Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection resolves spontaneously in approximately 25% of acutely infected humans where viral clearance is mediated primarily by virus specific CD8+ T cells. Previous cross-sectional analysis of the CD8+ T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire targeting two immunodominant HCV epitopes reported widespread use of public TCRs shared by different subjects, irrespective of infection outcome. However, little is known about the evolution of the public TCR repertoire during acute HCV and whether cross-reactivity to other antigens can influence infectious outcome. Here, we analyzed the CD8+ TCR repertoire specific to the immunodominant and cross-reactive HLA-A2 restricted NS3-1073 epitope during acute HCV in humans progressing to either spontaneous resolution or chronic infection, and at ~1-year following viral clearance. TCR repertoire diversity was comparable among all groups with preferential usage of the T cells receptor beta V04 and V06 gene families. We identified a set of thirteen public clonotypes in HCV-infected humans independent of infection outcome. Six public clonotypes used the V04 gene family. Several public clonotypes were long-lived in resolvers and expanded upon reinfection. By mining publicly available data, we identified several low frequency CDR3 sequences in the HCV-specific repertoire matching human TCRs specific for other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes from melanoma, cytomegalovirus, influenza A, Epstein-Barr and yellow fever viruses but they were of low frequency and limited cross-reactivity. In conclusion, we identified thirteen new public human CD8+ TCR clonotypes unique to HCV that expanded during acute infection and reinfection. The low frequency of cross-reactive TCRs suggest that they are not major determinants of infectious outcome.

INTRODUCTION

CD8+ T cells recognize antigens presented by class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules via their T cell receptors (TCR), an αβ heterodimer. TCR repertoire diversity is achieved through germline variable (V), diversity (D) and junction (J) gene segments rearrangements and addition or deletion of nucleotides between segments, resulting in a specific CD8+ TCR or clonotype. The TCRAV and TCRBV for the α and β chains, respectively, encodes the complementarity-determining regions 1 and 2 (CDR1 and CDR2), that interact with the MHC molecule (1). Antigen-binding specificity is determined by the most variable region of the TCR, the CDR3 region, formed by the V-J α and V(D)J β junctions. An identical clonotype or CDR3 amino acid (AA) sequence detected in several individuals, termed “public”, was associated with better control of viral infections, including cytomegalovirus (CMV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), while less common or “private” repertoires were not (2–4).

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has two dichotomous outcomes where approximately 25% of acutely infected subjects resolve spontaneously while the rest develop persistent infection. Expansion of HCV-specific CD8+ T cells targeting multiple epitopes (i.e. broad) and producing several cytokines (i.e. polyfunctional) is essential to clear acute primary infection (5–7). Hence, HCV represents a unique opportunity to examine the protective capacity of virus-specific CD8+ T cell public clonotypes. Cross-sectional studies reported the presence of public TCRs recognizing the hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) 398SLASLFTQGA407 epitope of the E2 glycoprotein, and the non-structural 3 (NS3) 1395HSKKKCDEL1403 (HSK) or 1435ATDALMTGY1443 (ATD) HCV epitopes, irrespective of HCV infectious outcome (8, 9). These studies mostly relied on in vitro expansion of antigen-specific T cells prior to analysis that may have favored expansion of certain TCR clonotypes. Furthermore, very limited analysis was performed early during acute infection. Whether other immunodominant HCV epitopes favor the expansion of public clonotypes and whether they correlate with spontaneous resolution of acute infection remains unknown.

The HLA-A2 restricted NS3-1073 1073CINGVCWTV1081 epitope, derived from the highly immunogenic NS3 protein, is one of the immunodominant epitopes during HCV infection (10–12). Spontaneous clearance of acute HCV was associated with an NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cell response (13–15). Long-lived NS3-1073 specific memory CD8+ T cells were detected two decades after HCV spontaneous clearance suggesting it may contribute to long-term protective immunity (10). Indeed, our group has previously demonstrated expansion of memory NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells in HCV resolvers following virus re-exposure and reinfection (5). In individuals who spontaneously resolved their reinfection, we observed focusing of the TCR repertoire with rapid and selective expansion of memory CD8+ T cell clonotypes with the highest functional avidity (16).

CD8+ T cells specific to the HCV NS3-1073 epitope are also known to be cross-reactive to several HLA-A2 restricted epitopes. The first cross-reactivity reported was against the NA-231 epitope of influenza virus (17). Other cross-reactivities were later identified against cytomegalovirus, (CMV; pp65) and Epstein Barr virus, (EBV; LMP2) (17–19). In addition, a pre-existing pool of memory HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells, induced by heterologous infections, was characterized in a cohort of healthy HCV-seronegative subjects (19). These memory HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells influenced the T cell response to HCV peptide vaccine (19). These studies suggested that this cross-reactivity may contribute to enhanced spontaneous clearance or pathogenesis of acute HCV infection.

Here, we characterized and compared the HCV NS3-1073 specific TCR repertoire during the very early acute phase of HCV infection and long-term follow-up in spontaneous resolvers (SR) and during acute infection in subjects who developed chronic infection (CI). Our main objective was to characterize the presence of public clonotypes against this immunodominant epitope and their potential association with spontaneous HCV resolution directly ex-vivo. We identified a common set of public clonotypes independent of infection outcome. While several CDR3 sequences were shared with other non-HCV HLA-A2 restricted epitopes, these potentially cross-reactive clonotypes did not expand during acute HCV infection. The public clonotypes we identified were unique to HCV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Study subjects were recruited among people who inject drugs (PWID) enrolled in the Montreal Hepatitis C Cohort (HEPCO) (20). Subjects were followed every 3 months for HCV infection. Acute HCV primary infection was defined as a positive HCV RNA and/or anti-HCV antibody positive test following a negative test in the past 24 weeks. The estimated date of infection (EDI) was calculated as the median time between last negative and first positive RNA or antibody test. Spontaneous resolution was defined as viral clearance (HCV RNA negative) at ≤ 24 weeks (SR; n=8), and chronic infection was defined as HCV RNA positive at 24 weeks (CI; n=6). For the purpose of this study, two different time points were used: acute (< 24 weeks or 168 days) and follow-up (> 49 weeks or 343 days). Two HCV spontaneously resolved subjects who experienced a documented reinfection episode were recruited within the same cohort where reinfection was defined as a positive HCV-RNA test following two negative tests ≥ 60 days apart. The detailed analysis of their immune response and T cell repertoire analysis were described previously (5, 16). Subjects’ demographics are described in Table 1. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the CRCHUM (Protocol SL05.014).

Table 1.

Study subjects’ characteristics and demographics

| Subject ID | Sex | Time Point studied | Days after EDI | Genotype | Plasma HCV RNA (IU/mL) | NS3-1073 autologous sequenceb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (years) | CINGVCWTVc | |||||||

| SR.1 | F | 36 | Acute | 155 | 1 | <15 | ND | |

| Follow-up | 413 | Undetectable | ND | |||||

| SR.2 | M | 45 | Follow-up | 430 | 1 | Undetectable | ND | |

| SR.3 | M | 42 | Follow-up | Unknowna | N/A | Undetectable | ND | |

| SR.4 | M | 40 | Follow-up | 347 | 1 | Undetectable | ND | |

| SR.5 | F | 22 | Acute | 29 | 1a | 10 397 | ||

| ----A---- (5/6) | ||||||||

| Follow-up | 503 | Undetectable | ND | |||||

| SR.6 | M | 31 | Follow-up | Unknowna | N/A | Undetectable | ND | |

| SR.7 | F | 21 | Acute | 75 | 1 | 4 107 | ||

| R-------- (1/7) | ||||||||

| Follow-up | 389 | Undetectable | ND | |||||

| SR.8 | M | 36 | Acute | 168 | 1a | 16 667 | ||

| --------A (1/5) | ||||||||

| Follow-up | 367 | Undetectable | ND | |||||

| CI.1 | M | 38 | Acute | 77 | 1a | 18 000 | --------- (8/8) | |

| CI.2 | F | 28 | Acute | 68 | 1a | 3 192 | --------- (8/8) | |

| CI.3 | M | 56 | Acute | 91 | 1a | 5 128 614 | --------- (6/6) | |

| CI.4 | M | 48 | Acute | 89 | 1a | 11 487 369 | --------- (8/8) | |

| CI.5 | M | 32 | Acute | 83 | 1a | 2 106 667 | --------- (5/5) | |

| CI.6 | M | 21 | Acute | 46 | 1a | 10 567 | --------- (8/8) | |

| SR/SR-1*‡ | M | 53 | Pre-reinfection | −75 | 1 | Negative | ND | |

| Peak reinfection | 32 | Undetectable | ND | |||||

| Late reinfection | 180 | Undetectable | ND | |||||

| SR/CI-2*‡ | M | 29 | Pre-reinfection | −60 | 1a | Negative | ND | |

| Peak reinfection | 70 | 644 | ----A---- (10/10) | |||||

| Late reinfection | 170 | Positive (ND) | ------L-I (8/8) | |||||

Subject was HCV antibody positive, HCV RNA negative (Resolver) at time of recruitment with no previous infection history

Number of individual molecular clones sequenced

HCV H77 (Genotype 1a) reference sequence

SR/SR-1 and SR-CI-2 data were previously published in Abdel-Hakeem et al. (5)

N/A: Not Available; ND: Not Done

Tetramer staining, flow cytometry and cell sorting

The MHC class I monomer, HLA-A2 bound to the HCV NS3 peptide AA 1073–1081 (CINGVCWTV) [A2/NS3-1073], was synthesized by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility (Emory University, Atlanta, GA). Tetramers were prepared by adding 10 μl of phycoerythrin (PE) labeled ExtrAvidin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) five times, with 10 min incubation at room temperature after each addition. Cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were thawed and CD8+ T cells were negatively selected using the MACS CD8+ T cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec Inc, Auburn, CA). Tetramer staining and cell surface staining were performed on isolated CD8+ T cells as previously described (16). Directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies against the following cell-surface markers were used: CD3–Pacific Blue (clone UCHT1), CD8–Alexa Fluor® 700 (clone RPA-T8) and CD45RO–BB515 (clone UCHL1), all from BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA. The LIVE/DEAD® fixable aqua dead cell Stain Kit (Molecular Probes™ Thermo Fisher Scientific, Burlington, ON) was used to identify live cells. Cell sorting was performed using a BD Aria II cell sorter equipped with blue (488 nm), red (633 nm), and violet (405 nm) lasers (BD Biosciences) while multiparameter flow cytometry was performed using a BD LSRII instrument with the same setup and an additional yellow-green laser (561 nm) using FACSDiva software version 6.1.3 (BD Biosciences) at the CRCHUM flow cytometry core. Data files were analyzed using FlowJo software version 10.4.11 (BD Biosciences).

TCR Vβ-chain sequencing and analysis

FACS-sorted HCV-specific CD8+ T cells from each subject were sent to Adaptive Biotechnologies (Seattle, WA) for genomic DNA extraction followed by TCRβ sequencing, as previously described (16). Data analysis were performed using ImmunoSEQ™ Analyzer software (v3.0) and R v3.5.1. All TCR repertoires were cleaned to remove sequences with a stop codon and those that are out of frame. The number of FACS-sorted CD8+ T cells, total and unique productive sequences, and clonality for each sample are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. Diversity indices (Simpson diversity, Shannon entropy, CDR3 length and NT additions) were provided by Adaptive Biotechnologies.

HCV NS3-1073 HCV epitope sequencing

HCV RNA was extracted from 500 μL of plasma EDTA samples using QIAamp MinElute Virus spin kit (Qiagen, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol. As previously described (21), purified viral RNA was reverse transcribed, PCR amplified, cloned and sequenced at the McGill University and Genome Quebec Innovation Centre (Montréal, QC).

VDJ database and computational analysis

We extracted HLA-A2 restricted antigen-specific TCR sequences from the VDJ database [https://vdjdb.cdr3.net/]. Using R [https://www.R-project.org/] (22), we identified exact CDR3 AA sequence matches within this database (23) and our HCV NS3-1073 TCR repertoire dataset. Frequencies of identified CDR3 AA sequences in a particular subject’s repertoire were summed up to quantify the percentage of clonotypes identical to other epitope(s) specific TCR repertoire.

Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay

Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays were performed using 2×105 cryopreserved PBMCs, as previously described (24). The following peptides were used for this assay: HCV (NS3; CINGVCWTV), Flu (NA; CVNGSCFTV), CMV (pp65; NLVPMVATV), EBV (BMLF1; GLCTLVAML), Flu (M1; GILGFVFTL), YFV (NS4B; LLWNGPMAV), Melanoma (MLANA; ELAGIGILTV). The HCV NS3-1073 peptide was synthesized by the Sheldon Biotechnology Centre (McGill University, Montréal, QC). The Flu NA-231 peptide was synthesized by JPT Peptide Technologies (Berlin, Germany), while the other four were synthesized by ProImmune (Sarasota, FL).

Expansion of HCV-specific CD8+ T cells, peptide stimulation and intracellular staining (ICS)

HCV-specific CD8+ T cells were expanded as previously described (25). Briefly, freshly thawed PBMCs were seeded in a 48-wells plate at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells per well, in R10 (RPMI 1640 + 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies) supplemented with penicillin + streptomycin (pen/strep, 1X, Wisent) and 14 mM HEPES (Wisent) (R10-P/S-HEPES). Cells were stimulated with 10 μg/ml HCV NS3 peptide (NS3-1073-1081; CINGVCWTV) for 2 weeks at 37 °C. Half of the medium was replenished every 3 days with R10-P/S-HEPES supplemented with 40U/ml rIL-2 (NIH-AIDS Reagents Program) (R10-P/S-Hepes-IL-2, first rIL-2 addition on day 3). Expanded HCV-specific CD8+ T cells were then cryopreserved in freeze mix (FBS + 10% DMSO) at a concentration of 107 cells/ml. Thawed cells were re-stimulated in a 48-wells plate at a concentration of 106 cells per well in presence of 2 × 106 non-autologous irradiated (30 Gy) feeder cells and 0.01μg/ml anti-CD3 (Beckman Coulter), in R10-P/S-IL-2. Half of the media was replenished every 3 days with R10-P/S-IL-2. After 2 weeks, autologous EBV transformed B cell line (BLCLs), suspended in R-10 medium, were irradiated at 100 Gy and prepulsed with either no peptide, 15 μg/ml of HCV NS3 peptide (NS3-1073-1081; CINGVCWTV), Flu peptide (NA-231-239; CVNGSCFTV) or CMV peptide (pp65-495; NLVPMVATV) for 1 h at 37 °C. BLCLs were then washed and incubated with HCV-specific T cells at a ratio of 10:1 (T cell: BLCLs) for 6 hours in AIM-V medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% human serum (Wisent) and anti-CD107a-BUV395 antibody (clone H4A3; BD Bioscience). After 1 hour of stimulation, 10 μg/ml Brefeldin A (BFA, Sigma) and 6 μg/ml monensin (Sigma) were added to each well. At the end of the stimulation, cells were washed using FACS buffer (PBS, 1% FCS) and surface staining was performed using the following directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies: CD3–Pacific Blue (clone UCHT1), CD4-BV605 (clone RPA-T4), and CD8-APC-H7 (clone SK1) and live cells were identified as described above. Cells were then permeabilized with CytoFix/CytoPerm (BD Biosciences) for 15 minutes at 4°C in the dark, washed using Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences), then incubated for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark with anti-IFNγ-PE-Cy7 (clone B27), anti-TNF-α-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone MAb11) and anti-IL-2-APC (clone MQ1-17H12) (All from BD Biosciences). Cells were then washed and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Sigma Aldrich) in PBS and analyzed by FACS as described above. Boolean gating and SPICE software were used for polyfunctionality analysis (26).

Data availability

Raw data of all TCR sequences are available at https://clients.adaptivebiotech.com/pub/mazouz-2021-ji (DOI:10.21417/SM2021JI).

RESULTS

Comparable HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire diversity regardless of HCV infection outcome

We analyzed the TCR repertoire of FACS-sorted MHC class I tetramer reactive CD8+ T cells specific for the immunodominant HLA-A*0201 restricted NS3-1073 epitope in HCV infected subjects (n=14). Our cohort included samples collected during acute HCV infection (≤168 days post estimated day of infection (EDI)) from either spontaneous resolvers (SR-Acute; n=4) or subjects who developed a chronic infection (CI-Acute; n=6), as well as samples at a follow-up time point (≥ 347 days post EDI) following HCV clearance in the SR group (SR-Follow-up; n=8) (Table 1). Four SR subjects had paired samples at both the acute and follow-up time points. Because the frequencies of NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells are dramatically reduced with progression towards chronic infection, we could not sort and analyze the repertoire of NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells in CI subjects at follow-up. The frequencies of HLA-A2/NS3-1073 tetramer+ CD8+ T cells were not significantly different between groups (Figure 1A, Supplementary Table S1). In addition, we sorted and sequenced the TCR repertoire of total naïve CD45RO−CD8+ T cells from two samples: SR.5-Acute and CI.5-Acute as controls for each group. TCR deep-sequencing information including number of sorted cells, productive total/unique sequences and clonality are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1. Comparable NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire diversity in SR-Acute, SR-Follow-up and CI-Acute samples.

Analysis of the TCRβ repertoire of HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells sorted from the peripheral blood of SR subjects during either acute HCV (SR-Acute; n=4) or follow-up (SR-Follow-up; n=8) and CI subjects during acute HCV (CI-Acute; n=6). Subjects clinical characteristics, demographics and time points tested are indicated in Table 1. (A) Frequencies of HLA-A2/NS3-1073 tetramer+CD8+ T cells in the indicated samples. (B) Simpson Diversity and (C) Shannon Entropy of all the specific repertoires in the analyzed samples. (D) Tree maps show each sample’s TCR repertoire. Each colored square represents a CDR3 clonotype and its proportion within the entire TCR repertoire. Clonotypes in common between paired samples (e.g. SR1-Acute and SR1-Follow-up) are represented using the same color. Apart from paired samples, colors were randomly chosen. Graphs below each tree maps show the individual CDR3 clonotype frequency (left y axis) and the Cumulative frequency (grey circles and line graph) of the top 10 expanded clonotypes (right y axis). (E) Cumulative frequencies of the top 10 clonotypes.

We compared the diversity of the repertoire in SR-Acute, SR-Follow-up and CI-Acute samples using the Simpson diversity index which integrates the number of clonotypes as well as their abundance (27) and ranges from 0 (high diversity, i.e. large repertoire) to 1 (low diversity, i.e. narrow repertoire) (Figure 1B). We also examined the Shannon diversity which integrates both the abundance and evenness (i.e. similarity of frequencies) of all clonotypes (28) and ranges from 0 (low diversity) to 1 (high diversity) (Figure 1C). Both analyses demonstrated high diversity in all groups but no significant differences between groups (Figures 1B and 1C). As shown by tree maps, the majority of samples displayed a broad TCR repertoire, with the top 10 sequences representing less than 25% of the total TCR repertoire in most samples (3/4 SR-Acute, 7/8 SR-Follow-up, 4/6 CI-Acute) (Figure 1D). Only three samples (SR.1-Acute, SR.1-Follow-up and CI.1-Acute) were more focused with the top 10 sequences representing 55.8%, 43.5% and 56.3% of their NS3-1073 specific TCR repertoire, respectively (Figure 1D). Altogether, the accumulated frequencies of the top 10 TCR clonotypes showed no significant differences between the three groups (Figure 1E).

Next, we assessed the CDR3 AA length distribution. The naïve CD45RO−CD8+ TCR repertoires from SR.5-Acute and CI.5-Acute displayed a normal Gaussian distribution indicated by a coefficient of determination (R2) close to 1 (Supplementary Figure S1A, right). In contrast, the HCV NS3-1073 specific TCR repertoires were more skewed (R2 ranged from 0.6 to 0.96) in all samples suggesting antigen-specific clonotypic expansion (Supplementary Figures S1A, left). The CDR3 lengths were skewed but no particular AA length was preferentially overrepresented (Supplementary Figures S1A, left). There were no significant differences in the CDR3 AA length distribution between SR-Acute, SR-Follow-up and CI-Acute (represented as R2, Supplementary Figure S1B).

Altogether, these data suggest that SR-Acute, SR-Follow-up and CI-Acute samples had similar highly diverse HCV NS3-1073 specific TCR repertoire.

TCRB V04 and V06 gene families are preferentially utilized in all groups

To further characterize the HCV NS3-1073 specific TCR repertoire, we analyzed and compared the V gene usage between all groups. As we previously described (16), we stratified clonotypes at the nucleotide level into four distinct categories according to their abundance within the total repertoire analyzed in each subject: Dominant (frequencies ≥1%); sub-dominant (≥0.5%); low abundance (≥0.1%); and lowest abundance clonotypes (<0.1%). Hereinafter, all HCV NS3-1073 specific TCR repertoire results presented will focus on dominant, sub-dominant and low abundance clonotypes only. The detailed raw TCR sequencing data for each subject are available online as described in Material and Methods. Using a threshold frequency of ≥10%, the most frequently used V gene families were V02 to V07 and V09, irrespective of HCV infection outcome. Figure 2A shows V02 to V09 families, while all families are shown in Supplementary Figure S2A. V04 and V06 were the two TCRB V gene families preferentially used in all groups. Also, V04 was significantly more utilized as compared to V06 (p ≤ 0.05) at the follow-up time-point in SR (Figure 2A). By examining paired naïve and acute samples from SR.5 and CI.5, we observed that the preferential usage of V04 and V06 was not associated with their overrepresentation within the naïve pool (Supplementary Figure S2B). V02 was significantly enriched in CI-Acute as compared to SR-Follow-up (p≤ 0.05) but this was mainly driven by one outlier. Similarly, V09 was significantly enriched in SR-Acute as compared to SR-Follow-up (p ≤ 0.01) and CI-Acute (p ≤ 0.001) samples due to another outlier.

Figure 2. TCRB V04 and V06 V gene families are preferentially utilized by HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells from all groups.

(A) Frequency of preferentially used TCRBV families among dominant (≥ 1%), sub-dominant (≥ 0.5%) and low abundance clonotypes (≥ 0.1%) in SR samples collected during acute (n=4) and follow-up (n=8) and CI-acute samples (n=6) (Two-way ANOVA; *: p ≤ 0.05; **: p ≤ 0.01; ****: p ≤ 0.0001). In this figure, we are only showing V gene families of frequencies ≥10% and highlighting only key TCRBV families that are significant as compared to at least three other families. For the full representation, see Supplementary Figure S2. (B) Evolution of J and corresponding V genes usage in paired samples from four SR subjects at the acute and follow-up time points, shown as chord diagrams representing frequencies of dominant, sub-dominant and low frequency clonotypes (EDI.: Estimated day post-infection.). The size of the colored arcs is proportional to V genes frequencies and the corresponding V-J pair. (C) Cumulative frequencies of V04 and (D) V06 usage within dominant, sub-dominant and low frequency clonotypes in paired samples collected from SR subjects during acute and follow-up time points (Student t-test; ns: not significant).

Next, we examined whether preferential usage of these V genes was sustained after resolution of acute HCV infection. We compared the TCR repertoire of paired samples from four SR subjects during acute infection and at a follow-up time point at > 49 weeks after HCV infection (range 367 to 503 days post EDI). The V gene family usage profiles remained comparable at follow-up (Figure 2B). The V04 and V06 remained within the top four preferentially utilized families by all subjects (Figures 2B, 2C and 2D). Altogether, these data demonstrate preferential V04 and V06 usage in all groups during acute infection. This preferential usage was sustained at follow-up in SR subjects.

Expansion of thirteen HCV NS3-1073 specific public clonotypes irrespective of acute infection outcome and their longevity post spontaneous clearance

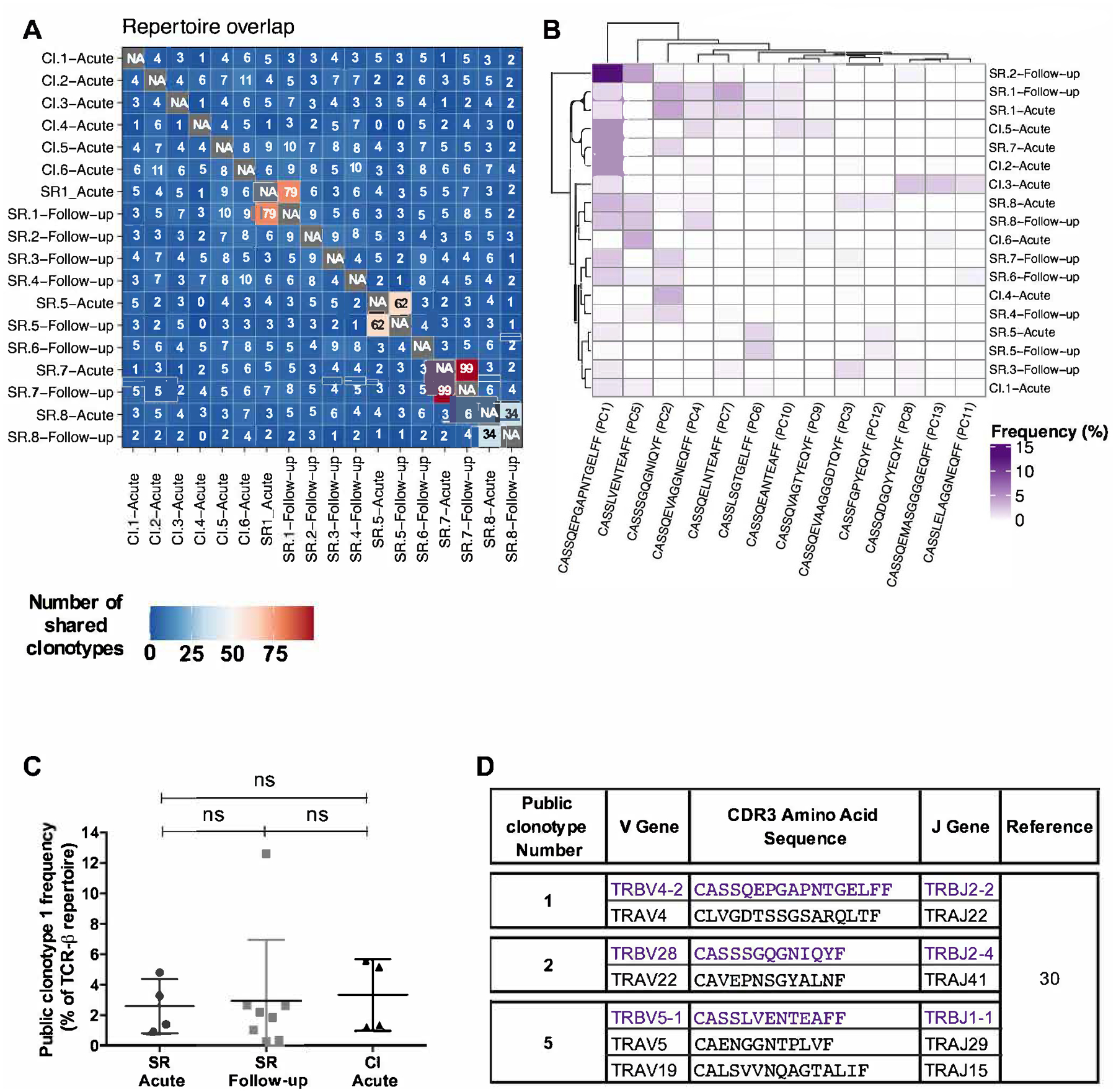

Next, we performed an in-depth analysis of all CDR3 sequences within the repertoire to identify public TCR clonotypes (CDR3 AA sequence) that are present in multiple individuals (reviewed in (29)). First, we sought to identify the number of common identical CDR3 sequences in all potential pairwise combinations among dominant, sub-dominant and low abundance clonotypes (Figure 3A). As expected, the highest number of shared clonotypes were between samples belonging to the same subject at two different time-points (e.g. SR.1- Acute and SR.1-Follow-up). On the other hand, CI.4-Acute did not share any clonotypes with SR.5-Acute, SR.5-Follow-up and SR.8-Follow-up. All other pairwise comparisons revealed the presence of 1 to 11 identical CDR3 sequences (Figure 3A). To refine our analyses, a given clonotype was designated as “public” if it was present in at least two subjects at a cumulative frequency of ≥0.5%, irrespective of infection outcome. Using these criteria, we identified a set of thirteen public clonotypes (Figure 3B, Supplementary Table S2). These public clonotypes and their cumulative frequencies in each sample are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. Six public clonotypes (1, 3, 4, 7, 10 and 13) utilized the V04 gene family. Two of them (public clonotypes 7 and 10) were highly related as they were both 13 AA long with only one AA difference (Supplementary Table S2). These public clonotypes did not segregate samples by group, underscoring that their expansion was independent of infection outcome (Figure 3B). One public TCR clonotype (CASSQEPGAPNTGELFF (V04-02/J02-02)), hereinafter termed public clonotype 1, was detected in most samples (12/14) (Figure 3B). The cumulative frequencies of this public clonotype were not significantly different between all groups (Figure 3C). Other public clonotypes were detected in fewer subjects and at lower frequencies. Public clonotypes 2, 7, 10, 11 and 12 were primarily detected in resolvers while public clonotype 13 was detected only in chronics. Public clonotype 1 was long-lived and detectable at the follow-up time point in subjects SR.1, SR.5, SR.7 and SR.8 at a frequency of 0.28–2.65% at 1–2 years post infection (Figure 3B, Supplementary Table S2). Other public clonotypes that were present during the acute phase at a frequency of >1% were also maintained at a high frequency at the follow-up time point. Altogether, these results suggest that HCV infection can prime the expansion of several public clonotypes. Several of these public clonotypes including the dominant public clonotype 1 were long-lived and detectable in resolvers post HCV clearance.

Figure 3. Identification of a set of HCV-specific public clonotypes irrespective of infection outcome.

(A) The number of common CDR3 AA sequence among dominant (≥1%), sub-dominant (0.50–0.99%) and low abundance (0.49–0.10%) clonotypes of HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells in analyzed samples represented as a heatmap. A clonotype was termed “public” if it was present in at least two subjects at a cumulative frequency ≥0.5%, irrespective of infection outcome. (B) Heatmap showing the cumulative frequencies of the CDR3 AA sequence of the thirteen identified public clonotypes within dominant, sub-dominant and low abundance clonotypes. (C) Cumulative frequencies of public clonotype 1 within dominant, sub-dominant and low abundance clonotypes in SR samples collected during acute (n=4) and follow-up (n=8) and CI-acute samples (n=6) (One-way ANOVA; ns: not significant). (D) Corresponding alpha chain AA sequences of public clonotypes 1, 2 and 3 extracted from the study by Eltahla et al (30).

The TCR-alpha chain is an important determinant of the functionality of a public clonotype. However, it is technically challenging to identify the TCRαβ paired sequences from bulk sequencing data. To gain an insight about the TCRαβ pairing of the identified public clonotypes, we examined publicly available data. Eltahla et al. examined paired TCRαβ sequences via single cell RNA-seq of NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells from one subject who had spontaneously resolved primary HCV infection (30). Three of the public clonotypes we identified, including the dominant public clonotype 1, and public clonotypes 2 and 5, were also detected by Eltahla et al. together with their corresponding TCRα sequences (Figure 3D). These data confirm the presence of these public clonotypes in another unrelated study subject and potential paired TCRα sequences. However, additional studies are required to clone and analyze the impact of the different TCRα chain sequences on the functionality of these public clonotypes

Expansion of HCV NS3-1073 specific public clonotypes is independent of autologous virus sequence

To assess whether the preferential expansion of certain public clonotypes was associated with a specific viral variant, we sequenced the region spanning the NS3-1073 epitope in autologous virus isolated from the plasma of subjects who had high viral loads that were high enough to sequence (n=9, Table 1). Compared to the epitope reference sequence (CINGVCWTV), we did not detect any sequence variation in the autologous virus in the CI group. However, we detected variant viral sequences in three of the sequences SR-Acute samples (SR.5, SR.7 and SR.8). All three subjects exhibited an expansion of public clonotype 1. Furthermore, the viral variants were not the same in all subjects, suggesting that a particular HCV NS3-1073 viral sequence is not the main driver of expansion of this public clonotype and that this public clonotype may have the flexibility to recognize multiple variants of the same epitope.

Limited overlap between public clonotypes and HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells from seronegative subjects

Next, we sought to examine whether the dominant public clonotypes we detected were enriched due to a pre-existing pool of cross-reactive memory CD8+ T cells prior to HCV infection. Zhang et al had previously reported the presence of naïve and memory HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells in HCV seronegative subjects (19) suggesting that these T cells might, in part, be primed by previous heterologous infections. We searched for exact matches between the data from Zhang et al and ours. We identified four TCR clonotypes from our data set that were also present in seronegative subjects. These four clonotypes contained only one public clonotype (public clonotype 4) while the other three clonotypes did not meet our public clonotype criteria (Table 2). These results suggest that the public clonotypes detected in our study are unlikely to have originated from a memory pool of cross-reactive CD8+ T cells.

Table 2.

Overlap between NS3-1073 specific clonotypes from seronegative subjectsa and our dataset

| Public Clonotype Number | CDR3 Amino Acid Sequence | Subject ID | Acute | Follow-Up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V Gene | Frequency (%) | Total | V Gene | Frequency (%) | Total | |||

| 4 | CASSQEVAGGNEQFF | SR.1 | V04-02 | 1.17 | 1.35 | V04-02 | 1.70 | 1.83 |

| V04-03 | 0.18 | V04-03 | 0.13 | |||||

| SR.7 | V04-03 | 0 | 0 | V04-03 | 0.20 | 0.20 | ||

| SR.8 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 1.77 | 1.77 | ||||

| CI.2 | V04-02 | 0.51 | 0.51 | ND | ||||

| CI.3 | 0.12 | 0.12 | ND | |||||

| CI.5 | V03 | 1.70 | 1.70 | ND | ||||

| N/A | CASSPLGSSYEQYF | SR.3 | ND | V27-01 | 0.13 | 0.13 | ||

| CASSLAGQAYEQYF | SR.7 | V27-01 | 0.19 | 0.19 | V27-01 | 0.20 | 0.20 | |

| CASSEDGMNTEAFF | SR.8 | V10-02 | 0.19 | 0.19 | V10-02 | 0 | 0 | |

Expansion of NS3-1073 specific public clonotypes during HCV reinfection and spontaneous clearance

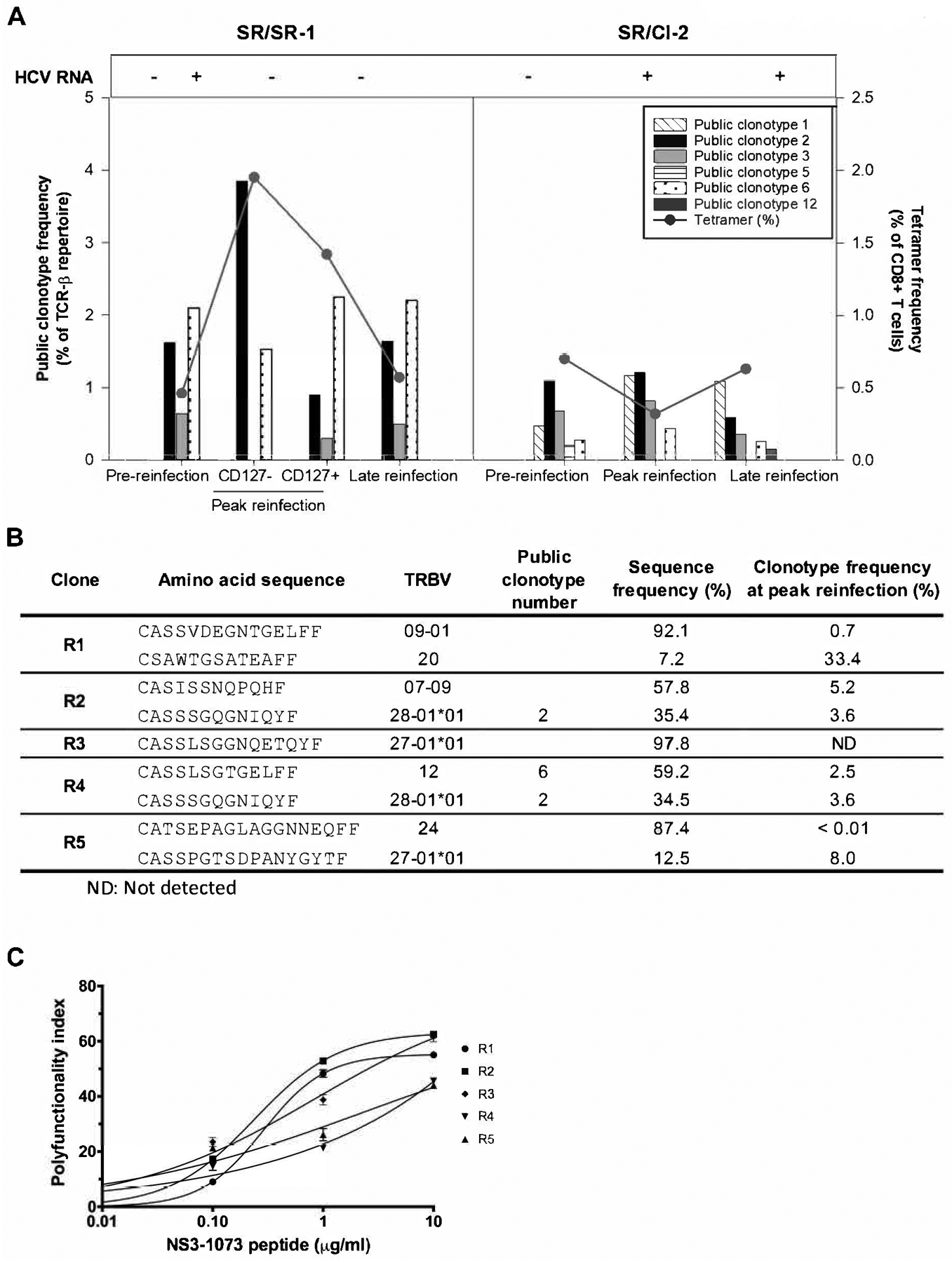

Next, we examined whether the public clonotypes that we identified and were long-lived, would preferentially expand following HCV re-exposure and reinfection. We had previously published a longitudinal analysis of the HCV NS3-1073 specific TCR repertoires from two HCV resolvers with a documented HCV reinfection episode where one spontaneously cleared (SR/SR-1) while the other became persistently infected (SR/CI-2) (16). This divergent outcome was associated with different levels of expansion of HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells in each subject (Figure 4A). In subject SR/SR-1, NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells expanded from 0.46% to 3.37% during peak reinfection (3 weeks post detection of reinfection) where ~58% of tetramer+ cells exhibited a CD127− effector phenotype. The frequency then stabilized at 0.57% at late reinfection (24 weeks). In subject SR/CI-2, NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells were at 0.70% at pre-reinfection, decreased to 0.32% during peak reinfection (week 4) and then stabilized at 0.63% at late reinfection (week 24). Autologous virus sequencing in SR/CI-2 revealed a variant of the NS3-1073 epitope (Table 1) that was not recognized by the pre-existing memory CD8+ T cells which may explain the limited expansion of the NS3-1073 population in that subject. (5).

Figure 4. Expansion profile and polyfunctionality of public clonotypes during HCV reinfection.

(A) Cumulative frequencies of public clonotypes within dominant, sub-dominant and low abundance clonotypes during HCV reinfection in subject SR/SR-1 who resolved spontaneously and subject SR/CI-2 who developed chronic infection. The TCR repertoire was examined at pre-reinfection, peak reinfection and late reinfection time points, as previously described by Abdel-Hakeem, Boisvert et al. (16). Subject SR/SR-1 tested HCV RNA positive at only one time point between pre-reinfection and peak reinfection. Effector (CD127−) and memory (CD127+) CD8+ T cell subsets were examined at the peak reinfection time point in subject SR/SR-1. (B) TCR deep sequencing of five CD8+ T cell clones derived from the peripheral blood of subject SR/SR1 showing the presence of public clonotypes 2 and 6. (C) One representative experiment in duplicate showing polyfunctionality indices of the CD8+ T cell clones described in B (data reproduced from Abdel-Hakeem, Boisvert et al. (16)).

Within the NS3-1073 specific FACS-sorted CD8+ T cells, public clonotype 1 was only detected in subject SR/CI-2. Although, the overall tetramer frequency did not increase, this public clonotype expanded 2.49 folds at peak reinfection and remained within the dominant pool at late reinfection (Figure 4A). Public clonotypes 2, 3 and 6 were present in both subjects. Public clonotype 2 was detectable at pre-reinfection at a frequency of 1.62% and 1.10% of the repertoire in SR/SR-1 and SR/CI-2, respectively. at peak reinfection, it expanded only in SR/SR-1 to 3.85% of the effector (CD127−) and 0.90% of the memory (CD127+) CD8+ T cells repertoire. Public clonotype 3 slightly expanded (1.2 folds) in SR/CI-2 subject. Public clonotype 6 was detectable at pre-reinfection at a higher frequency in SR/SR-1 (2.10%) as compared to SR/CI-2 (0.28%). It expanded to 2.25% of memory CD127+ T cells and to 1.53% of effector CD127− T cells in SR/SR-1. It also expanded 1.57 folds in SR/CI-2. Public clonotypes 5 and 12 were only detectable in SR/CI-2 and were at low frequencies (≤0.21%) at either pre-reinfection or late reinfection, respectively, and therefore are unlikely to have played a key role during reinfection (Figure 4A).

We had previously established T cell clones from SR/SR-1 (clones R1 to R5) (16), so we examined them for the presence of the public clonotypes identified in this study. Two clones had public clonotypes, clone R2 carried public clonotype 2, and clone R4 carried a mix of public clonotypes 2 and 6 (Figure 4B). These T cell clones also displayed high functional avidity (16) and polyfunctionality indices (Figure 4C). In summary, these data suggest that pre-existing public clonotypes of NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells can expand upon HCV re-exposure and reinfection, are polyfunctional, and may contribute to viral clearance.

Shared clonotypes between HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells and CD8+ T cells recognizing other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes

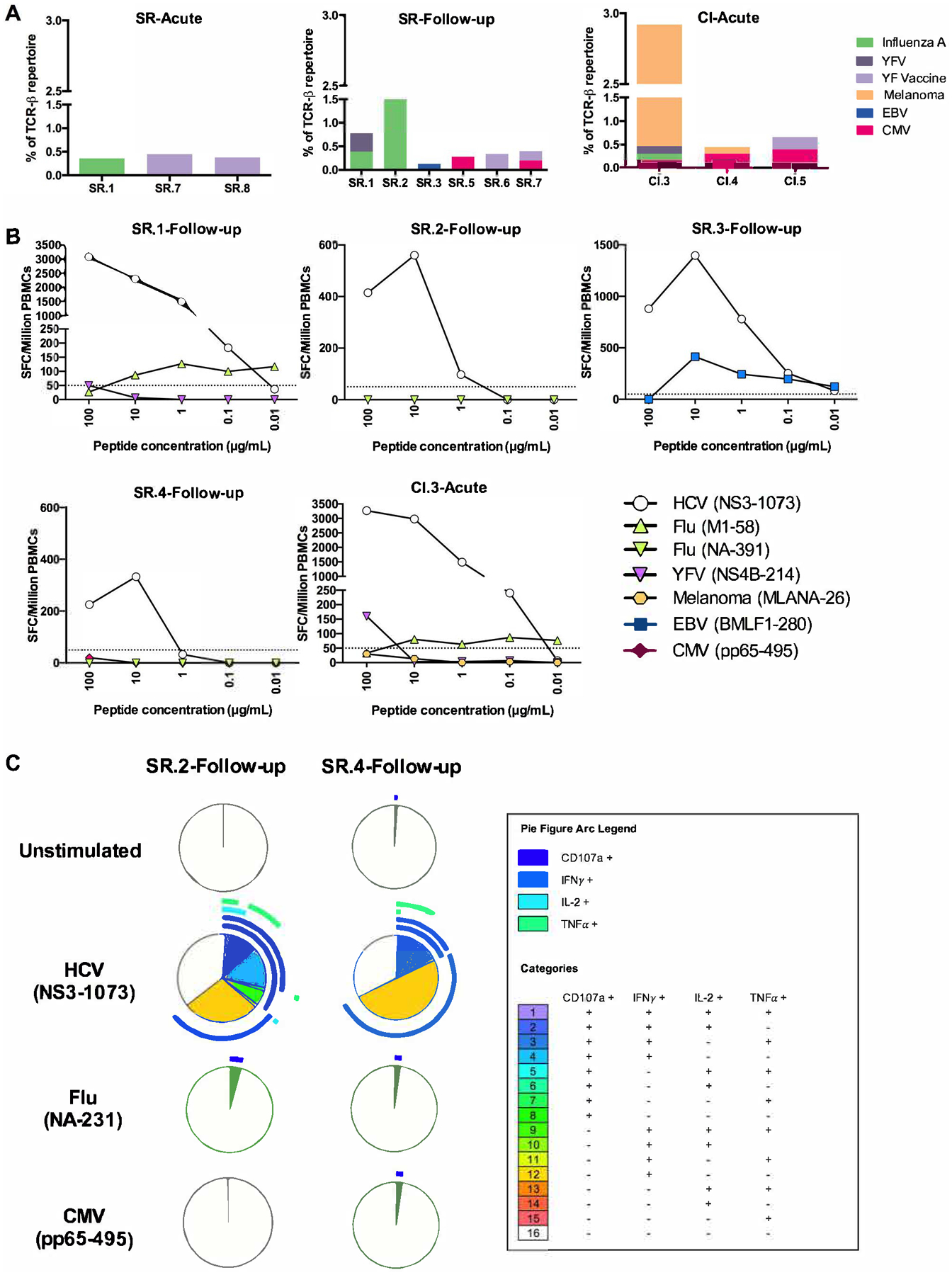

Previous studies reported that HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells can be cross-reactive and can recognize HLA-A2 restricted epitopes from other viruses including influenza (NA-231), cytomegalovirus, (CMV; pp65), and Epstein-Barr virus, (EBV; LMP2) (17–19). However, these studies did not examine the TCR repertoires of cross-reactive T cells and it is unknown whether the same clonotypes/public TCRs are expanded during these different viral infections. Thus, we sought to identify HCV NS3-1073 specific clonotypes that are common with T cell repertoires specific for other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes and that may be cross-reactive. Using the online VDJ database developed by Shugay et al. (23) and CDR3 sequences from a study of the TCR repertoire following yellow fever virus (YFV) vaccination by Pogorelyy et al. (31), we searched for exact matches between TCR clonotypes identified in our study and known clonotypes specific to various HLA-A2-restricted epitopes. The resulting list of shared CDR3 AA sequences, their cumulative frequencies in each subject and the cognate epitope(s) are presented in Table 3 and Figure 5A. Shared CDR3 AA sequences were found in three SR-Acute, six SR-Follow-up and three CI-Acute samples. These shared clonotypes were specific to different antigens including: pp65 (CMV) (32), BMLF1 (EBV) (33), M1 (influenza) (32), NS4B (yellow fever virus, YFV) (34) and MLANA (Melanoma) (35) (Table 3, Figure 5A). However, these clonotypes represented only minor fractions of the repertoire of HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells. The lowest frequency was 0.19% for YFV vaccine TCR in SR.7-Acute while the highest was MLANA (Melanoma) at a frequency of 2.45% in CI.3-Acute (Table 3, Figure 5A).

Table 3.

List of NS3-1073 specific clonotype shared with other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes

| Subject ID | CDR3 Amino Acid Sequence | Acute | Follow-up | VDJ Database (23) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V Gene | Frequency (%) | Total | V Gene | Frequency (%) | Total | Origin | Protein | Epitope | Reference | ||

| SR.5 | CASSLAPGATNEKLFF | V07-06 | 0 | 0 | V07-06 | 0.28 | 0.28 | CMV | pp65 | NLVPMVATV | 32 |

| SR.7 | CASSSDNEQFF | V03 | 0 | 0 | V03 | 0.20 | 0.20 | ||||

| CI.3 | CASSLASSTEAFF | V05-08 | 0.17 | 0.17 | ND | ||||||

| CI.4 | CASSLVNEQFF | V13-01 | 0.15 | 0.15 | ND | ||||||

| CI.4 | CASSLLVAGVYEQYF | V07-09 | 0.15 | 0.15 | ND | ||||||

| CI.5 | CASSLGLYEQYF | V07-09 | 0.40 | 0.40 | ND | ||||||

| SR.3 | CASSVGNEQFF | ND | V09-01 | 0.13 | 0.13 | EBV | BMLF1 | GLCTLVAML | 33 | ||

| SR.1 | CASSQVQGTYEQYF | V03 | 0.36 | 0.36 | V03 | 0.39 | 0.39 | Influenza A | M1 | GILGFVFTL | 32 |

| SR.2 | ND | 1.50 | 1.50 | ||||||||

| CI.3 | V03 | 0.13 | 0.13 | ND | |||||||

| SR.1 | CASSQGQANEKLFF | V04-02 | 0 | 0 | V04-02 | 0.39 | 0.39 | Yellow Fever Virus | NS4B | LLWNGPMAV | 34 |

| CI.3 | 0.17 | 0.17 | ND | ||||||||

| SR.6 | CASSLVAESSYEQYF | ND | V05 | 0.17 | 0.34 | Yellow Fever Virus Vaccine | 31 | ||||

| V05-06 | 0.17 | ||||||||||

| SR.7 | CASSRAGGDYEQYF | V28-01 | 0.19 | 0.19 | V28-01 | 0.20 | 0.20 | ||||

| SR.8 | CASSPNNEQFF | V07-06 | 0.19 | 0.19 | V07-06 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| SR.8 | CASSTNTDTQYF | V11-01 | 0.19 | 0.19 | V11-01 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| SR.7 | CASGQGSYEQYF | V12 | 0.26 | 0.26 | V12 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| CI.5 | 0.26 | 0.26 | ND | ||||||||

| CI.3 | CASTLGGGTEAFF | V05-06 | 2.45 | 2.45 | ND | Homosapiens (Melanoma) | MLANA | ELAGIGILTV | 35 | ||

| CI.4 | CASSLSGQGYEQYF | V27-01 | 0.15 | 0.15 | ND | ||||||

ND: Not Done

Figure 5. Limited recognition of HLA-A2 restricted epitopes by HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells.

(A) Frequencies and predicted specificities of TCR clonotypes of HCV-specific CD8+ T cells from the indicated HCV infected samples shared with other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes from the VDJ database. (B) PBMCs from four SR-follow-up samples were tested in a dose-response IFN-γ ELISPOT assay against the cognate HCV (NS3-1073) epitope and the potentially cross reactive HLA-A2 restricted epitope(s) based on the shared TCR clonotypes represented in (A) and Table 3. These included: Flu (NA-231 and M1-58), YFV (NS4B-214), Melanoma (MLANA-26), EBV (BMLF1-280) and CMV (pp65-495) peptides. The frequencies of IFN-γ spot forming cell (SFC) per million PBMCs are shown for each sample. (C) HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells were expanded from the PBMCs of subjects SR.2 and SR.4 (at the Follow-up time point) with the NS3-1073 peptide as indicated in Materials and Methods. Expanded HCV-specific CD8+ T cell lines were stimulated for 6 hrs with autologous EBV-transformed B cell lines prepulsed or not with either HCV (NS3 1073), Flu (NA-231) or CMV (pp65-495) peptides. Functionality was examined by flowcytometry as indicated in Materials and Methods. Boolean gating and SPICE software were used to assess polyfunctionality profiles of total CD8+ T cells in each sample.

The majority of the identified clonotypes were private (present in only one subject). Only one clonotype previously reported to be reactive to the M1 epitope (Influenza) (CASSQVQGTYEQYF) (32) was detected in three subjects, but the frequencies were below 0.5% in two of these subjects, therefore not meeting our criteria for designation as a public clonotype (Table 3). Interestingly, none of the HCV NS3-1073 public clonotypes (Supplementary Table S2) were shared with other HLA-A2 restricted antigens suggesting that these public clonotypes are unique to HCV. Overall, despite the multiple shared clonotypes identified, they represented only a minor fraction of HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells repertoires (generally < 1%) and they were thus unlikely to have contributed to viral clearance.

Limited recognition of HLA-A2 restricted epitopes by HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells

Next, we assessed the in vitro cross-reactivity of HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells with other viral antigens. We selected three resolver follow-up samples from subjects SR.1, SR.2 and SR.3 and one chronic acute (CI.3-Acute) sample because they expressed TCR clonotypes shared with other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes (Figure 5A). SR.4-Follow-up sample was used as a control since it did not contain any shared clonotypes. We used a dose-response IFNγ ELISPOT assay to compare directly ex vivo, the reactivity of PBMC samples against the HCV NS3-1073 epitope and the other potentially cross-reactive epitopes based on the shared TCR repertoire of each subject as depicted in Figure 5A and Table 3. We also examined the response against the Flu NA-231 epitope known to be cross-reactive with HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells (17, 19). All samples tested, showed a strong response to HCV NS3-1073 and limited responses to the other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes (Figure 5B).

To test whether any responses were missed because of low frequencies of cross-reactive CD8+ T cells, we expanded NS3-1073-specific CD8+ T cells in vitro by stimulation with the cognate peptide for 14 days as described in Materials and Methods. We then tested the polyfunctionality of these expanded cells by intracellular cytokine staining following stimulation with NS3-1073, CMV (pp65) or Flu (NA-231) and evaluated the production of IFNγ, TNFα, IL-2 and the degranulation marker CD107a (Figure 5C). We selected two samples, SR.2-Follow-up and SR.4-follow-up because they had high frequencies of NS3-1073 tetramer+ CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Table S1). They also exhibited different levels of V04 gene usage (21.57% versus 15.9%) and public clonotype 1 (6.86% versus 0.47%). Although SR.4-Acute expressed more IFNγ at the individual cytokine level, SR.2-Acute displayed a higher frequency of CD8+ T cells producing more than one effector function (Figure 5C). In contrast, very limited responses were detected following stimulation with pp65 (CMV) or NA-231 (Flu) where only low levels of CD107a were detected (Figure 5C).

In summary, these results demonstrate that HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells share a very limited number of clonotypes with other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes and consequently exhibit low cross-reactivity suggesting that they were not primed by other pathogens prior to HCV infection.

DISCUSSION

We characterized and tracked directly ex-vivo, the TCR repertoire of the HCV-1073 specific CD8+ T cells during acute HCV in spontaneous resolvers and subjects progressing to chronic infection, as well as at ~1 year post HCV resolution in resolvers. TCR repertoires responding to the conserved NS3-1073 epitope were highly diverse with preferential usage of the TCRB V04 and V06 families regardless of infection outcome. We identified thirteen public clonotypes unique to HCV that were shared across several subjects. Several of these public clonotypes were long-lived in resolvers and re-expanded upon reinfection. In addition, we identified a set of TCR clonotypes shared with other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes suggesting potential cross-reactivity. However, these clonotypes were of low frequency and demonstrated limited cross-reactivity in in vitro assays and are thus unlikely to have played a major role in determining the outcome of primary acute HCV infection.

We demonstrated that the HCV NS3-1073 specific TCRβ repertoire was diverse during early acute infection irrespective of infection outcome and that this diversity persisted at long-term follow-up. Several studies demonstrated that a diverse CD8+ TCR repertoire is important in recognizing escape mutations in targeted epitopes that may arise during HIV or HCV infections (36–39). These studies suggested that having a more diverse repertoire early during acute infection allows refined selection of the most effective clonotype against the infecting virus sequence and potential escape mutations. Here, we identified different viral variants of the HCV NS3-1073 epitope in resolvers. These variants are known to affect either HLA-A2 binding or TCR recognition (40, 41). The fact that subjects SR.5 and SR.8 spontaneously cleared their acute infection suggest that the diverse repertoire and the public TCRs identified in these subjects were flexible and were able to recognize both the reference sequence (used in the tetramers) and the autologous sequences effectively.

We identified a set of thirteen NS3-1073 specific public clonotypes with different expansion profiles. This might be explained by the usage of a different α chain leading to a TCRαβ clonotype of higher or lesser affinity to the cognate epitope. We could not examine the TCRαβ paired sequences in our study but were able to identify three of them from publicly available data (30). This approach remains very limited to one subject and three sequences. Additional studies using single cell sequencing approaches coupled with cloning of the receptor(s) of interest and functional analysis would provide better insights about the role of the α chain, the αβ pairing and a more accurate measure of functional avidity.

NS3-1073 specific public clonotypes were maintained within the memory pool and re-expanded upon reinfection. We had previously reported that the NS3-1073 specific TCR repertoire becomes focused upon reinfection with preferential expansion of CD8+ T cell clonotypes of high functional avidity (16). So, it is also possible that the expanded public TCRs are those with the highest functional avidity. Indeed, data from individual clones generated from subject SR/SR-1 contained two of the public clonotypes identified in this study. These clonotypes were of high functional avidity and polyfunctionality indices. Additional testing using a broader panel of T cell clones will be required to validate that possibility.

The high prevalence of public clonotypes observed during acute HCV was also characterized by preferential usage of the TCRB V04 gene family. One single TCR clonotype in particular (TRBV4-02/TRBJ02-02) was identified in 12 out of 14 subjects. Other public clonotypes using the V04 gene family, specific to the CMV pp65 (42) and HIV p24 Gag-derived KK10 epitopes (3), were previously reported. The presence of such public clonotypes and their maintenance within the long-term memory pool were found to be shaped by convergent recombination (43). Indeed, our data demonstrate that combinatorial (Supplementary Table S2) and/or junctional (data not shown) diversities contribute to generating the same amino acid sequence.

We identified CDR3 AA sequences shared with other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes. Wedemeyer et al. were the first to characterize HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells cross-reactivity to the NA-231 epitope from the influenza virus (17). Yet, it was later shown that this HCV NS3-1073/NA-231 cross-reactivity is of low affinity (44), and that their structural conformation and their specific TCR repertoires are distinct (45). This is in line with our results where no HCV NS3-1073/FLU NA-231 shared CDR3 AA sequence were identified. Zhang et al. had tested the directionality of this cross-reactivity and showed that HCV NS3-1073 peptides can induce CMV (pp65-495), Flu (M1-58) and EBV (LMP2-426) CD8+ T cells expansion (i.e. “reverse” cross-reactivity) and not vice-versa (19, 44). Altogether, our data and others suggest that cross-reactivity of HCV NS3-1073 specific CD8+ T cells with other epitopes is more likely after HCV exposure.

We identified shared CDR3 AA sequences with multiple HLA-A2 restricted epitopes. Yet, the majority of shared clonotypes were of low frequency. While we identified public clonotypes 4 that was also present in the seronegative cohort, none of the public clonotypes identified in our study were shared with other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes. Technical confounders like the use of different sequencing approaches and in vitro expansion prior to analysis may have limited our capacity to identify exactly matched CDR3 sequences. Nevertheless, there was little to no functional cross-reactivity of HCV NS3-1073 specific T cells in response to any of the shared HLA-A2 restricted epitopes. Overall, shared clonotypes represented only a minor fraction of the HCV NS3-1073 specific TCR repertoire. Thus, even though a pool of cross-reactive memory CD8+ T cells may exist prior to HCV infection, they play a limited role during primary HCV infection but may contribute to HCV-related liver disease severity as previously observed (18, 46).

In conclusion, our results demonstrate preferential usage of TCRB V04 and V06 gene families, as well as the expansion of public TCR clonotypes unique to HCV, irrespective of infection outcome or autologous virus sequence. Additional studies examining the functional avidity of such public clonotypes and characterization of the TCR repertoire of other immunodominant HCV epitopes are required. Our data contribute to publicly available TCR repertoire databases, that can be utilized to predict specificities of expanded T cells in specific pathological conditions or infections (47), improve the development of algorithms to identify HCV-specific TCR clonotypes and their relationship to other specificities, and tracking HCV specific clonotypes during future clinical trials for HCV vaccines (31, 48, 49).

Supplementary Material

Key Points:

Identified thirteen unique public clonotypes specific for the HCV NS3-1073 epitope

Public clonotypes expanded during acute HCV infection and reinfection

Low frequency of cross-reactive TCRs targeting other HLA-A2 restricted epitopes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all study subjects for participating in this study and we thank Dr. Dominique Gauchat and Philippe St-Onge of the flow cytometry core of the CRCHUM for their technical help with cell sorting experiments.

Funding:

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) U01AI131313, R01AI136533 and U19AI159819, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (PJT-173467) Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions, and Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQS) AIDS and Infectious Disease Network (Réseau SIDA-MI). SM is supported by a doctoral fellowship from the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C (CanHepC). CanHepC is funded by a joint initiative of the CIHR (NHC142832) and the Public Health Agency of Canada. MB received postdoctoral fellowships from the FRQS, the American Liver Foundation and CanHepC. MSA received doctoral fellowships from CIHR and CanHepC. JB is the Canada Research Chair in Addiction Medicine. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript

Abbreviations used in this article:

- EDI

Estimated date of infection

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- PWID

people who inject drugs

REFERENCES

- 1.Turner SJ, La Gruta NL, Kedzierska K, Thomas PG, and Doherty PC. 2009. Functional implications of T cell receptor diversity. Curr Opin Immunol 21: 286–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trautmann L, Rimbert M, Echasserieau K, Saulquin X, Neveu B, Dechanet J, Cerundolo V, and Bonneville M. 2005. Selection of T cell clones expressing high-affinity public TCRs within Human cytomegalovirus-specific CD8 T cell responses. J Immunol 175: 6123–6132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iglesias MC, Almeida JR, Fastenackels S, van Bockel DJ, Hashimoto M, Venturi V, Gostick E, Urrutia A, Wooldridge L, Clement M, Gras S, Wilmann PG, Autran B, Moris A, Rossjohn J, Davenport MP, Takiguchi M, Brander C, Douek DC, Kelleher AD, Price DA, and Appay V. 2011. Escape from highly effective public CD8+ T-cell clonotypes by HIV. Blood 118: 2138–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladell K, Hashimoto M, Iglesias MC, Wilmann PG, McLaren JE, Gras S, Chikata T, Kuse N, Fastenackels S, Gostick E, Bridgeman JS, Venturi V, Arkoub ZA, Agut H, van Bockel DJ, Almeida JR, Douek DC, Meyer L, Venet A, Takiguchi M, Rossjohn J, Price DA, and Appay V. 2013. A molecular basis for the control of preimmune escape variants by HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Immunity 38: 425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel-Hakeem MS, Bedard N, Murphy D, Bruneau J, and Shoukry NH. 2014. Signatures of protective memory immune responses during hepatitis C virus reinfection. Gastroenterology 147: 870–881 e878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osburn WO, Fisher BE, Dowd KA, Urban G, Liu L, Ray SC, Thomas DL, and Cox AL. 2010. Spontaneous control of primary hepatitis C virus infection and immunity against persistent reinfection. Gastroenterology 138: 315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pestka JM, Zeisel MB, Blaser E, Schurmann P, Bartosch B, Cosset FL, Patel AH, Meisel H, Baumert J, Viazov S, Rispeter K, Blum HE, Roggendorf M, and Baumert TF. 2007. Rapid induction of virus-neutralizing antibodies and viral clearance in a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 6025–6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai SL, Chen YM, Chen MH, Huang CY, Sheen IS, Yeh CT, Huang JH, Kuo GC, and Liaw YF. 1998. Hepatitis C virus variants circumventing cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity as a mechanism of chronicity. Gastroenterology 115: 954–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miles JJ, Thammanichanond D, Moneer S, Nivarthi UK, Kjer-Nielsen L, Tracy SL, Aitken CK, Brennan RM, Zeng W, Marquart L, Jackson D, Burrows SR, Bowden DS, Torresi J, Hellard M, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J, and Bharadwaj M. 2011. Antigen-driven patterns of TCR bias are shared across diverse outcomes of human hepatitis C virus infection. J Immunol 186: 901–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takaki A, Wiese M, Maertens G, Depla E, Seifert U, Liebetrau A, Miller JL, Manns MP, and Rehermann B. 2000. Cellular immune responses persist and humoral responses decrease two decades after recovery from a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Nat Med 6: 578–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward S, Lauer G, Isba R, Walker B, and Klenerman P. 2002. Cellular immune responses against hepatitis C virus: the evidence base 2002. Clin Exp Immunol 128: 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauer GM, Lucas M, Timm J, Ouchi K, Kim AY, Day CL, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, Paranhos-Baccala G, Sheridan I, Casson DR, Reiser M, Gandhi RT, Li B, Allen TM, Chung RT, Klenerman P, and Walker BD. 2005. Full-breadth analysis of CD8+ T-cell responses in acute hepatitis C virus infection and early therapy. J Virol 79: 12979–12988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lechner F, Wong DK, Dunbar PR, Chapman R, Chung RT, Dohrenwend P, Robbins G, Phillips R, Klenerman P, and Walker BD. 2000. Analysis of successful immune responses in persons infected with hepatitis C virus. J Exp Med 191: 1499–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thimme R, Oldach D, Chang KM, Steiger C, Ray SC, and Chisari FV. 2001. Determinants of viral clearance and persistence during acute hepatitis C virus infection. J Exp Med 194: 1395–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruner NH, Gerlach TJ, Jung MC, Diepolder HM, Schirren CA, Schraut WW, Hoffmann R, Zachoval R, Santantonio T, Cucchiarini M, Cerny A, and Pape GR. 2000. Association of hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ T cells with viral clearance in acute hepatitis C. J Infect Dis 181: 1528–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdel-Hakeem MS, Boisvert M, Bruneau J, Soudeyns H, and Shoukry NH. 2017. Selective expansion of high functional avidity memory CD8 T cell clonotypes during hepatitis C virus reinfection and clearance. PLoS Pathog 13: e1006191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wedemeyer H, Mizukoshi E, Davis AR, Bennink JR, and Rehermann B. 2001. Cross-reactivity between hepatitis C virus and Influenza A virus determinant-specific cytotoxic T cells. J Virol 75: 11392–11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urbani S, Amadei B, Fisicaro P, Pilli M, Missale G, Bertoletti A, and Ferrari C. 2005. Heterologous T cell immunity in severe hepatitis C virus infection. J Exp Med 201: 675–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S, Bakshi RK, Suneetha PV, Fytili P, Antunes DA, Vieira GF, Jacobs R, Klade CS, Manns MP, Kraft AR, Wedemeyer H, Schlaphoff V, and Cornberg M. 2015. Frequency, Private Specificity, and Cross-Reactivity of Preexisting Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)-Specific CD8+ T Cells in HCV-Seronegative Individuals: Implications for Vaccine Responses. J Virol 89: 8304–8317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grebely J, Morris MD, Rice TM, Bruneau J, Cox AL, Kim AY, McGovern BH, Shoukry NH, Lauer G, Maher L, Lloyd AR, Hellard M, Prins M, Dore GJ, Page K, and In C. S. G.. 2013. Cohort profile: the international collaboration of incident HIV and hepatitis C in injecting cohorts (InC3) study. Int J Epidemiol 42: 1649–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badr G, Bedard N, Abdel-Hakeem MS, Trautmann L, Willems B, Villeneuve JP, Haddad EK, Sekaly RP, Bruneau J, and Shoukry NH. 2008. Early interferon therapy for hepatitis C virus infection rescues polyfunctional, long-lived CD8+ memory T cells. J Virol 82: 10017–10031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Team, R. C. 2018. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shugay M, Bagaev DV, Zvyagin IV, Vroomans RM, Crawford JC, Dolton G, Komech EA, Sycheva AL, Koneva AE, Egorov ES, Eliseev AV, Van Dyk E, Dash P, Attaf M, Rius C, Ladell K, McLaren JE, Matthews KK, Clemens EB, Douek DC, Luciani F, van Baarle D, Kedzierska K, Kesmir C, Thomas PG, Price DA, Sewell AK, and Chudakov DM. 2018. VDJdb: a curated database of T-cell receptor sequences with known antigen specificity. Nucleic Acids Res 46: D419–D427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelletier S, Drouin C, Bedard N, Khakoo SI, Bruneau J, and Shoukry NH. 2010. Increased degranulation of natural killer cells during acute HCV correlates with the magnitude of virus-specific T cell responses. J Hepatol 53: 805–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wieland D, Kemming J, Schuch A, Emmerich F, Knolle P, Neumann-Haefelin C, Held W, Zehn D, Hofmann M, and Thimme R. 2017. TCF1(+) hepatitis C virus-specific CD8(+) T cells are maintained after cessation of chronic antigen stimulation. Nature communications 8: 15050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roederer M, Nozzi JL, and Nason MC. 2011. SPICE: exploration and analysis of post-cytometric complex multivariate datasets. Cytometry A 79: 167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.EH. S 1949. Measurement of diversity. Nature. 163: 688. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shannon CE 1948. The mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J 27: 379–423. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H, Ye C, Ji G, and Han J. 2012. Determinants of public T cell responses. Cell Research 22: 33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eltahla AA, Rizzetto S, Pirozyan MR, Betz-Stablein BD, Venturi V, Kedzierska K, Lloyd AR, Bull RA, and Luciani F. 2016. Linking the T cell receptor to the single cell transcriptome in antigen-specific human T cells. Immunol Cell Biol 94: 604–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pogorelyy MV, Minervina AA, Touzel MP, Sycheva AL, Komech EA, Kovalenko EI, Karganova GG, Egorov ES, Komkov AY, Chudakov DM, Mamedov IZ, Mora T, Walczak AM, and Lebedev YB. 2018. Precise tracking of vaccine-responding T cell clones reveals convergent and personalized response in identical twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115: 12704–12709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen G, Yang X, Ko A, Sun X, Gao M, Zhang Y, Shi A, Mariuzza RA, and Weng NP. 2017. Sequence and Structural Analyses Reveal Distinct and Highly Diverse Human CD8(+) TCR Repertoires to Immunodominant Viral Antigens. Cell Rep 19: 569–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Annels NE, Callan MF, Tan L, and Rickinson AB. 2000. Changing patterns of dominant TCR usage with maturation of an EBV-specific cytotoxic T cell response. J Immunol 165: 4831–4841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee ES, Thomas PG, Mold JE, and Yates AJ. 2017. Identifying T Cell Receptors from High-Throughput Sequencing: Dealing with Promiscuity in TCRalpha and TCRbeta Pairing. PLoS Comput Biol 13: e1005313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rius C, Attaf M, Tungatt K, Bianchi V, Legut M, Bovay A, Donia M, Thor Straten P, Peakman M, Svane IM, Ott S, Connor T, Szomolay B, Dolton G, and Sewell AK. 2018. Peptide-MHC Class I Tetramers Can Fail To Detect Relevant Functional T Cell Clonotypes and Underestimate Antigen-Reactive T Cell Populations. J Immunol 200: 2263–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfl M, Rutebemberwa A, Mosbruger T, Mao Q, Li HM, Netski D, Ray SC, Pardoll D, Sidney J, Sette A, Allen T, Kuntzen T, Kavanagh DG, Kuball J, Greenberg PD, and Cox AL. 2008. Hepatitis C virus immune escape via exploitation of a hole in the T cell repertoire. J Immunol 181: 6435–6446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer-Olson D, Shoukry NH, Brady KW, Kim H, Olson DP, Hartman K, Shintani AK, Walker CM, and Kalams SA. 2004. Limited T cell receptor diversity of HCV-specific T cell responses is associated with CTL escape. J Exp Med 200: 307–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang OO, Sarkis PT, Ali A, Harlow JD, Brander C, Kalams SA, and Walker BD. 2003. Determinant of HIV-1 mutational escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med 197: 1365–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Douek DC, Betts MR, Brenchley JM, Hill BJ, Ambrozak DR, Ngai KL, Karandikar NJ, Casazza JP, and Koup RA. 2002. A novel approach to the analysis of specificity, clonality, and frequency of HIV-specific T cell responses reveals a potential mechanism for control of viral escape. J Immunol 168: 3099–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fytili P, Dalekos GN, Schlaphoff V, Suneetha PV, Sarrazin C, Zauner W, Zachou K, Berg T, Manns MP, Klade CS, Cornberg M, and Wedemeyer H. 2008. Cross-genotype-reactivity of the immunodominant HCV CD8 T-cell epitope NS3-1073. Vaccine 26: 3818–3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soderholm J, Ahlen G, Kaul A, Frelin L, Alheim M, Barnfield C, Liljestrom P, Weiland O, Milich DR, Bartenschlager R, and Sallberg M. 2006. Relation between viral fitness and immune escape within the hepatitis C virus protease. Gut 55: 266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huth A, Liang X, Krebs S, Blum H, and Moosmann A. 2019. Antigen-Specific TCR Signatures of Cytomegalovirus Infection. J Immunol 202: 979–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venturi V, Quigley MF, Greenaway HY, Ng PC, Ende ZS, McIntosh T, Asher TE, Almeida JR, Levy S, Price DA, Davenport MP, and Douek DC. 2011. A mechanism for TCR sharing between T cell subsets and individuals revealed by pyrosequencing. J Immunol 186: 4285–4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kasprowicz V, Ward SM, Turner A, Grammatikos A, Nolan BE, Lewis-Ximenez L, Sharp C, Woodruff J, Fleming VM, Sims S, Walker BD, Sewell AK, Lauer GM, and Klenerman P. 2008. Defining the directionality and quality of influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell cross-reactivity in individuals infected with hepatitis C virus. J Clin Invest 118: 1143–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grant EJ, Josephs TM, Valkenburg SA, Wooldridge L, Hellard M, Rossjohn J, Bharadwaj M, Kedzierska K, and Gras S. 2016. Lack of Heterologous Cross-reactivity toward HLA-A*02:01 Restricted Viral Epitopes Is Underpinned by Distinct alphabetaT Cell Receptor Signatures. J Biol Chem 291: 24335–24351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vali B, Tohn R, Cohen MJ, Sakhdari A, Sheth PM, Yue FY, Wong D, Kovacs C, Kaul R, and Ostrowski MA. 2011. Characterization of cross-reactive CD8+ T-cell recognition of HLA-A2-restricted HIV-Gag (SLYNTVATL) and HCV-NS5b (ALYDVVSKL) epitopes in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency and hepatitis C viruses. J Virol 85: 254–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gantner P, Pagliuzza A, Pardons M, Ramgopal M, Routy JP, Fromentin R, and Chomont N. 2020. Single-cell TCR sequencing reveals phenotypically diverse clonally expanded cells harboring inducible HIV proviruses during ART. Nat Commun 11: 4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glanville J, Huang H, Nau A, Hatton O, Wagar LE, Rubelt F, Ji X, Han A, Krams SM, Pettus C, Haas N, Arlehamn CSL, Sette A, Boyd SD, Scriba TJ, Martinez OM, and Davis MM. 2017. Identifying specificity groups in the T cell receptor repertoire. Nature 547: 94–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pogorelyy MV, Minervina AA, Chudakov DM, Mamedov IZ, Lebedev YB, Mora T, and Walczak AM. 2018. Method for identification of condition-associated public antigen receptor sequences. Elife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data of all TCR sequences are available at https://clients.adaptivebiotech.com/pub/mazouz-2021-ji (DOI:10.21417/SM2021JI).