Abstract

Ultrasmall gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are an emerging class of nanomaterials exhibiting distinctive physicochemical, molecular and in vivo properties. Recently, we showed that ultrasmall AuNPs encompassing a zwitterionic glutathione monoethyl ester surface coating (AuGSHzwt) were highly resistant against aggregation and serum protein interactions. Herein, we performed a new set of biointeraction studies to gain a more fundamental understanding into the behavior of both pristine and peptide-functionalized AuGSHzwt in complex media. Using the model Strep-tag peptide (WSHPQFEK) as an integrated functional group, we established that AuGSHzwt could be conjugated with increasing numbers of Strep-tags by simple ligand exchange, which provides a generic approach for AuGSHzwt functionalization. It was found that the strep-tagged AuGSHzwt particles were highly resistant to nonspecific protein interactions and retained their targeting capability in biological fluid, displaying efficient binding to Streptactin receptors in nearly undiluted serum. However, AuGSHzwt functionalized with multiple Strep-tags displayed somewhat lower resistance against protein interactions and lower levels of binding to Streptactin than monofunctionalized AuGSHzwt under given conditions. These results underscore the need for optimizing ligand density onto the surface of ultrasmall AuNPs for improved performance. Collectively, our findings support ultrasmall AuGSHzwt as an attractive platform for engineering functional, protein-mimetic nanostructures capable of specific protein recognition within the complex biological milieu.

INTRODUCTION

Ultrasmall gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) have recently emerged as attractive nanoformulations for in vivo disease diagnosis and therapy, especially in the area of cancer nanomedicine1–8. Owing to their small sizes (~ 1–3 nm in core diameter) and strong resistance against serum protein interactions, ultrasmall AuNPs are efficiently removed from circulation through renal clearance and show reduced levels of uptake in the liver and spleen. Ultrasmall AuNPs are also able to accumulate in the tumor tissue via the enhanced permeation and retention effect, resulting in uptake levels comparable to those of more conventionally large particles (~ 2–10 %ID/g)2.

The ability of ultrasmall AuNPs to resist nonspecific interactions with serum proteins in vivo is the result of both the particles’ small size and the antifouling properties of their especially designed surface coatings9–17. Concerning the effect of size, the limited contact area between ultrasmall particle and protein may in itself prevent the formation of long-lived interactions14, 18–20. For example, we have previously demonstrated the transient nature of ultrasmall AuNP-protein interactions by quantifying the kinetics of complex dissociation. Short residence times in the few-second time scale were obtained for the electrostatically-driven interactions between negatively charged AuNPs and the proteins CrataBL and α-thrombin19–20. However, fabrication of essentially “non-interacting” AuNPs requires even shorter residence times for complex dissociation in combination with very slow rate constants for complex association. This can be accomplished by surface passivation with PEG or zwitterionic ligands, which form strongly bound hydration layers generating repulsive forces against protein interactions21–23.

Among the different types of ultrasmall AuNPs and nanoclusters under development for in vivo applications, those coated with the natural tripeptide glutathione (GSH) have been most intensively investigated1, 4, 11, 24–25. However, it should be noted that GSH has a net charge of −1, hence it is not a true zwitterion. As a result, we have found that ultrasmall GSH-coated AuNPs (AuGSH) are not colloidally stable in biological fluid above a size threshold around 2 nm26, owing in part to the aggregating action of divalent cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ 26–27. To overcome the size-dependent stability of AuGSH, we therefore prepared new ultrasmall AuNPs by substitution of the negatively charged GSH ligand for its zwitterionic derivative – glutathione monoethyl ester (GSHzwt; Fig. 1a)28. Indeed, the new AuGSHzwt particles displayed better colloidal stability in biological media than AuGSH, while also being highly resistant against serum protein interactions.

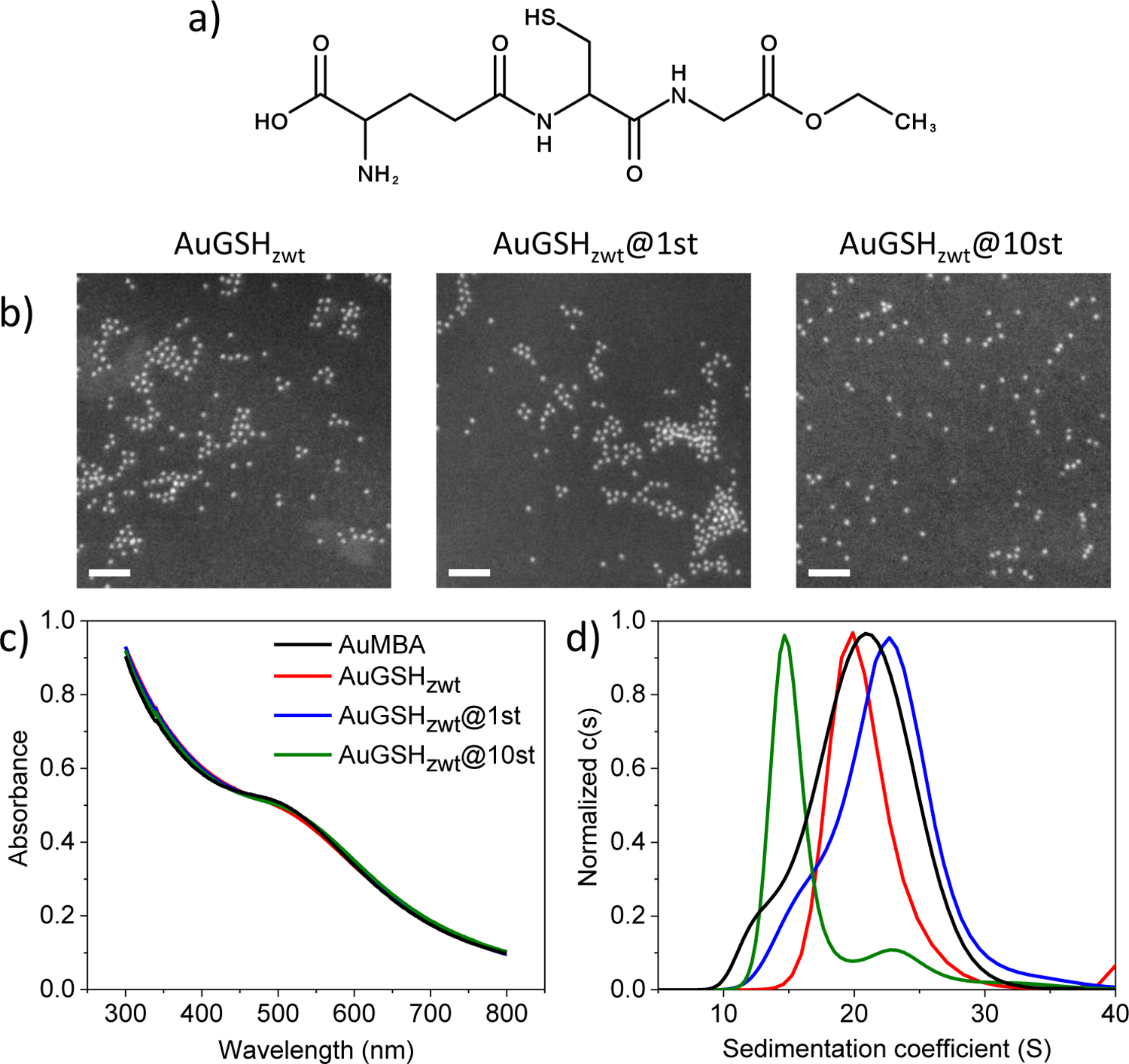

Figure 1.

Nanoparticle characterization. (a) Structure of glutathione monoethyl ester (GSHzwt). GSHzwt is a zwitterionic derivative of glutathione having an ethylated C-terminus. (b) AuNP characterization by dark-field scanning-transmission electron microscopy. Nanoparticles are approximately 2 nm in core diameter. Scale bar, 20 nm. (c) AuNP characterization by UV-visible spectroscopy. (d) AuNP characterization by analytical ultracentrifugation (colors as in (c)).

The general antifouling properties of ultrasmall AuNPs raise the possibility that they could be conjugated with additional functional moieties providing desired molecular-recognition properties29–31. Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated the fabrication of ultrasmall AuNPs covered with targeted peptides for the recognition of intracellular proteins and membrane receptors30, 32–41. Nonetheless, additional work is still needed to characterize and understand in more detail the behavior of functional ultrasmall AuNPs in complex media. For example, there is surprisingly little work done on the functionalization of the widely used ultrasmall AuGSH particles with peptides and systematic evaluation of the corresponding constructs in biological media33, 42.

Previously, we attached the model Strep-tag II peptide (WSHPQFEK)43–44 onto ultrasmall AuGSHzwt and demonstrated the ability of these functionalized particles to interact with target Streptactin receptors28. Given the apparent superior properties of GSHzwt over standard GSH as a surface coating for ultrasmall AuNPs as mentioned above, we now extend upon this previous work and perform a more systematic investigation of AuGSHzwt behavior in complex media. For example, we show that ultrasmall AuGSHzwt can be functionalized with a single Strep-tag peptide for binding specifically to Streptactin receptors in nearly undiluted serum. We conclude that ultrasmall AuGSHzwt constitutes an attractive model platform for creating functional protein-mimetic nanostructures through the attachment of bioactive peptides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and reagents

Glutathione monoethyl ester was obtained from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland). p-mercaptobenzoic acid (>95%) was purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR). The peptides ECGGG-WSHPQFEK and ECGGG-WSHPQFEK(FITC) (>95%) were synthesized by LifeTein (Somerset, USA). Streptactin-coated sepharose beads, Strep-tag and fluorescently-labeled Streptactin (Streptactin Oyster 645 conjugate) were purchased from IBA GmbH (Göttingen, Germany). The remaining reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solutions (pH 7.4; supplemented with 150 mM NaCl) were prepared before each experiment following standard protocols. The cocktail of protease inhibitors used to prevent the enzymatic degradation of Strep-tag in fetal bovine serum (FBS) consisted of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (10 mM), tosyl-L-lysyl chloromethane hydrochloride (100 μM), benzamidine (10 μM) and 1.1-phenanthroline monohydrate (5 mM).

Nanoparticle synthesis

Ultrasmall AuNPs coated with p-mercaptobenzoic acid (MBA) ligands (AuMBA) were synthesized as described in previous reports26, 28, 45 and utilized in ligand exchange reactions with GSHzwt to produce AuGSHzwt. In a typical ligand exchange, 10 nmol of AuMBA in 100 μL PBS were treated with 10 μmol of GSHzwt at room temperature for 1h. The resulting AuGSHzwt particles were precipitated by the addition of 100 μL ethanol and 20 μL ammonium acetate, washed with water and re-precipitated a few times, dried in air, then finally resuspended in 100 μL PBS. Functionalization with Strep-tag was accomplished by treating AuMBA with ECGGG-WSHPQFEK for 1h followed immediately by the addition of GSHzwt as described above. Different feed ratios of peptide:AuMBA (1:1, 1:2, 1:5, 1:1, 5:1, 10:1, 20:1, 50:1, 100:1 and 200:1) were used in the ligand exchange reactions to produce AuGSHzwt with distinct functionalization levels. AuGSHzwt particles coated with ECGGG-WSHPQFEK(FITC) were also prepared in a similar way.

Quantification of Strep-tag incorporation

For peptide:AuMBA feed ratios > 5:1, the number of Strep-tags attached per AuGSHzwt was quantified by fluorescence spectroscopy by measuring the emission signal from tryptophan and comparing to a calibration curve. Prior to the measurements, the AuNPs (1 μM) were etched with the reducing agent TCEP (50 μM). The corresponding calibration curve was constructed by the addition of known quantities of Strep-tag to AuGSHzwt followed by the addition of TCEP for etching. The number of Strep-tag(FITC) per AuGSHzwt was quantified in a similar way, but using the emission signal from FITC and Strep-tag(FITC) to build the calibration curve.

UV-visible spectroscopy, scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC)

UV-visible spectra of the AuNPs in PBS buffer and in DMEM culture medium (without phenol red) were acquired on a Shimadzu UV1800 spectrophotometer. Dark-field STEM imaging of the AuNPs was performed on an FEI Tecnai TF30 TEM/STEM operating at 300 kV as previously described26. Sedimentation velocity experiments were performed in an Optima XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter) following standard protocols46–48. The AuNPs (0.5–5 μM) in PBS buffer or mixed with bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS (at 20 mg/mL) were loaded into AUC cell assemblies with 12 or 3 mm Epon Charcoal-filled double-sector centerpieces and sapphire windows. After loaded into the rotor, the cells were subjected to 2 h temperature equilibration at 20 °C, followed by acceleration to 20,000 rpm. The sedimentation profiles of the AuNPs were monitored by recording absorbance scans at 500 nm and by Rayleigh interferometry. This allows direct visualization of particles up to ~ 500 S, and indirect assessment of larger aggregates through depletion of the measured concentration of sedimenting particles > 500 S. The acquired data were analyzed according to the standard c(s) analysis routine in SEDFIT49. The c(s) distributions for the samples in 20 mg/mL BSA were corrected with an empirical nonideality coefficient (0.009 mL/mg) for the sedimentation coefficient.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was used to characterize the ultrasmall AuNPs in PBS (as control), in 40 mg/mL BSA and in undiluted FBS. The AuNPs were pre-incubated in the different media for either 1 or 24 h, loaded into freshly prepared gels, and run using a Mini-PROTEAN Tetra electrophoresis system from Bio-Rad. The runs were done at a voltage of 70 V for the stacking gel and 110 V for the running gel. Running gels (15%) were prepared with 2.05 M of acrylamide, 25.95 mM of bis-acrylamide, 0.374 M of Tris-HCl, 76.72 mM of TEMED and 2.35 mM of ammonium persulfate. Running gels of lower density (7.5%) were made up with 1.03 M of acrylamide and 12.97 mM of bis-acrylamide. Stacking gels (5%) in turn were prepared as 0.46 M of acrylamide, 5.81 mM of bis-acrylamide, 0.127 M of Tris-HCl, 88.06 mM of TEMED and 4.44 mM of ammonium persulfate. The running buffer was 0.05 M Tris at pH 8.3 and all the samples were diluted 2x in loading buffer at pH 6.68.

Microscale thermophoresis

Measurements of free Strep-tag binding to free oyster-labeled Streptactin were performed by microscale thermophoresis using a Monolith NT.115 instrument from Nanotemper technologies (Munich, Germany). Strep-tag was pre-incubated in PBS, in 20 mg/mL BSA or in 50% FBS for either 1 or 24 h prior to the measurements. The incubations in FBS were done both in the absence and presence of protease inhibitors. Next, the Strep-tag solutions were serially diluted in the range from ~ 1 nM to 100 μM Strep-tag and mixed with a definite amount of oyster-labeled Streptactin (yielding 50 nM Streptactin in the final mixture) in the presence of 0.05% Tween; each dilution point was measured in triplicate. The resulting mixtures were loaded into standard treated capillary tubes and inserted into the instrument for data acquisition. Binding curves were generated by monitoring changes in thermophoresis (expressed as ΔFnorm) as a function of Strep-tag concentration.

Affinity chromatography and affinity pull-down experiments

Streptactin sepharose columns were prepared as per manufacturer’s instructions. The Streptactin columns were used primarily to separate the small fraction of strep-tagged AuGSHzwt from excess unmodified particles during the course of monofunctionalization. Elution of immobilized strep-tagged AuGSHzwt was accomplished with a solution of 10 mM NaOH (we purposely avoided using biotin or desthiobiotin for elution since they would interfere with the subsequent binding experiments if not removed completely from solution). For the affinity pull-down experiments, AuGSHzwt, AuGSHzwt@1st and AuGSHzwt@10st were added to different biological media (PBS, DMEM culture medium, 40 mg/mL BSA, and undiluted FBS supplemented with protease inhibitors) at a concentration of 1–2 μM and left to incubate for 24 h under mild agitation; a shorter incubation time of 1 h was also used for the AuNPs in FBS. Next, 100 μL of the AuNP solutions were added to 100 μL of drained beads solution and left to incubate for 30 min under mild agitation. After settling of the beads, the presence of AuNPs in the supernatant was verified by recording absorbance measurements at 500 nm. Samples prepared in a similar way but in the absence of AuNPs were used for background subtraction.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Nanoparticle synthesis and characterization

Ultrasmall ~ 2 nm-sized AuMBA particles45, 50–51 were synthesized as described in previous reports26, 28, 45 and utilized in ligand exchange reactions with GSHzwt to produce AuGSHzwt. Characterization by STEM revealed that AuGSHzwt had an average core diameter around 2 nm (Fig. 1b). This was consistent with the UV-visible spectrum of the particles, which showed the presence of a shoulder but lack of a distinct surface plasmon resonance peak near 500 nm (Fig. 1c, red trace). Characterization of AuGSHzwt by AUC revealed a distribution of sedimentation coefficients (s) centered around 20 S (Fig. 1d, red trace). As a reference, previous AUC measurements of MBA- and GSH-coated AuNPs with core sizes ranging from ~ 1.5 to 2.5 nm produced a spread in s-value distributions from about 10 to 30 S26. UV-visible spectroscopy and AUC data for the parent AuMBA particles are also shown in Fig. 1 for comparison (Fig. 1c and 1d, black traces).

Ultrasmall AuGSHzwt was functionalized with Strep-tag II (WSHPQFEK) by performing ligand exchange of AuMBA with ECGGG-WSHPQFEK and GSHzwt. Here, cysteine was introduced to anchor the extended Strep-tag peptide onto the Au surface via an Au-S bond, glutamate was introduced to increase the cone angle of the ligand, and the three glycine residues were added to keep the actual Strep-tag portion of the peptide sufficiently separated from the AuNP surface28. Different feed ratios of peptide:AuMBA (5:1, 10:1, 20:1, 50:1, 100:1 and 200:1) were employed to produce AuNPs with distinct functionalization levels. Successful functionalization was confirmed from the complete immobilization of strep-tagged AuGSHzwt to a Streptactin sepharose column; in comparison, unfunctionalized AuGSHzwt used as control did not bind the column and was readily eluted with PBS (not shown).

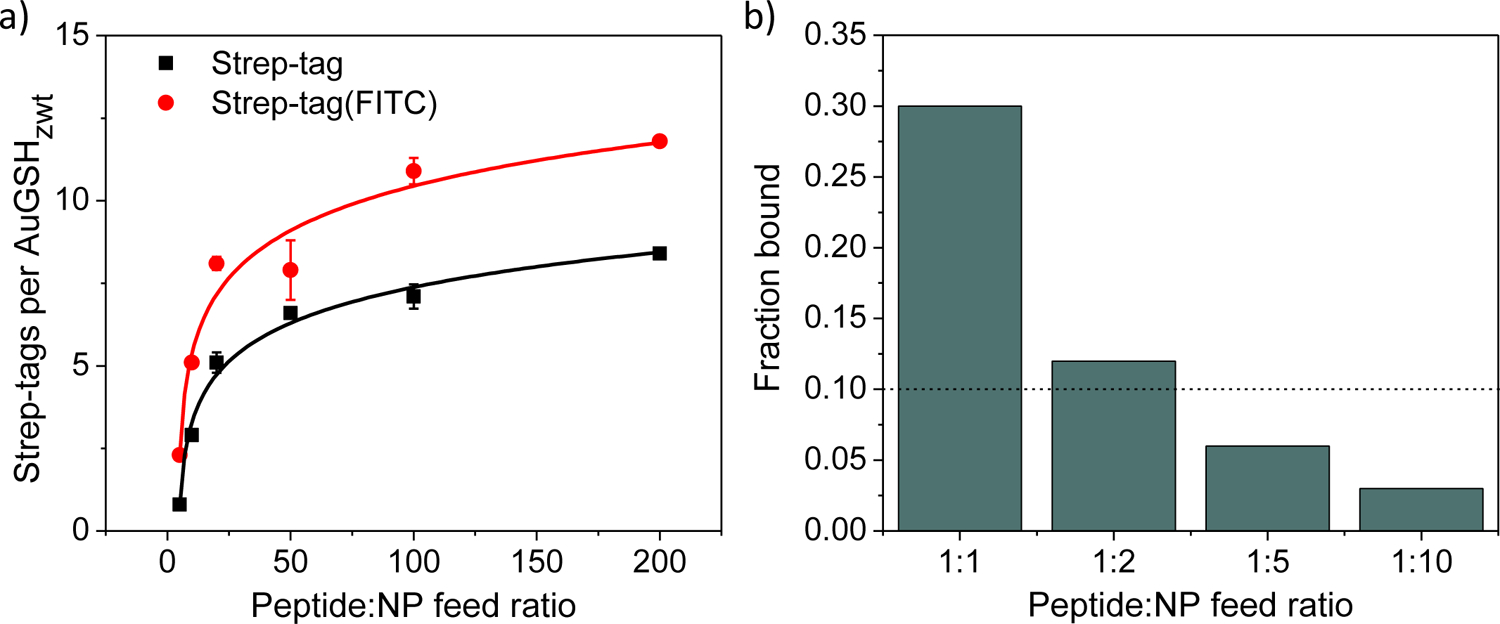

The number of Strep-tag ligands attached per AuNP was estimated by recording the fluorescence emission signal from the peptide (due to tryptophan) and comparing to a calibration curve. Due to strong quenching of the fluorescence emission from the gold core, the AuNPs were first etched with the reducing agent TCEP prior to the measurements. Fig. 2a shows that the number of Strep-tags saturated as a function of feeding ratio, reaching a maximum of ~ 8 peptides per AuGSHzwt. Of note, functionalization of ultrasmall AuNPs via ligand exchange yields a heterogeneous nanoparticle preparation containing a statistical distribution of Strep-tags. Therefore, the experimentally determined numbers of Strep-tags per AuGSHzwt as shown in Fig. 2a correspond to average values. In order to confirm these results using a more sensitive method, Strep-tag was synthesized to contain a fluorescein (FITC) moiety at its C-terminal lysine and introduced onto the AuNPs as before via ligand exchange. The number of attached Strep-tag(FITC) ligands was quantified by fluorescence spectroscopy using the emission signal from FITC52, yielding similar results as the tryptophan measurements (Fig. 2a). In this work, AuGSHzwt particles functionalized with the average maximum number of ~ 10 Strep-tags (AuGSHzwt@10st) were selected for further investigation as described in the next sections.

Figure 2.

Functionalization of ultrasmall AuGSHzwt with Strep-tag. (a) Number of Strep-tag or Strep-tag(FITC) ligands attached per AuGSHzwt as a function of the peptide:AuMBA feed ratio (from 5:1 to 200:1). A maximum of ~ 10 Strep-tags are incorporated per AuNP at the highest feed ratio of 200:1. Quantification was performed by fluorescence spectroscopy using the emission signal from tryptophan or FITC. (b) Percentage of AuGSHzwt particles bound to Streptactin-coated beads as a function of the peptide:AuMBA feed ratio. The use of sufficiently low feed ratios (1:5 or 1:10) results in bound fractions smaller than 10% (dashed line), which implies monofunctionalization of the particles53.

Next, AuGSHzwt particles containing a single Strep-tag peptide (AuGSHzwt@1st) were prepared. This was accomplished by using AuMBA in excess relative to Streptag during ligand exchange (peptide:AuMBA feed ratios of 1:1, 1:2, 1:5 and 1:10). AuGSHzwt with Strep-tags attached were purified from excess unmodified particles by affinity chromatography using a Streptactin column. The fractional concentration of AuGSHzwt containing Strep-tags was then calculated after eluting from the column, and the results were plotted as a function of feed ratio as shown in Fig. 2b. It can be noticed that only a small fraction of AuGSHzwt (< 10%) was functionalized with Strep-tag at the lower feed ratios of 1:5 and 1:10, which, based on statistical considerations, implied the presence of a single Strep-tag per AuNP53. To understand this, we consider the statistical spread of ligands onto the surface of nanoparticles, which can be well approximated by a Poisson distribution, especially in the regime of low functionalization: P(k) = λk e−λ/k!53–54. Given a distribution mean of λ = 0.1, Poisson statistics predicts that approximately 90% of AuNPs will remain unmodified and 10% will contain a single peptide, whereas a negligible percentage (< 1%) of AuNPs will contain two or more peptides attached.

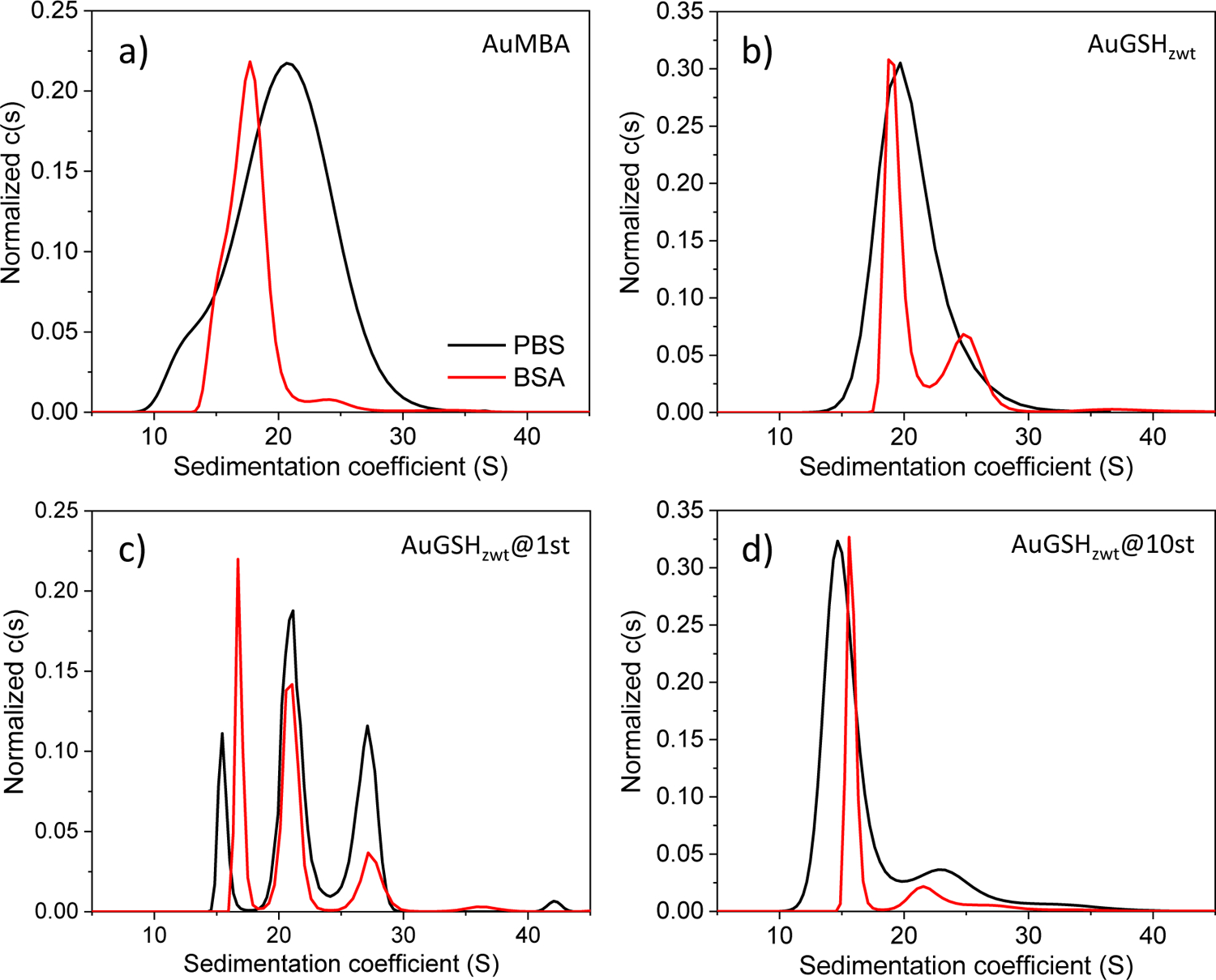

Fig. 1 presents additional characterization data for AuGSHzwt@1st and AuGSHzwt@10st. STEM and UV-vis spectroscopy showed that the functionalized AuGSHzwt particles had similar core diameters as the pristine ones (~ 2 nm). Characterization by AUC revealed similar peak maxima of ~ 20–23 S among the parent AuMBA, AuGSHzwt and AuGSHzwt@1st particles, but a much lower maximum of 14.7 S for AuGSHzwt@10st. The latter can be explained by increased hydrodynamic friction caused by the presence of multiple Strep-tags onto the surface of AuGSHzwt@10st.

Characterization of nanoparticle behavior in biological media

The stability of AuGSHzwt, AuGSHzwt@1st and AuGSHzwt@10st in biological medium was evaluated by incubating the AuNPs in pure DMEM medium for 24 h, followed by UV-vis spectroscopy characterization. The results revealed no signs of AuNP aggregation or degradation as judged from the UV-visible spectral profiles of the samples (Suppl. Fig. S1).

We next investigated the ability of the different AuNPs to resist interactions with serum proteins. It should be first recalled that the characterization of ultrasmall AuNPs in protein-rich media requires different approaches than those typically employed to study protein adsorption onto conventionally large particles14, 26, 55–56. This is because protein interactions with water-soluble ultrasmall AuNPs are inherently short-lived and thereby need to be studied in situ; experimental methods that perturb the binding equilibrium (the main example being centrifugation followed by washing) are not appropriate.

Native gel electrophoresis is one technique that is commonly employed for the characterization of ultrasmall nanoparticles in serum14, 55, 57. It is based on the principle that unbound nanoparticles may be partly separated from interacting ones as a result of differences in their electrophoretic mobility in the gel. However, there are important limitations to be taken into consideration. One shortcoming is that samples are not strictly maintained in situ during the electrophoresis run due to the separation of bands. On the other hand, the gel matrix can enhance the stability of complexes compared to when they are free in solution via the sequestration and cage effects58–59.

We first used gel electrophoresis to characterize ultrasmall AuMBA in FBS, noting that AuMBA was employed here as a control AuNP and model for “strong” interactions. Specifically, we have previously measured apparent binding affinities in the mid-nM range (KD ~ 30–200 nM) for AuMBA binding to the model proteins α-chymotrypsin, CrataBL and α-thrombin19–20, 60, whereas kinetic measurements of AuMBA-protein complex dissociation revealed residence times in the range from ~ 0.1 to 20 s19–20. AuMBA was incubated in undiluted FBS for 1 h under mild agitation prior to loading into a 15% polyacrylamide gel matrix. For comparison purposes, AuMBA was also incubated in 40 mg/mL BSA, which corresponds to the BSA concentration found in serum. A significant band shift for AuMBA was observed in both FBS and BSA relative to a PBS control (Fig. 3a).

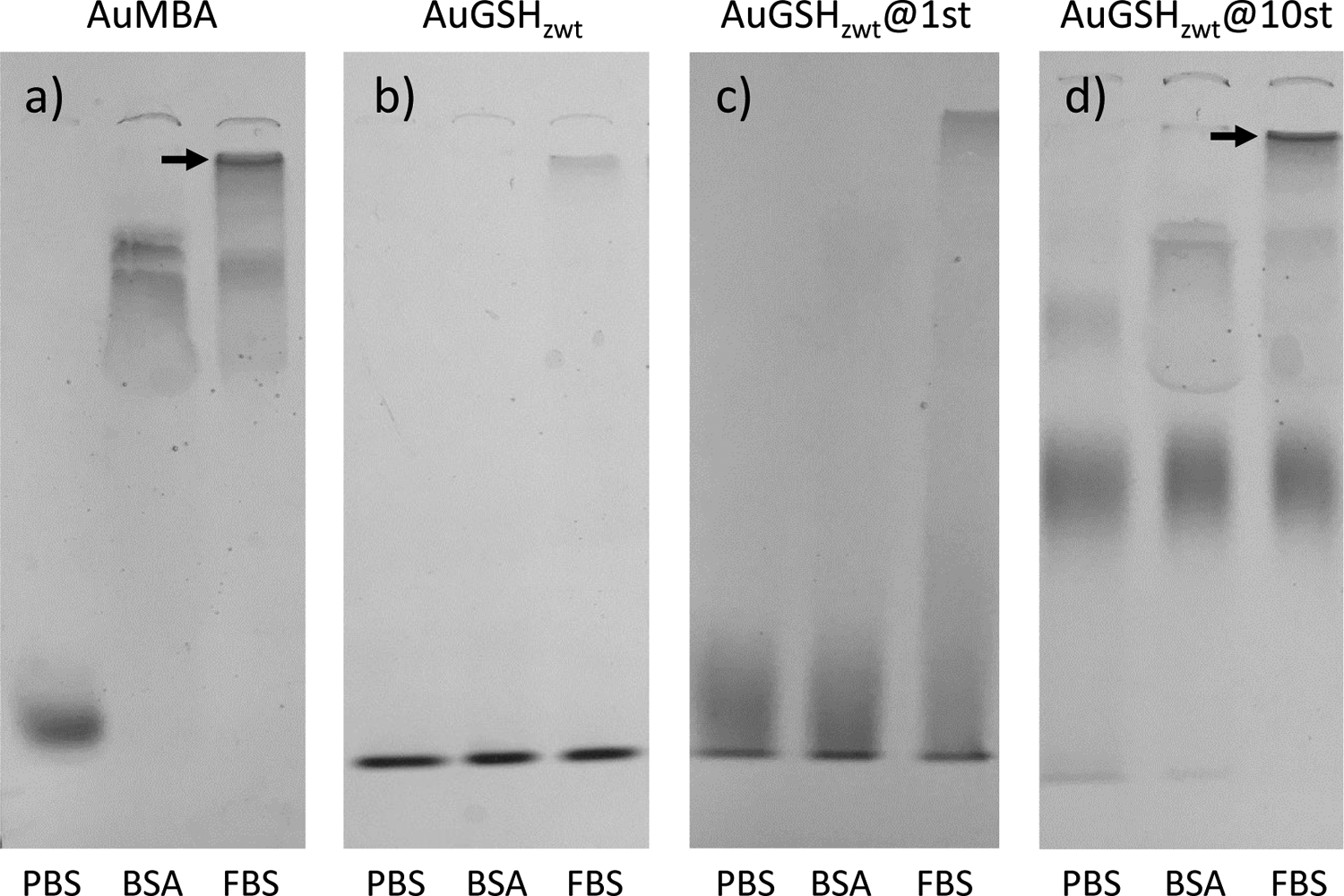

Figure 3.

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis characterization of ultrasmall AuNPs in biological media. Data were obtained for (a) AuMBA, (b) AuGSHzwt, (c) AuGSHzwt@1st and (d) AuGSHzwt@10st in PBS, 40 mg/mL BSA and fetal bovine serum (FBS). The AuNPs were pre-incubated in the different media for 1 h prior to loading into the gel. The percentage of acrylamide in the running and stacking gels were 15 and 5%, respectively. Arrows mark the interface between the stacking and running gels where AuMBA and AuGSHzwt@10st accumulate.

The migration of unfunctionalized AuGSHzwt through the gel was investigated under identical experimental conditions to AuMBA (Fig. 3b). Aside from a very faint smear for AuGSHzwt in FBS, no other signs of interactions were observed, in agreement with the strong resistance of AuGSHzwt against protein binding28.

Next, we used gel electrophoresis to characterize the behavior of strep-tagged AuGSHzwt in the different media (Fig. 3c and 3d). We first notice that running these functional AuNPs in PBS resulted in smeared bands in the gel, especially for AuGSHzwt@10st, which was expected given that AuGSHzwt@10st is a heterogeneous nanoparticle preparation containing a statistical distribution of Strep-tags. It can be also seen that AuGSHzwt@10st migrated slower than the other AuNPs as a result of its larger average size. Nevertheless, it was still possible to observe clear differences in AuNP mobility in the gel as a result of interactions with serum. For example, interactions of AuGSHzwt@1st with FBS led to noticeable changes in particle mobility in the form of a smear (Fig. 3c). The observed smearing, but lack of any clear band shift for the AuGSHzwt@1st particles, suggests that they undergo somewhat stronger interactions with proteins than pristine AuGSHzwt, but still much weaker interactions when compared to the AuMBA control. Thus, addition of a single Strep-tag peptide onto the surface of AuGSHzwt confers a new chemical identity to the AuNPs leading to increased interactions with serum proteins. Interestingly, AuGSHzwt@1st mobility in the gel was not affected by incubating in BSA (Fig. 3c), implying that there must be specific proteins or classes of proteins in FBS to which AuGSHzwt@1st binds more readily. The stronger interactions of AuGSHzwt@1st in FBS relative to BSA might be partly explained by nonspecific Strep-tag binding to FBS proteins. Evidence for this came from the analysis by microscale thermophoresis of free Strep-tag binding to free fluorescently-labeled Streptactin, which showed weakened binding in FBS but not in BSA (Fig. 5; vide infra).

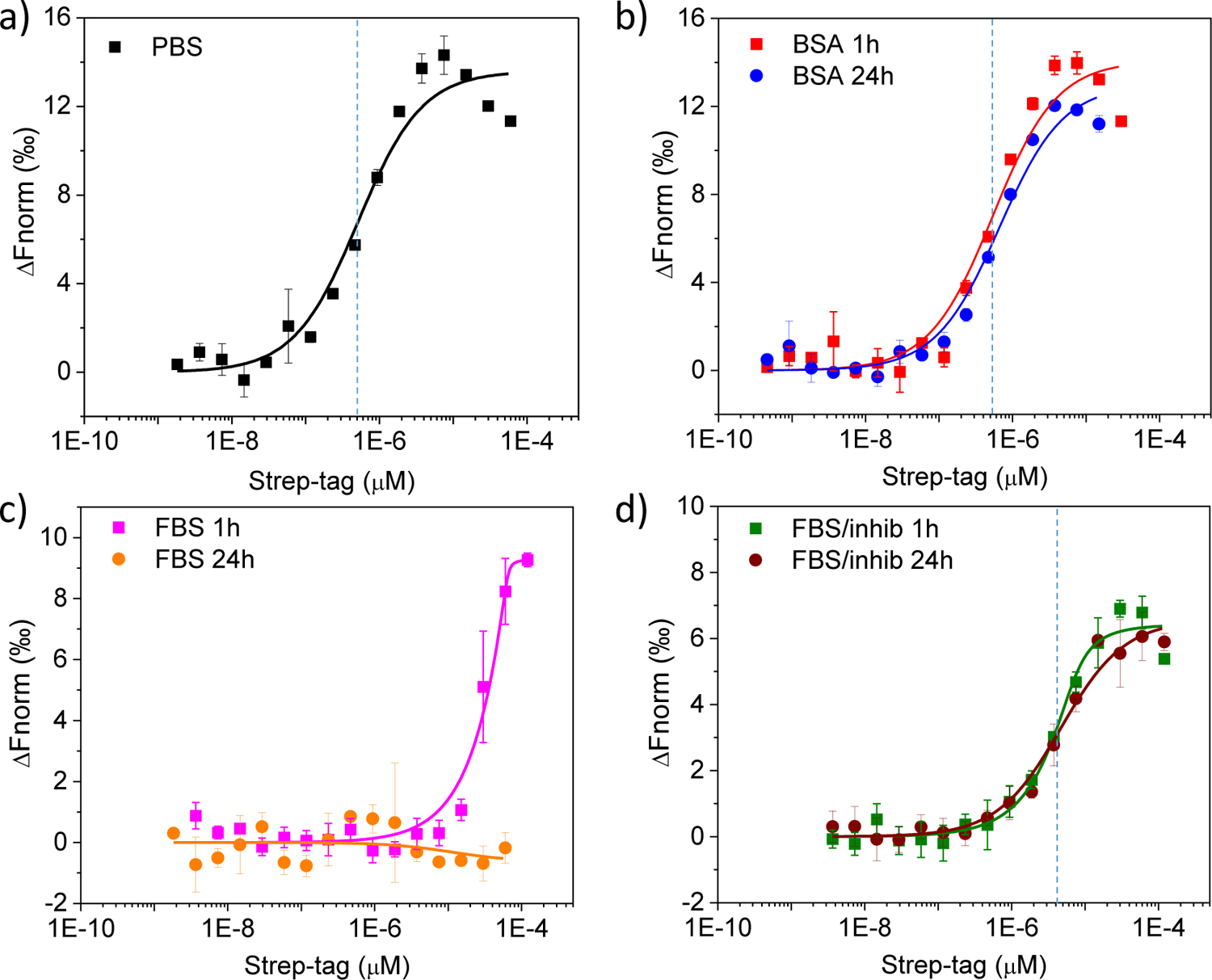

Figure 5.

Thermophoresis binding curves obtained for free Strep-tag titrated against free fluorescently-labeled Streptactin. Data obtained in (a) PBS, (b) 20 mg/mL BSA, (c) 50% FBS and (d) 50% FBS supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors. Strep-tag was pre-incubated in the different media for either 1 h (squares) or 24 h (circles). Dashed lines mark the approximate values of apparent binding affinity.

Analysis of the multiply functionalized AuGSHzwt@10st particles by gel electrophoresis suggested that they interact more strongly to serum proteins than AuGSHzwt@1st. One evidence for this came from the increased smearing observed for AuGSHzwt@10st in BSA relative to AuGSHzwt@1st (Fig. 3c and 3d; see also Suppl. Fig. S3). Second, AuGSHzwt@10st in FBS was found to accumulate at the interface between the stacking and running gels (Fig. 3d, arrow mark; the same can be seen for AuMBA, Fig. 3a). This later observation can be understood on the basis that large serum proteins cannot penetrate through the narrower pores of the running matrix, thus remaining trapped at high concentrations in the stacking gel and leading to increased levels of nonspecific interactions with AuGSHzwt@10st and AuMBA.

We next compared the behavior of AuMBA and the strep-tagged AuGSHzwt particles in FBS using a 7.5% running gel, noting that serum proteins can migrate more easily in this lower-density gel because of its larger pore size. Characterization of strep-tagged AuGSHzwt in FBS showed no particle accumulation in the stacking gel and almost no visible smearing in the running gel, whereas for AuMBA there was significant smearing alongside the disappearance of the corresponding band for free AuMBA (Suppl. Fig. S2). This result is consistent with the notion that strep-tagged AuGSHzwt migrates through the 7.5% gel mostly as free particles disassociated from proteins, whereas AuMBA migrates strongly complexed to proteins of different sizes.

We also evaluated the influence of a longer pre-incubation time of the AuNPs in the different media on their electrophoretic mobility in the gel (Suppl. Fig. S3). Samples were incubated in BSA or FBS for 24 h under mild agitation and loaded into a 15% polyacrylamide gel. The results did not reveal obvious changes to AuNP mobility after 24 h, suggesting no significant “hardening” of the initially weak interactions with time, as often observed with nanoparticles of larger size56. However, it should be noted that gel electrophoresis may not be sensitive enough to capture subtler changes to the antifouling properties of the AuNPs as a function of time.

We finally employed AUC as an independent and more sensitive tool to investigate the interactions of the ultrasmall AuNPs with proteins in situ (Fig. 4)26, 61–62. AuMBA was used again as a model nanoparticle system undergoing “strong” interactions with proteins, and BSA was used as a model protein. As expected, only AuMBA-BSA interactions led to a significant shift of the sedimentation coefficient distributions to lower s-values (Fig. 4a). Nevertheless, the results revealed the occurrence of weak interactions of BSA with both pristine and strep-tagged AuGSHzwt, as judged from the altered sedimentation coefficient distribution profiles of the particles (Fig. 4b, c and d). We recall that gel electrophoresis did not clearly reveal the occurrence of such weak interactions of AuGSHzwt and AuGSHzwt@1st with BSA. One interesting observation for AuGSHzwt@1st is the presence of three major peaks in the sedimentation coefficient distributions (Fig. 4c), which became apparent when the data was probed in more detail with a lower level of regularization. This highlights the heterogeneity of the sample, possibly representing AuGSHzwt@1st particles of different size subgroups. In more detail, it can be seen that the major population of AuGSHzwt@1st particles sedimenting at ~ 21 S was not visibly affected by the presence of BSA, hence suggesting the occurrence of ultraweak interactions of this subgroup beyond detectability.

Figure 4.

Analytical ultracentrifugation analysis of ultrasmall AuNPs dispersed in concentrated BSA solutions. Sedimentation coefficient distributions for (a) AuMBA, (b) AuGSHzwt, (c) AuGSHzwt@1st and (d) AuGSHzwt@10st measured in PBS (black traces) and 20 mg/mL BSA (red traces). A confidence level of 68% was used for (a), (b) and (d), while 55% was used for (c).

It can be further discerned that the sedimentation rate of AuGSHzwt@10st appeared shifted to higher s-values upon BSA binding (Fig. 4d), whereas that of AuGSHzwt appeared shifted to lower s-values (Fig. 4b). This can be understood on the basis of theoretical calculations, which showed that for a 2 nm-sized AuNP the dependence of sedimentation rate on protein loading displays a non-monotonic behavior, with a decrease of s-value at low protein fractions at first driven by increased hydrodynamic friction of the complex, followed by an increase of s-value at higher protein fractions driven by added protein mass (Suppl. Fig S4). Thus, for AuGSHzwt@10st, the added peptide mass relative to AuGSHzwt shifts the s-value from ~ 20 S to 15 S due to increased friction, whereas the additional mass accompanying BSA binding shifts the distribution back to higher s-values.

Proper quantitation of ultrasmall AuNP-protein binding solely based on sedimentation coefficients may be difficult due to the effects note above. Nonetheless, we can make a back-of-the-envelope estimate of the AuNP-BSA affinity based on a combined analysis of the AUC and electrophoresis results. Since BSA is in molar excess, mass action law predicts that the ratio of free to bound nanoparticles equals KD relative to the BSA concentration (0.3 mM). The AUC data suggests that a significant fraction, but far from all AuNPs is liganded by BSA, which places the KD on the mM order of magnitude.

Characterization of targeted nanoparticle-receptor interactions in biological media

Strep-tag II is widely used as an affinity tag for the purification of recombinantly expressed proteins43. It binds the protein Streptactin with an apparent KD of ~ 1 μM (according to the manufacturer). Detailed knowledge about the environmental factors modulating free peptide-receptor association is required to assist the analysis of more complex situations, such as with immobilized peptides on a nanoparticle surface. Therefore, we first characterized free Strep-tag binding to free fluorescently-labeled Streptactin by microscale thermophoresis, a technique enabling the characterization of biomolecular interactions in complex media63–64. Thermophoresis binding curves obtained for Strep-tag titrated against Streptactin are shown in Fig. 5. Plotting the data on a semi-log scale revealed a characteristic S shape, thus allowing for easy inspection of the relative differences in binding affinity. The interactions measured in both PBS and BSA with 1 h pre-incubation revealed an observed apparent KD of ~ 0.5 μM (Fig. 5a and 5b, red trace). On the other hand, a much weaker apparent binding affinity was measured in 50% FBS as judged from the significant shift of the S-shaped curve to the right (Fig. 5c, magenta trace), this being partly the result of Strep-tag cleavage by the action of serum proteases. Extending the pre-incubation time to 24 h did not produce significant changes to the interactions measured in BSA (Fig. 5b, blue trace), whereas it caused complete lack of binding in 50% FBS (Fig. 5c, orange trace). Degradation of Strep-tag in serum could be prevented by co-incubation of the samples with a cocktail of protease inhibitors, in which case the binding curves appeared superimposed on each other regardless of the pre-incubation time in FBS (Fig. 5d). Thus, all subsequent binding experiments in FBS were carried out in the presence of protease inhibitors to minimize the enzymatic degradation of Strep-tag. Of note, the observed apparent KD determined in FBS supplemented with protease inhibitors was estimated as ~ 4 μM (Fig. 5d), hence suggesting that serum proteins other than albumin may interfere with Strep-tag binding to Streptactin.

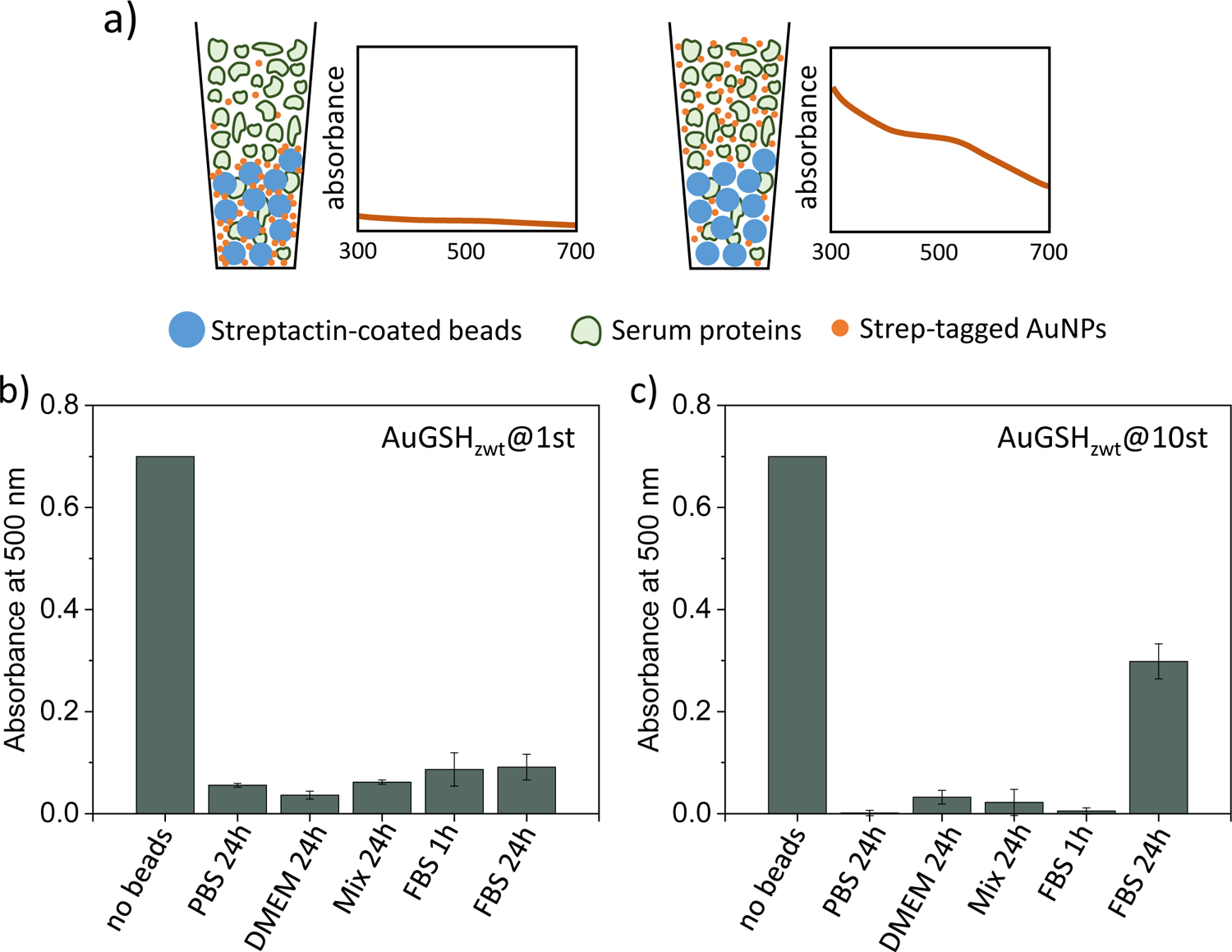

It is well-known that receptor-binding peptides may lose their targeting capability when immobilized onto the surface of nanoparticles65–66. This may occur due to a number of reasons, including detachment from the surface, steric self-hindrance effects, steric shielding from adsorbed serum proteins, among others. Previously, we showed that ultrasmall AuGSHzwt particles functionalized with Strep-tag could bind the target receptor Streptactin in FBS28. We now extend upon this previous work to characterize these interactions in more detail. For this, we ran a series of affinity pull-down experiments whereby we monitored the binding of Strep-tagged AuGSHzwt to Streptactin-coated sepharose beads. The assays were implemented in different biological media of increasing complexity including PBS, DMEM medium, 40 mg/mL BSA, and undiluted FBS. Fig. 6a illustrates the pull-down assay in a schematic fashion.

Figure 6.

Affinity pull-down experiment probing the binding of strep-tagged AuGSHzwt to Streptactin-coated sepharose beads. (a) Schematic illustration of the pull-down assay (drawing not to scale). Strep-tagged AuGSHzwt particles are dispersed in different biological media (including PBS, DMEM medium, 40 mg/mL BSA and undiluted FBS) and left to incubate for 24 h; a shorter incubation time of 1 h in FBS is also performed for comparison. Next, Streptactin-coated beads are introduced into solution and left to incubate for an extra 30 min under mild agitation. After settling of the beads, the presence of AuNPs in the supernatant is verified by recording absorbance values at 500 nm. Preferential binding of strep-tagged AuNPs to Streptactin over the serum proteins leaves a clear supernatant phase (low absorbance readings at 500 nm) in the pull-down assay. (b,c) Analysis of pull-down experiments probing (b) AuGSHzwt@1st and (c) AuGSHzwt@10st binding to Streptactin-coated beads. Columns labeled ‘no beads’ give absorbance readings of strep-tagged AuNPs in PBS solution in the absence of beads.

First, control experiments using pristine AuGSHzwt confirmed complete lack of binding to the Streptactin-coated beads (not shown). We next verified that AuGSHzwt@1st and AuGSHzwt@10st bound completely to the beads in PBS (Fig. 6b and 6c). In particular, the efficient binding of AuGSHzwt@10st implies that the surface-attached Strep-tags do not experience significant steric self-hindrance effects67, which otherwise could have occurred if the Strep-tag surface density was exceedingly high. Efficient nanoparticle binding to the beads was also observed in DMEM medium, hence suggesting no Strep-tag detachment from the surface as a result of ligand exchange from the endogenous cysteine in DMEM. The strep-tagged AuNPs also bound to the beads in the presence of BSA, implying no major steric shielding as a result of interactions with BSA.

We finally characterized the interactions in FBS. We found that both AuGSHzwt@1st and AuGSHzwt@10st bound efficiently to the beads following a 1 h pre-incubation time in undiluted FBS (Fig. 6b and 6c). However, incomplete binding occurred following a longer incubation time of 24 h in the case of AuGSHzwt@10st. The diminished binding observed at 24 h is not the result of peptide cleavage by serum proteases, as the pre-incubations were done in the presence of protease inhibitors. In addition, AuGSHzwt@1st would be expected to show less binding to the beads than AuGSHzwt@10st as a result of peptide degradation, but which was not observed. In fact, the opposite trend seemed to occur, that is, AuGSHzwt@1st containing a single Strep-tag bound more efficiently to the beads than AuGSHzwt@10st. These results suggest increased levels of nonspecific serum protein binding to the AuGSHzwt@10st particles over time, which would then partly screen their interactions to Streptactin.

Influence of nonspecific protein interactions on specific nanoparticle-receptor complexation

The formation of a stable protein adsorption layer (hard protein corona) onto certain large-sized nanoparticles (NPs) can irreversibly mask the NP surface and inhibit specific ligand-receptor interactions65, 68–70. Remarkably, even biotinylated NPs can fail to bind streptavidin in serum despite the ultrahigh affinity of the biotin-streptavidin interaction pair70.

On the other hand, accumulating evidence suggests that the interactions of proteins with ultrasmall AuNPs are inherently reversible14, 19–20. This reversibility enables us to consider the following set of biochemical equilibria representing the competition between nonspecific NP-serum protein interactions and specific NP-receptor complexation:

Where R stands for receptor and P for nonspecific protein binding site, noting that the concentration of nonspecific binding sites ([P]) may be greater than the nominal concentration of proteins in serum (as a reference, the plasma concentration of albumin alone is around 0.5 mM71); KD,P1 through KD,P4 are the apparent macroscopic equilibrium dissociation constants for NP-serum protein interactions; KD,R is the equilibrium dissociation constant for NP-receptor complexation. It has been further assumed that: the receptor is monomeric; the NPs are functionalized with a single targeting ligand; the maximum binding capacity of the NPs is 4 serum proteins per particle; NPs bound to any number of serum proteins do not interact with receptors.

Given the above model, we used simulations to calculate the fractional receptor occupancy as a function of the reduced variable [P]/KD,P (Suppl. Fig. S5a). Assuming KD,R = 10 nM, [R] = 0.1 μM and [NP] = 10 μM, the calculations revealed that ~ 85% of receptors would be bound with NPs for a [P]/KD,P ratio of 3. In comparison, receptor occupancy would be only 5% for the same [P]/KD,P ratio of 3 in the case of a 100-fold weaker NP-receptor binding affinity of KD,R = 1 μM. This illustrates that weak transient NP-serum protein interactions can interfere with targeted NP-receptor complexation depending on the relative values of binding affinities and concentrations. Of note, the simple calculation presented here is only valid for a closed system under thermodynamic equilibrium. However, in the context of the open in vivo environment, where the total concentration of ultrasmall AuNPs in circulation decreases with time as a result of renal clearance, receptor occupancy is predicted to be maximized for a narrow range of KD,P values (see ref.72 for details).

Finally, the results of the affinity pull-down experiments for AuGSHzwt@1st can be interpreted semi-quantitatively in the framework of the proposed model. Additional simulations showed that the ratio [P]/KD,P should be < 0.5 to give an efficiency over 90% for the binding of AuGSHzwt@1st to Streptactin (Fig. 6b and Suppl. Fig. S5b); where it has been assumed that KD,R ~ 1 μM, [R] ~ 50 μM (the approximate concentration of Streptactin contained in the beads solution), and [NP] = 1 μM. Thus, assuming a total concentration of nonspecific protein binding sites of ~ 1 mM would yield a corresponding KD,P > 2 mM. The large magnitude of the estimated KD,P is certainly consistent with the results from gel electrophoresis and AUC as discussed above.

CONCLUSIONS

We recently reported the preparation of novel ultrasmall AuNPs coated with zwitterionic glutathione monoethyl ester28. The resulting AuGSHzwt particles were highly resistant against aggregation and nonspecific protein interactions, and they could be conferred with desired molecular-recognition properties through the incorporation of Strep-tag as a model functional peptide. Peptide incorporation could be readily achieved in simple ligand exchange reactions, therefore providing a generic approach for AuGSHzwt functionalization.

Herein, we performed a series of new biointeraction studies to gain further insights into the behavior of functionalized AuGSHzwt in complex media, using again the model Strep-tag peptide as an integrated functional group. We established that AuGSHzwt could be conjugated with increasing numbers of Strep-tags (from 1 to an average of ~ 10 peptides per AuNP) by simply controlling the reaction conditions. Both pristine and functionalized AuGSHzwt were highly (albeit not entirely) resistant to nonspecific protein interactions, with small differences in behavior noted among the different nanoparticles prepared: namely, unfunctionalized AuGSHzwt was mostly resistant to protein interactions, followed by AuGSHzwt@1st and AuGSHzwt@10st, respectively. Nevertheless, as a consequence of the weak and transient nature of AuGSHzwt nonspecific interactions with serum proteins, the strep-tagged particles retained their targeting capability in biological fluid, displaying efficient binding to Streptactin-coated sepharose beads even when immersed in nearly undiluted serum and despite the relatively weak binding affinity (~ 1 μM) of Strep-tag to Streptactin.

At closer look, our data further revealed that AuGSHzwt@10st bound less efficiently to the Streptactin-coated beads than AuGSHzwt@1st following a 24 h incubation in FBS. This result was consistent with the apparently lower resistance of AuGSHzwt@10st against serum protein interactions as noted above. In addition, despite their multivalency, the AuGSHzwt@10st particles were likely too small to show avidity effects via interactions with multiple receptors on the surface of beads. The combined result was that saturating the surface of ultrasmall AuGSHzwt with Strep-tags was counterproductive. Similar conclusions might hold for other ultrasmall nanoparticle platforms and functional groups, with important implications for the design and use of active-targeting ultrasmall AuNPs in biomedicine.

Overall, ultrasmall AuGSHzwt constitutes an attractive platform for applications in vivo, wherein the particles’ strong “stealth” characteristics can be combined with desired molecular-recognition properties via the incorporation of functional peptides. Nevertheless, there is still much to be learned about the biointeractions of AuGSHzwt and other targeted ultrasmall AuNPs in complex media. For example, we need to understand in greater detail the issue of soft protein interactions with ultrasmall AuNPs, particularly at a quantitative level, and how this may influence nanoparticle performance in vivo.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Daniel Maturana for assistance with microscale thermophoresis, Dr. Guacyara da Motta for providing access to instrumentation, Dr. Maria Aronova and Dr. Richard D. Leapman for images of AuNPs, and the Spectroscopy and Calorimetry facility at Brazilian Biosciences National Laboratory (LNBio), CNPEM, Campinas, for their support with microscale thermophoresis. This work was supported by grant # 2019/04372-6, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, U.S.A.

Footnotes

Supporting information

UV-vis spectroscopy and gel electrophoresis characterization of gold nanoparticles in biological media; theoretical calculation of sedimentation coefficients of gold nanoparticles bound by increasing protein mass; mass-balance simulation model of nanoparticle-receptor complexation in protein-rich media. This Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c01444.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu J; Yu M; Zhou C; Yang S; Ning X; Zheng J Passive Tumor Targeting of Renal Clearable Luminescent Gold Nanoparticles: Long Tumor Retention and Fast Normal Tissue Clearance. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 4978–4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu M; Zheng J Clearance Pathways and Tumor Targeting of Imaging Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6655–6674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuber G; Weiss E; Chiper M Biocompatible Gold Nanoclusters: Synthetic Strategies and Biomedical Prospects. Nanotech. 2019, 30, 352001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X-D; Chen J; Luo Z; Wu D; Shen X; Song S-S; Sun Y-M; Liu P-X; Zhao J; Huo S Enhanced Tumor Accumulation of Sub-2 Nm Gold Nanoclusters for Cancer Radiation Therapy. Adv. Health. Mat 2013, 3, 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen F; Ma K; Madajewski B; Zhuang L; Zhang L; Rickert K; Marelli M; Yoo B; Turker MZ; Overholtzer M Ultrasmall Targeted Nanoparticles with Engineered Antibody Fragments for Imaging Detection of Her2-Overexpressing Breast Cancer. Nature Comm. 2018, 9, 4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao Y; Li M; Ren J; Qu X Metal Nanoclusters: Novel Probes for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44, 8636–8663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X-D; Yang J; Song S-S; Long W; Chen J; Shen X; Wang H; Sun Y-M; Liu P-X; Fan S Passing through the Renal Clearance Barrier: Toward Ultrasmall Sizes with Stable Ligands for Potential Clinical Applications. Int. J. Nanomed 2014, 9, 2069–2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang J; Wang F; Yuan H; Zhang L; Jiang Y; Zhang X; Liu C; Chai L; Li H; Stenzel M Recent Advances in Ultra-Small Fluorescent Au Nanoclusters toward Oncological Research. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 17967–17980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarschler K; Rocks L; Licciardello N; Boselli L; Polo E; Garcia KP; De Cola L; Stephan H; Dawson KA Ultrasmall Inorganic Nanoparticles: State-of-the-Art and Perspectives for Biomedical Applications. Nanomed. Nanotech. Biol. Med 2016, 12, 1663–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García KP; Zarschler K; Barbaro L; Barreto JA; O’Malley W; Spiccia L; Stephan H; Graham B Zwitterionic-Coated “Stealth” Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications: Recent Advances in Countering Biomolecular Corona Formation and Uptake by the Mononuclear Phagocyte System. Small 2014, 10, 2516–2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J; Yu M; Ning X; Zhou C; Yang S; Zheng J Pegylation and Zwitterionization: Pros and Cons in the Renal Clearance and Tumor Targeting of near-Ir-Emitting Gold Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 12572–12576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong Z; Shen M; Shi X Zwitterionic Modification of Nanomaterials for Improved Diagnosis of Cancer Cells. Bioconj. Chem 2019, 30, 2519–2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heuer-Jungemann A; Feliu N; Bakaimi I; Hamaly M; Alkilany A; Chakraborty I; Masood A; Casula MF; Kostopoulou A; Oh E The Role of Ligands in the Chemical Synthesis and Applications of Inorganic Nanoparticles. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 4819–4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boselli L; Polo E; Castagnola V; Dawson KA Regimes of Biomolecular Ultrasmall Nanoparticle Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 4215–4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashraf S; Park J; Bichelberger MA; Kantner K; Hartmann R; Maffre P; Said AH; Feliu N; Lee J; Lee D Zwitterionic Surface Coating of Quantum Dots Reduces Protein Adsorption and Cellular Uptake. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 17794–17800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizuhara T; Saha K; Moyano DF; Kim CS; Yan B; Kim YK; Rotello VM Acylsulfonamide-Functionalized Zwitterionic Gold Nanoparticles for Enhanced Cellular Uptake at Tumor Ph. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 6567–6570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Susumu K; Oh E; Delehanty JB; Blanco-Canosa JB; Johnson BJ; Jain V; Hervey IV WJ; Algar WR; Boeneman K; Dawson PE Multifunctional Compact Zwitterionic Ligands for Preparing Robust Biocompatible Semiconductor Quantum Dots and Gold Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 9480–9496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein J Probing the Interactions of Proteins and Nanoparticles. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2029–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lira AL; Ferreira RS; Torquato RJ; Zhao H; Oliva MLV; Hassan SA; Schuck P; Sousa AA Binding Kinetics of Ultrasmall Gold Nanoparticles with Proteins. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 3235–3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreira RS; Lira AL; Torquato RJ; Schuck P; Sousa AA Mechanistic Insights into Ultrasmall Gold Nanoparticle-Protein Interactions through Measurement of Binding Kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 28450–28459. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao Z; Jiang S Super-Hydrophilic Zwitterionic Poly (Carboxybetaine) and Amphiphilic Non-Ionic Poly (Ethylene Glycol) for Stealth Nanoparticles. Nano Today 2012, 7, 404–413. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao Q; Jiang S Molecular Understanding and Design of Zwitterionic Materials. Adv. Mat 2015, 27, 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang W; Zhang L; Wang S; White AD; Jiang S Functionalizable and Ultra Stable Nanoparticles Coated with Zwitterionic Poly (Carboxybetaine) in Undiluted Blood Serum. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5617–5621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X-D; Luo Z; Chen J; Song S; Yuan X; Shen X; Wang H; Sun Y; Gao K; Zhang L, et al. Ultrasmall Glutathione-Protected Gold Nanoclusters as Next Generation Radiotherapy Sensitizers with High Tumor Uptake and High Renal Clearance. Sci. Rep 2015, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang XD; Luo Z; Chen J; Shen X; Song S; Sun Y; Fan S; Fan F; Leong DT; Xie J Ultrasmall Au10− 12 (Sg) 10− 12 Nanomolecules for High Tumor Specificity and Cancer Radiotherapy. Adv. Mat 2014, 26, 4565–4568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sousa AA; Hassan SA; Knittel LL; Balbo A; Aronova MA; Brown PH; Schuck P; Leapman RD Biointeractions of Ultrasmall Glutathione-Coated Gold Nanoparticles: Effect of Small Size Variations. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 6577–6588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassan SA Computational Study of the Forces Driving Aggregation of Ultrasmall Nanoparticles in Biological Fluids. ACSNano 2017, 11, 4145–4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knittel LL; Schuck P; Ackerson CJ; Sousa AA Zwitterionic Glutathione Monoethyl Ester as a New Capping Ligand for Ultrasmall Gold Nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 46350–46355. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lévy R Peptide-Capped Gold Nanoparticles: Towards Artificial Proteins. ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 1141–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan Q; Wang Y; Zhao L; Liu R; Gao F; Gao L; Gao X Peptide Protected Gold Clusters: Chemical Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 12095–12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harkness KM; Turner BN; Agrawal AC; Zhang Y; McLean JA; Cliffel DE Biomimetic Monolayer-Protected Gold Nanoparticles for Immunorecognition. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 3843–3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desplancq D; Groysbeck N; Chiper M; Weiss E; Frisch B; Strub J-M; Cianferani S; Zafeiratos S; Moeglin E; Holy X Cytosolic Diffusion and Peptide-Assisted Nuclear Shuttling of Peptide-Substituted Circa 102 Gold Atom Nanoclusters in Living Cells. ACS Appl. Nano Mat 2018, 1, 4236–4246. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Travis AR; Liau VA; Agrawal AC; Cliffel DE Small Gold Nanoparticles Presenting Linear and Looped Cilengitide Analogues as Radiosensitizers of Cells Expressing A N B 3 Integrin. J. Nanopart. Res 2017, 19, 361. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao L; Daniels J; Moshnikova A; Kuznetsov S; Ahmed A; Engelman DM; Reshetnyak YK; Andreev OA Phlip Peptide Targets Nanogold Particles to Tumors. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 465–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang X.-w.; Wang J-Y; Li F; Song Z-J; Xie C; Lu W-Y Biochemical Characterization of the Binding of Cyclic Rgdyk to Hepatic Stellate Cells. Biochem. Pharm 2010, 80, 136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jha S; Ramadori F; Quarta S; Biasiolo A; Fabris E; Baldan P; Guarino G; Ruvoletto M; Villano G; Turato C Binding and Uptake into Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells of Peptide-Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles. Bioconj. Chem 2016, 28, 222–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang G; Jin X; Zhang S; Xing D Rgd Peptide-Modified Fluorescent Gold Nanoclusters as Highly Efficient Tumor-Targeted Radiotherapy Sensitizers. Biomaterials 2017, 144, 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo D; Wang X; Zeng S; Ramamurthy G; Burda C; Basilion JP Targeted Gold Nanocluster-Enhanced Radiotherapy of Prostate Cancer. Small 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pretze M; Hien A; Rä M; Schirrmacher R; Wängler C; Wängler B. r. Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor-and Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen-Specific Ultrasmall Gold Nanoparticles for Characterization and Diagnosis of Prostate Carcinoma Via Fluorescence Imaging. Bioconj. Chem 2018, 29, 1525–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X; He H; Wang Y; Wang J; Sun X; Xu H; Nau WM; Zhang X; Huang F Active Tumor-Targeting Luminescent Gold Clusters with Efficient Urinary Excretion. Chem. Comm 2016, 52, 9232–9235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin H-Q; Bi F-L; Gan F Rapid Synthesis of Cyclic Rgd Conjugated Gold Nanoclusters for Targeting and Fluorescence Imaging of Melanoma A375 Cells. Bioconj. Chem 2015, 26, 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vinluan RD III; Yu M; Gannaway M; Sullins J; Xu J; Zheng J Labeling Monomeric Insulin with Renal-Clearable Luminescent Gold Nanoparticles. Bioconj. Chem 2015, 26, 2435–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt TG; Skerra A The Strep-Tag System for One-Step Purification and High-Affinity Detection or Capturing of Proteins. Nat. Protocols 2007, 2, 1528–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skerra A; Schmidt TGM Applications of a Peptide Ligand for Streptavidin: The Strep-Tag. Biomol. Eng 1999, 16, 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heinecke CL; Ackerson CJ Preparation of Gold Nanocluster Bioconjugates for Electron Microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol 2013, 950, 293–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schuck P Sedimentation Velocity Analytical Ultracentrifugation: Discrete Species and Size-Distributions of Macromolecules and Particles; CRC Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schuck P; Zhao H; Brautigam CA; Ghirlando R Basic Principles of Analytical Ultracentrifugation; CRC Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Svedberg T; Nichols JB Determination of Size and Distribution of Size of Particle by Centrifugal Methods. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1923, 45, 2910–2917. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schuck P Size-Distribution Analysis of Macromolecules by Sedimentation Velocity Ultracentrifugation and Lamm Equation Modeling. Biophys. J 2000, 78, 1606–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shaltiel L; Shemesh A; Raviv U; Barenholz Y; Levi-Kalisman Y Synthesis and Characterization of Thiolate-Protected Gold Nanoparticles of Controlled Diameter. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sokołowska K; Malola S; Lahtinen M; Saarnio V; Permi P; Koskinen K; Jalasvuori M; Häkkinen H; Lehtovaara L; Lahtinen T Towards Controlled Synthesis of Water-Soluble Gold Nanoclusters: Synthesis and Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 2602–2612. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colangelo E; Comenge J; Paramelle D; Volk M; Chen Q; Levy R Characterizing Self-Assembled Monolayers on Gold Nanoparticles. Bioconj. Chem 2016, 28, 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lévy R; Wang Z; Duchesne L; Doty RC; Cooper AI; Brust M; Fernig DG A Generic Approach to Monofunctionalized Protein-Like Gold Nanoparticles Based on Immobilized Metal Ion Affinity Chromatography. ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 592–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hakem IF; Leech AM; Johnson JD; Donahue SJ; Walker JP; Bockstaller MR Understanding Ligand Distributions in Modified Particle and Particlelike Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 16593–16598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Åkesson A; Cárdenas M; Elia G; Monopoli MP; Dawson KA The Protein Corona of Dendrimers: Pamam Binds and Activates Complement Proteins in Human Plasma in a Generation Dependent Manner. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 11245–11248. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Casals E; Pfaller T; Duschl A; Oostingh GJ; Puntes V Time Evolution of the Nanoparticle Protein Corona. ACSNano 2010, 4, 3623–3632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng M; Huang X Nanoparticles Comprising a Mixed Monolayer for Specific Bindings with Biomolecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 12047–12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fried MG; Bromberg JL Factors That Affect the Stability of Protein-DNA Complexes During Gel Electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fried MG; Liu G Molecular Sequestration Stabilizes Cap–DNA Complexes During Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 5054–5059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sousa AA A Note on the Use of Steady–State Fluorescence Quenching to Quantify Nanoparticle–Protein Interactions. J. Fluoresc 2015, 25, 1567–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bekdemir A; Stellacci F A Centrifugation-Based Physicochemical Characterization Method for the Interaction between Proteins and Nanoparticles. Nat. Comm 2016, 7, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown PH; Balbo A; Schuck P Characterizing Protein-Protein Interactions by Sedimentation Velocity Analytical Ultracentrifugation. Current Protocols in Immunology 2008, 81, 18.15. 1–18.15. 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seidel SA; Dijkman PM; Lea WA; van den Bogaart G; Jerabek-Willemsen M; Lazic A; Joseph JS; Srinivasan P; Baaske P; Simeonov A Microscale Thermophoresis Quantifies Biomolecular Interactions under Previously Challenging Conditions. Methods 2013, 59, 301–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wienken CJ; Baaske P; Rothbauer U; Braun D; Duhr S Protein-Binding Assays in Biological Liquids Using Microscale Thermophoresis. Nature Comm. 2010, 1, 100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dai Q; Bertleff-Zieschang N; Braunger JA; Björnmalm M; Cortez-Jugo C; Caruso F Particle Targeting in Complex Biological Media. Adv. Health. Mat 2018, 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rodriguez-Quijada C; Sánchez-Purrà M; de Puig H; Hamad-Schifferli K Physical Properties of Biomolecules at the Nanomaterial Interface. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 2827–2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alkilany AM; Zhu L; Weller H; Mews A; Parak WJ; Barz M; Feliu N Ligand Density on Nanoparticles: A Parameter with Critical Impact on Nanomedicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2019, 143, 22–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mirshafiee V; Mahmoudi M; Lou K; Cheng J; Kraft ML Protein Corona Significantly Reduces Active Targeting Yield. Chem. Comm 2013, 49, 2557–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salvati A; Pitek AS; Monopoli MP; Prapainop K; Bombelli FB; Hristov DR; Kelly PM; Åberg C; Mahon E; Dawson KA Transferrin-Functionalized Nanoparticles Lose Their Targeting Capabilities When a Biomolecule Corona Adsorbs on the Surface. Nature Nanotech. 2013, 8, 137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Safavi-Sohi R; Maghari S; Raoufi M; Jalali SA; Hajipour MJ; Ghassempour A; Mahmoudi M Bypassing Protein Corona Issue on Active Targeting: Zwitterionic Coatings Dictate Specific Interactions of Targeting Moieties and Cell Receptors. ACS Appl. Mat. Int 2016, 8, 22808–22818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peters T Jr, All About Albumin: Biochemistry, Genetics, and Medical Applications; Academic press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sousa AA Impact of Soft Protein Interactions on the Excretion, Extent of Receptor Occupancy and Tumor Accumulation of Ultrasmall Metal Nanoparticles: A Compartmental Model Simulation. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 26927–26941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.