Significance

This study investigates whether the COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated prejudice and discrimination against racial/ethnic minority groups. Results from a nationally representative survey experiment about roommate selection suggest that incidents of anti-Asian hostility reported in the media are not isolated acts but signal-amplified racism against East Asians. While popular rhetoric has blamed East Asians for the pandemic, we find that COVID-19–associated discrimination has spilled over to South Asians and Hispanics, suggesting a generalized phenomenon of xenophobia. Prejudice fueled by COVID-19 against Asians has been particularly widespread, but for Hispanics, such negative sentiments are mitigated by respondents’ prior social contact with them. These findings highlight the need to develop a multitargeted approach to address racism and xenophobia associated with COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, discrimination, race and ethnicity, prejudice

Abstract

Mounting reports in the media suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has intensified prejudice and discrimination against racial/ethnic minorities, especially Asians. Existing research has focused on discrimination against Asians and is primarily based on self-reported incidents or nonrepresentative samples. We investigate the extent to which COVID-19 has fueled prejudice and discrimination against multiple racial/ethnic minority groups in the United States by examining nationally representative survey data with an embedded vignette experiment about roommate selection (collected in August 2020; n = 5,000). We find that priming COVID-19 salience has an immediate, statistically significant impact: compared to the control group, respondents in the treatment group exhibited increased prejudice and discriminatory intent against East Asian, South Asian, and Hispanic hypothetical room-seekers. The treatment effect is more pronounced in increasing extreme negative attitudes toward the three minority groups than decreasing extreme positive attitudes toward them. This is partly due to the treatment increasing the proportion of respondents who perceive these minority groups as extremely culturally incompatible (Asians and Hispanics) and extremely irresponsible (Asians). Sociopolitical factors did not moderate the treatment effects on attitudes toward Asians, but prior social contact with Hispanics mitigated prejudices against them. These findings suggest that COVID-19–fueled prejudice and discrimination have not been limited to East Asians but are part of a broader phenomenon that has affected Asians generally and Hispanics as well.

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been rising concerns globally that the pandemic has aggravated prejudice and discrimination against racial/ethnic minorities, especially Asians (1, 2). In the United States, Asian Americans reported more than 6,600 incidents of harassment, assault, and hate crimes between March 2020 and March 2021 (3), substantially more than the previous year (4). Evidence based on self-reports, though informative, does not fully capture the extent and nature of the issue (5). Apart from these self-reported instances, has the pandemic increased the less visible, everyday forms of social discrimination against Asians? Additionally, although many consider East Asians the primary victims of COVID-19–related racism, has pandemic-related discrimination affected other racial/ethnic minority groups as well?

To address these questions, we systematically investigate the extent to which COVID-19 has fueled prejudice and discrimination against racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. We do this by collecting a nationally representative survey dataset with an embedded vignette experiment about roommate selection.

Previous research on racial attitudes has focused on how economic, political, demographic, and national security threats lead to increased prejudice and discrimination against minority groups (6–11). These threats include declines in economic advantage, political power, or population share of the dominant group, and acts of terrorism.

We contend that the COVID-19 pandemic has induced a salient infectious disease threat in a way that has affected attitudes and behaviors toward minority groups. The COVID-19 pandemic has created widespread fears and anxieties about personal health and safety, and its origin has been ostensibly linked to a particular ethnic minority group (i.e., East Asian, especially Chinese). To mitigate the perceived threat of disease, individuals may activate their behavioral immune systems (BIS) and subsequent behavioral adaptations (12). BIS may induce people to avoid and discriminate against outgroups, especially cultural and national outgroups that display different physical features or behaviors (i.e., minorities and immigrants) and are thus viewed as possessing heuristic disease cues (13, 14). Existing research has shown that infectious disease outbreaks, such as Ebola and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), activated BIS and subsequently increased prejudice against minority groups and immigrants (15–18).

The impact of COVID-19 may be particularly pronounced compared to previous disease outbreaks because the pandemic has also caused massive economic loss, insecurity, and disruption in social life (19–22). Socioeconomic hardship can amplify the perceived threat of minority groups, especially those typically associated with the pandemic. Compounding these health and socioeconomic shocks is the racist and xenophobic political rhetoric that frames COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” “Asian virus,” or “foreign virus” (1, 23, 24). The intensified threats and racist scapegoating may exacerbate adaptive responses in the form of avoidance and discrimination (17, 25, 26).

Given the processes outlined above, we expect the COVID-19 pandemic to have fueled prejudice and discrimination against those of East Asian backgrounds. Other Asian groups, such as South Asians, may have also experienced increased prejudice and discrimination because Asians in general are often perceived as a homogeneous group by non-Asian Americans (27, 28). Furthermore, COVID-19–fueled prejudice and discrimination may extend beyond East Asians if the COVID-19 pandemic has elevated xenophobic sentiments more broadly. Foreigners or groups perceived as foreign are often considered carriers of pathogens (13, 29). In the case of COVID-19, political rhetoric has further promulgated xenophobic sentiments by offering xenophobic explanations and solutions for the pandemic. In this context, foreign cues can activate strong feelings of disease threat, leading to defensive responses that increase prejudice and discrimination against culturally foreign minority groups (12, 30). In the United States, Asians and Hispanics are the groups perceived as “perpetual foreigners” (31). We thus expect prejudice and discrimination fueled by COVID-19 to extend to other Asians and to Hispanics. In comparison, Whites are perceived as most “American,” followed by Blacks (32, 33). These two groups may thus be less vulnerable to pandemic-related discrimination, particularly if it is rooted in xenophobia.

A small but growing body of research has investigated anti-Asian sentiments amid the COVID-19 pandemic (34–38). To our knowledge, only two published studies have examined attitudes toward minority groups other than Asians (35, 36). These studies point to increased anti-Asian sentiment but are largely based on data from self-reported experiences or convenience samples. We present a summary of these studies in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Our study moves beyond these existing studies in three ways. First, we conducted a nationally representative online survey with an embedded vignette experiment to elicit prejudice and discriminatory intent of the general United States adult population in the social arena, specifically in the context of roommate selection. We studied both prejudice and discriminatory intent. Prejudice captures attitudes, evaluations, or emotional responses toward a social group, whereas discriminatory intent captures action orientation or behavioral intent toward a certain group. We used discriminatory intent as a proxy for discrimination because our study did not observe direct action.

In the experiment, we examined the impact of COVID-19 with a treatment that temporarily increases the salience of the pandemic. This treatment consisted of priming the respondents to think about the pandemic and its impacts on their lives. Our research design strengthens causal inference and permits generalizability of the findings. We examined the treatment effect on prejudice and discriminatory intent toward a hypothetical roommate from a specific racial/ethnic group. Our focus was not on comparing attitudes toward different racial/ethnic groups. This strategy reduces social desirability bias that is common in surveys of racial/ethnic attitudes.

Second, we examined prejudice and discriminatory intent against all major racial/ethnic groups: namely, Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. Among Asians, we further distinguished between East and South Asians. These distinctions allow us to examine whether COVID-19 has fueled prejudice and discrimination against a particular Asian group (e.g., East Asians) or whether such prejudice and discrimination extends more broadly to other Asian and non-Asian groups.

Third, we assessed potential mediating and moderating factors. We first examined the extent to which increased negative perceptions of certain minority groups—along the dimensions of responsibility, courteousness, financial stability, and cultural compatibility—helped explain the treatment effect of COVID-19 salience on prejudice and discrimination. We then investigated whether social and political factors (at the individual and contextual levels) exacerbated or mitigated discrimination fueled by COVID-19. The moderating factors include political orientations, levels of contact with members of minority groups (before the pandemic), and the political progressiveness and ethnic diversity in the respondents’ county of residence.

We use the context of roommate selection to examine prejudice and discrimination. Nearly 6% of the United States adult population—more than 15 million people—currently live with unrelated roommates who are not their romantic partners, and the total number of people to have ever lived with a roommate in their lifetime is much higher (39). Therefore, a large proportion of the population is likely to be familiar with the roommate search process. Even though the scenario of roommate selection may not be relevant or familiar to all Americans, it provides an easily understandable, concrete situation for respondents to express their attitudes and predict their behavior in a social setting. Moreover, in contrast to media reports of occasional but devastating hate crimes in public spaces, the roommate context helps highlight the potential prevalence of everyday prejudice and discrimination in interpersonal relationships, which potentially affects a wider segment of the population.

Overall, the results from our August 2020 nationally representative online survey experiment of 5,000 Americans show that exogenously increasing COVID-19 salience amplified prejudice and discriminatory intent not only against East Asians (the group typically associated with the pandemic), but also against South Asians and Hispanics (groups perceived as foreign).

Materials and Methods

We conducted a nationally representative online survey with experiments of 5,000 American adults between August 13 and August 31, 2020 (40). The survey captured a period when the novel coronavirus had spread widely across all US states and was still on the rise. YouGov, a market research firm that maintains a large panel of respondents, administered the online survey (a detailed description of the sampling and survey procedures is in SI Appendix, Sampling and Survey Procedures). Columbia University's Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study, determining that it was eligible for IRB expedited determination under category 7. All subjects in the survey provided informed consent.

Our survey began with an experiment that randomly exposed half of the respondents to a short paragraph about the current state of COVID-19 (based on an excerpt from World Health Organization 2020) (41), followed by a battery of questions regarding the effects of COVID-19 on employment, earnings, and the health status of respondents and their families, before completing the survey. The experimental text stated: “The novel coronavirus, COVID-19, is a global pandemic. By August 3, 2020, worldwide over 18.3 million individuals have tested positive with COVID-19 and 694,235 have died. The United States is one of the hardest hit countries in terms of infections and mortality, with over 4.8 million infections and 158,495 deaths as of August 3. We would like to ask you a few questions about how the pandemic impacted your life.” The battery of questions is listed in SI Appendix, Text and Questions for the COVID-19 Salience Treatment (Top Layer). We refer to this top layer experimental randomization as the “COVID-19 salience treatment.” We used neutral text for the control group that introduced the survey as a study of life circumstances and opinions. The control group completed the survey first and then viewed the COVID-related text and answered the battery of questions about the impact of COVID-19.

The primary treatment condition temporarily increased the salience of the pandemic by priming the respondents to think about the pandemic and its impact on their lives. In effect, we measured the short-term impact of amplified COVID-19–related thoughts on attitudes and behavioral intent toward racial/ethnic minority groups.

We then used a vignette experiment to elicit prejudice and discriminatory intent in the social context of a roommate search (adapted from refs. 42, 43). We refer to this second layer experimental randomization as the “racial/ethnic treatment.” The vignette asked respondents to consider a scenario in which they were looking for a roommate in “The Big City” and placed an advertisement on a popular website to find one. Each respondent then read one hypothetical email response to their advertisement (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Each response included a single randomized name to signal the race/ethnicity of the hypothetical room-seeker. The vignette and email response were otherwise identical. We used a single name per respondent to reduce social desirability bias (44). We chose these names from prior empirical work (45, 46) to signal one of five racial/ethnic groups: Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, East Asians, and South Asians. We also directly (i.e., “I’m a male/female”) and indirectly (i.e., gendered first name) signaled gender so that the room-seeker’s gender corresponded to that of the respondent (SI Appendix, Table S2).

After reading the vignette and email response, each respondent was presented with six questions about the room-seeker, each on a scale of 0 to 10. The first question (“How likely are you to respond to this person?”) elicited each respondent’s action orientation toward the room-seeker, which captured discriminatory intent. The second question (“How interested are you in living with this person?”) elicited the respondent’s emotions toward the room-seeker, which captured prejudice. Four additional questions elicited the respondents’ views on the hypothetical room-seeker’s qualities relating to responsibility, courteousness, financial stability, and cultural compatibility (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Table S2). These questions were derived from a prior survey that elicited open-ended responses about the most important characteristics of a roommate (43). They therefore tapped into potential stereotypes that could help explain observed patterns of prejudice and discrimination (5).

SI Appendix, Fig. S3 summarizes the two-layer randomization design and sample sizes of the treatment and control groups. SI Appendix, Variables and Methods describes the variables and methods of the analysis. Our analysis confirmed that respondents exposed to the treatment and control conditions did not exhibit systematic differences in observable characteristics (SI Appendix, Table S3).

Results

Treatment Effects Based on the Vignette Experiment.

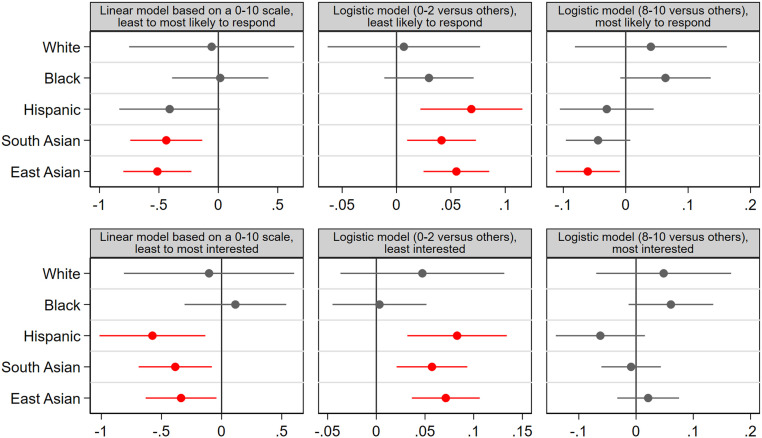

Results from the roommate vignette experiment demonstrate that priming COVID-19 salience heightened prejudice and discriminatory intent against Asians and Hispanics (Fig. 1). The left panel of Fig. 1 presents results based on linear regressions of attitudes scaled from 0 to 10, without controls. In all main models, we excluded respondents of the same race/ethnicity as the room-seeker they evaluated because our focus was on prejudice and discrimination against race/ethnic outgroups.

Fig. 1.

Effect of COVID-19 salience treatment on discriminatory intent (likelihood of responding to room-seeker) and prejudice (interested in living with room-seeker) against room-seekers by signaled race/ethnicity. Each point is based on a different regression model and provides the effect of COVID-19 salience treatment and the 95% confidence interval. The first column presents coefficients based on linear regressions. The second and third columns present average marginal effects based on logistic regressions. Treatment effects that are significant at the 0.05 level are highlighted in red. The samples exclude respondents of the same race/ethnicity as the hypothetical room-seeker. No adjustment for pretreatment characteristics.

Compared to the control group, individuals in the treatment group (exposed to a reminder of COVID-19 and its impact on their lives before taking the survey) exhibited greater discriminatory intent against three racial/ethnic groups. Specifically, the treatment group predicted that they were less likely than the control group to respond to hypothetical room-seekers who were East Asian or South Asian. Individuals in the treatment group also exhibited greater prejudice toward East Asians, South Asians, and Hispanics, as they expressed less interest in living with the room-seeker of these race/ethnicities than members of the control group. The differences in discriminatory intent and prejudice toward White and Black room-seekers—in terms of the likelihood of responding to the room-seeker and interest in living with them—were not statistically significant between the treatment and the control group. The distribution of responses to the question about the likelihood of responding to the room-seeker (0 to 10; separately for the control and treatment groups) is in SI Appendix, Fig. S4.

The treatment effect is especially salient for extreme opposing attitudes (Fig. 1, Center). These results are based on logistic regressions, in which we coded extreme opposition (the three most opposing categories, 0 to 2, in a scale of 0 to 10) as 1, and otherwise as 0. We present the average marginal effects for logistic regressions. For both the discriminatory intent and prejudice questions, individuals in the treatment group were more likely than individuals in the control group to exhibit extremely unfavorable attitudes toward both Asian groups and Hispanics. For example, the treatment group was 7, 4, and 6 percentage points more likely than the control group to signal their strong unwillingness to respond to the Hispanic, South Asian, and East Asian room-seekers, respectively. This was not the case for extremely favorable attitudes (the three most favorable categories, 8 to 10, in a scale of 0 to 10) at the other end of the spectrum (Fig. 1, Right). For favorable attitudes, the treatment effect was mostly nonsignificant, with the exception of attitudes toward East Asians on the response question. The treatment effect on extreme opposition and favorability for White and Black room-seeker was also nonsignificant. Given these findings, we focus on the overall and extreme opposing attitudes toward three groups (East Asian, South Asian, and Hispanic) in the analyses below.

These main results (linear and logistic regressions) hold after controlling for pretreatment covariates (SI Appendix, Table S4) and for the full sample without excluding respondents of the same race/ethnicity as the room-seeker (SI Appendix, Table S5).

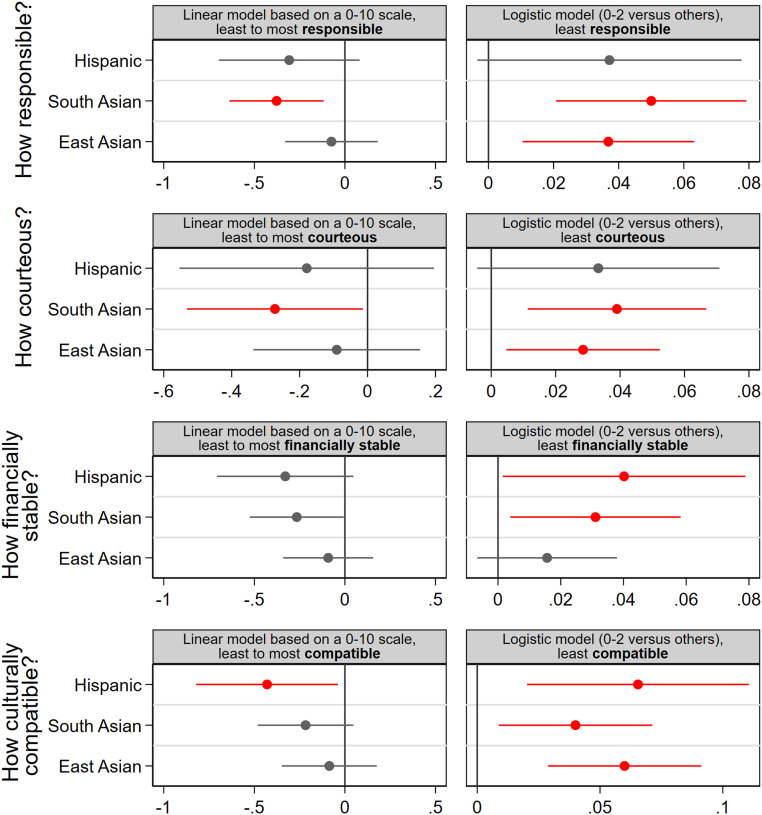

Next, we examined four additional questions in the roommate vignette experiment that tapped into potential stereotypes that could help explain the COVID-19–related prejudice and discriminatory intent against Asians and Hispanics. Fig. 2 shows the treatment effect on the four stereotype responses based on linear and logistic regressions (detailed results are in SI Appendix, Table S7). These findings suggest that the treatment effect is particularly pronounced in shaping extreme negative perceptions. All three racial/ethnic groups were more likely to be perceived by the treatment group as extremely culturally incompatible. Additionally, the two Asian groups were more likely to be disparaged as extremely irresponsible and discourteous by the treatment group than the control group. Finally, the treatment group was more likely to view Hispanics and South Asians as financially unstable than the control group.

Fig. 2.

Effect of COVID-19 salience treatment on stereotypes (responsibility, courteousness, financial stability, and cultural compatibility) of Hispanic and Asian room-seekers. Each point is based on a different regression model and provides the effect of the COVID-19 salience treatment and the 95% confidence interval. The first column presents coefficients based on linear regressions. The second column presents average marginal effects based on logistic regressions. Treatment effects that are significant at the 0.05 level are highlighted in red. The samples exclude respondents of the same race/ethnicity as the hypothetical room-seeker. No adjustment for pretreatment characteristics.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we used Holm–Bonferroni multiple comparison adjustments (47, 48) to jointly test our hypotheses regarding the two main questions (likelihood of responding to the room-seeker and interest in living with the room-seeker) and the four stereotype questions for each racial/ethnic group. The results of this analysis (SI Appendix, Table S8) are generally consistent with the main findings presented in Fig. 2.

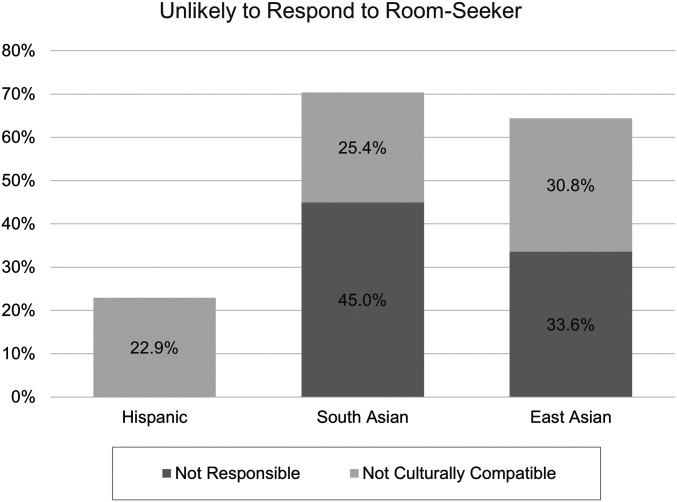

We further conducted a formal mediation analysis to investigate the role of the four stereotypes (mediators) in explaining the overall treatment effect on prejudice and discriminatory intent. We performed a multiple-mediator mediation analysis using simultaneous equations and corrected the SEs using bootstrapping and bias-corrected confidence intervals (49). We focused on extreme opposing attitudes (0 to 2) because Fig. 2 shows that the treatment effect was especially salient for extreme negative perceptions. Results from the mediation analysis (Fig. 3; details in SI Appendix, Table S9) highlight several significant mediating channels. Specifically, for all three minority groups (Hispanics, South Asians, and East Asians), a notable fraction (23 to 31%) of the overall treatment effect was mediated by perceived cultural incompatibility. For the two Asian groups, perceived irresponsibility also served as an important mediator: 34% and 45% of the observed treatment effects on the likelihood of responding question for East Asians and South Asians, respectively, were mediated by perceived lack of responsibility.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of total effect of COVID-19 salience treatment on likelihood of responding to the room-seeker mediated by stereotypes (responsibility, courteousness, financial stability, and cultural compatibility) for Hispanic and Asian room-seekers. Only significant mediators are shown. The outcome and mediating variables are binary and equal 1 if the respondents expressed extremely opposing attitudes (0 to 2 on a 0-to-10 scale). The samples exclude respondents of the same race/ethnicity as the hypothetical room-seeker. All regression models control for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, family income, logged county population size, and region of residency.

Overall, the results suggest that Asians and Hispanics are more vulnerable to COVID-related prejudice and discriminatory intent partly because of elevated negative perceptions about their lack of responsibility and/or cultural compatibility. This finding is consistent with the threat theory, in which health and socioeconomic threats can accentuate the outgroup status of minorities in various ways, such as increasing their perceived foreignness and decreasing their perceived responsibility. Altogether, the results based on the six questions suggest a consistent pattern of responses in which the COVID-19 treatment increased negative perceptions, attitudes, and behavioral intent toward Asian and Hispanic groups.

Moderating Factors.

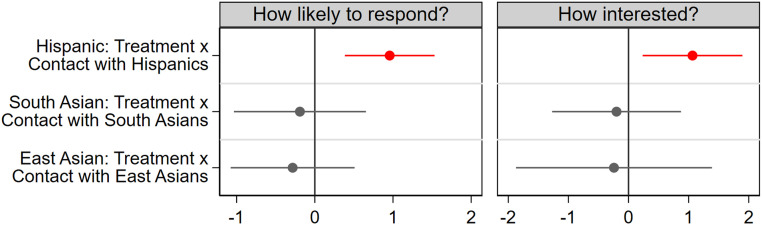

We found no moderating role of social and political factors for prejudice and discriminatory intent against Asian groups (SI Appendix, Table S10). This suggests that COVID-19–related prejudices toward Asians are widespread, similarly affecting respondents with different experiences and from diverse political and social environments.

The notable exception is the moderating role of social contact on prejudice and discriminatory intent against Hispanics (Fig. 4): contact with Hispanics prior to COVID-19 helped mitigate the negative treatment effect. Specifically, the interaction between treatment and social contact was positive and statistically significant. This means that individuals with at least some prior contact (some or a lot of regular contact) with Hispanics were less likely to have increased negative attitudes toward this group when primed with COVID-19 salience than those with little or no prior contact with Hispanics.

Fig. 4.

Moderating effect of pre-COVID-19 social contact with Hispanics or Asians. Each point is based on a different regression model and provides the estimate of the interaction between the COVID-19 salience treatment and prior social contact with a specific racial/ethnic group (and the 95% confidence interval). The estimates are based on linear regressions. Interactions that are significant at the 0.05 level are highlighted in red. The samples exclude respondents of the same race/ethnicity as that of the hypothetical room-seeker. All regression models control for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, family income, logged county population size, and region of residency.

This finding is consistent with intergroup contact theory (50, 51), which postulates that direct contact with outgroups fosters positive attitudes toward those groups and reduces prejudice against them. However, the moderating effect of social contact held for Hispanics and not Asians. Contact with Asians prior to the pandemic did not have a similar effect.

Conclusion and Discussion

We conducted a nationally-representative online survey with an embedded experiment to investigate the causal impact of COVID-19–related priming on prejudice and discrimination against multiple racial/ethnic minority groups in the United States. We found evidence that amplifying COVID-19 salience increases prejudice and discriminatory intent against East Asians, South Asians, and Hispanics in the context of roommate selection. The treatment effect is largely driven by increased extreme negative attitudes rather than decreased extreme positive attitudes toward the three minority groups. This suggests that the potential impact of COVID-19 lies in moving people who hold neutral or moderately negative views to extremely negative views about the three minority groups rather than shifting people who hold extremely positive attitudes about them to a more negative direction.

The mediation analysis indicated that elevated negative perceptions about the cultural compatibility and responsibility of Asians and Hispanics have shaped prejudice and discrimination. This suggests that COVID-19 may have increased xenophobic sentiments toward minority groups, who are often regarded as foreign. The pandemic may have also led respondents to perceive Asians as irresponsible, presumably because Asians were associated with the origin and initial spread of the coronavirus.

With respect to the moderation analysis, we found that social and political factors did not mitigate the negative treatment effect on prejudice and discriminatory intent against Asians. This suggests that COVID-19–related discrimination against Asians has been a generalized response, largely emanating from specific health threats given their perceived association with the pandemic. For Hispanics, in contrast, prior social relationship with this group may have inoculated people against increased prejudice and discrimination during the pandemic. This suggests that prejudiced attitudes toward Hispanics may largely reflect general xenophobic sentiments.

Overall, our study demonstrates that major health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can have important, broad ramifications for racial attitudes and behaviors. Our findings add to the group-threat theory by identifying infectious disease threat as a consequential factor for shaping attitudes and behaviors toward racial/ethnic minority groups. The COVID-19 pandemic is unique in the respect that it has also resulted in tremendous social and economic threats and in the United States, has been accompanied by an uptick in racist political rhetoric. Together, such health and socioeconomic threats activate behavior adaptations by discriminating against outgroups typically associated with the disease (i.e., East Asians) and, more broadly, against groups that are perceived as foreign (i.e., Asians and Hispanics).

Our findings suggest that rising anti-Asian hostilities portrayed in popular media are not isolated incidents but are signs of a widespread phenomenon reflecting amplified prejudice and discrimination against Asians in the wake of COVID-19. The pandemic also seems to have heightened xenophobic sentiment more generally as it has fueled discrimination against not just Asians but Hispanics as well. There is a long history of associating the threat of disease with Asian people and immigrants (12, 52), and the COVID-19 pandemic has brought anti-Asian and anti-immigrant sentiments to the forefront.

We could not measure the overall effect of COVID-19 on racial attitudes because the pandemic impacted all Americans. Rather, we have studied the impact of priming COVID-19 salience on prejudice and discriminatory intent against minority groups. Our treatment of priming COVID-19 salience was arguably not very strong because of the temporary nature of the treatment condition and the fact that our survey was conducted during the pandemic when the entire nation was affected. Even respondents in the control group were likely to have COVID-related concerns as they completed the survey. Hence, we may have underestimated the true influence of the pandemic in shaping racial attitudes.

Whereas the roommate vignette may not have been immediately relevant to all the respondents, we believe it is a scenario that most people can relate to and use their own experiences and beliefs to predict their own behavior. Most people have opinions about who they would like to get close to, and the roommate scenario offers one concrete circumstance that forces respondents to think more deeply about their own attitudes related to race/ethnicity. In addition, reports of hate crimes generally focus on aggression and discrimination by strangers in public spaces. There is much less attention paid to other subtle forms of prejudice and discrimination that largely go unnoticed but can affect the lives of minority groups and their integration into the society at large. The specific setting of roommate search allows us to tap into the less visible, everyday forms of social discrimination. Furthermore, the questions in our experiment compelled respondents to reflect on the possible reasons why they would or would not respond to the room-seeker (various stereotypes). The results then provide important insights into how COVID-19 has fueled generalized negative perceptions about minority groups with respect to cultural compatibility and responsibility. These negative perceptions may go beyond the context of roommate selection and affect behaviors in other social settings.

While our study focuses on attitudes and discriminatory action orientations, we did not directly observe actual discriminatory action (e.g., roommate seekers who make real decisions about real applicants). Previous research has demonstrated that harboring negative intentions toward minority groups can provoke discriminatory action in the real world (7, 53). In this respect, increased prejudice against Asians and Hispanics during COVID-19 may impair individual well-being, strain interracial relations, and constrain the economic and social opportunities of these racial/ethnic minority groups.

We hope that this research will inform policymakers and the society at large about the extent and nature of COVID-19–related prejudice and discrimination, which broadly affects Asians and also extends to Hispanics. The recent enactment of the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act is the first legislative action in response to anti-Asian hate crimes. It is an important step, but only the first step for combating racism and xenophobia associated with the pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Shapiro, Maria Abascal, and Tiffany Huang for helpful comments. This research was supported by the Columbia Population Research Center, the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy, the Center for Pandemic Research, and the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2105125118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Study materials (data and code analyses) can be found at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/a6ewy/) (40).

References

- 1.Devakumar D., Shannon G., Bhopal S. S., Abubakar I., Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses. Lancet 395, 1194 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung R. Y.-N., Erler A., Li H.-L., Au D., Using a public health ethics framework to unpick discrimination in COVID-19 responses. Am. J. Bioeth. 20, 114–116 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeung R., Yellow Horse A. J., Cayanan C., Au D., Stop AAPI hate national report (Asian Pacific Planning and Policy Council, 2021). https://stopaapihate.org/2020-2021-national-report/. Accessed 31 May 2021.

- 4.Farivar M., Race in America: Hate crimes targeting Asian Americans spiked by 150% in major US cities (VOA News, Washington, DC, 2021), https://www.voanews.com/usa/race-america/hate-crimes-targeting-asian-americans-spiked-150-major-us-cities. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaddis S. M., Understanding the “how” and “why” aspects of racial-ethnic discrimination: A multimethod approach to audit studies. Sociol. Race Ethn. (Thousand Oaks) 5, 443–455 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumer H., Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1, 3–7 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaushal N., Kaestner R., Reimers C., Labor market effects of September 11th on Arab and Muslim residents of the United States. J. Hum. Resour. 42, 275–308 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legewie J., Terrorist events and attitudes toward immigrants: A natural experiment. Am. J. Sociol. 118, 1199–1245 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettigrew T. F., Intergroup contact theory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 49, 65–85 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quillian L., Prejudice as a response to perceived group threat: Population composition and anti-immigrant and racial prejudice in Europe. Am. Sociol. Rev. 60, 586–611 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiske S. T., What we know now about bias and intergroup conflict, the problem of the century. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 11, 123–128 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faulkner J., Schaller M., Park J. H., Duncan L. A., Evolved disease-avoidance mechanisms and contemporary xenophobic attitudes. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 7, 333–353 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makhanova A., Miller S. L., Maner J. K., Germs and the out-group: Chronic and situational disease concerns affect intergroup categorization. Evol. Behav. Sci. 9, 8–19 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaller M., Park J. H., The behavioral immune system (and why it matters). Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20, 99–103 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inbar Y., Westgate E. C., Pizarro D. A., Nosek B. A., Can a naturally occurring pathogen threat change social attitudes? Evaluations of gay men and lesbians during the 2014 Ebola epidemic. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 7, 420–427 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim H. S., Sherman D. K., Updegraff J. A., Fear of Ebola: The influence of collectivism on xenophobic threat responses. Psychol. Sci. 27, 935–944 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Shea B. A., Watson D. G., Brown G. D., Fincher C. L., Infectious disease prevalence, not race exposure, predicts both implicit and explicit racial prejudice across the United States. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 11, 345–355 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dutta S., Rao H., Infectious diseases, contamination rumors and ethnic violence: Regimental mutinies in the Bengal Native Army in 1857 India. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 129, 36–47 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker S. R., Bloom N., Davis S. J., Terry S. J., Covid-induced economic uncertainty. NBER working paper (2020), https://www.nber.org/papers/w26983. Accessed 31 May 2021.

- 20.Coibion O., Gorodnichenko Y., Weber M., Labor markets during the COVID-19 crisis: A preliminary view. NBER working paper (2020). https://www.nber.org/papers/w27017. Accessed 31 May 2021.

- 21.Lawson M., Piel M. H., Simon M., Child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consequences of parental job loss on psychological and physical abuse towards children. Child Abuse Negl. 110, 104709 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Wachter T., Lost generations: Long-term effects of the COVID-19 crisis on job losers and labour market entrants, and options for policy. Fisc. Stud. 41, 549–590 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darling-Hammond S., et al., After “The China Virus” went viral: Racially charged coronavirus coverage and trends in bias against Asian Americans. Health Educ. Behav. 47, 870–879 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry S. L., Whitehead A. L., Grubbs J. B., Culture wars and COVID‐19 conduct: Christian nationalism, religiosity, and Americans’ behavior during the coronavirus pandemic. J. Sci. Study Relig. 59, 405–416 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan L. A., Schaller M., Prejudicial attitudes toward older adults may be exaggerated when people feel vulnerable to infectious disease: Evidence and implications. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 9, 97–115 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keil R., Ali H., Multiculturalism, racism and infectious disease in the global city: The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak in Toronto. Topia 16, 23–49 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Espiritu Y., Espiritu Y., Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identities (Temple University Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang D., Gee G. C., Bahiru E., Yang E. H., Hsu J. J., Asian-Americans and Pacific islanders in COVID-19: Emerging disparities amid discrimination. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 3685–3688 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petersen M. B., Healthy out-group members are represented psychologically as infected in-group members. Psychol. Sci. 28, 1857–1863 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park J. H., Faulkner J., Schaller M., Evolved disease-avoidance processes and contemporary anti-social behavior: Prejudicial attitudes and avoidance of people with physical disabilities. J. Nonverbal Behav. 27, 65–87 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim C. J., The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Polit. Soc. 27, 105–138 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaddis S. M., Assessing immigrant generational status from names: Evidence for experiments examining racial/ethnic and immigrant discrimination. (SSRN, 2019), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3022217. Accessed 31 May 2021.

- 33.Kim N. Y., “Critical thoughts on Asian American assimilation in the Whitening literature” in Contemporary Asian America, Zhou M., Ocampo A. C., Eds. (New York University Press, ed. 3, 2016), pp. 554–575. [Google Scholar]

- 34.He J., He L., Zhou W., Nie X., He M., Discrimination and social exclusion in the outbreak of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 2933 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reny T. T., Barreto M. A., Xenophobia in the time of pandemic: Othering, anti-Asian attitudes, and COVID-19. Polit. Groups Identities. 10.1080/21565503.2020.1769693. Accessed 31 May 2021. [DOI]

- 36.Ruiz N. G., Horowitz J., Tamir C., Many Black and Asian Americans say they have experienced discrimination amid the COVID-19 outbreak (Pew Research Center, 2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/07/01/many-black-and-asian-americans-say-they-have-experienced-discrimination-amid-the-covid-19-outbreak/. Accessed 31 May 2021.

- 37.Rzymski P., Nowicki M., COVID-19-related prejudice toward Asian medical students: A consequence of SARS-CoV-2 fears in Poland. J. Infect. Public Health 13, 873–876 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu C., Qian Y., Wilkes R., Anti-Asian discrimination and the Asian-White mental health gap during COVID-19. Ethn. Racial Stud. 44, 1–17 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Census Bureau , American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Household Type by Relationships (U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu Y., Kaushal N., Huang X., Gaddis S.M., Data: COVID-19 Priming and Prejudice and Discriminatory Intent Against Asians and Hispanics. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/a6ewy/. Accessed 10 August 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Coronavirus WHO (COVID-19) Dashboard (2021). Covid19.who.int. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 31 May 2021.

- 42.Gaddis S. M., Ghoshal R., Searching for a roommate: A correspondence audit examining racial/ethnic and immigrant discrimination among millennials. Socius (2020), 10.1177/2378023120972287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Gaddis S. M., Ghoshal R., Dynamic racial triangulation: Examining the racial order using two experiments on discrimination among millennials. SSRN (2019), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3022208. Accessed 31 May 2021.

- 44.Auspurg K., Hinz T., Liebig S., Sauer C., “The factorial survey as a method for measuring sensitive issues” in Improving Survey Methods: Lessons from Recent Research, Engel U., Jann B., Lynn P., Scherpenzeel A., Sturgis P., Eds. (Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2015), pp. 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaddis S. M., How Black are Lakisha and Jamal? Racial perceptions from names used in correspondence audit studies. Sociol. Sci. 4, 469–489 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaddis S. M., Racial/ethnic perceptions from Hispanic names: Selecting names to test for discrimination. Socius (2017), 10.1177/2378023117737193. [DOI]

- 47.Holm S., A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 6, 65–70 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen S. Y., Feng Z., Yi X., A general introduction to adjustment for multiple comparisons. J. Thorac. Dis. 9, 1725–1729 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Preacher K. J., Hayes A. F., Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allport G. W., Clark K., Pettigrew T., The Nature of Prejudice (Addison-Wesley, 1954). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pettigrew T. F., Tropp L. R., A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 751–783 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green E. G., et al., Keeping the vermin out: Perceived disease threat and ideological orientations as predictors of exclusionary immigration attitudes. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 20, 299–316 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Talaska C. A., Fiske S. T., Chaiken S., Legitimating racial discrimination: Emotions, not beliefs, best predict discrimination in a meta-analysis. Soc. Justice Res. 21, 263–396 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Study materials (data and code analyses) can be found at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/a6ewy/) (40).