Abstract

Introduction and importance

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a myeloproliferative disorder characterized by increased platelet count and a high risk of bleeding or thrombotic events due to platelet dysfunction. Patients with ET are treated according to their risk of complications with cytoreductive or anti-aggregant treatment. Neither guidelines for oncologic patients nor perioperative management of patients with ET have been determined.

Case presentation

A 41-year-old female patient with ET who had alternating constipation and diarrhea was referred after a screening colonoscopy diagnosing a locally advanced rectosigmoid junction colon adenocarcinoma with liver metastases. Systemic preoperative chemotherapy was indicated. The patient underwent laparoscopic low anterior resection plus volume-preserving right lobectomy of the liver. Postoperative bleeding of the internal iliac artery (IIA) associated with hematoma at the lower pelvic cavity was diagnosed and treated by interventional radiology; the patient was discharged without other complications 16 days after surgery.

Clinical discussion

ET has been related to the development of hematologic complications or second non-hematologic malignancies. A systematic review was conducted to seek guidance for the management of such patients in the perioperative period. Special perioperative care must be taken, and complications management should avoid further hemorrhages or cloth formation.

Conclusion

Under oncologic and hematological guidance, minimally invasive surgery and non-invasive management of complications are advised in the lack of published perioperative management guidelines of ET patients with colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Essential thrombocythemia, Colorectal cancer, Abdominal surgery, Postoperative bleeding

Highlights

-

•

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a rare clonal myeloproliferative disorder.

-

•

ET can manifest as hemorrhage, thrombosis, and functional microvascular symptoms.

-

•

Cytoreductive treatment and anti-aggregants are indicated in ET with a high risk of complications.

-

•

Colorectal cancer, with its surgical and oncologic treatment, may increase the risk of adverse vascular events.

-

•

Perioperative management of patients with ET has not been determined.

1. Introduction

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is a rare clonal myeloproliferative disorder characterized by a sustained excessive proliferation of megakaryocytes in the bone marrow and an increased serum platelet level. ET has been associated with myeloproliferative syndromes like chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, myeloid metaplasia, and other secondary malignancies often described as a premalignant stage with a low risk of progression [1], [2]. Currently, there are no clinical guidelines published regarding the perioperative management of ET patients. We conducted a systematic review of the literature and presented a case, in line with SCARE [3] criteria, of ET with a rectosigmoid junction adenocarcinoma and liver metastasis laparoscopically resected, complicated by pelvic bleeding managed in a private specialized cancer center hospital.

2. Clinical case

A 41-year-old female patient with essential thrombocytosis (ET) who had alternating constipation, diarrhea, and anal discomfort was referred after being diagnosed with a large colon mass during colonoscopy for screening. The mass was circumferential and ulcerofungating moderated-differentiated adenocarcinoma, located at the rectosigmoid junction (AV: 18 cm).

She was diagnosed with ET in 2004, treated with hydroxyurea (HU) 0.5 mg, agrylin 1 mg BD and aspirin 100 mg OD since dating of diagnosis. OB/GYN's previous history of childbirth in 2011 with no previous miscarriages. JAK2 gene mutation test confirmed ET diagnosis in 2012 after later pregnancies presented leakage symptoms and vaginal bleeding leading to abortion in 2 opportunities and one dilatation and curettage until second childbirth in 2016. ET treatment previous to surgery based on agrylin 1 mg 0D and aspirin 100 mg OD, HU was discontinued during the second pregnancy attempt. Family history of colorectal cancer (grandfather), no other relevant or genetic diseases. No previous history of smoking, alcohol, or other drugs.

Initial physical exam reported a palpable mass at left upper abdominal quadrant and normal digital rectal exam. Serum CEA was 120 ng/mL, and her serum hemoglobin level was 12.9 g/dL, WBC 7 × 103/L, platelets 920 × 103/L, PT (INR) 13.4 s (1.08), PTT 36.6 s. A computed tomographic + MRI scan of the abdomen identified a circumferential wall thickening at the rectosigmoid junction with pericolic fat infiltration and multiple regional lymphadenopathies. Liver CT + MRI scan reported a 5.1 cm sized probable metastasis in S7 and splenomegaly (21 cm) with partial ischemia at the superior pole of the spleen. CT chest HR study with no definite evidence of metastasis in the thorax.

Systemic chemotherapy was indicated after a multidisciplinary team meeting, receiving E-FOLFIRI (#8, Erbitux + Irinotecan HCl + leucovorin + 5FU). After 8 cycles, an evaluation was done by CT + MRI scans, reporting a similar extent of rectosigmoid junction cancer with pericolic fat infiltration and several regional lymphadenopathies, further decreased hepatic metastasis in S7 no changes in spleen alterations.

Laparoscopic low anterior resection (LAR) with lymph node dissection (LND) plus volume-preserving right lobectomy of the liver was indicated. It was ordered to stop aspirin five days before surgery. The patient was explained the risks of thrombosis/bleeding before and after surgery. To prevent thrombosis, we performed laparoscopic surgery using an elastic stocking and intermittent pneumatic compression with pneumoperitoneum. LAR with LND was performed by a senior colorectal surgeon expert in minimally invasive surgery, finding severe splenomegaly (21 cm), redundant T-colon and D-colon, splenic flexure was not mobilized, resection with IMA high ligation, and IMV preservation. The liver surgical team performed a hybrid volume-preserving right hemi-hepatectomy (Fig. 1). Hemostatic agents were used to preventing bleeding complications: fibrin sealant in lateral pelvic walls, IMA and IMV roots, and collagen matrix to prevent anastomotic bleedings.

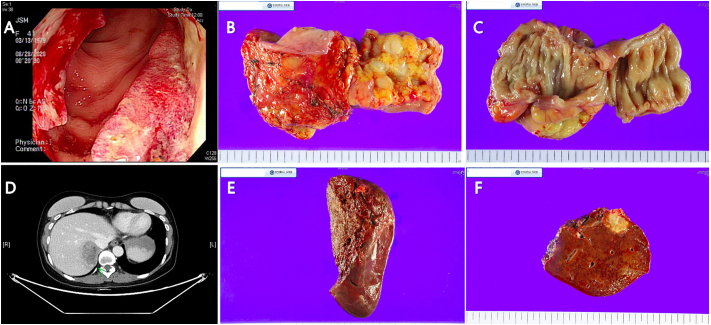

Fig. 1.

Surgical staging. 1A. Colonoscopy finding of ulcerofungating mass. 1B and 1.C. Sigmoid adenocarcinoma moderately differentiated (Mandard grade 4). 1D CT scan.

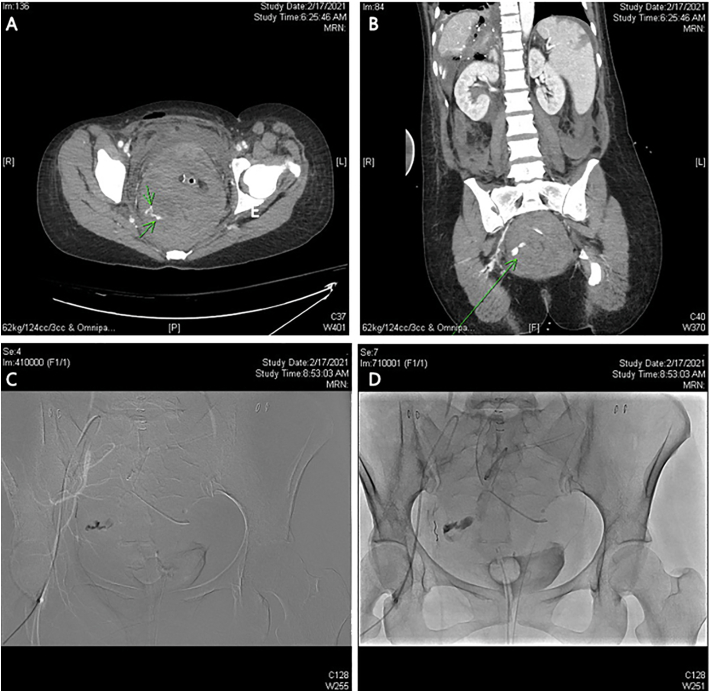

On the immediate postoperative day, the patient presented tachycardia with low Hb (6.6 g/dL) with normal BP, receiving a transfusion of 6 pRBCs and nine transfusions of FFP. Hemovac drained 160-200 mL serohematic fluid every 2 h to a total of 1.5 L. Hemodynamic conditions were closely monitored. Given hemodynamic stability with normal BP, prompt dynamic CT was indicated, showing active contrast extravasation at the right side of the lower pelvic cavity in a right internal iliac artery (IIA) branch associated with hematoma at the lower pelvis and fluid collection at the subhepatic space and abdominal-pelvic cavity. Immediate vessel embolization was done under US and fluoroscopy guidance. Right IIA angiography revealed bleeding at the anterior branch; the select feeder branch was selected, and embolization was performed with a coil (tornado 2–3) and glue (1:2). Bilateral IIA angiography no longer presented bleeding after embolization (Clavien Dindo IIIB [4]) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Dynamic CT with active contrast extravasation probably at the branch of right internal iliac artery 2B Lower pelvic cavity hematoma. 2C Internal iliac artery.

The patient remained hospitalized for 16 days until complete recovery without new symptoms of bleeding or thrombosis. Bowel function was recovered early with active walking. Thrombocytosis raised to high preoperative levels Aspirin intake (100 mg OD) was indicated on POD 14 for thromboprophylaxis. The intraabdominal hematoma was conservatively managed with passive drains until its complete removal.

Pathologic examination of the colon specimen revealed an infiltrating ulcerofungating moderately-differentiated adenocarcinoma with extramural vascular invasion without lymphovascular nor perineural invasion, measuring 2.6 cm × 2.1 cm × 1.0 cm (Fig. 1). Metastasis in 4 out of 15 regional lymph nodes (ypN2a) was found. The specimen was diagnosed as an adenocarcinoma stage IVa (T4a N2a M1) [5].

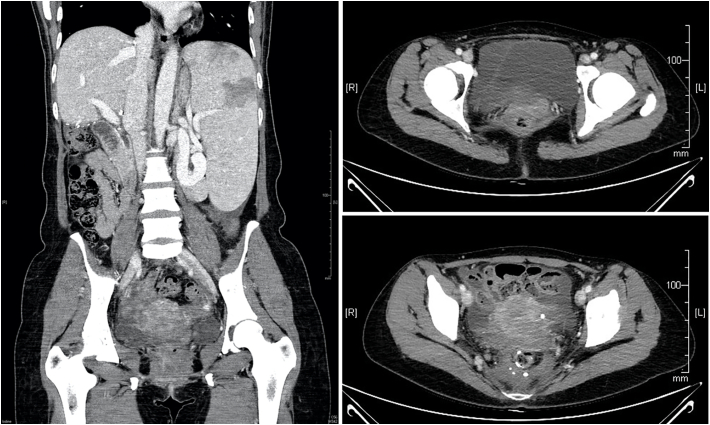

After surgical treatment, adjuvant chemotherapy and surveillance were indicated according to NCCN guidelines for colon cancer management [5], and cytoreductive and anti-aggregation treatment was resumed with anagrelide 1 mg OD and aspirin 100 mg OD. The patient was re-evaluated in a follow-up consult three months after surgery, manifesting no pain, good tolerance to oral intake, regular bowel movements without incontinence symptoms, and overall satisfied with the treatment and outcomes. A CT scan showed almost complete reabsorption of the pelvic hematoma, and a platelet count was 320 × 103/L under Agrylin treatment (Fig. 3). Future surveillance will follow NCCN guidelines for colon cancer [6] requiring history and physical examination every 3–6 months for two years by the oncologist, colorectal surgeon, and hematologist with CEA, chest/abdominal/pelvic CT scan for each evaluation; then every 6–12 months for a total of 5 years.

Fig. 3.

CT showing resolution of lower pelvic cavity hematoma with intact anastomotic stapling line.

3. Discussion

A systematic literature review was conducted using EMBASE, Medline, and PubMed databases to detect relevant English language articles. Published studies with full-text articles were included. The following search terms were used: “essential thrombocythemia” OR “primary thrombocytosis” AND “surgery” OR “surgical” OR “operation” OR “operative.” Studies on abdominal surgery were manually retrieved, and bibliographies were checked for other relevant publications.

A total of 263 studies were initially found. Based on the inclusion criteria, seven studies described abdominal surgery in patients with ET and were included (Table 1). Based on the data, 6/7 patients were female, and the mean age was 48 years. Only four patients had a previous medical history of complications related to ET. Three patients had previous anti-aggregation treatment, which was suspended perioperative; 2 of these patients had anagrelide intake associated.

Table 1.

Description and summary of previous reports. Perioperative data.

| Case report reference | Year of publication | Age/sex | Surgery performed | Esplenomegaly | Previous complication | Medical treatment | Preoperative platelet count (×103/L) | Perioperative thromboprofilaxis | Postoperative complication | Management of complication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wada [12] | 1998 | 52/F | Cholecystectomy and choledochotomy | Yes | None | None | 1300 | Low molecular weight heparin, ceased after bleeding | Abdominal bleeding (Drain insertion wound) | Reoperation for hemostasis and intaabdominal hematoma evacuation |

| Cai [13] | 2009 | 36/F | Splenectomy and mesocaval shunt with prosthetic graft | Yes | Previous history of vascular thrombosis | None | 313 | Low-dose heparin. When platelet count increased to 1137109 L1, aspirin commenced | Pseudohyperkalemia | None |

| Amarapukar [14] | 2013 | 38/F | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | Yes | Hematemesis | None | 280 | Low molecular weight heparin after thrombosis diagnosed | Budd-Chiari syndrome (1. hepatic venous thrombosis with occlusion of all the three veins and a pat- ent portal venous system) 2. angioplasty thromobsis |

1. Hepatic veins Angioplasty 2. transjugular intrahepatic porta caval shunt (TIPS) |

| Zhu [15] | 2017 | 61/F | Laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy | Yes | None | Preoperative plateletpheresis | 915 | None | Anastomotic bleeding | Dilute noradrenaline as a retention enema, and 0.5 U of hemocoagulase was injected. |

| Hiyoshi [16] | 2019 | 40/F | Laparoscopic ileocecal resection | NR | None | aspirin (100 mg/day) and anagrelide (2.5 mg/day) | 624 | Elastic stocking and intermittent pneumatic compression | Asymptomatic thrombocytopenia | None |

| Hosada [17] | 2021 | 68/M | Esplenectomy | Yes | Acute hearth failure induced by anagrelide | aspirin (100 mg/day) | 854 | None | Bleeding from the drain insertion site and wound, epistaxis, and hemorrhoidal bleeding | Reoperation for hemostasis and intaabdominal hematoma evacuation |

| Kim (current case) | 2021 | 41/F | Laparoscopic low anterior resection with lymph node dissection | Yes | 3 miscarriages (2 abortions, 1 Dilatation and curetagge) | aspirin (100 mg/day) and anagrelide (2.5 mg/day) | 920 | Elastic stocking and intermittent pneumatic compression | Abdominal bleeding | Angiography and vessel embolization under US and fluoroscopy guidance. |

Regarding complication risk, two patients could be considered low-risk, three intermediate-risk, and one high-risk. Laparoscopic surgery was performed in 4 patients, and open surgery was done in the other three patients. Three patients received pharmacological thromboprophylaxis, and 2 received mechanical pneumatic intermittent compression.

Four patients experienced postoperative bleeding that occurred on the first postoperative day. One presented a thrombotic event (Budd-Chiari syndrome), one showed only pseudo hyperkalemia without further complications, and one presented asymptomatic thrombocytopenia. No clear guidelines for managing patients undergoing abdominal surgery were available to base the management of ET patients.

Platelet disorder is now considered to be only a part of the general proliferative abnormality. Patients with ET may have sustained elevations in platelet counts, with counts ranging from 1,000,000 to 5,000,000 per mL [7]. Clinically, the malfunction of these dysfunctional platelets can produce hemorrhage, thrombosis, and microvascular functional symptoms such as visual disturbances, hearing, and vasomotor disorders with paresthesia or vertigo [8].

Many platelets appear large and bizarre and are often found in clumps. These patients rarely bleed spontaneously, although they usually exhibit unusual bleeding after trauma and minor surgical procedures [9]. The hemostatic defect is complex and variable, and all tests may be normal. However, there is a prolonged bleeding time and abnormal clot retraction, occasionally positive tourniquet test [9].

Paradoxically, a high level of malfunctioning platelets interferes with agglutination and coagulation normal process. Platelet hypoaggregation is detected in a range of 38% to 94% of these patients [8]. Due to this, surgical hemostasis is compromised by: the dysfunction of mechanical plugging of defects, the release of vasoconstrictor substances, and the activation of plasma thromboplastic factors to initiate coagulation [9].

The most representative data of surgical interventions in ET and Policitemia Vera (PV) patients was published in 2008 with a total of 311 surgical interventions (150 with ET diagnosis) [10]. Abdominal surgery was performed in 91/311 patients with 91 laparoscopic interventions. It was reported a total of 7.7% of vascular occlusions (venous or arterial thrombotic events) and 7.3% major hemorrhages (defined as intracranial, ocular, articular, or retroperitoneal bleeding, events that require surgery or angiographic intervention or any bleeding that causes a hemoglobin reduction of 2 g/dL or more that involves transfusion of 2 or more blood units) without correlation with diagnosis, surgical intervention, thromboprophylaxis or previous medical treatment [10].

Even though a high platelet count (>600 × 103/μL), age >60 years, and thrombosis history are high-risk factors for spontaneous bleeding or thrombotic episodes in ET patients, no correlation between hemorrhagic complications and the degree of thrombocytosis has been found [7], [10].

Only seven abdominal surgery cases with an associated ET diagnosis have been reported [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], 4 of them presenting bleeding as a postoperative complication. Currently, there are no perioperative indications for emergency plateletpheresis, thromboprophylaxis, or suspension of previous treatments.

ET can be divided into three clinical categories: those presenting as a bleeding tendency, those presenting as thrombosis, or having no symptoms [8]. The risk of complication events can also be stratified. Asymptomatic patients without previous events of bleeding or thrombosis nor cardiovascular risk factors are considered “low risk” of complications and should not receive any treatment. In the history of cardiovascular disease or risk factors, patients are considered at “intermediate risk,” and anti-aggregants or cytoreductive therapy should be prescribed. Patients with a positive history of thrombosis are at “high risk” of thrombotic complications and should receive cytoreductive and anti-aggregant treatment [7].

Cytoreductive therapy includes medical treatment based on hydroxycarbamide or hydroxyurea (HU), anagrelide, and the more aggressive plateletpheresis. Anagrelide targets megakaryocytes inhibiting its maturation and subsequent formation of platelets, reducing its count to less than 500,000/mm3 with minimal toxicity and no known leukemogenic potential [18]. Anagrelide could be associated with HU (a DNA replication inhibitor) in high-risk cases. Nonetheless, the need for treatment should be periodically re-evaluated [7].

Therapeutic plateletpheresis has been utilized to prevent recurrent complications or treat acute thromboembolism or hemorrhage in selected patients with uncontrolled thrombocytosis, although not as a long-term treatment. Plateletpheresis is effective as it can rapidly reduce platelet count, previously reported in the perioperative management of surgical patients, as in uncontrolled post-splenectomy reactive thrombocytosis [19].

There is a significant association between treatment with alkylating agents and an increased risk of developing second hematological malignancies [10]. Still, treatment with HU, anagrelide, or other physiopathology disorders has not been associated [11]. Colorectal cancer is rarely associated with this disease; still, 3 of 7 ET patients reported undergoing abdominal surgery have been associated with colorectal cancer [15].

The management of colorectal patients with ET diagnosis should be specially considered due to chemotherapy side effects such as bone marrow, transient thrombocytopenia, or increased thrombotic risk from the malignancy itself and increased risk of disorders of coagulation function from the ET [7]. Surveillance is indicated in patients taking anagrelide when chemotherapy-induced bone marrow suppression is suspected [14].

Postoperative bleeding is a major complication in the context of ET-associated diagnosis. Colorectal surgery complications are associated with increased morbidity, prolonged intensive care and hospital stay, and mortality [13]. Along with careful hemostasis, intraoperative use of hemostatic agents has demonstrated a benefit in preventing the formation of hematomas and diminishing the risk of postoperative bleeding and developing seromas in non-emergency procedures [20].

Postoperative complications must be suspected in the presence of clinical parameters like pain, ileus, fever, tachycardia, hypotension, oliguria, and hypoxemia. Hemodynamic stability is the primary clinical sign, and it should be closely monitored. If the patients present hypovolemic shock (grade III or IV), surgical exploration is indicated to find and treat the source of bleeding. Conservative or non-surgical management is only advised under hemodynamic stability, access to diagnostic/therapeutic image studies, and prompt access to OR in conservative treatment failure or instability [21].

4. Conclusion

Multidisciplinary work is advised for best surgical outcomes and quality of care. The primary lessons we can learn from managing perioperative complications in hematologic diseases is that surgeon experience, enrollment of other clinical specialties, interventional radiology availability, ICU care, and endoscopy access can ensure good resolution. Regarding ET patients, further investigation is needed to prevent perioperative bleeding or thrombotic events and ensure compliance with perioperative management recommendations made by the hematologists and oncologists for optimal surgical care.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Sources of funding

None declared.

Ethics approval

Not required.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Cristopher Varela: conceptualization, data curation, writing – original draft.

Manar Nassr: conceptualization, writing – review & editing.

Azharuddin Razak: writing – review & editing.

Nam Kyu Kim: conceptualization, data curation, writing– original draft.

Research registration

Not applicable. This is not a ‘first man’ study.

Guarantor

Nam Kyu Kim, MD, FACS, FASCRS (Hon.).

Department of Surgery, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Severance Hospital, 50 Yonsei-ro, Seodaemun-Ku, 120-752, Seoul, South Korea.

011 (82) 2361-5562.

Declaration of competing interest

None to declare.

References

- 1.Singal D., Prasad A.S., Halton D.M., Bishop C. Essential thrombocythemia: a clonal disorder of hematopoietic stem cell. Am. J. Hematol. 1983;14:193–196. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830140212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hehlmann R., Jahn M., Baumann B., Kopcke W. Essential thrombocythemia: clinical characteristics and course of 61 cases. Cancer. 1988;61:2487–2496. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880615)61:12<2487::aid-cncr2820611217>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.for the SCARE Group. Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dindo D., Demartines N., Clavien P.A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004 Aug;240(2):205. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiser M.R. AJCC 8th edition: colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018 Jun;25(6):1454–1455. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6462-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines: Colon Cancer.

- 7.Radaelli F., Colombi M., Calori R., Zilioli V.R., Bramanti S., Iurlo A. Analysis of risk factors predicting thrombotic and/or haemorrhagic complications in 306 patients with essential thrombocythemia. Hematol. Oncol. 2007 Sep;25(3):115–120. doi: 10.1002/hon.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenaux P., Simon M., Caulier M.T., Lai J.L., Goudemand J., Bauters F. Clinical course of essential thrombocythemia in 147 cases. Cancer. 1990;66:549–556. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900801)66:3<549::aid-cncr2820660324>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefanini M. Basic mechanisms of hemostasis. Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 1954;30:239–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruggeri M., Rodeghiero F., Tosetto A., Castaman G., Scognamiglio F., Finazzi G. Postsurgery outcomes in patients with polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: a retrospective survey. Blood. 2008 Jan 15;111(2):666–671. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102665. The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radaelli F., Onida F., Rossi F.G., Zilioli V.R., Colombi M., Usardi P. Second malignancies in essential thrombocythemia (ET): a retrospective analysis of 331 patients with long-term follow-up from a single institution. Hematology. 2008 Aug 1;13(4):195–202. doi: 10.1179/102453308X316022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wada Y., Ryo J., Sarumaru S., Matsushita T., Isobe H., Sato B. Surgery for cholecystocholedocholithiasis in a patient with asymptomatic essential thrombocythemia: report of a case. Surg. Today. 1998;28(10):1073–1077. doi: 10.1007/BF02483965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai X.Y., Zhou W., Hong D.F., Cai X.J. A latent form of essential thrombocythemia presenting as portal cavernoma. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2009 Nov 14;15(42):5368. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amarapurkar P.D., Parekh S.J., Sundeep P., Amarapurkar D.N. Budd-chiari syndrome following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2013 Sep 1;3(3):256–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu Y., Jiang H., Chen Z., Lu B., Wu J. Abdominal surgery in patients with essential thrombocythemia: a case report and systematic literature review. Medicine. 2017 Nov;96(47) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiyoshi M., Nozawa H., Inada K., Koseki T., Nasu K., Seyama Y. Cecal cancer with essential thrombocythemia treated by laparoscopic ileocecal resection: a case report. Surg. Sase Rep. 2019 Dec;5(1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s40792-019-0660-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosoda K., Shimizu A., Kubota K., Notake T., Sugenoya S., Yasukawa K. A focal extramedullary hematopoiesis of the spleen in a patient with essential thrombocythemia presenting with a complicated postoperative course: a case report. Surg. Case Rep. 2021 Dec;7(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s40792-021-01119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverstein M.N., Petitt R.M., Solberg L.A., Jr., Fleming J.S., Knight R.C., Schacter L.P. Anagrelide: a new drug for treating thrombocytosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;318:1292–1294. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198805193182002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das S.S., Bose S., Chatterjee S. Thrombocytapheresis: managing essential thrombocythemia in a surgical patient. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011;92(1):e5–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards S.J., Crawford F., van Velthoven M.H., Berardi A., Osei-Assibey G., Bacelar M., Salih F., Wakefield V. The use of fibrin sealant during non-emergency surgery: a systematic review of the evidence of benefits and harms. Health Technol. Assess. 2017 doi: 10.3310/hta20940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuesta M., Bonjer H. Springer London; 2014. Treatment of Postoperative Complications After Digestive Surgery. [Google Scholar]