Abstract

Many species of the genus Kalanchoe are important horticultural plants. They have evolved the Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) photosynthetic pathway to allow them to be better adapted to dry environments. Despite their importance, it is still debating whether Kalanchoe is monophyletic, and understanding the past diversification of this genus requires a tremendous amount of effort and work being devoted to the studies of morphological and molecular characters of this genus. However, molecular information, plastic sequence data, in particular, reported on Kalanchoe species is scarce, and this has posed a great challenge in trying to interpret the evolutionary history of this genus. In this study, plastomes of the five Kalanchoe species, including Kalanchoe daigremontiana, Kalanchoe delagoensis, Kalanchoe fedtschenkoi, Kalanchoe longiflora, and Kalanchoe pinnata, were sequenced and analyzed. The results indicate that the five plastomes are comparable in size, guanine-cytosine (GC) contents and the number of genes, which also demonstrate an insignificant difference in comparison with other species from the family Crassulaceae. About 224 simple sequence repeats (SSRs) and 144 long repeats were identified in the five plastomes, and most of these are distributed in the inverted repeat regions. In addition, highly divergent regions containing either single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) or insertion or deletion (InDel) mutations are discovered, which could be potentially used for establishing phylogenetic relationships among members of the Kalanchoe genus in future studies. Furthermore, phylogenetic analyses suggest that Bryophyllum should be placed into one single genus as Kalanchoe. Further genomic analyses also reveal that several genes are undergone positive selection. Among them, 11 genes are involved in important cellular processes, such as cell survival, electron transfer, and may have played indispensable roles in the adaptive evolution of Kalanchoe to dry environments.

Keywords: complete plastid genomes, Bryophyllum, Kalanchoe, phylogenetic relationship, positive selection

Introduction

The genus Kalanchoe Adans. in the family Crassulaceae comprises 144 species (Kubitzki, 2007) and are mainly distributed in the tropical regions of Africa and Asia. Members of this genus typically have succulent leaves, pendulous or erect flowers, and eight stamens inserted in the middle or at the base of the tubular corolla (Baldwin, 1938). Many Kalanchoe species are important horticultural plants for they can be readily propagated from stem cuttings or clonally produced as small plantlets along the leaf margins. When the genus Kalanchoe was first published by Michel Adanson (1727–1806), its taxonomical status with Bryophyllum Salisb. and Kitchingia Baker was not clear (Baldwin, 1938). With advances in molecular technology, the taxonomical status of Kalanchoe has been revisited, and progress has been made in this area in recent years (Van Ham and Hart, 1998; Gehrig et al., 2001; Gontcharova and Gontcharov, 2009; Chernetskyy, 2013; Smith and Figueiredo, 2018). However, most of the work focused on just a few molecular markers, such as rbcL (14 species) and matK (12 species). Based on a few evolutionary studies on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences in Kalanchoe (Gehrig et al., 2001), Kalanchoe has diverged into three groups (Kalanchoe, Bryophyllum, and Kitchingia). However, uncertainty remains, and more work needs to be done to fully elucidate the taxonomical properties and the phylogenetic history of Kalanchoe.

The three-section (sect. Kalanchoe, sect. Bryophyllum, and sect. Kitchingia) view of Kalanchoe (Boiteau and Allorge-Boiteau, 1995) is rather popular and well-accepted. Members of the species from these sections demonstrate differences in flower morphology and geographical distribution. Species of the sect. Kalanchoe tend to have erect flowers. Stamens are connate and located in the middle of the tubular corolla. Members of the sect. Bryophyllum usually bears bulbils along their leaf margins. Flowers are pendent, and sepals fuse to form an inflated tube. Stamens are found at the base of the corolla tube. Species of the sect. Kitchingia share the same flower morphology with the sect. Bryophyllum and the same stamen position with the sect. Kalanchoe, with only one distinction in its floral structure, the spreading of the carpels. Due to the presence of similarities and variations both within and across sections, morphology alone may not be sufficient in putting these species into the right taxonomical groups.

The family Crassulaceae contains both C3 and C4 plant species, and it is evident that these C4 species could have evolved from C3 ancestors by independently acquiring characters required by a C4 system (Christin and Osborne, 2014; Yang et al., 2017). Initially, the ecological distribution of a C4 species is largely determined by the ecological preference of its C3 ancestor. However, as adaptive characters accumulate, the C4 species can “escape and radiate” in a completely new habitat. The sect. Kalanchoe species are widely distributed in tropical Africa and Asia, representing an extremely dry habitat, whereas sect. Bryophyllum and sect. Kitchingia are endemic to Madagascar, a more humid site (Gehrig et al., 2001). The molecular phylogenetic analyses of matK and ITS suggest that Kalanchoe might originate from an allopolyploid C3 species in humid regions of Madagascar, and then spread into arid habitats (Baldwin, 1938; Gehrig et al., 2001, Mort et al., 2001). To adapt to a drier environment, Kalanchoe species have probably gained some drought-resistant traits, such as the coordination of leaves and the CAM photosynthetic pathway, which are enciphered in their genomes and/or plastomes (Yang et al., 2017). To fully understand how Kalanchoe has evolved to become adaptive to arid habitats, as much sequence data as possible should be collected and analyzed.

With the rapid development of next-generation sequencing technology, a large number of genomic sequence data from different taxonomic groups have been obtained and used for phylogenetic studies (Palmer and Stein, 1986; Daniell et al., 2016). Due to the lack of recombination and the ease of amplification, the highly conserved plastid genomes have been widely used to reveal the phylogenetic relationship and evolutionary dynamics among different taxonomic groups (Jansen et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2010; Song et al., 2017; Moner et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). A total number of 34 complete plastid genomes from Crassulaceae have been sequenced and deposited onto the GenBank database. Kalanchoe is one of the largest genera in this family, but little work has been done on the plastid genomes of Kalanchoe. There have been only two species with their plastomes sequenced and analyzed to date, and they are Kalanchoe tomentosa Baker (Zhao et al., 2020) and Kalanchoe daigremontiana Raym.-Hamet and H. Perrier (formerly known as Bryophyllum daigremontianum A. Berger) (Zhou et al., 2021). The lack of sequence data has impeded the progress in determining the structural variations among plastomes of different Kalanchoe species and interpreting the evolutionary history of this genus.

In this study, the complete plastid genomes of five Kalanchoe horticultural plants were sequenced and characterized, aiming the following: (1) to interpret the phylogenetic relationship of the five species based on plastome sequence analyses; (2) to explain why Kalanchoe is better adapted to dry environment at the molecular level based on evolutionary (positive selection) analyses. This study will deepen our understanding of what has happened to the genus Kalanchoe in the history of life and how it has gained the ability to cope with dry environments.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Plant Materials, DNA Extraction, and Sequencing

Fresh leaves of K. daigremontiana, Kalanchoe delagoensis Eckl. and Zeyh. [Formerly known as Bryophyllum delagoense (Eckl. and Zeyh.) Druce], Kalanchoe fedtschenkoi Raym. -Hamet and H. Perrier [formerly as Bryophyllum fedtschenkoi (Raym.-Hamet and H. Perrier) Lauz.-March.], Kalanchoe longiflora Schltr. and Kalanchoe pinnata (Lam.) Pers. [formerly as B. pinnatum (Lam.) Oken] were collected from the greenhouse at Zhengzhou University (Henan, China) (Supplementary Material 1). Samples were flash-frozen and stored at −80°C until use. Total genomic DNA of the five samples was extracted with the Tiangen Plant Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer and Qubit 4 Fluorometer from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA were used to assess the quantity and quality of the total genomic DNA. DNA libraries were constructed using the Illumina Paired-End DNA Library Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced employing the NovaSeq 6000 platform with a paired-end reading length of 150 bp (NovoGene Inc., Beijing, China).

Genome Assembly and Annotation

The raw sequencing data were de novo assembled into complete plastid genomes with the GetOrganelle toolkit following a standard procedure (Jin et al., 2020; https://github.com/Kinggerm/GetOrganelle). Former published plastid genomic sequences of the family Crassulaceae were retrieved from the NCBI database and used as the seed database file. The five complete plastid genomes were annotated using Plastid Genome Annotator (Qu et al., 2019; https://github.com/quxiaojian/PGA) in reference to the plastid genome of K. tomentosa (Accession no. MN794319). Programs, including GeSeq (Tillich et al., 2017), HMMER (Wheeler and Eddy, 2013), tRNAscan-SE version 2.0.6 (Lowe and Eddy, 1997), and GB2sequin (Lehwark and Greiner, 2019) implemented in the CHLOROBOX online toolbox (https://chlorobox.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/geseq.html) were used to check the accuracy of annotation. Physical maps of the circular plastid genomes were generated and visualized using the online program Chloroplot (Zheng et al., 2020; https://irscope.shinyapps.io/chloroplot/).

Comparison of the Five Kalanchoe Plastomes

Comparative analyses were performed between K. tomentosa plastome and the five newly sequenced plastomes. Genomic structures of these plastomes were analyzed and visualized using Irscope (Amiryousefi et al., 2018; https://irscope.shinyapps.io/irapp/).

To identify variable regions and intra-generic variations, the annotated plastomes were visualized using the Shuffle-LAGAN mode included in mVISTA (Frazer et al., 2004; https://genome.lbl.gov/vista/mvista/submit.shtml) with the K. tomentosa plastome as a reference. Features including large single copy (LSC), small single copy (SSC), inverted repeats (IRa and IRb), variable sites, and insertion or deletion (InDel) events across the five Kalanchoe plastomes were detected using DnaSP v6.10.03 (Rozas et al., 2017; http://www.ub.edu/dnasp/). Furthermore, nucleotide diversity (Pi) of plastomes among genus Kalanchoe and family Crassulaceae species (Supplementary Material 1) were calculated using the sliding window method with a window length of 600 bp and a step size of 100 bp.

Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were identified using the MISA web (Beier et al., 2017; http://misaweb.ipk-gatersleben.de/) with the following criteria: 10, 5, 4, 3, 3, and 3 repeat units for mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexa-nucleotides, respectively. REPuter (Kurtz et al., 2001; https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer) was used to identify forward, palindrome, reverse, and complement repeated elements with a minimal length of 30 bp, an identity value of more than 90%, and a Hamming distance of 3.

Phylogenetic Analyses

The five Kalanchoe plastomes were selected for phylogenetic analyses with some closely related genus (Supplementary Material 1). The species Saxifraga stolonifera Curtis (Accession no. MN496079) belonging to the family Saxifragaceae A. L. Jussieu served as the out-group. Complete plastome sequences and protein-coding genes (PCGs) were selected for phylogenetic analyses. A multiple sequence alignment was generated using MAFFT v7.467 (Katoh et al., 2002; https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/). Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis implemented in the IQ-TREE software (Nguyen et al., 2014; http://www.iqtree.org/) and the Bayesian inference (BI) method in the MrBayes software (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001; http://nbisweden.github.io/MrBayes/). For the ML analysis, a bootstrap replicate of 50,000 was performed with the SH-aLRT branch test (Guindon et al., 2010). For the BI analysis, we performed two independent Markov Chain Monte Carlo chains with 2,000,000 generations. The first 25% of trees were discarded. The average SD of split frequencies is below 0.01. Both consensus trees were displayed using the online tool iTOL (Letunic and Bork, 2006; https://itol.embl.de/itol.cgi).

Detection of Positive Selection on Plastidic Genes

Signs of positive selection were determined for each PCGs in the five Kalanchoe plastomes with EasyCodeML v1.31 (Gao et al., 2019; https://github.com/BioEasy/EasyCodeML), and the CodeML model implemented in the PAML package (Yang, 2007; http://web.mit.edu/6.891/www/lab/paml.html). The phylogenetic tree file was generated using the maximum likelihood approach as described in the PAML instruction manual. The ratio (ω) of the non-synonymous substitution rate (dN) to the synonymous substitutions rate (dS) for each PCG was calculated using the site model. The likelihood ratio test of M8a (beta and ω = 1) vs. M8 (beta and ω) was performed to find sites under positive selection. Both the Naive Empirical Bayes (NEB) and the Bayes Empirical Bayes (BEB) approaches (Yang et al., 2005) were employed to assess the posterior probability values.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of the Five Kalanchoe Plastomes

In this study, the five plastome sequence data were obtained using the NovaSeq 6000 platform. The amount of raw data retrieved ranges from 28,988,682 reads for K. delagoensis to 31,184,708 reads for K. pinnata. After trimming, an average of 85.48% of clean reads was obtained and used for de novo assembly (Table 1). The average depth of coverage was 433×, 479×, 417×, 465×, and 520× for the assembled plastid genome of K. daigremontiana, K. delagoensis, K. fedtschenkoi, K. longiflora, and K. pinnata, respectively. The final complete plastome sequence data were submitted to GenBank.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for the assembly of the five Kalanchoe chloroplast genomes.

| Species | K. daigremontiana | K. longiflora | K. pinnata | K. fedtschenkoi | K. delagoensis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 150,049 | 149,978 | 150,056 | 150,001 | 150,018 |

| Large single copy (LSC; bp) | 82,125 | 82,095 | 82,131 | 82,015 | 82,225 |

| Inverted repeats (IR; bp) | 25,469 | 25,413 | 25,469 | 25,487 | 25,392 |

| Small single copy (SSC; bp) | 16,986 | 17,057 | 16,987 | 17,012 | 17,009 |

| Guanine-cytosine (GC) content (LSC/IR/SSC) | 37.6% (35.6/42.9/31.4%) |

37.6% (35.6/43.0/31.4%) |

37.7% (35.7/42.9/31.5%) |

37.7% (35.7/42.9/31.4%) |

37.6% (35.6/43.0/31.4%) |

| Total number of genes (CDS/tRNA/rRNA) | 131 (86/37/8) | 131 (86/37/8) | 131 (86/37/8) | 131 (86/37/8) | 131 (86/37/8) |

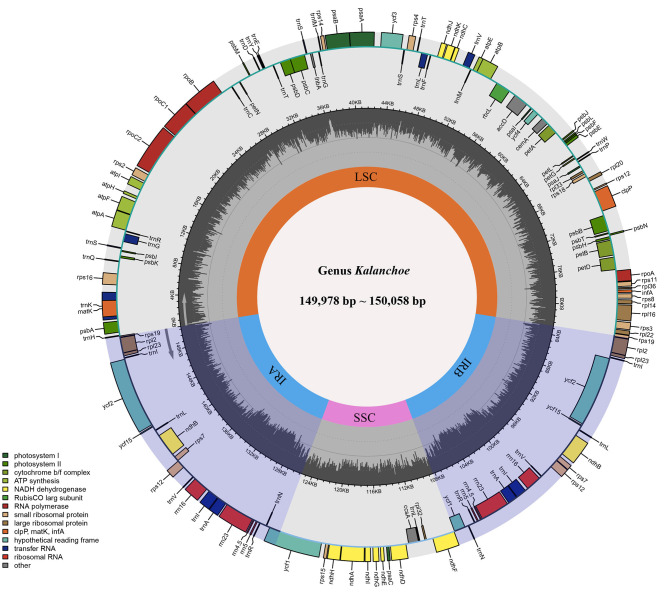

The five plastid genomes of Kalanchoe all possess a typical quadripartite structure, comprising one LSC region and one SSC region separated by a pair of IR regions (IRa and IRb) (Figure 1). This is consistent with the published plastome structures of species from the family Crassulaceae (Dong et al., 2013; Seo and Kim, 2018; Zhao and Zhang, 2018; Chang et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2020; Li and Chen, 2020). The size of these plastomes ranges from 149,978 bp in K. longiflora to 150,056 bp in K. pinnata (Table 1), which is similar to the size of plastomes from other genera of Crassulaceae (Zhao et al., 2020) with only a few exceptions. The five species have larger plastome sizes than Sedum emarginatum (149,118 bp) and Sedum oryzifolium (149,609 bp) (Chang et al., 2020; Li and Chen, 2020). The size of the LSCs ranges from 82,015 bp (K. fedtschenkoi) to 82,225 bp (K. delagoensis) with the estimated guanine-cytosine (GC) content to be 35.6%, whereas the size of the SSCs ranges from 16,986 bp (K. daigremontiana) to 17,057 bp (K. longiflora) with the GC content to be 31.4%, the size of the IRs ranges from 25,392 bp (K. delagoensis) to 25,487 bp (K. fedtschenkoi) with a GC content of 42.9%. The genome size and the GC contents are highly conserved among the five Kalanchoe species, which are also similar to the previously published species from the family Crassulaceae (Xu et al., 2015).

Figure 1.

Gene map and genome organization of the five Kalanchoe plastomes. It exhibits a typical quadripartite structure with a pair of inverted repeat regions (IRA and IRB) separating the small single-copy region (SSC) and the large single-copy region (LSC). Functional genes are also included and color-coded in this map, and guanine-cytosine (GC) contents are drawn.

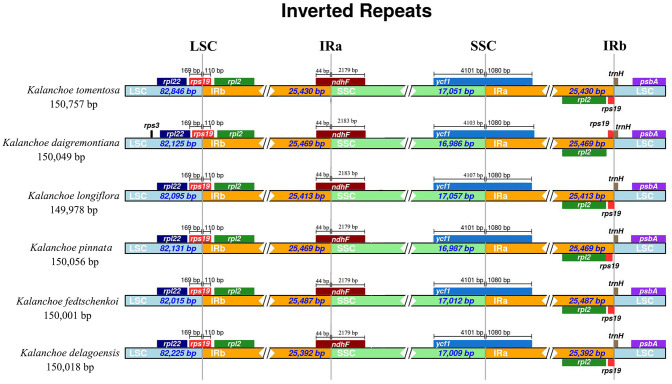

All of the five plastid genomes of Kalanchoe encode 131 genes, containing 86 PCGs, 37 tRNAs, and eight rRNAs (Figure 1). The gene number of each species is similar to that of Rhodiola and other species including Hylotelephium, Orostachys, Phedimus, Rosularia, and Sinocrassula (Zhao et al., 2020). These plastomes contain more genes than that of Hylotelephium verticillatum (128 genes) (Kim and Kim, 2020) and Sedum sarmentosum (113 genes) (Dong et al., 2013). Among all the functional genes, eight PCGs, seven tRNAs, and four rRNAs were found to be duplicated in the IR regions. The distinct junction sites were found between the IR boundaries within the LSC (IRb: rps19; IRa: rps19-trnH) and SSC (IRb: ndhF; IRa: ycf1) regions. Each site is present at a particular position and in a particular length in reference to K. tomentosa (Figure 2). The potential pseudogene rps12 has the duplicated 3′ end in the IR and the 5′ end in the LSC. The identification of distinct junction sites in these plastomes shows that the LSC/IRa boundary is located in the rps12 gene, and a similar pattern was reported in Rhodiola (Zhao et al., 2020). In addition, the SSC/IRb boundary in Rhodiola is located in the intergenic spacer region between ndhF and ycf1, and this is different from Kalanchoe, which has its SSC/IRb boundary located in the ndhF gene (Figure 2). A few comparative genomic studies have proven that IR/LSC or IR/SSC boundary shifts (Wang et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2018; Bedoya et al., 2019; Zavala-Páez et al., 2020) are common in angiosperms and that the instability of distinct junctions was very important in shaping genome structures during plastome evolution (Maréchal and Brisson, 2010; Xu et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2016).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the border positions of large single copy (LSC), inverted repeat B (IRB), small single copy (SSC), and inverted repeat A (IRA) regions across the five Kalanchoe plastomes. Functional genes and truncated fragments are denoted by colored boxes. The sizes of gene fragments located at boundaries are indicated by the base pair lengths.

Comparison of the Five Kalanchoe Plastomes

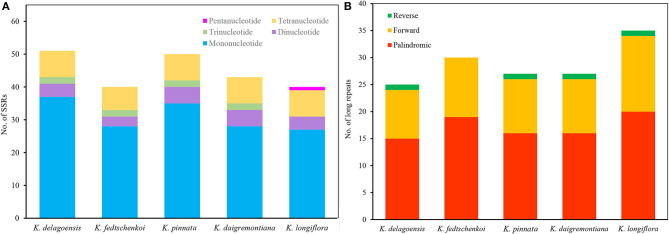

In this study, we detected 224 SSRs in the five Kalanchoe plastomes. Most SSRs were located in the LSC regions. The number of SSRs per species ranges from 40 (K. longiflora and K. fedtschenkoi) to 51 (K. delagoensis). There are 25 to 37 mononucleotide repeats, three to five dinucleotide repeats, two trinucleotide repeats, and seven to eight tetranucleotide repeats in each plastome (Figure 3A). Trinucleotide repeats are absent from the plastome of K. longiflora, whereas pentanucleotide repeats are absent in other species. A total of 144 long repeats (>30 bp) were identified in the five plastid genomes, including 86 palindromic repeats, 54 forward repeats, and four reverse repeats (Figure 3B). Most repeats are shorter than 100 bp, whereas the four palindromic repeats found in K. longiflora are 1,180, 5,671, 8,885, and 9,674 bp in length, indicating a complex structure in the IR regions.

Figure 3.

Analysis of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) (A) and long repeats (B) of the five Kalanchoe plastomes. (A) The number of SSRs with different types, including mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, and pentanucleotides were analyzed among the five Kalanchoe species. (B) The number of long repeats with different types (reverse, forward, and palindromic) present in the five plastomes were also analyzed.

The multiple sequence alignment of the five Kalanchoe plastomes with a length of 151,763 bp revealed a total number of 1,056 polymorphic sites (Pi = 0.00313), including 984 singleton variable sites and 72 parsimony informative sites (Table 2; Supplementary Material 2). Among these polymorphic sites, 490 are positioned in the intergenic regions, 130 are in the introns, and 436 are in the exons (Table 2). Singleton variable sites are abundant in the five plastomes, and a total number of 361 transversions (Tv) and 57 transitions (Ts) were counted in the gene coding regions (Table 3). Among the 57 Ts, 35 are between G and C, whereas 22 are between A and T (Supplementary Material 2). In addition, the 361 Tv are related to changes in the GC contents in different species. For the 436 polymorphic sites in the gene coding regions, only synonymous substitutions (S) were detected in genes related to photosynthesis. Its rate (dS) is comparably low and equals to the rate of having non-synonymous substitutions (dN) in self-replicating genes or other genes (Supplementary Material 2). Similar results are also reported in Machilus (Song et al., 2015). However, a different pattern was observed in ycf1 and ycf2. The dS of ycf1 and ycf2 is relatively higher than dN, supporting the conservation of the photosynthesis-related genes in the plastomes. There are 354 InDel mutations in these five plastomes with 289 in the intergenic regions, 49 in introns, and 16 InDels present in the exons of accD, matK, ycf1, etc (Supplementary Material 2). Furthermore, among these InDel mutations, 118 are SSR InDels, and 34 InDels contain singleton variable sites (Table 2). In addition, InDel mutations occurring in the coding regions are more likely to cause changes to structures of the PCGs. For example, four independent InDel events to ycf2 in K. fedtschenkoi have led to an extra length of seven amino acids in the final amino acid product of this gene (Supplementary Material 2).

Table 2.

Summary statistics for variable sites and insertion or deletion (InDel) mutations of the five Kalanchoe plastomes.

| Polymorphic sites | InDels events | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,056 | 354 |

| SSRs | – | 118 |

| Singleton variable sites | 984 | 34 |

| Intergenic | 490 | 289 |

| Intron | 130 | 49 |

| Extron | 436 | 16 |

| Parsimony informative sites | 72 | – |

Table 3.

Comparisons of mutations, including the number of transversions (Tv), transitions (Ts), synonymous (S), and non-synonymous (N) substitutions per protein-coding genes across the plastomes of the five Kalanchoe species.

| Category | Group of genes | Gene | Tv | Ts | S | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photosynthesis | ATP synthase | atpA | 11 | 0 | 10 | 1 |

| atpE | 9 | 1 | 8 | 2 | ||

| atpF | 6 | 0 | 1 | 5 | ||

| atpI | 8 | 2 | 9 | 1 | ||

| Cytochrome b6/f complex | petA | 5 | 0 | 3 | 2 | |

| petB | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | ||

| petD | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| NADH oxidoreductase | ndhA | 7 | 0 | 4 | 3 | |

| ndhC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| ndhD | 7 | 1 | 5 | 3 | ||

| ndhE | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||

| ndhF | 15 | 4 | 8 | 11 | ||

| ndhG | 6 | 0 | 4 | 2 | ||

| ndhH | 10 | 1 | 9 | 2 | ||

| ndhI | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | ||

| ndhJ | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ndhK | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | ||

| Photosystem I | psaA | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | |

| psaB | 7 | 1 | 7 | 1 | ||

| psaJ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| ycf3 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| ycf4 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||

| Photosystem II | psbA | 5 | 0 | 4 | 1 | |

| psbB | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 | ||

| psbC | 7 | 1 | 7 | 1 | ||

| psbD | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| psbE | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| psbF | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||

| psbI | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| psbJ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| psbK | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| psbT | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Rubisco | rbcL | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| Total | 146 | 19 | 121 | 44 | ||

| Self-replication | DNA dependent RNA polymerase | rpoA | 8 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| rpoB | 12 | 0 | 8 | 4 | ||

| rpoC1 | 13 | 2 | 9 | 6 | ||

| rpoC2 | 26 | 5 | 8 | 23 | ||

| Large subunit of ribosomal proteins | rpl16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| rpl2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| rpl20 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| rpl22 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 7 | ||

| rpl36 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Small subunit of ribosomal proteins | rps11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| rps15 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| rps16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| rps19 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ||

| rps2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| rps3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | ||

| rps4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| rps8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Total | 89 | 15 | 41 | 63 | ||

| Other gene | c-type cytochrom synthesis gene | ccsA | 8 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Envelop membrane protein | cemA | 7 | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| Maturase | matK | 24 | 9 | 9 | 24 | |

| Subunit acetyl-CoA-arboxylase | accD | 10 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |

| Total | 49 | 12 | 16 | 45 | ||

| Unknown gene | Conserved open Reading frames | ycf1 | 67 | 9 | 55 | 21 |

| ycf2 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 11 | ||

| Total | 77 | 11 | 56 | 32 |

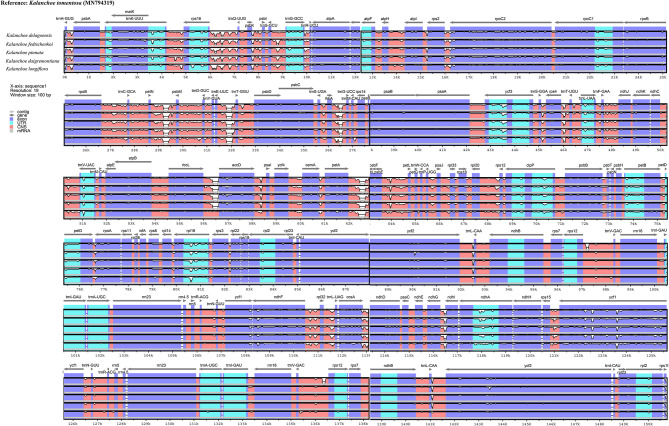

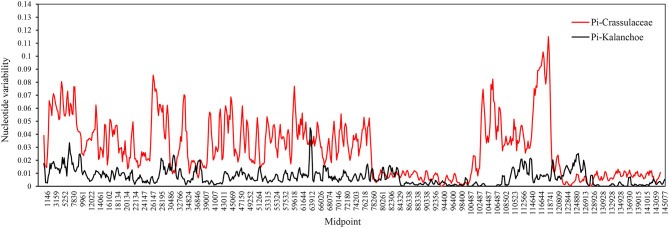

Interspecific comparison among the five Kalanchoe species was established and plotted using mVISTA with the annotated K. tomentosa plastome as a reference (Figure 4). A single universal DNA marker is not sufficient in a large-scale phylogenetic study, especially in studies concerning closely related taxa (Li et al., 2015). Comparing the five plastomes, highly divergent mutations occur in the trnH-psbA, matK, rps16-trnQ, trnE-trnT, rpoC1-rpoB, ycf1, ccsA-ndhD, and ndhG-ndhI regions. This is similar to that in Rhodiola, containing highly divergent sequences in non-coding regions (Zhao et al., 2020). The comparison among these plastomes shows that sequences are more conserved in the IR regions (Pi = 0.00172) than that of the LSC (Pi = 0.00935) and SSC (Pi = 0.01249) regions. Results of the sliding window analysis also suggest that a highly variable mutation is present in the IR regions across all five species from the genus Kalanchoe or from the family Crassulaceae in general (Figure 5). As expected, our study suggests that sequences in the IR regions are less variable than that in the LSC or SSC regions and that sequences in the coding regions are also more conserved than that in the intergenic regions (Walker et al., 2014; Abdullah et al., 2019; Xue et al., 2019). Phylogenetic studies of species from the family Crassulaceae were generally done using matK, rpl16, trnL-F, psbA, psbA-trnH, rps16, and nuclear ITS as molecular markers (Mort et al., 2001, 2005; Acevedo-Rosas et al., 2004; Fairfield et al., 2004; Gontcharova et al., 2006; Carrillo-Reyes et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2014; Nikulin et al., 2016; Ito et al., 2017), and some major crown clades of Crassulaceae have been defined. However, the evolutionary relationship of this family has not been fully elucidated. The highly variable regions identified in this study, containing either SNPs or InDels, would serve prominent roles in identifying potential DNA barcoding markers in further systematic and phylogenetic studies of the family Crassulaceae.

Figure 4.

Sequence identity plot comparing the five plastomes using mVista with Kalanchoe tomentosa (Accession no. MN794319) as a reference. The y-axis corresponds to percentage identity (50–100%), while the x-axis shows the position of each region within the locus. Arrows indicate the transcription of annotated genes in the reference genome.

Figure 5.

Sliding window analysis between the Kalanchoe plastome (black line) and the family Crassulaceae plastome (red line). Window size: 600 bp, step size: 200 bp. X-axis: the position of the midpoint of a window (kb). Y-axis: nucleotide diversity of each window.

Evolutionary Analyses of the Five Kalanchoe Species

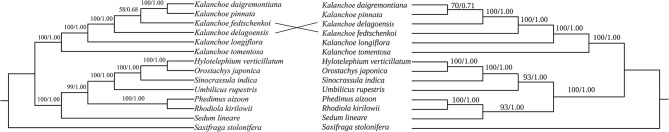

The phylogenetic trees generated with either the five whole plastomes or the PCGs are identical in topology for both ML and BI methods (Figure 6). Kalanchoe and Bryophyllum are grouped in one clade in both trees with high bootstrap values, and this is consistent with the result of the phylogenetic study based on matK (Mort et al., 2001). This grouping is further supported by a morphological similarity shared by Bryophyllum and Kalanchoe, they both possess fused corolla (Gehrig et al., 2001; Mort et al., 2001).

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Kalanchoe genus using the Complete chloroplast genome sequences (left; A) and PCQ sequences (right; B) data with Saxifraga stolonifera as the outgroup for rooting. Bootstrap value/posterior probability are shown on the corresponding branch.

The inferred phylogenetic relationship of the five Kalanchoe species is highly correlated with their morphology with only a few exceptions (BS = 100; PP = 1.00). K. tomentosa and K. longiflora are both placed in the Kalanchoe clade (Gehrig et al., 2001) even though they demonstrate different leaf and stem morphologies. K. daigremontiana, K. pinnata, K. fedtschenkoi, and K. delagoensis, which were formerly classified as Bryophyllum (Smith and Figueiredo, 2018), are now present in the Kalanchoe clade (Figures 6A,B). Being different from the ITS analysis (Gehrig et al., 2001), a closer phylogenetic relationship can be referred to between K. daigremontiana and K. fedtschenkoi, and both of them have sessile leaves and toothed apex (Baldwin, 1938). The phylogenetic relationship among K. daigremontiana, K. pinnata, and K. fedtschenkoi was weakly supported in this study. In addition, we inferred that morphological similarities among different species could be due to interspecific hybridization and rapid radiation of this genus (Baldwin, 1938), which might have led to species delimitation under certain circumstances (Izumikawa et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2020).

Likelihood ratio test employing the M8a vs. M8 model would produce slightly biased results in adaptive evolution analysis (Wong et al., 2004; Berlin and Smith, 2005). In this study, sites under positive selection were identified in the five Kalanchoe plastomes (Supplementary Material 3). Eleven genes with sites under positive selection were identified using both the NEB and BEB methods (Table 4). Those genes are ccsA, clpP, ndhD, ndhF, ndhI, psbL, rbcL, rpoA, rps8, rps15, and ycf1. The number of positively selected sites ranges from 1 to 6 in each gene. The 11 genes are thought to be essential to processes related to photorespiration (Shikanai et al., 2001; Kikuchi et al., 2013) and may have been involved in the evolution of the CAM pathway. Kalanchoe species with the CAM photosynthetic pathway (Gehrig et al., 2001) are generally distributed in dry habitats, indicating that Kalanchoe species have adopted a better way of fixing CO2. It has also made them more adaptive to extreme dry environments in Madagascar and Africa. The role of these genes in the adaptation of Kalanchoe to a dry environment is further supported by the fact that these genes are not under positive selection pressure in the genus Rhodiola distributed in an alpine environment (Zhao et al., 2020).

Table 4.

Detection of sites under positive selection using the likelihood ratio test.

| Genes | Model | Ln L | Estimates of parameters | Models compared | 2ΔLNL | LRT p-value | Positively selected sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ccsA | M8 | −2,260.95 | p0 = 0.94 p = 25.44 q = 99.00 (p1 = 0.06) w = 2.77 |

||||

| M8a | −2,264.82 | p0 = 0.82 p = 14.87 q = 99.00 (p1 = 0.18) w = 00 |

M8a vs. M8 | 7.75 | 0.01 | 168 H** 174 P* | |

| clpP | M8 | −1,043.18 | p0 = 0.99 p = 0.33 q = 1.55 (p1 = 0.01) w=55.05 |

||||

| M8a | −1,049.96 | p0 = 0.88 p = 4.00 q = 65.89 (p1 = 0.12) w = 1.00 |

M8a vs. M8 | 13.55 | 0.00 | 43 S** | |

| ndhD | M8 | −3,316.08 | p0 = 1.00 p = 0.04 q = 0.20 (p1 = 0.00) w = 8.97 |

||||

| M8a | −3,319.73 | p0 = 0.93 p = 0.51 q = 7.82 (p1 = 0.07) w = 1.00 |

M8a vs. M8 | 7.31 | 0.01 | 1 M** | |

| ndhF | M8 | −3,460.77 | p0 = 0.99 p= 0.29 q= 1.24 (p1= 0.01) w= 4.44 |

||||

| M8a | −3,464.42 | p0 = 0.87 p = 2.44 q = 24.04 (p1 = 0.12) w = 1.00 |

M8a vs. M8 | 7.31 | 0.01 | 215 F* 484 Q** | |

| ndhI | M8 | −1,009.15 | p0 = 0.98 p = 0.04 q = 0.28 (p1 = 0.02) w = 5.29 |

||||

| M8a | −1,009.75 | p0 = 0.90 p = 0.01 q = 0.28 (p1 = 0.09) w = 1.00 |

M8a vs. M8 | 1.21 | 0.27 | 161 V** | |

| psbL | M8 | −187.74 | p0 = 0.94 p = 0.01 q = 2.38 (p1 = 0.06) w = 15.22 |

||||

| M8a | −192.14 | p0 = 0.84 p = 0.01 q = 99.00 (p1 = 0.16) w = 1.00 |

M8a vs. M8 | 8.81 | 0.00 | 1 T** 10 N* | |

| rbcL | M8 | −2,579.79 | p0 = 0.97 p = 0.15 q = 3.55 (p1 = 0.03) w = 2.70 |

||||

| M8a | −2,581.89 | p0 = 0.92 p = 0.01 q = 3.23 (p1 = 0.08) w = 1.00 |

M8a versus M8 | 4.20 | 0.04 | 28 E* 97 Y* 225 I** 228 S** 328 S* 429 Q* 475 I* | |

| rpoA | M8 | −2,316.12 | p0 = 0.99 p = 0.15 q = 0.46 (p1 = 0.01) w = 17.07 |

||||

| M8a | −2,328.18 | p0 = 0.82 p = 7.55 q = 99.00 (p1 = 0.18) w = 1.00 |

M8a versus M8 | 24.12 | 0.00 | 311 R** 333 L** | |

| rps8 | M8 | −884.00 | p0 = 0.98 p = 1.80 q = 4.03 (p1 = 0.02) w = 9.24 |

||||

| M8a | −888.62 | p0 = 0.78 p = 15.02 q = 99.00 (p1 = 0.22) w = 1.00 |

M8a vs. M8 | 9.24 | 0.00 | 52 R** 56 N** | |

| rps15 | M8 | −695.64 | p0 = 0.95 p = 0.74 q = 3.83 (p1 = 0.05) w = 5.44 |

||||

| M8a | −701.07 | p0 = 0.86 p = 7.26 q = 99.00 (p1 = 0.14) w = 1.00 |

M8a vs. M8 | 10.85 | 0.00 | 7 F** 33 N* 67 V** | |

| ycf1 | M8 | −12,401.09 | p0 = 0.98 p = 0.20 q = 0.22 (p1 = 0.02) w = 4.86 |

||||

| M8a | −12,423.25 | p0 = 0.60 p = 12.56 q = 99.00 (p1 = 0.40) w = 1.00 |

M8a vs. M8 | 44.33 | 0.00 | 445 N** 542 R** 592 M** 672 V** 953 D** 1080 Q** 1295 S* |

Posterior probability values were assessed with both Naive Empirical Bayes (NEB) and Bayes Empirical Bayes (BEB) approaches.

Denotes positively selected sites supported by either NEB or BEB method (p < 0.05).

Denotes positively selected sites supported by both NEB and BEB methods (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the complete plastid genomes of the five Kalanchoe species, such as K. daigremontiana, K. delagoensis, K. fedtschenkoi, K. longiflora, and K. pinnata, were sequenced and analyzed. In general, the size, structure, GC contents, and the number of genes are similar to other Crassulaceaen plastid genomes. Despite these similarities, several SSRs and divergent regions were detected, and they were used in interpreting the evolutionary relationship of the five species. Phylogenetic analyses based on these five whole plastomes and the PCGs produced well-supported values, which allow us to infer the phylogenetic relationship of these species with high confidence levels. Our results support that Bryophyllum and Kalanchoe should be treated as one single genus and that they have evolved a series of positively selected genes related to the CAM photosynthetic carbon assimilation pathway. These findings suggest that the plastid genome can be used as an informative genetic marker for improving our understandings of speciation and diversification in Kalanchoe, most of which are drought-resistant succulent plants.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

XT and YS conceived the idea and designed the research. XZ and TS conducted the experiments. XZ, YM, and KM conducted the collection of specimens. XT and JG wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Man Yang, Ya-Qi Lv, Tian Li, and Shi-Long Wang from Zhengzhou University for assembling and annotating the five plastomes. We further thank Lu-Ye Shi for his critical review of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the Key Laboratory of Medicinal Animal and Plant Resources of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (Grant No. 2020-ZJ-Y40).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.705874/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abdullah S. I., Mehmood F., Ali Z., Malik M. S., Waseem S., Mirza B., et al. (2019). Comparative analyses of chloroplast genomes among three Firmiana species: Identification of mutational hotspots and phylogenetic relationship with other species of Malvaceae. Plant Gene 19:100199. 10.1016/j.plgene.2019.100199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Rosas R., Cameron K., Sosa V., Pell S. (2004). A molecular phylogenetic study of Graptopetalum (Crassulaceae) based on ETS, ITS, RPL16, and TRNL-F nucleotide sequences. Am. J. Bot. 91, 1099–1104. 10.3732/ajb.91.7.1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiryousefi A., Hyvönen J., Poczai P. (2018). IRscope: an online program to visualize the junction sites of chloroplast genomes. Bioinformatics 34, 3030–3031. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J. T. (1938). Kalanchoe: the genus and its chromosomes. Am. J. Bot. 25, 572–579. 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1938.tb09263.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoya A. M., Ruhfel B. R., Philbrick C. T., Madriñán S., Bove C. P., Mesterházy A., et al. (2019). Plastid genomes of five species of riverweeds (Podostemaceae): structural organization and comparative analysis in malpighiales. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1035–1035. 10.3389/fpls.2019.01035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier S., Thiel T., Münch T., Scholz U., Mascher M. (2017). MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 33, 2583–2585. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin S., Smith N. G. C. (2005). Testing for adaptive evolution of the female reproductive protein ZPC in mammals, birds and fishes reveals problems with the M7-M8 likelihood ratio test. BMC Evolut. Biol. 5:65. 10.1186/1471-2148-5-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiteau P., Allorge-Boiteau L. (1995). Kalanchoe (Crassulacées) de Madagascar: systématique, écophysiologie et phytochimie. Paris: Karthala Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Reyes P., Sosa V., Mort M. E. (2008). Thompsonella and the “Echeveria group” (Crassulaceae): phylogenetic relationships based on molecular and morphological characters. Taxon 57, 863–874. 10.1002/tax.573015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H., Tang Y., Xu X. (2020). The complete chloroplast genome of Sedum emarginatum (Crassulaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 5, 3082–3083. 10.1080/23802359.2020.1797567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernetskyy M. (2013). Problems in nomenclature and systematics in the subfamily Kalanchoideae (Crassulaceae) over the years. Acta Agrobotanica 64, 67–74. 10.5586/aa.2011.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christin P. A., Osborne C. P. (2014). The evolutionary ecology of C4 plants. New Phytol. 204, 765–781. 10.1111/nph.13033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniell H., Lin C. S., Yu M., Chang W. J. (2016). Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 17:134. 10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Xu C., Cheng T., Zhou S. (2013). Complete chloroplast genome of Sedum sarmentosum and chloroplast genome evolution in saxifragales. PLoS ONE 8:e77965. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairfield K. N., Mort M. E., Santos-Guerra A. (2004). Phylogenetics and evolution of the Macaronesian members of the genus Aichryson (Crassulaceae) inferred from nuclear and chloroplast sequence data. Plant Syst. Evolut]. 248, 71–83. 10.1007/s00606-004-0190-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer K. A., Pachter L., Poliakov A., Rubin E. M., Dubchak I. (2004). VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:W273–W279. 10.1093/nar/gkh458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F., Chen C., Arab D. A., Du Z., He Y., Ho S. Y. W. (2019). EasyCodeML: a visual tool for analysis of selection using CodeML. Ecol. Evolut. 9, 3891–3898. 10.1002/ece3.5015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Zhang X., Meng H., Li J., Zhang D., Liu C. (2018). Comparative chloroplast genomes of Paris Sect. Marmorata: insights into repeat regions and evolutionary implications. BMC Genom. 19:878. 10.1186/s12864-018-5281-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrig H., Gaußmann O., Marx H., Schwarzott D., Kluge M. (2001). Molecular phylogeny of the genus Kalanchoe (Crassulaceae) inferred from nucleotide sequences of the ITS-1 and ITS-2 regions. Plant Sci. 160, 827–835. 10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00447-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gontcharova S. B., Artyukova E. V., Gontcharov A. A. (2006). Phylogenetic relationships among members of the subfamily Sedoideae (Crassulaceae) inferred from the ITS region sequences of nuclear rDNA. Russian J. Genet. 42, 654–661. 10.1134/S102279540606010X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gontcharova S. B., Gontcharov A. A. (2009). Molecular phylogeny and systematics of flowering plants of the family Crassulaceae, D. C. Mol. Biol. 43:794. 10.1134/S0026893309050112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J. F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. (2010). New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321. 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck J. P., Ronquist F. (2001). MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17, 754–755. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Yu C. C., Nakamura K., Chung K. F., Yang Q. E., Fu C. X., et al. (2017). Unique parallel radiations of high-mountainous species of the genus Sedum (Crassulaceae) on the continental island of Taiwan. Mol. Phylogenet. Evolut. 113, 9–22. 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumikawa Y., Takei S., Nakamura I., Mii M. (2008). Production and characterization of inter-sectional hybrids between Kalanchoe spathulata and K. laxiflora (= Bryophyllum crenatum). Euphytica 163, 123–130. 10.1007/s10681-007-9619-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R. K., Cai Z., Raubeson L. A., Daniell H., dePamphilis C. W., Leebens-Mack J., et al. (2007). Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104:19369. 10.1073/pnas.0709121104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J., Yu W., Yang J., Song Y., dePamphilis C. W., Yi T., et al. (2020). GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. (2020) 21:241. 10.1186/s13059-020-02154-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Misawa K., Kuma K.i, Miyata T. (2002). MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066. 10.1093/nar/gkf436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi S., Bédard J., Hirano M., Hirabayashi Y., Oishi M., Imai M., et al. (2013). Uncovering the protein translocon at the chloroplast inner envelope membrane. Science 339:571. 10.1126/science.1229262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Kim S. (2020). Plastid genome of stonecrop Hylotelephium verticillatum (Sedoideae; Crassulaceae): insight into structure and phylogenetic position. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 5, 2729–2731. 10.1080/23802359.2020.1788464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubitzki K. (2007). Flowering Plants. Eudicots. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S., Choudhuri J. V., Ohlebusch E., Schleiermacher C., Stoye J., Giegerich R. (2001). REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4633–4642. 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehwark P., Greiner S. (2019). GB2sequin - a file converter preparing custom GenBank files for database submission. Genomics 111, 759–761. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Bork P. (2006). Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics 23, 127–128. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Chen D. (2020). The complete chloroplast genome sequence of medicinal plant, Sedum oryzifolium. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 5, 2301–2302. 10.1080/23802359.2020.1772695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Yang Y., Henry R. J., Rossetto M., Wang Y., Chen S. (2015). Plant DNA barcoding: from gene to genome. Biol. Rev. 90, 157–166. 10.1111/brv.12104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Li X., Li M., Xu W., Schwarzacher T., Heslop-Harrison J. S. (2020). Comparative chloroplast genome analyses of Avena: insights into evolutionary dynamics and phylogeny. BMC Plant Biol. 20:406. 10.1186/s12870-020-02621-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe T. M., Eddy S. R. (1997). tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964. 10.1093/nar/25.5.955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maréchal A., Brisson N. (2010). Recombination and the maintenance of plant organelle genome stability. New Phytol. 186, 299–317. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moner A. M., Furtado A., Henry R. J. (2018). Chloroplast phylogeography of AA genome rice species. Mol. Phylogenet. Evolut. 127, 475–487. 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J., Soltis P. S., Bell C. D., Burleigh J. G., Soltis D. E. (2010). Phylogenetic analysis of 83 plastid genes further resolves the early diversification of eudicots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107:4623. 10.1073/pnas.0907801107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mort M. E., Levsen N., Randle C. P., Van Jaarsveld E., Palmer A. (2005). Phylogenetics and diversification of Cotyledon (Crassulaceae) inferred from nuclear and chloroplast DNA sequence data. Am. J. Bot. 92, 1170–1176. 10.3732/ajb.92.7.1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mort M. E., Soltis D. E., Soltis P. S., Francisco-Ortega J., Santos-Guerra A. (2001). Phylogenetic relationships and evolution of Crassulaceae inferred from matK sequence data. Am. J. Bot. 88, 76–91. 10.2307/2657129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L.-T., Schmidt H. A., von Haeseler A., Minh B. Q. (2014). IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evolut. 32, 268–274. 10.1093/molbev/msu300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulin V. Y., Gontcharova S. B., Stephenson R., Gontcharov A. A. (2016). Phylogenetic relationships between Sedum L. and related genera (Crassulaceae) based on ITS rDNA sequence comparisons. Flora 224, 218–229. 10.1016/j.flora.2016.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer J. D., Stein D. B. (1986). Conservation of chloroplast genome structure among vascular plants. Curr. Genet. 10, 823–833. 10.1007/BF00418529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X. J., Moore M. J., Li D. Z., Yi T. S. (2019). PGA: a software package for rapid, accurate, and flexible batch annotation of plastomes. Plant Methods 15:50. 10.1186/s13007-019-0435-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J., Ferrer-Mata A., Sánchez-DelBarrio J. C., Guirao-Rico S., Librado P., Ramos-Onsins S. E., et al. (2017). DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evolut. 34, 3299–3302. 10.1093/molbev/msx248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo H., Kim S. (2018). The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Phedimus kamtschaticus (Crassulaceae) in Korea. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 3, 227–228. 10.1080/23802359.2018.1437819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikanai T., Shimizu K., Ueda K., Nishimura Y., Kuroiwa T., Hashimoto T. (2001). The chloroplast clpP gene, encoding a proteolytic subunit of ATP-dependent protease, is indispensable for chloroplast development in tobacco. Plant Cell Physiol. 42, 264–273. 10.1093/pcp/pce031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. F., Figueiredo E. (2018). The infrageneric classification and nomenclature of Kalanchoe Adans. (Crassulaceae), with special reference to the southern African species. Bradleya 111, 162–172. 10.25223/brad.n36.2018.a10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Dong W., Liu B., Xu C., Yao X., Gao J., et al. (2015). Comparative analysis of complete chloroplast genome sequences of two tropical trees Machilus yunnanensis and Machilus balansae in the family Lauraceae. Front. Plant Sci. 6:662. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Yu W., Tan Y., Liu B., Yao X., Jin J., et al. (2017). Evolutionary comparisons of the chloroplast genome in lauraceae and insights into loss events in the magnoliids. Genome Biol. Evolut. 9, 2354–2364. 10.1093/gbe/evx180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillich M., Lehwark P., Pellizzer T., Ulbricht-Jones E. S., Fischer A., Bock R., et al. (2017). GeSeq– versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W6–W11. 10.1093/nar/gkx391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ham R. C. H. J., Hart H. (1998). Phylogenetic relationships in the Crassulaceae inferred from chloroplast DNA restriction-site variation. Am.J. Bot. 85, 123–134. 10.2307/2446561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. F., Zanis M. J., Emery N. C. (2014). Comparative analysis of complete chloroplast genome sequence and inversion variation in Lasthenia burkei (Madieae, Asteraceae). Am. J. Bot. 101, 722–729. 10.3732/ajb.1400049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.-X., Liu H., Moore M. J., Landrein S., Liu B., Zhu Z.-X., et al. (2020). Plastid phylogenomic insights into the evolution of the Caprifoliaceae s.l. (Dipsacales). Mol. Phylogenet. Evolut. 142:106641. 10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Qu X., Chen S., Li D., Yi T. (2017). Plastomes of Mimosoideae: structural and size variation, sequence divergence, and phylogenetic implication. Tree Genet. Genom. 13:41. 10.1007/s11295-017-1124-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler T. J., Eddy S. R. (2013). nhmmer: DNA homology search with profile HMMs. Bioinformatics 29, 2487–2489. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong W. S., Yang Z., Goldman N., Nielsen R. (2004). Accuracy and power of statistical methods for detecting adaptive evolution in protein coding sequences and for identifying positively selected sites. Genetics 168, 1041–1051. 10.1534/genetics.104.031153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. H., Liu Q., Hu W., Wang T., Xue Q., Messing J. (2015). Dynamics of chloroplast genomes in green plants. Genomics 106, 221–231. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2015.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue S., Shi T., Luo W., Ni X., Iqbal S., Ni Z., et al. (2019). Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome among Prunus mume, P. armeniaca, and P. salicina. Horticult. Res. 6:89. 10.1038/s41438-019-0171-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Hu R., Yin H., Jenkins J., Shu S., Tang H., et al. (2017). The Kalanchoë genome provides insights into convergent evolution and building blocks of crassulacean acid metabolism. Nat. Commun. 8:1899. 10.1038/s41467-017-01491-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. (2007). PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evolut. 24, 1586–1591. 10.1093/molbev/msm088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Wong W. S. W., Nielsen R. (2005). Bayes empirical bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol. Biol. Evolut. 22, 1107–1118. 10.1093/molbev/msi097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala-Páez M., Vieira Ld N., de Baura V. A., Balsanelli E., de Souza E. M., Cevallos M. C., et al. (2020). Comparative Plastid Genomics of Neotropical Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae; Epidendroideae). Front. Plant Sci. 11, 799–799. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Q., Meng S. Y., Wen J., Rao G. Y. (2014). Phylogenetic relationships and character evolution of Rhodiola (Crassulaceae) based on nuclear ribosomal ITS and plastid trnL-F and psbA-trnH sequences. System. Bot. 39:441–51, 11. 10.1600/036364414X680753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D., Ren Y., Zhang J. (2020). Conservation and innovation: plastome evolution during rapid radiation of Rhodiola on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Mol. Phylogenet. Evolut. 144:106713. 10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D., Zhang J. (2018). Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of the traditional medicinal plants Rhodiola rosea (Saxifragales: Crassulaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 3, 753–754. 10.1080/23802359.2018.1483774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S., Poczai P., Hyvönen J., Tang J., Amiryousefi A. (2020). Chloroplot: an online program for the versatile plotting of organelle genomes. Front. Genet. 11, 576124–576124. 10.3389/fgene.2020.576124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Liu L., Xu L., Song K., Shi Y., Shi T., et al. (2021). The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Bryophyllum daigremontianum (Crassulaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 6, 368–369. 10.1080/23802359.2020.1867015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu A., Guo W., Gupta S., Fan W., Mower J. P. (2016). Evolutionary dynamics of the plastid inverted repeat: the effects of expansion, contraction, and loss on substitution rates. New Phytol. 209, 1747–1756. 10.1111/nph.13743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.