Abstract

The novel coronavirus disease, caused by severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), rapidly spreading around the world, poses a major threat to the global public health. Herein, we demonstrated the binding mechanism of PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir to the coronavirus 3-chymotrypsin-like-protease (3CLpro) by means of docking and molecular dynamic (MD) simulations. The analysis of MD trajectories of 3CLpro with PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir revealed that 3CLpro–PF-07321332 and 3CLpro–α-ketoamide complexes remained stable compared with 3CLpro–ritonavir and 3CLpro–lopinavir. Investigating the dynamic behavior of ligand–protein interaction, ligands PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide showed stronger bonding via making interactions with catalytic dyad residues His41–Cys145 of 3CLpro. Lopinavir and ritonavir were unable to disrupt the catalytic dyad, as illustrated by increased bond length during the MD simulation. To decipher the ligand binding mode and affinity, ligand interactions with SARS-CoV-2 proteases and binding energy were calculated. The binding energy of the bespoke antiviral PF-07321332 clinical candidate was two times higher than that of α-ketoamide and three times than that of lopinavir and ritonavir. Our study elucidated in detail the binding mechanism of the potent PF-07321332 to 3CLpro along with the low potency of lopinavir and ritonavir due to weak binding affinity demonstrated by the binding energy data. This study will be helpful for the development and optimization of more specific compounds to combat coronavirus disease.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, 3CL protease, main protease

1. Introduction

The recent outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) affected more than 192 million people and killed 4.1 million across the globe (as of 23 July 2021) [1,2]. The genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 is closely related to SARS-CoV and β-coronavirus, sharing 79.5% and 96.2% sequence identity, respectively [3,4,5]. Coronaviruses belong to the Coronaviridae family and are found in birds and mammals [6]. The genomic organizations of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are similar [7] and both viruses comprise two polypeptides, pp1a and pp1ab. These polypeptides are processed into nonstructural proteins that play a fundamental part in the replication of these viruses, and the whole process is mediated by two kinds of main proteases: 3-chymotrypsin like protease (3CLpro) and papain-like proteases [8,9].

3CLpro, also called the main protease, consists of 306 amino acid residues, and is known to cleave at 11 sites in the polyproteins. The cleaving phenomenon leads to the formation of a helicase, single-stranded-RNA–binding protein, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase, endoribonuclease, and exoribonuclease [10,11]. 3CLpro forms a homodimer, and each subunit consists of three domains. The substrate-binding site of 3CLpro contains four subsites, S1′, S1, S2, and S4, and is highly conserved among all coronaviruses [3]. The active site of 3CLpro is located in a cleft between domains I and II, while domain III helps with the formation of the dimer and is connected to domain II via a long loop (residues 184–199) [3,8]. A 3CLpro antagonist will be highly specific to SARS-CoV-2 and will have minimal side effects because 3CLpro shares no homology with human proteases [3,12]. Owing to the essential role of 3CLpro in the transcription and replication of the viral genome and strong conservation of its binding-pocket residues, it is considered an ideal drug target in SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses.

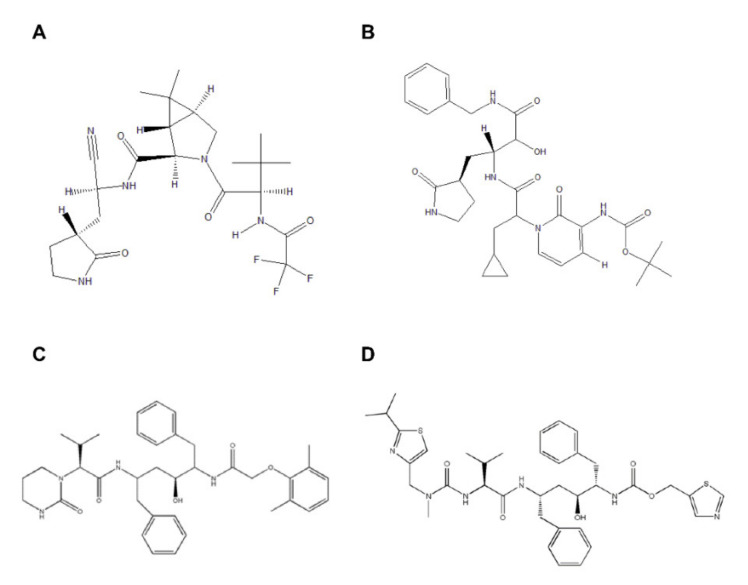

To date, more than 26% of world population has received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine [13]. The COVID-19 pandemic requires not only prevention via vaccine but also drug treatment. Antiretroviral drugs have been tested in past human coronavirus infections and against SARS-CoV-2, but a recent clinical trial of lopinavir and ritonavir failed to show any clinical benefit in COVID-19 disease. Protease inhibitors are used to treat HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C, but PF-07321332 (Figure 1A) is the first oral protease inhibitor to target the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In addition to PF-07321332, α-ketoamide (Figure 1B) has been reported to show in vitro inhibition of 3CLpro [14]. The bespoke clinical candidate PF-07321332 (NCT04756531) is a potent protease inhibitor with potent antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2.

Figure 1.

2D structure representation of (A) PF-07321332, (B) α-ketoamide, (C) lopinavir, and (D) ritonavir.

The development of new drugs or vaccines is time-consuming; therefore, a drug-repurposing strategy was approved for the treatment of COVID-19 at this critical time [15]. The use of FDA-approved anti–HIV-I drugs lopinavir and ritonavir (Figure 1C,D) in combination against MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV has been reported earlier [16,17,18,19]. This combination of lopinavir and ritonavir is currently in a phase II trial along with interferon β-1b against MERS-CoV [16]. In contrast, for the treatment of MERS, this regimen is in phase IV of clinical trials in combination with Arbidol® hydrochloride and oseltamivir (NCT04255017).

PF-07321332 is a 3CLpro inhibitor with potent in vitro antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses (NCT04756531). Protease inhibitors interfere with the cutting step of the protease enzyme reaction. These drugs interact with the protease and block its polypeptide cutting ability. Lopinavir is used as a retroviral-protease inhibitor for the treatment of HIV-I infection and is usually co-administered with ritonavir, which increases the half-life of lopinavir and inactivates cytochrome P450 3A4 [20,21]. PF-07321332 is administered in combination with low doses of ritonavir as a booster to increase the bloodstream levels of PF-07321332. In the present study, the binding mechanisms of PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir were explored through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and binding energy calculations. This study offers a deeper understanding of the mechanism of binding of these drugs to 3CLpro and will be helpful to identify potent protease inhibitor candidates for SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses. In future, our data can be used to identify novel drug candidates using supervised machine learning methods [22].

2. Results

2.1. Comparative Analysis of PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, Lopinavir, and Ritonavir Binding to 3CLpro

The crystal structure of 3CLpro in complex with PF-07321332, lopinavir, and ritonavir is not yet available. Therefore, the docked complex of PF-07321332, lopinavir, and ritonavir with 3CLpro was generated using the Molecular operating environment (MOE) software. Among the top 10 docking solutions, the best ligand conformation was selected based on the docking score and binding pose. In addition, the structure of α-ketoamide co-crystalized with 3CLpro (PDB ID: 6Y2F) was retrieved from the RCSB PDB database.

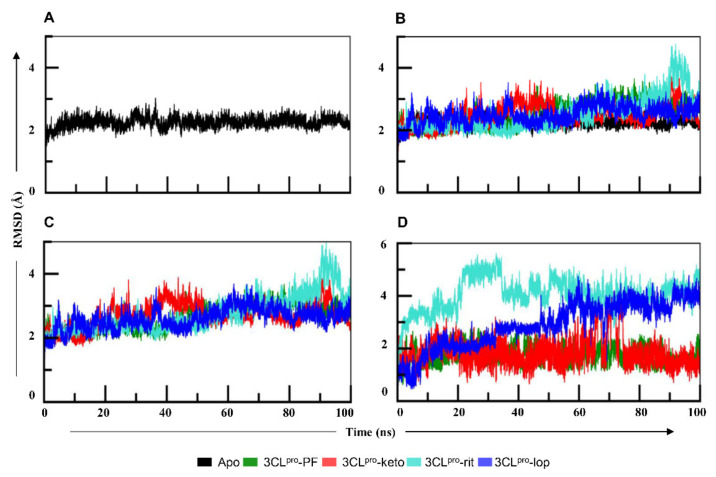

To elucidate the mechanism of binding of PF-07321332 (PF), α-ketoamide (keto), lopinavir (lop), and ritonavir (rit) with 3CLpro, all complexes were subjected to 100 ns simulations in Gromacs. To assess the stability of all four systems, root mean square deviation (RMSD) values were calculated for each ligand and protein individually and in complexed form, as presented in Figure 2. RMSD of apo-3CLpro at 45 ns indicated a deviation up to 3 Å, after which the system was stabilized and oscillated in the mean range of 2.5 Å (Figure 2A). The protein in 3CLpro–PF (Figure 2B) remained stable throughout simulation with an average RMSD of 2.7 Å, while in 3CLpro–keto, the protein fluctuated in a 30–50 ns interval. The protein in 3CLpro–rit showed RMSD rising above 3 Å after 60 ns with higher fluctuation at 90 ns. The RMSD protein graph of 3CLpro–lop and 3CLpro–rit deviated from the apo-form. The 3CLpro–rit showed sinusoidal behavior until 60 ns and higher peak in the 60–80 ns time interval. Nevertheless, the RMSD of the protein in 3CLpro–lop increased gradually from 60 ns onwards (Figure 2B). It also manifested fewer fluctuations initially than apo-3CLpro did until 40 ns, and then both systems yielded somewhat similar patterns up to 75 ns, and suddenly, the protein in 3CLpro–rit showed a remarkable deviation between 75 ns and 100 ns (Figure 2B). While assessing the RMSD of all four complexes (Figure 2C), we noticed that the 3CLpro–PF complex remained stable during the simulation. The RMSD of 3CLpro–keto complex fluctuated between 20–50 ns and then gradually stabilized. 3CLpro–rit and 3CLpro–lop complexes showed similar trend as their proteins. The RMSD graph of the ligands (Figure 2D) indicated that lopinavir and ritonavir featured greater deviations in comparison with other two ligands, whereas PF manifested the least deviations. The ligand in the 3CLpro–keto complex showed high jumps around 70 ns but quickly gained stability with a RMSD value of 1.5 Å. RMSD of the ligand in 3CLpro–lop showed increasing trend from 45 ns onwards. The ligand in 3CLpro–rit manifested a sudden increase in RMSD after 20 ns and fluctuated between 3 and 4.5 Å but attained stability later. We concluded that inhibitors PF and α-ketoamide imparted stability to the protein in their complexes.

Figure 2.

(A) The root mean square deviation (RMSD) graph of the apo form of 3CLpro during the 100 ns simulation. The graph suggests that protein was stable during the whole simulation, with an average RMSD of 2.2 Å. (B) The RMSD graphs of all four proteins in complexes in comparison with the apo form. The protein in 3CLpro–PF and 3CLpro–keto remained stable whereas in 3CLpro–lop and 3CLpro–rit, it showed more fluctuations than in the other two 3CLpro systems. (C) The RMSD graph of 3CLpro complexes. The 3CLpro–rit and 3CLpro–lop complexes showed similar trend as the proteins. (D) RMSD graphs of the ligands in complexes with 3CLpro. The ligands PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide seemed stable, whereas both lopinavir and ritonavir in 3CLpro complexes featured noticeable fluctuations. PF—PF-07321332; keto—α-ketoamide; rit—ritonavir; lop—lopinavir.

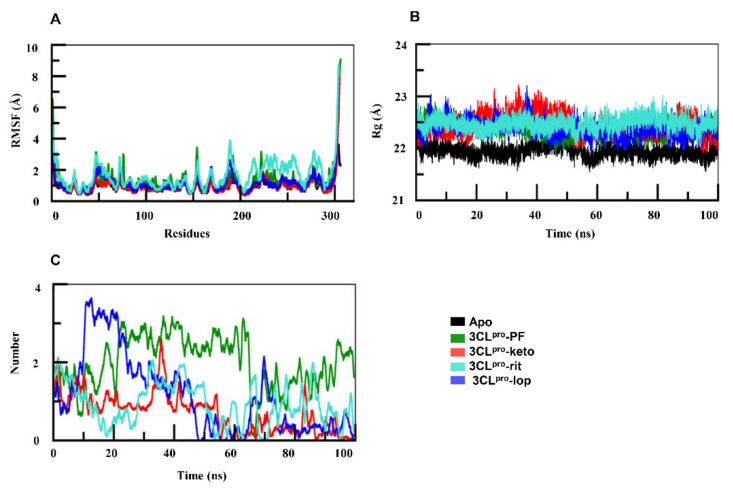

To analyze the dynamic behavior of protein residues, root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values were assessed. As compared with the apo form, RMSF (Figure 3A) of the protein in 3CLpro–rit indicated that amino acid residues 45–75 in the spanning region fluctuated by more than 3 Å. By contrast, in 3CLpro–lop, the residues of 3CLpro between positions 45 and 75 fluctuated in the range similar to that of its apo form, i.e., 2.5 Å (Figure 3A). The rest of the protein residues of both complexes oscillated equally relative to the apoprotein. Overall, the residues of the 3CLpro in complex with the ligands PF and α-ketoamide did not undergo any fluctuation, while in 3CLpro–rit complex, the protein featured the greatest fluctuations in comparison with the apo form.

Figure 3.

(A) Root mean square fluctuation graphs of apo-3CLpro and of 3CLpro complexes. In comparison with the apo-form, regions spanning amino acid residues 45–75 and 150–200 in both docked complexes showed deviations. (B) Radius of gyration of the 3CLpro in complexes was higher than that of its apo-form. (C) Number of hydrogen bonds in the four complexes. PF—PF-07321332; keto—α-ketoamide; rit—ritonavir; lop—lopinavir.

To assess the compactness of protein structure, we calculated the radius of gyration (Rg). This parameter of the protein in 3CLpro–PF (Figure 3B) remained in the steady state and close to that of the apoprotein during the simulations, which means that the folding of the protein in 3CLpro–PF complex remained undisturbed. Figure 3B illustrates that the apoprotein followed a similar trend and oscillated at ~22 Å. The Rg of the protein in 3CLpro–keto fluctuated between 20–50 ns; thereafter, it retained steady state for the rest of the simulation. Rg of 3CLpro–rit remained steady up to 50 ns, then it gradually increased. 3CLpro–lop fluctuated with the highest peak of 23 Å near time point 39 ns, indicating that protein folding was disturbed. Lopinavir and ritonavir might have led to the unfolding in the 3CLpro and thus exhibited increasing trend in Rg of the protein.

Next, the number of hydrogen bonds was calculated to evaluate the protein–ligand interactions during the simulations. The PF formed three hydrogen bonds (Figure 3C), and this remained consistent throughout the time trajectory. The α-ketoamide formed two bonds initially but their number dropped to one after 50 ns. The lopinavir initially formed three hydrogen bonds with 3CLpro, but their number gradually decreased, and the hydrogen bonds disappeared around 48 ns. Lopinavir formed two bonds in the beginning and ritonavir formed one, but these interactions were inconsistent throughout the MD simulations (Figure 3C). Therefore, the hydrogen bonds formed by lopinavir and ritonavir with 3CLpro are inconsistent and weak as compared with the interactions of 3CLpro with PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide.

2.2. Interaction Analysis of PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, Lopinavir, and Ritonavir with 3CLpro

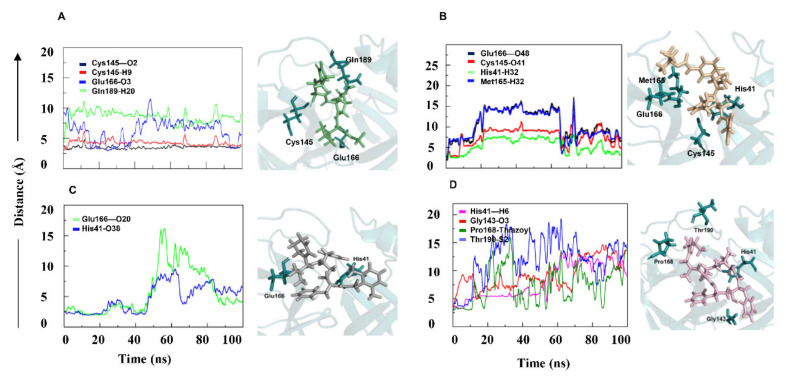

To evaluate the ligand–protein interactions, we computed the minimum distance between interacting atoms of the ligand and protein residues. Our analysis revealed the dynamics of the interaction of PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir with 3CLpro (Figure 4). In 3CLpro–PF, three hydrogen bonds were formed (Table 1). The distance of Cys145–O2, Glu166–O3, and Gln189–H20 bonds remained within 4 Å (Figure 4A). The catalytic dyad residue Cys145 made strong bonds with atoms O2 and H9 as they remained intact during the simulation. This showed that the PF-07321332 has high affinity towards 3CLpro. The 4-methoxylindole group interacted through a hydrogen bond with the backbone of Glu166, a key residue located in the middle of the binding site. The study of Glu166 mutation, carried out in SARS-CoV 3CL protease (96% identity to SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro), has corroborated the role of this key residue in the substrate-induced dimerization [23]. The trifluoroacetamide moiety of the PF-07321332 compound involved in the Gln189–H20 bond accommodated the cyclopropyl-proline moiety to occupy the central portion of the binding site. Subsequently, the pyrrolidone moiety rearrangement led to bond formation of reactive nitrile group with Cys145. According to the analysis of the entire trajectory of 3CLpro–PF complex, PF-07321332 contacted Leu141 and Gln142. Leu141, Gln142, and Cys145 were part of the oxyanion loop (residues 138–145), which is lining the glutamine binding pocket and is presumably involved in the stabilization of the tetrahedral acyl transition state [24]. The ligand in 3CLpro–keto made three hydrogen bond interactions (Glu166–O48, Cys145–O41, and Met165–O48) and one arene interaction, His41–H32 (Figure 4B). The cyclopropyl moiety facilitated ligand binding in the shallow substrate-binding pocket at the surface of the 3CLpro. The α-keto group of the inhibitor interacted with Cys145. The study reported that thiohemiketal formation occurred in a reversible reaction by the nucleophilic attack of the catalytic Cys145 on the ligand [14]. In our study, α-ketoamide occupied the substrate binding space and its carbonyl oxygen formed hydrogen bond with the main-chain oxygen of Glu166. All these interactions kept fluctuating as the distance between the interacting entities continuously changed due to the bulky nature of the ligand. Similarly, in the 3CLpro–rit complex, three hydrogen bonds and an arene-type interaction were formed (Figure 4D). The length of His41–H6 and Gly143–O3 bonds remained within 7 Å during the initial 50 ns and continuously increased onwards. In the arene-type interaction, the distance between Pro168 and the thiazolyl group fluctuated within 5–10 Å during the simulation. The hydrogen bond Thr190–S2 appeared during the initial 10 ns, and the bond length was within 5 Å, but it diminished after 10 ns (Figure 4D). Two hydrogen bonds formed in 3CLpro–lop. Initially, the bond length of His41–O38 and Glu166–O20 (Table 1) was less than 5 Å, but after 50 ns, an increase in the bond length was detected because of ligand fluctuations, as depicted in the RMSD graph (Figure 2D and Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

The minimum distance graph of protein–ligand interactions. The interaction distance between the protein and ligand in 3CLpro–PF (A) and 3CLpro–keto (B) remained constant. Interaction in 3CLpro–lop (C) initially remained constant but showed major fluctuations afterwards. In 3CLpro–rit (D), the lengths of all four bonds continuously increased. PF—PF-07321332; keto—α-ketoamide; rit—ritonavir; lop—lopinavir.

Table 1.

Residue and ligand atom interactions with the bond type and energy in 3CLpro complexes.

| Complex | Residue | Ligand Atom | Bond Type | Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3CLpro–PF | Cys145 | O2 | Hydrogen | −5.04 |

| Cys145 | H9 | Hydrogen | −5.04 | |

| Glu166 | O3 | Hydrogen | −4.41 | |

| Gln189 | H20 | Hydrogen | −3.01 | |

| 3CLpro–keto | Glu166 | O48 | Hydrogen | −0.70 |

| Cys145 | O41 | Hydrogen | −0.80 | |

| Met165 | O48 | Hydrogen | −0.80 | |

| His41 | H32 | Arene | −0.90 | |

| 3CLpro–lop | His41 | O38 | Hydrogen | −4.1 |

| Glu166 | O20 | Hydrogen | −1.6 | |

| 3CLpro–rit | His41 | H6 | Arene | −3.0 |

| Gly143 | O3 | Hydrogen | −2.2 | |

| Pro168 | Thiozyl group | Arene | −0.8 | |

| Thr190 | S2 | Hydrogen | −0.8 |

2.3. Binding Free Energy Calculation

Protein–ligand binding affinity is essential in understanding molecular recognition. The bespoke antiviral clinical candidate PF-07321332 (NCT04756531) is a potent 3CLpro inhibitor with antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2. The relative binding free energy of PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir with 3CLpro was computed. To calculate the binding affinity of these ligands with 3CLpro, we extracted 1000 frames from the simulation trajectories. The g_mmpbsa (Table 2) computation revealed that the binding affinity of PF-07321332 for 3CLpro was higher in comparison with α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir. Relative to α-ketoamide, PF-07321332 showed more considerable binding energy toward 3CLpro, almost by 28 kJ/mol, and three times more than lopinavir and ritonavir. These data showed that PF-07321332 had a stronger binding affinity for 3CLpro.

Table 2.

Binding energy of 3CLpro and HIV-I protease complexes as computed via the g_mmpbsa method.

| Complex | VdW Energy | Electrostatic | Polar Solvation | SASA | Total Binding Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3CLpro–PF | −135.294 +/− 16.258 | −39.293 +/− 25.780 | 96.026+/− 21.556 | −23.441 +/− 2.526 | −102.002 +/− 21.336 |

| 3CLpro–keto | −76.478+/− 25.052 | −40.348 +/− 30.471 | 50.648 +/− 49.365 | −7.887 +/− 3.036 | −74.065 +/− 22.579 |

| 3CLpro–lop | −110.529 +/− 28.28 | −65.740 +/−26.09 | 168.011 +/− 33.31 | −25.239 +/−2.40 | −33.497 +/− 26.52 |

| 3CLpro–rit | −75.994 +/− 60.285 | −55.115 +/− 23.09 | 91.803 +/− 18.798 | −4.219 +/− 8.798 | −43.525 +/− 29.171 |

3. Discussion

Combating the COVID-19 pandemic requires both prevention, including vaccine-based prevention, and targeted treatment for those who get infected. Given the way SARS-CoV-2 is evolving into new genetic variants and the worldwide impact of COVID-19, it is likely that access to treatment alternatives is crucial, now and beyond the pandemic. The frequent mutations aid the virus to infect different hosts and increase the virulence and transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2. The RNA viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, develop one mutation per replication cycle, which means RNA viruses may adapt to new environment, but these viruses are also restricted in their ability to change their genomes because they must keep their mutation rate low in order to survive [25]. Several mutations have been reported in the viral genome so far; 106 major amino acid substitutions were found to be responsible for increased virulence and transmissibility of the virus [26]. Most of these missense mutations occurred in structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2, such as spike (S) [27] and nucleocapsid (N) proteins. Only one point mutation, G15S, has been predicted using in silico studies in 3CLpro, but this residue is far from the active site and has a destabilizing effect on the protein structure [26]. Therefore, a virus comprising such mutations with a destabilizing effect would not last for long and would have reduced virulence. Only stabilizing mutations, such as in the S protein, increase the virulence and transmissibility of the virus [28]. A recent study has reported that the significant key mutations are located at the inverted repeat regions and CpG islands. These findings showed the role of mutations in the instability of the viral genome [29].

In this study, we have explored the binding of PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir to SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro through MD simulation and MMPBSA calculation. PF-07321332 (NCT04756531) and α-ketoamide molecules that specifically bind to and inhibit SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro could be promising alternatives to fight the pandemic [14]. The comparative binding mode analysis of PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir might provide a glimpse into designing rational drugs through the modification of the inhibitors based on the residues in the active site of the enzyme.

To determine the mechanism of binding of PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir to 3CLpro, molecular docking of these molecules was done. The best docking solutions for PF-07321332, lopinavir, and ritonavir were selected based on the docking score and the best binding pose of the ligand. To understand the binding mechanism of PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide along with the two antiretroviral drugs, lopinavir and ritonavir, to 3CLpro, MD simulations were performed for 100 ns. Backbone RMSDs of the 3CLpro–PF and 3CLpro–keto complexes were stable, whereas the 3CLpro–lop complex featured a deviation at 60–80 ns and the 3CLpro–rit complex a deviation between 75 ns and 100 ns (Figure 2B). RMSD deviation of the 3CLpro protein was also analyzed in the ligand-bound form. The RMSD of 3CLpro (Figure 2C) was found to be stabler in association with either PF-07321332 or α-ketoamide than with lopinavir or ritonavir. In contrast to the other systems, 3CLpro in complex with ritonavir featured marked deviation between 88 and 95 ns of the simulation. Both ligands PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide are stabler with 3CLpro in comparison with lopinavir and ritonavir because later two underwent marked deviation during the simulation (Figure 2D). The recent clinical trials have also showed these antiretrovirals are not efficacious as they did not significantly accelerate clinical improvements in serious COVID-19 patients [30]. Our binding energy data also showed low affinity of these drugs towards 3CLpro. To assess the impact of ligand binding on protein residues, RMSF of 3CLpro were analyzed in all four complexes. With either lopinavir or ritonavir, amino acid residues 45–65 and 145–200 showed greater fluctuations in comparison with the apo-form (Figure 3A). These fluctuating regions mainly consist of binding-site residues that are interconnected by a hydrogen bond network and are involved in catalytic dyad formation between His41 and Cys145 [31,32,33]. However, the RMSF of the protein in 3CLpro–PF showed similar trend as its apo-form. Compactness, which determines stability of a protein, was evaluated for 3CLpro using Rg. The compactness of 3CLpro in complex with PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide remained in steady state the same as the one of its apo-form (Figure 3B). Rg of 3CLpro in its complex with ritonavir or lopinavir was higher than that of apo-3CLpro. Nonetheless, 3CLpro compactness after PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide binding remained constant throughout the simulation.

One of the most interesting examples of MD application is the drug discovery area, where this method drives experiments [34,35]. To analyze the interactions of the four molecules with 3CLpro, the minimum distance between the atoms of interacting residues of each protein and ligand (PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir) were calculated as a function of simulation time to analyze the dynamic behavior of the interacting groups. In the interaction analysis, PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide showed stronger interactions with 3CLpro, and these interactions remained intact during the simulation because the minimum distance between the interacting groups stayed almost unchanged. The interactions, i.e., Cys145–O2 and Cys145–H9 in 3CLpro–PF (Figure 4A), remained intact during the simulation. This showed that PF-07321332 was strongly bonded to 3CLpro and capable to disrupt the His41–Cys145 catalytic dyad, which, together with the N-terminus residues 1 to 7, is thought to have a vital role in proteolytic activity [36]. The Glu166 anchor hooks the ligand tightly to the central region of the binding site, which facilitate the formation of further interactions with other residues. Gly143 of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro was reported to be the most favorable residue to form hydrogen bonds with ligands, followed by Glu166, Cys145, and His163 [37]. The amides of Gly143, Cys145, and Ser144 form the cysteine protease’s canonical “oxyanion hole”. The interaction of PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide with the catalytic site residues may cause the distortion of the oxyanion hole in the reaction mechanism, and it may lead to the inhibition of 3CLpro in SARS-CoV-2. Compared with PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide, both antiretroviral drugs lopinavir and ritonavir manifested weaker interactions with 3CLpro, judging by binding energy values (Table 2). PF-07321335 interacts with Cys145, thereby disrupting His41–Cys145 catalytic dyad. The α-ketoamide has the same mechanism as reported earlier carries; a nucleophilic attack of the catalytic Cys145 on the α-keto group of the inhibitor, disrupting the His41–Cys145 catalytic dyad [14]. Our binding energy data (Table 2) revealed that PF-07321335 has higher affinity towards 3CLpro. This is in accordance with PF-07321335 showing a potent inhibition of 3CLpro (NCT04756531). Lopinavir and ritonavir showed weaker interactions because only two residues, His41 and Glu166, were found to be involved in hydrogen bonding. The minimum distance of 5 Å between these interacting entities persisted up to 45 ns; after that, it fluctuated. In contrast with PF-07321335 and α-ketoamide, lopinavir and ritonavir engaged in interactions with 3CLpro, but these interactions varied substantially. Some chemical substitutions in lopinavir and ritonavir (such as the addition of an α-keto group) can act as electrophiles that may prevent the His41–Cys145 dyad formation by a nucleophilic attack of Cys145. Although in our simulations, lopinavir and ritonavir engaged in interactions with His41 and Cys145 along with other catalytic site residues, these contacts fluctuated considerably, as evident from our interaction analysis. Coronavirus protease 3CLpro lacks a C2-symmetric pocket, through which lopinavir and ritonavir bind to HIV-I protease. The absence of a C2-symmetric pocket in coronavirus 3CLpro could be the reason why these drugs do not bind to 3CLpro, which makes them ineffective in COVID-19 patients. The binding energy data (Table 2) showed that lopinavir and ritonavir have weak affinity to 3CLpro.

Conclusively, 3CLpro is an important drug target, which cleaves the viral polyprotein at 11 different cleavage sites and is required for viral maturation. The druggability of 3CLpro has already been demonstrated in various studies. The mutations in the dominant variants of SARS-CoV-2, such as B.1.1.7 and B.1.617, with higher transmissibility rate were studied and it has been demonstrated that most of the mutations have been found in the receptor binding domains or structural proteins, but no mutation has been reported in 3CLpro so far [38]. Therefore, 3CLpro is an attractive target for anti-COVID-19 drug discovery. In recent studies, many new compounds have been reported as potential inhibitors of 3CLpro [14,39,40,41,42]. We included four of the potential inhibitors in our study, compared their binding energy and discussed their interactions with the protein to identify the potent inhibitor. We found that the compound PF-07321332, currently in clinical trials, was the best of these four compounds. In addition to these molecules, sterenin M was also reported in a recent computational study [39] to bind to the same active binding site as PF-07321332 and interact with the residues of catalytic dyad, but its total binding energy profile showed that the binding of PF-07321332 with protein was much stabler than the one of sterenin M [39]. In similar studies, the identified compounds bind to the same binding site, but the stability of complex is lower than the one of PF-07321332 [40,41]. Hence, considering the current pandemic situation, it is crucial to find some potent drug candidate with good binding affinity. The MD simulation and MMPBSA are widely used for assessing protein–ligand binding affinity, but there are a few limitations of the MD simulations, such as many biochemical processes including receptor conformational shifts relevant to drug binding occur on time scales that are much longer than those amenable to simulations. In MD simulations, each atom is assigned a fixed partial charge before simulation. However, the electron clouds in surrounding atoms shift continuously according to their environments. A dynamic and responsive representation of atomic partial charges would be more accurate.

4. Conclusions

A detailed analysis of interactions of proteins and ligands represents an optimized method for the rational design of new compounds. Binding energy helps to identify a lead compound. MD, free energy perturbation, meta-dynamics, and other methods are consistently used for studying drug–target binding. Assessment of these methods may help to achieve the most definite target-optimized affinity with improved drug efficacy [43]. Integrating MD simulation with binding-free-energy calculation by means of g_mmpbsa to determine interaction free energy between a ligand and protein is an efficient method for distinguishing between active and inactive molecules [44]. The comparative analysis of PF-07321332, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir via MD simulation provided a detailed insight into the interactions of these compounds with 3CLpro. We believe that our findings revealed the binding mechanism of PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide and further explained the inability of lopinavir and ritonavir to cause clinical improvement in severe COVID-19 patients by due to their low affinity towards 3CLpro. We believe the dynamic interaction and binding energy of PF-07321332 and α-ketoamide will be helpful in designing potent inhibitors for 3CLpro.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. System Preparation for Molecular Docking and MD Simulations

The crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID: 6M03) and structures of 3CLpro in complex with 3CLpro (PDB ID 6Y2K) [45,46] were downloaded from the PDB [47]. The 2-D structure of PF-07321335 was drawn in Chemdraw and the three-dimensional (3D) coordinates of lopinavir (PubChem CID: 92727) and ritonavir (PubChem CID: 392622) were retrieved from the PubChem database [48] for molecular docking. All hydrogens and missing atoms were added to the proteins, while crystal water was removed. The MOE software from Chemical Computing Group Canada (Montreal, QC, Canada) [49] was used for energy minimization of 3CLpro and both drugs to remove any steric clashes and to improve the bond lengths and bond angles. The default parameters were used for energy minimization, while the gradient was set to 0.01 rms kcal/mol.

5.2. Molecular Docking of 3CLpro to Lopinavir and Ritonavir

PF-07321335, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir were docked into the binding pocket of 3CLpro using the MOE software [49]. The key residues involved in ligand binding reported in the literature were selected for docking: His41, Asn142, Cys145, His164, Met165, Glu166, Gln189, and Thr190. The triangle matcher placement method was selected with the London dG scoring function, and the induced-fit method was applied for refinement of the binding poses of ligands. A total of 100 conformations were generated for each ligand, and the best pose with the lowest binding energy was selected. Complexes of 3CLpro with PF-07321335, α-ketoamide, lopinavir, and ritonavir were analyzed and saved for MD simulations.

5.3. Building the Ligand Topology

Prior to MD simulations, the ligand topology was generated on the CHARMM general force field (CGenFF) server (University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA) [50]. Ligands, along with their 3D coordinates, were extracted from their respective complexes and saved in mol2 file format, and all hydrogens were added. The mol2 file was uploaded to the CGenFF server, which generated a CHARMM-compatible stream file comprising ligand information, such as atom types, charges, and bond parameters. A Python script was executed to convert the stream files into Gromacs-compatible [51,52] files. These files were used for the MD simulations.

5.4. MD Simulations of Complexes

The dataset for MD simulations contained apo-3CLpro and four 3CLpro complexes. All five MD simulations were carried out using the Gromacs (University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands) software for 100 ns each, and the CHARMM36 forcefield [53] was applied to the systems. Periodic boundary conditions were used, and the protein was placed inside a 10 Å cubic box. For solvation of the system, the TIP3P water model [54] was used, and an appropriate amount of counterions was added to neutralize the system. The solvated electroneutral system was subjected to energy minimization by the steepest-descent algorithm, followed by temperature and pressure equilibration steps. The production run was carried out for 100 ns in each system, and data analysis was performed by means of Gromacs built-in tools, MOE, and PyMOL (Schrödinger, LLC. DeLano Scientific, San Francisco, CA, USA) [55,56].

5.5. Binding-Free-Energy Calculation

The molecular mechanics Poisson–Boltzmann surface area (MMPBSA) method was used to compute the binding free energy of all complexes. A thousand frames were extracted from each 100 ns simulation trajectory by means of the gmx trjconv utility of Gromacs. The extracted frames were used for free-binding-energy calculation with the help of the g_mmpbsa tool [44]. The total binding free energy (ΔGbinding) was calculated as

| ΔGbinding = ΔGcomplex − (ΔGprotein + ΔGligand) |

where Gcomplex is the average free energy of the complex, and Gprotein and Gligand are the average energy values of the protein and ligand.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A. and M.B.; methodology, B.A., Q.u.A., and M.B.; formal analysis, B.A., Q.u.A., and M.B.; data curation, B.A., Q.u.A., and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A., Q.u.A., and M.B.; writing—review and editing, B.A. and M.B.; supervision, S.C.; project administration, M.S.K. and S.C.; funding acquisition, M.S.K. and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF- 2020R1F1A1071517, 2019M3D1A1078940, and 2019R1A6A1A11051471).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The structure models and simulation trajectories are available upon request (sangdunchoi@ajou.ac.kr). All remaining data are contained within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Velavan T.P., Meyer C.G. The COVID-19 epidemic. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2020;25:278–280. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center COVID-19 Map. [(accessed on 10 August 2020)]; Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- 3.Dai W., Zhang B., Su H., Li J., Zhao Y., Xie X., Jin Z., Liu F., Li C., Li Y., et al. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science. 2020;368:1331–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N., et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durai P., Batool M., Shah M., Choi S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: Transmission, virology and therapeutic targeting to aid in outbreak control. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015;47:e181. doi: 10.1038/emm.2015.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batool M., Shah M., Patra M.C., Yesudhas D., Choi S. Structural insights into the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus 4a protein and its dsRNA binding mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11362. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11736-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: Basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science. 2003;300:1763–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Boheemen S., de Graaf M., Lauber C., Bestebroer T.M., Raj V.S., Zaki A.M., Osterhaus A.D., Haagmans B.L., Gorbalenya A.E., Snijder E.J., et al. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. mBio. 2012;3:e00473-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00473-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muramatsu T., Takemoto C., Kim Y.T., Wang H., Nishii W., Terada T., Shirouzu M., Yokoyama S. SARS-CoV 3CL protease cleaves its C-terminal autoprocessing site by novel subsite cooperativity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:12997–13002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601327113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thiel V., Ivanov K.A., Putics A., Hertzig T., Schelle B., Bayer S., Weissbrich B., Snijder E.J., Rabenau H., Doerr H.W., et al. Mechanisms and enzymes involved in SARS coronavirus genome expression. J. Gen. Virol. 2003;84:2305–2315. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren Z., Yan L., Zhang N., Guo Y., Yang C., Lou Z., Rao Z. The newly emerged SARS-like coronavirus HCoV-EMC also has an “Achilles’ heel”: Current effective inhibitor targeting a 3C-like protease. Protein Cell. 2013;4:248–250. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-2841-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchie H., Mathieu E., Rodés-Guirao L., Appel C., Giattino C., Ortiz-Ospina E., Hasell J., Macdonald B., Beltekian D., Roser M. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) [(accessed on 31 July 2021)];2020 Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

- 14.Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved alpha-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalil A.C. Treating COVID-19-Off-Label Drug Use, Compassionate Use, and Randomized Clinical Trials During Pandemics. JAMA. 2020;323:1897–1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arabi Y.M., Alothman A., Balkhy H.H., Al-Dawood A., Al Johani S., Al Harbi S., Kojan S., Al Jeraisy M., Deeb A.M., Assiri A.M., et al. Treatment of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome with a combination of lopinavir-ritonavir and interferon-beta1b (MIRACLE trial): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:81. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu C.M., Cheng V.C., Hung I.F., Wong M.M., Chan K.H., Chan K.S., Kao R.Y., Poon L.L., Wong C.L., Guan Y., et al. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: Initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252–256. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen F., Chan K.H., Jiang Y., Kao R.Y., Lu H.T., Fan K.W., Cheng V.C., Tsui W.H., Hung I.F., Lee T.S., et al. In vitro susceptibility of 10 clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. J. Clin. Virol. 2004;31:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu C.Y., Jan J.T., Ma S.H., Kuo C.J., Juan H.F., Cheng Y.S., Hsu H.H., Huang H.C., Wu D., Brik A., et al. Small molecules targeting severe acute respiratory syndrome human coronavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:10012–10017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sevrioukova I.F., Poulos T.L. Structure and mechanism of the complex between cytochrome P4503A4 and ritonavir. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:18422–18427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010693107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandwani A., Shuter J. Lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of HIV-1 infection: A review. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2008;4:1023–1033. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batool M., Ahmad B., Choi S. A Structure-Based Drug Discovery Paradigm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2783. doi: 10.3390/ijms20112783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng S.C., Chang G.G., Chou C.Y. Mutation of Glu-166 blocks the substrate-induced dimerization of SARS coronavirus main protease. Biophys J. 2010;98:1327–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fornasier E., Macchia M.L., Giachin G., Sosic A., Pavan M., Sturlese M., Salata C., Moro S., Gatto B., Bellanda M., et al. A novel conformational state for SARS-CoV-2 main protease. bioxRiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.04.433882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartas M., Brazda V., Bohalova N., Cantara A., Volna A., Stachurova T., Malachova K., Jagelska E.B., Porubiakova O., Cerven J., et al. In-Depth Bioinformatic Analyses of Nidovirales Including Human SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV Viruses Suggest Important Roles of Non-canonical Nucleic Acid Structures in Their Lifecycles. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1583. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacob J.J., Vasudevan K., Pragasam A.K., Gunasekaran K., Veeraraghavan B., Mutreja A. Evolutionary Tracking of SARS-CoV-2 Genetic Variants Highlights an Intricate Balance of Stabilizing and Destabilizing Mutations. mBio. 2021;12:e0118821. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01188-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.West A.P., Jr., Wertheim J.O., Wang J.C., Vasylyeva T.I., Havens J.L., Chowdhury M.A., Gonzalez E., Fang C.E., Di Lonardo S.S., Hughes S., et al. Detection and characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.526 in New York. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4886. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25168-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J.S., Jang J.H., Kim J.M., Chung Y.S., Yoo C.K., Han M.G. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of Point Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Genome. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2020;11:101–111. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.3.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goswami P., Bartas M., Lexa M., Bohalova N., Volna A., Cerven J., Cervenova V., Pecinka P., Spunda V., Fojta M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 hot-spot mutations are significantly enriched within inverted repeats and CpG island loci. Brief. Bioinform. 2021;22:1338–1345. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang J., Fan G., Ruan L., Song B., Cai Y., Wei M., et al. A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ul Qamar M.T., Alqahtani S.M., Alamri M.A., Chen L.L. Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 3CL(pro) and anti-COVID-19 drug discovery from medicinal plants. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020;10:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paasche A., Zipper A., Schäfer S., Ziebuhr J., Schirmeister T., Engels B. Evidence for Substrate Binding-Induced Zwitterion Formation in the Catalytic Cys-His Dyad of the SARS-CoV Main Protease. Biochemistry. 2014;53:5930–5946. doi: 10.1021/bi400604t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue X., Yu H., Yang H., Xue F., Wu Z., Shen W., Li J., Zhou Z., Ding Y., Zhao Q., et al. Structures of two coronavirus main proteases: Implications for substrate binding and antiviral drug design. J. Virol. 2008;82:2515–2527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02114-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X., Shi D., Zhou S., Liu H., Liu H., Yao X. Molecular dynamics simulations and novel drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2018;13:23–37. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2018.1403419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borhani D.W., Shaw D.E. The future of molecular dynamics simulations in drug discovery. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2012;26:15–26. doi: 10.1007/s10822-011-9517-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mengist H.M., Dilnessa T., Jin T. Structural Basis of Potential Inhibitors Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. Front. Chem. 2021;9:622898. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.622898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen D.D., Gao K., Chen J., Wang R., Wei G.W. Unveiling the molecular mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibition from 137 crystal structures using algebraic topology and deep learning. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:12036–12046. doi: 10.1039/D0SC04641H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jukic M., Skrlj B., Tomsic G., Plesko S., Podlipnik C., Bren U. Prioritisation of Compounds for 3CL(pro) Inhibitor Development on SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Molecules. 2021;26:3003. doi: 10.3390/molecules26103003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prajapati J., Patel R., Goswami D., Saraf M., Rawal R.M. Sterenin M as a potential inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 main protease identified from MeFSAT database using molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation and binding free energy calculation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021;135:104568. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uniyal A., Mahapatra M.K., Tiwari V., Sandhir R., Kumar R. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease: Structure based virtual screening, in silico ADMET studies and molecular dynamics simulation for identification of potential inhibitors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020;4:32. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1848636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ram T.S., Munikumar M., Raju V.N., Devaraj P., Boiroju N.K., Hemalatha R., Prasad P.V.V., Gundeti M., Sisodia B.S., Pawar S., et al. In silico evaluation of the compounds of the ayurvedic drug, AYUSH-64, for the action against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2021.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabbah D.A., Hajjo R., Bardaweel S.K., Zhong H.A. An Updated Review on SARS-CoV-2 Main Proteinase (M(Pro)): Protein Structure and Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021;21:442–460. doi: 10.2174/1568026620666201207095117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Vivo M., Masetti M., Bottegoni G., Cavalli A. Role of Molecular Dynamics and Related Methods in Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:4035–4061. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumari R., Kumar R., Lynn A. g_mmpbsa—A GROMACS Tool for High-Throughput MM-PBSA Calculations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54:1951–1962. doi: 10.1021/ci500020m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong-Sam A., Wang Y.F., Zhang Y., Ghosh A.K., Harrison R.W., Weber I.T. Drug Resistance Mutation L76V Alters Nonpolar Interactions at the Flap-Core Interface of HIV-1 Protease. ACS Omega. 2018;3:12132–12140. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b01683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olajuyigbe F., Demitri N., Geremia S. Investigation of 2-Fold Disorder of Inhibitors and Relative Potency by Crystallizations of HIV-1 Protease in Ritonavir and Saquinavir Mixtures. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011;11:4378–4385. doi: 10.1021/cg200514z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T.N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I.N., Bourne P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim S., Chen J., Cheng T., Gindulyte A., He J., He S., Li Q., Shoemaker B.A., Thiessen P.A., Yu B., et al. PubChem 2019 update: Improved access to chemical data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D1102–D1109. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) 2018.0. Chemical Computing Group ULC; Montreal, QC, Canada: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu W., He X., Vanommeslaeghe K., MacKerell A.D., Jr. Extension of the CHARMM General Force Field to sulfonyl-containing compounds and its utility in biomolecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2012;33:2451–2468. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pronk S., Pall S., Schulz R., Larsson P., Bjelkmar P., Apostolov R., Shirts M.R., Smith J.C., Kasson P.M., van der Spoel D., et al. GROMACS 4.5: A high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:845–854. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Hess B., Groenhof G., Mark A.E., Berendsen H.J. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang J., MacKerell A.D., Jr. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem. 2013;34:2135–2145. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boonstra S., Onck P.R., Giessen E. CHARMM TIP3P Water Model Suppresses Peptide Folding by Solvating the Unfolded State. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:3692–3698. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b01316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mooers B.H.M. Shortcuts for faster image creation in PyMOL. Protein Sci. 2020;29:268–276. doi: 10.1002/pro.3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Schrödinger, LLC.; New York, NY, USA: DeLano Scientific; South San Francisco, CA, USA: 2020. Version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The structure models and simulation trajectories are available upon request (sangdunchoi@ajou.ac.kr). All remaining data are contained within the manuscript.