Abstract

COVID-19 has swept quickly across the world with a worrisome death toll. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces cytokine storm, acute respiratory distress syndrome with progressive lung damage, multiple organ failure, and even death. In this review, we summarize the pathophysiologic mechanism of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and hypoxia in three main phases, focused on lung inflammation and thrombosis. Furthermore, microparticle storm resulted from apoptotic blood cells are central contributors to the generation and propagation of thrombosis. We focus on microthrombi in the early stage and describe in detail combined antithrombotic with fibrinolytic therapies to suppress microthrombi evolving into clinical events of thrombosis. We further discuss pulmonary hypertension causing plasmin, fibrinogen and albumin, globulin extruding into alveolar lumens, which impedes gas exchange and induces severe hypoxia. Hypoxia in turn induces pulmonary hypertension, and amplifies ECs damage in this pathophysiologic process, which forms a positive feedback loop, aggravating disease progression. Understanding the mechanisms paves the way for current treatment of COVID-19 patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, neutrophil extracellular traps, hypoxia, thrombosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, treatment strategy

Introduction

COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The clinical symptoms of some patients include rapid progression from mild symptoms to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multiple organ failure (MOF), and even death. Excessive pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as Interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and Interleukin (IL)-1β, are described in a cytokine storm [1]. Reports of thrombotic events are frequent and preventive antithrombic therapy in clinical practice is required for hospitalized patients. Previous studies suggested that thrombosis was associated with platelet activation, endothelial cell (EC) dysfunction, inflammation, and the complement system. Recent studies have revealed neutrophil infiltration in the alveoli and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) formation in serum in COVID-19 patients, which is predictive of adverse results [2]. The excessive or inappropriate production of NETs occurs in various pathologic processes, including inflammation, thrombosis, ARDS, and MOF. However, the underlying mechanism of NETs that triggers severe thrombotic illness in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients is not yet completely understood.

Progression from virus invasion to systemic hyperinflammation

SARS-CoV-2 infection mainly consists of three phases: the initial phase including viral invasion and minor symptoms; the second phase involving coagulation abnormalities and respiratory symptoms (pulmonary phase); the third phase with progression to systemic thrombosis, hyperinflammatory state, and MOF (systemic hyperinflammatory phase) [3]. NETs are strongly implicated in disease progression and adverse outcome. Recent reports have highlighted the role of NETs in COVID-19 patients [4]. Therefore, we elucidate the important role of NETs in the three phases.

Phase I: viral invasion and minor symptoms

In the first phase, the SARS-CoV-2 invades cells in the mucous membranes and ultimately reaches the lungs by the respiratory tract. Viral Spike (S) protein binds with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and is initiated by the transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), leading to virus infection, infiltration and proliferation in the lung parenchyma. Neutrophil elastase (NE), the main component of NETs, results in S protein cleavage and entry into cells directly from the cell surface, increasing viral infectivity [5]. SARS-CoV-2 infects lung tissue and induces necrosis and sloughing of alveolar epithelial cells, which results in inflammatory cell infiltration and pro-inflammatory cytokine release in the lungs [6]. Infiltrated neutrophil and other immune cells consume oxygen, resulting in local consumptive hypoxia. Under this circumstance, hypoxia-induced hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is necessary for neutrophil survival and macrophage phagocytosis. Neutrophils generate excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) that aggravate the host immune response [7]. ROS further contribute to the generation of NETs, which entrap virus and prevent their dissemination into the circulation. Macrophages infiltrating in the lung have been shown to clear virus by phagocytosis. The main symptoms manifest as fever, dry cough, myalgias, fatigue and headache at this stage. However, recent studies have revealed that some COVID-19 patients in the early phase prior to admission show elevated D-dimer levels and microthrombi formation (Table 1). This phase involving viral invasion and replication is characterized by minor symptoms and shows an antiviral response mainly triggered by NETs and macrophages.

Table 1.

Laboratory values and major mechanisms involved in different stages in COVID-19

| The disease stage | Laboratory parameters | Dominant mechanisms involved |

|---|---|---|

| Initial phase | D-dimer levels ↑ | Virus invasion |

| a. SARS-CoV-2 invasion into the lung mediated by TMPRSS2 initiating viral spike protein binding with ACE2. | ||

| b. NE increasing viral infectivity by spike protein cleavage. | ||

| Antiviral response | ||

| a. Local consumptive hypoxia induced by infiltrated neutrophil and other immune cells. | ||

| b. ROS release, NETs generation and macrophages infiltrating. | ||

| Pulmonary phase | Inflammatory markers | Lung inflammation and injury |

| Interleukin-1 ↑ | a. Histones facilitate inflammation by activating TLR2, TLR4 and TLR9. | |

| Interleukin-6 ↑ | b. NETs enhance inflammatory response by ERK/MAPK. | |

| TNF-α ↑ | c. NETs facilitate the inflammatory response by mediating complement activation. | |

| C reactive protein ↑ | The role of hypoxia in the pulmonary phase | |

| Ferritin ↑ | a. Hypoxia upregulates TF expression in phagocytes to promote thrombosis by activated EGR-1. | |

| Coagulation markers | b. Hypoxia promotes inflammation by increased interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein. | |

| Prothrombin time ↑ | c. Inappropriate activation of HIF induces neutrophils persistence, resulting in delayed inflammation resolution and tissue damage. | |

| Fibrinogen ↑ | d. Upregulation of HIF-1α expression inhibits the recovery of damaged epithelial cell. | |

| FDPs ↑ | ||

| Platelet count ↓ | ||

| vWF ↑ | ||

| Antithrombin ↑ | ||

| D-dimer ↑ | ||

| Factor VIII ↑ | ||

| Systemic hyperinflammatory phase | Lymphocyte count ↓ | Hyperinflammatory state |

| D-dimers ↑ | NETs and pro-inflammatory substances released by macrophages constitutes a positive feedback loop, forming a cytokine storm. | |

| Soluble TM ↑ | Pulmonary pathophysiology | |

| Soluble P-selectin ↑ | Pulmonary hypertension, ECs damage and inflammation collectively are involved in the pathophysiology of lung. | |

| Soluble CD40 ligand ↑ | Thrombosis | |

| a. Activated platelets interact with neutrophils to promote thrombosis. | ||

| b. Histones mediate the mechanism for thrombosis by the upregulation of TF and PS expression. | ||

| c. Elevated levels of TF expression and PS exposure on ECs after treatment with NETs together enhance hypercoagulable state. | ||

| d. HIF2α induced by hypoxia mediates the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and microparticles release. | ||

| e. Exhausted plasmin affects thrombus formation by altered fibrinolytic function. | ||

| f. Inflammation induced by NETs and the release of cytokines results in high levels of FVIII and vWF: Ag and a secondary deficiency of ADAMTS13. | ||

| NETs are involved in ARDS and MOF. |

SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TMPRSS2: The transmembrane protease serine 2; ACE2: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; NETs: Neutrophil extracellular traps; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; FDPs: Fibrinogen degradation products; vWF: von Willebrand factor; TLR: Toll-like receptor; ERK/MAPK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase; EGR-1: Early growth response-1; HIF: Hypoxia inducible factor; TM: Thrombomodulin; TF: Tissue factor; PS: Phosphatidylserine; ECs: Endothelial cells; ADAMTS13: A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin motif repeats 13; ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome; MOF: Multiple organ failure; COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019.

Phase II: pulmonary phase

The second phase is mainly characterized by lung inflammation and injury. NET generation is mainly responsible for the inflammatory response of lung tissues. The components of NETs, extracellular cationic histones, exert cytotoxic activity to facilitate the generation of IL-1β and mediate pro-inflammatory effects by activating toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), TLR4, and TLR9 [8]. NETs enhance various cytokines production, including IL-1β and TNF-α by extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase activation to enhance inflammatory response [9]. Moreover, IL-1β and TNF-α, as the main activators, also induce increased IL-6 levels [10]. Additionally, NETs components can facilitate the inflammatory response by mediating complement activation, regarded as inflammasome activators and danger-associated molecular patterns [11]. NETs can induce tissue damage by extracellular exposure of DNA, granular proteins including myeloperoxidase and histone, leading to apoptosis and fibrotic processes [12,13]. Recent studies show that SARS-CoV-2 can directly stimulate neutrophils to release NETs dependent on ACE2 and serine protease activity axis, and NETs induce lung epithelial cell death [14]. NETs are involved in an inflammatory response and lung injury.

Hypoxemia, tachypnea, and breathlessness are commonly seen in this phase. Hypoxia upregulates tissue factor (TF) expression in phagocytes to promote thrombosis by activating early growth response-1 transcription factor [15]. Additionally, hypoxia promotes inflammation by increased IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) [16]. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is expressed on neutrophils and macrophages under hypoxic conditions. Inappropriate activation of HIF induces neutrophil persistence, resulting in delayed inflammation resolution and tissue damage [17]. Hypoxia is critical for determining lung epithelial cell fate and upregulation of HIF-1α expression inhibits the recovery of damaged epithelial cells.

In COVID-19 patients, extensively abnormal laboratory values involve increased inflammatory markers, including IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, ferritin, as well as coagulation abnormalities, consisting of D-dimer, prothrombin time (PT), fibrinogen, fibrinogen degradation products (FDPs), platelet count, von Willebrand factor (vWF), antithrombin (AT), and coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) (Table 2). The characteristic changes of coagulation values, D-dimer and FDP, fibrinogen and platelet count, indicate the activation of coagulation in response to the inflammation and virus infection [18] (Table 1).

Table 2.

COVID-19-associated coagulation

| Value | Direction of change | Comparator (case versus control) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-dimer | ↑ | ICU versus non-ICU | Patients with high D-dimer and high CRP have the greatest risk of adverse outcomes [49,50]. |

| Fibrinogen | ↑ | COVID-19 versus healthy control | The severity of COVID-19 was found significantly associated with significant increase of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, ferritin, fibrinogen [51]. |

| TAT | ↑ | COVID-19 versus healthy control | TAT was also found correlated with disease severity. Meanwhile, there was significant difference of TAT in the death and survival group [52]. |

| vWF antigen | ↑ | Severe versus non-severe | vWF: Ag is a relevant predictive factor for in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients [53]. |

| FVIII activity | ↑ | ICU versus non-ICU | High FVIII activity was observed in patients with COVID-19 who are admitted to the ICU [54]. |

| PAI-1 | ↑ | COVID-19 versus healthy control | Markedly elevated t-PA and PAI-1 levels were observed in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. High levels of t-PA and PAI-1 were associated with worse respiratory status [55]. |

| sP-selectin | ↑ | ICU versus non-ICU | Plasma concentrations of P-selectin are also significantly elevated in patients with COVID-19 who are admitted to the ICU [54]. |

| sTM | ↑ | ICU versus non-ICU | In patients, soluble thrombomodulin concentrations greater than 3.26 ng/mL were related to lower rates of hospital discharge [54]. |

| sCD40L | ↑ | ICU versus non-ICU | In COVID-19 patients, sCD40L levels were higher in cases requiring admission to intensive care unit [56]. |

Arrows indicate the direction of change (s = increase, ate the direction of change (sCOVID-19 with respect to a control group or reference range defined in the comparator column. ICU: intensive care unit; CRP: C reactive protein; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; TAT: thrombin-antithrombin; vWF: von Willebrand factor; PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; sP-selectin: soluble P-selectin; sTM: soluble thrombomodulin; sCD40L: soluble CD40 ligand.

Phase III: systemic hyperinflammatory state

In the third phase, as the inflammatory responses are further reinforced, more neutrophils recruited into inflamed lung tissue and releasing NETs, as well as impaired ability of macrophages to clear NETs together contribute to high levels of NETs [19]. The antibacterial peptides (LL-37) and myeloperoxidase of NETs cause chemotaxis of immune cells and polarize macrophages towards pro-inflammatory type 1 (M1) macrophages, which secrete pro-inflammatory substances to aggravate the inflammatory response and lung injury [20]. In addition, NETs trigger nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation and IL-1β release in macrophages by the TLR-4/TLR-9/nuclear factor-κB signal pathway [21]. Subsequently, substantial amounts of cytokines, in turn, contribute to NET generation. In summary, NETs, acting on macrophages, are related to increased pro-inflammatory cytokines, which contribute to the dysregulated NET formation. These NETs, in turn, promote the production of pro-inflammatory substances by macrophages, further forming a cytokine storm, which sustains an aberrant systemic inflammation. This phase is characterized by systemic thrombosis, hyperinflammatory state, ARDS and multiple organ failure (MOF).

Pulmonary pathophysiology

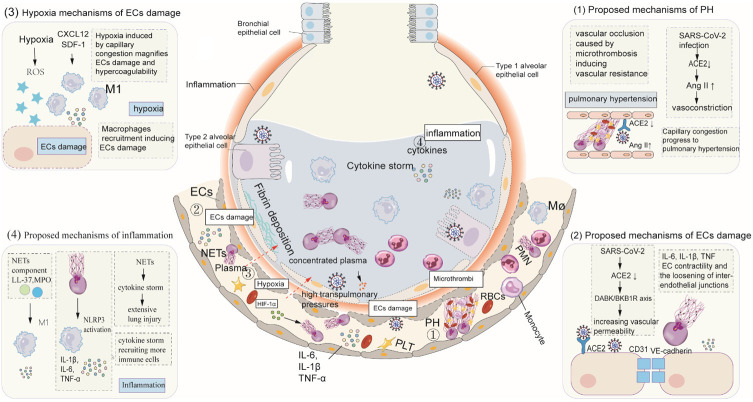

Pulmonary post-mortem studies of COVID-19 patients have shown capillary congestion, intra-alveolar edema, necrosis of pneumocytes, and type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia [22]. Capillary congestion can progress to pulmonary hypertension (PH). Additionally, other underlying mechanisms of PH in patients with COVID-19 exist. First, vascular occlusion resulting from microthrombi gives rise to significant increases in pulmonary vascular resistance, facilitating the formation of PH. Second, SARS-CoV-2 infection downregulates ACE2 expression, which increases angiotensin II (Ang II), further resulting in pulmonary vasoconstriction by binding with Angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1) and pulmonary hypertension. Extensive ECs damage has been observed in COVID-19 patients. In addition to SARS-CoV-2 direct damage, the downregulation of ACE2 expression results in activation of the des-Arg9 bradykinin/bradykinin receptor B1 axis, increasing vascular permeability. High cytokines levels, including IL-6, IL-1β, lead to increased ECs contractility and the relaxation of inter-endothelial junctions [23]. NETs decrease expression of the inter-cellular (junctional) proteins CD31 and VE-cadherin, which disturbs the integrity of the ECs monolayer. Profound hypoxia resulted from capillary congestion magnifies ECs damage, blood plasma into pulmonary alveolar, and hypercoagulability by increasing blood viscosity, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activating HIF-1α [24]. Hypoxia-induced ROS production directly leads to ECs injury. Additionally, the increase of chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1, CXCL12) induced by HIF-1α results in monocyte migration and recruitment to lung tissue by CXCR4 receptor [25]. Macrophages in lung tissues are polarized into M1 macrophages and extensively injure ECs by the release of proinflammatory cytokines. Due to widespread ECs injury, intravascular substances, consisting of plasma, fibrinogen, albumin and globulin, extrude into alveolar lumens at high pulmonary artery pressure. Alveolar spaces are often filled with plasma, aggravating the mismatch of ventilation and perfusion, which is a hallmark feature of COVID-19 ARDS. NETs, acting on macrophages, lead to excessive cytokine production and more immune cells recruited into the lungs, resulting in diffuse alveolar damage [26]. Owning to difficulty breathing and low blood oxygen saturation levels, patients with severe COVID-19 require mechanical ventilation to improve alveolar oxygenation. Mechanical ventilation takes away substantial water from the plasma in the alveoli, leading to highly concentrated plasma and gelatinous protein formation. Subsequently, plasma constantly intrudes into the alveolar lumens. The pathogenetic condition of COVID-19 patients sharply deteriorates, associated with high mortality (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The role of NETs in the pathophysiology of ARDS with COVID-19 patients. (1) Proposed mechanisms of PH. Capillary congestion and significant increases in pulmonary vascular resistance induced by microthrombi can progress to pulmonary hypertension. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 infection downregulates the expression of ACE2, which increases angiotensin II, resulting in pulmonary vasoconstriction by binding with Angiotensin II type 1 receptor and pulmonary hypertension. (2) Proposed mechanisms of EC damage. In addition to SARS-CoV-2 direct damage, the downregulation of ACE2 expression results in activation of the DABK/BKB1R axis, increasing vascular permeability. High cytokine levels, including IL-6, and IL-1β, result in increased ECs contractility and the relaxation of inter-endothelial junctions. NETs induce decreased expression of inter-cellular (junctional) proteins CD31 and VE-cadherin, which disturb the integrity of the ECs monolayer. (3) Hypoxia mechanisms of ECs damage. Profound hypoxia resulted from capillary congestion magnifies ECs damage and hypercoagulability by increasing blood viscosity, ROS and activating HIF-1α. Hypoxia-induced ROS production directly contributes to EC injury. Additionally, HIF-1-induced increase of SDF-1 (CXCL12) contributes to monocytes migration by binding with CXCR4 receptor. Migrating monocytes can be polarized into M1 macrophages and release substantial amounts of cytokines to injure ECs. (4) Proposed mechanisms of inflammation. NETs, acting on macrophages, lead to excessive cytokine production and more immune cell recruitment into the lungs, resulting in hyperinflammatory states and even diffuse alveolar damage. Abbreviations: PH: pulmonary hypertension; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; Ang II: Angiotensin II; IL: interleukin; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; ECs: endothelial cells; DABK/ BKB1R axis: des-Arg9 bradykinin/bradykinin receptor B1 axis; HIF-1α: Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; NETs: neutrophil extracellular traps; CXCL: CXCL: chemokines IL; SDF-1: stromal cell-derived factor-1; LL-37, the antimicrobial peptide LL-37; MPO, myeloperoxidase; M1, M1 macrophages; NLRP3, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; PLT: Platelet; RBC: Red blood cell PMN: Polymorphonuclear neutrophil.

Thrombosis

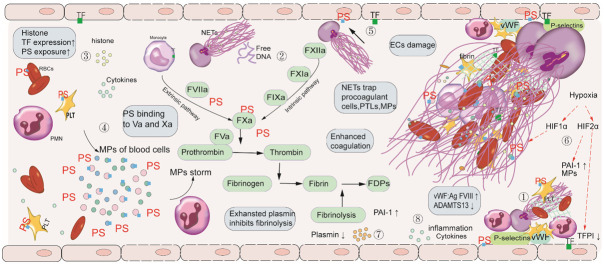

Massive thrombosis is commonly found in this phase. Numbers of SARS-CoV-2 are released into the blood, then enter endothelial cells as the disease progresses. Proinflammatory cytokines released by activated blood cells and NETs together lead to extensive EC damage. Damaged ECs further result in the disruption of vessel wall integrity and slow blood flow by regulating vasoconstriction. Substantial amounts of blood cells and coagulation factors accumulate in the site of injured vessel. Cytokines-induced increased expression of P-selectins and von Willebrand factor on damaged ECs recruits and adheres leukocytes (mainly neutrophils) and platelets (PLTs). Furthermore, in severe inflammatory states, a secondary deficiency of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin motif repeats 13 (ADAMTS13) leads to reduced vWF cleavage and pathologically increases platelet-vessel wall interaction [27]. Microparticles (MPs) of activated PLTs, expressing high mobility group box 1, result in the formation of NETs by autophagy pathway, which entrap more PLTs and red blood cells (RBCs) [28]. Antimicrobial peptides LL-37 of NETs in turn promote platelet activation in a P-selectin-dependent manner, therefore form a vicious circle and further exacerbate the formation of thrombosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanism of NETs in thrombosis in COVID-19. (1) Increased expression of P-selectins and vWF, recruits and adheres to leukocytes (mainly neutrophils) and PLTs. Activated platelets interact with neutrophils to promote thrombus formation. (2) DNA by contact activation initiates the generation of fibrin (3) Histones mediate the mechanism for thrombosis through the upregulation of TF and PS expression. (4) Cytokines lead to the release of considerable amounts of MP, released from apoptosis of blood cells, promoting thrombus formation by PS exposure. (5) Elevated levels of TF expression and PS exposure on ECs after treatment with NETs together enhance hypercoagulable state. (6) Hypoxia-induced HIF1α promotes thrombosis by NET generation. HIF2α induced by hypoxia mediates the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and microparticles (MP) release. HIF2α also reduces expression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) on ECs. (7) Exhausted plasmin affects thrombus formation by altered fibrinolytic function. (8) Inflammation induced by NETs and the release of cytokines results in high levels of FVIII and vWF: Ag and a secondary deficiency of ADAMTS13. Defective ADAMTS13 leads to reduced vWF cleavage and enhances platelet-rich thrombus. Abbreviations: NETs: Neutrophil Extracellular Traps; COVID19: coronavirus disease 2019; ECs: endothelial cells; NETs: neutrophil extracellular traps; RBCs: red blood cells; TF: tissue factor; PS: phosphatidylserine; PT: prothrombin; PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; MPs: microparticles; PMN: polymorphonuclear neutrophils; HIF1α: hypoxia inducible factor-1α; vWF: von Willebrand factor; PLTs: platelets; ADAMTS13: A disintegrin-like, and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13.

DNA and histones, the main components of NETs, also enhance thrombus formation. DNA induces the formation of factor XIIa (FXIIa),then activates pre-kallikrein (PK) and factor XI (FXI), and ultimately initiates the generation of fibrin. Histones upregulate TF expression on ECs and monocytes to a level that triggers the production of plasma thrombin. Histones also induce phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure on PLTs and RBCs, thereby supporting assembly of the prothrombinase complex [29] (Figure 2).

Microparticles (MPs) are membrane-bound vesicles released after activation or apoptosis of blood cells, ECs, RBCs, and tumor cells. Cytokine storm leads to apoptosis of the blood cells (mainly PLTs, RBCs, and white blood cells), which release amounts of MPs and subsequently form the MP storm [30]. PS exposure on MPs enhances the binding and formation of FVIIa, FIXa, FXa, and thrombin by interaction with the Gla domains within the proteins and facilitates FVaXa and TF activity [31]. MPs attach to NETs, which provide a scaffold for MP coagulation, and the PS on MP binding with FV and FVIII, thereby leading to systemic thrombosis [32] (Figure 2).

The levels of TF expression and PS exposure on ECs after treatment with NETs are increased. Moreover, ECs cultured under high concentration of NETs can induce increased FXa complex and thrombin [33]. PS exposure on ECs provides platforms for the binding of clotting factors, further promoting thrombus by the intrinsic pathway. Tissue factor (TF) on EC binding to factor VIIa (FVIIa) initiates coagulation by the extrinsic pathway. The role of PS may have an advantage over TF in COVID-19 associated thrombosis. First, PS exposure is observed on all activated or apoptotic cells, while TF is mainly expressed on monocytes and ECs in the pathologic thrombotic process [34]. Secondly, severe damage of monocytes and ECs, and even apoptosis in a hyperinflammatory state result in decreased synthesis and expression of TF, and PS exposure on blood cells is unaffected and conversely increased. Thirdly, most TF is in the inactive state and requires PS-dependent decryption [35]. Additionally, EC inflammation triggered by NETs accompanies high levels of FVIII and vWF: Ag, which is related to thrombosis [24] (Figure 2).

Hypoxia increases the transcription of HIF1α and HIF2α subunits. The underlying mechanisms of HIFs in thrombus formation are multiple. First, HIF1α upregulates neutrophil stress-response protein REDD1, leading to NET release by autophagy-associated signaling pathways. NETs provide a scaffold for immune cells, coagulation factors, and MPs, accordingly enhancing thrombosis. Secondly, platelet HIF2α mediates the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and MP release [36]. The levels of PAI-1 are elevated, which marks decreased fibrinolytic activity in COVID-19 patients, leading to the imbalance of coagulation and fibrinolysis. Thirdly, on ECs, hypoxia-mediated HIF2α reduces expression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), which suppresses the extrinsic pathway of coagulation, resulting in pro-thrombotic phenotype [37] (Figure 2).

In addition to the coagulation system, an exhausted fibrinolytic system may affect thrombus formation. Fibrinolytic system is initiated by frequent thrombus formation and markedly increased plasmin, which dissolves fibrin-rich blood clots, then generates high levels of D-dimer, indicating a high fibrinolytic state. Subsequently, excessive consumption of plasmin leads to decreased fibrinolytic function. This explains why hyperfibrinolysis characterized by elevated D-dimer and fibrinolysis inhibition with elevated PAI-1 simultaneously exist.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

The presentation of severe COVID-19 is progressive hypoxemia and dyspnea, and often patients require mechanical ventilation support in this phase. Pulmonary computed tomography (CT) shows that the surrounding ground-glass opacity in lung tissue conforms to the Berlin criteria of ARDS in COVID-19 patients [38]. The pathophysiology of ARDS induced by SARS-CoV-2 is similar to that of severe community-acquired pneumonia induced by other bacteria or viruses [25]. Various animal models of the agents responsible for ARDS agrees that neutrophils have a central role in early innate immune response, and excessive neutrophils accumulate in the pulmonary capillaries and alveoli of ARDS patients, which has been shown in recent autopsy reports of COVID-19 patients. Neutrophils have been closely correlated with the development of ARDS, and NETs are regarded as primary effector cells of tissue injury [4]. Cytokine storm induced by NETs and macrophages, leads to excessive cytokines and more immune cell recruitment into the lungs, resulting in diffuse alveolar damage and even ARDS [26].

Multiple organ failure

Systemic hyperinflammation induces the increase of NETs. Circulating histones have been shown to cause alveolar capillary occlusion, toxicity in lung tissue, and activated coagulation cascade, which ultimately leads to lung injury and MOF [39]. As symptoms of SARS-CoV-2-induced sepsis patients progress, high levels of cf-DNA result in MOF [40]. Massive cytokines induce extensive EC damage and dysfunction, further aggravating thrombus formation. Extensive thrombosis spreads throughout the body and induces an inadequate blood supply to vital organs, resulting in both hypoxemia and hypoglycemia and subsequent damage and failure of multiple organs.

A marked decrease of lymphocytes in COVID-19 patients is observed in this phase, suggesting a decline in adaptive immunity. Lymphopenia is a significant factor correlated with the severity and mortality of the patients [41]. In addition to lymphocyte death caused by the interaction of activated Fas and Fas ligand and the TNF-related apoptosis-induced ligand axis, which initiates or promotes the death of lymphocytes. Lymphocyte infection with SARS-CoV-2 results in decreased lymphocytes [42]. Lymphocyte entrapping by NETs can also account for lymphopenia [43]. The ECs adhere to blood cells and clotting factors, which cause uncontrolled clotting. In response to extensive thrombosis, the body undertakes measures to dissolve fibrin-rich blood clots, explaining why increased fibrin degradation products (D-dimers) predict poor prognosis in COVID-19 patients [44]. Additionally, EC damage induced by inflammation results in pathologic release of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (u-PA), which is also the reason for increased D-dimer. The levels of soluble thrombomodulin, soluble P-selectin, as well as soluble CD40 ligand are elevated, which mark EC injury and PLTs activation [24] (Table 1).

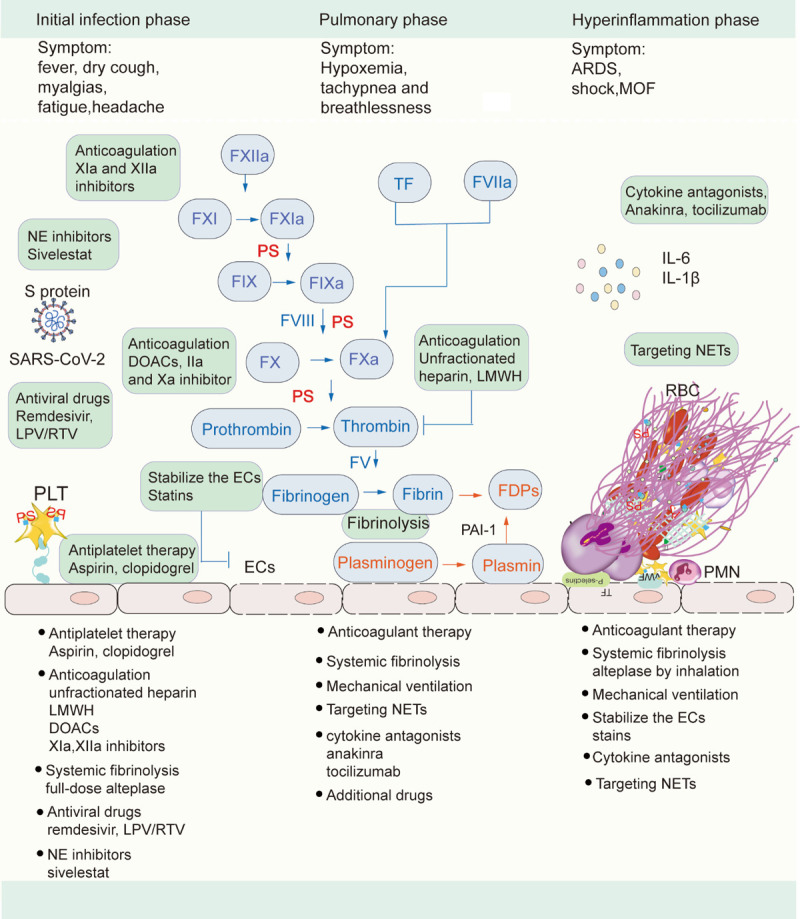

Theoretical treatment strategy

Owning to microthrombi in the initial infection phase, early effective antithrombotic therapy combined with full-dose alteplase for systemic fibrinolysis can maintain blood flow patency, which is the key to inhibit severe diseases caused by SARS-CoV-2 and improve prognosis. Antithrombotic therapy consists of antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel) and anticoagulation, including unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH), direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), XIa, and XIIa inhibitors. Heparin not only exhibits anticoagulant actions by the inhibition of thrombin production, but also exerts an anti-inflammatory effect by the downregulation of IL-6, and thus unfractionated heparin or LMWH remains the best choice of anticoagulant for admitted patients [45,46]. DOACs, including IIa and Xa inhibitor, in addition to the antithrombotic effect, also attenuate the inflammatory response, which shows beneficial effects for COVID-19 patients. FXII and FXI are located at the initiation of the clotting cascade and critical for the propagation and stabilization of thrombus but less important for hemostasis. Therefore, FXIIa and FXIa inhibitors decrease the consumption of coagulation factors and the levels of D-dimer, as well as not increase bleeding risk. Treatment with antiviral drugs can inhibit viral production in this stage, including remdesivir, lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/RTV). NE is involved in S protein cleavage and virus invasion, and treatment with sivelestat is beneficial for COVID-19 patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Treatment strategies of different phases in COVID-19. Abbreviations: NE: neutrophil elastase; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; S protein: spike protein; vWF, von Willebrand factor; PLTs, platelets; RBCs: red blood cell; PMN: polymorphonuclear neutrophils; PS, phosphatidylserine; FDPs: fibrin degradation products; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; DOACs: direct oral anticoagulants; LPV/RTV, Lopinavir/ritonavir; ECs, endothelial cells; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; MOF, multiple organ failure.

In the second phase, the continuation of the antithrombotic therapy with fibrinolytic therapy is necessary for COVID-19 hospitalized patients to improve prognosis. Treatment with mechanical ventilation to improve hypoxia is a vital step in this stage, which suppresses hypoxia-related thrombosis, inflammation, and tissue damage, delaying disease progression. The targeting therapy of NETs is considered to be an appropriate therapeutic method to suppress NET-mediated inflammation, cytokines release, and lung injury during the second phase. Early use of cytokine antagonists, including anakinra (an IL-1 receptor antagonist) and tocilizumab (a humanized monoclonal anti-IL-6 receptor antibody), can reduce infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lungs, which is the key to cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients [47]. However, therapeutic strategies targeting the hyperactive cytokines with cytokine antagonists must be balanced with sustaining enough inflammatory response for pathogen clearance. Additional drugs that attenuate inflammation can also be used at this stage (Figure 3).

Given that thrombotic complications are central determinants of the high mortality rate in COVID-19, antithrombotic therapy with thrombolytic therapy is of critical importance in the hyperinflammation phase [48]. Owning to fibrin deposition in the alveoli seriously disturbing gas exchange, COVID-19 patients use alteplase by inhalation to improve respiratory symptoms and hemodynamics. COVID-19 patients still require mechanical ventilation in this stage. The emerging view of the important role of ECs indicates that the therapy to improve ECs function, including statins, can slow down its progression and reduce mortality in COVID-19. Cytokine antagonists, including IL-1β, IL-6, are regarded as an attractive therapeutic strategy for targeting cytokine storm. It is necessary to target NETs to improve outcomes of COVID-19 patients (Figure 3).

Severe and critical COVID-19 patients are more likely to develop thrombosis after discharge. We recommend to receive long-term oral anticoagulants apixaban. Moreover, patients are required to regularly monitor thrombosis and spontaneous bleeding tendency.

Conclusion

NETs are involved in pulmonary pathophysiology, inflammation, and thrombus formation of COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 infection causes the damage of alveolar epithelial cells, which leads to neutrophil infiltration and NETs formation in the lungs. Pulmonary hypertension, extensive EC damage, fibrin deposition, and activated immune cells are involved in pulmonary pathophysiologic processes and result in sharp deterioration. NETs provide a scaffold for coagulation factors, blood cells, and high amounts of MPs described as microparticles storm, promoting thrombosis. Based on disease characteristics and mechanisms of different stages, we provide corresponding antithrombotic therapy, systemic fibrinolysis, cytokine antagonists, and targeting NET therapy. We highlight the importance of early antithrombotic therapy with systemic fibrinolysis, which dissolves intravascular microthrombi, alleviating and arresting the progression of the disease in the early stage. Meanwhile, NETs not only predict the severity of COVID-19, but also serve as a therapeutic target for COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yue Zhang for the data collection. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81670128 and 81873433).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1β

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- MOF

multiple organ failure

- ECs

endothelial cells

- NETs

neutrophil extracellular traps

- S protein

Spike protein

- ACE2

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- TMPRSS2

transmembrane protease serine 2

- NE

neutrophil elastase

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducible factor-1α

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor-1

- CXCL

chemokines IL

- TLR2

toll-like receptor 2

- TF

tissue factor

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- PT

prothrombin time

- FDPs

fibrinogen degradation products

- vWF

von Willebrand factor

- AT

antithrombin

- FVIII

factor VIII

- NLRP3

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- AT1

Angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- PLTs

platelets

- ADAMTS13

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin motif repeats 13

- MPs

microparticles

- RBCs

red blood cells

- FXIIa

active factor XIIa

- PK

pre-kallikrein

- FXI

factor XI

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- FVIIa

active factor VIIa

- MPs

microparticles

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- TFPI

tissue factor pathway inhibitor

- u-PA

urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- DOACs

direct oral anticoagulants

- LPV/RTV

lopinavir/ritonavir

References

- 1.Jose RJ, Manuel A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e46–e47. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuo Y, Yalavarthi S, Shi H, Gockman K, Zuo M, Madison JA, Blair C, Weber A, Barnes BJ, Egeblad M, Woods RJ, Kanthi Y, Knight JS. Neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight. 2020;5:e138999. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.138999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romagnoli S, Peris A, De Gaudio AR, Geppetti P. SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: from the bench to the bedside. Physiol Rev. 2020;100:1455–1466. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta P, Porter JC, Manson JJ, Isaacs JD, Openshaw PJM, McInnes IB, Summers C, Chambers RC. Therapeutic blockade of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in COVID-19-associated hyperinflammation: challenges and opportunities. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:822–830. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30267-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thierry AR. Anti-protease treatments targeting plasmin(ogen) and neutrophil elastase may be beneficial in fighting COVID-19. Physiol Rev. 2020;100:1597–1598. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomar B, Anders HJ, Desai J, Mulay SR. Neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps drive necroinflammation in COVID-19. Cells. 2020;9:1383. doi: 10.3390/cells9061383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laforge M, Elbim C, Frère C, Hémadi M, Massaad C, Nuss P, Benoliel JJ, Becker C. Tissue damage from neutrophil-induced oxidative stress in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:515–516. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0407-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasetty G, Papareddy P, Bhongir RKV, Ali MN, Mori M, Wygrecka M, Erjefält JS, Hultgårdh-Nilsson A, Palmberg L, Herwald H, Egesten A. Osteopontin protects against lung injury caused by extracellular histones. Mucosal Immunol. 2019;12:39–50. doi: 10.1038/s41385-018-0079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinallo V, Marafini I, Di Fusco D, Laudisi F, Franzè E, Di Grazia A, Figliuzzi MM, Caprioli F, Stolfi C, Monteleone I, Monteleone G. Neutrophil extracellular traps sustain inflammatory signals in ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:772–784. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pons S, Fodil S, Azoulay E, Zafrani L. The vascular endothelium: the cornerstone of organ dysfunction in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Crit Care. 2020;24:353. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fousert E, Toes R, Desai J. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) take the central stage in driving autoimmune responses. Cells. 2020;9:915. doi: 10.3390/cells9040915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thammavongsa V, Missiakas DM, Schneewind O. Staphylococcus aureus degrades neutrophil extracellular traps to promote immune cell death. Science. 2013;342:863–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1242255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolhnikoff M, Duarte-Neto AN, de Almeida Monteiro RA, da Silva LFF, de Oliveira EP, Saldiva PHN, Mauad T, Negri EM. Pathological evidence of pulmonary thrombotic phenomena in severe COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1517–1519. doi: 10.1111/jth.14844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veras FP, Pontelli MC, Silva CM, Toller-Kawahisa JE, de Lima M, Nascimento DC, Schneider AH, Caetité D, Tavares LA, Paiva IM, Rosales R, Colón D, Martins R, Castro IA, Almeida GM, Lopes MIF, Benatti MN, Bonjorno LP, Giannini MC, Luppino-Assad R, Almeida SL, Vilar F, Santana R, Bollela VR, Auxiliadora-Martins M, Borges M, Miranda CH, Pazin-Filho A, da Silva LLP, Cunha LD, Zamboni DS, Dal-Pizzol F, Leiria LO, Siyuan L, Batah S, Fabro A, Mauad T, Dolhnikoff M, Duarte-Neto A, Saldiva P, Cunha TM, Alves-Filho JC, Arruda E, Louzada-Junior P, Oliveira RD, Cunha FQ. SARS-CoV-2-triggered neutrophil extracellular traps mediate COVID-19 pathology. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20201129. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thachil J. Hypoxia-An overlooked trigger for thrombosis in COVID-19 and other critically ill patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:3109–3110. doi: 10.1111/jth.15029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Li Y, Atakan MM, Kuang J, Hu Y, Bishop DJ, Yan X. The molecular adaptive responses of skeletal muscle to high-intensity exercise/training and hypoxia. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9:656. doi: 10.3390/antiox9080656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts ER, Walmsley SR. Inflammation and hypoxia: HIF and PHD isoform selectivity. Trends Mol Med. 2019;25:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fei Y, Tang N, Liu H, Cao W. Coagulation dysfunction. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144:1223–1229. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0324-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grégoire M, Uhel F, Lesouhaitier M, Gacouin A, Guirriec M, Mourcin F. Impaired efferocytosis and neutrophil extracellular trap clearance by macrophages in ARDS. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1702590. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02590-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song C, Li H, Li Y, Dai M, Zhang L, Liu S, Tan H, Deng P, Liu J, Mao Z, Li Q, Su X, Long Y, Lin F, Zeng Y, Fan Y, Luo B, Hu C, Pan P. NETs promote ALI/ARDS inflammation by regulating alveolar macrophage polarization. Exp Cell Res. 2019;382:111486. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu D, Yang P, Gao M, Yu T, Shi Y, Zhang M, Yao M, Liu Y, Zhang X. NLRP3 activation induced by neutrophil extracellular traps sustains inflammatory response in the diabetic wound. Clin Sci (Lond) 2019;133:565–582. doi: 10.1042/CS20180600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carsana L, Sonzogni A, Nasr A, Rossi RS, Pellegrinelli A, Zerbi P, Rech R, Colombo R, Antinori S, Corbellino M, Galli M, Catena E, Tosoni A, Gianatti A, Nebuloni M. Pulmonary post-mortem findings in a series of COVID-19 cases from northern Italy: a two-centre descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30434-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teuwen LA, Geldhof V, Pasut A, Carmeliet P. COVID-19: the vasculature unleashed. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:389–391. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0343-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard-Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Fagot Gandet F, Fafi-Kremer S, Castelain V, Schneider F, Grunebaum L, Anglés-Cano E, Sattler L, Mertes PM, Meziani F. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown JM. Radiation damage to tumor vasculature initiates a program that promotes tumor recurrences. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108:734–744. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z, Yang X, Zhou Y, Sun J, Liu X, Zhang J, Mei X, Zhong J, Zhao J, Ran P. COVID-19 severity correlates with weaker T cell immunity, hypercytokinemia and lung epithelium injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:606–610. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1701LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levi M, Thachil J, Iba T, Levy JH. Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e438–e440. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maugeri N, Capobianco A, Rovere-Querini P, Ramirez GA, Tombetti E, Valle PD, Monno A, D’Alberti V, Gasparri AM, Franchini S, D’Angelo A, Bianchi ME, Manfredi AA. Platelet microparticles sustain autophagy-associated activation of neutrophils in systemic sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaao3089. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noubouossie DF, Reeves BN, Strahl BD, Key NS. Neutrophils: back in the thrombosis spotlight. Blood. 2019;133:2186–2197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-10-862243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Li B, Hu TL, Li T, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Yu M, Wang C, Hou L, Dong Z, Hu TS, Novakovic VA, Shi J. Increased phosphatidylserine on blood cells in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Dent Res. 2019;98:763–771. doi: 10.1177/0022034519843106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owens AP, Mackman N. Microparticles in hemostasis and thrombosis. Circ Res. 2011;108:1284–1297. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Luo L, Braun OÖ, Westman J, Madhi R, Herwald H, Mörgelin M, Thorlacius H. Neutrophil extracellular trap-microparticle complexes enhance thrombin generation via the intrinsic pathway of coagulation in mice. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4020. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22156-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou P, Li T, Jin J, Liu Y, Li B, Sun Q, Tian J, Zhao H, Liu Z, Ma S, Zhang S, Novakovic VA, Shi J, Hu S. Interactions between neutrophil extracellular traps and activated platelets enhance procoagulant activity in acute stroke patients with ICA occlusion. EBioMedicine. 2020;53:102671. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson SP, Darbousset R, Schoenwaelder SM. Thromboinflammation: challenges of therapeutically targeting coagulation and other host defense mechanisms. Blood. 2019;133:906–918. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-882993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ansari SA, Pendurthi UR, Sen P, Rao LV. The role of putative phosphatidylserine-interactive residues of tissue factor on its coagulant activity at the cell surface. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaurasia SN, Kushwaha G, Kulkarni PP, Mallick RL, Latheef NA, Mishra JK, Dash D. Platelet HIF-2α promotes thrombogenicity through PAI-1 synthesis and extracellular vesicle release. Haematologica. 2019;104:2482–2492. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.217463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee YY, Park HH, Park W, Kim H, Jang JG, Hong KS, Lee JY, Seo HS, Na DH, Kim TH, Choy YB, Ahn JH, Lee W, Park CG. Long-acting nanoparticulate DNase-1 for effective suppression of SARS-CoV-2-mediated neutrophil activities and cytokine storm. Biomaterials. 2021;267:120389. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cui XY, Skretting G, Tinholt M, Stavik B, Dahm AEA, Sahlberg KK, Kanse S, Iversen N, Sandset PM. A novel hypoxia response element regulates oxygen-related repression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in the breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Thromb Res. 2017;157:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, Vanstapel A, Werlein C, Stark H, Tzankov A, Li WW, Li VW, Mentzer SJ, Jonigk D. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biron BM, Chung CS, Chen Y, Wilson Z, Fallon EA, Reichner JS, Ayala A. PAD4 deficiency leads to decreased organ dysfunction and improved survival in a dual insult model of hemorrhagic shock and sepsis. J Immunol. 2018;200:1817–1828. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang JW, Yang L, Luo RG, Xu JF. Corticosteroid administration for viral pneumonia: COVID-19 and beyond. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1171–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, Liu L, Zhang D, Xu J, Dai H, Tang N, Su X, Cao B. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses. Lancet. 2020;395:1517–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30920-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sivanandham R, Brocca-Cofano E, Krampe N, Falwell E, Venkatraman SMK, Ribeiro RM, Apetrei C, Pandrea I. Neutrophil extracellular trap production contributes to pathogenesis in SIV-infected nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:5178–5183. doi: 10.1172/JCI99420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matacic C. Blood vessel injury may spur disease’s fatal second phase. Science. 2020;368:1039–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.368.6495.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sardu C, Gambardella J, Morelli MB, Wang X, Marfella R, Santulli G. Hypertension, thrombosis, kidney failure, and diabetes: is COVID-19 an endothelial disease? A comprehensive evaluation of clinical and basic evidence. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1417. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Atallah B, Mallah SI, AlMahmeed W. Anticoagulation in COVID-19. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020;6:260–261. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the ‘Cytokine Storm’ in COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;80:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McFadyen JD, Stevens H, Peter K. The emerging threat of (micro) thrombosis in COVID-19 and its therapeutic implications. Circ Res. 2020;127:571–587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Samkari H, Gupta S, Leaf RK, Wang W, Rosovsky RP, Brenner SK, Hayek SS, Berlin H, Kapoor R, Shaefi S, Melamed ML, Sutherland A, Radbel J, Green A, Garibaldi BT, Srivastava A, Leonberg-Yoo A, Shehata AM, Flythe JE, Rashidi A, Goyal N, Chan L, Mathews KS, Hedayati SS, Dy R, Toth-Manikowski SM, Zhang J, Mallappallil M, Redfern RE, Bansal AD, Short SAP, Vangel MG, Admon AJ, Semler MW, Bauer KA, Hernán MA, Leaf DE STOP-COVID Investigators. Thrombosis, bleeding, and the observational effect of early therapeutic anticoagulation on survival in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:622–632. doi: 10.7326/M20-6739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smilowitz NR, Kunichoff D, Garshick M, Shah B, Pillinger M, Hochman JS, Berger JS. C-reactive protein and clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Eur Heart J. 2021:ehaa1103. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marfia G, Navone S, Guarnaccia L, Campanella R, Mondoni M, Locatelli M, Barassi A, Fontana L, Palumbo F, Garzia E, Ciniglio Appiani G, Chiumello D, Miozzo M, Centanni S, Riboni L. Decreased serum level of sphingosine-1-phosphate: a novel predictor of clinical severity in COVID-19. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;13:e13424. doi: 10.15252/emmm.202013424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin X, Duan Y, Bao T, Gu J, Chen Y, Li Y, Mao S, Chen Y, Xie W. The values of coagulation function in COVID-19 patients. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0241329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Philippe A, Chocron R, Gendron N, Bory O, Beauvais A, Peron N, Khider L, Guerin CL, Goudot G, Levasseur F, Peronino C, Duchemin J, Brichet J, Sourdeau E, Desvard F, Bertil S, Pene F, Cheurfa C, Szwebel TA, Planquette B, Rivet N, Jourdi G, Hauw-Berlemont C, Hermann B, Gaussem P, Mirault T, Terrier B, Sanchez O, Diehl JL, Fontenay M, Smadja DM. Circulating von willebrand factor and high molecular weight multimers as markers of endothelial injury predict COVID-19 in-hospital mortality. Angiogenesis. 2021;24:505–517. doi: 10.1007/s10456-020-09762-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goshua G, Pine AB, Meizlish ML, Chang CH, Zhang H, Bahel P, Baluha A, Bar N, Bona RD, Burns AJ, Dela Cruz CS, Dumont A, Halene S, Hwa J, Koff J, Menninger H, Neparidze N, Price C, Siner JM, Tormey C, Rinder HM, Chun HJ, Lee AI. Endotheliopathy in COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: evidence from a single-centre, cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e575–e582. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuo Y, Warnock M, Harbaugh A, Yalavarthi S, Gockman K, Zuo M, Madison JA, Knight JS, Kanthi Y, Lawrence DA. Plasma tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1580. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80010-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campo G, Contoli M, Fogagnolo A, Vieceli Dalla Sega F, Zucchetti O, Ronzoni L, Verri M, Fortini F, Pavasini R, Morandi L, Biscaglia S, Di Ienno L, D’Aniello E, Manfrini M, Zoppellari R, Rizzo P, Ferrari R, Volta CA, Papi A, Spadaro S. Over time relationship between platelet reactivity, myocardial injury and mortality in patients with SARS-CoV-2-associated respiratory failure. Platelets. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2020.1852543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]