Abstract

Hereditary deafness is clinically and genetically heterogeneous. We investigated deafness segregating as a recessive trait in two families. Audiological examinations revealed an asymmetric mild to profound hearing loss with childhood or adolescent onset. Exome sequencing of probands identified a homozygous c.475G>A;p.(Glu159Lys) variant of CLDN9 (NM_020982.4) in one family and a homozygous c.370_372dupATC;p.(Ile124dup) CLDN9 variant in an affected individual of a second family. Claudin 9 (CLDN9) is an integral membrane protein and constituent of epithelial bicellular tight junctions that form semi-permeable, paracellular barriers between inner ear perilymphatic and endolymphatic compartments. Computational structural modeling predicts that substitution of a lysine for glutamic acid p.(Glu159Lys) alters one of two cis-interactions between CLDN9 protomers. The p.(Ile124dup) variant is predicted to locally misfold CLDN9 and mCherry tagged p.(Ile124dup) CLDN9 is not targeted to the HeLa cell membrane. In situ hybridization shows that mouse Cldn9 expression increases from embryonic to postnatal development and persists in adult inner ears coinciding with prominent CLDN9 immunoreactivity in tight junctions of epithelia outlining the scala media. Together with the Cldn9 deaf mouse and a homozygous frameshift of CLDN9 previously associated with deafness, the two bi-allelic variants of CLDN9 described here point to CLDN9 as a bona fide human deafness gene.

Keywords: Non-syndromic deafness, exome sequencing, tight junctions, Claudin 9, Morocco, Pakistan

1. INTRODUCTION

Tight junctions (TJs) are semi-permeable barriers between two adjacent cells and are comprised of a variety of proteins (Balda & Matter, 2000; Furuse et al., 1993; Piontek et al., 2020). The large family of claudins is among the key protein constituents of bicellular TJs along with occludin (Zihni et al., 2016), junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs), intracellular plaque proteins (ZO-1, 2 and 3, AF-6, MUPP-1) and MARVELD2, which was originally named tricellulin because of its location at the point where three epithelial cells contact one another (Tervonen et al., 2019; Zihni et al., 2016). Claudins are integral membrane proteins that range in size from 20 to 27 kDa and have two extracellular loops (EL1 and EL2) and one cytoplasmic loop (Furuse et al., 1998).

Transmission electron microscope images revealed that claudins form anastomosing beaded strands on the opposing cell membranes of two neighboring cells (Furuse et al., 1998; Furuse et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2018). The EL1 of a claudin is involved in a trans-interaction with the EL1 of another claudin molecule on an adjacent opposing cell membrane. The charged amino acids in the EL1 of claudins confer ionic selectivity across the paracellular pathway (Colegio et al., 2002; Van Itallie & Anderson, 2006; Weber et al., 2015), forming semi-permeable barriers that selectively limit diffusion of small molecules and ions in the paracellular space to maintain homeostasis within organs and tissues. The EL2 takes part in cis-interactions, which involve side-to-side oligomerization of juxtaposed claudins within the same cell membrane. Tight junction proteins also function in cell polarization by separating the apical from the basolateral membrane constituents (Díaz-Coránguez et al., 2019).

In mouse, variants of Cldn9, Cldn11, and Cldn14 cause deafness (Ben-Yosef et al., 2003; Gow et al., 2004; Nakano et al., 2009). In the epithelial cell lining of the inner ear, tight junctions are vital for conserving the +80 millivolt electric potential of the potassium-rich endolymph that is required for normal hearing (Furuse et al., 1999; Jahnke, 1975; Wilcox et al., 2001). In human, recessive pathogenic variants of six different claudin genes are associated with Mendelian disorders. Some of these disease phenotypes include ichthyosis, leukocyte vacuoles, alopecia, and sclerosing cholangitis (CLDN1, MIM# 603718), hypomagnesemia 5, renal with ocular involvement (CLDN19, MIM# 610036) and nonsyndromic deafness DFNB29 (CLDN14, MIM# 605608); all supported by data in multiple families with affected individuals. CLDN14 variants associated with DFNB29 hearing loss vary in severity from moderate to profound deafness in multiple families reported worldwide (Bashir et al., 2010; Latief et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2012; Pater et al., 2017; Wilcox et al., 2001). Variants in a second human claudin gene were also implicated in the etiology of hearing loss. In a Turkish family, one homozygous frameshift variant of CLDN9 (MIM# 615799) caused moderate to profound deafness in an affected mother and her two children (Sineni et al., 2019) while a missense variant p.(Cys25Trp) was proposed to result in fluctuating hearing loss in one Filipino child (Santos-Cortez et al., 2021). Here, we expand the genotype-phenotype spectrum of CLDN9-associated deafness and describe two different homozygous variants in individuals from two unrelated families affected with prelingual or adolescent-onset hearing loss. Functional studies and computational structural modeling reported here reveal a likely pathogenic mechanism.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Ethics approval

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the School of Biological Sciences, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan (IRB No. 00005281 to SN), at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, from Combined Neurosciences Blue Panel (OH-93-N-016 to TBF) and at UF Innovation en Diagnostic Genomique des Maladies Rares, CHU Dijon Bourgogne, Dijon, France to CP. Written informed consents were obtained from all participants or the parents of minor children.

2.2. Ascertainment of families and audiological tests

A research collaboration between SN and CP was established using GeneMatcher (Sobreira et al., 2015). The 17 years old proband in family HLRBS10 from Pakistan (individual IV:2, Figure 1A) was identified in a school for hearing impaired children. Subsequently, other members of the family were recruited, including a second affected sibling, an unaffected sibling, and their unaffected parents. The proband (IV:4) of family F7285 is 35 years old and of Moroccan heritage. Many members of the nuclear family participated in the genetic study (Figure 1B) except for one affected sister (IV:4) and an unaffected brother (IV:2). Pure tone audiometry for the affected individuals in family HLRBS10 was performed in ambient noise conditions, while for family F7285 hearing evaluations were conducted in a soundproof room. Hearing thresholds were measured at frequencies of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 kHz. The severity and symmetry of hearing loss were analyzed according to the guidelines proposed by GENDEAF study group (Mazzoli et al., 2003). The detection of an obvious balance dysfunction was evaluated by Romberg and tandem gait tests. History of tinnitus was also obtained from affected individuals in both families.

FIGURE 1:

Pedigrees of families HLRBS10 and F7285, pure tone audiometry and amino acid conservation. A, Pedigree of family HLRBS10 showing segregation of the c.475G>A, p.(Glu159Lys) with hearing loss. Open symbols represent unaffected individuals, while filled circles and squares denote affected individuals. * indicate that individual IV:2 of family HLRBS10 was selected for exome sequencing. B, Pedigree of family F7285. * indicate the individual selected for exome sequencing. The c.370_372dupATC variant segregated with the phenotype. C, Audiograms of individuals IV:2 and IV:3 show asymmetric moderate to profound and moderate to severe hearing loss, respectively, in two individuals from family HLRBS10. D, In family F7285, individuals IV:3 and IV:4 have down-sloping audiograms and display an asymmetric mild hearing loss at the lower frequencies and profound deafness at the higher frequencies. E, F, Partial sequence traces indicating variants c.475G>A and c.370_372dupATC in affected individuals from the families HLRBS10 and F7285, respectively. Arrows indicate positions of the mutated residues. G, H, CLUSTALO multiple alignment shows that the glutamic acid-159 residue (Glu-159) is highly conserved in CLDN9 proteins from a variety of vertebrate species. Partial sequence alignment for human CLDN9 with its paralogues also indicates conservation of Glu-159. CLDN14, which is another tight junction protein required for normal hearing, also has a glutamate residue at the corresponding position.

2.3. Genome-wide SNP genotyping

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping was performed on genomic DNA samples for two unaffected (III:1, IV:1) and one affected (IV:3) individuals from family HLRBS10 (Figure 1A). A total of 960,919 SNPs was analyzed using Infinium® OmniExpressExome-8 v1.4 BeadChip with Infinium HD Super-assay. The genotyping data were evaluated using Illumina GenomeStudio® software (version 2) using the standard genotyping module in the program. Individual SNP genotyping data with a call rate of more than 95% (passing criteria) were exported as a text file from GenomeStudio, submitted to AutoSNPa version 3 software and analyzed according to standard procedures (Carr et al., 2006).

2.4. Exome sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood cells of individual IV:2 of family HRBS10 (Figure 1A) and used to perform exome sequencing at the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics using Agilent SureSelect HumanAllExonV4_51Mb Kit_S03723314 on Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Exome sequencing for individual IV:4 from family F7285 was performed as previously described (Thevenon et al., 2016). Exome data was aligned against the human GRCh37/hg19 genome assembly. wANNOVAR (http://wannovar.usc.edu/) was utilized for annotating the variant call files (VCF). The output data from wANNOVAR was used to check the population frequencies of selected variants in the 1000 Genomes Project database, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP6500), Greater Middle East (GME) Variome database, genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) and the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) database. Variants with frequencies less than 0.01 in all the populations were considered. Homozygous, hemizygous and compound heterozygous variants were examined, which included exonic and splice-site variants. The wANNOVAR files included predicted pathogenic effects for the variants from PolyPhen-2, MutationTaster and SIFT (Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant) along with the pathogenicity CADD (Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion) scores. In addition, REVEL (Rare Exome Variant Ensemble Learner) pathogenicity scores for the variants were also assessed (http://sites.google.com/site/revelgenomics/). Multiple amino acid sequence alignments of different protein orthologues and the closest paralogues of CLDN9 were completed using ClustalO (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tool/msa/clustalo). Protein sequences for homologues were retrieved from Uniprot (http://www.uniprot.org).

2.5. Computational modeling

To identify a suitable template for the structural modeling of human claudin 9 (hCLDN9) we used the fold recognition procedure implemented in the HHpred server (Hildebrand et al., 2009). First, a sequence profile of hCLDN9 was obtained after three iterations of HHblits (Remmert et al., 2012) against the Uniprot20 database dated 2016_02. The resulting profile was then scanned against a database containing the sequence profiles for each of the protein structures deposited in the protein data bank. Mouse claudin 15, (mCLDN15, PDB ID: 4P79) was identified as a suitable template with an amino acid sequence identity of 35.5% with hCLDN9. The alignment obtained with HHpred (Supp. Figure S1A) was then used to obtain the structural model of hCLDN9 monomer. The final model was selected based on the best MolPDF score (Melo et al., 2002) from a pool of 2000 models generated with MODELLER software (Šali & Blundell, 1993). The quality of the structure was assessed by PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993) analysis. The dimer of hCLDN9 in cis-1 configuration was obtained after structurally superimposing one hCLDN9 monomer onto each of the protomers in the cis-1 dimer of mCLDN15 (Zhao et al., 2018). The residues at the interface (defined as any residue containing an atom within 5Å of the other protomer) were subsequently refined using MODELLER.

The p.Glu159Lys mutation was introduced in the final hCLDN9 cis-1 dimer and the final hCLDN9_Glu159Lys cis-1 dimer model was selected with the best MolPDF score from the 2000 models generated with MODELLER. The quality of the model was checked by PROCHECK analysis and conservation scores for hCLDN9 were calculated using Consurf (Ashkenazy et al., 2016). The structural model of hCLDN9 with a duplication of the Ile124 residue was obtained in two ways: (a) by the introduction of an extra Ile residue displacing the rest of the sequence in the helix (Supp. Figure S1B); and (b) by the addition of Ile which modified the canonical helix turn, but otherwise did not affect the remaining wild-type sequence in the helix (Supp. Figure S1C). These two strategies were used to generate, in each case, 2,000 models with MODELLER. The final models of hCLDN9_Ile124dup and hCLDN9_Ile124dup_hturn were those with the best MolPDF scores and the best outcome using PROCHECK analyses.

2.6. Single molecule mRNA in situ hybridization using RNAscope probes

To examine the expression of mouse Cldn9 mRNA in the cells of the inner ear, in situ hybridization was performed using RNAscope Probe-Mm-Cldn9 (target region: 34–1403 nucleotides, NM_020293.3). Probe-Mm-Myo7a-C2 (target region: 1365–2453 nucleotides, NM_001256081.1) is specific to detect Myo7a mRNA and was used as a positive control for expression in hair cells. Cldn9 has a nucleotide sequence identity of 58% with Cldn6. Therefore, probe-Mm-Cldn6–01-C3 (target region: 414–1424 nucleotides, NM_018777.4) was used to explore the specificity of the Mm-Cldn9 probe. Both probes were obtained from Advanced Cell Diagnostics (Newark, CA, USA).

Approval for the procedures involving animals was obtained from the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the NIDCD, NIH, USA (protocol 1263–18). Cochleae from C57BL/6J wild-type mice at P3 and P30 or those with brain hemisected at E14.5 and E18.5 were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4ºC. Cochleae were then cryopreserved in 15% sucrose in 1x PBS overnight and then in 30% sucrose overnight at 4ºC. Each cochlea was embedded and frozen in Super Cryoembedding Medium (Section-Lab, Hiroshima, Japan). Cryosections of approximately 12 μm in thickness were obtained using a CM3050S cryostat microtome (Leica, Vienna, Austria). An RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent v2 assay (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) was conducted to visualize single RNA molecules. Images were taken using LSM mode and a 40x, 1.4 NA objective on an LSM880 Airyscan confocal microscope (Zeiss, Inc. Germany).

2.7. Expression plasmids

Construction of the EYFP-CLDN9WT-encoding tet-off plasmid (EYFP-CLDN9WT-pUHD10–3H) was described previously (Nakano et al., 2009). To create a CLDN9E159K encoding version of the same plasmid (EYFP-CLDN9E159K pUHD10–3H), a c.475G>A point mutation was introduced into the CLDN9 encoding region of EYFP-CLDN9WT-pUHD10–3H using the GENEART™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis system (Invitrogen, USA). The absence of unintended mutations in EYFP-CLDN9E159K-pUHD10–3H was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Wild-type mouse Cldn9 was also cloned into pEGFP-C2 and p-mCherry-C1 vectors using In-Fusion® HD Cloning Kit (Takara Bio Inc. USA). The p.Glu159Lys variant was introduced into both of the Cldn9 constructs using a QuickChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). To assess the effect of p.(Ile124dup) on the the subcellular localization of CLDN9, wild-type human CLDN9 was cloned into the p-mCherry-C1 vector using In-Fusion® HD Cloning Kit (Takara Bio Inc. USA) and mutated to the c.370_372dupATC;p.(Ile124dup) variant using the QuickChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.8. Antibody validation and immunohistochemistry

The specificity of the rabbit polyclonal anti-CLDN9 antibody (HPA076613, Sigma Aldrich, USA) was validated in MDCK-II cells (ATCC, CRL-2936™) grown to 70% confluency in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Corning™, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were transfected with an expression vector encoding EYFP-CLDN9WT using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen), washed and fixed with 1x PBS and ice-cold methanol (15 minutes, 4°C). To check if the localization of mutant CLDN9 is different than a wild-type CLDN9, EYFP-CLDN9E159K was transfected in MDCK-II cells in the same way as EYFP-CLDN9WT plasmid. After permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min, cells were incubated in blocking solution (2% BSA and 5% goat serum in 1x PBS) for 1 hour, and then incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-CLDN9 antibody (HPA076613, Sigma Aldrich) and mouse monoclonal anti-ZO-1 antibody (Product # 33–9100, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for 2 hours, followed by three subsequent washes with 1x PBS. The cells were stained with Alexa Flour 568 and Alexa Flour 647 anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, USA), respectively. After three washes with 1x PBS, cells were mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade reagent containing DAPI (Molecular Probes) and imaged using an LSM780 confocal microscope, equipped with a 63x, 1.4 N.A. objective (Zeiss Inc).

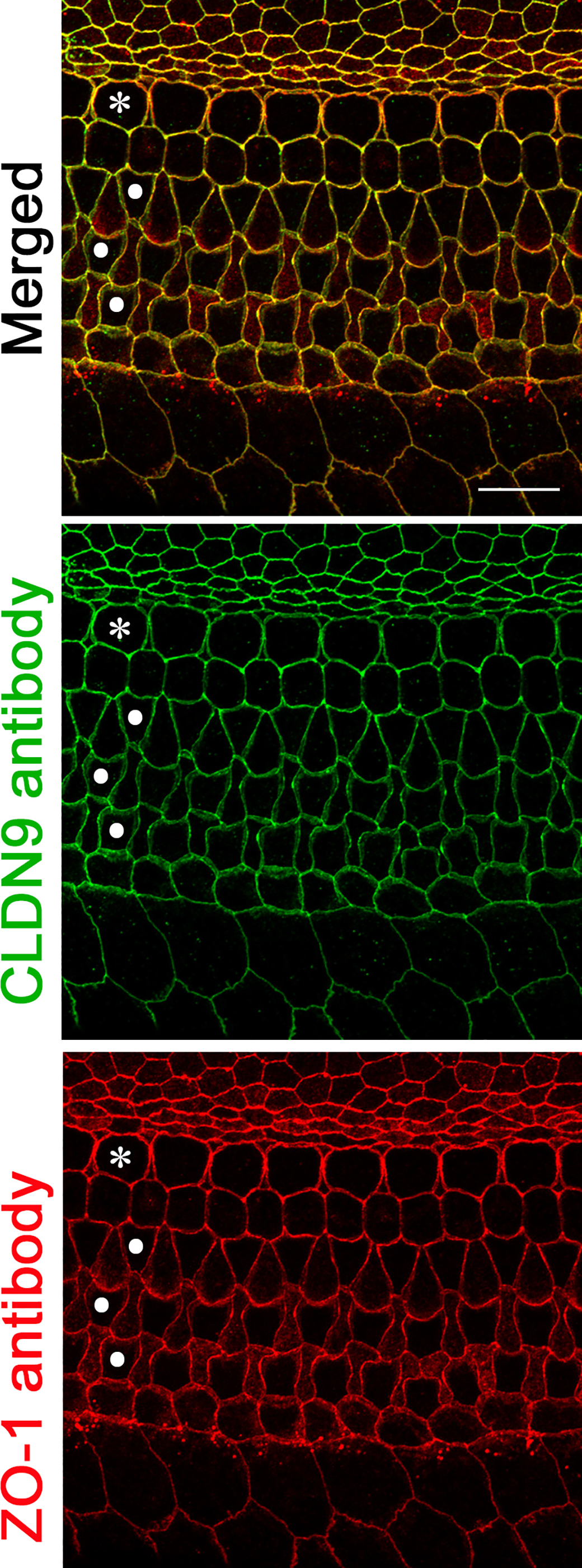

Immunolocalization of CLDN9 was tested in mouse inner ear samples at age P6. The dissected cochlea and vestibule were fixed overnight in Prefer fixative (Anatech Ltd., USA). Permeabilization was done with 0.5% Triton X-100 and blocking was performed with 2% BSA and 5% goat serum in 1x PBS. Samples were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-CLDN9 antibody (HPA076613, Sigma Aldrich) and mouse monoclonal anti-ZO-1 antibody (Product # 33–9100, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 2 hours, washed with 1x PBS and stained with anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Alexa Flour 488 and 568 respectively). Specimen were mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade (Molecular Probes) and observed with the 63x objective using an LSM780 (Zeiss Inc).

2.9. MDCK-II cell culture

Tet-off MDCK-II cells, (a kind gift from Dr. Charles Yeaman, University of Iowa), were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), (Atlanta Biologicals, USA), penicillin (100 units/ml; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml; Thermo Fisher Scientific). To generate stable clones of MDCK-II cells that express wild-type CLDN9 (CLDN9WT) or CLDN9E159K in an inducible fashion, linearized EYFP-CLDN9WT pUHD10–3H and EYFP-CLDN9E159K pUHD10–3H were transfected into tet-off MDCK-II cells using Lipofectamine LTX reagent and PLUS reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Stable clones were isolated following selection with hygromycin (300 μg/ml; Thermo Fisher Scientific). All MDCK-II cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

2.10. Measurement of transepithelial electrical resistance and transepithelial dextran diffusion

Parental non-transfected tet-off MDCK-II cells and the isolated stable clones of transfected tet-off MDCK-II cells were seeded onto Transwell Permeable Supports (12 mm diameter and 0.4 μm pore size, Corning™) at a density of 4.5×104 cells/cm2. These Transwell cultures were incubated in the presence or absence of doxycycline (100 ng/ml; Clontech, USA) for 6 days. Tet-off MDCK-II cells formed confluent monolayers on the Transwell inserts in 3 days. Electrical resistance was measured on days 4–6 using Millicell Electrical Resistance System (Millipore, USA) in the cell culture medium. Electrical resistance was also measured across blank inserts. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was calculated by subtracting the resistance measured across the blank inserts from the resistance measured across the inserts with the tet-off MDCK-II monolayers. TEER was measured in three Transwell cultures per cell clone, time point, and condition (i.e., doxycycline-treated and untreated). TEER values from these technical replicates were averaged to obtain a mean value for each clone, time point, and treatment condition. Following the TEER measurements on day 6, the cell culture medium on tet-off MDCK-II cells was replaced with fluorescence assay medium composed of FluoroBrite DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5% FBS, L-glutamine (4 mM, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and doxycycline (0 or 100 ng/ml). Cells were incubated in the fluorescence assay medium (270 μl in the upper chamber and 1 ml in the lower chamber) for 1 hour. At the end of this incubation period, 30 μl mix of FluoroBrite DMEM and FITC-dextran 4 kDa (FD4) or FITC-dextran 500 kDa (FD500) (Sigma Aldrich) was added to the upper chamber to achieve 2.5 mg/ml concentration of FD4 and FD500 at time 0. Transwell cultures were incubated with FD4 and FD500 at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After incubation for 6 hours, samples (150 μl) were collected from the lower chamber for fluorescence measurements (λex = 458 nm, λem = 520 nm) in a microplate reader (Victor3 Multilabel Counter, PerkinElmer, USA). Concentrations of FD4 and FD500 in the collected samples were determined by extrapolation from standard curves. Apparent permeability coefficients (Papp) were calculated using Eq. 1 as previously described (Karlsson & Artursson, 1991):

| (1) |

where Vr (cm3) is the volume of the acceptor compartment, dC × dt−1 is the slope of change in solute concentration in the acceptor compartment over time (μg/ml × s−1), A is the membrane surface area (cm2), and C0 is the initial concentration of solute in the donor compartment (μg/ml). FD4 permeability of monolayers of tet-off MDCK-II cells was measured in two Transwell cultures per cell clone and conditions (i.e., doxycycline-treated and untreated). Data from these technical replicates were averaged to obtain a single Papp number per clone and condition. FD500 permeability of monolayers of tet-off MDCK-II cells was measured in one Transwell culture per cell clone and condition.

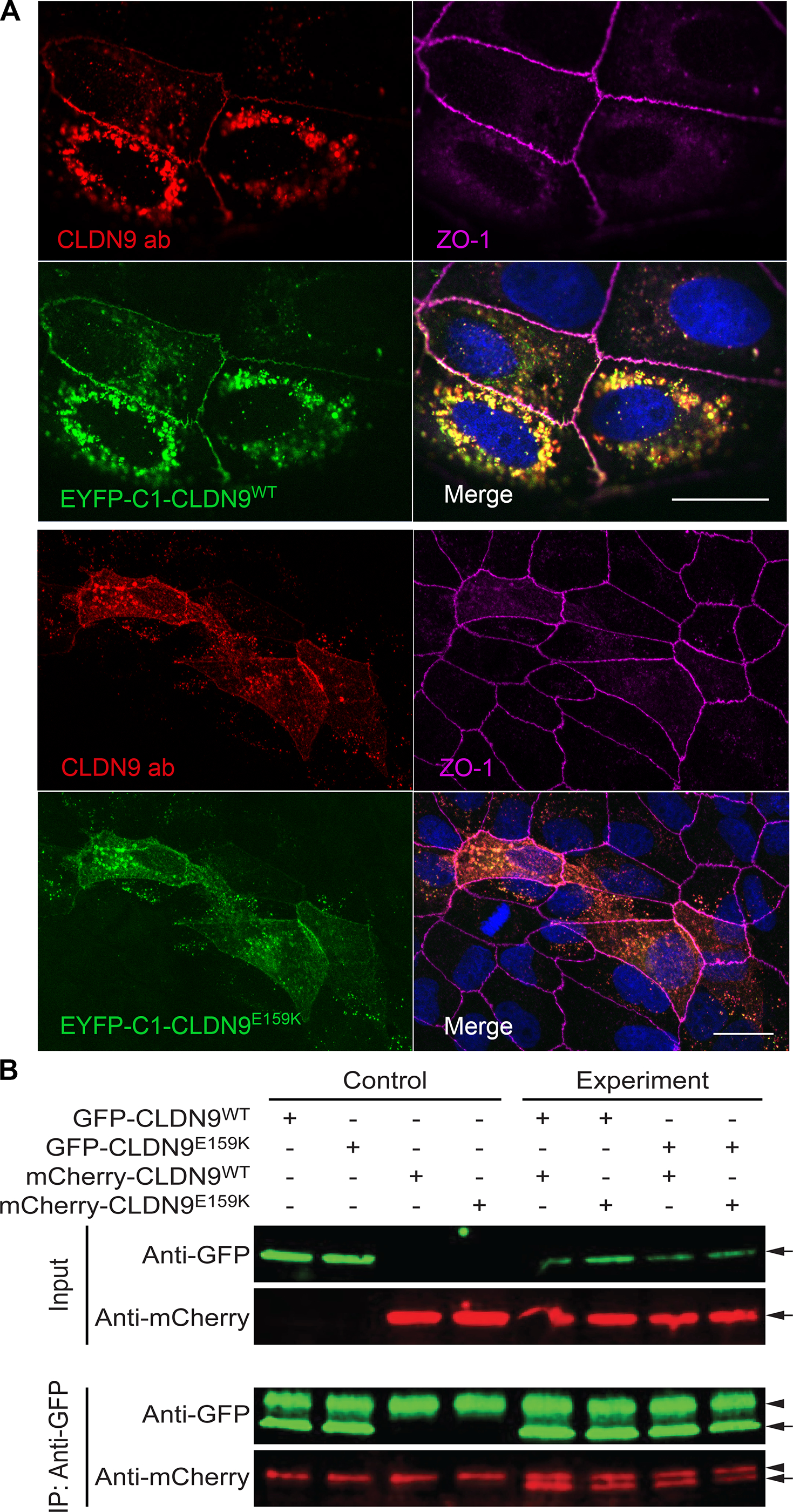

2.11. Co-immunoprecipitation assay

HeLa cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were plated in a 100 mm dish at 80–90% confluency for 24 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. The CLDN9WT or CLDN9E159K expression constructs tagged with both EGFP and mCherry were transfected into HeLa cells in different combinations. Transfection was done by using 10 μg of total DNA and 1 mg/ml polyethyleneimine (PEI) (Millipore) in a 1:3 ratio. Agarose beads were coated with an anti-GFP antibody. For this purpose, 80 mg of Protein A-Sepharose 4B (17078001, GE Healthcare, USA) was hydrated in 5 ml of Milli-Q water for 10 minutes with continuous agitation. It was then centrifuged at 500g for 1 minute (Centrifuge Avanti J-E, Beckman Coulter, USA). The supernatant was discarded and beads were washed once with 5 ml of 1x PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBSTx) and finally resuspended in 500 μl of PBSTx, making 1 ml of 50% slurry. 25 μl of anti-GFP antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the slurry and incubated at 4°C with continuous agitation for 4 hours. The beads were washed with PBSTx three times and centrifuged at 500g for 1 minute (Centrifuge 5418R, Eppendorf, USA). Beads were resuspended in a final volume of 1 ml and a 100 μl aliquot of the well-suspended slurry was added into a separate microcentrifuge tube for each control and test sample.

Cells were harvested 48 hours post-transfection in 1 ml of PBSTx containing a Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (#78425, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were disrupted with a sonic dismembrator (#D100, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at an intensity setting of 4, for three 10-second pulses with a 10-second interval between each pulse. The lysate was cleared by centrifuging at maximum speed at 4°C for 15 minutes (Centrifuge 5418R, Eppendorf). 100 μl of cleared lysate was saved for input, while the remaining lysate was added to the Anti-GFP Agarose beads and was incubated at 4°C overnight with continuous agitation. After incubation, the beads were centrifuged at 1000g for 1 minute and were washed with PBSTx thrice and finally heated at 95°C for 5 minutes in 2x Laemmli sample buffer (#1610737, BioRad, USA). The samples were electrophoresed on 4% - 20% SDS PAGE gels, transferred onto PVDF membrane and probed with anti-GFP (#A-11122, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and anti-mCherry antibodies (#MAB131873, Sigma-Aldrich) (1:1000) and counter probed with StarBright™ Blue 700 Goat Anti-Rabbit (#12004161, BioRad) and DyLight 800 Goat Anti-Mouse (#SA5–10176, Thermo Fisher Scientific) antibodies (1:2000) respectively, using an iBind western blot system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The blots were imaged with ChemiDoc™ MP Imaging System (#12003154, BioRad).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical findings

Audiometric testing in family HLRBS10 revealed asymmetric moderate to profound and moderate to severe bilateral hearing loss in the affected individuals IV:2 and IV:3, respectively (Figure 1C). The parents indicated that their children had a prelingual hearing loss. Romberg and tandem gait tests in both individuals revealed a grossly normal balance function. Tinnitus was not reported by these individuals. The audiological examination in family F7285 revealed asymmetric mild to profound hearing loss in the two affected individuals (Figure 1D). The hearing loss was mild to begin with for the proband (IV:4; age 35 years), however, it gradually progressed over a period of 16 years to moderate. Her hearing loss was first noticed at the age of 17 years and it worsened progressively. Thus, the onset of hearing loss may have been at an earlier age. She also reported the presence of tinnitus. The second affected individual (IV:3; age 40 years), did not participate in the molecular genetic study, but was evaluated by audiometry.

She had mild to profound hearing loss (Figure 1D) but no complaints of tinnitus or vertigo; her hearing loss was noticed already in early childhood. The degree of hearing loss in both individuals was worse at the higher frequencies as compared to the low frequencies (Figure 1D). Physical examinations and medical histories in both families did not reveal other clinically relevant phenotypes and carriers of the variants were asymptomatic (Figure 1A, 1B).

3.2. Molecular findings

Exome sequencing data of the affected individual of family HLRBS10 was analyzed. A homozygous variant was identified in the CLDN9 gene (NM_020982.4), which was predicted to be pathogenic. A total of four bi-allelic variants and one hemizygous variant in genes not previously associated with deafness were also identified in the data of this individual (Supp. Table S1). Sanger sequencing of the single coding exon of CLDN9 (Figure 1E) in all participants of the family revealed co-segregation of the c.475G>A;p.(Glu159Lys) variant with the deafness. The unaffected parents and sibling were heterozygous and both affected individuals were homozygous for the p.(Glu159Lys) variant (Figure 1A). The variant was submitted to ClinVar database under accession number SCV000998966.1. The remaining five variants in genes located on five different chromosomes were excluded based on their non-segregation with the phenotype or low conservation in vertebrate orthologues (Supp. Table S1). Moreover, genome-wide homozygosity analysis by AutoSNPa and segregation analysis of additional 14 SNPs in all members of family HLRBS10 identified linkage of the phenotype only to markers in the region on chromosome 16 containing the CLDN9 gene (Supp. Table S2).

The c.475G>A;p.(Glu159Lys) CLDN9 variant identified in affected members of family HLRBS10 was not detected in 173 ethnically matched control Pakistani individuals (346 chromosomes) and at the time of this analysis was absent from all public databases including gnomAD and Greater Middle East (GME) variome. The substitution of a lysine for glutamate at this position is predicted to be damaging (Table 1).

Table 1:

Segregating variants in CLDN9 identified after exome sequencing

| Family ID | HLRBS10 | F7285 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| †Variant | c.475G>A p.Glu159Lys | c.370_372dupATC p.Ile124dup |

|

| gnomAD | Not reported | 0.00002 | |

| *Control Frequency | 0/173 | 0/103 | |

| CADD score | 32 | N/A | |

| REVEL score | 0.92 | N/A | |

| MutationTaster | Prediction | Disease causing | Disease causing |

| Score | 1 | 1 | |

| PROVEAN | Prediction | Deleterious | N/A |

| HumVar Score | 0.99 | N/A | |

| SIFT | Prediction | Damaging | N/A |

| Score | 0.001 | N/A | |

| PolyPhen-2 | Prediction | Damaging | N/A |

| Score | 1 | N/A |

Based on CLDN9 transcript NM_020982.4.

173 controls from Pakistan and 103 individuals from Morocco were genotyped for the respective variants. gnomAD; genome aggregation database, CADD; Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (https://genome.ucsc.edu/), REVEL; Rare Exome Variant Ensemble Learner (http://sites.google.com/site/revelgenomics/), PROVEAN; Protein Variation Effect Analyzer, SIFT; Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant, PolyPhen-2; Polymorphism Phenotyping version 2, N/A; Not Applicable.

To identify the hearing loss-causing gene variant in family F7285, we sequenced the exome of the affected individual IV:4 (Figure 1B). This analysis revealed that IV:4 is homozygous for an in-frame duplication of a codon in CLDN9 (c.370_372dupATC) with no other pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in genes known to be involved in deafness. Sanger sequencing confirmed that IV:4 is homozygous for CLDN9 c.370_372dupATC (Figure 1F). The other affected individual from family F7285 (i.e., IV:3) did not consent to genetic analysis, and none of the consenting unaffected individuals were homozygous for the same variant (Figure 1B). These data suggest that CLDN9 c.370_372dupATC co-segregates with hearing loss in the F7285 family. The frequency of the c.370_372dupATC CLDN9 allele is low in the gnomAD and ExAC databases (0.00002), and neither database contains CLDN9 sequences from individuals who are homozygous for it. This variant was also not detected in gDNA of 206 chromosomes from 103 ethnically matched subjects from Morocco. MutationTaster predicted the p.(Ile124dup) variant to be damaging (Table 1), which supports its likely pathogenicity. This variant was submitted to ClinVar with accession number SUB7928387.

3.3. Conservation analysis of Glu159

Multiple protein sequence alignments of CLDN9 from different vertebrates, as well as among different claudin proteins, revealed that glutamate residue at position 159 of CLDN9 is located in a highly conserved extracellular loop 2 (EL2) near the C-terminus of the protein (Figure 1G and H).

3.4. Computational structural modeling of the consequences of p.(Glu159Lys) and p.(Ile124dup) on claudin 9

The interaction interface of the hCLDN9 cis-1 dimer is formed by conserved residues among claudins and includes an interaction between the serine-69 and glutamate-159 residues (Figure 2A), which was reported to be crucial for strand formation of mouse CLDN15 (Zhao et al., 2018). The electrostatic potential at the cis-1 interface of wild-type hCLDN9 shows a complementarity that is disrupted when a lysine substitutes for the wild-type glutamate-159. The presence of a lysine at position 159 shifts the electrostatic potential from negative to highly positive, possibly destabilizing this cis-1 interaction with serine-69 (Figure 2B). For the variant of human CLDN9 that results in a duplication of isoleucine-124, the extra isoleucine introduces a bulky hydrophobic group in a region where the packing is already tight with glycine and alanine residues (Figure 3A). In the first of two models for the variant p.(Ile124dup), the insertion of an extra isoleucine produces steric hindrance between the side chain of the inserted residue and alanine-91 and leucine-174 (Figure 3B). However, in the second model where the insertion of another isoleucine at position 124 alters the structure; the steric clash occurs between the side chain of the inserted isoleucine with alanine-14 and glycine-94 (Figure 3C). These steric clashes due to hydrophobic side chains that are too close to each other may locally destabilize a fold of claudin 9 (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 2:

Computational modeling of human claudin 9 wild-type and mutant dimers. A, Glu-159 (E159), located in one protomer (orange in A), establishes an interaction with Ser-69 of the adjacent protomer (blue) at the dimer cis-1 interface. These residues are part of an interaction network, comprised of highly conserved residues. Both protomers in the dimer (A) are represented as cartoon (colored blue and yellow on the left and by magenta and turquoise on the right). Residues located at the interface are shown as sticks. B, The electrostatic potential at the interface between protomers (Ser-69 and Glu-159 sides or faces) for the wild-type (WT) and the Glu159Lys mutant is mapped onto the surface representation of a single protomer (B), where the residues at positions 69 and 159 are indicated as blue and orange arrows respectively. The presence of lysine (K) at position 159 shifts the electrostatic potential from negative (red) to highly positive (blue).

FIGURE 3:

Computational modeling of human claudin 9 with Ile124 duplication. A, The model highlights the location of key residues (shown as yellow sticks) in the helix where the Ile124 duplication (I124dup) occurs (helix shown as a yellow cartoon). These highlighted residues are involved in the packing between helices. B, Overview of the residues forming the internal interacting network around Ile-124 or Ile124dup for each model. C, A close-up view of the interacting network, showing the predicted effect of Ile124dup on altering the protein structure due to the steric clash of the inserted isoleucine with alanine-14 and glycine-94.

3.5. Expression of claudin 9 mRNA in the mouse inner ear

Cldn9 mRNA expression was detected in the cochlear end-organs of the mouse inner ear (Figure 4). Using single molecule in situ hybridization (RNAscope probes) Cldn9 mRNA was observed in the outer and the inner hair cells, the supporting cells, the stria vascularis and in the Reissner’s membrane, during both the embryonic development and in the adult mouse (Figure 4). We next investigated whether or not Cldn9 probe might also be detecting Cldn6 mRNA since Cldn9 has a similar sequence to Cldn6. However, our findings showed that the patterns of expression of Cldn6 and Cldn9 are different. Cldn6 expression is detected in the supporting cells, the stria vascularis and the Reissner’s membrane at E14.5 to P3. Furthermore, expression of Cldn6 in both the outer and the inner hair cells was detected only in the embryonic stages while none was apparent in the adult cochlea at P30 when Cldn9 mRNA was still easily detected (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4:

Expression patterns of claudin 9 in mouse inner ear. Cldn9 (Probe-Mm-Cldn9, Red) is expressed in the outer and inner hair cells, supporting cells, stria vascularis and Reissner’s membrane at embryonic (E) days E14.5, E18.5, and postnatal (P) days P3 and P30. The intensity of the signal detecting Cldn9 increases from E14.5 to P3 and then decreases from P3 to P30. Expression of Cldn6 (Probe-Mm-Cldn6–01-C3, blue) in supporting cells, stria vascularis and Reissner’s membrane is present at E14.5, E18.5 and P3, while in the outer and inner hair cells, Cldn6 is expressed only embryonically based on analyses at ages E14.5 and E18.5. No Cldn6 signal is detected in the entire organ of Corti at P30. Hair cells were labeled using Myo7a (Probe-Mm-Myo7a-C2, green) at the ages E18.5, P3 and P30. Scale bars are 50 μm in panels and 10 μm in insets. SV; stria vascularis, RM; Reissner’s membrane, OC; organ of Corti, OHC; Outer Hair Cells, IHC; Inner Hair Cells.

The localization of endogenous CLDN9 protein (NP_064689) was also examined in postnatal mice using rabbit polyclonal anti-CLDN9 antibody validated by immunostaining of CLDN9-transfected and non-transfected MDCK-II cells (see Materials and Methods, section 2.8). Staining with the antibody revealed that CLDN9 was present in all sensory and non-sensory epithelial cells facing the endolymph within the scala media, where the sensory epithelium of the inner ear is located (Figure 5). This observation is similar to that reported earlier (Kitajiri et al., 2004).

FIGURE 5:

Localization of CLDN9 in mouse inner ear detected by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. CLDN9 is present in tight junctions of P6 C57BL/6J mouse outer and inner hair cells as well as in all non-sensory cells outlining scala media, including marginal cells of stria vascularis and the epithelial cells of the Reissner’s membrane. CLDN9 antibody labeling is shown in green, anti-ZO-1 antibody labeling is in red. Yellow indicates a merged signal from both antibodies, indicating the co-localization of the two detected proteins. Scale bar is 10 μm. * indicates outer hair cells and • indicates rows of inner hair cells.

3.6. Effect of p.Glu159Lys on the localization of CLDN9 and transepithelial resistance

When an expression vector encoding wild-type hCLDN9 was transfected in MDCK-II cells, CLDN9 protein localized to the cell membrane at cell-cell junctions (Figure 6A). The missense variant p.(Glu159Lys) did not affect the targeting of CLDN9 to the cell membrane (Figure 6A). To test the effect of p.(Glu159Lys) substitution on the ion barrier function of CLDN9, we generated stable clones of MDCK-II cells that expressed either wild-type CLDN9 (CLDN9WT) or its p.(Glu159Lys) variant (CLDN9E159K). EYFP was fused inframe to the N-termini of CLDN9WT and CLDN9E159K that were expressed in stable clones of MDCK-II cells. An N-terminal EYFP tag does not impair barrier function of CLDN9 (Nakano et al., 2009) and helps visualize wild-type and mutant CLDN9 expression. Monolayer cultures of these stable clones were used for measurements of transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER). These assays revealed that the expression of CLDN9WT and CLDN9E159K increased TEER (Supp. Figure S2A), and that the extent of the TEER increase was similar in the CLDN9WT-expressing and CLDN9E159K-expressing cultures (Supp. Figure S2B). The same cultures were also used for paracellular tracer flux assays. Specifically, the apical-to-basolateral diffusion of 4 kDa FITC-dextran (FD4) was measured. These assays demonstrated that the expression of CLDN9WT and CLDN9E159K increased the transepithelial flux of FD4 approximately 2-fold (Supp. Figure S2C). Thus, CLDN9WT and CLDN9E159K increased paradoxically both TEER and FD4 permeability in MDCK-II cell cultures, consistent with previously reported effects of CLDN1 overexpression in the same cell type (McCarthy et al., 2000). The CLDN9WT- and CLDN9E159K-dependent increase in FD4 permeability was not related to a potential increase in transcytosis, because CLDN9WT and CLDN9E159K did not affect transepithelial diffusion of a large dextran (500 kDa) that is excluded from the paracellular route (Supp. Figure S2C). Thus, TEER and tracer flux assays in a heterologous expression system did not reveal a difference in the barrier functions of CLDN9WT and CLDN9E159K.

FIGURE 6:

Localization of overexpressed wild-type and mutant CLDN9 in MDCK-II cells and a pulldown assay showing that cis-interaction of CLDN9 molecules is not affected by the Glu159Lys variant. A, Maximum intensity projection images for localization of CLDN9 in MDCK-II cells. Both wild-type (EYFP-C1-CLDN9WT) and mutant constructs (EYFP-C1-CLDN9E159K (Glu159Lys)) were targeted to the cell membrane and were present in the regions of cell-to-cell contact. ZO-1, a tight junction associated protein in the cell membrane (indicated in magenta), was used as a tight junction marker. Anti-CLDN9 antibody (CLDN9 ab, red) was used as an additional marker to detect EYFP-C1-CLDN9WT and EYFP-C1-CLDN9E159K (depicted in green). The localization of CLDN9 was not affected by Glu159Lys substitution as shown by the comparison of merged images (top and bottom panels). Scale bar is 20 μm in both panels. B, Lysates from HeLa cells transfected with both CLDN9WT and CLDN9E159K (Glu159Lys) tagged with EGFP or m-Cherry expression constructs in various combinations were used for co-IP assays with anti-GFP antibody-coated beads. Precipitates were immunoblotted with antibodies against EGFP and m-Cherry, expected sized bands were observed (arrows), Antibody heavy chain bands were also observed in all the pulldown sample lanes (arrowhead). CLDN9WT was able to pull down both CLDN9WT as well as CLDN9E159K. In addition, CLDN9E159K was also able to pull down CLDN9E159K, indicating that Glu159Lys change does not affect the claudin 9 cis-interaction.

3.7. p.(Glu159Lys) does not alter cis-interactions among Claudin 9

In order to investigate the effect of the Glu159Lys amino acid substitution on cis-interaction between two CLDN9 molecules, we performed a pull down assay using wild-type and mutant CLDN9. The CLDN9WT was able to pull down CLDN9WT as well as the CLDN9E159K without any remarkable difference (Figure 6B). Additionally, CLDN9E159K was also able to pull CLDN9E159K, indicating that the cis-interaction is not affected by the substitution of lysine at residue 159.

3.8. p.(Ile124dup) variant affects membrane targeting of CLDN9

HeLa cell transfection assays demonstrated that in contrast to wild-type mCherry tagged CLDN9 that can target the cell membrane, mCherry CLDN9 p.(Ile124dup) does not appear to have this ability. mCherry tagged CLDN9 accumulated in the cytoplasm showing a pattern reminiscent of the endoplasmic reticulum (Supp. Figure S3). These differences in targeting of the wild-type and p.(Ile124dup) CLDN9 argue for the pathogenicity of this CLDN9 variant.

4. DISCUSSION

Claudins are integral membrane proteins that contribute to semi-permeable, paracellular barriers at bicellular tight junctions (Zihni et al., 2016). In this study, we describe genetic and functional analyses of two bi-allelic variants of human CLDN9 associated with mild to profound hearing loss. Taken together with a previously reported frameshift variant of human CLDN9 (Sineni et al., 2019) and in combination with a deaf Cldn9 mutant mouse (Nakano et al., 2009), there is now strong evidence that pathogenic bi-allelic variants of CLDN9 cause human sensorineural deafness. Recently, a c.75C>G;p.(Cys25Trp) CLDN9 variant was suggested to cause fluctuating hearing loss with a steeply sloping audiogram in one individual (Santos-Cortez et al., 2021). The cysteine-25 is a highly conserved residue. The affected individual also had variants in FLNA and ANKRD11 and exhibited turbinate hypertrophy, allergic rhinitis and nasopharyngeal nodule. Additional experimental evidence would be useful in evaluating the predicted pathogenicity of the CLDN9 c.75C>G;p.(Cys25Trp) variant.

Our data describe a homozygous missense variant and a homozygous in-frame duplication of one amino acid in CLDN9 in affected individuals from two families. Similar to the report of young affected individuals with a frameshift variant of CLDN9 (Sineni et al., 2019), mild to moderate degrees of hearing loss at lower frequencies were observed in affected individuals of family HLRBS10 and F7285. However, progression of hearing loss was not observed over a period of 10 years for the affected members in family HLRBS10. We note that in family F7285, the hearing loss of IV:3 might have a different underlying cause than individual IV:4, and her audiometric data may not add to the phenotypic spectrum for CLDN9 defects. However, the hearing loss in the F7285 participant IV:4 due to the variant p.(Ile124dup) had an adolescent onset similar to that in affected members reported previously (Sineni et al., 2019). Additionally, the hearing loss in family F7285 was progressive in contrast to the stable hearing loss of the two affected individuals from family HLRBS10 with the p.(Glu159Lys) variant. Interestingly, in the one reported mouse model with a homozygous substitution p.(Phe35Leu) of CLDN9, the degeneration of hair cells occurs initially in the basal turn and gradually progresses with age to the apical turn leading to profound deafness (Nakano et al., 2009).

In a previous study, amino acids constituting the EL2 of CLDN5 were demonstrated to be involved in dimerization (Blasig et al., 2006). A number of residues in this second extracellular loop contains charged amino acids, including Glu159, which are thought to be important for dimerization of claudins (Gonzalez-Mariscal et al., 2003). Since the glutamic acid residue at the position 159 of EL2 is conserved in all claudin members, it was postulated that glutamic acid 159 may have an important role in claudin-claudin interactions as well. We observed that in silico prediction of the effect of Glu159 in CLDN9 indicated a disruption of the cis-interaction of the protein similar to a mutation of glutamic acid 157 of CLDN15 (Zhao et al., 2018). Although computational modelling predicted a disruption of cis-interaction, we obtained contrasting results from the co-immunoprecipitation and TEER assays. We speculate from the TEER data that the Glu159Lys-dependent alterations in the cis-interactions of CLDN9 cause only subtle defects in the ion barrier function of CLDN9. These defects are perhaps sufficiently mild to be compensated for by the high level of expression of CLDN9E159K in the transfected MDCK-II cells. Alternatively, MDCK-II cells may lack CLDN9-interacting proteins that make the inner-ear tight junctions especially sensitive to alterations at the cis-interface of CLDN9.

Our data show that overexpression of CLDN9WT and CLDN9E159K in MDCK-II cell cultures increases both TEER and transepithelial FD4 diffusion (Supp. Figure S2C). This parallel increase in TEER and FD4 permeability is consistent with the previously proposed model that small ions and larger (0.6–5 kDa) solutes traverse tight junctions via two separate routes (Sasaki et al., 2003; Weber et al., 2015). Specifically, whereas small ions may pass through paracellular channels formed by non-barrier type claudins (e.g., CLDN2), larger solutes are likely to pass through the leak pathway created by focal and transient openings in tight junction strands. We propose that overexpression of CLDN9WT and CLDN9E159K results in an increase in the number of transient openings in tight junction strands. These openings do not reduce the TEER because the open-close fluctuations are likely asynchronous in the stacked tight junction strands.

The co-immunoprecipitation assays indicated that the substitution of glutamic acid by lysine did not alter the cis-interactions in cell lines. In a previous study that examined the interaction between claudins, Glu159 of the extracellular loop 2 of CLDN5 was postulated to have a role in the formation of strands by interacting with claudins in the neighboring cell (Piontek et al., 2008). A Glu159Gln substitution at the same position in CLDN5 neither affected the targeting of the protein to the plasma membrane, nor its cis-interaction with other CLDN5 molecules. However, Glu159Gln substitution in CLDN5 was reported to result in fewer and less complex tight junction strands, as compared to the wild-type, and not in a complete loss of strands (Piontek et al., 2008). Similarly, there is a possibility that the substitution of lysine at residue 159 in CLDN9 may reduce and not eliminate the ability of CLDN9 to form tight junction strands.

Coinciding with the development of tight junctions, Cldn9 mRNA was detected in the sensory and non-sensory epithelia of the mouse inner ear during embryonic development and in the adult. Immunostaining of the organ of Corti confirmed the presence of CLDN9 at tight junctions in all sensory and non-sensory cells that outline the scala media, results which are concordant to those reported earlier (Kitajiri et al., 2004). The localization of CLDN9 with the substitution of lysine at position 159 was similar to that of the wild-type, when expressed in MDCK-II cells. Similarly, the deafness-causing missense variant of mouse CLDN9 p.(Phe35Leu) does not affect the targeting of CLDN9 to the plasma membrane, but nevertheless results in hearing loss (Nakano et al., 2009). In contrast, the CLDN9 p.(Ile124dup) variant overexpressed in HeLa cells affects the ability of mutant CLDN9 to target the cell membrane and was retained in the cytoplasm, suggesting a pathogenic effect of this variant. In one previous study, the localization of the overexpressed CLDN9 protein with a frameshift variant was shown to be altered in HEK293 cells, and the truncated protein accumulated in the cytosol (Sineni et al., 2019). It is not known if in the inner ear truncated CLDN9 protein remained stable or was degraded. However, the truncated p.(Leu29Argfs4Ter) protein, even if stable, most probably is a functionally null allele.

Due to the ease of ascertainment, historically many genetic studies of recessively inherited human deafness have focused on cases of profound deafness to the neglect of less severe cases of hearing loss. Our work suggests that CLDN9 represents one of a few genes, variants of which should be considered for recessively inherited mild to moderate hearing loss in humans. By analyzing the genetic causes of moderate hearing loss, we expect that additional deafness-causing variants of CLDN9 will be identified. In summary, here we report families with two likely pathogenic CLDN9 variants both of which appear to be hypomorphic. Our data expand the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of CLDN9 variants in human sensorineural hearing loss. The findings of our cell-based experiments and structural modeling reveal likely mechanisms underlying CLDN9 related deafness, consistent with the retention of residual function in the inner ear of CLDN9 p.(Glu159Lys), and perhaps some deficiency in plasma membrane targeting of CLDN9 p.(Ile124dup). Identifying additional mutant alleles of CLDN9 and engineering animal models with the corresponding human variants could further our understanding of pathogenic mechanisms that expose therapeutic opportunities.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the family members for their participation in our study and are grateful to Drs. Ron Petralia and Wade Chien for critiques of our manuscript. This project was supported by grants from the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (3288), and (in part) from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health, USA (DC000039 to TBF), National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health, USA (R01DC014953 to BB), and INSERM UMR 1231 GAD, F-21000, Dijon, France. Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics performed whole-exome sequencing for family HLRBS10.

Funding Information:

Higher Education Commission, Pakistan (3288), National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health, USA (DC000039), National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health, USA (R01DC014953), Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics, and INSERM UMR 1231 GAD, F-21000, Dijon, France

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest

WEB RESOURCES

1000 Genomes Project database (https://www.internationalgenome.org/)

CADD (https://genome.ucsc.edu/)

ClustalO (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tool/msa/clustalo)

ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/)

Exome Aggregation Consortium database-disconitnued now- (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/)

genome Aggregation Database (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/)

Greater Middle East Variome database (http://igm.ucsd.edu/gme/)

HHpred Server (https://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/tools/hhpred)

MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/)

NCBI (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (https://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/)

PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/index.shtml)

Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/)

REVEL (http://sites.google.com/site/revelgenomics/)

SIFT (https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/)

UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/)

Uniprot (http://www.uniprot.org)

wANNOVAR (http://wannovar.usc.edu/)

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Supplementary data include two tables and three figures and are available online.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data in support of the findings presented in this work are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical concerns.

REFERENCES

- Ashkenazy H, Abadi S, Martz E, Chay O, Mayrose I, Pupko T, & Ben-Tal N (2016). ConSurf 2016: an improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(W1), W344–W350. 10.1093/nar/gkw408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda MS, & Matter K (2000). The tight junction protein ZO‐1 and an interacting transcription factor regulate ErbB‐2 expression. The EMBO journal, 19(9), 2024–2033. 10.1093/emboj/19.9.2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir R, Fatima A, & Naz S (2010). Mutations in CLDN14 are associated with different hearing thresholds. Journal of Human Genetics, 55(11), 767–770. 10.1038/jhg.2010.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yosef T, Belyantseva IA, Saunders TL, Hughes ED, Kawamoto K, Van Itallie CM, . . . Wilcox ER (2003). Claudin 14 knockout mice, a model for autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29, are deaf due to cochlear hair cell degeneration. Human Molecular Genetics, 12(16), 2049–2061. 10.1093/hmg/ddg210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasig IE, Winkler L, Lassowski B, Müller SL, Zuleger N, Krause E, . . . Piontek J (2006). On the self-association potential of transmembrane tight junction proteins. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences CMLS, 63(4), 505–514. 10.1007/s00018-005-5472-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr IM, Flintoff KJ, Taylor GR, Markham AF, & Bonthron DT (2006). Interactive visual analysis of SNP data for rapid autozygosity mapping in consanguineous families. Human Mutation, 27(10), 1041–1046. 10.1002/humu.20383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colegio OR, Van Itallie CM, McCrea HJ, Rahner C, & Anderson JM (2002). Claudins create charge-selective channels in the paracellular pathway between epithelial cells. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 10.1152/ajpcell.00038.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Coránguez M, Liu X, & Antonetti DA (2019). Tight junctions in cell proliferation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(23), 5972. 10.3390/ijms20235972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Fujita K, Hiiragi T, Fujimoto K, & Tsukita S (1998). Claudin-1 and-2: novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. The Journal of Cell Biology, 141(7), 1539–1550. 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Hirase T, Itoh M, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, & Tsukita S (1993). Occludin: A novel integral membrane protein localizing at tight junctions. The Journal of Cell Biology, 123(6), 1777–1788. 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Sasaki H, & Tsukita S (1999). Manner of interaction of heterogeneous claudin species within and between tight junction strands. The Journal of Cell Biology, 147(4), 891–903. 10.1083/jcb.147.4.891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Mariscal L, Betanzos A, Nava P, & Jaramillo BE (2003). Tight junction proteins. Prog Biophysics Molecular Biology, 81(1), 1–44. 10.1016/s0079-6107(02)00037-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A, Davies C, Southwood CM, Frolenkov G, Chrustowski M, Ng L, . . . Kachar B (2004). Deafness in Claudin 11-null mice reveals the critical contribution of basal cell tight junctions to stria vascularis function. Journal of Neuroscience, 24(32), 7051–7062. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1640-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand A, Remmert M, Biegert A, & Söding J (2009). Fast and accurate automatic structure prediction with HHpred. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 77(S9), 128–132. 10.1002/prot.22499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke K (1975). The fine structure of freeze-fractured intercellular junctions in the guinea pig inner ear. Acta Oto-laryngologica, 80(sup336), 5–40. 10.3109/00016487509125512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J, & Artursson P (1991). A method for the determination of cellular permeability coefficients and aqueous boundary layer thickness in monolayers of intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells grown in permeable filter chambers. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 71(1–2), 55–64. 10.1016/0378-5173(91)90067-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajiri S. i., Furuse M, Morita K, Saishin-Kiuchi Y, Kido H, Ito J, & Tsukita S (2004). Expression patterns of claudins, tight junction adhesion molecules, in the inner ear. Hearing research, 187(1–2), 25–34. 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00338-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, & Thornton JM (1993). PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. Journal of applied crystallography, 26(2), 283–291. 10.1107/S0021889892009944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latief N, Belyantseva IA, Iqbal F, Riazuddin SA, Khan SN, Friedman TB, . . . Riazuddin S (2013). Phenotypic variability of CLDN14 mutations causing DFNB29 hearing loss in the Pakistani population. Journal of Human Genetics, 58(2), 102–108. 10.1038/jhg.2012.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Ansar M, Andrade PB, Khan B, Santos‐Cortez RLP, Ahmad W, & Leal SM (2012). Novel CLDN14 mutations in Pakistani families with autosomal recessive non‐syndromic hearing loss. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 158(2), 315–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoli M, Van Camp GUY, Newton V, N, G., F, D., & Parving A (2003). Recommendations for the description of genetic and audiological data for families with nonsyndromic hereditary hearing impairment. Audiological Medicine, 1(2), 148–150. 10.1080/16513860301713 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy K, Francis S, McCormack J, Lai J, Rogers R, Skare I, . . . Schneeberger E (2000). Inducible expression of claudin-1-myc but not occludin-VSV-G results in aberrant tight junction strand formation in MDCK cells. Journal of Cell Science, 113(19), 3387–3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo F, Sánchez R, & Sali A (2002). Statistical potentials for fold assessment. Protein Science, 11(2), 430–448. 10.1002/pro.110430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Kim SH, Kim H-M, Sanneman JD, Zhang Y, Smith RJ, . . . Bánfi B (2009). A Claudin-9–based ion permeability barrier is essential for hearing. PLoS Genetics, 5(8), e1000610. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pater JA, Benteau T, Griffin A, Penney C, Stanton SG, Predham S, . . . Li Q (2017). A common variant in CLDN14 causes precipitous, prelingual sensorineural hearing loss in multiple families due to founder effect. Human Genetics, 136(1), 107–118. 10.1007/s00439-016-1746-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piontek J, Krug SM, Protze J, Krause G, & Fromm M (2020). Molecular architecture and assembly of the tight junction backbone. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes, 183279. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piontek J. r., Winkler L, Wolburg H, Muller SL, Zuleger N, Piehl C, . . . Blasig IE (2008). Formation of tight junction: Determinants of homophilic interaction between classic claudins. The FASEB Journal, 22(1), 146–158. 10.1096/fj.07-8319com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remmert M, Biegert A, Hauser A, & Söding J (2012). HHblits: Lightning-fast iterative protein sequence searching by HMM-HMM alignment. Nature Methods, 9(2), 173. 10.1038/nmeth.1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šali A, & Blundell TL (1993). Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. Journal of Molecular Biology, 234(3), 779–815. 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Cortez RLP, Yarza TKL, Bootpetch TC, Tantoco M, Leah C, Mohlke KL, . . . Lee NR (2021). Identification of novel candidate genes and variants for hearing loss and temporal bone anomalies. Genes, 12(4), 566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Matsui C, Furuse K, Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Furuse M, & Tsukita S (2003). Dynamic behavior of paired claudin strands within apposing plasma membranes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(7), 3971–3976. 10.1073/pnas.0630649100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sineni CJ, Yildirim-Baylan M, Guo S, Camarena V, Wang G, Tokgoz-Yilmaz S, . . . Tekin M (2019). A truncating CLDN9 variant is associated with autosomal recessive nonsyndromic hearing loss. Human Genetics, 1–5. 10.1007/s00439-019-02037-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobreira N, Schiettecatte F, Valle D, & Hamosh A (2015). GeneMatcher: A matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Human Mutation, 36(10), 928–930. 10.1002/humu.22844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervonen A, Ihalainen TO, Nymark S, & Hyttinen J (2019). Structural dynamics of tight junctions modulate the properties of the epithelial barrier. PLoS One, 14(4), e0214876. 10.1371/journal.pone.0214876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevenon J, Duffourd Y, Masurel‐Paulet A, Lefebvre M, Feillet F, El Chehadeh‐Djebbar S, . . . Chouchane M (2016). Diagnostic odyssey in severe neurodevelopmental disorders: toward clinical whole‐exome sequencing as a first‐line diagnostic test. Clinical Genetics, 89(6), 700–707. 10.1111/cge.12732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Itallie CM, & Anderson JM (2006). Claudins and epithelial paracellular transport. Annual Reviews Physiology, 68, 403–429. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.131404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber CR, Liang GH, Wang Y, Das S, Shen L, Alan S, . . . Turner JR (2015). Claudin-2-dependent paracellular channels are dynamically gated. Elife, 4, e09906. 10.7554/eLife.09906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox ER, Burton QL, Naz S, Riazuddin S, Smith TN, Ploplis B, . . . Morell RJ (2001). Mutations in the gene encoding tight junction claudin-14 cause autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29. Cell, 104(1), 165–172. 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00200-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Krystofiak ES, Ballesteros A, Cui R, Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM, . . . Kachar B (2018). Multiple claudin–claudin cis interfaces are required for tight junction strand formation and inherent flexibility. Communications Biology, 1(1), 50. 10.1038/s42003-018-0051-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zihni C, Mills C, Matter K, & Balda MS (2016). Tight junctions: from simple barriers to multifunctional molecular gates. Nature Reviews Molecular cell biology, 17(9), 564. 10.1038/nrm.2016.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data in support of the findings presented in this work are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical concerns.