Abstract

Background and Aims

Equine hepacivirus (EqHV) is phylogenetically the closest relative of HCV and shares genome organization, hepatotropism, transient or persistent infection outcome, and the ability to cause hepatitis. Thus, EqHV studies are important to understand equine liver disease and further as an outbred surrogate animal model for HCV pathogenesis and protective immune responses. Here, we aimed to characterize the course of EqHV infection and associated protective immune responses.

Approach and Results

Seven horses were experimentally inoculated with EqHV, monitored for 6 months, and rechallenged with the same and, subsequently, a heterologous EqHV. Clearance was the primary outcome (6 of 7) and was associated with subclinical hepatitis characterized by lymphocytic infiltrate and individual hepatocyte necrosis. Seroconversion was delayed and antibody titers waned slowly. Clearance of primary infection conferred nonsterilizing immunity, resulting in shortened duration of viremia after rechallenge. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell responses in horses were minimal, although EqHV‐specific T cells were identified. Additionally, an interferon‐stimulated gene signature was detected in the liver during EqHV infection, similar to acute HCV in humans. EqHV, as HCV, is stimulated by direct binding of the liver‐specific microRNA (miR), miR‐122. Interestingly, we found that EqHV infection sequesters enough miR‐122 to functionally affect gene regulation in the liver. This RNA‐based mechanism thus could have consequences for pathology.

Conclusions

EqHV infection in horses typically has an acute resolving course, and the protective immune response lasts for at least a year and broadly attenuates subsequent infections. This could have important implications to achieve the primary goal of an HCV vaccine; to prevent chronicity while accepting acute resolving infection after virus exposure.

Abbreviations

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CXCR4

C‐X‐C motif chemokine receptor 4

- DE

differentially expressed

- EPgV

equine pegivirus

- EqHV

equine hepacivirus

- EqPV‐H

equine parvovirus‐hepatitis

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GE

genome equivalents

- GPNMB

glycoprotein NMB

- GLDH

glutamate dehydrogenase

- GO

Gene Ontology

- HVR1

hypervariable region 1

- IFN

interferon

- IL2RG

interleukin‐2 receptor subunit gamma

- ISGs

IFN‐stimulated genes

- miR

microRNA

- MPEG1

macrophage expressed 1

- NS

nonstructural protein

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- RHV

rodent hepacivirus

- RNA‐seq

RNA‐sequencing

- scRNA‐seq

single‐cell RNA‐sequencing

- UTR

untranslated region

HCV is an important human pathogen of the Flaviviridae family, chronically infecting ~70 million persons, who are at increased risk of severe liver disease.( 1 ) Therapeutics have been developed, whereas a vaccine and thorough understanding of pathology and immune responses are lagging. This is largely attributable to the lack of robust immunocompetent animal models, given that chimpanzees are no longer available for research.( 2 ) The enigmatic GB‐virus B (GBV‐B), although related to HCV, never became widely used as a model.( 2 ) Many other related hepaciviruses were subsequently discovered, including those in bats, rodents, monkeys, horses, and cows (reviewed in an earlier work( 3 )), and these can serve as potential surrogate models.( 4 ) Despite the large diversity of these viruses, equine hepacivirus (EqHV; initially named nonprimate hepacivirus, NPHV) remains the closest genetic relative of HCV and therefore is of particular interest.

EqHV closely resembles HCV, including genome organization,( 5 ) hepatotropism,( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ) dual infection outcomes (spontaneous clearance and persistence for >6 months),( 7 , 10 ) and, seemingly, the ability to cause fibrotic disease with chronic infection.( 11 ) HCV‐RNA accumulation is stimulated by binding of the liver‐specific microRNA (miR), miR‐122, to the viral 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR),( 12 ) and miR‐122 similarly binds the EqHV 5′UTR.( 13 , 14 ) Infection kinetics are also similar between EqHV in horses and HCV in humans, including rapid onset of viremia and delayed seroconversion.( 7 , 9 ) EqHV infection in adult horses led to 43%‐100% clearance within 6 months (n = 3‐12),( 7 , 8 , 9 ) which is higher than the 15%‐45% observed for HCV.( 15 ) It appears that foals are more prone to chronicity, given that 6 of 6 experimental infections persisted.( 7 , 10 ) Only one study characterized the immune response to EqHV infection( 9 ) and found possible evidence of EqHV‐specific CD8 T‐cell responses in 1 in 3 horses. Viral clearance resulted in nonsterilizing immunity to rechallenge inoculations in 2 horses. For HCV, transcriptomic analyses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and liver samples of infected humans and chimpanzees demonstrated strong interferon (IFN) responses associated with viral clearance, whereas T‐cell exhaustion often is associated with chronicity.( 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ) Understanding equine immune responses to EqHV could provide insights critical to understand hepaciviral pathogenesis and offer immune correlates relevant for HCV vaccine development. Here, we aimed to characterize the course of experimental EqHV infection, with an emphasis on the nature of antiviral immunity and pathology associated with clearance and protection from reinfection, and characterize gene expression changes in the liver and periphery.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Cornell University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and horses received humane care according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Horses were median 4 years old (range, 2‐8), 5 geldings and 3 mares. Breeds included Morgan Horse (2), Warmblood (2), Arabian (1), Thoroughbred (1), Thoroughbred‐Quarter Horse cross (1), and Quarter Horse (1). Horses were confirmed EqHV and equine parvovirus‐hepatitis (EqPV‐H) serum RNA/DNA and antibody (nonstructural protein [NS] 3 or NS1) negative, as described,( 20 ) and healthy by physical examination, complete blood counts, and serum biochemistry, including markers of liver function. Horses were again confirmed EqPV‐H negative at the completion of the study.

Inoculations and Sample Collection

Horses were inoculated i.v. with 5 mL of 107 genome equivalents (GE)/mL of acute‐phase NZP1 strain serum.( 6 ) Physical examination was performed at each blood draw. Horses were rechallenged i.v. with the same NZP1 inoculum at 6 months, then with 1 mL of 5 × 107 GE/mL of the divergent CU strain serum 1 month later. Two horses were followed for an additional year and rechallenged again with the CU strain.

Serum was collected at week −1, days 0, 1, and 3, and weekly thereafter for 34 weeks. PBMCs were collected at weeks −1, 0, and 1 and then every other week for 26 weeks and prepared by Ficoll density gradient, as described,( 20 ) for flow cytometry. At each collection, additional aliquots of 3.5 × 106 cells were lysed in TRIzol and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction for RNA sequencing (RNA‐seq). Monthly, additional aliquots were cryopreserved in 90% fetal bovine serum and 10% DMSO for enzyme‐linked immunospot (ELISPOT) analysis. For 1 horse (horse N), fresh PBMC aliquots collected at weeks 0 and 2 were submitted for single‐cell (sc)RNA‐seq.

Ultrasound‐guided transcutaneous liver biopsy was performed with 14‐gauge 11.4 cm Tru‐Cut biopsy needles (Medline Industries, Northfield, IL) under sedation with i.v. xylazine and local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine. Biopsies were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histopathology or stored in RNAlater at −80°C for RNA‐seq.

One naïve horse (horse O) was administered CU inoculum to demonstrate infectivity of this inoculum. Serum was collected weekly until viral clearance.

Sample Analysis

Weekly serum biochemistry, EqHV RT‐qPCR, and serology by a luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) was performed. Serum miR‐122 quantification was performed preinfection and at peak hepatitis. Flow cytometric phenotyping of PBMCs was performed biweekly. RNA‐seq on PBMCs and liver biopsies and histopathology on liver biopsies were performed preinoculation (PRE), during early acute infection (ACUTE), near seroconversion (SC), during falling viremia or hepatitis (FV, HEP), and at week 26 (POST; Fig. 1A and Supporting Fig. S1). Hepatitis, or liver injury, was determined by elevation above the reference interval of any of the following circulating liver markers: sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH); glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH); aspartate aminotransferase (AST); gamma‐glutamyl transferase (GGT); bile acids; or direct bilirubin. Libraries for RNA‐seq and scRNA‐seq were prepared as described in Supporting Text S2.

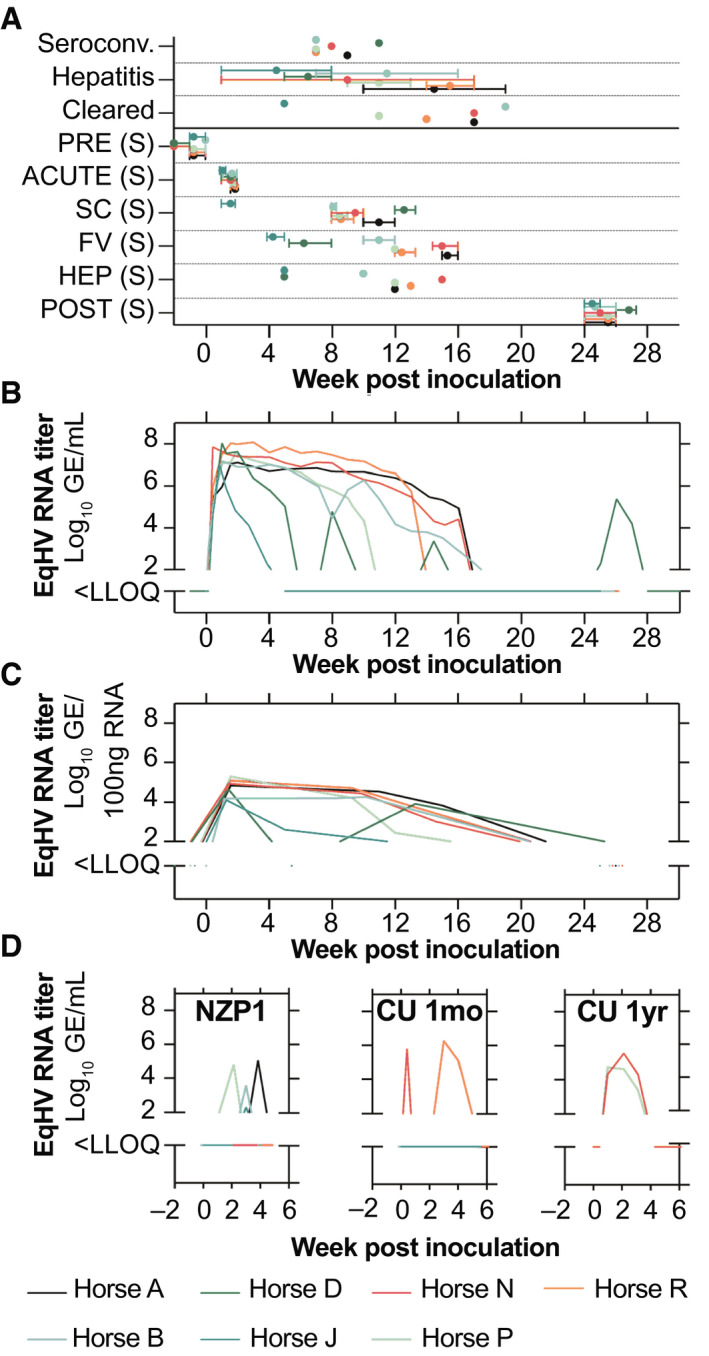

FIG. 1.

EqHV infection typically resolves in horses. (A) Time points of clinical events and sampling (S). Intervals represent time spread for all sample types acquired. Horse D was chronically infected, and its POST sample represents another time point of FV. Horse J SC was the same time as FV and was excluded. (B,C) Serum viremia (B) and liver viral load (C) are shown for the course of primary EqHV NZP1 infection in horses. (D) Viremia during reinfection with homologous NZP1 inoculum, or the heterologous CU strain 1 month (n = 6, excludes horse D), or 1 year after homologous rechallenge (n = 2, horses N and P). Abbreviations: FV, falling viremia; HEP, hepatitis; LLOQ, lower level of quantification; PRE, preinoculation; SC, seroconversion.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are provided as median and range. Mixed‐effects analysis with horse as a random effect and Dunnett’s post hoc tests were performed on clinical parameters. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Differential expression for RNA‐seq data was analyzed in R Studio using Limma and Voom packages as described.( 21 ) Detailed methods and analyses are provided in Supporting Text S2.

Results

To characterize the course of infection and immune responses to EqHV, 7 adult horses were inoculated with strain NZP1 virus, originating from a molecular clone.( 6 ) Primary time points for the samples analyzed are shown in Fig. 1A and Supporting Fig. S1.

EqHV Has a Low Chronicity Rate in Horses

After primary inoculation, all horses became viremic within 1‐3 days. Peak viremia developed by a median of 1 week with titers of 107‐108 GE/mL of serum. Viremia became undetectable by 15.5 (5‐19) weeks in 6 of 7 horses (86%; Fig. 1B), and liver viral load reflected viremia (Fig. 1C). Horse J had a markedly shorter duration of viremia, more similar to rechallenge infections (described below). Horse D had multiple reoccurring phases of detectable viremia (Fig. 1B), which could not be explained by natural reinfection (e.g., from cohousing). Sequence analysis further suggested either recrudescence or persistent infection for horse D (Supporting Fig. S3). Thus, primary infection predominantly led to an acute resolving outcome.

At the time of enrollment, horses R and J were naturally and experimentally( 20 ) infected with equine pegivirus (EPgV)‐1 and ‐2 (previously Theiler’s disease–associated virus, TDAV), respectively. EPgVs, like human pegivirus (HPgV/GBV‐C), are highly prevalent, clinically silent, and can persistently infect the bone marrow.( 20 ) Here, we observed a transient reduction in EPgV titers upon EqHV infection. Interestingly, horses J and R cleared their persistent EPgV infection concomitantly and within 6 weeks of EqHV clearance, respectively (Supporting Fig. S4). Hence, unrelated general immune activation might play a role in the typical sudden clearance of persistent pegivirus infection. Alternatively, given shared peptide sequences, a role for epitopes conserved between EqHV and EPgV cannot be excluded (Supporting Table S5).( 22 )

Prior EqHV Infection Provides Partial Immune Protection

Twenty‐six weeks after primary inoculation, all horses except horse D were rechallenged i.v. with the same NZP1 strain. Three horses (A, B, and P) experienced short‐lived viremia for <2 weeks and titers 2‐3 logs lower compared to primary infection. Horse J had borderline detectable viremia (Fig. 1D). Four to 6 weeks after homologous rechallenge, the 6 horses were rechallenged with highly divergent heterologous serum from a persistently infected horse (CU strain). Two horses (N and R) experienced reinfection with duration of <3 weeks and ~1 log lower viremia compared to primary infections (Fig. 1D). No horses became viremic from both rechallenge inoculations. One year later, horses N and P were rechallenged with the CU inoculum. Both horses became viremic with slightly longer viremia lasting ~3 weeks (Fig. 1D). In summary, clearance of primary infection resulted in broad nonsterilizing immunity that reduced viremia levels and duration, and this partial immune protection lasted at least a year.

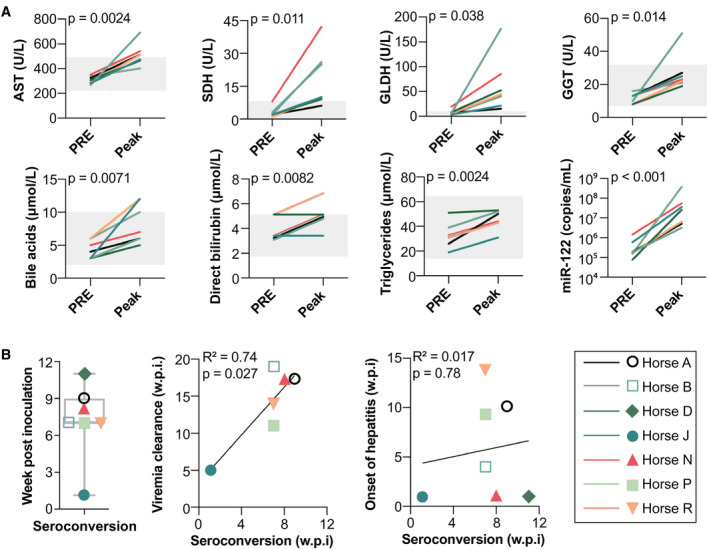

EqHV Infection Causes Subclinical Hepatitis

Hepatitis, as determined by elevated circulating liver markers, began a median of 4 (1‐14) weeks after primary inoculation and lasted for a median of 8 (4‐16) weeks. Hepatitis was mild and subclinical (Fig. 2A and Supporting Fig. S6A), consistent with mild liver injury. Given that enhanced miR‐122 serum levels can be observed during other types of acute and chronic liver injury,( 23 ) we measured serum miR‐122 levels and found a significant increase for all 7 horses during peak hepatitis (P < 0.001; Fig. 2A), as well as a significant association with serum AST (P = 0.0499; Supporting Fig. S6B). Measurement of miR‐122 levels over time for 2 horses showed that miR‐122 was 250%‐1,250% of baseline whereas other markers remained near baseline (Supporting Fig. S6C). Thus, miR‐122 serves as a marker of acute hepacivirus‐induced liver damage in horses as well and appears more sensitive compared to other markers.

FIG. 2.

EqHV infection results in subclinical hepatitis and delayed seroconversion. (A) Preinoculation and peak serum liver markers during primary EqHV infection. Reference intervals indicated by gray shading. To account for repeated measures, mixed‐effects models with horse as a random effect were used to evaluate the association of each marker concentration with infection time point. (B) Time of seroconversion is shown and compared to time of viral clearance (n = 6) or onset of hepatitis (n = 7). Pearson’s correlation with linear regression is shown. Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma‐glutamyl transferase; GLDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; PRE, preinoculation; SDH, sorbitol dehydrogenase; w.p.i., week postinoculation.

Subclinical hepatitis was not a significant feature during rechallenge inoculations. No horses developed hepatitis during NZP1 rechallenge, and 1 developed mild hepatitis during CU rechallenge (horse R; peak GLDH 438% of reference interval, all other liver markers within reference intervals).

Anti‐NS3 Seroconversion Precedes Viral Clearance

To understand humoral immune responses, we analyzed antibodies to the viral nonstructural protein, NS3, which is among the most conserved regions of the polyprotein. Although anti envelope protein responses would be of interest as a potential marker of neutralization potential, their measurement has proven less robust, either for technical reasons or because of lower immunogenicity.( 24 ) Horses seroconverted to NS3 at 7 (1‐11) weeks after inoculation (Fig. 2B and Supporting Fig. S6A). Horse J showed markedly shorter time to seroconversion, suggestive of an anamnestic response. Timing of seroconversion did not correlate to the onset of hepatitis (Pearson’s r 2 = 0.017; P = 0.78), whereas it always preceded viral clearance by 7.5 (4‐12) weeks (Pearson’s r 2 = 0.74; P = 0.027; Fig. 2B). Antibody titers slowly waned over time, but increased after productive rechallenge inoculations (Supporting Fig. S7).

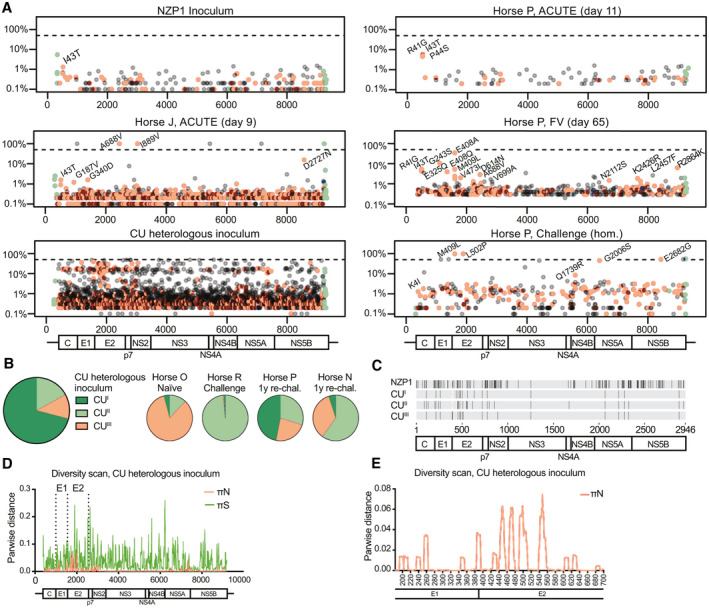

Little Evidence for Selection of Immune Escape Variants

HCV continuously evolves to avoid adaptive immunity.( 25 ) Here, for the NZP1 inoculum and for most acute phase samples, only minimal variation from the consensus sequence was observed (Fig. 3A and Supporting Figs. S3 and S8A). Whereas low‐frequency variants (0.1%‐20%) accumulated over time, nonsynonymous changes to the consensus sequence were observed only for horse J during its short acute infection: A688V in E2 and I889V in NS2 (Fig. 3A). In homologous rechallenge samples analyzed from 2 horses (A and P), two complete changes in E2 (M409L, L502P) and two ~50% changes in NS5A‐B (G2006S, E2682G) were observed for horse P (Fig. 3A), whereas none were observed for horse A (Supporting Fig. S8A). Evidence of immune pressure on residue 409 was observed already at day 65 of the primary infection in horse P (Fig. 3A). The nonsynonymous changes for horses J and P likely represented attempts to escape preexisting immunity.

FIG. 3.

EqHV evolution over the course of infection shows little evidence of immune escape. (A) Viral genome diversity is shown for the NZP1 inoculum, for representative ACUTE, FV, and homologous rechallenge time points from horse P, for the ACUTE time point for horse J, and for the CU heterologous inoculum. Data for remaining horses are shown in Supporting Fig. S8. Nonsynonymous changes are in orange, synonymous in gray, and UTR changes in green. Nonsynonymous changes with a frequency >1% are annotated (except for CU). The dashed line indicates 50% (consensus change). (B) Three CU subpopulations are recognized (GenBank MT955622‐24) and shown in a pie chart, with the distribution in inoculated horses shown to the right. (C) Nonsynonymous differences among NZP1 and CU subpopulations (no reference sequence set). (D,E) Viral diversity scan for the CU inoculum across the genome (D; nt) or E1‐E2 region (E; aa). Abbreviations: aa, amino acid; FV, falling viremia; nt, nucleotide.

The CU inoculum differed by 161 amino acids from the NZP1 strain (94.5% identity), and was highly diverse, consisting of three subpopulations (Fig. 3A‐C and Supporting Fig. S8B). Major nonsynonymous variation was found in E1, E2, NS2, and NS5A (Fig. 3D), with particular variation in the E2 N‐terminus, corresponding to the HCV hypervariable region 1 (HVR1),( 26 ) but also in downstream E2 regions (Fig. 3E and Supporting Fig. S8C). Interestingly, after rechallenge of horse R, subpopulation CUII dominated, whereas subpopulations CUII and CUIII were selected in horse N and all subpopulations were present in horse P after the 1‐year rechallenge. After CU inoculation of a naïve horse (horse O), subpopulation CUIII was selected.

In summary, EqHV sequences were stable over time, and we observed little evidence of selection of escape variants to adaptive immunity, including for the presumed low‐level persistently infected horse D.

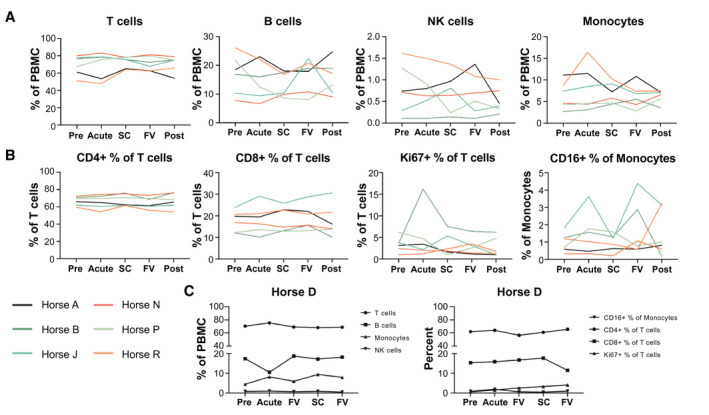

No Major Changes in PBMC Populations During EqHV Infection

To monitor cellular immune responses to EqHV infection, complete blood count and flow cytometric phenotyping of PBMCs were performed. Overall, no significant differences were observed in any PBMC population over the 26 weeks after primary inoculation (Fig. 4 and Supporting Fig. S9). Total T cells (Fig. 4A), and in particular CD4 T cells (Fig. 4B), comprised the largest PBMC subpopulations and showed little variation over time. Although some horses showed prominent expansion of smaller subpopulations at single time points (Fig. 4; B cells in horse J, monocytes in horse R, and Ki‐67+ T cells in horse B), these findings were not consistent across animals and time points. Similar variation was observed in the horses after viral clearance (Supporting Fig. S9), suggesting natural or technical variability.

FIG. 4.

No significant changes to PBMC populations during acute EqHV infection. Flow cytometric quantification of major PBMC subpopulations over the course of infection. (A) Proportion of major cell types as percent of total PBMCs. (B) Proportions of T‐cell and monocyte subtypes. (C) Chronically infected horse D is shown separately because of different time‐point designations. Data are deposited in Flow Repository with accession number FR‐FCM‐Z2V7. Abbreviations: FV, falling viremia; NK, natural killer; PRE, preinoculation; SC, seroconversion.

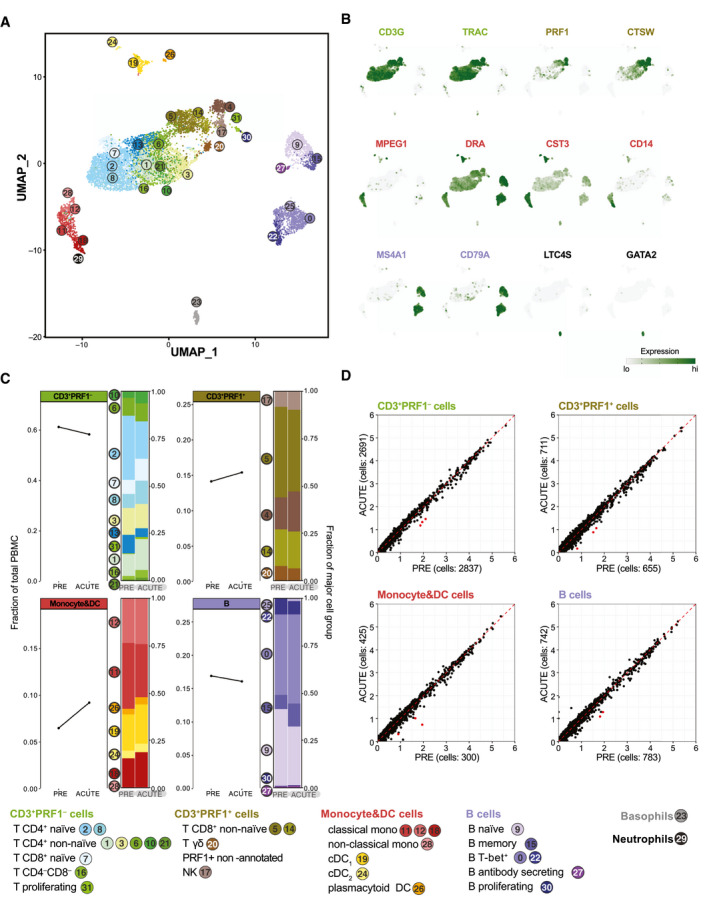

To reveal potential changes to cellular gene expression not affecting cell frequency, we performed poly(A)‐specific RNA‐seq on PBMCs at PRE, ACUTE, SC, FV, and POST time points. No significant differentially expressed (DE) genes were detected at any time point among the 6 resolving horses. To address changes to minor cell‐type populations, we further performed scRNA‐seq on horse N at the PRE and ACUTE time points. The ACUTE time point was chosen as near peak viremia, when a strong IFN response might be expected. This analysis resolved equine PBMC subpopulations in great depth( 21 ) (Fig. 5A,B). Nonetheless, no infection‐mediated differences in cell‐population proportions (Fig. 5C) and only minimal differences in gene expression (Fig. 5D) were observed, corroborating the bulk RNA‐seq analysis.

FIG. 5.

scRNA‐seq of PBMCs reveals minimal changes in cell frequency and gene expression upon EqHV infection. Gene expression in 9,245 equine PBMCs from horse N across PRE and ACUTE time points. (A) UMAP plot with cells represented as dots and colored by cell‐type cluster. Classification by projection on reference equine PBMC data set.( 21 ) (B) Gene expression plots depicting select cell group marker genes overlaid on the UMAP plot of (A). Expression values are scaled independently, ranging from 2.5th to 97.5th percentile. (C) Cell‐frequency plots of major cell groups across PRE and ACUTE time points. Stacked bar plots illustrate frequency of subpopulations. (D) Average expression (natural log transformed) per gene for PRE and ACUTE time points within major cell groups. Points highlighted in red were DE (FDR < 5 × 10−6 and log2‐FC > 0.58). Data are deposited in GEO with accession number GSE167260. Abbreviations: CST3, cystatin C; CTSW, cathepsin W; DC, dendritic cell; DRA, DR alpha chain; GATA2, GATA binding protein 2; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; LTC4S, leukotriene C4 synthase; MS4A1, membrane spanning 4‐domains A1; PRE, preinoculation; PRF1, perforin 1; TRAC, T‐cell receptor alpha constant.

Analysis of EqHV‐Specific T Cells

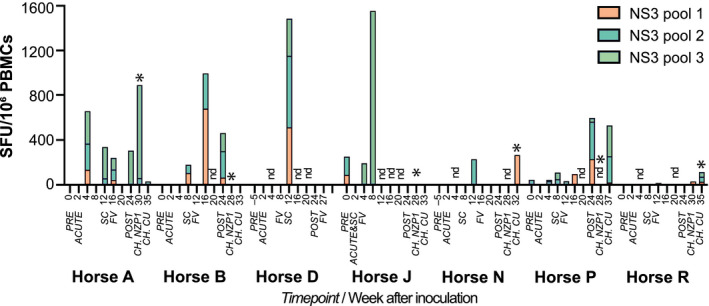

To detect EqHV‐specific T cells, we stimulated PBMCs with three peptide pools spanning the complete NZP1 NS3 protein. A significant, but variable, increase in the frequency of EqHV‐specific IFN‐γ‐producing T cells after infection or reinfection was observed in all 7 horses (Fig. 6). In 4 horses (B, D, N, and P), the first robust production of EqHV‐specific T cells was detected around the time of seroconversion. In horse A, T cells appeared early during infection (4 weeks) and persisted through the study. Horse R only had minimal responses during the entire course of primary infection. Horse J in particular had evidence of preexisting anti‐EqHV‐specific T cells. Combined with its rapid clearance of infection (Fig. 1B), early seroconversion (Fig. 2B and Supporting Figs. S6A and S7), and rapid viral sequence changes (Fig. 3A), this would be consistent with previous EqHV exposure. An increased number of EqHV‐specific T cells was observed after clearance (FV) for horses B, J, and P or after productive rechallenge in accordance with a recall T‐cell response for horses A, N, and R. Interestingly, no T‐cell expansion was observed after productive rechallenge of horses B, J, or P.

FIG. 6.

Detection of virus‐specific IFN‐γ‐producing T cells in EqHV‐infected horses. ELISPOT quantification of IFN‐γ‐producing PBMCs stimulated by each of three peptide pools spanning the NS3 protein. Expressed as mean spot forming units (SFU) above baseline (mean media control) for each sample. Samples with mean SFU below background (mean media control + 3× SD) are set to zero for display. *Productive rechallenge infection. NZP1 rechallenge data for horses N and P were not done. Abbreviations: CH, rechallenge inoculations; FV, falling viremia; nd, not done; SC, seroconversion.

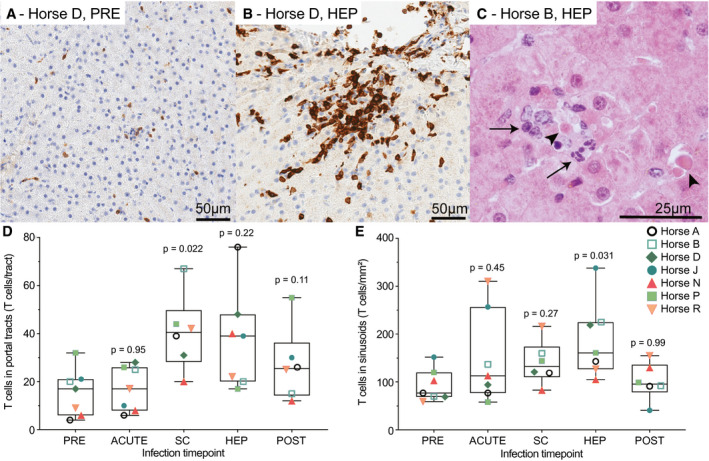

Liver Histopathology Is Characterized by Necrotic Hepatocytes and T‐Cell Infiltrates

HCV causes lymphocytic necroinflammation during acute infection in humans.( 27 ) Here, PRE liver histology was normal, except in horses B (fibrosis) and N (cholangitis; Supporting Fig. S10). These histological findings were distinctly different from findings during EqHV infection in the other horses. During viremia (ACUTE, SC) and HEP, lesions suggestive of viral infection were evident in all 7 horses, including increased numbers of sinusoidal T cells (Fig. 7A,B), portal lymphocytic infiltrates with some breaching of the limiting plate, and small nodules of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and dendritic cells in the parenchyma. Samples from 4 horses had individual necrotic hepatocytes with lymphocytic satellitosis and fewer neutrophils (Fig. 7C). Horse D had active hepatitis at the POST time point, associated with recrudescence of EqHV. There was significant lymphocyte infiltration across all time points in portal tracts (P = 0.045; Fig. 7D), but not sinusoids (P = 0.095; Fig. 7E). Fibrosis was not a significant feature (Supporting Fig. S10).

FIG. 7.

Liver histopathology is characterized by necrotic hepatocytes and T‐cell infiltrates. (A,B) Anti‐CD3 IHC (brown) showing T cells for horse D preinfection (A) and during hepatitis (B). (C) HE staining of horse B during hepatitis showing individual necrotic hepatocytes (arrowheads), surrounded by lymphocytes and fewer neutrophils (arrows). (D,E) T‐cell infiltrates were compared across time points using a mixed‐effects model with horse as random effect (portal tracts, P = 0.045; sinusoids, P = 0.095). No horse effect was detected; therefore, a post hoc Dunnett’s test was applied comparing T‐cell numbers at each time to preinfection as shown. Horse D week 27 POST sample was excluded because of recrudescence of chronic EqHV infection and active hepatitis. Abbreviations: HEP, hepatitis; PRE, preinoculation; SC, seroconversion.

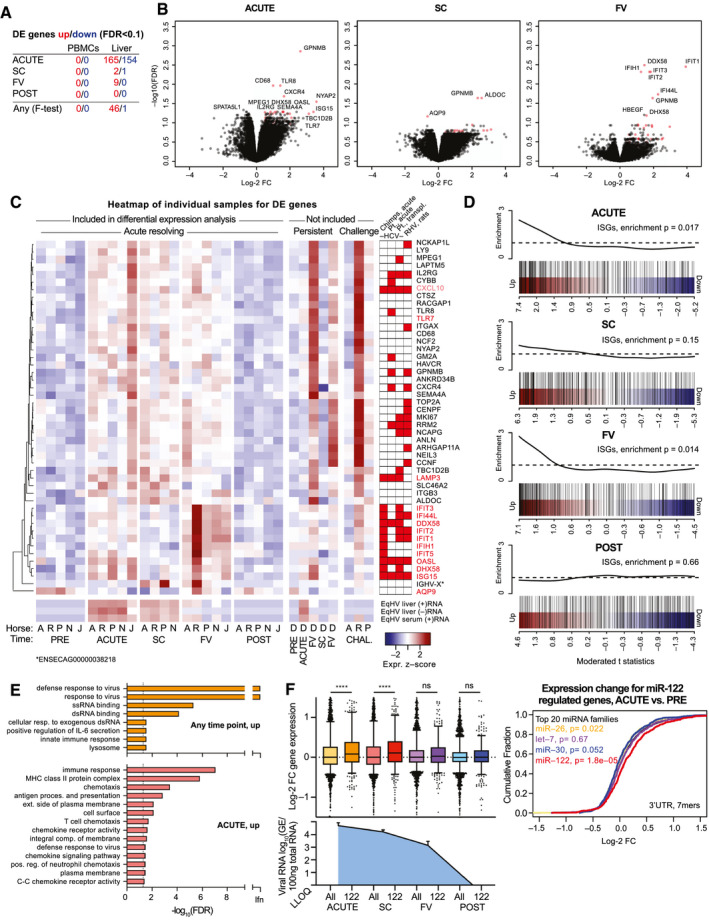

Liver Transcriptional Responses Reveal Signatures of Innate Immune Responses

To assess intrahepatic transcriptome responses, total RNA‐seq was performed on PRE, ACUTE, SC, FV, and POST infection liver biopsies from resolving horses. In a multiple comparison F‐test for 5 resolving horses (horse B excluded for technical reasons), 46 host genes were significantly (false discovery rate [FDR], <0.1) up‐regulated and one down‐regulated at any time point compared to PRE (Fig. 8A). The strongest response was at the ACUTE and FV time points (Fig. 8B). Among the 47 DE genes (Fig. 8C and Supporting Fig. S11A), 14 were IFN‐stimulated genes (ISGs)( 28 ) and others were consistent with an increase in leukocytes (interleukin‐2 receptor subunit gamma [IL2RG], C‐X‐C motif chemokine receptor 4 [CXCR4], CD68, glycoprotein NMB [GPNMB], and macrophage expressed 1 [MPEG1]). The week 5 (FV) and week 27 (POST/second FV) samples from horse D both represented time points of falling viremia and resembled the FV time point for other horses (Fig. 8C). Viral RNA was significant in our analysis and followed intrahepatic RT‐qPCR data, with a 100‐fold excess of (+) to (−) strand reads (Fig. 8C and Supporting Fig. S11A‐C). Among rechallenge samples, horse R, taken during peak viremia and hepatitis and within a week of clearance, showed strong responses; horse P, taken within a week of clearance, showed intermediate responses; whereas horse A, taken 2 weeks after the last positive serum sample, showed no responses (Fig. 8C). An overlap of genes, in particular among ISGs, was found with acute‐phase liver samples of HCV‐infected chimpanzees( 17 ) or humans,( 18 ) liver transplant organs becoming HCV infected posttransplantation,( 19 ) and rodent hepacivirus (RHV)‐infected rats( 29 ) (Fig. 8C). Genes up‐regulated at the ACUTE and FV time points were significantly enriched for ISGs (Fig. 8D). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis across the 46 genes up‐regulated at any time point showed enrichment for response to virus, exogenous RNA, and innate immunity (Fig. 8E). For the ACUTE time point, terms associated with immune response, antigen presentation and chemokine activity, were enriched, suggesting antigen presentation in the liver taking place already at this time. Down‐regulated genes at the ACUTE time point were enriched for GO terms associated with normal cell and liver function (Supporting Fig. S11D). In summary, acute resolving EqHV infection was consistent with signatures of innate immunity and antigen presentation in the liver.

FIG. 8.

Liver transcriptional analysis reveals an ISG response. (A) The number of DE genes compared to PRE is indicated for individual time points and for multiple comparison (any). (B) Volcano plots of indicated time points compared to PRE in liver. The most significant genes are labeled. DE genes at any time point (F‐test) are indicated in red. (C) Heatmap showing scaled expression of liver DE genes at any time point across individual samples. EqHV (+/–) strand were significantly regulated. Scaled serum RT‐qPCR‐derived (+)RNA levels are shown for comparison. Genes significantly up‐regulated during HCV or RHV infection are indicated.( 17 , 18 , 19 , 29 ) (D) Gene set enrichment testing barcode plots for ISGs in the liver at time points as indicated. ROAST P values are shown. (E) GO analysis for up‐regulated genes in the liver at time points indicated. (F) Left: box plots of log‐2 FC liver gene expression for mRNAs with 7‐ or 8‐mer seed sites of any top 20 expressed miRNA (All) or miR‐122 specifically (122) in the 3′UTR is shown for time points indicated. Liver viral load is shown for comparison. Right: cumulative density function (CDF) of the log‐2 FC in liver gene expression for the ACUTE time point. mRNAs are grouped by presence of miRNA 7‐ or 8‐mer seed site in the 3′UTR. ****P < 0.0001. Data are deposited in GEO with accession number GSE158753. Abbreviations: ALDOC, aldolase, fructose‐bisphosphate C; ANKRD34B, ankyrin repeat domain 34B; ANLN, anillin actin binding protein; AQP9, aquaporin 9; ARHGAP11A, Rho GTPase activating protein 11A; CCNF, cyclin F; CENPF, centromere protein F; CTSZ, cathepsin Z; CXCL10, C‐X‐C motif chemokine ligand 10; CYBB, cytochrome B‐245 beta chain; DDX58, DExD/H‐box helicase 58; DHX58, DExH‐box helicase 58; dsRNA, double‐stranded RNA; FC, fold change; FV, falling viremia; HBEGF, heparin binding EGF‐like growth factor; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; GM2A, GM2 ganglioside activator; HAVCR, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 1; IFI44L, interferon‐induced protein 44‐like; IFIH1, interferon‐induced helicase C domain‐containing protein 1; IFIT1, interferon‐induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1; IFIT2, interferon‐induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2; IFIT3, interferon‐induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3; IFIT5, interferon‐induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 5; IGHV‐X, immunoglobulin variable region heavy chain; ISG15, ISG15 ubiquitin‐like modifier; ITGAX, integrin subunit alpha X; ITGB3, integrin alpha‐V/beta‐3; LAMP3, lysosomal‐associated membrane protein 3; LAPTM5, lysosomal protein transmembrane 5; LLOQ, lower level of quantification; LY9, lymphocyte antigen 9; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; MKI67, marker of proliferation Ki‐67; NCAPG, non‐SMC condensin I complex subunit G; NCF2, neutrophil cytosolic factor 2; NCKAP1L, NCK‐associated protein 1‐like; NEIL3, Nei‐like DNA glycosylase 3; NYAP2, neuronal tyrosine‐phosphorylated phosphoinositide‐3‐kinase adapter 2; OASL, 2′‐5′‐oligoadenylate synthetase‐like; PRE, preinoculation; RACGAP1, Rac GTPase activating protein 1; RRM2, ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M2; SC, seroconversion; SEMA4A, semaphorin 4A; SLC46A2, solute carrier family 46 member 2; SPATA5L1, spermatogenesis‐associated 5‐like 1; ssRNA, single‐stranded RNA; TBC1D2B, TBC1 domain family member 2B; TLR7, Toll‐like receptor 7; TLR8, Toll‐like receptor 8; TOP2A, DNA topoisomerase II alpha.

EqHV Infection Functionally Sequesters miR‐122 In Vivo

In addition to the direct role of miR‐122 in supporting HCV replication, in vitro studies show that HCV sequesters enough miR‐122 to deplete the available cellular pool and cause functional derepression of mRNAs normally repressed by miR‐122.( 30 ) Here, we intriguingly found that cellular mRNAs normally repressed by miR‐122, that is, harboring a (7‐ or 8‐mer) miR‐122 seed site in their 3′UTR, were significantly up‐regulated at ACUTE and SC time points of EqHV infection, consistent with derepression (Fig. 8F). Up‐regulation was less pronounced at FV, and no difference was observed at the POST time point. miRNA‐specific derepression was not observed for other abundant miRNAs (Fig. 8F and Supporting Fig. S11E‐I). These data represent a functional miRNA sequestration by an RNA virus observed in vivo, and emphasize the functional importance of this intriguing RNA‐based mechanism of gene regulation. This might have particular relevance for HCV‐induced liver cancer, in that miR‐122 is a tumor suppressor.( 31 )

Discussion

EqHV infection of horses could serve as an animal model to understand fundamental aspects of intrahepatic immune responses that can protect against, or lead to clearance of, hepaciviral infection and thus could be of direct relevance for design of HCV vaccine candidates. Here, we observed a clinical course similar to previous reports,( 7 , 8 , 9 ) with a low chronicity rate and subclinical hepatitis as the primary outcome. Importantly, the inoculum and study animals were negative for EqPV‐H, a recently discovered hepatitis virus of horses.( 32 ) Histopathological changes in horses were similar to acute HCV in humans, with lymphocytic infiltrate and some hepatocyte necrosis. A recent report of liver disease associated with chronic EqHV infection also showed similarities to chronic HCV infection in humans.( 11 ) Thus, EqHV also appears to be of clinical importance in equine medicine and warrants further study.

The initial goal of an HCV vaccine is to prevent chronicity while accepting acute resolving infection.( 33 ) Indeed, resolving infection was the primary outcome of EqHV infection in this and previous studies,( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ) providing an opportunity to characterize the immune responses leading to viral clearance and protection from challenge infections, which is difficult to study for other species of hepacivirus, where chronicity is the primary outcome. Clearance was associated with earlier seroconversion and elevated circulating liver markers. This included elevated serum miR‐122, which we established as a marker of hepatitis during acute hepacivirus infection. Given its high sequence conservation, miR‐122 may be particularly attractive for studies in nonmodel organisms. Despite no major changes in PBMC populations, EqHV‐specific T‐cell responses were observed in all horses and expanded during rechallenge and therefore likely contributed to clearance. Therefore, further study of immune responses to EqHV could yield valuable information on protective immunity to hepaciviruses. Importantly, primary infection with NZP1 provided broad protection against homologous and heterologous rechallenges.

Protective immunity waned over time, with longer duration of reinfection when rechallenged after 1 year. This correlated with observations for HCV in chimpanzees and GBV‐B in tamarins.( 34 , 35 ) Declining antibody titers were also previously observed in horses.( 7 ) This might explain how horses J and O could be NS3 seronegative before inoculation, although progressing with a clinical course consistent with previous infection. Given that only NS3 antibodies were assessed, these horses could have developed responses to other viral proteins, as observed for HCV.( 36 ) Such recurrent infections throughout the life of a horse could explain the high seropositivity rates reported (30%‐40%).( 8 , 37 )

Although HCV rapidly evolves to escape immune pressure and establish persistence,( 25 ) we observed little evidence of immune evasion in primarily resolving EqHV infection. Nonsynonymous changes in horses J (primary infection) and P (rechallenge) might represent adaptive immunity‐induced selection, which, however, did not lead to escape. Escape mutations were also not observed for horse D, which was persistently infected for at least 7 months. Our study therefore did not allow evaluation of viral escape in persistently infected horses. We did, however, find that EqHV sequence diversity was particularly high in the N‐terminus of the E2 protein, suggesting the existence of an HVR1 similar to that of HCV.( 26 ) For HCV, HVR1 plays a role in viral immune evasion.( 26 )

Compared to acute HCV infection, equine immune response to EqHV showed similarities in intrahepatic responses, but notable differences in peripheral responses. We observed no major changes in PBMC populations, phenotypes, or gene expression in acute resolving horses, whereas PBMCs from acutely HCV‐infected patients showed a strong innate response with type I IFN and inflammatory gene signatures and a possible reduction in B cells.( 16 ) In contrast, equine liver transcriptomic responses were similar to hepacivirus‐infected human, chimpanzee, and rat liver,( 17 , 18 , 19 , 29 ) with strong innate immune responses. Whereas we observed a transcriptome signature suggestive of dendritic cell or macrophage antigen presentation during early acute infection, the lymphocytic infiltrate observed on immunohistochemistry (IHC) during seroconversion and hepatitis was not strongly reflected in transcriptomic data. The study may be underpowered to clearly detect this, or the abundant RNA in hepatocytes may have overshadowed any leukocyte signal. Overall, the similar liver response between horses and humans for EqHV and HCV infections, respectively, suggests that horses are likely to be a useful outbred surrogate animal model for intrahepatic pathology and immune responses to HCV. An additional benefit of horses over rodent models is that longitudinal liver tissue from a single animal is readily accessible, allowing multi‐time‐point analyses, as exemplified here.

HCV sequestration of miR‐122, at least in vitro, can lead to indirect gene regulation through miRNA “sponging”.( 30 ) This is of particular interest, given that miR‐122 is a tumor suppressor, and that miR‐122 knockout mice spontaneously develop HCV‐like liver disease.( 31 ) Here, we found miR‐122‐specific derepression of cellular mRNAs upon EqHV infection of the liver and strong correlation with viral load in the liver. Although a causative effect cannot be established, this is a demonstration of functional miRNA sequestration by an RNA virus in vivo. These findings emphasize a putative functional importance of this RNA‐based mechanism in the cause of liver pathology as a result of hepaciviral infection.

We noted that coinfecting pegiviruses in two cases were cleared concomitantly with the superinfecting EqHV. This was preceded by a transient reduction in EPgV titers upon EqHV infection, which was similar to observations with simian‐pegivirus–infected macaques superinfected with simian immunodeficiency virus.( 38 ) These findings suggest that general innate immune activation incurred by other infections, such as EqHV, might explain the spontaneous clearance of pegiviruses even years after infection.( 39 ) Indeed, concomitant clearance of HPgV and HCV infection was observed in patients after therapeutically administrated IFN‐α.( 40 ) It cannot be excluded, however, that the peptide sequences of up to nine amino‐acid residues shared between EqHV and EPgVs are targets of adaptive immunity, as demonstrated for HCV and influenza virus.( 22 ) Whereas interference was observed between different strains of HCV, or HCV and HBV competing for the same liver cells,( 41 ) coinfection‐mediated concomitant viral clearance in unrelated tissues should be explored further.

In summary, our findings suggest an equine immune response more competent in clearing infection compared to human immune responses to HCV. Thus, EqHV infection in horses could provide a useful model to understand drivers of hepacivirus clearance and, consequently, for development of HCV vaccines. We uncovered a primarily hepatic response driving viral clearance, and our findings reveal the specifics of, particularly innate, immune responses linked to resolving infection. The change and waning of these responses over time should be a focus for further understanding of hepaciviral immunity. Although RHV models similarly mirror HCV infection and will be highly useful,( 4 ) EqHV could be an important parallel system to understand hepaciviral pathology and immune responses, especially because of its closer genetic relatedness to HCV and suitability for within‐animal longitudinal sampling. Additionally, EqHV is a significant equine pathogen, thereby improving our understanding of equine liver disease.

Author Contributions

J.E.T.: ‐ Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing. R.W.: ‐ Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – reviewing and editing. U.F.: ‐ Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – reviewing and editing. R.S.P.: ‐ Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing. S.T.: ‐ Investigation, Methodology, Writing – reviewing and editing. A.K.: ‐ Investigation. H.S.: ‐ Investigation. L.N.: ‐ Investigation. S.P.M.: ‐ Investigation, Visualization, Writing – reviewing and editing. J.B.: ‐ Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – reviewing and editing. B.C.T.: ‐ Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision. A.K.: ‐ Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – reviewing and editing. B.R.R.: ‐ Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – reviewing and editing. C.M.R.: ‐ Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – reviewing and editing. T.J.D.: ‐ Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – reviewing and editing. G.R.V.W.: ‐ Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – reviewing and editing. T.K.H.S.: ‐ Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – reviewing and editing. Possible roles: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Mason Jager for his assistance with histology figure preparation, Cornell University Biotechnology Resource Center for sequencing, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Hvidovre Hospital for access to sequencing equipment, and members of the authors’ laboratories for support and fruitful discussion.

Supported by grants from the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative competitive grant no. 2016‐67015‐24765 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the Jack Lowe Equine Health Funds/Mollie Wilmot Equine Research Fund, the European Research Council (ERC Starting Grant 802899 to T.K.H.S.), Independent Research Fund Denmark (6110‐00595 and 6111‐00314 to T.K.H.S. and 4004‐00598 to J.B.), the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF15OC0017404 to T.K.H.S. and NNF18OC0055462 to J.B.), the Lundbeck Foundation (R192‐2015‐1154 to T.K.H.S.), the Danish Cancer Society (R204‐A12639 to J.B.), and the Weimann Foundation (to T.K.H.S. and U.F.). J.E.T. was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award no. K08AI141767. R.W. was supported by an Early Postdoc.Mobility Fellowship (P2BEP3_178527) and a Postdoc.Mobility Fellowship (P400PB_183952) from the Swiss National Science Foundation. Additional support for B.R.R. and R.S.P. came from the Department of Microbiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders, including the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Contributor Information

Gerlinde R. Van de Walle, Email: tscheel@sund.ku.dk, Email: grv23@cornell.edu.

Troels K.H. Scheel, Email: tscheel@sund.ku.dk, Email: grv23@cornell.edu.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co‐first authorship.

- 1. Blum HE. History and global burden of viral hepatitis. Dig Dis 2016;34:293‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bukh J. Animal models for the study of hepatitis C virus infection and related liver disease. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1279‐1287.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hartlage AS, Cullen JM, Kapoor A. The strange, expanding world of animal hepaciviruses. Annu Rev Virol 2016;3:53‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hartlage AS, Murthy S, Kumar A, Trivedi S, Dravid P, Sharma H, et al. Vaccination to prevent T cell subversion can protect against persistent hepacivirus infection. Nat Commun 2019;10:1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kapoor A, Simmonds P, Gerold G, Qaisar N, Jain K, Henriquez JA, et al. Characterization of a canine homolog of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:11608‐11613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scheel TKH, Kapoor A, Nishiuchi E, Brock KV, Yu Y, Andrus L, et al. Characterization of nonprimate hepacivirus and construction of a functional molecular clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:2192‐2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramsay JD, Evanoff R, Wilkinson TE, Divers TJ, Knowles DP, Mealey RH. Experimental transmission of equine hepacivirus in horses as a model for hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2015;61:1533‐1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pfaender S, Cavalleri JMV, Walter S, Doerrbecker J, Campana B, Brown RJP, et al. Clinical course of infection and viral tissue tropism of hepatitis C virus‐like nonprimate hepaciviruses in horses. Hepatology 2015;61:447‐459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pfaender S, Walter S, Grabski E, Todt D, Bruening J, Romero‐Brey I, et al. Immune protection against reinfection with nonprimate hepacivirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:E2430‐E2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gather T, Walter S, Pfaender S, Todt D, Feige K, Steinmann E, et al. Acute and chronic infections with nonprimate hepacivirus in young horses. Vet Res 2016;47:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tegtmeyer B, Echelmeyer J, Pfankuche VM, Puff C, Todt D, Fischer N, et al. Chronic equine hepacivirus infection in an adult gelding with severe hepatopathy. Vet Med Sci 2019;372‐378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sarnow P, Sagan SM. Unraveling the mysterious interactions between hepatitis C virus RNA and liver‐specific microRNA‐122. Annu Rev Virol 2016;3:309‐332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yu Y, Scheel TKH, Luna JM, Chung H, Nishiuchi E, Scull MA, et al. miRNA independent hepacivirus variants suggest a strong evolutionary pressure to maintain miR‐122 dependence. PLoS Pathog 2017;13:e1006694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tanaka T, Kasai H, Yamashita A, Okuyama‐Dobashi K, Yasumoto J, Maekawa S, et al. Hallmarks of hepatitis C virus in equine hepacivirus. J Virol 2014;88:13352‐13366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoofnagle JH. Course and outcome of hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002;36(5 Suppl. 1):S21‐S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rosenberg BR, Depla M, Freije CA, Gaucher D, Mazouz S, Boisvert M, et al. Longitudinal transcriptomic characterization of the immune response to acute hepatitis C virus infection in patients with spontaneous viral clearance. PLoS Pathog 2018;14:e1007290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu C, Boon D, McDonald SL, Myers TG, Tomioka K, Nguyen H, et al. Pathogenesis of hepatitis E virus and hepatitis C virus in chimpanzees: similarities and differences. J Virol 2010;84:11264‐11278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dill MT, Makowska Z, Duong FHT, Merkofer F, Filipowicz M, Baumert TF, et al. Interferon‐γ‐stimulated genes, but not USP18, are expressed in livers of patients with acute hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2012;143:777‐786.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peng X, Li YU, Walters KA, Rosenzweig ER, Lederer SL, Aicher LD, et al. Computational identification of hepatitis C virus associated microRNA‐mRNA regulatory modules in human livers. BMC Genom 2009;10:373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomlinson JE, Wolfisberg R, Fahnøe U, Sharma H, Renshaw RW, Nielsen L, et al. Equine pegiviruses cause persistent infection of bone marrow and are not associated with hepatitis. PLoS Pathog 2020;16:e1008677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patel RS, Tomlinson JE, Divers TJ, Van de Walle GR, Rosenberg BR. Single‐cell resolution landscape of equine peripheral blood mononuclear cells reveals diverse cell types including T‐bet+ B cells. BMC Biol 2021;19:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wedemeyer H, Mizukoshi E, Davis AR, Bennink JR, Rehermann B. Cross‐reactivity between hepatitis C virus and influenza a virus determinant‐specific cytotoxic T cells. J Virol 2001;75:11392‐11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schueller F, Roy S, Vucur M, Trautwein C, Luedde T, Roderburg C. The role of miRNAs in the pathophysiology of liver diseases and toxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pfaender S, Walter S, Todt D, Behrendt P, Doerrbecker J, Wölk B, et al. Assessment of cross‐species transmission of hepatitis C virus‐related non‐primate hepacivirus in a population of humans at high risk of exposure. J Gen Virol 2015;96:2636‐2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. von Hahn T, Yoon JC, Alter H, Rice CM, Rehermann B, Balfe P, et al. Hepatitis C virus continuously escapes from neutralizing antibody and T‐cell responses during chronic infection in vivo. Gastroenterology 2007;132:667‐678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prentoe J, Bukh J. Hypervariable region 1 in envelope protein 2 of hepatitis C virus: a linchpin in neutralizing antibody evasion and viral entry. Front Immunol 2018;9:2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dhingra S, Ward SC, Thung SN. Liver pathology of hepatitis C, beyond grading and staging of the disease. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:1357‐1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dittmann M, Hoffmann HH, Scull MA, Gilmore RH, Bell KL, Ciancanelli M, et al. A serpin shapes the extracellular environment to prevent influenza A virus maturation. Cell 2015;160:631‐643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trivedi S, Murthy S, Sharma H, Hartlage AS, Kumar A, Gadi SV, et al. Viral persistence, liver disease, and host response in a hepatitis C–like virus rat model. Hepatology 2018;68:435‐448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Luna JM, Scheel TKH, Rice CM, Darnell RB, Luna JM, Scheel TKH, et al. Article hepatitis C virus RNA functionally sequesters miR‐122. Cell 2015;160:1099‐1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsu SH, Wang BO, Kota J, Yu J, Costinean S, Kutay H, et al. Essential metabolic, anti‐inflammatory, and anti‐tumorigenic functions of miR‐122 in liver. J Clin Invest 2012;122:2871‐2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Divers TJ, Tennant BC, Kumar A, McDonough S, Cullen JM, Bhuva N, et al. A new parvovirus associated with serum hepatitis in horses following inoculation of a common equine biological. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24:303‐310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Walker CM. Designing an HCV vaccine: a unique convergence of prevention and therapy? Curr Opin Virol 2017;23:113‐119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bukh J, Thimme R, Meunier JC, Faulk K, Spangenberg HC, Chang KM, et al. Previously infected chimpanzees are not consistently protected against reinfection or persistent infection after reexposure to the identical hepatitis C virus strain. J Virol 2008;82:8183‐8195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bukh J, Engle RE, Govindarajan S, Purcell RH. Immunity against the GBV‐B hepatitis virus in tamarins can prevent productive infection following rechallenge and is long‐lived. J Med Virol 2008;80:87‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Al Dhahry SHS, Daar S, Nograles JC, Rajapakse SMWWB, Al Toqi FSS, Kaminski GZ. Fluctuating antibody response in a cohort of hepatitis C patients. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2002;4:33‐38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Burbelo PD, Dubovi EJ, Simmonds P, Medina JL, Henriquez JA, Mishra N, et al. Serology‐enabled discovery of genetically diverse hepaciviruses in a new host. J Virol 2012;86:6171‐6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bailey AL, Buechler CR, Matson DR, Peterson EJ, Brunner KG, Mohns MS, et al. Pegivirus avoids immune recognition but does not attenuate acute‐phase disease in a macaque model of HIV infection. PLoS Pathog 2017;13:e1006692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stapleton JT, Foung S, Muerhoff AS, Bukh J, Simmonds P. The GB viruses: a review and proposed classification of GBV‐A, GBV‐C (HGV), and GBV‐D in genus Pegivirus within the family Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol 2011;92:233‐246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schwarze‐Zander C, Blackard JT, Zheng H, Addo MM, Lin W, Robbins GK, et al. GB virus C (GBV‐C) infection in hepatitis C virus (HCV)/HIV–coinfected patients receiving HCV treatment: importance of the GBV‐C genotype. J Infect Dis 2006;194:410‐419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Melendez‐Morales L, Konkle BA, Preiss L, Zhang M, Mathew P, Eyster ME, et al. Chronic hepatitis B and other correlates of spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus among HIV‐infected people with hemophilia. AIDS 2007;21:1631‐1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material