Abstract

Background:

Maxillofacial reconstruction with vascularized bone restores facial contour and provides structural support and a foundation for dental rehabilitation. Routine implant placement in such cases, however, remains uncommon. This study aims to determine dental implant survival in patients undergoing vascularized maxillary or mandibular reconstruction through a systematic review of the literature.

Methods:

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, the literature was queried for implant placement in reconstructed jaws using MeSH terms on PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane platforms. Weighted implant survivals were calculated for the entire cohort and sub-cohorts stratified by radiotherapy. Meta-analyses were performed to estimate effect of radiation on implant osseointegration.

Results:

Of 3,965 publications identified, 42 studies were reviewed, including 1,084 patients with 3,636 dental implants. Weighted implant survival was 92.2% at a median follow-up of 36 months. Survival was 97.0% in 269 implants placed immediately in 60 patients versus 89.9% in 1,897 delayed implants placed in 597 patients, with follow-up of 14 and 40 months, respectively. Dental implants without RT exposure had better survival than those exposed to radiation (95.3 vs. 84.6%; p<0.01) at median follow-up of 36 months. Meta-analyses showed radiation significantly increased the risk of implant failure (risk ratio [RR]: 4.74, p<0.01) and suggested that implants placed prior to radiotherapy trended towards better survival (88.9% vs. 83.4%, p=0.07, RR: 0.52; p=0.14).

Conclusions:

Overall implant survival was 92.2%; however, radiotherapy adversely impacted outcomes. Implants placed before radiation may demonstrate superior survival than implants placed after.

Keywords: Mandible reconstruction, maxilla reconstruction, dental implants, osteocutaneous flaps, free fibula flaps, implant survival

INTRODUCTION

Dental rehabilitation through osseointegrated implant placement significantly improves quality of life (QoL) (1–4) by restoring maxillofacial functions, including mastication and speech. In recent decades, osseointegrated dental implants have become the mainstay for their potential to restore dental continuity in a single procedure(5). Osseointegrated implant placement can be immediate or delayed, followed by delivery of implant-supported/retained prosthetic teeth. Immediate implantation has advantages, such as better access to the bone, ease of determining the interdental relationship, and shorter time to complete dental rehabilitation6. However, implant placement is more commonly performed as a secondary, delayed procedure to avoid damaging the bone flap and to allow for a healed, stable substrate. Existing studies demonstrate disparate approaches to implant placement with variable results, underscoring the need for a systematic, rigorous review to summarize the findings.

In oncology, osseointegrated implant placement in the context of radiotherapy (RT) is an additional concern. RT adverse events include hot spots and osteoradionecrosis; however, radiation’s impact on osseointegrated implant survival is unclear. While some surgeons suggest unchanged implant survival in native bone versus irradiated flaps in head and neck (H/N) cancer patients7, others demonstrate lower implant survival rates8. There is also a lack of evidence regarding implant placement success, before or after RT, in the reconstructed maxilla and mandible.

This study aims to provide an exhaustive summary of existing evidence regarding immediate or delayed osseointegrated dental implant survival in vascularized bone flaps for maxillary and mandibular reconstruction. Furthermore, this study seeks to better understand whether implant placement before or after RT impacts implant survival. Lastly, this study reviews the patient-reported outcomes following vascularized bone flap and dental implant placement.

METHODS

Search Methodology for Studies

A comprehensive electronic literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines9, 10. The study was exempted from institutional board review. PubMed, Embase via the Elsevier platform, and Cochrane provided by Wiley Online Library were queried for articles published in English from 1992–2017 using MeSH terms for maxillary and mandibular resection followed by reconstruction with a vascularized free flap and dental implantation. Keywords and subject headings were searched using Boolean operators (AND, OR). Related terms were also incorporated to ensure relevant papers were retrieved. A manual search of references was performed to find relevant articles not detected in the electronic bibliographic search.

Selection Process

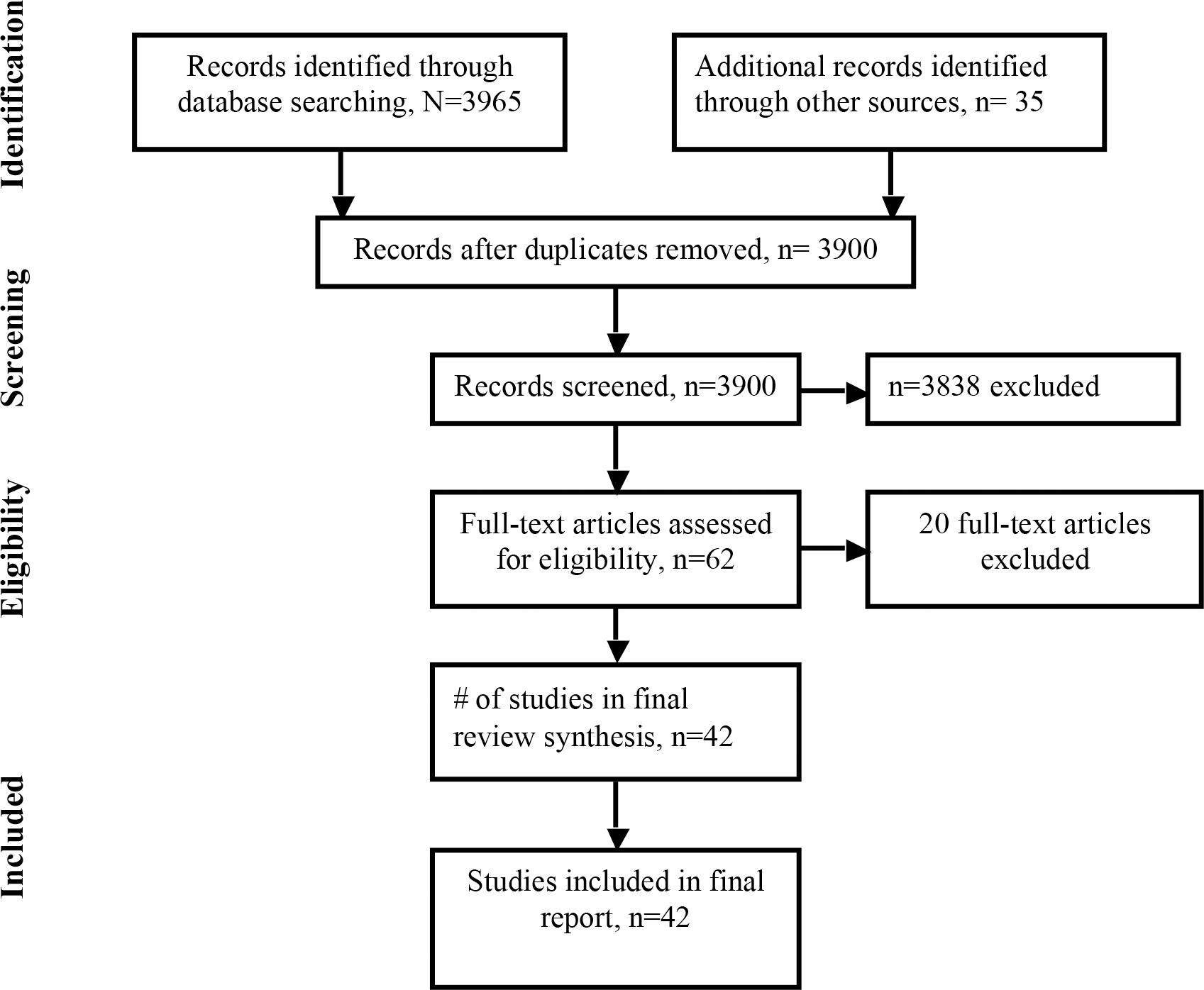

Results of the search were imported into an EndNote database. Publications were screened where two investigators (HP, IP) independently reviewed titles and abstracts for duplicates and poor fit within the focus of the systematic review. If at least one reviewer coded the title to continue to the next round, the other investigator independently reviewed the full text article and classify the articles based on the eligibility criteria. Both investigators independently assessed all articles deemed eligible for full-text review. Discrepancies were discussed with a third investigator (JAN) until consensus was reached. In case of multiple articles by the same author(s), assessment of the most recent article was done to avoid duplication of the cases (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Patient selection for the systematic review

Inclusion criteria comprised studies involving segmental resection of the maxilla or mandible followed by reconstruction using bone flap(s) or composite flaps—osteocutaneous, osteomyocutaneous, or osteoseptomyocutaneous—implanted with the dental fixture(s). Studies involving single case reports, non-human subjects, and inadequate information about implant survival were excluded. Patients who experienced flap failure or morbidity and mortality due to recurrent malignancy were excluded from analysis.

Study Design

The primary outcome was implant survival at last available follow-up in the overall cohort of all selected studies. The secondary outcomes were weighted implant survival based on RT status (i.e., radiation vs. no radiation) and its timing (i.e., radiation before or after implant placement).

Implant survival was defined as in situ, immobile, or stable on clinical exam, free of complications such as infection, inflammation and suppurations, mobility, discomfort, ongoing pathological process, peri-implantitis, neuropathies, persistent paraesthesia, peri-implant radiolucency, or significant peri-implant bone absorption.

Data Extraction

Demographics and clinical information (age, sex, indications for surgery, defect location, flap type, reconstruction location, implant placement, survival) were manually extracted and summarized. Implant-related variables included total implants in the flaps, timing of implantation, average follow-up time after implant placement, and implant survival.

Statistical Analysis

The quality of non-randomized studies was assessed using the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS)11. The average number of implants per patient was calculated (total number of patients who received implants from the total number of implants placed in the flaps). Weighted implant survival was calculated for the entire cohort and for sub-cohorts stratified by no radiation, pre-RT, and post-RT.

Weighted average survival (x) was calculated as the sum of the product of total implants (weight, wi) times the survival (xi) for each study, divided by the sum of the weights. Chi-square statistics were used to analyze differences in implant survival. All tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was used to determine significance. All other analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY)

Meta-analysis and forest plots were generated for studies with sufficient data for both intervention (total implant placed) and outcome (implant failure/osseointegration). A random or fixed model meta-analysis was performed to compare risk of implant failure in irradiated versus non-irradiated flaps. Outcomes were reported as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence interval. Heterogeneity across the studies was assessed using Q statistic, and p=0.1 was considered significant. The I2 statistic was used to quantify heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using sequential study omission to explore potential explanation of heterogeneity and impact on the overall results. Publication bias was investigated by exploring funnel plots where appropriate. All analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, version 3 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ).

RESULTS

Of 3965 records identified, 42 studies published from 1992–2017 were included (Figure 1)(6–47). Studies included one randomized controlled trial, six prospective cohorts, and 35 retrospective cohort studies or case series (Table 1). The MINORS value ranged from 56%–94%.

Table 1:

Summary of Included Studies and Their Cohorts’ Characteristics

| Study | Time of Surgery | Study Design | Total No. of Patients with Flap(s) | Average Age, years (min–max) | Sex |

Proportion of Malignant Cases | Defect Location: Mandible/Maxilla/Both | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Zlotolow et al., 1992 | 1990–1992 | Case series | 7 | 45 (17–65) | 4 | 3 | Mixed | Mandible |

| Sclaroff et al., 1994 | 1991–1994 | Retrospective cohort | 22 | 54 (29–79) | 16 | 6 | Majority malignant | Mandible |

| Barber et al., 1995 | nr | Prospective pilot | 5 | nr | nr | nr | All malignant | Mandible |

| Roumanas et al., 1997 | nr | Retrospective cohort | 20 | (25–78) | 10 | 10 | Majority malignant | Mandible |

| Gürlek et al., 1998 | 1988–1994 | Retrospective cohort | 20 | 47 (27–74) | 9 | 11 | Majority malignant | Mandible |

| Chang et al., 1998 | 1994–1997 | Prospective study | 12 | 36 (17–65) | 5 | 7 | None | Mandible |

| Foster et al., 1999 | 1985–1996 | Retrospective cohort | 75 | 49 (12–82) | 47 | 28 | Majority malignant | Mandible |

| Schliephake et al., 1999 | 1988–1994 | Retrospective cohort | 44 | nr | 32 | 12 | All malignant | Mandible |

| Kovacs et al., 2000 | 1991–1998 | Retrospective cohort | 11 | nr | nr | nr | Mixed | Mandible |

| Shaw et al., 2005 | 1987–2002 | Retrospective cohort | 81 | 58 (15–80) | 49 | 32 | All malignant | Both |

| Teoh et al., 2005 | 1986–2001 | Retrospective cohort | 24 | 42 (7–81) | 10 | 14 | Majority malignant | Mandible |

| Kramer et al., 2005 | 1998–2001 | Prospective study | 16 | 47 (20–71) | 13 | 24 | Majority malignant | Both |

| Garrett et al., 2006 | 1997–2001 | Prospective study | 46 | 60 (19–83) | 22 | 24 | Majority malignant | Mandible |

| Gbara et al., 2007 | 1992–1994 | Retrospective cohort | 30 | 61 (36–75) | 18 | 12 | Majority malignant | Mandible |

| Smolka et al., 2008 | 1992–2000 | Retrospective cohort | 56 | 56 (41–79) | 43 | 13 | All malignant | Mandible |

| Hundepool et al., 2008 | 1995–2005 | Retrospective cohort | 70 | 53 (6–82) | 40 | 30 | All malignant | Both |

| Raoul et al., 2009 | 1996–2007 | Retrospective cohort | 30 | 46 (19–72) | 18 | 12 | Majority malignant | Both |

| Virgin et al., 2010 | 2001–2008 | Retrospective cohort | 168 | 60 (nr) | 111 | 57 | All malignant | Mandible |

| Salinas et al., 2010 | 1994–2002 | Retrospective cohort | 44 | nr | 25 | 19 | Majority malignant | Mandible |

| Bodard et al., 2011 | nr | Retrospective cohort | 23 | 46 (17–66) | 17 | 6 | nr | Mandible |

| Barrowman et al., 2011 | 1992–2007 | Retrospective cohort | 31 | 51 (20–76) | 18 | 13 | All malignant | Both |

| Buddula et al., 2011 | 1987–2008 | Retrospective cohort | 48 | 61 (33–92) | 29 | 19 | All malignant | Both |

| Chang et al., 2011 | 2005–2007 | Retrospective cohort | 10 | 41 (23–65) | 7 | 3 | None | Mandible |

| Dholam et al., 2011 | nr | Retrospective cohort | 12 | nr | nr | nr | All malignant | Both |

| Fenlon et al., 2012 | nr | Prospective study | 41 | nr | nr | nr | nr | Both |

| Meloni et al., 2012 | 2009–2014 | Prospective study | 10 | 52 (nr) | 6 | 4 | Mixed | Both |

| Fierz et al., 2013 | 2004–2007 | Retrospective cohort | 46 | 54 | 31 | 15 | All malignant | Both |

| Ferrari et al., 2013 | 1998–2008 | Retrospective cohort | 14 | 50 (15–63) | 8 | 6 | Mixed | Mandible |

| Qu et al., 2013 | 2006–2010 | Retrospective cohort | 33 | 38 (19–66) | 20 | 13 | None | Mandible |

| Jacobsen et al., 2014 | 1997–2005 | Retrospective cohort | 33 | 52 (20–69) | 17 | 16 | Majority malignant | Mandible |

| Wang et al., 2015 | 2006–2008 | Retrospective cohort | 19 | 40 (28–55) | 12 | 7 | None | Mandible |

| Bodard et al., 2015 | nr | Retrospective cohort | 26 | 54 (19–72) | 17 | 9 | nr | Mandible |

| Hakim et al., 2015 | 1993–2012 | Retrospective cohort | 198 | 52 (nr) | nr | nr | Majority malignant | Both |

| Fang et al., 2015 | nr | Retrospective cohort | 74 | 47 (19–75) | nr | nr | All malignant | Mandible |

| Burgess et al., 2017 | 2009–2015 | Retrospective cohort | 59 | 51 (18–77) | 35 | 24 | All malignant | Both |

| Barber et al., 2016 | 2001–2009 | Retrospective cohort | 114 | 54 (nr) | 64 | 50 | All malignant | Both |

| Ch’ng et al., 2016 | 2005–2011 | Retrospective cohort | 246 | nr | nr | nr | All malignant | Both |

| Kumar et al., 2016 | 2012–2014 | Randomized controlled trial | 33 | 40 (nr) | 26 | 8 | Mixed | Mandible |

| Jackson et al., 2016 | 2005–2014 | Retrospective cohort | 46 | 62 (17–80) | 31 | 15 | Majority malignant | Mandible |

| Wu et al., 2016 | 2004–2011 | Retrospective cohort | 36 | 52 (nr) | 25 | 11 | All Malignant | Both |

| Burgess et al., 2017 | 2009–2015 | Retrospective cohort | 59 | 51 (18–77) | 35 | 24 | All malignant | Both |

| Sozzi et al., 2017 | 1998–2012 | Retrospective cohort | 22 | nr (12–70) | 12 | 10 | Mixed | Both |

| Kniha et al., 2017 | nr | Retrospective cohort | 28 | 58 (nr) | 15 | 13 | Majority malignant | Both |

nr, not reported; M, male; F, female, Majority malignant

Patient Population and Flap Details

Among the 42 studies, a total of 2042 patients underwent vascularized bone reconstruction following segmental resection of maxilla, mandible, or both; median age was 54 years (range: 6–92; Table 1). Among studies reporting patient’s sex, 61% were male (n=897) and 39% were female (n=580).

Twenty-nine studies included over 50% of patients with oncologic reconstructions, with 14 exclusively examining this population. Four studies included patients exclusively with reconstruction for benign disease(13–16) The majority of the studies included patients with mandibular reconstruction. Twenty-six studies utilized the free fibula flap (FFF) for reconstruction (Table 2). Over one-third of the study groups also used other donor sites, including the iliac crest (n=14)(6–8, 14, 17–26), scapula (n=5)(8, 19, 22, 25, 27), and radial artery free flaps (RAFF; n=4)(25–28).

Table 2:

Implant Survival in Patients Who Underwent Dental Rehabilitation with Microvascular Flaps

| Study | Flap Type(s) | No. of Pts. with Implants in Flap(s) | Total No. of Implants in Flap(s) | Average No. of Implants in Flap(s) per Pt. | Average or median Follow-up, months | Median Implant Survival, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Zlotolow et al., 1992 | FFF | 7 | 23 | 3.3 | 13 | 100.0 |

| Sclaroff et al., 1994 | FFF, DCIA | 22 | 114 | 5.2 | 18 | 88.0 |

| Barber et al., 1995 | FFF | 5 | 20 | 4.0 | 14 | 100 |

| Roumanas et al., 1997 | FFF | 19 | 54 | 2.8 | 26 | 98.1 |

| Gürlek et al., 1998 | FFF, DCIA | 20 | 60 | 3.0 | 47 | 91.7 |

| Chang et al., 1998 | FFF | 8 | 34 | 4.3 | 14 | 100.0 |

| Foster et al., 1999 | FFF, DCIA | 14 | 71 | 5.1 | 18 | 99.0 |

| Schliephake et al., 1999 | FFF, DCIA, SFF | 21 | 83 | 4.0 | 36 | 100.0 |

| Kovacs et al., 2000 | DCIA | 11 | 41 | 3.7 | 48 | 97.6 |

| Shaw et al., 2005 | FFF, DCIA, RAFF | 35 | 126 | 3.6 | 48 | 73.9 |

| Teoh et al., 2005 | FFF | 24 | 81 | 3.4 | 52 | 94.0 |

| Kramer et al., 2005 | FFF, DCIA | 16 | 51 | 3.2 | 24 | 96.0 |

| Garrett et al., 2006 | FFF | 17 | 58 | 3.4 | 20 | 94.8 |

| Gbara et al., 2007 | FFF | 30 | 121 | 4.0 | 12 | 96.7 |

| Smolka et al., 2008 | FFF | 30 | 108 | 3.6 | 50 | 92.0 |

| Hundepool et al., 2008 | FFF | 18 | 69 | 3.8 | 18 | 97.0 |

| Raoul et al., 2009 | FFF | 30 | 105 | 3.5 | 76 | 96.2 |

| Virgin et al., 2010 | FFF, RAFF | 4 | 18 | 4.5 | 27 | 100.0 |

| Salinas et al., 2010 | FFF | 44 | 114 | 2.6 | 41 | 82.4 |

| Bodard et al., 2011 | FFF | 23 | 75 | 3.3 | 28 | 80.0 |

| Barrowman et al., 2011 | FFF, DCIA, SFF | 31 | 32 | 1.0 | 18 | 95.7 |

| Buddula et al., 2011 | FFF, DCIA, SFF | 48 | 59 | 1.2 | 36 | 90.2 |

| Chang et al., 2011 | FFF | 10 | 25 | 2.5 | 39 | 100.0 |

| Dholam et al., 2011 | FFF | 12 | 35 | 2.9 | 18 | 71.2 |

| Fenlon et al., 2012 | FFF, DCIA | 41 | 145 | 3.5 | 36 | 87.6 |

| Meloni et al., 2012 | FFF | 10 | 51 | 5.1 | 48 | 94.6 |

| Fierz et al., 2013 | FFF, RAFF, SFF | 22 | 46 | 2.1 | 54 | 82.6 |

| Ferrari et al., 2013 | FFF | 14 | 57 | 4.1 | 71 | 91.9 |

| Qu et al., 2013 | DCIA | 25 | 81 | 3.2 | 26 | 100.0 |

| Jacobsen et al., 2014 | FFF | 23 | 99 | 4.3 | 67 | 81.0 |

| Wang et al., 2015 | FFF | 19 | 51 | 2.7 | 36 | 100.0 |

| Bodard et al., 2015 | FFF | 26 | 80 | 3.1 | 72 | 97.5 |

| Hakim et al., 2015 | FFF | 37 | 119 | 3.2 | 85 | 91.6 |

| Fang et al., 2015 | FFF | 74 | 192 | 2.6 | 60 | 90.1 |

| Barber et al., 2016 | FFF, DCIA | 30 | 82 | 2.7 | 36 | 87.8 |

| Ch’ng et al., 2016 | FFF | 54 | 243 | 4.5 | 37 | 92.8 |

| Kumar et al., 2016 | FFF | 33 | 104 | 3.2 | 12 | 99.0 |

| Jackson et al., 2016 | FFF | 46 | 183 | 4.0 | 30 | 93.4 |

| Wu et al. 2016 | FFF, DCIA | 22 | 126 | 5.7 | 120 | 93.2 |

| Burgess et al., 2017 | FFF, DCIA, RAFF, SFF | 59 | 199 | 3.4 | 24 | 93.6 |

| Sozzi et al., 2017 | FFF | 22 | 92 | 4.2 | 94 | 98.0 |

| Kniha et al., 2017 | FFF, DCIA | 28 | 109 | 3.9 | 36 | 100.0 |

FFF, free fibula flap; BIFF, bone-impacted fibula free flap; DCIA, deep circumflex iliac artery; RAFF, radial artery free flap; SFF, scapula free flap

Thirteen studies reported additional procedures aimed to enhance bone height/quality or soft tissue management techniques(7, 11, 16, 21, 28–36). These included double-barrel fibula, vertical distraction osteogenesis, bone grafting, bone-impacted FFF, or sub-periosteal dissection with denture-guided epithelial regeneration.

Implant Placement for Dental Rehabilitation

Among 2042 patients with free-flap–based reconstruction, 53% (n=1084) underwent dental rehabilitation with 3636 total implants (Table 2). Implant types are described in Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which demonstrates types of implants used in each study. Most studies (85.7%) included patients with reconstructions following oncologic resections before or after RT; 14.3% studied patients with benign H/N lesions.

Implant Survival Outcomes

Implant survival, entire cohort

Among 1084 patients with implants, the overall median implant survival was 94.7% and weighted survival was 92.2%, with median follow-up of 36 months (Table 2).

Immediate versus delayed implant placement

Twelve studies reported on 151 patients who received 582 implants at initial flap reconstruction (immediate implant placement)(9, 11, 14, 15, 18, 19, 23, 31, 35, 37–39). However, due to limited data regarding implant success, a meta-analysis comparing success rates of immediate versus delayed placement was not possible. Only four studies(8, 13, 15, 39) reported on osseointegration outcome for implants in patients who underwent immediate placement (total patients, n=60; total implants, n=269; see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which demonstrates survival outcomes in patients with immediate implant placement). Weighted survival was 97.0%, with median follow-up of 14 months.

Twenty-three studies(13, 7–9, 16, 17, 20, 21, 25–27, 29, 30, 36, 39–45) reported on implant survival in 597 patients with delayed implant placement (n=1897 implants). Weighted implant survival was 89.9% at a median follow-up of 40 months (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which demonstrates survival outcomes in patients with delayed implant placement).

Impact of radiation on implant survival

Nine studies reported on implant survival in non-irradiated flaps in over 118 patients with 827 implants(6, 23, 35, 38–40, 43, 46, 47) Weighted survival was 94.9% at a median follow-up of 36 months (Table 3). Among RT patients, implant survival was lower than in non-RT patients (proportion of successful implants: 633/748 vs. 788/827; survival rate: 84.6% vs. 95.3%; p<0.01; Tables 3–5).

Table 3:

Survival Outcome in the No Radiation (Control) Implant Placement Group

| Study | No. of Patients | No. of Implants | No. of Implants Failed | Average or Median Follow-up, months | Median Implant Survival, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Sclaroff et al., 1994 | 6 | 34 | 2 | 18 | 94.1 |

| Teoh et al., 2005 | 17 | 56 | 0 | 17 | 100.0 |

| Gbara et al., 2007 | 18 | 72 | 0 | 12 | 100.0 |

| Salinas et al., 2010 | nr | 63 | 6 | 41 | 90.5 |

| Fenlon et al., 2012 | 29 | 110 | 3 | 36 | 97.3 |

| Jacobsen et al., 2014 | nr | 86 | 9 | 64 | 89.5 |

| Ch’ng et al., 2016 | 32 | 177 | 9 | 37 | 94.9 |

| Jackson et al., 2016 | nr | 156 | 9 | 30 | 94.2 |

| Sozzi et al., 2017 | 16 | 73 | 1 | 94 | 98.6 |

|

| |||||

| Total | >118 | 827 | 39 | 36 (12–94) * | 95.3 ** |

nr, not reported

Median follow-up

Weighted Survival

Table 5:

Survival Outcomes in the Post-irradiation Implant Placement Group

| Study | Total No. of Patients | Total No. of Implants | No. of Failed Implants | Average or Median Follow-up, months | Implant Survival, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Barber HD et al., 1995 a | 5 | 20 | 0 | 14 | 100.0 |

| Foster et al., 1999 b | 3 | 15 | 0 | 18 | 100.0 |

| Shaw et al., 2005 b | 12 | 45 | 15 | 48 | 66.7 |

| Teoh et al. 2005 a | 6 | 25 | 5 | 13 | 80.0 |

| Raoul et al., 2009 b | 6 | 18 | 1 | 90 | 94.4 |

| Salinas et al., 2010 a | 22 | 51 | 14 | 41 | 72.6 |

| Bodard et al., 2011 b | 5 | 13 | 3 | 81 | 76.9 |

| Barrowman et al., 2011 a | nr | 15 | 5 | 18 | 66.7 |

| Buddula et al., 2011 b | 48 | 59 | 8 | 36 | 86.4 |

| Jacobsen et al., 2014 b | 3 | 13 | 8 | 67 | 38.5 |

| Fierz et al., 2013 b | 12 | 20 | 6 | 54 | 70.0 |

| Ch’ng et al., 2016 b | nr | 43 | 8 | 37 | 81.4 |

| Hakim et al., 2015 b | 16 | 48 | 5 | 85 | 89.6 |

| Kumar et al., 2016 b | 8 | 24 | 2 | 12 | 91.7 |

| Jackson et al., 2016 b | 19 | 26 | 5 | 30 | 80.8 |

| Wu et al., 2016 | 22 | 126 | 9 | 120 | 93.2 |

| Sozzi et al., 2017 b | 5 | 8 | 1 | 94 | 87.5 |

|

| |||||

| Summary statistics | >192 | 569 | 95 | 41 (12–120) * | 83.4 ** |

nr, not reported

Hyperbaric oxygen was given before and or after radiotherapy.

No information reported about the receipt of hyperbaric oxygen.

Median follow-up

Weighted Survival

Impact of radiation timing on implant survival

Six studies included over 38 patients who received 179 implants before RT(6, 23, 35, 38–40) At a median follow-up of 24 months, 20 implants failed, resulting in an overall weighted implant survival of 88.8% (Table 4).

Table 4:

Survival Outcome in the Pre-irradiation Implant Placement Group

| Study | Total No. Patients | Total No. of Implants | No. of Implants Failed | Average or Median Follow-up, months | Implant Survival, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Sclaroff et al., 1994 a | 16 | 80 | 0 | 18 | 100.0 |

| Teoh et al., 2005 a | 1 | 5 | 0 | 15 | 100.0 |

| Fenlon et al., 2012 b | 12 | 35 | 15 | 36 | 57.1 |

| Ch’ng et al., 2016 b | nr | 23 | 3 | 37 | 87.0 |

| Jackson et al., 2016 b | 8 | 25 | 2 | 30 | 92.0 |

| Sozzi et al., 2017 b | 1 | 11 | 0 | 18 | 100.0 |

|

| |||||

| Summary statistics | >38 | 179 | 20 | 24 (15–37) * | 88.8 ** |

nr, not reported

No one received hyperbaric oxygen.

No information reported about the receipt of hyperbaric oxygen.

Median follow-up

Weighted Survival

Seventeen studies included over 192 RT patients with secondary, delayed implant placement (n=569)(12, 8, 10, 18, 22, 26, 27, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38–40, 42, 43, 47). Of those, 95 implants failed at a median follow-up of 41 months. Overall weighted implant survival was 83.4% (Table 5).

Comparing weighted implant survival among the irradiated groups, implant survival tended to be superior among the patients who received RT following implant placement than among those who received RT before implant placement (88.8% vs. 83.4%; p=0.07).

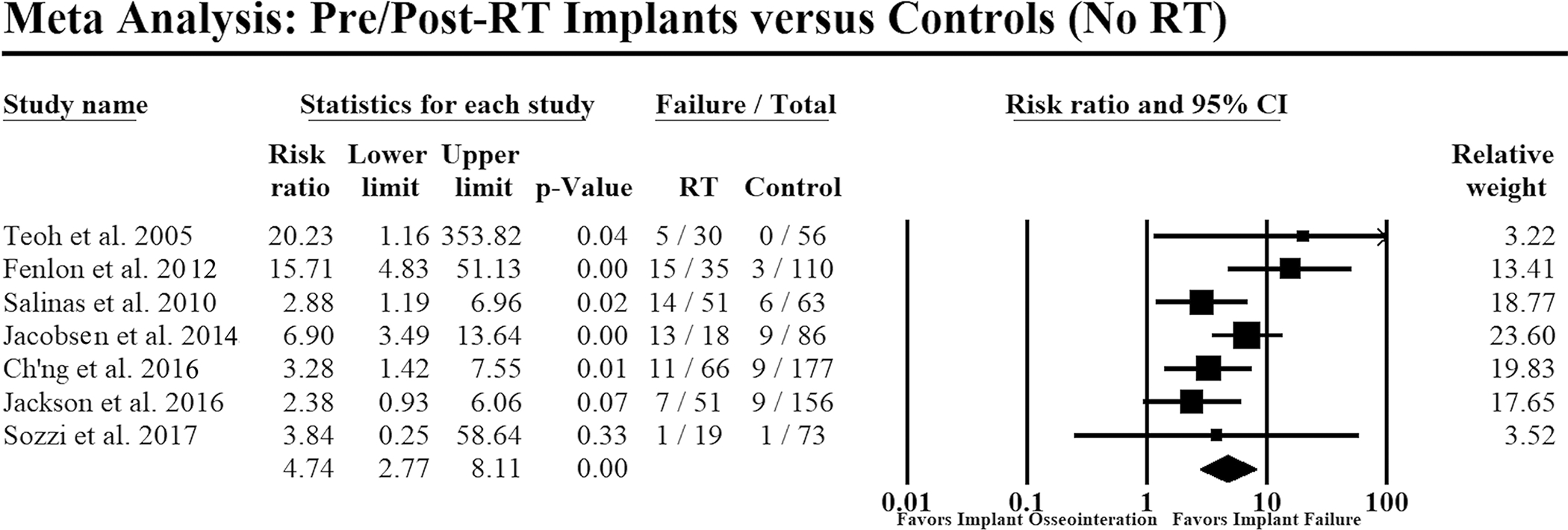

Meta-analysis

A pooled analysis of seven studies(23, 35, 38–40, 43, 47) that included 270 implants placed before or after RT in 77+ patients versus 721 implants in 95+ control patients revealed that RT significantly increased the risk of implant failure (RR=4.74; p<0.01), regardless of timing, when compared with controls (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Forest plot comparing implant failure in patients with implant placement before or after radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy (i.e., controls). Events: Failure=implant failure; RT=radiotherapy. Heterogeneity: Q=10.2, p=0.12; I-square=41%; Tau-square=0.20. Overall effect: Z=5.68, risk ratio= 4.74, p<0.01. Random-effects model was used to conduct the meta-analysis. Size of each data marker corresponds to the weight of the study assigned by the model.

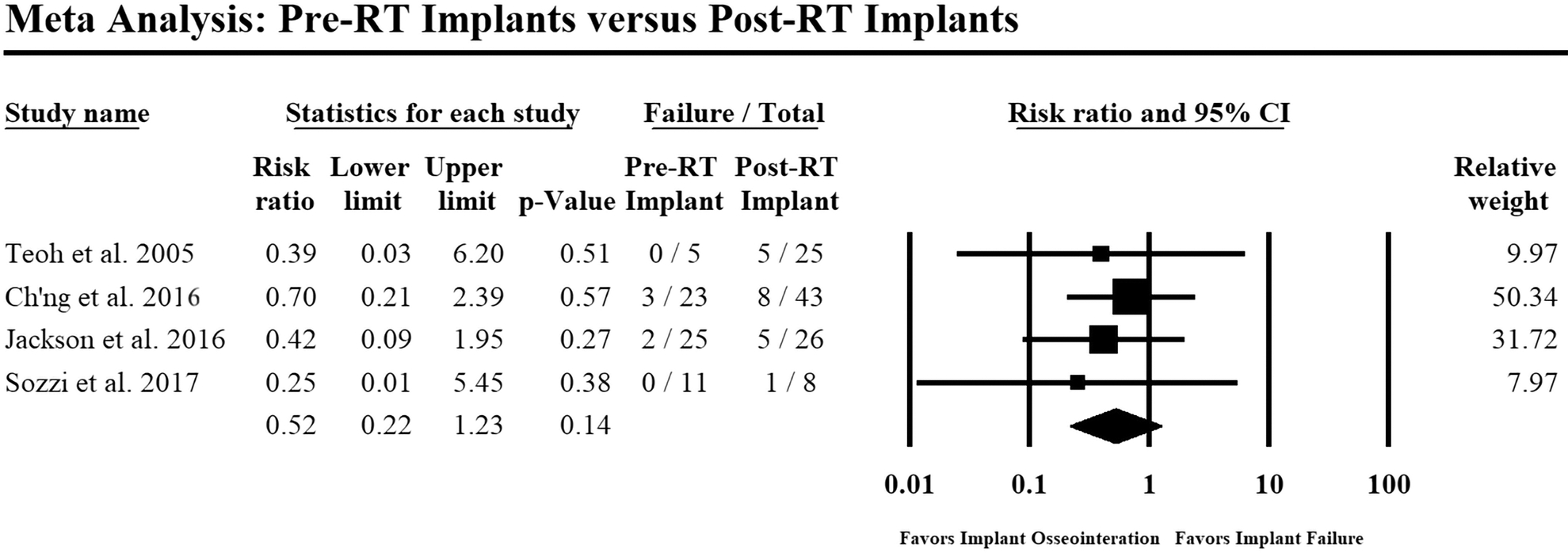

To study RT timing’s impact on implant survival, an analysis of four studies(35, 38–40) compared 64 implants placed before RT in 10+ patients versus 102 implants placed after RT in 30+ patients. Implants in the former cohort had a reduced risk of failure, though this was not statistically significant (RR: 0.52; p=0.14; Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Forest plot comparing implant failure in patients who underwent pre-RT implant placement versus post-RT implant placement. Events: Failure=implant failure; RT=radiotherapy. Heterogeneity: Q=0.56, p=0.91; I-square=0%; Tau-square=0.00. Overall effect: Z= −1.49, risk ratio=0.52, p=0.14. Random-effects model was used to conduct the meta-analysis. Size of each data marker corresponds to the relative weight of the study assigned by the model.

QoL analysis

Ten studies reported QoL outcomes after reconstruction(9, 17, 28–31, 41, 42, 44, 45). Three used standardized measurement tools: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ30)(44) and its H/N module (EORTC-QLQ H&N35)(9, 44), and Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14)(30) None of the studies used overlapping methodology precluding direct comparisons. Nonetheless, these studies generally reported improvement in aesthetic and social aspects as well as function with dental implant placement.

DISCUSSION

Even though vascularized bone flaps begin the restoration of orofacial form and function(48, 49), reconstruction is incomplete until viable dentition is restored. In this systematic review, osseointegrated dental implants in vascularized flaps demonstrated a weighted survival of 92.2% at an average follow-up of about three years. Immediate implant placement had superior survival (97.0%), compared with delayed placement (89.9%), with a median follow-up of 14 and 40 months, respectively. Advanced technology in virtual surgical planning (i.e. computer-aided design and manufacturing), may facilitate immediate dental implant placement, allow for accurate positioning, all while accelerating dental restoration(5, 50). If implants are not placed during flap reconstruction, many oncologic patients may not undergo future dental restoration, regardless of the need for RT. Lastly, from a cost perspective, payment for implant placement may be bundled with the initial reconstruction, reducing the overall cost compared with the delayed procedure, often billed as an out-of-pocket expense. Overall, immediate dental implant placement is a feasible technique that can lead to better outcomes and may be more cost effective. Given the challenges of oncologic resection, reconstruction and subsequent treatment, this systematic review presents the literature foundation for immediate dental implant placement at the time of initial reconstruction, with virtual planning and protocols to enable early dental restoration even in the setting of RT(50).

Among RT patients, the implant survival rate was lower than for no-RT patients (84.6% vs. 95.3%, p<0.01). The meta-analysis strengthened this finding, demonstrating a significantly greater risk of implant failure in patients with RT after implant placement or in patients with implants placed in an irradiated flap (RR: 4.74; p<0.01; Figure 2). Radiation may cause peri-implant soft tissue inflammation, potentially impairing osseointegration of the implants by either directly jeopardizing bone vascularity or indirectly creating peri-implant pseudo heat pockets resulting from backscatter exposure, all of which impedes osteoinduction(9, 36, 46). Although it is not surprising that implant survival in non-irradiated flaps is superior to that in irradiated flaps, the debate has shifted to focus on timing of implant placement with respect to RT delivery(19, 51)

In this systematic review, RT stratified analysis revealed a superior survival for implants placed before RT versus those placed after although this was not statistically significant (p=0.07), possibly due to lack of power. The meta-analysis comparing risk of implant failure between pre-RT and post-RT patients showed a similar trend (RR=0.52; p=0.14). Implant placement before RT allows for osseointegration promoted by maximum flap vascularity but includes the potential development of hot spots that cause local bone erosion. On the other hand, insufficient vascularity may impair osseointegration in post-RT implant placement. In the latter scenario, some authors suggest implant placement 12 months after RT, which may allow for improved bone perfusion and implant survival(52, 53). This is supported in part by physiological studies that demonstrate a continuous loss of capillaries for up to 6 months post-RT(54) and over 70% reduction in bone regeneration immediately after RT, with a recovery towards baseline at 1-year(47). It is noteworthy in this review, patients waited 6–12 months after RT for secondary implant placement. However, the impact of absent dentition for such a protracted period likely has functional and health-related QoL impact. The difference in the follow-up time between the RT cohorts should be noted—patients with the implants placed before RT had shorter follow-ups, a bias that naturally favors survival in this cohort. Several studies also presented patients treated with hyperbaric oxygen exposure during RT did yet did not demonstrate any significant unidirectional pattern in the implant survival or treatment benefit(12, 22, 26, 43).

Ch’ng et al in 2016 presented a comprehensive study with a global examination of implant placement in head and neck reconstruction(38). This study found progressive implant loss as time increased and demonstrated that most implants lost in the native mandible and maxilla typically occurred in the first 36 months. Conversely, implants placed in FFF had increased loss beyond 60 months, with survival analysis demonstrating only a 40% survival beyond the 72-month timepoint. This finding may be due to survival bias – a type of selection bias that selects on those that have survived past a certain point (in this case 60 months). Osteoradionecrosis, as a late process occurring following RT, can certainly play a role in late losses in general. The authors discuss loss of all implants in a patient with a FFF and osteoradionecrosis. Continued examination of long-term outcomes is needed to better understand this implant survival process(38).

Few studies reported functional and QoL measures using a validated standardized questionnaire(9, 30, 41, 44). Therefore, it is important to properly assess post-rehabilitation oral functions, which play a crucial role in health-related QoL(1) Gürlek et al. used a subjective questionnaire and found that 75% of patients reported excellent cosmetic outcomes and were able to return to work, be socially active, eat a regular diet with minimal restriction in public, and have normal speech(17). Dholam at al. used the EORTC QLQ-H&N35(44), one of the most commonly used questionnaires to assess QoL in patients undergoing treatment for H/N cancer. Fang et al. used OHIP-14, a questionnaire evaluating oral dysfunction-related QoL following surgery, where most patients reported no problems with their oral health at 1-year follow-up(30). These results highlight the limited utilization of validated patient-reported outcome measures for patients undergoing reconstruction following mandibular or maxillary defects and necessitates further research(55) Recently, the FACE-Q patient-reported outcome measure has been described in the H/N patient population(56) and may be another measure to assess postoperative QoL in dental reconstructive patients. While this current study focuses on survival and implant osteointegration, the main clinical outcome of interest in this population is dentoalveolar restoration. Implants are critical to this goal, but if the goal is not attained for any number of reasons, a patient who has integrated implants is, in essence, no different from one without. Implants are the foundation and enable the end goal, yet certainly from the patient perspective, are of little relevance without a final prosthesis.

Implant osseointegration may vary according to bone flap source, flap height and density, discrepancy of the transplanted flap, and the quality of peri-implant soft tissue. Most studies in this review used FFF, a mainstay of mandibular reconstruction due to its ease in harvesting, elevating with skin, muscle, and crural septum, and osteotomizing at various points, allowing for adaptation. Deep circumflex iliac artery (DCIA) flap was the second most common flap. The disadvantage of DCIA flaps is its cutaneous component is often unreliable due to the absence of skin perforators arising from the DCIA(57) Although this study did not assess overall survival based on flap type, Fenlon et al., reported equal survival among all flap types, including FFF, DCIA flap, RAFF, and rib(23) Bone height correction techniques, such as double-barrel fibula,(13) vertical distraction osteogenesis, and bone-only grafts, also improved implant stability and allowed for optimal dental occlusion to facilitate movements required for chewing, swallowing, or speech. However, at this institution, double-barreling the fibula may adversely impact final restoration because of too much bone height and inability to place the final prosthesis. Barber et al. reported greater 5-year survival of implants in bone-impacted FFF (96%), in which morselized fibula is used to fill the medullary cavity of FFF, compared with the traditional FFF (77 %; p <0.01)7. However, there was no difference in survival between the irradiated and non-radiated groups (83.3% vs. 84.6%; p=0.70). One study demonstrated additional soft tissue management procedures (i.e., vestibuloplasty with fibromucosal, palatal mucosal, or skin graft and sub-periosteal dissection with denture-guided epithelial regeneration(33)) had improved implant stability and survival.

The current findings should be interpreted in light of the strengths and limitations of the literature. This review encompasses all English publications over two decades and is comprehensive; however, there may be temporal bias due to recent trends in implant types and surgical developments. The data is subject to the heterogeneity of the included studies, data collection methods, and follow-up time. As longer follow-ups tend to lead to higher implant failure rates, the results may be affected by survival bias. As reported by Ch’ng et al., most implants were lost after 60 months of follow-up(38). In this review, the median follow-up was 36 months; only eight studies reported 92.1% survival at median follow-up of 60 months or longer. implant type and prosthesis design were not studied separately; these are factors that could affect implant outcome39. Implant loss over time would be ideally examined using Kaplan Meyer time to even analysis techniques, however unfortunately due to the lack of granular data this was not possible. Furthermore, it is critical to consider the interactions of multiple implants placed in an individual patient. Given that prostheses require more than a single implant for support, as well as the fact that loss of an implant could render a full construct unusable, the concept of implant interaction is critical. A better analysis may be a clustered survival analysis utilizing more robust statistical techniques, though the current data did not enable such to be performed(58–60). Lastly, given the heterogeneity of studies, we were unable to determine with appropriate accuracy differences between maxillary implants and mandibular implants. Prospective studies should be conducted to further investigate these aspects of dental implant placement and prosthesis design following oromaxillofacial reconstruction, especially in patients undergoing H/N cancer surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

Osseointegrated dental implant placement into vascularized bone flaps is a successful technique that improves function and health-related QoL and should be strongly considered in patients undergoing segmental mandibular or maxillary reconstruction. For the oncologic patient, the data support greater implant survival rates when placed before RT. The success of immediate implant placement can be leveraged with using emerging technologies (virtual surgical planning), which allow for accurate positioning while accelerating the process of dental restoration.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Table shows Types of Implants Per Study.

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Table shows Survival Outcome in Patients Who Underwent Immediate Dental Implant Placement.

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Table shows Survival Outcome in Patients Who Underwent Delayed Dental Implant Placement.

Acknowledgement:

The study was supported in part by NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Abbreviations

- DCIA

deep circumflex iliac artery

- EORTC

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- FFF

free fibula flap

- H/N

head and neck

- OHIP

Oral Health Impact Profile

- MINORS

Methodological Index for Non-randomized Studies (MINORS)

- RAFF

radial artery free flap

- RR

risk ratios

- RT

radiotherapy

- QLQ-H&N 35

Quality of Life Questionnaire-Head and Neck

- QoL

quality of life

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hayter JP, Cawood JI Oral rehabilitation with endosteal implants and free flaps. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996;25:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoen PJ, Raghoebar GM, Bouma J, et al. Prosthodontic rehabilitation of oral function in head-neck cancer patients with dental implants placed simultaneously during ablative tumour surgery: an assessment of treatment outcomes and quality of life. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;37:8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu J, Xiao Y, Liu F, Wang J, Yang W, Xie W Measures of health-related quality of life and socio-cultural aspects in young patients who after mandible primary reconstruction with free fibula flap. World J Surg Oncol 2013;11:250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu J, Yang Y, Li W Assessment of quality of life and sociocultural aspects in patients with ameloblastoma after immediate mandibular reconstruction with a fibular free flap. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014;52:163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qaisi M, Kolodney H, Swedenburg G, Chandran R, Caloss R Fibula jaw in a day: state of the art in maxillofacial reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;74:1284 e1281–1284 e1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sclaroff A, Haughey B, Gay WD, Paniello R Immediate mandibular reconstruction and placement of dental implants. At the time of ablative surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994;78:711–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barber BR, Dziegelewski PT, Chuka R, O’Connell D, Harris JR, Seikaly H. Bone-impacted fibular free flap: Long-term dental implant success and complications compared to traditional fibular free tissue transfer. Head Neck 2016;38(Suppl1):E1783–E1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buddula A, Assad DA, Salinas TJ, Garces YI Survival of dental implants in native and grafted bone in irradiated head and neck cancer patients: a retrospective analysis. Indian J Dent Res 2011;22:644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hundepool AC, Dumans AG, Hofer SO, et al. Rehabilitation after mandibular reconstruction with fibula free-flap: clinical outcome and quality of life assessment. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;37:1009–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodard AG, Bémer J, Gourmet R, et al. Dental implants and free fibula flap: 23 patients. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac 2011;112:e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang YM, Wallace CG, Tsai CY, Shen YF, Hsu YM, Wei FC Dental implant outcome after primary implantation into double-barreled fibula osteoseptocutaneous free flap-reconstructed mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;128:1220–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barber HD, Seckinger RJ, Hayden RE, Weinstein GS Evaluation of osseointegration of endosseous implants in radiated, vascularized fibula flaps to the mandible: a pilot study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995;53:640–644; discussion 644–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zlotolow IM, Huryn JM, Piro JD, Lenchewski E, Hidalgo DA Osseointegrated implants and functional prosthetic rehabilitation in microvascular fibula free flap reconstructed mandibles. Am J Surg 1992;164:677–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qu X, Zhang C, Yang W, Wang M Deep circumflex iliac artery flap with osseointegrated implants for reconstruction of mandibular benign lesions: clinical experience of 33 cases. Ir J Med Sci 2013;182:493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang YM, Santamaria E, Wei FC, et al. Primary insertion of osseointegrated dental implants into fibula osteoseptocutaneous free flap for mandible reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102:680–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang F, Huang W, Zhang C, Sun J, Kaigler D, Wu Y Comparative analysis of dental implant treatment outcomes following mandibular reconstruction with double-barrel fibula bone grafting or vertical distraction osteogenesis fibula: a retrospective study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2015;26:157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurlek A, Miller MJ, Jacob RF, Lively JA, Schusterman MA Functional results of dental restoration with osseointegrated implants after mandible reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;101:650–655; discussion 656–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster RD, Anthony JP, Sharma A, Pogrel MA Vascularized bone flaps versus nonvascularized bone grafts for mandibular reconstruction: an outcome analysis of primary bony union and endosseous implant success. Head Neck 1999;21:66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schliephake H, Schmelzeisen R, Husstedt H, Schmidt-Wondera LU Comparison of the late results of mandibular reconstruction using nonvascularized or vascularized grafts and dental implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999;57:944–950; discussion 950–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovacs AF Influence of the prosthetic restoration modality on bone loss around dental implants placed in vascularized iliac bone grafts for mandibular reconstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;123:598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramer FJ, Dempf R, Bremer B Efficacy of dental implants placed into fibula-free flaps for orofacial reconstruction. Clin Oral Implants Res 2005;16:80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrowman RA, Wilson PR, Wiesenfeld D Oral rehabilitation with dental implants after cancer treatment. Aust Dent J 2011;56:160–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenlon MR, Lyons A, Farrell S, Bavisha K, Banerjee A, Palmer RM Factors affecting survival and usefulness of implants placed in vascularized free composite grafts used in post-head and neck cancer reconstruction. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2012;14:266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kniha K, Mohlhenrich SC, Foldenauer AC, et al. Evaluation of bone resorption in fibula and deep circumflex iliac artery flaps following dental implantation: a three-year follow-up study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2017;45:474–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgess M, Leung M, Chellapah A, Clark JR, Batstone MD Osseointegrated implants into a variety of composite free flaps: a comparative analysis. Head Neck 2017;39:443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw RJ, Sutton AF, Cawood JI, et al. Oral rehabilitation after treatment for head and neck malignancy. Head Neck 2005;27:459–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fierz J, Hallermann W, Mericske-Stern R Patients with oral tumors. Part 1: Prosthetic rehabilitation following tumor resection. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed 2013;123:91–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Virgin FW, Iseli TA, Iseli CE, et al. Functional outcomes of fibula and osteocutaneous forearm free flap reconstruction for segmental mandibular defects. Laryngoscope 2010;120:663–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bodard AG, Salino S, Desoutter A, Deneuve S Assessment of functional improvement with implant-supported prosthetic rehabilitation after mandibular reconstruction with a microvascular free fibula flap: a study of 25 patients. J Prosthet Dent 2015;113:140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang W, Liu YP, Ma Q, Liu BL, Zhao Y Long-term results of mandibular reconstruction of continuity defects with fibula free flap and implant-borne dental rehabilitation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2015;30:169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrari S, Copelli C, Bianchi B, et al. Rehabilitation with endosseous implants in fibula free-flap mandibular reconstruction: a case series of up to 10 years. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2013;41:172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hakim SG, Kimmerle H, Trenkle T, Sieg P, Jacobsen HC Masticatory rehabilitation following upper and lower jaw reconstruction using vascularised free fibula flap and enossal implants-19 years of experience with a comprehensive concept. Clin Oral Investig 2015;19:525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar VV, Ebenezer S, Kammerer PW, et al. Implants in free fibula flap supporting dental rehabilitation--Implant and peri-implant related outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2016;44:1849–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smolka K, Kraehenbuehl M, Eggensperger N, et al. Fibula free flap reconstruction of the mandible in cancer patients: evaluation of a combined surgical and prosthodontic treatment concept. Oral Oncol 2008;44:571–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sozzi D, Novelli G, Silva R, Connelly ST, Tartaglia GM Implant rehabilitation in fibula-free flap reconstruction: a retrospective study of cases at 1–18 years following surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2017;45:1655–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Y, Huang W, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Zou D Long-term success of dental implant-supported dentures in postirradiated patients treated for neoplasms of the maxillofacial skeleton: a retrospective study. Clin Oral Investig 2016;20:2457–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roumanas ED, Markowitz BL, Lorant JA, Calcaterra TC, Jones NF, Beumer J 3rd. Reconstructed mandibular defects: fibula free flaps and osseointegrated implants. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;99:356–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ch’ng S, Skoracki RJ, Selber JC, et al. Osseointegrated implant-based dental rehabilitation in head and neck reconstruction patients. Head Neck 2016;38Suppl 1:E321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackson RS, Price DL, Arce K, Moore EJ Evaluation of clinical outcomes of osseointegrated dental implantation of fibula free flaps for mandibular reconstruction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 2016;18:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teoh KH, Huryn JM, Patel S, et al. Implant prosthodontic rehabilitation of fibula free-flap reconstructed mandibles: a Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center review of prognostic factors and implant outcomes. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2005;20:738–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garrett N, Roumanas ED, Blackwell KE, et al. Efficacy of conventional and implant-supported mandibular resection prostheses: study overview and treatment outcomes. J Prosthet Dent 2006;96:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raoul G, Ruhin B, Briki S, et al. Microsurgical reconstruction of the jaw with fibular grafts and implants. J Craniofac Surg 2009;20:2105–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salinas TJ, Desa VP, Katsnelson A, Miloro M Clinical evaluation of implants in radiated fibula flaps. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010;68:524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dholam KP, Bachher GK, Yadav PS, Quazi GA, Pusalkar HA Assessment of quality of life after implant-retained prosthetically reconstructed maxillae and mandibles postcancer treatments. Implant Dent 2011;20:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meloni SM, De Riu G, Pisano M, Massarelli O, Tullio A Computer assisted dental rehabilitation in free flaps reconstructed jaws: one year follow-up of a prospective clinical study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012;50:726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gbara A, Darwich K, Li L, Schmelzle R, Blake F Long-term results of jaw reconstruction with microsurgical fibula grafts and dental implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;65:1005–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobsen C, Kruse A, Lubbers HT, et al. Is mandibular reconstruction using vascularized fibula flaps and dental implants a reasonable treatment? Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2014;16:419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marx RE, Ames JR The use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in bony reconstruction of the irradiated and tissue-deficient patient. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1982;40:412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Urken ML, Buchbinder D, Weinberg H, Vickery C, Sheiner A, Biller HF Primary placement of osseointegrated implants in microvascular mandibular reconstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1989;101:56–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allen RJ Jr., Shenaq DS, Rosen EB, et al. Immediate dental implantation in oncologic jaw reconstruction: workflow optimization to decrease time to full dental rehabilitation. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2019;7:e2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buchbinder D, Urken ML, Vickery C, Weinberg H, Sheiner A, Biller H Functional mandibular reconstruction of patients with oral cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1989;68:499–503; discussion 503–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobsson M, Tjellstrom A, Thomsen P, Albrektsson T, Turesson I Integration of titanium implants in irradiated bone. Histologic and clinical study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1988;97:337–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsui Y, Ohno K, Michi K, Tachikawa T Histomorphometric examination of healing around hydroxylapatite implants in 60Co-irradiated bone. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994;52:167–172; discussion 172–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marx RE, Johnson RP, Kline SN Prevention of osteoradionecrosis: a randomized prospective clinical trial of hyperbaric oxygen versus penicillin. J Am Dent Assoc 1985;111:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petrovic I, Panchal H, De Souza Franca PD, Hernandez M, McCarthy CC, Shah P A systematic review of validated tools assessing functional and aesthetic outcomes following fibula free flap reconstruction of the mandible. Head Neck 2019;41:248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cracchiolo JR, Klassen AF, Young-Afat DA, et al. Leveraging patient-reported outcomes data to inform oncology clinical decision making: introducing the FACE-Q head and neck cancer module. Cancer 2019;125:863–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Genden EM, Wallace D, Buchbinder D, Okay D, Urken ML Iliac crest internal oblique osteomusculocutaneous free flap reconstruction of the postablative palatomaxillary defect. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001;127:854–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Susarla SM, Chuang SK, Dodson TB Delayed versus immediate loading of implants: survival analysis and risk factors for dental implant failure. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons 2008;66:251–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chuang SK, Tian L, Wei LJ, Dodson TB Predicting dental implant survival by use of the marginal approach of the semi-parametric survival methods for clustered observations. Journal of dental research 2002;81:851–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chuang SK, Tian L, Wei LJ, Dodson TB Kaplan-Meier analysis of dental implant survival: a strategy for estimating survival with clustered observations. Journal of dental research 2001;80:2016–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Table shows Types of Implants Per Study.

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Table shows Survival Outcome in Patients Who Underwent Immediate Dental Implant Placement.

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Table shows Survival Outcome in Patients Who Underwent Delayed Dental Implant Placement.