Key Points

Question

How do school-based vision programs affect academic performance among students needing eyeglasses?

Findings

This cluster randomized clinical trial found that a school-based vision program improved students’ reading scores over 1 year, especially girls, those in special education, and students in the lowest quartile at baseline. A sustained benefit was not observed over 2 years.

Meaning

School-based vision programs may help children improve academic performace by providing eye examinations and eyeglasses.

Abstract

Importance

Uncorrected refractive error in school-aged children may affect learning.

Objective

To assess the effect of a school-based vision program on academic achievement among students in grades 3 to 7.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cluster randomized clinical trial was conducted in Baltimore City Public Schools during school years from 2016 to 2019 among 2304 students in grades 3 to 7 who received eye examinations and eyeglasses.

Intervention

Participating schools were randomized 1:1:1 to receive eye examinations and eyeglasses during 1 of 3 school years (2016-2017, 2017-2018, and 2018-2019).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was 1-year intervention impact, measured by effect size (ES), defined as the difference in score on an academic test (i-Ready or Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers tests on reading and mathematics) between intervention and control groups measured in SD units, comparing cohort 1 (intervention) with cohorts 2 and 3 (control) at the end of program year 1 and comparing cohort 2 (intervention) with cohort 3 (control) at the end of program year 2. The secondary outcome was 2-year intervention impact, comparing ES in cohort 1 (intervention) with cohort 3 (control) at the end of program year 2. Hierarchical linear modeling was used to assess the impact of the intervention. Analysis was performed on an intention-to-treat basis.

Results

Among the 2304 students included in the study, 1260 (54.7%) were girls, with a mean (SD) age of 9.4 (1.4) years. The analysis included 964 students (41 schools) in cohort 1, 775 students (41 schools) in cohort 2, and 565 students (38 schools) in cohort 3. There were 1789 Black students (77.6%), 388 Latinx students (16.8%), and 406 students in special education (17.6%). There was an overall 1-year positive impact (ES, 0.09; P = .02) as assessed by the i-Ready reading test during school year 2016-2017. Positive impact was also observed among female students (ES, 0.15; P < .001), those in special education (ES, 0.25; P < .001), and students who performed in the lowest quartile at baseline (ES, 0.28; P < .001) on i-Ready reading and among students in elementary grades on i-Ready mathematics (ES, 0.03; P < .001) during school year 2016-2017. The intervention did not show a sustained impact at 2 years or on Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers testing.

Conclusions and Relevance

Students in grades 3 to 7 who received eyeglasses through a school-based vision program achieved better reading scores. Students had improved academic achievement over 1 year; however, a sustained impact was not observed after 2 years.

Trial Registration

The Registry of Efficacy and Effectiveness Studies Identifier: 1573.1v1

This cluster randomized clinical trial assesses the effect of a school-based vision program on academic achievement among students in grades 3 to 7.

Introduction

The magnitude of uncorrected visual impairment due to refractive error in school-age children is substantial; corrective eyeglasses provide a simple solution. Failing a vision screening test is often the first indication of abnormal vision, prompting referral to an eye care clinician.1 However, only 5% to 50% of children who fail screening tests receive follow-up care.2,3,4,5 These rates are especially alarming in high-poverty neighborhoods, where vision problems are more than double the national average and students face greater difficulties with access to care.6,7,8,9,10 The advent of school-based vision programs (SBVPs) offers an opportunity to improve access to care by providing services, including provision of eyeglasses, directly in schools.

Because schools, among other entities, including families and faith-based groups, are responsible for children’s academic success,11 it is logical to engage them in addressing students’ vision needs. Although SBVPs have demonstrated success in connecting children who fail vision screening tests with eye examinations,12 to our knowledge, little is known about whether provision of eyeglasses as part of programs impacts academic success. Although previous studies have shown that provision of eyeglasses improved students’ classroom behavior and the probability of passing academic tests in reading and mathematics, they were limited by study design, population, and setting.13,14,15,16 A clear demonstration of the academic impact of SBVPs has not been made in the United States, to our knowledge.

Vision for Baltimore (V4B) is a citywide SBVP for students attending Baltimore City elementary and middle schools. We aimed to assess the impact of V4B’s school-based vision services, including provision of eyeglasses to students who needed them, on student academic achievement in English language arts (herein referred to as reading) and mathematics.

Methods

Study Design

This cluster randomized clinical trial was conducted in Baltimore City Public Schools during the school years (SYs) from 2016 to 2019 as part of a citywide SBVP. Institutional review board approval was obtained from Johns Hopkins University and Baltimore City Public Schools, and this study was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki tenets.17 The trial was registered at the Registry of Efficacy and Effectiveness Studies (1573.1v1) (trial protocol in Supplement 1).

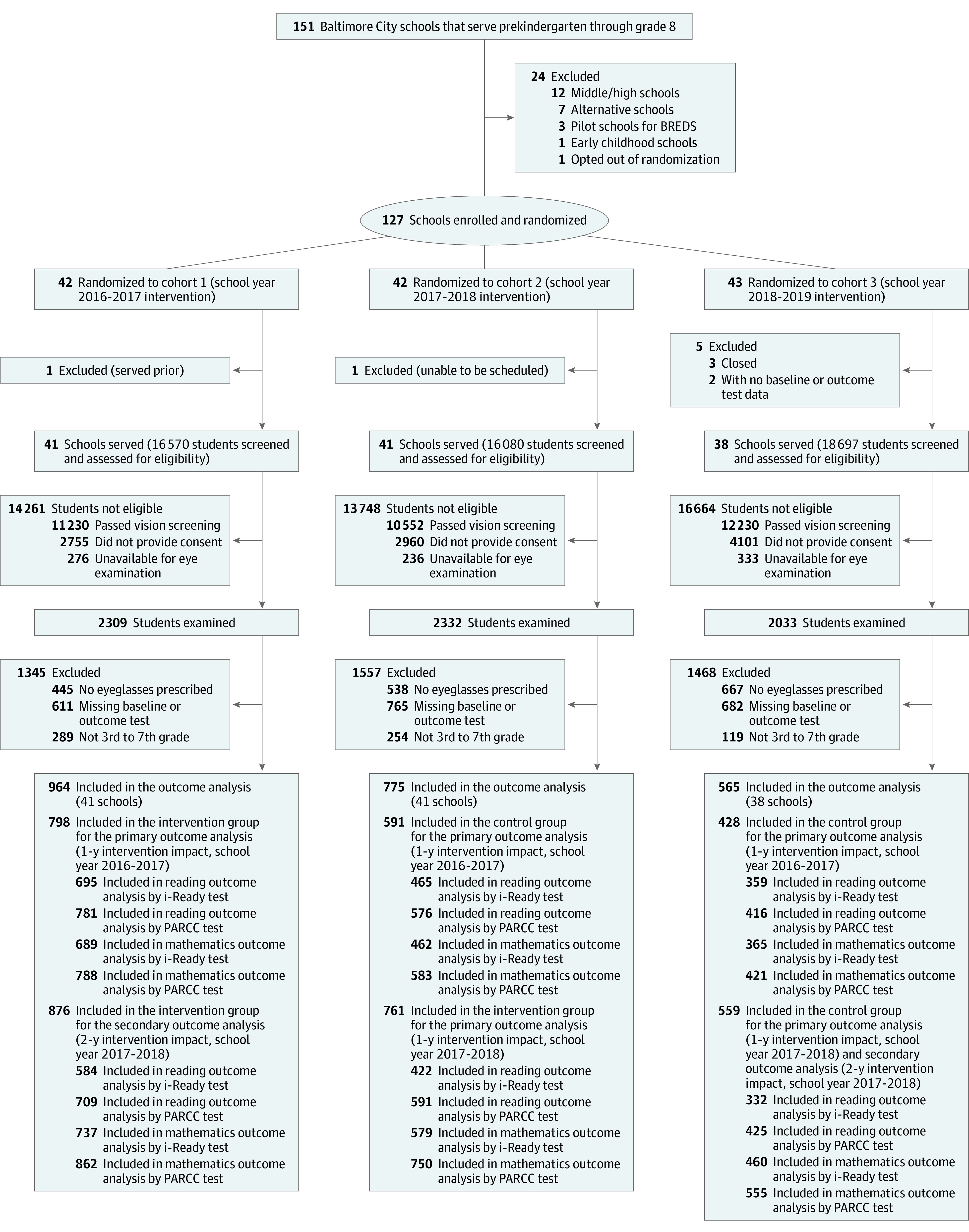

Baltimore City Public Schools included 151 schools that serve prekindergarten through grade 8. There were 127 schools enrolled and randomized into the study after excluding 24 schools that did not meet study eligibility (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Vision for Baltimore Participant Flow Diagram.

BREDS indicates Baltimore Reading and Eye Disease Study; PARCC, Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers.

Cluster randomization was stratified based on charter school status, school type (elementary, middle, or prekindergarten through grade 8), previous participation by some students in the Baltimore Reading and Eye Disease Study (BREDS), a principal component score based on school-level sex, race/ethnicity, prior achievement, special education (SPED) status, English language learner status, eligibility for free and reduced-price meals, and whether the school had more than 25% Latinx students. Schools in each stratum were allocated with a 1:1:1 ratio into 1 of 3 study cohorts using block randomization. Cohorts 1, 2, and 3 received V4B interventions in the first (SY 2016-2017), second (SY 2017-2018), and third (SY 2018-2019) program years, respectively.

Intervention and Implementation

Vision for Baltimore services included vision screenings, eye examinations, and eyeglasses, if needed. Screenings were conducted for all students.12 Students who failed the screening test were provided a 2-sided consent form offering an eye examination and research participation. Signed parental consent was required for eye examinations; after providing consent for the examination, parents could opt out of participating in the research via a check box on the consent form.

A mobile eye clinic from Vision To Learn, a project partner, visited each school. Eye examinations were conducted by licensed optometrists after parents provided consent. Students who needed eyeglasses selected frames at the examination. Eyeglasses were manufactured by Warby Parker and dispensed to students at school approximately 2 to 4 weeks after the examination. Students were provided replacement eyeglasses as needed within 1 year of their prescription. The costs of the eyeglasses were covered by the program. Vision for Baltimore staff provided implementation support to schools throughout the study.

Measurements and Outcomes

Academic Performance and Demographic Data

The academic testing outcomes were reading and mathematics scores on the i-Ready test and the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) test. i-Ready, a standardized test given 3 times per year for students in grades 1 through 8, monitors academic progress in reading and mathematics. PARCC, a Maryland state-mandated test, is administered each spring to students in grades 3 through 8. Data on individual student test scores for SY 2015-2016 through SY 2017-2018, student demographic characteristics, and education status, including birthdate, grade, sex, race, ethnicity, SPED status, and English language learner status, were obtained from Baltimore City Public Schools.

Eye Examination Data

Presenting visual acuity was measured monocularly using an electronic acuity testing monitor (20/20 Vision; Canela Software) located 2.4 m from the examination chair. Students were tested with correction if wearing eyeglasses. Presenting visual acuity was the smallest line with at least 3 optotypes identified. Children underwent noncycloplegic autorefraction (RC-5000 Advanced Auto Refactor; Tomey Corporation) measurement followed by noncycloplegic manifest refraction.

Refractive error was determined based on the final lens prescription in the eye with better presenting visual acuity and was categorized as hyperopia (at least 0.50-diopter [D] spherical equivalent [SE]), myopia (at least −0.50-D SE), and emmetropia (between −0.50-D and 0.50-D SE). Astigmatism was defined as 1.00 D-cylindrical power or greater.

Outcome Measures

Program effect size (ES) was defined as the difference in score on a particular academic test between the intervention and control groups, measured in SD units. The primary study outcome was the 1-year intervention impact, measured by ES, comparing cohort 1 (intervention) with cohorts 2 and 3 (control) at the end of the first program year (SY 2016-2017) and comparing cohort 2 (intervention) with cohort 3 (control) at the end of the second program year (SY 2017-2018). The secondary outcome was the 2-year intervention impact, measured by comparing cohort 1 (intervention) with cohort 3 (control) at the end of the second program year (SY 2017-2018) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Randomization, Intervention, and Control Groups.

Baseline Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) included spring 2016 PARCC or fall 2016 i-Ready scores when PARCC scores were missing. Baseline i-Ready included fall 2016 i-Ready scores.

Student Participants and Eligibility

Students were included in the analytic sample if they failed the vision screening test, completed the eye examination, and opted into the study. Students were excluded for any of the following: (1) eyeglasses were not prescribed, (2) they had no baseline standardized test scores prior to program implementation or postintervention scores on any test, and (3) they were not in grades 3 to 7 when they received the intervention.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Grade levels were categorized as elementary school (grades 3-5) and middle school (grades 6 and 7). Students with the lowest 25% baseline performance on each test were defined as students who performed in the lowest quartile (SPLQ) at baseline. The school attrition rate, defined as the number of schools in a cohort at the time of outcome divided by the number of schools assigned to cohort at baseline, was used to assess the loss of entire schools from the analytic sample due to closure or not having results for a specific test. We used the baseline performance at randomization to avoid any sample contamination between randomization and time-lagged baseline. Hierarchical linear modeling was used to assess the impact of the V4B intervention on academic performance. Students were nested within schools in which they received the intervention. The models analyzed program effects on each academic test outcome separately, controlling for grade level and baseline achievement at student level, as well as stratifying variables used in randomization at the school level. Hierarchical linear modeling was used to examine intervention effects for various student subgroups (sex, grade level, SPED status, and baseline achievement) by including interaction terms in the model. The Hedges g ES18 and 95% CIs and 99% CIs19 were calculated. Given the large number of comparisons tested in the analyses of differential treatment effects, multiple comparison corrections were applied using the Bonferroni procedure. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using R statistical software, version 4.0.0 (R Group for Statistical Computing)20 and the lmer package.21

Results

Baseline Characteristics

School Characteristics

Forty-two schools were randomized to cohorts 1 and 2, and 43 schools were randomized to cohort 3 (Figure 1). The analytic sample included 120 schools; school-level characteristics are shown in eTable 1 in Supplement 2. The overall school attrition rate ranged from 6.3% (8 of 127) to 23.5% (20 of 85). The differential attrition rates between intervention and control schools ranged between 1.8% (23.3% [10 of 43] for the control group compared with 21.4% [9 of 42] for the intervention group) and 11.6% (14.0% [6 of 43] for the control group compared with 2.4% [1 of 42] for the intervention group), depending on the outcome analyzed (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Student Characteristics

The analytic sample included 2304 students (1044 boys [45.3%] and 1260 girls [54.7%]; mean [SD] age of 9.4 [1.4] years; retention rate by cohort presented in eTable 3 in Supplement 2) who were mostly Black (1789 [77.6%]), Latinx (388 [16.8%]), and White (432 [18.8%]), with some students self-identifying as more than 1 race/ethnicity. A total of 406 students (17.6%) were in SPED, and 204 (8.9%) were English language learners. No statistically significant demographic differences were observed between cohorts (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Baseline student characteristics by intervention outcome period are presented in Table 1. Students in the intervention and control groups had baseline standardized scores that were less than 0.25 SDs apart, a standard cutoff in education for comparable groups (eTable 5 in Supplement 2).

Table 1. Baseline Student-Level Characteristics by Outcome Measure Period.

| Characteristic | 1-y Intervention impact, Students, No. (%)a | 2-y Intervention impact on SY 2017-2018, Students, No. (%)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SY 2016-2017 | SY 2017-2018 | |||||

| Intervention, cohort 1 (n = 798) | Control, cohorts 2 and 3 (n = 1019) | Intervention, cohort 2 (n = 761) | Control, cohort 3 (n = 559) | Intervention, cohort 1 (n = 876) | Control, cohort 3 (n = 559) | |

| Race/ethnicityb | ||||||

| Black | 624 (78.2) | 792 (77.7) | 576 (75.7) | 443 (79.2) | 685 (78.2) | 443 (79.2) |

| White | 131 (16.4) | 200 (19.6) | 162 (21.3) | 105 (18.8) | 146 (16.7) | 105 (18.8) |

| Latinx | 122 (15.3) | 178 (17.5) | 136 (17.9) | 97 (17.4) | 143 (16.3) | 97 (17.4) |

| Asian | 17 (2.1) | 10 (1.0) | 8 (1.1) | 2 (0.4) | 20 (2.3) | 2 (0.4) |

| Female | 423 (53.0) | 596 (58.5) | 430 (56.5) | 318 (56.9) | 461 (52.6) | 318 (56.9) |

| English language learner | 63 (7.9) | 78 (7.7) | 64 (8.4) | 56 (10.0) | 77 (8.8) | 56 (10.0) |

| Special education | 145 (18.2) | 172 (16.9) | 128 (16.8) | 103 (18.4) | 154 (17.6) | 103 (18.4) |

| Eye examination findings | ||||||

| Wearing eyeglasses at baseline | 34 (4.3) | 33 (3.2) | 2 (0.3) | 42 (7.5) | 34 (3.9) | 42 (7.5) |

| Refractive error | ||||||

| Emmetropia | 198 (24.8) | 231 (22.7) | 212 (27.9) | 101 (18.1) | 227 (25.9) | 101 (18.1) |

| Hyperopia | 101 (12.7) | 109 (10.7) | 96 (12.6) | 60 (10.7) | 129 (14.7) | 60 (10.7) |

| Myopia | 499 (62.5) | 679 (66.6) | 453 (59.5) | 398 (71.2) | 520 (59.4) | 398 (71.2) |

| Astigmatism | 321 (40.2) | 364 (35.7) | 276 (36.3) | 222 (39.7) | 372 (42.5) | 222 (39.7) |

Abbreviation: SY, school year.

The numbers of students in each intervention and control group reflected all students who were included in at least 1 academic test outcome analysis; the numbers may differ from the baseline academic equivalence estimates (eTable 5 in Supplement 2).

Race/ethnicity was not mutually exclusive, and students may have self-classified as more than 1 race/ethnicity. Percentages may sum to more than 100%.

Overall Intervention Impact on Academic Outcomes

The primary and secondary outcome measures are shown in Table 2. At 1 year, there was a positive impact on the i-Ready reading score (ES, 0.09; P = .02) during SY 2016-2017. A similar positive impact on i-Ready reading scores was observed during SY 2017-2018 (ES, 0.12; P = .09) and with PARCC test scores during SY 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 (SY 2016-2017: ES, 0.04; P = .31; SY 2017-2018: ES, 0.04; P = .59), although these were not statistically significant. For the 1-year mathematics intervention impact, no positive impact was observed during SY 2016-2017. A positive impact was found with both i-Ready and PARCC during SY 2017-2018 (i-Ready: ES, 0.09; P = .07; PARCC: ES, 0.10; P = .11), although neither was statistically significant.

Table 2. 1-Year and 2-Year Intervention Impact on Academic Outcomes for All Studentsa.

| Outcome period, subject, and test | Schools, No. | Students, No. | Academic outcome test scores | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | Mean difference (SE) | Effect sizeb | P value | 95% CI | 99% CI | |||

| 1-y Intervention impact | |||||||||

| SY 2016-2017 | |||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||

| i-Ready | 107 | 1519 | 513.71 | 518.78 | 5.07 (2.11) | 0.09 | .02c | 0.01 to 0.17 | −0.01 to 0.19 |

| PARCC | 118 | 1773 | 697.53 | 698.92 | 1.39 (1.37) | 0.04 | .31 | −0.04 to 0.12 | −0.06 to 0.14 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||

| i-Ready | 106 | 1516 | 448.24 | 448.15 | −0.09 (1.23) | 0.00 | .94 | −0.10 to 0.10 | −0.13 to 0.13 |

| PARCC | 119 | 1792 | 728.53 | 728.57 | 0.04 (1.21) | 0.00 | .97 | −0.19 to 0.19 | −0.25 to 0.25 |

| SY 2017-2018 | |||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||

| i-Ready | 65 | 754 | 532.27 | 540.12 | 7.85 (4.56) | 0.12 | .09 | −0.02 to 0.26 | −0.06 to 0.30 |

| PARCC | 78 | 1016 | 701.99 | 703.22 | 1.23 (2.24) | 0.04 | .59 | −0.10 to 0.18 | −0.15 to 0.23 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||

| i-Ready | 66 | 1039 | 449.86 | 453.36 | 3.50 (1.87) | 0.09 | .07 | −0.01 to 0.19 | −0.04 to 0.22 |

| PARCC | 79 | 1305 | 731.64 | 734.76 | 3.12 (1.91) | 0.10 | .11 | −0.02 to 0.22 | −0.06 to 0.26 |

| 2-y Intervention impact | |||||||||

| SY 2017-2018 | |||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||

| i-Ready | 67 | 916 | 529.64 | 534.49 | 4.85 (4.01) | 0.08 | .23 | −0.05 to 0.22 | −0.09 to 0.25 |

| PARCC | 78 | 1134 | 698.83 | 697.54 | −1.29 (1.75) | −0.04 | .46 | −0.14 to 0.06 | −0.18 to 0.10 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||

| i-Ready | 69 | 1197 | 449.51 | 452.45 | 2.94 (2.29) | 0.08 | .20 | −0.04 to 0.20 | −0.08 to 0.24 |

| PARCC | 79 | 1417 | 724.19 | 724.32 | 0.13 (2.09) | 0.00 | .95 | −0.11 to 0.11 | −0.15 to 0.15 |

Abbreviations: PARCC, Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers; SY, school year.

The models adjusted for student grade level (3-7), prior achievement (testing scores), and blocking variables used in randomization (charter school status, school type, pilot study participation, school proportion of low-income and Black students, and whether the school served more than 25% Latinx students). Effect size estimates presented are model-adjusted estimates. The analytic sample included 120 schools. Different analyses had different numbers of students and school samples owing to the availability of baseline and postintervention tests.

The difference in score on a particular academic test between the intervention and control groups measured in SD units.

Statistically significant at 2-sided P < .05 level.

At 2 years, a positive intervention impact was observed on i-Ready reading scores (ES, 0.08; P = .23) and mathematics scores (ES, 0.08; P = .20); however, these were not statistically significant. No impact was seen on PARCC reading scores (ES, −0.04; P = .46) or mathematics scores (ES, 0.00; P = .95).

Intervention Impact on Academic Outcomes by Student Characteristics

One-year and 2-year intervention impacts were analyzed by sex, grade level, SPED status, and baseline achievement (Table 3). After application of the Bonferroni correction, a statistically significant positive 1-year intervention impact was observed with the reading i-Ready score for girls (ES, 0.15; P < .001) but not for boys (ES, 0.01; P = .48).

Table 3. 1-Year and 2-Year Intervention Impacts on Academic Outcomes by Student Characteristics.

| Subject and test | 1-y Intervention impacta | 2-y Intervention impact on SY 2017-2018a | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SY 2016-2017 | SY 2017-2018 | ||||||||||||||

| Mean difference, Score | Effect sizeb | P value | 95% CI | 99% CI | Mean difference, Score | Effect sizeb | P value | 95% CI | 99% CI | Mean difference, Score | Effect sizeb | P value | 95% CI | 99% CI | |

| Sex | |||||||||||||||

| Female | |||||||||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 8.73 | 0.15c | <.001 | 0.06 to 0.24 | 0.03 to 0.27 | 5.44 | 0.09 | ≥.99 | −12.62 to 12.80 | −16.61 to 16.80 | 6.39 | 0.10 | ≥.99 | −14.02 to 14.22 | −18.46 to 18.66 |

| PARCC | 2.44 | 0.08 | ≥.99 | −11.22 to 11.38 | −14.77 to 14.93 | 1.02 | 0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.21 to 4.27 | −5.54 to 5.60 | −0.18 | −0.01 | ≥.99 | −1.42 to 1.40 | −1.87 to 1.85 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 1.03 | 0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.21 to 4.27 | −5.54 to 5.60 | 1.62 | 0.04 | ≥.99 | −5.61 to 5.69 | −7.39 to 7.47 | 2.22 | 0.06 | ≥.99 | −8.41 to 8.53 | −11.08 to 11.20 |

| PARCC | 0.55 | 0.02 | ≥.99 | −2.80 to 2.84 | −3.69 to 3.73 | 4.07 | 0.13 | ≥.99 | −18.23 to 18.49 | −24.00 to 24.26 | 3.30 | 0.11 | .96 | −3.80 to 4.02 | −5.03 to 5.25 |

| Male | |||||||||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 0.36 | 0.01 | .48 | −0.02 to 0.04 | −0.03 to 0.05 | 9.00 | 0.14 | ≥.99 | −19.63 to 19.91 | −25.85 to 26.13 | 2.31 | 0.04 | ≥.99 | −5.61 to 5.69 | −7.39 to 7.47 |

| PARCC | 0.76 | 0.02 | ≥.99 | −2.80 to 2.84 | −3.69 to 3.73 | 1.19 | 0.04 | ≥.99 | −5.61 to 5.69 | −7.39 to 7.47 | −2.02 | −0.06 | ≥.99 | −8.53 to 8.41 | −11.20 to 11.08 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | −1.52 | −0.05 | ≥.99 | −7.11 to 7.01 | −9.33 to 9.23 | 5.29 | 0.14 | ≥.99 | −19.63 to 19.91 | −25.85 to 26.13 | 3.70 | 0.10 | ≥.99 | −14.02 to 14.22 | −18.46 to 18.66 |

| PARCC | −0.56 | −0.02 | ≥.99 | −2.84 to 2.80 | −3.73 to 3.69 | 1.66 | 0.05 | ≥.99 | −7.01 to 7.11 | −9.23 to 9.33 | −3.67 | −0.12 | ≥.99 | −17.07 to 16.83 | −22.40 to 22.16 |

| Grade level | |||||||||||||||

| Elementary grades | |||||||||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 6.14 | 0.11 | .48 | −0.19 to 0.41 | −0.28 to 0.50 | 8.40 | 0.13 | ≥.99 | −18.23 to 18.49 | −24.00 to 24.26 | 6.75 | 0.11 | ≥.99 | −15.43 to 15.65 | −20.31 to 20.53 |

| PARCC | 1.86 | 0.06 | ≥.99 | −8.41 to 8.53 | −11.08 to 11.20 | 1.01 | 0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.21 to 4.27 | −5.54 to 5.60 | 0.17 | 0.01 | ≥.99 | −1.40 to 1.42 | −1.85 to 1.87 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 1.11 | 0.03c | <.001 | 0.01 to 0.05 | 0.01 to 0.05 | 3.54 | 0.09 | ≥.99 | −12.62 to 12.80 | −16.62 to 16.80 | 4.38 | 0.12 | ≥.99 | −16.83 to 17.07 | −22.16 to 22.40 |

| PARCC | 0.17 | 0.01 | ≥.99 | −1.40 to 1.42 | −1.85 to 1.87 | 5.57 | 0.18 | .96 | −6.22 to 6.58 | −8.23 to 8.59 | 1.13 | 0.04 | ≥.99 | −5.61 to 5.69 | −7.39 to 7.47 |

| Middle grades | |||||||||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | −0.59 | −0.01 | .48 | −0.04 to 0.02 | −0.05 to 0.03 | 4.88 | 0.08 | ≥.99 | −11.22 to 11.38 | −14.77 to 14.93 | 1.33 | 0.02 | ≥.99 | −2.80 to 2.84 | −3.69 to 3.73 |

| PARCC | 0.97 | 0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.21 to 4.27 | −5.54 to 5.60 | 1.18 | 0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.21 to 4.27 | −5.54 to 5.60 | −2.51 | −0.08 | ≥.99 | −11.38 to 11.22 | −14.93 to 14.77 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | −6.91 | −0.21 | ≥.99 | −29.87 to 29.45 | −39.19 to 38.77 | 2.97 | 0.08 | ≥.99 | −11.22 to 11.38 | −14.77 to 14.93 | 1.56 | 0.04 | ≥.99 | −5.61 to 5.69 | −7.39 to 7.47 |

| PARCC | −0.44 | −0.01 | ≥.99 | −1.42 to 1.40 | −1.87 to 1.85 | 1.01 | 0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.21 to 4.27 | −5.54 to 5.60 | −0.76 | −0.02 | ≥.99 | −2.84 to 2.80 | −3.73 to 3.69 |

| Special education status | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | |||||||||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 13.87 | 0.25c | <.001 | 0.10 to 0.40 | 0.06 to 0.44 | 15.41 | 0.24 | ≥.99 | −33.66 to 34.14 | −44.31 to 44.79 | 14.50 | 0.23 | ≥.99 | −32.25 to 32.71 | −42.46 to 42.92 |

| PARCC | 2.79 | 0.09 | ≥.99 | −12.62 to 12.80 | −16.62 to 16.80 | −1.52 | −0.04 | ≥.99 | −5.69 to 5.61 | −7.47 to 7.39 | −1.07 | −0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.27 to 4.21 | −5.60 to 5.54 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | −0.79 | −0.02 | ≥.99 | −2.84 to 2.80 | −3.73 to 3.69 | 1.83 | 0.05 | ≥.99 | −7.01 to 7.11 | −9.23 to 9.33 | 4.81 | 0.13 | ≥.99 | −18.23 to 18.49 | −24.00 to 24.26 |

| PARCC | 0.60 | 0.02 | ≥.99 | −2.80 to 2.84 | −3.69 to 3.73 | 4.62 | 0.15 | ≥.99 | −21.04 to 21.34 | −27.69 to 27.99 | 5.16 | 0.17 | ≥.99 | −23.84 to 24.18 | −31.39 to 31.73 |

| No | |||||||||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 3.32 | 0.06 | .48 | −0.10 to 0.22 | −0.15 to 0.27 | 5.17 | 0.08 | ≥.99 | −11.22 to 11.38 | −14.77 to 14.93 | 2.41 | 0.04 | ≥.99 | −5.61 to 5.69 | −7.39 to 7.47 |

| PARCC | 1.48 | 0.05 | ≥.99 | −7.01 to 7.11 | −9.23 to 9.33 | 1.62 | 0.05 | ≥.99 | −7.01 to 7.11 | −9.23 to 9.33 | −0.99 | −0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.27 to 4.21 | −5.60 to 5.54 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 0.06 | 0.00 | ≥.99 | −0.56 to 0.56 | −0.74 to 0.74 | 3.52 | 0.09 | ≥.99 | −12.62 to 12.80 | −16.62 to 16.80 | 2.49 | 0.07 | ≥.99 | −9.82 to 9.96 | −12.92 to 13.06 |

| PARCC | −0.05 | 0.00 | ≥.99 | −0.56 to 0.56 | −0.74 to 0.74 | 2.70 | 0.09 | ≥.99 | −12.62 to 12.80 | −16.62 to 16.80 | −1.00 | −0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.27 to 4.21 | −5.60 to 5.54 |

| Baseline achievement level | |||||||||||||||

| Students in lowest quartile | |||||||||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 15.54 | 0.28c | <.001 | 0.11 to 0.45 | 0.06 to 0.50 | 7.88 | 0.12 | ≥.99 | −16.83 to 17.07 | −22.16 to 22.40 | 10.27 | 0.17 | ≥.99 | −23.84 to 24.18 | −31.39 to 31.73 |

| PARCC | 3.17 | 0.10 | ≥.99 | −14.02 to 14.22 | −18.46 to 18.66 | 0.25 | 0.01 | ≥.99 | −1.40 to 1.42 | −1.85 to 1.87 | 0.95 | 0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.21 to 4.27 | −5.54 to 5.60 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 2.18 | 0.07 | ≥.99 | −9.82 to 9.96 | −12.92 to 13.06 | 2.46 | 0.06 | ≥.99 | −8.41 to 8.53 | −11.08 to 11.20 | 4.34 | 0.11 | ≥.99 | −15.43 to 15.65 | −20.31 to 20.53 |

| PARCC | 0.09 | 0.00 | ≥.99 | −0.56 to 0.56 | −0.74 to 0.74 | 6.31 | 0.20 | ≥.99 | −28.05 to 28.45 | −36.93 to 37.33 | 1.05 | 0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.21 to 4.27 | −5.54 to 5.60 |

| Students in 26th-100th percentile | |||||||||||||||

| Reading | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | 1.50 | 0.03 | .48 | −0.05 to 0.11 | −0.08 to 0.14 | 6.61 | 0.11 | ≥.99 | −15.43 to 15.65 | −20.31 to 20.53 | 2.44 | 0.04 | ≥.99 | −5.61 to 5.69 | −7.39 to 7.47 |

| PARCC | 1.18 | 0.04 | ≥.99 | −5.61 to 5.69 | −7.39 to 7.47 | 1.38 | 0.04 | ≥.99 | −5.61 to 5.69 | −7.39 to 7.47 | −1.72 | −0.05 | ≥.99 | −7.11 to 7.01 | −9.33 to 9.23 |

| Mathematics | |||||||||||||||

| i-Ready | −0.86 | −0.03 | ≥.99 | −4.27 to 4.21 | −5.60 to 5.54 | 3.48 | 0.09 | ≥.99 | −12.62 to 12.80 | −16.62 to 16.80 | 2.41 | 0.06 | ≥.99 | −8.41 to 8.53 | −11.08 to 11.20 |

| PARCC | 0.05 | 0.00 | ≥.99 | −0.56 to 0.56 | −0.74 to 0.74 | 1.93 | 0.06 | ≥.99 | −8.41 to 8.53 | −11.08 to 11.20 | −0.24 | −0.01 | ≥.99 | −1.42 to 1.40 | −1.87 to 1.85 |

Abbreviations: PARCC, Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers; SY, school year.

The models adjusted for student grade level (3-7), prior achievement (testing scores), and blocking variables used in randomization (charter school status, school type, pilot study participation, school proportion of low-income and Black students, and whether the school served more than 25% Latinx students). Effect size estimates presented are model-adjusted estimates.

The difference in score on a particular academic test between the intervention and control groups measured in SD units.

Statistically significant after Bonferroni correction at 2-sided P < .001 level, calculated by conducting a test to see if intervention × interaction = 0 after running the relevant model. Multiple comparison corrections were applied to P values using the Bonferroni procedure. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

For the 1-year intervention impact on i-Ready mathematics, a statistically significant impact was observed in elementary school grades (ES, 0.03; P < .001) but not middle school grades (ES, −0.21; P ≥ .99) during SY 2016-2017 (Table 3). No statistically significant outcome was found in SY 2017-2018 with 2-year intervention impact or with PARCC outcomes by grade level.

A positive 1-year intervention impact on reading by i-Ready score during SY 2016-2017 was found for SPED students (ES, 0.25; P < .001) but not for non-SPED students (ES, 0.06; P = .48) (Table 3). Similarly, for SPLQ at baseline, there was a positive 1-year intervention impact on reading by i-Ready score during SY 2016-2017 (ES, 0.28; P < .001). Such an impact was not observed for their counterparts with higher baseline achievement (ES, 0.03; P = .48). No statistically significant impact was observed by SPED or baseline achievement status with other 1-year or 2-year intervention outcomes.

Discussion

In this citywide, cluster randomized clinical study conducted in Baltimore, Maryland, students receiving SBVP interventions with eyeglasses achieved better scores than controls on i-Ready reading assessments over 1 year. Our findings highlighted that students with certain characteristics benefited more from the intervention. Over the course of 1 year, girls, SPED students, and those with SPLQ at baseline obtained higher scores on i-Ready reading, while students in elementary school grades achieved higher scores on i-Ready mathematics. The improved students’ academic achievements seen in the first year were not sustained at 2 years. Vision for Baltimore demonstrated success in identifying and correcting vision deficits for students in Baltimore, many of whom may have never previously accessed vision care.22

When evaluating the impact of an intervention, which for this study was provision of eyeglasses, on academic achievement, a 0.09 ES in reading is considered medium by benchmark standards; the 0.25 ES in some of our subgroup analyses would be considered large.23 The ESs are noteworthy by education standards given the randomized design and study size.23 It is important to compare the demonstrated benefit of school-based vision care with ES for widely used educational interventions.24,25,26 The overall ES of 0.09 in this study is larger than that for other common interventions, with the exception of tutoring (eFigure in Supplement 2). The effects for SPED students (ES, 0.25) and those with SPLQ at baseline (ES, 0.28) are comparable to those of tutoring for students performing below grade level, the most effective educational intervention known.24 Although this analysis measured impact only on academic achievement, the educational implications can be more far reaching, including the potential impact on attendance and behavior.

For PARCC, reliability estimates range from 0.90 to 0.92 for reading and 0.91 to 0.94 for mathematics27; for i-Ready, reliability estimates range from 0.85 to 0.86 for reading and 0.83 to 0.87 for mathematics.28 The yearly spring to spring gains on standardized tests for the grades included ranged from 0.23 to 0.60 SDs. The ES seen with eyeglasses would be additive to these expected gains. Because learning gains narrow in higher grades, a 0.09 ES becomes even more impactful for older students.23 We did not observe the same impact on PARCC testing as on i-Ready, which is designed to measure incremental changes more reliably than PARCC.

Our findings are supported by previous studies about SBVPs in elementary school populations. The i-Ready reading results (ES, 0.09) are similar to those of BREDS, a study that examined the impact of prescribing eyeglasses for low refractive error on individual reading assessments (ES, 0.16); however, BREDS did not focus specifically on students who failed vision screening tests.29 A review of the academic records of children in grades 1 through 5 in the Los Angeles Unified School District demonstrated a change in percentile ranking in mathematics and reading assessments from 1 year prior to 2 years after receiving eyeglasses.14 In another retrospective review of 349 students in kindergarten through grade 5 in the Philadelphia school district who received eyeglasses through a school-based program, students scoring in the satisfactory range at baseline were more likely to maintain scores during the same academic year; however, no benefit was noted for children performing in the inadequate or marginal category at baseline.13

To our knowledge, there has been 1 randomized study among students in the United States comparing screening alone vs screening plus eye examinations and eyeglasses that reported improved scores on Florida Comprehensive Achievement Tests16; however, substantial implementation challenges limit the interpretation of these results. A study among children in rural China also found positive effects on standardized mathematics tests of providing eyeglasses, yet with no assessment of reading performance.15 It is unclear why we did not observe the same benefit for mathematics across our study population, instead of only for students in elementary school grades on i-Ready. This finding may be associated with differences between the tests used in the United States and China or differences between rural Chinese students and an urban high-poverty population in Baltimore.

In subgroup analysis, we found a positive impact on i-Ready reading scores for students in SPED. A prior observational study explored the impact for students in SPED and reported that those receiving eyeglasses had significant improvements in classroom behavior; however, no standardized testing results were measured.30 Students in SPED suspected of having a vision problem are recommended to have a baseline eye examination prior to placement.31 Efforts should be made to improve mechanisms to ensure that such students receive the recommended eye care. In contrast to the Philadelphia study,13 our subgroup analysis demonstrated a larger benefit for children with SPLQ at baseline. The reasons for this difference may be that we studied younger students and used different assessments.

Our study showed benefit at 1 year that was not sustained after 2 years. The reasons for this may be that students may wear eyeglasses less over time or that the refractive correction may no longer be sufficient. A similar decrease in impact over time has been reported previously,16 as has decreased use of eyeglasses with time.32 Collectively, these findings underscore that for SBVPs to maximize impact, they must not only provide eyeglasses but also ensure mechanisms for monitoring wear, replacement, and connection to community eye care clinicians for long-term care.33

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths and limitations. The research study was performed in the context of a real-world SBVP involving more than 30 000 students. The randomized clinical design enabled the evaluation of 1- and 2-year impacts on reading and mathematics using i-Ready and PARCC.

There may have been variations in vision screenings and examinations that would not have occurred in a clinical trial setting. Although students were measured for best-corrected visual acuity with refraction, their vision was not remeasured after they received eyeglasses. The refractive error findings and visual acuity change with eyeglasses in relation to academic outcomes will be reported separately. We observed a decrease in eyeglasses prescription rates over time; however, the impact on academic outcome assessments was expected to be minimal given the balanced student characteristics across cohorts.

Data on individual eyeglass wear compliance were not collected, limiting further explorations of other factors associated with academic outcomes. Because the program operated throughout the school year, students may have been wearing eyeglasses for varying lengths of time before benchmark assessments. However, we maintained extensive engagement with schools because previous research demonstrated the positive impact of teacher reminders on students consistently wearing their eyeglasses.32 It is also possible that students may have lost or broken their eyeglasses. The program had an active system in which replacements were provided on request, but we may have missed students who did not report lost or broken eyeglasses.

The research sample may not be representative of the demographic characteristics of all students who failed vision screening tests owing to school-level attrition and the number of individual students consenting to participate in research. Study implementation may have underestimated the interventional impact based on an intention-to-treat analysis approach, as students were wearing eyeglasses for different durations depending on when they underwent eye examinations; it is also possible that not all students had received the intervention by the time they took standardized tests. There were 47.7% of students (1100) excluded from at least 1 outcome analysis owing to missing academic test data, largely associated with the approximately 30% student mobility rate in schools.34 We do not know the diagnoses for SPED students; however, most were likely to have high-incidence disabilities, such as specific learning disability and speech or language impairment, because these are the most common diagnoses in which students would still participate in standardized testing.

Finally, we were unable to examine impacts for children below third grade because we did not have available pretest data. Evaluating program effects for this age group would be important given the considerable interest in improving reading for students in early elementary school grades.

Conclusions

Based on our analyses, there was a positive impact of an SBVP on academic performance in reading, with a larger observed program effect on female students, those in elementary grades, SPED, and SPLQ at baseline. The study provides evidence that eyeglasses not only help children see more clearly but achieve more academically. These findings have potential relevance for policymakers and stakeholders interested in school-based vision care.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline School-Level Characteristics by Study Cohort

eTable 2. School Attrition Rate by Outcome Measure Period

eTable 3. Student Retention Rate by Outcome Measure Period and Cohort

eTable 4. Baseline Student-Level Characteristics by Study Cohort

eTable 5. Baseline Academic Test Outcome Equivalence

eFigure. Comparison of Effect Size for V4B i-Ready Reading at 1 Year vs Common Educational Interventions

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Yawn BP, Lydick EG, Epstein R, Jacobsen SJ. Is school vision screening effective? J Sch Health. 1996;66(5):171-175. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1996.tb06269.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yawn BP, Kurland M, Butterfield L, Johnson B. Barriers to seeking care following school vision screening in Rochester, Minnesota. J Sch Health. 1998;68(8):319-324. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb00592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mark H, Mark T. Parental reasons for non-response following a referral in school vision screening. J Sch Health. 1999;69(1):35-38. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1999.tb02341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimel LS. Lack of follow-up exams after failed school vision screenings: an investigation of contributing factors. J Sch Nurs. 2006;22(3):156-162. doi: 10.1177/10598405060220030601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frazier M, Kleinstein R.. Access and Barriers to Vision, Eye, and Health Care. Old Post Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganz ML, Xuan Z, Hunter DG. Prevalence and correlates of children’s diagnosed eye and vision conditions. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(12):2298-2306. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganz M, Xuan Z, Hunter DG. Patterns of eye care use and expenditures among children with diagnosed eye conditions. J AAPOS. 2007;11(5):480-487. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majeed M, Williams C, Northstone K, Ben-Shlomo Y. Are there inequities in the utilisation of childhood eye-care services in relation to socio-economic status? evidence from the ALSPAC cohort. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(7):965-969. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.134841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, Elliott MN, Saaddine JB, et al. Unmet eye care needs among U.S. 5th-grade students. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):55-58. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein JD, Andrews C, Musch DC, Green C, Lee PP. Sight-threatening ocular diseases remain underdiagnosed among children of less affluent families. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1359-1366. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luyten H, Merrell C, Tymms P. The contribution of schooling to learning gains of pupils in years 1 to 6. Sch Eff Sch Improv. 2017;28(3):374-405. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2017.1297312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milante RR, Guo X, Neitzel AJ, et al. Analysis of vision screening failures in a school-based vision program (2016-19). J AAPOS. 2021;25(1):29.e1-29.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2020.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hark LA, Thau A, Nutaitis A, et al. Impact of eyeglasses on academic performance in primary school children. Can J Ophthalmol. 2020;55(1):52-57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2019.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dudovitz RN, Sim MS, Elashoff D, Klarin J, Slusser W, Chung PJ. Receipt of corrective lenses and academic performance of low-income students. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(7):910-916. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma X, Zhou Z, Yi H, et al. Effect of providing free glasses on children’s educational outcomes in China: cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2014;349:g5740. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glewwe P, West KL, Lee J. The impact of providing vision screening and free eyeglasses on academic outcomes: evidence from a randomized trial in Title I elementary schools in Florida. J Policy Anal Manage. 2018;37(2):265-300. doi: 10.1002/pam.22043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedges LV. Distribution theory for Glass's estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Stat. 1981;6(2):107-128. doi: 10.3102/10769986006002107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altman DG, Bland JM. How to obtain the confidence interval from a P value. BMJ. 2011;343:d2090. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Accessed May 14, 2021. https://www.R-project.org/

- 21.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo X, Nguyen AM, Vongsachang H, et al. Refractive error findings in students who failed school-based vision screening. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2021;1-9. Published online July 22, 2021. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2021.1954664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraft MA. Interpreting effect sizes of education interventions. Educ Res. 2020;49(4):241-253. doi: 10.3102/0013189X20912798 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neitzel AJ, Lake C, Pellegrini M, Slavin RE. A synthesis of quantitative research on programs for struggling readers in elementary schools. Read Res Q. Published online March 2, 2021. doi: 10.1002/rrq.379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CREDO . Urban Charter School Study Report on 41 Regions. Stanford University; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Figlio D, Holden KL, Ozek U. Do students benefit from longer school days? regression discontinuity evidence from Florida's additional hour of literacy instruction. Econ Educ Rev. 2018;67:171-183. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC). Final technical report for 2018 administration. Accessed May 14, 2021. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED599198.pdf

- 28.National Center on Intensive Intervention . Academic progress monitoring tools chart. Accessed May 14, 2021. https://intensiveintervention.org/resource/academic-progress-monitoring-tools-chart

- 29.Slavin RE, Collins ME, Repka MX, et al. In plain sight: reading outcomes of providing eyeglasses to disadvantaged children. J Educ Stud Placed Risk. 2018;23(3):250-258. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2018.1477602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black SA, McConnell EL, McKerr L, et al. In-school eyecare in special education settings has measurable benefits for children’s vision and behaviour. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0220480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Handler SM, Fierson WM; Section on Ophthalmology; Council on Children with Disabilities; American Academy of Ophthalmology; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Association of Certified Orthoptists . Learning disabilities, dyslexia, and vision. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):e818-e856. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang AH, Guo X, Mudie LI, et al. Baltimore Reading and Eye Disease Study (BREDS): compliance and satisfaction with glasses usage. J AAPOS. 2019;23(4):207.e1-207.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2019.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shakarchi AF, Collins ME. Referral to community care from school-based eye care programs in the United States. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019;64(6):858-867. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maryland State Department of Education . Maryland State Department of Education Report Card. Accessed April 7, 2021. https://reportcard.msde.maryland.gov/Graphs/#ReportCards

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline School-Level Characteristics by Study Cohort

eTable 2. School Attrition Rate by Outcome Measure Period

eTable 3. Student Retention Rate by Outcome Measure Period and Cohort

eTable 4. Baseline Student-Level Characteristics by Study Cohort

eTable 5. Baseline Academic Test Outcome Equivalence

eFigure. Comparison of Effect Size for V4B i-Ready Reading at 1 Year vs Common Educational Interventions

Data Sharing Statement