Abstract

The effect of CD34+ cell dose in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) on overall survival (OS) and incidence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) has not been established and few studies have been performed. Our single center analysis included 189 patients with hematological malignancies who received peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) grafts from sibling donors. Myeloablative conditioning was used in 88 cases and 101 received reduced intensity conditioning. The median CD34+ cell dose was 5.6 × 106/kg (0.6–17.0). In the multivariate analysis, a CD34 cell dose of 6–7 × 106/kg was associated with better OS and lower transplant-related mortality (TRM), while a dose of <5 × 106/kg led to increased relapse and reduced chronic GVHD (cGVHD). A high CD34 cell-dose (>6.5 × 106/kg) correlated with less acute GVHD (aGVHD) II–IV. We conclude that the CD34 cell dose has an impact on the outcome of HSCT from sibling donor PBSCs.

Keywords: Cell dose, CD34, HSCT, GVHD, PBSC

1. INTRODUCTION

For hematologic malignancies, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a potentially curative treatment option as consolidation after chemotherapy or as salvage in relapsed disease. In 2017, almost 15,000 allogeneic transplants were performed in Europe for myeloid and lymphoid malignancies [1]. The outcome of HSCT is influenced by many factors, including the underlying disease, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matching, patient and donor age, cytomegalovirus (CMV) serostatus, co-morbidities, conditioning regimens, graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) prophylaxis and graft source and composition [2–7]. Grafts derived from peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) have higher numbers of T-lymphocytes and CD34+ cells compared to bone marrow (BM) grafts [8]. The number of T-cells has been shown to be associated with the incidence and severity of GvHD [9–11]. Several studies have identified the CD34+ cell dose contained in the graft to be associated with outcome [12–14]. To ensure reliable engraftment, the minimal accepted dose for transplant in BM grafts is 2 × 108/kg, and 6 × 108/kg in PBSC grafts [12,15]. Higher CD34+ cell doses have been associated with a positive impact, e.g., a more rapid engraftment and fewer infectious complications, but have also been associated with higher risks of chronic GvHD after reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) transplants [16]. Mohty et al. reported increased mortality and worse outcome with higher doses of CD34+ cells in PBSC grafts in HLA-identical sibling donors [17]. Also, Urbano-Ispizua et al. showed that higher CD34+ cell doses were associated with poorer outcomes after transplantation with grafts positively selected for CD34+ cells [18].

Despite the fact that transplant methods have improved in the last two decades and transplant-related mortality (TRM) is generally lower, the impact of CD34+ cell dose may still be of importance and should maybe be taken into account in the transplant procedure. In this retrospective study, we investigated the impact of CD34+ cell dose in HSCT from sibling donors' T-cell replete PBSC grafts on the incidence and severity of acute and chronic GvHD, relapse and overall survival (OS).

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients

The effect of the graft CD34+ cell dose was studied in 189 consecutive HSCT patients, transplanted between January 2005 and May 2018 at Oslo University Hospital, Norway. Only patients with a malignant disease receiving PBSC from an HLA-identical sibling were included. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee. The procedures were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

2.2. HLA Typing

All patients and donors were typed using high resolution PCR-SSP for both HLA class I and II alleles [18,19].

2.3. Conditioning Regimen and GvHD Prophylaxis

RIC was given to 101 patients and consisted of a backbone of fludarabine 30 mg/m2/d for 4–5 days in combination with (a) cyclophosphamide (Cy) 600 mg/m2 for 4 days (n = 32), (b) treosulfan 14 g/m2 for 3 days (n = 18) or (c) oral busulfan (Bu) at 4 mg/kg/d for 2 days (n = 39), (d) 2 Gy total body irradiation (TBI)(n = 11) [20–22]. Myeloablative conditioning (MAC)(n = 88) consisted of Cy 60 mg/kg/d for 2 days in combination with (a) 4 × 3 Gy fractionated TBI (n = 3) or (b) 4 mg/kg/d busulfan for 4 days (n = 85) [23]. Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) was not given to any patient.

Prophylaxis against GVHD consisted of cyclosporine A (CsA) in combination with methotrexate (MTX, n = 145), mycofenolate mofetil (MMF, n = 13) or sirolimus (n = 31) [21,23,24]. During the first month, blood CsA trough levels were kept at 150–250 ng/mL, depending on the transplant protocol. In the absence of GvHD, CsA was tapered with the aim of discontinuation after three to four months.

2.4. Stem Cell Source

All patients received granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) mobilized PBSC grafts. Stem cells were mobilized with subcutaneous G-CSF daily for 4–6 days [25].

2.5. Statistics

OS and graft-versus-host and relapse-free survival (GRFS) were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Survival time was calculated from the day of transplantation until an event or last follow-up. For GRFS the events were death, relapse, acute GvHD III–IV or extensive chronic GVHD, whatever came first. The incidence of TRM, relapse and GvHD were obtained using an estimator of cumulative incidence curves. Patients were censored at the time of death or last follow-up.

Uni- and multivariate predictive analyses for relapse, TRM and GvHD were performed with the proportional sub-distribution hazard regression model of Fine and Gray [26], while analyses of OS and GRFS were done using the Cox proportional hazards model. Time-to-engraftment was analyzed as a dichotomous variable (higher than median time-to-engraftment, 17 days) using logistic regression. The multivariate analyses were corrected for differences between the groups (diagnosis, disease stage, age, female donor to male recipient (FtoM), conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis). The main aim was to evaluate the effect of the CD34+ cell dose on the outcome after HSCT with PBSC.

Analyses were performed using the EZR freely available software [27] and Statistica 13 (TIBCO, Palo Alto, CA, USA) software.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Patient and donor characteristics are displayed in Tables 1a and 1b. The median CD34+ cell dose was 5.6 × 106/kg (0.6–17). The distribution of the cell dose is shown in Figure 1. The patients were divided into four groups approximately according to CD34+ cell dose quartiles; (1) <5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg (n = 71), (2) 5–6 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg (n = 43), (3) 6–7 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg (n = 52) and (4) >7 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg (n = 23). RIC was given to 101 patients and MAC to 88.

Table 1a.

Patient characteristics. HSCT patients receiving PBSCs from sibling donors.

| Sib PBSC | |

|---|---|

| N = | 189 |

| Rec age | 56 (17–71) |

| Gender (male/female) | 122/67 |

| Diagnosis: | |

| Acute leukemia | 111 |

| Chronic leukemia | 9 |

| Lymphoma | 31 |

| MDS/MPN | 26 |

| Myeloma | 12 |

| Stage (early/late) | 88/101 |

| CD34+ cell dose (× 106/kg) | 5.6 (0.6–17.0) |

| Donor age | 53 (15–74) |

| F to M (yes/no) | 60/129 |

| RIC/MAC | 101/88 |

| TBI/Chemo | 14/175 |

| ATG (yes/no) | 0/186 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | |

| CsA+MTX | 145 |

| CsA+MMF | 13 |

| CsA+Sirolimus | 31 |

| Rec CMV (±) | 44/145 |

| Don CMV (±) | 74/112 |

| R/D CMV (MM/match) | 60/126 |

HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, PBSCs: peripheral blood stem cells, MDS/MPN: myelodysplastic syndrome/myeloproliferative neoplasm, Late stage: beyond CR1/CP1, FtoM: female donor to male recipient, MAC: myeloablative conditioning, RIC: reduced intensity conditioning, TBI: total-body irradiation, ATG: anti-thymocyte globulin, GVHD: graft-versus-host disease, CsA: cyclosporine A, MTX: methotrexate, MMF: mycofenolate mofetil, Rec CMV: recipient CMV sero-status, Don CMV: donor CMV sero-status, R/D CMV: recipient/donor CMV sero-status, MM: mismatch.

Table 1b.

Patient characteristics. HSCT patients receiving PBSCs from sibling donors divided by CD34+ cell dose.

| <5 × 106/kg | 5–6 × 106/kg | 6–7 × 106/kg | >7 × 106/kg | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = | 71 | 43 | 52 | 23 | |

| Rec age | 58 (21–69) | 57 (17–70) | 53 (20–71) | 51 (21–65) | 0.08 |

| Gender (male/female) | 51/20 | 32/11 | 29/23 | 10/13 | 0.02 |

| Diagnosis: | 0.004 | ||||

| Acute leukemia | 46 (65) | 15 (35) | 36 (69) | 14 (61) | |

| Chronic leukemia | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 4 (8) | 3 (13) | |

| Lymphoma | 8 (11) | 19 (44) | 3 (6) | 1 (4) | |

| MDS/MPN | 15 (21) | 3 (7) | 6 (12) | 2 (9) | |

| Myeloma | 1 (1) | 5 (12) | 3 (6) | 3 (13) | |

| Stage (early/late) | 36/35 | 13/30 | 26/26 | 13/10 | 0.10 |

| Donor age | 55 (23–74) | 51 (15–67) | 50 (19–70) | 53 (18–73) | 0.33 |

| F to M | 32 (45) | 17 (40) | 8 (15) | 3 (13) | <0.01 |

| RIC/MAC | 37/34 | 30/13 | 26/26 | 8/15 | 0.04 |

| TBI/Chemo | 3/68 | 6/37 | 4/48 | 1/22 | 0.26 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | <0.001 | ||||

| CsA+MTX | 61 (86) | 21 (49) | 43 (83) | 20 (87) | |

| CsA+MMF | 2 (3) | 6 (14) | 4 (8) | 1 (4) | |

| CsA+Sirolimus | 8 (11) | 16 (37) | 5 (10) | 2 (9) | |

| Rec CMV (±) | 19/52 | 9/34 | 10/42 | 6/17 | 0.76 |

| Don CMV (±) | 31/40 | 12/30 | 23/28 | 8/14 | 0.34 |

| R/D CMV (mismatch) | 26 (37) | 10 (23) | 19 (37) | 5 (22) | 0.32 |

| R/D CMV (neg/neg) | 12 (17) | 5 (12) | 7 (13) | 4 (17) | 0.85 |

HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, PBSCs: peripheral blood stem cells, MDS/MPN: myelodysplastic syndrome/myeloproliferative neoplasm, Late stage: beyond CR1/CP1, FtoM: female donor to male recipient, MAC: myeloablative conditioning, RIC: reduced intensity conditioning, TBI: total-body irradiation, ATG: anti-thymocyte globulin, GVHD: graft-versus-host disease, CsA: cyclosporine A, MTX: methotrexate, MMF: mycofenolate mofetil, Rec CMV: recipient CMV sero-status, Don CMV: donor CMV sero-status, R/D CMV: recipient/donor CMV sero-status.

Figure 1.

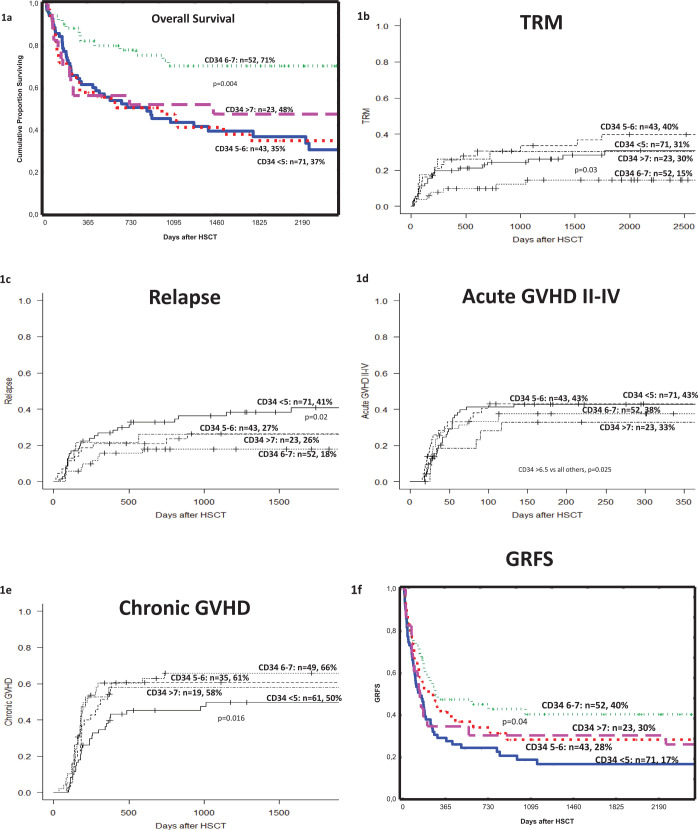

The effect of the CD34+ cell dose (× 106/kg) on (a) overall survival (OS), (b) transplant-related mortality (TRM), (c) relapse (d) acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) II-IV, (e) chronic GVHD and (f) GVHD and relapse-free survival (GRFS) in patients with malignant diseases who received a peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) graft from a sibling donor. The p-values indicate differences between the 6–7 × 106/kg (OS, TRM, GRFS) or the <5 × 106/kg (Relapse, cGVHD) groups and all the others as found on multivariate analyzes.

3.2. Clinical Outcome and CD34+ Cell Dose

3.2.1. Engraftment

Six patients (3.2%) had primary graft failure (GF). We found no correlation between the CD34+ cell-dose and GF. The median time to neutrophil engraftment (neutrophils count >0.5 × 109/L) was 17 days. In multivariate analysis <5 × 106/CD34+ cells/kg correlated to slower engraftment, measured as later than median days-to-engraftment (OR 2.46, 95% CI 1.15–5.27, p = 0.02).

3.2.2. Survival

The 5-year OS for all patients was 47%. Among the four groups, the best 5-year OS (71%) was seen in group 3, i.e., those patients receiving 6–7 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg (Figure 1a). Similar results were seen in patients with (a) acute leukemia, (b) acute leukemia in first complete remission (CR1) and (c) acute leukemia beyond CR1.

In the multivariate analysis a CD34+ cell dose of 6–7 × 106 cells/kg was associated with superior OS, hazard ratio (HR): 0.43, 95% (confidence interval) CI: 0.25–0.77, p = 0.004 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results from the multivariate analysis. HR, 95% CI and p-value are given for each factor.

| Factor | Mortality | TRM | Relapse | Acute GVHD II-IV | Chronic GVHD | GRFS | Time to ANC >0.5 × 109/L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age p value |

Cont. | 1.02, 1.01–1.04, p=0.02 | 1.04, 1.01–1.07, p=0.015 | 0.98, 0.96–1.01, p=0.16 | 0.99, 0.97–1.02, p=0.77 | 1.00, 0.98–1.02, p=0.92 | 0.99, 0.98–1.01, p=0.74 | – |

| F to M p value |

Yes | 1.66, 1.09–2.52, p=0.02 | 1.59, 0.90–2.77, 0.11 | 1.19, 0.69–2.05, 0.53 | 1.00, 0.61–1.65, 0.99 | 2.05, 1.34–3.14, <0.001 | 1.40, 0.98–2.02, 0.07 | 1.36, 0.61–3.03, 0.44 |

| Acute leukemia | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| MDS/MPN | 1.69, 0.89–3.21, 0.11 | 0.90, 0.66–1.22, 0.49 | 0.84, 0.55–1.26, 0.40 | 0.90, 0.62–1.28, 0.55 | 0.96, 0.72–1.28, 0.79 | 1.83, 1.07–3.13, 0.03 | 1.20, 0.74–1.97, 0.46 | |

| Diagnosis p value | Lymphoma | 1.12, 0.45–2.80, 0.81 | 0.71, 0.30–1.64, 0.42 | |||||

| Other | 1.32, 0.57–3.04, 0.52 | 1.02, 0.45–2.27, 0.97 | ||||||

| Disease stage p value |

Early (CR1/CP1) | 1.20, 0.71–2.03, 0.49 | 1.03, 0.53–2.01, 0.93 | 0.91, 0.44–1.88, 0.80 | 0.81, 0.46–1.44, 0.48 | 0.94, 0.57–1.55, 0.82 | 1.14, 0.74–1.75, 0.56 | 1.07, 0.47–2.64, 0.87 |

| GVHD prophylaxis p value |

CsA+MTX | 0.83, 0.39–1.78, 0.63 | 0.71, 0.33–1.53, 0.39 | 1.12, 0.46–2.70, 0.81 | 1.22, 0.52–2.83, 0.65 | 0.99, 0.54–1.85, 0.99 | 0.79, 0.38–1.61, 0.51 | 13.9, 3.81–50.7, <0.001 |

| Conditioning p value |

MAC | 1.58, 0.92–2.71, 0.10 | 2.08, 1.01–4.26, <0.05 | 0.92, 0.43–1.96, 0.82 | 0.80, 0.44–1.46, 0.47 | 1.23, 0.72–2.11, 0.45 | 1.09, 0.69–1.72, 0.72 | 2.13, 0.89–5.09, 0.09 |

| CD 34 dose p value |

6–7 × 106/kg | 0.43, 0.25–0.77, 0.004 | 0.41, 0.18–0.92, 0.03 | – | – | 0.65, 0.42–0.99, 0.04 | – | |

| <5 × 106/kg | – | – | 1.96, 1.12–3.42, 0.02 | – | 0.57, 0.36–0.90, 0.016 | – | 2.46, 1.15–5.27, 0.02 | |

| >6.5 × 106/kg | – | – | – | 0.50, 0.27–0.92, 0.025 | – | |||

| Donor age | Cont. | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.04, 1.01–1.07, 0.01 |

HR: hazards ratio, CI: confidence interval, F to M: female donor to male recipient, GVHD: graft-versus-host disease, MDS/MPN: myelodysplastic syndrome/myeloproliferative neoplasm, CR1/CP1: complete remission 1/chronic phase 1, CsA + MTX: cyclosporine A + methotrexate, MAC: myeloablative conditioning, OS: overall survival, TRM: transplant-related mortality, GRFS: graft-versus-host disease and relapse-free survival, RFS: relapse-free survival, ANC: absolute neutrophil count.

The TRM at 1 and 5 years was 19% and 28%, respectively. The lowest TRM (15%) was found among patients given a CD34+ cell dose of 6–7 × 106 cells/kg (Figure 1b). In the multivariate analysis we found that 6–7 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg (HR: 0.41, 95% CI: 0.18–0.92, p = 0.03) was associated with lower TRM. The causes of death are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Causes of death (CoD) in patients with malignant diseases who received a peripheral blood stem-cell graft from a sibling donor, depending on CD34+ cell-dose.

| CoD | <5 × 106/kg | 5–6 × 106/kg | 6–7 × 106/kg | >7 × 106/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse | 22 (31%)* | 10 (23%) | 7 (13%) | 6 (26%) |

| Infection | 5 (7%) | 3 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) |

| GVHD | 11 (15%) | 5 (12%) | 3 (6%) | 4 (17%) |

| Other | 6 (8%) | 8 (19%) | 4 (8%) | 2 (9%) |

CoD: causes of death, GVHD: graft-versus-host disease.

p = 0.03 vs 6–7 × 106/kg.

3.2.3. Relapse

The cumulative incidence of relapse (RI) for all patients was 29%. Increased RI (41%) was found in patients in group 1, who received the lowest CD34+ cell dose (<5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg) (Figure 1c). In the multivariate analysis the low CD34+ cell dose (<5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg) was associated with an increased risk of RI (HR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.12–3.42, p = 0.02).

3.2.4. Graft-versus-host disease

In total, 86 (46%) and 92 (56%) patients developed acute and chronic GvHD, respectively. The cumulative incidence of acute GvHD grades II–IV in the whole cohort was 40%. The lowest incidence of acute GvHD (aGVHD) II–IV (33%) was found among patients receiving a high cell-dose (Figure 1d). In the multivariate analysis, a CD34+ cell dose of >6.5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg was associated with a lower incidence of aGvHD II–IV (HR: 0. 50, 95% CI: 0.27–0.92, p = 0.025).

The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD among all patients was 58%. The lowest incidence of chronic GVHD (cGVHD) was seen among patients receiving a low cell dose (Figure 1e). In the multivariate analysis, a dose of <5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg was associated with a lower incidence of cGVHD (HR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.36–0.90, p = 0.016).

Extensive cGVHD was seen in 30 patients (30%), without any correlation with the CD34+ cell dose.

3.2.5. Graft-versus-host and relapse-free survival

The GFRS in the whole cohort was 28% at 5 years. A higher 5-year GRFS (40%) was seen in group 3, i.e., patients receiving 6–7 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg, whereas patients receiving <5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg had a lower GRFS (Figure 1f). In the multivariate analysis, receiving 6–7 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg correlated to higher GRFS (HR: 0.65, 95% CI: 0.42–0.99, p = 0.04).

4. DISCUSSION

The correlation between graft composition and clinical outcome in HSCT has been best described for the CD3+ cell dose. In the current study, we found significant correlations between OS, RI, occurrence of acute and chronic GvHD and the CD34+ cell dose delivered in the graft. Mohty et al. [17] did not find such a correlation with the risk of aGvHD, but a CD34+ cell dose in excess of 8 × 106/kg was associated with an increased risk of severe chronic GvHD in their cohort. This is in line with the findings in our current study where we detected more overall cGVHD in patients receiving >5 × 106/kg. However, we found no effect of the CD34 cell-dose on extensive cGVHD. An early study by Przepiorka et al. [28] reported a correlation between the CD34+ cell dose and the risk of developing acute GvHD. However, the transplant procedures were not comparable. Surprisingly we found that patients receiving the highest CD34+ cell dose had less aGvHD II-IV. One reason for this finding may be that such grafts may also contain a larger number of regulatory T-cells able to modulate the T-cell response [13].

Higher graft CD34+ cell numbers have been shown to be associated with more rapid engraftment of neutrophils and platelets, as well as shortened hospitalization, and this is commonly attributed to the higher cell dose [29–31]. In our study, we found that patients receiving <5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg had significantly slower neutrophil engraftment. However, above this cut-off level we found no additional effect of the CD34+ cell dose. However, other studies have shown that increasing the CD34+ cell dose above a certain threshold may not necessarily results in better outcome [13,17]. The data (both ours and others') show that increasing the CD34+ stem cell dose above a certain threshold may lead to higher mortality after HSCT with HLA-identical siblings [13,17]. Thus, within the current HLA identical sibling transplant protocols, there seems to exist a threshold value above which any further increase in the CD34+ cell number will not provide any additional benefit, but rather contribute adversely to the transplant outcome.

Not surprisingly, we found that the patients receiving the lowest CD34+ cell dose (group 1, <5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg) had an increased risk of relapse. A graft containing low number of CD34+ cells probably also contains low number of T-cells, which may lead to a weaker graft-versus-leukemia effect and increasing the risk of relapse. More unexpected was the finding that patients in the group receiving the highest CD34+ cell dose (group 4, >7 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg) had equal survival to group 1, albeit with other reasons for treatment failure.

We recognize that this study has several limitations. First, it is retrospective and registry-based from a single center. Second, the number of patients is limited and heterogeneous with variations in conditioning intensity. Also, none of the patients in our current study received ATG for prophylaxis of GvHD. This will likely affect the incidence of chronic GvHD, and our results are likely only representative for patients not receiving ATG.

In conclusion, we find that survival deteriorates above a threshold value of around 7 × 106/kg and that a target dose of 6–7 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg may represent the optimum regarding kinetics of hematologic recovery, risk of GvHD and TRM. This should be confirmed in larger registry-based studies and prospective observational studies, both with and without ATG as GvHD prophylaxis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (2017-00355) (MR) and funding from the Norwegian cancer association (YF).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the International Academy for Clinical Hematology

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, YF. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

MR prepared study conception and design, drafting of manuscript, performed statistical analyses, analysis and interpretation of data. BG, MA, KUL, AM, IA, DH, ID, GET, and TGD are performed in critical revision of the manuscript. JM and TE are prepared study conception and design, and critical revision. YF prepared study conception and design, drafting of manuscript, acquisition of data.

REFERENCES

- [1].Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Bader P, Bonini C, Cesaro S, Dreger P, et al. Impact of drug development on the use of stem cell transplantation: a report by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52:191–6. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ljungman P, Brand R, Hoek J, de la Camara R, Cordonnier C, Einsele H, et al. Donor cytomegalovirus status influences the outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplant: a study by the European group for blood and marrow transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:473–81. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Finke J, Schmoor C, Bethge WA, Ottinger HD, Stelljes M, Zander AR, et al. Prognostic factors affecting outcome after allogeneic transplantation for hematological malignancies from unrelated donors: results from a randomized trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1716–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Petersdorf EW, Gooley TA, Anasetti C, Martin PJ, Smith AG, Mickelson EM, et al. Optimizing outcome after unrelated marrow transplantation by comprehensive matching of HLA class I and II alleles in the donor and recipient. Blood. 1998;92:3515–20. doi: 10.1182/blood.v92.10.3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storer B, Sandmaier BM, Diaconescu R, Flowers C, et al. Comparing morbidity and mortality of HLA-matched unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative and myeloablative conditioning: influence of pretransplantation comorbidities. Blood. 2004;104:961–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pulsipher MA, Chitphakdithai P, Logan BR, Leitman SF, Anderlini P, Klein JP, et al. Donor, recipient, and transplant characteristics as risk factors after unrelated donor PBSC transplantation: beneficial effects of higher CD34+ cell dose. Blood. 2009;114:2606–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kollman C, Howe CW, Anasetti C, Antin JH, Davies SM, Filipovich AH, et al. Donor characteristics as risk factors in recipients after transplantation of bone marrow from unrelated donors: the effect of donor age. Blood. 2001;98:2043–51. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Champlin RE, Schmitz N, Horowitz MM, Chapuis B, Chopra R, Cornelissen JJ, et al. Blood stem cells compared with bone marrow as a source of hematopoietic cells for allogeneic transplantation. IBMTR Histocompatibility and Stem Cell Sources Working Committee and the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Blood. 2000;95:3702–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gaziev J, Isgro A, Marziali M, Daniele N, Gallucci C, Sodani P, et al. Higher CD3+ and CD34+ cell doses in the graft increase the incidence of acute GVHD in children receiving BMT for thalassemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:107–14. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rocha V, Carmagnat MV, Chevret S, Flinois O, Bittencourt H, Esperou H, et al. Influence of bone marrow graft lymphocyte subsets on outcome after HLA-identical sibling transplants. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:1347–52. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00737-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mohty M, Bagattini S, Chabannon C, Faucher C, Bardou VJ, Bilger K, et al. CD8+ T cell dose affects development of acute graft-versus-host disease following reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:1097–102. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ringden O, Barrett AJ, Zhang MJ, Loberiza FR, Bolwell BJ, Cairo MS, et al. Decreased treatment failure in recipients of HLA-identical bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplants with high CD34 cell doses. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:874–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Remberger M, Torlen J, Ringden O, Engstrom M, Watz E, Uhlin M, et al. Effect of total nucleated and CD34+ cell dose on outcome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:889–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Torlen J, Ringden O, Le Rademacher J, Batiwalla M, Chen J, Erkers T, et al. Low CD34 dose is associated with poor survival after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:1418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Singhal S, Powles R, Treleaven J, Kulkarni S, Sirohi B, Horton C, et al. A low CD34+ cell dose results in higher mortality and poorer survival after blood or marrow stem cell transplantation from HLA-identical siblings: should 2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg be considered the minimum threshold? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:489–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Perez-Simon JA, Diez-Campelo M, Martino R, Sureda A, Caballero D, Canizo C, et al. Impact of CD34+ cell dose on the outcome of patients undergoing reduced-intensity-conditioning allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2003;102:1108–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mohty M, Bilger K, Jourdan E, Kuentz M, Michallet M, Bourhis JH, et al. Higher doses of CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells are associated with increased mortality from chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic HLA-identical sibling transplantation. Leukemia. 2003;17:869–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Urbano-Ispizua A, Carreras E, Marin P, Rovira M, Martinez C, Fernandez-Aviles F, et al. Allogeneic transplantation of CD34+ selected cells from peripheral blood from human leukocyte antigen-identical siblings: detrimental effect of a high number of donor CD34+ cells? Blood. 2001;98:2352–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2352.h8002352_2352_2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Olerup O, Zetterquist H. HLA-DR typing by PCR amplification with Sequence-Specific Primers (PCR-SSP) in 2 hours: an alternative to serological DR typing in clinical practice including donor–recipient matching in cadaveric transplantation. Tissue Antigens. 1992;39:225–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1992.tb01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Uzunel M, Remberger M, Sairafi D, Hassan Z, Mattsson J, Omazic B, et al. Unrelated versus related allogeneic stem cell transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning. Transplantation. 2006;82:913–19. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000233865.20232.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Niederwieser D, Maris M, Shizuru JA, Petersdorf E, Hegenbart U, Sandmaier BM, et al. Low-dose Total Body Irradiation (TBI) and fludarabine followed by Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT) from HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donors and postgrafting immunosuppression with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) can induce durable complete chimerism and sustained remissions in patients with hematological diseases. Blood. 2003;101:1620–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, Kapelushnik Y, Aker M, Cividalli G, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood. 1998;91:756–63. doi: 10.1182/blood.v91.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ringdén O, Horowitz M, Sondel P. Methotrexate, cyclosporine or both to prevent graft-versus-host disease after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplants for early leukemia. Blood. 1993;18:1094–101. doi: 10.1182/blood.V81.4.1094.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Torlen J, Ringden O, Garming-Legert K, Ljungman P, Winiarski J, Remes K, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing cyclosporine/methotrexate and tacrolimus/sirolimus as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2016;101:1417–25. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.149294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ringden O, Remberger M, Runde V, Bornhauser M, Blau IW, Basara N, et al. Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation from unrelated donors: a comparison with marrow transplantation. Blood. 1999;94:455–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fine J, Gray R. Proportional hazard model for the sub-distribution of competing risks. J Amer Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Przepiorka D, Smith TL, Folloder J, Khouri I, Ueno NT, Mehra R, et al. Risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1999;94:1465–70. doi: 10.1182/blood.v94.4.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zaucha JM, Gooley T, Bensinger WI, Heimfeld S, Chauncey TR, Zaucha R, et al. CD34 cell dose in granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cell grafts affects engraftment kinetics and development of extensive chronic graft-versus-host disease after human leukocyte antigen-identical sibling transplantation. Blood. 2001;98:3221–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Russel N, Gratwohl A, Schmitz N. The place of blood stem cells in allogeneic transplantation. Br J Haematol. 1996;93:747–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Miflin G, Russell NH, Hutchinson RM, Morgan G, Potter M, Pagliuca A, et al. Allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for haematological malignancies—an analysis of kinetics of engraftment and GVHD risk. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:9–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]