Abstract

It is widely accepted that cellular processes are controlled by protein phosphorylation and has become increasingly clear that protein degradation, localization and conformation as well as protein-protein interaction are the examples of subsequent cellular events modulated by protein phosphorylation. Enamel matrix proteins belong to members of the secretory calcium binding phosphoprotein (SCPP) family clustered on chromosome 4q21, and most of the SCPP phosphoproteins have at least one S-X-E motifs (S; serine, X; any amino acid, E; glutamic acid). It has been reported that mutations in C4orf26 gene, located on chromosome 4q21, are associated with autosomal recessive type of Amelogenesis Imperfecta (AI), a hereditary condition that affects enamel formation/mineralization. The enamel phenotype observed in patients with C4orf26 mutations is hypomineralized and partially hypoplastic, indicating that C4orf26 protein may function at both secretory and maturation stages of amelogenesis. The previous in vitro study showed that the synthetic phosphorylated peptide based on C4orf26 protein sequence accelerates hydroxyapatite nucleation. Here we show the molecular cloning of Gm1045, mouse homologue of C4orf26, which has 2 splicing isoforms. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that the immunolocalization of Gm1045 is mainly observed in enamel matrix in vivo. Our report is the first to show that FAM20C, the Golgi casein kinase, phosphorylates C4orf26 and Gm1045 in cell cultures. The extracellular localization of C4orf26/Gm1045 was regulated by FAM20C kinase activity. Thus, our data point out the biological importance of enamel matrix-kinase control of SCPP phosphoproteins and may have a broad impact on the regulation of amelogenesis and AI.

Keywords: Amelogenesis Imperfecta, chromosome 4 open reading frame 26 (C4orf26), enamel matrix protein, Gm1045, phosphorylation, extracellular localization, splicing variant

Introduction

Amelogenesis is a complex process, which requires multiple matrix proteins and proteinases secreted mainly by ameloblasts for controlling the crystal growth and mineralization in tooth enamel. Amelogenin and Enamelin are major enamel matrix proteins which have been shown to play critical roles in enamel formation, and mutations in these genes are associated with defects in enamel formation in human [1, 2]. Amelogenesis Imperfecta (AI) is a group of inherited conditions characterized by abnormal enamel formation and mineralization. The phenotypes of AI vary depending on their genes, their translated products involved, types of AI and site of mutations [3, 4]. The predominant clinical phenotypes can be classified as enamel hypoplasia, hypomineralization or hypocalcification, and different traits of AI have been reported such as autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive and X-linked types [2, 5, 6]. It has been recently reported that C4orf26 encodes a putative extracellular matrix acidic phosphoprotein, which is mutated in the recessive type of hypomineralized/hypoplastic AI [7]. These findings point to the biological importance of enamel matrix proteins serving as a temporal three-dimensional template for biomineralization.

FAM20C, the Golgi casein kinase, phosphorylates many secretory proteins within S-X-E motifs [8]. Mutations in FAM20C lead to Raine syndrome (OMIM#259775), which was previously recognized as a lethal medical condition [9–11], and it was later identified that patients with non-lethal FAM20C mutations show defective mineralized tissue formation including Amelogenesis Imperfecta [12, 13]. Very recently, than 100 secreted phosphoproteins were identified as genuine FAM20C substrates [14], and these proteins are involved in many biological aspects including lipid homeostasis, wound healing, cell migration and adhesion [14]. C4orf26 is predicted to be a secretory protein due to the presence of signal peptide sequence and absence of any detectable membrane retention motifs [7]. However, it is not currently known whether C4orf26 is indeed a secretory protein and physiologically phosphorylated. Furthermore, the kinase(s) that phosphorylates C4orf26 is not identified.

In the current study, during the process of molecular cloning of Gm1045, a mouse homologue of C4orf26 gene, we identified another transcript variant of this gene. We further demonstrated C4orf26/Gm1045 protein is an extracellular enamel matrix protein that is phosphorylated in cell cultures by FAM20C kinase. Co-transfection of FAM20C wild-type form with an intact kinase activity enhanced the amount of C4orf26/Gm1045 protein in the medium, while co-transfection of FAM20C D478A kinase inactive form prevented from the extracellular localization of C4orf26/Gm1045. Thus, our results highly suggest the biological and pathological significance of this post-translational modification in amelogenesis and AI.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The use of animals and all animal procedures in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Boston University Medical campus (approved protocol number: AN-15050), and all efforts were made to minimize the suffering of the animals. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

Cell culture

Rat dental epithelial cell line, HAT-7 cells [15] and human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (Clontech) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12, Life Technologies) and DMEM (Life Technologies), respectively.

Molecular cloning of human C4orf26 and its mouse homologue, Gm1045, and plasmid construction

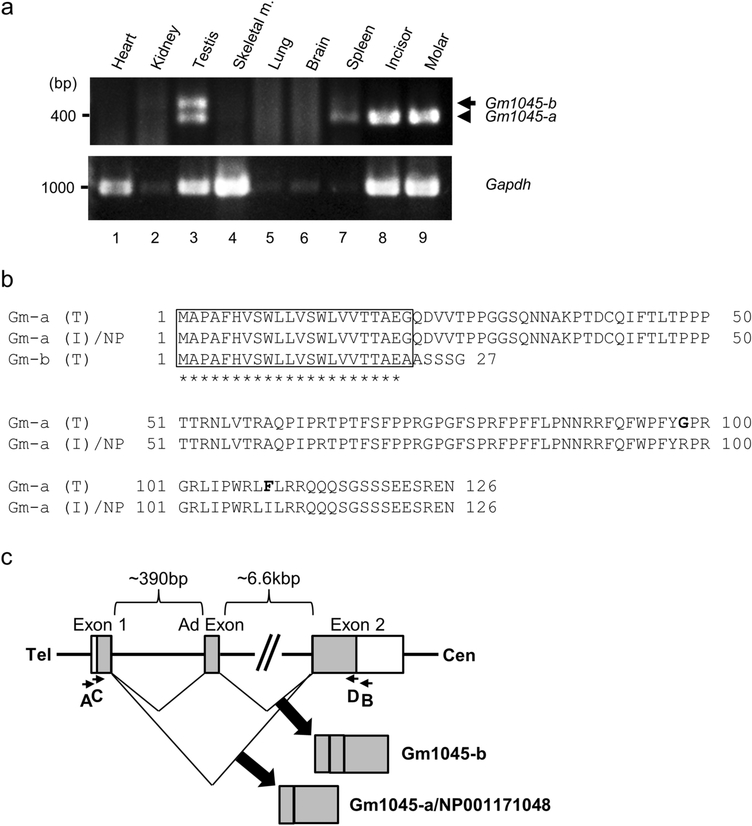

The cDNAs containing the full length sequences of C4orf26 were isolated by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using HotstarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen). The plasmid containing the full length of coding sequence for C4orf26 was purchased (Open Biosystems) and used as a PCR template. The sequences of the primers were as follows; forward primer, 5’-GCGAATTCGCCATGGCTCGCAGACACTGC-3’ and reverse primer, 5’-GCCTCGAGGCTTTCCTCAGATGAGCTTCC-3’. The PCR conditions were as follows: 15 min at 95°C; 30 s at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C, 1.5 min at 72°C for 30 cycles. The PCR products were then ligated into the pcDNA3-HA mammalian expression vector [16], the sequence was verified and 100% identical to that of C4orf26 transcript variant 2 (NCBI Accession number: NM_178497). The plasmid containing the coding sequence of C4orf26 was thus successfully obtained (pcDNA3-C4orf26-HA). The sequences of specific primers against Gm1045 were designed as follows; forward primer A: 5’-CAGAAGCCATGGCTCCAGCTTTCCATG-3’, reverse primer B: 5’-GAATAAGACTGGTGCCGTTACGGCCAG-3’. RT-PCR analysis was performed using various mouse tissue cDNAs derived from heart, kidney, testis, skeletal muscle, lung, brain and spleen (MTC panel I, Clontech) and those from postnatal day 14 mouse incisor and molar teeth (C57BL/6 strain). Nested PCR was performed with another set of primers, i.e. forward primer C: 5’-GCGAATTCGCCATGGCTCCAGCTTTCC-3’ and reverse primer D: 5’-GCCTCGAGGTTCTCCCTGCTCTCCTCAG-3’, using templates from the PCR products amplified by primers A and B. The amplified products by nested PCR were subcloned into pCRII vector (Life Technologies). The sequences of PCR products from testis and incisor were analyzed. A novel transcript of Gm1045 (Fig. 1a, lane 3, indicated by an arrow), namely Gm1045-b from testis was The plasmid containing the coding sequence of Gm1045-a (Fig. 1a, lane 8) was also obtained from incisor tissue (pcDNA3-Gm1045-a-HA).

Fig. 1.

Gene expression, amino acid sequences and genomic structure of mouse homologue of C4orf26 (Gm1045-a) and its isoform, Gm1045-b. (a) The expression of Gm1045-a (indicated by an arrowhead) was predominantly detected in tooth samples (upper panel, lanes 8–9), to lesser extent in testis (lane 3) and spleen (lane 7), and that of a splicing variant (Gm1045-b, indicated by an arrow) was only observed in testis (lane 3). The expression of Gapdh was shown as a loading control (lower panel). Skeletal m.; skeletal muscle. The experiments were repeated at least three times and a representative result is shown. (b) The amino acid sequences of Gm1045 isoforms. Comparison of amino acid sequences of Gm1045-a (Gm-a (T)) and Gm1045-b (Gm-b) from testis, Gm1045-a from incisor (Gm-a (I)) and the NCBI reference sequence (NP_001171048, NP) of Gm1045 is shown. The putative signal peptide sequence and cleavage site are outlined with a box. Identical amino acids among isoforms are indicated by asterisk. The amino acid changes in Gm1045-a at residues 98 and 109 are highlighted in bold letters. (c) Genomic structure of mouse Gm1045. Boxes represent exons and lines introns. The coding region of Gm1045 is shown by gray box. The primer binding sites used for molecular cloning in this study are indicated by smaller arrows (A-D). Tel; telomere, Cen; centromere, Ad Exon; additional exon.

Human FAM20C expression vector constructs including wild-type (WT) and a mutant form lacking its kinase activity (D478A, [8]) and human FAM20A WT expression vector were generated by PCR methods as previously described [17] and used in this study.

Immunohistochemistry

To determine the tissue distribution of C4orf26 in vivo, immunohistochemical staining was performed as described [18]. Briefly, formalin fixed decalcified paraffin embedded horizontally-cut sections of wild-type mouse mandible (C57BL/6 strain, 2 months old, male) were deparaffinized, followed by incubation with anti-C4orf26 antibody (diluted in 1:100, ab223071, Abcam) or normal rabbit IgG (negative control) overnight at 4 °C. The immunoreactivity was amplified using VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Rabbit IgG Kit (Vector Laboratories) and visualized by ImmPACT DAB Peroxidase Substrate (Vector Laboratories). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. The immunoreactivities of specimens visualized were photographed under a light microscope. Three independent experiments using three animals were performed and the results were essentially identical.

Phosphorylation of C4orf26/Gm1045 in cell cultures

HAT-7 or HEK293 cells were maintained and plated onto 6 well culture plates at a density of 3 X 105 cells / dish. On the following day, cells were transfected with an empty vector (pcDNA3-HA vector), pcDNA3-C4orf26-HA vector or pcDNA3-Gm1045-HA vector and pcDNA3-FAM20A-WT-Flag, pcDNA3-FAM20C-WT-Flag or -V5/His, or pcDNA3-FAM20C-D478A-V5/His vector using X-tremeGENE9 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 24 hours, conditioned media were collected and cell lysates were prepared as described [18]. The conditioned media and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) followed by Western Blot (WB) analysis with anti-HA (clone 3F10, Roche Applied Science) or anti-V5 antibody (Life Technologies). To remove the phosphate group, the immunoprecipitated protein complex (Fig. 3b and Fig. 3f, lower panel) or the cell (Fig. 3f, upper panel) was incubated with Lambda protein phosphatase (New England Biolabs). The immunoreactivity was visualized using ECL prime (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) as described [16]. At least three independent experiments were performed in each assay and the results were essentially identical.

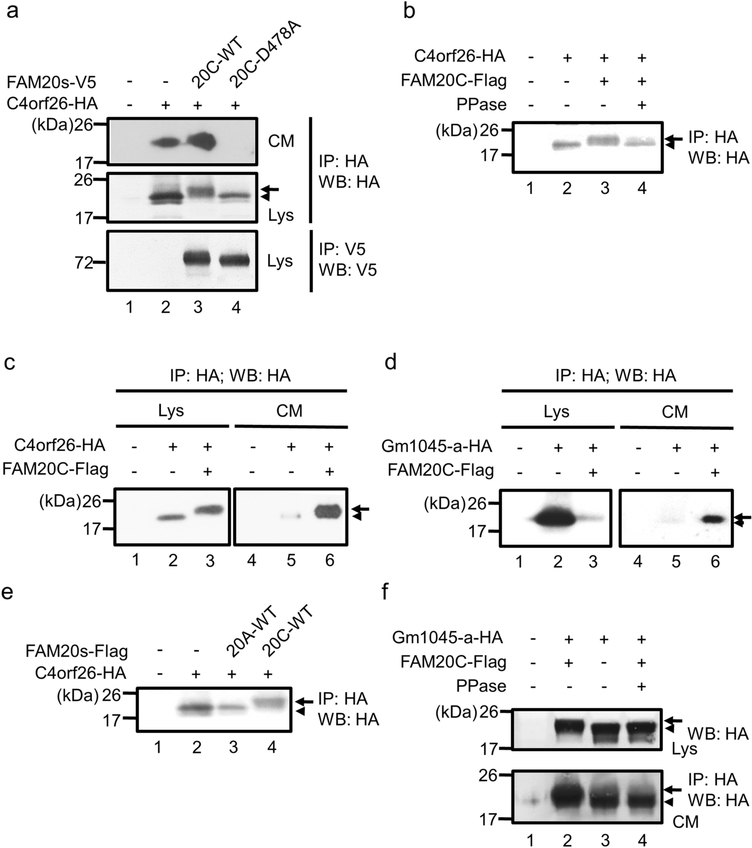

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylation of C4orf26 and Gm1045-a by FAM20C kinase in cell cultures. (a) FAM20C WT or the kinase inactive form, D478A was co-transfected with C4orf26 into HEK293 cells, and the localization and electrophoretic mobility of C4orf26 were assessed by Immunoprecipitation (IP)-Western Blot (WB) analysis. The phosphorylated or non-phosphorylated C4orf26 was indicated by an arrow or an arrowhead, respectively. Lys; Lysates, CM; Conditioned Media. (b) Effect of phosphatase (PPase) treatment was investigated on the electrophoretic mobility of C4orf26 in the lysate fraction of HEK293 cells. Note that the mobility of phosphorylated C4orf26 band (indicated by an arrow, lane 3) was accelerated by PPase treatment (indicated by an arrowhead, lane 4). (c, d) Effect of FAM20C on the localization and electrophoretic mobility of C4orf26 (c) or Gm1045-a (d) were assessed in HAT-7 cells by IP-WB analysis. (e) FAM20C, but not FAM20A phosphorylates C4orf26. HEK 293 cells were transfected with FAM20A or FAM20C together with C4orf26 and phosphorylation of C4orf26 was investigated by FAM20 kinases. (f) Effect of PPase treatment was investigated on the electrophoretic mobility of Gm1045 in the lysate (Lys) and the conditioned media (CM) fractions of HEK293 cells. Note that the mobility of phosphorylated Gm1045 band (indicated by an arrow, lane 2) was accelerated by PPase treatment (indicated by an arrowhead, lane 4).

Results

Expression of Gm1045 in mouse tissues

Recently, C4orf26 became an alternative gene symbol and the gene symbol was replaced with ODAPH (Odontogenesis-associated phosphoprotein) according to Human genome nomenclature data. To avoid any confusion, in this study, we use C4orf26 instead of ODAPH because all previously published works used C4orf26 [7, 19]. To identify mouse homologue of C4orf26 gene, protein sequence of human C4orf26 (isoform 2, GenBank Accession Number: NP_848592) was first obtained as a query sequence and alignment search through mouse BLAST program was then performed. The result showed that Gm1045 (GENE ID: 381651) has the highest similarity in mouse and is 63 % identical to C4orf26. In order to clone the mouse homologue of C4orf26 gene, the expression level of Gm1045 transcript in various mouse tissues was first examined. The nested RT-PCR analysis identified the presence of two Gm1045 transcript variants, i.e. Gm1045-a and Gm1045-b and each transcript was differentially expressed in the tissues examined (Fig. 1a). We found that Gm1045-a is identical to C4orf26 isoform 2. The expression of Gm1045-a (Fig. 1a, indicated by an arrowhead, 397bp) was detected and restricted to teeth (Fig. 1a, lanes 8–9). It was also detected in the spleen (Fig. 1a, lane 7) and to lesser extent in the testis (Fig. 1a, lane 3). We also found that Gm1045-b was only detected in the testis (Fig. 1a, lane 3, indicated by an arrow, 479bp). After determination of Gm1045 cDNA sequences derived from the testis and incisor, the predicted protein sequences of mouse testis-derived Gm1045-a (Gm-a (T)), Gm1045-b (Gm-b) and incisor-derived Gm1045-a (Gm-a (I)) were compared and shown in Fig. 1b. We found the protein sequence of Gm-a (I) was 100% identical to the NCBI reference sequence of Gm1045 (NP_001171048, referred to NP in Fig. 1b). The putative signal peptide sequence and cleavage site were predicted using the PSORT II program and outlined (Fig. 1b, indicated by a box). There were some amino acid changes in Gm-a (T) at residue 98 from Arginine (R) to Glycine (G) and at residue 109 from Isoleucine (I) to Phenylalanine (F). These changes are likely due to single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) because the mouse strain of testis is derived from BALB/c while teeth samples are from C57BL/6, which SNPdb database supports. Fig. 1c illustrates genomic structure of mouse Gm1045 gene. According to the NCBI genomic information under GENE ID: 381651, there are two exons (Exon1 and 2) in Gm1045-a, and we identified a novel additional exon (Ad exon) between Exon 1 and 2. Since this additional exon has a stop codon in frame, a novel splicing isoform, Gm1045-b encodes only 27 amino acids in length (Fig. 1b). Based on the predicted signal peptide cleavage site, it is unlikely that the mature portion of Gm1045-b protein has similar functionality to C4orf26/Gm1045-a, thus our study further focuses on Gm1045-a and C4orf26.

Localization of Gm1045 protein in developing mouse tooth

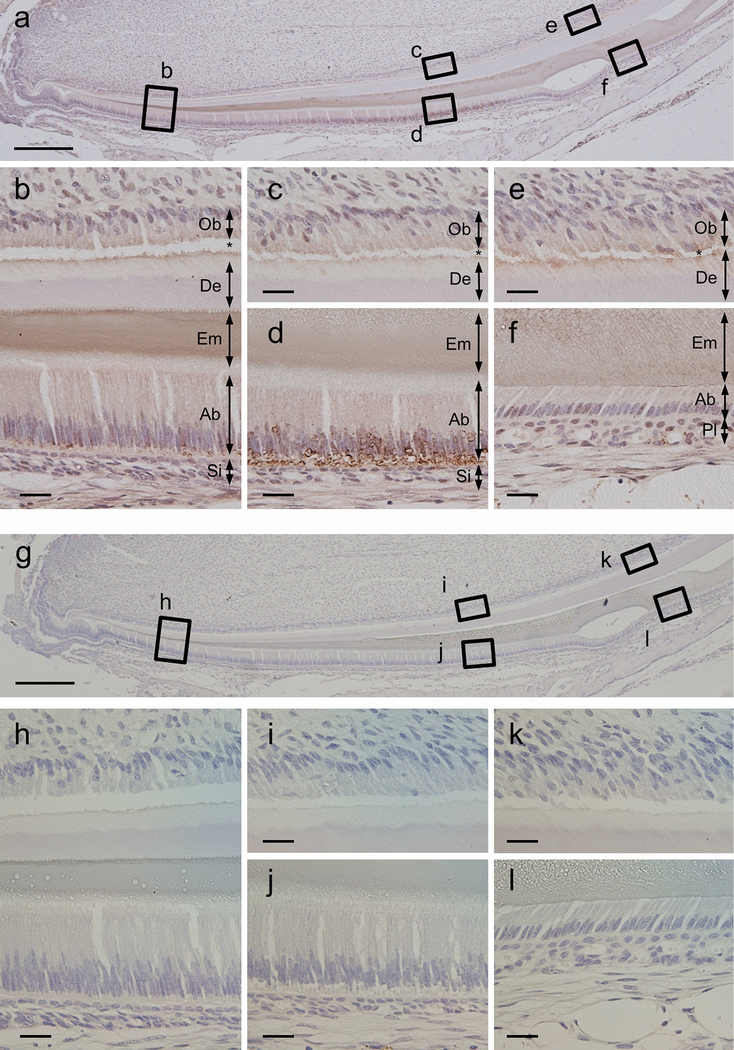

The localization of Gm1045 in the mandibular incisor was shown in Fig. 2. At the initial secretory stage of amelogenesis, the immunoreactivity to anti-C4orf26 antibody was strongly observed in the enamel matrix (Fig. 2b, Em) and, to a lesser extent, in the cytoplasmic region of secretory ameloblasts (Fig. 2b, Ab). At the transition~maturation stage of amelogenesis, the immunoreactivity in the enamel matrix was slightly decreased (Fig. 2d, Em), while the transiently enhanced signal was detected around the distal region of ameloblasts (Fig. 2d, Ab). At the maturation stage of amelogenesis, the immunoreactivity in the enamel matrix was still observed (Fig. 2f, Em), however, that in maturation ameloblasts was gradually decreased (Fig. 2f, Ab). The immunoreactivity was also observed at the apical region of odontoblasts/pre-dentin area (Figs. 2b, c & e, Ob and De). Normal rabbit immunoglobulin was used as a negative control and no immunoreactivities were observed (Figs. 2g–l). Our results strongly suggest that Gm1045 is an extracellular matrix protein in enamel.

Fig. 2.

Presence of Gm1045 protein at secretory and maturation stages of amelogenesis. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using mouse mandibular incisor sections. Gm1045 protein was clearly present in the enamel matrices (Em) as well as in the cytoplasmic areas of ameloblasts (Ab) at secretory (b), transition (d) and maturation (f) stages. Normal rabbit immunogloblin was used for a negative control as shown in (g-l). Note that asterisk indicates an artifact. Ob; odontoblast, De; dentin, Em; enamel, Ab; ameloblast, Si; stratum intermedium, Pl; papillary layer. Scale bar: (a, g) 200μm, (b-f, h-l)20μm.

Phosphorylation of C4orf26/Gm1045 by FAM20C

Since C4orf26 is predicted to be an acidic phosphoprotein [7] and has S-X-E motifs at its C-terminus, the effect of FAM20C kinase on C4orf26 and Gm1045 phosphorylation was investigated. Wild-type (WT) FAM20C or the kinase-inactive FAM20C D478A was co-transfected with C4orf26 into HEK293 cells, and localization and electrophoretic mobility of C4orf26 was investigated by IP-WB analysis (Fig. 3a). When C4orf26 alone was overexpressed, it was detected both in the medium (Fig. 3a, upper panel, lane 2) and cell lysate (Fig. 3a, middle panel, lane 2). When WT FAM20C was co-transfected with C4orf26, the electrophoretic mobility of C4orf26 was delayed (Fig. 3a, middle panel, lane 3) and the amount of secreted C4orf26 appeared to be increased (Fig. 3a, upper panel, lane 3). The treatment of cell lysates with protein phosphatase in vitro resulted in the acceleration of the mobility (Fig. 3b, lanes 3 vs 4), confirming the delayed electrophoretic mobility is due to phosphorylation. When Gm1045 was overexpressed together with FAM20C, the electrophoretic mobility of Gm1045 was delayed as compared to that of Gm1045 alone in both cell lysates and conditioned media (Fig. 3f, upper and lower panels, lane 2 vs lane 3). Upon the protein phosphatase treatment in vitro, the electrophoretic mobility of Gm1045 was accelerated (Fig. 3f, upper and lower panels, lane 2 vs lane 4), confirming that the delayed electrophoretic mobility of Gm1045 with FAM20C co-expression was due to phosphorylation. The kinase inactive FAM20C failed to phosphorylate C4orf26 (Fig. 3a, middle panel, lane 4), and more interestingly, this inactive form prevented C4orf26 from its secretion (Fig. 3a, upper panel, lane 4), indicating FAM20C kinase activity is essential for C4orf26 secretion.

We next investigated whether the phosphorylation of C4orf26/Gm1045 by FAM20C occurs in the ameloblastic cell line, HAT-7 cells (Figs. 3c & 3d). WT FAM20C was co-transfected with C4orf26 (Fig. 3c) or Gm1045-a (Fig. 3d), and localization and electrophoretic mobility were accessed. The results demonstrated that phosphorylation of C4orf26 also occurred in HAT-7 ameloblastic cells (Fig. 3c, lane 3) and the secretion of C4orf26/Gm1045-a was enhanced in the presence of FAM20C (Figs. 3c & 3d, lane 6). FAM20C is a member of three related “family with sequence similarity 20” proteins, i.e. FAM20A, FAM20B and FAM20C [20] and non-sense mutations in FAM20A gene were recently identified that caused autosomal recessive type of AI [21, 22]. To investigate whether the phosphorylation of C4orf26 occurs in the presence of FAM20A, C4orf26 was co-transfected with either FAM20A or FAM20C and the electrophoretic mobility was investigated. As shown in Fig. 3e, the migration of C4orf26 was not affected by FAM20A (Fig. 3e, lane 3), demonstrating the specificity of C4orf26 phosphorylation by FAM20C (Fig. 3e, lane 4).

Discussion

It has been known for almost 30 years that most enamel proteins are phosphoproteins containing O-phosphoserine [23] and phosphorylation may allow these enamel proteins to associate with calcium ions, initiate, and control the orientation, direction and magnitude of crystal growth during the initial steps of biomineralization [24–26]. Numerous extracellular enamel matrix proteins are produced by ameloblasts and there are multiple extracellular proteins associated with AI including amelogenin (AMELX gene product), enamelin (ENAM gene product), ameloblastin (AMBN gene product), MMP20 and KLK4.

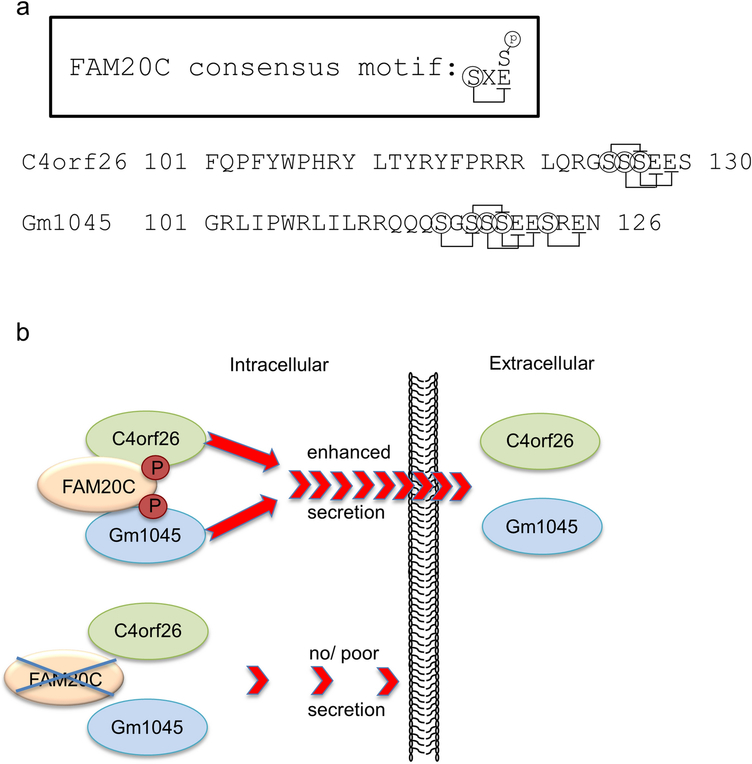

The predominant matrix protein in secretory enamel is amelogenin. It has been well known that amelogenin at Ser32 (within S32-Y-E sequence, pro-protein numbering in human) is phosphorylated [27]. Unerupted tooth-derived, microsomal fraction-rich “enamel specific protein kinases” play an important role in in vitro phosphorylation of Ser16 in mature amelogenin form (identical to Ser32 in full length form) [28]. The biological importance of this phosphorylation site in amelogenin has been extensively studied [29–32]. A single phosphate group on serine at residue 16 of amelogenin has been shown to be responsible for regulating mineralization during enamel formation by preventing unwanted mineral formation within enamel matrix and stabilization of amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) during the secretory stage of amelogenesis [29]. This notion is further supported by a recent report that knock-in mice with S16 replaced with alanine exhibited faster ACP-to-apatitic crystal transformation, resulting in decreased enamel crystal elongation [33]. Therefore, this single phosphorylated serine residue likely affects amelogenin conformation and protein-mineral interactions during stages of amelogenesis [30]. Another enamel specific matrix protein, enamelin is known to be phosphorylated at Ser191 and Ser216 (within S191-N-E and S216-E-E sequences in porcine [34] and these sequences are 100% conserved to those in human). Moreover, a mutation in one of these sites (p.S216L) causes AI in humans [35]. The N-terminal region of porcine ameloblastin is shown to contain phosphorylated serine residue at position 17 [36] (within S17-L-E sequence in porcine, identical to Ser43 in full length form). This particular FAM20C phosphorylation motif is 100% conserved to that in human (S43-L-E) and mouse (S48-L-E). Although ameloblastin is associated with one of hypoplastic type of AIs [37, 38], these reports did not show any particular mutations in serine residues, rather deletion of exon 6 or splice site mutations, in human. Previously, the transgenic mice were generated overexpressing mutated ameloblastin where predicted FAM20C serine phosphorylation sites (at Ser48, Ser226 and Ser227) were all replaced with either alanine (thus, serine phosphorylation is defective) or aspartic acid (thus, serine phosphorylation is mimicked), showing defective enamel in both mutant animals [39]. This study suggested the importance of serine phosphorylation in these FAM20C phosphorylation sites, although there have been no reports that the Ser226 and Ser227 are physiologically phosphorylated. At this point, it remains unclear whether MMP20 and KLK4 are indeed phosphorylated. Lastly, mutations in C4orf26 gene were found in recessive type of AI, while the synthetic phospho-peptide based on human C4orf26 (CFQPFYWPHRYL-pT-YRYFPRRRLQRG-pS-pS-pS-EES) promotes the nucleation and growth on hydroxyapatite crystals [7]. There are three FAM20C phosphorylation consensus motifs in human C4orf26 protein, while five motifs in mouse Gm1045 protein (Fig. 4a). The serine residues in the synthetic-peptide are well conserved to the mouse Gm1045-a (Figs. 1b & 4a). However, the effect and its biological importance of threonine phosphorylation in the peptide still remain unclear.

Fig. 4.

FAM20C phosphorylation motifs in C4orf26/Gm1045 and schematic representation of C4orf26/Gm1045 secretion. (a) FAM20C phosphorylation consensus S-X-E/pS motif is shown in the upper box. The protein sequences of human C4orf26 (residues 101–130) and of mouse Gm1045 (residues 101–126) are shown with S-X-E/pS motifs. (b) C4orf26/Gm1045 phosphorylation by FAM20C results in the enhanced secretion, while in the absence of FAM20C kinase activity, the secretion of C4orf26/Gm1045 becomes poor, potentially leading to abnormal enamel formation/Amelogenesis Imperfecta.

There have been a number of previous reports that Parotid Gland Kinase (PGK) [40], Sublingual Gland Kinase (SGK) [41, 42] and Golgi Casein Kinase (GCK) are present. The preferred phosphorylation sites for these kinases are somewhat similar, i.e. S-X-E and D-S-E-Q-F for PGK, S-X-E for SGK and S-X-E/pS and D-S-E-Q-F for GCK [40], indicating that more than one type of protein kinases are redundantly present, responsible for phosphorylating secretory phosphoproteins. Recent reports also support this notion that all S-X-E phosphorylation sites were phosphorylated by FAM20C [8, 43].

We propose a model that C4orf26 was phosphorylated by FAM20C wild-type and secreted into the medium while non-phosphorylated C4orf26 by kinase inactive FAM20C D478A mutant failed to secrete (Fig. 4b), suggesting the importance of this phosphorylation-dependent secretion. When C4orf26 or Gm1045 alone was transfected in HAT-7 cells, these proteins remained in the cell lysate fraction and barely detected in the conditioned media (Fig. 3c, lanes 2 and 5 & Fig. 3d, lanes 2 and 5), while when C4orf26 or Gm1045 was co-transfected with FAM20C, C4orf26 or Gm1045 was readily detected in the conditioned media (Fig. 3c, lane 6 & Fig. 3d, lane 6). In HEK293 cells, when C4orf26 alone was transfected, C4orf26 in the conditioned media was readily detected (Fig. 3a, lane 2), and the amount of secreted C4orf26 co-transfected with FAM20C appeared greater than that of C4orf26 alone (Fig. 3a, upper panel, lane 2 vs lane 3). This might be due to a different amount of endogenous FAM20C expression present between HEK293 and HAT-7 cells, presumably the amount of endogenous FAM20C in HEK293 cells may be more than that of HAT-7 cells. To support this notion, we previously reported the expression patterns of FAM 20 family members and the FAM20C gene expression level in the kidney was the same as that of the tooth [17]. It is also interesting to note that patients with C4orf26 mutations show not only a maturation stage enamel defect, i.e. soft enamel, but also a secretory stage defect, i.e. thin enamel [7]. This enamel phenotype is consistent with our immunohistochemical data (Fig. 2) showing its secretory stage expression.

In summary, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to show that FAM20C is at least one of the enamel kinases that phosphorylate C4orf26 and Gm1045, newly identified enamel matrix protein. The outcomes from this research may further have a broad impact on mineralized tissue regeneration strategy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hidemitsu Harada (Iwate Medical University, Japan) for providing HAT-7 cells. We also thank for Dr. Sundharamani Venkitapathi for his assistance. This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, NIH (DE019527 to YM.) and Boston University Henry Goldman School of Dental Medicine (YM.). NG and PP were supported by The Chulalongkorn Academic Advancement Into Its 2nd Century Project.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Accession Number

The nucleotide sequences for mouse Gm1045-a and Gm1045-b genes have been deposited in the GenBank database under GenBank Accession numbers; KF477194 and KC602377, respectively.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Collier PM, Sauk JJ, Rosenbloom SJ, Yuan ZA, Gibson CW (1997) An amelogenin gene defect associated with human X-linked amelogenesis imperfecta. Arch Oral Biol 42:235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart TC, Hart PS, Gorry MC, Michalec MD, Ryu OH, Uygur C, Ozdemir D, Firatli S, Aren G, Firatli E (2003) Novel ENAM mutation responsible for autosomal recessive amelogenesis imperfecta and localised enamel defects. J Med Genet 40:900–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kida M, Ariga T, Shirakawa T, Oguchi H, Sakiyama Y (2002) Autosomal-dominant hypoplastic form of amelogenesis imperfecta caused by an enamelin gene mutation at the exon-intron boundary. J Dent Res 81:738–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravassipour DB, Hart PS, Hart TC, Ritter AV, Yamauchi M, Gibson C, Wright JT (2000) Unique enamel phenotype associated with amelogenin gene (AMELX) codon 41 point mutation. J Dent Res 79:1476–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hart PS, Hart TC, Simmer JP, Wright JT (2002) A nomenclature for X-linked amelogenesis imperfecta. Arch Oral Biol 47:255–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajpar MH, Harley K, Laing C, Davies RM, Dixon MJ (2001) Mutation of the gene encoding the enamel-specific protein, enamelin, causes autosomal-dominant amelogenesis imperfecta. Hum Mol Genet 10:1673–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parry DA, Brookes SJ, Logan CV, Poulter JA, El-Sayed W, Al-Bahlani S, Al Harasi S, Sayed J, Raif el M, Shore RC, Dashash M, Barron M, Morgan JE, Carr IM, Taylor GR, Johnson CA, Aldred MJ, Dixon MJ, Wright JT, Kirkham J, Inglehearn CF, Mighell AJ (2012) Mutations in C4orf26, encoding a peptide with in vitro hydroxyapatite crystal nucleation and growth activity, cause amelogenesis imperfecta. Am J Hum Genet 91:565–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tagliabracci VS, Engel JL, Wen J, Wiley SE, Worby CA, Kinch LN, Xiao J, Grishin NV, Dixon JE (2012) Secreted kinase phosphorylates extracellular proteins that regulate biomineralization. Science 336:1150–1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raine J, Winter RM, Davey A, Tucker SM (1989) Unknown Syndrome - Microcephaly, Hypoplastic Nose, Exophthalmos, Gum Hyperplasia, Cleft-Palate, Low Set Ears, and Osteosclerosis. Journal of Medical Genetics 26:786–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kingston HM, Freeman JS, Hall CM (1991) A New Lethal Sclerosing Bone Dysplasia. Skeletal Radiology 20:117–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kan AE, Kozlowski K (1992) New Distinct Lethal Osteosclerotic Bone Dysplasia (Raine Syndrome). American Journal of Medical Genetics 43:860–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acevedo AC, Poulter JA, Alves PG, de Lima CL, Castro LC, Yamaguti PM, Paula LM, Parry DA, Logan CV, Smith CEL, Johnson CA, Inglehearn CF, Mighell AJ (2015) Variability of systemic and oro-dental phenotype in two families with non-lethal Raine syndrome with FAM20C mutations. Bmc Med Genet 16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elalaoui SC, Al-Sheqaih N, Ratbi I, Urquhart JE, O'Sullivan J, Bhaskar S, Williams SS, Elalloussi M, Lyahyai J, Sbihi L, Jaouad IC, Sbihi A, Newman WG, Sefiani A (2016) Non lethal Raine syndrome and differential diagnosis. Eur J Med Genet 59:577–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tagliabracci VS, Wiley SE, Guo X, Kinch LN, Durrant E, Wen J, Xiao J, Cui J, Nguyen KB, Engel JL, Coon JJ, Grishin N, Pinna LA, Pagliarini DJ, Dixon JE (2015) A Single Kinase Generates the Majority of the Secreted Phosphoproteome. Cell 161:1619–1632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawano S, Morotomi T, Toyono T, Nakamura N, Uchida T, Ohishi M, Toyoshima K, Harada H (2002) Establishment of dental epithelial cell line (HAT-7) and the cell differentiation dependent on Notch signaling pathway. Connect Tissue Res 43:409–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mochida Y, Takeda K, Saitoh M, Nishitoh H, Amagasa T, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Ichijo H (2000) ASK1 inhibits interleukin-1-induced NF-kappa B activity through disruption of TRAF6-TAK1 interaction. J Biol Chem 275:32747–32752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohyama Y, Lin JH, Govitvattana N, Lin IP, Venkitapathi S, Alamoudi A, Husein D, An C, Hotta H, Kaku M, Mochida Y (2016) FAM20A binds to and regulates FAM20C localization. Sci Rep 6:27784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mochida Y, Kaku M, Yoshida K, Katafuchi M, Atsawasuwan P, Yamauchi M (2011) Podocan-like protein: a novel small leucine-rich repeat matrix protein in bone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 410:333–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad MK, Laouina S, El Alloussi M, Dollfus H, Bloch-Zupan A (2016) Amelogenesis Imperfecta: 1 Family, 2 Phenotypes, and 2 Mutated Genes. J Dent Res 95:1457–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nalbant D, Youn H, Nalbant SI, Sharma S, Cobos E, Beale EG, Du Y, Williams SC (2005) FAM20: an evolutionarily conserved family of secreted proteins expressed in hematopoietic cells. BMC Genomics 6:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Sullivan J, Bitu CC, Daly SB, Urquhart JE, Barron MJ, Bhaskar SS, Martelli-Junior H, dos Santos Neto PE, Mansilla MA, Murray JC, Coletta RD, Black GC, Dixon MJ (2011) Whole-Exome identifies FAM20A mutations as a cause of amelogenesis imperfecta and gingival hyperplasia syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 88:616–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho SH, Seymen F, Lee KE, Lee SK, Kweon YS, Kim KJ, Jung SE, Song SJ, Yildirim M, Bayram M, Tuna EB, Gencay K, Kim JW (2012) Novel FAM20A mutations in hypoplastic amelogenesis imperfecta. Hum Mutat 33:91–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strawich E, Glimcher MJ (1985) Synthesis and degradation in vivo of a phosphoprotein from rat dental enamel. Identification of a phosphorylated precursor protein in the extracellular organic matrix. Biochem J 230:423–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Termine JD, Torchia DA, Conn KM (1979) Enamel matrix: structural proteins. J Dent Res 58:773–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fincham AG, Belcourt AB, Termine JD (1982) Changing patterns of enamel matrix proteins in the developing bovine tooth. Caries Res 16:64–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fincham AG, Hu Y, Lau EC, Slavkin HC, Snead ML (1991) Amelogenin post-secretory processing during biomineralization in the postnatal mouse molar tooth. Arch Oral Biol 36:305–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fincham AG, Moradian-Oldak J, Sarte PE (1994) Mass-spectrographic analysis of a porcine amelogenin identifies a single phosphorylated locus. Calcif Tissue Int 55:398–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salih E, Huang JC, Strawich E, Gouverneur M, Glimcher MJ (1998) Enamel specific protein kinases and state of phosphorylation of purified amelogenins. Connect Tissue Res 38:225–235; discussion 241–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwak SY, Wiedemann-Bidlack FB, Beniash E, Yamakoshi Y, Simmer JP, Litman A, Margolis HC (2009) Role of 20-kDa amelogenin (P148) phosphorylation in calcium phosphate formation in vitro. J Biol Chem 284:18972–18979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Norcy E, Kwak SY, Allaire M, Fratzl P, Yamakoshi Y, Simmer JP, Margolis HC (2011) Effect of phosphorylation on the interaction of calcium with leucine-rich amelogenin peptide. Eur J Oral Sci 119 Suppl 1:97–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masica DL, Gray JJ, Shaw WJ (2011) Partial high-resolution structure of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated leucine-rich amelogenin protein adsorbed to hydroxyapatite. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces 115:13775–13785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiedemann-Bidlack FB, Kwak SY, Beniash E, Yamakoshi Y, Simmer JP, Margolis HC (2011) Effects of phosphorylation on the self-assembly of native full-length porcine amelogenin and its regulation of calcium phosphate formation in vitro. J Struct Biol 173:250–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin NY, Yamazaki H, Beniash E, Yang X, Margolis SS, Pugach MK, Simmer JP, Margolis HC (2020) Amelogenin phosphorylation regulates tooth enamel formation by stabilizing a transient amorphous mineral precursor. J Biol Chem 295:1943–1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukae M, Tanabe T, Murakami C, Dohi N, Uchida T, Shimizu M (1996) Primary structure of the porcine 89-kDa enamelin. Adv Dent Res 10:111–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan HC, Mai L, Oikonomopoulou A, Chan HL, Richardson AS, Wang SK, Simmer JP, Hu JC (2010) Altered enamelin phosphorylation site causes amelogenesis imperfecta. J Dent Res 89:695–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi K, Yamakoshi Y, Hu JC, Gomi K, Arai T, Fukae M, Krebsbach PH, Simmer JP (2007) Splicing determines the glycosylation state of ameloblastin. J Dent Res 86:962–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poulter JA, Murillo G, Brookes SJ, Smith CE, Parry DA, Silva S, Kirkham J, Inglehearn CF, Mighell AJ (2014) Deletion of ameloblastin exon 6 is associated with amelogenesis imperfecta. Hum Mol Genet 23:5317–5324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasad MK, Geoffroy V, Vicaire S, Jost B, Dumas M, Le Gras S, Switala M, Gasse B, Laugel-Haushalter V, Paschaki M, Leheup B, Droz D, Dalstein A, Loing A, Grollemund B, Muller-Bolla M, Lopez-Cazaux S, Minoux M, Jung S, Obry F, Vogt V, Davideau JL, Davit-Beal T, Kaiser AS, Moog U, Richard B, Morrier JJ, Duprez JP, Odent S, Bailleul-Forestier I, Rousset MM, Merametdijan L, Toutain A, Joseph C, Giuliano F, Dahlet JC, Courval A, El Alloussi M, Laouina S, Soskin S, Guffon N, Dieux A, Doray B, Feierabend S, Ginglinger E, Fournier B, de la Dure Molla M, Alembik Y, Tardieu C, Clauss F, Berdal A, Stoetzel C, Maniere MC, Dollfus H, Bloch-Zupan A (2016) A targeted next-generation sequencing assay for the molecular diagnosis of genetic disorders with orodental involvement. J Med Genet 53:98–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma P, Yan W, Tian Y, He J, Brookes SJ, Wang X (2016) The Importance of Serine Phosphorylation of Ameloblastin on Enamel Formation. J Dent Res 95:1408–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamkin MS, Lindhe P (2001) Purification of kinase activity from primate parotid glands. J Dent Res 80:1890–1894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nam Y, Madapallimattam G, Drzymala L, Bennick A (1997) Characterization of human sublingual-gland protein kinase by phosphorylation of a peptide related to secreted proteins. Arch Oral Biol 42:527–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madapallimattam G, Bennick A (1986) Phosphorylation of salivary proteins by salivary gland protein kinase. J Dent Res 65:405–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang X, Yan W, Tian Y, Ma P, Opperman LA, Wang X (2016) Family with sequence similarity member 20C is the primary but not the only kinase for the small-integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins in bone. FASEB J 30:121–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]