Abstract

Background:

Black and Hispanic children growing up in disadvantaged urban neighborhoods have the highest rates of asthma and related morbidity in the United States.

Objective:

To identify specific respiratory phenotypes of health and disease in this population, associations with early-life exposures, and molecular patterns of gene expression in nasal epithelial cells that underlie clinical disease.

Methods:

The study population consisted of 442 high-risk urban children who had repeated assessments of wheezing, allergen-specific IgE, and lung function through age 10 years. Phenotypes were identified by developing temporal trajectories for these data, and then compared to early life exposures and patterns of nasal epithelial gene expression at age 11.

Results:

Of the 6 identified respiratory phenotypes, a high-wheeze high-atopy low-lung-function (HW-HA-LF) group had the greatest respiratory morbidity. In early life, this group had low exposure to common allergens and high exposure to ergosterol in house dust. While all high atopy groups were associated with increased expression of a type-2 inflammation gene module in nasal epithelial samples, an epithelium IL-13 response module tracked closely with impaired lung function, and a MUC5AC hypersecretion module was uniquely upregulated in HW-HA-LF. In contrast, a medium-wheeze low-atopy (MW-LA) group showed altered expression of modules of epithelial integrity, epithelial injury, and antioxidant pathways.

Conclusion:

In the first decade of life, high-risk urban children develop distinct phenotypes of respiratory health versus disease that link early-life environmental exposures to childhood allergic sensitization and asthma. Moreover, unique patterns of airway gene expression demonstrate how specific molecular pathways underlie distinct respiratory phenotypes, including allergic and non-allergic asthma.

Capsule summary:

We have demonstrated both distinct respiratory phenotypes – which develop by age 10 and link to asthma development – and related functional gene expression networks in respiratory epithelium.

Keywords: childhood asthma, endotypes, phenotypes, environmental exposures, transcriptomics

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Asthma affects approximately one in ten children1 and the prevalence of asthma has dramatically increased within a generation, strongly implicating lifestyle and/or environmental causes.2 While medications and environmental and lifestyle modifications can help to control asthma, a cure for asthma remains elusive. Several birth cohorts have identified different phenotypes of childhood asthma,3–6 but incomplete understanding of the molecular mechanisms underpinning these phenotypes and corresponding risk factors has hampered efforts towards asthma prevention.

Wheezing phenotypes were originally described in the Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study based on the timing of onset and course of symptoms, and the overall patterns of transient, persistent and late-onset wheeze have been confirmed and expanded upon in other populations.3, 7–12 One phenotype of particular interest consists of children who develop sensitization to multiple aeroallergens in early life, and then develop recurrent wheezing episodes that are initially triggered by respiratory illnesses (often caused by rhinoviruses [RV] 13, 14) and later become multifactorial in origin (e.g. exercise, allergen exposure).15 Children with this pattern of persistent wheeze tend to develop airway obstruction and hyperresponsiveness16,17 and experience greater respiratory morbidity 8, 15, 17, 18 compared to other children.

The close relationships between allergic sensitization, type-2 inflammation and viral wheezing illnesses in early life with the development of asthma suggest that skewed immune development influences the development of asthma phenotypes. Studies of blood responses beginning at birth suggest that delayed development of interferon responses and/or perhaps tolerance mechanisms predispose to viral wheeze and allergic sensitization,19–21 and that elevation of type-2 cytokines associate with asthma development,21, 22 but these signals are heterogeneous and do not fully explain distinct asthma phenotypes. Measures of immune development in the airway mucosa rather than peripheral blood may be more closely related to pathogenic mechanisms of childhood asthma, and several studies support the finding that upper airway responses can reflect host-environment interactions that are relevant to lower airways.23–26

Urban children who grow up in neighborhoods with high rates of poverty have some of the highest rates of wheezing illnesses and asthma, and also have greater morbidity associated with asthma.1, 27 We recently identified different phenotypes of wheezing, atopy and respiratory health in 7-year-old children participating in the Urban Environment and Childhood Asthma (URECA) birth cohort study.5 For the current analysis, we have extended the phenotype definitions to include wheeze, allergen-specific IgE and lung function data obtained from birth until 10 years of age. We then tested the hypothesis that early life exposures would be differentially related to the respiratory phenotypes. Critically, we then analyzed whether these phenotypes were associated with distinct patterns of gene expression in nasal epithelial cells obtained at age 11 years of age to define molecular endotypes of respiratory allergy and childhood asthma.

Methods

Study recruitment and eligibility.

The URECA birth cohort study started enrollment in 2005 in urban neighborhoods with high rates (>20%) of poverty in Baltimore, Boston, New York City, and St. Louis.28 Pregnant women, whose children were at high risk for developing asthma due to a history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, or eczema in the mother or father, were recruited prenatally. Written informed consent was obtained from the families, and assent was obtained for children ages 7 years and older.

Data collection.

Maternal questionnaires were administered prenatally, and postnatal child health questionnaires were administered every three months through age 10 years. Annual visits included questionnaires, anthropomorphic measurements, pulmonary function testing, and phlebotomy. Allergen-specific IgE levels (ImmunoCAP, Phadia, Uppsala Sweden) for selected aeroallergens were measured at ages 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 and 10 years, and skin prick testing was performed at 3, 5, 7 and 10 years of age for 14 common aeroallergens as previously described.28 Starting at age 3 years, spirometry and impulse oscillometry (IOS) were performed annually in accordance with ATS guidelines.29 At ages ≥ 6 years, reversibility was measured 15 minutes after inhaled albuterol. Methacholine challenge was performed at age 7 and 10 years as previously described.30

Cotinine levels were measured in cord blood plasma as previously described.28 Home dust samples obtained during the first, second, and third years of life were assayed for allergenic proteins, including Bla g 1 (German cockroach), Can f 1 (dog), Fel d 1 (cat), Der f 1 and Der p 1 (house dust mites), and Mus m 1 (mouse) by ELISA (Indoor Biotechnologies, Charlottesville, VA).5 An allergen exposure index (which summed house dust content of cockroach, mouse, and cat proteins) was calculated across the first three years.31 House dust samples obtained during the first year of life were profiled for bacterial microbiota using 16S rRNA biomarker sequencing, and diversity indices were calculated as previously described.31

Nasal brushing.

Nasal cells (ciliated epithelial cells 95 ± 5%, nonciliated epithelial cells 1 ± 2%, leukocytes 4 ± 4%) were obtained at the 11-year visit by brushing the anterior turbinate with a cytology brush (Cyto-Soft Cytology Brush CYB-1, #S7766-1A; Cardinal Health, Dublin, Ohio).24 RNA was extracted and sequenced to analyze gene expression (see Online Supplement).

Asthma Definition.

We classified children as having asthma at age 7 and 10 years according to a definition that considered symptoms, diagnosis by a health care provider, and measurements of pulmonary function as follows: 1) parent-reported physician diagnosis of asthma between age 4 and 7 years, combined with asthma symptoms or the use of asthma controller medication for 6 of the past 12 months; 2) methacholine PC20 ≤ 4 mg/ml or albuterol reversibility of FEV1 ≥ 10%, combined with asthma symptoms or use of asthma controller medication for 6 of the past 12 months; or 3) the report in the past 12 months of ≥2 wheezing episodes, ≥2 doctor visits for asthma/wheeze, ≥1 hospitalization for asthma/wheeze, or the use of controller medications for 6 of the past 12 months.30

Phenotype identification.

URECA children were classified into one of six respiratory health phenotypes. These phenotypes were identified by evaluating longitudinal data sets containing information about wheezing illnesses (any wheeze and number of wheezing illnesses), sensitization to aeroallergens (skin prick tests and allergen-specific IgE), and lung function (FEV1/FVC and XA). These trajectory variables were included in a Gower’s Distance Matrix as previously described.5

Statistical analysis.

Overall differences in clinical and exposure variables among the phenotypes were tested using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the F-test for continuous variables no multiple-comparisons adjustments were made. Similarly, post-hoc pairwise comparisons among the 6 endotypes did not adjust for multiple comparisons given the exploratory nature of the hypotheses. Gene expression data were co-associated into modules using weighted gene correlation network analysis (WGCNA) 32 and differences in module expression among the 6 respiratory phenotype groups was assessed by ANOVA and post-hoc 2-group comparisons using a weighted linear model appropriate for RNA-sequencing data (limma) with multiple testing correction using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.33 Module expression values were similarly compared to FEV1 % predicted and PC20 values collected at age 10. Additional details of the analysis are provided in the Online Supplement.

Results

Study population.

The URECA cohort consists of urban children who are predominantly minorities (72% black, 20% Hispanic [primarily Dominican]) with high rates of poverty (Supplemental Table 1). The overall prevalence of asthma in the population was 29.7% (124/418) at age 10 years, and was significantly related to a history of maternal asthma and response to bronchodilator. The prebronchodilator FEV1 and methacholine PC20 were both slightly lower in children with asthma compared to those without asthma, although these differences were marginally significant.

Distinct respiratory phenotypes differ in atopic status, asthma prevalence, and pulmonary function.

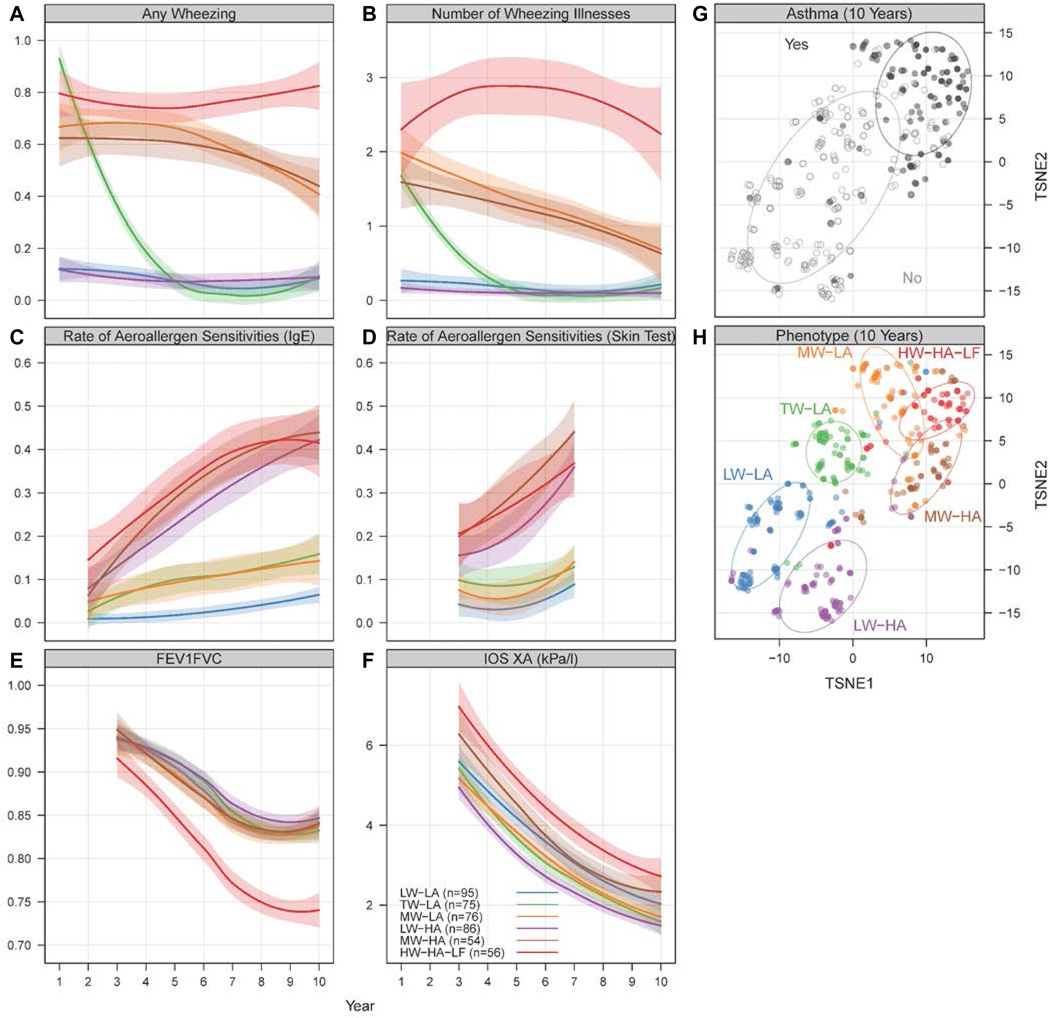

Using longitudinal data sets for wheezing, allergic sensitization, and lung function testing, we identified six distinct phenotypes of respiratory health or disease (Figure 1A-F and Supplemental Table 2). Three phenotypes were notable for little or no atopy and differed by patterns of wheeze. The largest group had minimal wheeze (low wheeze-low atopy [LW-LA], n=95). The second group had wheezing during early life that generally had resolved by 3 to 4 years of age (transient wheeze-low atopy [TW-LA], n=75). The third low atopy group had high rates of wheezing during infancy that steadily diminished through age 10 years (moderate wheeze-low atopy [MW-LA], n=54). Three additional phenotypes had significant atopy and were distinguished by different patterns of wheezing and lung function. This included a group with little or no wheezing (low wheeze-high atopy [LW-HA], n=86) and a group with high rates of wheezing during infancy that steadily diminished with time (moderate wheeze-high atopy [MW-HA], n=76). The sixth and most severe disease group had high rates of allergic sensitization, high rates of wheezing that persisted through age 10, and evidence of airway obstruction and small airway dysfunction on lung function testing (high wheeze-high atopy-low lung function [HW-HA-LF], n=56).

Figure 1.

Respiratory phenotypes in URECA. (A-F) Observed trajectories for variables used in clustering algorithm among URECA participants through age 10 years. Latent class mixed models were performed, and the optimal number of classes selected is plotted. Each model is constructed separately for each variable; thus, the classes are unrelated between variables. Longitudinal data for each of the groups are represented by the colored lines (shading indicated SEs). (G,H) The two-dimensional distance matrix used in the construction of childhood URECA phenotypes by asthma and cluster group is described by using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (TSNE), a dimension-reduction technique for high-dimensional data. Each point represents a study subject, and colors in (H) indicate phenotype assignments.

Host and early-life environmental factors associate with respiratory phenotypes.

Maternal diagnosis of asthma (ever) was most frequent in the MW-HA group, and least frequent in the LW-HA group (Table I). The MW-HA group also had the highest frequency of eczema in early life. Birth weight and gestational age were lowest in the HW-HA-LF and MW-LA groups, though this may not be a biologically relevant finding. Chronic nasal symptoms and hay fever were assessed at age 10 years, and were most common in the MW-HA (58%, 66%) and HW-HA-LF groups (48.8%, 32.6%) respectively. The prevalence of asthma at age 10 was highest in the HW-HA-LF group (81.5%) followed by the MW-LA (54.3%) and MW-HA (48.1%) groups. The HW-HA-LF group also had the lowest PC20, highest bronchodilator reversibility, and greatest use of inhaled and oral corticosteroids between ages 9 and 10 years (Figure 1G-H and Table I).

Table I.

Study population and environmental exposures in early life according to respiratory phenotypes *

| All N =442 | LW-LA N=95 | TW-LA N=75 | MW-LA N=76 | LW-HA N=86 | MW-HA N=54 | HW-HA-LF N=56 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Mother and Family | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Mother married (at entry) | 60 (13.6%) | 15 (16.0%) | 10 (13.3%) | 8 (10.5%) | 9 (10.5%) | 11 (20.4%) | 7 (12.5%) | 0.56 |

| Maternal educational history: | 0.25 | |||||||

| Less than high school | 183 (41.5%) | 39 (41.5%) | 37 (49.3%) | 36 (47.4%) | 33 (38.4%) | 21 (38.9%) | 17 (30.4%) | |

| High school | 151 (34.2%) | 33 (35.1%) | 21 (28.0%) | 21 (27.6%) | 38 (44.2%) | 16 (29.6%) | 22 (39.3%) | |

| More than high school | 107 (24.3%) | 22 (23.4%) | 17 (22.7%) | 19 (25.0%) | 15 (17.4%) | 17 (31.5%) | 17 (30.4%) | |

| Maternal ever diagnosis of asthma: | 221 (50.2%) | 47 (50.0%) | 36 (48.0%) | 40 (52.6%) | 27 (31.8%) | 38 (70.4%) | 33 (58.9%) | <0.01 |

| Income < 15k | 304 (68.8%) | 61 (64.2%) | 58 (77.3%) | 53 (69.7%) | 54 (62.8%) | 38 (70.4%) | 40 (71.4%) | 0.39 |

|

| ||||||||

| Children | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Child race/ethnicity: | 0.31 | |||||||

| Black | 318 (71.9%) | 69 (72.6%) | 56 (74.7%) | 52 (68.4%) | 58 (67.4%) | 35 (64.8%) | 48 (85.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 87 (19.7%) | 19 (20.0%) | 11 (14.7%) | 17 (22.4%) | 21 (24.4%) | 15 (27.8%) | 4 (7.1%) | |

| Other | 37 (8.4%) | 7 (7.4%) | 8 (10.7%) | 7 (9.2%) | 7 (8.1%) | 4 (7.4%) | 4 (7.1%) | |

| Gestational age (weeks, mean SD) | 38.8 (1.5) | 38.9 (1.44) | 39.0 (1.30) | 38.2 (1.41) | 39.3 (1.35) | 39.1 (1.53) | 38.2 (1.74) | <0.01 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3249 (484) | 3200 (478) | 3332 (462) | 3170 (520) | 3361 (454) | 3296 (465) | 3112 (487) | 0.01 |

| Any eczema (year 1) | 182 (41.8%) | 30 (31.9%) | 27 (36%) | 30 (40.5%) | 40 (47.1%) | 31 (59.6%) | 24 (43.6%) | 0.03 |

| Chronic nasal symptoms (year 10) | 176 (43.7%) | 24 (27.9%) | 22 (32.4%) | 38 (55.9%) | 28 (35.9%) | 29 (58.0%) | 35 (66.0%) | <0.01 |

| Hay fever (year 10) | 80 (22.0%) | 10 (12.5%) | 11 (17.2%) | 10 (16.7%) | 13 (18.6%) | 21 (48.8%) | 15 (32.6%) | <0.01 |

| Asthma diagnosis (year 10) | 124 (29.7%) | 5 (5.7%) | 5 (7.0%) | 38 (54.3%) | 7 (8.4%) | 25 (48.1%) | 44 (81.5%) | <0.01 |

| Bronchodilator reversibility (age 9) | 7.2 (10.2) | 6.5 (8.8) | 6.3 (6.6) | 6.3 (7.5) | 4.9 (8.3) | 5.9 (6.4) | 15.7 (18.4) | <0.01 |

| PC20 (age 10) | 11.3 (10.1) | 13.8 (10.7) | 16.2 (9.8) | 10.8 (10.1) | 9.74 (9.4) | 10.6 (9.7) | 4.58 (6.0) | <0.01 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids in past year (year 10): | 76 (20.1%) | 6 (7.89%) | 4 (6.25%) | 17 (26.2%) | 5 (6.94%) | 16 (32.7%) | 28 (53.8%) | <0.01 |

| Pre-FEV1 % predicted (age 10) | 99.6 (13.1) | 100 (11.9) | 101 (11.8) | 101 (11.6) | 101 (13.7) | 98.7 (13.8) | 94.0 (14.9) | 0.03 |

| Oral corticosteroids in past year (year 10): | 82 (21.7%) | 11 (14.5%) | 6 (9.38%) | 16 (24.6%) | 10 (13.9%) | 17 (34.7%) | 22 (42.3%) | <0.01 |

| Participants with epithelial cells for RNA-seq | 318 (72%) | 69 (73%) | 50 (67%) | 57 (75%) | 61 (71%) | 35 (65%) | 46 (82%) | 0.34 |

|

| ||||||||

| Environmental Exposures | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Smoking during pregnancy (yes) | 80 (18.1%) | 9 (20.5%) | 6 (17.1%) | 9 (25.0%) | 5 (9.8%) | 7 (21.2%) | 7 (25.9%) | 0.45 |

| Cotinine Detected (1st year): | 71 (17.2%) | 18 (20.9%) | 9 (12.5%) | 14 (19.4%) | 10 (12.7%) | 9 (18.4%) | 11 (20.4%) | 0.58 |

| C-section delivery | 135 (30.5%) | 6 (27.4%) | 21 (28.0%) | 22 (28.9%) | 27 (31.4%) | 19 (35.2%) | 20 (35.7%) | 0.84 |

| Ever breastfed: | 240 (56.2%) | 55 (58.5%) | 35 (47.9%) | 40 (56.3%) | 45 (52.9%) | 34 (66.7%) | 31 (58.5%) | 0.42 |

| Number of older siblings | 1.3 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.5) | 1.3 (1.6) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.6) | 1.2 (1.6) | 0.26 |

| Day care attendance (cumulative† hrs) | 37.4 (11.4) | 38.1 (15.7) | 36.5 (10.5) | 37.8 (10.6) | 37.9 (8.7) | 36.6 (9.8) | 37.1 (10.3) | 0.98 |

| Maternal Depression Score (cumulative) | 25.2 (19.2) | 22.4 (17.5) | 27.6 (19.0) | 33.3 (19.8) | 17.6 (14.7) | 27.7 (20.9) | 25.7 (20.9) | <0.01 |

| Maternal Perceived Stress Score (cumulative) | 19.1 (10.4) | 18.4 (10.1) | 20.5 (10.1) | 21.6 (10.3) | 15.2 (8.7) | 20.8 (11.7) | 19.4 (11.0) | <0.01 |

| Allergen exposure index (cumulative‡) | 10.6 (5.6) | 12.5 (5.3) | 11.1 (6.1) | 9.6 (5.6) | 10.9 (5.2) | 10.2 (5.5) | 8.2 (4.8) | <0.01 |

| Microbiota phylogenetic diversity (1st year) | 190 (46.2) | 184 (46.8) | 206 (39.9) | 190 (45.6) | 182 (45.8) | 179 (56.5) | 200 (42.8) | 0.13 |

| Microbiota richness (1st year) | 5544 (1540) | 5338 (1541) | 6072 (1384) | 5539 (1549) | 5289 (1464) | 5143 (1871) | 5926 (1448) | 0.09 |

| House dust endotoxin (cumulative§) | 138 (236) | 160 (279) | 144 (245) | 145 (263) | 96.9 (157) | 172 (277) | 116 (151) | 0.44 |

| House dust ergosterol (cumulative§) | 4.9 (4.4) | 5.3 (4.9) | 5.3 (4.4) | 4.6 (3.5) | 3.7 (3.0) | 4.1 (2.4) | 6.5 (6.7) | 0.02 |

| Home NO measurement (cumulative 1&4 yrs) | 44.1 (38.3) | 42.1 (33.9) | 51.2 (54.8) | 43.9 (37.8) | 43.3 (27.3) | 47.3 (46.4) | 36.4 (21.7) | 0.37 |

Values are counts (percentages%), means (SD), or medians. Because some data may be missing on the variables without a trajectory, the denominators may not be exactly the ones in the column headers. P-values are derived using a Chi-square test for categorical data and F-test for continuous data.

Day care attendance (hours weekly average/three years), Maternal Depression Score and Maternal Perceived Stress Score cumulative over the first 3 years.

Allergen exposure is calculated by combining cat, mouse, cockroach, and dog into a single index based on quartiles of exposure to individual allergens, resulting in a range of 0–12 and cumulative over the first 3 years.

Allergen and endotoxin levels in house dust were measured three times, and ergosterol levels were measured twice during the first 3 years

Several environmental exposures in the first 3 years of life were associated with the respiratory phenotypes (Table I). Scores for maternal depression were highest in the MW-LA group, while maternal perceived stress were greatest in the MW-HA and MW-LA groups. The cumulative allergen exposure index (sum of exposure to the most common indoor allergens across the first 3 years of life) was lowest in the HW-HA-LF group and highest in the LW-LA group. These relationships with allergen exposure through age 7 years were consistent, but at age 10, allergen exposure was no longer inversely related to the respiratory phenotypes (Supplemental Figure 2). Cumulative exposure to ergosterol (measured at ages 1 and 3 years), a cell wall component of fungi, was highest in the HW-HA-LF group (Table I).

Respiratory phenotypes have differing levels of markers of type 2 immunity.

Total serum IgE was increased to a similar degree in the three phenotypes associated with high atopy (Supplemental Figure 3). Associations with temporal patterns of blood eosinophils differed, in that the HW-HA-LF group had consistently higher eosinophil counts than the other two high atopy groups beginning at age 3. FeNO, which was measured at 7 and 10 years of age, was highest in the HW-HA-LF group and was also elevated in the other HA groups and in the MW-LA group.

Respiratory phenotypes show distinct patterns of upper airway epithelial gene expression.

Airway epithelial RNA-sequencing data was available on 318/442 (72%) participants, equally distributed among the 6 phenotype groups. Twenty-six distinct gene expression modules composed of 1,993 genes showed significantly different patterns of expression among the 6 groups by ANOVA after adjusting for the proportions of ciliated epithelial cells, non-ciliated epithelial cells, and leukocytes in each sample, which were not different among the groups. The most prominent module expression signal was in differentiating the HA groups from the low atopy (LA) groups, which formed two distinct clusters (Figure 2A). One functionally important module distinguishing HA from LA was enriched specifically for Th2 and ILC2 genes (“Th2/ILC2”, M12), which was significantly elevated to an equivalent degree in all three HA groups relative to the LA groups (Supplemental Figure 4A). This module is centered around IL13, IL3RA, CD44, IL1RL1 (ST2), GATA1, and CD1B (Supplemental Figure 4B, Supplemental Table 3) and likely represents leukocyte sources of IL-13 in the epithelium. Several groups showed unique patterns of module expression compared to the other groups.

Figure 2.

Differentially expressed modules by respiratory phenotypes. (A) The heatmap shows the 26 differentially expressed modules among the 6 respiratory phenotypes. Module expression levels are shown as row normalized Z-scores of the mean expression for each group (columns) with red representing higher relative expression and blue representing lower expression. The groups are ordered left to right by increasing wheeze within low atopy and high atopy groups as indicated. (B) The differentially expressed modules in the HW-HA-LF group and (C) the differentially expressed modules in the MW-LA group. Differential expression was assessed by ANOVA and post hoc pairwise comparisons using a weighted linear model (limma) appropriate for RNA-seq data and empirical Bayes method. The model included terms to account for cell percentages and city of residence. Significant differences in modules are colored red (increased) or blue (decreased) with the color intensity according the fold change (log2) relative to the group level mean expression. The module network demonstrates the coassociations among all modules identified in this study (squares). Edges represent significant positive Pearson correlations >0.5 (FDR<0.05) and darker edges indicate higher correlations. Nodes are clustered according to their interconnectedness. Group numbers are HW-HA-LF n=46, MW-HA n=35, LW-HA n=61, MW-LA n=57, TW-LA n=50, LW-LA n=69.

HW-HA-LF phenotype has multiple epithelial gene signatures of high type 2 inflammation and impaired innate immunity.

The HW-HA-LF group had the greatest number of differentially expressed modules. Compared to the other 5 phenotypes, there were 6 modules significantly increased and 3 decreased (Figure 2B, Supplemental Table 3). The 6 increased modules generally reflected multifaceted pathways related to type 2 inflammation. “Epithelium response to IL-13” (M4), was upregulated 1.97 fold over the LW-LA group and 1.27 fold over the LW-HA group (FDR<0.001; Figure 3A); this module includes canonical epithelial IL-13 response genes (POSTN, SERPINB2, and CLCA1) mucosal mast cell genes (TPSAB1 and CPA3), and markers of airway eosinophil activation (IL5, CCL26, CCL13, and SIGLEC8) (Figure 3B, Supplemental Table 4). This module was overexpressed in all HA groups but on an increasing continuum from LW-HA to MW-HA to HW-HA-LF, and was also significantly associated with both the degree of obstruction as measured by FEV1/FVC ratio (β-coefficient = −3.1, FDR<0.001) (Figure 3C) and bronchial hyperresponsiveness as measured by PC20 (β-coefficient = −0.11, FDR<0.001) (Figure 3D). “Leukotriene and lipid metabolism” (M11) including ALOX15, LTC4S, and PLCB4, showed a similar pattern of expression to “epithelium response to IL-13” – overexpressed in all HA groups and on an increasing continuum from LW-HA to MW-HA to HW-HA-LF and also showed a direct association with FEV1/FVC and PC20 (FC comparing HW-HA-LF to LW-LA = 1.28, FDR<0.001; β-coefficient FEV1/FVC = −1.2, FDR=0.002; β-coefficient PC20 = −0.039, FDR=0.008) (Supplemental Figure 5A-D). Two modules were specifically elevated only in the HW-HA-LF group relative to the other 5 groups. “MUC5AC hypersecretion” (M21, FC comparing HW-HA-LF to LW-LA = 1.35, FDR<0.05) (Figure 3E) represents a set of functionally interacting genes regulating goblet cell differentiation, mucus hypersecretion, and protein glycosylation. Key genes in this module include MUC5AC, LYZ, FOXA3, GALNT6, TFF1, TFF2, and TFF3 (Figure 3F, Supplemental Table 4). This module also showed an association with FEV1/FVC and PC20 (β-coefficient FEV1/FVC = −1.6, FDR=0.008; β-coefficient PC20 = −0.055, FDR=0.010) (Figure 3G, H). “Tight junctions/cilium” (M2) was similarly specifically increased only in HW-HA-LF (FC comparing HW-HA-LF to LW-LA = 1.23, FDR=0.003) (Supplemental Figure 5E, F). Collectively these results demonstrate multiple aberrant molecular pathways related to both secretory and ciliated epithelial cells as well as epithelial mast cells, which are relatively specific to children who are developing impaired lung function in the setting of multiple allergic sensitizations.

Figure 3.

Modules increased in expression in HW-HA-LF. (A) The log2 expression levels of the “Epithelium response to IL-13” module (M4) according to the six respiratory phenotypes. Shown are median values (horizontal), interquartile ranges (boxes), and 1.5 IQR (whiskers). (B) Gene-gene associations for M4 demonstrate a significant interaction network centered around key genes; shown are the central most genes in the network. Genes are represented as ellipses (nodes) and known gene-gene interactions from STRING as connecting edges. The size of each node is proportional to the number of interactions in the full network. (C) Linear regression of the FEV1/FVC values (shown as a percent) and (D) log2 PC20 values versus the log2 expression levels of M4. Points are colored by phenotype group according to the legend. (E-G) The analogous plots of the MUC5AC hypersecretion module (M21). Group numbers are HW-HA-LF n=46, MW-HA n=35, LW-HA n=61, MW-LA n=57, TW-LA n=50, LW-LA n=69.

Three modules related to innate immune responses were decreased in the HW-HA-LF group. “Innate immune response/myeloid activation” (M5, FC comparing HW-HA-LF to LW-LA = 0.71, FDR=0.006) includes genes involved in macrophage and neutrophil recruitment and activation. The hub genes in this network include S100A8, S100A9, CXCR2, SELL, and ITGB2 (Supplemental Figure 6A, B). “Lysosomal proteins” (M3, FC comparing HW-HA-LF to LW-LA = 0.85, FDR<0.001) (Supplemental Figure 6C, D) contains PTGES and PTGES2 suggesting a decrease in the production of prostaglandin E2. “Antiviral/innate immune response” (M1, FC comparing HW-HA-LF to LW-LA = 0.75, FDR<0.001) includes a large set of type I/III interferon inducible genes, cytokines, and cytokine receptors, complement components, toll-like receptors, and other innate immune genes (Supplemental Figure 6E, F).

MW-LA phenotype has epithelial gene signatures of increased injury and decreased integrity

The MW-LA children (moderate wheezing and a high prevalence of asthma [54.3%] in the absence of allergic sensitizations) had a markedly different module expression profile compared to HW-HA-LF (Figure 2A, C), with low expression of the T2-type inflammatory pathways described above. Instead, the MW-LA group had a relatively unique expression of 3 other modules. Most significant was a specific decrease in expression of an “Epithelial integrity and leukocyte migration” module (M20; FC=0.94, FDR<0.001) including CLDN4, CLDN7, KRT8, RHOA, MYL6, MYL12A, CXCL17, CD9, HLA-A, ANXA1, S100P (Figure 4A, B), showing a decrease in key molecules necessary both for barrier maintenance and facilitation of transepithelial migration of immune cells. Additionally, there was significantly elevated expression of an “Injury response” module including EGF, MTOR, SHC1, and CSNK2A1 (M14; FC comparing MW-LA to LW-LA = 1.06, FDR<0.001) (Figure 4C, D), which was highly inversely associated with “Epithelial integrity and leukocyte migration” within the MW-LA group (β-coefficient = −0.65, FDR=0.002) showing a direct link between decreased expression of barrier function genes with increased injury response genes as a unique pattern to the MW-LA group. One additional module, “Antioxidant activity” (M9) was similarly decreased in both the MW-LA and the TW-LA groups compared to the other 4 groups (FC comparing MW-LA to LW-LA = 0.95, FDR<0.001). This module is enriched for genes with known antioxidant functions (GPX4, PRDX3, PRDX5, MGST3, and SEPW1) and composed in large part of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum membrane proteins. It is notable that the magnitudes of differential module expression in the MW-LA group were overall lower and the stability of this clinical phenotype was less robust than for HW-HA-LF (Supplemental Figure 7), suggesting a higher degree of clinical and molecular variability exists in this group.

Figure 4.

Modules specifically differentially expressed in MW-LA. (A) The log2 expression levels of the “Epithelial integrity and leukocyte migration” module (M20) according to the six respiratory phenotypes. Shown are median values (horizontal), interquartile ranges (boxes), and 1.5 IQR (whiskers). (B) Gene-gene associations for M20 demonstrate a significant interaction network centered around key genes; shown are the central most genes in the network. Genes are represented as ellipses (nodes) and known gene-gene interactions from STRING as connecting edges. The size of each node is proportional to the number of interactions in the full network. (C,D) The analogous plots of the “Injury response” module (M14). Group numbers are HW-HA-LF n=46, MW-HA n=35, LW-HA n=61, MW-LA n=57, TW-LA n=50, LW-LA n=69.

Discussion

Urban minority children have the highest rates of asthma and associated morbidity, and new information to inform asthma prevention in low-income urban areas is critically needed. Using 7 years of data, we had previously identified five respiratory phenotypes in URECA.5 The current analysis based on 10 years of longitudinal information related to symptoms, allergic sensitization, and lung function classified children into six respiratory phenotypes. One difference in the current analysis was the identification of three phenotypes (instead of two in the 7-year analysis) that were highly enriched for the development of asthma, including two groups with high atopy (MW-HA and HW-HA-LF), and a third surprisingly large group with little or no atopy (MW-LA). These phenotypes had specific relationships with environmental exposures in early life, and with patterns of gene expression in the upper airway epithelium.

Of the three asthma-related phenotypes, the HW-HA-LF was characterized by recurrent wheezing illnesses throughout childhood, increased atopy (including the highest blood eosinophils and eNO), and the highest rates of asthma health care utilization. In addition, the HW-HA-LF group, which was newly identified in the 10-year analysis, is of particular importance given the presence of obstructive changes in lung function that appear to be intensifying with age. Early-life risk factors for HW-HA-LF included reduced exposure to common indoor allergens in the home through age 7 years, and increased early-life exposure to ergosterol, a fungal cell wall component. Exposure in early life to mold or excess moisture in the home has been linked to incident asthma during childhood in other studies.34, 35 Interestingly, exposure to allergens in early life was was greatest in the LW-LA group and was inversely related to HW-HA-LF and other wheezing phenotypes. This has been a consistent finding in URECA; cumulative exposure to allergens (cockroach, mouse and cat) was inversely related to recurrent wheeze at age 3 years 31 and asthma and related phenotypes at age 7 years.5, 36 Animal exposure in farm37 and suburban settings38 has also been inversely associated with wheezing and asthma, and these associations with animal exposures are incompletely explained by associated microbial exposures. These findings suggest the possibility that exposure to animal proteins or other animal-associated substances (e.g. DNA, glycoproteins) in early life has beneficial effects on development of immune responses at airway mucosal surfaces.

Compared with the other phenotypic groups, the HW-HA-LF group had higher expression of multiple type-2 pathogenic molecular pathways including periostin, leukotriene metabolism, mucus hypersecretion, markers of eosinophilic inflammation, and mast cell genes, many of which directly associated with the severity of pulmonary dysfunction. Of particular interest was the relatively specific increase in genes of the “MUC5AC hypersecretion” module. This module includes MUC5AC itself, which has been repeatedly demonstrated to be elevated in the lower airways in asthma and contributes to mucus dysfunction and plugging.39 It also includes the co-secretory antimicrobial protein lysozyme (LYZ), the transcriptional activator FOXA3 that induces goblet cell metaplasia,40 GALNT6, which is important in the post-translational modification of MUC5AC, and the three trefoil factors (TFF1, TFF2, TFF3), which are secretory proteins involved in mucosal healing that can interact directly with MUC5AC protein.41, 42 These genes have been previously shown to be upregulated by prolonged allergen exposure in an environmental exposure chamber model.43 At the cellular and molecular level, MUC5AC is expressed in the upper airways, trachea and bronchi44 where, uniquely, it is tethered to secreting club cells45 and its viscosity is increased in the presence of oxidative stress.46 These properties likely link overexpression of MUC5AC to airway obstruction and hyperresponsiveness.47 A variety of external stresses can increase MUC5AC acutely,48 and our findings in the URECA birth cohort suggest that allergic sensitization and frequent viral wheezing episodes in early life, which are characteristic of HW-HA-LF, could promote long-term overexpression of MUC5AC and in turn, lead to progressive airway obstruction.

Interestingly the “Th2/ILC2” module, which included the gene for IL-13 itself and likely represents cellular sources of type-2 cytokines, was similar in expression across all HA groups and did not mediate the observed associations between “epithelium response to IL-13” or “MUC5AC hypersecretion” expression and either FEV1/FVC ratio or PC20. This finding similarly suggests that functional differences in the composition and molecular response of the airway epithelium itself, more than differences in the source or amount of IL-13 production, are linked to loss of lung function in highly atopic individuals. Opposite these finding, the HW-HA-LF group also showed decreased expression of innate immune and antiviral pathways as well as myeloid genes, fitting with observations of frequent viral wheezing episodes and suggesting impaired type 1 immune responses. Taken together, the gene expression changes seen in the HW-HA-LF group reflect multifaceted changes of the airway epithelium reflective of chronic type-2 inflammation and alterations in the types and functions of epithelial associated leukocytes. These results identify in a prospective birth cohort study the potential environmental and cellular origins and progression of early-onset T2-high asthma, as described in several studies of asthma in adults,49 and directly link it to progressive loss of lung function beginning in childhood.

Our results also identified a population of children with moderate wheezing but little or no allergic sensitization, most of whom developed asthma by age 10. This phenotype exhibits features of the so-called “T2-low” asthma that has been described in adults. This population demonstrated a quite distinct and novel gene expression profile defined by decreased expression of genes related to epithelial integrity, in particular those involved in apical epithelial cell-cell adhesion, leukocyte migration and activation, and antioxidant activity along with upregulation of EGF and MTOR mediated injury response signaling. These findings may be consistent with prior observations of epithelial vulnerability and impaired repair responses in childhood wheeze phenotypes independent of atopy.50–52 Moreover, recent work has implicated PI3K/Akt signaling as the potential upstream regulator responsible for epithelial repair vs vulnerability in the airway,50 and animal models of asthma have shown PI3K/Akt signaling, acting through MTOR activation, is closely linked to Th17 inflammation in asthma.53 It is interesting we observe these findings specifically in a low atopy wheeze phenotype, and suggest that PI3K/Akt – MTOR – Th17 pathway54, 55 could be targeted for treatment or prevention of this phenotype. Collectively these findings demonstrate a distinct mechanism underpinning recurrent wheezing and asthma that occurs in the absence of allergic sensitization – one associated with impaired epithelial barrier function, impaired antioxidant capacity, and increased epithelial injury.

Strengths of the study include prospective and frequent evaluation of multiple facets of respiratory symptoms, allergy and lung function beginning at an early age. Integration of these factors into the cluster analysis enabled identification of respiratory phenotypes that were highly related to asthma. The transcriptional signatures in the airway support the biological validity of the respiratory phenotypes and identify key molecular patterns that underpin mechanisms of disease. Our study also has a number of limitations. Given the inaccessibility of lower airway specimens from these children, we analyzed nasal epithelial cell samples, which may not fully reflect lower airway pathology. That said, several recent studies have demonstrated that analyzing upper airway epithelial cells serves as a useful proxy for the lower airway and can provide important insights into mechanisms of childhood asthma.24–26 The study population of urban minority children has among the highest rates of asthma frequency and morbidity and addresses a major gap in knowledge that can be applied to prevention. As such, the study findings may not apply to other populations, and additional studies will be needed to determine whether the results are generalizable.

In conclusion, delineating respiratory phenotypes through early school-age enabled analysis of corresponding early life environmental exposures and patterns of gene expression that suggest potential molecular pathways of disease inception. Additionally, these results show the development of an imprinted end organ – the airway epithelium – which likely orchestrates that pathogenic immune response that drives clinical disease. These findings suggest how the children at risk for persistent asthma endotypes, even among a population already with significant risk of asthma based on demographics, could be recognized early in life from clinical and molecular data. In addition, the results of this study suggest pathways that could be targeted in studies to prevent specific asthma endotypes. Most notably, children developing a HW-HA-LF (T2-high) endotype that can be identified early in life would be excellent candidates for interventions to interrupt mucus secretion pathways (e.g. IL-4/IL-13 receptors) or to boost mucosal immune responses in the airway in order to preserve lung function development. Alternatively, the MW-LA (T2-low) endotype might be prevented by treatments (to be developed) aimed at improving airway epithelial cell barrier function and/or the response to oxidative stress.

Supplementary Material

Key messages:

Clinical observations in urban children can be used to identify respiratory allergy and asthma phenotypes.

These phenotypes can be linked to environmental exposures in early life, and molecular pathways through analysis of nasal epithelial cells.

Funding Acknowledgements:

This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, under Contract numbers 1UM1AI114271-01, UM2AI117870. Additional support was provided by the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, under grant NCRR: UL1TR001079.

Abbreviations:

- FEV1

Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second

- FVC

Forced Vital Capacity

- HW-HA-LF

High wheeze-high atopy-low lung function

- IgE

Immunoglobulin E

- LW-LA

Low wheeze-low atopy

- LW-HA

Low wheeze-high atopy

- MW-LA

Medium wheeze-low atopy

- MW-HA

Medium wheeze-high atopy

- PC20

Provocative concentration of methacholine that results in a 20% drop in FEV1

- RV

Rhinovirus

- TW-LA

Transient wheeze-low atopy

- T-2

Type 2

- Th2

T helper 2

- URECA

Urban Environment and Childhood Asthma

- WGCNA

Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis

Footnotes

Competing Interests: All authors with the exception of P.J.G report grants from NIH/NIAID/DAIT during the conduct of study. L.B.B. reports grant support from NIH/NIAID/NHLBI, Sanofi and Vectura, and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Novartis, Merck, DBV Technologies, Teva, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, WebMD/Medscape, Sanofi, Regeneron, Vectura, and Circassia outside the submitted work. J.E.G reports consulting fees from Regeneron, consulting fees and stock options from Meissa Vaccines Inc and consulting fees from AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. D.J.J reports grants from GlaxoSmithKline and NIH/NHLBI, as well as personal fees from Novartis, Commense, Sanofi/Genzyme, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. M. Kattan reports personal fees from Novartis and Regeneron for service on advisory boards outside the submitted work. R.A.W. reports board membership at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology; employment at Johns Hopkins University; and royalties from UpToDate outside the submitted work. Additionally, R.A.W. reports grants from NIH, DBV Technologies, Aimmune Therapeutics, Astellas Pharma, and HAL Allergy Group outside the submitted work. M.C.A. reports consulting fees from Regeneron outside the submitted work. A.C., C.M.V., G.T.O., S.P., M.G.R., S.R., M.S., and P.J.G have nothing to disclose outside the submitted work.

Data and Materials Availability: The raw RNA-sequencing FASTQ data and Minimum Information about a high-throughput nucleotide SEQuencing Experiment (MINSEQE) have been deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with accession number GSE145505.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zahran HS, Bailey CM, Damon SA, Garbe PL, Breysse PN. Vital Signs: Asthma in Children - United States, 2001–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67:149–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platts-Mills TA. The allergy epidemics: 1870–2010. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 136:3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oksel C, Granell R, Haider S, Fontanella S, Simpson A, Turner S, et al. Distinguishing Wheezing Phenotypes from Infancy to Adolescence. A Pooled Analysis of Five Birth Cohorts. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019; 16:868–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson DJ, Gern JE, Lemanske RF Jr., Lessons learned from birth cohort studies conducted in diverse environments. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139:379–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacharier LB, Beigelman A, Calatroni A, Jackson DJ, Gergen PJ, O’Connor GT, et al. Longitudinal Phenotypes of Respiratory Health in a High-Risk Urban Birth Cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199:71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ, et al. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. N.Engl.J.Med. 1995; 332:133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savenije OE, Granell R, Caudri D, Koppelman GH, Smit HA, Wijga A, et al. Comparison of childhood wheezing phenotypes in 2 birth cohorts: ALSPAC and PIAMA. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127:1505–12 e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belgrave DCM, Simpson A, Semic-Jusufagic A, Murray CS, Buchan I, Pickles A, et al. Joint modeling of parentally reported and physician-confirmed wheeze identifies children with persistent troublesome wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132:575–83 e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang L, Narita M, Yamamoto-Hanada K, Sakamoto N, Saito H, Ohya Y. Phenotypes of childhood wheeze in Japanese children: A group-based trajectory analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2018; 29:606–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Q, Just AC, Miller RL, Perzanowski MS, Goldstein IF, Perera FP, et al. Using latent class growth analysis to identify childhood wheeze phenotypes in an urban birth cohort. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2012; 108:311–5 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sbihi H, Koehoorn M, Tamburic L, Brauer M. Asthma Trajectories in a Population-based Birth Cohort. Impacts of Air Pollution and Greenness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195:607–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granell R, Henderson AJ, Sterne JA. Associations of wheezing phenotypes with late asthma outcomes in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children: A population-based birth cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138:1060–70 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubner FJ, Jackson DJ, Evans MD, Gangnon RE, Tisler CJ, Pappas TE, et al. Early life rhinovirus wheezing, allergic sensitization, and asthma risk at adolescence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139:501–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson DJ, Evans MD, Gangnon RE, Tisler CJ, Pappas TE, Lee WM, et al. Evidence for a causal relationship between allergic sensitization and rhinovirus wheezing in early life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 185:281–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson A, Tan VY, Winn J, Svensen M, Bishop CM, Heckerman DE, et al. Beyond atopy: multiple patterns of sensitization in relation to asthma in a birth cohort study. Am.J.Respir.Crit Care Med. 2010; 181:1200–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein RT, Holberg CJ, Morgan WJ, Wright AL, Lombardi E, Taussig L, et al. Peak flow variability, methacholine responsiveness and atopy as markers for detecting different wheezing phenotypes in childhood. Thorax 1997; 52:946–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belgrave DC, Buchan I, Bishop C, Lowe L, Simpson A, Custovic A. Trajectories of lung function during childhood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189:1101–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Havstad S, Johnson CC, Kim H, Levin AM, Zoratti EM, Joseph CL, et al. Atopic phenotypes identified with latent class analyses at age 2 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134:722–7 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gern JE, Brooks GD, Meyer P, Chang A, Shen K, Evans MD, et al. Bidirectional interactions between viral respiratory illnesses and cytokine responses in the first year of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 117:72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macaubas C, de Klerk NH, Holt BJ, Wee C, Kendall G, Firth M, et al. Association between antenatal cytokine production and the development of atopy and asthma at age 6 years. Lancet 2003; 362:1192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thysen AH, Waage J, Larsen JM, Rasmussen MA, Stokholm J, Chawes B, et al. Distinct immune phenotypes in infants developing asthma during childhood. Sci Transl Med 2020; 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altman MC, Whalen E, Togias A, O’Connor GT, Bacharier LB, Bloomberg GR, et al. Allergen-induced activation of natural killer cells represents an early-life immune response in the development of allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 142:1856–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altman MC, Gill MA, Whalen E, Babineau DC, Shao B, Liu AH, et al. Transcriptome networks identify mechanisms of viral and nonviral asthma exacerbations in children. Nat Immunol 2019; 20:637–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poole A, Urbanek C, Eng C, Schageman J, Jacobson S, O’Connor BP, et al. Dissecting childhood asthma with nasal transcriptomics distinguishes subphenotypes of disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133:670–8 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Guisa JM, Powers C, File D, Cochrane E, Jimenez N, Debley JS. Airway epithelial cells from asthmatic children differentially express proremodeling factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129:990–7.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kicic A, de Jong E, Ling KM, Nichol K, Anderson D, Wark PAB, et al. Assessing the unified airway hypothesis in children via transcriptional profiling of the airway epithelium. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145:1562–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Busse WW. The National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases networks on asthma in inner-city children: an approach to improved care. J.Allergy Clin.Immunol. 2010; 125:529–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gern JE, Visness CM, Gergen PJ, Wood RA, Bloomberg GR, O’Connor GT, et al. The Urban Environment and Childhood Asthma (URECA) birth cohort study: design, methods, and study population. BMC.Pulm.Med. 2009; 9:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005; 26:319–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor GT, Lynch SV, Bloomberg GR, Kattan M, Wood RA, Gergen PJ, et al. Early-life home environment and risk of asthma among inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141:1468–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynch SV, Wood RA, Boushey H, Bacharier LB, Bloomberg GR, Kattan M, et al. Effects of early-life exposure to allergens and bacteria on recurrent wheeze and atopy in urban children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134:593–601 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2008; 9:559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Research 2015; 43:e47-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karvonen AM, Hyvarinen A, Korppi M, Haverinen-Shaughnessy U, Renz H, Pfefferle PI, et al. Moisture damage and asthma: a birth cohort study. Pediatrics 2015; 135:e598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendell MJ, Mirer AG, Cheung K, Tong M, Douwes J. Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness-related agents: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environ Health Perspect 2011; 119:748–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson DJ, Babineau D, Whalen E, Gill MA, Shao B, Liu AH, et al. Eosinophil Gene Activation in the Upper Airway is a Marker of Asthma Exacerbation Susceptibility in Children. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2018; 141:AB114. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loss GJ, Depner M, Hose AJ, Genuneit J, Karvonen AM, Hyvarinen A, et al. The Early Development of Wheeze: Environmental Determinants and Genetic Susceptibility at 17q21. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bufford JD, Reardon CL, Li Z, Roberg KA, DaSilva D, Eggleston PA, et al. Effects of dog ownership in early childhood on immune development and atopic diseases. Clin.Exp.Allergy 2008; 38:1635–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonser LR, Erle DJ. Airway Mucus and Asthma: The Role of MUC5AC and MUC5B. J Clin Med 2017; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen G, Korfhagen TR, Xu Y, Kitzmiller J, Wert SE, Maeda Y, et al. SPDEF is required for mouse pulmonary goblet cell differentiation and regulates a network of genes associated with mucus production. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:2914–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taupin D, Podolsky DK. Trefoil factors: initiators of mucosal healing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003; 4:721–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wills-Karp M, Rani R, Dienger K, Lewkowich I, Fox JG, Perkins C, et al. Trefoil factor 2 rapidly induces interleukin 33 to promote type 2 immunity during allergic asthma and hookworm infection. J Exp Med 2012; 209:607–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larson D, Patel P, Salapatek AM, Couroux P, Whitehouse D, Pina A, et al. Nasal allergen challenge and environmental exposure chamber challenge: A randomized trial comparing clinical and biological responses to cat allergen. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145:1585–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okuda K, Chen G, Subramani DB, Wolf M, Gilmore RC, Kato T, et al. Localization of Secretory Mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B in Normal/Healthy Human Airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199:715–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonser LR, Zlock L, Finkbeiner W, Erle DJ. Epithelial tethering of MUC5AC-rich mucus impairs mucociliary transport in asthma. J Clin Invest 2016; 126:2367–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan S, Hollinger M, Lachowicz-Scroggins ME, Kerr SC, Dunican EM, Daniel BM, et al. Oxidation increases mucin polymer cross-links to stiffen airway mucus gels. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:276ra27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Evans CM, Raclawska DS, Ttofali F, Liptzin DR, Fletcher AA, Harper DN, et al. The polymeric mucin Muc5ac is required for allergic airway hyperreactivity. Nat Commun 2015; 6:6281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boucher RC. Muco-Obstructive Lung Diseases. N Engl J Med 2019; 380:1941–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, et al. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180:388–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iosifidis T, Sutanto EN, Buckley AG, Coleman L, Gill EE, Lee AH, et al. Aberrant cell migration contributes to defective airway epithelial repair in childhood wheeze. JCI insight 2020; 5:e133125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kicic A, Stevens PT, Sutanto EN, Kicic-Starcevich E, Ling KM, Looi K, et al. Impaired airway epithelial cell responses from children with asthma to rhinoviral infection. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2016; 46:1441–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Looi K, Buckley AG, Rigby PJ, Garratt LW, Iosifidis T, Zosky GR, et al. Effects of human rhinovirus on epithelial barrier integrity and function in children with asthma. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2018; 48:513–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Jing Y, Qiao J, Luan B, Wang X, Wang L, et al. Activation of the mTOR signaling pathway is required for asthma onset. Scientific reports 2017; 7:4532-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nagai S, Kurebayashi Y, Koyasu S. Role of PI3K/Akt and mTOR complexes in Th17 cell differentiation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2013; 1280:30–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurebayashi Y, Nagai S, Ikejiri A, Ohtani M, Ichiyama K, Baba Y, et al. PI3K-Akt-mTORC1-S6K1/2 Axis Controls Th17 Differentiation by Regulating Gfi1 Expression and Nuclear Translocation of RORγ. Cell Reports 2012; 1:360–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.