Abstract

Background:

Models of personality and health suggest that personality contributes to health outcomes across adulthood. Personality traits, such as Neuroticism and Conscientiousness, have long-term predictive power for cognitive impairment in older adulthood, a critical health outcome. Less is known about whether personality measured earlier in life is also associated with cognition across adulthood prior to dementia.

Methods:

Using data from the British Cohort Study 1970 (N=4,218; 58% female), the present research examined the relation between self-reported and mother-rated personality at age 16 and cognitive function concurrently at age 16 and cognitive function measured 30 years later at age 46, and whether these traits mediate the relation between childhood social class and midlife cognition.

Results:

Self-reported and mother-rated Conscientiousness at age 16 were each associated with every cognitive measure at age 16 and most measures at age 46. Self-reported Openness was likewise associated with better cognitive performance on all tasks at age 16 and prospectively predicted age 46 performance (mothers did not rate Openness). Mother-rated Agreeableness, but not self-reported, was associated with better cognitive performance at both time points. Adolescent personality mediated the relation between childhood social class and midlife cognitive function.

Conclusions:

The present study advances personality and cognition by showing that (1) adolescent personality predicts midlife cognition 30 years later, (2) both self-reports and mother-ratings are important sources of information on personality associated with midlife cognition, and (3) adolescent personality may be one pathway through which the early life socioeconomic environment is associated with midlife cognition.

Keywords: Adolescent personality, midlife cognition, observer ratings, lifespan, longitudinal

Five Factor Model (FFM) personality traits are associated with critical cognitive aging outcomes (Segerstrom, 2020). A recent meta-analysis (Aschwanden et al., 2020), for example, documented consistent associations in the published literature between personality and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD): Individuals higher in Neuroticism (the tendency to be moody, anxious, and sensitive to stress) tend to be at greater risk of ADRD in older adulthood, whereas individuals higher in Conscientiousness (the tendency to be organized, responsible, and disciplined) tend to be protected from it. Higher Extraversion (the tendency to be sociable and outgoing), Openness (the tendency to be creative and unconventional), and Agreeableness (the tendency to be trusting and straightforward) also confer some protection, but the associations are not as robust as for Neuroticism and Conscientiousness (Aschwanden et al., 2020). In addition to these critical cognitive aging outcomes, a growing body of work indicates that personality is associated with performance on tasks that measure specific cognitive functions (Curtis, Windsor, & Soubelet, 2015; Sutin, Stephan, Luchetti, & Terracciano, 2019). Much of this work has either been cross-sectional (Chapman et al., 2017; Soubelet & Salthouse, 2011) or focused on cognitive change in older adulthood (Wettstein, Tauber, Kuźma, & Wahl, 2017) or risk of ADRD (Chapman et al., 2020). The present research examines whether personality in adolescence predicts cognitive function in middle adulthood, an overlooked portion of the lifespan that may be key for cognitive outcomes in older adulthood (Livingston et al., 2017).

Personality and Cognition

Starting at least as early as adolescence, FFM traits are associated with cognitive performance. Openness, in particular, tends to be associated with better performance on tasks that measure verbal function. Adolescents higher in Openness, for example, perform better on the verbal section of the SATs (Noftle & Robins, 2007) and standardized tests of verbal ability (DeYoung, Quilty, Peterson, & Gray, 2014). Adolescents higher in Openness and Conscientiousness tend to score higher in general measures of cognition, whereas adolescents who are higher in Neuroticism tend to score worse on such measures (Dumfart & Neubauer, 2016). Among college students, higher Openness, Conscientiousness, and Agreeableness and lower Neuroticism have been associated with better performance on tasks that measure verbal, quantitative, and fluid cognitive abilities (Rikoon et al., 2016). The association between Extraversion and cognition in adolescence is more mixed and tends to be associated with worse performance on measures of verbal ability (Uttl et al., 2013).

FFM traits are also associated with cognitive function throughout adulthood. Individuals lower in Neuroticism or higher in Conscientiousness, for example, tend to have better episodic memory (Luchetti, Terracciano, Stephan, & Sutin, 2016). These two traits have also been implicated in better verbal fluency, as have higher Extraversion and Openness (Sutin et al., 2019). That is, lower Neuroticism and higher Extraversion, Openness, and Conscientiousness are associated with greater ability to produce words in a short period of time. These traits are associated with faster processing speed (Sutin et al., 2019), and Neuroticism and Conscientiousness are further associated with related aspects of executive function (Chapman et al., 2017). Higher Openness has also been associated with adaptive physiological responsivity both during a challenging numerical task (Ó Súilleabháin, Howard, & Hughes, 2018a), and across changes in demanding cognitive tasks including both verbal and numerical components (O’Súilleabháin, Howard, & Hughes, 2018b).

Longitudinal work on the relation between personality and cognition has been relatively sparce and focused on either personality as a predictor of severe cognitive impairment (Terracciano, Stephan, Luchetti, Albanese, & Sutin, 2017) or changes in specific cognitive functions over time in adulthood (Caselli et al., 2016; Wettstein et al., 2017). Some work on personality and cognitive development in childhood suggests that aspects of temperament (a precursor to personality) measured at age two are associated with cognition measured in early elementary school (Chong et al., 2019). Less work has addressed the predictive power of personality measured earlier in life for cognitive performance in adulthood. One notable exception is Chapman and colleagues (Chapman et al., 2020) who examined adolescent personality traits as predictors of Alzheimer’s disease in older adulthood. Chapman and colleagues found that traits related to higher Neuroticism and lower Conscientiousness were associated with greater dementia risk five decades later. Such research is groundbreaking, in that it links adolescent personality to a meaningful cognitive outcome in older adulthood. An important next step is to examine cognitive outcomes earlier in adulthood before dementia onset to more fully map the association between personality and cognition across adulthood.

Self-reported and Observer-rated Personality

Personality traits are typically measured with self-report – individuals describe themselves on a number of dimensions. These ratings have a long history of reliability and validity (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Close others can also be an important source that adds additional information about an individual’s personality. Observer ratings of personality are typically associated with self-reports but also have unique predictive power. Friends’ ratings of personality, for example, predict greater longevity, over and above the individual’s own self-reports of their personality (Jackson, Connolly, Garrison, Leveille, & Connolly, 2015). Observer ratings of children likewise have predictive power over decades: Children rated higher in Conscientiousness by their teachers at age 10 have better objective cardiometabolic health at age 50 (Hampson, Edmonds, Goldberg, Dubanoski, & Hillier, 2013). Observer ratings may be particularly important in adolescence where self and parent ratings may diverge, and parents may have greater perspective to make judgements about personality. Such perspective may be more strongly related to long-term outcomes, like cognition in middle adulthood, because parents may be more likely to rate the more stable aspects of the adolescent’s personality.

Personality as a Mechanism

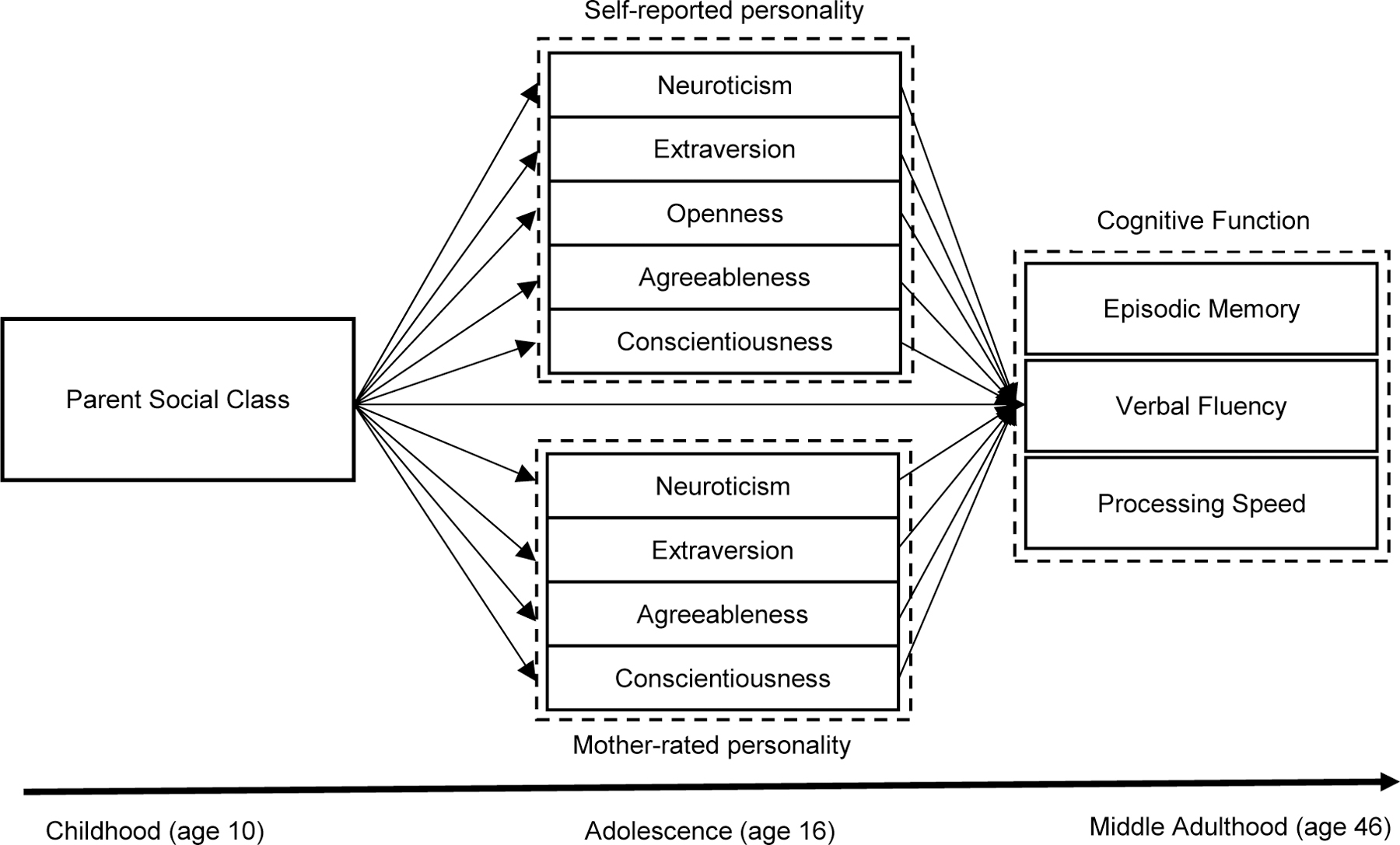

The early life socioeconomic environment is predictive of cognitive outcomes across adulthood (Luo & Waite, 2005). There is growing evidence that early life social conditions contribute to individual differences in personality (Sutin, Luchetti, Stephan, Robins, & Terracciano, 2017). That is, individuals who grew up with more economic resources during childhood tend to be more emotionally stable, open, and conscientious in adulthood (Ayoub, Gosling, Potter, Shanahan, & Roberts, 2018). Such associations are found among children who were adopted, which suggests an environmental route as well as a biological one (Sutin et al., 2017). We propose that the socioeconomic environment earlier in childhood shapes the development of personality traits that are expressed in adolescence, and these traits go on to shape cognitive functioning in middle adulthood (Figure 1). This model specifies a temporal ordering and an underlying hypothetical causal model that childhood SES contributes to adolescent personality, which contributes to cognitive function in adulthood.

Figure 1.

Mediational figure showing the mechanistic pathway between childhood social class and midlife cognition through adolescent personality.

Present Study

The present study uses data from the 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70) to address whether adolescent personality is associated with cognitive function measured 30 years later. We examine both self-reported and mother-rated personality traits at age 16 and measures of cognitive function at age 16 and age 46. Based on the personality-cognition literature, we expect lower Neuroticism and higher Conscientiousness at age 16 will be associated with better cognitive performance at age 46. In addition, given the association between Extraversion and higher verbal fluency (Sutin et al., 2019) and processing speed (Wettstein et al., 2017), we expect Extraversion to be associated with better fluency and speed, but not memory. Likewise, we expect Openness to be associated with better memory and verbal fluency. Finally, we test adolescent personality as one mechanism through which childhood SES is associated with midlife cognition (Figure 1).

Method

Participants and Procedure

The BCS70 is a cohort study of individuals who were born in the same week in 1970 in England, Scotland and Wales (Elliott & Shepherd, 2006). There have been nine follow-up assessments, with the most recent completed follow-up at age 46 in 2016. These analyses focus on the age 16 and 46 assessments because self-reported and mother-rated personality traits were available at age 16 and standard cognitive tasks were administered at age 16 and age 46. To be included in the analytic sample, BCS70 participants had to have both self-reported and mother-rated personality in adolescence and cognition measured at either age 16 or 46 and the relevant covariates (sex and family social class). A total of 4,218 participants met these requirements. At age 16, the analytic sample size ranged from 1,937 (reading) to 4,142 (vocabulary) based on available data. At age 46, the sample size ranged from 2,809 (speed) to 2,872 (fluency) based on available data. Participants in the age 16 analyses but who did not have follow-up data at age 46 (n=1,334) were more likely to be male (χ2=11.16, p<.01), from a lower social class (d=.19, p<.01), scored lower in self-reported Agreeableness (d=.09, p<.01) and Conscientiousness (d=.07, p<.05), scored higher in mother-rated Neuroticism (d=.09, p<.01) and lower in mother-rated Extraversion (d=.12, p<.01), mother-rated Agreeableness (d=.14, p<.01), and mother-rated Conscientiousness (d=.09, p<.01); there were no differences in self-reported Neuroticism (d=.00, ns), Extraversion (d=.03, ns), or Openness (d=.02, ns).

Measures

Age 16 mother-rated personality.

Mothers rated two sets of items related to their child’s personality. These items have been previously selected and validated as a measure of four of the five personality traits (Prevoo & ter Weel, 2015). Neuroticism was assessed with six items (e.g., changes mood quickly), Extraversion was assessed with five items (e.g., solitary; reverse scored), Agreeableness was assessed with seven items (e.g., interferes with others; reverse scored), and Conscientiousness was assessed with four items (e.g., fails to finish things; reverse scored). All items were standardized individually prior to taking the mean because the two sets were rated on different response scales. For each trait, the mean was taken in the direction of the trait label (i.e., higher scores on Neuroticism indicated higher Neuroticism). Openness was not represented among the mother-rated items (Prevoo & ter Weel, 2015).

Age 16 self-reported personality.

In the Knowing Myself section of the Student Test Booklet, adolescents rated 27 items on a scale from 1 (applied very much) to 3 (doesn’t apply). All items started with the stem, “I am …” Five experts in personality assigned each item to its appropriate FFM trait. Items were first retained if at least half of the personality experts assigned the specific item to the same trait. This approach led to three items for Neuroticism: angry, nervous, lonely; three items for Extraversion: quiet (reverse scored), shy (reverse scored), popular; three items for Openness: clever, keen on many different things, independent; four items for Agreeableness: friendly, helpful, violent (reverse scored), a loving person; and seven for Conscientiousness: lazy (reverse scored), grown up for my age, punctual, a responsible person, obedient, good at exams, reliable. Preliminary analyses indicated that one item for Agreeableness (I am violent) and one item for Conscientiousness (I am grown up for my age) did not fit with their respective domains and were dropped from the trait measure. All items were scored in the direction of the trait label and the mean taken across items. In an independent sample of adolescents (N=553), each of the traits constructed from the items correlated moderately with its counterpart measured with a standard FFM personality scale (the Big Five Inventory-2): rNeuroticism=.49, rExtraversion=.52, rOpenness=.38, rAgreeableness=.49, and rConscientiousness=.55.

Age 16 cognition.

Participants completed five cognitive tests at the age 16 assessment: Reading, spelling, vocabulary, math, and matrix reasoning (see Parsons, 2014 for detailed information about each test). Reading was measured with a short version of the Edinburgh Reading Test that included skimming, vocabulary, reading for facts, points of view, and comprehension. Spelling was measured with 100 words that the participant had to indicate whether or not each word was spelled correctly. Vocabulary was measured with a 75-item synonym test in which participants had to choose the correct synonym for each word from five choices. Math was measured with a 60-item test that measured arithmetic, probabilities, and area with multiple choice items. The matrix reasoning test presented geometric figures with one missing box. Participants had to evaluate the relation between the figures shown and pick the figure that completed the matrix from five possible options. For each test, the score was the sum of correct responses. In addition to the individual cognitive tasks, we extracted a general cognitive factor through factor analysis.

Age 46 cognition.

Episodic memory was assessed with a word list task. Participants were given 10 words and asked to recall those words immediately and after a short delay. The sum across immediate and delayed recall was taken as the memory score. Verbal fluency was measured with a standard animal naming task where participants named as many animals as they could in 60 seconds. The score was the total number of animals named. Processing speed was measured with a letter cancellation task. Participants were given a matrix of letters and were asked to scan through each line and cross out all the Ps and Ws as quickly as possible. The numbers of letter scanned in the allotted time was the measure of processing speed. In addition to the individual cognitive tasks, we extracted a general cognitive factor through factor analysis.

Covariates.

Covariates included participant sex and childhood family social class. Sex was coded as 0=male and 1=female. Childhood family social class was scored from 1 (unskilled) to 6 (professional) by the BCS70 and is a well-validated measure used to evaluate health disparities in adulthood (Bann, Johnson, Li, Kuh, & Hardy, 2017). Social class at age 10 was based on the father’s occupation or the mother’s occupation if the father’s occupation was missing. Approximately 7% of the sample (n=542) were missing this information at age 10 but had it at age 16. For these participants, age 16 family social class was used instead. We included an additional dummy-coded variable as a covariate to indicate age of the social class assessment (i.e., at either age 10 or age 16). In supplemental analyses, we also controlled for participant educational attainment.

Statistical Approach

Linear regression was used to test the association between personality and cognitive performance at both age 16 and age 46, controlling for sex and age 10 social class. Each trait was entered separately. For each set of analyses, self-reported and mother-rated personality were entered individually and then together to determine whether there were unique associations from each source of information on personality. We performed a number of supplemental analyses. First, we re-ran the age 16 analyses excluding participants without age 46 cognition. Second, we re-ran the age 46 analyses with participants’ educational attainment as an additional covariate. Third, we tested whether the associations varied by participant sex by adding an interaction term between each trait and participant sex to the regression analysis.

We used the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018) to test the hypothesized mediational model (Figure 1). To evaluate mediation, there should be an association between the predictor (childhood social class) and the proposed mediators (personality traits; path a), an association between the mediators and the outcome (cognition at age 46; path b), and an association between the predictor and the outcome (path c). Mediation occurs when paths a and b are significant and there is a significant reduction in the association between the predictor and the outcome (path c’). We specified a multiple mediator model in which self-reported and mother-rated personality traits were tested as simultaneous mediators of the relation between childhood social class and age 46 cognition. Across all analyses, there was no correction for multiple comparisons, and we report the p-value to three decimal places to allow readers to make their own judgements.

Results

Descriptive statistics for all study variables are shown in Table 1 and bivariate correlations are in Supplemental Table S1. Table 2 shows the associations between age 16 personality traits and age 16 cognition. Consistent with the literature on personality and cognition in adolescence, the strongest association between self-reported personality and cognitive performance was for Openness: Participants higher in Openness performed better on all cognitive tests. Following Openness, Conscientiousness was also associated with better performance. There was modest support for an association between self-reported Neuroticism and Extraversion and concurrent cognitive performance: Neuroticism was associated with worse performance on the tasks that measured spelling and math, and Extraversion was associated with worse performance on vocabulary and spelling. Self-reported Agreeableness was unrelated to cognition. A slightly different pattern emerged for mother-rated personality. Mother ratings of adolescent Conscientiousness were the most strongly associated with the cognitive tasks, compared to the other traits. Mother-rated Neuroticism and Agreeableness had negative and positive associations, respectively, with cognitive performance. Mother-rated Extraversion was associated with better reading and math but was unrelated to other cognitive tasks. Mothers did not rate Openness.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for all Study Variables

| Variable | Mean (SD) or % (n) |

|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 58.3% (2457) |

| Social class | 3.76 (1.29) |

| Self-reported personality | |

| Neuroticism | 1.56 (.43) |

| Extraversion | 2.20 (.47) |

| Openness | 2.23 (.38) |

| Agreeableness | 2.43 (.38) |

| Conscientiousness | 2.32 (.34) |

| Mother-rated personality | |

| Neuroticism | −.02 (.72) |

| Extraversion | −.02 (.63) |

| Agreeableness | .05 (.61) |

| Conscientiousness | .05 (.76) |

| Age 16 Cognition | |

| Vocabulary (n=4,142) | 44.42 (12.04) |

| Reading (n=1,937) | 56.27 (12.45) |

| Spelling (n=4,112) | 166.00 (22.33) |

| Math (n=2,349) | 38.17 (11.26) |

| Matrices (n=1,989) | 9.01 (1.53) |

| Age 46 Cognition | |

| Memory (n=2,871) | 12.59 (2.92) |

| Fluency (n=2,872) | 24.39 (6.12) |

| Speed (n=2,809) | 352.52 (82.56) |

Note. N=4,218. Social class ranged from 1 (unskilled) to 6 (professional). Personality self-reports were rated on a scale from 1 to 3. Mother-rated personality was the mean of standardized items.

Table 2.

Self-reported and Mother-rated Personality and Cognition at Age 16

| Trait | Self |

Mother |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | |

| Vocabulary | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.02 | .133 | −.12 | .000 |

| Extraversion | −.06 | .000 | .01 | .419 |

| Openness | .17 | .000 | -- | -- |

| Agreeableness | −.02 | .245 | .13 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .12 | .000 | .21 | .000 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Neuroticism | .00 | .766 | −.11 | .000 |

| Extraversion | −.06 | .000 | .02 | .115 |

| Agreeableness | −.02 | .221 | .13 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .08 | .000 | .20 | .000 |

| N | 4142 | |||

| Reading | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.03 | .117 | −.13 | .000 |

| Extraversion | .00 | .982 | .08 | .000 |

| Openness | .23 | .000 | -- | -- |

| Agreeableness | −.02 | .380 | .20 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .19 | .000 | .23 | .000 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.01 | .528 | −.12 | .000 |

| Extraversion | −.02 | .445 | .08 | .000 |

| Agreeableness | −.02 | .359 | .20 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .15 | .000 | .21 | .000 |

| N | 1937 | |||

| Spelling | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.03 | .044 | −.09 | .000 |

| Extraversion | −.05 | .001 | .02 | .177 |

| Openness | .12 | .000 | -- | -- |

| Agreeableness | .01 | .634 | .14 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .14 | .000 | .19 | .000 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.02 | .271 | −.09 | .000 |

| Extraversion | −.06 | .000 | .03 | .039 |

| Agreeableness | .01 | .688 | .14 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .11 | .000 | .17 | .000 |

| N | 4112 | |||

| Math | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.05 | .011 | −.12 | .000 |

| Extraversion | −.02 | .419 | .10 | .000 |

| Openness | .20 | .000 | -- | -- |

| Agreeableness | −.04 | .055 | .17 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .19 | .000 | .27 | .000 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.03 | .090 | −.12 | .000 |

| Extraversion | −.04 | .071 | .10 | .000 |

| Agreeableness | −.04 | .056 | .17 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .15 | .000 | .24 | .000 |

| N | 2349 | |||

| Matrices | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | .00 | .813 | −.05 | .015 |

| Extraversion | .00 | .932 | .04 | .053 |

| Openness | .14 | .000 | -- | -- |

| Agreeableness | −.03 | .243 | .09 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .09 | .000 | .15 | .000 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Neuroticism | .01 | .535 | −.06 | .012 |

| Extraversion | −.01 | .621 | .04 | .046 |

| Agreeableness | −.03 | .241 | .09 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .06 | .004 | .14 | .000 |

| N | 1989 | |||

| Overall Cognition | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.01 | .801 | −.11 | .000 |

| Extraversion | −.04 | .076 | .07 | .002 |

| Openness | .25 | .000 | -- | -- |

| Agreeableness | .00 | .865 | .19 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .21 | .000 | .28 | .000 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Neuroticism | .01 | .531 | −.12 | .000 |

| Extraversion | −.06 | .010 | .08 | .000 |

| Agreeableness | .00 | .852 | .19 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .17 | .000 | .24 | .000 |

| N | 1831 | |||

Note. Coefficients are standardized beta coefficients from linear regression controlling for sex and social class. Model 1 tested self-reported and mother-rated personality separately. Model 2 tested self-reported and mother-rated personality simultaneously. Across all analyses, traits were entered in separately.

Model 2 tested whether there were associations from each source of information on personality when entered simultaneously. Interestingly, self-report and mother ratings of Conscientiousness were both associated with better cognitive performance, whereas mother-rated Neuroticism and Agreeableness, but not the self-reports of these traits, were associated with worse and better performance, respectively (see Table 2, Model 2). Finally, the associations went in opposite directions for Extraversion: Participants who saw themselves as extraverted performed worse on the cognitive tasks, whereas participants whose mothers viewed them as extraverted performed better. The pattern of association was virtually identical when the sample excluded participants without age 46 cognition (Supplemental Table S2). In addition, the moderation analysis indicated that self-reported Agreeableness was associated with better vocabulary (βAgreeableness*sex=.06, p=.011), reading (βAgreeableness*sex=.08, p=.009) and math (βAgreeableness*sex=.07, p=.025) for females, whereas this trait was unrelated to these cognitive measures for males. In addition, the association between mother-rated Conscientiousness and both spelling (βConscientiousness*sex=−.06, p=.004) and matrices (βConscientiousness*sex=−.07, p=.017) was stronger among males than females. None of the other interactions was significant.

The associations between age 16 personality and age 46 cognition are shown in Table 3. Among the self-reported traits, Openness again had the strongest association with cognition: Participants who saw themselves as open at age 16 performed better on memory, fluency, and speed measured 30 years later. Higher self-reported Conscientiousness was likewise associated with better performance on these tasks, and self-reported Extraversion was associated with better fluency and speed. Neither self-reported adolescent Neuroticism nor Agreeableness was associated with midlife cognition. Similar to the age 16 associations, mother-rated Conscientiousness was associated with better performance on nearly all of the tasks. Further, higher mother-rated Extraversion and Agreeableness were both associated with better performance on the memory and fluency tasks and lower mother-rated Neuroticism was associated with better performance on the memory task. This pattern of association was similar when the self-reports and mother-ratings were entered simultaneously in the analysis, which indicated that both reporters provided information about the adolescent with the power to predict cognitive performance 30 years later (Table 3, Model 2). The pattern of association was similar when participant educational attainment was added as an additional covariate (Supplemental Table S3). The two exceptions were the associations between self-reported Conscientiousness and memory and verbal fluency, which were reduced to non-significance (the association with speed and mean cognition remained) and the associations between mother-rated Neuroticism and memory and mean cognitive function were reduced to non-significance. Notably, all associations between self-reported Openness and age 46 cognition were still significant, as was the association between mother-rated Conscientiousness and age 46 cognition. This pattern indicates that educational attainment did not account for all of the relation between Openness and Conscientiousness and midlife cognition. Finally, the moderation analysis indicated that association between self-reported Extraversion and speed was apparent for females but not males (βExtraversion*sex=.06, p=.032) and the association between mother-rated Extraversion and memory (βExtraversion*sex=−.06, p=.037) and mother-rated Conscientiousness and fluency (βConscientiousness*sex=−.06, p=.044) was apparent for both sexes but somewhat stronger among males. None of the other interactions was significant.

Table 3.

Self-reported and Mother-rated Personality at age 16 and Cognition at Age 46

| Self |

Mother |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | |

| Memory | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.02 | .270 | −.05 | .003 |

| Extraversion | .02 | .250 | .07 | .000 |

| Openness | .11 | .000 | -- | -- |

| Agreeableness | .02 | .335 | .09 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .08 | .000 | .14 | .000 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.01 | .532 | −.05 | .006 |

| Extraversion | .01 | .735 | .07 | .000 |

| Agreeableness | .02 | .355 | .09 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .05 | .005 | .14 | .000 |

| N | 2871 | |||

| Fluency | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.03 | .098 | −.03 | .084 |

| Extraversion | .06 | .000 | .06 | .001 |

| Openness | .10 | .000 | -- | -- |

| Agreeableness | .02 | .403 | .08 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .06 | .000 | .10 | .000 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.03 | .165 | −.03 | .141 |

| Extraversion | .06 | .003 | .05 | .012 |

| Agreeableness | .02 | .422 | .08 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .05 | .009 | .10 | .000 |

| N | 2872 | |||

| Speed | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.02 | .259 | −.01 | .653 |

| Extraversion | .05 | .013 | .03 | .119 |

| Openness | .09 | .000 | -- | -- |

| Agreeableness | .00 | .887 | .02 | .256 |

| Conscientiousness | .06 | .003 | .04 | .057 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.02 | .285 | .00 | .792 |

| Extraversion | .04 | .026 | .02 | .283 |

| Agreeableness | .00 | .897 | .02 | .257 |

| Conscientiousness | .05 | .007 | .03 | .159 |

| N | 2809 | |||

| Overall Cognition | ||||

| Model 1 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.04 | .056 | −.05 | .013 |

| Extraversion | .06 | .000 | .08 | .000 |

| Openness | .15 | .000 | -- | -- |

| Agreeableness | .02 | .206 | .10 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .10 | .000 | .14 | .000 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.03 | .129 | −.04 | .029 |

| Extraversion | .05 | .008 | .07 | .000 |

| Agreeableness | .02 | .226 | .10 | .000 |

| Conscientiousness | .08 | .000 | .13 | .000 |

| N | 2817 | |||

Note. Coefficients are standardized beta coefficients from linear regression controlling for sex and social class. Model 1 tested self-reported and mother-rated personality separately. Model 2 tested self-reported and mother-rated personality simultaneously. Across all analyses, traits were entered in separately.

Finally, we tested personality as a mediator between childhood social class and cognitive function in middle age (Table 4). Participants whose parents (primarily fathers) were in a higher-class occupation were more open and less agreeable based on self-reports and less neurotic and more extraverted, agreeable, and conscientious based on mother reports. Openness was the strongest and most consistent mediator across the cognitive outcomes: Participants from higher SES families had better cognitive function in middle age in part through higher Openness. Mother-rated Conscientiousness and (lower) Neuroticism likewise mediated the association between childhood social class and the cognitive measures, except speed. Mother-rated Agreeableness mediated the association with verbal fluency and the overall cognition measure.

Table 4.

Indirect Effects of Childhood Social Class on Midlife Cognition Through Personality

| Trait | Mediation Parameter | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| SES to Personality (path a) | Personality to Cognition (path b) | Indirect Effect (axb) | Total Effect (path c) | Direct Effect (path c’) | ||||

|

|

||||||||

| b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

|

|

||||||||

| Memory | .38 (.04) | .31 (.04) | ||||||

| Neuroticism (S) | .00 (.01) | .556 | .08 (.14) | .549 | .00 (.00) | .787 | p=.000 | p=.000 |

| Extraversion (S) | .00 (.01) | .767 | .13 (.13) | .301 | .00 (.00) | .835 | ||

| Openness (S) | .04 (.01) | .000 | .73 (.16) | .000 | .03 (.01) | .000 | ||

| Agreeableness (S) | −.02 (.01) | .001 | −.24 (.16) | .128 | .00 (.00) | .183 | ||

| Conscientiousness (S) | .00 (.01) | .978 | .30 (.19) | .103 | .00 (.00) | .955 | ||

| Neuroticism (M) | −.06 (.01) | .000 | .21 (.10) | .030 | −.01 (.01) | .047 | ||

| Extraversion (M) | .03 (.01) | .005 | .22 (.10) | .025 | .01 (.00) | .091 | ||

| Agreeableness (M) | .04 (.01) | .000 | .22 (.11) | .051 | .01 (.01) | .080 | ||

| Conscientiousness (M) | .05 (.01) | .000 | .50 (.08) | .000 | .02 (.01) | .000 | ||

| Verbal Fluency | .79 (.09) | .68 (.09) | ||||||

| Neuroticism (S) | .00 (.01) | .549 | .14 (.29) | .623 | .00 (.00) | .816 | p=.000 | p=.000 |

| Extraversion (S) | .00 (.01) | .784 | .91 (.27) | .009 | .00 (.01) | .794 | ||

| Openness (S) | .04 (.01) | .000 | 1.34 (.32) | .000 | .06 (.02) | .000 | ||

| Agreeableness (S) | −.02 (.01) | .001 | −.65 (.34) | .057 | .01 (.01) | .107 | ||

| Conscientiousness (S) | .00 (.01) | .946 | .68 (.39) | .082 | .00 (.00) | .954 | ||

| Neuroticism (M) | −.06 (.01) | .000 | .50 (.21) | .015 | −.03 (.01) | .027 | ||

| Extraversion (M) | .03 (.01) | .004 | .33 (.21) | .115 | .01 (.01) | .186 | ||

| Agreeableness (M) | .04 (.01) | .000 | .62 (.34) | .010 | .02 (.01) | .029 | ||

| Conscientiousness (M) | .05 (.01) | .000 | .77 (.18) | .000 | .04 (.01) | .002 | ||

| Speed | 4.01 (1.21) | 3.06 (1.24) | ||||||

| Neuroticism (S) | .00 (.01) | .548 | 1.07 (4.02) | .789 | .00 (.03) | .893 | p=.001 | p=.013 |

| Extraversion (S) | .00 (.01) | .890 | 8.41 (3.76) | .026 | −.01 (.06) | .900 | ||

| Openness (S) | .04 (.01) | .000 | 15.39 (4.57) | .001 | .65 (.21) | .002 | ||

| Agreeableness (S) | −.02 (.01) | .002 | −10.34 (4.70) | .028 | .17 (.10) | .087 | ||

| Conscientiousness (S) | .00 (.01) | .726 | 11.80 (5.48) | .031 | .02 (.06) | .753 | ||

| Neuroticism (M) | −.06 (.01) | .000 | 3.19(2.86) | .264 | −.18 (.17) | .281 | ||

| Extraversion (M) | .03 (.01) | .005 | 2.66 (2.92) | .363 | .07 (.08) | .413 | ||

| Agreeableness (M) | .04 (.01) | .000 | 1.95 (3.32) | .556 | .07 (.13) | .569 | ||

| Conscientiousness (M) | .05 (.01) | .000 | 3.17 (2.44) | .195 | .16 (.13) | .220 | ||

| Overall Cognition | .16 (.01) | .13 (.01) | ||||||

| Neuroticism (S) | .00 (.01) | .494 | .03 (.04) | .519 | .00 (.00) | .748 | p=.000 | p=.000 |

| Extraversion (S) | .00 (.01) | .906 | .14 (.04) | .002 | .00 (.00) | .910 | ||

| Openness (S) | .04 (.01) | .000 | .32 (.05) | .000 | .01 (.00 | .000 | ||

| Agreeableness (S) | −.02 (.01) | .002 | −.14 (.05) | .010 | .00 (.00) | .055 | ||

| Conscientiousness (S) | .00 (.01) | .795 | .18 (.06) | .006 | .00 (.00) | .808 | ||

| Neuroticism (M) | −.06 (.01) | .000 | .10 (.03) | .002 | −.006 (.002) | .007 | ||

| Extraversion (M) | .03 (.01) | .004 | .09 (.03) | .009 | .002 (.001) | .061 | ||

| Agreeableness (M) | .04 (.01) | .000 | .11 (.04) | .005 | .004 (.002) | .019 | ||

| Conscientiousness (M) | .05 (.01) | .000 | .16 (.04) | .000 | .008 (.002) | .000 | ||

Note. N=2,871 for Memory, 2,872 for Fluency, 2,809 for Speed, 2817 for overall cognition. (S) indicates self-reports of personality. (M) indicated mother ratings of personality. Coefficients are unstandardized coefficients from the mediation analysis controlling for sex and social class. Numbers in parentheses are standard errors.

Discussion

The present study examined the association between personality traits at age 16 – reported both by the self and rated by their mother – and cognitive function concurrently and measured 30 years later in middle age. Concurrently and over 30 years, self-reported Openness had the strongest associations with the cognitive outcomes. In addition, self-reported and mother-rated Conscientiousness both had associations with nearly every cognitive outcome in adolescence and adulthood. Self-reported Openness further mediated the relation between childhood SES and each cognitive outcome in middle age, and Conscientiousness also mediated this association for memory and fluency. The present research indicates that personality traits have long-term predictive power for cognitive function and serve as one mechanism through which childhood SES contributes to cognitive health in middle adulthood.

Models of personality and health specify that personality traits are associated with long-term health outcomes. These associations are typically studied in the context of longevity, where personality measured as early as age 11 has been found to predict how long someone will live (Friedman et al., 1993). In the context of cognition, adolescent personality has long-term predictive power for risk of dementia over 50 years (Chapman et al., 2020). The present research adds to this literature by showing that both self-reported and mother-rated adolescent personality is associated with cognitive function in middle age, a critical period for cognitive aging (Livingston et al., 2017).

Of the self-reported traits, Openness had the most pervasive associations with cognitive performance both in adolescence and middle age. Children higher in Openness are better readers and writers, as reported by both their parents and teachers (Lamb, Chuang, Wessels, Broberg, & Hwang, 2002). Adolescents higher in Openness score higher on the verbal section of the SATs (Noftle & Robins, 2007). And, in adulthood, Openness is associated with better verbal reasoning (Rammstedt, Danner, & Martin, 2016; Sutin et al., 2021) and verbal fluency (Sutin et al., 2019). Across adulthood, these verbal skills may be supported by how individuals higher in Openness spend their time. In daily life, for example, individuals higher in Openness spend more time reading and less time watching TV (Rohrer & Lucas, 2018) and engage in reading and writing activities (Stephan, Boiché, Canada, & Terracciano, 2014). As such, it was expected that Openness would be associated with better verbal ability. The associations extended to all aspects of cognitive function that were measured in adolescence and middle adulthood.

Conscientiousness was also associated consistently with better performance on the cognitive tasks. Higher Conscientiousness tends to be associated with working harder (Trautwein, Lüdtke, Roberts, Schnyder, & Niggli, 2009) and performing better in school (Richardson & Abraham, 2009). Previous research has suggested, however, that the association between Conscientiousness and cognitive performance is not consistent in adolescence (Trautwein et al., 2009). It was thus somewhat surprising that Conscientiousness was associated with better cognitive performance in adolescence. In adulthood, the association between Conscientiousness and better cognition function is more consistent (Sutin et al., 2019; Sutin, Stephan, & Terracciano, 2018), perhaps due to the healthier behavioral patterns associated with this trait that preserve cognitive function (e.g., physical activity, better sleep). Interestingly, self-reported and mother-rated Conscientiousness both had associations with better cognitive function in adolescence and in midlife. Further, the effect of mother-reported Conscientiousness tended to be larger in magnitude than the self-reports. This pattern suggests that mothers may detect characteristics of their children that children do not see in themselves, and these characteristics are important predictors of midlife cognition.

The associations were less consistent for the other three traits. In contrast to the literature on Neuroticism and worse cognitive function in adulthood (Chapman et al., 2017; Curtis et al., 2015; Sutin et al., 2019), adolescent Neuroticism was generally unrelated to cognitive function in midlife. It was, however, associated with worse performance in adolescence. Developmentally, Neuroticism peaks in adolescence (Soto, John, Gosling, & Potter, 2011). The negative association may reflect the stress of adolescence that does not have lasting effects as does Neuroticism is adulthood, which may have more longstanding processes associated with worse health. Consistent with the literature (Sutin et al., 2019), both self-reported and mother-rated adolescent Extraversion were associated with better verbal fluency in middle adulthood. This finding extends cross-sectional work on fluency and indicates the long-term predictive power of Extraversion. Extraversion was also associated with better performance on the processing speed task at age 46, which may reflect the vigor that is characteristic of this trait (Armon & Shirom, 2011) and useful for performance on tasks that require speed. Finally, although Agreeableness is not associated consistently with cognitive function (Chapman et al., 2017; Sutin et al., 2019), mother-rated Agreeableness was associated with better performance in both adolescence and middle adulthood. Perhaps aspects of this trait that are perceived by others more than the self has stronger relations with cognitive performance than those perceived by the self.

The present research also tested a model that hypothesized adolescent personality traits as one mechanism that accounts for the association between childhood social class and midlife cognition. Children who grow up with fewer economic resources tend to have lower cognitive function in adulthood (Luo & Waite, 2005). The mediation analysis suggested that Openness and Conscientiousness are personality mechanisms that link childhood social class to cognition in middle adulthood. Families with more financial and educational resources may provide an early life environment that helps develop higher Openness, including exposing children to more and varied experiences and providing more books and other opportunities for learning (Larson, Russ, Nelson, Olson, & Halfon, 2015). This Openness, detected in adolescence, in turn, promotes better memory, fluency, and speed in middle age. Given that Openness also contributes to cognitive function across the lifespan (DeYoung et al., 2014; Sharp, Reynolds, Pedersen, & Gatz, 2010; Sutin et al., 2011), it may be one mechanism that supports healthier cognitive aging. Interestingly, mother-rated Conscientiousness, but not self-reported Conscientiousness also mediated the relation between social class and memory and fluency in middle age. Families with higher social class may provide a more stable environment for their children and one needed to develop habits and skills related to Conscientiousness (e.g., organization, discipline) that support healthier cognition. Our model did not, however, test the mechanisms through which adolescent personality is associated with midlife cognition. Such pathways may include educational attainment, occupational experiences, stressful life events, social connection, and health behaviors. There are likely to be complex interactions among these factors that lead to how well someone performs on a cognitive task in midlife. Further, there is both stability and change in personality from adolescence to older adulthood (Damian, Spengler, Sutu, & Roberts, 2019) that may reflect these complex interactions and contribute to cognitive performance across adulthood. Given that recent evidence indicates that personality can be changed through intervention (Roberts et al., 2017), this research suggests that personality may be one modifiable factor that could help promote healthier cognitive aging. Across social class, interventions to improve trait psychological functioning (e.g., fostering grit, openness, emotional stability) may help individuals enter middle adulthood in a better position to maintain their cognitive health in midlife and beyond.

The present study had several strengths, including self-reported and mother-rated personality in adolescence and cognitive function assessed in adolescence and again 30 years later in middle adulthood. There are some limitations to address in future research. First, participants and mothers completed different personality scales. As such, the unique associations for self-report and mother-rated personality may have been due to differences in content on the scales rather than unique associations. Second, neither scale was a standard measure of FFM traits, since at the time of data collection in 1986, there was not a standard FFM scale. Third, the mother-rated measure did not include any items related to Openness. Fourth, a personality measure was not administered at the age 46 assessment and the cognitive measures were different at the two ages, so it was not possible to examine the concurrent relation between personality and cognition in middle adulthood or bi-directional relations between personality and cognition over 30 years. It is likely that the associations between personality and midlife cognition would be stronger with a more proximal measure of personality because it would better reflect the diversity of experiences over the 30 years. Future research would benefit from the use of standardized scales measured at multiple points across the lifespan to better identify reciprocal relations between personality and cognition. Despite these limitations, this research contributes to models of personality and cognitive aging and suggests that adolescent personality, as reported by both the self and a knowledgeable informant, is associated with cognitive performance in midlife.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the BCS70 and its participants, the Centre for Longitudinal Studies, and the UK Data Service for providing the data used in this research.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01AG053297 (ARS) and R01AG068093 (AT). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- Albanese E, Launer LJ, Egger M, Prince MJ, Giannakopoulos P, Wolters FJ, & Egan K (2017). Body mass index in midlife and dementia: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 589,649 men and women followed in longitudinal studies. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 8, 165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armon G, & Shirom A (2011). The across-time associations of the five-factor model of personality with vigor and its facets using the bifactor model. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(6), 618–627. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2011.608753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschwanden D, Strickhouser JE, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Sutin AR, & Terracciano A (2020). Is personality associated with dementia risk? A meta-analytic investigation. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ayoub M, Gosling SD, Potter J, Shanahan M, & Roberts BW (2018). The relations between parental socioeconomic status, personality, and life outcomes. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(3), 338–352. doi: 10.1177/1948550617707018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bann D, Johnson W, Li L, Kuh D, & Hardy R (2017). Socioeconomic inequalities in body mass index across adulthood: Coordinated analyses of individual participant data from three british birth cohort studies initiated in 1946, 1958 and 1970. PLoS Medicine, 14(1), e1002214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli RJ, Dueck AC, Locke DE, Henslin BR, Johnson TA, Woodruff BK, … Geda YE (2016). Impact of personality on cognitive aging: A prospective cohort study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 22(7), 765–776. doi: 10.1017/S1355617716000527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Benedict RH, Lin F, Roy S, Federoff HJ, & Mapstone M (2017). Personality and performance in specific neurocognitive domains among older persons. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(8), 900–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Huang A, Peters K, Horner E, Manly J, Bennett DA, & Lapham S (2020). Association between high school personality phenotype and dementia 54 years later in results from a national US sample. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(2), 148–154. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong SY, Chittleborough CR, Gregory T, Lynch J, Mittinty M, & Smithers LG (2019). The controlled direct effect of temperament at 2–3 years on cognitive and academic outcomes at 6–7 years. PLoS One, 14(6), e0204189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT Jr., & McCrae RR (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis RG, Windsor TD, & Soubelet A (2015). The relationship between Big-5 personality traits and cognitive ability in older adults - a review. Neuropsychology Development Cognition B Aging Neuropsychology and Cognition, 22(1), 42–71. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2014.888392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damian RI, Spengler M, Sutu A, & Roberts BW (2019). Sixteen going on sixty-six: A longitudinal study of personality stability and change across 50 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(3), 674–695. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG, Quilty LC, Peterson JB, & Gray JR (2014). Openness to experience, intellect, and cognitive ability. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96(1), 46–52. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2013.806327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumfart B, & Neubauer AC (2016). Conscientiousness is the most powerful noncognitive predictor of school achievement in adolescents. Journal of Individual Differences, 37, 8–15. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001/a000182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J, & Shepherd P (2006). Cohort profile: 1970 British Birth Cohort (BCS70). International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(4), 836–843. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS, Tucker JS, Tomlinson-Keasey C, Schwartz JE, Wingard DL, & Criqui MH (1993). Does childhood personality predict longevity? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(1), 176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Edmonds GW, Goldberg LR, Dubanoski JP, & Hillier TA (2013). Childhood conscientiousness relates to objectively measured adult physical health four decades later. Health Psychology, 32(8), 925–928. doi: 10.1037/a0031655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JJ, Connolly JJ, Garrison SM, Leveille MM, & Connolly SL (2015). Your friends know how long you will live: a 75-year study of peer-rated personality traits. Psychological Science, 26(3), 335–340. doi: 10.1177/0956797614561800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Gottesman RF, Sharrett AR, Tapia AL, DavisThomas S, Windham BG, … Mosley TH Jr. (2018). Midlife vascular risk factors and midlife cognitive status in relation to prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in later life: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(11), 1406–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Chuang SS, Wessels H, Broberg AG, & Hwang CP (2002). Emergence and construct validation of the big five factors in early childhood: A longitudinal analysis of their ontogeny in Sweden. Child Development, 73, 1517–1524. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson K, Russ SA, Nelson BB, Olson LM, & Halfon N (2015). Cognitive ability at kindergarten entry and socioeconomic status. Pediatrics, 135(2), e440–448. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, … Mukadam N (2017). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Luchetti M, Terracciano A, Stephan Y, & Sutin AR (2016). Personality and cognitive decline in older adults: Data from a longitudinal sample and meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 591–601. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, & Waite LJ (2005). The impact of childhood and adult SES on physical, mental, and cognitive well-being in later life. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(2), S93–S101. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.2.S93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noftle EE, & Robins RW (2007). Personality predictors of academic outcomes: Big Five correlates of GPA and SAT Scores. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(1), 116–130. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Súilleabháin PS, Howard S, & Hughes BM (2018a). Openness to experience and stress responsivity: An examination of cardiovascular and underlying hemodynamic trajectories within an acute stress exposure. PLoS One, 13(6), e0199221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ó Súilleabháin PS, Howard S, & Hughes BM (2018b). Openness to experience and adapting to change: Cardiovascular stress habituation to change in acute stress exposure. Psychophysiology, 55(5), e13023. doi: 10.1111/psyp.13023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons S (2014). Childhood cognition in the 1970 British Cohort Study. Retrieved from Centre for Longitudinal Studies: https://cls.ucl.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/BCS70-Childhood-cognition-in-the-1970-British-Cohort-Study-Nov-2014-final.pdf

- Pedditzi E, Peters R, & Beckett N (2016). The risk of overweight/obesity in mid-life and late life for the development of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Age & Ageing, 45(1), 14–21. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevoo T, & ter Weel B (2015). The importance of early conscientiousness for socio-economic outcomes: Evidence from the British Cohort Study. Oxford Economic Papers, 67, 918–948. doi: 10.1093/oep/gpv022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt B, Danner D, & Martin S (2016). The association between personality and cognitive ability: Going beyond simple effects. Journal of Research in Personality, 62, 39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2016.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson M, & Abraham C (2009). Conscientiousness and achievement motivation predict performance. European Journal of Personality, 23(7), 589–605. doi: 10.1002/per.732 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rikoon SH, Brenneman M, Kim LE, Khorramdel L, MacCann C, Burrus J, & Roberts RD (2016). Facets of conscientiousness and their differential relationships with cognitive ability factors. Journal of Research in Personality, 61, 22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2016.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Luo J, Briley DA, Chow PI, Su R, & Hill PL (2017). A systematic review of personality trait change through intervention. Psychological Bulletin, 143(2), 117–141. doi: 10.1037/bul0000088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JM, & Lucas RE (2018). Only so many hours: Correlations between personality and daily time use in a representative German panel. Collabra: Psychology, 4(1). doi: 10.1525/collabra.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC (2020). Personality and incident Alzheimer’s disease: Theory, evidence, and future directions. Journals of Gerontology Sereis B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(3), 513–521. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby063 . doi:10.1093/geronb/gby06310.1093/geronb/gby063. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp ES, Reynolds CA, Pedersen NL, & Gatz M (2010). Cognitive engagement and cognitive aging: Is Openness protective? Psychology and Aging, 25(1), 60–73. doi: 10.1037/a0018748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto CJ, John OP, Gosling SD, & Potter J (2011). Age differences in personality traits from 10 to 65: Big Five domains and facets in a large cross-sectional sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 330–348. doi: 10.1037/a0021717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soubelet A, & Salthouse TA (2011). Personality-cognition relations across adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 47(2), 303–310. doi: 10.1037/a0021816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan Y, Boiché J, Canada B, & Terracciano A (2014). Association of personality with physical, social, and mental activities across the lifespan: Findings from US and French samples. British Journal of Psychology, 105, 564–580. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Robins RW, & Terracciano A (2017). Parental educational attainment and adult offspring personality: An intergenerational lifespan approach to the origin of adult personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113, 144–166. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Damian RI, Luchetti M, Strickhouser JE, & Terracciano A (2019). Five-factor model personality traits and verbal fluency in 10 cohorts. Psychology and Aging, 34, 362–373. doi: 10.1037/pag0000351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Strickhouser JE, Aschwanden D, & Terracciano A (2021). The association between five factor model personality traits and verbal and numeric reasoning. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2021.1872481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, & Terracciano A (2019). Five-factor model personality traits and cognitive function in five domains in older adulthood. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 343. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1362-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Stephan Y, & Terracciano A (2018). Facets of conscientiousness and risk of dementia. Psychological Medicine, 48, 974–982. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717002306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Kitner-Triolo MH, Uda M, Schlessinger D, & Zonderman AB (2011). Personality traits prospectively predict verbal fluency in a lifespan sample. Psychology and Aging, 26(4), 994–999. doi: 10.1037/a0024276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Albanese E, & Sutin AR (2017). Personality traits and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 89, 22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautwein U, Lüdtke O, Roberts BW, Schnyder I, & Niggli A (2009). Different forces, same consequence: conscientiousness and competence beliefs are independent predictors of academic effort and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1115–1128. doi: 10.1037/a0017048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uttl B, White CA, Wong Gonzalez D, McDouall J, & Leonard CA (2013). Prospective memory, personality, and individual differences. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 130. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettstein M, Tauber B, Kuźma E, & Wahl HW (2017). The interplay between personality and cognitive ability across 12 years in middle and late adulthood: Evidence for reciprocal associations. Psychology and Aging, 32(3), 259–277. doi: 10.1037/pag0000166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.