Summary

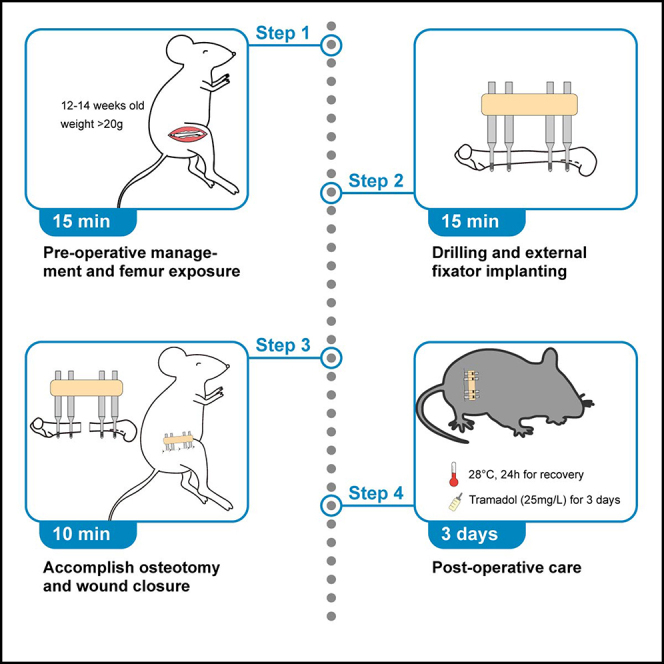

Fracture healing represents a dynamic and complex process which depends on the balanced activities of a broad array of different cell types and signaling pathways. Here, we describe a femoral osteotomy protocol for mice, using an external fixator to stabilize the fractured bone. Depending on experimental requirements, the size of the osteotomy gap can be adjusted. Taken together, this protocol describes a highly standardized and reproducible murine model for morphologic and biomolecular assessment of the fracture healing process.

For complete details on the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Appelt et al. (2020).

Subject areas: Health Sciences, Model Organisms

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Highly standardized and reproducible osteotomy to study fracture healing in mice

-

•

Stable fracture fixation with low risk of displacement, infection, and animal distress

-

•

Adjustable size of the fracture gap depending on experimental requirements

-

•

Easily accessible callus tissue for radiologic, histologic, and biomolecular analyses

Fracture healing represents a dynamic and complex process which depends on the balanced activities of a broad array of different cell types and signaling pathways. Here, we describe a femoral osteotomy protocol for mice, using an external fixator to stabilize the fractured bone. Depending on experimental requirements, the size of the osteotomy gap can be adjusted. Taken together, this protocol describes a highly standardized and reproducible murine model for morphologic and biomolecular assessment of the fracture healing process.

Before you begin

Experimental concerns

-

1.

All experiments require the approval of the local legal representative animal rights protection authorities and need to adhere to the policies and principles established by the animal Welfare Act (Federal Law Gazett I, p.1094) and the national institutes of health guide for care and use of laboratory animals.

-

2.

Mice are usually housed under the condition of 12 h light-dark cycle at a temperature between 22°C–24°C. Avoid transporting mice or changing housing conditions within 3 weeks before the operation.

-

3.

Mice with a minimum age of 12–14 weeks and weight above 20 g are best suited for this particular kind of surgery. Younger mice have insufficient femur length which makes the operation more difficult or even not executable, and may require the use of alternative osteotomy protocols.

Preparation of surgery setup

Timing: 20 min

-

4.

Clean the surgical table and platform, illuminator, vaporizer surface and anesthesia mask with 70% ethanol.

-

5.

Assemble the drill bit and square box wrench into two hand drill holders, respectively. Prepare 30 cm of Gigli wire saw.

-

6.

Prepare sterile 0.9% saline solution, skin disinfectant, clindamycin, buprenorphine and eye ointment. Soak gauze pads with skin disinfection.

-

7.

Prepare sterile surgical instruments, accessories and supplies.

-

8.

Prepare clean cages for housing the mice after surgery. Place several standard food pellets softened with water in a small dish on the bottom of the cage, so that the mice can access the food without bearing any weight on the operated leg.

-

9.

Prepare two heat pads, a small one for the surgical platform, and a larger one underneath the clean cages. Check oxygen supply and isoflurane level in the vaporizer. Ensure that the weight of the filter on the gas scavenger does not exceed the maximum.

-

10.

Cover surgical platform and small heat pad with surgical drape.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Isoflurane | Baxter | HDG9623 |

| Buprenorphine | Bayer | 401513.00.00 |

| Clindamycin | Hikma | 42482.01.00 |

| Bepanthen ® | Bayer | 01580241 |

| Sterile Saline Solution | Braun | 02737756 |

| Betaisodona Solution | Mundipharma GmbH | 04923204 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL6J | The Jackson Laboratory | 000664 |

| Other | ||

| Heat pads | ThermoLux | 461267, 464267 |

| Isoflurane vaporizer | Groppler | F95051-003 |

| Induction chamber | Groppler | UV17006-s |

| Gauze sponges | Fink&Walter | 321024 |

| Scalpel | Braun | 5518040 |

| Scissors | Fine Science Tools | 4058-11 |

| Forceps | Fine Science Tools | 11231-30, 11054-10 |

| MouseExFix simple | RISystem | RIS.611.200 |

| MouseExFix Mounting Pin 0.45 mm | RISystem | RIS.411.100 |

| Square box wrench 0.70 mm | RISystem | RIS.590.112 |

| Drill bit 0.45 mm | RISystem | RIS.590.201 |

| Gigli wire saw 0.7mm | RISystem | RIS.590.120-25 |

| Hand drill | RISystem | RIS.390.XXX |

| Disposable drapes | HARTMANN | 277509 |

| Gas scavenger | Groppler | R546W |

| Filter | Groppler | UV 17012-1XL |

| Mersilene | Ethicon | eh7147h |

Step-by-step method details

Pre-operative management

Timing: 10 min

In this section, we introduce all pre-operative preparations, including drug administration, mouse positioning, anesthesia induction and maintenance and surgical site preparation.

-

1.

Administer Buprenorphine (0.03 mg/kg) subcutaneously 30 min pre-operative to treat moderate to severe pain following surgery.

-

2.

Record the weight of the mouse.

-

3.

Place the mouse in the anesthesia chamber. Set O2 flow to 0.8–1 L/min with 4% of Isoflurane for the induction of anesthesia and change to 1%–2% Isoflurane for maintenance, depending on the weight of the mouse. Measure the anesthetic depth by testing pedal reflex to avoid insufficient anesthesia.

-

4.

Transfer the mouse onto the surgical platform.

-

5.

Administer prophylactic antibiotics, for example Clindamycin (7.5 mg/kg) intraperitoneally.

-

6.

Use eye ointment to protect the eyes from drying.

-

7.

Place the mouse in a lateral position with the hind limb intended for surgery pointing upwards.

-

8.

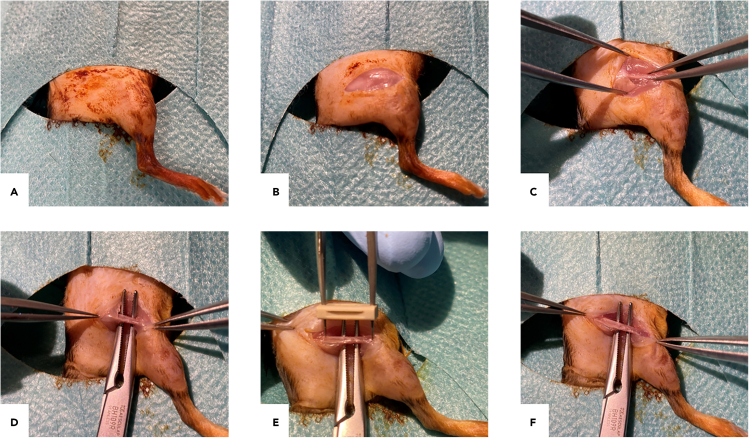

Shave the hair from the intended site of surgical incision and disinfect the skin using gauze pads soaked with antibacterial Betaisodona solution (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Main steps of the exposure of the murine femur

(A) Lateral positioning and skin disinfection.

(B) Lateral longitudinal incision along the femur.

(C) Blunt dissection of the fascia lata to reach the femur using the anatomical gap.

(D) Placement of a curved arterial clamp below the femur.

(E) Measurement whether or not the femur is exposed sufficiently.

(F) Extra exposure of distal and proximal femur if needed.

Exposure of the femur

Timing: approximately 5 min

In this part, we introduce the surgical approach for a sufficient and soft-tissue sparing exposure of the femur, with minimum risk for sciatic nerve injury as well as muscle or skin irritation during drilling and screwing.

-

9.

Make a lateral longitudinal incision using the scalpel along the femur from knee to hip along the iliotibial tract (Figure 1B).

-

10.

Bluntly dissect the fascia lata between skin and muscle with fine forceps and reach the femur using the anatomical gap between vastus lateralis and biceps femoris muscle.

-

11.

Gently scratch along the femur with forceps or pliers to bluntly remove remaining muscle attachments without excessive damage to the periosteum (Figure 1C).

Note: The scratching of the bone surface should be done very carefully and gently. This might also be done with the tips of the forceps only touching the muscle instead of the bone, as the purpose of the scratching is only to remove remaining muscle attached to the femur. Damage of periosteum is unavoidable but should be absolutely minimized.

-

12.

Place a curved arterial clamp below the femur to push away the muscle and skin, which helps to expose the femur sufficiently and avoid sciatic nerve injury (Figure 1D).

Optional: The purpose of using a curved arterial clamp is pushing away the muscle and skin to protect the sciatic nerve. Alternative instruments such as curved forceps or retractors may also be used.

-

13.

Carefully expose the bone surface between patellar groove and lateral epicondyle of the femur with a scalpel.

-

14.

Put the tips of a forceps through the holes on two ends of a fixator (Figure 1E). The distance between the tips of the forceps approximately equals the total length required for insertion of all pins. Measure whether the femur is exposed sufficiently. If required, proceed to slightly and gently expose the proximal femur (Figure 1F).

Drilling and implantation of external fixator

Timing: approximately 15 min

-

15.

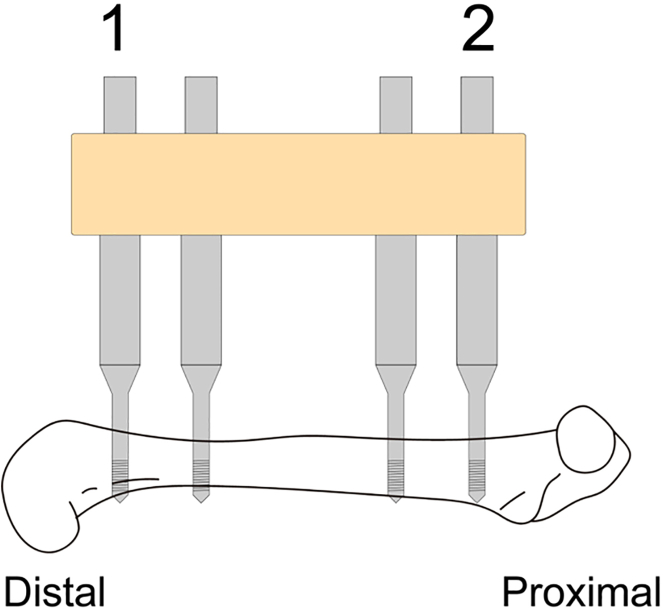

It is essential to insert the first two pins in a specific order. Start with the first pin at the distal femur, followed by the second pin at the proximal femur. The order of inserting the remaining third and fourth pins is irrelevant in our experience (Figure 2).

-

16.

The optimal location of the drill point for the first pin is the distal lateral femur, indicated by the midpoint between patella groove and lateral epicondyle. Drill the first hole (Figure 3A).

CRITICAL: Keep the direction of drilling always vertical to the long axis of femur and bone surface.

CRITICAL: Holding the bone with a forceps close to the drilling point counters the pressure during drilling and prevents the drill bit from wandering. Appropriate pressure during drilling is more important than drilling speed.

Figure 2.

Order of drilling and pin insertion

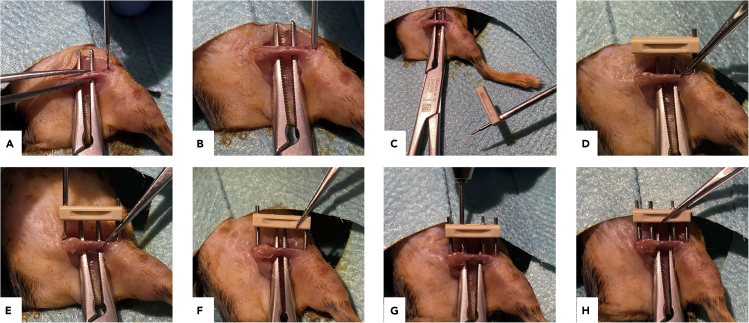

Figure 3.

Main steps of drilling and implantation of the external fixator

(A and B) Drilling the hole for the first pin.

(C) Screwing a pin into the fixator before inserting.

(D) Screwing the assembled part into the femur.

(E) Drilling through the pin bearings in the fixator.

(F) Insertion of the second pin.

(G and H) Drilling and inserting the third and fourth pin.

Note: Drilling through cortical bone is commonly described as feeling a “pop” sensation. Feeling it twice usually indicates that a hole through both cortices of the femur has been drilled successfully, which is essential for optimal stability of the pins (Figure 3B).

-

17.

Before inserting the first pin to the femur, screw it into the fixator until no thread is visible on the top of the pin (Figure 3C).

-

18.

Screw the assembled part into the bone until gentle resistance is experienced.

Note: If the hole is drilled according to the technique described above, the fixator should now be perfectly parallel to the long axis of femur (Figure 3D).

-

19.

Select the drilling point for the second hole at the proximal end of the femur. Make sure to place the drilling point in the middle of this particular bone segment. Drill the second hole through the fixator (Figure 3E).

CRITICAL: The drill should move within the fixator smoothly and without any friction. Otherwise, the fixator and first pin may suffer shear and/or compressive stress, resulting in unpredictable widening of the first hole and reduced pin stability.

-

20.

Insert the second pin (Figure 3F).

-

21.

Drill and insert the third and fourth pin in the order you prefer (Figures 3G and 3H).

Note: In principle, the direction of drilling for the remaining holes is automatically guided through the pin bearings in the fixator, which is well attached to the femur by the first and second pin at this stage. Practically however, there is still some minor degree of angle variation possible, allowing to keep the drill direction always vertical to the bone surface and all drilling points collinear with the first and second pin.

Accomplish osteotomy and wound closure

Timing: approximately 10 min

-

22.

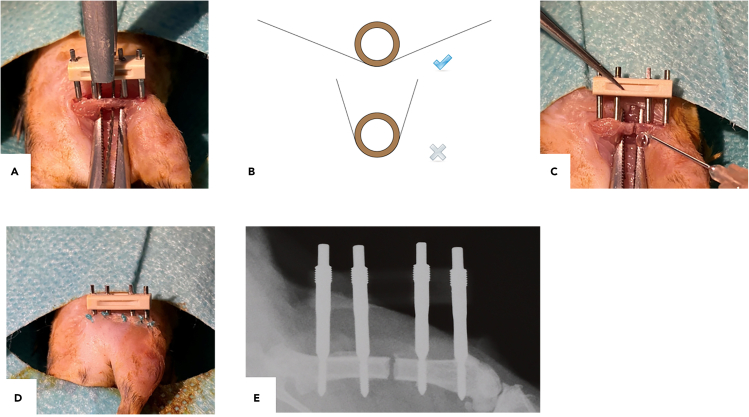

Place the Gigli saw underneath the femur between the tips of the arterial clamp (Figure 4A).

-

23.

Hold the saw as flat as possible and reciprocate the Gigli saw to create a bone defect with limited width according to experimental requirements.

Note: Depending on the experimental design and/or research goal, the size of the osteotomy gap can be easily adjusted through employing alternating diameters of the Gigli wire saw. In our laboratory, we usually employ a 0.7 mm Gigli saw for a standardized osteotomy gap which regenerates through secondary bone healing within 21 days following surgery in mice with a C57Bl/6J genetic background.

CRITICAL: The applied angle of reciprocating the Gigli saw should be as small as possible to minimize the shear stress applied to the femur (Figure 4B). During sawing, always keep the clamp in situ to protect the sciatic nerve from injury while minimizing the risk for muscle and skin damage.

Figure 4.

Main steps of accomplishing the osteotomy

(A) Placement of the gigli saw underneath the femur.

(B) Recommended pattern of sawing.

(C) Flushing the osteotomy gap and open wound with NaCl 0.9%.

(D) Closing the skin.

(E) Representative in vivo X-ray image of osteotomized femur with external fixator in situ immediately after surgery.

-

24.

Flush the osteotomy gap and open wound with NaCl 0.9% to clean out all sawdust (Figure 4C).

-

25.

Close the skin with non-absorbable 4-0 skin suture (Figure 4D).

Note: Suture of the fascia lata or muscle layers may alternatively be applied. In our laboratory, we deliberately do not suture these layers as we have not observed an increased risk of muscular herniation or insufficient soft tissue coverage of the osteotomy. Importantly, sutures of the fascia and/or the vastus lateralis and biceps femoris muscles may result in tissue necrosis and impaired mobility of the mice, negatively affecting fracture healing.

Optional: The postoperative assessment of adequate fracture fixation can be performed using in vivo X-ray to rule out inadequately fixated or displaced osteotomies (Figure 4E).

Post-operative management

Timing: 3 days

-

26.

After the surgical procedure, administer 100 μL saline into the dorsal subcutaneous tissue of the neck and place the mice in cages preheated with a heat pad. Mice should be placed in recovery racks with a temperature of 28 degrees for 24 h.

-

27.

Mice should receive adequate analgesia (e.g., tramadol 25 mg/L in drinking water) for 3 days postoperatively.

-

28.

Postoperatively, mice are fed with soft food pellets placed on the bottom of the cage. Use long nipples for the drinking water bottles so that the mice can easily reach the water.

Expected outcomes

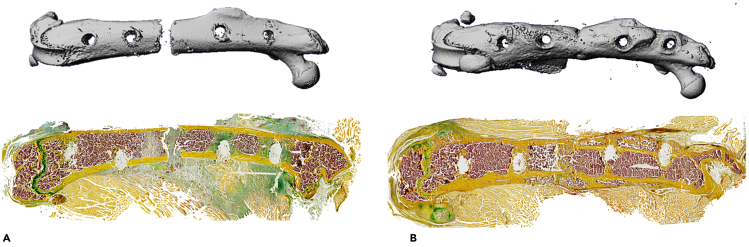

The femur osteotomy generates a defined bone defect stabilized by an external fixator. In this model, secondary bone healing is observed, comprised of overlapping healing stages including 1) acute inflammation (∼ day 7 post-surgery, mostly re-organizing hematoma), 2) formation of the soft callus (∼ day 14 post-surgery, mostly cartilaginous and fibrous tissue), and 3) terminal callus remodeling (∼ day 21 post-surgery, mostly mineralized tissue). The protocol can be used to study the effects of particular treatments or interventions, including feeding of alternative diets, local or systemic application of therapeutic drugs, as well as exposure to various psychosocial conditions or distinct musculoskeletal lesions (Otto et al., 2020; Tsitsilonis et al., 2015). Also, the model is well suited to study fracture healing in mice with global or cell type-specific gene modification (Appelt et al., 2020). To evaluate the healing outcome, we usually carefully dissect and scan the whole femur using μCT. This not only enables the radiologic measurement of static bone parameters of the callus area, but also assessment of adequate fracture fixation. In μCT, a transverse fracture of the midshaft of the femur should be observed in the absence of significant angulation or translation (Figures 5A and 5B upper row). Subsequently, histological processing of usually undecalcified and cryo-embedded callus sections is performed, which allows the histomorphometric quantification of structural and cellular callus parameters (Figures 5A and 5B lower row). Alternatively, callus tissue at the aforementioned, representative timepoints can be used for immunohistochemical or immunofluorescent protein detection in addition to targeted or genome-wide gene expression analysis.

Figure 5.

Expected outcomes of the femur osteotomy

(A) Representative μCT image (longitudinal overview) and histological image (cryo-embedded Movat Pentachrome staining) of osteotomized femur ex vivo at day 7 (acute inflammation stage).

(B) Representative μCT image (longitudinal overview) and histological image (cryo-embedded Movat Pentachrome staining) of osteotomized femur ex vivo at day 21 (remodeling stage).

Limitations

In the presented protocol, the osteotomy is accomplished using a Gigli wire saw. During reciprocating, it is usually not possible to keep the saw path in a perfectly straight line and exactly vertical to the long axis of the femur, resulting in uneven cutting edges of the fracture. Therefore, it is important to perform reciprocating steadily and continuously. Further suggestions are provided in the following troubleshooting section.

Compared to a closed-fracture model, the described osteotomy procedure inevitably results in a higher degree of damage to soft tissue and the periosteum due to the full exposure of the femur, potentially causing impaired bone regeneration and a higher risk of fracture non-union. However, the reproducibility of the fracture type and stability of fixation in closed fracture models is rather limited (Histing et al., 2011). First, a closed fracture model is usually accomplished by a 3-point bending device, resulting in a broad heterogeneity of fracture morphology. Second, the closed fracture is stabilized with intramedullary stainless-steel rods or a pin, both exerting insufficient stability under torsion and shear loading, with unpredictable impact on fracture healing (Histing et al., 2009). And third, the ambulation and knee joint are more likely to be affected in conventional closed fracture models. This is because an intramedullary femoral pin is usually inserted retrograde from the distal femur, requiring dislocation of the patella and damaging the cartilage of the knee joint. This may initiate post-traumatic osteoarthritis, potentially affecting weight bearing and compromising the healing process. In contrast, external fixators provide better fixation stability, and the osteotomy is accomplished in a highly standardized way. During the operation, the knee joint is not affected so that normal mobility is ensured. However, as discussed before, minor damage of the periosteum at the lateral site is unavoidable, even though the procedure has been optimized to minimize periosteal damage. Nevertheless, complex extremity fractures in adult patients, most prone to impaired bone regeneration, can often only be surgically treated through open reduction and internal fixation. As this procedure usually requires the dissection of surrounding soft tissue for the surgical approach and also additional drill holes in the affected bone for plate and bone fragment fixation, the osteotomy model described here closely mimics the actual clinical situation in patients with increased risk of impaired bone healing. Of note, if mouse models with severely reduced bone mass are studied, we recommend the use of closed fracture models, as the pins required for the external fixator do not exhibit sufficient stability and are at risk of dislocation.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

The drill bit keeps wandering across the bone surface.

Potential solution

In most cases, the drilling direction is not perfectly vertical to the bone surface at the drill point, which causes the drill bit wandering. As a consequence, the drilled hole is either not accessible by the pin through the pin bearings in the fixator, or the installed fixator is no longer parallel to the femur. To avoid wandering, apply considerably more pressure during drilling and slowly turn the hand drill. At the same time, hold the femur with forceps near the drill site counteracting the pressure. This problem occurs more often during drilling the second hole in case the angle of the first pin is inappropriate.

Problem 2

Loose pins.

Potential solution

This might occur when turning the drill too much during drilling. Due to the low concentricity of the hand-drill, the hole is widened by excessive turning. First, the trouble shooting described for problem 1 may resolve this problem, as increased pressure and less turning gives greater resistance and stability of the drilled hole. Second, if the drill does not fit through the fixator smoothly, create a notch and drill the second hole with the fixator turned aside. In this case, be very cautious with the direction of drilling as the guidance of the pin bearings in the fixator is missing.

Problem 3

Unexpected fracture occurs when drilling the second pin.

Potential solution

It is of utmost importance to find the right direction of drilling for the first pin, so that there will be a flat bone surface for the second hole. Otherwise, the bone surface for the second pin will be extremely narrow and tilted, making the drilling difficult (e.g., drill bit wandering or occurrence of an unexpected fracture).

Problem 4

Uneven cutting edges of fracture.

Potential solution

Prepare sufficient length of the Gigli wire saw (30–40 cm) and keep it reciprocating in a constant direction and as horizontally as possible, without irritating skin and muscle. Make sure to carefully saw in a consistent manner with low frequency while using the whole length of the wire.

Problem 5

The fracture dislocates once the osteotomy is accomplished.

Potential solution

This occurs when the inserted pin suffers from elastic loading. This could be due to drill bit wandering during drilling through the medial cortical bone, so that the direction of the pin hole on the bone is not in line with the one on the fixator. Once the femur is fractured, the dislocation occurs due to the elastic deformation of pins. Make sure the inserted pin is always vertical to the fixator and the femur axis, in addition to the prevention of drill bit wandering.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be provided by the lead contact, Johannes Keller, (j.keller@uke.de).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (EKFS 2017_A22) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG KE 2179/2-1; TS 303/2-1). The work was conducted in cooperation of the Department of Trauma and Orthopedic Surgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany, with the Center for Musculoskeletal Surgery, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. We thank Xinyue Wang for her contribution to the graphical abstract.

Author contributions

Writing original draft, S.J. and J.K.; writing review and editing, S.J., P.K., A.D., S.T., and J.K.; figure preparation, S.J. and P.K.; funding acquisition and supervision, S.T. and J.K.

Declaration of interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Shan Jiang, Email: s.jiang.ext@uke.de.

Johannes Keller, Email: j.keller@uke.de.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate new code or data.

References

- Appelt J., Baranowsky A., Jahn D., Yorgan T., Kohli P., Otto E., Farahani S.K., Graef F., Fuchs M., Herrera A. The neuropeptide calcitonin gene-related peptide alpha is essential for bone healing. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102970. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto E., Kohli P., Appelt J., Menzel S., Fuchs M., Bahn A., Graef F., Duda G.N., Tsitsilonis S., Keller J. Validation of reference genes for expression analysis in a murine trauma model combining traumatic brain injury and femoral fracture. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:15057. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71895-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsitsilonis S., Seemann R., Misch M., Wichlas F., Haas N.P., Schmidt-Bleek K., Kleber C., Schaser K.D. The effect of traumatic brain injury on bone healing: an experimental study in a novel in vivo animal model. Injury. 2015;46:661–665. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Histing T., Garcia P., Holstein J.H., Klein M., Matthys R., Nuetzi R., Steck R., Laschke M.W., Wehner T., Bindl R. Small animal bone healing models: standards, tips, and pitfalls results of a consensus meeting. Bone. 2011;49:591–599. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Histing T., Holstein J.H., Garcia P., Matthys R., Kristen A., Claes L., Menger M.D., Pohlemann T. Ex vivo analysis of rotational stiffness of different osteosynthesis techniques in mouse femur fracture. J. Orthop. Res. 2009;27:1152–1156. doi: 10.1002/jor.20849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate new code or data.