Abstract

Introduction:

As life expectancy improves globally, the burden of elderly trauma continues to increase. Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to have the most rapid growth in its elderly demographic. Consequently, we sought to examine the trends in characteristics and outcomes of elderly trauma in a tertiary care hospital in Malawi.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective analysis of adult patients in the trauma registry at Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) in Lilongwe, Malawi from 2011–2017. Patients were categorized into elderly (≥ 65 years) and non-elderly (18–64 years). Bivariate analysis compared the characteristics and outcomes of elderly vs. non-elderly patients. The elderly population was then examined over the study period. Poisson regression modeling was used to determine the risk of mortality among elderly patients over time.

Results:

Of 63,699 adult trauma patients, 1,925 (3.0%) were aged ≥ 65 years. Among the elderly, the most common mechanism of injury was falls (n = 725 [37.7%]) whereas vehicle or bike collisions were more common in the non-elderly (n = 15,967 [25.9%]). Fractures and dislocations were more prevalent in the elderly (n = 808 [42.0%] vs. 9,133 [14.8%], p < 0.001). In-hospital crude mortality for the elderly was double the non-elderly group (4.8% vs. 2.4%, p < 0.001). Elderly transfers, surgeries, and length of stay significantly increased over the study period but mortality remained relatively unchanged. When adjusted for injury severity and transfer status, there was no significant difference in risk of in-hospital mortality over time.

Conclusion:

At KCH, the proportion of elderly trauma patients is slowly increasing. Although healthcare resource utilization has increased over time, the overall trend in mortality has not improved. As the quality of care for the most vulnerable populations is a benchmark for the success of a trauma program, further work is needed to improve the trend in outcomes of the elderly trauma population in Malawi.

Keywords: Elderly trauma, Trauma, Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Trauma is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide, accounting for over 5 million deaths each year [1]. While trauma has traditionally been considered a disease of the young, with the increasingly aging global population, there has been a concomitant increase in the incidence of elderly trauma [2]. Life expectancy is steadily increasing globally, with the most rapid growth now occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) with the greatest increase in life expectancy is expected to occur in sub-Saharan Africa [3,4]. In 2020 the fewest number of people over the age of 60 years were located in Africa but by 2050 this number is anticipated to triple, matching that of Europe and surpassing the Americas [5]. Consequently, as the sub-Saharan African population ages, the prevalence of traumatic injury among older adults is expected to increase.

The elderly are uniquely at risk for traumatic injury due to visual and auditory deficits, postural instability, and polypharmacy that often accompany advancing age. Despite representing a smaller proportion of the overall trauma population, elderly patients bear a disproportionate burden of morbidity and mortality due to frailty and reduced physiologic reserve [6]. While early, often aggressive care is associated with improved survival in elderly trauma patients in high-income countries [7,8], those in LMICs face the additional challenge of healthcare systems with limited resources and training to care for an aging population. A study surveying medical schools in eleven countries across sub-Saharan Africa found that only 4% provide elderly-specific medical training [9]. Access to health care is also limited in elderly persons in sub-Saharan Africa as compared to their younger counterparts, often related to both income and limited mobility [5].

Despite these unique challenges facing elderly trauma patients, there is limited data on the characteristics and outcomes of elderly trauma patients in resource-limited settings and how they have changed over time with the increasing age of this population. As we have previously examined this population at a tertiary care center in Malawi [10], we now seek to expand upon this prior research by examining the trends in elderly trauma at this institution over time.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of data collected in the trauma registry at Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) in Lilongwe, Malawi. KCH is a 900-bed tertiary care center that serves eight districts in the central region of Malawi, a catchment of almost 7 million persons. The hospital has a 4-bed emergency department, a 4-bed high dependency unit (HDU), a 6-bed intensive care unit (ICU), and a 31-bed burn unit. Trauma and orthopedic surgery services are staffed 7 days a week by consultant surgeons, surgical residents, and clinical officers. The trauma registry collects demographic and clinical information and outcomes on all patients presenting to the KCH emergency department with traumatic injury.

We included all patients ≥ 18 years of age in the KCH trauma registry from January 2011 to December 2017. Subjects without a documented age (n = 403 [0.6%]) or final disposition (n = 627 [1.0%]) were excluded from the analysis. Age was dichotomized into elderly and non-elderly. Elderly was defined as age ≥ 65 years based on the convention used by the World Health Organization (WHO) [11].

We first performed a bivariate analysis to compare the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the elderly and non-elderly trauma populations, using chi-squared tests for categorical variables, student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, and Kruskal-Wallis test for non-parametric continuous variables. The clinical data compared included mechanism of injury, type of the most severe injury, neurologic status, injury severity, operative intervention, and in-hospital mortality. Neurologic status was measured using the Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive (AVPU) scale, a crude measure of consciousness that is comparable to the Glasgow coma scale [12]. Injury severity was measured using the Malawi Trauma Score (MTS), a tool ranging from 2 to 32 that incorporates age, sex, anatomic location of injury, AVPU, and absence or presence of a radial pulse on arrival [13].

The primary aim of our study was to examine trends in characteristics and outcomes of elderly trauma patients presenting to KCH over the study period of 2010 – 2017. The primary outcome was crude, in-hospital mortality. Using descriptive statistics, we examined the aforementioned demographic and clinical characteristics of the elderly population across the study period. We then used a modified Poisson regression model to estimate the risk ratio for in-hospital mortality by year of presentation [14,15]. Potential confounders identified in the bivariate analysis were incorporated into the model and a change-in-effect method was used to remove covariates that did not substantially contribute to the model ( > 10%). We report unadjusted risk ratios along with adjusted risk ratios from the final, reduced model’s estimates and 95% confidence intervals.

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA V.16 (StataCorp, College Park, TX). This study was approved by the Malawi National Health Services Review Committee and the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board. A waiver of consent was obtained from both approving organizations.

Results

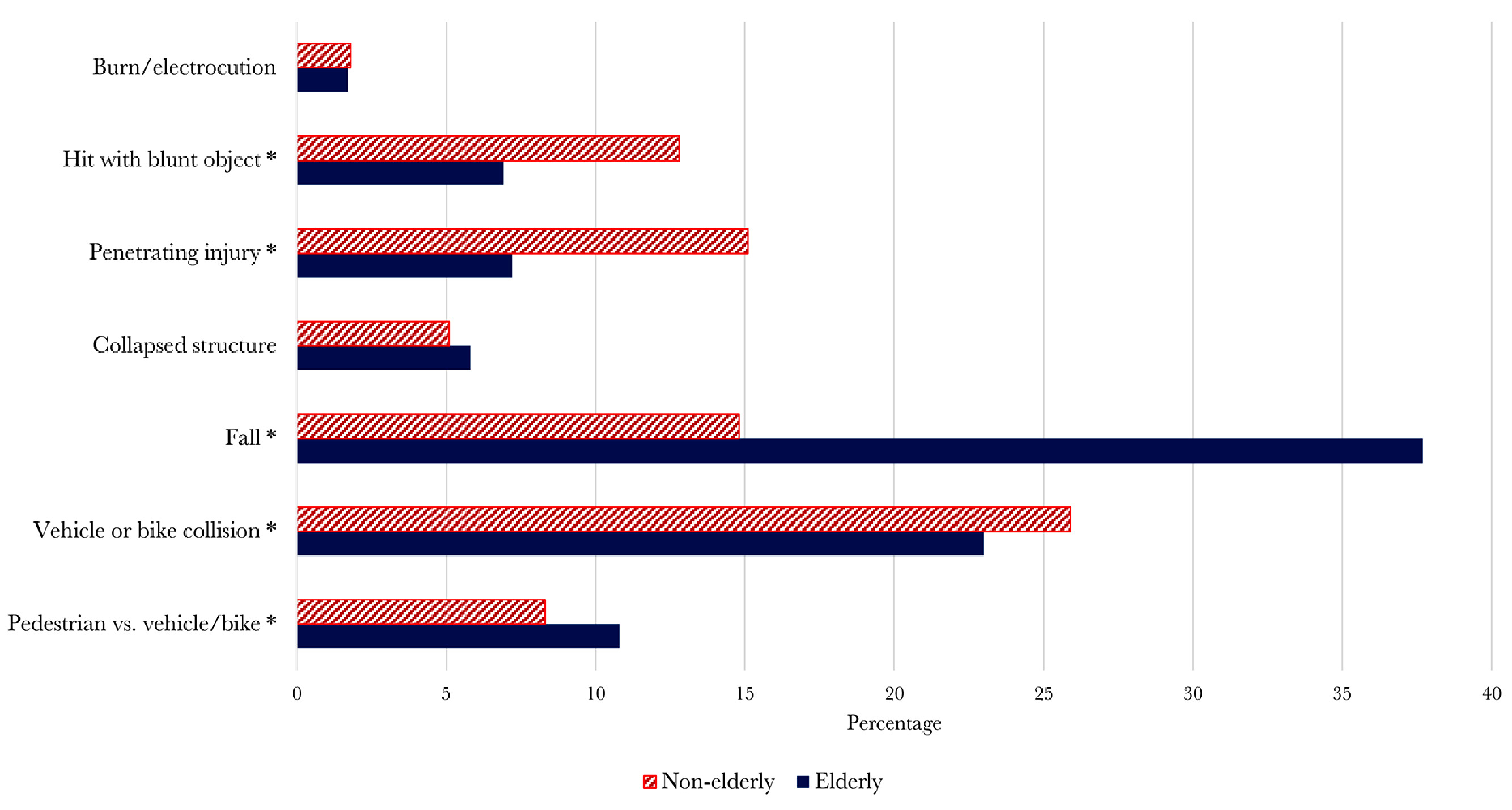

Over the 7-year study period, 63,699 adult patients presented to the KCH emergency department with traumatic injury. Of this cohort, 1,925 (3.0%) were aged ≥ 65 years. The median age of elderly patients was 70 years (IQR 68–76) compared to 30 years (IQR 24–37) in the non-elderly group (Table 1). The majority of both groups were male; however, the elderly population had a slightly higher proportion of female patients (n = 679 [35.3%] vs. 13,937 [22.6%], p < 0.001). Among the elderly, the most common mechanism of injury was falls (n = 725 [37.7%] vs. 9,123 [14.8%], p < 0.001). In contrast, the mechanism of injury among the non-elderly was most frequently vehicle or bike collisions (n = 15,967 [25.9%] vs. 442 [23.0%], p = 0.004) (Fig. 1). While soft tissue injuries were the most common injury overall, fractures and dislocations were significantly more prevalent in the elderly than non-elderly patients (n = 808 [42.0%] vs. 9,133 [14.8%], p < 0.001) ( Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of elderly (65+ years) vs. non-elderly adult trauma patients from 2011–2017.

| Elderly N=1,925 (3.0%) | Non-elderly N=61,774 (97.0%) | All N =63,699 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Age (years), median (IQR) | 70 (68–76) | 30 (24–37) | 30 (24–38) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 679 (35.3) | 13,937 (22.6) | 14,616 (23.0) | <0.001 |

| Blunt Injury, n (%) | 1,629 (84.6) | 42,178 (68.3) | 43,807 (68.8) | <0.001 |

| Most severe injury, n (%) | ||||

| Soft Tissue Injury | 822 (42.7) | 41,625 (67.4) | 42,447 (66.6) | <0.001 |

| Fracture/dislocation | 808 (42.0) | 9,133 (14.8) | 9,941 (15.6) | |

| Injury to Internal Organ | 23 (1.2) | 767 (1.2) | 790 (1.2) | |

| Traumatic Brain or Spine Injury | 120 (6.2) | 3,141 (5.1) | 3,261 (5.1) | |

| Multi-system Trauma, n (%) | 585 (30.4) | 24,297 (39.3) | 24,882 (39.1) | <0.001 |

| Injury Setting, n (%) | ||||

| Home | 882 (45.8) | 15,859 (25.7) | 16,741 (26.3) | <0.001 |

| Work/school | 121 (6.3) | 7,974 (12.9) | 8,095 (12.7) | |

| Outdoors/road | 878 (45.6) | 37,180 (60.2) | 38,058 (59.8) | |

| Transferred, n (%) | 717 (37.3) | 9,326 (15.1) | 10,043 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| Initial AVPU, n (%) | ||||

| Alert | 1,715 (89.1) | 54,311 (87.9) | 56,026 (88.0) | 0.1 |

| Responds to Voice | 154 (8.0) | 5,920 (9.6) | 6,074 (9.5) | |

| Responds to Pain | 9 (0.5) | 244 (0.4) | 254 (0.4) | |

| Unresponsive | 37 (1.9) | 955 (1.6) | 992 (1.6) | |

| Malawi Trauma Score, mean (SD) | 9.1 (4.1) | 8.7 (3.6) | 8.7 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| Admitted, n (%) | 750 (39.0) | 9,388 (15.2) | 10,138 (15.9) | <0.001 |

| Underwent Surgery, n (%) | 128 (6.7) | 2,861 (4.6) | 2,989 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (days), median (IQR) | 15 (5–35) | 6 (2–16) | 6 (2–17) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 93 (4.8) | 1,460 (2.4) | 1,553 (2.4) | <0.001 |

AVPU = Alert, voice, pain, unresponsive scale, ED = Emergency department

Fig. 1.

Common mechanisms of injury of Non-elderly (18–64 years) vs. Elderly (65+ years) trauma patients (* p < 0.05).

Elderly patients were more frequently injured at home than non-elderly patients (n = 882 [45.8%] vs. 15,859 [25.7%], p < 0.001) (Table 1). A higher prevalence of elderly patients were transferred to KCH from an outside facility (n = 717 [37.3%] vs. 9,326 [15.1%], p < 0.001). Similar to the non-elderly group, elderly patients were frequently alert on arrival (n = 1,715 [89.1%] vs. 54,311 [87.9%], p < 0.13) with clinically similar low, but statistically significantly higher, MTS scores (mean MTS 9.1 [SD 4.1] vs. 8.7 [SD 3.6], p < 0.001). While the majority of both groups were able to treated in the emergency department and discharged home, a higher proportion of the elderly group required admission (n = 750 [39.0%] vs. 9,388 [15.2%], p < 0.001). Elderly patients also under went a higher proportion of surgeries (n = 128 [6.7%] vs. 2,861 [4.6%], p < 0.001) and required a significantly longer length of stay (median 15 days [IQR 5-35] vs. 6 days [IQR 2-16], p < 0.001). Crude, in-hospital mortality for the elderly was double that of the non-elderly group at 4.8% vs. 2.4% (p < 0.001).

Over the study period, the demographics of the elderly population remained stable (Table 2). Falls were consistently the most common mechanism of injury but the proportion of pedestrians struck by vehicles did increase over time (7.8% in 2011 vs. 11.4% in 2017, p = 0.03) while the proportion of vehicle or bike collisions trended down (31.8% in 2011 vs. 24.0% in 2017, p = 0.03). The extremities were the most severely injured anatomic location across the study period. Additionally, the prevalence of elderly patients transferred from outside facilities increased significantly, from 29.5% in 2011 to 39.8% in 2017 (p < 0.001). Despite a lower injury severity score (median MTS 9 [IQR 8-10] in 2011 vs. 8 [IQR 6-10] in 2017, p = 0.002), a consistently high proportion of elderly patients required admission over time (43.8% in 2011 vs. 37% in 2017, p = 0.08). Elderly patients also under went more surgical interventions over the study period (1.4% in 2011 vs. 4.1% in 2017, p < 0.001) and the median length of stay significantly increased (16 days [IQR 5-37] in 2011 vs. 21 days [IQR 8-42] in 2017, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of elderly patients (65+) with traumatic injury by year.

| 2011 n=217 (2.5%) |

2012 n=286 (3.0%) |

2013 n=317 (3.2%) |

2014 n=303 (3.1%) |

2015 n=281 (3.1%) |

2016 n=275 (3.2%) |

2017 n=246 (3.1%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 70 (68–76) | 70 (68–76) | 70 (68–76) | 71 (68–76) | 70 (68–77) | 71 (69–77) | 70 (67–77) | 0.7 |

| Female, n (%) | 66 (30.4) | 106 (37.1) | 117 (36.6) | 104 (34.3) | 93 (33.1) | 100 (36.4) | 94 (38.4) | 0.6 |

| Unintentional, n (%) | 190 (88.4) | 243 (85.6) | 243 (76.7) | 254 (83.8) | 245 (87.8) | 233 (85.0) | 212 (86.9) | <0.001 |

| Mechanism, n (%) | ||||||||

| Pedestrian vs. vehicle/bike | 17 (7.8) | 28 (9.8) | 44 (13.9) | 35 (11.6) | 26 (9.3) | 30 (10.9) | 28 (11.4) | 0.03 |

| Motor vehicle/bike collision | 69 (31.8) | 56 (19.6) | 64 (20.2) | 61 (20.1) | 65 (23.1) | 68 (24.7) | 59 (24.0) | |

| Fall | 82 (37.8) | 118 (41.3) | 98 (30.9) | 120 (39.6) | 114 (40.6) | 102 (37.1) | 91 (37.0) | |

| Collapsed structure | 11 (5.1) | 15 (5.2) | 25 (7.9) | 18 (5.9) | 16 (5.7) | 11 (4.0) | 16 (6.5) | |

| Stabbed or cut | 2 (0.9) | 17 (5.9) | 17 (5.4) | 15 (5.0) | 18 (6.4) | 18 (6.6) | 12 (4.9) | |

| Punched/kicked or hit with blunt object | 5 (2.3) | 23 (8.0) | 28 (8.8) | 23 (7.6) | 15 (5.3) | 18 (6.6) | 12 (4.9) | |

| Other | 28 (12.9) | 28 (9.8) | 39 (12.3) | 27 (8.9) | 25 (8.9) | 18 (6.6) | 21 (8.5) | |

| Polytrauma, n (%) | 71 (32.7) | 89 (31.1) | 110 (34.7) | 86 (28.4) | 74 (26.3) | 81 (29.5) | 74 (30.1) | 0.3 |

| Malawi Trauma Score. Median (IQR) | 9 (8–10) | 9 (6–9) | 9 (6–12) | 8 (8–9) | 9 (6–9) | 9 (6–12) | 8 (6–10) | 0.002 |

| Worse AVPU Score, n (%) | ||||||||

| Responds to Pain Only | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Unresponsive | 4 (1.8) | 3 (1.1) | 12 (3.8) | 4 (1.3) | 2 (0.7) | 5 (1.8) | 7 (2.9) | |

| Transferred, n (%) | 64 (29.5) | 102 (35.7) | 95 (30.0) | 119 (39.3) | 106 (37.7) | 133 (48.4) | 98 (39.8) | <0.001 |

| Admitted, n (%) | 95 (43.8) | 121 (42.3) | 114 (36.0) | 118 (38.9) | 92 (32.7) | 119 (43.3) | 91 (37.0) | 0.08 |

| Underwent Surgery, n (%) | 3 (1.4) | 46 (16.1) | 23 (7.3) | 15 (5.0) | 14 (5.0) | 17 (6.2) | 10 (4.1) | 0.001 |

| Length of Stay (days), median (IQR) | 16 (5–37) | 14 (2–31) | 12 (3–30) | 20 (6–39) | 14 (4–33) | 15 (6–38) | 21 (8–42) | <0.001 |

| Crude Mortality, n (%) | 18 (8.3) | 11 (3.9) | 19 (6.0) | 9 (3.0) | 9 (3.2) | 14 (5.1) | 13 (5.3) | 0.08 |

AVPU = Alert, voice, pain, unresponsive scale, ED = Emergency department

The overall in-hospital mortality of elderly patients has not significantly improved (Table 2). It has remained relatively stable ranging from 8.3% in 2011 to 5.3% in 2017 (p = 0.08). Using 2011 as the referent year, there have been no significant changes in the relative risk of in-hospital death over the study period (Table 3). The unadjusted risk of mortality was improved in 2014 (RR 0.36 [95% CI 0.16–0.78], p = 0.01) and 2015 (RR 0.39 [95% CI 0.18–0.84], p = 0.02) when compared to 2011. However, after adjustment for injury severity and transfer status, there was no significant difference in risk of in-hospital mortality over time. Additionally, these in-hospital mortality rates have remained significantly higher than non-elderly adults, only approaching the non-elderly mortality rate from 2014 –2015 and increasing again in subsequent years (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted risk of mortality in the elderly (65+) trauma population by year of injury. Risk ratios adjusted for Malawi Trauma Score and transfer status.

| Year | Unadjusted Risk Ratio of Mortality | 95% CI | p value | Adjusted Risk Ratio of Mortality | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 2012 | 0.46 | 0.22 – 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.86 | 0.42 – 1.78 | 0.7 |

| 2013 | 0.72 | 0.39 – 1.34 | 0.3 | 1.04 | 0.59 – 1.84 | 0.9 |

| 2014 | 0.36 | 0.16 – 0.78 | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.23 – 1.35 | 0.2 |

| 2015 | 0.39 | 0.18 – 0.84 | 0.02 | 1.40 | 0.66 – 2.96 | 0.4 |

| 2016 | 0.61 | 0.31 – 1.21 | 0.2 | 1.13 | 0.58 – 2.20 | 0.7 |

| 2017 | 0.64 | 0.32 – 1.27 | 0.2 | 0.83 | 0.44 – 1.58 | 0.6 |

Fig. 2.

In-hospital mortality (%) of elderly (age ≥65 years) vs. non-elderly (age 18–64 years) trauma patients from 2011 – 2017.

Discussion

As the global life-expectancy improves, the burden of traumatic injury among the elderly will continue to increase. Sub-Saharan Africa is particularly vulnerable to this demographic shift as its population is expected to age the most rapidly [3]. Considering the resource constraints of many healthcare systems in the region, there is an acute need to examine the current trends in elderly trauma to inform health policy in the care of the elderly population across diseases processes. In addition, given the importance of caring for the most vulnerable in a population, elderly trauma outcomes are a useful benchmark for the improvement of a trauma system.

In Malawi, the average life expectancy over our study period increased from 57.2 years in 2011 to 63.3 years in 2017 [16]. Over this time span, the proportion of elderly trauma patients also increased from 2.5% to 3.1%. We found that the clinical characteristics of elderly trauma patients remained relatively stable, with most patients suffering extremity injuries due to falls. Notably, the trends in proportion of hospital transfers, surgeries, and length of hospital stay have significantly increased. In addition to the growing number of elderly patients, this increase may reflect the expanding surgical workforce at KCH. As a result of the surgical residency program, the number of consultant surgeons at KCH doubled over the study period while surgical capacity at district hospitals remained low. [17] Despite this increasing utilization of healthcare resources, in-patient mortality has not significantly improved over time with the relative mortality risk the same for elderly patients in 2017 as it was in 2011.

The increasing burden of elderly patients at our center reflects a pattern seen throughout the region. While there has been limited study of the trends over time, cross-sectional hospital-based studies have shown an overall increase in the proportion of elderly patients presenting to accident and emergency rooms across sub-Saharan Africa. For example, in albeit heterogeneous reports from the 1990s to early 2000s, the proportion of elderly trauma patients was 2% in Nigeria, 3% in Kenya, and 4% in Uganda and Tanzania compared to 6% in Nigeria, 5% in Kenya, and 16% in Uganda in reports from the last decade [18–26]. Of studies that stratify mechanism by age, the cause of injury was also most commonly fall or traffic-related among elderly trauma patients [18,25,27,28]. Mortality rates of elderly trauma patients are more variable throughout the region. In Pietermaritzburg, South Africa mortality of elderly trauma patients was 11.4%, likely owing to their higher proportion of penetrating injury [28]. Similarly in the Shinyanga region of Tanzania, the mortality rate of elderly trauma patients reached 14.9% [29]. In our study population, the mortality rate of elderly trauma patients has remained comparatively low over time.

Our finding that mortality in elderly trauma patients was double that of non-elderly trauma patients is consistent with data from high-income countries (HIC) that also show a higher risk of death for older patients. However, in contrast to the experience in Malawi, mortality rates in high-income settings have slowly improved overtime [30]. Improved outcomes among elderly trauma patients in HIC have been achieved through dedicated elderly-specific triage and resuscitation protocols as well as advances in non-surgical interventions and therapies [30–32]. LMICs face several barriers to successful implementation of these strategies. It is widely accepted that the elderly are often under-triaged due to seemingly benign mechanisms of injury, unreliable hemodynamics, and polypharmacy-related blunting of the physiologic response to trauma [33,34]. However, developing countries often lack the diagnostic adjuncts utilized in HICs to recognize under-triaged injuries. Guidelines developed to circumvent this phenomenon, such as those developed by the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, have not been investigated in LMICs [35]. Additionally, risk stratification and triage tools often used in LMICs are challenging in this population as the revised trauma score is less valid in the elderly and the Kampala Trauma Score has not been tested in this population [36, 37]. Finally, while many elderly trauma patients are preemptively admitted to the intensive care unit in HICs, access to a higher level of care is limited in this setting due to lack of available facilities, equipment, and trained staff [38,39].

While there are several limitations to improving elderly trauma care in resource-limited settings, our study has highlighted some potential targets for both prevention and intervention strategies that warrant further study, especially in fall prevention. Solutions such as increasing access to mobility assist devices (i.e. walkers and canes), exercise programs, vitamin D3 supplementation, and physical modification of the home have been shown to be effective in HICs but little research has been done on the feasibility of their implementation in LMICs [40–43]. A randomized clinical trial investigating an individualized, multifactorial prevention program consisting of exercise, home modification, medication and physiologic review, and education was performed in Malaysia but no difference in fall recurrence, rate of fall, or time to first fall was found, with the authors speculating that culturally-relevant factors may have contributed to the program’s lack of success [44]. In sub-Saharan Africa, literature on elderly falls has focused primarily on acute injuries and with little research or data on fall risk reduction [45]. In order to improve elderly trauma outcomes in these resource-limited settings, further study on risk factors for falls and prevention strategies within the local and cultural context are needed for public health prioritization and planning.

This study is limited in its retrospective design as it is unable to discern the specific gaps in care that exist within our elderly trauma population. This database also lacks information on pre-hospital mortality. Additionally, while there was no collection of data on co-morbidities, many of our cohort lack access to the primary care services that would have diagnosed any pre-existing conditions. Finally, this study is limited by the challenge of defining elderly in a population with a lower life expectancy than many high-income countries. While 65 years is a widely used cut-off in HICs and recommended by the WHO, definitions ranging from 50–65 are often used in studies conducted in Africa based on regional life expectancy, social roles, and social security programs. [46–48] As a greater importance is placed on physiologic age than chronological age, elderly can also be defined by functional capacity rather than years, although this was not possible in this study due to data limitations. [11,49] Further, lack of access to reliable documentation and birth records often limits the accuracy of recorded ages. [50] Despite these limitations, this study was able to provide a broad overview of the trends in elderly trauma in a resource-limited setting where life expectancy has been substantially improving over the last twenty years.

Conclusion

The elderly population in sub-Saharan Africa is rapidly increasing. As the elderly population grows, the demographics of the trauma population will also continue to shift in age. At KCH, the proportion of elderly trauma patients is already slowly increasing. Although healthcare resource utilization has increased over time, the overall trend in in-hospital mortality has not improved. As the quality of care for the most vulnerable populations is a benchmark for the success of a trauma program, further work is needed to improve the trend in outcomes of the elderly trauma population in Malawi.

Acknowledgments

Funding support

This work was funded by the Department of Surgery at the University of North Carolina and The National Institutes of Health, Fogarty International Center (Laura N. Purcell and Brittney Williams: grant D43TW009340)

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors has no conflict of interest to disclose. The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

References

- [1].World Health Organization. Injuries and violence: the facts 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/149798.

- [2].Mcmahon DJ, Schwab W, Kauder D. Comorbidity and the elderly trauma patient. World J Surg 1996;20:1113–20. doi: 10.1007/s002689900170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].World Health Organization. Ageing and health 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

- [4].Institution for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Findings from the global burden of disease study 2017. Seattle, WA: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [5].He W, Aboderin I, Adjaye-Gbewonyo D, U.S. Census Bureau, International population reports. Africa aging: 2020. Washington DC: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Aschkenasy MT, Rothenhaus TC. Trauma and Falls in the Elderly. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2006;24:413–32. doi: 10.1016/J.EMC.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hashmi A, Ibrahim-Zada I, Rhee P, Aziz H, Fain MJ, Friese RS, et al. Predictors of mortality in geriatric trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;76:894–901. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182ab0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Velmahos G, Alo K, Newton E, Murray J, et al. Effect on outcome of early intensive management of geriatric trauma patients. Br J Surg 2002;89:1319–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Frost L, Liddie Navarro A, Lynch M, Campbell M, Orcutt M, Trelfa A, et al. Care of the elderly: survey of teaching in an aging sub-Saharan Africa. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 2015;36:14–29. doi: 10.1080/02701960.2014.925886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gallaher JR, Haac BE, Geyer AJ, Mabedi C, Cairns BA, Charles AG. Injury characteristics and outcomes in elderly trauma patients in sub-Saharan Africa. World J Surg 2016;40:2650–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3622-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].World Health Organization. Men, ageing and health: achieving health across the life span 2001. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66941.

- [12].Kelly CA, Upex A, Bateman DN. Comparison of consciousness level assessment in the poisoned patient using the alert/verbal/painful/unresponsive scale and the glasgow coma scale. Ann Emerg Med 2004;44:108–13. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gallaher J, Jefferson M, Varela C, Maine R, Cairns B, Charles A. The Malawi trauma score: a model for predicting trauma-associated mortality in a resource poor setting. Injury 2019;50:1552–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen W, Qian L, Shi J, Franklin M. Comparing performance between logbinomial and robust Poisson regression models for estimating risk ratios under model misspecification. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:63. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0519-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].The World Bank. Life expectancy at birth, total (years) - Malawi 2019. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=MW.

- [17].Purcell LN, Robinson B, Msosa V, Gallaher J, Charles A. District general hospital surgical capacity and mortality trends in patients with acute abdomen in Malawi. World J Surg 2020;44:2108–15. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05468-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wojda TR, Cornejo K, Valenza PL, Carolan G, Sharpe RP, Mira A-EA, et al. Medical demographics in sub-Saharan Africa: does the proportion of elderly patients in accident and emergency units mirror life expectancy trends? J Emerg Trauma Shock 2016;9:122–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.185278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zheng DJ, Sur PJ, Ariokot MG, Juillard C, Ajiko MM, Dicker RA. Epidemiology of injured patients in rural Uganda: a prospective trauma registry’s first 1000 days. PLoS One 2021;16:e0245779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Botchey IM, Hung YW, Bachani AM, Paruk F, Mehmood A, Saidi H, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of injuries in Kenya: a multisite surveillance study. Surgery 2017;162:S45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Robsam SO, Ihechi EU, Olufemi WO. Human bite as a weapon of assault. Afr Health Sci 2018;18:79–89. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v18i1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ogunmola OJ, Olamoyegun MA. Patterns and outcomes of medical admissions in the accident and emergency department of a tertiary health center in a rural community of Ekiti, Nigeria. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2014;7:261. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.142744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rutta E, Mutasingwa D, Ngallaba S, Berege Z. Epidemiology of injury patients at Bugando Medical Centre. Tanzania. East Afr Med J 2001;78:161–4. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v78i3.9085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Saidi H, Kahoro P. Experience with road traffic accident victims at the Nairobi hospital. East Afr Med J 2001;78:441–4. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v78i8.8999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kobusingye OC, Guwatudde D, Owor G, Left RR. Citywide trauma experience in Kampala, Uganda: a call for intervention. Inj Prev 2002;8:133–6. doi: 10.1136/ip.8.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Elechi EN, Etawo SU. Pilot study of injured patients seen in the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. Nigeria. Injury 1990;21:234–8. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(90)90011-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mock CN, Denno D, Conklin E, Rivara F. Admissions for injury at a rural hospital in Ghana: implications for prevention in the developing world. Am J Public Health 1995;85972–31. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Da Costa J-P, Laing J, Kong VY, Bruce JL, Laing GL, Clarke DL. A review of geriatric injuries at a major trauma centre in South Africa. South African Med J 2019;110:44. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2019.v110i1.14100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Ngayomela IH, Mbelenge N, Dass RM, Mchembe M, et al. Geriatric injuries among patients attending a regional hospital in Shinyanga Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res 2012;14. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v14i1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Burstow M, Civil I, Hsee L. Trauma in the elderly: demographic trends (1995–2014) in a major New Zealand trauma centre. World J Surg 2019;43:466–75. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bradburn EH, Gross BW, Jammula S, Adams WH, Miller JA. Improved outcomes in elderly trauma patients with the implementation of two innovative geriatric-specific protocols—final report. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2018;84:301–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Peterer L, Ossendorf C, Jensen KO, Osterhoff G, Mica L, Seifert B, et al. Implementation of new standard operating procedures for geriatric trauma patients with multiple injuries: a single level I trauma centre study. BMC Geriatr 2019;19:359. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1380-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Reske-Nielsen C, Medzon R. Geriatric trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2016;34:483–500. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bonne S, Schuerer DJE. Trauma in the older adult: epidemiology and evolving geriatric trauma principles. Clin Geriatr Med 2013;29:137–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Calland JF, Ingraham AM, Martin N, Marshall GT, Schulman CI, Stapleton T, et al. Evaluation and management of geriatric trauma: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:S345–50. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318270191f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Llompart-Pou JA, Pérez-Bárcena J, Chico-Fernández M, Sánchez-Casado M, Raurich JM. Severe trauma in the geriatric population. World J Crit Care Med 2017;6:99–106. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v6.i2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Manoochehry S, Vafabin M, Bitaraf S, Amiri A. A comparison between the ability of revised trauma score and Kampala trauma score in predicting mortality; a meta-analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med 2019;7:e6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Owojuyigbe AM, Adenekan AT, Babalola RN, Adetoye AO, Olateju SOA, Akonoghrere UO. Pattern and outcome of elderly admissions into the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of a low resource tertiary hospital. East Cent African J Surg 2016;21:40. doi: 10.4314/ecajs.v21i2.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lankoandé M, Bonkoungou P, Simporé A, Somda G, Kabore RAF. In hospital outcome of elderly patients in an intensive care unit in a sub-Saharan hospital. BMC Anesthesiol 2018;18:118. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0581-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Moncada LVV, Mire LG. Preventing Falls in Older Persons. Am Fam Physician 2017;96:240–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Crandall M, Duncan T, Mallat A, Greene W, Violano P, Christmas AB, et al. Prevention of fall-related injuries in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2016;81:196–206. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].World Health Organization. Global report on falls prevention in older age 2008. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241563536.

- [43].Kalula SZ, Scott V, Dowd A, Brodrick K. Falls and fall prevention programmes in developing countries: environmental scan for the adaptation of the Canadian Falls prevention curriculum for developing countries. J Safety Res 2011;42:461–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Tan PJ, Khoo EM, Chinna K, Saedon NI, Zakaria MI, Ahmad Zahedi AZ, et al. Individually-tailored multifactorial intervention to reduce falls in the Malaysian Falls Assessment and Intervention Trial (MyFAIT): a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2018;13:e0199219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kalula SZ, deVilliers L, Ross K, Ferreira M. Management of older patients presenting after a fall–an accident and emergency department audit. S Afr Med J 2006;96:718–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wandera SO, Golaz V, Kwagala B, Ntozi J. Factors associated with self-reported ill health among older Ugandans: a cross sectional study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015;61:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Akinyemi RO, Izzeldin IMH, Dotchin C, Gray WK, Adeniji O, Seidi OA, et al. Contribution of noncommunicable diseases to medical admissions of elderly adults in Africa: a prospective, cross-sectional study in Nigeria, Sudan, and Tanzania. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1460–6. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Gómez-Olivé FX, Thorogood M, Clark B, Kahn K, Tollman S. Self-reported health and health care use in an ageing population in the Agincourt subdistrict of rural South Africa. Glob Health Action 2013;6:19305. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kowal P, Dowd JE. Definition of an older person. Proposed working definition of an older person in Africa for the MDS Project. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Paraïso MN, Houinato D, Guerchet M, Aguèh V, Nubukpo P, Preux P-M, et al. Validation of the use of historical events to estimate the age of subjects aged 65 years and over in Cotonou (Benin). Neuroepidemiology 2010;35:12–16. doi: 10.1159/000301715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]