Abstract

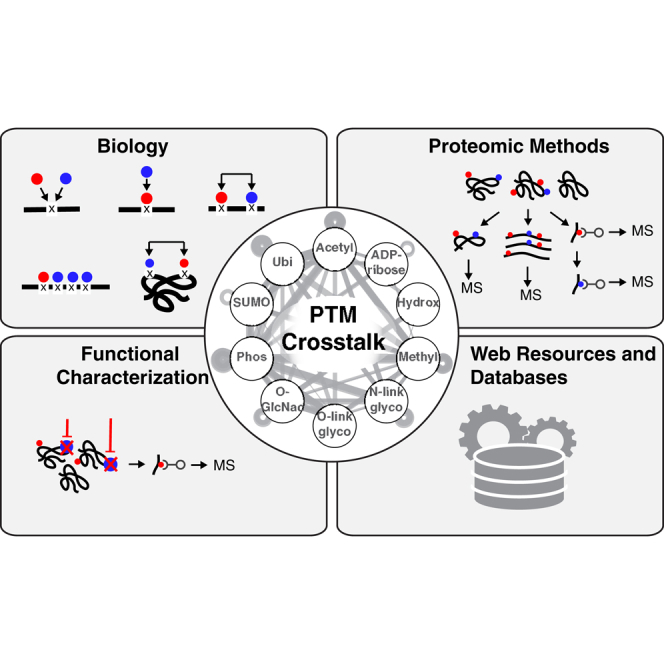

Post-translational modification (PTM) of proteins allows cells to regulate protein functions, transduce signals and respond to perturbations. PTMs expand protein functionality and diversity, which leads to increased proteome complexity. PTM crosstalk describes the combinatorial action of multiple PTMs on the same or on different proteins for higher order regulation. Here we review how recent advances in proteomic technologies, mass spectrometry instrumentation, and bioinformatics spurred the proteome-wide identification of PTM crosstalk through measurements of PTM sites. We provide an overview of the basic modes of PTM crosstalk, the proteomic methods to elucidate PTM crosstalk, and approaches that can inform about the functional consequences of PTM crosstalk.

Keywords: post-translational modification, proteomics, crosstalk, mass spectrometry

Abbreviations: IMAC, immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography; MS, mass spectrometry; PTM, post-translational modification

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Description of basic modules and different modes of PTM crosstalk.

-

•

Overview of current proteomic methods to identify and infer PTM crosstalk.

-

•

Discussion of large-scale approaches to characterize functional PTM crosstalk.

-

•

Future directions and potential proteomic methods for elucidating PTM crosstalk.

In Brief

We provide an overview of current experimental and computational proteomic methods, as well as a perspective on emerging technologies to study PTM crosstalk.

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) of proteins at one or more amino acid positions are covalent modifications that occur during (co-translational) or after (post-translational) a protein has been translated. In eukaryotic cells, PTMs have been described on 15 of the 20 proteinogenic amino acids side chains as well as the protein backbone. They come in a great chemical diversity with >300 modifications known (1). Most commonly studied PTMs are phosphorylation, glycosylation, addition of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins, acylations, and methylation. PTMs can be reversible and dynamic, and they have the ability to change protein function. Different PTMs lend themselves to different aspects of biology. For example, reversible phosphorylation underlies many signal transduction pathways, glycosylation modulates the stability and structure of many membrane and secreted proteins, ubiquitination targets proteins for degradation, several lysine PTMs including acetylation and succinylation are sensitive to metabolic state and can regulate transcription, and diverse modifications converge on histone N-terminal tails to control chromatin state and gene expression. Mass-spectrometry-based proteomics has led to the identification of tens of thousands of PTM sites across the proteome. For the example of phosphorylation, it was found that the majority of the human proteome has the potential to undergo modification (2), global phosphorylation states can change within seconds to minutes (3), and phosphorylation is virtually involved in all cellular processes. However, PTMs do not exist in isolation. Proteins are modified at multiple sites by various PTMs simultaneously. The combinatorial action of multiple PTMs on the same or on different proteins is termed PTM crosstalk. PTM crosstalk adds an additional layer of functional protein regulation and leads to an expansion in information content of the proteome. In this review, we touch on the underlying cellular machinery that enables PTM crosstalk and the functional concepts of PTM crosstalk and then focus in detail on technologies that are within reach to study PTM crosstalk proteome-wide.

The PTM Machinery

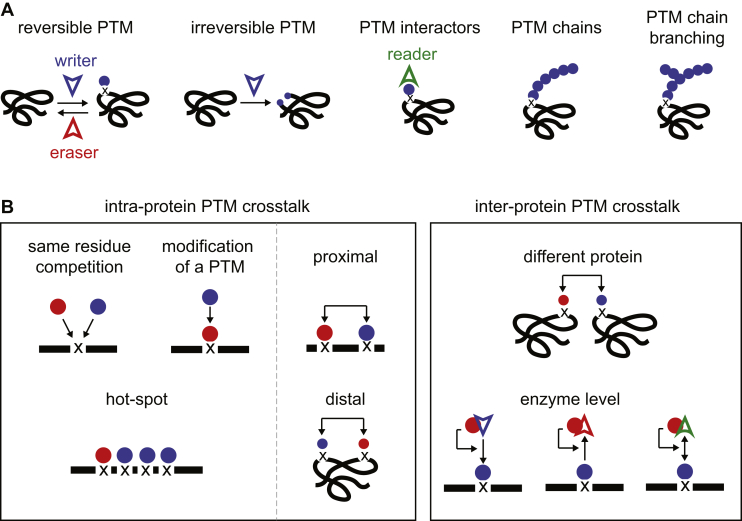

Central to PTM crosstalk is the molecular machinery that controls PTMs and defines their cellular functions. As has been conceptualized previously (4, 5), the PTM machinery consists of “writers”, “erasers”, and “readers” (Fig. 1A). Writers, e.g., kinases, ubiquitin ligases, and acetyltransferases, enzymatically catalyze the transfer of a modifying group onto protein substrates. These modifying groups are usually transferred onto proteins as a single entity, but in certain cases they can also be written as linear or branched polymers (Fig. 1A). Conversely, erasers, e.g., phosphatases, deubiquitinases, and deacetylases, confer reversibility by catalyzing the removal of these modifications from protein substrates. In specific cases, PTMs can also occur non-enzymatically through the action of reactive species, changes in metabolite concentration, or pH shifts (6). Some PTMs are non-reversible, for example, protein carbonylation or proteolytic cleavages of the protein backbone. Readers of PTMs include a broad set of protein domains with high affinity for proteins with specific PTMs and are often the proteins that transduce a PTM-dependent function. PTM writers and erasers require specific enzymatic activities. In cases, such as kinases, where the enzymatic domain is well conserved, can be identified using sequence alignment and their activity validated by enzymatic assays (7). PTM readers, however, constitute a variety of protein domains and are thus more difficult to systematically identify. Typically, writers and erasers also have reader domains that regulate enzymatic activity and determine substrate specificity. High-throughput proteomics methods have begun to map the substrates of PTM writers and erasers (8, 9, 10) as well as readers (11, 12). Future efforts to map the substrate specificity of writers and erasers, and to identify additional PTM readers and their targets, will be very important for a full understanding of PTM crosstalk mechanisms.

Fig. 1.

The Toolbox for PTM crosstalk.A, the PTM machinery includes proteins that write, erase, and read the PTM. PTMs come in reversible and non-reversible forms, as monomers, polymers, and branched polymers. B, different modes of PTM crosstalk are separated based on intra- or inter-protein crosstalk. Proteins are illustrated in black, different PTMs as blue and red circles, the modification site is depicted as “x.”

Intra- and Inter-Protein PTM Crosstalk

In this review, we define crosstalk between PTMs when one PTM directly influences the addition, removal, or function of another PTM. Previous reviews have further classified types of PTM crosstalk (5, 13, 14), highlighting diverse underlying mechanisms. We summarize these previous classifications by defining two broad categories of PTM crosstalk: intra- and inter-protein PTM crosstalk. In intra-protein PTM crosstalk, the modifications occur on the same protein, and in inter-protein PTM crosstalk, the modifications occur on separate proteins. As first articulated by Hunter, both types of PTM crosstalk can be either “positive” or “negative” (14), where a PTM either triggers or blocks the regulation of another PTM, respectively.

Both intra- and inter-protein PTM crosstalks can manifest in different ways, outlined in Figure 1B. Perhaps the most commonly observed mode of intra-protein PTM crosstalk is the interdependence of different modified residues in nearby sequence space. Classic examples of this are the histone H3 N-terminal modifications that regulate chromatin state (15), multisite phosphorylation of the C-terminal repeats of RNA polymerase II that regulates gene expression (16), processive phosphorylation by GSK3 (17), and “phosphodegrons” at PEST sequences, wherein phosphorylation promotes ubiquitination of a proximal lysine residue and subsequent degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (18). Proximal PTM crosstalk can be positive, e.g., ubiquitination that is dependent on proximal phosphorylation, sumoylation, or ADP-ribosylation (18, 19, 20), or negative, as when histone H3R2 dimethylation prevents H3K4 trimethylation (21, 22). In principle, intra-protein PTM crosstalk can also occur on residues that are distant in sequence but are structurally proximal or act allosterically. Another type of PTM crosstalk is direct competition, a form of negative crosstalk wherein two different modifications can occur on the same residue, and each modification inhibits the addition of the other. For example, O-GlcNAcylation on Ser16 of estrogen receptor β may protect from phosphorylation-mediated degradation, as mutation of Ser16 to a phosphomimetic caused increased turnover (23). In more complex cases, the modifying group can itself be modified. Polymeric PTMs such as poly-ubiquitination, glycosylation, and poly-ADP-ribosylation are common in biology, and the mechanisms regulating their specific branching structure are another form of PTM crosstalk, however, beyond the scope of this review (24, 25). PTMs themselves can also be modified by different PTMs. Notably, ubiquitin conjugated to target proteins can be acetylated and phosphorylated, affecting ubiquitin polymerization state and target protein specificity (26, 27, 28). In sum, intra-protein PTM crosstalk centers individual protein molecules as signaling hubs that integrate post-translational signals from multiple sources.

Many examples of inter-protein PTM crosstalk, where one PTM affects the regulation of a PTM on a different protein, have been known for decades. Protein kinases, which control phosphorylation on numerous downstream substrates, typically require phosphorylation of their activation loop for full activity. As regulation of kinase activity is a rich and well-trodden field, for this review, we will focus more on PTM crosstalk via direct modulation of enzyme activity that has been observed for different PTMs. For example, phosphorylation of certain E3 ligases can enhance or block ubiquitination of their protein targets (14). Inter-protein PTM crosstalk can also occur via regulating binding surfaces for modifying enzymes. For example, as was reviewed previously (13), formation of the kinetochore during mitosis, which is essential for chromosome segregation and avoiding aneuploidy, requires coordinated inter-protein PTM crosstalk to establish dynamic protein interaction surfaces. In sum, inter-protein PTM crosstalk is a complex and decentralized form of signal processing and is a critical and widespread aspect of biology.

Overall, intra- and inter-protein PTM crosstalks allow the cell rapid implementation of complex, integrating signaling processing modules in the form of switches and recognition motifs that can serve as logical gates in signaling networks.

Proteomic Methods to Identify PTM Crosstalk

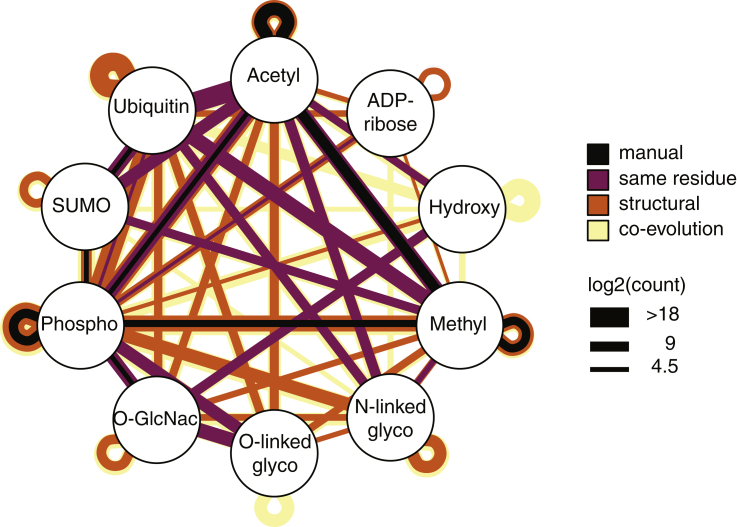

Traditionally, PTM crosstalk has been studied in a targeted manner on candidate cross-talking PTMs. Experiments involved biochemical in vitro reactions, genetic or chemical perturbations, and detection of PTM states by labeling the PTM (e.g., radioactive ATP in an in vitro kinase reaction) or by western blot or immunofluorescence using an antibody against the PTM. These experiments have uncovered numerous examples of biologically relevant PTM crosstalk. However, there is accumulating evidence that PTM crosstalks are widespread in the proteome. The PTMcode web resource (29) compiles ~200 manually validated examples of intra-protein PTM crosstalk in the human proteome among ten selected PTM types (Fig. 2). In addition, using over 1 million validated or predicted PTM sites in their database, they predict many more examples of potential PTM crosstalk based on evidence for same residue competition (~8500), structural distance (~18,100), and coevolution (~1,432,000) (Fig. 2). Mass-spectrometry-based proteomics allows the identification of thousands of PTMs at single amino acid resolution and their quantification across different proteomic states (30). For this reason, it is an ideal technology to explore PTM crosstalks at a proteomic scale. In the subsequent sections, we describe biochemical assays, sample preparation strategies, MS acquisitions methods, and computational approaches to systematically uncover PTM crosstalk proteome-wide (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Predicted PTM crosstalk. Network plot indicating experimentally measured and predicted intra-protein crosstalk of selected PTMs in humans based on data collected and computed by PTMcode2 (29). Nodes correspond to selected PTM types and edges represent their connectivity. Edge color is indicative of crosstalk evidence (manual identification, same residue, structural prediction, or coevolution), and weight of the edge corresponds to observed/predicted pairs. The plot visualizes the immense space of potential crosstalk between PTMs in contrast to the few experimentally observed connections.

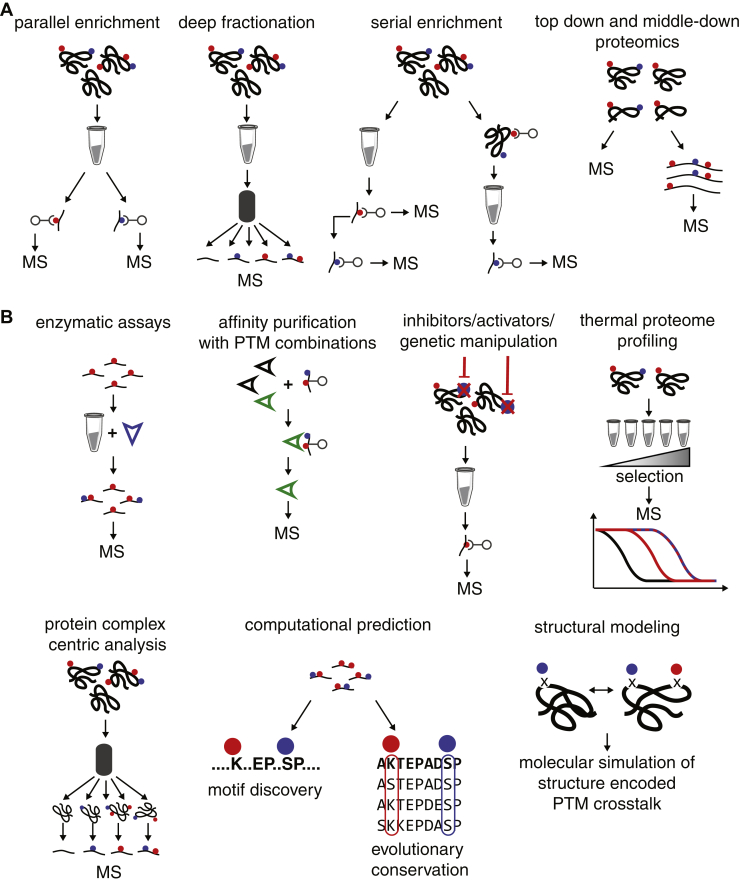

Fig. 3.

Proteomic methods to study PTM crosstalk.A, different approaches to measure PTMs and their potential interactions. Proteins are illustrated as black tangled lines, peptides are shorter linear black lines, different PTMs as blue and red circles. B, technologies to directly study PTM crosstalk and functional consequences of PTM crosstalk.

Parallel Analysis of Multiple PTMs

Arguably, the simplest approach to identify intra-protein PTM crosstalk involves the parallel analysis of multiple PTMs, where the enrichment for peptides containing each of the modifications can be conducted in parallel (31), sequentially (32, 33, 34), or simultaneously (35, 36) (Fig. 3A). Alternatively deep-fractionation methods have also yielded identification of many modified peptides (37) (Fig. 3A). While most experiments in this group were not designed to identify PTM crosstalks, the data can be inspected for co-occurrence of PTMs on the same peptide, PTMs targeting the same residue, and exclusion of PTMs nearby other PTMs as demonstrated in the case of GlcNAc and phosphorylation (34).

In fact, standard phosphoproteomic experiments already yield a large fraction of peptides containing two or three phosphosites allowing the study of their crosstalk (38). Efficient enrichment for one modification can also yield peptides harboring two chemically distinct modifications. For example, in a study of SUMO-modified proteins, Hendriks et al. (39) identified SUMO-modified peptides that also harbored one of phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, acetylation, arginine methylation, and lysine methylation modifications. Interestingly 9% of all SUMOylations occurred in close proximity to phosphorylation and numerous SUMOylations were fully dependent on prior phosphorylation. This approach also confirmed and further elucidated extensive hybrid-chain crosstalk within SUMO family members, ubiquitin, and NEDD8 (39).

Enrichment of Multiple Modified Peptides and Proteins

Methods have been designed to separate peptides containing two distinct modifications from peptides containing only one. For example, we used strong-cation exchange fractionation prior to enrichment with a di-glycyl antibody to separate peptides containing both ubiquitylation and phosphorylation sites from peptides containing either PTM alone and identified 437 comodified peptides.

The methods described above are constrained to modifications occurring in close sequence proximity, which can be identified in the same peptide. In order to detect co-occurring PTMs that are distant in sequence, a serial PTM enrichment approach can be applied, where enrichment of one PTM at the protein level is followed by enrichment of a second PTM at the peptide level (Fig. 3A). We have applied this approach to identify phosphosites that are unique to ubiquitinated protein forms in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (40). We enriched for ubiquitinated proteins using a His-tagged ubiquitin, ubiquitinated and nonubiquitinated protein fractions were trypsin-digested and further enriched for phosphopeptides and di-Gly peptides. We found that 36% of ubiquitinated proteins also contained at least one phosphorylated residue (321 ubiquitinated phosphoproteins).

Identification of Multiple Modified Peptides

Identification of peptides harboring multiple PTMs is required for several experimental approaches to study intra-protein PTM crosstalk described above. In protein sequence database searches of mass spectra PTMs are defined as variable modifications on the corresponding amino acids, and all possible forms of modified candidate peptides need to be considered to score a query spectrum. To obtain peptide identifications, scoring thresholds for peptide spectral matches with a defined false discovery rate (FDR) need to be computed, which can be done using target-decoy strategies (41). However, when this method is applied collectively across a dataset, the FDR may be different for unmodified, modified, and multiply modified peptides due to their different proportions in the protein sample, the different search space, and PTM-specific fragmentation patterns (42, 43). To improve the FDR accuracy, the FDR of modified peptides can be estimated separately, for example, by computing the relationship of the global FDR to that of the subgroup of PTM-containing peptides (42, 44). However, this strategy has not been widely applied yet.

One particularly challenging case is the identification and quantification of PTMs on histone peptides due to their high modification state and numerous isobaric forms. For this application specific software has been developed to differentiate and quantify histone peptides with different modification marks using, among other parameters, PTM retention time relationships (45).

Open Modification Searches

Identifying unknown or unexpected modifications on peptides in complex mixtures measured by MS is a nontrivial task, but required to unbiasedly discover single or even combinatorial modifications of a peptide. Because searching for many possible modifications is impractical using classical database searches, several approaches (46) and specialized computational tools have been developed that empower open modification searches for the comprehensive identification of modified peptides (47, 48, 49, 50, 51). Open search strategies allow large mass differences on the order of several hundreds of Dalton between unmodified peptide sequences and experimentally observed precursors to identify a modified spectrum. The observed delta mass of the modified versus the unmodified precursor and fragment ions allows the identification of PTMs, chemical modifications, amino acid substitutions, and cleavage variants of known masses. By applying an open search approach including unknown masses of ±500 Da to proteome-wide data of HEK293 cells, Chick et al. (46) achieved a 46% increase in identifications. About 20% of the additional modified peptides consisted of potentially biological relevant modifications, and among these they were able to identify peptides harboring multiple phosphorylations and glycosylations. Development of novel open search software has advanced to a level where these tools are practical to use. For example, MSFragger allows fast and sensitive open modifications searches using a fragment-ion indexing method (49) and a suite of accompanying tools that allow localization of the modification (52) and comprehensive modification annotation (53) all integrated into a graphical user interface. Applying MSFragger to affinity purification experiments enabled deep exploration of protein modification states of enriched proteins (49) and correlation of different modifications across many conditions in large datasets (53). Applying open modification searches to deep-fractionated samples or PTM enriched samples has the potential to uncover peptides that contain additional unknown modifications that would otherwise remain unidentified. Open modification searches should be considered for studies aiming at discovering novel layers of PTM crosstalk and can be applied in combination with several of the sample preparation approaches discussed above.

Middle-Down Proteomics

Middle-down proteomics is a discipline that aims at analysing long peptides (~25–100 amino acid residues). In this special application of bottom-up proteomics, different digestion strategies are employed to obtain longer peptides than those formed by trypsin digestion (54) (Fig. 3A). This has the advantage of increasing the probability to detect multiple co-occurring PTMs in one peptide thereby allowing measurement of medium-range intra-protein PTM crosstalk. Middle-down proteomics has extensively been applied to characterize and catalog interdependent and mutually exclusive PTMs in heavily modified proteins such as histones (55, 56, 57). Furthermore, middle-down proteomics has been used to characterize ubiquitin chain topology and branching (58, 59). So far middle-down proteomics has been mainly applied to study PTM crosstalk on purified protein samples or on a few selected PTMs; however, applications with deep proteome coverage are within reach. Middle-down approaches are compatible with several of the methods we discuss in this review and can potentially lead to broader coverage of co-occurring PTMs.

Top-Down Proteomics

In top-down proteomics, whole proteins are measured by mass spectrometry, overcoming the challenge of inferring protein identity from peptide fragments and providing proteoform resolution (60, 61) (Fig. 3A). Direct analysis of proteins can reveal intra-protein PTM crosstalk by identifying combinations of PTMs regardless of their sequence proximity, as well as PTM hierarchies (62). For example, top-down investigations of cardiac troponin revealed the identity and order of co-occurring phosphorylation sites (63). More recently, top-down approaches have been applied to map proteoform landscapes of cardiac sarcomeric proteins and their differential phosphorylation in patient samples (64).

Native top-down proteomics goes a step further and aims at preserving noncovalent protein interactions. This allows the analysis of protein complexes and their PTMs, thereby enabling the study of inter-protein PTM crosstalk (65). Indeed, a recent study applied native top-down mass spectrometry to quantify the relative abundance of histone isoforms and their respective PTM-proteoforms from endogenous nucleosome preparations in a single mass spectrum (66). While limited by low throughput, low proteome coverage, and protein-specific sample preparation considerations, top-down methods are highly complementary to bottom-up approaches and allow for complex patterns of intra- and inter-protein PTM co-occurrence to be measured for proteins and complexes of interest.

High-Throughput Functional Characterization of PTM Crosstalk

The approaches described above allow proteome-wide identification of PTMs that co-occur in the proteome, co-occur on the same protein, or co-occur in spatial proximity and thereby allow us to make predictions and inferences about potential PTM crosstalk. This is valuable information and will inform biological research; however, in most cases this is not direct evidence for PTM crosstalk. To obtain functional evidence of PTM crosstalk proteome-wide, more elaborate analyses need to be employed that capture direct interactions of PTMs or between PTMs and the PTM machinery. In the following section, we will discuss approaches that allow assessment of combinatorial PTM action (Fig. 3B).

Enzymatic Assays

One classical way of looking at PTM crosstalk is by performing enzymatic in vitro assays on purified proteins to uncover the influence of an already present PTM on a second PTM attachment reaction. The specificity for GSK3 was discovered using this type of experiment, where in vitro phosphorylation of a synthetic substrate peptide showed that GSK3 prefers substrates with a priming phosphorylation at the +4 position (17). Similar in vitro reactions can also be performed on the whole proteome, on an enriched or synthesized peptide library using MS to track attachment of the second PTM. These measurements can provide site specific information on how reaction kinetics and substrate specificity for the attachment of a PTM are influenced by an already present PTM. This approach has been used to investigate the influence of protein phosphorylation on subsequent O-GlcNAcylation of the same substrate (67). For this, a complex mixture of phosphopeptides was obtained by enrichment from a human cell line tryptic digest. The phosphopeptide mixture was subsequently incubated with recombinant O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and samples were analyzed by MS for O-GlcNAcylation sites. It was found that generally phosphorylation hampers O-GlcNAcylation at nearby sites. The authors ultimately defined a negative crosstalk motif (pS/pT)P(T/V/A)(gS/gT), where phosphorylation of three amino acid residues upstream from the putative O-GlcNAcylation site significantly inhibits modification by OGT.

Moving forward, this approach could be expanded to different PTM combinations to determine spatially close positive and negative intra-protein PTM crosstalk. Care needs to be taken, since in vitro PTM reactions are often unspecific due to the lack of the cellular context. The availability of recombinant enzymes in combination with highly efficient PTM enrichment strategies and amino acid resolution achieved with MS makes this approach an interesting avenue for mechanistic studies of interplay between PTMs.

Identification of Readers of Combinatorial PTMs

In several cases it was found that PTMs need to be present in specific combinations in order for a reader protein to bind and initiate a biological response. For example, a dual histone H3 modification mark consisting of Ser10 phosphorylation and Lys14 acetylation is needed to recruit the transcription machinery for expression of the p21 gene (68). To address combinatorial dependencies of PTMs to recruit protein complexes, several techniques have been developed that employ quantitative affinity purification MS. Some of the initial methods used a synthetic bait peptide with defined combinations of PTMs to pull down interacting proteins that are specific to the PTM combination (69, 70). This approach has been extended and adapted to identify readers of PTM combinations in peptide libraries (e.g., a 5000-member, PTM-randomized combinatorial histone H3 N-terminus peptide library) (71) and higher-order structures (72). Overall this approach is broadly applicable, relatively easy to adapt, and has proven powerful to determine the functionality of co-occurring PTM marks, mainly on proteins and protein domains that are known to act as protein interaction hot spots.

Biological Perturbation of PTM Writers and Erasers

Genetic or chemical perturbations targeting the machinery of a specific PTM can be used to modulate the state of that PTM; and subsequent readout of a different PTM provides insight in crosstalk of the two PTM types. This strategy has been applied by upregulating O-GlcNAcylation levels in human cells by either overexpressing O-GlcNAc transferase or inhibiting O-GlcNac hydrolase, and subsequently measuring changes in global phosphorylation levels using phosphoproteomics. Many O-GlcNAcylation sites were occupying previously phosphorylated sites or located in close proximity to them, underscoring the reciprocal crosstalk between these two PTMs (67, 73).

Another approach employed the genome-reduced bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae and genetically deleted its only two protein kinases together with its unique protein phosphatase or its two putative N-acetyltransferases (74). The authors then measured proteome-wide effects on protein abundance, phosphorylation, and lysine acetylation. Phosphorylation as well as acetylation levels were affected when the machinery for the other PTM was absent confirming broad and interdependent post-transcriptional crosstalk of the two PTMs (74). Targeted biological perturbations in combination with the proteomic methods described before offer many possibilities to dissect interaction between PTMs and the PTM machinery. The approaches described above could also be used to identify novel cases of inter-protein PTM crosstalk, if modifications to known writers or erasers are discovered, which may regulate their activity and help to explain other changes to PTM levels in the same dataset.

Integrating Evolutionary and Structural Data

As described above, MS/MS-based proteomics has provided a wealth of data on individual and co-occurring PTMs, yet leveraging this data to assess proteome-wide PTM crosstalk remains a challenge. One strategy that has been employed with some success involves integrating data from different sources. Prior studies have analyzed PTM measurements from large-scale MS/MS experiments alongside protein sequence conservation and structural information (75, 76, 77). This work revealed that coevolution of PTM sites within the same protein is especially common between residues in close sequence and spatial proximity and that spans a range of cellular functions (78, 79, 80). Subsequent analysis identified a set of short linear motifs that may be important for regulating intra-protein PTM crosstalk (81). A more recent analysis of PTM hotspots on protein domains identified conserved phosphorylation clusters enriched near interaction interfaces and catalytic residues (82). Large-scale efforts to map PTM sites across different species can lead to a phylogenetic understanding of PTM sites and types, such as their origin and evolutionary trajectories (83). Elucidating the coevolution of protein sequences at PTM sites and for the corresponding PTM machinery can reveal functional dependencies and shed light on PTM crosstalk mechanisms (79). For these approaches to be successful, we need to increase the phylogenetic coverage of the species studied.

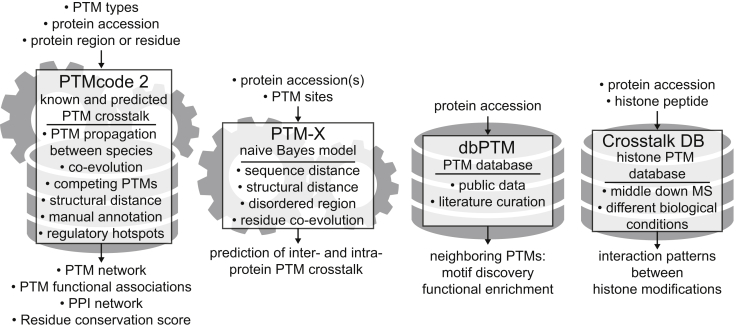

Web Resources and Databases

The accumulation of extensive PTM proteomic datasets has provided the opportunity to integrate the data in interactive databases, develop tools to compute and classify functional association between different PTMs, and predict crosstalk (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Web resources and databases to study PTM crosstalk. The PTMcode2, PTM-X, dbPTM, and CrosstalkDB are described. Illustration outlines type and form of input query, underlying algorithm or type of database and expected output.

Minguez et al. developed the PTM code database (https://ptmcode.embl.de) (29, 84), which aggregates experimentally verified PTMs from a variety of public databases. In the second and newest version of PTM code, 300,000 experimentally detected PTMs of 69 types from 19 different eukaryotic species were integrated together with evolutionary, structural, and protein–protein interaction data (29). To consolidate knowledge and minimize missing values, PTM sites were propagated across species where possible, which expanded the dataset to over 1.3 million PTMs. From this large resource, the authors make proteome-wide predictions of PTM crosstalk between modified residues that exhibit evolutionary coconservation and/or proximity in physical space (29). In addition, this resource can be used to predict PTM sites involved with regulating previously characterized protein–protein interactions.

Another resource, the PTM-X web server (http://bioinfo.bjmu.edu.cn/ptm-x/), aims at predicting intra- and inter-PTM crosstalk (85). PTM-X was trained on different features extracted from literature curated data for 193 PTM crosstalk pairs in 77 human proteins to predict intra-protein PTM crosstalk and on 199 PTM crosstalk pairs in 82 pair of human proteins to predict inter-protein PTM crosstalk (85). On the PTM-X web server, PTM sites can be queried and predictive scores for crosstalk obtained.

DbPTM (http://dbptm.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/index.php) is an integrated database that aims at bringing together many databases and resources containing experimentally verified and predicted PTMs resulting in hundreds of thousands PTM sites (86). DbPTM takes a stand on PTM crosstalk by summarizing neighboring PTMs in a specified protein sequence window length and subjects them to motif discovery and functional enrichment analysis.

CrosstalkDB (http://crosstalkdb.bmb.sdu.dk) is a small database of middle-down experiments on histones. It allows the user to explore histone modification dynamics over several biological conditions and visualizes codependent as well as mutually exclusive histone marks (55, 87).

Proteome-wide analysis of PTM measurements in conjunction with structural and evolutionary data is a powerful way to generate hypotheses about the existence and function of inter- and intra-protein PTM crosstalk. For example, one recent study integrated results from PTMcode, DbPTM, as well as other repositories of PTM, protein–protein interaction, and disease variant data to analyze predicted PTM crosstalk events on sirtuin-interacting proteins (88). Extensive datasets of isolated PTM exist and can be combined and integrated; however, bigger datasets of experimentally validated inter- and intra-protein PTM crosstalk are highly demanded to generate more sophisticated models and achieve higher prediction power for PTM crosstalk.

Discussion

Proteomic technologies have allowed the identification of hundreds of PTMs collectively targeting hundreds of thousands of sites in the proteome of diverse organisms. The proteomic approaches described here allow to measure and quantify PTMs that co-occur in the proteome or on the same protein. Measurement of co-occurring PTMs is informative and might hint at PTM interplay; however, localization of PTMs to the same protein typically does not provide enough evidence of functional crosstalk. Several approaches have been developed to bridge the gap between PTM co-occurrence and PTM crosstalk by perturbing one type of PTM and measuring the effect on another. These functional assays are crucial to uncover PTM crosstalk as an additional layer of proteome regulation.

Beyond the methods that have already been applied to identify PTM crosstalk, there are two areas of proteomics that we think are poised to increase our knowledge of crosstalks. The first area is quantitative (PTM) proteomics in multiperturbation experiments. As we increase complexity of our experiments, including tens to hundreds of biological conditions or perturbations, it becomes increasingly feasible to correlate the abundance profiles of distinct PTMs on a protein to identify intra-protein crosstalk by coregulation (40). These experiments can be further extended with measurements of protein abundance, protein subcellular localization, protein structural properties, gene expression, or metabolic fluxes to assess the function of the PTM or the PTM crosstalk.

The second area is the analysis of protein complexes using affinity purification, BioID, cross-linking, or size-exclusion chromatography followed by mass spectrometry (89, 90) Systematic profiling of PTM states of proteins within protein complexes or cellular structures will allow identification of codependent or mutually exclusive PTMs that may reveal inter- and intra-protein crosstalk that shape complex assembly and composition.

Methods, data, and analysis tools are now available to study PTM biology proteome-wide. Innovative ways to combine these approaches will reveal the various facets of PTM crosstalk.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all past and current members of the Villén lab for useful discussions. We would also like to thank Jimmy Eng and members of the Noble lab for discussions on FDR for samples containing (hyper)modified peptides.

Funding and additional information

The Villen lab is supported by NIH grants R35GM119536, R01AG056359, R01NS098329, and RM1HG010461; Human Frontiers Science Program grant RGP0034/2018; and a research program grant from the W. M. Keck Foundation. M. L. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation (P400PB_194379). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

M. L., S. W. E., and J. V. writing—original draft.

Footnotes

Present address for Samuel W. Entwisle: Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

References

- 1.Walsh C.T., Garneau-Tsodikova S., Gatto G.J. Protein posttranslational modifications: The chemistry of proteome diversifications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2005;44:7342–7372. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma K., D’Souza R.C.J., Tyanova S., Schaab C., Wiśniewski J.R., Cox J., Mann M. Ultradeep human phosphoproteome reveals a distinct regulatory nature of Tyr and Ser/Thr-based signaling. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1583–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humphrey S.J., Azimifar S.B., Mann M. High-throughput phosphoproteomics reveals in vivo insulin signaling dynamics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:990–995. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim W.A., Pawson T. Phosphotyrosine signaling: Evolving a new cellular communication system. Cell. 2010;142:661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venne A.S., Kollipara L., Zahedi R.P. The next level of complexity: Crosstalk of posttranslational modifications. Proteomics. 2014;14:513–524. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201300344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harmel R., Fiedler D. Features and regulation of non-enzymatic post-translational modifications. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018;14:244–252. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manning G., Whyte D.B., Martinez R., Hunter T., Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodenmiller B., Wanka S., Kraft C., Urban J., Campbell D., Pedrioli P.G., Gerrits B., Picotti P., Lam H., Vitek O., Brusniak M.Y., Roschitzki B., Zhang C., Shokat K.M., Schlapbach R. Phosphoproteomic analysis reveals interconnected system-wide responses to perturbations of kinases and phosphatases in yeast. Sci. Signal. 2010;3 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hornbeck P.V., Kornhauser J.M., Tkachev S., Zhang B., Skrzypek E., Murray B., Latham V., Sullivan M. PhosphoSitePlus: A comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D261–D270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ochoa D., Jonikas M., Lawrence R.T., El Debs B., Selkrig J., Typas A., Villén J., Santos S.D., Beltrao P. An atlas of human kinase regulation. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2016;12:888. doi: 10.15252/msb.20167295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu B.A., Jablonowski K., Shah E.E., Engelmann B.W., Jones R.B., Nash P.D. SH2 domains recognize contextual peptide sequence information to determine selectivity. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2010;9:2391–2404. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.001586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundby A., Franciosa G., Emdal K.B., Refsgaard J.C., Gnosa S.P., Bekker-Jensen D.B., Secher A., Maurya S.R., Paul I., Mendez B.L., Kelstrup C.D., Francavilla C., Kveiborg M., Montoya G., Jensen L.J. Oncogenic mutations rewire signaling pathways by switching protein recruitment to phosphotyrosine sites. Cell. 2019;179:543–560.e26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuijpers S.A.G., Vertegaal A.C.O. Guiding mitotic progression by crosstalk between post-translational modifications. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2018;43:251–268. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter T. The age of crosstalk: Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and beyond. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y., Garcia B.A. Comprehensive catalog of currently documented histone modifications. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015;7 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a025064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venkat Ramani M.K., Yang W., Irani S., Zhang Y. Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication—crosstalk of post-translational modifications on the RNA polymerase II. J. Mol. Biol. 2021;433:166912. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiol C.J., Mahrenholz A.M., Wang Y., Roeske R.W., Roach P.J. Formation of protein kinase recognition sites by covalent modification of the substrate. Molecular mechanism for the synergistic action of casein kinase II and glycogen synthase kinase 3. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:14042–14048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rechsteiner M., Rogers S.W. PEST sequences and regulation by proteolysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996;21:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang H.C., Lee Y.-I., Shin J.-H., Andrabi S.A., Chi Z., Gagne J.-P., Lee Y., Ko H.S., Lee B.D., Poirier G.G., Dawson V.L., Dawson T.M. Iduna is a poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR)-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase that regulates DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:14103–14108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108799108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prudden J., Pebernard S., Raffa G., Slavin D.A., Perry J.J.P., Tainer J.A., McGowan C.H., Boddy M.N. SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases in genome stability. EMBO J. 2007;26:4089–4101. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guccione E., Bassi C., Casadio F., Martinato F., Cesaroni M., Schuchlautz H., Lüscher B., Amati B. Methylation of histone H3R2 by PRMT6 and H3K4 by an MLL complex are mutually exclusive. Nature. 2007;449:933–937. doi: 10.1038/nature06166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirmizis A., Santos-Rosa H., Penkett C.J., Singer M.A., Vermeulen M., Mann M., Bähler J., Green R.D., Kouzarides T. Arginine methylation at histone H3R2 controls deposition of H3K4 trimethylation. Nature. 2007;449:928–932. doi: 10.1038/nature06160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng X., Hart G.W. Alternative O-glycosylation/O-phosphorylation of serine-16 in murine estrogen receptor beta: Post-translational regulation of turnover and transactivation activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10570–10575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010411200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aberle L., Krüger A., Reber J.M., Lippmann M., Hufnagel M., Schmalz M., Trussina I.R.E.A., Schlesiger S., Zubel T., Schütz K., Marx A., Hartwig A., Ferrando-May E., Bürkle A., Mangerich A. PARP1 catalytic variants reveal branching and chain length-specific functions of poly(ADP-ribose) in cellular physiology and stress response. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:10015–10033. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.French M.E., Koehler C.F., Hunter T. Emerging functions of branched ubiquitin chains. Cell Discov. 2021;7:6. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-00237-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohtake F., Saeki Y., Sakamoto K., Ohtake K., Nishikawa H., Tsuchiya H., Ohta T., Tanaka K., Kanno J. Ubiquitin acetylation inhibits polyubiquitin chain elongation. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:192–201. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song L., Luo Z.-Q. Post-translational regulation of ubiquitin signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2019;218:1776–1786. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201902074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swaney D.L., Rodríguez-Mias R.A., Villén J. Phosphorylation of ubiquitin at Ser65 affects its polymerization, targets, and proteome-wide turnover. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:1131–1144. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minguez P., Letunic I., Parca L., Garcia-Alonso L., Dopazo J., Huerta-Cepas J., Bork P. PTMcode v2: A resource for functional associations of post-translational modifications within and between proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D494–D502. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leutert M., Rodríguez-Mias R.A., Fukuda N.K., Villén J. R2–P2 rapid-robotic phosphoproteomics enables multidimensional cell signaling studies. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2019;15 doi: 10.15252/msb.20199021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Budzik J.M., Swaney D.L., Jimenez-Morales D., Johnson J.R., Garelis N.E., Repasy T., Roberts A.W., Popov L.M., Parry T.J., Pratt D., Ideker T., Krogan N.J., Cox J.S. Dynamic post-translational modification profiling of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected primary macrophages. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.51461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andaluz Aguilar H., Iliuk A.B., Chen I.-H., Tao W.A. Sequential phosphoproteomics and N-glycoproteomics of plasma-derived extracellular vesicles. Nat. Protoc. 2020;15:161–180. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0260-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mertins P., Qiao J.W., Patel J., Udeshi N.D., Clauser K.R., Mani D.R., Burgess M.W., Gillette M.A., Jaffe J.D., Carr S.A. Integrated proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications by serial enrichment. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:634–637. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trinidad J.C., Barkan D.T., Gulledge B.F., Thalhammer A., Sali A., Schoepfer R., Burlingame A.L. Global identification and characterization of both O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation at the murine synapse. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2012;11:215–229. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.018366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basisty N., Meyer J.G., Wei L., Gibson B.W., Schilling B. Simultaneous quantification of the acetylome and succinylome by ‘one-pot’ affinity enrichment. Proteomics. 2018;18:1800123. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201800123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmisano G., Parker B.L., Engholm-Keller K., Lendal S.E., Kulej K., Schulz M., Schwämmle V., Graham M.E., Saxtorph H., Cordwell S.J., Larsen M.R. A novel method for the simultaneous enrichment, identification, and quantification of phosphopeptides and sialylated glycopeptides applied to a temporal profile of mouse brain development. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2012;11:1191–1202. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.017509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bekker-Jensen D.B., Kelstrup C.D., Batth T.S., Larsen S.C., Haldrup C., Bramsen J.B., Sørensen K.D., Høyer S., Ørntoft T.F., Andersen C.L., Nielsen M.L., Olsen J.V. An optimized shotgun strategy for the rapid generation of comprehensive human proteomes. Cell Syst. 2017;4:587–599.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villén J., Beausoleil S.A., Gerber S.A., Gygi S.P. Large-scale phosphorylation analysis of mouse liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:1488–1493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609836104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hendriks I.A., Lyon D., Young C., Jensen L.J., Vertegaal A.C.O., Nielsen M.L. Site-specific mapping of the human SUMO proteome reveals co-modification with phosphorylation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:325–336. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swaney D.L., Beltrao P., Starita L., Guo A., Rush J., Fields S., Krogan N.J., Villén J. Global analysis of phosphorylation and ubiquitylation cross-talk in protein degradation. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi H., Nesvizhskii A.I. False discovery rates and related statistical concepts in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:47–50. doi: 10.1021/pr700747q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu Y., Qian X. Transferred subgroup false discovery rate for rare post-translational modifications detected by mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2014;13:1359–1368. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O113.030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marx H., Lemeer S., Schliep J.E., Matheron L., Mohammed S., Cox J., Mann M., Heck A.J.R., Kuster B. A large synthetic peptide and phosphopeptide reference library for mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:557–564. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yi X., Gong F., Fu Y. Transfer posterior error probability estimation for peptide identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2020;21:173. doi: 10.1186/s12859-020-3485-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan Z.-F., Sidoli S., Marchione D.M., Simithy J., Janssen K.A., Szurgot M.R., Garcia B.A. EpiProfile 2.0: A computational platform for processing epi-proteomics mass spectrometry data. J. Proteome Res. 2018;17:2533–2541. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chick J.M., Kolippakkam D., Nusinow D.P., Zhai B., Rad R., Huttlin E.L., Gygi S.P. A mass-tolerant database search identifies a large proportion of unassigned spectra in shotgun proteomics as modified peptides. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:743–749. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bittremieux W., Meysman P., Noble W.S., Laukens K. Fast open modification spectral library searching through approximate nearest neighbor indexing. J. Proteome Res. 2018;17:3463–3474. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Devabhaktuni A., Lin S., Zhang L., Swaminathan K., Gonzalez C.G., Olsson N., Pearlman S.M., Rawson K., Elias J.E. TagGraph reveals vast protein modification landscapes from large tandem mass spectrometry datasets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:469–479. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0067-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kong A.T., Leprevost F.V., Avtonomov D.M., Mellacheruvu D., Nesvizhskii A.I. MSFragger: Ultrafast and comprehensive peptide identification in mass spectrometry–based proteomics. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:513–520. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Na S., Bandeira N., Paek E. Fast multi-blind modification search through tandem mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2012;11 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010199. M111.010199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solntsev S.K., Shortreed M.R., Frey B.L., Smith L.M. Enhanced global post-translational modification discovery with MetaMorpheus. J. Proteome Res. 2018;17:1844–1851. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu F., Teo G.C., Kong A.T., Haynes S.E., Avtonomov D.M., Geiszler D.J., Nesvizhskii A.I. Identification of modified peptides using localization-aware open search. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4065. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17921-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geiszler D.J., Kong A.T., Avtonomov D.M., Yu F., Leprevost F.D.V., Nesvizhskii A.I. PTM-Shepherd: Analysis and summarization of post-translational and chemical modifications from open search results. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2021;20:100018. doi: 10.1074/mcp.TIR120.002216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cristobal A., Marino F., Post H., van den Toorn H.W.P., Mohammed S., Heck A.J.R. Toward an optimized workflow for middle-down proteomics. Anal. Chem. 2017;89:3318–3325. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schwämmle V., Sidoli S., Ruminowicz C., Wu X., Lee C.-F., Helin K., Jensen O.N. Systems level analysis of histone H3 post-translational modifications (PTMs) reveals features of PTM crosstalk in chromatin regulation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2016;15:2715–2729. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.054460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sidoli S., Garcia B.A. Middle-down proteomics: A still unexploited resource for chromatin biology. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 2017;14:617–626. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2017.1345632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sidoli S., Kori Y., Lopes M., Yuan Z.-F., Kim H.J., Kulej K., Janssen K.A., Agosto L.M., Cunha J.P.C.D., Andrews A.J., Garcia B.A. One minute analysis of 200 histone posttranslational modifications by direct injection mass spectrometry. Genome Res. 2019;29:978–987. doi: 10.1101/gr.247353.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crowe S.O., Rana A.S.J.B., Deol K.K., Ge Y., Strieter E.R. Ubiquitin chain enrichment middle-down mass spectrometry enables characterization of branched ubiquitin chains in cellulo. Anal. Chem. 2017;89:4428–4434. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Valkevich E.M., Sanchez N.A., Ge Y., Strieter E.R. Middle-down mass spectrometry enables characterization of branched ubiquitin chains. Biochemistry. 2014;53:4979–4989. doi: 10.1021/bi5006305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kelleher N.L., Lin H.Y., Valaskovic G.A., Aaserud D.J., Fridriksson E.K., McLafferty F.W. Top down versus bottom up protein characterization by tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:806–812. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toby T.K., Fornelli L., Kelleher N.L. Progress in top-down proteomics and the analysis of proteoforms. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. (Palo Alto Calif.) 2016;9:499–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-071015-041550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Siuti N., Kelleher N.L. Decoding protein modifications using top-down mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:817–821. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu F., Xu Q., Dong X., Guy M., Guner H., Hacker T.A., Ge Y. Top-down high-resolution electron capture dissociation mass spectrometry for comprehensive characterization of post-translational modifications in Rhesus monkey cardiac troponin I. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2011;305:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tucholski T., Cai W., Gregorich Z.R., Bayne E.F., Mitchell S.D., McIlwain S.J., de Lange W.J., Wrobbel M., Karp H., Hite Z., Vikhorev P.G., Marston S.B., Lal S., Li A., Dos Remedios C. Distinct hypertrophic cardiomyopathy genotypes result in convergent sarcomeric proteoform profiles revealed by top-down proteomics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:24691–24700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006764117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Melani R.D., Skinner O.S., Fornelli L., Domont G.B., Compton P.D., Kelleher N.L. Mapping proteoforms and protein complexes from king cobra venom using both denaturing and native top-down proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2016;15:2423–2434. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.056523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schachner L.F., Jooß K., Morgan M.A., Piunti A., Meiners M.J., Kafader J.O., Lee A.S., Iwanaszko M., Cheek M.A., Burg J.M., Howard S.A., Keogh M.-C., Shilatifard A., Kelleher N.L. Decoding the protein composition of whole nucleosomes with Nuc-MS. Nat. Methods. 2021;18:303–308. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-01052-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leney A.C., El Atmioui D., Wu W., Ovaa H., Heck A.J.R. Elucidating crosstalk mechanisms between phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:E7255–E7261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620529114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simboeck E., Sawicka A., Zupkovitz G., Senese S., Winter S., Dequiedt F., Ogris E., Di Croce L., Chiocca S., Seiser C. A phosphorylation switch regulates the transcriptional activation of cell cycle regulator p21 by histone deacetylase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:41062–41073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.184481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kunowska N., Rotival M., Yu L., Choudhary J., Dillon N. Identification of protein complexes that bind to histone H3 combinatorial modifications using super-SILAC and weighted correlation network analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:1418–1432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vermeulen M., Eberl H.C., Matarese F., Marks H., Denissov S., Butter F., Lee K.K., Olsen J.V., Hyman A.A., Stunnenberg H.G., Mann M. Quantitative interaction proteomics and genome-wide profiling of epigenetic histone marks and their readers. Cell. 2010;142:967–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Garske A.L., Oliver S.S., Wagner E.K., Musselman C.A., LeRoy G., Garcia B.A., Kutateladze T.G., Denu J.M. Combinatorial profiling of chromatin binding modules reveals multisite discrimination. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:283–290. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bartke T., Vermeulen M., Xhemalce B., Robson S.C., Mann M., Kouzarides T. Nucleosome-interacting proteins regulated by DNA and histone methylation. Cell. 2010;143:470–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Z., Udeshi N.D., Slawson C., Compton P.D., Sakabe K., Cheung W.D., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D.F., Hart G.W. Extensive crosstalk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation regulates cytokinesis. Sci. Signal. 2010;3 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Noort V., Seebacher J., Bader S., Mohammed S., Vonkova I., Betts M.J., Kühner S., Kumar R., Maier T., O’Flaherty M., Rybin V., Schmeisky A., Yus E., Stülke J., Serrano L. Cross-talk between phosphorylation and lysine acetylation in a genome-reduced bacterium. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012;8:571. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beltrao P., Trinidad J.C., Fiedler D., Roguev A., Lim W.A., Shokat K.M., Burlingame A.L., Krogan N.J. Evolution of phosphoregulation: Comparison of phosphorylation patterns across yeast species. PLoS Biol. 2009;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Holt L.J., Tuch B.B., Villén J., Johnson A.D., Gygi S.P., Morgan D.O. Global analysis of Cdk1 substrate phosphorylation sites provides insights into evolution. Science. 2009;325:1682–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.1172867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nguyen Ba A.N., Moses A.M. Evolution of characterized phosphorylation sites in budding yeast. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27:2027–2037. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beltrao P., Albanèse V., Kenner L.R., Swaney D.L., Burlingame A., Villén J., Lim W.A., Fraser J.S., Frydman J., Krogan N.J. Systematic functional prioritization of protein posttranslational modifications. Cell. 2012;150:413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Beltrao P., Bork P., Krogan N.J., Noort V. Evolution and functional cross-talk of protein post-translational modifications. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2013;9:714. doi: 10.1002/msb.201304521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Minguez P., Parca L., Diella F., Mende D.R., Kumar R., Helmer-Citterich M., Gavin A.-C., van Noort V., Bork P. Deciphering a global network of functionally associated post-translational modifications. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012;8:599. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peng M., Scholten A., Heck A.J.R., van Breukelen B. Identification of enriched PTM crosstalk motifs from large-scale experimental data sets. J. Proteome Res. 2014;13:249–259. doi: 10.1021/pr4005579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Strumillo M.J., Oplová M., Viéitez C., Ochoa D., Shahraz M., Busby B.P., Sopko R., Studer R.A., Perrimon N., Panse V.G., Vikram G., Beltrao P. Conserved phosphorylation hotspots in eukaryotic protein domain families. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1977. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09952-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Studer R.A., Rodriguez-Mias R.A., Haas K.M., Hsu J.I., Vieitez C., Sole C., Swaney D.L., Stanford L.B., Liachko I., Bottcher R., Dunham M.J., de Nadal E., Posas F., Beltrao P., Villen J. Evolution of protein phosphorylation across 18 fungal species. Science. 2016;354:229–232. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Minguez P., Letunic I., Parca L., Bork P. PTMcode: A database of known and predicted functional associations between post-translational modifications in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D306–D311. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huang R., Huang Y., Guo Y., Ji S., Lu M., Li T. Systematic characterization and prediction of post-translational modification cross-talk between proteins. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:2626–2633. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huang K.-Y., Lee T.-Y., Kao H.-J., Ma C.-T., Lee C.-C., Lin T.-H., Chang W.-C., Huang H.-D. dbPTM in 2019: exploring disease association and cross-talk of post-translational modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D298–D308. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kirsch R., Jensen O.N., Schwämmle V. Visualization of the dynamics of histone modifications and their crosstalk using PTM-CrossTalkMapper. Methods. 2020;184:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2020.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aggarwal S., Banerjee S.K., Talukdar N.C., Yadav A.K. Post-translational modification crosstalk and hotspots in sirtuin interactors implicated in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Genet. 2020;11:356. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salas D., Stacey R.G., Akinlaja M., Foster L.J. Next-generation interactomics: Considerations for the use of co-elution to measure protein interaction networks. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2020;19:1–10. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R119.001803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Samavarchi-Tehrani P., Samson R., Gingras A.-C. Proximity dependent biotinylation: Key enzymes and adaptation to proteomics approaches. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2020;19:757–773. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R120.001941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]