Abstract

This is the first report of a case in which diagnosis of en-plaque tuberculoma on the basis of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings was confirmed by a Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex-specific PCR assay of cerebrospinal fluid. The accuracy of the diagnosis was supported by good response to antitubercular drugs, which was shown by repeat MRI studies performed after treatment.

We present a case report describing a patient in whom the tuberculous etiology of central nervous system (CNS) tuberculosis with extremely rare presentation, namely en-plaque tuberculoma, was established by PCR.

Case report.

A 62-year-old Indian man, who was a scientist by profession, was admitted to the neurology ward of Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Thiruvananthapuram, India, with a 25-day history of low-grade intermittent fever and sore throat. Two weeks into the illness, he had developed cough with mucoid expectoration, for which he had received azithromycin for 3 days because of a right lower zone pneumonia tentatively diagnosed on the basis of X-ray findings of pneumonitis present in the lower zone of the right lung along with clinical features of pneumonia. Three days prior to hospitalization he had developed continuous severe bifrontal headache and vomiting. The day prior to admission he had become delirious, could not identify his relations, and talked out of context. He had had no other significant medical illness, nor did he have any other prominent systemic symptoms. He had no history or family history of tuberculosis. At entry, he was febrile (99°F), conscious, disoriented, and restless (his pulse was 100 beats per min, and his blood pressure was 120/70 mm Hg). Systemic examination excluding the nervous system was unremarkable; however, neurological examination revealed a confused individual who was disoriented as to time, place, and person. The optic fundi showed mild papilledema in both eyes. He had a left homonymous hemianopia judged by menace. There was no other cranial nerve dysfunction or lateralizing motor deficits. Reflexes were normal. He had neck stiffness and a positive Kernig’s sign.

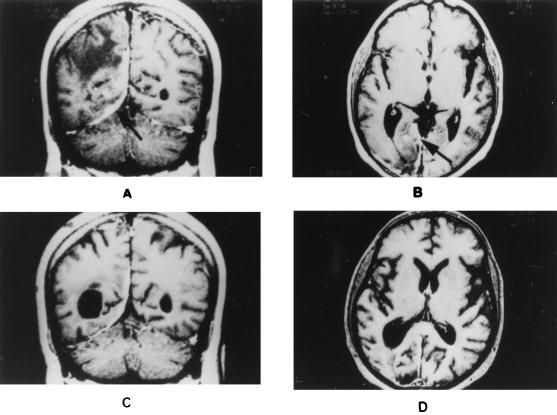

Laboratory evaluation revealed normal results for urine analysis, blood counts, and biochemistry. The sedimentation rate was 14 mm/h. Examination of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed 200 leukocytes/mm3, which were all lymphocytes. The protein content in CSF was 80 mg/dl, that of sugar was 104 mg%, and that of immunoglobulin G was 7 mg/dl. There were no demonstrable bacilli, acid-fast bacteria, or fungi in the smear. CSF culture and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Mycobacterium tuberculosis were negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the head showed an irregular enhancing lesion involving the right occipital cortex and suggestive of early cerebritis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed a meninges-based lesion limited to the tentorial surface and the posterior falx on the right side, with nodular enhancement. There were parenchymal edema and mass effect with minimal subfalcine herniation (Fig. 1A and B). The MRI-based diagnosis was en-plaque tuberculoma. En-plaque tuberculoma is an uncommon manifestation of CNS tuberculosis and presents as a solitary, focal, caseous plaque-like lesion, globular or irregular in outline and 1 or 2 mm to 1 cm in diameter, situated deep in a sulcus in relation to the meninges. It is considered to be a likely source of diffuse meningitis and is the result of bacillemia that occurs during the development of the primary lesion or after primary progressive infection (12). The CT findings for en-plaque tuberculoma were described for the first time by Welchman in 1979 (15). It is possible to diagnose this type of CNS tuberculosis based on MRI characteristics like those described for our patient; the notable feature is its plaque-like extension in the meninges together with marked nodular enhancement on contrast administration (1, 3, 9). However, to increase the confidence in the diagnosis of tuberculosis, confirmation by microbiological or histological means, namely, by demonstration of acid-fast bacilli or caseating granuloma, respectively, is desirable.

FIG. 1.

MRI images of the brain. (A) T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium enhancement showing the involvement of the tentorium and parenchymal edema observed preceding antitubercular treatment. (B) T1-weighted MRI showing the falx-based lesion with nodular enhancement by gadolinium observed preceding antitubercular treatment. (C) T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium enhancement showing that the lesion in the tentorium and falx regressed following antitubercular treatment. (D) T1-weighted MRI showing that the initial lesion regressed with resolution of the nodular enhancement by gadolinium following antitubercular treatment. Arrows indicate lesions in the tentorium and falx.

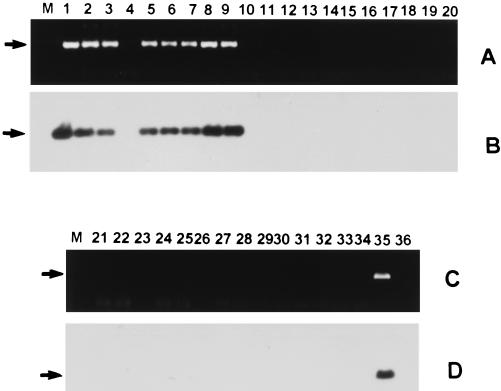

In this patient, diagnosis was confirmed by detection of M. tuberculosis DNA in CSF by PCR with an assay based on amplification of devR gene sequences. The devR gene (GenBank nucleotide sequence accession no. U22037) encodes a response regulator that is part of a two-component signal transduction system of M. tuberculosis identified in our laboratory (1a). By using DNA from 22 mycobacterial species (including those of the M. tuberculosis complex and Mycobacterium leprae) and 12 nonmycobacterial species, a 513-bp fragment was amplified from DNA of organisms that belong to the M. tuberculosis complex and not from DNA of other mycobacteria and nonmycobacterial species (Fig. 2A and C). The authenticity of the amplified product was established by hybridization of immobilized PCR products to an internal oligonucleotide, devR1, mapping within the devR gene (Fig. 2B and D).

FIG. 2.

Specificity analysis of devR-based PCR assay. DNA amplifications were performed by using primers devRf and devRr, and the reaction products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane, and hybridized with 32P-labeled internal oligonucleotide devR1 (5′ CCGTCCAGCGCCCACATCTTT 3′) at 55°C in a solution containing 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 10× Denhardt’s solution, 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 200 μg of salmon sperm DNA/ml. The blot was washed twice at room temperature with 2× SSC–0.1% SDS and twice at 58°C for 15 min with 0.2× SSC–0.2% SDS. The ethidium bromide and hybridization profiles are shown in panels A and C and panels B and D, respectively. The amplified product of 513 bp is indicated by arrows. Lanes M, molecular weight marker. Other lanes contain the products from the following organisms: lane 1, Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv; lane 2, M. tuberculosis H37Ra; lane 3, Mycobacterium bovis BCG; lane 4, Mycobacterium microti; lanes 5 to 9, clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis C1084, P8460, 779634, 8473, and C1270, respectively, obtained from the Department of Microbiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences and Tuberculosis Research Center, Chennai, India; lane 10, Mycobacterium avium; lane 11, Mycobacterium intracellulare; lane 12, Mycobacterium scrofulaceum; lane 13, Mycobacterium xenopi; lane 14, Mycobacterium fortuitum; lane 15, Mycobacterium phlei; lane 16, Mycobacterium gordonae; lane 17, Mycobacterium vaccae; lane 18, Mycobacterium kansasii; lane 19, Mycobacterium smegmatis; lane 20, Mycobacterium gastri; lane 21, Mycobacterium chelonae; lane 22, M. leprae; lane 23, Nocardia asteroides; lane 24, Staphylococcus aureus; lane 25, Streptococcus faecalis; lane 26, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; lane 27, Aspergillus niger; lane 28, Aspergillus fumigatus; lane 29, Candida albicans; lane 30, Corynebacterium diphtheriae; lane 31, Klebsiella pneumoniae; lane 32, Streptococcus pneumoniae; lane 33, Streptomyces aureofaciens; lane 34, Escherichia coli; lane 35, M. tuberculosis DNA-positive control; lane 36, DNA-negative control.

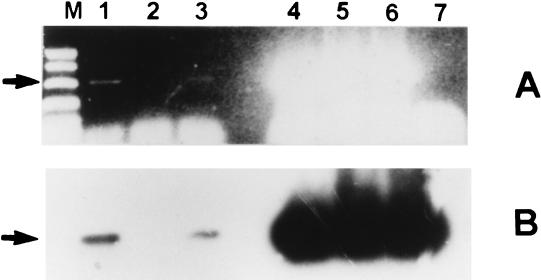

DNA was isolated from the CSF specimen of the patient by heating the sediment in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min at 95°C. The devR gene target was used for the PCR test, as it was extremely specific for organisms belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex. Briefly, 40 μl of a reaction mixture containing 0.5 μM (each) primers devRf and devRr (devRf, 5′ GGTGAGGCGGGTTCGGTCGC 3′; devRr, 5′ CGCGGCTTGCGTCCGACGTTC 3′), 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1.0 U of Taq DNA polymerase and 2 μl of concentrated CSF specimen were subjected to amplification (together with inhibitor check reactions) with the following profile: 10 min at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C and 90 s at 70°C and a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. Reaction mixture (35 μl) was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, and the amplified product was visualized by ethidium bromide staining (Fig. 3A) and was further confirmed by Southern blot hybridization with 32P-labeled oligonucleotide devR1 (Fig. 3B). The test was completed in 36 h, and the result was made immediately available to the treating physicians (authors M. D. Nair and K. Radhakrishnan).

FIG. 3.

Amplification of M. tuberculosis DNA from CSF of tuberculoma patient. Amplification reaction products were electrophoresed and hybridized as described in the legend for Fig. 2. Panels A and B present an ethidium bromide profile and a hybridization profile, respectively. Lane M, molecular weight marker; lane 1, DNA from undiluted CSF; lane 2, DNA from 1:10 diluted CSF; lane 3, DNA from 1:50 diluted CSF; lane 4, undiluted CSF plus M. tuberculosis DNA; lane 5, 1:50 diluted CSF plus M. tuberculosis DNA; lane 6, M. tuberculosis DNA-positive control; lane 7, DNA-negative control.

After PCR-based diagnosis, the patient was treated with four antitubercular drugs, i.e., isoniazid (300 mg), rifampin (450 mg), pyrazinamide (1,500 mg), and ethambutol (600 mg), in combination with tapering doses of steroids for 5 weeks. He showed steady improvement in his clinical status with subsidence of fever and improvement in general well-being by the time of discharge (after 12 days of hospitalization). A repeat MRI study performed after one and a half months of antitubercular chemotherapy showed reduction in the swelling of the right occipital lobe as well as of the meningeal enhancement. The parenchymal enhancement seen previously also had disappeared (Fig. 1C and D). The day after the repeat MRI study, he was back at his laboratory and worked regular hours. Three months later, ethambutol was withdrawn; the other three antitubercular drugs are being continued for a period of 1 year. The latest MRI study, done after 6 months of antitubercular treatment, revealed almost-normal findings except for healed scar sequelae (not shown).

Discussion.

This particular patient presented initially with a symptom of pneumonia, and later early cerebritis was suspected on the basis of CT scan morphology. However, MRI of the brain suggested a diagnosis of en-plaque tuberculoma. Although tuberculosis of the CNS is a rare entity in developed countries, it continues to pose a major health hazard in developing countries, including India (2, 8), and can present with diverse manifestations (11). As mentioned above, en-plaque tuberculoma is an extremely rare presentation of CNS tuberculosis, and in this patient, the demonstration of M. tuberculosis in the CSF specimen was critical in clinching the diagnosis in the face of negative results for the smear, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and subsequent culture. On the basis of MRI findings, antitubercular drugs were started and continued in the light of a positive PCR result for M. tuberculosis. The patient demonstrated a good response to antitubercular drugs, and this was reflected in repeat MRI studies. Thus, in this patient, PCR assay was found to be a sensitive test for detection of M. tuberculosis DNA in CSF that was both smear negative and culture negative.

Although there are many reports on the use of PCR on CSF specimens for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis (4–6, 10, 14), to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on diagnosis of en-plaque tuberculoma by PCR. While MRI provided an understanding of the topography of the lesion, PCR helped in establishing the diagnosis of tuberculosis. In the absence of microbiological proof, the treatment of brain tuberculoma requires an empirical trial with antitubercular drugs for a period of 6 to 8 weeks with follow-up MRI or CT scans to examine resolution of the lesion (7, 13). Therefore, we believe PCR holds promise for use as a routine diagnostic tool in the rapid detection of M. tuberculosis in paucibacillary specimens, such as CSF.

Acknowledgments

K. K. Singh is thankful for financial support obtained from reimbursement subcontract N01-AI-45244 awarded to J.S.T. under the Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Research Unit by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. The work was financed by funds received by J.S.T. from the Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science & Technology, Government of India.

P. N. Tandon and I. Nath are sincerely thanked for their continuous support and encouragement. We thank K. Prasad for his critical suggestions on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chang K H, Han M H, Rah J K, Kim I O, Han M C, Choi K S, Kim C W. Gd-DTPA enhanced M R imaging in intracranial tuberculomas. Neuroradiology. 1990;32:19–25. doi: 10.1007/BF00593936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Dasgupta, N., K. K. Singh, V. Kapur, K. Jyothisri, and J. S. Tyagi. Identification and characterization of a two-component regulatory system devR-devS that is differentially expressed in the virulent H37Rv strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Submitted for publication.

- 2.Dastur H M, Desai A D. A comparative study of brain tuberculomas and gliomas based upon 107 case reports of each. Brain. 1965;88:375–396. doi: 10.1093/brain/88.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta R K, Jena A, Sharma A, Guha D K, Khushu S, Gupta A K. M R imaging of intracranial tuberculoma. J Comput Assisted Tomogr. 1988;12:280–285. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198803000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kox L F, Kuijper S, Kolk A H. Early diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis by polymerase chain reaction. Neurology. 1995;45:2228–2232. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.12.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin J J, Harn H J, Hsuy Y D, Tsao N L, Lee H S, Lee W H. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis by polymerase chain reaction assay of cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol. 1995;242:147–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00936887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen I N, Kox L F, Pham L D, Kuijper S, Kolk A H. The potential contribution of the polymerase chain reaction to the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:771–776. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550080093017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peatfield R C, Shawdon H H. 5 cases of intracranial tuberculoma followed by serial computed tomography. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1979;42:373–379. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.42.4.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramamurthi B. Intracranial tumours in India: incidence and variations. Int Surg. 1973;58:542–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salgado P, Del Brutto O H, Talamas O, Zenteno M A, Carbajal J R. Intracranial tuberculoma M R imaging. Neuroradiology. 1989;31:299–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00344170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanker P, Manjunath N, Mohan K K, Prasad K, Behari M, Shriniwas, Ahuja G K. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis by polymerase chain reaction. Lancet. 1991;337:5–7. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tandon P N, Pathak S N. Tuberculosis of the central nervous system. In: Spillane J D, editor. Tropical neurology. London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1973. pp. 61–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tandon P N. Vinken P. J. and Bruyn G. W. (ed.), Handbook of clinical neurology. Vol. 33. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier/North Holland Biomedical Press; 1978. Tuberculous meningitis (cranial and spinal) pp. 195–262. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vengasarkar U S, Pisipaty R P, Parekh B, Panchal V G, Shetty M N. Intracranial tuberculoma and the CT scan. J Neurosurg. 1986;64:568–574. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.64.4.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma A, Rattan A, Tyagi J S. Development of a 23S rRNA based PCR assay for the detection of mycobacteria. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1994;31:288–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welchman J M. Computerized tomography of intracranial tuberculoma. Clin Radiol. 1979;30:567–573. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(79)80199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]