers Squibb, and pembrolizumab, Keytruda®, Merck), BRAF inhibitors (e.g. dabrafenib, Tafinlar®, Novartis, and vemurafenib, Zelboraf®, Genentech), and MEK inhibitors (e.g. trametinib, Mekinist®, Novartis), either independently or in certain combinations, were clinically approved to treat patients with advanced melanoma, resulting in significantly improved survival rates. In particular, the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib, resulted in longer 5-year progression-free survival and overall survival compared to the individual treatments. This highlights the importance of the BRAF oncogene and MEK activation in the progression of BRAFV600-mutated metastatic melanoma (Long et al., 2018). Resistance to BRAF inhibitors due to MAPK reactivation emerged as an obstacle which ultimately results in disease progression and recurrence (Lee et al., 2020). To overcome this resistance, continuous dosing of BRAF and MEK inhibitors was found to be superior compared to their intermittent dosing in BRAFV600-mutated metastatic melanoma (Algazi et al., 2020). The search is still ongoing to successfully overcome resistance in metastatic melanoma, however, one way to achieve continuous dosing is through the use of nanoparticles (NPs).

Previously, our group used NP combinations of paclitaxel (PTX), a well-known microtubule stabilizer, and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor BIBF 1120 (nintedanib), to achieve a synergistic anticancer activity in a human endometrial cancer model in nude mice (Ebeid et al., 2018). Since PTX is reported to activate the MAPK pathway on its own, inducing its own resistance (Xu et al., 2009), especially in BRAF-mutated cancer cells where MAPK activation is a well-established antiapoptotic trigger (Collisson et al., 2003; Koo et al., 2002; Li et al., 2016), we hypothesized that a combination of PTX and a MEK-specific inhibitor (loaded into NPs) in BRAFV600E mutated melanoma cells may diminish resistance against PTX in BRAFV600E mutated melanoma cells, thus enabling PTX to illicit a more potent anticancer effect. The MEK1/2 inhibitor, PD98059 suffers a short half-life in vivo (~72 min in rats) (Naguib et al., 2020), and attempts to deliver PD98059 using polymeric NPs has been stymied by poor drug loading (Basu et al., 2009). We sought first to test the hypothesis that PD98059 can synergize with PTX in terms of the cytotoxic effect against human melanoma cells carrying the BRAFV600E mutation (A375) in vitro and in vivo. Then we aimed to prepare PD98059-loaded poly lactide-co-glycolide (PLGA) NPs and use this formulation to improve tumor accumulation of PD98059 following intravenous (IV) administration, as previously reported (Ebeid et al., 2018; Iyer et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2018; Naguib and Cui, 2014; Naguib et al., 2014). The short half-life of PD98059 mandates the use of NPs to improve tumor accumulation since short circulation times may not allow enough time for the injected soluble dose to reach the tumor in sufficient quantities for sufficient time. In this work, we used tocopheryl-PEG succinate (TPGS) as a surfactant to render the NPs PEGylated, thus prolonging their circulation time, and to improve their cellular uptake (Ebeid et al., 2018). We also tested this combination in other cancer cells that harbor other MAPK-related mutations such as KRAS mutations. Mechanistic studies were carried out to further investigate the mechanism by which the combination treatment promotes cell death. Finally, the efficacy of the combination of PD98059 loaded NPs and PTX was tested in an A375 tumor-bearing nude mouse model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

PD98059 was purchased from Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX. PTX was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). Resomer RG 502 H (Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid, PLGA 50:50) was obtained from Evonik Industries AG (Darmstadt, Germany). D-α-Tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS), 7-hydroxy flavone, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and triton X-100, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Tween 80 was obtained from Fisher Chemicals (Waltham, MA). Other chemicals were at least of analytical grade and were used as received without further purification.

2.2. Cell culture and cell viability assay

The human melanoma cell line A375 (ATCC) was generously provided by Prof. Meng Wu (University of Iowa). The human pancreatic cancer cell lines, Panc-1, and BxPC-3 were kindly provided by Prof. Michael Henry at Carver College of Medicine, the University of Iowa. A375 and Panc-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, Invitrogen) while BxPC-3 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco), both were supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL, Gibco). Cells were maintained at 37° C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator (Sanyo Scientific Autoflow).

For cell viability assays, serial dilutions of PD98059 and PTX alone (in DMSO), and PTX combined with 5, 10 or 25 μM PD98059 were tested for effects on the viability of A375, Panc-1 or BxPC-3 cells (PTX was only combined with 10 or 25 μM PD98059 in the case of pancreatic cancer cells). One day before treatment, each of the three cell lines was seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1500 cells/well. Treatments were added as indicated and after three days, media (200 μL) was aspirated and replaced with 100 μL complete fresh medium and 20 μL MTS reagent (CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega Corporation) and incubated at 37° C for 2 h. Absorbance was measured using Spectra Max plus 384 Absorbance Microplate (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at a wavelength of 490 nm. Cell viability was expressed as the percentage of the absorbance from treated cells compared to that from the untreated cells. IC50 values for PTX, PD98059, and the combination were calculated using GraphPad Prism. The synergy between PTX and PD98059 in the A375 cell line was assessed using CompuSyn software (ComboSyn Inc.) by establishing dose-response curves for both treatments and their combination. Combination index (CI) values were calculated, where CI < 1 indicates synergy.

2.3. Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry

For cell cycle analysis, A375 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5×103 cells/well in 2 mL complete DMEM and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C for 24 h. Then, cells were treated with 5 nM PTX, 25 μM PD98059, or their combination, and incubated for another 24 h. Subsequently, media was aspirated, and cells were washed twice with PBS, trypsinized, and quenched with fresh media. Cells were collected and fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Then cells were centrifuged at 230 xg for 5 min, resuspended in 250 μL PBS containing 1% NP-40 (Sigma Aldrich) and 100 μg/mL RNAse solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and incubated at 37° C for 30 min. Then 250 μL of PBS containing 1% NP-40 and 50 μg/mL propidium iodide solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added to each tube, and then samples were analyzed by a BD FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Data were further analyzed using ModFit LT 5.0 software and histograms showing cell percentage in each cell cycle stage; G0/G1, S or G2/M and percentage apoptotic cells were obtained using GraphPad Prism software. Modeling was carried out through two steps. First, the software specified the percentage of apoptotic cells (sub G1) cells from the total cell population. Second, the remaining live cells were set as 100% and the percentage of cells in each of the three cell cycle phases G0/G1, S or G2/M was further calculated.

2.4. Caspase activity

Apoptosis, programmed cell death, can be triggered in cells either via an extrinsic or intrinsic pathway, characterized by the activation of caspase 8 or 9, respectively, which in turn activate caspase 3, resulting in downstream events involved in cell death (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2020; Abdel-Rahman et al.). To investigate the effect of the treatment combination on the expression of caspases, A375 cells were incubated with different concentrations of the indicated drugs, and this was followed by measuring the activity of caspase 3, 8, and 9 using a Multiplex Activity Assay Fluorometric Kit (Abcam). Briefly, A375 cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 1500 cells/well in 200 μL medium and the plate was then incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 48 h. Subsequently, cells were incubated with the indicated treatment as follows: (i) untreated cells, (ii) cells treated with 10 nm PTX, (iii) cells treated with 20 nM PTX, (iv) cells treated with 25 μL PD98059, (v) cells treated with 10 nM PTX and 25 μM PD98059, and (vi) cells treated with 20 nM PTX and 25 μM PD98059. After 24 h of incubation with the treatments, assay reagents were added following the manufacturer’s instructions, and the plate was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 60 minutes. Finally, caspase 3, 8, and 9 activities were measured using a fluorescence microplate reader (SpectraMax M5, Molecular Devices), and data were collected and analyzed.

2.5. PD98059-loaded PLGA-NP preparation and characterizations

PD98059 NPs were prepared using a nanoprecipitation method. One mg of PD98059 and 50 mg PLGA 50:50 were dissolved in 1.5 mL acetone (Fisher Scientific). The organic phase was transferred into a 5 mL syringe with a G26 size needle that was submerged under the surface of a magnetically stirred 30 mL aqueous solution of 0.2 % w/v TPGS. After 15 minutes of stirring, the suspension was transferred to a rotary evaporator to evaporate the rest of the organic solvent under reduced pressure of 50 mbar for 2.5 h. NPs were then washed with nanopure water (NANOpure diamond, Barnstead) and collected using Amicon® Ultra-15 centrifugal filters (100 kDa NMWL, Merk Millipore) at 500 xg for 30 min four times using an Eppendorf centrifuge 5804 R (Eppendorf). Size (hydrodynamic diameter (d.)) and zeta potential of NPs were measured in liquid suspension after dilution in Nanopure water using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instrument Ltd, Westborough, MA).

2.5.1. Evaluation of NP morphology

A Scanning Electron Microscope (Hitachi S-4800 SEM, Hitachi High-Technologies, Ontario, Canada) was used to examine the shape and surface morphology of the prepared PLGA nanoparticles. In brief, a NP suspension was added onto a silicon wafer mounted on an aluminum SEM stub, allowed to air dry for 24 h, and then coated with gold and palladium using an argon beam K550 sputter coater (Emitech Ltd, Kent, England). Finally, images were captured by SEM operated at a 3 kV accelerating voltage.

2.5.2. Estimation of drug loading capacity, encapsulation efficiency and percent yield of PD98059-loaded NPs

Briefly, 10 μL of the PD98059 NPs was dissolved in 100 μL acetonitrile, then 550 μL of methanol was added. Next, the volume was brought to 1 mL with Nanopure water. This resulting solution was centrifuged at 14000 xg for 15 min. Finally, the supernatant was analyzed using HPLC. The concentration of PD98059 was calculated from a previously constructed calibration curve. Drug loading capacity and encapsulation efficiency were calculated from the following equations:

| Equation 1: |

| Equation 2: |

To estimate the percent yields, the prepared NPs were lyophilized and accurately weighed, and the percent particle yield was calculated using the following equation:

| Equation 3: |

2.5.3. In vitro release study of PD98059-loaded NPs

The cumulative release of PD98059 from PLGA nanoparticles was studied using Float-A-lyzer (50 KD MWCO, 1 mL capacity, regenerated cellulose membrane). Briefly, NPs were suspended in 1 mL buffer and transferred into the Float-A-lyzer which was placed in a 50 mL tube containing 12 mL release medium (PBS pH 7.4 + 0.4 % Tween 80), and the tubes were shaken at 300 rpm and 37° C. Samples were withdrawn at each predetermined time point, and the drug content was measured using HPLC. All release medium at each time point was replaced with a fresh medium to maintain sink condition. All release experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the data were expressed as the mean of the % cumulative release ± standard deviation (SD).

2.5.4. Intracellular uptake of PD98059-loaded NPs

A cell uptake study was performed to predict the uptake of PD98059-loaded NPs compared to PD98059 solution by quantification of PD98059 amount per protein. A375 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 3×105 cells/well in a total volume of 2 mL complete culture medium and cultured for 24 h at 37°C. The medium was changed for a fresh serum-free medium (to hasten the particle uptake process; therefore, the difference in magnitude of nanoparticle uptake could be noticed over a shorter period of time). Cells were then treated with freshly prepared PD98059 NPs and free PD98059 solution at a dose of 20 μM of the drug and incubated for 24 h.

After incubation, media were removed, and cells were washed twice with PBS. Cell lysis solution (1:1 2% w/v SDS + 1% v/v triton X100) was added at a volume of 1 mL/well and plates were incubated for 15 min at 37°C. Cell lysates were then collected for extraction and analysis of PD98059 accumulated intracellularly. Then 7-hydroxy flavone (15 μL of 10 μg/mL in methanol) was added to 250 μL of cell lysate as an internal standard and vortexed. Acetonitrile (1 mL) was added to each sample, then samples were vortexed to extract PD98059, stored for 15 min at 40°C, and finally centrifuged at 21000 xg for 5 min. The upper organic layer was separated, evaporated under a nitrogen gas stream and the residue was reconstituted in 75 μL methanol by vortexing and sonication. The volume was adjusted to 150 μL using nanopure water and centrifuged. The supernatant was injected onto a reversed-phase column (RP-C18, 5 μm pore size, 4.6 mm × 150 mm, Waters Symmetry, Milford, MA), eluted with the mobile phase (70:30 methanol:water with 0.1% v/v trifluoroacetic acid) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min and detected at a wavelength of 300 nm using an Agilent Infinity 1100 HPLC (Santa Clara, CA). PD98059 concentration was determined using a previously constructed calibration curve.

Cellular protein quantification assay was carried out using Micro BCA (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit, Thermo Scientific) under the manufacturer’s instructions. One hundred μL of cell lysate was incubated for 2 h at 37°C, with 100 μL of the working reagent. Absorbance was measured at 562 nm using Spectra Max plus 384 Microplate Spectrophotometer.

2.5.5. In vitro cellular cytotoxicity assay of PD98059 NPs

The cytotoxic effects of PD98059-loaded PLGA NPs (equivalent to 20 μM) compared to PD98059 solution (20 μM) against the A375 cancer cell line (5000 cells/well) was determined using the MTS assay. Cells were incubated for 72 h at 37°C, treated with MTS reagent, and incubated again for 2 h. The viability of cells was analyzed as previously described.

2.6. Survival study in tumor-bearing mice

All animal experiments were performed according to guidelines and regulations approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Iowa. Female athymic Nu/Nu mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories and used for the tumor xenograft model. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine cocktail and subcutaneously challenged with a suspension of 1 × 106 A375 cells/mouse in serum-free DMEM in the right flank. Eight days following tumor challenge, mice were divided randomly into four groups, and were IV injected with: (i) PTX solution (PTX 6 mg/ml concentrate for IV infusion (Athenex, Inc, Buffalo, NY) diluted in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), 5 mg/kg) and PD98059 NPs (equivalent PD98059 concentration of 4 mg/kg), (ii) PTX solution (5 mg/kg), (iii) PTX solution (5 mg/kg) and PD98059 solution (in Tween 80:ethanol:DPBS 10:5:85 solution, 4 mg/kg) or (iv) DPBS. Each group consisted of 8 animals except for PTX and DPBS which had 7 and 6 mice, respectively. Treatments were given IV in the tail vein on days 8, 13, and 15 post tumor challenge. At different time points (days 8, 14, 19, 22, 26, 33, 37, 43, 46, 49, 53, 63, 88, and 103 post tumor challenge), tumor volumes were determined by measuring tumor length (L), height (H) and width (W) using a digital caliper and calculated from the following equation:

| Equation 4: |

Mice were also weighed at the same time points as the tumor measurement. Other vital signs or signs of stress including mice feeding habits, dehydration, and mobility were also monitored. Tumor and body weight measurement and vital signs monitoring were performed for 103 days. For survival analysis, mice that died or reached any of the biological endpoints listed in the IACUC-approved protocol were considered dead. The median survival time was estimated across all animal groups using GraphPad Prism software.

2.7. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software for windows version 8.3.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.). A two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to compare PD98059-loaded NPs and PD98059 in solution in the cellular uptake study, while a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey post-hoc test was performed to compare the IC50 between different treatments against the studied cell lines. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed using the log-rank test (for trend), and subjects who were dropped out were considered “censored” (Goel et al., 2010). P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Cell viability assay and cell cycle analysis

The in vitro cytotoxic activity of the combination of PTX and PD98059 was investigated against A375 malignant melanoma cancer cells which harbor the BRAFV600E mutation. Results of the cell viability study demonstrated that the addition of PD98059 increased the cytotoxicity of PTX in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1, A). Additionally, a highly significant (P ≤ 0.0001) 10-fold and 84-fold decrease in the IC50 of PTX was shown when combined with 10 μM and 25 μM PD98059, respectively (Figure 1, B) (i.e., IC50 of PTX alone and its combination with 10 μM and 25 μM PD98059 were 5.9 nM, 0.6 nM, and 0.07 nM, respectively). Furthermore, the synergy between PD98059 and PTX was demonstrated as determined by the combination index (CI) (Figure 1, G).

Figure 1:

Cytotoxicity assessment using MTS assay against 3 different cell lines. Dose-response curves of (A) A375 cells (C) Panc-1 cells or (E) BxPC-3 cells to treatment with soluble PTX and/or PD98059; using indicated concentrations of PTX combined with either 5, 10, and 25 μM PD98059 and measured using an MTS assay after 72 h of treatment. The mean IC50 of PTX with different concentrations of PD98059 for (B) A375 cells (D) Panc-1 cells or (F) BxPC-3 cells (statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test). (G) The synergy between PTXs and PD98059 in A375 cells, where the combination index (CI) was plotted versus fraction affected (Fa), CI < 1 indicates synergy. Individual data points are expressed as open circles. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). **** P < 0.0001, *** P < 0.001, * P < 0.05. Abbreviations: PTX; paclitaxel, ns; not significant.

Additionally, the combination of PTX and PD98059 was evaluated in two human pancreatic cell lines, Panc-1, harboring a KRAS mutation, and BxPC-3 (wild type KRAS) (Deer et al., 2010). Results of cytotoxicity assays involving PTX, PD98059, and their combinations against Panc-1 and BxPC-3 cells are shown (Figure 1, C & E) as well as IC50 values (Figure 1, D & F). Treatment of Panc-1 cells with PTX and PD98059 revealed increasing cytotoxicity with increasing concentrations of PD98059. Also, there was a statistically significant 2-fold decrease (P ≤ 0.0001) in the IC50 of PTX upon the addition of 25 μM. In contrast, we noticed a different behavior for this combination therapy against BxPC-3 cells, where no differences in the cell viability were observed between PTX alone and PTX plus either 10 μM or 25 μM PD98059. In addition, a statistically insignificant decrease in the IC50 of PTX was observed with the addition of 25 μM PD98059.

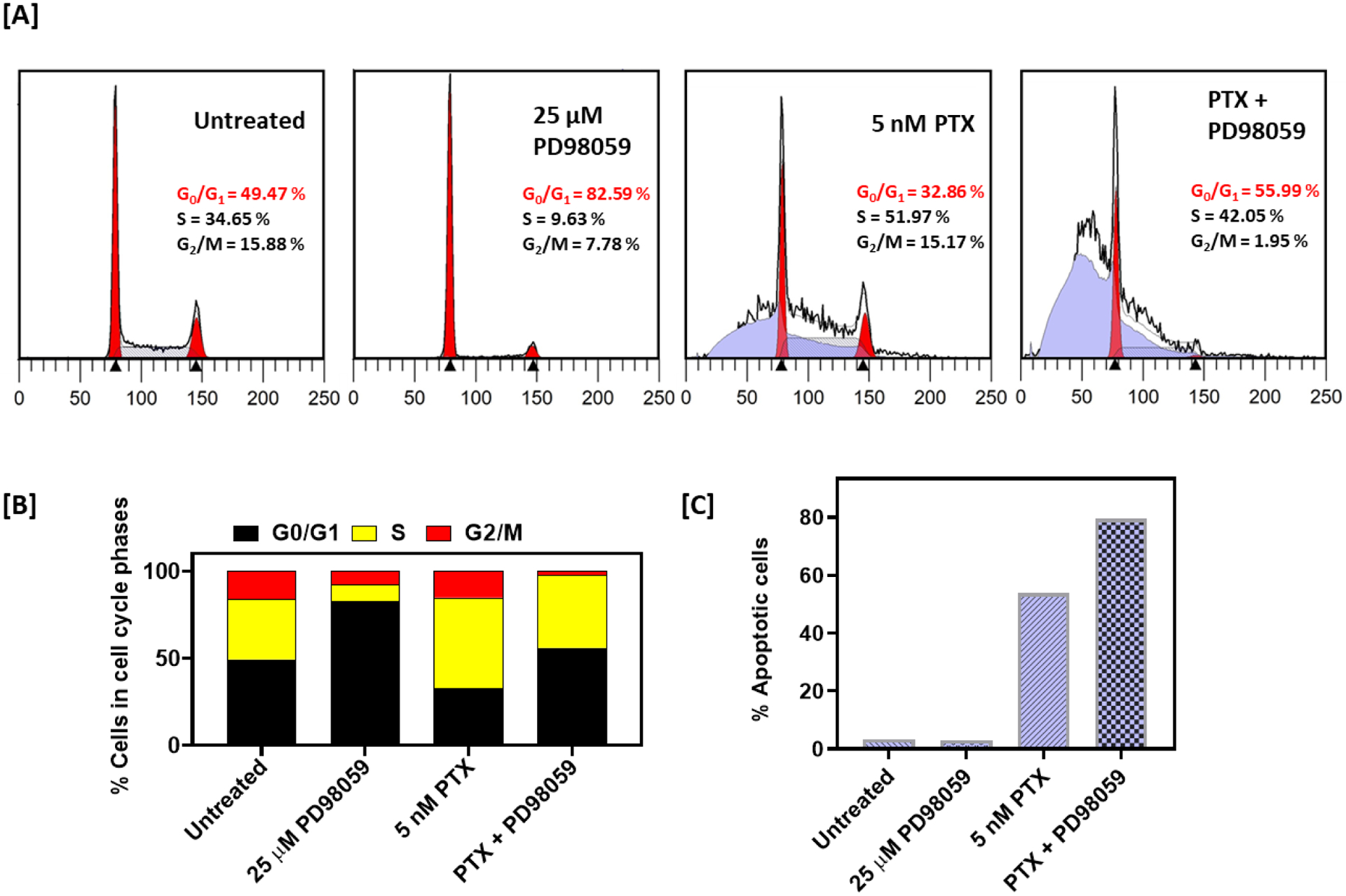

In order to investigate the mechanism underlying the observed synergy, we carried out flow cytometry experiments to analyze cell cycle progression (Figure 2, A). A375 cells were either treated with 5 nM PTX, 25 μM PD98059, or the combination of both for 24 h. Cells treated with PTX alone showed a marked increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells (sub G0/G1 population) (53.83%) as compared to the untreated control (3.31%), with no effect on the G2/M cell population. PD98059-treated cells did not affect the percentage of apoptotic cells (3.04%) as compared to the untreated control (3.31%), however, it exhibited marked G0/G1 cell cycle arrest (82.59%) (Figure 2, B). The combination of PTX and PD98059 resulted in an increase in the apoptotic cell population (79.52%) (Figure 2, C).

Figure 2:

Cell cycle studies of cells treated with PTX +/− PD98059. (A) Cell cycle profiles of A375 cells treated with 5 nM PTX, and 25 μM PD98059 or their combinations for 24 h. (B) Representative histograms for A375 cells percentage in each cell cycle. (C) Percentage of apoptotic cells. Abbreviations: PTX; paclitaxel

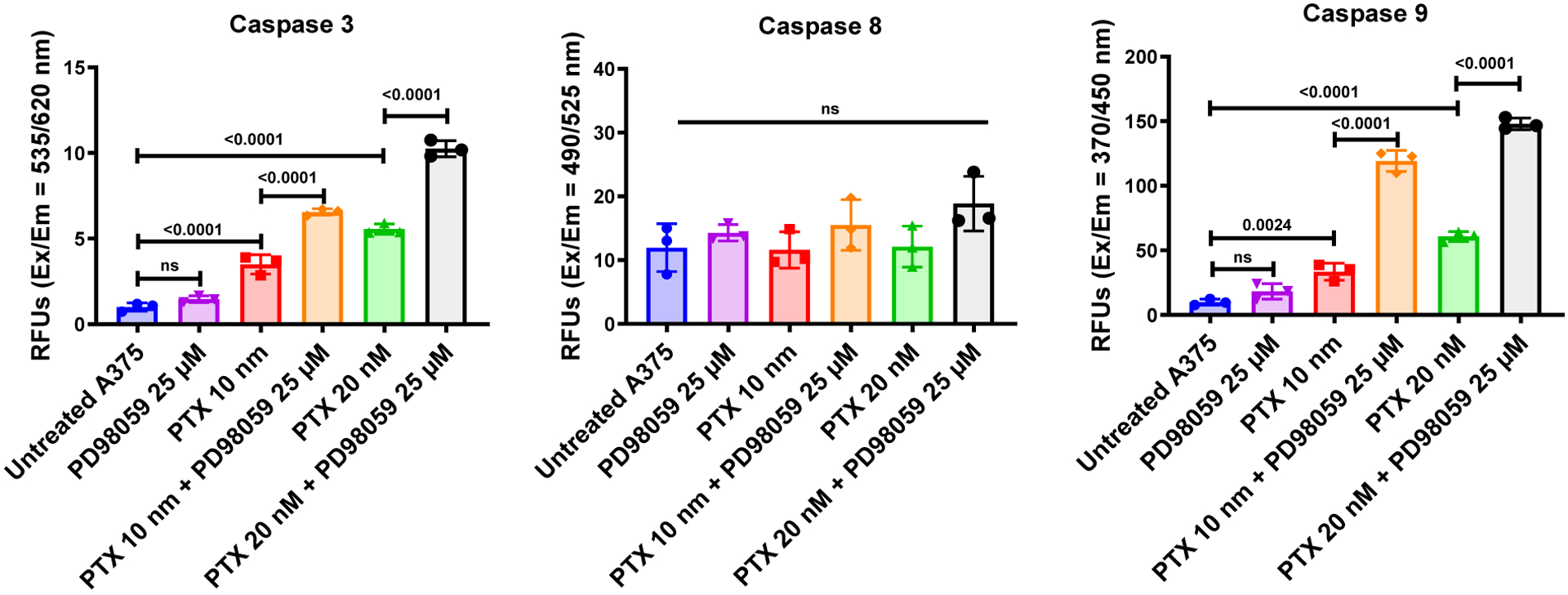

3.2. Caspase activity study

PTX is known to induce cell death through the intrinsic (rather than extrinsic) pathway of apoptosis, beginning when an injury occurs within the cell (specifically, mitochondria). Thus, we expected significantly increased caspase 9 activity in A375 cells treated with PTX compared to untreated cells, as was observed (Figure 3). In contrast, and also expected, there were not statistically significant differences in the levels of caspase 8 activity (which is stimulated by extrinsic stimuli) in PTX-treated cells compared to untreated cells. While treatment of cells with PD98059 alone did not significantly increase the activity of caspase 9 (nor caspase 3), when it was co-delivered with PTX, significantly higher levels of caspase 9 (and caspase 3) activity were noted.

Figure 3:

Activity of caspases in A375 cells treated with either PTX or PD98059 or a combination of both compounds. Treatments were added to A375 cells and incubated for 24 hours. The activities of caspase 3, 8, and 9 were evaluated as described in the methods section. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

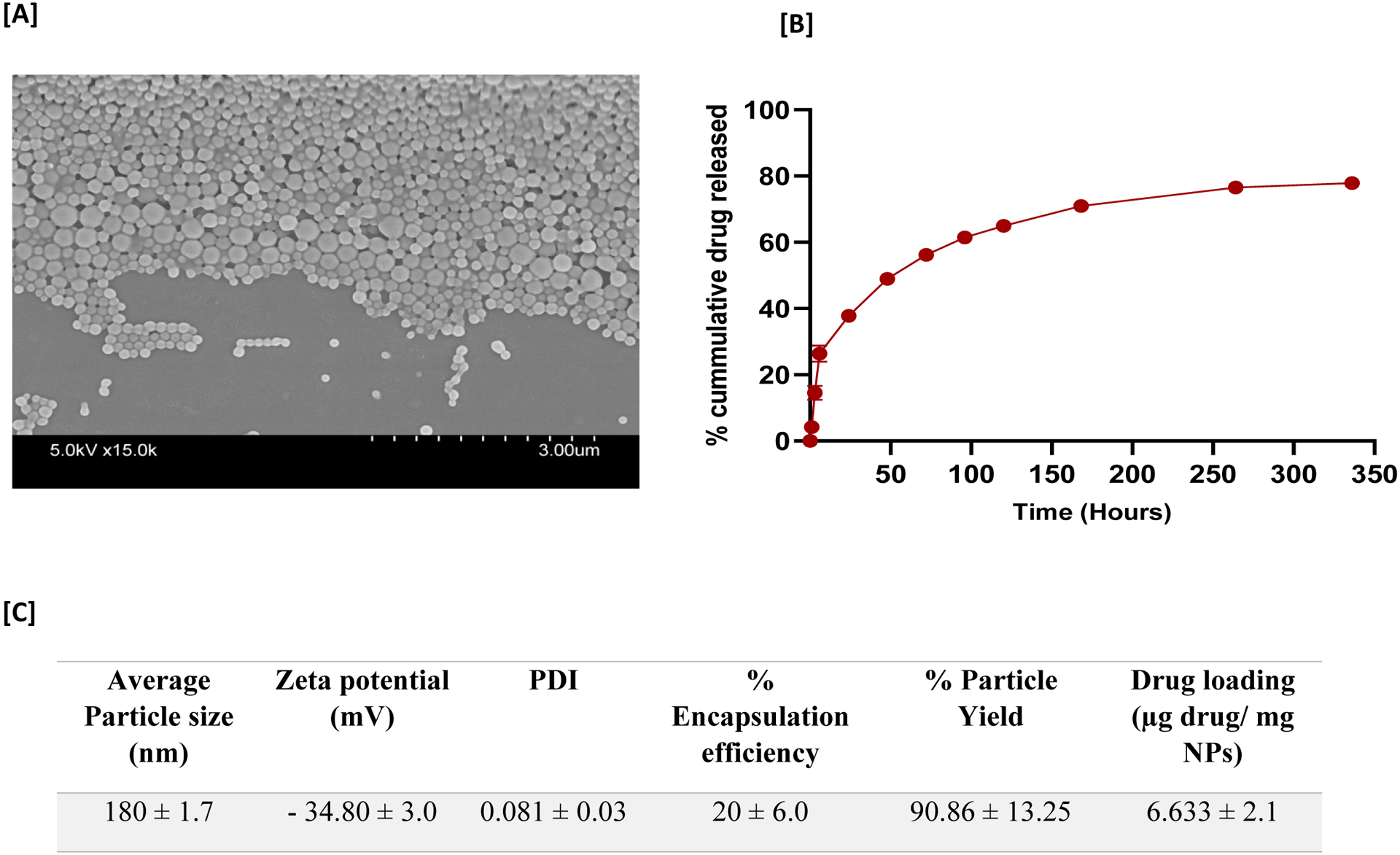

3.3. Preparation and characterization of PD98059-loaded PLGA-NPs

PLGA NPs loaded with PD98059 were made in an attempt to overcome the short circulatory half-life of soluble PD98059 and improve passive targeting to tumors. NPs were formulated by a nanoprecipitation method using the polymer PLGA (50: 50), and TPGS as a surfactant to increase the cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of the prepared NPs. SEM images of the freshly prepared PLGA NPs showed spherically shaped NPs (Figure 4, A). The average particle size/hydrodynamic diameter of the drug-loaded PLGA NPs was approximately 180 nm d. with a low polydispersity index of 0.081 and zeta potential of approximately −34.80 mV (Figure 4, C). The percent of particle yield was 90.86 % with drug loading 6.633 μg drug/mg NPs and 20% encapsulation efficiency (Figure 4, C). The release profile of PD98059 from the prepared PLGA NPs was then studied and showed 25% cumulative drug release after the first 6 hours and ~50% release after 48 hours (Figure 4, B).

Figure 4:

Characterization and release profile of PD98059-loaded NPs. (A) Representative scanning electron microscope images of PD98059-loaded PLGA-nanoparticles. (B) In vitro release study of PD98059 from PD98059-loaded NPs, and a DPBS (pH 7.4) + 0.4 % Tween 80 as the release medium over 14 days. (C) PD98059-loaded NP characterization. Average particle size as measured by dynamic light scattering. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Abbreviations: PDI; polydispersity index.

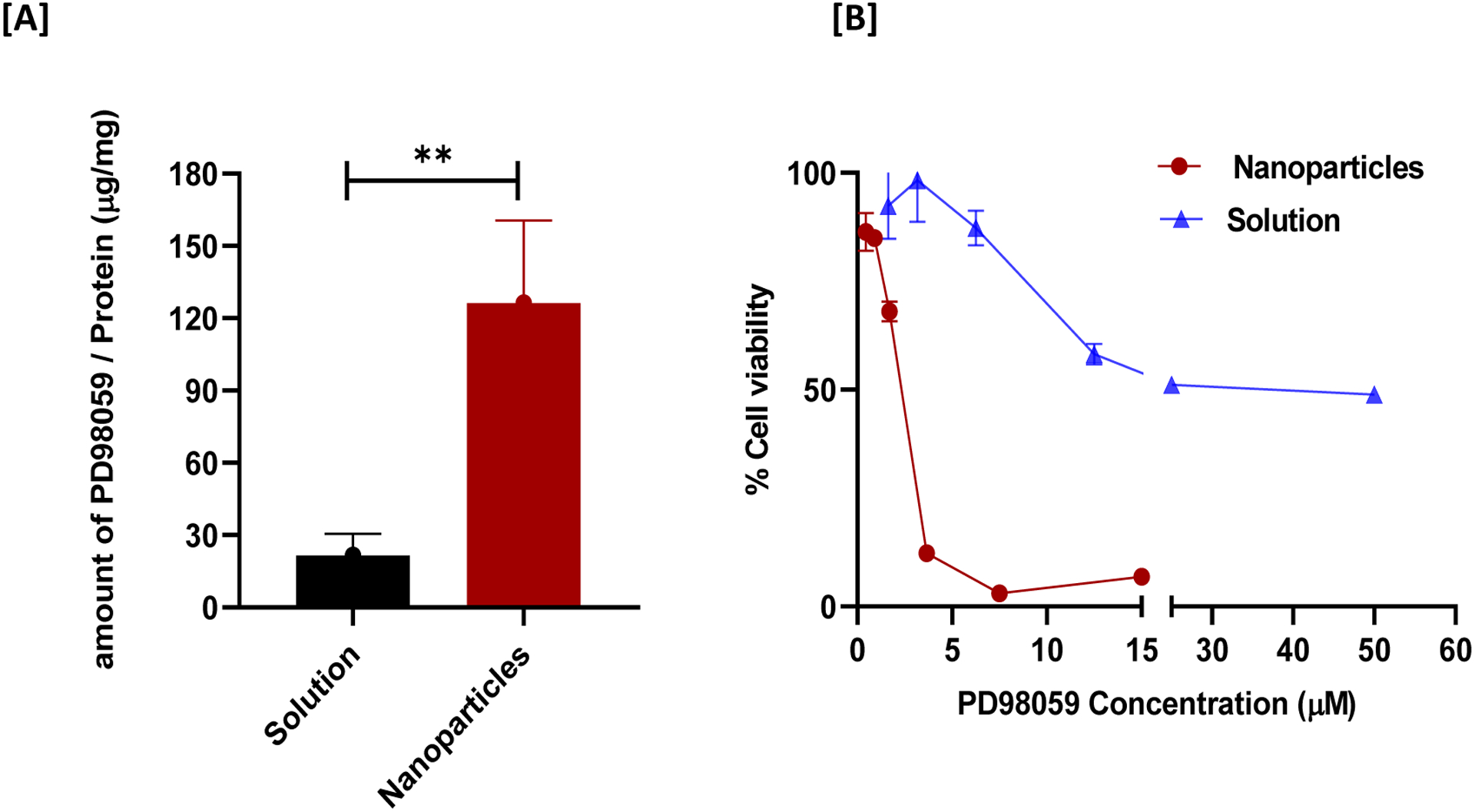

3.4. PD98059-loaded PLGA NPs: cellular uptake and in vitro cytotoxicity studies

Further in vitro evaluations of the prepared PD98059-loaded NPs loaded with the PD98059 were carried out, including a cellular uptake study. As shown in Figure 5A, the amount of PD98059 taken up by A375 cells was significantly higher when the cells were incubated with PD98059-loaded NPs versus soluble PD98059 (P ≤ 0.05; at equivalent dosing). This result suggests that NPs facilitated more efficient uptake by A375 cells. Subsequently, we compared the in vitro cytotoxicity of PD98059-loaded NPs to soluble PD980589 using A375 cells. As expected, PD98059-loaded NPs results demonstrated significantly greater cytotoxicity compared to the free drug where the viability of the NP-treated cells (15 μM PD98059 dose) was 6.8 % while cells treated with soluble PD98059 (15 μM dose) exhibited ~60% cell viability (Figure 5, B). Preliminary studies revealed that the cytotoxicity of the PD98059 NPs was superior to that of drug-free PLGA NPs prepared in a similar manner, which is in agreement with our previous findings with the same formulation (Ebeid et al., 2018) and to other researchers’ findings with very closely-related formulations (PLGA NPs prepared with TPGS as a surfactant) (Gao et al., 2019; Gaonkar et al., 2017).

Figure 5:

Cellular uptake and cytotoxicity study of PD98059-loaded NPs versus free drug (20 μM). (A) Amount of PD98059 present in A375 cells after 24 hours incubation period with indicated treatment. (B) Cytotoxicity study comparing the effect of PD98059 solution versus PD98059-loaded NPs on A375 cell viability (as measured using an MTS assay). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ** P < 0.01.

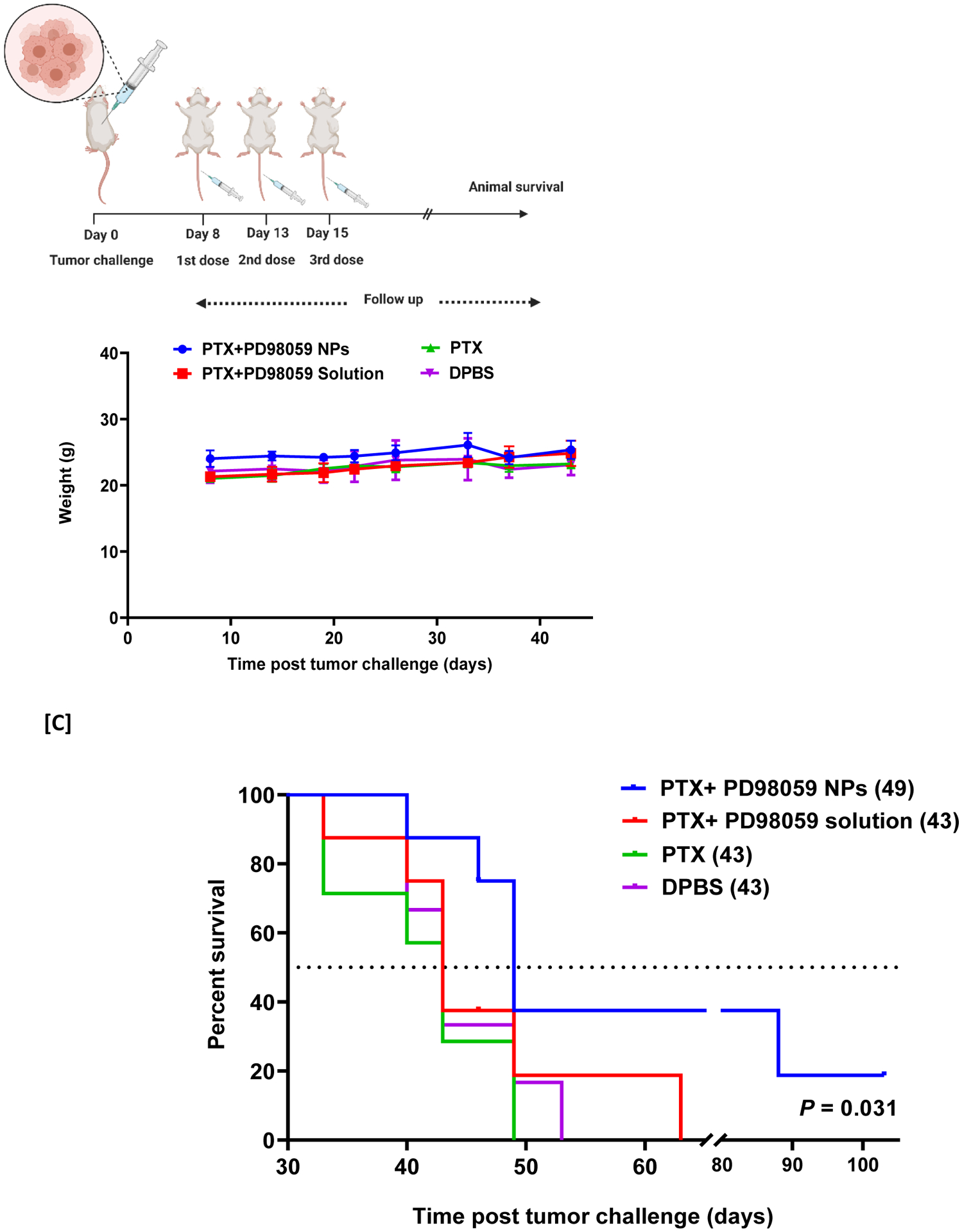

3.5. Survival study

Finally, we aimed to evaluate the impact of combining soluble PTX with PD98059-loaded NPs as a therapy in an in vivo melanoma model in mice. A survival study was conducted using a xenograft model, where mice were injected subcutaneously with A375 melanoma cells (Schematic presentation: Figure 6, A). Different mice groups were IV injected with different treatments, observed during the study and showed a stable body weight (Figure 6, B). A survival curve was generated, and median survival times were recorded to evaluate the efficacy of adding PD98059-loaded NPs to PTX versus the combination of PTX and soluble PD98059, PTX alone, or DPBS. The combination of PD98059-loaded NPs and PTX treatment significantly (P ≤ 0.05) improved the survival with a 49 days median survival time of mice compared to other groups (43 days) (Figure 6, C).

Figure 6:

[A] Schematic diagram of the in vivo survival study experimental design. [B] Weight change of mice during the study. [C] Survival study (values of median survival time are shown in brackets). Mice were challenged with A375 melanoma cell lines. Eight days later, mice were treated with PTX solution (5 mg/kg) + PD98059-loaded NPs (equivalent 4 mg PD98059/kg) (Concomitantly injected), PTX (5 mg/kg) alone, PTX (5 mg/kg) and PD98059 (4 mg/kg) solutions or DPBS. Survival data of mice were investigated using Kaplan–Meier analysis to compare the study groups. P-value was 0.031 (log-rank test). N = 8 for all groups except for PTX alone-treated (n = 7) and DPBS-treated (n = 6) groups.

Abbreviations: PTX; paclitaxel, DPBS; Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline, NPs; nanoparticles.

4. Discussion

This present study revealed synergy between PD98059 and PTX with respect to cytotoxicity towards the A375 melanoma model in vitro. PTX is reported to increase the endogenous MEK activity, predisposing the cells to PTX resistance (MacKeigan et al., 2000). However, the use of MEK1/2 inhibitors has been demonstrated to re-sensitize various cancer cell lines to PTX, including lung, breast, and colon cancer cell lines (MacKeigan et al., 2000; McDaid and Horwitz, 2001; Xu et al., 2009). McDaid and Horowitz reported that combinations of PTX and ERK inhibitors are beneficial in tumors with high levels of ERK activity, but not in those with low ERK activity (McDaid and Horwitz, 2001). We tested three cell lines with different types of MAPK-related mutations: A375 human melanoma cells (possessing a BRAFV600E mutation), Panc-1 human pancreatic adenocarcinoma (possessing a KRAS-mutation), and BxPC-3 human pancreatic adenocarcinoma (KRAS-WT). In A375 cells, the presence of the BRAFV600E mutation elicits survival signals, as the resulting MAPK cascade activation is accompanied by antiapoptotic activity and emergence of chemo-resistance (Kielbik et al., 2018). We found that the observed synergistic cytotoxic activity towards A375 when PD98059 was combined with PTX was associated with enhanced apoptosis (Figure 3; schematic of proposed mechanism: Figure 7), as indicated by the significant rise of caspase 3 activity, compared to caspase 3 levels in A375 cells treated with each agent alone. The enhanced activity of caspase 9 in cells treated with the combination of PTX and PD98059 indicates that the enhanced apoptosis is due to intrinsic stimuli (the use of chemotherapy). The marked statistically significant drop in the IC50 of PTX for A375 cells when PD98059 was added as a treatment in vitro indicates that the latter probably abolished resistance to PTX. The cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 upon treatment of PD98059 suggests a MAPK cascade blockade and up-regulation of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor, p27Kip1 (Hoshino et al., 2001; Wei et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2016). Furthermore, the significant increase in the apoptotic cell population upon the use of PTX is aligned with literature reports of PTX’s ability to induce apoptosis (MacKeigan et al., 2000), while at low concentrations it does not produce detectable G2/M cell cycle arrest (Das et al., 2001). That effect was further improved upon treatment of cells with PTX and PD98059 combination. PD98059 lacked the ability, as a single agent, to induce apoptosis, indicating that the observed increase in apoptosis with the combination is probably due to enhancement of PTX activity. This could be explained by the ability of PD98059 to mitigate PTX resistance imposed by the activation of the MAPK pathway. Further studies on the cytotoxic activity of this combination on Panc-1, showed a trend close to what was found for A375 cells, albeit to a lesser extent. On the other hand, this drug combination exerted no significant cytotoxic effect on BxPC-3, the KRAS wildtype cells, which may highlight the role of MAPK-related mutations in PTX resistance. Our findings are in agreement with a study that showed synergistic cytotoxicity towards human SK-MEL-28 melanoma cells using a combinatorial treatment of PTX and metformin (an ERK phosphorylation suppressor) where metformin suppressed the PTX-induced ERK activation (Ko et al., 2019). Also, Li and Yang (Li and Yang, 2019) reported an enhanced antiproliferative activity towards colorectal cancer cells of PTX upon the addition of PD98059.

Figure 7:

Graphical presentation of how PD98059 improves the cytotoxicity of paclitaxel.

Interestingly, we found that the cellular uptake of PD98059 in A375 was dramatically increased when the drug was in PLGA nanoparticles. Even though previous work reported on the anti-cancer properties of the combination of PTX and PD98059, most of these reports involved in vitro experiments or did not use a clinically feasible formulation to deliver PD98059 (Xu et al., 2009). In fact, the use of a nanocarrier may turn out to be mandatory in the case of PD98059, to provide a biocompatible and clinically relevant delivery system to be delivered via the IV route. Some researchers have dissolved PD98059 in a very small volume of DMSO prior to injection into experimental animals, which is also clinically non-practical (Clemons et al., 2002). Basu et al. reported a chemically conjugated PD98059 to PLGA to improve its poor loading that they encountered using conventional encapsulation techniques (Basu et al., 2009). We were able to use a simple methodology to prepare TPGS/PLGA nanoparticles loaded with PD98059 (6.633 μg/mg nanoparticles), small particle size/hydrodynamic diameter (~180 nm d.), and sustained drug release which ensures that the drug load will not be prematurely released before reaching the tumor.

To avoid generalized MAPK inhibition (and the subsequent potentiation of PTX), we delivered PD98059 in NPs in an attempt to exploit the EPR effect, which is expected to enhance tumor accumulation of PD98059 compared to when PD98059 is delivered in soluble form (Naguib and Cui, 2014). This should favor the potentiation of PTX efficacy at the tumor site over off-target sites. Although tumor accumulation was not tested in this study, the same PLGA/TPGS NP formulation has been shown by our group to achieve much higher tumor accumulation of the encapsulated drug compared to the soluble drug (Ebeid et al., 2018). PEGylated NPs are known to have longer circulation half-lives compared to non-PEGylated NPs following IV injection and exhibit higher tumor accumulation because of the EPR effect (Naguib and Cui, 2014). In our previous work, we used human endometrial tumors; this time, we used human melanoma tumors. A common feature between the two tumor models is the high vascularity (Avram et al., 2017; Davies et al., 2011; Ebeid et al., 2018; Kamat et al., 2007), which correlates well with enhanced tumor delivery. In addition, we have already shown that the NPs achieve higher cellular internalization, which is further evidence that the potentiation of PTX activity will be restricted to the intracellular compartment of the cancer cells.

In an animal model of human melanoma A375 in nude mice, we noticed that treatment with the combination of PD98059-loaded NPs and PTX enhanced the survival of mice compared to other groups. This is most likely attributed to the enhanced tumor accumulation of IV-injected drugs when they are encapsulated in NPs, as previously reported (Li et al., 2017; Naguib and Cui, 2014; Naguib et al., 2014). Further experiments are needed to verify this and to optimize the dose of the combination. It is worth mentioning that it was recently found that BxPC-3 cells harbor a BRAF deletion mutation. Even though this mutation can likely result in MAPK activation as well, the mechanism behind this activation may not be fully understood as BxPC-3 is not sensitive to the BRAF inhibitors dabrafenib and vemurafenib (Chen et al., 2016). We found that these cells are not sensitive to PD98059 (Figure 1), at least in the concentration range tested, and the combination did not add any therapeutic value when combined with PTX compared to PTX alone. This may indicate that the benefit of adding PD98059 to PTX in BRAF-mutated cancer cells may be restricted only to those harboring BRAFV600E.

Interaction between endogenous plasma proteins (opsonins) and the hydrophobic surfaces of the circulating NPs, resulting in opsonization, is one of the major hurdles to effective therapeutic outcomes from injected nanomaterial (Peng and Mu, 2016; Zhang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). Several techniques have been adopted to modify the surface of NPs in order to minimize opsonization, including PEGylation (Saxena et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2019; Ebeid et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2019; Gaonkar et al., 2017)) or coating NPs with selected proteins (e.g. albumin) (Peng and Mu, 2016). We used a well-known PEGylation strategy that has been proven successful at increasing tumor accumulation of NPs in our laboratory (Ebeid et al., 2018).

Most PTX-associated adverse events are dose-dependent (Argyriou et al., 2006; Scripture et al., 2006), and their incidence is expected to decrease when lower doses of PTX are used. Our strategy of harnessing the MAPK inhibitory activity of PD98059 to minimize chemo-resistance against PTX was proven to improve the efficacy of the administered commercially available PTX (PTX concentrate), which allows for the use of lower doses of PTX (in the presence of PD98059) to achieve equivalent efficacy to higher doses of PTX alone, as previously reported (MacKeigan et al., 2000). Thus, lower doses of PTX (in the presence of PD98059) will decrease the incidence of dose-dependent adverse effects.

Future investigations will include the evaluation of the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of PD98059-loaded NPs in organs and tumor tissues. We also plan to assess the safety/toxicity profile of this therapeutic approach. PD98059 is not used clinically and there is no current formulation to efficiently deliver this drug. Our approach is a step forward towards its clinical application and studying biodistribution and tumor accumulation, in addition to the safety/toxicity of the PD98059 NPs will potentially further promote this progression. In addition, we plan to further optimize this current formulation to enable the encapsulation of larger amounts of PD98059.

5. Conclusions

The findings from this study illustrate the importance of molecular targeting of BRAF-mutant A375 melanoma cells where inhibition of the MAPK pathway with PD98059 in vitro appears to abolish PTX resistance and improves survival outcomes in melanoma-challenged mice treated with PTX and NPs loaded with PD98059. The results also highlight the importance of formulating PD98059 into NPs as the solution form did not show significant therapeutic benefit in an in vivo melanoma cancer model, while the NP formulation did, when combined with PTX. This strategy does not only improve PTX efficacy but also has the potential to reduce off-target effects as this NP formulation has previously been found to divert its drug load biodistribution to the tumor site (Ebeid et al., 2018). This PD98059-loaded NP formulation could potentially be used as an adjuvant therapy to the commercially available PTX formulations to augment the therapeutic benefit of the latter for the treatment of patients with tumors harboring MAPK-related activating mutations.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Lyle and Sharon Bighley Chair and NCI P30 CA086862 for support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- Abdel-Rahman SA, El-Damasy AK, Hassan GS, Wafa EI, Geary SM, Maarouf AR, Salem AK, 2020. Cyclohepta[b]thiophenes as Potential Antiproliferative Agents: Design, Synthesis, In Vitro, and In Vivo Anticancer Evaluation. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 3, 965–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Rahman SA, Wafa EI, Ebeid K, Geary SM, Naguib YW, El-Damasy AK, Salem AK, Thiophene Derivative-Loaded Nanoparticles Mediate Anticancer Activity Through the Inhibition of Kinases and Microtubule Assembly. Advanced Therapeutics n/a, 2100058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algazi AP, Othus M, Daud AI, Lo RS, Mehnert JM, Truong TG, Conry R, Kendra K, Doolittle GC, Clark JI, Messino MJ, Moore DF Jr., Lao C, Faller BA, Govindarajan R, Harker-Murray A, Dreisbach L, Moon J, Grossmann KF, Ribas A, 2020. Continuous versus intermittent BRAF and MEK inhibition in patients with BRAF-mutated melanoma: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat. Med 26, 1564–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argyriou AA, Chroni E, Koutras A, Iconomou G, Papapetropoulos S, Polychronopoulos P, Kalofonos HP, 2006. Preventing paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy: a phase II trial of vitamin E supplementation. J Pain Symptom Manage 32, 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avram S, Coricovac DE, Pavel IZ, Pinzaru I, Ghiulai R, Baderca F, Soica C, Muntean D, Branisteanu DE, Spandidos DA, Tsatsakis AM, Dehelean CA, 2017. Standardization of A375 human melanoma models on chicken embryo chorioallantoic membrane and Balb/c nude mice. Oncology reports 38, 89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Harfouche R, Soni S, Chimote G, Mashelkar RA, Sengupta S, 2009. Nanoparticle-mediated targeting of MAPK signaling predisposes tumor to chemotherapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106, 7957–7961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SH, Zhang Y, Van Horn RD, Yin T, Buchanan S, Yadav V, Mochalkin I, Wong SS, Yue YG, Huber L, Conti I, Henry JR, Starling JJ, Plowman GD, Peng SB, 2016. Oncogenic BRAF Deletions That Function as Homodimers and Are Sensitive to Inhibition by RAF Dimer Inhibitor LY3009120. Cancer Discov 6, 300–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XP, Li Y, Zhang Y, Li GW, 2019. Formulation, Characterization And Evaluation Of Curcumin- Loaded PLGA- TPGS Nanoparticles For Liver Cancer Treatment. Drug design, development and therapy 13, 3569–3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons AP, Holstein DM, Galli A, Saunders C, 2002. Cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis in the rat is significantly ameliorated by treatment with MEK1/2 inhibitors U0126 and PD98059. Pancreas 25, 251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collisson EA, De A, Suzuki H, Gambhir SS, Kolodney MS, 2003. Treatment of metastatic melanoma with an orally available inhibitor of the Ras-Raf-MAPK cascade. Cancer Res. 63, 5669–5673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das GC, Holiday D, Gallardo R, Haas C, 2001. Taxol-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis: dose-response relationship in lung cancer cells of different wild-type p53 status and under isogenic condition. Cancer Lett. 165, 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S, Dai D, Pickett G, Thiel KW, Korovkina VP, Leslie KK, 2011. Effects of bevacizumab in mouse model of endometrial cancer: Defining the molecular basis for resistance. Oncology reports 25, 855–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deer EL, González-Hernández J, Coursen JD, Shea JE, Ngatia J, Scaife CL, Firpo MA, Mulvihill SJ, 2010. Phenotype and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas 39, 425–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebeid K, Meng X, Thiel KW, Do AV, Geary SM, Morris AS, Pham EL, Wongrakpanich A, Chhonker YS, Murry DJ, Leslie KK, Salem AK, 2018. Synthetically lethal nanoparticles for treatment of endometrial cancer. Nature nanotechnology 13, 72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdei E, Torres SM, 2010. A new understanding in the epidemiology of melanoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 10, 1811–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, Nathan P, Garbe C, Milhem M, Demidov LV, Hassel JC, Rutkowski P, Mohr P, Dummer R, Trefzer U, Larkin JM, Utikal J, Dreno B, Nyakas M, Middleton MR, Becker JC, Casey M, Sherman LJ, Wu FS, Ouellet D, Martin AM, Patel K, Schadendorf D, 2012. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med 367, 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Liu J, Xie F, Lu Y, Yin C, Shen X, 2019. Co-Delivery of Docetaxel and Salinomycin to Target Both Breast Cancer Cells and Stem Cells by PLGA/TPGS Nanoparticles. International journal of nanomedicine 14, 9199–9216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaonkar RH, Ganguly S, Dewanjee S, Sinha S, Gupta A, Ganguly S, Chattopadhyay D, Chatterjee Debnath M, 2017. Garcinol loaded vitamin E TPGS emulsified PLGA nanoparticles: preparation, physicochemical characterization, in vitro and in vivo studies. Scientific reports 7, 530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel MK, Khanna P, Kishore J, 2010. Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate. Int. J. Ayurveda Res 1, 274–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino R, Tanimura S, Watanabe K, Kataoka T, Kohno M, 2001. Blockade of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway induces marked G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in tumor cells in which the pathway is constitutively activated: up-regulation of p27(Kip1). J. Biol. Chem 276, 2686–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer AK, Singh A, Ganta S, Amiji MM, 2013. Role of integrated cancer nanomedicine in overcoming drug resistance. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 65, 1784–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat AA, Merritt WM, Coffey D, Lin YG, Patel PR, Broaddus R, Nugent E, Han LY, Landen CN Jr., Spannuth WA, Lu C, Coleman RL, Gershenson DM, Sood AK, 2007. Clinical and biological significance of vascular endothelial growth factor in endometrial cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 13, 7487–7495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielbik M, Krzyzanowski D, Pawlik B, Klink M, 2018. Cisplatin-induced ERK1/2 activity promotes G1 to S phase progression which leads to chemoresistance of ovarian cancer cells. Oncotarget 9, 19847–19860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko G, Kim T, Ko E, Park D, Lee Y, 2019. Synergistic Enhancement of Paclitaxel-induced Inhibition of Cell Growth by Metformin in Melanoma Cells. Dev Reprod 23, 119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo H-M, VanBrocklin M, McWilliams MJ, Leppla SH, Duesbery NS, Woude GFV, 2002. Apoptosis and melanogenesis in human melanoma cells induced by anthrax lethal factor inactivation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99, 3052–3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dréno B, Atkinson V, Liszkay G, Maio M, Mandalà M, Demidov L, Stroyakovskiy D, Thomas L, de la Cruz-Merino L, Dutriaux C, Garbe C, Sovak MA, Chang I, Choong N, Hack SP, McArthur GA, Ribas A, 2014. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med 371, 1867–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Carlino MS, Rizos H, 2020. Dosing of BRAK and MEK Inhibitors in Melanoma: No Point in Taking a Break. Cancer Cell 38, 779–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhao GD, Shi Z, Qi LL, Zhou LY, Fu ZX, 2016. The Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway and its role in the occurrence and development of HCC. Oncology letters 12, 3045–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Naguib YW, Cui Z, 2017. In vivo distribution of zoledronic acid in a bisphosphonate-metal complex-based nanoparticle formulation synthesized by a reverse microemulsion method. Int. J. Pharm 526, 69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Yang Q, 2019. Effect of PD98059 on chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer through ERK1/2 pathway. J BUON 24, 1837–1844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Das M, Liu Y, Huang L, 2018. Targeted drug delivery to melanoma. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 127, 208–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GV, Eroglu Z, Infante J, Patel S, Daud A, Johnson DB, Gonzalez R, Kefford R, Hamid O, Schuchter L, Cebon J, Sharfman W, McWilliams R, Sznol M, Redhu S, Gasal E, Mookerjee B, Weber J, Flaherty KT, 2018. Long-Term Outcomes in Patients With BRAF V600-Mutant Metastatic Melanoma Who Received Dabrafenib Combined With Trametinib. J. Clin. Oncol 36, 667–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M, Atkinson V, Mandalà M, Chiarion-Sileni V, Larkin J, Nyakas M, Dutriaux C, Haydon A, Robert C, Mortier L, Schachter J, Schadendorf D, Lesimple T, Plummer R, Ji R, Zhang P, Mookerjee B, Legos J, Kefford R, Dummer R, Kirkwood JM, 2017. Adjuvant Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Stage III BRAF-Mutated Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med 377, 1813–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKeigan JP, Collins TS, Ting JP, 2000. MEK inhibition enhances paclitaxel-induced tumor apoptosis. The Journal of biological chemistry 275, 38953–38956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaid HM, Horwitz SB, 2001. Selective potentiation of paclitaxel (taxol)-induced cell death by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibition in human cancer cell lines. Mol. Pharmacol 60, 290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib YW, Cui Z, 2014. Nanomedicine: the promise and challenges in cancer chemotherapy. Adv Exp Med Biol 811, 207–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib YW, Givens BE, Ho G, Yu Y, Wei SG, Weiss RM, Felder RB, Salem AK, 2020. An injectable microparticle formulation for the sustained release of the specific MEK inhibitor PD98059: in vitro evaluation and pharmacokinetics. Drug Deliv Transl Res 11, 182–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib YW, Rodriguez BL, Li X, Hursting SD, Williams RO 3rd, Cui Z, 2014. Solid lipid nanoparticle formulations of docetaxel prepared with high melting point triglycerides: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Molecular pharmaceutics 11, 1239–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q, Mu H, 2016. The potential of protein-nanomaterial interaction for advanced drug delivery. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 225, 121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin W, Quan G, Sun Y, Chen M, Yang P, Feng D, Wen T, Hu X, Pan X, Wu C, 2020. Dissolving Microneedles with Spatiotemporally controlled pulsatile release Nanosystem for Synergistic Chemophotothermal Therapy of Melanoma. Theranostics 10, 8179–8196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas A, Lawrence D, Atkinson V, Agarwal S, Miller WH Jr., Carlino MS, Fisher R, Long GV, Hodi FS, Tsoi J, Grasso CS, Mookerjee B, Zhao Q, Ghori R, Moreno BH, Ibrahim N, Hamid O, 2019. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition with PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nat. Med 25, 936–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena V, Naguib Y, Hussain MD, 2012. Folate receptor targeted 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) loaded polymeric nanoparticles for breast cancer. Colloids and surfaces. B, Biointerfaces 94, 274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scripture CD, Figg WD, Sparreboom A, 2006. Peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel: recent insights and future perspectives. Curr Neuropharmacol 4, 165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, Gonzalez R, Pavlick AC, Weber JS, McArthur GA, Hutson TE, Moschos SJ, Flaherty KT, Hersey P, Kefford R, Lawrence D, Puzanov I, Lewis KD, Amaravadi RK, Chmielowski B, Lawrence HJ, Shyr Y, Ye F, Li J, Nolop KB, Lee RJ, Joe AK, Ribas A, 2012. Survival in BRAF V600–Mutant Advanced Melanoma Treated with Vemurafenib. N. Engl. J. Med 366, 707–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, He J, Ruan H, Wang Y, 2019. In vitro and in vivo cytotoxic effects of chrysoeriol in human lung carcinoma are facilitated through activation of autophagy, sub-G1/G0 cell cycle arrest, cell migration and invasion inhibition and modulation of MAPK/ERK signalling pathway. J BUON 24, 936–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R, Sato N, Yanai K, Akiyoshi T, Nagai S, Wada J, Koga K, Mibu R, Nakamura M, Katano M, 2009. Enhancement of paclitaxel-induced apoptosis by inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in colon cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 29, 261–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Martelotto L, Baslan T, Vides A, Solomon M, Mai TT, Chaudhary N, Riely GJ, Li BT, Scott K, Cechhi F, Stierner U, Chadalavada K, de Stanchina E, Schwartz S, Hembrough T, Nanjangud G, Berger MF, Nilsson J, Lowe SW, Reis-Filho JS, Rosen N, Lito P, 2017. An approach to suppress the evolution of resistance in BRAFV600E-mutant cancer. Nat. Med 23, 929–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Tang JZ, Fei X, Li Y, Song Y, Qian Z, Peng Q, 2021. Can nanoparticles and nanoprotein interactions bring a bright future for insulin delivery? Acta pharmaceutica Sinica. B 11, 651–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Zhu G, Lu B, Qian Z, Peng Q, 2020. Protein corona formed in the gastrointestinal tract and its impacts on oral delivery of nanoparticles. Medicinal research reviews. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Chen X, Zeng W, Peng C, Huang G, Li X, Ouyang Z, Luo Y, Xu X, Xu B, Wang W, He R, Zhang X, Zhang L, Liu J, Knepper TC, He Y, McLeod HL, 2016. Propranolol induced G0/G1/S phase arrest and apoptosis in melanoma cells via AKT/MAPK pathway. Oncotarget 7, 68314–68327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]