Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic forced teaching to be shifted to an online platform. Since the flipped teaching (FT) model has been shown to engage students through active learning strategies and adapt both synchronous and asynchronous components, it was a convenient choice for educators familiar with this instructional method. This study tested the effectiveness of a virtual FT method during the pandemic in a graduate-level physiology course. Besides assessing knowledge gained in the virtual FT format, student surveys were used to measure student perception of their adjustment to the new FT format, their confidence in completing the course successfully, and the usefulness of assessments and assignments in the remote FT. Students reported that they adjusted well to the remote FT method (P < 0.001), and their confidence in completing the course in this teaching mode successfully improved from the beginning to the end of the semester (P < 0.05). Students expressed a positive response to the synchronous computerized exams (90.32%) and the formative group (93.51%) and individual (80.65%) assessments. Both collaborative activities (93.55%) and in-class discussions (96.77%) were found to be effective. The course evaluations and the overall semester scores were comparable to the previous semesters of face-to-face FT. Overall, students’ perceptions and performance suggested that they embraced the virtual FT method and the tested teaching method maintained the same strong outcome as before. Thus, this study presents a promising new instructional method in the teaching of future physiology courses.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, flipped teaching, student assessment, virtual teaching

INTRODUCTION

The novel Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) had an enormous impact on everyone across the globe. As the closing of schools and universities emerged, face-to-face interactions were precluded and adjustments had to be made to ensure that students could still learn. Embracing technology and innovation was inevitable, as online teaching received the greatest attention (1, 2). Most universities quickly incorporated essential technology to deliver online education through platforms such as Zoom, which had already proven to have high levels of engagement among users (3).

After a short period of disorientation, remote teaching became the new norm, and educators began developing creative modes of delivery and facilitation of learning (1, 4, 5). Johnson et al. (4) surveyed faculty members at a university to assess their practices and approaches during this pandemic. The techniques endorsed by the faculty included the distribution of materials via the institution’s Learning Management System, virtual synchronous meetings for discussion using options such as Zoom, GoToMeeting, and Google Hangouts, and asynchronous lectures developed by the instructor or from external sources such as YouTube, institutional conference/chat functions, and communicating via social media. Many faculty reported using both asynchronous and synchronous formats (4). The pandemic-led changes in the classroom significantly impacted students as well. Students who attended real-time online sessions (synchronous virtual meetings) reported that it was helpful to have a space to ask questions directly (6).

There is strong evidence to suggest that active learning techniques promote student engagement (7–10). More specifically, flipped teaching (FT) is beneficial to students since this method exposes students to course content, including lectures, before their in-class meeting, which offers time for interaction and engagement with their instructor and peers during the synchronous sessions (2, 11–13). Since FT design is built around students reviewing course content virtually in their individual spaces before their synchronous class time, this method became one of the most appropriate choices during the pandemic.

Certain modifications were made to the FT format to meet the virtual model. Chick et al. (14) examined surgical resident education by placing students into two separate tracks in the “classroom” to allow more interaction. A novel social media-based platform was used through Facebook, allowing daily exposure to practice questions to discuss educational topics without the requirement for in-person meetings (14). Similarly, other modifications to FT have been tested and deemed successful. In a study by Sabharwal et al. (15), medical students completed a structured flipped classroom curriculum that consisted of prerecorded webinars and assigned readings and review questions in preparation for a faculty-led teleconference. These adaptations also exposed students and residents to real-life examples of a systems-based practice.

This study aimed to design and test a virtual FT method to meet the needs of remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic and evaluate its effectiveness. Any innovations in the development of flexible and practical instructional and assessment tools and lessons learned while implementing remote FT could help guide future virtual classroom design.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virtual Blended Flipped Classroom Design

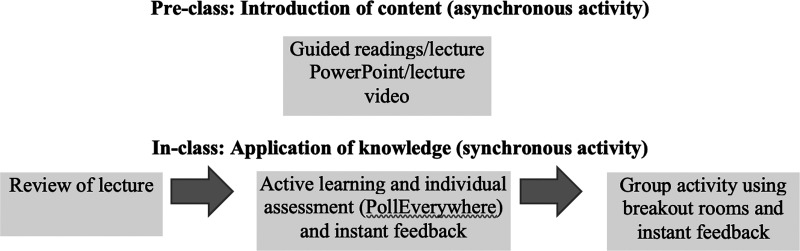

A graduate-level physiology course that was scheduled to be taught in a face-to-face setting was switched to an online platform because of the lockdown during COVID-19. The class met for 2 h in the synchronous mode 2 days per week, along with two virtual office hours immediately before each of the synchronous sessions. The learning management system (Blackboard) was used to communicate with students, for post-course content, to allow discussion, to conduct computerized exams, and to maintain a grade book. This course utilized an in-house E-textbook authored by the instructor teaching the course. Many other physiology textbooks were listed as references. Students were introduced to the Blackboard page and the course via a welcome video before the semester. The course page contained reading assignments, lecture videos, and lecture slides for the entire semester. Students accessed remote synchronous sessions through the media platform Zoom. They were encouraged to ask questions about the assigned course content during the synchronous sessions and have their questions answered by the instructor in real time, often as mini lectures. A Wacom tablet with a whiteboard feature was used to list student questions as received and to explain the topics by drawing structures or flowcharts as needed. Both formative and summative assessments were built into the course, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flipped classroom design. The course design included a combination of synchronous and asynchronous components.

Study Participants

This study was conducted over 12 wk and included 35 graduate students [n = 9 (25%) male and n = 26 female (75%)] in a 500-level summer course entitled Advanced Human Physiology. Thirty-two students (92%) were student registered nurse anesthetists (SRNAs), and three (8%) were students in a nurse practitioner (NP) program. This course was a requirement in their first semester of a 3-yr doctoral program and was taught and managed by a single faculty member. One SRNA deferred starting the class the following year because of personal reasons. One NP student withdrew after the first exam, leading to a final total of 33 students (31 SRNA and 2 NP students). The demographic details of the student participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the student participants

| Characteristics | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 9 (27.3%) |

| Female | 24 (72.7%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 25 (75.8%) |

| African American | 5 (15.2%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (9%) |

| Native American | 0 (0%) |

Ethical Considerations

The university’s Institutional Review Board approved this study with the exempt status (Protocol No. 639).

Formative Assessments

An individual assessment was conducted during the synchronous period soon after the question-and-answer session with the university-licensed application called PollEverywhere. Students received immediate feedback once this assessment was completed. Nevertheless, another formative assessment included a small group activity using the Breakout Rooms via Zoom. The teams were constructed on the first day of the semester with a five-question survey report that gathered details such as gender, grade point average (GPA), and ethnicity to intentionally construct the teams to be as heterogeneous as possible (16). The groups consisted of four or five students, and these groups remained permanent throughout the semester.

Summative Assessment

There were four major exams in total that were ∼3 wk apart. These exams were conducted virtually with the Respondus LockDown Browser combined with the monitor feature. Students were given 50 min to complete the 50-question exam during their scheduled synchronous class time.

First-Day and Last-Day Quizzes

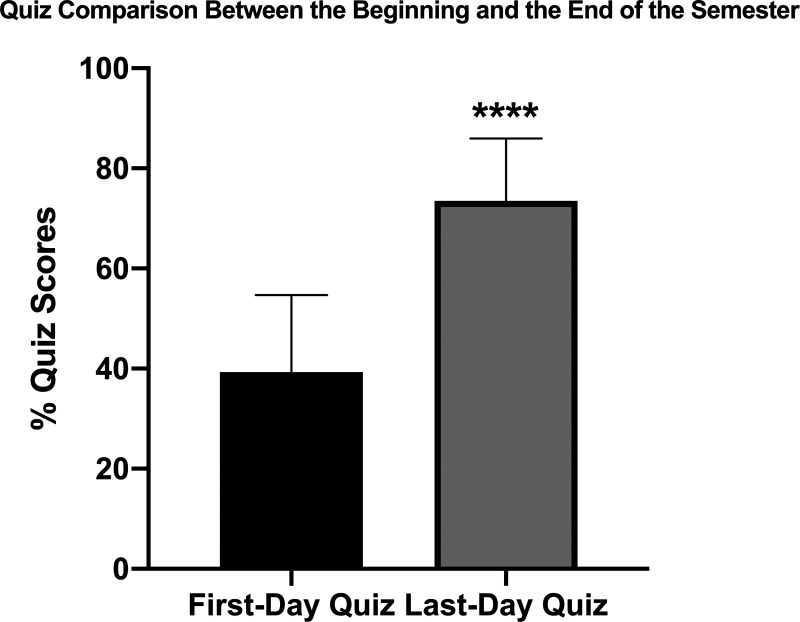

An unannounced 16-question quiz was given during the first day of the synchronous session. The same quiz was given again during the last day of classes without informing students before (Fig. 2). These quizzes helped assess knowledge acquisition over the entire semester. The questions were written at the comprehension and application levels with Bloom’s taxonomy (17).

Figure 2.

Comparison of quiz scores from the first-day and the last day of synchronous sessions. Values are means ± standard deviation; n = 33 students. ****P < 0.0001, paired Student’s t test.

Survey Instruments

A short survey was carried out on the first day of the semester to obtain information such as gender, race/ethnicity, and students’ undergraduate GPA to construct small groups for collaborative learning purposes. Thirty-three of the 35 students completed this survey (94.3%).

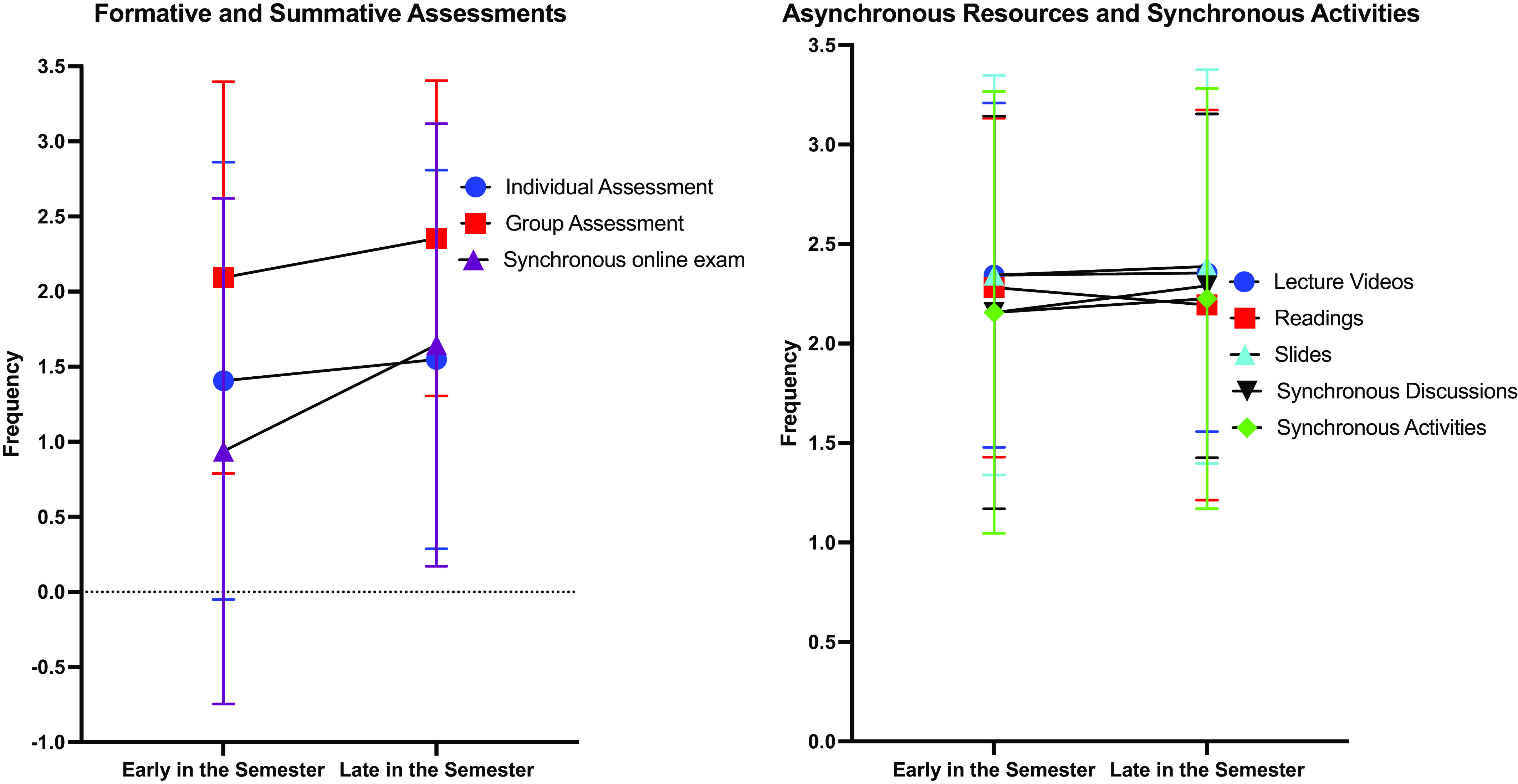

An additional survey was used to evaluate the sustainability of the virtual FT method used in the course. This survey was conducted twice: once during the 4th week and again during the 10th week of the 12-wk semester. It was completed by 97% of the students the first time and 93.9% of the students during the second round. The surveys were designed to assess students’ perception of adjustment to the virtual FT, confidence in completing the course, and endorsement of the virtual synchronous discussions. In addition, this survey captured students’ opinions of the formative and summative assessments. The surveys also obtained information on the students’ perceptions of the usefulness of the course resources such as lecture videos, readings, and lecture slides (Figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Comparison of survey scores from the beginning and the end of the semester. P < 0.001 between the early and late semester surveys for adjustment; P < 0.05 between the early and late semester surveys for confidence in passing the course.

Figure 4.

The student ratings from the early part of the semester were compared with the later part of the semester on formative and summative assessments as well as the resources that were provided in the asynchronous and synchronous settings. Strongly agree = 3, agree = 2, somewhat agree = 1, neither agree nor disagree = 0, somewhat disagree = −1, disagree = −2, strongly disagree = −3.

The survey instrument was created purposefully for this study by the expert in the delivery of this course. The survey questions were created to be meaningful to students who were taking this course, which would enable them to give valuable responses. Moreover, each question had an open response component, allowing the evaluator to check the alignment of each response by comparing the Likert scale answer to the narrative part. If these two parts were aligned (e.g., a positive Likert scale response and a positive narrative response), it was validated that the question was understood and interpreted in the way it was supposed to be.

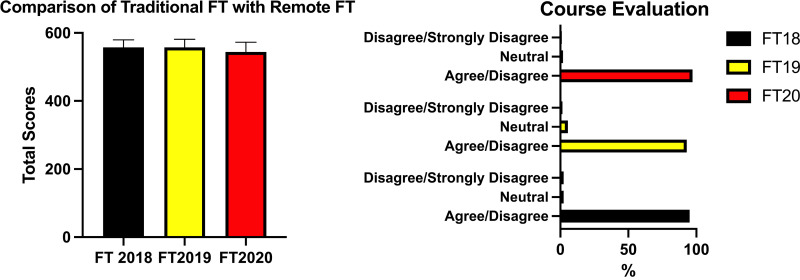

Students completed a compulsory standard course evaluation conducted by the university at the end of the semester. The course evaluation results were compared with the previous two semesters of similar course evaluations completed by the SRNA and NP students, when the course was taught in person. A summary of activities during the remote FT course is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chronological summary of activities during the semester

| Timeline | Purpose |

|---|---|

| First day | |

| A 5-question survey | To construct teams |

| A pop quiz | To measure baseline knowledge |

| Asynchronous activity prior to each synchronous meeting | |

| Lecture videos, lecture slides, and chapter reading | Preclass preparation |

| Virtual office hours | |

| Immediately prior to synchronous meeting | To clarify student questions on topics they needed help |

| Synchronous meeting (2 h; twice a week) | |

| Review of group assessment questions (group assessment conducted in the previous synchronous meeting) | To provide feedback and to engage students to participate in answering questions |

| Question and answer session (review of topics) | Clarification of content that the students had trouble understanding on their own |

| Individual quiz using PollEverywhere | To promote regular study habits and to encourage completion of preclass assignment |

| Group assessment using Breakout Rooms while using Zoom | Students interacted with peers in small groups and completed higher-order questions. |

| Synchronous online exams using LockDown Browser with monitor | Four exams were given ∼3 wk apart. |

| Survey to measure students’ perception of their adjustment, confidence, usefulness of course resources, and the formative and summative assessments | Conducted once during the 4th week of the semester, and the same survey was given during the 10th week of the semester. |

| Last day of synchronous meeting | Pop quiz (the same quiz that was given on the first day of virtual meeting) |

| Course evaluation | The university conducted a standard course evaluation after the semester ended. |

Comparison of the Face-to-Face vs. Virtual FT Courses

The reported virtual FT method was compared with the previous two semesters of face-to-face FT of the same course. The structure of the course was very similar except for three unavoidable variations in the virtual model:

The paper copy of the individual assessment was replaced by the PollEverywhere quiz.

The group assessment was carried out with the Breakout Rooms.

The computerized proctored exam was replaced by the synchronous virtual exams using Respondus LockDown Browser with the monitor feature.

Statistical Analysis

Survey instrument validation.

The validity of the survey questions yielded Cronbach’s α values at 0.95. Therefore, the tool was consistent across different periods. Furthermore, the high α value indicates that it is highly reliable.

Comparison of quiz scores.

Preliminary analysis of quiz scores, both pre- and postinstruction, and the differences in quiz scores indicated that the scores were Gaussian shaped in distribution. Furthermore, the pre- and postinstruction distributions had similar variances (as verified through the use of a folded F test), suggesting that the assumption of homogeneity of variances had been met, and therefore a paired t test was employed. Furthermore, the smallest possible effect size was 0.5. With G*Power, where the parameters included an α significance level of 0.05, a power of 0.80, and the effect size of 0.5, we determined that the sample size needed to reach this desired level of statistical power was 27, which was less than the sample size of 33 students.

Comparison of survey ratings.

Survey ratings, unlike the quiz scores, were ordinal and did not follow a Gaussian distribution. Therefore, the most appropriate test to use was the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test (18, 19). With the use of G*Power to determine a priori power, the parameters set were an effect size of 0.50, an α significance level of 0.05, and a power level of 0.80. The distributions were varied, as the parental distributions of the differences in each of the ratings were unknown. In doing so, the maximum required sample size was 28 students, which was less than the actual sample size of 33 students. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed in SAS version 9.4.

The comparison of survey ratings between the beginning and the end of the semester on student adjustment, confidence, formative and summative assessments, and asynchronous and synchronous activities was conducted by two-way ANOVA with GraphPad Prism version 9. The ranking of the resources was compared with the Wilcoxon rank sum during the early semester and the late semester and between the early and late semester surveys. A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the total scores for the semester between the FT courses taught in the face-to-face versus the virtual model.

RESULTS

A virtual FT method used during the COVID-19 pandemic and its effectiveness were examined in this study. Besides knowledge gain (Fig. 2), the study also measured student adjustment to the course, student confidence in completing the course, and their perception of discussions during synchronous meetings, formative and summative assessments, activities, and resources utilized in this virtual course (Figs. 3 and 4 and Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Student ratings on their adjustment and confidence in completing the course successfully and formative and summative assessments

| Questions | Early in the Semester |

Late in the Semester |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (n) | Percent | Frequency (n) | % | |

| Student adjustment and confidence | ||||

| How have you adjusted to the online teaching format? (on a scale of 1–4, very well to it has been very difficult) | ||||

| Very well (1) | 13 | 40.63% | 24 | 77.42% |

| Still adjusting (2) | 18 | 56.25% | 7 | 22.58% |

| It has been difficult (3) | 1 | 3.13% | 0 | 0.00% |

| How confident are you in completing this course in the online format? (on a scale of 1–5, very confident to not confident at all) | ||||

| Very confident (1) | 10 | 31.25% | 15 | 48.39% |

| Confident (2) | 18 | 56.25% | 14 | 45.61% |

| Neutral (3) | 4 | 12.50% | 2 | 6.45% |

| Formative and summative assessments | ||||

| I like the in-class quiz using PollEverywhere. (on a scale of 1–7, strongly agree to strongly disagree) | ||||

| Strongly agree (1) | 7 | 21.88% | 8 | 25.81% |

| Agree (2) | 13 | 40.63% | 10 | 32.26% |

| Somewhat agree (3) | 5 | 15.63% | 7 | 22.58% |

| Neither agree nor disagree (4) | 1 | 3.13% | 3 | 9.68% |

| Somewhat disagree (5) | 5 | 15.63% | 3 | 9.68% |

| Disagree (6) | 1 | 3.13% | 0 | 0.00% |

| I like the in-class group working using Breakout Rooms. (on a scale of 1–7, strongly agree to strongly disagree) | ||||

| Strongly agree (1) | 16 | 50.00% | 18 | 58.06% |

| Agree (2) | 11 | 34.38% | 10 | 32.26% |

| Somewhat agree (3) | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 3.23% |

| Neither agree nor disagree (4) | 3 | 9.38% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Somewhat disagree (5) | 1 | 3.13% | 2 | 6.45% |

| Disagree (6) | 1 | 3.13% | 0 | 0.00% |

| I like the online exam in the Respondus LockDown Browser with the monitor option. (on a scale of 1–7, strongly agree to strongly disagree) | ||||

| Strongly agree (1) | 5 | 15.63% | 7 | 22.58% |

| Agree (2) | 11 | 34.38% | 16 | 51.61% |

| Somewhat agree (3) | 5 | 15.63% | 5 | 16.13% |

| Neither agree nor disagree (4) | 4 | 12.50% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Somewhat disagree (5) | 2 | 6.25% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Disagree (6) | 5 | 15.63% | 2 | 6.45% |

| Strongly disagree (7) | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 3.23% |

Table 4.

Student ratings on in-class discussion and resources

| Early in the Semester |

Late in the Semester |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questions | Frequency (n) | % | Frequency (n) | % |

| I like lecture videos in preparing for my virtual in-class work. (on a scale of 1–7, strongly agree to strongly disagree) | ||||

| Strongly agree (1) | 16 | 50.00% | 16 | 51.61% |

| Agree (2) | 13 | 40.63% | 11 | 35.48% |

| Somewhat agree (3) | 2 | 6.25% | 3 | 9.68% |

| Neither agree nor disagree (4) | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 3.23% |

| Somewhat disagree (5) | 1 | 3.13% | 0 | 0.00% |

| I like readings provided by the instructor in preparing for my virtual in-class work (on a scale of 1–7, strongly agree to strongly disagree) | ||||

| Strongly agree (1) | 15 | 46.88% | 14 | 45.16% |

| Agree (2) | 13 | 40.63% | 12 | 38.71% |

| Somewhat agree (3) | 2 | 6.25% | 3 | 9.68% |

| Neither agree nor disagree (4) | 2 | 6.25% | 1 | 3.23% |

| Somewhat disagree (5) | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 3.23% |

| I like slides in preparing for my virtual in-class work. (on a scale of 1–7, strongly agree to strongly disagree) | ||||

| Strongly agree (1) | 20 | 62.50% | 17 | 54.84% |

| Agree (2) | 6 | 18.75% | 12 | 38.71% |

| Somewhat agree (3) | 3 | 9.38% | 1 | 3.23% |

| Neither agree nor disagree (4) | 3 | 9.38% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Disagree (6) | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 3.23% |

| I like the in-class discussion of topics. (on a scale of 1–7, strongly agree to strongly disagree) | ||||

| Strongly agree (1) | 12 | 37.50% | 14 | 45.16% |

| Agree (2) | 16 | 50.00% | 14 | 45.16% |

| Somewhat agree (3) | 3 | 9.38% | 2 | 6.45% |

| Somewhat disagree (5) | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 3.23% |

| Disagree (6) | 1 | 3.13% | 0 | 0.00% |

| I like the virtual synchronous in-class work. (on a scale of 1–7, strongly agree to strongly disagree) | ||||

| Strongly agree (1) | 13 | 40.63% | 15 | 48.39% |

| Agree (2) | 16 | 50.00% | 12 | 38.71% |

| Somewhat agree (3) | 1 | 3.13% | 2 | 6.45% |

| Somewhat disagree (5) | 1 | 3.13% | 2 | 6.45% |

| Disagree (6) | 1 | 3.13% | 0 | 0.00% |

Knowledge Gain

Knowledge gain in the remote flipped classroom was measured by a 16-question quiz given on the first and the last day of classes. The comparison of quiz grades between the first and last classes was analyzed with a paired Student’s t test. As shown in Fig. 2, students gained significant knowledge from the time they started the semester to the very end of the semester (P < 0.0001). The average quiz grade at the beginning of the semester was 39.31%, and the average quiz grade at the end of the semester was 73.48%.

Student Adjustment and Confidence

Student perception of the remote FT method at the beginning of the semester was compared to that at the end of the semester (Fig. 3 and Table 3). The comparison of the survey data related to student adjustment between the early and late parts of the semester was significantly different, where students perceived that adjustment was greater in the latter part of the semester (P < 0.001; Fig. 3).

Formative and Summative Assessments

Students completed an individual assessment during every synchronous session except on those days on which they were scheduled exams. The individual assessment was a 10-question quiz and was conducted with PollEverywhere. The survey assessed the effectiveness of the quizzes during the early part of the semester and the end of the semester. There were no significant differences in the responses between the early part of the semester and the latter part of the semester. Students were also asked if they liked the group assignment using Breakout Rooms at the beginning and the end of the semester. Finally, the students were asked whether they liked the online exams given synchronously with the Respondus LockDown Browser with the monitor using the same seven options. Students’ perceptions of synchronous exams shifted from early on in the course to the last few weeks (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

In-Class Discussion and Resources

Students were surveyed as to whether the lecture videos, readings, and lecture slides provided as resources in learning the course content were helpful. The endorsement of discussions during virtual synchronous meetings and the overall activities during the synchronous sessions was assessed in the same manner (Fig. 4 and Table 4).

Whether students preferred the resources in a particular sequence was analyzed. Based on the Wilcoxon rank sum, the ranking of the resources was not significantly different among the resources compared, regardless of whether it was in the early semester or the late semester or between the early and late semester surveys.

A Comparison of Student Performance and Course Evaluation between Virtual FT and Face-to-Face FT

A three-semester comparison of course evaluations completed by the students from the same course was used to examine whether the new mode of instruction significantly impacted student learning. The results suggest that students were satisfied with the virtual course in 2020 (n = 33, 75% response) just like they were in the previous two semesters that were taught in the face-to-face setting, FT2018 (n = 23, 88% response) and FT2019 (n = 21, 84%) semesters (Fig. 5). There was no significant difference in the total scores for the semester between the two modes of teaching or the course evaluations.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the total scores and course evaluation from the flipped teaching (FT) course that was taught virtually (2020) with those of the face-to-face FT in the previous semesters (FT2018 and FT2019).

DISCUSSION

In the wake of COVID-19, it became necessary to ensure the continuation of learning. The online modalities were more or less the only option given the circumstances of the lockdown mandate. The sudden transition to online teaching posed a challenge to both educators and students. This study focused on the transition of a face-to-face FT course to the virtual FT method.

Students were very engaged during the synchronous sessions and asked pertinent questions to indicate that they were adequately prepared. Their questions were typically over the difficult concepts such as countercurrent multiplier system, cardiac cycle, and cell-mediated and antibody-mediated immune mechanisms. Similar to recent reports (20–21), the present study suggests that the FT method that was implemented during the current pandemic positively impacted student success. Student adjustment to the remote teaching method increased significantly toward the end of the semester. It could be the FT method that the students were not familiar with when they first entered the program, but they could adjust well toward the end. One other reason could be that SRNAs were starting the program after being away from the classroom for some time since they are expected to attain specific clinical experiences to enter the program.

Students endorsed the course resources, which included the lecture videos, lecture slides, and the in-house textbook, as helpful, as indicated by the high percentages of “strongly agree,” “agree,” and “somewhat agree” ratings (Table 4). Although it was attempted, it was impossible to rank the resources that the students preferred sequentially since all resources appeared to be equally important based on their perceptions studied through the surveys. The majority of students reported how much they enjoyed having online resources (Table 5). Comments from open-ended questions included “The slides are beneficial to follow along in the lectures and take my notes” and “…book is amazing. It is a very nice read, in language that is easy to understand.” Students’ confidence in completing the course successfully also significantly increased as the semester ended, suggesting that the adjustment to the remote FT model was successful. The teaching method used in this course played a part in the students’ positive adjustment rate and confidence levels in this study. Many students endorsed liking the in-class discussion, collaborative group work, and instant feedback related to the course content: “This is very helpful. Being able to ask questions and be provided with additional instruction has gone a long way in helping me understand specific concepts.”

Table 5.

Samples of students’ comments

| Category | Survey in the Beginning of the Semester | Survey toward the End of the Semester |

|---|---|---|

| Confidence | “i am very confident that I will complete the course in the online format.” | “i have done better in this class than I expected to.” |

| Lecture videos | “The lecture videos are helpful in clearing up many details prior to class.” | “The lecture videos give great coverage of the subject.” |

| Readings | “This has been helpful as well. I like that our reading is precise and to the point.” | “It is nice to have the readings before class.” |

| Slides | “I am able to learn from them and they are good study tools for the exams.” | “The slides help in deciphering what might be more important.” |

| In-class discussion | “The in-class discussions help to reinforce the material and provide an opportunity to ask questions.” | “Always helpful and beneficial prior to taking quizzes.” |

| In-class group work | “Discussion with my peers clarify content I was struggling with.” | “Great way to learn from each other and explain topics.” |

| In-class quiz | “I think this is a quick and efficient way to quiz online.” | “I really enjoy being able to instantly go over the results.” |

| Exams | “For what we have to work with, I think it’s a fine alternative to in-class testing.” | “It is less stressful than going to a testing center.” |

A successful FT is built upon frequent formative assessments where students can study regularly instead of cramming the night before exams (22). Chick et al. (14) also reported success with the remote FT format, similar to our findings. One explanation for the success noted in this teaching method could be the nature of the course design built upon a combination of asynchronous and synchronous components. The exposure to content occurred for the first time in an asynchronous mode. Students having their own time to study the concepts before the synchronous session have the option of using resources to the best of their ability, such as rewatching the videos. The review of the topics during the synchronous virtual meeting the second time and the individual and the group assessments allowed frequent exposure to course content, thus enhancing learning.

Online testing is a major concern for many educators (23). Although the in-person method has been the traditional trusted approach, the methods used in this study, such as the LockDown Browser with the monitor feature and PollEverywhere could be alternate tools if strict guidelines are employed. Students became more comfortable handling the exam using the LockDown Browser with the monitor toward the end based on the survey report (90.32%).

Students reported that the individual assessment using PollEverywhere was beneficial because they could obtain immediate feedback in the form of a percentage of correct and incorrect answers. Questions with poor responses were discussed immediately. However, there were some technical challenges, since some students struggled to log in quickly and a few students required more time to complete the assessment compared with the rest of the class. Those who answered the questions had to wait patiently for the rest of the class to answer. One suggestion would be to move the individual assessment from the synchronous meeting to the asynchronous platform, such as the online quiz using the Respondus LockDown Browser combined with the monitor to complete this formative assessment before the synchronous meeting and receive feedback during the in-class session.

The student survey ratings for the group assessments were the highest (93.55%) among the assessments tested. Typically, the questions in the group assessment consisted of the higher-order questions as per Bloom’s taxonomy, and the strength of the group was essential in discussing the questions and arriving at the correct answer choices. Although the group assessments were one of the most-liked activities during the synchronous meeting, the budgeted time was insufficient to provide feedback during the same session. Hence, students were asked to submit their group answers on the day of the assessment, and the review took place in the following synchronous meeting. While reviewing group assignments, students were called randomly to answer questions, which allowed students to come prepared with answers to all the questions in the group assessment, once again encouraging student preparation.

The utilization of office hours by the students was a noteworthy observation during this study. Although students barely used the office hours in the face-to-face modality in the previous semesters, it was surprising to find at least two-thirds of the class attending virtual office hours regularly. Students admitted that they found online office hours convenient to attend and learned from other students’ questions. This finding suggests that virtual office hours should be further explored even if the face-to-face modality returns in the future.

Limitation of the Study

One limitation of this study was the class size. The small student population (n = 33) calls for testing this teaching strategy with a larger sample size.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the described virtual FT design employed a combination of synchronous and asynchronous portions. Assignments such as lecture videos, slides, and readings could be accessed by students remotely. Students were expected to review these assignments and come prepared for their virtual synchronous meetings, where discussion and clarification of the content preceded various computer-based formative assessments. Major exams were also conducted synchronously with computer-based technology. The survey data suggested that students endorsed the virtual FT method as a whole, and the approach resulted in the successful completion of the course by every student. Additionally, this study yielded essential findings on facilitating remote teaching, including hybrid instructional approaches, innovative instructional design, and the discovery of educational technology that facilitated a seamless transition.

Recommendations

Some recommendations based on this study would be:

Offer virtual office hours even when the in-class approach to teaching may return.

Immediate feedback could be yet another interactive activity where the students are randomly chosen to answer a particular question.

An individual synchronous quiz, as a formative assessment, could be shifted to an online platform and offer feedback during the synchronous period.

Also, in general, for those planning to flip their courses for the first time, the recommendations would be:

Provide all of the topics for the asynchronous portion of FT but be prepared to review complex concepts during the synchronous session. For example, while covering the content on platelets and coagulation, the basic details of the platelets and clotting factors need no additional explanation, but the clotting cascade itself is worth reviewing.

For the asynchronous preparation by the students, a guided prompt on the essential details, such as questions embedded into the lecture video at critical junctures, would be beneficial for the students to pause and process the information.

The asynchronous and synchronous activities must be designed to be intertwined; without the asynchronous preparation, synchronous content will be challenging to process for the students. The students should be encouraged to ask questions on the asynchronous content that was unclear before any additional formative assessments.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.G. conceived and designed research; C.G. performed experiments; C.G. and C.B.-W. analyzed data; C.G. interpreted results of experiments; C.G. prepared figures; C.G. and V.M. drafted manuscript; C.G. and V.M. edited and revised manuscript; C.G. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Elizabeth Hackmann and Sheyenne Daughrity for assistance in the revision of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rad FA, Otaki F, Baqain Z, Zary N, Al-Halabi M. Rapid transition to distance learning due to COVID-19: Perceptions of postgraduate dental learners and instructors. PLoS ONE 16: e0246584, 2021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yen TF. The performance of online teaching for flipped classroom based on COVID-19 aspect. Asian J Educ Soc Stud 8: 57–64, 2020. doi: 10.9734/ajess/2020/v8i330229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandhu P, de Wolf M, Johnson N, LaPorte D. The perceived effects of flipped teaching on knowledge acquisition background and literature review. Online Learning J 16: 6–21, 2020. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1092703.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson N, Veletsianos G, Seaman J. U.S. faculty and administrators’ experiences and approaches in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Online Learning J 24: 6–21, 2020. doi: 10.24059/olj.v24i2.2285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pather N, Blyth P, Chapman JA, Dayal MR, Flack NA, Fogg QA, Green RA, Hulme AK, Johnson IP, Meyer AJ, Morley JW, Shortland PJ, Štrkalj G, Štrkalj M, Valter K, Webb AL, Woodley SJ, Lazarus MD. Forced disruption of anatomy education in Australia and New Zealand: an acute response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Anat Sci Educ 13: 284–300, 2020. doi: 10.1002/ase.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalman R, MacIas Esparza M, Weston C. Student views of the online learning process during the covid-19 pandemic: a comparison of upper-level and entry-level undergraduate perspectives. J Chem Educ 97: 3353–3357, 2020. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armbruster P, Patel M, Johnson E, Weiss M. Active learning and student-centered pedagogy improve student attitudes and performance in introductory biology. CBE Life Sci Educ 8: 203–213, 2009. doi: 10.1187/cbe.09-03-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachhel R, Thaman RG. Effective use of pause procedure to enhance student engagement and learning. J Clin Diagn Res 8: 10–12, 2014. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8260.4691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman BE, Barker MK, Cooke JE. Best practices in active and student-centered learning in physiology classes. Adv Physiol Educ 42: 417–423, 2018. doi: 10.1152/advan.00064.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olaniyi NE. Threshold concepts: designing a format for the flipped classroom as an active learning technique for crossing the threshold. Res Pract Technol Enhanced Learn 15: 2, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s41039-020-0122-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altemueller L, Lindquist C. Flipped classroom instruction for inclusive learning. Br J Spec Educ 44: 341–358, 2017. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLean S, Attardi SM, Faden L, Goldszmidt M. Flipped classrooms and student learning: not just surface gains. Adv Physiol Educ 40: 47–55, 2016. doi: 10.1152/advan.00098.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newman G, Kim JH, Lee RJ, Brown BA, Huston S. The perceived effects of flipped teaching on knowledge acquisition background and literature review. J Eff Teach 16: 52–71, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, Propper BW, Hale DF, Alseidi AA, Vreeland TJ. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ 77: 729–732, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabharwal S, Ficke JR, LaPorte DM. How we do it: modified residency programming and adoption of remote didactic curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ 77: 1033–1036, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gopalan C, Fox DJ, Gaebelein C. Effect of an individual readiness assurance test on a team readiness assurance test in the team-based learning of physiology. Adv Physiol Educ 37: 61–64, 2013. doi: 10.1152/advan.00095.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krathwohl DR. A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: an overview. Theory Into Practice 41: 212–218, 2002. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ott RL, Longnecker MT. An Introduction to Statistical Methods and Data Analysis (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.López X, Valenzuela J, Nussbaum M, Tsai CC. Some recommendations for the reporting of quantitative studies. Comput Educ 91: 106–110, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh S, Arya A. A hybrid flipped-classroom approach for online teaching of biochemistry in developing countries during Covid-19 crisis. Biochem Mol Biol Educ 48: 502–503, 2020. doi: 10.1002/bmb.21418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalil R, Mansour AE, Fadda WA, Almisnid K, Aldamegh M, Al-Nafeesah A, Alkhalifah A, Al-Wutayd O. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ 20: 285, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herreid CF, Schiller NA. Case studies and the flipped classroom. J Coll Sci Teach 42: 62–67, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber SG, Helm C. COVID-19 and schooling: evaluation, assessment and accountability in times of crises—reacting quickly to explore key issues for policy, practice and research with the school barometer. Educ Assess Eval Account 2020: 1–34, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11092-020-09322-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]