Abstract

Background:

Functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) Panometry assesses the esophageal response to distention and may complement the assessment of primary peristalsis on high-resolution manometry (HRM). We aimed to investigate whether FLIP Panometry provides complementary information in patients with normal esophageal motility on HRM.

Methods:

Adult patients that completed FLIP and had an HRM classification of normal motility were retrospectively identified for inclusion. 16-cm FLIP studies performed during endoscopy were evaluated to assess EGJ distensibility, secondary peristalsis, and identify an abnormal response to distention involving sustained LES contraction (sLESC). Clinical characteristics and esophagram were assessed when available.

Results:

Of 164 patients included (mean(SD) age 48(16) years, 75% female), 111 (68%) had normal Panometry with EGJ-distensibility index (DI) ≥2.0 mm2/mmHg, maximum EGJ diameter ≥16mm and antegrade contractions. Abnormal EGJ distensibility was observed in 44/164 (27%), and 38/164 (23%) had an abnormal contractile response to distension. sLESC was observed in 11/164 (7%). Among 68 patients that completed esophagram, abnormal EGJ distensibility was more frequently observed with an abnormal esophagram than normal EGJ opening: 14/23 (61%) vs 10/45 (22%); P=0.003. Epiphrenic diverticula was present in 3/164 patients: 2/3 had sLESC.

Conclusions & Inferences:

Symptomatic patients with normal esophageal motility on HRM predominantly have normal FLIP Panometry, however abnormal FLIP findings can be observed. While abnormal Panometry findings appear clinically relevant via an association with abnormal bolus retention, complementary tests, such as provocative maneuvers with HRM and timed barium esophagram, are useful to determine clinical context.

Keywords: dysphagia, peristalsis, impedance, achalasia

Introduction

Esophageal high-resolution manometry (HRM) is generally considered the primary method to assess for esophageal motility disorders. While the current manometric approach that focuses on assessment of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation and peristalsis during swallowing is helpful in defining esophageal motor disorders per the Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders v3.0 (CC v3.0), it may not be sufficient to fully characterize esophageal motor function.1, 2

The functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) provides a method to assess the esophageal response to distention via FLIP Panometry. The esophageal response to distension is an important component of esophageal function as distension should lead to triggering of secondary peristalsis to remove retained or refluxed bolus. Abnormalities of secondary peristalsis may be associated with both dysphagia and reflux pathology,3, 4 and this component of esophageal function is ignored during current manometric assessment as it requires a more detailed and invasive manometric protocol. By generating a sustained volumetric distention and plotting the diameter changes along a space-time continuum, Panometry can describe esophageal motility akin to manometry and also determine the opening parameters of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) during both passive distention and when esophageal contractions occur.5, 6 This approach represents a complementary tool that can address the limitations of manometry in defining secondary peristaltic triggering and opening dimensions of the EGJ.

Initial studies using Panometry have shown that assessment of EGJ distensibility can effectively identify patients with achalasia and help with identification of esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO) in equivocal cases.6–8 Additionally, a contractile response pattern associated with repetitive antegrade contractions (RACs) during sustained volumetric distention has been defined as a physiomarker of normal esophageal body function while an absent contractile response to volumetric distention was associated with abnormal acid exposure.9–11 However, abnormal EGJ distensibility was also identified in patients that did not have achalasia, thus the clinical implication of abnormal EGJ distensibility in the setting of normal LES relaxation on HRM was unclear.6, 11 Additionally, we have observed a unique motor pattern that involves contraction of the LES during distension with FLIP: a pattern we describe as a sustained LES contraction (sLESC); the clinical associations and consequence of this finding are undescribed. Given these initial findings, we hypothesize that abnormalities in EGJ distensibility and secondary peristalsis defined by FLIP Panometry may complement characterization of motor function in patients with esophageal symptoms and a normal HRM. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe the esophageal response to distension and associated clinical characteristics of a cohort of symptomatic patients with normal esophageal motility on HRM.

Methods

Subjects

Adult patients (age 18–89) presenting to the Esophageal Center of Northwestern for evaluation of esophageal symptoms between November 2012 and December 2019 who completed FLIP during upper endoscopy and HRM were prospectively entered into an esophageal motility registry. After excluding patients with previous foregut surgery, previous pneumatic dilation, eosinophilic esophagitis, severe reflux esophagitis (LA-classification C or D), hiatal hernia > 3cm, or evidence of mechanical obstruction on the endoscopy (e.g. esophageal stricture) performed with FLIP, the registry was reviewed to identify patients with normal motility on HRM as defined by CC v3.0.2

Additional clinical evaluation (e.g. barium esophagram) was obtained and management decisions made at the discretion of the primary treating gastroenterologist. The study protocol was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

FLIP Study Protocol and Analysis

The FLIP study using 16-cm FLIP (EndoFLIP® EF-322N; Medtronic, Inc, Shoreview, MN) was performed during sedated endoscopy as previously described.6, 9 Endoscopy performed in the left-lateral decubitus position was generally performed using conscious sedation with midazolam and fentanyl; other medications, e.g. propofol, were also used with monitored anesthesia care (MAC) with propofol at the discretion of the performing endoscopist in some cases. Although these medications used for endoscopic sedation can alter esophageal motility, the patterns of motility during the FLIP protocol are reproducible and have been shown to predict motility patterns during standard manometry performed without these medications.6, 9, 12, 13 With the endoscope withdrawn and after calibration to atmospheric pressure, the FLIP was placed transorally and positioned within the esophagus with 1–3 impedance sensors beyond the EGJ with this positioning maintained throughout the FLIP study. Stepwise 10-ml FLIP distensions beginning with 40 ml and increasing to target volume of 60 or 70 ml were then performed; each stepwise distension volume was maintained for 30–60 seconds.

FLIP data were exported and analyzed using a customized program (available open source at http://www.wklytics.com/nmgi) to generate FLIP Panometry plots.8, 14 The FLIP analysis included the 50–70ml FLIP fill volumes as lower fill volumes were recognized to be susceptible to movement artifact.

Analysis of EGJ opening with FLIP Panometry

The EGJ analysis specifically focused on the EGJ distensibility index (DI) at the 60ml FLIP fill volume and the maximum (max) EGJ diameter that was achieved during the 60ml or 70ml fill volume (Figure 1). First, areas at the EGJ that were affected by dry catheter artifact (i.e. artifact that impacts diameter measurement when occlusion of the FLIP balloon disrupts the electrical current utilized for the impedance planimetry technology) were omitted from the EGJ analysis.

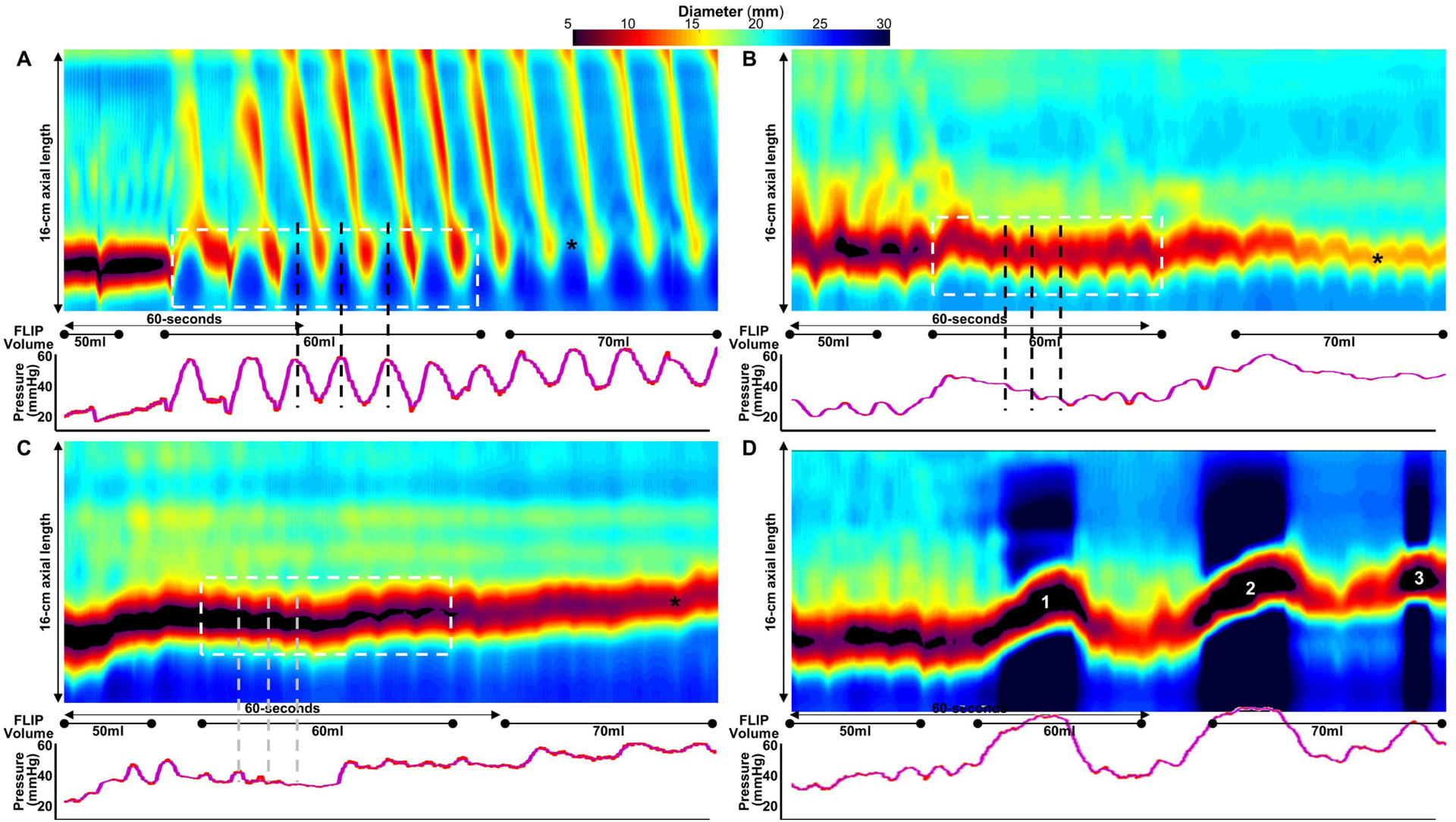

Figure 1. Patterns of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) response to distension.

Functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) Panometry output from four patients with normal motility on manometry (A-D) is displayed as length (16-cm) × time × color-coded diameter FLIP topography (top panels) with corresponding intraballoon pressure (bottom panel). EGJ-distensibility index (DI) was assessed during the 60-ml fill volume (dashed box) as the median of three values obtained during the peaks (i.e. greatest diameters) of EGJ opening (dashed vertical lines: A-C); maximum EGJ diameter is marked by “*”. A. Normal EGJ opening with EGJ-DI of 5.8 mm2/mmHg and maximum EGJ diameter of 22mm. The normal EGJ-diameter-pressure relationship involves EGJ opening (diameter increase) associated with increase in intraballoon pressure - dashed vertical lines reflect peaks of EGJ diameter align with peaks in pressure. B. Borderline reduced EGJ opening (EGJ-DI of 1.8 mm2/mmHg) while a maximum EGJ diameter of 14.6mm is achieved (*). C. Reduced EGJ opening with EGJ-DI 0.6 mm2/mmHg with low maximum EGJ diameter (9.3mm). D. Sustained lower esophageal sphincter contraction (sLESC) are observed (numbered 1,2,3). Note the reduction in diameter that occurs within the EGJ that is associated with an increase in intraballoon pressure. sLESC #1 and #2 occur shortly after filling of the FLIP of 60 and 70ml, respectively, while sLESC 3 occurs at the stable 70ml fill volume. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

FLIP studies (50–70ml FLIP fill volumes) were then manually reviewed for the presence of sLESC (Figure 1D) and sustained occluding contractions (SOCs; Figure 2E). SLESC was considered present when there was a transient reduction in diameter attributed to the LES (i.e. not associated with respiration and crural contraction) that was associated with an increase in intraballoon pressure (Figure 1). The categorization of sLESC also required that the response was independent of an antegrade contraction in the esophageal body and lasted longer than 5 seconds. The sLESC response sometimes carried a similar appearance to the LES-lift previously described on FLIP in achalasia, though occurred with or without proximal migration and was differentiated as a distinct entity among this cohort of patients with normal LES relaxation on HRM.10 A SOC was defined as a non-propagating, occluding contraction of the esophageal body that persisted for >10 seconds, occurred in continuity with the EGJ, and was associated with a pressure increase >35 mmHg (Figure 2).10, 15 As both sLESC and SOC appear to represent abnormal contractile responses to LES distension, parameters of EGJ opening (i.e. EGJ-DI and max EGJ diameter) were not applied in these cases which were instead considered independently abnormal.

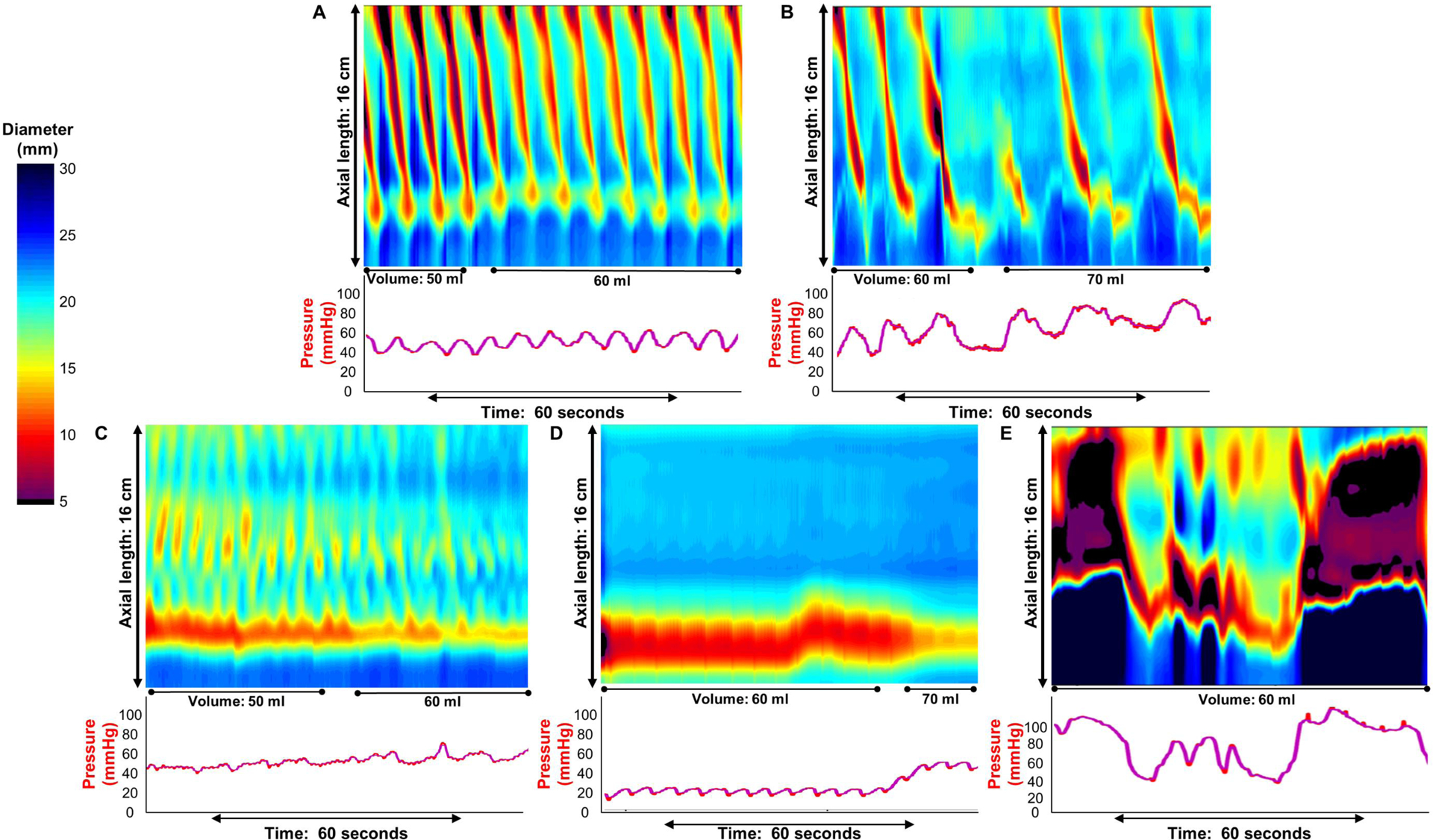

Figure 2: Examples of contractile patterns on functional luminal imaging probe Panometry.

FLIP Panometry output from five patients (A-E) with normal motility on high-resolution manometry is displayed as length (16-cm) × time × color-coded diameter FLIP topography plots (top panels) with corresponding intraballoon pressure (bottom panel). The contractile response was determined from contractile activity observed during the 50ml through 70ml fill volumes of the FLIP study protocol. A) Normal contractile response (NCR) was defined as the presence of a repetitive antegrade contraction (RAC) pattern that met the Rule-of-6s: duration of at least 6 consecutive antegrade contractions that spanned at least 6 cm in axial length occurring with a rate of 6 ± 3 contractions per minute. B) Borderline diminished contractile response (BDCR) was defined as the presence of at least one distinct antegrade contraction of at least 6 cm in axial length, but not meeting the RAC Rule-of-6s. C) Impaired disordered contractile response was defined as presence of contractility, but not meeting criteria for NCR, BDCR, or spastic-reactive contractile response (SRCR). D) Absent contractile response was defined by absence of contractions. SRCR was defined in E by the presence of a sustained occluding contraction (SOC). Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern Medicine.

The first 5 seconds after achieving the 60ml fill volume were then omitted from analysis to avoid incorporation of active-filling effects. The EGJ-DI was then measured during the 60ml FLIP fill volume dependent on the FLIP contractile response pattern. If antegrade contractions were present, three measures of EGJ-DI (EGJ-cross sectional area divided by pressure) were obtained at the peak EGJ diameter that occurred during the pressure up-slope or pressure peak associated with antegrade contractions (as in Figure 1A). If antegrade contractions were not occurring during the 60ml fill volume, three measures of EGJ-DI were obtained during expiration or between EGJ contractions (as in Figures 1B and C). The median of the three DI values was then applied for analysis.

An abnormal EGJ response to distension was defined as presence of sLESC or SOC (spastic-reactive response) or with abnormal EGJ opening: reduced EGJ opening (REO) if EGJ DI was <2.0 mm2/mmHg and maximum EGJ diameter <12mm and borderline EGJ opening if EGJ-DI was <2.0mm2/mmHg and maximum EGJ-diameter was <16mm (but not meeting criteria for REO). Normal EGJ opening was defined as EGJ-DI ≥2.0 mm2/mmHg and max EGJ diameter ≥16mm.

Analysis of the contractile response to distension with FLIP Panometry

Esophageal body contractility was identified by a transient decrease in the luminal diameter in ≥3 adjacent impedance planimetry channels (i.e. ≥3 cm axial length). The direction of contractions (antegrade or retrograde) was categorized based on a tangent line placed at the onset of contraction. The contractile response to distension were further categorized as repetitive if contractions of similar directionality occurred consecutively at a consistent time interval and then by contraction direction (antegrade or retrograde). The rate of repetitive contractions was derived by dividing the number of repetitive contractions by duration (time) of repetitive contraction pattern and then normalized to reflect the rate of contractions as the number of contractions per minute. The repetitive antegrade contractions (RACs) pattern was specifically identified using the RAC Rule-of-6s (Ro6s) as a) duration of ≥6 antegrade contractions that were b) ≥6-cm in axial length, and c) occurred at a regular rate of 6 (+/−3) antegrade contractions per minute.10, 14 A repetitive retrograde contractions (RRCs) pattern was defined when retrograde contractions of ≥6 axial length occurred at a rate of >9 contractions per minute. SOCs were defined as above.10, 15

The contractile response to distension was classified to assess the spectrum of secondary peristaltic response, i.e. transitioning from normal to abnormal (Figure 2; Table 1). Normal contractile response (NCR; defined by RAC Ro6s) and borderline diminished contractile response (BDCR) both included distinct antegrade contractions and were patterns observed among asymptomatic volunteers.9, 10 Contractile response patterns not observed among asymptomatic volunteers, and thus considered ‘abnormal’, included impaired disordered contractile response (IDCR), absent contractile response (ACR), or spastic-reactive contractile response (SRCR; which shared features with findings observed in spastic achalasia); Figure 2; Table 1.10, 15 FLIP Panometry studies were collectively reviewed by 4 physicians (AJB, END, JEP, DAC) and the FLIP pattern was determined by consensus agreement among the reviewers.

Table 1. Panometry Contractile Response Patterns.

The contractile response to distension was based on evaluation of the FLIP study protocol including from the 50ml to 70ml fill volume. AC-Antegrade contractions. RC-retrograde contractions. RACs - Repetitive ACs. RRCs – Repetitive RCs. SOCs- sustained occluding contractions. sLESC – sustained lower esophageal sphincter contraction.

| Panometry Contractile Response Patterns | Definition |

|---|---|

|

Normal Contractile Response

NCR |

RAC-Rule of 6s (Ro6s)

|

|

Borderline/Diminished Contractile Response

BDCR |

|

|

Impaired/Disordered Contractile Response

IDCR |

|

|

Absent Contractile Response

ACR |

|

|

Spastic-Reactive Contractile Response

SRCR |

|

HRM protocol and analysis

After a minimum 6-hour fast, HRM studies were completed using a 4.2-mm outer diameter solid-state assembly with 36 circumferential pressure sensors at 1-cm intervals (Medtronic Inc, Shoreview, MN). The HRM assembly was placed trans-nasally and positioned to record from the hypopharynx to the stomach with approximately three intragastric pressure sensors. After a 2-minute baseline recording, the HRM protocol was performed with ten, 5-ml liquid swallows in the supine position.2 Additionally, a rapid-drink challenge (RDC) involving rapid drinking of 200cc liquid in the seated upright position was generally performed (RDC was deferred or not tolerated by some patients). Manometry studies were analyzed using ManoView version 3.0 analysis software (Medtronic) according to the Chicago Classification v3.0.2 The RDC was analyzed by measurement of the integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) and for presence of pan-esophageal pressurization (PEP) at an isobaric contour >30 mmHg. An RDC with IRP > 12mmHg or PEP presence was considered abnormal.16, 17

Additional Clinical Evaluation

Timed barium esophagram (TBE) with barium tablet was obtained in patients at the discretion of the patients’ treating physicians. The barium column height above the EGJ was measured from images obtained at 1, 2 and 5 minutes after ingestion of 200 mL barium. A 12.5 mm barium tablet was also administered, and images obtained at timed intervals until passed into the stomach. Abnormal esophagram was considered with barium retention at 1 minute for TBE or with delayed passage of the barium tablet. Presence of epiphrenic diverticula was also included among abnormal esophagram.

Subjects completed validated self-reported symptom scores, Brief Esophageal Dysphagia Questionnaire (BEDQ) and GerdQ on the day of HRM.18, 19 Some patients chose not to complete the symptom questionnaires, and thus scores were not available for all subjects. The BEDQ included eight 6-point Likert scale questions (scored 0–5) that assessed the frequency and severity of dysphagia over the preceding 14-days; items were summed to yield scores ranging from 0 (asymptomatic) – 40, with greater scores indicating greater dysphagia severity. The GERDQ is a 6-item self-report measure used to support GERD diagnosis. The items assess the frequency of symptoms and medication use over the preceding 7 days, and the GERDQ score is generated by summing four graded Likert scale items of four positive predictors (scored 0–3) and two reverse Likert scale items of negative predictors (scored 3-0).18

Statistical Analysis

Results were reported as percentage, mean (standard deviation; SD), or median (interquartile range; IQR) depending on data distribution. Groups were compared using Chi-square test for categorical variables and ANOVA and t-test versus Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U for continuous variables, depending on data distribution. Post-hoc testing was generally not performed after ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis due to small sub-group sample sizes. Analyses assumed a 5% level of statistical significance.

Results

Subjects

164 patients, mean (SD) age 48 (16) years, 75% female, that had normal motility on HRM and completed FLIP Panometry were identified that met criteria for inclusion (Table 1). HRM was performed on the same day as FLIP in 85% of patients and at a median (IQR) interval of 1.9 (0.9–4.8) months in the remainder. 68 patients also completed a TBE with tablet; the median (IQR) interval between FLIP and esophagram was 1.3 (0.3–2.7) months.

EGJ distensibility on FLIP Panometry among patients with normal motility on HRM

Among the 164 patients, sLESC was observed in 11 patients (7%). SLESC occurred early after incremental FLIP filling (i.e. within 10 seconds of reaching the stepwise fill volume) in all 11 patients; sLESC occurred again later during stable fill volume in 9/11 (82%); Figure 3. SLESC occurred at the 60 ml and/or 70ml fill volume in all 11 patients; sLESC also occurred at the 50ml fill volumes in 2/11 (18%) patients. SOC was observed in 3 patients (one also had sLESC).

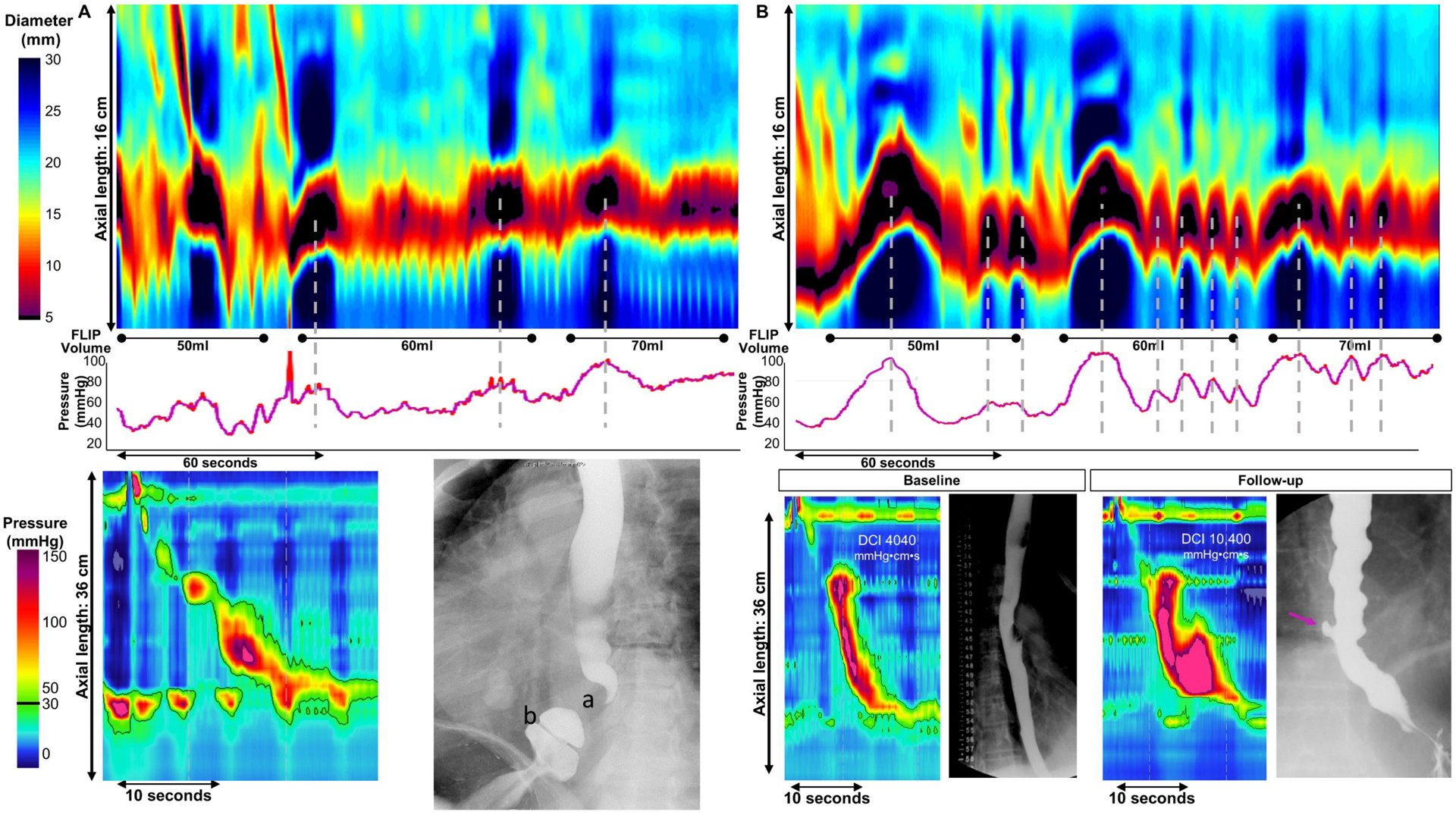

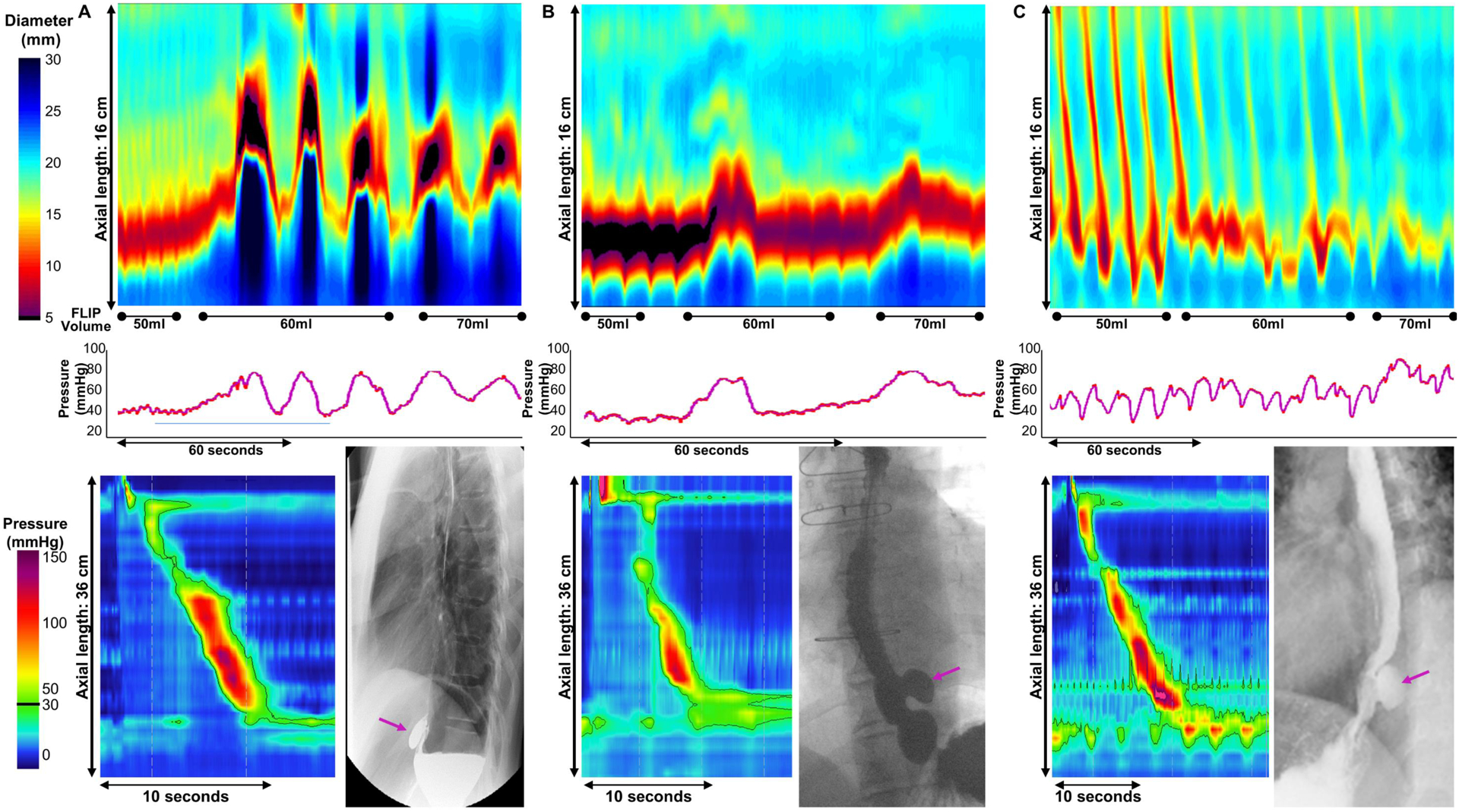

Figure 3: Sustained lower esophageal sphincter contraction (sLESC).

Examples of two patients (A,B) presenting with dysphagia with sLESC observed on FLIP Panometry (top panel) with associated high-resolution manometry (HRM) and esophagram (bottom panels). sLESC presence and relationship with intraballoon pressure are represented by vertical dashed lines. A). sLESC occurred shortly after FLIP filling to 60ml, again during 60ml fill volume, and after filling to 70ml. HRM demonstrated a small hiatal hernia with normal motility. With abdominal compression on esophagram, hiatal hernia was induced with demonstration of a widely patent Schatzki’s ring (b: luminal diameter measured 21mm) while the LES A-ring contracted (a). No ring nor hiatal hernia was observed during endoscopy, but dilation to 20mm was performed without generation of heme. No change in symptoms was reported at follow-up. B).Prominent sLESC were observed shortly after filling to 50, 60, and 70ml fill volumes, while less vigorous appearing sLESC occurred repetitively during the stable fill volumes. During baseline testing (bottom left) completed near the time of FLIP, the patient had a normal timed barium esophagram beyond some tertiary contractions noted, as well as normal motility on HRM. Progressive symptoms prompted repeat testing 6 months later, at which time a small diverticulum was apparent on esophagram (arrow); repeat HRM yielded a diagnosis of hypercontractile esophagus based on 7/10 supine swallows with distal contractile integral (DCI) >8000 mmHg-s-cm. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern Medicine.

Among the 151 patients without sLESC or SOC, the mean (SD) EGJ-DI was 4.7 (2.2) mm2/mmHg and the mean (SD) maximum EGJ diameter was 18.7 (3.1) mm. An EGJ-DI <2.0 mm2/mmHg was observed in 19/151 (13%) patients and an EGJ-DI <3.0 mm2/mmHg was observed in 42/151 (28%); Supplemental Figure 1. A maximum EGJ diameter <12mm was observed in 5/151 (3%) patients; all 5 also had EGJ-DI <2.0 mm2/mmHg. Nine (6%) had maximum EGJ diameters <13mm and 29/151 (19%) had a maximum EGJ diameter <16mm.

Thus, normal EGJ opening was observed in 120/164 (73%) patients and an abnormal EGJ response to distension was observed in 44/164 (27%) patients (Table 2). Patients with an abnormal EGJ response to distension were older (mean (SD) age 57 (16) vs 45 (15) years; P<0.001), less frequently female (27/44, 61% vs 93/210, 78%) and had greater body mass index (median (IQR) 27 (23–30) vs 24 (21–28) kg/m2; P=0.026). Greater RDC-IRP (median (IQR) 4 (2–8) vs 2 (0–4) mmHg; P=0.006) and higher frequency of obstruction suggested by RDC (9/38, 24% vs 10/110, 9%; P=0.045) was observed with abnormal EGJ response to distension than in normal. Clinical and manometric characteristics otherwise did not differ between with abnormal and normal EGJ response to distension (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with normal motility on high resolution manometry (HRM) by esophagogastric junction (EGJ) opening assessment with FLIP Panometry.

| Group | Total cohort | Spastic-reactive | Reduced EGJ opening | Borderline EGJ opening | Normal EGJ opening |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLIP Panometry EGJ response to distension | sLESC or SOC | EGJ-DI <2.0 mm2/mmHg and max EGJ diameter <12mm | EGJ-DI <2.0 mm2/mmHg OR max EGJ diameter <16mm (but not REO) | EGJ-DI ≥2.0 mm2/mmHg and max EGJ diameter ≥16mm | |

| N,n | 164 | 13 | 5 | 26 | 120 |

| Age (yrs), mean (SD) | 48 (16) | 67 (12) * | 56 (10) | 52 (18) | 45 (15) |

| Gender (female), n (%) | 120 (73) | 8 (62) | 4 (80) | 15 (58) * | 93 (78) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 25 (22–28) | 26 (23–29) | 27 (26–30) | 26 (23–31) | 24 (21–28) |

| Other | 2 (1) | 1 (8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| median (IQR) | 8 (3–18) | 6 (2–23) | 21 (12–23) | 8 (1–18) | 8 (3–17) |

| Monitored anesthesia care | 13 (8) | 1 (8) | 0 | 4 (14) | 8 (7) |

| Epiphrenic diverticulum | 3 (2) | 2 (15) * | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| RDC-PEP, n/nb(%) | 14/148 (10) | 3/11 (27) * | 1/5 (20) | 3/22 (14) | 7/110 (6) |

| Tablet retention, n/nc(%) | 9/68 (13) | 1/7 (14) | 0/3 (0) | 5/13 (39) * | 3/45 (7) |

Bolded values indicate P<0.05 on comparison with normal EGJ opening (NEO); reduced EGJ opening (REO) was not subjected to statistical comparison due to sample size (n=5).

Dysphagia with or without co-occurring reflux symptoms or chest pain.

n(%) of patients that completed rapid drink challenge (RDC).

n(%) of patients that completed timed barium esophagram (TBE) with barium tablet. BEDQ - Brief Esophageal Dysphagia Questionnaire. DI –distensibility index. IRP – integrated relaxation pressure. PEP – panesophageal pressurization. sLESC - sustained lower esophageal sphincter contraction. SOC – sustained occluding contraction.

Contractile response patterns on FLIP Panometry among patients with normal motility on HRM

Antegrade contractions were observed on FLIP Panometry in 126/164 (77%) patients: 70/164 (43%) had NCR (e.g. Figure 2A) and 56/164 (34%) had BDCR (e.g. Figure 2B) patterns. Thus, the remaining 38/164 (23%) patients had abnormal contractile response patterns (Figure 2 C–E): 20/164 (12%) patients had an IDCR pattern, 13/164 (8%) patients had SRCR, and 5/164 (3%) patients had ACR. Of note, RRCs (as defined) were not observed in this cohort.

Patients with NCR or BDCR contractile response patterns were younger (mean (SD) 46 (15) vs 56 (17) years; P=0.001) and more frequently female (99/126, 77% vs 21/38, 55% female; P=0.007) than patients with abnormal contractile response patterns (i.e. IDCR, SRCR, or ACR). Differences between specific contractile patterns (Table 3) were observed in age and gender, and there was a trend toward difference in presence of hiatal hernia on HRM (P=0.065).

Table 3.

Clinical and manometric characteristics by FLIP Panometry contractile response pattern.

| Contractile response pattern | Normal contractile response | Borderline diminished contractile response | Impaired disordered contractile response | Spastic-Reactive contractile responsea | Absent contractile response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 70 | 56 | 20 | 13 | 5 |

| Age (yrs), mean (SD) * | 42 (15) | 52 (15) | 52 (15) | 67 (12) | 45 (20) |

| Gender (female), n (%) * | 50 (71) | 49 (88) | 12 (60) | 8 (62) | 1 (20) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 24 (21–28) | 25 (20–31) | 26 (23–30) | 26 (23–29) | 25 (23–30) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (8) | 0 |

| median [IQR] | 8 (3–18) | 13 (4–18) | 8 (0–17) | 6 (2–23) | 14 (6–29) |

| Monitored anesthesia care | 3 (4) | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | 1 (8) | 1 (20) |

| Epiphrenic diverticulum | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (15) | 0 |

| Median DCI, mmHg•cm•s, median (IQR) | 1715 (1219–2584) | 1968 (997–3293) | 1563 (909–2046) | 2675 (1132–3327) | 598 (534–2907) |

| Tablet retention, n/nb(%) | 4/25 (16) | 2/26 (8) | 2/8 (25) | 1/7 (14) | 0/2 (0) |

| Maximum EGJ diameter, mm, median (IQR) * | 20 (19–21) | 19 (17–21) | 16 (14–18) | na | 15 (11–15) |

(bold) P<0.05 for comparison across five groups.

Note redundancy in reporting with Table 1, but included here for comparison.

P = 0.065 for comparison across five groups.

n(%) of patients that completed timed barium esophagram (TBE) with barium tablet. BEDQ - Brief Esophageal Dysphagia Questionnaire. DCI – distal contractile integral. DI - distensibility index. EGJ – esophagogastric junction. HRM - high resolution manometry. IRP – integrated relaxation pressure. na – not applied. TBE - Timed barium esophagram.

Association of EGJ opening with contractile response to distension

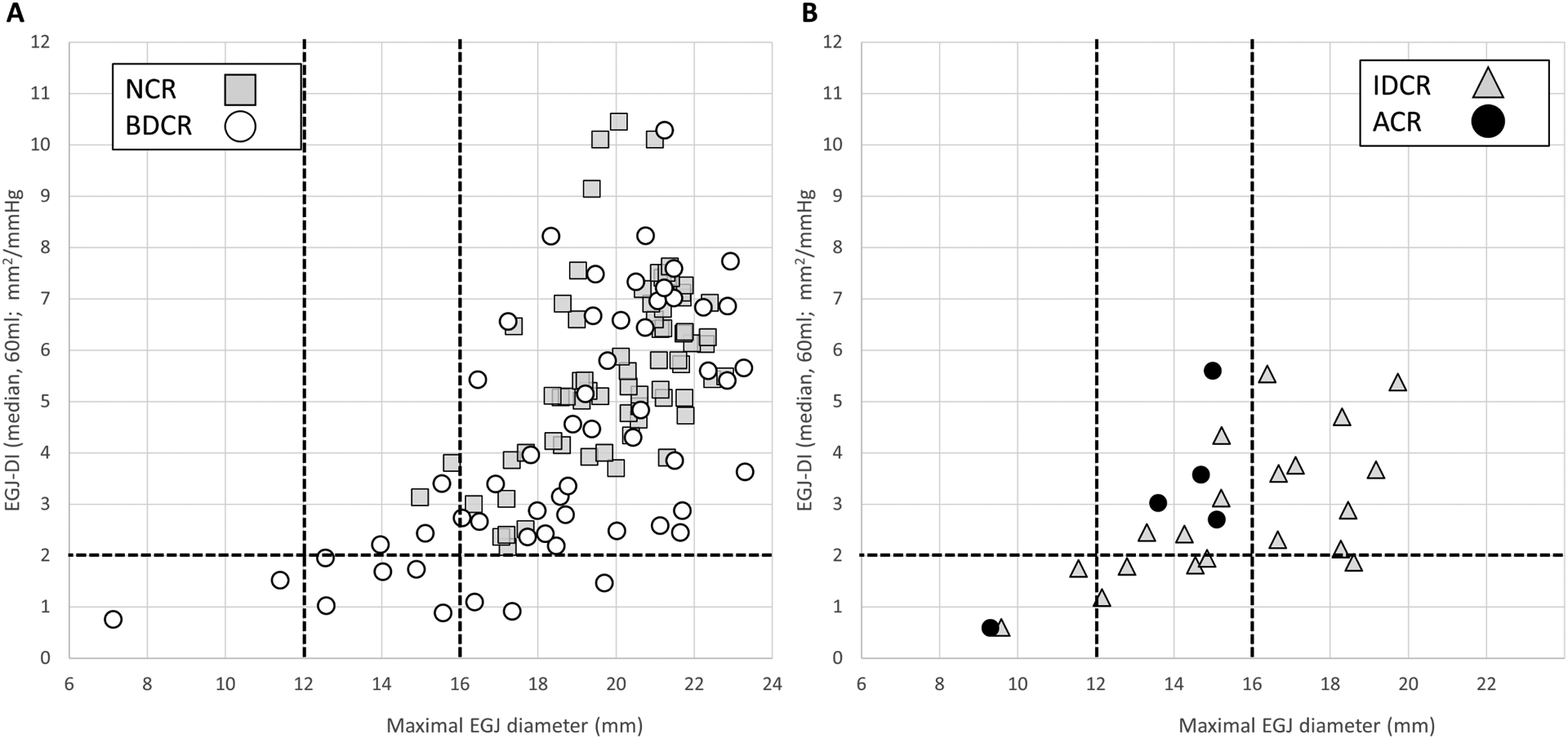

EGJ-DI and maximum EGJ diameter were greater in patients with antegrade contractions on FLIP (NCR or BDCR) than in patients with abnormal contractile responses to distension (IDCR, ACR): EGJ-DI, mean (SD): 5.0 (2.2) mm2/mmHg vs 2.9 (1.4) mm2/mmHg (p<0.001); maximum EGJ diameter, median (IQR) 20.0 (18.1–21.3) mm vs 15.1 (13.5–17.7) mm (P<0.001); Figure 4. Patients with normal EGJ opening more frequently had antegrade contractions, 111/120 (93%) had NCR or BDCR patterns on FLIP Panometry, than patients with an abnormal EGJ response to distension, 15/44 (34%) had NCR or BDCR patterns (p<0.001). Of the 5 patients with reduced EGJ opening, 2 had BDCR, 2 had IDCR, and 1 had ACR.

Figure 4: Association of esophagogastric junction (EGJ) distensibility parameters to contractile response to distension among patients with normal motility on high-resolution manometry.

EGJ-distensibility index (DI) by maximum EGJ diameter on functional luminal imaging probe Panometry are plotted for patients with antegrade contractions in response to distension (normal contractile response, NCR, or borderline diminished contractile response, BDCR) in A and patients with an abnormal contractile response in B: impaired disordered contractile response (IDCR)and absent contractile response (ACR). FLIP Panometry EGJ opening parameters were not applied to patients with spastic-reactive contractile response given the contractile response to distension involving the lower esophageal sphincter, and thus are not displayed here. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern Medicine.

Of the 5 patients with an ACR pattern on FLIP Panometry, 1 had reduced EGJ opening and the other 4 had borderline EGJ opening. Of the patients with IDCR, 1/20 had reduced EGJ opening, 10/20 (50%) had borderline EGJ opening, and 9/20 (45%) had normal EGJ opening.

Esophagram findings among patients with normal motility on HRM

Of the 68/164 (41%) patients that completed TBE, 24/68 (35%) patients had an abnormal finding. Abnormal esophagram findings included epiphrenic diverticula in three patients. Abnormal contrast retention occurred in 16 patients: two patients had retention at 5 minutes (column heights 7cm and 8cm) and 14 patients had contrast retention observed at 1 minute: median (range) column height 10 (2–16 cm). Nine patients had delayed tablet passage: impaction of the tablet occurred in 1/9 patient while transient delayed passage occurred in 8/9 patients.

Among the 68 patients that completed TBE, 14/23 (61%) that had an abnormal EGJ response to distension had an abnormal esophagram while only 10/45 (22%) with normal EGJ opening had an abnormal esophagram; P = 0.003. There was also a difference in frequency of abnormal TBE across the specific classifications of EGJ opening (Table 2); P=0.010. Abnormal liquid barium retention occurred in 9/23 (39%) of patients with an abnormal EGJ response to distension and 7/45 (16%) with normal EGJ opening; P=0.039. Abnormal tablet passage occurred in 6/23 (26%) with an abnormal EGJ response to distension and 3/45 (7%) with normal EGJ opening; P=0.052.

Two of the three patients with epiphrenic diverticulum had sLESC (Figure 5). The other patient with epiphrenic diverticula had an EGJ-DI of 2.4 mm2/mmHg with max EGJ diameter 17mm and NCR.

Figure 5. Patients with epiphrenic diverticula and normal motility on manometry.

Panometry (top panel) and associated esophagram and high-resolution manometry (HRM) in bottom panel from three patients (A,B,C) with epiphrenic diverticula. In all three patients, HRM demonstrated normal motility and epiphrenic diverticula was appreciated on both endoscopy (not pictured) and esophagram (arrow). A). Sustained lower esophageal sphincter contraction (sLESC) occurred after filling to 60ml and occurred again during the stable 60ml fill volume, as well as shortly after achieving and during the 70ml fill volume. B). sLESC occurred after filling to 60ml and 70ml C). EGJ-DI was 2.4 mm2/mmHg and maximum EGJ diameter was 17.6mm. SLESC was not observed. There was a normal contractile response. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern.

Discussion

In this cohort study of 164 symptomatic patients with normal motility on HRM as defined by CC v3.0, there was overall good agreement between FLIP Panometry and HRM. 68% had a normal esophageal response to distension with normal EGJ opening and antegrade contractions (NCR or BDCR) while the remainder had abnormal EGJ opening or an abnormal contractile response to distension. Abnormal EGJ-distensibility observed among the symptomatic patients in this cohort carried an association with abnormal esophagram findings. Further, we described a unique motor pattern that involves contraction of the LES during distension with FLIP (sLESC) and we propose a classification scheme of the contractile patterns of the response to distension observed on Panometry that reflects a potential pathophysiologic transition. These findings support that an assessment of EGJ distensibility and the esophageal contractile response to volumetric distention can complement HRM by confirming normal function. FLIP Panometry may also uncover defects in EGJ mechanics and secondary peristalsis that may represent physiologic abnormalities in patients in which a functional esophageal disorder could potentially be considered.20

We recently described the manometric findings of 111 symptomatic patients with normal FLIP Panometry as defined by the RAC Ro6s and normal EGJ opening. Of these patients with normal FLIP Panometry in this previous study, 79% had normal or borderline esophageal dysmotility on HRM while the remaining discrepant group still carried a clinical impression of normality and were treated conservatively, i.e. as if the HRM was of normal motility.6 Thus, it was suggested that a normal upper endoscopy and RAC Ro6s pattern on FLIP Panometry could obviate the need for a HRM and direct treatment toward GERD or a functional disorder. The present study again supports this approach as the majority of patients with normal motility on HRM also had a normal motor response to distension on FLIP Panometry.

We also previously reported abnormal esophageal motility, including reduced EGJ distensibility or an abnormal contractile response, on FLIP in 52% of 29 patients with normal motility on HRM.6 In the present study, we further expand upon our earlier work and introduce updated approaches to focus on the important group of patients that have normal LES relaxation and normal primary peristalsis on manometry, but reduced EGJ distensibility and/or an abnormal contractile response during FLIP Panometry. As patients with achalasia consistently have abnormal EGJ opening on FLIP and also an abnormal contractile response to distension, there is some apparent overlap in FLIP Panometry patterns in a portion (29/164, 18%) of this cohort of symptomatic patients with normal motility on HRM.7, 10, 21, 22 However, these patients do not have achalasia as they have normal deglutitive LES relaxation observed on HRM. Thus, an abnormal response to distension in isolation should not warrant achalasia-type intervention (i.e. these FLIP findings in isolation should not lead to LES myotomy). Nevertheless, abnormal EGJ-distensibility observed among these symptomatic patients appeared to be clinically relevant and carried clinical consequence with an association with abnormal esophagram findings including esophageal retention and epiphrenic diverticula. Lending additional support to the potential physiologic relevance of abnormal EGJ distensibility was the association with abnormal, obstructive findings on provocative HRM maneuver, RDC. Thus, when abnormal FLIP studies are encountered, clinical correlation with HRM is essential and additional evaluation with esophagram and longitudinal follow-up are warranted. However, future research to better characterize these patients is also warranted as these patients can represent a confusing entity akin to EGJ outflow obstruction on HRM.2

An important concept related to evaluation of the esophageal response to distension is that manometry and FLIP Panometry fundamentally assess different physiologic events within the same organ: Manometry assesses LES relaxation and primary peristalsis triggered by swallowing while FLIP Panometry assesses EGJ distensibility and secondary peristalsis during a sustained volumetric distention. Thus, although patients with an increased IRP are more likely to have lower EGJ distensibility, the measurement of EGJ distensibility is not the same as the IRP on HRM; these parameters assess different components of esophageal function. EGJ distensibility is determined by the forces resisting opening during distention while the IRP is assessing tone in the LES and the intrabolus pressure during primary peristalsis. Thus, disease states associated with poor LES relaxation, such as achalasia, will have decreased EGJ distensibility. However, there are likely additional etiologies for reduced EGJ distensibility beyond impaired delgutitive LES relaxation, such as those related to inflammation, fibrosis, or hypertrophy. Additionally, an excitatory (e.g. contractile) response to distention of the LES may be involved.

The unique motor pattern of sLESC reported here, likely represents the exaggerated form of an LES contractile response to distension. This garners interest as it was not a response observed among asymptomatic volunteers and also appears to be associated with the presence of epiphrenic diverticula in patients with otherwise normal HRM.9, 23 While the underlying mechanisms for the sLESC response remain unclear, we hypothesize that this is a hyperactive response to the distension of the LES and/or distension of the proximal stomach, which may be further exaggerated during distension of intrathoracic stomach if hiatal hernia is present (such as in Figure 3A). The SOC pattern may represent a similar process that also involves the distal esophageal body.10, 15 SLESC primarily occurred shortly after active volumetric filling potentially supporting a reactive nature. Abdominal compression has been shown to increase LES pressure, likely as a reflex anti-reflux mechanism, and a similar process may be involved in the elicitation of sLESC or SOC.24 These patterns could also reflect a spastic motor process involving the LES, which is supported by the observation of occurrence during stable fill volumes and at times repetitively, as well as their similar appearance to the LES-lift previously observed in achalasia on both Panometry and HRM.10, 25, 26 Age-related changes in esophageal motility could also be a contributing factor. Ultimately, future research is needed to improve understanding of this response to distension. Given the clinical uncertainty at present, the observation of sLESC or SOC should prompt evaluation and clinical correlation with HRM and/or TBE.

With regard to peristalsis, the differences in triggering primary versus secondary peristalsis are likely important factors in explaining why patients can have normal peristalsis with impaired secondary peristalsis. Our results of subjects with NCR to volumetric distention will frequently have normal peristalsis during swallowing supports the presence of RACs suggests normal neurogenic and myogenic functional capacity in the esophageal body. Further, our results suggesting that 23–57% of patients with normal primary peristalsis may have defects in secondary peristalsis are consistent with previous data reported by Schoeman and Holloway that suggested that approximately half of the patients that underwent balloon distention had normal secondary peristalsis on manometry and the other half had either failed or disordered contractions.3 In contrast, we have also reported instances where patients with absent contractility on manometry, but have evidence of peristalsis on FLIP Panometry.14, 27 The reason for this discordance is more likely mechanical as manometry is dependent on contact with the manometry catheter and FLIP Panometry can detect non-contact (i.e. non-occluding) contractions in the lumen when there is dilation.

While this study carries value in describing a novel FLIP Panomery approach in an important clinical cohort, this study does carry limitations. Although patients were evaluated in a prospective manner, the study analysis was retrospective and descriptive in nature. Thus, management decisions were at the discretion of the treating gastroenterologist and standardized management plans or outcome assessment (e.g. responses to targeted interventions such as dilation) were not available. Similarly, other components of clinical information, such as esophagram, were not universally available. Additionally, this cohort represents a tertiary referral population, and thus the frequency of some of the findings (e.g. epiphrenic diverticula rate) may not be generalizable to other practices. However, the goal of this study was to report and describe the patterns of the esophageal response to distension via FLIP Panometry in patients with normal motility on HRM to inform practitioners of a potential pitfall in diagnosing achalasia using the EGJ-DI measures alone, as well as to identify areas in need of future investigation.

Overall, a recommended approach and clinical application includes that if FLIP Panometry is normal on a normal index endoscopy, a major esophageal motor may be reliably excluded.14 As such, the subsequent evaluation and management plan can be directed toward reflux and/or functional etiologies. However, if abnormal FLIP Panometry findings are observed on an index endoscopy, directed dilation could be considered at the time of that endoscopy if the max EGJ diameter is less than 16–18 mm. If other initial data (e.g. TBE and endoscopic appearance) provides a high pre-test probability for achalasia, an abnormal FLIP Panometry may suffice to reach the diagnosis. However, if clinical uncertainty remains, there should be recognition that abnormal FLIP Panometry can occur in patients with normal motility on HRM and thus the abnormal FLIP Panometry findings should prompt additional evaluation with HRM and/or TBE. Additionally, in patients that have a previous HRM that is normal on 10 supine swallows (per CCv3.0), but clinical uncertainly persists (e.g. related to clinical presentation, abnormalities observed on provocative HRM maneuvers, or abnormal esophagram findings), FLIP Panometry may help clarify the overall clinical impression.

In conclusion, most patients with normal motility on HRM as defined by CC v3.0 have a normal FLIP Panometry assessment. Further, abnormal EGJ opening mechanics or an abnormal contractile response to distension (which may involve the LES via sLESC or SOC) may be observed among patients with normal LES function on manometry. While these findings on FLIP Panometry in the setting of a normal HRM are unlikely to be achalasia (and thus should not prompt achalasia-type intervention in isolation), abnormal EGJ distensibility is clinically relevant based on the associated abnormal esophagram findings. Thus, these results support the utility of complementary and comprehensive evaluation in symptomatic patients in which a single test is unrevealing. While this study did not allow targeted therapy for these abnormalities, future studies should focus on the potential impact of targeting abnormal EGJ distensibility, as well as developing an improved understanding of the associated mechanisms for this response through pharmacologic and physiologic investigation.

Supplementary Material

Supplement 1. Esophagogastric junction (EGJ) opening parameters among patients with normal motility on high-resolution manometry (HRM). The EGJ-distensibility index (DI) obtained as the median value during the 60ml FLIP fill volume is plotted by maximum EGJ diameter achieved during the 60ml or 70ml fill volumes. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern Medicine.

Grant support:

This work was supported by P01 DK117824 (JEP) from the Public Health service and American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award (DAC).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

DAC and JEP hold shared intellectual property rights and ownership surrounding FLIP panometry systems, methods, and apparatus with Medtronic Inc.

DAC: Medtronic (Speaking, Consulting)

WK: Crospon, Inc (Consulting)

JEP: Crospon, Inc (stock options), Given Imaging (Consulting, Grant, Speaking), Sandhill Scientific (Consulting, Speaking), Takeda (Speaking), Astra Zeneca (Speaking), Medtronic (Speaking. Consulting), Torax (Speaking, Consulting), Ironwood (Consulting), Impleo (Grant).

AJB, AK, END: nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Pandolfino JE, Ghosh SK, Rice J, Clarke JO, Kwiatek MA, Kahrilas PJ. Classifying esophageal motility by pressure topography characteristics: a study of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(1):27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(2):160–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Secondary oesophageal peristalsis in patients with non-obstructive dysphagia. Gut. 1994;35(11):1523–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoeman MN, Holloway RH. Integrity and characteristics of secondary oesophageal peristalsis in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1995;36(4):499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson DA, Lin Z, Rogers MC, Lin CY, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Utilizing functional lumen imaging probe topography to evaluate esophageal contractility during volumetric distention: a pilot study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(7):981–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson DA, Kahrilas PJ, Lin Z, et al. Evaluation of Esophageal Motility Utilizing the Functional Lumen Imaging Probe. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1726–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rooney KP, Baumann AJ, Donnan E, et al. Esophagogastric Junction Opening Parameters are Consistently Abnormal in Untreated Achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Triggs JR, Carlson DA, Beveridge C, Kou W, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Functional Luminal Imaging Probe Panometry Identifies Achalasia-Type Esophagogastric Junction Outflow Obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlson DA, Kou W, Lin Z, et al. Normal Values of Esophageal Distensibility and Distension-Induced Contractility Measured by Functional Luminal Imaging Probe Panometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(4):674–81 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson DA, Kou W, Pandolfino JE. The rhythm and rate of distension-induced esophageal contractility: A physiomarker of esophageal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020:e13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson DA, Kathpalia P, Craft J, et al. The relationship between esophageal acid exposure and the esophageal response to volumetric distention. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraichely RE, Arora AS, Murray JA. Opiate-induced oesophageal dysmotility. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(5):601–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mittal RK, Frank EB, Lange RC, McCallum RW. Effects of morphine and naloxone on esophageal motility and gastric emptying in man. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31(9):936–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumann AJ, Donnan EN, Triggs JR, et al. Normal Functional Luminal Imaging Probe Panometry Findings Associate With Lack of Major Esophageal Motility Disorder on High-Resolution Manometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson DA, Kou W, Rooney KP, et al. Achalasia subtypes can be identified with functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) panometry using a supervised machine learning process. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020:e13932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ang D, Hollenstein M, Misselwitz B, et al. Rapid Drink Challenge in high-resolution manometry: an adjunctive test for detection of esophageal motility disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krause AJ, Su H, Triggs JR, et al. Multiple rapid swallows and rapid drink challenge in patients with esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction on high-resolution manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020:e14000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonasson C, Wernersson B, Hoff DA, Hatlebakk JG. Validation of the GerdQ questionnaire for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(5):564–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taft TH, Riehl M, Sodikoff JB, et al. Development and validation of the brief esophageal dysphagia questionnaire. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(12):1854–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aziz Q, Fass R, Gyawali CP, Miwa H, Pandolfino JE, Zerbib F. Functional Esophageal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandolfino JE, de Ruigh A, Nicodeme F, Xiao Y, Boris L, Kahrilas PJ. Distensibility of the esophagogastric junction assessed with the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) in achalasia patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(6):496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rohof WO, Hirsch DP, Kessing BF, Boeckxstaens GE. Efficacy of treatment for patients with achalasia depends on the distensibility of the esophagogastric junction. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(2):328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlson DA, Gluskin AB, Mogni B, et al. Esophageal diverticula are associated with propagating peristalsis: a study utilizing high-resolution manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(3):392–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodds WJ, Hogan WJ, Miller WN, Stef JJ, Arndorfer RC, Lydon SB. Effect of increased intraabdominal pressure on lower esophageal sphincter pressure. Am J Dig Dis. 1975;20(4):298–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwiatek MA, Post J, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. Transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation in achalasia: everything but LOS relaxation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(12):1294–e123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mittal RK, Karstens A, Leslie E, Babaei A, Bhargava V. Ambulatory high-resolution manometry, lower esophageal sphincter lift and transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(1):40–6, e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson DA, Lin Z, Kahrilas PJ, et al. The Functional Lumen Imaging Probe Detects Esophageal Contractility Not Observed With Manometry in Patients With Achalasia. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1742–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement 1. Esophagogastric junction (EGJ) opening parameters among patients with normal motility on high-resolution manometry (HRM). The EGJ-distensibility index (DI) obtained as the median value during the 60ml FLIP fill volume is plotted by maximum EGJ diameter achieved during the 60ml or 70ml fill volumes. Figure used with permission from the Esophageal Center of Northwestern Medicine.