Abstract

The identification of Candida auris fungemia in critically ill COVID‐19 patients is detrimental, with huge implications on patient mortality and infectious control measures.

Keywords: Candida auris, candidemia, COVID‐19

The identification of Candida auris fungemia in critically ill COVID‐19 patients is detrimental, with huge implications on patient mortality and infectious control measures.

1. INTRODUCTION

Candida auris is an emerging highly resistant pathogen with considerable mortality, particularly in critically ill patients. We describe a case of fatal candidemia caused by C. auris in a patient with critical COVID‐19 disease to raise awareness of the circumstances leading to coinfection with this emerging resistant yeast.

The year 2019 heralds the start of severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS‐Cov‐2) and its clinical manifestation COVID‐19 disease which initially originated from China then propagated globally leading to significant morbidity and mortality as well as considerable economic consequences.1 Although the disease has a wide range of clinical manifestations, only patients with severe and critical illnesses have the most serious consequences. During the course of the perplexing disease, it was noticed early, leading to ominous consequences such as the development of catastrophic immunological storms as well as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) which promoted the use of various therapeutic interventions including immunosuppressive therapy.2 Dysregulation of the immune responses particularly cytokine storm led to the use of steroids, interleukin (IL) inhibitors such as IL‐1 inhibitor; anakinra, and IL‐6 inhibitor; tocilizumab which compromise host immune responses provoking the emergence of latent and opportunistic coinfections including multidrug‐resistant organisms.3 Among secondary consequences, fungal infections with all their morbidity and mortality have been reported early during the pandemic.4 This can be explained because the pandemic caught all health systems around the world by surprise, escalating cases at critical care beds facilitated infection spread, invasive devices including mechanical ventilation accelerated infections risks while the use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics as well as immunosuppressive therapy, created the suitable environment for coinfections.5 Consequently, the advent of resistant opportunistic organisms such as C. auris is inevitable.6

Candida auris, an emerging multidrug‐resistant candida is first described in Japan then subsequently spread globally with the ability to cause invasive infection as well as pose substantial risks for infection control and prevention.7

From accumulated experience in treating patients in critical care, timely pathogen identification and early recognition of antimicrobial susceptibilities are of paramount importance as manifested in cases of invasive fungemia best outlined through multidrug‐resistant candidemia where appropriate antifungal treatment with concurrent strict infection control and prevention measures are crucial to avoid ominous outcomes.8

To highlight this, we describe a case of fatal C. auris fungemia in a critically ill COVID‐19 patient discussing relevant associated risks leading to the event aiming to raise awareness regarding the circumstances and the emergence of multidrug‐resistant opportunistic pathogens during the COVID‐19 pandemic and review the literature for similar cases.

2. CASE DESCRIPTION

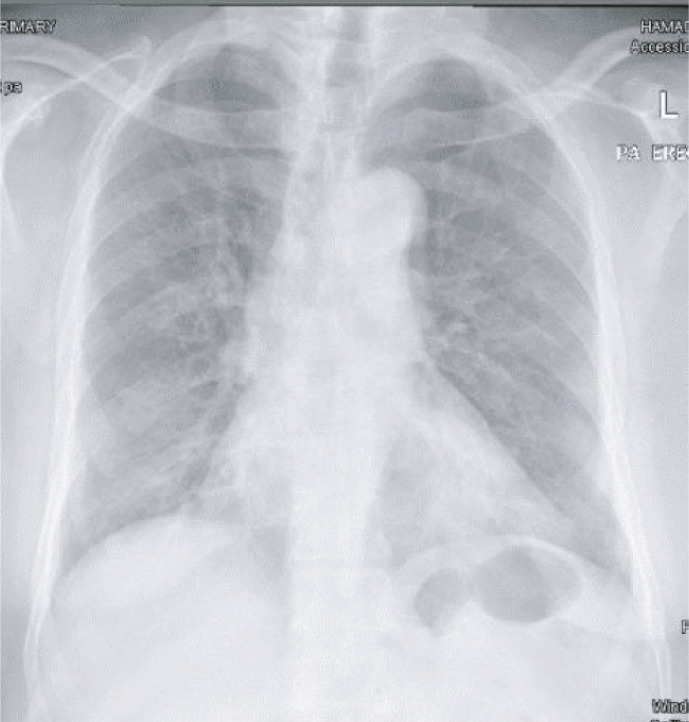

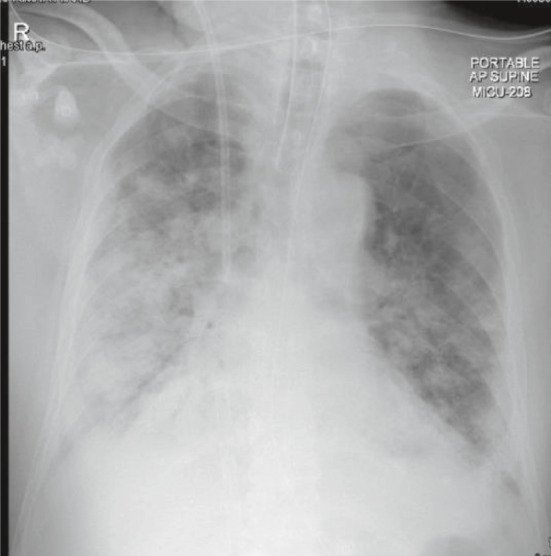

A 64‐year‐old gentleman with no known comorbidities presented to our emergency department with symptoms of fever, cough, and progressive shortness of breath for about 10 days duration. Because of the typical symptoms of COVID‐19 disease in the context of the pandemic, the diagnosis was suspected early were chest X‐ray demonstrated bilateral infiltrates, and the diagnosis was subsequently confirmed by a positive SARS‐Cov2 PCR then managed as per local protocols at that time with azithromycin and a combination of lopinavir and ritonavir (Figure 1). Shortly after admission, the patient deteriorated with elevated inflammatory markers, including IL‐6 230 pg/ml (normal <8) and ferritin 2331 μ/L (30–553) progressed to ARDS, clinically assessed as COVID‐19‐related cytokine storm (CCS). The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), intubated, and treated with steroids as well as an IL‐6 inhibitor, tocilizumab (total dose of 1200 mg, in two separate doses) in addition to broad‐spectrum antibiotics, piperacillin‐tazobactam, teicoplanin then cefepime to manage the accompanying ventilator‐associated pneumonia. Despite maximum measures of high plateau pressures and prone ventilation positions, the patient failed to maintain adequate saturation levels and continued to deteriorate which prompted commencing veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). During the subsequent course, the patient received additional courses of antibiotics to treat sepsis when MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were isolated from tracheal aspirates. Due to worsening of the clinical condition with increased inflammatory markers, progressive radiological shadowing, and non‐response to broad‐spectrum antibiotics, bronchoscopy, and bronchoalveolar lavage performed on day 23 of ICU admission grew Candida tropicalis when anidulafungin was added to the management. Despite these measures, the patient continued to deteriorate developing acute kidney and liver injuries necessitating hemodialysis support. Eventually, the patient's condition stabilized and was weaned off the ventilator support through tracheostomy accompanied by the settling of radiological and inflammatory markers. However, on day 41, the patient developed fever, raised inflammatory markers, and new radiological infiltrates (Figure 2). The patient underwent repeated bronchoscopy and was covered empirically with liposomal amphotericin to cover the subsequently isolated Candida glabrata resistant to echinocandins. Despite initial improvement, the patient deteriorated with septic shock on day 45 with rapid deterioration and eventually succumbed to death. Subsequently, blood cultures obtained from the time of deterioration grew C. auris from both central and peripheral lines resistant to fluconazole and amphotericin but were susceptible to echinocandins.

FIGURE 1.

Chest X‐ray demonstrating patchy ground glass opacity in the lower lung zones bilaterally

FIGURE 2.

Chest X‐ray highlighting the progression of bilateral pulmonary infiltration, consolidations, and pleural effusion

3. DISCUSSION

After almost a century of a serious worldwide disease, the novel COVID‐19 emerging pandemic started to shape the profile of infectious diseases and health care across the globe. Undiagnosed clusters of pneumonia cases in Wuhan city, China diagnosed eventually as a novel SARS‐COV‐2 virus and COVID‐19 disease spearheaded global consequences with significant morbidity, mortality, and socioeconomic consequences never witnessed before.1

Because of enhanced communication and global collaborations, the clinical manifestations of the COVID‐19 disease were recognized, highlighted, and shared early together with associated infective and non‐infective consequences including secondary microbial infections particularly healthcare‐associated infections (HAIs).9 Of the leading HAIs, secondary fungal infections are particularly worrisome since it is usually associated with delayed diagnosis, suboptimal management with significant morbidity and mortality leading to ominous consequences. With the evolving COVID‐19 pandemic, various nosocomial invasive secondary fungal infections were inevitable spanning common organisms such as candida sp and aspergillus sp to the relatively uncommon such cryptococcal disease as well as the rare occurrence of C. auris 6, 9

Together with other invasive fungal infections, patients reported with invasive C. auris disease share many risk factors such as critical disease including recurrent sepsis, prolonged ICU stay with invasive devices, mechanical ventilation, broad‐spectrum antibiotics, and immunosuppressive conditions.10 Our patient fulfilled all the highlighted risk factors that favor acquiring invasive fungal disease in addition to the selective management of respiratory failure secondary to ARDS with ECMO support. It is worth noticing both ARDS and ECMO carry higher risks of secondary and opportunistic infections including invasive fungal disease.11 Furthermore, management of critical disease during the unprecedented pandemic, entailed unconventional approaches repurposing different modalities of therapeutic interventions. To suppress the harmful effect of the secondary immunological storm (CCS), immunosuppressive therapy such as steroids and interleukins inhibitors such as anakinra and tocilizumab has been used frequently with accumulated evidence of efficacy.12 It has been suggested that immunosuppressive treatment particularly biological components are associated with secondary microbial infections in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID‐19.3

It is plausible in our case to assume the invasive C. auris infection is a nosocomial infection acquired through the central line device since it has been recently recognized by the institution, worsened by the busy pandemic as well‐being isolated concomitantly peripherally and centrally from the cultured line within the conceivable time frame. From previous outbreaks and reported invasive diseases, C. auris has a high ability to colonize the skin and environmental surface, including medical devices, leading to significant loss of devices, nosocomial outbreaks as well as significant mortalities.13 The reported mortality rate of C. auris fungemia during the COVID‐19 disease is 60%, and surprisingly, C. auris was the most common cause among candida species.10

Regarding appropriate antifungal therapy, C. auris is surprisingly resistant to amphotericin therapy being sensitive to echinocandins.14 The clinical judgment of covering our patient with amphotericin was appropriate at the time to cover resistant C. glabrata grew from bronchoalveolar lavage cultures. The absence of clinical response in such cases should raise the suspicion of an alternative/and or second pathology.

The identification of C. auris fungemia is a crucial step in management and should be followed by actively implementing strict infectious control measures such as contact precautions, screening, and diligent decolonization of the patients.8 The organism is notoriously difficult to apply infection control and prevention measures once established in healthcare settings and all effort should be sought to contain the problem geographically avoiding patient's movement with the hospital as well as cross transfer to other healthcare facilities. Despite that, these infectious control measures might further jeopardize the limited intensive care beds available to critically ill patients with COVID‐19 especially in countries with limited resources.6

The management of C. auris fungemia is challenging, and multidrug‐resistant C. auris isolates are defined when resistance identified to the three main classes of antifungal with fluconazole yields the highest minimal inhibitory concentration(MIC) while echinocandin is an appropriate empirical first choice of therapy.14

Unfortunately, the blood cultures of our patient were revealed positive after he passed away due to his C. auris fungemia and severe COVID‐19 infection.

Our search of the literature yielded a total of 36 cases of infection due to C. auris in COVID‐19. (Table 1). Male constituted the majority and the age range 25–86 years. Candidemia is the predominant presentation with five cases were isolated from both urine and blood.10,15,16 Of note, only six cases reported of C. aruis in urine alone and three isolates from deep tracheal aspirated.15,16 Days in the hospital to develop the infection ranging between 4–45 days and most patients have significant underlining comorbidities. Almost half of the reported cases were associated with either bacterial or other fungal coinfection and/or colonization.10,15,17 Of the 36 cases reviewed, almost all have a urinary indwelling catheter, central lines, and on broad‐spectrum antibiotics except for four cases where the data is not obtainable.17 Most cases received steroids while only five cases received tocilizumab, though the data were not always available. The mortality rate is 53% of the 30 cases with the documented outcomes (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of previously reported adult cases of infection due to Candida auris in COVID‐19

| Study | Case | Gender/Age, years | Days in hospital | Days in hospital to positive blood/urine culture | Underlining comorbidities | Coinfection/colonization | Intubation | Urinary indwelling catheter | Presence of central lines | Broad‐spectrum antibiotics used | Steroid used | TOCI used | Anti‐fungal used | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chowdhary, 202010 | 1 | F/25 | 35 | 14 | CLD with grade II encephalopathy, AKI | 4 of the 10 cases reported by Chowdhary developed bacteremia (Enterobacter cloacae and Staphylococcus haemolyticus) | Half of the cases reported by Chowdhary were received mechanical ventilation | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | AMB | Alive |

| Chowdhary, 202010 | 2 | M/52 | 20 | 14 | HTN, DM | As noted above on the same study | As noted above on the same study | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | MFG and AMB | Died |

| Chowdhary, 202010 | 3 | F/82 | 60 | 42(blood and urine) | HTN, DM, hypothyroidism, on dialysis for CKD stage 5 | As noted above on the same study. | As noted above on the same study | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | MFG | Died |

| Chowdhary, 202010 | 4 | F/86 | 21 | 10 | CLD, IHD, DM | As noted above on the same study. | As noted above on the same study | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | MFG | Died |

| Chowdhary, 202010 | 5 | M/66 | 20 | 11 | HTN, DM, asthma | As noted above on the same study | As noted above on the same study | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | MFG and AMB | Alive |

| Chowdhary, 202010 | 6 | M/71 | 32 | 12(blood and urine) | Hypothyroidism, on dialysis for CKD stage 5 | As noted above on the same study | As noted above on the same study | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | MFG | Died |

| Chowdhary, 202010 | 7 | M/67 | 21 | 11 | HTN, DM, COPD | As noted above on the same study | As noted above on the same study | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | MFG and AMB | Alive |

| Chowdhary, 202010 | 8 | M/72 | 27 | 16 | HTN, CLD | As noted above on the same study | As noted above on the same study | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | MFG | Died |

| Chowdhary, 202010 | 9 | M/81 | 20 | 15 | DM, HTN, IHD | As noted above on the same study | As noted above on the same study | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | MFG | Died |

| Chowdhary, 202010 | 10 | M/69 | 21 | 14 | HTN, asthma | As noted above on the same study | As noted above on the same study | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | MFG | Alive |

| Rodriguez, 202018 | 11–16 | 6 out of 20 cases reported were C. auris | Of the 20 cases,13 M and 7 F | Age mean 63 | NA | Mean number of days 17.7 (range 6–35 days) | HTN, DM, CKD, Cancer | NA | 19 out of the 20 cases | 19 out of the 20 cases | 19 out of the 20 cases | All patients received β‐lactam antibiotics | 19 out of the 20 cases | 30‐day mortality is 60% |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 17 | M/51 | Mean 20–70 days | 37 | HTN, DM2, Obesity | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | No | CAS, ANF | Died |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 18 | M/54 | Mean 20–70 days | 17, urine | HTN, DM2, Obesity, Asthma | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | No | ISA, CAS | Alive |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 19 | M/35 | Mean 20–70 days | 29 | HTN, DM2, CAD | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida glabrata | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | No | ANF | Died |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 20 | M/51 | Mean 20–70 days | 36, urine | Obesity | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida glabrata, Enterococcus faecalis | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | No | ISA, ANF | Died |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 21 | M/64 | Mean 20–70 days | 13 (blood and urine) | AKI | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | No | CAS, VRC, AMB (intravesical) | Died |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 22 | M/64 | Mean 20–70 days | 10 (blood and urine) | HTN, Smoking, Obesity, Hypothyroidism | Candida glabrata | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | Yes | ANF, ISA | Died |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 23 | F/54 | Mean 20–70 days | 31 | HTN, Obesity | None | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | No | AMB, CAS, VRC | died |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 24 | F/60 | Mean 20–70 days | 16, urine | Obesity | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | No | CAS, ANF, VRC | Died |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 25 | M/58 | Mean 20–70 days | 27, urine | HTN, Obesity | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | No | ANF | Died |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 26 | M/36 | Mean 20–70 days | 22, Urine | DM2, Obesity | Cytomegalovirus | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | Yes | CAS | Alive |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 27 | M/66 | Mean 20–70 days | 11, Urine | HTN, DM2, CAD, VHD | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltofilia | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | No | VRC, CAS | Alive |

| Villanueva‐Lozano, 202115 | 28 | M/46 | Mean 20–70 days | 27 | Obesity | None | Yes | Yes | Peripherally inserted central lines | Yes | Yes | No | VRC, CAS | Alive |

| Magnasco, 202117 | 29 | M/62 | NA | 45 (Time from ICU Admission to First Isolation | None | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA | NA | CAS | Alive |

| Magnasco, 202117 | 30 | M/69 | NA | 41 (Time from ICU Admission to First Isolation | CAD | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA | NA | CAS, 19 days; then AMB 7 days | Died |

| Magnasco, 202117 | 31 | M/62 | NA | 26 (Time from ICU Admission to First Isolation | HTN | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA | NA | CAS | Alive |

| Magnasco, 202117 | 32 | M/64 | NA | 4 (Time from ICU Admission to First Isolation | HTN, asthma | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA | NA | CAS | Died |

| Allaw, 202116 | 33 | M/75 | NA | 40, Blood and urine | metastatic prostate cancer | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Alive |

| Allaw, 202116 | 34 | F/68 | NA | 40, DTA | None | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Alive |

| Allaw, 202116 | 35 | M/71 | NA | 15, DTA | Cutaneous T cell lymphoma in remission | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Alive |

| Allaw, 202116 | 36 | M/75 | NA | 10, DTA | None | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Alive |

| Our case,2021 | 37 | M/64 | 47 | 45 | None | MRSA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida tropicalis, Candida glabrata, Trichosporon asahii | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ANF, AMB, Passed away before the final identifications | Died |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; AMB, amphotericin B; ANF, anidulafungin; CAD, coronary artery disease; CAS: caspofungin; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CLD, chronic liver disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; DTA, deep tracheal aspirate; HTN, hypertension; IHD, ischemic heart disease; ISA, isavuconazole; MFG, micafungin; TOCI, tocilizumab; VHD, valvular heart disease; VRC, voriconazole.

4. CONCLUSION

Candida auris fungemia is an emerging invasive pathogen in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients that required attention, not only due to high mortality and resistance profile but to scrupulous infectious control measures to prevent the potential nosocomial spread.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

WG: Corresponding author, clinical management, data acquisition, literature search, manuscript writing, and final proof reading. GA: Contribution of data acquisition, manuscript preparation, and literature search. MA: Clinical management, data acquisition, and manuscript writing. EI contributed to data acquisition and Microbiology reports. HA and MA supervised all the aspects.

CONSENT

Published with written consent of the patient.

5. ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethics approval and permission were obtained to publish the case reports from the institutional review board which is in line with international standards, MRC04201075.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Qatar National Library for providing the open access fees.

Goravey W, Ali GA, Ali M, Ibrahim EB, Al Maslamani M, Abdel Hadi H. Ominous combination: COVID‐19 disease and Candida auris fungemia—Case report and review of the literature. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:e04827. 10.1002/ccr3.4827

Funding information

No funding was received toward the publication

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the datasets supporting the findings of this case including obtained consent from the patient`s next of kin in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Qun L, Xuhua G, Peng W, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID‐19: a meta‐analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1330–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Somers EC, Eschenauer GA, Troost JP, et al. Tocilizumab for treatment of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID‐19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;73(2):e445–e454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antinori S, Bonazzetti C, Gubertini G, et al. Tocilizumab for cytokine storm syndrome in COVID‐19 pneumonia: an increased risk for candidemia? Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(7):102564. 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chowdhary A, Sharma A. The lurking scourge of multidrug resistant Candida auris in times of COVID‐19 pandemic. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;22:175–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satoh K, Makimura K, Hasumi Y, Nishiyama Y, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiol Immunol. 2009;53(1):41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osei SJ. Candida auris, a systematic review and meta‐analysis of current updates on an emerging multidrug‐resistant pathogen. Microbiologyopen. 2018;7(4):e00578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y, Li W, Wang Z, Chen H, Tian L, Liu D. Nosocomial infection among patients with COVID‐19: a retrospective data analysis of 918 cases from a single center in Wuhan, China. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(8):982–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowdhary A, Tarai B, Singh A, Sharma A. Multidrug‐resistant Candida auris infections in critically Ill Coronavirus disease patients, India, April–July 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020.26(11);2694–2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun HY, Ko WJ, Tsai PR, et al. Infections occurring during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use in adult patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140(5):1125–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horby PW, Campbell M, Staplin N, et al. Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital withcovid‐19 (recovery): preliminary results of a randomised, controlled, open‐label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10285):1637–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Meis JF. Candida auris: a rapidly emerging cause of hospital‐acquired multidrug‐resistant fungal infections globally. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(5):e1006290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chowdhary A, Prakash A, Sharma C, et al. A multicentre study of antifungal susceptibility patterns among 350 Candida auris isolates (2009–17) in India: role of the ERG11 and FKS1 genes in azole and echinocandin resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(4):891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villanueva‐Lozano H, de Treviño‐Rangel RJ, González GM, et al. Outbreak of Candida auris infection in a COVID‐19 hospital in Mexico. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(5):813–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allaw F, Kara Zahreddine N, Ibrahim A, et al. First Candida auris outbreak during a covid‐19 pandemic in a tertiary‐care center in Lebanon. Pathogens. 2021;10(2):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnasco L, Mikulska M, Giacobbe DR, et al. Spread of carbapenem‐resistant gram‐negatives and Candida auris during the covid‐19 pandemic in critically ill patients: one step back in antimicrobial stewardship? Microorganisms. 2021;9(1):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez JY, Le Pape P, Lopez O, Esquea K, Labiosa AL, Alvarez‐Moreno C. Candida auris: a latent threat to critically ill patients with Coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1595. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1595. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the datasets supporting the findings of this case including obtained consent from the patient`s next of kin in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy are available from the corresponding author upon request.