Abstract

Background

One of the most valued targets in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is for physicians to provide and patients to receive a high‐level quality of care. This study aimed to evaluate the implementation of a nationwide quality certification programme for IBD units.

Methods

Identification of quality indicators (QI) for IBD Unit certification was based on Delphi methodology that selected 53 QI, which were subjected to a normalisation process. Selected QI were then used in the certification process. Coordinated by GETECCU, this process began with a consulting round and an audit drill followed by a formal audit carried out by an independent certifying agency. This audit involved the scrutiny of the selected QI in medical records. If 80%–90% compliance was achieved, the IBD unit audited received the qualification of “advanced”, and if it exceeded 90% the rating was “excellence”. Afterwards, an anonymous survey was conducted among certified units to assess satisfaction with the programme for IBD units.

Results

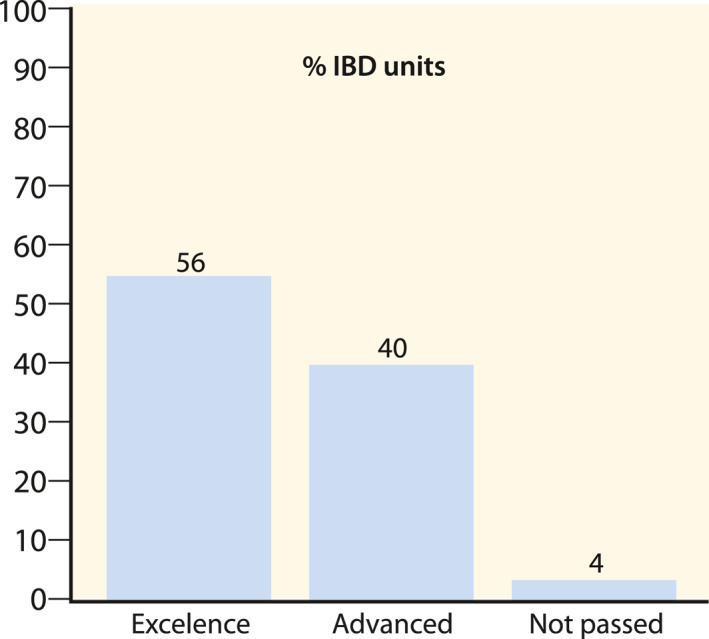

As of January 2021, 66 IBD units adhere to the nationwide certification programme. Among the 53 units already audited by January 2021, 31 achieved the certification of excellence, 20 the advanced certification, and two did not obtain the certification. The main survey results indicated high satisfaction with an average score of 8.5 out of 10.

Conclusion

Certification of inflammatory bowel disease units by GETECCU is the largest nationwide certification programme for IBD units reported. More than 90% of IBD units adhered to the programme achieved the certification.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, quality indicators, quality of care, standards, unit

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), either Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic, progressive, and life‐long condition that affects a large number of people in our country.1, 2 Lifetime medical costs associated with IBD care are comparable to those of other severe chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus or cancer.3 IBD is typically managed by gastroenterologists in collaboration with other healthcare specialities. IBD is, therefore, a multifaceted and complex disease with a major impact on the patient’s quality of life. For this reason, it is best managed in a specialised IBD unit with a multidisciplinary team of experts in the different aspects of this disease.4 Furthermore, the presence of an IBD specialist nurse is compulsory in an IBD unit to provide physical and emotional support to patients, together with healthcare education.5

Key points.

Summarise the established knowledge on this subject

One of the most highly valued targets in IBD treatment is to achieve a high‐level quality of care

IBD units are the best way to provide this high‐level quality of care

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

CUE is the largest nationwide certification programme for IBD units reported to date.

Certification by an independent agency gives added value to the programme.

More than 90% of IBD units that adhered to the programme achieved the certification.

The Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU) is a Medical Society with more than 30 years of history and more than one thousand members all over our country. It has the mission to promote excellence in healthcare, teaching, and research, establishing reliable standards of IBD care in Spain. In accordance with these principles, a group of GETECCU gastroenterologists developed a set of quality indicators (QI), based on Delphi methodology and in collaboration with other stakeholders such as patients’ associations and nurses. Fifty‐three of these QI (18 of structure, 32 of process, and 3 of results) were then selected and subjected to a normalisation process.6 GETECCU decided that compliance with these indicators should define the essence of an IBD unit.

Quality of care audits have been performed for other diseases, including audits of stroke units supported by the European Stroke Organisation.7 Within IBD care, there have been other rather limited programmes similar to ours that retrospectively audited medical records from practices in academic, community, and private centres in the United States to assess adherence to quality measures published by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).8 However, these were not comparable to a nationwide audit in a country with nearly 50 million inhabitants and with most IBD units predominantly located in the public health system.

Therefore, this study aimed to describe the implementation of a nationwide programme for IBD unit certification, the so‐called certification of inflammatory bowel disease units (CUE) programme of GETECCU. A secondary objective was to report the perception of IBD professionals on the usefulness of the evaluation programme.

METHODS

This is a descriptive study evaluating the implementation of a nationwide programme for IBD units certification based on compliance with the 53 selected QI (18 related to structure, 32 to process, and 3 to results) (legal deposit: BI‐1125‐2016) previously published by GETECCU (Table S1).6

The certification process

The project was one of the strategic lines of GETECCU and discussed by the committee that designed that project. It was presented to all GETECCU members in order to subscribe to it. IBD units voluntarily applied for certification. Once an IBD unit applied, an initial visit to the centre was performed to ascertain the level of compliance with all the indicators and establish an action plan. Once a unit considered it was ready for the audit, a mock audit supported by GETECCU was carried out within approximately 5 months from the first visit. An independent auditor performed the mock audit. After the mock audit, a confidential report was sent by the same independent auditor to the IBD unit to find out if they are now ready for the official audit. Two months later, an official audit was carried out by an external independent agency called Bureau Veritas, a global leader company in inspection, audits, and certification for over 30 years (https://www.bureauveritas.es). The final audit consisted of a 2‐day visit to the unit with an exhaustive review of all selected indicators. This audit included the evaluation of the structure of the institution (gastroenterology, surgery, endoscopy, and radiology departments), the review of all protocols, and the assessment of their compliance through the review of medical records. It also included an interview with all the members of the multidisciplinary team, including nurses and surgeons, a review of their curriculum vitae, and, finally, a detailed random evaluation of 40 medical records of different clinical scenarios (patients in remission, mild or severely active disease, post‐surgical setting, hospitalised, pregnant, under cancer surveillance programme, etc.). If a centre has a referral surgery hospital and has an official agreement with that hospital and it is verified in the medical records that all surgical patients are systematically sent to referral, the standard is considered to be correct. The condition must be that the referral centre has previously demonstrated certification.

After the audit, the independent auditor emitted a verdict with a detailed report, including the degree of compliance with the QI. If compliance exceeded 90%, the unit was given the rating “excellence”, and the unit has to be re‐certified in 3 years. If 80%–90% compliance was achieved, the Unit was qualified as “advanced”, and must be re‐certified in 2 years. In those cases with less than 80% compliance, the unit was not awarded the certification, but GETECCU compromised to help the IBD unit with an action plan to improve the missing indicators. The unit was allowed to apply again for the certification after a minimum six‐month period.

Finally, an official act of certification delivery was held in which regional health system managers, hospital directives, and patients’ associations (called ACCU in Spain, https://accuesp.com) were invited. There was coverage of the delivery act by both local and national media. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the process.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the certification process

Assessment of certification

The number and percentage of IBD units that achieved certification (grouped as advanced and excellent) among all those that applied, was evaluated. The percentage of the Spanish population covered by the certified IBD units was analysed; this process consisted of calculating the health population area of all certified IBD units and dividing by the Spanish population. The compliance rate with each QI was also analysed in all the units that have achieved the certification.

To evaluate the professional’s perception of the certification programme, gastroenterologists participating in the programme fulfilled a questionnaire after the certification process. The questionnaire included eight items regarding the contribution of the certification process to the care provided to IBD patients, with answers given on a Likert scale from 1 to 10 points (10 being the highest score). Two questions assessing future areas for improvement of the programme were open‐ended. The impact of the CUE programme in local and national media was also evaluated.

Results of certified IBD units are shown in percentages. Results of the questionnaire are shown in mean and standard deviation.

RESULTS

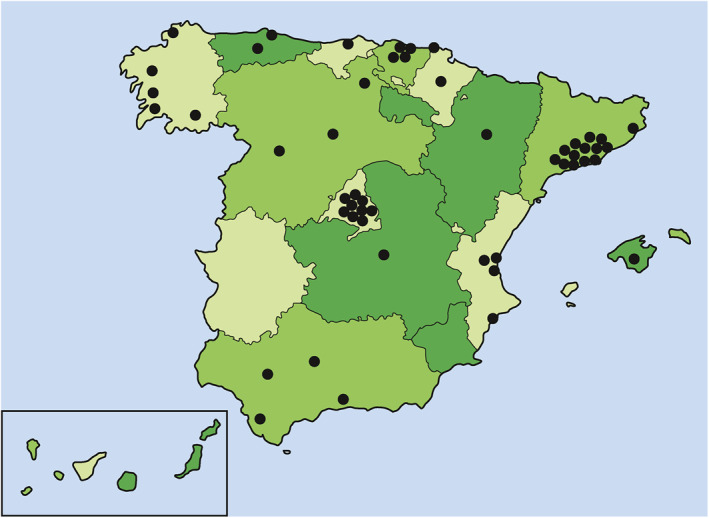

The CUE programme started in 2017. As of January 2021, 66 Spanish IBD units adhere to the certification programme nationwide, of which 53 have already been audited. As shown in Figure 2, 30 (56%) IBD units evaluated in our country achieved a certification grade of excellence, and 21 (40%) a certification grade of advanced. The geographical location of certified IBD units is shown in Figure 3. The certified IBD units are distributed among 13 of the 17 regions in our country. The most populated areas in Spain, such as Catalonia and Madrid (where the two biggest cities Barcelona and Madrid are located), were the regions with a higher number of certified units, although the distribution was relatively homogeneous throughout the country. There are four regions (Extremadura, La Rioja, Murcia, and Canary Islands) without certified units, although the first two are less populated regions of Spain. The 51 certified IBD units cover a population of 18.157.258 inhabitants, which represents 38.3% of the Spanish population according to data obtained from the national statistics institute (https://www.ine.es).

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of inflammatory bowel disease units audited that achieved excellence, advanced degree, or did not pass the certification process

FIGURE 3.

Geographically distribution of certified inflammatory bowel disease units in Spain

To date, 13 units are in the certification programme’s first steps (eight have completed the first visit, and five have completed the practice audit). Most of these units applied to the CUE programme during the COVID‐19 pandemic, and it is expected that they will be audited within the following months.

Detailed evaluation of the 53 selected QI showed that 40 QI were achieved in more than 90% of the units. There were two QI that were reached by less than 50% of the units; one was related to the written report of the information given to the patients about the potential risks of biological and immunosuppressant drugs in the clinical records, and the other was related to the performance of at least 10 ileoanal pouch surgeries within the previous year. The percentage of QI achieved per each question is shown in Table S1.

The first 40 IBD units audited answered a questionnaire to evaluate the perceptions on and the satisfaction with the CUE programme. The results are shown in Table 1. The results showed a high satisfaction rate with the CUE programme, with an average score of 8.5, out of 10; scores were over eight in all questions. Regarding the open questions concerning future issues for the improvement of the programme, the more demanded ones were to give more weight to paediatric transition and nutritional support for patients.

TABLE 1.

Results from the satisfaction questionnaire among audited IBD units

| Questions | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Has the certification process of my IBD unit contributed or will contribute to standardize the care of my patients? | 8.37 (1.37) |

| Has this process contributed or will contribute to improving the quality of care offered to my patients? | 8.48 (1.65) |

| Has this process helped to give value to the role of the nurse in my centre? | 8.57 (2.64) |

| Has the certification process met my expectations? | 8.33 (1.16) |

| Have the previous training and the two preparation visits been valuable and flexible? | 8.17 (1.85) |

| Has the audit been useful to identify areas for improvement? | 9.03 (0.95) |

| Has the award ceremony contributed to highlighting the IBD unit within the hospital? | 8.93 (1.21) |

| Would you recommend joining the program to a colleague from another hospital? | 9.20 (0.75) |

Abbreviation: IBD, Inflammatory bowel disease.

Since the start of the CUE programme, every time an IBD unit achieved the certification, an official act of certification delivery was held, and a press release was written and sent to the local and national media. Their main messages were about the importance of early diagnostic and treatment of IBD, the role of multidisciplinary teams, the need for monitorisation, and the relevance of quality of care in IBD. At the end of 2020, the total number of impacts in the media amounted to 437. Of them, 36% were published in specialised health media and 64% in general media (42% national and 58% local).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest nationwide study to date which provides evidence on the possibility of implementation of a certification programme for IBD units. With our results, based on more than 50 IBD units certified all over the country, almost 40% of the Spanish population can be attended with certified quality care in IBD. Further development of the programme has the potential to enable many Spanish IBD patients to be cared for in a certified IBD unit. This is likely to improve the overall quality of care for IBD patients.

One of the most valued targets in IBD treatment is for physicians to provide and patients to receive a high‐level quality of care.9 Nevertheless, this is not easy to achieve, especially in a nationwide public health system. There are reliable data showing huge differences in clinical care in IBD. A survey of patients with CD and UC in the United States demonstrated wide variation in practice between gastroenterologists in academic centres more specialised in IBD versus private practice and general gastroenterologists. Patients treated in academic centres received fewer steroids and more biological therapy when compared to private and general practices. Patients treated by gastroenterologists from academic centres were also more likely to be in remission, receive the flu vaccine, and have better quality of life.10 In a retrospective propensity‐matched scored study performed in a Canadian centre, the authors compared the quality of care in IBD before and after implementing an integrated model of care with a trained gastroenterologist specialist, specialised IBD nurses, registered dieticians, and a clinical psychologist. Patients treated within this model of care presented lower rates of IBD‐related hospitalisation, lower levels of corticosteroid dependence, and higher rates of immunomodulatory and biological use.11 The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) conducted a web‐based survey study of 4670 patients from 25 different European countries of which only 52% reported adequate access to care.12 Several other studies have identified variation in levels of care, and, against this background, a certification of IBD units could be a path for improving standards of care in IBD.13, 14

The best way to measure quality of care in IBD is by using QI. In response to the variation in care between practitioners, QI have been developed in both the United States15 and Canada16 for IBD management, with 11 QI in each case. We used the GETECCU QI for the certification programme, which consists of 53 QI based on Delphi methodology and which were further validated in our country by patients and nurses.6 Recently ECCO published their own 90 quality of care standards in IBD, with a high concordance with GETECCU’s QI,17 which supports the current validity of our QI. However, due to the rapid changes in IBD management, GETECCU is currently working on and updating the QI.

Some programmes in the United States audited IBD clinical practices to determine the quality of care, but their results mainly addressed private practice and reimbursement.10 Prospective data is aggregated in a central database and used to generate weekly audit and feedback reports for the participating centres. These reports are reviewed by the sites, and modifications are made to processes to improve outcomes. Involvement in this programme resulted in an increase in remission rates from 55% to 75% over the past few years.15, 18

A well‐designed nationwide study evaluating the quality of care in IBD has been performed in New Zealand. The programme consisted of three phases, the third being an audit of key aspects of IBD care. However, the audit, which was performed in 14 centres in contrast to ours, was more focused on validating the role of nursing than evaluating the global aspects of an IBD unit.19 Another nationwide study was performed in Australia. It consisted of a two‐phase programme, a cross‐sectional survey completed by the physicians, and a clinical audit assessing organisational resources, clinical processes, and outcome measures. The main difference with the Spanish programme was that in Australia only hospitalised IBD patients were audited, while in the GETECCU programme all groups of patients (including outpatients) were evaluated in the audit. Results were rather unexpected because the authors concluded that only one hospital met the standards for multidisciplinary IBD care.20

In Europe, the National UK IBD audit programme was established with the aim of improving the quality and safety of care for people with IBD throughout the UK. The first round of UK‐wide audit took place in 2006 with another four rounds in the following years and has shown substantial improvements in care over time. This complete programme endorsed by the Royal College of Physicians of London (www.rcplondon.ac.uk/ibd) has supported the development of national standards for IBD care and helped establish quality IBD care as a key component of local healthcare delivery.21, 22 To our knowledge, in difference with the Spanish program, the UK did not grant specific certifications to IBD units. Another difference is that our program is evaluated by a personalised audit performed onsite by an external association/company. This contrasts with the UK Audit, where each participating site submits their local data, and they are compared against a national benchmark (https://ibdregistry.org.uk/data‐submission‐framework/). Another nationwide programme known for evaluating IBD quality of care was implemented in Romania, with an audit of QI. However, the publication only included the programme’s protocol but not the results obtained after the audits nor the number of IBD units certified.23

Compared with other diseases with higher economic costs, IBD has limited media visibility and social media for society.24 For this reason, some other groups like the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America try to give value and importance to IBD in economic terms.25 We hope that giving a higher impact of the disease in the media and showing the importance of IBD units for society will help attract future IBD stakeholders.

There are, however, various limitations in our programme. First, adherence to the programme is voluntary. Furthermore, the results obtained in the satisfaction questionnaire could be biased, because they were answered just after certification, this being a moment of great optimism in the unit. Finally, our results could be difficult to extrapolate to other countries with different or more private healthcare systems due to Spain’s predominantly public health care system.

On the other hand, our study has several strengths. The main one is the external evaluation by an independent agency specialised in certification. The quality of the certification programme is based on QI that have been designed with Delphi methodology and previously published by our Medical Society.6 Another strength is the homogeneity of the programme all over our country, which is an opportunity for a patient with IBD located anywhere in the national territory to be treated with the same quality standards.

In conclusion, CUE is the largest nationwide certification programme for IBD units reported to date. More than 90% of IBD units that adhered to the programme achieved the certification. The support of patient associations and managers is essential for giving value to this type of project. This programme has increased IBD and GETECCU visibility in our country. This is probably the first step towards homogenising IBD assistance all over the country.

FUNDING

AbbVie sponsored the CUE programme. AbbVie had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Manuel Barreiro‐de Acosta has served as a speaker, consultant, and advisory member for or has received research funding from MSD, AbbVie, Janssen, Kern Pharma, Celltrion, Takeda, Gillead, Celgene, Pfizer, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, Adacyte, and Vifor Pharma. Ana Gutiérrez has served as a speaker, a consultant, and advisory member for or has received research funding from MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical. Yamile Zabana: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and consulting fees of Abvvie, Adacyte, Almirall, Amgen, Dr Falk, FAES Pharma, Ferring, Jannsen, MSD, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda, and Tillots. Belén Beltrán has served as a speaker, or has received research or education funding or advisory fees from MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Takeda, Ferring, Otsuka, and Amgen. Xavier Calvet: has received grants for research and fees for advisory boards and has given lectures for Abott, MSD, Vifor, Takeda, Pfizer, Janssen, and Allergan. María Chaparro has served as a speaker, or has received research or education funding or advisory fees from MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, and Tillotts Pharma. Eugeni Domènech: has served as a speaker, or has received research or education funding or advisory fees from Samsung, MSD, AbbVie, Takeda, Kern Pharma, Pfizer, Janssen, Celgene, Adacyte Therapeutics, Roche, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Tillots, Thermofisher, Grifols, Gebro, and Gilead. Maria Esteve: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support, and consulting fees of Abvvie, Ferring, Jannsen, MSD, Otsuka, Pfizer, Takeda, and Tillots. Julian Panés has received financial support for research: AbbVie MSD and Pfizer; lecture fee(s): AbbVie, Ferring, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, and Theravance; consultancy: AbbVie, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Ferring, Galapagos, Genentech, GoodGut, GSK, Janssen, Mirum, Origo, Pandion, Pfizer, Progenity, Takeda, Theravance, and Wasserman. Javier P. Gisbert: has served as a speaker, a consultant, and advisory member for or has received research funding from MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Vifor Pharma. Pilar Nos has served as a speaker, a consultant, and advisory member for or has received research funding from MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Faes Farma, Tillotts Pharma, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material 1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Javier Santiago, Jesús Martín, Bureau Veritas, patient’s associations (ACCU), and all IBD units adhered to the programme.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: Manuel Barreiro‐de Acosta and Pilar Nos. Analysis and interpretation of data: Manuel Barreiro‐de Acosta, Ana Gutiérrez, and Yamile Zabana. Drafting of the manuscript: Manuel Barreiro‐de Acosta, Ana Gutiérrez, Yamile Zabana, and Pilar Nos. Members of Steering Committee Xavier Calvet, María Chaparro, Eugeni Domènech, Maria Esteve, Julian Panés, and Javier P. Gisbert. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Manuel Barreiro‐de Acosta, Ana Gutiérrez, Yamile Zabana, Belén Beltrán, Xavier Calvet, María Chaparro, Eugeni Domènech, Maria Esteve, Julian Panés, Javier P. Gisbert, and Pilar Nos. Approval of the final manuscript: Manuel Barreiro‐de Acosta, Ana Gutiérrez, Yamile Zabana, Belén Beltrán, Xavier Calvet, María Chaparro, Eugeni Domènech, Maria Esteve, Julian Panés, Javier P. Gisbert, and Pilar Nos. Guarantor of the article: Manuel Barreiro‐de Acosta and Pilar Nos.

Barreiro‐de Acosta M, Gutiérrez A, Zabana Y, Beltrán B, Calvet X, Chaparro M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease integral care units: evaluation of a nationwide quality certification programme. The GETECCU experience. United European Gastroenterol J. 2021;9(7):766–772. 10.1002/ueg2.12105

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available at https://geteccu.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chaparro M, Barreiro‐de Acosta M, Benítez JM, Cabriada JL, Casanova MJ, Ceballos D, et al. EpidemIBD: rationale and design of a large‐scale epidemiological study of inflammatory bowel disease in Spain. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819847034. 10.1177/1756284819847034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunet E, Vela E, Melcarne L, Clèries M, Pontes C, Llovet L, et al. Time trends of Crohn’s disease in Catalonia from 2011 to 2017. Increasing use of biologics correlates with a reduced need for surgery. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):2896. 10.3390/jcm9092896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beard JA, Click BH. The burden of cost in inflammatory bowel disease: a medical economic perspective. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2020;36(4):310–6. 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louis E, Dotan I, Ghosh S, Mlynarsky L, Reenaers C, Schreiber S. Optimising the inflammatory bowel disease unit to improve quality of care: expert recommendations. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9(8):685–91. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor M, Bager P, Duncan J, Gaarenstroom J, Younge L, Détré P, et al. N‐ECCO Consensus statements on the European nursing roles in caring for patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(9):744–64. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvet X, Panés J, Alfaro N, Hinojosa J, Sicilia B, Gallego M, et al. Delphi consensus statement: quality indicators for inflammatory bowel disease comprehensive care units. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(3):240–51. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waje‐Andreassen U, Nabavi DG, Engelter ST, Dippel D, Jenkinson D, Skoda O, et al. European Stroke Organisation certification of stroke units and stroke centres. Eur Stroke J. 2018;3(3):220–26. 10.1177/2396987318778971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feuerstein JD, Castillo NE, Siddique SS, Lewandowski JJ, Geissler K, Martinez‐Vazquez M, et al. Poor documentation of inflammatory bowel disease quality measures in academic, community, and private practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(3):421–28. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strohl M, Gonczi L, Kurt Z, Bessissow T, Lakatos PL. Quality of care in inflammatory bowel diseases: what is the best way to better outcomes? World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(22):2363–72. 10.3748/wjg.v24.i22.2363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver KN, Kappelman MD, Sandler RS, Martin CF, Chen W, Anton K, et al. Variation in care of inflammatory bowel diseases patients in Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America partners: role of gastroenterologist practice setting in disease outcomes and quality process measures. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(11):2672–7. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peña‐Sánchez JN, Lix LM, Teare GF, Li W, Fowler SA, Jones JL. Impact of an integrated model of care on outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: evidence from a population‐based study. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(12):1471–9. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lönnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, Hommes D, Bell C, Avedano L. IBD and health‐related quality of life ‐‐ discovering the true impact. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(10):1281–6. 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson BD, Con D, Liew D, De Cruz P. Clinicians’ adherence to international guidelines in the clinical care of adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(5):536–42. 10.1080/00365521.2017.1278785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ananthakrishnan AN, Kwon J, Raffals L, Sands B, Stenson WF, McGovern D, et al. Variation in treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases at major referral centers in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(6):1197–200. 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melmed GY, Siegel CA, Spiegel BM, Allen JI, Cima R, Colombel JF, et al. Quality indicators for inflammatory bowel disease: development of process and outcome measures. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(3):662–8. 10.1097/mib.0b013e31828278a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen GC, Devlin SM, Afif W, Bressler B, Gruchy SE, Kaplan GG, et al. Defining quality indicators for best‐practice management of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(5):275–85. 10.1155/2014/941245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiorino G, Lytras T, Younge L, Fidalgo C, Coenen S, Chaparro M, et al. Quality of care standards in inflammatory bowel diseases: a European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] position paper. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(8):1037–48. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah R, Hou JK. Approaches to improve quality of care in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(28):9281–5. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hackett R, Gearry R, Ho C, McCombie A, Mackay M, Murdoch K, et al. New Zealand National Audit of outpatient inflammatory bowel disease standards of care. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020;13:285–92. 10.2147/CEG.S259790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massuger W, Moore GTC, Andrews JM, Kilkenny MF, Reyneke M, Knowles S, et al. Crohn’s & Colitis Australia inflammatory bowel disease audit: measuring the quality of care in Australia. Intern Med J. 2019;49(7):859–866. 10.1111/imj.14187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mortier K, Protheroe A, Murray S. Improving the quality of care for people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): results of a national audit. Future Hosp J. 2015;2(Suppl 2):s11. 10.7861/futurehosp.2-2s-s11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alrubaiy L, Arnott I, Protheroe A, Roughton M, Driscoll R, Williams JG. Inflammatory bowel disease in the UK: is quality of care improving? Frontline Gastroenterol. 2013;4(4):296–301. 10.1136/flgastro-2013-100333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negreanu L, Bataga S, Cijevschi Prelipcean C, Dobry D, Diculescu M, Dumitru E, et al. Excellence centers in inflammatory bowel disease in Romania: a measure of the quality of care. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2014;23(3):333–7. 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.233.ln1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis JR, Chen L, Higginbotham P, Nowell B, Gal‐Ley R, Willing J, et al. Social media for arthritis‐related comparative effectiveness and safety research and the impact of direct‐to‐consumer advertising. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):48. 10.1186/s13075-017-1251-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park KT, Ehrlich OG, Allen JI, Meadows P, Szigethy EM, Henrichsen K, et al. The cost of inflammatory bowel disease: an initiative from the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(1):1–10. 10.1093/ibd/izz104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available at https://geteccu.org.