Abstract

One hundred thirty-three strains of Pasteurella haemolytica of both biotypes (90 and 43 strains of biotypes A and T, respectively) and almost all the serotypes were subjected to ribotyping, random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis for epidemiological purposes. A total of 15 patterns recorded as ribotypes HA to HO were found for the P. haemolytica biotype A strains, with ribotypes HA, HC, and HD being encountered most often (66 strains [74%]); and 20 ribotypes, designated HA′ to HT′, that were clearly distinct from those observed for biotype A strains were observed for strains of biotype T. RAPD analysis generated a total of 44 (designated Rp1 to Rp44) and 15 (designated Rp1′ to Rp 15′) unique RAPD patterns for biogroup A and biogroup T, respectively. Analysis of the data indicated that a given combined ribotype-RAPD pattern could be observed for biotype A strains of different serotypes, whatever the zoological or geographic origin, whereas this was not the case for biotype T strains. PFGE appeared to be more efficient in strain discrimination since selected strains from various zoological or geographical origins harboring the same ribotype-RAPD group were further separated into unique entities.

Pasteurella haemolytica is a well-known pathogen of ruminants worldwide (10, 17, 23). Two biochemical types of this bacterial species are recognized and are designated biotypes A and T; the letters stand for arabinose or trehalose fermentation, respectively (1, 16). Another approach to the typing of strains of P. haemolytica is based upon serological properties, primarily an indirect hemagglutination assay with P. haemolytica capsular antigens. A total of 17 serotypes are now defined for the species (8, 26). Thus, each isolate of P. haemolytica is designated by a combination of its biotype and its serotype. In cattle, pasteurellosis mostly involves P. haemolytica A1 (10, 15, 17), whereas P. haemolytica A2, T3, T4, and T10 are responsible for ovine systemic pasteurellosis of feeding lambs (11, 19–21) or wild ruminants (18). In some instance, strains belonging to the same serotype have been found in various animal hosts, i.e., serotype A1 in bovine, ovine, or caprine hosts (15, 21) or T3 in wild ruminants such as chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra), and in ovine or caprine hosts (8, 9, 18, 20, 21, 23). On the basis of serotyping, these observations could suggest a zoological interspecies distribution of P. haemolytica, as found by Callan et al. (4). Recently, rRNA gene restriction analysis (ribotyping) and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis of strains of P. haemolytica have confirmed the distribution of specific clones (an intraspecific clonal distribution) in bovine or captive bighorn sheep herds (2, 5, 23). The purpose of the present study was an extensive epidemiological study of P. haemolytica strains isolated from various hosts in different geographic areas by ribotyping and RAPD analysis and comparison of the types obtained with those obtained by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and species confirmation.

The strains investigated in the present study are listed in Table 1. The study included a total of 133 P. haemolytica strains of the two biotypes (90 and 43 strains of biotypes A and T, respectively) and strains of almost all serotypes of the two biotypes, including the type strain CIP 103286. These strains were isolated in France, Hungary, the United Kingdom, or Sweden. Additionally, the type strains Pasteurella multocida subsp. multocida CIP 103286 and Citrobacter koseri CIP 105177 (kindly provided by F. Grimont, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) were used as controls. For routine use, the strains were grown at 36°C on brain heart infusion agar plates (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood (Biomérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Bacterial species identification or confirmation was assessed by observation of the colonial morphology and the Gram staining results, by oxidase and catalase reactions, and by a standardized micromethod performed with the 20NE API-Biomérieux system (API-Biomérieux).

TABLE 1.

Types obtained by ribotyping, RAPD analysis and PFGE of P. haemolytica isolates

| Biotype and sero-type | Strain no. | Ribo-type | RAPD type | PFGE type | Host | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biotype A | ||||||

| A1 | 1908 | HA | Rp1 | P1 | Bovine | France |

| 1924 | HA | Rp1 | P2 | Bovine | France | |

| 2439 | HA | Rp1 | P3 | Bovine | France | |

| 2961 | HA | Rp1 | P4 | Bovine | France | |

| 1899 | HA | Rp2 | P5 | Bovine | France | |

| 3331 | HA | Rp2 | P6 | Bovine | France | |

| 2965 | HA | Rp2 | NDa | Bovine | France | |

| 3179 | HA | Rp2 | ND | Bovine | France | |

| 126 | HA | Rp2 | P7 | Ovine | France | |

| 68s | HA | Rp2 | P8 | Ovine | France | |

| 1619 | HA | Rp3 | P9 | Bovine | France | |

| 41/94 | HA | Rp3 | P10 | Caprine | Hungary | |

| 78s | HA | Rp3 | P11 | Ovine | France | |

| 100s | HA | Rp3 | P12 | Ovine | France | |

| CCUG 24141 | HA | Rp5 | P13 | Ovine | Sweden | |

| 5/94 | HA | Rp8 | P14 | Ovine | Hungary | |

| 11/94 | HA | Rp9 | P15 | Ovine | Hungary | |

| 64 | HB | Rp6 | P16b | Ovine | France | |

| 75 | HB | Rp6 | P16 | Ovine | France | |

| 82 | HB | Rp6 | P17 | Ovine | France | |

| 98s | HC | Rp7 | P18 | Ovine | France | |

| 107s | HD | Rp4 | P19 | Ovine | France | |

| A2 | CCUG 408 | HA | Rp10 | P20 | Ovine | Sweden |

| 1/96 | HA | Rp10 | P21 | Caprine | Hungary | |

| CCUG 18142 | HA | Rp16 | P22 | Ovine | Sweden | |

| 96 | HA | Rp17 | P23 | Ovine | France | |

| 101 | HA | Rp17 | ND | Ovine | France | |

| 102 | HA | Rp17 | P24 | Ovine | France | |

| 2/91 | HA | Rp19 | P25 | Caprine | Hungary | |

| 73 | HB | Rp6 | P26 | Ovine | France | |

| CCUG 27373 | HC | Rp10 | P27 | Ovine | France | |

| CIP 103426T | HC | Rp11 | P28 | Ovine | United Kingdom | |

| 175 | HC | Rp13 | ND | Ovine | France | |

| 40s | HC | Rp15 | ND | Caprine | France | |

| 141 | HC | Rp18 | P29 | Ovine | France | |

| 172 | HC | Rp18 | P29 | Ovine | France | |

| 684P | HC | Rp19 | P30 | Chamois | France | |

| 727P | HC | Rp20 | ND | Chamois | France | |

| 684mV | HC | Rp21 | P31 | Chamois | France | |

| 30s | HE | Rp12 | ND | Caprine | France | |

| 23s | HE | Rp13 | P32 | Caprine | France | |

| 42s | HG | Rp14 | P33 | Ovine | France | |

| 20s | HF | Rp14 | P34 | Caprine | France | |

| A5 | 22s | HA | Rp22 | P35 | Ovine | France |

| 76s | HA | Rp22 | P35 | Ovine | France | |

| 129s | HA | Rp22 | P36 | Ovine | France | |

| 3/94 | HI | Rp23 | P37 | Ovine | Hungary | |

| 9/94 | HI | Rp23 | P37 | Ovine | Hungary | |

| 10/95 | HI | Rp23 | P37 | Ovine | Hungary | |

| A6 | 79s | HA | Rp24 | P38 | Ovine | France |

| 87s | HA | Rp24 | P39 | Ovine | France | |

| 155s | HA | Rp24 | ND | Ovine | France | |

| 103 | HA | Rp25 | P40 | Ovine | France | |

| 6/94 | HA | Rp27 | P41 | Ovine | Hungary | |

| 173 | HD | Rp26 | P42 | Ovine | France | |

| A7 | 12/94 | HA | Rp30 | P43 | Ovine | Hungary |

| 80 | HC | Rp28 | ND | Ovine | France | |

| 63 | HC | Rp29 | P44 | Ovine | France | |

| 105 | HC | Rp29 | P44 | Ovine | France | |

| 107 | HC | Rp29 | P44 | Ovine | France | |

| 112 | HC | Rp29 | P44 | Ovine | France | |

| A8 | 101s | HA | Rp31 | ND | Ovine | France |

| 102s | HA | Rp32 | P45 | Caprine | France | |

| 7/94 | HA | Rp35 | P46 | Ovine | Hungary | |

| 12/95 | HA | Rp35 | P47 | Ovine | Hungary | |

| 60s | HD | Rp34 | P48 | Ovine | France | |

| 138 | HD | Rp34 | P49 | Ovine | France | |

| 140 | HD | Rp34 | P49 | Ovine | France | |

| 113s | HJ | Rp33 | P50 | Ovine | France | |

| Biotype and sero-type | Strain no. | Ribo-type | RAPD type | PFGE type | Host | Location |

| A9 | 85s | HA | Rp36 | P51 | Ovine | France |

| 109s | HA | Rp36 | P51 | Ovine | France | |

| 115s | HA | Rp28 | P52 | Unknown | France | |

| 138s | HA | Rp28 | P53 | Unknown | France | |

| 125 | HD | Rp8 | P54 | Ovine | France | |

| 179 | HD | Rp37 | P55 | Ovine | France | |

| 180 | HK | Rp38 | P56 | Ovine | France | |

| A11 | 150s | HL | Rp39 | P57 | Ovine | France |

| 178s | HL | Rp39 | P57 | Ovine | France | |

| A12 | 88s | HA | Rp41 | P58 | Ovine | France |

| 91s | HA | Rp41 | P59 | Ovine | France | |

| 48s | HM | Rp40 | P60 | Ovine | France | |

| A13 | 1/94 | HN | Rp42 | P61 | Ovine | Hungary |

| 258s | HN | Rp42 | P62 | Ovine | France | |

| A16 | CIP 104773c | HA | Rp43 | P63 | Ovine | Hungary |

| A17 | S-135 | HO | Rp44 | P64 | Ovine | Hungary |

| 10/94 | HO | Rp44 | P65 | Ovine | Hungary | |

| Unknown A serotype | 139 | HC | Rp16 | P66 | Ovine | France |

| 984P | HC | Rp3 | P67 | Chamois | France | |

| 94s | HD | Rp13 | P68 | Caprine | France | |

| 105s | HG | Rp10 | P69 | Ovine | France | |

| Biotype T | ||||||

| T3 | 1205P | HA′ | Rp1′ | P1′ | Chamois | France |

| 1205T | HA′ | Rp1′ | P1′ | Chamois | France | |

| 1231P | HA′ | Rp1′ | P1′ | Chamois | France | |

| 1233T | HA′ | Rp1′ | P1′ | Chamois | France | |

| 1233P | HA′ | Rp1′ | ND | Chamois | France | |

| 1229T | HA′ | Rp1′ | P2′ | Chamois | France | |

| 81s | HB′ | Rp2′ | P3′ | Ovine | France | |

| 136s | HB′ | Rp2′ | P3′ | Ovine | France | |

| CIP 104865 | HC′ | Rp6′ | P4′ | Ovine | United Kingdom | |

| CIP 104866 | HC′ | Rp6′ | P5′ | Ovine | United Kingdom | |

| CIP 104864 | HD′ | Rp5′ | P6′ | Ovine | United Kingdom | |

| 139s | HE′ | Rp5′ | ND | Ovine | United Kingdom | |

| 158s | HF′ | Rp4′ | P7′ | Ovine | United Kingdom | |

| 97s | HG′ | Rp3′ | P8′ | Caprine | France | |

| T4 | 3P | HH′ | Rp7′ | P9′ | Chamois | France |

| 3N | HH′ | Rp7′ | ND | Chamois | France | |

| 3T | HH′ | Rp7′ | P9′ | Chamois | France | |

| 4N | HH′ | Rp7′ | P9′ | Chamois | France | |

| 4P | HH′ | Rp7′ | ND | Chamois | France | |

| 5P | HH′ | Rp7′ | ND | Chamois | France | |

| 5N | HH′ | Rp7′ | ND | Chamois | France | |

| 5T | HH′ | Rp7′ | P9′ | Chamois | France | |

| 6P | HH′ | Rp7′ | ND | Chamois | France | |

| 8840 | HH′ | Rp7′ | ND | Chamois | France | |

| 6T | HI′ | Rp7′ | P10′ | Chamois | France | |

| 10T | HI′ | Rp7′ | P11′ | Chamois | France | |

| 8P | HI′ | Rp8′ | P12′ | Chamois | France | |

| 10P | HI′ | Rp8′ | P13′ | Chamois | France | |

| 1P | HJ′ | Rp7′ | P14′ | Chamois | France | |

| 9P | HJ′ | Rp7′ | P15′ | Chamois | France | |

| 9T | HJ′ | Rp7′ | P16′ | Chamois | France | |

| 2T | HK′ | Rp9′ | P17′ | Chamois | France | |

| CIP 104867 | HL′ | Rp10′ | P18′ | Ovine | United Kingdom | |

| CIP 104868 | HL′ | Rp10′ | ND | Ovine | United Kingdom | |

| CIP 104869 | HL′ | Rp10′ | P19′ | Ovine | United Kingdom | |

| CIP 104870 | HM′ | Rp11′ | P20′ | Ovine | United Kingdom | |

| T10 | 25s | HN′ | Rp5′ | P21′ | Ovine | France |

| 82s | HO′ | Rp5′ | P22′ | Ovine | France | |

| 180s | HP′ | Rp12′ | ND | Ovine | France | |

| Unknown T serotype | 31P | HQ′ | Rp7′ | P23′ | Chamois | France |

| 92s | HR′ | Rp13′ | P24′ | Caprine | France | |

| 110s | HS′ | Rp14′ | P25′ | Caprine | France | |

| 103s | HT′ | Rp15′ | P26′ | Ovine | France |

ND, not determined.

Boldface indicates PFGE subgroups comprising more than a single strain.

Hungarian reference strain 236.

rRNA gene restriction analysis (ribotyping). (i) Enzymatic DNA restriction.

Bacterial genomic DNA treated with 50 μg of RNase (Merck) per ml was extracted and purified as described elsewhere (14), and 5 μg of total DNA was cleaved with 10 U of HindIII at 37°C for 4 h. Digestion was performed with half of the quantity of enzyme for 2 h, followed by the addition of the second half for a further 2 h. HindIII was selected on the basis of the information in the literature (5) and on the basis of preliminary experiments in which this enzyme gave sharp bands in terms of complete digestion as well as in terms of the number and/or distribution of the rRNA gene restriction patterns. The reaction was stopped by heating at 65°C for 10 min before separation of DNA restriction fragments on an 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose gel (SeaKem LE; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) in 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8, adjusted with glacial acetic acid]) for 16 h at 40 V.

(ii) Southern blotting.

DNA fragments were transferred to a neutral nylon membrane (MagnaGraph nylon membrane; Micron Separation Inc., Westboro, Mass.) with the Trans-Vac TE 80 vacuum blotter apparatus (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, Calif.), with 20× SSC (3 M NaCl plus 0.3 M sodium citrate [pH 7.0]) used as the transfer solution. The transferred DNA fragments were immobilized onto the membrane by UV cross-linking at 0.120 J/cm2 with the Fluo-Link apparatus (Bioblock, Illkirch, France).

(iii) Prehybridization and hybridization conditions.

Prehybridization was carried out in rolling tubes containing 50 ml of prehybridization fluid (2× SSC, 0.1% Ficoll, 0.1% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 0.1% glycine, 1 mg of heat-denatured salmon sperm DNA per ml) at 62.5°C for 2 h, followed by 16 h of hybridization at 62.5°C with 500 ng of heat-denatured acetylaminofluorene-labelled Escherichia coli 16S plus 23S rRNA per ml (the complete kit for hybridization and detection was purchased from Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) in 10 ml of hybridization fluid (2× SSC, 0.02% Ficoll, 0.02% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 0.02% glycine, 25 mM KH2PO4 [pH 8.0], 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% PEG 6000, 100 μg of heat-denatured salmon sperm DNA per ml). Washings and immunoenzymatic detection of hybrids were performed as recommended by the manufacturer.

(iv) DNA fragment size determination.

Images of the blots were captured on video for computer determination of the fragment sizes with the Taxotron program (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France). The molecular sizes of the different fragments were determined by interpolation from the sizes generated from Citrobacter koseri rRNA gene restriction fragments.

RAPD analysis.

For RAPD analysis, 0.25 μM a single arbitrary 10-mer RAPD primer (sequence, AACGCGCAAC) and 5 μl of 10 ng of diluted DNA of each strain per ml were added to a ready-to-use bead (Ready.to.go RAPD Analysis Beads [Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden]) containing AmpliTaq plus the Stoffel fragment (a highly thermostable recombinant DNA polymerase which lacks any intrinsic 5′-3′ exonuclease activity and which exhibits optimal activity over a broader range of magnesium concentrations), each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 0.4 mM, 3 mM MgCl2, 30 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 8.3), and 2.5 μg of bovine serum albumin in a 25-μl final reaction volume. RAPD amplification reactions were performed in the Progene thermal cycler apparatus (Techne, Cambridge, United Kingdom) with the following conditions: 1 cycle at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95°C for 1 min, 36°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min. RAPD products were resolved by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel in Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer at 3.5 V/cm for 3 h. The reaction conditions and the reproducibilities of the patterns were optimized by performing preliminary experiments in which six primers were evaluated. E. coli C1a DNA (provided in the Ready.to.go RAPD Analysis Beads kit) was used as a control and a molecular weight marker.

PFGE.

The relationships of the strains analyzed by ribotyping and RAPD analysis were independently evaluated by computer analysis. Among those with consistent positions, certain strains were chosen on the basis of zoological or geographical criteria for more extensive analysis by macrorestriction analysis by PFGE. Thus, 113 representative genomic DNAs of strains of P. haemolytica (80 strains of biotype A and 33 strains of biotype T) were prepared in 1% low-melting-temperature agarose (SeaPlaque GTG agarose; FMC BioProducts) plugs by a slight modification of the method described by Talon et al. (25). The DNA samples were digested in gel overnight at 37°C in 300 μl of the appropriate restriction buffer containing 10 U of SalI endonuclease (Eurogentec). Reaction conditions with SalI were optimized by performing preliminary experiments in which the rarely cutting enzymes SpeI, XbaI, and NotI were also evaluated. The digested DNAs were separated by PFGE in a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field with the CHEF DRIII apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). Samples were loaded in 1% molecular biology-grade agarose (FastLane; BioProducts) that had been dissolved in 0.5× TBE buffer and were run in the same buffer at 150 V at 10°C with pulse times of 20 s for 12 h and then 5 to 17 s for 17 h. The gels were stained in 1 μg of ethidium bromide per ml for 30 min and photographed on a UV transilluminator. DNA fragment sizes were determined with a computer with Taxotron software by interpolation from the sizes of bacteriophage lambda marker I (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), which was used as a molecular size standard.

Data acquisition and analysis.

For computer database editing, each strain was given a pattern designation according to the patterns generated by the three methods tested.

RESULTS

Bacterial species identification or confirmation.

After 24 h of aerobic incubation at 37°C, colonies of approximately 2 mm in diameter were smooth, shiny, and nontransparent with a grayish tinge. All strains presumed to belong to the species P. haemolytica were gram negative and nonmotile and produced oxidase, catalase, and acid by fermentation of glucose. Complete identification as P. haemolytica was assessed with the 20NE system database (API-Biomérieux).

Ribotyping.

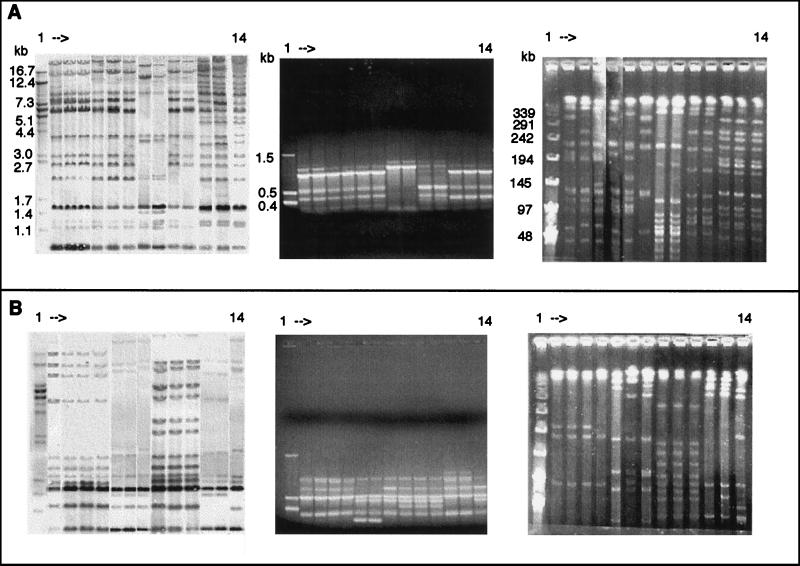

Each unique rRNA gene (rDNA) restriction pattern obtained after digestion with HindIII was designated a ribotype. A total of 15 patterns recorded as ribotypes HA to HO were found for the P. haemolytica biotype A strains, with ribotypes HA, HC, and HD being encountered the most often: 44 (49%), 15 (17%), and 7 (8%) strains, respectively. Ribotype HA yielded the 13 DNA fragments with computer-estimated sizes of 20,609, 16,177, 9,174, 7,622, 6,190, 3,853, 2,906, 2,550, 2,130, 1,483, 1,262, 1,184, and 918 bp. Furthermore, these three ribotypes were nearly identical, with differences based upon the lack of the 2,130-bp fragment for ribotype HC but the presence of that fragment for ribotype HA or the displacement of the 2,550-bp fragment in ribotype HA for the 2,690 bp fragment in ribotype HD (Fig. 1A). The association of serotypes and ribotypes showed that all the bovine strains which belonged to serotype A1 were regrouped in ribotype HA, an almost homogeneous cluster, in contrast to serotype A2 strains, which were more heterogeneous. Despite this heterogeneity, the same ribotype could be observed for strains belonging to different serotypes, whatever their zoological or geographical origins. For example, ribotype HA was recognized in isolates recovered from bovine, ovine, or caprine species in France, Hungary, Sweden, or the United Kingdom. Similar results were also observed in terms of the ribotype HC distribution, which was common to biotype A isolates of P. haemolytica from chamois, ovine, or caprine species of various origins (Table 1). The patterns for strains belonging to biotype T of P. haemolytica were distributed among 20 ribotypes, designated HA′ to HT′, because all these patterns were clearly distinct from those observed for biotype A. Among this group of organisms, isolates of each of the three serotypes included in the study had distinct ribotypes, with no cross ribotypes from one serotype to another. Ribotype HA′ was the major pattern observed among strains of serotype T3 (6 of 14 strains). Compared to the other patterns, a clear-cut distinction was observed between ribotype HA′ and the other ribotypes recorded for isolates of this serogroup of Pasteurella. Results obtained for serogroup T4 showed that the three ribotypes HH′, HI′, and HJ′ were the most representative (Table 1). Furthermore, these three ribotypes, which regrouped 17 of the 22 strains, were nearly identical and were distinguished only by the presence or the lack of one or two internal fragments (Fig. 1B). In contrast to biogroup A, cross ribotypes between strains from one animal host to another or from one geographical area to another were not found within the biogroup T strains of P. haemolytica studied.

FIG. 1.

Results obtained by ribotyping, RAPD analysis, and PFGE of representative P. haemolytica strains. The results obtained by each method are presented from left to right in the three panels of A and B, respectively. (A) Representative strains of P. haemolytica biotype A. Lanes 2 to 14, strains 1908, 1924, 2439, 2961, 41/94, 78s, 64, 75, 141, 172, 3/94, 9/94, and 10/95, respectively. (B) Representative strains of P. haemolytica biotype T. Lanes 2 to 14, strains 1205P, 1205T, 1231P, 1229T, CIP 104865, CIP 104866, CIP 104864, 3P, 3T, 4N, CIP 104867, CIP 104869, and CIP 104870, respectively. The following molecular size markers were used in lane 1 of each panel: for ribotyping, MluI-digested DNA of C. koseri CIP 105177; for RAPD analysis, fragments of E. coli Ca1 DNA; and for PFGE, bacteriophage lambda ladder I.

RAPD analysis.

RAPD analysis of the P. haemolytica strains included in the study generated a total of 44 (designated Rp1 to Rp44) and 15 (designated Rp1′ to Rp 15′) unique RAPD patterns for biogroup A and biogroup T, respectively. Again, as observed by ribotyping analysis, biotype A and biotype T strains clustered distinctively, and cross patterns were not found. Use of the combination of the ribotype and the RAPD analysis patterns further subclustered strains belonging to both biotypes into subgroups within a given ribotype, with each subgroup comprising 2 to 12 strains, along with strains presenting a unique double pattern. Thus, a total of 20 and 8 subgroups (except those containing a single strain) were recognized for P. haemolytica biotype A and biotype T, respectively, with 12 subgroups found in the single ribotype HA, in which RAPD analysis patterns Rp1 and Rp2 were the most frequently observed. In some instances, for the group of P. haemolytica biotype A organisms harboring the same ribotype and serotype, strains originating from different ruminant hosts recovered from separate geographical areas could even be subclustered because they had the same RAPD patterns. As listed in Table 1, French ovine (strains 126 and 68s) or bovine (strains 2965 and 3179) isolates were found to have the HA-Rp2 combination pattern; Hungarian caprine (strain 41/94), French bovine (strain 1619), or French ovine (strains 78s, 100s) isolates were in the HA-Rp3 subgroup; Hungarian caprine (strain 1/96) and Swedish ovine (strain CCUG 408) isolates were in the HA-Rp10 subgroup; and finally, Hungarian ovine (strain 1/94) and French ovine (strain 258s) isolates were in the HN-Rp42 subgroup. For each of these last subgroups, strains belonged to the same given A serotype. In most instances, ribotyping combined with RAPD analysis clearly separated each isolate in serotype A except in one case, in which an HB-Rp6 profile was found for both serotype A1 and A2 strains, strains 64 and 75 (serotype A1) and strain 73 (serotype A2). Although this scheme of subdifferentiation could also be observed for the biogroup T strains, a cross ribotype-RAPD analysis combination pattern was not found between ovine and chamois isolates or between strains belonging to two distinct serotypes.

PFGE.

Analysis of strains or groups of strains of P. haemolytica by PFGE gave a higher level of strain discrimination. Again, biotype A and biotype T strains of P. haemolytica clustered separately. The PFGE patterns were given the designations P1 to P69 and P1′ to P26′ for P. haemolytica biotype A and biotype T strains, respectively (Table 1). For the majority of groups determined to be concordant according to their RAPD analysis and ribotype profiles, further analysis by PFGE revealed residual heterogeneity. For eight and three groups (biotype A and T, respectively), however, the homogeneity of the group was essentially maintained even by PFGE (Table 1). For all other groups, concordant ribotype and RAPD analysis clusters were further subdivided into many other PFGE subgroups, with most subgroups comprising a single strain. Furthermore, strains or groups of strains appeared to be distinct with regard to their zoological or geographical origins (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

DNA-based typing schemes such as ribotyping, 16S-23S intergenic region amplification, RAPD analysis, and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis have been found to be preferable to the phenotyping strategies for the typing of P. haemolytica (2, 5, 6, 23). Most of the data from the previous studies have shown a close relationship between different P. haemolytica strains, particularly within a given serotype of biotype A. Furthermore, on the basis of ribotyping and RAPD analysis, the hypothesis of a clonal dissemination of a given strain between different bovine herds in France has been advanced, since all bovine P. haemolytica strains belonging to the A1 serotype appeared to be genetically identical or almost identical by both methods (5). The present investigation was conducted with strains of various origins, including most of the bovine strains from the previous study (5), in order to further scrutinize their genetic relationships. Because PFGE has proven to be the most efficient subtyping method for many other bacterial genera and species such as Aeromonas (25), Legionella (3), Pseudomonas (24), and Yersinia (13), it has been chosen as an additional epidemiological tool for evaluation of the efficiency of both ribotyping and RAPD analysis, a strategy which may additionally confirm or deny the hypothesis of clonal dissemination. On the basis of the data obtained from the present study, the conclusion that strains of biotype A of P. haemolytica have a close genetic relationship can also be made from the ribotyping analysis alone, since a given ribotype pattern was observed for strains of several distinct A serotypes, even strains from different hosts in various geographical areas: see, for example the pattern for serotype A1 Hungarian caprine strain 41/94 versus those for serotype A1 French ovine strain 78s and A2 Swedish ovine strain CCUG 408 versus that for serotype A2 Hungarian caprine strain 1/96, which shared a common ribotype (ribotype HA). In some instances, some strains belonging to serotypes A1 and A2 also appeared to be identical by RAPD analysis (see, for example, the results for strains 64, 75, and 73). In contrast, the results from PFGE analysis indicated that a given common clone of P. haemolytica organisms was never observed by this method for isolates from two different hosts or for isolates from different locations. Moreover, the results obtained by this method lead to the conclusion that most of the strains recovered from cattle appeared to be unique with regard to their PFGE types (pulsotypes).

From a more fundamental point of view, the variations in the PFGE patterns observed after passage through different hosts or after in vitro passages may indicate some genomic plasticity in a given species. These modifications may have occurred either in vitro, after isolation of the bacteria, or in vivo, under the selective pressure exerted by the host. This macrorestriction polymorphism plasticity has been described in some other bacterial species such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (24) and Yersinia pestis (12). In the case of P. aeruginosa, the persistence of a given strain in its host for several months resulted in up to 20% genomic divergence (24). In Y. pestis, PFGE restriction analysis has recently demonstrated a high degree of instability of a given strain after in vitro cultivation, with differences between profiles being based not only on one or two bands but also involving numerous restriction fragments of various sizes (12). To verify whether such an event could also occur in P. haemolytica and could account for the slight differences observed between the pulsotypes of strains with the same combination pattern by ribotyping-RAPD analysis, bovine strains 2439 and 2961 (HA-Rp1 group) and Hungarian caprine strain 41/94 and French ovine strain 78s (HA-Rp3 group) were subcultured on blood agar plates, and five randomly picked colonies of each strain were subjected to PFGE as indicated above. The selected colonies yielded a constant and stable PFGE pattern for each of the four strains analyzed (data not shown), indicating an in vitro stability of the pulsotypes of P. haemolytica. Similar results were obtained by other workers with other bacterial species such as Legionella pneumophila (3) and Yersinia enterocolitica (13). Despite multiple subcultures or prolonged passage on artificial culture medium, the pulsotypes of these species also remained stable in vitro, while a high degree of genomic diversity was observed among strains of different origins. Of course, this analysis does not definitely rule out the possibility of some genomic rearrangements at a low frequency in P. haemolytica, particularly in the animal host, but it strengthens our results and demonstrates that PFGE is the most meaningful tool for the subtyping of this species and thereby provides evidence and confirms unequivocally the differences observed between ribotyping (and/or RAPD analysis) and PFGE analysis. Thus, analysis of all the data from this study does not support the conclusion that there is a high degree of relatedness among biotype A strains because PFGE can further distinguish the strains of P. haemolytica with a common ribotype-RAPD analysis pattern, rendering PFGE useful for epidemiological tracing. In addition, these results raise the question of what should be considered a P. haemolytica clone and a bacterial clone in general. The present study suggests that clades or clusters are suitable designations for ribogroups or RAPD analysis groups, and the term clone should be kept for the pulsogroups. Be that as it may, one can conclude that ribotyping even in association with RAPD analysis is not efficient in differentiating strains of P. haemolytica, since PFGE has proven to be the ultimate tool for distinguishing isolates of this species. Elsewhere, the present data are in total agreement with previous findings (7, 22) and clearly separate the two biotypes of P. haemolytica into two separate species, for which the names P. haemolytica and P. trehalosi have been proposed for biotypes A and T, respectively (22).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to E. Falsen and F. Grimont for kindly providing some bacterial strains. We thank Timothy Greenland (Laboratoire d’Immunologie et de Biologie Pulmonaire, Hôpital Louis Pradel, Lyon, France) for discussion and help in preparing the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Office National de la Chasse (ONC) and the “SP2” Soutien de Programme of the Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Pêche of France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adlam C. The structure, function and properties of cellular and extracellular components of Pasteurella haemolytica. In: Adlam C, Rutter J M, editors. Pasteurella and pasteurellosis. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angen O, Caugant D A, Olsen J E, Bisgaard M. Genotypic relationships among strains classified under the (Pasteurella) haemolytica-complex as indicated by ribotyping and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Zentbl Bakteriol-Int J Med Microbiol. 1997;286:333–354. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(97)80091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brender L, Ott M, Hacker J. Genome analysis of Legionella pneumophila ssp. by orthogonal field alternation gel electrophoresis (OFAGE) FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;72:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90313-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callan R J, Bunch T D, Workman G W, Mock R E. Development of pneumonia in desert bighorn sheep after exposure to a flock of exotic wild and domestic sheep. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991;198:1052–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaslus-Dancla E, Lessage-Descauses M C, Leroy-Sétrin S, Martel J L, Coudert P, Laffont J P. Validation of random amplified polymorphic DNA assays by ribotyping as tools for epidemiological surveys of Pasteurella from animals. Vet Microbiol. 1996;52:91–102. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies R L, Arkinsaw S, Selander R K. Evolutionary genetics of Pasteurella haemolytica isolates recovered from cattle and sheep. Infect Imm. 1997;65:3585–3593. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3585-3593.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies R L, Paster B J, Dewhirst F E. Phylogenetic relationships and diversity within the Pasteurella haemolytica complex based on 16S rRNA sequence comparison and outer membrane protein and lipopolysaccharide analysis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:736–744. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-3-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fodor L, Penzes Z, Varga J. Coagglutination test for serotyping Pasteurella haemolytica. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:393–397. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.393-397.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foreyt W J, Silflow R M, Lagerquist J E. Susceptibility of Dall sheep (Ovis dalli dalli) to pneumonia caused by Pasteurella haemolytica. J Wildl Dis. 1996;32:586–593. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-32.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franck G H. Pasteurellosis in cattle. In: Adlam C, Rutter J M, editors. Pasteurella and pasteurellosis. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilmour N J L, Gilmour J S. Pasteurellosis of sheep. In: Adlam C, Rutter J M, editors. Pasteurella and pasteurellosis. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1898. pp. 223–262. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guiyoule A, Grimont F, Iteman I, Grimont P A D, Amouroux A, Carniel E. Plague pandemies investigated by ribotyping of Yersinia pestis strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:634–641. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.634-641.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hristo N, Iteman I, Carniel E. Efficient subtyping of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2913–2920. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2913-2920.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodjo A, Richard Y, Tonjum T. Moraxella boevrei sp. nov., a new Moraxella species found in goats. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:115–121. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martel J L, Richard S. Presented at the “La Vaccination en Buiatrie,” International Congress of the French Society of Buiatry. Paris, France: French Society of Buiatry; 1995. Frequence of Pasteurella haemolytica serotypes isolated from bovine in France. Communication. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mutters R, Mannheim W, Bisgaard M. Taxonomy of the group. In: Adlam C, Rutter J M, editors. Pasteurella and pasteurellosis. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odendaal M W, Henton M M. The distribution of Pasteurella haemolytica serotypes among cattle, sheep, and goats in South Africa and their association with disease. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1995;62:223–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richard Y, Borges E, Gauthier D, Favier C, Sanchis R, Oudar J. Isolement de 33 souches de Pasteurella béta hémolytiques chez le chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) Gibier Faune Sauvage. 1992;9:71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richard Y, Menouri N, Guigen F, Favier C, Borges E, Fontaine M, Oudar J, Brunet J, Pailhac C. Pneumopathies de l’agneau de bergerie. Etude bactériologique sur des poumons prélevés à l’abattoir. Rev Med Vet. 1986;137:671–680. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchis R, Abadie G, Polveroni G. Typage de Pasteurella haemolytica. Etude de 115 souches isolées chez les petits ruminants. Rec Med Vet. 1988;165:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchis R, Guerrault P, Abadie G, Pellet P M. Fréquence d’isolement des sérotypes de Pasteurella haemolytica chez les ovins et les caprins. Etude de 230 souches. Rev Med Vet. 1991;142:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sneath P H A, Stevens M. Actinobacillus rossii sp. nov., Actinobacillus seminis sp. nov., nom. rev., Pasteurella bettii sp. nov., Pasteurella lymphangitidis sp. nov., Pasteurella mairi sp. nov., and Pasteurella trehalosi sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:148–153. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-2-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snipes K P, Kasten R W, Wild M A, Miller M W, Jessup D A, Silflow R L, Foreyt W J, Carpenter T E. Using ribosomal RNA gene restriction patterns in distinguishing isolates of Pasteurella haemolytica from bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) J Wildl Dis. 1992;28:347–354. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-28.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Struelens M J, Schwam V, Deplano A, Baran D. Genome macrorestriction analysis of diversity and variability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains infecting cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2320–2326. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2320-2326.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talon D, Dupont M J, Lesne J, Thouverez M, Michelbriand Y. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as an epidemiological tool for clonal identification of Aeromonas hydrophila. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;80:277–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Younan M, Fodor L. Characterization of a new Pasteurella haemolytica (A17) Res Vet Sci. 1995;58:98. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(95)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]