Significance

RNA synthesis by cellular RNA polymerases depends on an active-site component called the trigger loop that oscillates between an unstructured loop that admits NTP substrates and a helical hairpin that positions the NTP in every round of nucleotide addition. In most bacteria, the trigger loop contains a large, surface-exposed insertion module that occupies different positions in different transcription complexes but whose function during active transcription is unknown. By developing and using a disulfide reporter system, we find the insertion module must also alternate between in and out positions for every nucleotide addition, must swivel to a paused position to support regulation, and in enterobacteria, evolved a “Phe pocket” that captures a key phenylalanine in the out and swivel positions.

Keywords: RNA polymerase, transcription, pausing, catalysis, regulation

Abstract

The catalytic trigger loop (TL) in RNA polymerase (RNAP) alternates between unstructured and helical hairpin conformations to admit and then contact the NTP substrate during transcription. In many bacterial lineages, the TL is interrupted by insertions of two to five surface-exposed, sandwich-barrel hybrid motifs (SBHMs) of poorly understood function. The 188-amino acid, two-SBHM insertion in Escherichia coli RNAP, called SI3, occupies different locations in elongating, NTP-bound, and paused transcription complexes, but its dynamics during active transcription and pausing are undefined. Here, we report the design, optimization, and use of a Cys-triplet reporter to measure the positional bias of SI3 in different transcription complexes and to determine the effect of restricting SI3 movement on nucleotide addition and pausing. We describe the use of H2O2 as a superior oxidant for RNAP disulfide reporters. NTP binding biases SI3 toward the closed conformation, whereas transcriptional pausing biases SI3 toward a swiveled position that inhibits TL folding. We find that SI3 must change location in every round of nucleotide addition and that restricting its movements inhibits both transcript elongation and pausing. These dynamics are modulated by a crucial Phe pocket formed by the junction of the two SBHM domains. This SI3 Phe pocket captures a Phe residue in the RNAP jaw when the TL unfolds, explaining the similar phenotypes of alterations in the jaw and SI3. Our findings establish that SI3 functions by modulating TL folding to aid transcriptional regulation and to reset secondary channel trafficking in every round of nucleotide addition.

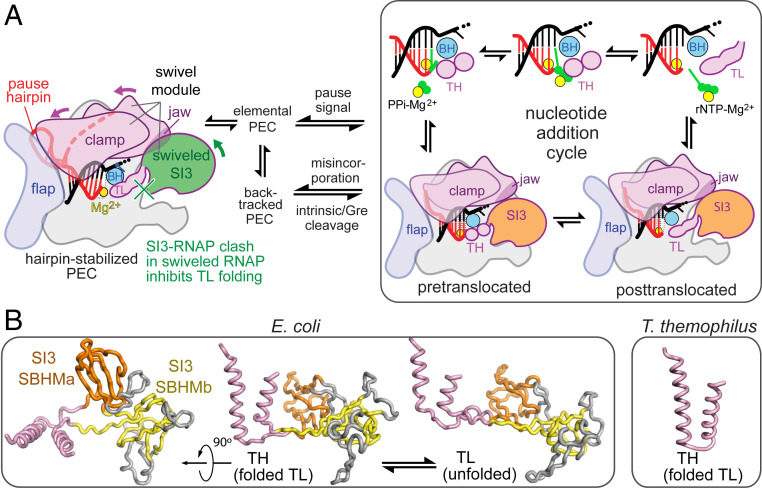

Gene expression in all cellular life forms is accomplished by a conserved, multisubunit RNA polymerase (RNAP) via a highly regulated nucleotide addition cycle (NAC; Fig. 1) that extends RNA transcripts by reaction with DNA-templated nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs). A posttranslocated RNAP first samples NTPs until the correct NTP binds in its active site. A flexible trigger loop (TL) then folds into a helical hairpin called the trigger helices (THs) that forms a three-helix bundle with the bridge helix (BH) and is stabilized by contacts to the complementary NTP–DNA pair, causing active-site closure (1–4). The closed active site accelerates by ≥104 SN2 displacement of pyrophosphate from the NTP by RNA 3′-hydroxyl-group attack on the α-phosphate, resulting in extension of the RNA by one nucleotide (2, 5, 6). Pyrophosphate release, RNA–DNA translocation, and TH unfolding then reset the NAC to the posttranslocated state for the next round of NTP binding. In many bacterial lineages, TL–TH cycling occurs in every round of nucleotide addition despite the presence of a large insertion of two to five surface-exposed, sandwich-barrel hybrid motifs (SBHMs) (7–9). The 188-amino acid, two-SBHM insertion in Escherichia coli RNAP is called sequence insertion 3 (SI3) (10).

Fig. 1.

E. coli RNAP transcription cycle and SI3. (A) The E. coli EC alternates between pre- and posttranslocated states and between TL and TH states during the NAC (Right) but enters alternate conformations in response to pause signals in the DNA and RNA that can slow translocation and induce swiveling or backtracking. SI3 occupies different locations in these states and inhibits TH formation in the swiveled state due to steric clash. (B) SI3 in E. coli TL (pink) is composed of two SBHM domains (orange and yellow), which include several loops (gray) in addition to the core SBHM fold. Structures are from Protein Data Bank (PDB) 6rh3 (TH) and 6rin (TL) (24). The Thermus thermophilus TH (Right; PDB: 2o5j) (2), which lacks a TL sequence insertion, is shown for comparison.

Nucleotide addition is rapid (30 to 100 nt ⋅ s−1) at most DNA positions. However, the elongation complex (EC) is controlled in part by pause sequences that halt the EC for ≥1 s by converting it to a paused EC (PEC) (11–13). These transcriptional pauses aid regulation and RNA biogenesis in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes by enabling transcriptional attenuation, transcription–translation coupling, RNA folding, RNA splicing, termination, and antitermination (14–20). Different types of pauses involve distinct PEC conformations, some of which can interconvert (Fig. 1A). The elemental pause occurs at specific DNA sequences that inhibit DNA template base loading (i.e., DNA translocation) during the NAC (11). A modest conformational change called “swiveling” and base-pairing energetics may explain slow translocation in the elemental PEC (ePEC), which can occupy multiple states and may rearrange further into backtracked or hairpin-stabilized PECs [hsPECs (21–24)]. Backtracked PECs are prevalent in eukaryotes, also occur in prokaryotes, and can be triggered by nucleotide misincorporation (25–28). At a hairpin-stabilized pause (e.g., the well-studied his pause from the attenuation control region of the E. coli histidine biosynthetic operon) (16, 29), a nascent RNA hairpin formed 11 to 12 nucleotides (nt) from the RNA 3′ end remodels the PEC and stabilizes the swiveled conformation (22, 23). Swiveling involves a ∼4° rotation of a module composed of the clamp, dock, shelf, β′ C-terminal region, jaw, and SI3 (the swivel module). The swivel-module rotation distorts an SI3-complementary depression in the RNAP surface so that RNAP can no longer accommodate the folded TH position of SI3. Backtrack pauses also induce swiveling like that seen in the hisPEC (24).

SI3 connects to the apex of the TL–TH via two flexible linkers (7), contacts the β′ jaw in the TL conformation (5), and mediates hairpin-stabilized pausing in E. coli RNAP by inhibiting TL folding in the swiveled PEC conformation. SI3 and jaw deletions abrogate hairpin-stabilized pausing with no additional effect when combined (5, 30, 31). SI3 shifts to a different location when the TH form, disrupting the SI3–jaw interface (23, 24, 32, 33).

Several aspects of SI3 function remain unclear. Although the TL folds and unfolds in every round of the NAC as expected (34), it is unclear whether SI3 also fluctuates between open and closed locations during rapid transcription or only opens when the EC is paused. Second, it is unknown if SI3 swiveling is required for pausing or is just a consequence of other RNAP conformational changes responsible for pausing. Finally, the structural basis by which the jaw domain modulates SI3 movements is undefined.

To address these questions, we sought ways to exploit engineered disulfide cross-links both to measure and to test SI3 conformational changes. Previously used methods to form RNAP disulfides proved unable to generate a key SI3 disulfide efficiently, leading us to develop an approach based on H2O2 oxidation. The facile formation of stable disulfides with limited damage to RNAP using H2O2 followed by catalase allowed us to determine SI3 positional biases (SPBs) in different EC states and to analyze how SI3 locations affect transcription and pausing, including in mutant RNAPs that define a role for SI3–jaw interaction.

Results

Design and Optimization of an SI3 Positional Reporter: Advantages of H2O2 as a Thiol Oxidant.

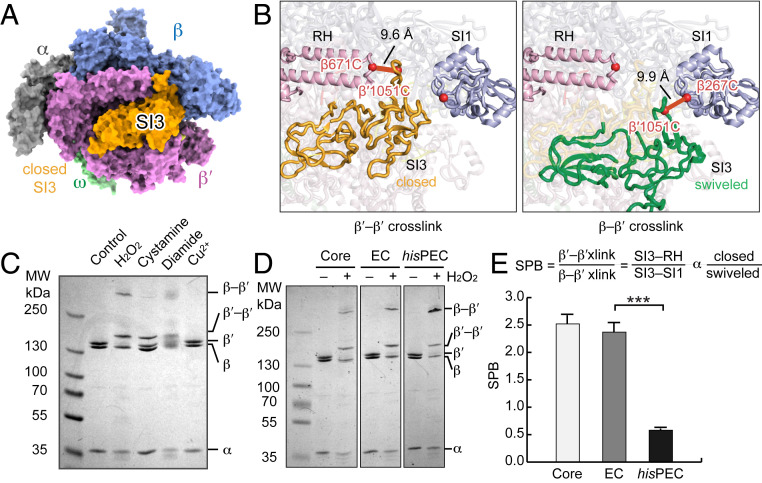

To design disulfide reporters of SI3 location, we examined SI3 residues that changed potential contacts in RNAP structures in which different SI3 positions have been resolved (closed SI3, TH form; open SI3, TL form; and swiveled SI3, hairpin-stabilized pause form; SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) (23, 32, 33). We first sought an SI3 residue that would make different contacts in the closed, open, and swiveled SI3 positions so that potential disulfides created by substitutions could report which location predominates in different EC states. Unfortunately, no SI3 residue exhibits this property. However, the closed and swiveled SI3 states could be distinguished by the location of residues in a β-ribbon–resembling loop in SI3-SBHM1 (β′1046 to 1061). This loop inserts between the rim helices (RHs) and sequence insertion 1 (SI1) such that β′D1051 approaches β′G671 in the closed state, whereas β′D1051 approaches a different part of SI1 (βR267) in the swiveled state. We predicted that Cys substituted for β′D1051 would compete for disulfide formation with Cys residues substituted for β′G671 and βR267 in the closed and swiveled states, respectively (Fig. 2 A and B).

Fig. 2.

Alternative SI3 locations and detection by a CTR. (A) RNAP in TH conformation with SI3 in closed position (Protein Data Bank [PDB]: 4yln; σ70 not shown) (33). (B) Cα–Cα distances of residues changed to Cys to generate the CTR (red spheres): β′SI3–β′RH (closed, orange, PDB: 4yln) and β′SI3–βSI1 (swiveled, green, PDB: 6asx) (32, 33). (C) Comparison of ability of different oxidants to form CTR disulfides in an EC reconstituted using 2.5 µM RNAP with RNA, T-DNA, and NT-DNA at 2:3:4 ratio (SI Appendix, Expanded Materials and Methods). (D) Comparison of CTR disulfides formed in RNAP core enzyme, an EC, and a PEC (hisPEC). (E) SI3 positional bias (SPB) calculated from the ratio of the two cross-link species in core RNAP, the EC and the his hsPEC. Results are mean ± SD (n = 3). Unpaired Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001.

To test this prediction, we generated an RNAP bearing β′D1051C, β′G671C, and βR267C substitutions. We call this system in which disulfides that report two different conformations compete for formation a Cys-triplet reporter (CTR) (23, 35). Conveniently, the disulfides formed by the SI3 CTR are readily distinguishable because one is internal to the β′ subunit, altering its electrophoretic mobility, and the other links β′ to β, causing a much larger retardation of electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 2 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

To date, cystamine, diamide, or Cu2+ have been used as oxidants to form disulfide bonds in Cys-substituted RNAPs (5, 23, 35–38). However, these oxidants did not work well for the SI3 CTR (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B), and each has disadvantages for probing RNAP conformations. Disulfide formation requires activation of one Cys sulfur by conjugation to the oxidant followed by SN2 nucleophilic displacement of the activating group by the second Cys thiolate via a trigonal bipyramidal transition state (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). This mechanism can reduce overall cross-link efficiency in two ways (37, 39). First, although high concentrations of oxidant favor disulfide formation electrochemically, some oxidants (e.g., cystamine) also react with the activated intermediate causing accumulation of mixed disulfides in competition with formation of the desired disulfide. Second, steric clash of the conjugated activating group with the surrounding protein environment may inhibit formation of the trigonal bipyramidal geometry in the transition state required for disulfide formation. This latter issue is a particular problem in the complex structure of RNAP, where larger or less flexible activating groups often reduce cross-link efficiency. Finally, oxidants can also be disadvantageous because they attack other exposed Cys residues on RNAP and alter its properties (e.g., heavy metals like Cu2+ can bind and inactivate enzymes) (40). Such effects may explain why diamide causes smearing of subunit bands during polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, complicating quantitation of disulfide bond formation (Fig. 2C).

In search of better oxidants for disulfide probes of RNAP conformation, we tested hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Compared to cystamine or diamide, H2O2 generated SI3 disulfides with higher efficiency (>80%) and at relatively high rate (kobs = ∼1.5 min–1; SI Appendix, Fig. S2). H2O2-induced cross-links also form in two steps (41). A cysteine thiolate reacts with H2O2 to form a sulfenic acid (CSOH) followed by displacement of OH– by a second cysteine thiolate. However, disulfides can also form by conjugation of two sulfenic acids via a thiosulfinate (41), which coupled with minimal steric constraints on the transition state may explain why H2O2 produces disulfide cross-links with higher efficiency.

The higher efficiency of H2O2-induced disulfide formation allowed us to create an SI3 CTR in which β′C671 in the RH and βC267 in SI1 compete to form disulfides with β′C1051 in SI3, thus reporting the occupancy ratio of the closed versus swiveled SI3 conformations (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E). In contrast, cystamine was unable to generate the β′C1051 to βC267 at useful levels irrespective of RNAP conformation (Fig. 2C).

H2O2 offers an additional advantage over other oxidants. It can be rapidly eliminated from a solution by addition of catalase, which converts H2O2 to H2O and O2 with a maximal turnover number of 16,000,000 to 44,000,000 s−1 (42). Thus, catalase treatment minimizes oxidative damage to the RNAP once disulfides are formed, allowing in vitro transcription or other assays of cross-linked RNAP in the absence of undesired effects of the added oxidant. Catalase treatment also generated clearer bands in denaturing polyacrylamide gels for cross-link quantitation (compare to diamide or H2O2 without catalase; Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). Finally, H2O2 treatment had minimal effects on RNAP activity (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). We conclude that H2O2 is a superior oxidant for disulfide probing of RNAP conformations.

SI3 Samples Multiple Locations in Transcription Complexes.

Using the optimized CTR system, we found that both cross-link species (SI3–RH and SI3–SI1) form in an EC, a paused complex (hisPEC), and core RNAP (Fig. 2 D and E). This result indicates that SI3 samples multiple locations by thermal fluctuation including the closed and swiveled states even in the absence of pause signals or bound NTP substrate. Differences in the ratio of SI3–RH to SI3–SI1 cross-links should be proportional to changes in the relative occupancies of these states in different transcription complexes (i.e., proportional to differences in ∆G° of the states in different transcription complexes). This view of RNAP as a dynamic system sampling diverse conformational states with different probabilities is consistent with both molecular dynamics simulations (43) and with the typically lower resolution observed in cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) analyses of RNAP complexes compared to those achievable in globular enzymes (23, 24, 32, 35).

Before using the SI3 CTR to study RNAP, we considered two questions. First, does the formation of both cross-link species by the CTR RNAP reflect noninterconverting conformations of SI3 in separate populations on RNAP? Using RNAPs containing only two Cys substitutions so that only one or the other disulfide could form (i.e., either the SI3–RH or SI3–SI1 disulfide in RNAPs called Cys-pair reporters, CPRs) (37), we found that SI3 conformations are in dynamic equilibrium. Fluctuations in SI3 position allowed each CPR disulfide to form at high efficiency absent conformation with the alternative disulfide (>80%; SI Appendix, Fig. S2E), which would not be possible if the conformations did not interconvert. Thus, SI3 readily samples the closed or swiveled conformation even in the absence of an NTP substrate or a pause signal.

Second, how is the ratio of SI3–SI1/SI3–RH disulfides in the CTR RNAP related to the ratio of the corresponding SI3 conformations? Although we cannot determine this relationship without an independent measure of the SI3 conformational distributions, it is unlikely that the SI3–RH/SI3–SI1 disulfide ratio and the closed/swiveled conformation ratio are identical. The rate at which each cross-link forms in the CTR RNAP will be a function not only of the ratio of the SI3 conformations but also of the chemical environment around the Cys residues and the probability that the sidechains can achieve the transition state sterically. These environmental effects are unlikely to be identical for the competing disulfides. Nonetheless, because the SI3 states are dynamically interconverting, a change in the SI3–RH/SI3–SI1 disulfide ratio will be proportional to changes in the bias of the SI3 positional equilibrium for a given RNAP or EC state regardless of the relative intrinsic rates of conformer interconversion and cross-linking. We defined SPB as the ratio of the SI3–RH/SI3–SI1 disulfides, and a relative measure of closed/swiveled SI3 occupancy provided the intrinsic cross-linking rates of SI3 conformers are constant in the complexes studied (Fig. 2E). A higher SPB indicates that SI3 is more biased toward the closed position, and a lower SPB indicates SI3 is more biased toward the swiveled position.

Cognate NTP Binding Stabilizes SI3 Closed Conformation.

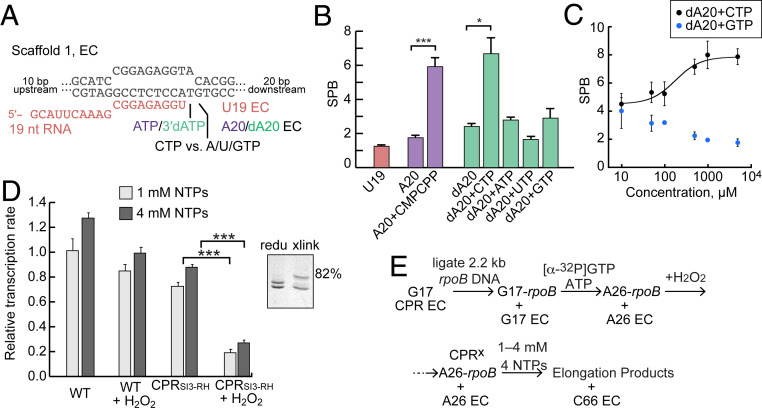

We first sought to explore how SI3 position changes upon substrate binding. Structural studies suggest that SI3 favors the closed position when cognate NTP is bound by an EC (24, 33), conditions known to stabilize TH formation to promote catalysis (23, 32, 33, 44). However, the positional bias of SI3 upon binding of cognate or noncognate NTPs in physiologic conditions where SI3 is dynamic remains untested. To ask how NTP binding affects SI3 location, we used SI3-CTR RNAP and an RNA–DNA scaffold to form an EC that allowed NTP binding but not nucleotide addition. This scaffold contained complementary 50mer DNA strands and a 19-nt RNA that was reacted with ATP to form A20 ECs or reacted with 3′dATP to form dA20 ECs (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Upon oxidation, A20 EC gave an SPB of 1.8 ± 0.1, similar to U19 (1.2 ± 0.1), but the SPB shifted to 5.9 ± 0.5 upon addition of the unreactive CTP analog CMPCPP (Fig. 3B). This shift in SBP indicates that SI3 increases occupancy of the closed position by a factor of ∼3.3 upon cognate NTP binding. Similarly, when CTP was added to dA20 EC, which lacked the 3′ OH required for SN2 attack during nucleotide incorporation, SPB shifted from 2.4 ± 0.2 to 6.7 ± 0.9, an increase of ∼2.8× . The slightly higher SPB of dA20 EC versus A20 EC is consistent with prior observations that a 3′ deoxy substitution favors the pretranslocated register, which favors TL folding (45).

Fig. 3.

SI3 is biased toward the closed position by cognate but not noncognate NTPs and inhibits transcript elongation when cross-linked in the closed position. (A) RNA–DNA scaffold used to reconstitute ECs (2:3:4 ratio of RNA, template-strand DNA, and nontemplate-strand DNA to 2.5 µM RNAP; SI Appendix, Expanded Materials and Methods). Either ATP or 3′-dATP can be incorporated at position 20 (see also SI Appendix, Fig. S4). 3′dA20 EC supports NTP binding but not nucleotide addition. (B) SPB of A20 EC, 3′dA20 EC, and ECs incubated with different NTPs (at 100 µM each NTP). (C) SPB of 3′dA20 EC incubated with different concentrations of cognate CTP or noncognate GTP. The experiments shown in B and C were performed on different days, accounting for the variations in SPB. Although the effect is modest, GTP ≥ 500 µM reduces SPB by ∼1. (D) Average elongation rates (relative to WT RNAP in reducing condition) at 1 mM each NTP or 4 mM each NTP. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Unpaired Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001. Inset: a typical assay of cross-link efficiency (82% of CPRSI3-RH was cross-linked by 5 mM H2O2). (E) Schematic of ligated scaffold transcription assay. The ligation reaction is incomplete, but only products longer than C66 are used to estimate elongation rate (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

We next asked how cognate versus noncognate NTP would affect SI3 positional bias. At 100 µM, noncognate ATP and GTP marginally increased dA20 SBP whereas UTP decreased SPB, possibly because rU–dG base pairing disfavors TL folding (Fig. 3B). Similarly, at higher concentration (5 mM), noncognate GTP decreased SPB to 1.8 ± 0.3 whereas cognate CTP raised SPB from 4.5 ± 0.5 at 10 µM to 7.9 ± 0.6 at 5 mM (Fig. 3C). These opposite effects are consistent with a preinsertion model for NTP selection in which NTP binding is indiscriminate and substrate discrimination arises principally from the ability of a complementary rNTP–dNMP base pairing to support TL folding (3, 46). The decrease in SPB caused by GTP suggests that either non–Watson–Crick base pairing or NTP binding in the E site may decrease occupancy of the TH state due of steric clash with TL sidechains. Taken together, these results suggest that cognate NTPs shift SI3 positional bias toward the closed position, likely in concert with TL folding, whereas noncognate NTPs may shift SI3 away from the closed positions, likely linked to decreased TH formation. Thus, the energetics of SI3 positioning may aid in NTP discrimination by modulating TL folding, which directly affects NTP discrimination (47–49), although effects of SI3 on NTP selectivity remain to be investigated in detail.

Nucleotide Addition Cycling Requires SI3 Open–Close Cycling.

A key question is whether SI3 moves back and forth between the closed and open position in every round of the NAC. Although the TL clearly undergoes folding unfolding cycles in each round of nucleotide addition (34) and blocking TH unfolding by disulfide cross-linking inhibits rapid transcription (37), it is unknown if SI3 also moves in every round of the NAC or might only shift to the open or swiveled state when an EC pauses. To determine whether SI3 movement is required for rapid nucleotide addition, we asked how biasing SI3 to the closed position with a disulfide would affect transcription rate during multiround nucleotide addition. For this purpose, we used a previously described ligated scaffold transcription assay that enables transcription by reconstituted ECs over multikb of DNA (50). We ligated a 2.2 kb DNA from the E. coli rpoB gene to reconstituted CPRSI3–RH ECs and then measured transcript elongation at 1 mM each of all four NTPs with and without the SI3–RH disulfide (Fig. 3 D and E). Biasing SI3 to the closed position with the disulfide allowed transcript elongation but at an average rate that was slower by a factor of ≥3.7 compared to the noncross-linked EC (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Pausing by the SI3–cross-linked RNAP was enhanced at some locations (e.g., at G31, 5 nt downstream of A26) and only a few ECs were able to extend past the point of ligation (+66; SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). The inhibition of multiround transcript elongation when SI3 is cross-linked in the closed position is unlikely due to reduced affinity of ECs for substrate NTP, since increasing Mg2+·NTP concentrations fourfold to 4 mM each had little effect on transcription rate (Fig. 3D).

These results indicate that SI3 must ordinarily alternate between the closed and open positions in each round of nucleotide addition rather than remaining closed while accommodating TL–TH cycling (note that biasing SI3 open is even more inhibitory as expected based on a TH-containing EC structure; see the section SI3 Swiveling Contributes to the Hairpin-Stabilized Pause and see Fig. 5). Biasing SI3 to the closed position likely influences transcription in multiple ways. First, it should favor TH formation, which narrows the RNAP secondary channel and should restrict NTP access to the active site. Second, the closed SI3–TH may stabilize the pretranslocated state during the NAC, which could slow transcription by inhibiting translocation as observed for a TH-stabilizing cross-link (37). Third, the closed SI3–TH appeared to strengthen sequence-specific pausing at certain sites (e.g., the pause sites evident in SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). The SI3–RH cross-link must allow some extent of TH–TL interconversion, however, since it decreased transcription rate by less than a factor of 10, whereas deletion of the TL inhibits transcription rate by ≥104, and stabilization of the TH with amino acid substitutions inhibits transcription rate by factors of ∼10 to 200 (2, 5, 6, 44). We conclude that alternation of SI3 between open and closed locations likely occurs in every round of nucleotide addition and that inhibition of these oscillations explains the effect of the SI3–RH disulfide.

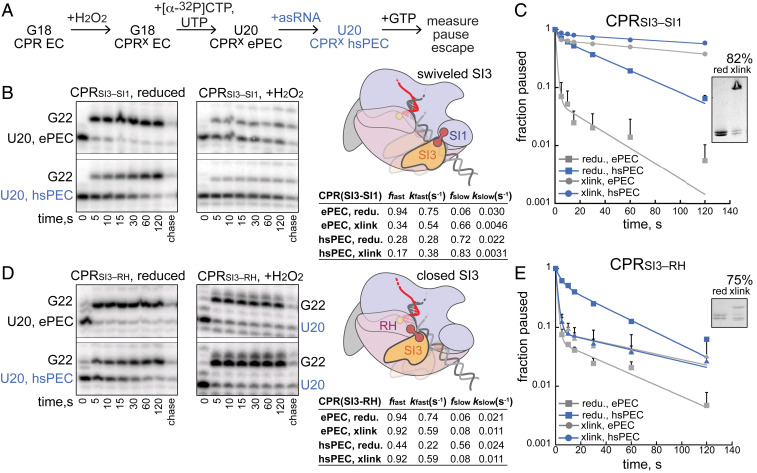

Fig. 5.

Biasing SI3 to swiveled or closed positions with disulfides establishes that SI3 swiveling is sufficient and necessary for hairpin-stabilized pausing. (A) Reaction schematic to test effects of SI3 disulfides on pausing. ECs were reconstituted using 3 µM RNAP with RNA, T-DNA, and NT-DNA 0.33:0.67:1.67 ratio; SI Appendix, Expanded Materials and Methods). (B and D) RNAs formed during pause assays, schematics of SI3 disulfides tested, and pause kinetics. ffast and fslow are the fractions of pauses in faster and slower states when fit to a two-exponential equation and kfast and kslow are the corresponding rate constants. A complete set of kinetic fitting parameters with errors is in SI Appendix, Table S2. (C and E) Fraction pause RNAs as a function of time under different conditions.

SI3 Location Bias Shifts in PECs.

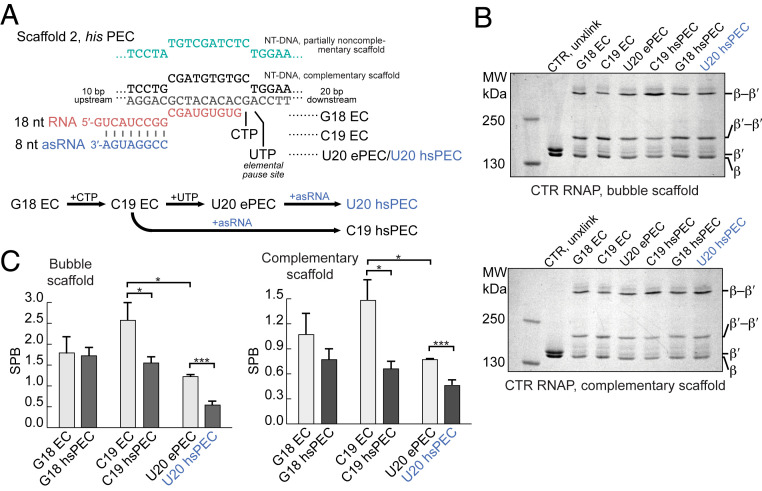

We next examined the effect of RNAP pausing on the location bias of SI3 using the well-characterized PECs that form at U102 in the attenuation-controlled leader region of the E. coli his biosynthetic leader region (hisPECs) (22, 23, 29). RNAP forms either ePECs in the absence of a nascent RNA pause hairpin or hsPECs when a nascent RNA structure forms in the RNA exit channel 11 nt from the RNA 3′ end. We examined ECs (G18), ePECs (U20), and hsPECs (C19 and U20) reconstituted with CTR RNAP on the same scaffold using an antisense RNA (asRNA) to form the pause hairpin, limited nucleotide addition to advance G18 ECs to C19 (with CTP) and U20 (with CTP and UTP), and either a complementary or partially noncomplementary NT DNA strand (Fig. 4A). We observed higher SPBs on the partially noncomplementary ECs and PECs but the same overall trends in SI3 positional bias (Fig. 4 B and C). The higher SPBs on partially noncomplementary complexes may reflect lesser thermal fluctuations of SI3 when translocation is constrained by the noncomplementary bubble, allowing greater formation of the closed SI3 cross-link. In both types of complexes, however, the ePEC exhibited a modest shift toward the swiveled conformation relative to G18 and C19 ECs, whereas the hsPEC increased the bias toward the swiveled conformation more dramatically (Fig. 4 B and C).

Fig. 4.

SI3 becomes biased to the swiveled position as RNAP in the his ePEC and hsPEC. (A) RNA–DNA scaffold used to reconstitute his PECs (2:3:4 ratio of RNA, T-DNA, and NT-DNA to 2.5 µM RNAP; SI Appendix, Expanded Materials and Methods). G18 EC reacts with CTP and UTP to form C19 EC and U20 ePEC, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Addition of an asRNA mimics formation of the his pause hairpin and forms the his hsPEC. (B) SDS-PAGE images of CTR cross-links formed on complementary and partially noncomplementary scaffolds of his ECs and PECs. (C) SPB of his ECs and PECs. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Unpaired Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05.

These changes in SI3 positional bias for the his elemental and hairpin-stabilized pauses confirm that SI3 swiveling imaged by cryo-EM of PECs reflects changes in the dynamics of SI3 in physiological conditions and that the extent of swiveling correlates with pause duration since SI3 in the his ePEC is less biased toward the swiveled state than in the longer-lived his hsPEC. Hairpin promotion of swiveling is evident at C19 in addition to U20, consistent with prior observations of that the his pause hairpin can form in the pause –1 complex (51, 52); this result also supports the conclusion that exit channel RNA duplexes directly promote SI3 swiveling. A shift in SI3 toward the closed conformation in C19 ECs relative to G18 ECs also was evident (Fig. 4 B and C), consistent with prior observations that 3′ C favors the pretranslocated state, 3′ G favors the posttranslocated state, and a pretranslocated EC stabilizes the TH versus TL conformation (45, 53).

SI3 Swiveling Contributes to the Hairpin-Stabilized Pause.

Although both cryo-EM and our CTR data support a causal role for SI3 swiveling in pausing, a direct experimental test by preventing or promoting swiveling is needed to establish causality. To perform this test, we next used CPRSI3–SI1 and CPRSI3–RH RNAPs to probe the effects on his pausing of strongly biasing SI3 to the swiveled or closed conformation, respectively. The SI3–SI1 swiveled cross-link was formed at G18 with high efficiency (∼82%) prior to C19 radiolabeling and U20 extension (Fig. 5A). Addition of GTP to the cross-linked PECs enabled measurement of the pause escape rate. Without cross-linking, the majority of the ePEC (94 ± 2%) rapidly escaped the weak elemental pause (kePEC, red = 0.75 s−1), whereas the majority of the hsPEC (72 ± 2%) generated after asRNA addition escaped the hairpin-stabilized pause, a rate 34 times slower (khsPEC, red = 0.022 s−1; Fig. 5 B and C). When CPRSI3–SI1 RNAP was cross-linked to favor the swiveled SI3 conformation, the elemental pause escape rate was significantly slowed by a factor of >170 (kePECx = 0.0046 s−1), even slower than that of the uncross-linked hsPEC. Addition of asRNA to the SI3–SI1–cross-linked U20 EC further decreased the pause escape rate by a factor of only ∼1.5 compared to the 34-fold effect the uncross-linked EC (khsPECx = 0.0031 s−1). These results indicate that artificially biasing SI3 toward the swiveled position greatly increases pause dwell time even in the absence of an exit channel RNA duplex. Nearly all the effect of the pause hairpin was recapitulated by the swivel-biasing cross-link, suggesting that practically all the effect of hairpin is mediated by stabilizing the swiveled SI3 conformation. We conclude that biasing SI3 to the swiveled position strongly inhibits TL folding, thus obviating the swivel-inducing effect the exit channel RNA duplex created by asRNA addition.

To test the opposite prediction that inhibiting SI3 swiveling with the SI3–RH cross-link should also obviate the effect of an exit channel RNA duplex, we measured pause kinetics for the his PEC formed with CPRSI3–RH RNAP with and without addition of the asRNA. As predicted for the hsPEC, formation of the SI3–RH cross-link to favor the SI3 closed position greatly reduced pausing and essentially eliminated the effect of the exit channel duplex (compare pausing profiles for the cross-linked ePEC and hsPEC, Fig. 5 D and E). Biasing SI3 toward the closed conformation either prevented the exit channel duplex from inducing swiveling or prevented the duplex from forming (e.g., if swiveling is required to accommodate the duplex in the exit channel). These results support the view that induction of SI3 swiveling and consequent inhibition of TL folding is the mechanism by which exit channel RNA duplexes increase pause dwell time.

In contrast for the his ePEC, formation of the SI3–RH cross-link to favor the SI3 closed position modestly increased pausing, contrary to the expectation that swiveling aids elemental pausing (Fig. 5 D and E). However, this increase in pausing is consistent with stimulation of pausing at some sites observed when cross-linked CPRSI3–RH RNAP transcribed over a long DNA template (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). We conjecture that stabilizing SI3 in the closed conformation may stabilize the pretranslocated register of the ePEC and could increase pausing at sites where the translocation is naturally slow.

To summarize, the pausing behavior of PECs with SI3 biased toward either the closed or swiveled position strongly supports the view that swiveling stabilized by an exit channel duplex or simply in response to RNA and DNA sequences is a direct cause of transcriptional pausing, likely by inhibiting the transition from the half-translocated (RNA only) to fully translocated state in the NAC. Stabilization of the TH by biasing SI3 toward the closed state also appears capable of stimulating pausing.

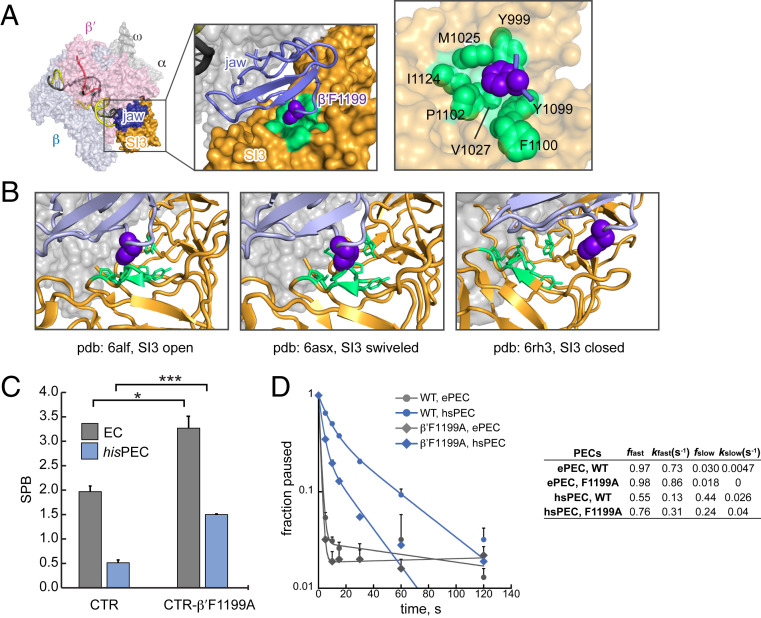

An SI3 Phe Pocket Captures the RNAP Jaw to Tune TL Folding, Pausing, and Catalysis.

Previous biochemical studies suggest that the β′ jaw domain participates in pausing via interdependent effects with SI3 (5, 30, 31), but the basis of jaw–SI3 interaction has not been defined. We examined the SI3–jaw interface in cryo-EM structures of ECs and the hisPEC (23, 24, 32) and observed a hydrophobic alcove on the SI3 surface (a Phe pocket) that appeared to accommodate the Phe sidechain of a jaw residue (β′F1199; Fig. 6A). However, when SI3 is in the closed position, this SI3–jaw interaction is disrupted, and F1199 no longer resides in the pocket (e.g., when NTP is bound by an EC; Fig. 6B) (24). To test whether the jaw F1199–SI3 Phe pocket interaction inhibits movement of SI3 to the closed position, we generated RNAPs bearing a β′F1199A substitution and used them for CTR and pausing assays. We found that SI3 became more biased toward the closed position in both ECs and hsPECs when F1199 was changed to Ala, indicating that the F1199–Phe pocket interaction stabilizes jaw–SI3 interaction and that its disruption decreases the thermodynamic stabilities of SI3 locations in which the interaction occurs (i.e., open and swiveled SI3; Fig. 6C). Pause assays using β′F1199A RNAP revealed a reduction in hairpin-stabilized pausing, consistent with the model that SI3 swiveling, stabilized by F1199–Phe pocket interaction, is required for hairpin-stabilized pause (Fig. 6D). β′F1199A also increased nucleotide misincorporation (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), as expected for an alteration that favors TH formation (47–49). These results suggest that the jaw provides a docking site for SI3 via a Phe pocket interaction that modulates SI3 movements during both the NAC and transcriptional pausing.

Fig. 6.

Capture of β′F1199 in the RNAP jaw by a Phe pocket in SI3 modulates SI3 movement. (A) Phe pocket interaction in SI3 open position (Protein Data Bank [PDB]: 6alf) (32). Light green, the hydrophobic pocket in SI3. Purple, β′F1199. (B) Phe pocket interaction and disruption in open (PDB: 6alf), swiveled (PDB: 6asx), and closed (PDB: 6rh3) ECs or PEC (23, 24, 32). (C) CTR assay of wild-type and β′F1199A RNAPs bound to EC and hisPEC scaffolds. Unpaired Student’s t test, ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05. (D) Pause RNA as a function of time after mixing with GTP in reducing conditions and derived pausing kinetic parameters for CTR RNAP and CTR-β′F1199A RNAP. β′F1199A decreased hairpin-stabilized pausing by a factor of ∼2.5. See Fig. 5 legend for kinetic parameter definitions.

Discussion

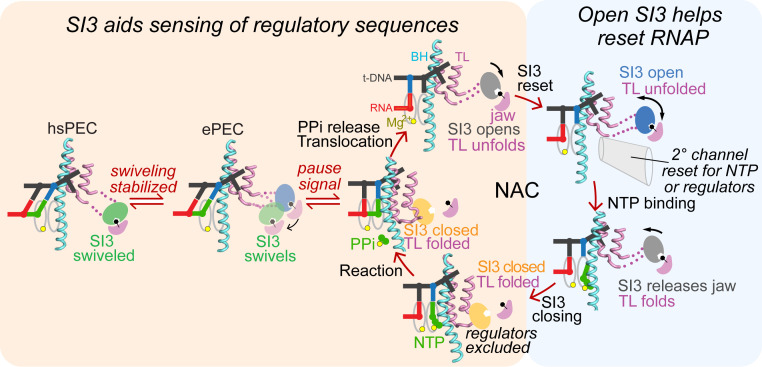

We report insights into the function of SI3, a modulator of RNAP catalytic function, by exploiting sulfhydryls that alternate proximity when SI3 in E. coli RNAP changes location and H2O2–catalase as a superior disulfide bond–formation system for disulfide reporters of RNAP conformation: 1) SI3 fluctuates among a range of locations from closed to swiveled in most ECs with a predominate location determined by interactions in the EC; 2) SI3 ordinarily cycles between preferentially closed and open positions in every round of nucleotide addition accompanying TL folding–unfolding; 3) SI3 swiveling is a direct cause of prolonged transcriptional pausing; and 4) the open and swiveled conformations of SI3 are stabilized by capture of a Phe residue in the RNAP jaw domain by a Phe pocket formed at the interface between the two SBHM domains in SI3. These findings have important implications for the function and evolution of SI3-like domains in bacterial RNAPs.

SI3 Positional Cycling Resets RNAP for Timely Regulation during Transcript Elongation.

Structural analyses capture SI3 in the open position or as disordered except when active site–bound NTP or a pretranslocated RNA 3′ nt stabilize SI3 in a closed position (24, 32, 33, 54) or when pausing favors a swiveled position (22–24). However, it has been unclear if SI3 actually cycles between closed and open locations in concert with TL folding and unfolding during rapid nucleotide addition. The location of the open SI3 on the jaw domain stabilized by the Phe pocket interaction appears structurally incompatible with TH formation because the linkers connecting SI3 to the TL are too short to accommodate the TH position without SI3 movement. However, the possibility that SI3 remains closed while allowing TL–TH cycling during rapid nucleotide addition and opens only at pause sites or in response to other regulatory events was structurally feasible but untested. Our findings contradict this view, since stabilizing the closed SI3 strongly inhibits rapid nucleotide addition (Fig. 3D). Instead, they support a view in which SI3 fluctuates among many possible locations including closed, open, and swiveled in most ECs, with strong biases favoring the closed state when substrate binding stabilizes TH formation, the open state after PPi release and translocation, and the swiveled state in PECs (Figs. 4 B and C and Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

SI3 states during RNA chain elongation and pausing aid transcription. In an active posttranslocated EC with an unfolded TL (NAC, Top Left), SI3 docks on the jaw domain, but thermal fluctuation enables SI3 to sample among different positions. In this state, the secondary channel (2° channel) is open and can admit NTPs or regulators. Binding of cognate NTP then stabilizes the folded TH with SI3 shifted in the closed position. In this location, SI3 will clear the secondary channel of regulators and, together with the TH, close the active site to catalyze nucleotide addition. After nucleotide addition, the EC either undergoes translocation with PPi release, TL unfolding, and SI3 movement back to the open position or undergoes a transition to the elemental paused state. In response to RNA–DNA sequences, the ePEC can either isomerize back to the elongation pathway (back to the NAC) or convert to either a backtracked PEC (not shown) or a hsPEC.

This picture of a fluctuating SI3 domain that cycles between predominately closed or open positions in concert with the NAC suggests that SI3 could play an important regulatory function by resetting the RNAP secondary channel and possibly the overall state of the EC in every round of nucleotide addition. Resetting the secondary channel may be important because multiple secondary channel–binding regulators compete to occupy the secondary channel when SI3 is in the open position, including GreA, GreB, TraR, Rnk, and DksA in E. coli and additional regulators in other bacteria (55). When SI3 shifts to the closed position, steric clash precludes secondary channel binding by these regulators (24) as evidenced by GreB and DksA competition with TH formation (37). NTPs also must enter the active site through the secondary channel but appear unable to pass through when the channel is occupied by a secondary channel–binding factor. By cycling between open and closed locations in every round of nucleotide addition, SI3 effectively resets the secondary channel to a naïve state when it moves from the closed position that excludes the regulators to the open position that allows both NTPs and regulators to compete for secondary channel occupancy. This resetting function of SI3 could aid efficient regulatory responses of the EC based on only its current state.

SI3 cycling also could contribute to resetting the entire EC in every round of nucleotide addition. A long-standing discussion has considered whether RNAP can occupy persistent conformational states over multiple rounds of nucleotide addition; such states might, for instance, be resistant to termination or possess altered catalytic properties independent of bound regulators (56, 57). Cycling of SI3 in every round of nucleotide addition suggests that SI3 alone does not cause persistent RNAP conformational states, although other models for long-lived RNAP conformations remain possible.

SI3 Augments the Regulatory Capacity of RNAP by Enhancing Transcriptional Pausing.

Our results establish that biasing SI3 location toward swiveling with a disulfide bond directly enhances transcriptional pausing, presumably by inhibiting TL folding, stabilizing the half-translocated state observed in the his ePEC and hsPEC, or both (Figs. 1 and 5). Intriguingly, we also observed that some pauses may be increased when SI3 is biased toward the closed conformation by a disulfide bond (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Possibly, this increased pausing by the closed CPR RNAP occurs at sites where PECs can be stabilized in the pretranslocated state. Strikingly, however, the closed CPR RNAP was unaffected by pause hairpin formation at the his pause site, both confirming the role of swiveling in pause hairpin action and showing that SI3 affects different classes of pause mechanisms in different ways. Although SI3 is crucial for hairpin stabilization of the his pause, further study is needed to understand hairpin-stabilized pauses in bacteria like firmicutes that lack SI3 (58).

These results suggest that an important function of SI3 could be to increase the potential for sequence-dependent regulation of transcript elongation by sensitizing RNAP to different modes of pausing. The presence in RNAP of a TL insertion able to assume different conformational states increases the conformational complexity of RNAP. Because SI3 is inserted directly into the TL, its conformation can affect catalysis. By virtue of being surface exposed, it is possible, although as yet undemonstrated, that solution conditions could affect SI3 conformational states. Thus, by fluctuating among various positions, SI3 may increase the ways that DNA and RNA sequence can bias RNAP to metastable pause sites stabilized in part by SI3 contacts or clashes in particular RNAP conformations. In this way, SI3 increases the regulatory capacity of RNAP to respond to signals in DNA and nascent RNA.

SI3-like Insertions Are Widespread, but the Phe Pocket Is Specific to γ-Proteobacteria.

Both resetting secondary channel trafficking and increasing regulatory capacity may explain in part how SI3, and TL insertions more generally, were acquired during evolution of bacterial RNAPs. However, several interesting questions about SI3 evolution remain unanswered. All known TL insertions consist of two or more repeats of SBHM domains (8, 9), but their distribution among bacterial lineages begs the question of whether some insertions in different lineages arose independently or if all TL insertions are evolutionarily related (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). TL insertions are present in most bacterial lineages but the lineages in which they are absent versus present do not cluster together (59), raising the possibility these insertions arose independently. Most notably, insertions (of five SBHM domains) are present in cyanobacteria even though they are absent in most evolutionarily nearby lineages. The SBHM fold is present elsewhere in the RNAP large subunits, including as a universally conserved feature called the flap or wall in bacterial and eukaryotic RNAPs, respectively (8). It is possible that unusual genetic rearrangements that arise over time in large, rapidly growing bacterial populations may have led to duplications of the SBHM fold and independent selection of these TL insertions in RNAP in different lineages.

Regardless of evolutionary history, another question is whether TL insertions are related to another feature of transcriptional regulation that differs in diverse bacteria. Although our understanding of the diversity of regulatory mechanisms in diverse bacteria remains primitive and in great need of expanded study, two distinct themes in bacterial regulation of transcript elongation have recently emerged. First, the universal elongation factor NusG displays markedly different effects in different lineages. NusG stimulates pausing in firmicutes and actinobacteria (based on Bacillus subtilis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis), whereas it suppresses pausing in proteobacteria (based on E. coli) (60–62). Second, transcription and translation are coupled in some bacterial lineages like E. coli but not coupled in others like B. subtilis, with related differences in the role of Rho-dependent termination in mRNA quality control (63). However, the distribution of TL insertions among bacterial lineages appears to be unrelated to the patterns of either NusG pause effect or transcription–translation coupling among different bacterial lineages (60, 63). Thus, selection for TL insertions appears to have operated independently of these other major themes in the bacterial regulation of transcript elongation.

One possibility is that a major selective pressure for generation or retention of TL insertions is simply to increase the evolvability of RNAP to adapt to diverse environments and stresses (64). In other words, the presence of a TL insertion increases the ways in which the regulatory responses of RNAP can be altered by mutation in response to different selective pressures. Even without mutation, a TL insertion may make RNAP easier to regulate by increasing the available conformations that impact catalysis. Especially in bacteria whose range of environmental niches and adaptive responses is huge, an ability to change regulatory responses simply by changing the properties and interactions of a TL insertion may be significant.

One line of evidence supporting selection for evolvability of TL insertions comes from our discovery of the role of the Phe pocket in modulating the function of SI3 in E. coli (Fig. 6). Although the sequences that comprise the Phe pocket and the jaw Phe residue itself are well conserved among γ-proteobacteria, these residues are not conserved in other bacterial lineages in which TL insertions are present (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Indeed, the jaw Phe residue is more commonly His in other TL insertion–bearing lineages. This observation suggests the crucial Phe pocket evolved to modulate SI3 function in γ-proteobacteria, whereas other interactions of TL insertions, as yet uncharacterized, may predominate in other lineages. Thus, our current findings highlight two important questions for future study: 1) what specific regulatory features are conferred on SI3 by the Phe pocket interaction and 2) to what extent do locations and interactions similar to those found for SI3 operate in other TL insertions versus lineage-specific evolution of TL-insertion locations and interactions?

Materials and Methods

Further details are provided in SI Appendix, Expanded Materials and Methods.

Reagents and Materials.

Plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1. The CTR, CPR, and RNAPs were purified as described previously (5, 12, 21) using expression plasmids derived from pRM756 with a His10-ppx tag at the C terminus of β′ or, for variants with substitutions in β, from pRM843 with a His10-ppx tag at the N terminus of β and a Strep tag at the C terminus of β′ subunit.

Disulfide Cross-linking Assays.

ECs and PECs were reconstituted and assayed for pausing and elongation as described previously (21) in the figure legends and in SI Appendix, Expanded Materials and Methods. To induce disulfide bond cross-linking, H2O2 was added to 10 µL CTR or CPR RNAPs or ECs at final concentrations of 5 mM H2O2 and 2 to 2.5 µM RNAP or EC, and the mixtures were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. To remove excess H2O2, 1 µL 2 U/µL catalase (bovine, Sigma-Aldrich) was then added and incubation was continued for 5 min at room temperature. The ligation–elongation assay using a 2.2-kb DNA (E. coli rpoB[216–2459]) with StyI-generated 5′ overhang (5′-CTTG) was performed as described previously (50).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Landick group for helpful discussions and Michael Engstrom and Michael Wolfe for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH Grant GM38660 (to R.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2101805118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Seibold S. A., et al., Conformational coupling, bridge helix dynamics and active site dehydration in catalysis by RNA polymerase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799, 575–587 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vassylyev D. G., et al., Structural basis for substrate loading in bacterial RNA polymerase. Nature 448, 163–168 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D., Bushnell D. A., Westover K. D., Kaplan C. D., Kornberg R. D., Structural basis of transcription: Role of the trigger loop in substrate specificity and catalysis. Cell 127, 941–954 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belogurov G. A., Artsimovitch I., The mechanisms of substrate selection, catalysis, and translocation by the elongating RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 3975–4006 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Windgassen T. A., et al., Trigger-helix folding pathway and SI3 mediate catalysis and hairpin-stabilized pausing by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 12707–12721 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J., Palangat M., Landick R., Role of the RNA polymerase trigger loop in catalysis and pausing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 99–104 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chlenov M., et al., Structure and function of lineage-specific sequence insertions in the bacterial RNA polymerase beta’ subunit. J. Mol. Biol. 353, 138–154 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iyer L. M., Koonin E. V., Aravind L., Evolutionary connection between the catalytic subunits of DNA-dependent RNA polymerases and eukaryotic RNA-dependent RNA polymerases and the origin of RNA polymerases. BMC Struct. Biol. 3, 1–23 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane W. J., Darst S. A., Molecular evolution of multisubunit RNA polymerases: Sequence analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 395, 671–685 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Artsimovitch I., Svetlov V., Murakami K. S., Landick R., Co-overexpression of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase subunits allows isolation and analysis of mutant enzymes lacking lineage-specific sequence insertions. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12344–12355 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landick R., The regulatory roles and mechanism of transcriptional pausing. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 1062–1066 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson M. H., et al., A pause sequence enriched at translation start sites drives transcription dynamics in vivo. Science 344, 1042–1047 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang J. Y., Mishanina T. V., Landick R., Darst S. A., Mechanisms of transcriptional pausing in bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 4007–4029 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonkers I., Lis J. T., Getting up to speed with transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 167–177 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer A., Landry H. M., Churchman L. S., Pause & go: From the discovery of RNA polymerase pausing to its functional implications. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 46, 72–80 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J., Landick R., A two-way street: Regulatory interplay between RNA polymerase and nascent RNA structure. Trends Biochem. Sci. 41, 293–310 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landick R., Carey J., Yanofsky C., Translation activates the paused transcription complex and restores transcription of the trp operon leader region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 4663–4667 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Proshkin S., Rahmouni A. R., Mironov A., Nudler E., Cooperation between translating ribosomes and RNA polymerase in transcription elongation. Science 328, 504–508 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gusarov I., Nudler E., The mechanism of intrinsic transcription termination. Mol. Cell 3, 495–504 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proudfoot N. J., Transcriptional termination in mammals: Stopping the RNA polymerase II juggernaut. Science 352, aad9926 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saba J., et al., The elemental mechanism of transcriptional pausing. eLife 8, 8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo X., et al., Structural basis for NusA stabilized transcriptional pausing. Mol. Cell 69, 816–827.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang J. Y., et al., RNA polymerase accommodates a pause RNA hairpin by global conformational rearrangements that prolong pausing. Mol. Cell 69, 802–815.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdelkareem M., et al., Structural basis of transcription: RNA polymerase backtracking and its reactivation. Mol. Cell 75, 298–309.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Artsimovitch I., Landick R., Pausing by bacterial RNA polymerase is mediated by mechanistically distinct classes of signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 7090–7095 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komissarova N., Kashlev M., Transcriptional arrest: Escherichia coli RNA polymerase translocates backward, leaving the 3′ end of the RNA intact and extruded. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 1755–1760 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerner E., et al., Backtracked and paused transcription initiation intermediate of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E6562–E6571 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nudler E., Mustaev A., Lukhtanov E., Goldfarb A., The RNA-DNA hybrid maintains the register of transcription by preventing backtracking of RNA polymerase. Cell 89, 33–41 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan C. L., Landick R., The Salmonella typhimurium his operon leader region contains an RNA hairpin-dependent transcription pause site. Mechanistic implications of the effect on pausing of altered RNA hairpins. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 20796–20804 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conrad T. M., et al., RNA polymerase mutants found through adaptive evolution reprogram Escherichia coli for optimal growth in minimal media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 20500–20505 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ederth J., Artsimovitch I., Isaksson L. A., Landick R., The downstream DNA jaw of bacterial RNA polymerase facilitates both transcriptional initiation and pausing. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37456–37463 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang J. Y., et al., Structural basis of transcription arrest by coliphage HK022 Nun in an Escherichia coli RNA polymerase elongation complex. eLife 6, e25478 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuo Y., Steitz T. A., Crystal structures of the E. coli transcription initiation complexes with a complete bubble. Mol. Cell 58, 534–540 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazumder A., Lin M., Kapanidis A. N., Ebright R. H., Closing and opening of the RNA polymerase trigger loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 15642–15649 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang J. Y., et al., Structural basis for transcript elongation control by NusG family universal regulators. Cell 173, 1650–1662 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellecourt M. J., Ray-Soni A., Harwig A., Mooney R. A., Landick R., RNA polymerase clamp movement aids dissociation from DNA but is not required for RNA release at intrinsic terminators. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 696–713 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nayak D., Voss M., Windgassen T., Mooney R. A., Landick R., Cys-pair reporters detect a constrained trigger loop in a paused RNA polymerase. Mol. Cell 50, 882–893 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sekine S., Murayama Y., Svetlov V., Nudler E., Yokoyama S., The ratcheted and ratchetable structural states of RNA polymerase underlie multiple transcriptional functions. Mol. Cell 57, 408–421 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiita A. P., Ainavarapu S. R., Huang H. H., Fernandez J. M., Force-dependent chemical kinetics of disulfide bond reduction observed with single-molecule techniques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7222–7227 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sterritt R. M., Lester J. N., Interactions of heavy metals with bacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 14, 5–17 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo D., Smith S. W., Anderson B. D., Kinetics and mechanism of the reaction of cysteine and hydrogen peroxide in aqueous solution. J. Pharm. Sci. 94, 304–316 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heck D. E., Shakarjian M., Kim H. D., Laskin J. D., Vetrano A. M., Mechanisms of oxidant generation by catalase. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1203, 120–125 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang B., Predeus A. V., Burton Z. F., Feig M., Energetic and structural details of the trigger-loop closing transition in RNA polymerase II. Biophys. J. 105, 767–775 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toulokhonov I., Zhang J., Palangat M., Landick R., A central role of the RNA polymerase trigger loop in active-site rearrangement during transcriptional pausing. Mol. Cell 27, 406–419 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malinen A. M., et al., Active site opening and closure control translocation of multisubunit RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 7442–7451 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westover K. D., Bushnell D. A., Kornberg R. D., Structural basis of transcription: Nucleotide selection by rotation in the RNA polymerase II active center. Cell 119, 481–489 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan C. D., Larsson K. M., Kornberg R. D., The RNA polymerase II trigger loop functions in substrate selection and is directly targeted by alpha-amanitin. Mol. Cell 30, 547–556 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kireeva M. L., et al., Transient reversal of RNA polymerase II active site closing controls fidelity of transcription elongation. Mol. Cell 30, 557–566 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larson M. H., et al., Trigger loop dynamics mediate the balance between the transcriptional fidelity and speed of RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 6555–6560 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mishanina T. V., Palo M. Z., Nayak D., Mooney R. A., Landick R., Trigger loop of RNA polymerase is a positional, not acid-base, catalyst for both transcription and proofreading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E5103–E5112 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan C. L., Wang D., Landick R., Multiple interactions stabilize a single paused transcription intermediate in which hairpin to 3′ end spacing distinguishes pause and termination pathways. J. Mol. Biol. 268, 54–68 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang D., et al., Discontinuous movements of DNA and RNA in RNA polymerase accompany formation of a paused transcription complex. Cell 81, 341–350 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hein P. P., Palangat M., Landick R., RNA transcript 3′-proximal sequence affects translocation bias of RNA polymerase. Biochemistry 50, 7002–7014 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu B., Zuo Y., Steitz T. A., Structures of E. coli σS-transcription initiation complexes provide new insights into polymerase mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 4051–4056 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gourse R. L., et al., Transcriptional responses to ppGpp and DksA. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 72, 163–184 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pasman Z., von Hippel P. H., Active Escherichia coli transcription elongation complexes are functionally homogeneous. J. Mol. Biol. 322, 505–519 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harrington K. J., Laughlin R. B., Liang S., Balanced branching in transcription termination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5019–5024 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yakhnin A. V., Babitzke P., Mechanism of NusG-stimulated pausing, hairpin-dependent pause site selection and intrinsic termination at overlapping pause and termination sites in the Bacillus subtilis trp leader. Mol. Microbiol. 76, 690–705 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khaledian E., Brayton K. A., Broschat S. L., A systematic approach to bacterial phylogeny using order level sampling and identification of HGT using network science. Microorganisms 8, 312 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yakhnin A. V., et al., NusG controls transcription pausing and RNA polymerase translocation throughout the Bacillus subtilis genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 21628–21636 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Czyz A., Mooney R. A., Iaconi A., Landick R., Mycobacterial RNA polymerase requires a U-tract at intrinsic terminators and is aided by NusG at suboptimal terminators. MBio 5, e00931 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burova E., Hung S. C., Sagitov V., Stitt B. L., Gottesman M. E., Escherichia coli NusG protein stimulates transcription elongation rates in vivo and in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 177, 1388–1392 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnson G. E., Lalanne J. B., Peters M. L., Li G. W., Functionally uncoupled transcription-translation in Bacillus subtilis. Nature 585, 124–128 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Payne J. L., Wagner A., The causes of evolvability and their evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 24–38 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.