Abstract

Immune-checkpoint blockade (ICB) has shown remarkable clinical success in boosting antitumor immunity. However, the breadth of its cellular targets and specific mode of action remain elusive. We find that tumor-infiltrating follicular regulatory T (TFR) cells are prevalent in tumor tissues of several cancer types. They are primarily located within tertiary lymphoid structures and exhibit superior suppressive capacity and in vivo persistence as compared with regulatory T cells, with which they share a clonal and developmental relationship. In syngeneic tumor models, anti-PD-1 treatment increases the number of tumor-infiltrating TFR cells. Both TFR cell deficiency and the depletion of TFR cells with anti-CTLA-4 before anti-PD-1 treatment improve tumor control in mice. Notably, in a cohort of 271 patients with melanoma, treatment with anti-CTLA-4 followed by anti-PD-1 at progression was associated with better a survival outcome than monotherapy with anti-PD-1 or anti-CTLA-4, anti-PD-1 followed by anti-CTLA-4 at progression or concomitant combination therapy.

An increased density of regulatory T (TREG) cells in tumors has been linked to poor survival outcomes1. In secondary lymphoid organs, TREG cells have been shown to differentiate into PD-1-expressing follicular regulatory T (TFR) cells that restrain the germinal center responses2, impede humoral immunity towards self-antigens and display heightened suppressive capacity when compared with TREG cells3,4. At present, TFR cells are characterized by their joint expression of the surface molecules CXCR5 and GITR2,5 or co-expression of the transcription factors FOXP3 and BCL-6 (ref. 6). Several studies have demonstrated that, depending on the disease context and organ, cells of the T follicular lineage express varying levels of CXCR5 and BCL-6 (refs. 7,8). Notably, it has been shown that deletion of CXCR5 expression in FOXP3-expressing cells does not abrogate the development and maintenance of BCL-6+ TFR cells6, indicating that distinct subsets of TFR cells exist that not only differ in their expression of CXCR5 and BCL-6 but also in their expression of CD25 (refs. 9,10).

Although the role of follicular helper T (TFH) cells, B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) in driving antitumor immune responses and responsiveness to anti-PD-1 therapy is now beginning to be elucidated11-14, few studies have examined the potential effects of anti-PD-1 therapy on the regulatory T cell compartment. Accordingly, TFR cells as well as their functional role in cancer and their responsiveness to immune-checkpoint blockade (ICB) have been completely overlooked so far. Based on the well-described functions of TFR cells in secondary lymphoid organs, we hypothesized that TFR cells are likely to be present in the TLS of tumors and modulate immune responses in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Moreover, as TFR cells have a skewed T cell antigen receptor (TCR) repertoire towards self-antigens and because cancerous cells frequently express self- or altered-self-antigens, we hypothesized that TREG and TFR cells accumulate in parallel in the TME as a means of effective immune evasion.

Here we report that TFR cells account for a substantial proportion of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells and, importantly, that they are highly responsive to ICB. We further demonstrate that TFR cells are highly suppressive, are prevalent in several different cancer types and accumulate in tumor tissues over time, which is probably mediated by their higher proliferative capacity and persistence in vivo, which is dependent on BCL-6. Depletion of TFR cells or blocking their activity with anti-CTLA-4 before anti-PD-1 therapy improved the efficacy of anti-PD-1 treatment in mouse tumor models and were also associated with better survival outcomes in a large cohort of patients with melanoma. Finally, we found that TFR cells, but not TREG cells, were enriched in TLS, suggesting that TFR cells might also impair the survival of patients and impede the efficacy of immunotherapy treatment by regulating TLS, consistent with their well-described role in secondary lymphoid organs3,4. Our findings thus challenge the current clinical practice of unselective administration of anti-PD-1 therapy, which hence overlooks any possibility for its potential to impede antitumor immune responses. By elucidating the functional properties of intratumoral TFR cells and identifying them as one of the major targets of ICB, we provide critical insights into how anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 therapies mediate their function and highlight the potential clinical benefit of depleting intratumoral TFR cells before the initiation of anti-PD-1 therapy.

Results

TFR cells are present in multiple cancer types.

We integrated nine published single-cell RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets and performed a meta-analysis of the tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells (n = 25,149) from patients with six different cancer types. As expected, FOXP3-expressing CD4+ T cells (that is, TREG cells) clustered distinctly and represented 5–55% of all tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1a,b). We found that a substantial proportion (5–30% in all tumor types) of the FOXP3-expressing CD4+ T cells co-expressed BCL6 and/or CXCR5 (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1a), which encode for markers indicative of cells of a follicular lineage in humans and mice2,15, and thus represent tumor-infiltrating TFR cells, an important regulatory subset that has not been appreciated so far. We confirmed the presence (approximately 10–20% of all tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells) and localization of TFR cells in tumor samples from patients with treatment-naive early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by multi-parameter flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2a-f, Extended Data Fig. 1b-d). TFR cells, like TREG cells, maintained the surface expression of CD25 and ICOS (Fig. 2b). To determine whether the immunotherapies that are available at present, like anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 therapies, also target tumor-infiltrating TFR cells, we assessed their expression of CTLA-4 and PD-1. Notably, TFR cells expressed the highest levels of CTLA-4 and PD-1 among all tumor-infiltrating T cells (TILs; Fig. 2c,d), suggesting that anti-CTLA-4 can target TFR cells more efficiently and that anti-PD-1 therapies may inadvertently activate such suppressive TFR cells. A fraction (approximately 15%) of all tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells exhibited a TFH cell phenotype (Fig. 2a) that lacked expression of CD25 but expressed ICOS, CTLA-4 and PD-1 (Fig. 2b-d). Given the recent findings highlighting the importance of B cells, TFH cells and TLS with regard to heightened antitumor immunity, improved patient survival and responsiveness to immunotherapy11-14, we next assessed the cellular context in which TFR cells exert their function within the TME. Multicolor-immunohistochemical analyses confirmed the presence of TFR cells in tumor tissues (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 1d). Crucially, we found that TFR cells, unlike TREG cells, were predominantly located in TLS (Fig. 2f), indicating that TFR cells might inhibit antitumor immunity by impeding the function of cells in their vicinity (that is, ectopic B and TFH cell responses) or by regulating TLS formation or maintenance.

Fig. 1 ∣. Tumor-infiltrating TFR cells are highly prevalent in human cancers.

a, Integrated analysis of nine single-cell RNA-seq datasets from six different cancer types displayed by UMAP. Seurat clustering of 25,149 CD4+ T cells colored based on cluster type (left) and study (middle). Seurat-normalized expression of FOXP3 in different clusters (right; see also Extended Data Fig. 1 and Methods). b,c, Frequency of FOXP3− and FOXP3+ (TREG) cells in tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells (b), and BCL6+ TFR, CXCR5+ TFR and BCL6+CXCR5+ TFR in tumor-infiltrating TREG cells (c) in the assessed datasets. The sequencing technologies employed (10x Genomics, MARS and Smart sequencing) in the different datasets are indicated.

Fig. 2 ∣. Tumor-infiltrating TFR cells are primarily located in the TLS.

a–d, Flow-cytometric analysis of CD4+ T, TREG, TFH and TFR cells from n = 10 treatment-naive patients with NSCLC. FMO, fluorescence minus one control. Representative contour plots (a) and histogram plots (b–d) of CD8+ and CD4+ TILs are shown. a, Frequency of CD8+ T (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD8+), TREG (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5−CD127−CD25+), TFH (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5+GITR−) and TFR (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5+GITR+) cells (left). The numbers in the contour plots (right) indicate the percentage of cells in the outlined areas. b, Frequency and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD25 and ICOS (CD25, P = 0.002 and 0.0137 for the frequency and MFI, respectively; and ICOS, P = 0.0645 and 0.0039 for the frequency and MFI, respectively, of the indicated comparisons). c, Intracellular CTLA-4 expression and MFI in TREG (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5−FOXP3+BCL-6−), TFH (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+BCL-6+FOXP3−) and TFR (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+BCL-6+FOXP3+) cells (P = 0.0039 and 0.0020 for the frequency and MFI, respectively, of the indicated comparisons). d, Frequency and MFI of PD-1 expression (P = 0.0020 for the indicated comparisons in the frequency and MFI plots). e, Whole-slide multiplexed immunohistochemistry analyses of TREG and TFR cells in NSCLC tissue sections from the patients in a–d (left and middle). The micrographs show PanCK, CD4, CXCR5, CD20, FOXP3 and BCL-6 staining. The pink arrows indicate CD4+FOXP3+BCL-6+ TFR cells in a region of interest that was selected for the high density of TFR cells. Scale bars, 250 μm (left) and 25 μm (middle). i, Zoomed-in area shown in the top middle images. ii, Zoomed-in area shown in the bottom middle images. The proportion of FOXP3− and FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells (top right), and TREG and TFR cells (bottom right) from the whole-slide histocytometry analyses of each sample from a–d are shown. f, Proportion of TREG and TFR cells in the tumor stroma and TLS (P = 0.0002 for both TREG and TFR) from whole-slide histocytometry analyses for n = 8 treatment-naive patients with NSCLC. All data are the mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test between TREG and TFR cells (b–d) and two-tailed Mann–Whitney test between TLS and stroma localization for TREG and TFR cells (f); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

TFR cells exhibit unique transcriptomic features.

As few studies have thoroughly analyzed the transcriptomic features of TFR cells, we first utilized well-established immunization models in mice to gain mechanistic insights into the function of TFR cells and assess whether the features identified in human tumor-infiltrating TFR cells are also applicable to murine TFR cells. Immunization with ovalbumin (OVA) and adjuvant (complete Freund’s adjuvant or monophosphoryl lipid A) induced robust TFR responses (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Comparative analysis of their transcriptome with that of other TH subsets showed increased expression of many transcripts, specifically in TFR cells (n = 84; Extended Data Fig. 2b-e) and notably the transcripts enriched in TREG cells compared with both the TFH and effector T cell (TEFF) populations (n = 127) were also highly expressed in TFR cells (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). These included several transcripts (for example, Tnfrsf1b16, Lag3 (ref. 17), Tigit18, Batf19 and Il1r2 (refs. 1,20)) encoding for products associated with heightened suppressive capacity, Ccr8—which is associated with particularly poor clinical outcomes in cancer1,21—and genes associated with CD8+ T cell dysfunction and survival22 (Pdcd1 and Tox; Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). The protein expression levels of some of these molecules—for example, TNFR2 (encoded by TNFRSF1B), LAG3, TIGIT and CCR8—were confirmed in human tumor-infiltrating TFR cells (Extended Data Fig. 2f), suggesting a suppressive capacity of TFR cells and probable conservation of functional potential across species.

We next performed bulk RNA-seq analyses of enriched populations of TREG (CD4+CD25+CXCR5−) and TFR cells (CD4+CXCR5+GITR+; Extended Data Fig. 1b) isolated from tumor samples of patients with NSCLC. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA; Extended Data Fig. 3a) of bulk-sorted human TREG (CD4+CD25+CXCR5−) and TFR (CD4+CXCR5+GITR+; Extended Data Fig. 1b) cells identified a module (pink) that was positively correlated with the TFR phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Importantly, this module contained both BCL6 and FOXP3, demonstrating the linked expression of these genes, specifically in TFR cells. Ingenuity pathway analysis of the pink module (the module positively correlated with the TFR phenotype) identified a substantial enrichment of genes involved in the cell cycle, transcriptional and translational activity and mTOR signaling, indicative of increased TFR cell proliferation and activity (Extended Data Fig. 3c). We confirmed that TFR cells indeed had greater cell proliferation in the TME, as evidenced by increased KI-67 staining (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Analysis of differential gene expression between enriched populations of TFR and TREG cells identified over 100 transcripts that were expressed at higher levels in TFR cells (Extended Data Fig. 3e). Co-expression analysis of these differentially expressed transcripts revealed a number of highly correlated novel genes (for example, DUSP14 and CLP1) that may play a role in TFR cell function. Moreover, we identified TCF7 (encoding TCF-1) as a highly connected hub gene in this transcriptomic network (Extended Data Fig. 3f) and confirmed that the proportion of cells expressing TCF-1 was higher in TFR cells compared with TREG cells (Extended Data Fig. 3g). Interestingly, TCF-1-expressing CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes have recently been recognized for their ability for self-renewal, their stem-like properties23,24 and their pivotal role in mediating anti-cancer immune attack induced by anti-PD-1 immunotherapy25,26, suggesting that TCF-1 expression might confer similar features on TFR cells. Together, these data indicate that intratumoral TREG and TFR cells differ in their molecular profile and demonstrate that TFR cells are highly proliferative in tumor tissue.

Intratumoral TREG and TFR cells are clonally and developmentally related.

Recent data demonstrate that tumor-infiltrating TREG cells potently recognize tumor (neo)antigens and undergo clonal expansion following antigen-encounter27. Given that antigen-specific activation of TREG cells in the context of viral infection has been implicated in promoting their differentiation into TFR cells via TCF-1-mediated induction of BCL-6 (ref. 28), we hypothesized that tumor-associated antigen (TAA) recognition may also trigger TREG-to-TFR conversion within the TME. To assess this, we performed combined single-cell RNA-seq and TCR sequencing of sorted CD4+ (TFH, TREG and TFR) and CD8+ TILs from primary tumor tissue and tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes of two patients with HNSCC (n = 8,722 cells). Unsupervised clustering revealed two distinct CD4+ T cell clusters (clusters 1 and 6) that were enriched for FOXP3 expression (Fig. 3a) and exhibited distinct transcriptomic signatures (Fig. 3b). Gene-set enrichment analysis showed that the cells in cluster 6 (yellow) were significantly enriched for follicular (Fig. 3c) and TFR cell signatures (Fig. 3d), thus characterizing TFR cells, whereas the cells in cluster 1 (green) depict TREG cells. Pathway analysis of the genes that were differentially expressed (Fig. 3b) between TFR and TREG cells showed enrichment for transcripts linked to metabolism, cell activation and co-stimulation (Fig. 3e). Moreover, TFR cells expressed higher levels of transcripts linked to TFR function and suppressive capacity (for example, CTLA4, IL10, TGFB1, TNFRSF9 and IL1R2) and cell-cycle genes (TOP2A and MKI67; Fig. 3f). Accordingly, although the TREG and TFR cells shared clonotypes (Fig. 3g,h), the TFR cells were more clonally expanded than TREG cells (Fig. 3i). Importantly, TCR sharing and trajectory analysis of cells in the FOXP3-enriched clusters indicate intratumoral conversion of TREG to TFR cells (Fig. 3g,h and Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). To further substantiate this idea, we re-analyzed one of the largest single-cell RNA-seq datasets20 of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells and found that the majority of clonally expanded TFR clonotypes (approximately 93%) were shared with TREG cells (Extended Data Fig. 5a, top) but not TFH cells (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Furthermore, the TREG cells that shared clonotypes with TFR cells predominantly expressed 4-1BB (TNFRSF9) transcripts (Extended Data Fig. 5a (bottom) and Extended Data Fig. 5c), which implies recent TCR activation29 and is indicative of potential intratumoral conversion of TAA-activated TREG cells to TFR cells. The trajectory analysis implies that the 4-1BB+ TREG cells (TAA-experienced) and TREG cells sharing TCRs with the clonally expanded TFR cells (purple) depict transitional states during the differentiation of TREG cells into TFR cells (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Importantly, transcripts linked to cell activation, co-stimulation and suppressive function (Fig. 3j) were expressed at higher levels in 4-1BB+ TREG cells (red), TCR-sharing TREG cells (purple) and clonally expanded TFR cells (yellow) compared with 4-1BB− TREG cells (green), a gene signature that was highly associated with Monocle component 1 (Fig. 3j and Extended Data Fig. 5e). Compared with 4-1BB− TREG cells, TFR cells and TREG cells on their trajectory to differentiate into TFR cells also exhibited significant downregulation of CCR7 and S1PR1—genes that encode receptors required for tissue egress—suggesting tissue residency of TFR cells30 (Fig. 3j).

Fig. 3 ∣. Comparison of human tumor-infiltrating TREG and TFR cells.

a, Analysis of 10x Genomics single-cell RNA-seq data, displayed by UMAP. Seurat clustering of 8,722 CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from primary tumor tissue and metastasized tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes colored according to the cluster type (left). The other three panels show the Seurat-normalized expression of CD8B, CD4 and FOXP3. b, Heatmap comparing the gene expression of the cells in clusters 1 and 6. Transcripts that change in expression more than 0.25-fold with an adjusted P ≤ 0.05 are depicted. c,d, Gene-set enrichment analysis for follicular-feature44 (c) and TFR-feature genes (d; derived from Fig. 3j) for cells in clusters 1 and 6 ordered by the log2-transformed fold-change value. e, Ingenuity pathway analysis of transcripts that are differentially expressed (n = 1,245) between clusters 1 and 6. f, Comparison of the expression levels of the indicated transcripts in the cells in clusters 1 (left) and 6 (right). CPM, counts per million. g, TraCer plots of all clonally expanded cells (≥2 clonotypes) in clusters 1 and 6 colored according to the cluster origin. h, Euler diagram showing the overlap between clonotypes in clusters 1 and 6. i, Mean percentage of clonally expanded cells in clusters 1 and 6. j, Heatmap illustrating the intersection of genes that were differentially expressed (with mean transcripts per million (TPM) > 25) when comparing 4-1BB− TREG cells with three populations: 4-1BB+ TREG cells, clonally expanded TREG cells sharing their TCRs with TFR cells, and clonally expanded TFR cells (the distinct cell populations are indicated with colored bars). Genes linked to immunosuppressive function, co-stimulation and tissue residency are highlighted.

These observations are consistent with a model in which the TME is initially infiltrated by a large and highly diverse pool of bystander (that is, not TAA-specific) TREG cells and a smaller pool of TAA-specific TREG clones, which are poised for differentiation into tissue-resident TFR cells. This implies that TFR cells comprise a larger proportion of tumor-reactive clones than TREG cells, an idea that was substantiated by our finding that TFR cells expressed 4-1BB significantly higher levels than TREG cells (Extended Data Fig. 5f) and also by the higher degree of clonal expansion (Fig. 3i).

TFR cells exhibit a superior suppressive capacity.

We next assessed the frequency, activity and functional responsiveness of TFR cells in murine tumor models. TFR cells (CD3+CD4+BCL-6+FOXP3+) were present in tumor samples from two syngeneic tumor model systems (B16F10 melanoma and MC38 colorectal tumor cell lines; Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 6a) but, importantly, lacked expression of CXCR5. Notably, recent studies demonstrated that the ablation of CXCR5 expression in FOXP3+ T cells does not abrogate the development of BCL-6+ TFR cells, which still enter the germinal center reaction6. Thus, BCL-6 expression in FOXP3+ cells delineates TFR cells even in the absence of CXCR5. Similar to human TFR cells, murine TFR cells exhibited increased proliferative potential, as evidenced by the levels of KI-67 expression, and increased expression of TCF-1 and 4-1BB compared with TREG cells (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, TFR cells also expressed significantly higher levels of the transcription factor TOX (Fig. 4c). Given that TOX was recently shown to be essential for the function and survival of TCF-1-expressing CD8+ T cells following chronic antigen-exposure, we speculate that TOX expression in TFR cells may help maintain their superior functionality in the face of sustained stimulation by TAA31,32.

Fig. 4 ∣. Frequency and functional responsiveness of TFR cells in murine tumor models.

a–c, Mice were inoculated with B16F10-OVA or MC38-OVA cells subcutaneously (s.c.) on the right flank. Analyses of tumor-infiltrating TREG (CD19−CD45+CD3+CD4+BCL-6−FOXP3+) and TFR (CD19−CD45+CD3+CD4+BCL-6+FOXP3+) cells were performed. a, Flow-cytometric analysis of the frequency of tumor-infiltrating TREG and TFR cells in the two tumor models at day 21 after tumor inoculation (n = 6 (B16F10) and 7 (MC38) mice). b, Flow-cytometric analysis of the MFI and frequencies of expression of KI-67 (P = 0.002), TCF-1 (P = 0.002) and 4-1BB (P = 0.002) in the two cell types in the B16F10-OVA model at day 14 after tumor inoculation (n = 10 mice per group). c, Representative FACS contour plots depicting the expression of TOX and TCF-1 in CD8+ T cells, TREG cells and TFR cells (left). Flow-cytometric analysis of the frequency of TOX-expressing cells in the indicated cell types in the B16F10-OVA model at day 14 (right; n = 10 mice per group). d, Mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) immunized with OVA in alum and treated with a complex of IL-2 and anti-IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) on days 3, 4 and 5 for in vivo TREG cell expansion. Representative FACS plots characterizing splenic TREG (CD4+CXCR5−CD25+GITR+) and TFR (CD4+CXCR5+CD25+GITR+) cells are shown. e, Representative histogram plots depicting the dilution of CellTrace Violet (CTV) in CD8+ T cells with or without the addition of TREG or TFR cells. c–e, The percentages of cells in each quadrant (c) or in the outlined regions (d,e) are shown. f, Flow-cytometric analysis of an in vitro proliferation assay showing the frequency of proliferating CD8+ T cells when co-cultured with different proportions of TREG or TFR cells. Results for n = 3 technical replicates for the dilutions and n = 4 technical replicates for CD8+ T cells (1:0 dilution) are depicted. g, Concentration of secreted IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNF in the supernatants of the in vitro proliferation assays in e,f, determined using Luminex analysis; n = 2 technical replicates. h, Fold-change reduction in the secretion of the indicated cytokines between TREG and TFR cells at a 4:1 ratio of CD8+ T cells to either TREG or TFR cells. i, The indicated cells were transferred into B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing Rag1−/− recipient mice on day 3 after tumor inoculation. The tumor volume of the mice treated as indicated is shown (n = 5 mice per group). Data are the mean ± s.e.m.; all data are representative of two independent experiments. Statistical significance for the comparisons was computed using a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001.

We performed in vitro and in vivo functional assays to experimentally validate that TFR cells are more suppressive than TREG cells. Strikingly, we found that TFR cells inhibited CD8+ T cell proliferation more efficiently than TREG cells (Fig. 4d-f and Extended Data Fig. 6b) and also reduced their secretion of the effector molecules interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-2 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) more effectively (Fig. 4g and Extended Data Fig. 6c). Notably, compared with TREG cells, TFR cells reduced the secretion of IFN-γ by CD8+ T cells approximately fourfold and the secretion of IL-2 and TNF by CD8+ T cells by approximately twofold (Fig. 4h). These data demonstrate that TFR cells are highly suppressive and imply that they are able to actively diminish the effector functions of CD8+ T cells, even at low cell numbers. Based on these results, we chose to transfer OT-I T cells—either alone or with TREG or TFR cells at a 4:1 ratio—into B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing RAG1-knockout (Rag1−/−) recipient mice. Although the effect of adoptively transferred TREG cells was negligible, TFR cells substantially inhibited OT-I T cell-mediated tumor rejection (Fig. 4i), demonstrating that TFR cells exhibit superior suppressive potential in comparison to TREG cells.

Intratumoral TFR cells increase over time.

To further characterize the properties of intratumoral TREG and TFR cells, we barcoded tumor-infiltrating FOXP3-expressing CD4+ T cells from individual B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing FOXP3–red fluorescent protein (RFP) reporter mice from an early (day 11) and late (day 18) stage of tumor development and subjected them to 10x Genomics-based single-cell RNA-seq. Analyses using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) identified five clusters (Fig. 5a) with distinct transcriptomic signatures (Fig. 5b), implying the existence of multiple TREG cell subsets in the tumor tissues. Importantly, all clusters were present at both time points but only the cells in cluster 2 were enriched in the tumor samples from day 18 (later time point; Fig. 5a,c). Gene-set enrichment analyses showed that the cells in cluster 2 were significantly enriched for signatures linked to T cell activation (Fig. 5d), TFH and TFR cells (Fig. 5e), and hence depict activated TFR cells, suggesting that TFR cells increase in tumors over time. Single-cell differential gene expression analysis highlighted profound differences in the transcriptome of TFR (cluster 2) and TREG cells in the other clusters (Fig. 5f). In line with our previous data (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e), TFR cells exhibited increased expression of TFR signature genes (that is, Pdcd1 and Tnfrsf18), genes involved in TCR signaling (Cd3g, Cd3d, Cd3e and Lck) as well as several genes that are associated with heightened functionality (that is, Tnfrsf1b16,33, Tigit18, Tnfrsf9 (ref. 29), Lag3 (ref. 17) and Tox32) or suppressive capacity (Tgfb1), indicative of an activated phenotype and further suggestive of their suppressive potential. TFR cells also displayed a significant decrease in the expression of genes that encode receptors required for tissue egress (S1pr1 and Klf2), suggesting that they may possess greater tumor-residency properties in comparison to other TREG subsets. (Fig. 5f,g). As in our previous analyses (Extended Data Fig. 5a,c), we found substantial clonal overlap between TREG and TFR cells (Fig. 5h). Finally, cell-trajectory analysis pointed to a developmental path from cells in cluster 0, which exhibit features of naive recirculating TREG cells (Fig. 5g), to TFR cells (Fig. 5i), further corroborating our previous data (Extended Data Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 5d). Together, these data, in addition to highlighting the transcriptional properties of TFR cells, establish a clonal and developmental relationship between TREG and TFR cells and are further indicative of intratumoral TREG-to-TFR conversion. Based on these findings, we performed a time-course experiment, which confirmed that the proportion of intratumoral TFR cells, but not TREG cells, increased with tumor progression (Extended Data Fig. 6d), probably a reflection of ongoing TREG-to-TFR conversion and the higher proliferative potential of TFR cells. Murine tumor-infiltrating TFR cells also exhibited higher expression of CTLA-4 and PD-1 compared with TREG cells (Fig. 5j), implying that such murine tumor models would be appropriate to test the hypothesis that anti-PD-1 therapy increases the numbers and/or function of highly suppressive TFR cells, inducing a profoundly immunosuppressive tumor milieu. Given that PD-1−/− mice exhibit increased levels of TFR cells in secondary lymphoid organs5, we reasoned that PD-1 signaling is likely to restrain the expansion of TFR cells.

Fig. 5 ∣. Intratumoral TFR cells gradually increase over time.

a, Analysis of 10x Genomics single-cell RNA-seq data. Seurat clustering of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3-expressing T cells colored according to the cluster type. UMAPs of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3-expressing T cells on days 11 (left) and 18 (middle). The proportion of cells in individual mice, (i)–(iv), at the indicated time points are shown (right). The percentage of cells in cluster 2 (TFR cells) is depicted. b, Heatmap showing genes that are enriched in the identified clusters. Transcripts with a significant change in expression (>twofold and adjusted P ≤ 0.05) are depicted. c, Proportion of cells in each cluster, colored according to the developmental stage of the tumor. d,e, Gene-set enrichment analysis for a T cell activation signature (d) as well as TFH44 (e; derived from Extended Data Fig. 2a-e) and TFR (e; derived from Fig. 2j and Extended Data Fig. 2a-e) signature genes for the cells in cluster 2 versus the other clusters, ordered by the log2-transformed fold change. f, Volcano plot of cells in cluster 2 versus the other clusters. Differentially expressed transcripts (adjusted P ≤ 0.05) that change in expression more than twofold are depicted. FDR, false discovery rate; dashed lines depict the threshold used for fold change and FDR. g, Average transcript expression (color scale) and percentage of expressing cells (size scale) for select genes in each cluster. h, Euler diagram showing the overlap between the clonotypes in cluster 2 and the other clusters. i, Single-cell pseudotime trajectory analysis of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3-expressing T cells (a) constructed using the Monocle3 algorithm. j, Flow-cytometric analysis depicting the MFI of the expression of PD-1 (P = 0.002) and CTLA-4 (P = 0.002) in the indicated cell types in the B16F10-OVA model on day 14 after tumor inoculation. Representative histogram plots are displayed. Data are the mean ± s.e.m.; data are representative of two independent experiments. Statistical significance of the comparisons was computed using a two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test; **P < 0.01.

TFR cells are responsive to anti-PD-1 therapy.

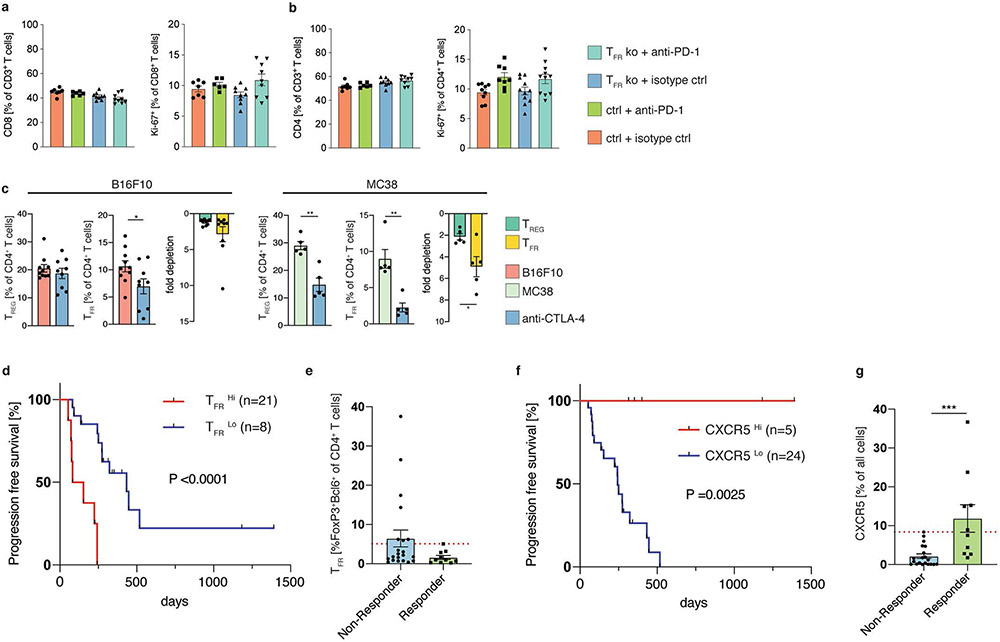

Anti-PD-1 monotherapy resulted in a significant increase in the frequency of TFR cells in both the MC38 and B16F10 tumor models (Fig. 6a), suggesting that tumor-infiltrating TREG (and TFR) cells are highly responsive to blockade of PD-1 signaling, potentially reducing their activation threshold and thus facilitating increased proliferation and differentiation into TFR cells. By re-analyzing published single-cell RNA-seq data from patients receiving anti-PD-1 therapy, we found that the tumor-infiltrating TFR cells from post-treatment samples were enriched for transcripts linked to T cell activation and co-stimulation compared with the pretreatment samples (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Together, these data suggest that engagement of suppressive TFR cells by anti-PD-1 therapy is likely to diminish its antitumor efficacy. To uncouple the effects of TREG and TFR cells on antitumor immunity and the efficacy of anti-PD-1 treatment, we utilized a genetic knockdown system in which TFR cells can be selectively depleted. Tamoxifen-induced depletion of TFR cells in female heterozygous Foxp3eGFP–cre-ERT2cre/wt × Bcl6fl/fl mice34 before the initiation of anti-PD-1 therapy significantly decreased tumor growth, demonstrating that TFR cells curtail the efficacy of the anti-PD-1 treatment (Extended Data Fig. 7b). In this system, half of the FOXP3+ cells should express the Foxp3eGFP–cre-ERT2 allele (enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)+ and BCL-6-deficient) due to random X chromosome inactivation. Surprisingly, although we found a decrease in TFR cells (Extended Data Fig. 7c), we observed a near total loss of BCL-6-deficient eGFP+ TREG cells in the TME (Extended Data Fig. 7d), whereas the frequency of FOXP3-expressing cells only decreased slightly (Extended Data Fig. 7e). These findings were further corroborated in a control experiment by assessing the tumor growth and cell frequencies of homozygous Foxp3eGFP–cre-ERT2 and heterozygous Foxp3eGFP–cre-ERT2/wt (BCL-6-sufficient) mice (Extended Data Fig. 7f-i). Crucially, these data imply that even a partial TFR cell depletion decreases tumor growth and that BCL-6 expression in FOXP3+ cells is likely to be required for their intratumoral persistence. These findings raise several distinct conclusions explaining the accumulation of eGFP−FOXP3+ cells: (1) BCL-6 deficiency affects trafficking of TREG cells into tumor tissue, (2) a lack of BCL-6 expression precludes the adoption of a tissue-residency program and (3) BCL-6-deficient TREG cells are being outcompeted by their BCL-6-sufficient counterparts. Although we cannot formally rule out any of these possibilities, the latter hypothesis is supported by our previous observations of increased proliferative potential as well as higher expression of TOX and TCF-1 by BCL-6+ TFR cells compared with BCL-6− TREG cells.

Fig. 6 ∣. TFR cells are highly responsive to ICB.

a, Mice were s.c. inoculated with B16F10-OVA or MC38-OVA cells and treated with anti-PD-1 at the indicated time points. Flow-cytometric analysis of the frequency of tumor-infiltrating TREG and TFR cells as well as fold induction of both cell types following anti-PD-1 therapy in the B16F10-OVA model (left; n = 9 mice per group) and MC38-OVA (right; n = 5 mice per group) model. b,c, Foxp3YFP–cre/YFP–cre Bcl6fl/fl (TFR knockout) and Foxp3YFP–cre/YFP–cre Bcl6+/+ control mice were s.c. inoculated with B16F10-OVA cells and treated with isotype control or anti-PD-1 at the indicated time points. Tumor volume (b) and frequency of granzyme B (GzmB)+CD8+ T cells in the tumor-draining lymph nodes of the mice (c); n = 7–9 mice per group. d, Mice were i.p. immunized with OVA in alum and additionally treated with an IL-2/anti-IL-2R complex at days 3, 4 and 5. OT-I CD8+ T cells and eGFP+ and YFP+ TREG cells were adoptively transferred into B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing Rag1−/− mice on day 3 after tumor inoculation. Representative contour plots and the frequencies of eGFP and YFP cells in the spleen (left; P = 0.007) and tumor tissue (right; P = 0.0006) are shown for n = 7 mice. e, Flow-cytometric analysis of BCL-6 expression in splenic CD4+FOXP3+ cells of Foxp3YFP–cre × Bcl6fl/fl and Foxp3eGFP mice as well as tumor-infiltrating CD4+FOXP3+ cells 13 days after adoptive transfer into B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing Rag1−/− mice. f, Mice were i.p. immunized with OVA in alum and additionally treated with an IL-2/anti-IL-2R complex at days 3, 4 and 5. OT-I CD8+ T cells and RFP+ and YFP+ TREG cells were adoptively transferred into B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing Rag1−/− mice on day 3 after tumor inoculation. Representative contour plots and the frequencies of RFP+ and YFP+ cells in the spleen (left; P = 0.0087) and tumor tissue (right; P = 0.0022) are shown for n = 6 mice per group. d,f, The numbers in the contour plots indicate the percentage of cells in the outlined areas. Data are the mean ± s.e.m.; all data are representative of two independent experiments. Statistical significance was computed using a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (a,b,d,f) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing the mean of each group with the mean of the control group (control + anti-PD-1), followed by Dunnett’s test (c); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

To assess the functional importance of TFR cells in tumor development and further corroborate that TFR cells impair the efficacy of anti-PD-1 treatment, we utilized TFR cell-deficient Foxp3YFP–cre × Bcl6fl/fl mice35. We chose to test this hypothesis in the B16F10-OVA melanoma model as it is known to be refractory to anti-PD-1 therapy36. Accordingly, anti-PD-1 treatment in the control mice did not impact tumor growth (Fig. 6b). Conversely, we found a trend towards lower tumor volume (isotype control) in the TFR-knockout mice, which was significantly reduced by anti-PD-1 therapy (Fig. 6b), demonstrating that TFR cells inhibit the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. We also assessed tumor-draining axillary and inguinal lymph nodes to further explore the potential impacts of a lack of TFR cells on antitumor immunity in this setting. The frequency and proliferative capacity of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in the tumor-draining lymph nodes were similar between the treatment groups (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). However, akin to our previous findings demonstrating that TFR cells can inhibit CD8+ T cell activity and cytokine secretion (Fig. 4g,h), we found that TFR cell deficiency resulted in increased granzyme B expression in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6c). Together, these data suggest that TFR cells inhibit CD8+ T cell activity in tumor-draining lymph nodes.

To experimentally validate that TFR cells have greater in vivo persistence in tumor tissue, we performed a competition assay in which we co-transferred FOXP3+eGFP+ cells from Foxp3eGFP mice (capable of producing BCL-6) and FOXP3+–yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)+ cells from Foxp3YFP–cre × Bcl6fl/fl mice (incapable of producing BCL-6) at a 1:1 ratio. Strikingly, FOXP3+YFP+ cells failed to accumulate in the spleen and TME (Fig. 6d) of the B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing Rag1−/− mice, demonstrating that FOXP3+BCL-6+ cells (TFR cells) are better suited to survive in the TME. Importantly, the transferred tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ cells expressed substantially higher levels of BCL-6 compared with the pre-transfer levels, indicative of TREG-to-TFR conversion either inside or outside the tumor (Fig. 6e), corroborating our previous findings (Extended Data Fig. 5a-c). As it is contentious whether the Foxp3–YFP–cre allele should be considered hypomorphic37,38, which might account at least partially for the observed phenotype, we performed a control experiment with FOXP3+YFP+ cells from Foxp3YFP–cre mice (no Bcl6 floxed allele). In this control setting, we found that FOXP3+YFP+ cells accumulated in the spleen and TME, albeit at slightly lower levels than the FOXP3+RFP+ cells from Foxp3RFP mice (Fig. 6f). Although these data imply that the knock-in of the YFP–cre fusion protein might impact FOXP3 expression or cell functionality, they importantly verify that BCL-6 expression is required for the persistence of FOXP3-expressing cells in tumors.

Sequential ICB is beneficial in patients with melanoma.

As our findings demonstrated that TFR cells curtail the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 7b), we reasoned that it may be necessary to deplete TFR cells in the tumor before initiating anti-PD-1 therapy to overcome the suppressive milieu induced by an anti-PD-1-mediated increase in TFR cells. Anti-CTLA-4 treatment is believed to deplete intratumoral TREG cells via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity39. Given that the tumor-infiltrating TFR cells expressed higher levels of CTLA-4 than TREG cells in both human and mouse cells, we hypothesized that TFR cells should be more efficiently depleted. Anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy indeed resulted in increased depletion of TFR cells compared with TREG cells (Extended Data Fig. 8c). These data also indicate that immunotherapy drugs elicit immediate effects on the target-cell populations and rapidly re-shape the cellular composition within the TME. Based on these results and our previous findings, we reasoned that sequential ICB treatment (where TFR cells are initially depleted by anti-CTLA-4) might prove beneficial, as subsequent anti-PD-1 therapy would not activate suppressive cellular targets (TFR cells) but would instead engage CD8+ TILs to enhance antitumor immune responses. As before, we tested this in the B16F10-OVA melanoma model, which is refractory to anti-PD-1 therapy36. As expected, monotherapy with either anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-1 did not impact tumor growth, whereas depletion of TFR cells with anti-CTLA-4, followed by anti-PD-1 therapy led to a significant reduction in tumor volume (Fig. 7a). Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that anti-PD-1 therapy increasingly acted on and hence, elevated the frequency of CD8+ TILs after TFR cells had been depleted by anti-CTLA-4 treatment, and also led to an increase in the frequency of granzyme B+ CD8+ and CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7 ∣. Clinical benefit of sequential ICB.

a–c, Mice were s.c. inoculated with B16F10-OVA cells and treated with anti-CTLA-4 (days 10 and 13; n = 8 mice), anti-PD-1 (days 14 and 17; n = 10 mice), anti-CTLA-4 (days 10 and 13) and anti-PD-1 (days 14 and 17; n = 8 mice), or isotype control at the respective time points (n = 13 mice). a,b, Tumor volume (a) and cell frequencies (b) of the mice treated as indicated. Data are the mean ± s.e.m. and are representative of two independent experiments. Not significant, P = 0.1234; *P = 0.0332; ***P = 0.0002; and ****P < 0.0001. c, Survival curves of an independent cohort of patients with melanoma (n = 271) stratified into five groups based on the ICB treatment regimen. d,e, Survival curves for patients with early onset (d; M1a and M1b combined) and late-stage (e; M1c and M1d combined) disease and according to their BRAF-mutation status (f). Statistical significance was computed using a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (a); one-way ANOVA to compare the mean of each group with the mean of the control group (B16F10), followed by a Dunnett’s test (b) or Mantel–Cox test (c–e).

To test the clinical significance of sequential ICB treatment, we retrospectively assessed the survival outcome of patients with inoperable melanoma (n = 271), who were stratified into five groups based on their treatment regimens: first-line anti-CTLA-4; first-line anti-PD-1; simultaneous combination therapy; sequential therapy with anti-CTLA-4, followed by anti-PD-1 at progression and sequential therapy with anti-PD-1, followed by anti-CTLA-4. Sequential treatment with anti-CTLA-4, followed by anti-PD-1 was associated with better long-term overall survival outcomes compared with the four other groups (P < 0.001; Fig. 7c). It has to be noted though that the patients receiving simultaneous ICB therapy exhibited a more advanced disease before treatment initiation (higher proportion with AJCC 8 stage M1c and M1d (n = 75) than patients on the first-line anti-PD-1 (n = 70) or anti-CTLA-4 (n = 52) treatments (Fig. 7d,e), which probably contributed to their poor overall survival outcomes. However, the advantageous effect of anti-CTLA-4, followed by anti-PD-1 therapy was preserved in patients with M1a and b, and M1c and d, respectively (Fig. 7d,e), indicating that this treatment regimen is clinically beneficial even in patients with a very poor prognosis. Differences in BRAF status did not affect the ICB treatment outcomes (Fig. 7f). Our outcome data for patients receiving first-line anti-CTLA-4 treatment seem to be superior to those in a recently published study40; however, the two studies are not directly comparable, as the proportion of patients going on to receive second-line anti-PD-1 treatment was substantially lower in the former trial (43 versus 63%). Crucially and in agreement with our findings in mouse models (Fig. 7a,b), compared with anti-PD-1 monotherapy, sequential treatment with anti-CTLA-4 (probably depletes TFR cells in the tumor or blocks their activity), followed by anti-PD-1 was associated with significantly better survival outcomes (P = 0.0003; Fig. 7c-e).

In an independent cohort of patients with melanoma (n = 29) who received anti-PD-1 treatment, we observed poor survival outcomes in patients with a higher proportion of CD4+ T cells co-expressing FOXP3 and BCL-6 (BCL-6+ TFR cells) in tumors (Extended Data Fig. 8d) and also noticed a trend towards a higher frequency of TFR cells (BCL-6+FOXP3+CD4+ T cells) in non-responders compared with responders to anti-PD-1 treatment (Extended Data Fig. 8e). A lower frequency of CXCR5+ cells (Extended Data Fig. 8f), a surrogate marker for the abundance of TLS, was also associated with poor survival outcomes (Extended Data Fig. 8g), consistent with recently published studies11-13. Given that TFR cells have been shown to mitigate germinal center responses in secondary lymphoid organs, it is tempting to assume that TFR cells might not only impede antitumor immunity by inhibiting CD8+ TILs but also by regulating TLS in tumor tissues, which should be investigated in future studies.

Discussion

TREG cells impede antitumor immunity and are thus detrimental to patient survival. In non-cancer settings, TREG cells have been shown to differentiate into PD-1-expressing TFR cells that restrain germinal center responses by suppressing germinal-center B cells and stimulatory TFH cells2,41. Both TFH and TFR cells constitutively express high levels of the co-inhibitory receptors PD-1, yet few studies have investigated their impact on antitumor immunity and their responsiveness to anti-PD-1 therapy. Although recent studies have demonstrated that TFH and B cells, and TLS are associated with the survival and responsiveness to immunotherapy of patients11-14, the precise mechanism, potential cell–cell interactions, drivers and regulators of TLS formation or maintenance, and the importance of specific B and T cell subsets remain unknown.

Here we provide the first in-depth analysis of tumor-infiltrating TFR cells and elucidate their responsiveness to ICB and the context in which they exert their suppressive functions. TFR cells were prevalent in tumor tissues of several cancer types and exhibited a superior suppressive capacity and in vivo persistence in comparison to TREG cells, with which they shared a clonal and developmental relationship. This developmental relationship between intratumoral TREG and TFR cells was characterized by substantial TCR sharing and a gradual increase in TFR cells over time, which together with the single-cell-trajectory analyses and adoptive transfer studies implies ongoing TREG-to-TFR conversion. Crucially, unlike TREG cells, TFR cells were preferentially located in TLS, and among tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, TFR cells expressed the highest levels of CTLA-4 and PD-1. Given that TFR cells mitigate germinal center responses in secondary lymphoid organs2,41, our finding that TFR cells are enriched in TLS suggests that intratumoral TFR cells might also regulate TLS formation and maintenance, potentially by controlling B or TFH cell responses, which should be tested in future studies.

Our findings in murine tumor models indicate that intratumoral TFR cells are responsive to ICB and that by increasing the abundance of TFR cells, anti-PD-1 therapy can both facilitate and dampen antitumor immune attack. We provide critical insights into how anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 therapies mediate their function and highlight the clinical benefit of sequential dosing to render tumors responsive to anti-PD-1 therapy, a hypothesis that merits further investigation in a randomized clinical trial. The well-described clinical scenario in which some tumors hyper-progress following anti-PD-1 therapy42,43 may be explained by the effects of treatment on a highly suppressive immune-cell compartment (TFR cells), especially in patients with an initially high level of tumor-specific TREG (TFR precursor) cells. Conversely, exacerbated immune-related adverse events observed following combination therapy might be caused by anti-CTLA-4-mediated depletion or impairment of the activity of FOXP3-expressing cells in multiple tissues and subsequent uninhibited anti-PD-1-mediated activation of effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, hypotheses that can be addressed in future studies. Finally, our results implicate the unique composition of stimulatory versus suppressive T cells in the TME of each patient, as well as their differentiation status (that is, PD-1 expression levels and frequency of TFR cells in CD4+ T cells), as important immunological determinants driving the efficacy of anti-PD-1 treatment.

Methods

Human tumor samples.

The study was approved by the Southampton and South West Hampshire Research Ethics Board (ethics committee MREC number 14/SC/0186, NIHR portfolio adoption ID 16818), and written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants. Newly diagnosed, untreated patients with NSCLC (or HNSCC) were prospectively recruited once referred. Freshly resected tumor tissue was obtained from patients with lung cancer following surgical resection and after histological confirmation. The patient cohort for the survival analysis was collected by retrospective evaluation of a centralized prescribing system (Aria, Varian Medical Systems Inc.). All of the patients started on immunotherapy at a single institution (Southampton University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust), with immunotherapy for melanoma administered between July 2014 and October 2018. The patients were divided into cohorts according to the first type immunotherapy treatment approved in the United Kingdom: anti-PD-1, either nivolumab or pembrolizumab (n = 98); anti-CTLA-4, ipilimumab (n = 88); or joint administration of nivolumab plus ipilimumab on up to four occasions (n = 85), followed by maintenance nivolumab where appropriate. Dosing was according to the standard of care at the time (3 mg kg−1 ipilimumab × 4; 2 mg kg−1 pembrolizumab three times a week, 200 mg flat dosing later; 3 mg kg−1 nivolumab, then 480 mg flat dosing; and in combination 3 mg kg−1 ipilimumab + 1 mg kg−1 nivolumab × 4, followed by 3 mg kg−1 nivolumab). All patients who had at least one dose of immunotherapy were included. Clinical data were obtained from an electronic hospital record for age, gender, BRAF status, lactate dehydrogenase, M stage and performance status. For clinical outcome, overall survival was collected to death or censored at last clinical review. Data were anonymized by the treating clinician (I.K. and C.H.O.) once the data had been collated and verified. Prism 8 (GraphPad Software) was used for ANOVA analysis, to plot Kaplan–Meier survival graphs and estimate treatment differences using a log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test on the survival curves. SPSS v26 (IBM Corp.) was used to evaluate imbalances between the treatment groups via χ2 testing, followed by Cox regression analysis. Fur multiple testing a Bonferroni error correction was applied.

Mice.

C57BL/6J (stock no. 000664), Bcl6fl/fl (stock no. 023727), OT-I (stock no. 003831), Rag1−/− (stock no. 002216) and Foxp3YFP–cre (stock no. 016959) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Foxp3eGFP–cre-ERT2 (JAX, stock no. 016961) and Foxp3RFP (JAX, stock no. 008374) mice were a gift from K. Ley (LJI), and Foxp3eGFP (JAX, stock no. 006772) mice were a gift from A. Altman (LJI). Female mice (6–12 weeks old) were used for all experiments. The housing temperature in the vivarium was controlled and kept within the range of 20–24 °C; humidity was not controlled but it was monitored and ranged from 30 to 70%. The mice were maintained in 12-h light–dark cycles (06:00–18:00 light). All animal work was approved by the relevant La Jolla institute for Immunology Animal Ethics Committee.

Tumor cell lines.

The B16F10-OVA cells were a gift from the J. Linden laboratory (LJI) and the MC38-OVA cells were a gift from the S. Fuchs laboratory (UPenn). The cells were approved for use by M. Smyth (Peter MacCallum cancer center). The cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma infection and were subsequently treated with Plasmocin (InvivoGen) to prevent contamination.

Tumor models.

The tumor cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma infection and Plasmocin (InvivoGen) was used as a routine addition to the culture media to prevent mycoplasma contamination. The mice were inoculated with 1–1.5 × 105 B16F10-OVA cells or 2 × 106 MC38-OVA cells s.c. into the right flank. The mice were i.p. injected at the indicated time points with either 200 μg anti-PD-1 (29F1. A12, InVivoPlus anti-mouse PD-1, Bioxcell), anti-CTLA-4 (9H10, InVivoPlus anti-mouse CTLA-4, Bioxcell) or the respective isotype controls (anti-CTLA-4 isotype control, InVivoPlus polyclonal Syrian hamster IgG, Bioxcell; anti-PD-1 isotype control, InVivoPlus rat IgG2a isotype control, anti-trinitrophenol, Bioxcell). Tumor size was monitored every other day and tumors were harvested at the indicated time points for the analysis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Tumor volume was calculated as ½ × D × d2, where D is the major axis and d is the minor axis, as described previously45. Tumor growth was monitored at least three times a week to ensure that the tumors did not exceed 25 mm in diameter.

Suppression and competition assay.

Mice were i.p. immunized with OVA in alum (100 μg in 100 μl sterile PBS mixed with 100 μl of 2% alum). The mice were i.p. immunized with an IL-2/anti-IL-2R complex (1 μg IL-2 and 5 μg anti-IL-2R, mixed for 30 min at 37 °C) 3–5 days after immunization to achieve polyclonal expansion of TREG cells in vivo, as described previously46. Lymphocytes (CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) were isolated from the spleen by mechanical dispersion through a 70-μm cell strainer (Miltenyi) to generate single-cell suspensions. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were purified (Stemcell) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro assays.

CD8+ T cells were labeled with CellTrace Violet (ThermoFisher) and 40,000 cells were added to 96-well cell-culture plates (pre-coated with anti-CD3) in 200 μl complete RPMI medium. Purified CD4+ T cells were stained and different numbers of viable (fixable viability dye) TREG cells (CD4+CXCR5−CD25+GITR+) or TFR cells (CD4+CXCR5+CD25+GITR+) were sorted into the cell-culture plate containing the CellTrace Violet-labeled CD8+ T cells. CD8+ T cell proliferation (CellTrace Violet dilution) was determined three days later.

In vivo assays.

OT-I CD8+ T cells were purified (Stemcell). CD4+ T cells were purified and stained, and TREG and TFR cells were sorted as described above. The cells were counted and 2 × 105 OT-I T cells, 2 × 105 OT-I T cells + 5 × 104 TREG cells (4:1 ratio) or 2 × 105 OT-I T cells + 5 × 104 TFR cells (4:1 ratio) were adoptively transferred into B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing Rag1−/− recipient mice three days after the tumor inoculation.

Competition assay.

OT-I CD8+ T cells were purified (Stemcell). FOXP3+ T cells were purified from Foxp3YFP–cre × Bcl6fl/fl (YFP+) and Foxp3eGFP (eGFP+) mice or from Foxp3RFP mice for the control experiments, and 4 × 105 cells (2 × 105 OT-I T cells, 1 × 105 eGFP+ or RFP+ TREG cells and 1 × 105 YFP+ TREG cells) were adoptively transferred into B16F10-OVA tumor-bearing Rag1−/− recipient mice three days after the tumor inoculation.

Flow cytometry.

T cells from cryopreserved tumor tissue were mechanically dissociated and enzymatically digested as previously described47. The cells were treated with FcR blocking antibody (BD Biosciences) and stained in PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM EDTA for 30 min at 4 °C. Secondary stains were performed for selected markers. The samples were subsequently sorted or fixed for intracellular staining using the FOXP3 TF kit (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For all staining, cell viability was verified using fixable viability dye (ThermoFisher).

Murine samples.

Lymphocytes were isolated from the spleen by mechanical dispersion through a 70-μm cell strainer (Miltenyi) to generate single-cell suspensions. Red-blood-cell lysis (BioLegend) was performed to remove the red blood cells. Tumor samples were harvested and lymphocytes were isolated by dispersing the tumor tissue in 2 ml PBS, followed by incubation of the samples at 37 °C for 15 min with DNase I (Sigma) and liberase DL (Roche). The samples were passed through a 70-μm cell strainer to create single-cell suspensions. The cells were prepared in staining buffer (PBS with 2% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM EDTA), FcR blocked (clone 2.4G2, BD Biosciences) and stained with the indicated primary antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C; secondary stains were conducted for selected markers. The samples were then sorted or fixed and intracellularly stained using a FOXP3 transcription factor kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (eBioscience). Cell viability was determined using fixable viability dye (ThermoFisher). For the bulk RNA-seq analyses, we sorted tumor-infiltrating TFR cells based on the co-expression of CXCR5 and GITR2,5 (Extended Data Fig. 1b), a surface marker that distinguishes TFH cells from TFR cells. To accurately assess the expression of intracellularly stored molecules like CTLA-4, we characterized TFR cells on the basis of co-expression of BCL-6 and FOXP3 (Extended Data Fig. 1c) as cell fixation led to epitope masking of CXCR5 (Extended Data Fig. 1c, bottom left) and GITR. All samples were acquired on a BD FACS Fortessa system or sorted on a BD FACS Fusion system (both BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo 10.4.1.

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

The primary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry included anti-CD8 (pre-diluted; C8/144B, Agilent Dako), anti-CD4 (1:100; 4B12, Agilent Dako), anti-FOXP3 (1:100; ab20034, Abcam), anti-CXCR5 (1:50; D6L3C, Cell Signaling), anti-BCL-6 (1:30; NCL-L-Bcl6-6-564, Leica), anti-CD31 (pre-diluted product diluted further 1:5; Agilent Dako) and anti-PanCK (AE1/AE3; pre-diluted; Agilent Dako). The samples for the immunohistochemical analyses were prepared, stained and analyzed as previously described48. Cells were identified by nucleus detection and cytoplasmic regions were simulated up to 5 μm per cell; protein expression was measured using the mean staining intensity within the simulated cell regions.

Bulk RNA-seq.

Total RNA was purified from human tumor-infiltrating TREG (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5−CD127−CD25+) and TFR (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5+GITR+) cells using a miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) and quantified as described previously47,49. Cells from mice immunized with either OVA in Complete Freund’s adjuvant (InvivoGen), OVA in monophosphoryl lipid A (InvivoGen) or mock PBS—TEFF (CD19−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5−GITR−CD25−CD62L−CD44+), TREG (CD19−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5−GITR+CD25+), TFH (CD19−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5+GITR−) and TFR (CD19−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5+GITR+)—were sorted and RNA was purified as described above. RNA-seq libraries were prepared using Smart-seq2 protocol and sequenced on an Illumina platform, as previously described50. Quality-control steps were applied as previously described47. Samples that failed the quality controls or that had a low number of cells were excluded from further sequencing and analysis.

Bulk RNA-seq analysis.

Bulk RNA-seq data from human samples were mapped against the hg19 reference using TopHat51 (--bowtie1 –max-multihits 1 –microexon search) with FastQC (v0.11.2), Bowtie (v1.1.2)52 and Samtools (v0.1.19.0)53, and we employed htseq-count -m union -s no -t exon -i gene_name (part of the HTSeq framework, version v0.7.1)54. Trimmomatic (v0.36) was used to remove adapters55. Bulk RNA-seq from mouse samples were mapped against the mm 10 reference using TopHat (1.4.1) with the library-type fr-unstranded parameter. Values are displayed as log2-transformed TPM counts throughout; a value of one was added before the log transformation. To identify genes that were differentially expressed by various cell types, we performed negative binomial tests for unpaired comparisons by employing the Bioconductor package DESeq2 (v1.14.1)56, disabling the default options for independent filtering and Cooks cutoff. We considered genes to be expressed differentially in any comparison when the DESeq2 analysis resulted in a Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P ≤ 0.05 and a fold change of at least two. Euler diagrams were generated using the eulerr package (v5.1.0). Correlations and heatmaps were generated as previously described47,49,57. Visualizations were generated in ggplot2 using custom scripts. For t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding analysis, the data frame was filtered to genes with mean ≥ 1 TPM counts expression in at least one condition and visualizations were created using the top-500 most variable genes, as calculated in DESeq2 (v1.16.1)56; this allowed for unbiased visualization of the log2(TPM count + 1) data using the package Rtsne (v0.13). Data in heatmaps are shown as log2-normalized z-scores.

WGCNA.

WGCNA was completed in R (v.3.5.0) using the package WGCNA (v1.61) and the TPM data matrix. Well-expressed genes with TPM ≥ 10 in at least one sample were used in the human TFR and TREG data. Gene modules were generated using the blockwiseModules function (parameters: checkMissingData = TRUE, power = 5, TOMType = ‘signed’, minModuleSize = 30, maxBlockSize = 13,441 and mergeCutHeight = 0.80). The remaining parameters were as per the default in WGCNA. The default ‘gray’ module generated by WGCNA for genes that were not co-expressed was excluded from further analysis. As each module is by definition comprised of highly correlated genes, their combined expression may be usefully summarized by module eigengene profiles, effectively the first principal component of a given module. A small number of module eigengene profiles may effectively ‘summarize’ the principal patterns in the transcriptome with minimal loss of information. This dimensionality reduction approach aids the correlation of module eigengenes with clinical traits as a module–trait relationship matrix. Significance of the correlation between this trait and module eigengenes was assessed using linear regression with Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment to correct for multiple testing. The TOMplot was generated using the TOMplot function in WGCNA with default parameters for clustering and color scheme. To visualize co-expression, networks were generated in gplots (v3.0.1) using the heatmap2 function, while weighted correlation analysis was completed using WGCNA58 (v1.61) from the log2(TPM count + 1) data matrix and the functions ‘TOMsimilarityfromExpr’ (Beta = 5) and ‘exportNetworkToCytoscape’ (weighted = true and threshold = 0.05). Highlighted genes were ordered as per the order in the correlation plot. Networks were generated in Gephi (v0.92)59,60 using the ForceAtlas2 and Noverlap functions. Color and size were scaled to the ‘Average Degree’ calculated in Gephi. Edge width was scaled to the WGCNA edge weight value.

Meta-analysis of published single-cell RNA-seq studies.

We integrated nine published single-cell RNA-seq datasets20,26,61-67 of tumor-infiltrating CD4-expressing T cells with UMAP. The integration was performed using the R package Seurat v3.0. For each dataset, cells that expressed fewer than 200 genes were considered outliers and discarded. We integrated data from all cohorts using the alignment by the ‘anchors’ option in Seurat 3.0. Briefly, the alignment is a computational strategy to ‘anchor’ diverse datasets together, facilitating the integration and comparison of single-cell measurements from different technologies and modalities. The ‘anchors’ correspond to similar biological states between datasets. These pairwise correspondences between datasets allows the transformation of datasets into a shared space regardless of the existence of large technical and/or biological divergences. This improved function in Seurat 3.0 allows integration of multiple RNA-seq datasets generated by different platforms68. Although we agree that single-cell RNA-seq can be utilized to identify distinct states in a given cell population, it does not offer higher resolution compared with bulk RNA-seq in terms of the number of transcripts recovered due to high drop-out rates with single-cell RNA-seq assays, more so with 10x Genomics sequencing-based assays. We used the FindIntegrationAnchors function to find correspondences across the different study datasets with default parameters (dimensionality = 1:30). Furthermore, we used the IntegrateData function to generate a Seurat Object with an integrated and batch-corrected expression matrix. In total, 25,149 cells and 2,000 most variable genes were used for clustering. We used the standard workflow from Seurat, scaling the integrated data, finding relevant components with principal-component analysis and visualizing the results with UMAP. The number of relevant components was determined from an elbow plot. UMAP dimensionality reduction and clustering were applied with the following parameters: 2,000 genes; 15 principal components; resolution, 0.2; min. dis, 0.05 and spread, 2. The cells that were used for the integration were selected from clusters labeled in the original studies as tumor CD4+ T cells and from pretreatment samples when necessary. Cells with CD8B expression > 1 CPM (UMI data) or 10 TPM (Smart-seq2) were filtered out. TREG and TFR cells were identified based on the criteria defined in the source data for Fig. 1. Only Smart-seq2 datasets were used to compare TFR cells from different cancer types.

Single-cell differential expression analysis.

Differential expression was calculated using MAST69 and SCDE70 (v1.99.1) as previously described57. For each comparison, we obtained the lists of genes that were differentially expressed by taking the union of the gene lists from both methods using adjusted P < 0.05 and log2(fold change) > 1 from each method.

Single-cell TCR and transcriptome analysis.

Single-cell Smart-seq2 data from ref. 20 were re-analyzed using custom scripts to identify α and β chains and show only cells where both TCR chains were detected, as described previously56. Visualizations were completed in ggplot2, Prism (v8.1.1) and custom scripts in TraCer. A cell was considered expanded when both the most highly expressed α and β TCR chain sequences matched other cells with the same stringent criteria. Cells were considered not expanded when the α and β TCR productive chain sequences did not match those of any other cells. A cell was considered a TREG cell when the expression of CD4 and FOXP3 were > 10 TPM and expression of CXCR5 and BCL6 was absent (TPM ≤ 10). A cell was characterized as a TFR cell if the expression levels of CD4 and FOXP3 were > 10 TPM, and the expression of CXCR5 or BCL6 was > 10 TPM. A cell was considered 4-1BB+ when the expression of 4-1BB was > 10 TPM. Cell-state hierarchy maps were generated using Monocle (v3.0)71 and default settings with expressionFamily = negbinomial. size() and lowerDetectionLimit = 0.1 after transformation of the TPM counts with the relative2abs function, as recommended in the manual, including the top-2,000 most variable genes identified in Seurat (v3.0) and taking 14 principal components based on the elbow plot. The shared signature was calculated using the AddModuleScore function from Seurat after setting the object with default parameters and using the intersection of differentially expressed genes from the comparison of 4-1BB− TREG cells with three populations: 4-1BB+ TREG, clonally expanded TREG cells sharing their TCRs with TFR and clonally expanded TFR cells with Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P < 0.05 and a log2 fold change of one. Single-cell Smart-seq2 data from ref. 26 were utilized to compare the single-cell transcriptome of the tumor-infiltrating TFR cells from the samples from before and after anti-PD-1 treatment. Data in the heatmaps are shown as log2-normalized z-scores.

Hierarchical clustering.

The distance between clusters was calculated by obtaining the location of a particular cell in the principal-component-analysis space (principal component 1:5) using the function Embeddings from Seurat. The number of principal components was determined from an elbow plot. A distance matrix was calculated (dist function, core R, method = Euclidean) from the principal-component-analysis matrix and the clustering was performed (hclust function, method = ‘average’) in R and generated from the distance matrix. The function colored_bars from the WGCNA package was used to annotate different groups in the dendrogram.

Single-cell transcriptome analysis of primary tumor tissue and metastatic tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes.

Human T cells from two patients with HNSCC (primary tumor tissue and metastatic tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes) were isolated and prepared as described earlier. CD4+ TH (CXCR5+GITR− and CXCR5−CD25−), TREG (CD4+CXCR5−CD25+CD127lo), TFR (CD4+CXCR5+GITR+) and CD8+CD69+ cells were sorted and complementary DNA libraries were constructed using the standard 10x Genomics sequencing protocol. A total of n = 9,562 (n = 4,975 from metastatic tumor-infiltrated lymph node and 4,589 from primary tumor tissue) cells were sequenced and the cells with fewer than 200 and more than 5,000 expressed genes, less than 15,000 counts and more than 10% mitochondrial counts were filtered out. For clustering with Seurat (3.0), we used 17 principal components from a set of highly variable genes (n = 609) taking 30% of the variance after filtering out genes with a mean expression of less than 0.1 and removing the TCR genes.

TCR analysis.

Clonotype output (clonotypes and filtered contig annotation) from Cell Ranger for tumor and lymph node libraries were re-calculated (matching sequences were assigned the same clonotype ID) and the overlap between clusters 1 and 6 was determined with these ‘aggregated’ tables.

Gene-set enrichment analysis.

The log2-tranformed fold change was used as the ranking metric and enrichment was calculated for each list. The package fgsea (v1.13.0) in R was used with default parameters to calculate the enrichment and create GSEA plots. Monocle (v2.99.1) was used to generate the trajectory plots, reduction_method = DDRTree for the dimensional reduction taking 15 principal components. Hierarchical clustering was performed as stated earlier using 20 principal components.

Single-cell transcriptome analysis of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3-expressing cells.

FOXP3-expressing (RFP+) cells were isolated from tumor tissues at days 11 and 18 after the B16F10-OVA tumor inoculation of Foxp3RFP reporter mice. Four mice from each time point were barcoded with murine Totalseq-C antibodies (BioLegend). Live/Dead−CD19−CD3+CD4+RFP+ cells were sorted and cDNA libraries were constructed using the standard 10x Genomics sequencing protocol. Gene expression, TCR and antibody capture data were processed using Cell Ranger (v3.1.0). The antibody capture data were analyzed using custom scripts (github.com/vijaybioinfo/ab_capture), as previously described72. Analysis of differential gene expression was performed as described earlier. One contaminating cluster exhibiting high expression levels of transcripts associated with non-TREG cells (that is, CD40Lg) was removed before the analysis of the differential gene expression. Finally, the TCR data were analyzed using custom scripts in R taking clone data for each barcode as indicated in the Cell Ranger output. Euler diagrams and enrichment plots were generated using eulerr (v6.1.0) and fgsea (v1.10.1), respectively.

Quantification and statistical analysis.

The number of study participants, samples or mice per group, replicates in independent experiments and statistical tests can be found in the figure legends. Details on quality control, sample elimination and displayed data are stated in the method details and figure legends. Sample sizes were chosen based on published studies to ensure sufficient numbers of mice in each group, enabling reliable statistical testing and accounting for variability. The sample sizes are indicated in the figure legends. Mice that did not develop any tumors by ten days after inoculation, before any therapeutic intervention, were excluded from the analyses. The RNA-seq samples that failed to pass the quality control were not included in the analyses. Experiments were reliably reproduced at least twice in independent experiments. Only female mice were used in the experiments and animals of similar age were randomly assigned to the experimental groups. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 and the statistical tests used are indicated in the figure legends as well as the experimental model and subject details.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 ∣. Selection criteria for the integrated single-cell analysis and gating strategies.

a, Violin plots depicting single-cell expression levels for BCL6, CXCR5 and FOXP3 transcripts (left panel) in tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells of an exemplary dataset61; dotted lines indicate threshold used for defining positive cells. The scatter plot (right panel) shows expression levels of BCL6 and CXCR5 transcripts in FOXP3-expressing CD4+ T cells b, Gating strategy (surface panel) to sort tumor-infiltrating TREG (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5−CD127−CD25+) and TFR (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5+GITR+) cells is shown in the representative FACS plots. c, Gating strategy (intracellular panel) to identify tumor-infiltrating TREG (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5−FOXP3+BCL-6−) and TFR (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+BCL-6+FOXP3+) cells is shown in the representative FACS plots. d, Representative immunohistochemistry staining for one of the ten NSCLC patients in (Fig. 1d-i) is shown, PanCK (white), CD4 (light blue), CXCR5 (yellow), CD20 (magenta) FOXP3 (green) and BCL-6 (red), scale bars are 25 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 2 ∣. Transcriptome analysis of murine TFR cells and characterization of TFR cells in murine tumors.

a, Schematic of immunization model in which mice were immunized intraperitoneally (i.p.) with Ovalbumin in complete Freund’s adjuvant, Ovalbumin in Monophosphoryl Lipid A or mock PBS. b, tSNE plot of TEFF (CD19−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5−GITR−CD25−CD62L−CD44+), TREG (CD19−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5−GITR+CD25+), TFH (CD19−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5+GITR−) and TFR (CD19−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5+GITR+). Each symbol represents data from an individual mouse sample (n = 9 for TEFF, n = 11 for TREG, n = 11 for TFH, n = 11 for TFR) that passed quality controls. c, Euler diagrams show the overlap of differentially expressed genes (left, upregulated in TFR, right, downregulated in TFR) in TFR cells compared to the indicated cell types. d, Heatmap comparing gene signatures of TEFF, TREG, TFH and TFR cells. Depicted are transcripts that change in expression more than 2-fold with a DEseq2 adjusted-P value of ≤ 0.05. e, Log-transformed RNA-seq expression values for each of the indicated differentially expressed genes. Each symbol represents an individual sample, data are mean +/− s.e.m. f, Representative histogram plot showing MFI of the surface expression of indicated markers in human tumor-infiltrating TFR cells (n = 4).

Extended Data Fig. 3 ∣. Transcriptome analysis of human tumor-infiltrating TFR cells.

a, Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) depicted as a Topological Overlap Matrix (TOM) heatmap. It included all genes used in the WGCNA analysis and each row and column correspond to a single gene. Red color indicates the degree of topological overlap. The signed network was generated with bulk RNA-seq data of sorted cells enriched for tumor-infiltrating TREG (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5−CD127−CD25+) and TFR (LIN−CD45+CD3+CD4+CXCR5+GITR+) populations respectively from 10 treatment naïve NSCLC patients (as described in Fig. 2a-d). b, Spearman correlation analysis of the modules identified in (a), depicting module correlation with TFR phenotype. Genes in the pink module are visualized in Gephi, BCL6 and FOXP3 are highlighted. c, Ingenuity pathway analysis of genes in pink module (b). Shown are the top 5 canonical pathways ordered by P value. d, flow cytometric analysis of the frequency (upper panel, P = 0.002 for indicated comparison) and MFI (lower panel, P = 0.002 for indicated comparison) of Ki67-expressing cells, representative histogram plots (right panel) for tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, TREG and TFR cells from n = 10 NSCLC patient samples (described in Fig. 1e,f). e, Heatmap comparing gene expression signatures of enriched population of tumor-infiltrating TREG cells (green) and TFR cells (yellow). Depicted are transcripts that change in expression more than 2-fold with an adjusted-P value of ≤ 0.05. f, Weighted gene co-expression network analysis visualized in Gephi, the nodes are colored and sized according to the number of edges (connections), and the edge thickness is proportional to the edge weight (strength of correlation). The top 10 most differentially expressed genes between TREG and TFR cells are highlighted. g, flow cytometric analysis of the frequency of tumor-infiltrating TCF-1+ TREG and TFR cells from n = 5 NSCLC patient samples, P = 0.0159). Data are mean +/− s.e.m. Significance for comparisons were computed using two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test between TREG and TFR cells (d) or two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (g).

Extended Data Fig. 4 ∣. Cell-trajectory analysis of human TREG and TFR cells from primary tumor tissue and metastasized tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes.

a, Single-cell pseudotime trajectory of cells in cluster 1 (TREG cells) and cluster 6 (TFR cells) (left) or cells from primary tumor tissue or metastatic tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes (right) constructed using the Monocle3 algorithm. b, Normalized gene expression of IL1R2, CCR8, TNFRSF9, TNFRSF18 and PDCD1 on pseudotime path as in (a).

Extended Data Fig. 5 ∣. TCR-seq analysis of tumor-infiltrating TREG and TFR cells.