Abstract

Objectives:

Although patients with cirrhosis often experience debilitating symptoms, few are referred for palliative care. Frailty is increasingly incorporated in liver transplantation evaluation and has been associated with symptom burden in other populations. We hypothesized that frail patients with cirrhosis are highly symptomatic and thus are likely to benefit from palliative care.

Methods:

Patients with cirrhosis undergoing outpatient liver transplantation evaluation completed the Liver Frailty Index (LFI; grip strength, chair stands, and balance) and a composite of validated measures including the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), distress and quality of life (QOL) measures.

Results:

Of 233 patients (median age 61 years, 43% female), 22% were robust, 59% pre-frail and 19% frail. Overall, 38% of patients reported ≥1 severe symptoms based on preestablished ESAS criteria. Higher frailty categories were associated with increased prevalence of pain, dyspnea, fatigue, nausea, poor appetite, drowsiness, depression and poor wellbeing (test for trend, all p<0.05). Frail patients were also more likely to report psychological distress and poor QOL (all p<0.01). In univariate analysis, each 0.5 increase in LFI was associated with 44% increased odds of experiencing ≥1 severe symptoms (95% CI: 1.2–1.7, p<0.001), which persisted (OR 1.3, 95% CI: 1.0–1.6, p=0.004) even after adjusting for Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and age.

Conclusion:

In patients with cirrhosis, frailty is strongly associated with physical/psychological symptoms including pain and depression, and poor QOL. Frail patients with cirrhosis may benefit from palliative care co-management to address symptoms and improve QOL.

Keywords: Physical function, Quality of life, Distress, Pain, Psychosocial

INTRODUCTION

The clinical course of patients with end stage liver disease (ESLD) is characterized by progressive decline and episodic exacerbations that can result in rapid deterioration and death. Patients often experience debilitating symptoms, including pain, anorexia, and depression, as well as poor quality of life (QOL) [1–4]. Unfortunately, many patients with ESLD are not eligible for liver transplantation or die while on the waiting list. Although emerging data suggests that palliative care can improve symptoms and QOL in this population, few patients are currently referred to palliative care [5–8]. Therefore, we need establish systems to routinely screen and identify patients who are appropriate for palliative care.

Frailty is increasingly recognized to have an important impact on patient outcomes and has been associated with increased hospitalizations, waitlist mortality, and physical function after transplant in patients with cirrhosis [9–11]. Although the relationship between frailty and symptoms has not been established in patients with cirrhosis, studies in other populations suggest that frailty is not only associated with increased symptom burden, but that the relationship may be bidirectional [12–14]. We hypothesized that frailty would be associated with patient-reported symptoms and thus may help to identify patients likely to benefit from palliative care co-management.

The objectives of this study were to 1) assess the symptom burden, distress, and QOL in patients with cirrhosis and 2) investigate the correlation of these symptoms with frailty.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study population

Adult patients with cirrhosis undergoing outpatient evaluation for liver transplantation from 7/1/19 – 9/30/19 were eligible for inclusion. Patients underwent informed consent, and the study was approved by our institutional ethics review board (IRB #11–07513). Patients were excluded if they had severe hepatic encephalopathy, as defined as a Numbers Connection Test time >120 seconds (given concerns regarding ability to comply with performance-based tests of frailty), and if they did not speak English or Spanish given the lack of availability of the symptom assessment instruments in other languages.

Study measures

Frailty was assessed using the Liver Frailty Index (LFI), a validated measure of physical function in patients with cirrhosis [15]. Patients were instructed by trained study personal to complete three performance-based tests: grip strength, chair stands, and balance. The LFI was calculated using the online calculator: https://liverfrailtyindex.ucsf.edu. LFI scores were then stratified by frailty category using previously established LFI cut-points: robust (<3.2), pre-frail (3.2–4.3), and frail (≥4.4) [15,16].

To characterize symptom burden, patients completed the Palliative Care Quality Network Symptom and Well-being Survey, which is a composite of validated measures including the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer, and single-item spiritual distress and QOL measures [17]. The ESAS is a 9-item self-report scale commonly used to assess symptoms in palliative care [18–20]. For each symptom, patients rate how they are feeling now from 0 (no symptom) to 10 (worst possible symptom) on a 11-point numeric rating scale. In the ESAS, a moderate symptom is defined as score 4–6 and a severe symptom as score 7–10 [21,22]. A symptom score ≥4 (moderate to severe) is recommended as a trigger for more comprehensive assessment in the clinical setting [21]. The presence of one or more severe symptoms (ESAS score ≥ 7) has been associated with patient-reported high symptom burden and decreased physical, emotional, and social functioning [23]. ESAS can be further divided into a physical symptom subscale (pain, fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, poor appetite, and dyspnea) and psychological symptom subscale (depression and anxiety) [20].

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress thermometer is a tool frequently used in cancer populations to screen for psychological distress [24]. Patients rate their current level of distress on a numeric rating scale ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress), with a positive screen defined as score ≥ 4 [25]. Spiritual distress was assessed using a one-item descriptive rating scale: “Are you at peace?” [26] Lack of spiritual distress was defined by selections of “not at all” or “a little bit,” while spiritual distress was considered “a moderate amount,” quite a bit,” or “completely.” Finally, patients completed a single global QOL item [27,28]. Responses were categorized in three tiers: 1) Poor or very poor, 2) Fair, 3) Good or excellent.

Medical records were reviewed to collect demographic information and clinical data, including etiology of liver disease, history of hepatocellular carcinoma, and presence of ascites. Hepatic encephalopathy was categorized as present if ≥60 seconds were needed to complete the Numbers Connection Test A [29]. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium (MELDNa) was calculated from labs collected within 6 months of study visit.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized by medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables or numbers with percentages for categorical variables. Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics were stratified by severe symptoms (one or more ESAS score ≥7) using chi-square tests and Fisher exact tests (<5 events) for categorical variables and Mann Whitney U tests for non-parametric continuous variables. We compared differences in ESAS symptom scores, spiritual and psychological distress, and QOL by frailty categories using test for trend.

A multivariate model was constructed to identify variables that were independently associated with reporting ≥1 severe symptoms. Bivariate analyses were performed on variables identified a priori as potentially associated with severe symptoms: LFI, age, MELDNa, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy. These variables, regardless of p-value in the bivariate analyses, were then entered in a forward stepwise regression model in order of increasing significance. Subgroup analyses were performed in patients with and without ascites or hepatic encephalopathy, and low and high MELDNa as defined by the 75th percentile score.

An alpha of <0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

RESULTS

Baseline Patient Characteristics

Of 233 patients enrolled in the study, the median age was 61 (IQR 54–65), 99 (43%) were female, 42 (18%) were non-white, and 191 (82%) were listed for transplant. The median MELDNa was 15 (IQR 11–19). The median LFI was 3.8 (IQR 3.3–4.2); according to LFI cut-offs, 52 (22%) were robust, 138 (59%) pre-frail, and 43 (19%) frail (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study sample stratified by symptom burden

| N = 233 Median (IQR) or n (%) | Mild/moderate symptoms | Severe symptom(s)† | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, years | 61 (54–65) | 62 (54–66) | 60 (55–65) | 0.52 |

| Female | 99 (43) | 54 (38) | 45 (50) | 0.09 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 191 (82) | 114 (80) | 77 (85) | |

| Black | 10 (4) | 6 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Asian | 25 (11) | 19 (13) | 6 (7) | |

| Native American | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0.41 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29 (25–33) | 28 (25–33) | 29 (25–33) | 0.34 |

| Primary etiology of cirrhosis | ||||

| Hepatitis C | 75 (32) | 44 (31) | 31 (34) | |

| Alcohol | 63 (27) | 30 (28) | 24 (26) | |

| NASH | 50 (22) | 27 (19) | 23 (25) | |

| Cholestatic | 17 (7) | 13 (9) | 4 (4) | |

| Hepatitis B | 7 (3) | 6 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| Other | 21 (9) | 13 (9) | 8 (9) | 0.45 |

| Dialysis | 10 (4) | 5 (4) | 5 (6) | 0.47 |

| Ascites | 37 (16) | 16 (11) | 21 (23) | 0.02 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 43 (19) | 21 (15) | 22 (24) | 0.07 |

| HCC | 77 (33) | 52 (37) | 25 (28) | 0.15 |

| Listed for transplant | 191 (82) | 116 (82) | 75 (82) | 0.89 |

| MELDNa | 15 (11–19) | 14 (11–19) | 18 (14–20) | <0.001 |

| Liver Frailty Index | 3.76 (3.26–4.23) | 3.61 (3.01–4.05) | 4.00 (3.41–4.49) | <0.001 |

| Robust | 52 (22) | 41 (29) | 11 (12) | |

| Pre-frail | 138 (59) | 86 (61) | 52 (57) | |

| Frail | 43 (19) | 15 (11) | 28 (31) | <0.001 |

Severe symptom(s) = 1 or more Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale score ≥7

BMI=body mass index, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, IQR=interquartile range, MELDNa=Model for End-Stage Liver Disease–sodium, NASH=Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

Symptom Burden

The prevalence of moderate to severe symptoms were as follows: fatigue (47%), poor well-being (42%), pain (35%), poor appetite (35%), drowsiness (30%), anxiety (23%), dyspnea (20%), depression (17%), and nausea (11%). Overall, 91 (39%) of patients reported one or more severe symptoms. Likelihood of having severe symptom(s) did not differ by demographic factors such as age, gender, race or by whether patients were listed for transplant (all p>0.09) (Table 1).

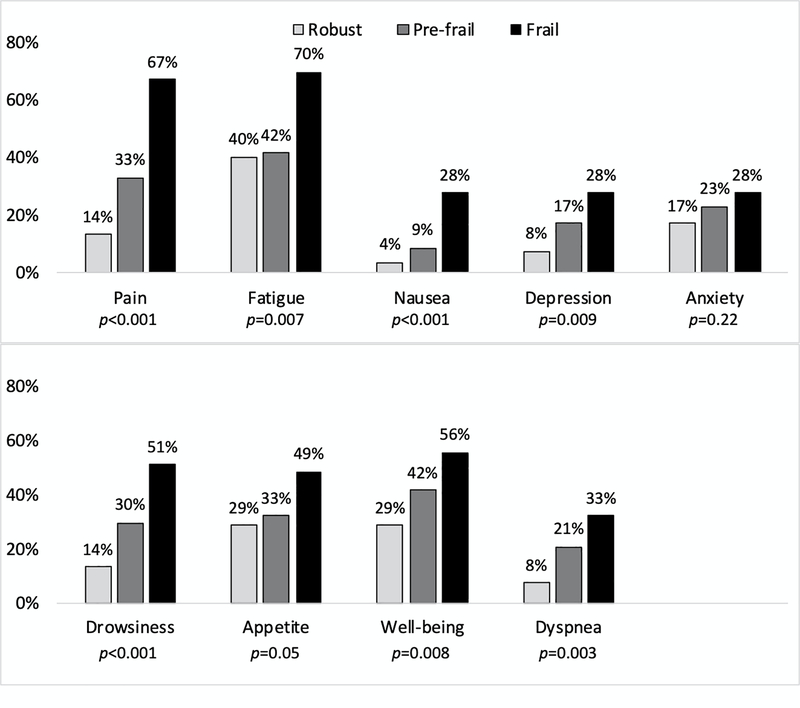

Higher frailty categories were significantly associated with increased prevalence of moderate to severe pain, dyspnea, fatigue, nausea, poor appetite, drowsiness, depression, and poor well-being (Figure 1). Additionally, frailty was associated with higher scores on the ESAS physical symptom subscale (IRR [Incidence rate ratio] 1.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.3–1.9, p<0.001) as well as the psychological symptom subscale (IRR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.7, p<0.03). Overall, frail patients were more likely to report one or more severe symptoms (robust: 21% vs. pre-frail: 38% vs. frail: 65%, p<0.001), as well as increased mean (standard deviation) total number of severe symptoms (robust: 0.5 [1.5] vs. pre-frail 0.8 [1.3] vs. 2.0 [2.2], p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Moderate to severe symptoms by frailty status

In univariate analysis, each 0.5 unit increase in LFI was associated with 44% increased odds of experiencing one or more severe symptom(s) (95% CI: 1.2–1.7, p<0.001). After adjusting for MELDNa, ascites, HE, and age, LFI was the only variable significantly associated with the severe symptom group (odds ratio [OR] 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.6, p=0.004) (Table 2). In subgroup analyses, LFI was no longer associated with severe symptom(s) in patients with ascites (OR 1.4, 95% CI 0.8–2.4, p=0.29) and hepatic encephalopathy (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.6–1.7), p=0.98), but remained significant in patients without ascites (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.6, p=0.006) and hepatic encephalopathy (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.2–1.8, p=0.001) and in patients with high MELDNa (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.7, p=0.009) and low MELDNa (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.6, p=0.02) (Supplementary Tables 1–2).

Table 2.

Forward stepwise regression of factors associated with severe symptom(s)

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

| Liver Frailty Index † | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) |

| MELDNa | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | |

| Ascites | 1.6 (0.7–3.4) | 1.5 (0.7–3.2) | 1.5 (0.7–3.3) | ||

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | |||

| Age | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | ||||

per 0.5-unit increase

MELDNa=Model for End-Stage Liver Disease–sodium, CI=confidence ratio, OR= Odds ratio

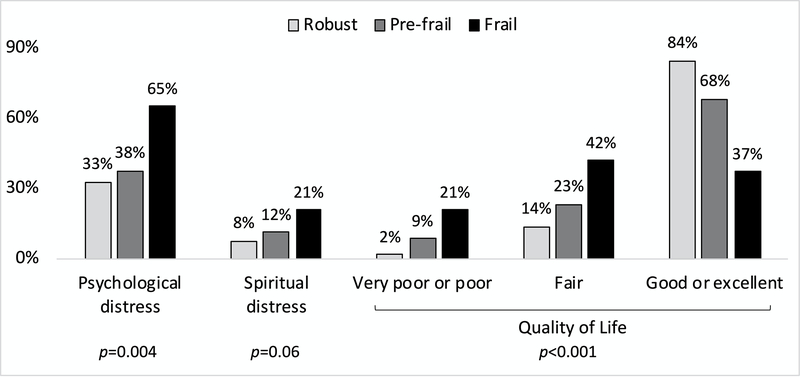

Distress and Quality of Life

Psychological distress was present in 98 (42%) of patients, and spiritual distress was present in 29 (12%) of patients. In terms of QOL, 153 (66%) reported good or excellent, 42 (25%) reported fair, and 22 (10%) reported poor or very poor. Frail patients were significantly more likely to report psychological distress and poor QOL, and there was a trend for increased spiritual distress (Figure 2). Patients who were listed for transplant compared with those who were not listed did not differ by self-reported psychological distress, spiritual distress, or QOL (all p>0.07).

Figure 2.

Distress and quality of life by frailty status

DISCUSSION

ESLD causes tremendous suffering, and when cure is only possible for a minority of patients, the goal of medical therapy should focus on aggressively managing symptoms, improving QOL, and optimizing function. There is emerging evidence showing that early palliative care decreases symptom burden, improves mood, and reduces resource utilization in patients with cirrhosis [5,30]. Unfortunately, outpatient palliative care is utilized infrequently and often too late, and no evidence-based guidelines yet exist to guide clinicians (e.g. hepatologists, primary care providers) in identifying patients with cirrhosis who are likely to benefit from palliative care [7,8]. Our study, demonstrating a strong association between physical frailty and symptom burden, raises the possibility that frailty may be considered an indicator for palliative care referral among patients with cirrhosis.

More than one-third of our study sample reported one or more severe symptoms. Similar to past studies, the most commonly reported symptoms were fatigue, poor well-being, pain, and poor appetite [31,32]. The high prevalence of pain in our study parallels prior research showing that rates of pain in patients with ESLD is comparable to that among patients with lung and colon cancer [3]. Notably, experiencing one or more severe symptoms is clinically meaningful as this group of highly symptomatic patients is likely to report significant impairments in physical, emotional, and social functioning [22].

Importantly, we found that symptom burden is strongly associated with frailty. Frail patients were more likely to report both physical and psychological symptoms as well as distress and poor QOL. Symptom burden increased in a “dose-dependent” fashion with worsening frailty. Compared to robust patients, frail patients had 2–3 times the rates of moderate to severe symptoms and increased total number of severe symptoms. Furthermore, frailty was associated with the severe symptom group as determined by ESAS score independent of MELDNa, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and age. In fact, MELDNa was not a good predictor of symptom burden, confirming prior reports [33–35].

Given the potential for portal hypertensive complications to drive the relationship between frailty and symptom burden in patients with cirrhosis, we conducted subgroup analyses to further explore our main research question. In subgroup analyses, we found that frailty was not associated with ESAS score among the subgroups of patients with ascites or hepatic encephalopathy. This is, perhaps, not unexpected, as these portal hypertensive complications likely drive the symptomatology experienced by these patients; patients with known ascites or hepatic encephalopathy are easily identified in clinical practice and may benefit from referral to palliative care based on these complications alone. However, we found that frailty remained strongly associated with symptom burden among those without ascites or hepatic encephalopathy. Assessment of frailty may add significant value to clinical practice to help identify patients in greatest need of palliative care who do not have obvious signs of clinical portal hypertension.

Overall, our findings suggest a patient’s global health and functional status is strongly correlated with symptom burden and QOL. Thus, frailty, which is increasingly utilized to predict waitlist mortality and post-transplant outcomes, is a good surrogate for symptom burden and should be considered as a trigger for palliative care referral in patients with cirrhosis [10–12]. Multiple frailty instruments have been established in the geriatric population, but the LFI is currently the only frailty assessment tool developed specifically for patients with cirrhosis. The LFI is a simple, objective metric that can be administered in approximately 90 seconds in the clinic setting [36]. The LFI should not replace asking patients about symptoms. Instead, it efficiently serves dual purposes as a functional assessment tool with prognostic ability and a symptom screening tool to trigger further evaluation in high risk patients.

In addition, studies in other populations suggest that the relationship between frailty and symptom burden may be bidirectional [13,14, 37–40]. While no data currently exists, symptom management theoretically may improve functional status, whereas rehabilitating frail patients may potentially reduce symptoms. As next steps, we plan to test a system of referring patients to outpatient palliative care based on frailty status and evaluate the role of palliative care in addressing symptoms and frailty.

We acknowledge several limitations of our study. The generalizability of findings from this single center study is unknown. Patients who were ineligible for transplant or delisted were not included and may have had even higher symptom burden. These patients should also be referred to palliative care.

In conclusion, our study is the first to demonstrate a strong association between frailty and symptom burden in patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation. Frailty should be considered an indicator for detailed symptom assessment and consideration of palliative care referral. Our findings are a promising step towards identifying patients with cirrhosis who are most likely to benefit from palliative care co-management to address symptoms and improve quality of life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grants and Financial Support: This study was supported by NIH K23AG048337 (Lai), NIH R01AG059183 (Lai), and Stupski Foundation Extending the Service of Hope grant (Pantilat). These funding agencies played no role in the analysis of the data or the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Nardelli S, Pentassuglio I, Pasquale C, Ridola L, Moscucci F, Merli M, et al. Depression, anxiety and alexithymia symptoms are major determinants of health related quality of life (HRQoL) in cirrhotic patients. Metab Brain Dis 2013;28:239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi G, Marchesini G, Nicolino F, Graziani R, Sgarbi D, Loguercio C, et al. Psychological status and depression in patients with liver cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis 2005;37:593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth K, Lynn J, Zhong Z, Borum M, Dawson NV. Dying with end stage liver disease with cirrhosis: insights from SUPPORT. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:S122–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Amodio P, Salerno F, Merli M, Panella C, et al. Factors associated with poor health-related quality of life of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2001;120:170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann AJ, Wheeler DS, James M, Turner R, Siegel A, Navarro VJ. Benefit of early palliative care intervention in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting liver transplantation. J Pain Symptom Manag 2015;50:882–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinn S, Campbell V, Sikka K. Sooner rather than later: early hospice intervention in advanced liver disease. Gastroenterol Nurs 2017;15:S18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poonja Z, Brisebois A, van Zanten SV, Tandon P, Meeberg G, Karvellas CJ. Patients with cirrhosis and denied liver transplants rarely receive adequate palliative care or appropriate management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:692–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kathpalia P, Smith A, Lai JC. Underutilization of palliative care services in the liver transplant population. World J Transplant 2016;6:594–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinclair M, Poltavskiy E, Dodge JL, Lai JC. Frailty is independently associated with increased hospitalisation days in patients on the liver transplant waitlist. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:899–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai JC, Feng S, Terrault NA, Lizaola B, Hayssen H, Covinsky K. Frailty predicts waitlist mortality in liver transplant candidates. Am J Transplant 2014;14:1870–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jha SR, Hannu MK, Gore K, Chang S, Newton P, Wilhelm K, et al. Cognitive impairment improves the predictive validity of physical frailty for mortality in patients with advanced heart failure referred for heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016;35:1092–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollack LR, Goldstein NE, Gonzalez WC, Blinderman CD, Maurer MS, Lederer DJ, et al. The frailty phenotype and palliative care needs of older survivors of critical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:1168–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shega JW, Dale W, Andrew M, Paice J, Rockwood K, Weiner DK. Persistent pain and frailty: a case for homeostenosis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown PJ, Roose SP, Fieo R, Liu X, Rantanen T, Sneed JR, et al. Frailty and depression in older adults: a high-risk clinical population. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;22:1083–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai JC, Covinsky KE, Dodge JL, Boscardin WJ, Segev DL, Roberts JP, et al. Development of a novel frailty index to predict mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2017;66:564–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kardashian A, Ge J, McCulloch CE, Kappus MR, Dunn MA, Duarte-Rojo A, et al. Identifying an Optimal Liver Frailty Index Cutoff to Predict Waitlist Mortality in Liver Transplant Candidates. Hepatology 2020. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palliative Care Quality Network. www.pcqn.org

- 18.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 1991;7:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton symptom assessment scale. Cancer 2000;88:2164–2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui D, Bruera E. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System 25 years later: past, present, and future developments. J Pain Symptom Manag 2017;53:630–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selby D, Cascella A, Gardiner K, Do R, Moravan V, Myers J, et al. A single set of numerical cutpoints to define moderate and severe symptoms for the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manag 2010;39:241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oldenmenger WH, Pleun J, de Klerk C, van der Rijt CC. Cut points on 0–10 numeric rating scales for symptoms included in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:1083–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selby D, Chakraborty A, Myers J, Saskin R, Mazzotta P, Gill A. High scores on the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale identify patients with self-defined high symptom burden. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1309–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, Fleishman SB, Zabora J, Baker F, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients: a multicenter evaluation of the distress thermometer. Cancer 2005;103:1494–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riba MB, Donovan KA, Andersen B, Braun I, Breitbart WS, Brewer BW, et al. Distress Management, Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc 2019;17:1229–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinhauser KE, Voils CI, Clipp EC, Bosworth HB, Christakis NA, Tulsky JA. “Are you at peace?”: one item to probe spiritual concerns at the end of life. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(1):101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Bosworth HB, Mcneilly M, Christakis NA, Voils CI, et al. Measuring quality of life at the end of life: validation of the QUAL-E. Palliat Support Care 2004;2:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinhauser KE, Bosworth HB, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, Parker J, et al. Initial assessment of a new instrument to measure quality of life at the end of life. J Palliat Med 2002;5:829–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weissenborn K, Rückert N, Hecker H, Manns MP. The number connection tests A and B: interindividual variability and use for the assessment of early hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol 1998;28:646–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnes A, Woodman RJ, Kleinig P, Briffa M, To T, Wigg AJ. Early palliative care referral in patients with end stage liver disease is associated with reduced resource utilisation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumann AJ, Wheeler DS, James M, Turner R, Siegel A, Navarro VJ. Benefit of early palliative care intervention in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting liver transplantation. J Pain Symptom Manag 2015;50:882–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poonja Z, Brisebois A, van Zanten SV, Tandon P, Meeberg G, Karvellas CJ. Patients with cirrhosis and denied liver transplants rarely receive adequate palliative care or appropriate management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:692–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derck JE, Thelen AE, Cron DC, Friedman JF, Gerebics AD, Englesbe MJ, et al. Quality of life in liver transplant candidates: frailty is a better indicator than severity of liver disease. Transplantation. 2015;99:340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saab S, Ibrahim AB, Shpaner A, Younossi ZM, Lee C, Durazo F, et al. MELD fails to measure quality of life in liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl 2005;11:218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jara M, Bednarsch J, Malinowski M, Lüttgert K, Orr J, Puhl G, et al. Predictors of quality of life in patients evaluated for liver transplantation. Clin Transplant 2014;28:1331–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang CW, Lebsack A, Chau S, Lai JC. The range and reproducibility of the Liver Frailty Index. Liver Transpl 201;25:841–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stubbs B, Binnekade TT, Soundy A, Schofield P, Huijnen IP, Eggermont LH. Are older adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain less active than older adults without pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Med 2013;14:1316–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hicks GE, Simonsick EM, Harris TB, Newman AB, Weiner DK, Nevitt MA, et al. Trunk muscle composition as a predictor of reduced functional capacity in the health, aging and body composition study: the moderating role of back pain. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005;60:1420–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaz Fragoso CA, Araujo K, Leo-Summers L, Van Ness PH. Lower extremity proximal muscle function and dyspnea in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:1628–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parentoni AN, Mendonça VA, Dos KS, Sá LF, Ferreira FO, Gomes DP, et al. Gait Speed as a Predictor of Respiratory Muscle Function, Strength, and Frailty Syndrome in Community-Dwelling Elderly People. J Frailty Aging 2015;4:64–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.