Abstract

Students’ preferences and engagement with online educational resources and activities are crucial for academic success in the context of online medical education. This study investigated the preferences of Chinese medical students regarding the teaching strategies used by instructors and their relationship with course difficulty level, student’s academic performance, and perceived effectiveness. Survey data (n = 375) were collected from the medical students from one of the largest medical schools in Southern China during the spring semester of 2020. First, exploratory factor analysis demonstrated that there were three latent factors behind online teaching strategies, including teacher-led instructional strategies, supervised and monitored learning strategies, and self-directed learning strategies. Instructional activities under teacher supervision and monitoring received the highest rating while teacher-led strategies received the lowest ratings. Second, the popularity of the three online instructional strategies we have identified was positively associated with students’ perceived effectiveness of online teaching and their self-reported academic performance. Third, analysis of the quantified answers to the open-ended question reported a positive association between the perceived difficulty level of the courses and students’ preference of teacher-led strategies. It also manifested a positive correlation between perceived effectiveness level of the online teaching and the use of self-directed learning strategies before their online lectures. Further implications of the findings are fully discussed.

Keywords: course difficulty level, medical education online, self-directed learning, teacher instructional strategies, teacher supervision

INTRODUCTION

The challenge and barriers to online medical education have started receiving more attentions with solutions being proposed from the perspectives of management team, medial instructors, content, information, and technology infrastructure developers (1). From the student’s perspective, most of the studies addressed the facilitating conditions for promoting self-directed learning or learning autonomy (2). Institute quarantines during the pandemic in the spring semester of 2020 gave researchers a unique opportunity to explore students’ preferred online instructional strategies in the context of medical education. Adopting the survey instrument from a similar study at a higher education institute in the United States, the present study investigated the patterns or latent variables behind students’ preferred online instructional strategies and their relationships to the regularly investigated variables in the context of online medical education, such as perceived effectiveness, students’ academic performance, and course difficulty level.

Instructors’ roles or the level of involvement in online education can be descried in three ways: 1) teacher-led instructional strategies that emphasize the teachers’ role in designing, guiding, evaluating, and offering feedback; 2) scaffolding strategies that supervise, monitor, and guide students to learn in an online environment; and 3) facilitating collaborative and independent learning that highlights students’ learning motivation or self-regulated learning strategies on social media platforms or in learning management systems.

Teacher-led instructional strategies primarily refer to the use of educational technology as an extension of teachers’ classroom instruction, with some methods and strategies being directly copied from the traditional face-to-face format (3–5). There are many ways to facilitate faculty-led online teaching, such as the use of smartphone applications and learning management systems to better engage with peers and online medical learning resources in a more collaborative manner (6); audiovisual contents in a course on human anatomy to facilitate access to other online resources (7); the application of ubiquitous instruments in near-field communication to enable students to access learning management systems (8); and the use of electronic devices to enable formative assessments (9). Together, these measures effectively reduced the students’ stress and anxiety and enhanced learning outcomes. However, a recent study questioned the effectiveness of online learning in promoting learning outcomes in the context of medical laboratory science (10).

Learning under a teacher’s supervision and monitoring contributes to improving education quality via enhancing teachers’ teaching skills and supervisory practices in the classroom (11). The supervision or continuous support from teachers is essential for fulfilling and improving the outcomes of classroom teaching, especially in clinical medical education (12) and healthcare training programs (13). Notably, supervision during teaching may be offered by teachers and peers if the supervisors are experienced in the field (14); however, the efficacy of student supervision is sometimes questionable (15), which is probably because of their relatively poor social cohesion or the short intervention duration (16). In some cases, the support was reported to be at the faculty level, where staff interactions and guidance of students’ contributions were identified as facilitating factors for a highly satisfactory learning experience (17).

Last, self-directed learning indicates that students implement learning via the completion of preclass learning content covering the general knowledge in the upcoming lectures (18). With the help of preclass learning, students perform more actively in the classroom, which may increase medical students’ exposure to terminology (19) and transform the classroom from a didactic format to an active learning environment (20). Nevertheless, there have been controversial opinions regarding preclass learning or encouraging students to study the material in a learning management system before classes begin. This controversy primarily exists because of failure to completely fulfil the learning outcomes in some cases compared to counterparts in a traditional face-to-face format (21). Many factors may be involved in this discrepancy, such as differences in the students’ abilities to cocreate and coregulate during their studies (22), the lack of instructors’ guidance and assistance in facilitating understanding of the learning materials before the classes (23), and students’ receptivity to prelecture learning activities (24).

Bearing in mind the fact that there are three types of online instructional strategies, the present study asked two questions: 1) what are the latent variables behind students’ preferred online instructional strategies? and 2) what variables predict students’ preferences regarding online instructional strategies?

METHODS

Research Context and Participants

The present study was performed among the students of clinical medicine major at Jinan University, Guangzhou, China. The sum of the students of clinical medicine was 814, and a total of 565 questionnaires were received in this survey, with a response rate of 69.4%. We eventually verified the validity of 375 questionnaires (efficacy rate was 66.4%) after discarding 156 invalid questionnaires based on the following criteria: 1) the incomplete answers; 2) the mean value of the questionnaire completion time was either >284.49 (maximal) or <18.16 (minimal) seconds (note: the average value was 151.33 ± 133.17 s); 3) the average SD ± mean values in all the 12 items (i.e., 8.1–8.12 about the teaching strategies in the survey) was either 0 or 0.276 (i.e., the respondent selected either all the same answers or only one different answer in the survey). Of the 375 respondents, there were 179 (47.7%) males and 196 (52.3%) females, 105 (28.0%) were freshmen, 120 (32.0%) were sophomores, 75 (20.0%) were third-year students, 74 (19.7%) were fourth-year students, 1 (0.3%) was a fifth-year student, 265 (70.7%) were domestic students, and 110 (29.3%) were international students.

Survey Implementation

The survey instrument was designed to collect information about the medical students’ preferences toward the “stopgap” online teaching of medical education, including basic medical and clinical sciences, in China during the Covid-19 pandemic, which lasted from mid-February 2020 until mid-July 2020. This survey concentrated on clinical medicine students only, who were studying basic medical or clinical medical sciences via online courses at Jinan University School of Medicine during the pandemic. The items of the survey instrument were modified from a previous literature (25) and developed for use in Chinese (see appendix i for the translated English version). The survey was first piloted with faculty members to ensure the clarity of the questionnaire, and it was revised based on feedback to a small degree. We used messaging groups for medical students at Jinan University School of Medicine in the WeChat application, which is a popular social media mobile application (26), to distribute the questionnaire. An invitation for the medical students to voluntarily complete the survey using the online survey platform Sojump was disseminated to the group’s members (27). After 50 answers had been collected by Sojump, the survey was suspended temporally for reliability analysis, 48 answers were verified as valid, Cronbach α of the 12 items modified from Martin et al. (25) was 0.929, showing good reliability of the survey instrument. The survey was reactivated immediately. Before implementing the survey, all study staff were well trained, and the participating students were informed that the relevant material would be treated in the strictest confidence. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinan University (No. MJNER202004012).

Measures

The survey includes four parts: 1) demographic information; 2) three well-documented variables that may impact students’ preferences regarding instructional strategies (difficulty level, academic performance and perceived effectiveness); 3) a list of recommend instructional strategies for online teaching environments (translated from the study of Martin et al. in 2018); and 4) one optional open-ended question which invites students to recommend their preferred one online instructional strategy. For the third part, the participants are invited to rate the 12 online instructional strategies using a 6-point Likert-type scale with 1 = not helpful at all and 6 = extremely helpful.

Data Analysis

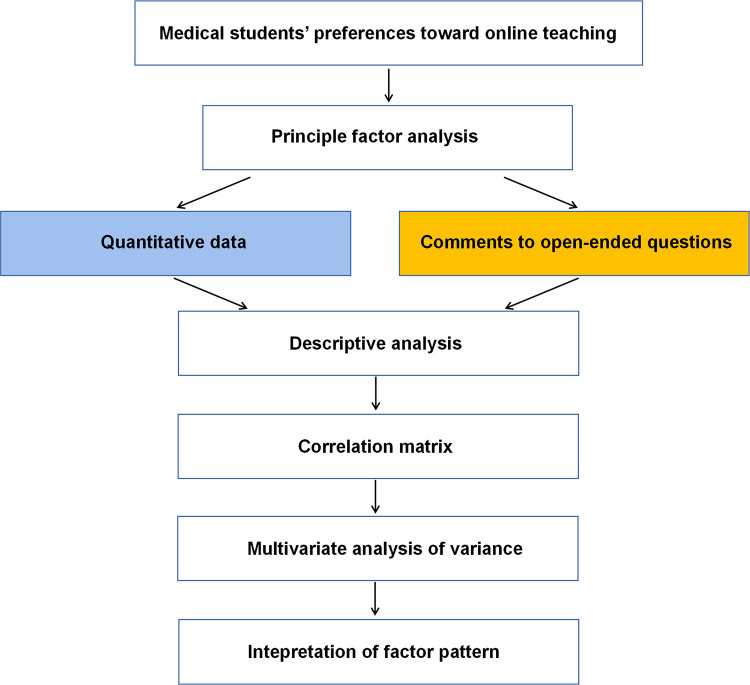

To answer the first research question, SPSS 20.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) (28) was used to perform descriptive statistics and exploratory factor analyses. To answer the second research question, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to test the relationship between students’ preferences regarding instructional strategies and the three research-backed influential factors in general education: students’ academic performance, perceived difficulty level, and perceived effectiveness of instructors’ work. Based on the identified numbers of latent factors from the results of the factor analysis in step one, students’ responses to the open-ended question were labeled and categorized into several groups. The data were first analyzed to identify repeating themes, and then the decision regarding the categorization of teaching strategies was made on the basis of the key words in the comments. The first author and first corresponding author independently tagged the key words in the comments with a “code,” and any discrepancy was discussed to ensure consistency. The ANOVA tests was conducted to identify the associations between their categories and the ratings to the three questions in part two. In other words, the results suggested the relationship between the most preferred online instructional strategy and self-reported academic performance, perceived difficulty level, and perceived effectiveness of the instructors’ work. A total of 274 participants’ answers were analyzed, and 101 data entries were excluded for three reasons: 1) no comments were left; 2) only emojis were left; and 3) the answers were too short for proper coding. Figure 1 shows the key components of exploratory factor analysis used in this study. The results of the statistical analyses are presented as means ± SD and considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of exploratory factor analysis based online teaching strategies extraction.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

To investigate the patterns underlying the medical students’ feedback regarding online medical education, we implemented principal factor analysis for the 375 valid questionnaires. The results showed that three main factors were identified on the basis of the levels and implications of medical students’ expected responses to each question (Table 1). The three main factors were teacher instructional strategies, learning under teacher’s supervision and monitoring, and self-directed learning and goal-setting strategies, which were called factor 1, factor 2, and factor 3, respectively, in Table 1. These results suggested that the medical students identified these three factors as having important influences on their medical studies via a remote/online format during the Spring 2020 semester. Although the total three factors could only explain for 55.6% of the whole variance, and the three factors did not cover all of their preferences, they may provide an effective index for evaluating significant differences in the perceptions of medical students, who were divided into various groups by different properties, such as gender, grade, and country of origin. Table 2 reports the descriptive data for the three newly identified factors. The results of the survey suggested that the most preferred online instructional strategies were instructional activities under teacher supervision and monitoring or those involving interactions between teachers and students. Notably, the least preferred instructional strategy was teacher-led teaching, which indicates that students may be willing to take more responsibility in managing and controlling their learning process.

Table 1.

Summary of the principal factors analysis of the questionnaire with online learning students

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15. Instructors provided feedbacks/remarks via various modalities on assignments. | 0.687 | ||

| 19. Instructors helped students learn online through providing home-made asynchronous recorded broadcasting. | 0.651 | ||

| 14. Instructors timely responded to students’ assignments and provided remarks. | 0.641 | ||

| 16. Instructors encouraged student reflection about their online learning experience, and provided feedbacks and guidance. | 0.625 | ||

| 18. Instructors encouraged student reading through increasing interactive visual syllabi of the course. | 0.580 | ||

| 17. Instructors interacted with students in an online course using various synchronous features. | 0.521 | ||

| 11. Instructors timely responded to students’ questions via forums, social media, or email. | 0.817 | ||

| 10. Students communicated with the instructors timely via various approaches. | 0.742 | ||

| 12. Instructors often provide the announcement information to students via notice, message, or email. | 0.652 | ||

| 13. Instructors often appear in in the discussion forums. | 0.604 | ||

| 8. Before an online course, instructor introduced her/his educational backgrounds, working experiences, expectation, via asynchronous recorded broadcasting or voice communication. | 0.707 | ||

| 9. Before an online course, instructor introduced learning methods of the course via asynchronous recorded broadcasting to help students become familiar with online learning platforms. | 0.576 | ||

| r | 0.841 | 0.863 | 0.647 |

| Cumulative variance percent | 23.2% | 23.1% | 9.3% |

| Key factors | Teacher’s instructional strategies | Learning under teacher’s supervision and monitor | Self-directed learning and goal-setting |

Extraction methods: principle axis factoring. Rotation methods: Varimax Kaiser normalization (KMO = 0.882). The number of factors were determined by the eigenvalues extracted >1; r, reliability. KMO, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure.

Table 2.

Descriptive data for the three identified factors

| Factors | n | Rating | Means (SD) | Skew |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervision and monitoring | 4 | 19.925 | 4.981 (11.775) | −0.929 |

| Self-directed | 2 | 8.078 | 4.039 (4.034) | −0.400 |

| Teacher instructional strategies | 6 | 23.765 | 3.961 (16.808) | −0.518 |

Rating, overall rating of the factor; mean, mean of each item of the factor; n, no. of the related items of the survey.

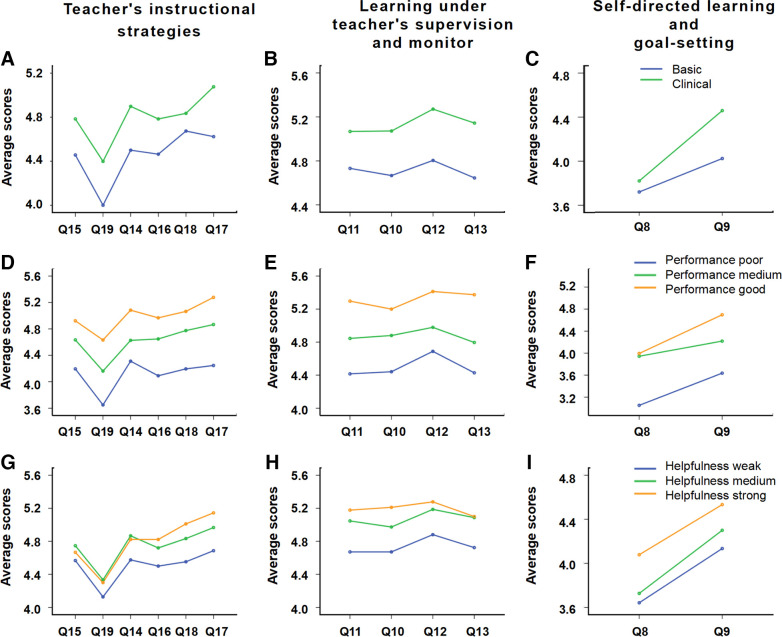

The MANOVA results indicated that the students exhibited various preferences of online instructional strategies based on their reported academic performance (F = 3.809, df = 6, Pillai’s Trace = 0.060, P = 0.001), and students’ perception of effectiveness (F = 16.155, df = 6, Pillai’s Trace = 0.231, P = 0.000). Better academically performing medical students and those who believed the online course are highly effective in improving their learning gains, gave higher recognition of the three identified types of online instructional strategies (Fig. 2, D–I). Moreover, the correlations were examined between these three factors and the following dependent variables: the medical students’ gender (male or female), grade (freshmen, sophomore, third-year student, fourth-year student), and the country of origin of the students (mainland China or overseas) (Table 3). The results demonstrated that the values of the Pillai’s Trace for medical students’ gender, grade, and country of origin were F = 0.086 (P = 0.968), F = 1.095 (P = 0.360), and F = 1.508 (P = 0.212), respectively, which suggested that medical students’ preferences of the three types of online instructional strategies were not significantly associated with their genders, grades, and country of origin.

Figure 2.

The correlations between the scores for each question in the three groups (i.e., course attribute, academic performance, and perception of helpfulness) and the recognized 3 key factors. A–I: A–C: from the group of medical course attributes; D-F: from the group of students’ academic performance; G–I: from the group of students’ perception of helpfulness. The vertical axis is the scores of each question in the survey, and the horizontal axis represents the series number of the question.

Table 3.

Demographic statistics of the survey respondents

| Items (n) | Teacher’s Instructional Strategies | Learning Under Teacher’s Supervision and Monitor | Self-Directed Learning and Goal Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male (179) | 23.747 (3.721) | 19.911 (3.157) | 8.022 (1.949) |

| Female (196) | 23.770 (4.425) | 19.933 (3.664) | 8.122 (2.061) |

| Grade | |||

| 1 (105) | 23.886 (4.152) | 20.391 (3.353) | 7.800 (2.216) |

| 2 (120) | 23.767 (4.379) | 19.858 (3.586) | 8.233 (1.990) |

| 3 (75) | 23.333 (3.703) | 19.373 (3.299) | 8.080 (2.078) |

| 4 (74) | 24.027 (3.986) | 19.932 (3.393) | 8.216 (1.616) |

| Students’ origin | |||

| Mainland (265) | 23.917 (4.249) | 20.045 (3.500) | 8.008 (1.992) |

| Oversea (110) | 23.364 (3.702) | 19.627 (3.242) | 8.236 (2.041) |

| Courses’ attribute | |||

| Basic medicine (138) | 22.717 (4.472) | 18.848 (3.714) | 7.739 (2.173) |

| Clinical medicine (237) | 24.359 (3.744) | 20.549 (3.088) | 8.270 (1.881) |

| Academic performance | |||

| Good (90) | 24.467 (3.567) | 20.767 (2.915) | 8.611 (1.816) |

| Medium (150) | 24.133 (4.023) | 20.293 (3.136) | 8.027 (1.959) |

| Poor (135) | 22.859 (4.375) | 18.948 (3.823) | 7.770 (2.119) |

| Degree of difficulty | |||

| Easy (80) | 24.050 (4.647) | 20.213 (3.896) | 8.10 (2.191) |

| Medium (165) | 23.685 (3.858) | 20.067 (3.047) | 7.994 (1.946) |

| Difficult (130) | 23.662 (4.061) | 19.562 (3.570) | 8.162 (1.976) |

| Perception of helpfulness | |||

| Weak (77) | 21.039 (4.652) | 17.974 (4.280) | 6.688 (2.166) |

| Medium (143) | 23.525 (3.506) | 19.497 (3.023) | 8.154 (1.503) |

| Strong (155) | 25.316 (3.549) | 21.284 (2.670) | 8.690 (2.008) |

Values are means (SD).

The open-ended questions contained the respondents’ comments of instructional strategy. The qualitative data of the open-ended questions were categorized into the numbers of 1, 2, and 3 (i.e., 1 = teacher instructional strategy; 2 = teacher supervision; and 3 = self-directed learning). Ninety-eight responses recommended instructional strategies that belonged to the first factor (teacher-led instructional strategies). The students expressed their opinions as “we prefer teachers live broadcasting to the MOOCs provided by other universities,” “I’d suggest the teacher use more examples to help understand and integrate the knowledge with clinical medicine”, and “it would be much better that teachers deliver courses by fixed platform,” etc. Forty-nine answers recommended strategies linked to the second factor (supervised and monitored-learning). The comments of the students preferred this kind of instructional strategy was given as “I like to interact with teachers during or after class,” as well as “we need more supervision from teachers”, and “I expect teachers could regularly check my learning on MOOCs,” etc. In addition, 127 of the recommended strategies were linked to the third factor (strategies that promoted self-directed learning). These students usually expressed their demanding as “could teacher share more preclass learning materials, exercises and self-checking quizzes with us?” etc. The quantified data are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Descriptive data for the quantified comments to the open-ended question

| Category | n | Self-Reported Academic Performance | Perceived Difficulty Level | Perceived Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 98 | 6.020 (1.995) | 7.214 (1.459) | 6.531 (2.006) |

| 2 | 49 | 6.020 (1.931) | 6.429 (1.291) | 7.082 (1.644) |

| 3 | 127 | 6.386 (1.728) | 6.961 (1.606) | 7.197 (1.528) |

Values are means (SD); n, no. of the comments related to each of the 3 identified factors.

ANOVA tests were performed to identify correlations between respondents’ recommended instructional strategies and their answers to the three questions in the second part of the survey (students’ academic performance level and their effectiveness in helping students learn in an online environment) (Table 5). The results demonstrated significant differences in the rated difficulty levels (F = 4.471, df = 2, P = 0.012), and the effectiveness of the teacher’s online teaching (F = 4.291, df = 2, P = 0.015) among the three groups based on their recommended instructional strategies. The participants who recommended more teacher-led instructional strategies in the open-ended questions reported a significantly higher difficulty level than their counterparts. Participants who recommended that teachers promoted self-directed learning strategies reported a significantly higher level of effectiveness than the other two groups. Therefore, medical students who believed that their teachers delivered effective instructions asked for more guidance or opportunities to plan and organize their own learning process.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of academic performance, degree of difficulty and students’ perception of helpfulness, classified by different teaching strategies comments

| 95% Confidence Interval |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | Comments (I) | Comments (J) | Means (SD) | P | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Academic performance | 1 | 23 | 0.000 (0.326) −0.365 (0.251) |

1.000 0.146 |

−0.642 −0.859 |

0.642 0.128 |

| 2 | 13 | 0.000 (0.326) −0.365 (0.313) |

1.000 0.245 |

−0.642 −0.982 |

0.642 0.252 |

|

| 3 | 12 | 0.365 (0.251) 0.365 (0.313) |

1.000 0.245 |

−0.642 −0.252 |

0.642 0.982 |

|

| Degree of difficulty | 1 | 23 | 0.786 (0.263)* 0.254 (0.202) |

0.003 0.210 |

0.268 −0.144 |

1.303 0.651 |

| 2 | 13 | −0.786 (0.263)* −0.532 (0.253)* |

0.003 0.036 |

−1.303 −1.029 |

−0.268 −0.035 |

|

| 3 | 12 | −0.254 (0.202) 0.532 (0.253)* |

0.210 0.036 |

−0.651 0.035 |

0.144 1.029 |

|

| Perception of helpfulness | 1 | 23 | −0.551 (0.303) −0.666 (0.233)* |

0.070 0.005 |

−1.148 −1.125 |

0.046 −0.207 |

| 2 | 13 | 0.551 (0.303) −0.115 (0.291) |

0.070 0.693 |

−0.046 −0.689 |

1.148 0.459 |

|

| 3 | 12 | 0.666 (0.233)* 0.115 (0.291) |

0.005 0.693 |

0.207 −0.459 |

1.125 0.689 |

|

I and J: different groups of the comments related to each of the 3 identified factors (post hoc multiple comparisons, Bonferroni). 1, Teacher’s instructional strategies; 2, learning under teacher’s supervision and monitor; 3, self-directed learning and goal-setting. *P < 0.05 by ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated medical students’ preferences for online instructional strategies and predictive variables regarding their preferences in the context of Chinese medical schools during the Covid-19 pandemic of the Spring 2020 semester. The answers to the research questions revealed three lessons.

First, the identified three online instructional patterns that was produced from the proposed 12 online instructional strategies are consistent with data from previous studies, i.e., teaching effectiveness that includes an online format greatly depends on how teachers guide and facilitate students to fulfil the academic goals using various teaching measures, active engagement, and presence (29, 30). The descriptive data revealed that teacher-led or teacher-centered online instructional strategies were not the most preferred strategies, implying that medical students may be more willing to share the responsibility in online learning environments. This result echoed the current trend in emphasizing the sustainability of learning and personal responsibility in online education, with a certain level of intervention and engagement from senior peers or instructors (31).

Second, the popularity of the three identified online instructional strategies was significantly associated with students’ perceived effectiveness and their self-reported academic performance. The survey was anonymous, so that the analysis of learning outcome involved with the students’ perceived performance rather than actual academic performance. The students’ performances in all modules are graded on a scale of 100 at Jinan University, so it should be easier for the students to convert and report their academic performance on a scale of 10 in the survey. In relation to the correlation between students’ academic performance and the choice of online learning strategies, previous studies mainly concluded that low-performing medical students could benefit more from blended learning than high-performing students (32) and not all medical students could easily adopt a discussion based on self-directed learning strategies that might fit the online learning environment (33), especially for those low-performing students (34). This study argues that high-performing students may hold a more positive attitude toward online teaching than their low-performing counterparts in regard of instructors’ choices of teaching strategies. To fulfill the gap, the solutions may need be comprehensive, which include a jointed effort from course designers, information technology experts, academic skill advisors, and course instructors (1); therefore, the choice of online instructional strategies is not the key to help low-performing students to improve learning outcomes. Bearing in mind the close relationship between academic performance and perceived effectiveness of teaching in an online environment, it is not surprising that poor performing students who considered online learning experience as ineffective reported a low rating in all types of online instructional strategies. Again, the answers to the challenge may include teacher instructional strategies, teacher presence and engagement, prompt responses from teachers to student questions, and faculty implementation of learning management systems, which has been proven to be a determinant of perceived student learning, satisfaction, and academic success (29).

Third, the quantitative analysis for the open-ended question revealed a positive association between the students’ perceived difficulty level of the courses and students’ preference of teacher-led strategies. Meanwhile, it also displayed a positive association between students’ perceived effectiveness of the online teaching and preference of instructional strategies that promote self-directed learning. The above results suggest that the availability or prereview of learning resources before the online lectures may help students better understand the classes and consequently has the potential to reduce the level of cognitive load. It echoes with the recommendation from previous studies that asked the course designer to consider the level of curricular difficultly in curriculum arrangements and provide personalized curricula based on the actual situation of each student (35).

Limitations of This Study

The present study has strengths but also several limitations. The first limitation is that there were no comparisons between traditional face-to-face teaching and online teaching, especially separating the medical theoretical sessions from the practical sessions during the pandemic. The second limitation is that the snapshot of respondents may not reflect the longitudinal educational scene well. The conclusions stemmed from one survey at the Jinan University School of Medicine may not be completely suitable for other medical schools because there are different teaching facilities and instructional strategies that may impact the perceptions of medical students regarding online medical education. Regarding to the third limitation, the strategy for cleaning survey data was based on the calculation of total completion time, as well as answer choices being all/mostly the same, which might be incorrect assumptions and consequently lead to deviation from the real situations. Lastly, there are only two items combined to define the third latent variable, so that it probably is not so convincing to constitute an effective index for the “self-directed” factor. The theoretical frame of the latent variables is certainly required to be further refined in the future.

GRANTS

This study was supported by Pedagogical Reform Grant of High Education at Guangdong Province 2019-60 (to X Cheng); Grant of China Association of Higher Education 2020JXYB08 (to X. Cheng), and The Postgraduates Education Achievements Cultivating Projects of 2020 at Jinan University (to X. Cheng).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X.C. conceived and designed research; X.C., C.-H.L., and J.C. performed experiments; X.-Y.M. and W.W. analyzed data; W.W. interpreted results of experiments; X.-Y.M. prepared figures; X.Y. drafted manuscript; X.C., X.-Y.M., W.W., and X.Y. edited and revised manuscript; X.C., X.-Y.M., C.-H.L., J.C., W.W., and X.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors sincerely thank all of those who completed this survey.

APPENDIX I. THE TRANSLATED ENGLISH VERSION OF THE QUESTIONNAIRE

The Questionnaire of Chinese Medical Students’ Perception toward Online Medical Education during the Pandemic

We sincerely thank you for participating in this survey on your learning experience and preference of online medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey results will help us identify pedagogical problems and improve the design and quality of our online courses afterwards. The questionnaire contains 20 questions, and it will take a few minutes to complete. There are no correct answers for these questions. Please answer them based on your experience of online learning for the spring semester 2020. We pledge to keep all data anonymous, and personal information will not be disclosed. Thank you very much again for your participation.

-

1.

I am a _____

-

1)

Freshmen

-

2)

Sophomore

-

3)

Third-year student

-

4)

Fourth-year student

-

5)

Five-year student

-

1)

-

2.

My gender is _____

-

1)

Male

-

2)

Female

-

1)

-

3.

I am a _____

-

1)

Domestic student

-

2)

International student (including those come from Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan)

-

1)

-

4.

Please indicate your academic performance on a scale of 10: 1 = extremely low-performing, 10 = excellent

-

5.

The type of your course

-

1)

Basic medical sciences (e.g., anatomy, histology, and embryology, physiology, biochemistry, pathology, pharmacology, immunology and microbiology, and pathophysiology)

-

2)

Clinical medical sciences (e.g., diagnostics, medicine, surgery, obstetrics & gynaecology, paediatrics, evidence-based medicine, medical ethics, medical psychology)

-

1)

-

6.

Please indicate the difficulty level of your course on a scale of 10: 1 = very easy and 10 = extremely challenging

-

7.

Please indicate the effectiveness of your teachers’ online instructional performance

On a scale of 10: 1 = not helpful at all, 10 = extremely helpful

-

8. Please indicate the effectiveness of the following 12 instructional strategies on a scale of 6: 1 = not helpful at all and 6 = extremely helpful

-

8.1Before an online education course, the instructor introduced herself/himself, such as educational backgrounds, working experiences, learning outcome expectation, via asynchronous recorded broadcasting or voice communication.

-

8.2Before an online education course, the instructor introduced the orientation and learning methods of the course via asynchronous recorded broadcasting for helping students become familiar with the functions of online learning platforms.

-

8.3Students communicated with the instructors timely via various approaches (e.g., forums, email, telephone, or social media)

-

8.4Instructors timely responded to students’ questions or requests via forums, social media, or email.

-

8.5Instructors often provide the announcement information (e.g., course arrangement, reminders of exam timetable, assignment submission) to students via notice, message, or email.

-

8.6Instructors often appear in the discussion forums (e.g., sharing information or communicating with students, participating in students’ discussion).

-

8.7Instructors timely responded to students’ assignments or exams and provided their remarks.

-

8.8Instructors provided feedbacks/remarks via various modalities (e.g., audio, video, and comment texts etc.) on assignments.

-

8.9Instructors encouraged student reflections about their online learning experiences (e.g., difficulties and bewilderment etc.), and provided the positive feedbacks and guidance.

-

8.10Instructors interacted with students in an online course using various synchronous features (e.g., audio and video chat, synchronous polling etc.).

-

8.11Instructors encouraged student reading through increasing interactive visual syllabi of the course (e.g., increase of teaching videos, images and web links of other interactive components etc.)

-

8.12Instructors helped students learn online through providing home-made asynchronous recorded broadcasting.

-

8.1

-

9.

Could you please recommend one more instructional strategy for us to consider?

REFERENCES

- 1.O’Doherty D, Dromey M, Lougheed J, Hannigan A, Last J, McGrath D. Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education–an integrative review. BMC Med Educ 18: 130, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peine A, Kabino K, Sprekelsen C. Self-directed learning can outperform direct instruction in the course of modern German medical curriculum–results of a mixed methods trail. BMC Med Educ 16: 130, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0650-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook KC, Grant-Davis K. Online Education: Global Questions, Local Answers. England: Routledge, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loda T, Loffler T, Erschens R, Zipfel S, Herrmann-Werner A. Medical education in times of COVID-19: German students’ expectations-across-sectional study. PLoS One 15: e0241660, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobko S, Unadkat D, Adams J, Hull G. Learning through collaboration: a networked approach to online pedagogy. E-Learn Digital Media 17: 36–55, 2020. doi: 10.1177/2042753019882562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurt M, Bensen H. Six seconds to visualize the word: improving EFL learners’ vocabulary through VVVs. J Comp Assist Learn 33: 334–346, 2017. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi-Lundberg DL, Cuellar WA, Williams A M. Online dissection audio-visual resources for human anatomy: Undergraduate medical students’ usage and learning outcomes. Anat Sci Educ 9: 545–554, 2018. doi: 10.1002/ase.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen CW, Wu YC, Lee TC. Developing a NFC-equipped smart classroom: effects on attitudes toward computer science. Comp Human Behav 30: 731–738, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun JC. Influence of polling technologies on student engagement: An analysis of student motivation, academic performance, and brainwave data. Comp Educ 72: 80–89, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doggrell SA. No apparent association between lecture attendance or accessing lecture recordings and academic outcomes in a medical laboratory science course. BMC Med Educ 20: 207, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02066-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mette IM, Range BG, Anderson J, Hvidston DJ, Nieuwenhuizen L. Teachers’ perceptions of teacher supervision and evaluation: a reflection of school improvement practices in the age of reform. Educ Leadership Rev 16: 16–30, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acheson KA, Gall MD. Techniques in the Clinical Supervision of Teachers. Preservice and Inservice Applications (Online). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED278159. ERIC, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chisholm A, Byrne-Davis L, Peters S, Beenstock J, Gilman S, Hart J. Online behaviour change technique training to support healthcare staff ‘Make Every Contact Count’. BMC Health Serv Res 20: 390, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05264-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Parsons D, Kwon G, Kim J, Petrova K, Jeong E, Ryu H. Cooperation begins: encouraging critical thinking skills through cooperative reciprocity using a mobile learning game. Comp Educ 97: 97–115, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heflin H, Shewmaker J, Nguyen J. Impact of mobile technology on student attitudes, engagement, and learning. Comp Educ 107: 91–99, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruhalahti S, Korhonen AM, Rasi P. Authentic, dialogical knowledge construction: a blended and mobile teacher education programme. Educ Res 59: 373–390, 2017. [doi: 10.1080/00131881.2017.1369858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole D, Rengasamy E, Batchelor S, Pope C, Riley S, Cunningham AM. Using social media to support small group learning. Bmc Med Educ 17: 201, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han E, Klein KC. Pre-class learning methods for flipped classrooms. Am J Pharm Educ 83: 6922, 2019. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Ali A, Kamal F, Cabral CL, Squires JH. Comparison of traditional and web-based medical student teaching by radiology residents. J Am Coll Radiol 16: 492–495, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen JL, Holt EA, Sowards JB, Ogden TH, West RE. Investigating strategies for pre-class content learning in a flipped classroom. J Sci Educ Tech 27: 523–535, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s10956-018-9740-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karabulut-Ilgu AJ, Cherrez N, Jahren CT. A systematic review of research on the flipped learning method in engineering education. Brit J Educ Tech 49: 398–411, 2018. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blau I, Shamir-Inbal T. Re-designed flipped learning model in an academic course: the role of co-creation and co-regulation. Comp Educ 115: 69–81, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieu R, Wong A, Asefirad A, Shaffer JF. Improving exam performance in introductory biology through the use of preclass reading guides. CBE Life Sci Educ 16: ar46, 2017. doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-11-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNally B, Chipperfield J, Dorsett P, Del Fabbro L, Frommolt V, Goetz S, Lewohl J, Molineux M, Pearson A, Reddan G, Roiko A, Rung A. Flipped classroom experiences: student preferences and flip strategy in a higher education context. High Educ 73: 281–298, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0014-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin F, Wang C, Sadaf A. Student perception of helpfulness of facilitation strategies that enhance instructor presence, connectedness, engagement and learning in online courses. Internet High Educ 37: 52–65, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2018.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gan C, Wang W. Uses and gratifications of social media: a comparison of microblog and WeChat. J Syst Info Techn 17: 351–363, 2015. doi: 10.1108/JSIT-06-2015-0052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Wen D, Liang J, Lei J. How the public uses social media wechat to obtain health information in china: a survey study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 17: 66–79, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0470-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes AF. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav Res 50: 1–22, 2015. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorsky P, Blau I. Online teaching effectiveness: a tale of two instructors. IRRODL 10: 2009. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v10i3.712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorsky P, Caspi A. Dialogue: a theoretical framework for distance education instructional systems. Brit J Educ Tech 36: 137–144, 2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00448.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clarke E, Burns J, Bruen C, Crehan M, Smyth E, Pawlikowska T. The ‘connectaholic’ behind the curtain: medical student use of computer devices in the clinical setting and the influence of patients. BMC Medical Education 19: 376, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1811-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herrero J, Quiroga J. Flipped classroom improves results in pathophysiology learning: results of a nonrandomized controlled study. Adv Physiol Educ 44: 370–375, 2020. doi: 10.1152/advan.00153.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lima K, Neves B, Ramires C, Soares M, Martini V, Lopes L, Mello-Carpes P. Student assessment of online tools to foster engagement during the COVID-19 quarantine. Adv Physiol Educ 44: 679–683, 2020. doi: 10.1152/advan.00131.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ainscough L, Leung R, Colthorpe K. Learning how to learn: can embedded discussion boards help first-year students discover new learning strategies? Adv Physiol Educ 44: 1–8, 2020. doi: 10.1152/advan.00065.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CM, Liu CY, Chang MH. Personalized curriculum sequencing utilizing modified item response theory for web-based instruction. Expert Syst Appl 30: 378–396, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2005.07.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]