Abstract

This study estimates what 2020 national US savings would have been using international reference pricing rather than US manufacturer and net prices for insulins and 50 top brand-name drugs.

High prescription drug prices have important implications for health care spending,1 patient financial burden,2 and adherence.3 Prices for brand-name drugs in particular are higher in the US compared with other high-income countries, most of which regulate drug prices. However, inconsistent availability of data on net prices (ie, prices after rebates and other discounts) complicates international comparisons of drug prices. A 2021 study found that US prices for brand-name drugs were 344% of those in other high-income countries at manufacturer (“list”) prices, but the difference was smaller (230%) after an adjustment to approximate lower US net prices.4

The Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act, HR 3, would allow the US Secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate prices with drug manufacturers on behalf of Medicare and private insurers, up to a cap of 120% of prices in 6 countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the UK). Negotiation would apply to all insulins and at least 25 other single-source, brand-name drugs selected by the secretary in the first year and 50 in the second year. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that this application of international reference pricing, a price control tool used by many other countries, would save $456 billion for Medicare alone over 10 years.5

We estimated what 2020 national US savings would have been at HR 3 maximum international prices rather than US manufacturer and net prices for insulins and 50 top brand-name drugs by sales.

Methods

We linked 2020 SSR Health product-level US net sales data to 2020 IQVIA MIDAS product-level estimates of national volume and sales at manufacturer prices for the US and all 6 HR 3 countries. We identified insulins and the top 50 single-source brand-name products in terms of US net sales. We calculated US net prices by dividing product US net sales from SSR Health by US volume from MIDAS. We calculated what payments to drug manufacturers would have been if 2020 US volumes for study products were bought at US manufacturer prices (from MIDAS), US net prices (as described above), and international prices (defined as 120% of volume-weighted mean MIDAS manufacturer prices across HR 3 countries). We compared 2020 US spending for study products at different prices, first overall and then by therapeutic class (from SSR Health), to assess whether US net-to-international reductions differ by class. We analyzed data using Stata, version 16. See the Supplement for additional details.

Results

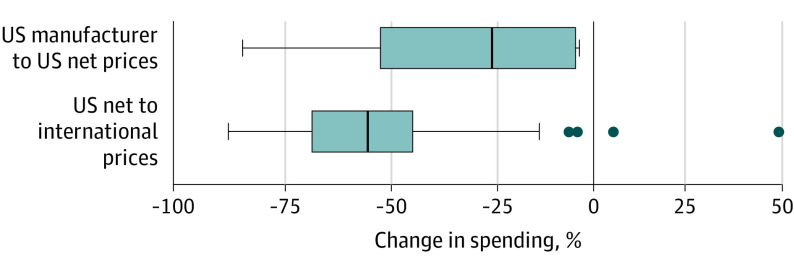

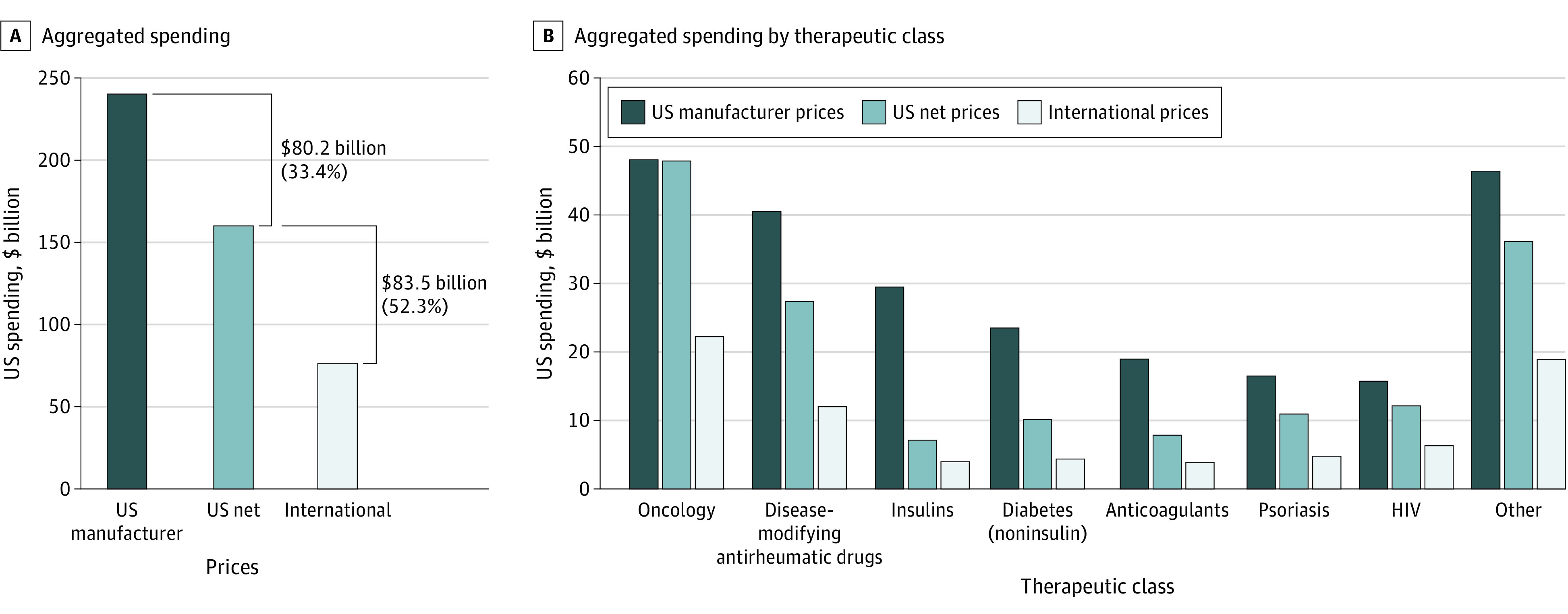

International reference pricing would have lowered 2020 US spending on study products by 52.3% or $83.5 billion, from $159.9 billion at US net prices to $76.3 billion (Figure 1A). For comparison, US spending at manufacturer prices was $240.1 billion. US net-to-international discounts were relatively larger and more tightly distributed (median [IQR] of 52.0% [24.8%]) compared with US net-to-manufacturer discounts (median [IQR] of 21.5% [48.0%]; Wilcoxon signed rank P < .001) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Aggregated Spending on Prescription Drugs at US Manufacturer, US Net, and International Prices.

Analysis of SSR Health US net sales and IQVIA MIDAS sales at manufacturer prices and volume data for the US and 6 HR 3 countries. The analysis is limited to insulins (10 SSR Health products) and 50 select single-source, brand-name drugs (including 2 SSR Health products assigned to the anticoagulant class, 4 noninsulin diabetes drugs, 4 HIV drugs, 4 psoriasis drugs, 5 disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, 15 oncology drugs, and 16 other drugs).

Figure 2. Product-Level Percent Changes in Spending at 2020 US Volume and Different Prices.

The analysis was limited to 10 insulin products and 50 other select single-source, brand-name drugs. Vertical lines through the solid boxes represent medians, the widths of the solid boxes mark the IQR, the whiskers represent adjacent values, which are defined as the largest and smallest data points within 1.5 times the IQR, and dots indicate points that fall beyond the whiskers.

US net-to-international discounts ranged from 44.4% to 57.3% across therapeutic classes (Figure 1B). Spending would have been 53.7% lower at international rather than US net prices for oncology drugs, for which US manufacturer-to-net discounts are relatively small. Spending would have been 44.4% lower at international prices for insulins, for which US manufacturer-to-net discounts are substantial.

Discussion

A national US net-to-international discount of 52% is lower than the estimate of the Congressional Budget Office of 68% for Medicare.6 The current analysis does not reflect several components of HR 3, including price negotiation, and Medicare vs national net prices may differ. The 52% discount is likely conservative due to data limitations, including use of net prices to manufacturers rather than to payers (including supply chain markups) and the absence of net price data for HR 3 countries. Furthermore, actual spending under HR 3 may be lower if Medicaid and other payers already face subinternational prices for some drugs. Although international reference pricing would yield considerable savings, other important considerations around the design and implementation of drug price regulation include incentives for research and development, industry launch and pricing strategies, and increasing utilization in response to lower prices.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

Appendix

References

- 1.Keehan SP, Cuckler GA, Poisal JA, et al. National Health Expenditure projections, 2019-28: expected rebound in prices drives rising spending growth. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(4):704-714. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang EJ, Galan E, Thombley R, et al. Changes in drug list prices and amounts paid by patients and insurers. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2028510-e2028510. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirzinger A, Lopes L, Wu B, Brodie M. KFF tracking poll February 2019: prescription drugs. KFF Health. March 1, 2019. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/kff-health-tracking-poll-february-2019-prescription-drugs/

- 4.Mulcahy A, Whaley C, Tebeka M, Schwam D, Edenfield N, Becerra-Ornelas A. International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Current Empirical Estimates and Comparisons With Previous Studies. RAND Corp; 2021. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2956.html [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budgetary Effects of H.R. 3, the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act. Congressional Budget Office; 2019. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/55936

- 6.Adams C, Herrnstadt H. CBO’s model of drug price negotiations under the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act. Congressional Budget Office; February 2021. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56905

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix