Abstract

Background:

Population aging is a social and economic concern for China. It is essential to understand types of social support networks available to elderly people living in China.

Objectives:

The aim of this research was to identify network types among Chinese older adults and to examine the differential relationship of the network types, health outcomes and health-related behaviors.

Methods:

Secondary analysis of data compiled by the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (n = 9749) was extracted. Network types were derived through latent class analysis with Mplus 6.12 software. Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics, one-way ANOVA, multiple logistic regression and path analysis.

Results:

Four types of social networks were identified, these included private (16%), non-couple-focused (15%), couple-focused (47%) and diverse (22%). Compared with elders belonging to other networks, elders in diverse network possessed the healthiest status and the highest health-related behaviors score. Health-related behaviors played a role in mediating social network types to health outcomes was identified. Findings were aligned to the conceptual model pathway proposed by Berkman (2000).

Conclusion:

The findings demonstrate that types of social networks for elders are significantly correlated to health-related behaviors and health outcomes. Detail and understanding of the correlations are useful to inform healthcare practice and policy and to assist the development of appropriate interpersonal interventions.

Keywords: China, health outcomes, health-related behaviors, path analysis, social support network types

Introduction

Population aging is becoming more and more burdensome societally and economically for many countries in the World, including China. According to the Sixth National Population Census data revealed by the national bureau of statistics of the People’s Republic of China, the number of people aged 60 years and older was more than 99 million in 2010, which represented 15% of the total population (National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, 2010). People aged 65 and above in China will reach 0.177 billion in 2020 (National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, 2010). Since China is currently in the active period of social transition and economic change, Chinese older adults are often more vulnerable to the influence of various social context factors.

A social network is characterized as a composite of the structure, function, and quality of the social relations in which individuals are embedded (Park, Smith, & Dunkle, 2014). The recognition of differences in three network dimensions led to the development of social support network typology (Wenger & Tucker, 2002). Researchers have used social network typology as an approach to derive groups of people with a common set of social ties (Doubova Dubova, Perez-Cuevas, Espinosa-Alarcon, & Flores-Hernandez, 2010). Instead of considering specific structure or support measures with health outcomes, this pattern-centered approach can be allowed to synthesize the complex network arrangements as a unit.

It is well established that older adults throughout the aging journey manage a wide range of challenges on a psychological and physical level (Chen & Silverstein, 2000). Many of these could be contributed to the impact of social support network arrangements (Phillips, Siu, Yeh, & Cheng, 2008). The overall effects of these arrangements influence health status and health-related behaviors of the elderly. The aims of this study were to use the conception of social network typology to draw a robust picture of social arrangement situations of Chinese elders and, to empirically test a model of association, linking older adults’ health status, health-related behaviors, and social support network through path analysis.

Background

Different types of social networks

Previous studies have showed that there are different types of social networks in older adults across Europe, Japan, Israel, and the USA. The four main social network types are found to be clustered as: ‘diverse’, with broad sources (family, friends, neighbors, etc.) of supports, and frequent participation in social activities; ‘friends’, focused on friends with little concern to family and social activities; ‘family’, focused on family with little concern to friends and social activities, and ‘restricted’ isolated and low social activities (Fiori, Smith, & Antonucci, 2007; Flori, Antonucci, & Cortina, 2006; Litwin & Shiovitz-Ezra, 2011).

However, after more than forty years of social network typology research, there remains a lack of a clear definition and consensus regarding social network typology within non-Western countries. For example, although similar network types have been identified, researchers in Japan identified an additional type, classified as ‘married and distal’ (Fiori, Antonucci, & Akiyama, 2008) and Park et al. (Park et al., 2014) classified a type as ‘couple-focused’ instead of ‘family’ in South Korean older adults. Furthermore, in Hong Kong a new type emerged and was classified as ‘distant family’ describing a focus on close distant kinship (Cheng, Lee, Chan, Leung, & Lee, 2009). An interesting and new type has emerged to described Chinese immigrants living in Wales, UK based on ‘multi-generational household’ factors (Burholt & Dobbs, 2014).

Association with health indicators

Effects of social networks typology on the health of older adults has been increasingly discussed and includes physical health status (Li & Zhang, 2015; Litwin, 2003), mortality (Ivan Santini et al., 2015), and subjective mental health (Cheng et al., 2009; Flori et al., 2006). In particular, older adults in larger social networks experience longer life expectancy, better health status and subjective well-being, whereas older people with restricted networks decline in their overall health status.

As for health-related behaviors, which is also vital to one’s health status, is known as a range of personal or group actions that related to health and disease. In relation to the Social Convoy Model proposed by Berkman et al (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000), health-related behaviors are considered as the mediator on the pathway from social networks to health since behaviors are influenced by social resources which can enhance or inhibit access to opportunities for social interaction such as social engagement, then subsequently linked to one’s health status. There is evidence to support a link between social network typology and the adoption of health-related behaviors. For example, there is a correlation between the existence of health-promoting behaviors and physical and cognitive function. Health-related behaviors were found to play a significant role in mediating the relationship between social support and older adults’ multi-dimensional health (Thanakwang & Soonthorndhada, 2011).

In summary, the direct and indirect associations between social networks, health status and health-related behaviors remain partially explored and elusive in the research literature. This can be partially attributed to the fact that previous studies have focused on one or two characteristics of social network indicators (Yun, Kang, Lim, Oh, & Son, 2010) instead of a more united measure (Fiori et al., 2008). On the other hand, the relationship between social networks and health may also be sensitive to varied sociocultural contexts (Litwin, 2006). Furthermore, there is a need to explore if the typologies developed in Western countries can be replicated and aligned to non-Western countries including China.

Research questions

This study addresses two research questions and include:

-

1

Is the pattern of social networks identified among older adults in China similar to those found in other countries?

Previous research findings on general network types and specific unique type have emerged in non-Western countries and point to a potential difference in the structure and function of Chinese older adults’ networks. Based on contemporary changes in social relations of elders in China, we expect to find some variations in the forms of network types. This variation could be one or more different types or just slightly different characteristics to those previously established.

-

2

Is there an association between social support network typology, health status and health-related behaviors in Chinese elders?

Following the conceptual framework of the Social Convey Model, we hypothesized that health-related behaviors play a moderating role on social network typologies and health outcome.

Methods

Data

Data from the 2011–12 survey of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) were used to undertake a secondary analysis. CLHLS is the first and largest Nation wide longitudinal survey, concerning older adults in China. Data was extracted using representative stratified probability sampling. The survey, sponsored by the China Natural Sciences Foundation and the Hong Kong Research Grants Council and partnered with NIA/NIH Grants, was designed specifically to study the determinants influencing healthy longevity of Chinese people. The study provides important information about the health of older people living in China. The 2011–12 survey conducted face-to-face interviews using a standardized protocol with up to 10,188 individuals among which 15% are centenarians. The survey randomly selected 631 counties and cities in 22 provinces in mainland China. The data obtained is recognized to be of high quality (Zeng, Feng, Hesketh, Christensen, & Vaupel, 2017). In the current paper, we retained only respondents aged 60 and over with complete information on social network measures (n = 9749). Socio-demographic characteristics and health indicators of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |

| Age (60–114), M (SD) | 85.82 (11.36) |

| Gender (Female), % | 55.02 |

| Marriage, % | |

| With spouse | 38.15 |

| Others | 61.85 |

| Educational level, % | |

| Illiteracy | 58.18 |

| With 1+ year education | 41.82 |

| Occupation (Farmer), % | 68.95 |

| Residence place, % | |

| City & Town | 47.36 |

| Rural | 52.64 |

| Household income in ¥, % | |

| ≤10,000 | 42.76 |

| >10,001 | 57.24 |

| Living situation, % | |

| With household member(s) | 82.41 |

| Alone | 15.61 |

| In nursing home | 1.98 |

| Chronic illness, % | |

| No | 39.02 |

| Yes | 60.98 |

| Health indicators | |

| ADL (0–6), M (SD) | 0.77 (1.62) |

| IADL (0–8), M(SD) | 3.33 (3.21) |

| MMSE (0–30), M(SD) | 22.56 (5.83) |

| Subjective well-being (0–28), M(SD) | 18.62 (4.69) |

| Self-rated QoL (0–4), M (SD) | 2.25 (0.81) |

| Self-rated health (0–4), M (SD) | 2.56 (0.92) |

| Health-related behavior (0–30), M (SD) | 17.08 (3.88) |

Variables

Social network typology

The social network types were derived from three dimensions of individual’s social relationships measures: structural, functional, and appraisal aspects of supportive relations. In total, we included fourteen characteristics, which are reported to be influencing factors regarding social networks of older people (Burholt & Dobbs, 2014; Li & Zhang, 2015) that were available in CLHLS data.

Structural support was measured by five structure variables: number of family members (in one household) aged 18 and over, number of close children (live with or frequent visit), number of close siblings (live with or frequent visit), frequency of playing cards and/or mahjong, and frequency of organized social activities. Responses about participation in latter two entries were given on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (almost every day).

For functional characteristics, functional support received was constructed from three relevant questions: (1) to who do you usually talk most frequently in daily life? (2) To who do you talk first when you need to share some of your thoughts? (3) Who do you first ask for help when you have problems/difficulties?

Ten categories of relationships provided the emotional and instrumental support functions above were asked to be picked up to ranking the top three for which scored three, two, and one point respectively. The first was spouse, the second to seventh were classified as relatives, the eighth was friend/neighbor, and the last two were others. The summary score of each classified category represented the functional support received by the participant. Functional support provided by the participant to each network member was measured with the condition of whether the elders do house chores by self and give financial help to others.

Appraisal component that asked whether the individual was occupied in household chores in daily life and if provided financial support to other family members.

Socio-demographics

The controlled covariates included age (60–114), gender (men/women), marriage (with spouse/others), educational level(illiteracy/with more than one-year education), occupation before retirement (farmer/others), residence (city & town/rural), household income annually (≤10,000/>10000), living arrangement (living alone/with family members/in a nursing home), whether suffered from chronic illness (no/yes), including hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, bronchitis/emphysema/pneumonia/asthma, tuberculosis, cataract, glaucoma, cancer, prostate tumor, gastric or duodenal ulcer, Parkinson’s disease, bedsore, arthritis, dementia, epilepsy, etc.

Health indicators

The dependent variables in the analysis were physical health, subjective well-being, and health-related behaviors.

Physical health was measured on three separate constructs: Activities of Daily Living (ADL), Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), and cognitive ability. ADL score (0–6) was counted by the limit number of six specific activities of daily living including bathing, dressing, toilet, eating, indoor transferring and continence. IADL score (0–8) that asked how many tasks were impaired in performing activities of visiting neighbor, going shopping, cooking a meal, washing clothes, walking continuously, lifting a weight of 5 kg, continuously crouching and standing up three times, and taking public transportation. Cognitive ability (0–30) was measured with the Chinese version (Zhang, 2006) of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) with higher scores indicating better cognitive ability.

Subjective well-being was indicated by variables of personality, self-rated health and self-rated Quality of Life (QoL). Personality was assessed by four positive feelings (‘Do you always look on the bright side of things?’, ‘Do you like to keep your belongings neat and clean?’, ‘Can you make your own decisions concerning your personal affairs?’, ‘Are you as happy as when you were younger?’) and three negative feelings (‘Do you often feel fearful or anxious?’, ‘Do you often feel lonely and isolated?’, ‘Do you feel the older you get, the more useless you are?’) which were rated on a five-point frequency scale of 0 (never) to 4 (always) (Smith, Gerstorf, & Li, 2008). Particularly reversed coded for the negative items, a range of 0 to 28 was the sum of all seven items with a higher score indicating more positive personality. Self-rated health and self-rated QoL were assessed separately by questions of ‘How do you rate your health at present?’ and ‘How do you rate your life at present?’ on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (very bad) to 4 (very good).

Thirty entries representing six domain of health-related behaviors were employed: (1) Adequate Nutrition (‘Please tell us the staple food you eat(mixed type or not)’, ‘How often eat fresh fruit?’, ‘How often eat vegetables?’, ‘What kind of grease do you mainly use for cooking?’, ‘What kind of flavor do you mainly have?’, ‘How often eat meat/fish/eggs/food made from beans/salt-preserved vegetables/garlic/milk products/nut products/mushroom or algae/vitamins/medicinal plants at present?’, ‘How often drink tea at present?’, ‘What kind of water usually drink?’), (2) Exercise (‘Do you exercise or not at present?’, ‘Do you grow vegetables & do other field work at present?’), (3) Use Of Health Services (‘Do you get adequate medical service at present?’, ‘Do you have regular physical examination once every year?’), (4) Sleep (‘How about the quality of your sleep?’), (5) Promoting Mental Health (‘Do you do garden work?’, ‘Do you read newspapers/books at present?’, ‘Do you raise domestic animals or pets at present?’, ‘Do you watch TV or listen to radio at present?’, ‘Do you travel beyond home county or city in the past two years?’), (6) Bad Habits (‘Do you smoke or not at present?’, ‘Do you drink excessively or not at present?’). We dichotomized the answers of these items to reflect whether the individual had positive behavior with 0 (no) and 1 (yes), except that eating salt-preserved vegetables and the items in bad habits were reversed coded for a uniform scored direction. Finally, an overall health-related behaviors index with a range of 0–30 was measured.

Analysis

For the first step, as described in previous studies, the K-means cluster analysis was often applied on a range of social network characteristics to form the network types (Litwin & Shiovitz-Ezra, 2011). While in the current paper, we performed Latent Class Analysis (LAC) which was relatively novel in social network typology research to examine the respondents’ social relationships. Instead of a priori assumptions, LCA is a form of mixture modelling with data-driven techniques, whereby a set of associated observed responses, for example social relationships indicators, can be used to identify underlying latent subtypes. Individuals are clustered to homogenous groups with similar profiles based on a set of calculated indexes. Fit of models with different number of classes in this study was assessed by the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Entropy. The best fitting model was preferred with the lowest BIC and highest entropy. Analyses for LCA were performed in Mplus Version 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012).

After identification of the social network typology of individuals, data was imported to IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) for bivariate analyses to explore the differences of socio-demographics and health indicators between the identified network types as well as the validity of the subclasses. Specifically, two-tailed chi-square statistics were taken for categorical variables, and univariate tests for continuous variables. Spearman’s correlations were used to examine the linear associations between ADL score, IADL score, cognitive ability, personality, self-rated health, self-rated QoL, health-related behaviors and social network types. All the potential predictive factors that showed significant associations with social network types at a nominal level of p < 0.05 were included in the further analysis. All tests were two-tailed.

A path analysis enables us to do the simultaneous modeling of several related regression relationships, thus was finally performed to map out the associations between social support network typologies, health outcomes and health-related behaviors. Mplus version 6.12 was used for modeling the hypothesized associations and path analysis of all participants. Finally, by employing 10,000 samples, we used bootstrapping to test the significance of the mediated effects and produce their confidence intervals (MacKinnon, 2008).

Results

Social network typology

Partly consistent with previous research, a four class latent model represented the optimal fit depending on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC = 529,227; versus 542,038 for a three-class model, and 55,2831 for a five-class model). Entropy of the four class model was 0.90, indicating a reasonable delineation of classes (Celeux & Soromenho, 1996). The characteristics of these four network types and their relative frequencies are showed in Figure 1 by the standardized t-scores of the subgroup means.

Figure 1.

The standardized t-scores of variable means.

Constituting about 16.46% of the sample, the diverse type has the largest number of close siblings, highest level of support exchange with network members like spouse and friends/neighbors, highest frequency of attending social participation, and relatively most positive appraisal to their own support networks. It was distinguished by the most balanced and diverse social resources, which manifested in almost every value was above the zero (average). Especially, these older adults with diverse networks were the only type that were available to be the support providers to their family. Couple-focused type comprised the largest portion of the sample (47.00%), which exhibits highest values in numbers of household members, close children and functional support from spouse, while on the other hand, it also showed that relatively lowest values for other variables related to social activities or friends/neighbors, indicating people with this network type were least likely to participant in social engagement outside of family members. By comparison, non-couple-focused type accounted for 14.70% of the samples, in which 80% of individuals didn’t have spouse. The source of support were provided by other family members (i.e. children), whereas particularly not spouse. Finally, the private type was characterized by having the restricted size of network numbers, the relatively least contact with siblings and close proximity to their children. They reported little contact with and support from children, other relatives, and social participation. The only source of support was from community’s formal help.

Network types differences

Descriptive information about the socio-demographics and health indicators of these four network types is exhibited in Table 2.

Table 2.

Social support network typology differences by defined variables.

| Network typology |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Private N = 1605 (16.46%) |

Non-couple-focused N = 1433 (14.70%) |

Couple-focused N = 4582 (47.00%) |

Diverse N = 2129 (21.84%) |

Statistics |

| Socio-demographics | |||||

| Age, M (SD) | 85.89 (11.54) | 89.07 (11.69) | 88.07 (10.43) | 78.75 (9.81) | F = 422.979*** |

| Gender (female, %) | 51.28 | 64.20 | 60.56 | 39.74 | X2 = 317.715*** |

| Marriage (married, %) | 48.79 | 20.34 | 61.61 | 62.88 | X2 = 990.883*** |

| Educational level (illiteracy, %) | 57.46 | 65.38 | 66.80 | 35.37 | X2 = 623.674*** |

| Occupation (farmer) (%) | 69.86 | 66.74 | 75.02 | 56.93 | X2 = 205.861*** |

| Residence place (rural, %) | 52.02 | 48.22 | 57.51 | 45.61 | X2 = 185.588*** |

| Household income (≤10,000/year, %) | 50.34 | 44.80 | 43.52 | 34.50 | X2 = 149.469** |

| Living situation (%) | X2 = 18.369** | ||||

| With household member(s) | 83.58 | 84.88 | 81.38 | 82.08 | |

| Alone | 14.79 | 13.16 | 16.81 | 15.32 | |

| In nursing home | 1.63 | 1.96 | 1.81 | 2.61 | |

| Chronic illness (no, %) | 38.63 | 39.22 | 40.51 | 35.98 | X2 = 14.721 |

| Health indicators | |||||

| ADL (0–6), M(SD) | 1.25 (2.08) | 0.90 (1.8) | 0.80 (1.60) | 0.28 (0.97) | F = 114.081*** |

| IADL (0–8), M (SD) | 3.83 (3.42) | 3.98 (3.24) | 3.86 (3.13) | 1.38 (2.35) | F = 371.804*** |

| MMSE (0–30), M(SD) | 18.45 (3.62) | 21.23 (6.40) | 22.16 (4.49) | 27.18 (5.81) | F = 26.241*** |

| Personality (0–28), M (SD) | 17.84 (5.11) | 17.97 (5.06) | 18.24 (4.55) | 20.25 (4.05) | F = 8.876*** |

| Self-rated QoL (0–4), M (SD) | 2.12 (0.81) | 2.27 (0.84) | 2.26 (0.78) | 2.40 (0.89) | F = 15.524*** |

| Self-rated health (0–4), M (SD) | 2.38 (0.87) | 2.62 (0.93) | 2.60 (0.91) | 2.69 (1.01) | F = 20.660*** |

| Health-related behaviors (0–30), M (SD) | 15.68 (4.44) | 16.68 (3.65) | 16.64 (3.43) | 17.08 (3.88) | F = 27.767*** |

Note: (All are 2-tailed).

0.001

0.01

0.05.

People with diverse network were significantly younger than the other types, more likely to be males and married, live in city or urban areas. They were also less likely to be farmers before retirement or to be illiteracy, and seldom troubled with financial difficulties. Like individuals in the diverse type, the majority of individuals in couple-focused type were married and they reported low participation in community and social activities. They were low educated, farmers before retirement, lived in rural area. While for people with non-couple-focused type, they were the oldest group with large proportion of females. And half of older adults with private type were financial insufficiency. As reported in Table 2, seven health indicators shows statistically differed level among four network types. Overall, individuals in diverse type showed highest score of physical health, subjective well-being, and health-related behaviors, yet private type showed the lowest.

Correlations

Spearman correlations between potential predictive variables are shown in Table 3. The ADL and IADL scores were positively significantly correlated with each other, which confirming the consistency of them indicating physical health. Cognitive ability and personality had significantly negative correlations with ADL and IADL scores and significantly positive correlations with self-rated QoL and self-rated health. Health-related behaviors were significantly negatively correlated with ADL and IADL scores, positively correlated with cognitive ability, personality, self-rated QoL and self-rated health. All the study variables showed a significant correlations with social network types.

Table 3.

Spearman correlations for study variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ADL | – | |||||||

| 2. IADL | 0.654*** | – | ||||||

| 3. MMSE | −0.472** | −0.633** | – | |||||

| 4. Personality | −0.237** | −0.357** | 0.347** | – | ||||

| 5. Self-rated QoL | −0.002** | −0.035** | 0.092** | 0.341 ** | – | |||

| 6. Self-rated health | −0.100** | −0.194** | 0.140** | 0.341** | 0.431** | – | ||

| 7. Health-related behaviors | −0.229** | −0.362** | 0.423** | 0.338** | 0.231** | 0.194** | – | |

| 8. Social network types | −0.176** | −0.251** | 0.291** | 0.164** | 0.097** | 0.110** | 0.267** | – |

Note:

means correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

means correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed).

Path analysis

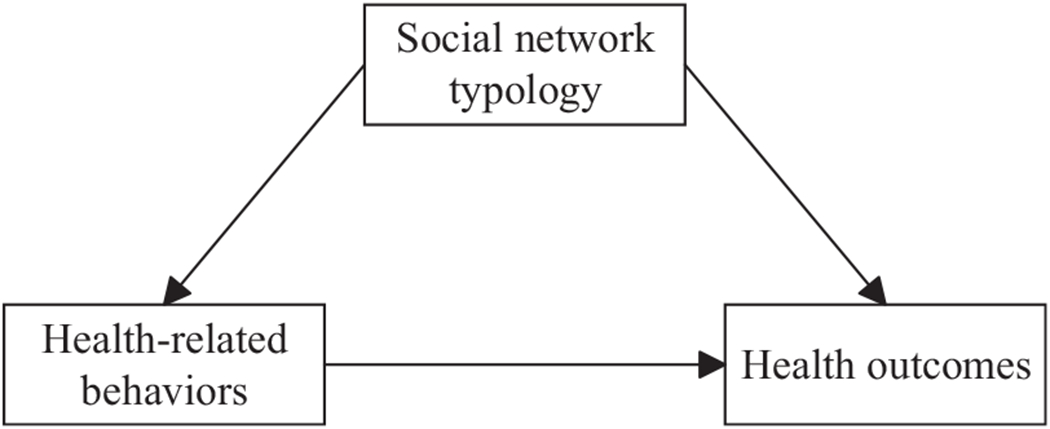

By social convey model, we expected health-related behaviors were the moderated media for social network types and health status, mediated by the relationships between social network types and health status that operate though health-related behaviors which can be showed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Theoretical model.

Thus, in order to answer the second research question, path analysis was further employed to test the hypothesized full model after controlling for the socio-demographic factors which were reported to be related to social support networks and health by connecting them to the endogenous variables. Models were examined for both the overall fit and for construct validity and reliability. The fitness estimation indicate a good fit: X2 = 1239.994***; The values of Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) were 0.998 and 0.994 respectively which are well over the recommended minimum value of 0.90, thereby indicating that the model has good fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.003 that is less than the recommended level (Hammervold & Olsson, 2012), indicating the validity of the measurement construct.

The Table 4 showed the final model obtained which indicated that the control variables did not confound the proposed model. Thus, the results of the path analysis suggested that social network typology had a direct effect on older adults’ multiple health indicators and health-related behaviors. The path from health-related behaviors to multiple health indicators was also significant, with high levels of health-related behaviors predicting more healthy status. The indirect/mediation effect and their associated 95% confidence intervals was displayed in Table 5. Combined with direct effect, the percentage of the mediating effect of social network types on multiple health indicators through health-related behaviors were 28.57, 32.66, 18.89, 28.19, 38.57, 37.50% of the total effects respectively.

Table 4.

Final model estimates of relationships.

| Dependent variables |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Social network types | Health-related behavior | ADL | IADL | MMSE | Personality | Self-rated QoL | Self-rated health |

| Age | −0.014*** | −0.060*** | 0.046*** | 0.152*** | −0.310*** | −0.058*** | −0.006*** | −0.002 |

| Gender (female = 0) | 0.019 | 0.030 | −0.115** | −0.545*** | 1.531*** | 0.192 | 0.029 | −0.081** |

| Marriage (married = 0) | 0.011 | −0.650*** | −0.081* | 0.097 | −0.356 | −0.401** | −0.036 | −0.064* |

| Educational level (illiteracy = 0) | 0.092** | 0.949*** | 0.039 | −0.157* | 0.944*** | 0.683*** | −0.002 | −0.014 |

| Occupation (farmer = 0) | 0.029 | 0.829*** | 0.155*** | 0.181** | 0.041 | 0.348** | −0.031 | −0.036 |

| Residence place (city = 0) | 0.043** | −0.614*** | −0.138*** | −0.143*** | 0.288* | −0.240** | 0.003 | 0.012 |

| Household income (≤10,000 = 0) | 0.082*** | 0.473*** | 0.069*** | 0.127*** | −0.118 | 0.174*** | −0.092*** | −0.048*** |

| Living situation (With household member(s) = 0) | 0.068** | −0.082 | 0.009 | 0.028 | −0.197 | −0.008 | −0.015 | 0.059* |

| Chronic illness | −0.03* | −0.013 | 0.187*** | 0.400*** | −0.337*** | −0.473*** | 0.071*** | 0.217*** |

| Social network types | 0.611*** | −0.140*** |

−0.235*** |

1.430*** |

0.507*** |

0.043*** |

0.054*** |

|

| Health-related behavior | −0.091*** | −0.186*** | 0.546*** | 0.326*** | 0.044*** | 0.040*** | ||

Note: Data are standardized regression coefficients.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Table 5.

Bootstrap analyses of indirect effects.

| 95% CI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathways to health indicators | Estimated | p | Lower | Upper |

| SNT→HRB→ADL | −0.056 | <0.001 | −0.063 | −0.048 |

| SNT→HRB→IADL | −0.114 | <0.001 | −0.128 | −0.100 |

| SNT→HRB→MMSE | 0.333 | <0.001 | 0.291 | 0.376 |

| SNT→HRB→personality | 0.199 | <0.001 | 0.172 | 0.226 |

| SNT→HRB→Self-rated QoL | 0.027 | <0.001 | 0.023 | 0.031 |

| SNT→HRB→Self-rated health | 0.024 | <0.001 | 0.020 | 0.029 |

Note: SNT = Social network types; HRB = Health-related behaviors.

Discussion

Compositions and prevalence of social network types

The multidimensional approach (Fiori et al., 2007) used in the present study offers a way to examine whether social network typology reported in other countries could be derived among Chinese older adults for the first time. In general, our findings proved that some common network types can be identified in a robust manner across different cultures and samples. Based on indicators of structural, functional and appraisal characteristics of social networks, we found a diverse network, a non-couple-focused network, a couple-focused network, and a private network type would emerge from the samples – which were partially consistent with previous research.

As predicted, we derived a diverse and a private type, which were consistent with those found in the majority of network typology studies. The diverse network was characterized by a large network, with many social ties, frequent contacts to children and participation in community groups. The characteristics of this network make it comparable to the diverse networks identified in Israel (Litwin, 2006) and the United States (Litwin, 2003). The private network type with relatively more restricted social relations, take up to 16.46% of the sample, which could suggest to some degree that Chinese older adults seem to have similar restricted social relations when compared to older adults in other Asian countries. For example, among older adults in Japan the restricted network type comprised about 15% of the sample (Litwin & Shiovitz-Ezra, 2011).

However, due to sociocultural milieus differences, some variations from earlier studies were also founded in this study. The first concern is that there seems no simple ‘friend-focused’ type which characterized by close bonds with friends and social activities instead of family was emerged in the Chinese elderly samples. It suggests to some degree that due to Chinese traditional social concept, older people would mostly rely on the family for the fulfillment of needs and it is not necessarily functional to seeking support from friends.

Another concern is that whereas other studies find one family type, we found two variations of the family network, that we called couple-focused and non-couple-focused type. Samples of Chinese older adults are most likely to belong to the couple-focused network, which comprised nearly half of the samples. On the one hand, it is in consistent with other network typology research on Asian older adults, including in Japan (Fiori et al., 2008) and Hong Kong (Cheng et al., 2009) where type of family network was the most prevalent type. While on the other hand, differed from previous family type, it was the spouse rather than other family members that seems provide the most source of support than other relatives to older adults in the couple-focused type. The non-couple-focused network type distinguished by a small proportion (14.7%) of samples was similar to ‘the distant family network’ derived from the elderly in Hong Kong (Cheng et al., 2009). Most of them remained single without a family stem, who had to rely on other relatives. Whereas older adults with this network type had little support from spouse, their overall health was still similar to those with the couple-focused network type due to other family members’ strong supports.

Socio-demographic differences of social network types

Considering the meaningful influences of cultural similarities and differences to the compositions and prevalence of social network types, the socio-demographics of individuals in the different network types also need to be discussed. For instance, people with non-couple-focused type were the oldest network type with large proportion of single female. This may relate to the fact that female is more likely than male to be survived among the oldest-old period (Zeng et al., 2017). Once a female in the nuclear family lose her husband, the alterative social support provided by siblings, cousins, and distant in-laws then play an important role in her lifetime.

Consistent with previous research on social-network types (Cheon, 2010; Litwin, 2001; Perkins, Subramanian, & Christakis, 2015), the youngest, most educated, males and married, live in city or urban areas individuals tended to be in the most diverse networks. However, individuals in the private network types were relatively young compared to those in the other network types. This unusual finding also showed in the restricted/unsupported network type in Japanese older adults (Fiori et al., 2008). One possible explanation for the results is that older adults tend to have more positive quality of intimate social relationships than younger adults (Löckenhoff, Costa, & Lane, 2008). These findings demonstrate that although private network type may be most common among the oldest people, it is to some point not the absolute condition.

In China, those with the lowest level of education, farmers before retirement, lived in rural area were in the couple-focused type. Since it represented the largest proportion of rural residents, this particularly high prevalence of couple-focused network in rural China may be associated with rapid urbanization over the last 30 years, which in China is associated with a decline in social ties and a change in the structure of personal networks for urbanization (Xu, Li, & Jiao, 2016). Most of them would only live with their spouse, hence this nuclear family system could have contributed to the higher prevalence of couple-focused network.

Associations between health outcomes, health-related behaviors and social network types

Based on those differences of social network types on compositions, prevalence and socio-demographics, it’s not hard to understand the differential health outcomes that result from the derived different network types. By involving multiple health measures in the present research, this study supports a more general hypothesis that social network types could have broader impacts on a variety of health indicators, which includes dimensions of physical health, subjective well-being, and health-related behaviors. Moreover, health-related behaviors have a powerful direct effect on physical health and subjective well-being and also play a crucial role in mediating the relationship between social network types and physical health as well as subjective well-being.

First, in comparison to those with non-integrated network types, people with diverse social networks showed lowest score of ADL and IADL, and highest score of MMSE, personality, self-rated QoL, self-rated health and health-related behaviors. However, older people embedded in private network types were at greater risk of various health issues, which proved once again that older adults with an improved state of health are benefited from having several sources of support (Escobar Bravo, Puga, & Martin, 2008; Sirven & Debrand, 2008). And reciprocally, people in good states of health tend to have more-beneficial and resource-rich network types, while older people in poor health are in danger of falling into a vicious cycle (Li & Zhang, 2015).

Second, our findings revealed that older people with resource-rich network types tend to gain more health-promoting behaviors. The supportive evidence is that social network type can be linked closely to health-related behaviors by health-related social control (Umberson, Crosnoe, & Reczek, 2010). Namely, those older adults embedded in resourceful social networks with multiple social ties receive the control of various social agents (such as marital partners, adult child, friends and other family members), which may consequently create positive pressure for the adoption, facilitation, and maintenance of healthier habits or might buffers individuals against the health-damaging behaviors by encourage avoidance and reduction of risky habits.

Third, this research indicates that health-related behaviors are positively associated to multiple health outcomes. That is, older adults who engaged in health-promoting practices tend to achieve independent activities and instrumental activities in daily living, high cognitive ability, positive personality, and high satisfaction with life. This finding echoes the previous study that proved health-promoting behavior engagements had a strong association with general health (Cardazone, 2014).

Finally, the study proves that health-related behaviors play a role in partly mediating the relationship between social network types and health outcomes. One explanation of this particular finding is that the conceptual lens of Berkman et al.’s model through which social support networks affected on health status through health behavioral pathways (Berkman et al., 2000). Since similar studies have proved that social support have indirectly impact on health through behavioral responses (Schwarzer & Leppin, 1991; Uchino, 2009), this study revealed the mediation of health-related behaviors between social network types and health for the first time.

Limitations and future research

A few limitations of the current analysis should be cited. The analysis was based upon available measures in the database which is common in any secondary data analysis. While this constraint did not obstacle the current study since CLHLS data provided plenty of samples and enough relevant indicators. A second limitation is that this study was restricted to cross-sectional data, therefore it is not possible to establish causality between the social network types, health outcomes and health related behaviors. It remains to be proved that the dynamics of support networks under health status’ change, as well as multiple health outcomes and health-related behaviors may reciprocally have the potential to affect the formation of network types. Therefore, the second wave of CLHLS data will be involved to the explication of a causal model in the future research.

Implications to practice

Based on the instructive findings of the current study, it is possible to give some practical implications for further practices. First, the awareness of social network type which the individual is embedded in will increase the potential of gerontological practitioners to establish individualized social and health care plans by critically considering the varied interpersonal social environments. Second, the construct of social network types may be developed to an older adults’ vulnerability assessment tool for clinical practitioners using, by which effective social and health care strategies and campaigns are implemented aimed at promoting vulnerable older adults’ social empowerment. Third, since the mediation of health-promoting behaviors to the pathway of social network typology to health outcomes has been proved, efforts should be made to the direct behavior intervention on health-promotion programs as well as facilitate the opportunities for elders to the social participation.

Conclusion

Given the configurational and actor-centered classification considering a wide range of older adults’ social attributes, this study used a latent class analysis and a path analysis to draw a holistic picture of Chinese elderly’s social world. Despite some heterogeneity of existing social network types, it still confirmed the robust construct of network type for gerontological research and practice in aging. Enriched by a variety of health indicators, the results provide a broader view on multi-dimensional health measures, which implied that individuals’ social network type have a similar influence on all the health indicators. Furthermore, this study highlights the influences of particular role of health-related behaviors.

Funding

Data of this study is from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey which was supported by the [funding Agency 1]; the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant [number 71110107025, 71233001], National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health under Grant [number R01AG023627].

This work was also supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant [number 71573097].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, & Seeman TE (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burholt V, & Dobbs C (2014). A support network typology for application in older populations with a preponderance of multigenerational households. Ageing Society, 34(7), 1142–1169. doi: 10.1017/s0144686x12001511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardazone G (2014). Social Support: Health Promotion and the Prevention of Illness. [Google Scholar]

- Celeux G, & Soromenho G (1996). An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification, 13(2), 195–212. doi: 10.1007/bf01246098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, & Silverstein M (2000). Intergenerational social support and the psychological well-being of older parents in China. Research Aging, 22(1), 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ST, Lee CK, Chan AC, Leung EM, & Lee JJ (2009). Social network types and subjective well-being in Chinese older adults. Journal of Gerontology B Psychological Science Social Science, 64(6), 713–722. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon EY (2010). Correlation of social network types on health status of Korean elders. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 40(1), 88–98. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2010.40.1.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubova Dubova SV, Perez-Cuevas R, Espinosa-Alarcon P, & Flores-Hernandez S (2010). Social network types and functional dependency in older adults in Mexico. BMC Public Health, 10, 104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar Bravo MA, Puga D, & Martin M (2008). Protective effects of social networks on disability among older adults in Madrid and Barcelona, Spain, in 2005 [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Salud Publica, 82(6), 637–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Antonucci TC, & Akiyama H (2008). Profiles of social relations among older adults: a cross-cultural approach. Ageing & Society, 28, 203–231. doi: 10.1017/s0144686x07006472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Smith J, & Antonucci TC (2007). Social network types among older adults: a multidimensional approach. Journal of Gerontology B Psychological Science Social Science, 62(6), P322–P330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flori KL, Antonucci TC, & Cortina KS (2006). Social network typologies and mental health among older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences Social Sciences, 61(1), P25–P32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammervold R, & Olsson UH (2012). Testing structural equation models: the impact of error variances in the data generating process. Quality & Quantity, 46(5), 1547–1570. doi: 10.1007/s11135-011-9466-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan Santini Z, Koyanagi A, Tyrovolas S, Haro JM, Fiori KL, Uwakwa R, … Prina AM (2015). Social network typologies and mortality risk among older people in China, India, and Latin America: A 10/66 dementia research group population-based cohort study. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff CE, Costa JPT, & Lane RD (2008). Age differences in descriptions of emotional experiences in oneself and others. Journals of Gerontology Series B, 63(2), P92–P99. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.2.P92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, & Zhang Y (2015). Social network types and the health of older adults: exploring reciprocal associations. Social Science Medicine, 130, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H (2001). Social network type and morale in old age. Gerontologist, 41(4), 516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H (2003). The association of disability, sociodemographic background, and social network type in later life. Journal of Aging Health, 15(2), 391–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H (2006). Social networks and self-rated health: a cross-cultural examination among older Israelis. Journal of Aging Health, 18, 335–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H, & Shiovitz-Ezra S (2011). Social network type and subjective well-being in a national sample of older Americans. Gerontologist, 51(3), 379–388. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Multivariate Application Series. 1–477. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2012). Mplus User’s Guide. In Muthen CM (Ed.), (Seventh Edition ed.). Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- The People’s Republic of China National Bureau of Statistics (2010) Sixth Census Data bulletin People’s Republic of China.

- Park S, Smith J, & Dunkle RE (2014). Social network types and well-being among South Korean older adults. Aging Ment Health, 18(1), 72–80. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.801064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins JM, Subramanian SV, & Christakis NA (2015). Social networks and health: a systematic review of sociocentric network studies in low- and middle-income countries. Social Science & Medicine, 125, 60–78. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DR, Siu OL, Yeh AG, & Cheng KH (2008). Informal social support and older persons’ psychological well-being in Hong Kong. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 23(1), 39–55. doi: 10.1007/s10823-007-9056-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, & Leppin A (1991). Social support and health: a theoretical and empirical overview. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships, 8(1), 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sirven N, & Debrand T (2008). Social participation and healthy ageing: an international comparison using SHARE data. Social Science Medicine, 67(12), 2017–2026. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Gerstorf D, & Li Q (2008). Psychological resources for well-being among octogenarians, nonagenarians, and centenarians: differential effects of age and selective mortality. In Yi Z, Poston DL, Vlosky DA & Gu D (Eds.), Healthy Longevity in China: Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Psychological Dimensions (pp. 329–346). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Thanakwang K, & Soonthorndhada K (2011). Mechanisms by which social support networks influence healthy aging among Thai community-dwelling elderly. Journal of Aging Health, 23(8), 1352–1378. doi: 10.1177/0898264311418503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health: a life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 4(3), 236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Crosnoe R, & Reczek C (2010). Social relationships and health behavior across life course. Annual Review Social, 36, 139–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger GC, & Tucker I (2002). Using network variation in practice: identification of support network type. Health Social Care Community, 10(1), 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Li J, & Jiao S (2016). Impacts of Chinese urbanization on farmers’ social networks: evidence from the urbanization led by farmland requisition in Shanghai. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 142(2), 05015008. doi: doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yun EH, Kang YH, Lim MK, Oh J-K, & Son JM (2010). The role of social support and social networks in smoking behavior among middle and older aged people in rural areas of South Korea: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 10(78). doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Feng QS, Hesketh T, Christensen K, & Vaupel JW (2017). Survival, disabilities in activities of daily living, and physical and cognitive functioning among the oldest-old in China: a cohort study. Lancet, 389(10079), 1619–1629. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30548-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z (2006). Gender differentials in cognitive impairment and decline of the oldest old in China. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 61(2), S107–S115. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.S107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]