Abstract

Objective:

To describe the demographic, injury-related and mental health characteristics of firearm injury patients and trace firearm weapon carriage and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms over the year following injury.

Summary and Background Data:

Based on the increasing incidence of firearm injury and need for novel injury prevention strategies, hospital-based violence intervention programs are being implemented in US trauma centers. There is limited data on the long-term outcomes and risk behaviors of firearm injury survivors to guide this work.

Methods:

We conducted a secondary analysis of a pragmatic 25-trauma center randomized trial (N=635). Baseline characteristics of firearm-injured patients (N=128) were compared with other trauma patients. Mixed model regression was used to identify risk factors for post-injury firearm weapon carriage and PTSD symptoms.

Results:

Firearm injury patients were younger and more likely to be black, male and of lower socioeconomic status and more likely to carry a firearm in the year prior to injury. Relative to pre-injury, there was a significant drop in firearm weapon carriage at 3- and 6–months post-injury, followed by a return to pre-injury levels at 12-months. Firearm injury was significantly and independently associated with an increased risk of post-injury firearm weapon carriage (Relative Risk=2.08,95% CI[1.34, 3.22],p <0.01) and higher PTSD symptom levels (Beta=3.82,95% CI[1.29, 6.35],p < 0.01).

Conclusions:

Firearm injury survivors are at risk for firearm carriage and high PTSD symptom levels post-injury. The significant decrease in the high-risk behavior of firearm weapon carriage at 3–6 months post-injury suggests that there is an important post-injury “teachable moment” that should be targeted with preventive interventions.

Trial Registration:

MINI-ABSTRACT

Survivors of firearm injury are significantly more likely to engage in the high-risk behavior of firearm weapon carriage and to struggle with PTSD symptoms post-injury. There is, however, a significant drop in firearm weapon carriage at 3- and 6-months post-injury, which, represents an important “teachable moment” for future targeted interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Individual and mass firearm injuries constitute a major public health challenge in the United States.1–4 Annually, approximately 32,000 individuals die from firearm injuries, and over 67,000 individuals are so severely injured that they seek attention in acute care medical emergency department settings. Over half of these 67,000 individuals require inpatient hospitalization.5 In the wake of a firearm injury, survivors are at high risk for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and related comorbid conditions.6,7 Firearm injury survivors also have high rates of emergency department and hospital recidivism, including frequent recurrent firearm-related visits. 1,8–10 High risk behaviors such as firearm weapon carriage and mental health symptoms such as PTSD have been associated with marked functional impairment, high risk of re-injury and increased societal costs after firearm injury.6–9,11,12

Previously, legislative barriers have made scientific inquiry into primary and secondary preventive interventions for firearm injury challenging to implement, resulting in a substantive research to practice gap.6,13–17 Recent events, including the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing US firearm sales and social unrest, highlight the need for research that catalyzes the development of primary and secondary preventive interventions.4,18–21 A series of investigations in adult patients have assessed the impact of hospital-based programs for firearm injury survivors, yet the results of these studies are mixed, and many of these investigations are not optimally designed as preventive intervention trials. 22–25 A smaller number of well-designed randomized preventive intervention trials with adolescent patients in acute care medical settings suggest that motivational interviewing interventions can effectively target reductions in high risk injury behaviors, including peer violence and weapon carriage.11,26 Few comprehensive multisite investigations exist, however, that directly inform the development of hospital-based firearm injury prevention programs.

In this prospective study, first we aim to describe the demographic, injury, and clinical characteristics firearm injury survivors admitted to 25 US Level I trauma centers in comparison with non-firearm injury patients admitted during the same time period. We trace the course of post-injury firearm weapon carriage and identify baseline risk factors associated with an increased risk of post-injury firearm weapon carriage to define optimal post-injury timeframes for the delivery of preventive interventions. The investigation also seeks to identify the independent contribution of the firearm injury mechanism to the development of PTSD symptoms over the course of the year after the index injury admission.

METHODS

Design Overview

The investigation was a secondary study and analysis of data embedded within a larger pragmatic randomized trial, designed to assess the impact of a collaborative care on PTSD symptoms.27 The Trauma Survivors Outcomes and Support (TSOS) pragmatic trial was orchestrated by the study team’s data coordinating center, located at University of Washington’s Harborview Medical Center, in close collaboration with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory.28,29 Sites recruited into the study constituted a representative subsample of all US Level I trauma centers.28 Recruitment for the trial began in January of 2016, and 12-month patient study follow-up ended in November of 2018. Patients were assessed at baseline as inpatients and again at 3-, 6- and 12-months after injury. The Western Institutional Review Board approved the protocol prior to study initiation and informed consent was obtained for participation in the study.

Patient Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Survivors of intentional and unintentional injuries ≥ 18 years of age were included in the investigation. Prisoners and non-English-speaking patients were excluded. Patients whose index injury was a suicide attempt or who were psychotic and required immediate psychiatric treatment were also excluded from the trial. In order to ensure adequate follow-up rates, patients were required to provide two pieces of contact information.

Electronic Health Record (EHR) PTSD Screen

The study team had previously developed a 10-domain electronic health record (EHR) screen to detect patients at risk for the development of PTSD (Appendix 1).30 Patients identified by EHR evaluation as high risk for PTSD, with a score of ≥ 3 domains positive, were then formally screened for study entry with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV)31 PTSD Checklist (PCL-C), anchored to the acute injury event.32–34 Patients scoring ≥ 35 on the PCL-C, indicating that they had symptoms of PTSD that were at least moderate, were followed longitudinally over the course of the year after the index injury admission.

Patient-Reported Outcome Assessments

The study team attempted to contact all patients at 3-, 6- and 12-months after the index injury admissions. The follow-up interviews contained questions assessing violence risk behaviors, mental health symptoms such as PTSD, physical functioning and health services utilization. All measures had been previously administered in prior study team trials.11,28,32 Individual assessments used in this investigation are described below.

PTSD Symptoms:

The PCL-C was used to assess the symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.32–34 At baseline during the index hospitalization, patients were asked to rate their symptoms since the injury event and the 3-, 6-and 12-month interviews queried patients about their symptoms over the month prior to the interview. Prior investigations, including studies with injured patients, have established the psychometric equivalence of the DSM-IV and DSM-5 versions of the PCL-C.31,35–37 Because the study team had validated the 10-domain EHR screen with the PCL-C for DSM-IV and DSM-IV CAPS,30 all primary assessments were performed with the DSM-IV version of the PCL-C.

Firearm Weapon Carriage:

At baseline, inpatients were asked, “During the past year before your injury, did you carry a gun on you?” Patients were then again asked if they had carried a gun since their injury at the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up time points.

Other Questionnaire Items:

At baseline, single items were used to assess patients’ pre-injury gun ownership and carriage of a weapon other than a firearm (e.g., knife, club). The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) brief depression severity measure was used to assess depressive symptoms.38 The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to assess alcohol use problems.32,39 The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Physical Components Summary Score (MOS SF PCS) SF-12 was used to assess physical function in the month prior to the injury admission.32,40 The trauma history screen from the National Comorbidity Survey was used to assess pre-injury lifetime trauma exposures (e.g., combat, physical assaults, motor vehicle crashes), that occurred before the index injury admission.28,41 Questionnaire items also assessed pre-injury substance use, medical conditions and health service utilization, as well as demographic characteristics (e.g., marital status).28

Trauma Registry Data

Medical record data from the 25 sites’ trauma registries was used to derive injury severity scores and injury mechanism. Other clinical characteristics including insurance status, and length of hospital and intensive care unit stays, were also obtained from trauma registries.

Statistical Analysis

The investigation first described the baseline differences between firearm injury survivors and all other injured patients. Differences between the two groups were examined using the t-test for continuous variables and Chi-square statistic for categorical variables.

Next, the longitudinal course of firearm weapon carriage was examined using mixed effects regression models. Mixed effects regression was used to account for both repeated measures for individuals over time and site-level clustering of individual observations; mixed effects regression was used to identify significant variations in firearm weapon carriage at the 3-, 6- and 12-month post-injury time points, while adjusting for any potential intervention effects. Baseline variables associated with firearm weapon carriage over the course of the 12 months after the index injury hospitalization were also identified using mixed effects regression models. Baseline variables were entered into the regression model using a backwards elimination procedure. Although multiple clinical, sociodemographic, and injury (i.e., intervention and control group status, age, gender, race, insurance, employment status, marital status, level of education, comorbidities, gun ownership, self-reported baseline drug use, depression, ISS, TBI, prior ED visits/hospitalizations/mental health visits, number of serious prior traumas) characteristics were tested, only variables with significant independent associations at the p < 0.05 level (gender, intervention versus control group status, firearm injury, serious prior traumas, self-reported baseline drug use, employment status) were retained in the final model. Using a similar approach, the association between firearm injury and the development of PTSD symptoms longitudinally, was also assessed with mixed model regression. The following variables were included in the final model: intervention versus control group status, firearm injury, age, serious prior traumas, self-reported drug use at baseline, comorbidities. The study team repeated select analyses for the subgroup of patients who were firearm injury survivors (n = 128). Sensitivity analyses were conducted that assessed the impact of removing covariates, including intervention effects, on the mixed model regression results. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Software Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and SPSS version 25 (SPSS Software IBM).

RESULTS

Of the 635 patients followed longitudinally in the trial, 128 (20%) were survivors of firearm injuries. The demographic and clinical characteristics of firearm-injured patients versus all other patients included in the study are presented in Table 1. Firearm injury patients were younger and more likely to be male and black and were more likely to have public insurance and a lower level of education than those with non-firearm related injuries. With regards to weapon characteristics, firearm injury patients were more likely to report carrying a gun in the year prior to their injury despite not being more likely to own a gun. There were no significant differences in rates of follow-up between firearm injury survivors compared to all other injury survivors at any time point.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics*

| No. Patients (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not firearm injury (n = 507) | Firearm injury (n = 128) | P-value | |

|

| |||

| Basic Demographic | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 40.6 (14.7) | 32.7 (10.0) | <0.0001 |

| Male gender | 225 (44.4) | 100 (78.1) | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| White | 292 (57.6) | 23 (18.1) | |

| Black | 132 (26.0) | 86 (67.7) | |

| Hispanic | 40 (7.9) | 14 (11.0) | |

| American Indian | 13 (2.6) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6 (1.2) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Other | 24 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Insurance | 0.003 | ||

| Private | 171 (33.7) | 26 (20.3) | |

| Public/None/VA | 336 (66.3) | 102 (79.7) | |

| Marital status | 0.67 | ||

| Married/living with a partners | 144 (28.5) | 34 (26.6) | |

| Other | 362 (71.5) | 94 (73.4) | |

| Employed prior to injury | 307 (60.6) | 71 (55.5) | 0.30 |

| Level of Education | <0.0001 | ||

| High school or less | 325 (64.4) | 112 (88.2) | |

| At least some college | 180 (35.6) | 15 (11.8) | |

| No. of comorbid conditions | 0.003 | ||

| 0 1 2 |

140 (28.3) 92 (18.6) 77 (15.6) |

52 (43.7) 25 (21.0) 14 (11.8) |

|

| ≥3 | 185 (37.5) | 28 (23.5) | |

| Own/possess a gun | 85 (17.0) | 19 (15.3) | 0.65 |

| Carried a gun in the past year | 38 (7.6) | 19 (15.3) | 0.01 |

| Carried another weapon in the past year | 121 (24.0) | 33 (26.4) | 0.58 |

| Veteran | 35 (7.0) | 5 (4.0) | 0.22 |

| Baseline Symptoms | |||

| PTSD (PCL-C4 algorithm) positive | 272 (53.7) | 63 (49.2) | 0.37 |

| Depression (PHQ algorithm) positive | 270 (53.4) | 55 (43.0) | 0.04 |

| SF12 PCS, mean (SD) | 49.0 (10.0) | 50.9 (8.4) | 0.03 |

| SF12 MCS, mean (SD) | 44.2 (13.5) | 47.1 (12.9) | 0.03 |

| AUDIT10 positive | 215 (42.4) | 44 (34.4) | 0.10 |

| Pre-injury self-report drug (opioid/stimulant) use | 123 (24.3) | 38 (29.7) | 0.21 |

| Injury Related | |||

| ISS | 0.02 | ||

| 0–8 | 115 (24.9) | 22 (20.8) | |

| 9–16 | 156 (33.8) | 51 (48.1) | |

| >16 | 191 (41.3) | 33 (31.1) | |

| TBI | <0.0001 | ||

| None | 294 (63.6) | 94 (88.7) | |

| Mild | 97 (21.0) | 4 (3.8) | |

| Moderate/Severe | 71 (15.4) | 8 (7.6) | |

| Days in hospital, mean (SD) | 13.0 (13.0) | 12.6 (11.2) | 0.82 |

| ICU admission | 282 (59.4) | 65 (60.7) | 0.79 |

| No. of ED visits in past year, mean (SD) | 1.7 (3.2) | 1.2 (1.6) | 0.03 |

| No. of hospitalizations in lifetime, mean (SD) | 0.8 (1.7) | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.03 |

| Any mental health or substance use visit, lifetime | 197 (39.1) | 31 (24.4) | 0.002 |

| Treatment Condition | 0.38 | ||

| Control | 291 (57.4) | 79 (61.7) | |

| Intervention | 216 (42.6) | 49 (38.3) | |

| No. of serious prior traumas | 0.26 | ||

| 0 | 33 (7.6) | 5 (4.6) | |

| 1–3 | 155 (35.6) | 49 (45.0) | |

| 4–6 | 135 (31.0) | 35 (32.1) | |

| 7–8 | 58 (13.3) | 10 (9.2) | |

| ≥9 | 55 (12.6) | 10 (9.2) | |

All data presented as N (%) unless otherwise stated

Abbreviations: VA: Veterans Affairs; PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder; PCS: Physical components summary score; MCS: Mental components summary score; ISS: Injury severity score; TBI: Traumatic brain injury; ICU: Intensive care unit

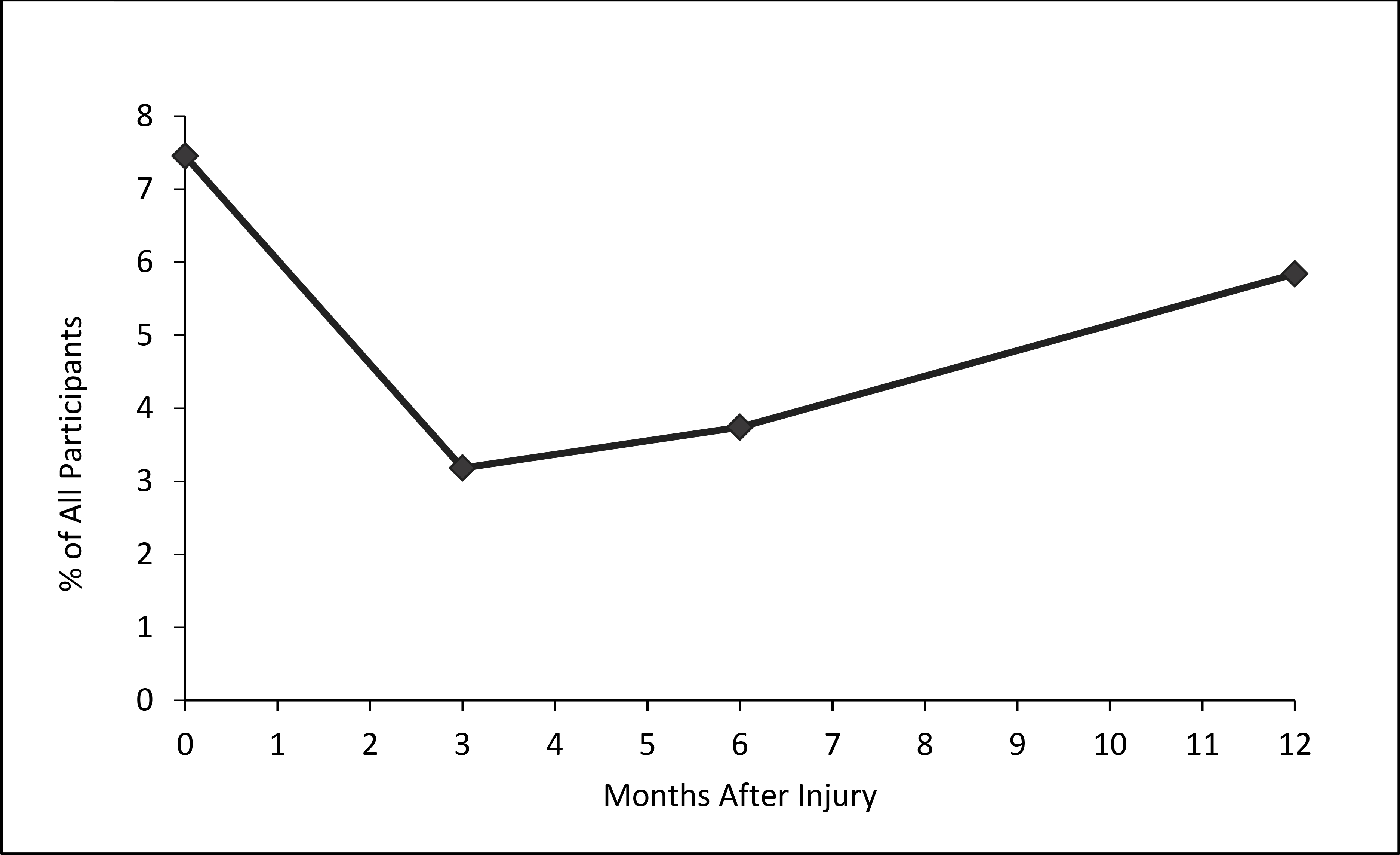

The longitudinal course of firearm weapon carriage is displayed in Figure 1. Visual examination of the data revealed a drop in self-reported weapon carriage at the 3- and 6-month post-injury time points, followed by a return of weapon carriage to approximately pre-injury levels by the 12-month post-injury time point. Mixed model regression analyses quantitatively corroborated that the 3-month (β = −0.85, SE = 0.24, P < 0.01) and 6-month (β = −0.69, SE = 0.21, P < 0.001) time points, but not the 12-month (β = −0.24, SE = 0.18, P = 0.16) time point, were significantly different from baseline pre-injury weapon carriage. Weapon carriage was also examined for the subgroup of firearm injury survivors (n = 128). Firearm injury survivors demonstrated a similar pattern of a drop and recurrence of weapon carriage, albeit with elevated frequencies compared to the full sample (i.e., at baseline, 13% weapon carriage, at 3-months, 6% weapon carriage, at 6-months, 8% weapon carriage, and at 12-months, 14% weapon carriage).

Figure 1.

Percentage of study participants carrying a firearm over the 12 months after an index injury admission.

Mixed model regression identified baseline variables that were significantly associated with firearm weapon carriage over time (Table 2). Firearm injury admission was independently associated with increased post-injury firearm weapon carriage (Relative Risk=2.08, 95% CI [1.34, 3.22], p = 0.01). A history of ≥ 5 serious prior traumas before the injury event was also associated with a greater risk of carrying a firearm over the course of the year after the index injury admission. Female gender, and baseline unemployment were associated with a reduced risk of firearm weapon carriage longitudinally.

TABLE 2.

Demographic & Clinical Characteristics Associated with Weapon Carriage over the Course of the Year after Injury

| Variable | Risk Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Firearm injury admission | 2.08 | 1.34 – 3.22 | 0.001 |

| Female | 0.46 | 0.29 – 0.73 | 0.001 |

| Not employed at baseline | 0.59 | 0.37 – 0.95 | 0.03 |

| Randomized to intervention | 0.50 | 0.27 – 0.93 | 0.03 |

| ≥5 serious prior traumas | 1.62 | 1.06 – 2.50 | 0.03 |

Baseline firearm injury was independently associated with the development of significantly elevated PTSD symptoms (Beta=3.82, 95% CI=1.29, 6.35 p < 0.003) over the course of the year after the index injury admission (Table 3). Other factors associated with the developed of PTSD symptoms included ≥ 5 serious prior traumas, self-reported baseline substance use, ≥ 3 comorbidities and younger age.

TABLE 3.

Demographic & Clinical Characteristics Associated with PTSD Symptoms over the Course of the Year after Injury

| Variable | Beta | 95% Confidence Interval | P |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Firearm-related index injury | 3.82 | 1.29, 6.35 | 0.003 |

| ≥5 serious prior traumas | 5.89 | 3.95, 7.82 | <0.0001 |

| Age (continuous) | −0.10 | −0.18, −0.03 | 0.007 |

| Self-report drug use at baseline | 2.46 | 0.44, 4.48 | 0.017 |

| ≥3 medical comorbidities | 5.51 | 3.30, 7.72 | <0.0001 |

| Intervention | 2.34 | −0.14, 4.83 | 0.064 |

Sensitivity analyses that removed covariates did not substantially alter the magnitude, pattern, or directionality of the observed treatment effects.

DISCUSSION

Firearm injury survivors had a significantly increased risk of firearm weapon carriage and higher PTSD symptom levels over the course of the year after injury admission compared to survivors of all other injury mechanisms. This increased risk of post-injury firearm weapon carriage and higher PTSD symptoms were observed even after other relevant demographic and clinical characteristics were accounted for.

Weapon carrying characteristics, even among firearm injury survivors, were not static. Survivors of firearm injury were less likely to carry a firearm from the time of injury to 6-months post-injury with subsequent return to baseline levels by 12 months post-injury; a finding that has important implications. This naturalistic “dip” in firearm carriage post-injury suggests that there may be an important post-injury “teachable moment”. Firearm weapon carriage is known to increase the risk of firearm-related injury42. There are several plausible mechanisms via which firearm weapon possession may increase an individuals’ risk of firearm injury; guns may result in a false sense of empowerment that may cause an individual to overreact, may make an individual more likely to enter dangerous environments that they may otherwise have avoided, and the gun possessed by an individuals may be turned on them during an otherwise gun-free conflict42. The diminishment and subsequent recurrence of weapon carriage post-injury described in this study represents a window of opportunity for preventive interventions targeting reductions in recurrent violent injury.

There exists an important analogy and precedent for this. Approximately two decades ago, prospective studies informed the development of hospital-based secondary preventive interventions targeting recurrent alcohol use injury risk behaviors.43 These investigations included longitudinal investigations that documented a naturalistic “dip” and subsequent recurrence of alcohol consumption during the days and weeks immediately after an index traumatic injury admission.44 Other efficacy, effectiveness and implementation randomized clinical trials documented sustained reductions in alcohol use among patients assigned to brief bedside motivational interviewing interventions targeting reductions in alcohol-related risk behaviors.45,46 More recently, motivational interviewing interventions that provided “booster” sessions in the days and weeks after an initial injury admission were also shown to effectively reduce alcohol consumption.47

At a time when many hospitals and trauma systems are looking to develop effective violence intervention programs to break the cycle of violent injury25,48, our findings inform these efforts. Firearm-related injury has been previously been shown to be associated with an increased risk of recurrent firearm-related hospitalization, firearm-related death and firearm-related arrest.10 Re-injury, or recidivism, has become a key outcome metric for injury prevention programs.49 To date the approach to and study of violence intervention programs has been variable and few multisite investigations exist to inform programmatic intervention development. In this study, we describe an important naturalistic “dip” in firearm carriage post-injury that lends itself to interventions aimed at maintaining decreased firearm carriage over time. Our data also informs the timing of such interventions suggesting that these efforts should be focused in the early post-injury phase. Interestingly, firearm injury patients in this study were not more likely to own a gun compared to those individuals injured as a result of another mechanism, suggesting that perhaps our focus should be on weapon carriage rather than ownership, as well as the mental health, sociodemographic and related factors that may be contributing to the high-risk behavior of firearm weapon carriage. The optimal nature of these interventions remains to be established, highlighting the need for well-designed future pragmatic intervention trials.

We also found firearm related injury to be independently associated with significantly elevated PTSD symptoms. Although the mental health outcomes of firearm injury survivors could benefit from additional investigation, there are some recent published studies demonstrating the increased mental health burden faced by survivors of firearm violence with which our findings resonate.50 Specifically, Joseph et al6 reported a high readmission rate for survivors of firearm-related injury and that survivors of a semiautomatic rifle or shotgun-related injury had a higher risks of developing acute stress disorder or PTSD upon readmission compared with survivors of a handgun-related injury. Subsequently, Escobar-Herrera et al7 reported that compared with matched MVC survivors, firearm injury survivors were significantly more likely to screen positive for PTSD and had significantly worse mental-health related quality of life. The factors contributing to the differential mental health outcomes after firearm injury are likely multifactorial and complex. A greater perceived threat to life and the community context in which most violence-related firearm injuries occur may be key factors.51 In addition, firearm survivors often come from more vulnerable socioeconomic neighborhoods with limited social support networks, which can make access to post-discharge care and resources a challenge. The findings of the current study suggest that early trauma center based mental health service delivery should be a central focus of violence intervention programs.

This investigation has limitations. Most notably the study is a secondary analysis of a data derived from a randomized clinical trial of a broader patient population. Although all longitudinal analyses are adjusted for potential intervention effects, a prospective cohort design would have been optimal for describing the naturalistic evolution of post-injury firearm carriage.

The results of this investigation suggest that as with alcohol screening and brief intervention two decades earlier, firearm injury survivors represent a unique and vulnerable injury population, appropriate for the development of hospital-based “teachable moment” preventive interventions. Orchestrated efforts targeting policy and funding could systematically incorporate firearm preventive screening, intervention and referral trial findings into national trauma center requirements and verification criteria.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory by cooperative agreement 1UH2MH106338–01/4UH3MH106338–02 from the NIH Common Fund and by UH3 MH 106338–05S1 from NIMH. Support was also provided by the NIH Common Fund through cooperative agreement U24AT009676 from the Office of Strategic Coordination within the Office of the NIH Director. This research was also supported in part by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (IH-1304–6319, IHS-2017C1–6151). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, or of PCORI or its Board of Governors.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Reprints will not be available from the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonne S, Tufariello A, Coles Z, et al. Identifying participants for inclusion in hospital-based violence intervention: An analysis of 18 years of urban firearm recidivism. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2020;89(1):68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulger EM, Kuhls DA, Campbell BT, et al. Proceedings from the Medical Summit on Firearm Injury Prevention: A public health approach to reduce death and disability in the US. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2019;229(4):415–430.e412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butkus R, Doherty R, Bornstein SS. Reducing Firearm Injuries and Deaths in the United States: A Position Paper From the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2018;169(10):704–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowhani-Rahbar A, Zatzick DF, Rivara FP. Long-lasting Consequences of Gun Violence and Mass Shootings. JAMA. 2019;321(18):1765–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fowler KA, Dahlberg LL, Haileyesus T, et al. Firearm injuries in the United States. Preventive medicine. 2015;79:5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joseph B, Hanna K, Callcut RA, et al. The Hidden Burden of Mental Health Outcomes Following Firearm-related Injures. Annals of surgery. 2019;270(4):593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrera-Escobar JP, de Jager E, McCarty JC, et al. Patient-reported Outcomes at 6 to 12 Months Among Survivors of Firearm Injury in the United States. Ann Surg. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson PD, Ippolito JA, Shaath MK, et al. Pediatric gunshot wound recidivism: Identification of at-risk youth. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(6):877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall WA, Egger ME, Pike A, et al. Recidivism rates following firearm injury as determined by a collaborative hospital and law enforcement database. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(2):371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowhani-Rahbar A, Zatzick D, Wang J, et al. Firearm-related hospitalization and risk for subsequent violent injury, death, or crime perpetration: A cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. 2015;162(7):492–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zatzick D, Russo J, Lord SP, et al. Collaborative Care Intervention Targeting Violence Risk Behaviors, Substance Use, and Posttraumatic Stress and Depressive Symptoms in Injured Adolescents: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(6):532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zatzick D, Jurkovich G, Fan MY, et al. The association between posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms, and functional outcomes in adolescents followed longitudinally after injury hospitalization. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2008;162(7):642–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Health Systems Interventions to Prevent Firearm Injuries and Death: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leshner Alan I., Altevogt BM, Lee AF, et al. , eds. Priorities for Research to Reduce the Threat of Firearm-Related Violence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. Committee on Priorities for a Public Health Research Agenda to Reduce the Threat of Firearm-Related Violence. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ladapo JA, Rodwin BA, Ryan AM, et al. Scientific Publications on Firearms in Youth Before and After Congressional Action Prohibiting Federal Research Funding. JAMA. 2013;310(5):532–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Branas CC, Wiebe DJ, Schwab CW, et al. Getting past the “f” word in federally funded public health research. Inj Prev. 2005;11(3):191–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamieson C Gun violence research: History of the federal funding freeze. Psychological Science Agenda. February, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sacks CA, Bartels SJ. Reconsidering Risks of Gun Ownership and Suicide in Unprecedented Times. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(23):2259–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galea S, Abdalla SM. COVID-19 Pandemic, Unemployment, and Civil Unrest: Underlying Deep Racial and Socioeconomic Divides. JAMA. 2020;324(3):227–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schleimer JP, McCort CD, Pear VA, et al. Firearm Purchasing and Firearm Violence in the First Months of the Coronavirus Pandemic in the United States. Preprint at http://medrxivorg/content/early/2020/07/11/2020070220145508abstract. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Yeates EO, Grigorian A, Barrios C, et al. Changes in Traumatic Mechanisms of Injury in Southern California Related to COVID-19: Penetrating Trauma as a Second Pandemic. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2020;Publish Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyons VH, Floyd AS, Griffin E, et al. Helping Individuals with Firearm Injuries: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2020;Publish Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Affinati S, Patton D, Hansen L, et al. Hospital-based violence intervention programs targeting adult populations: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma evidence-based review. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open. 2016;1(1):e000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juillard C, Smith RM, Anaya N, et al. Saving lives and saving money: Hospital-based violence intervention is cost-effective. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2015;78:25R 258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snider CE, Jiang D, Logsetty S, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a hospital-based violence intervention program on reducing repeat violent injury in youth: a randomized control trial. CJEM. 2020;22(3):313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(5):527–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zatzick Jurkovich G, Heagerty P, et al. Stepped Collaborative Care Targeting Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Comorbidity for US Trauma Care Systems: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surgery. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zatzick Russo J, Darnell D, et al. An effectiveness-implementation hybrid trial study protocol targeting posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbidity. Implementation science : IS. 2016;11:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NIH. NIH Collaboratory. 2020; https://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/.Accessed August 12, 2020.

- 30.Russo J, Katon W, Zatzick D. The development of a population-based automated screening procedure for PTSD in acutely injured hospitalized trauma survivors. General hospital psychiatry. 2013;35(5):485–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association Task Force on DSM-IV. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Fourth ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zatzick Jurkovich G, Rivara FP, et al. A randomized stepped care intervention trial targeting posttraumatic stress disorder for surgically hospitalized injury survivors. Annals of Surgery. 2013;257(3):390–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zatzick D, O’Connor SS, Russo J, et al. Technology-Enhanced Stepped Collaborative Care Targeting Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Comorbidity After Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(5):391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weathers F, Ford J. Psychometric review of PTSD Checklist (PCL-C, PCL-S. PCL-M, PCL-PR). In: Stamm B, ed. Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation. Lutherville: Sidran Press; 1996:250–251. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoge CW, Riviere LA, Wilk JE, et al. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in US combat soldiers: a head-to-head comparison of DSM-5 versus DSM-IV-TR symptom criteria with the PTSD checklist. The lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(4):269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosellini AJ, Stein MB, Colpe LJ, et al. Approximating a DSM-5 Diagnosis of PTSD using DSM-IV Criteria. Depression and anxiety. 2015;32(7):493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition: DSM-5. Fifth ed. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babor TF, Grant M. From clinical research to secondary prevention: International collaboration in the development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1989;13:371–374. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical care. 1996;34(3):220–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kessler R, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of general psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Branas CC, Richmond TS, Culhane DP, et al. Investigating the link between gun possession and gun assault. American journal of public health. 2009;99(11):2034–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, et al. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Ann Surg. 1999;230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunn C, Zatzick D, Russo J, et al. Hazardous drinking by trauma patients during the year after injury. Journal of Trauma. 2003;54(4):707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kodadek LM, Freeman JJ, Tiwary D, et al. Alcohol-related trauma reinjury prevention with hospital-based screening in adult populations: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma evidence-based systematic review. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2020;88(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zatzick D, Donovan DM, Jurkovich G, et al. Disseminating alcohol screening and brief intervention at trauma centers: a policy-relevant cluster randomized effectiveness trial. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2014;109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Field C, Walters S, Marti CN, et al. A multisite randomized controlled trial of brief intervention to reduce drinking in the trauma care setting: how brief is brief? Ann Surg. 2014;259(5):873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenblatt MS, Joseph KT, Dechert T, et al. American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Prevention Committee topical update: Impact of community violence exposure, intimate partner violence, hospital-based violence intervention, building community coalitions and injury prevention program evaluation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87(2):456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCoy AM, Como JJ, Greene G, et al. A novel prospective approach to evaluate trauma recidivism: The concept of the past trauma history. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2013;75(1):116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barrett EL, Teesson M, Mills KL. Associations between substance use, post-traumatic stress disorder and the perpetration of violence: A longitudinal investigation. Addictive behaviors. 2014;39(6):1075–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Neill KM, Vega C, Saint-Hilaire S, et al. Survivors of gun violence and the experience of recovery. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2020;89(1):29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]