Abstract

Background

Multiple severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreaks occurred at universities during Fall 2020, but little is known about risk factors for campus-associated infections or immunity provided by anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in young adults.

Methods

We conducted surveys and serology tests among students living in dormitories in September and November to examine infection risk factors and antibody presence. Using campus weekly reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test results, the relationship between survey responses, SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, and infections was assessed.

Results

Of 6136 students, 1197 completed the survey and 572 also completed serologic testing in September compared with 517 and 414 in November, respectively. Participation in fraternity or sorority events (adjusted risk ratio [aRR], 1.9 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.4–2.5]) and frequent alcohol consumption (aRR, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.2–2.2]) were associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Mask wearing during social events (aRR, 0.6 [95% CI, .6–1.0]) was associated with decreased risk. None of the 20 students with antibodies in September tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during the semester, while 27.8% of students who tested RT-PCR positive tested negative for antibodies in November.

Conclusions

Frequent drinking and attending social events were associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Antibody presence in September appeared to be protective from reinfection, but this finding was not statistically significant.

Keywords: COVID-19, risk factor, SARS-CoV-2, serology, university

Since the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), thousands of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases have been reported at university campuses in the United States, causing widespread academic and extracurricular disruptions [1–4]. Prevention and control of SARS-CoV-2 within institutions of higher education is challenging due to multiple factors including congregant housing (eg, on-campus dormitories), campus extracurricular activities, and students’ social behaviors [5]. Though prevention measures such as mask wearing and physical distancing are encouraged in campus settings, little is known about undergraduate students’ adherence to these prevention measures.

Serial testing for SARS-CoV-2 among a defined university student population provides an opportunity to learn more about factors associated with infection among young adults living in congregate settings. Additional systematic testing of university students, such as testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, could help further inform which students remained potentially susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 throughout the semester. In addition, the duration of protection afforded by SARS-CoV-2 antibodies is not well known, and while most data suggest that infected persons are rarely reinfected within 180 days of index infection [6], some data suggest that the initial mild infection, which is more common among young adults, might lead to a less robust immune response [7, 8].

In Wisconsin, COVID-19 case counts among adults aged 18–24 years increased sharply in mid-August, coinciding with students returning to university campuses [9]. At a large (>15 000 students) university in Wisconsin, an outbreak occurred immediately after students moved into dormitories, particularly in 2 of the largest dormitories. This led to cancellation of all in-person classes and events for 2 weeks and quarantine of students in on-campus housing and certain fraternity and sorority houses. Shortly before this rise in cases, we invited students living in dormitories at this university to participate in an epidemiologic survey and serological testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. This study aimed to identify risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection among dormitory residents and to describe the development and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

METHODS

Setting and Survey Data Collection

Students living in 19 dormitories at a major public university in Wisconsin were invited to participate in data collection at 2 time points during the Fall 2020 semester: (i) 1–4 September, shortly after students moved in (25–31 August); and (ii) 9–13 November. To mitigate SARS-CoV-2 transmission, the university encouraged students to remain home between the end of Thanksgiving recess (30 November) and the beginning of winter break (18 December).

At each time point, a survey was sent by email to dormitory residents. The surveys included questions regarding demographics, planned activities for the coming semester, personal COVID-19 prevention strategies (ie, mask wearing, social distancing), frequency of alcohol consumption and tobacco use, and any prior exposure to COVID-19.

Campus housing data pertaining to all students living in dormitories on 22 September 2020 (n = 6136) were provided by university housing staff and used to define the dormitory population for the survey analyses. Data included student name, birthdate, year in school (by credit hour), dormitory residence, and race and ethnicity. Data provided by the university may differ from the self-reported survey data used in the analysis.

Patient Consent Statement

This activity was reviewed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. Students’ written consent was obtained and information was anonymized to the extent possible.

Serologic Testing for SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies

All dormitory residents, regardless of survey participation, were invited to participate in free serologic testing for SARS-CoV-2 at 2 drop-in sites on campus during 1–4 September 2020 and 9–13 November 2020. Students presenting for serology testing were asked to complete the survey at presentation if they had not yet responded. Samples were tested with the Abbott Architect SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G (IgG) qualitative assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene (WSLH) [10]. Results from the chemiluminescent reaction were reported by the system as index values, and a threshold of 1.4 was set as the assay positivity cutoff.

SARS-CoV-2 Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction Testing and University Prevention Measures

The university offered free reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests to students, faculty, and staff during the summer and semester at testing locations on campus. Dormitory residents were required to participate in screening testing at move-in and every 2 weeks until mid-September when weekly testing was implemented. Supervised self-collected nasal swabs were used for all RT-PCR testing; early semester testing was carried out by a commercial laboratory, Exact Sciences [11], but then transitioned to the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory partnered with the WSLH on campus. Results of all tests conducted on dormitory residents as part of campus testing were shared by the university for use in this analysis. If a dormitory resident tested positive, they were no longer required to continue campus screening testing during the semester, consistent with CDC guidelines [12].

In addition to required testing and corresponding quarantine and isolation, the university made a variety of changes to limit SARS-CoV-2 transmission. They offered a combination of in personal and virtual classes, and all students living in the dormitories were required to use masks when outside their own rooms, maintain physical distance whenever possible, self-monitor for symptoms, and limit gatherings in accordance with local guidelines.

Statistical Analysis

To examine the outbreak on campus, student cases identified by campus testing were summed by week and shown in an epicurve. Cases were grouped by dormitory, with dormitories A and B compared to all other dormitories.

Student-level data from surveys, serology testing, serial campus RT-PCR testing, and campus housing data were linked; students who completed the survey but did not live in housing or participate in campus testing were excluded. Demographic data from campus housing, RT-PCR results, and testing frequency were used to compare survey respondents, and survey respondents with serological testing results, to all dormitory residents eligible for the investigation. For all other analyses, self-reported demographic data from the student survey were used.

For students completing either survey, responses were compared between students who were and were not infected during the semester using χ 2 tests or Fisher exact tests if sample size for 1 or more cells was <5. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used for continuous variables. September and November surveys were analyzed separately. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

For the September survey respondents only, the risk of infection associated with survey responses was quantified using risk ratios (RRs), calculated using binomial models with a log link. Age and year in school were modeled as ordinal variables. Frequent alcohol consumption was modeled as does not drink (reference), drinks less than weekly, and drinks weekly or more frequently. To better understand the relationship between social behaviors and SARS-CoV-2 infection risk, for 4 variables (alcohol consumption, participation in fraternity and sorority events, physical distancing, and mask wearing), we further adjusted the models. Variables were included in the model based on a priori assessments of confounding identified with directed acyclic graphs. If 2 variables of interest were highly correlated, the variable that minimized variance was included to avoid overfitting models.

Some students may have moved in or out of dormitories during the semester. To assess whether this affected our results, we limited the models to students who either tested positive by RT-PCR or received at least 8 RT-PCR tests (an indicator that students remained on campus throughout the semester).

Percentages of students with positive serology tests in September and November were calculated, and seropositive and seronegative students were compared by RT-PCR positivity. All students included in our serology testing analyses also completed the survey. When evaluating the relationship between positive campus RT-PCR result and serology result in September, students were excluded if they tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR during campus testing before serology specimen collection. For analysis comparing campus RT-PCR results and serology testing in November, students were excluded if their SARS-CoV-2–positive RT-PCR specimen was collected after the serology testing specimen. Median time between RT-PCR specimen collection and serology specimen collection in November was compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. All data analysis was completed using R studio version 1.2.1335.

RESULTS

Campus, Outbreak, and Survey Sample

Shortly after students moved into dormitories during 25–31 August 2020, cases on campus increased rapidly, especially among students living in dormitories A and B (Supplementary Figure 1). Cases began to fall at the end of September and transmission among dormitory residents stayed low until early November. Increases in cases in November were distributed relatively evenly across the 19 dormitories.

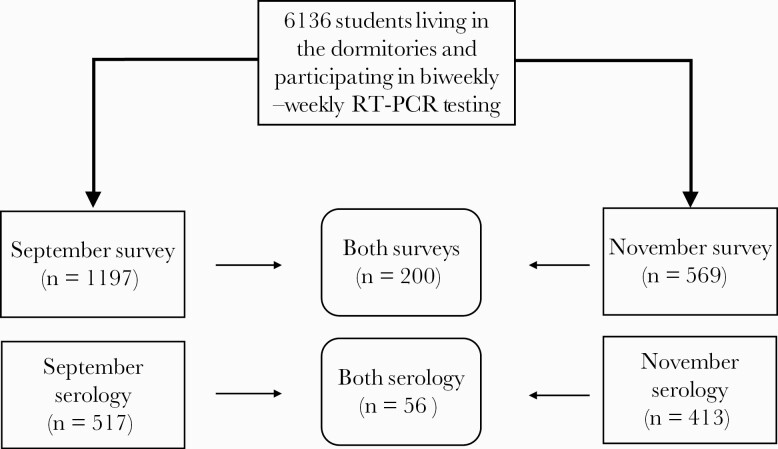

A total of 6136 dormitory residents were eligible for this investigation; 1024 (16.7%) tested positive by RT-PCR during 12 August 2020–12 November 2020. The survey was completed by 1197 dormitory residents (19.5%) in September and 569 (9.3%) in November, and 200 students completed the survey at both time points (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Total students living in the dormitories and tested weekly or biweekly for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and those who participated in epidemiologic survey and serology testing at the beginning (September 2020) and end (November 2020) of the semester at a major public university in Wisconsin. Surveys and serology testing were conducted during 1–4 September 2020, and again during 9–13 November 2020. All students living in the dormitories were invited to participate, and those on the housing list as of 22 September 2020 (n = 6136) were included in the analysis.

Based on campus housing data, students who completed the surveys were similar by age and number of RT-PCR tests received over the semester to the entire student population residing in dormitories (Table 1). More than three-quarters of students (78% in September, 75% in November) who completed surveys at either time point were White, compared to 71% of all dormitory residents. In November, 48% of students completing the survey lived in dormitory A or B. However, the percentages of students testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR among all housing students (16.7%) was similar to that of students who participated in the November survey (17.4%).

Table 1.

Demographics, Assigned Dormitories, and Results from Serial Campus Viral Testing from All University Students Living in Dormitories Compared to Students Who Completed Additional Epidemiologic Surveys or Participated in Serology Testing

| Characteristicsa |

Students, No. (%)b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Student Dormitory Residentsc (n = 6136) | Completed Survey in September (n = 1197) | Completed Survey in November (n = 569) | Serology Testing in September (n = 517) | Serology Testing in November (n = 413) | |

| Age, y, median (range) | 18.6 (16.7–38.7) | 18·6 (17.1–38.7) | 18.6 (17.7–24.2) | 18.6 (17.4–38.7) | 18.6 (17.7–24.2) |

| Credit hoursd | |||||

| Freshman equivalent | 3806 (62.0) | 686 (57.3) | 331 (58.2) | 311 (60.2) | 248 (60.0) |

| Sophomore equivalent | 1791 (29.2) | 410 (34.3) | 186 (32.7) | 178 (34.4) | 127 (30.8) |

| Junior equivalent | 345 (5.6) | 66 (5.5) | 22 (3.9) | 20 (3.9) | 14 (3.4) |

| Senior equivalent | 188 (3.1) | 33 (2.8) | 30 (5.3) | 6 (1.2) | 24 (5.8) |

| Graduate equivalent | 6 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 4351 (70.9) | 931 (77.8) | 429 (75.4) | 407 (787) | 303 (73.3) |

| Black | 194 (3.1) | 21 (1.8) | 12 (2.2) | 8 (1.5) | 9 (2.2) |

| Asian | 511 (8.3) | 74 (6.2) | 38 (6.7) | 27 (5.2) | 33 (8.0) |

| Other race | 760 (12.4) | 127 (10.6) | 62 (10.9) | 55 (10.6) | 49 (11.9) |

| Missing/declined | 320 (5.2) | 42 (3.5) | 26 (4.6) | 20 (3.9) | 19 (4.6) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 469 (7.6) | 73 (6.1) | 32 (5.6) | 34 (6.6) | 26 (6.3) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 5347 (87.1) | 933 (77.9) | 509 (89.5) | 463 (89.6) | 368 (89.1) |

| Missing | 320 (5.2) | 191 (16.0) | 28 (4.9) | 20 (3.9) | 19 (46) |

| Housing location | |||||

| Dorm A | 922 (15.0) | 145 (12.1) | 119 (20.9) | 64 (12.4) | 100 (24.2) |

| Dorm B | 1193 (19.4) | 207 (17.3) | 156 (27.4) | 84 (16.2) | 130 (31.5) |

| Dorm C | 152 (2.5) | 36 (3.0) | 10 (1.8) | 10 (1.9) | 5 (1.2) |

| Dorm E | 103 (1.7) | 18 (1.5) | 2 (0.4) | 5 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| Dorm F | 201 (3.3) | 43 (3.6) | 7 (1.2) | 11 (2.1) | 5 (1.2) |

| Dorm G | 477 (7.8) | 75 (6.3) | 48 (8.4) | 31 (6.0) | 39 (9.4) |

| Dorm H | 186 (3.0) | 51 (4.3) | 10 (1.8) | 20 (3.9) | 7 (1.7) |

| Dorm I | 26 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| Dorm J | 381 (6.2) | 77 (6.4) | 28 (4.9) | 27 (5.2) | 11 (2.7) |

| Dorm K | 318 (5.2) | 109 (9.1) | 34 (6.0) | 75 (14.5) | 19 (4.6) |

| Dorm L | 148 (2.4) | 38 (3.2) | 9 (1.6) | 9 (1.7) | 6 (1.5) |

| Dorm M | 53 (0.9) | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) |

| Dorm N | 528 (8.6) | 109 (9.1) | 36 (6.3) | 58 (11.2) | 23 (5.6) |

| Dorm O | 117 (1.9) | 21 (1.8) | 6 (1.1) | 4 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) |

| Dorm P | 164 (2.7) | 28 (2.3) | 17 (3.0) | 5 (1.0) | 13 (3.1) |

| Dorm Q | 368 (6.0) | 71 (5.9) | 20 (3.5) | 43 (8.3) | 13 (3.1) |

| Dorm R | 181 (2.9) | 34 (2.8) | 15 (2.6) | 16 (3.1) | 8 (1.9) |

| Dorm S | 187 (3.0) | 35 (2.9) | 16 (2.8) | 13 (2.5) | 6 (1.5) |

| Dorm T | 431 (7.0) | 95 (7.9) | 32 (5.6) | 38 (7.4) | 20 (4.8) |

| Ever positive by campus RT-PCR | 1024 (16.7) | 182 (15.2) | 99 (17.4) | 81 (15.7) | 76 (18.4) |

| No. of RT-PCR tests during the semester, median (range) | 9 (1–23) | 10 (1–20) | 10 (1–23) | 10 (1–15) | 10 (1–19) |

| Days from first RT-PCR test to last test, median (range) | 70 (0–95) | 70 (0–95) | 71 (0–92) | 70 (0–95) | 71 (0–92) |

Abbreviation: RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction.

aData provided by the university, which may differ from self-reported survey data.

bPercentages represent column percentages. Median and range used where indicated.

cStudents included all students who were living in the dormitories on 22 September 2020.

dCredit hours refer to credit hours listed in housing dataset. This is a different categorization than the self-reported survey question.

Among the 1197 students who completed the survey in September, 182 (15.2%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by on-campus RT-PCR during the semester (Table 2). Most students reported they were freshman (88.6%) and White (85.1%). More than half of students (56.5%) were from the state of Wisconsin (in-state students). Most had family members contributing to tuition (78.7%) and at least 1 parent with a college degree (80.5%). Most students (84.7%) had at least 1 roommate and approximately one-third (29.7%) were employed during the semester.

Table 2.

Comparison of Survey Responses by Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction Positivity During the Semester (7 August–12 November 2020) Among All Dormitory Resident Survey Respondents (September 2020)

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | Risk Ratio (95% CI)b |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 1197) | Any RT-PCR–Positive Test (n = 182) |

||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 477 (39.8) | 71 (39.0) | 1.0 (.7–1.3) |

| Female | 713 (59.6) | 111 (61.0) | REF |

| Other/refused | 7 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Age on 1 September, median (IQR) | 18.6 (18.3–18.9) | 18.6 (18.3–18.9) | 0.8 (.6–1.0)c |

| Year in schoold | 0.4 (.2–.7)c | ||

| Freshman | 1060 (88.6) | 163 (90.1) | |

| Sophomore | 86 (7.2) | 4 (2.2) | |

| Junior | 28 (2.3) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Senior | 22 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Graduate | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Raced | |||

| White | 1013 (85.1) | 172 (90.5) | REF |

| Black | 23 (1.9) | 4 (2.1) | 1.1 (.4–2.7) |

| Asian | 88 (7.4) | 8 (4.2) | 0.6 (.3–1.1) |

| Other | 66 (5.3) | 6 (3.3) | 0.6 (.3–1.2) |

| In-state studente | 675 (56.6) | 89 (48.9) | 0.7 (.6–1.0) |

| Tuitionf | |||

| Any family member support | 939 (78.7) | 153 (84.1) | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) |

| Any working supportg | 584 (49.0) | 74 (40.7) | 0.7 (.5–.9) |

| Any scholarship support | 615 (51.6) | 84 (46.2) | 0.8 (.6–1.0) |

| Any loan support | 390 (32.7) | 60 (33.0) | 1.0 (.8–1.3) |

| Parent has college degree | 963 (80.5) | 154 (84.6) | 1.3 (.9–2.0) |

| Live with roommate | 1014 (84.7) | 167 (91.8) | 2.0 (1.2–3.3) |

| Living in dormitory A or Bd | 346 (28.9) | 113 (62.1) | 4.0 (3.1–5.3) |

| Employed | 356 (29.7) | 43 (23.6) | 0.7 (.5–1.0) |

| Attendance of all or most classes in person | 51 (4.3) | 10 (5.5) | 1.3 (.7–2.3) |

| In-person activities | |||

| Work | 372 (31.1) | 44 (24.2) | 0.7 (.5–1.0) |

| Community work | 422 (35.3) | 63 (34.6) | 1.0 (.7–1.3) |

| Sport activities | 447 (37.3) | 73 (40.1) | 1.1 (.9–1.5) |

| Religious services | 120 (10.0) | 18 (9.9) | 1.0 (.6–1.5) |

| Theater/music | 78 (6.5) | 5 (2.7) | 0.4 (.2–1.0) |

| Fraternity/sorority events | 206 (17.2) | 72 (39.6) | 3.2 (2.4–4.1) |

| Smokes tobaccoh | 49 (4.1) | 14 (7.8) | 2.0 (1.2–3.1) |

| Vapes or uses electronic cigarettesi | 161 (13.5) | 40 (22.1) | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) |

| Frequency of alcohol consumption | |||

| Weekly or more | 370 (29.0) | 93 (51.1) | 2.8 (2.0–3.9) |

| Less than weekly | 389 (32.5) | 45 (24.7) | 1.2 (.8–1.8) |

| Never | 461 (38.5) | 44 (24.2) | REF |

| Typically consume 3 or more drinksj | 428 (58.2) | 94 (68.3) | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) |

| Mask wearing all or most of the time | |||

| In classk | 1045 (99.3) | 160 (99.5) | 1.1 (.2–6.6) |

| Between classesl | 880 (77.4) | 127 (73.4) | 0.8 (.6–1.1) |

| In dorm hallwaysm | 1027 (94.5) | 162 (94.7) | 1.1 (.6–2.0) |

| When shoppingn | 1182 (99.3) | 179 (98.9) | 0.6 (.2–2.0) |

| In dining hallo | 1062 (89.2) | 161 (88.5) | 0.9 (.6–1.4) |

| During extracurricular activitiesh | 811 (76.2) | 118 (70.2) | 0.7 (.6–1.0) |

| During social eventsi | 765 (71.8) | 110 (61.8) | 0.6 (.5–.8) |

| Physical distancing all/most of the timen | 923 (77.6) | 130 (71.8) | 0.7 (.6–1.0) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction.

aPercentages represent column percentages.

bRisk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 positivity by RT-PCR over the semester calculated using log-binomial models.

cRisk ratios are modeled ordinally.

dThese variables are based on self-report and distinct from the housing data variables used in Table 1.

eFour students replied “not applicable” or did not reply to this question.

fFour students replied “not applicable” or did not reply to this question. Tuition categories are not mutually exclusive.

gWorking support for tuition indicates that students responded that they were using their own wages or savings to pay tuition.

hTwelve students did not reply to this question.

iSix students did not reply to this question.

jFour hundred sixty-one students stated that they did not drink and were instructed to skip this question.

kOne hundred forty-five students replied “not applicable.”

lSixty students replied “not applicable.”

mOne hundred ten students replied “not applicable.”

nSeven students replied “not applicable.”

oOne hundred thirty-two students replied “not applicable.”

Only 51 students (4.3%) planned on attending class in person all or most of the time in the September survey. Approximately one-fifth (17.2%) of students intended to attend fraternity or sorority events during the semester. Relatively few students reported ever-smoking tobacco (4.1%) or ever using electronic cigarettes (13.5%) in September, but the proportion of ever-cigarette-smokers (7.8%) or electronic cigarette users (22.1%) was higher among students who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 than among those who did not (Table 2).

Almost every student surveyed (98.7%) owned a cloth mask and about half (49.4%) owned a surgical mask (Table 2). Students intended to wear their masks all or most of the time when required, such as in class (99.3%), while shopping (99.3%), and in the dining hall (89.2%). Predicted mask wearing all or most of the time between classes (77.4%), during extracurricular activities (76.2%), and at social events (71.8%) was lower than reported for other situations.

In November, 31 (5.4%) students stated that they had attended all or most of their classes in person over the semester (Supplementary Table 1). Student-reported mask wearing was high in in-person classes and while shopping in November and lower (43.0%) during social events (Supplementary Table 1). Because the September and November surveys were from different samples, this result was confirmed among students who completed both surveys, where 64% predicted mask wearing all or most of the time during social events in September but, in November, only 36.8% reported wearing their mask during social events. The same relationship was seen with social distancing all or most of the time: 71.9% of the students completing both surveys planned to social distance frequently in September, but only 59.2% reported social distancing all or most of the time in November.

Serologic Results

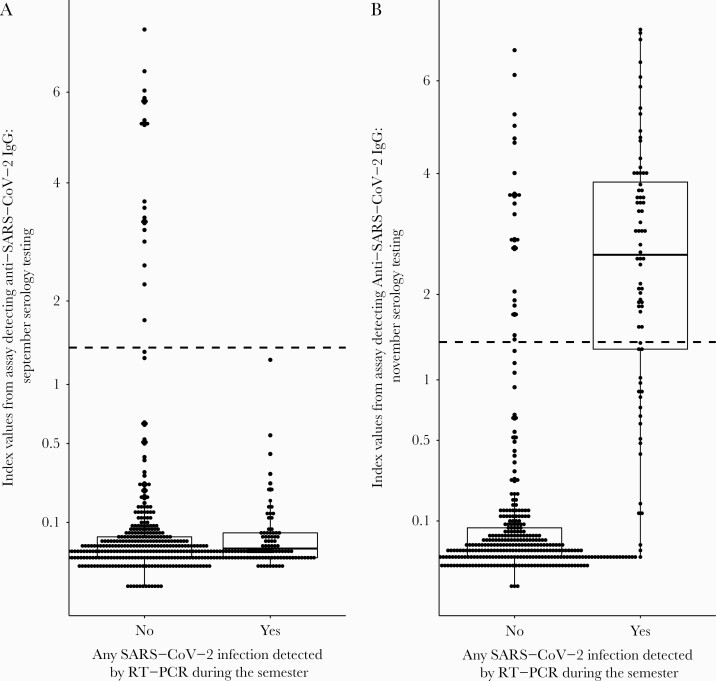

In September, 517 (43.2% of September survey participants) dormitory residents participated in serology testing and 21 (4.1%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 IgG. Among these students, before returning to campus, 15 (71.4%) students reported they had been exposed to someone infected with SARS-CoV-2 and 7 (33.3%) had tested positive, though all participated in campus RT-PCR testing (median: 5 tests [range, 2–11]). One student who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by campus-wide RT-PCR testing before the September serology collection was excluded from the analysis comparing RT-PCR results and September serology results (Table 3). Over the semester, no students who were seropositive in September and who participated in campus RT-PCR testing were positive for SARS-CoV-2, compared with 80 students (16.1%) who were seronegative in September (P = .06; (Table 3, Figure 2).

Table 3.

Individual Dormitory Residents’ Serology Status and Results From Serial Campus Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction Testing, September–November 2020

| Status | Serology Resultsa, September 2020 | Serology Resultsa, November 2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, No. (Column %)c | Serology Positive, No. (Column %)c | Serology Negative, No. (Column %)c | P Valued | Total, No.d | Serology Positive, No. (Row %) | Serology Negative, No. (Row %) | P Valuee | |

| Total | 517 | 21 | … | 413 | 77 (18.6) | … | ||

| Serial campus testing result (RT-PCR)b | ||||||||

| Total | 516 | 20 | 496 | .06 | 409 | 77 (18.8) | 332 (81.2) | <.0001 |

| Positive | 80 (15.5) | 0 (0.0) | 80 (16.1) | 72 | 52 (72.2) | 20 (27.8) | ||

| Always negative | 436 (84.5) | 20 (100.0) | 416 (83.9) | 337 | 25 (7.4) | 312 (92.6) | ||

| Days from RT-PCR specimen collection to serum collection, median (range) | … | … | … | 63 (8–92) | 62 (10–77) | 64.5 (8–92) | .17 |

Abbreviation: RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction.

aSerology results indicated presence of anti–severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) immunoglobulin G detected by the Abbot Architect assay

bRT-PCR testing completed every week or every 2 weeks for students living on campus throughout the semester.

cOne person excluded who had a positive RT-PCR test before their September serum collection.

dFour people excluded who had their positive RT-PCR test after their November serum collection.

eP values comparing the frequency of each characteristics by SARS-CoV-2 positivity were calculated using χ 2 tests or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. P values were calculated using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables.

Figure 2.

Index values indicating anti–severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels in students at a university in Wisconsin participating in serology testing in September and November 2020, by SARS-CoV-2 infection during the semester. A, Serology results from September 2020 testing. B, Serology results from November 2020 testing. One student who tested positive for reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) before the September serology collection was excluded, as were 4 students who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR after November testing. The dotted lines are at 1.4, which is the index value used by the manufacturer for a positivity cutoff.

In November, of the 413 students (72.2% of November survey participants) who participated in serology testing, 77 (18.6%) were seropositive and 7 (18.4%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR during the semester, although 4 students received their positive RT-PCR result after serum collection and were excluded from the analysis in Table 3 (Figure 1, Table 3). Of 72 students who tested positive by RT-PCR before serum collection, 20 (27.8%) were seronegative at the end of the semester (Table 3, Figure 2). The median time from collection of RT-PCR specimen to collection of serum specimen was similar among those who were seronegative (64.5 days) and those who were seropositive (62 days).

Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Infection From September Survey Participants

Older students (RR, 0.8 [95% confidence interval {CI}, .6–1.0] per year of increased age) and those in higher years in school (RR, 0.4 [95% CI, .2–.7] per year in school) had decreased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the semester (Table 2). Similarly, students who were employed (RR, 0.7 [95% CI, .5–1.0]) and in-state students (RR, 0.4 [95% CI, .2–.7]) had decreased risk of infection.

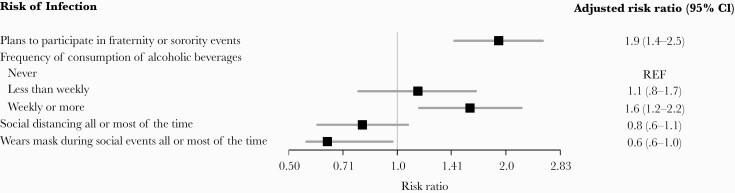

Students who lived in dormitory A or B had 4 times the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with those in other dormitories. Living with a roommate (RR, 2.0 [95% CI, 1.2–3.3]) was a risk factor for infection. Students who planned to participate in fraternity or sorority events had >3 times the risk of infection. After adjustment for confounders, the risk of infection associated with planned participation in fraternity or sorority events decreased, but remained significant (adjusted RR [aRR], 1.9 [95% CI, 1.4–2.5]) (Figure 3). Alcohol consumption weekly or more frequently was also a risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection (RR, 2.8 [95% CI, 2.0–3.9]) whereas students who drank less frequently were not at increased risk compared with students who did not drink (Table 2). After adjustment for confounders including planned participation in fraternity or sorority events, this relationship remained significant (aRR, 1.9 [95% CI, 1.4–2.5]).

Figure 3.

Risk factors for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection after adjustment for potential confounders among students living in dormitories at a university in Wisconsin, September 2020 (n = 1197). Infections were detected through weekly or biweekly reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing conducted on campus and required for all students living in the dormitories. Risk factors are derived from responses to the survey given in September, and all survey respondents from September are included in this analysis (n = 1197). The model predicting risk of infection associated with planned fraternity or sorority event participation was adjusted for living in dormitory A or B, having a roommate, year in school (ordinal), and working to contribute to tuition. The model predicting risk of infection associated with alcohol consumption was adjusted for the above variables in addition to participation in fraternity or sorority events. Models examining risk of infection associated with social distancing all or most of the time or mask wearing during social events all or most of the time were adjusted for year in school, in-state status, employment status, and working to contribute to tuition. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Students who predicted that they would physically distance all or most of the time had lower risk of infection over the semester (RR, 0.8 [95% CI, .6–1.0]). Similarly, those who planned to wear masks during social events had 0.6 times the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection (95% CI, .5–.8]). After adjustment for confounding, the magnitude of these RRs remained similar, though the relationship between planned social distancing and infection was no longer statistically significant (Figure 3).

When restricting the sample to 1017 students who received at least 8 RT-PCR tests throughout the semester or tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, model results remained largely similar (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our investigation identified risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection in university dormitory residents. We found that employed students and in-state students had lower risk of infection. Students whose parents had a college degree and whose family contributed to tuition had higher risk of infection, though this was not statistically significant. Over the pandemic, individuals with lower socioeconomic status have frequently been at higher risk of infection due to factors including crowded housing and workplace exposures [13–15]. We found that fewer students who were employed planned to participate in fraternity or sorority events compared with other students. The potential relationship between employment and lower risk of infection may reflect that students who support themselves participate less frequently in social events associated with infection.

The university environment presents challenges for control of SARS-CoV-2 due to congregate living and social networks that span on- and off-campus [16]. Our finding that planned participation in sorority and fraternity events was a predictor of SARS-CoV-2 infection has been previously reported [3] and emphasizes the connection between social events and on-campus SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks. This result suggests that frequent testing of dormitory residents might not be sufficient to prevent outbreaks, and increasing testing among students not living in dormitories, particularly those participating in fraternity or sorority activities, might help prevent future outbreaks [5, 17].

Additionally, we found that frequent alcohol consumption was a risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection independent of fraternity or sorority event attendance, suggesting that other social activities were related to transmission. Students who reported smoking or using electronic cigarettes were also more likely to be infected. Co-substance use, such as use of tobacco and alcohol, is more common at parties and bars among college students, possibly explaining this relationship [18, 19]. University campaigns to reduce high-risk drinking behavior may also mitigate SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Due to a statewide mask mandate during the semester and a university-enforced mask policy, mask wearing was compulsory during activities such as shopping and in-person classes. However, mask wearing was less common during extracurricular or social events. Importantly, students who planned to wear masks during social events had reduced risk of infection, and mask wearing is known to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission [20–22]. Taken together, these results point to the importance that social events play in on-campus SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Universities that find creative solutions to encourage prevention measures even during private social events may have more success in reducing SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

The results of our serosurvey indicate that most students were susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 in September. In November, 19% of dormitory residents had detectable antibodies, similar to the proportion of dormitory residents who tested RT-PCR positive for SARS-CoV-2 throughout the semester. Despite the large outbreak, most dormitory students were likely still susceptible to SARS-CoV-2. Testing, quarantine, and other prevention methods will be critical for limiting SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks in the future.

Among the 20 students who were SARS-CoV-2 seropositive on arrival to campus and participated in SARS-CoV-2 campus-wide testing, none tested positive through weekly campus RT-PCR testing. This result suggests that IgG may be protective, though it is limited by small sample size and does not reach a level of statistical significance. However, due to the frequent RT-PCR testing, SARS-CoV-2 infection would have likely been detected if it occurred during the semester, whether symptomatic or asymptomatic. This supports existing evidence that previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, indicated here by antibody presence, is protective against reinfection for at least 3–6 months [12, 23].

Limited data are available about SARS-CoV-2 antibody duration in young adults. In certain studies, SARS-CoV-2 antibodies have been shown to wane rapidly within 3–4 months, while in others, antibody levels have persisted over 3 months [8, 24, 25]. In our analysis, almost one-third of students with a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test during the semester did not have detectable IgG at the end of the semester; this is a higher proportion than has been shown in previous reports [26]. The median number of days between RT-PCR specimen collection and serum specimen collection was 62.5, suggesting that students who tested positive either never mounted antibody responses or, alternatively, their antibody levels waned rapidly. Several students had positive RT-PCR results and elevated IgG index values that were below the threshold for positivity; this might indicate protection from infection but not be considered positive with the current threshold of our assay. However, further investigation is needed to clarify the durability of antibody protection in young persons and whether other mechanisms of protection, such as cellular immunity, might also be providing immunity [27].

While our analysis provides new insight into risk factors for infection to inform university policies to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2, there are several limitations. Less than 20% of students living in dormitories participated in our investigation, which could bias our results. However, the September sample was prospective and avoided over-participation from infected students. Additionally, students might have moved on or off campus throughout the semester. While we did not have longitudinal dormitory rosters, we performed a sensitivity analysis, only among students receiving at least 8 negative RT-PCR tests or a positive RT-PCR test, indicating presence on campus through the outbreak. This restriction did not impact our findings. In our SARS-CoV-2 serology analysis, we did not measure neutralizing antibodies or other components of the immune response. More detailed serologic testing could help inform the relationship between seronegative results postinfection and SARS-CoV-2 reinfection.

In conclusion, we identified certain social behaviors, such as frequent alcohol drinking and participating in fraternity or sorority events, to be risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection among students living in dormitories, pointing to the importance of social activities in on-campus outbreaks. We also found that students who planned to adhere to prevention measures were at reduced risk of infection; therefore, improving overall student adherence to these measures on campus might help reduce transmission. Our finding that no student with SARS-CoV-2 antibodies at the beginning of the semester reported a positive RT-PCR test during the semester adds to existing evidence that persons with detectable IgG are protected from infection, although the numbers of antibody positive students in this study were small. The finding that numerous students did not have detectable IgG only a few months after SARS-CoV-2 infection warrants future investigation to understand the adaptive immune response in young adults.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. Kris Bisgard (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]), Alana Sterkel (Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene).

Ethics committee approval. This activity was consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy, see, eg, 45 Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.) part 46; 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 United States Code (U.S.C.) §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552(a); and 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Financial support. This work was part of a public health investigation and was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Lewis M, Sanchez R, Auerbach S, et al. COVID-19 outbreak among college students after a spring break trip to Mexico—Austin, Texas, March 26–April 5, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:830–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leidner AJ, Barry V, Bowen VB, et al. Opening of large institutions of higher education and county-level COVID-19 incidence—United States, July 6–September 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:14–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vang KE, Krow-Lucal ER, James AE, et al. Participation in fraternity and sorority activities and the spread of COVID-19 among residential university communities—Arkansas, August 21–September 5, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:20–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson E, Donovan CV, Campbell M, et al. Multiple COVID-19 clusters on a university campus—North Carolina, August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1416–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walke HT, Honein MA, Redfield RR. Preventing and responding to COVID-19 on college campuses. JAMA 2020; 324:1727–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lumley SF, O’Donnell D, Stoesser NE, et al. ; Oxford University Hospitals Staff Testing Group. Antibody status and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:533–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Self WH, Tenforde MW, Stubblefield WB, et al. Decline in SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after mild infection among frontline health care personnel in a multistate hospital network—12 states, April–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1762–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seow J, Graham C, Merrick B, et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat Microbiol 2020; 5:1598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pray IW, Kocharian A, Mason J, et al. Trends in outbreak-associated cases of COVID-19—Wisconsin, March–November 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:114–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA in vitro diagnostics EUAs.https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/eua-authorized-serology-test-performance. Accessed 24 January 2021.

- 11.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA in vitro diagnostics EUAs.https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/in-vitro-diagnostics-euas-molecular-diagnostic-tests-sars-cov-2#individual-molecular. Accessed 24 January 2021.

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare workers.2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html. Accessed 24 January 2021.

- 13.Ahmad K, Erqou S, Shah N, et al. Association of poor housing conditions with COVID-19 incidence and mortality across US counties. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0241327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muñoz-Price LS, Nattinger AB, Rivera F, et al. Racial disparities in incidence and outcomes among patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e2021892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drefahl S, Wallace M, Mussino E, et al. A population-based cohort study of socio-demographic risk factors for COVID-19 deaths in Sweden. Nat Commun 2020; 11:5097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community, work, and school.2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/colleges-universities/considerations.html. Accessed 31 January 2021.

- 17.Paltiel AD, Zheng A, Walensky RP. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 screening strategies to permit the safe reopening of college campuses in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e2016818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phua J. The influence of peer norms and popularity on smoking and drinking behavior among college fraternity members: a social network analysis. Soc Influ 2011; 6:153–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nichter M, Nichter M, Carkoglu A, Lloyd-Richardson E; Tobacco Etiology Research Network. Smoking and drinking among college students: “it’s a package deal.” Drug Alcohol Depend 2010; 106:16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung NHL, Chu DKW, Shiu EYC, et al. Respiratory virus shedding in exhaled breath and efficacy of face masks. Nat Med 2020; 26:676–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsley WG, Blachere FM, Law BF, et al. Efficacy of face masks, neck gaiters and face shields for reducing the expulsion of simulated cough-generated aerosols. Aerosol Sci Technol 2021; 55:449–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueki H, Furusawa Y, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, et al. Effectiveness of face masks in preventing airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. mSphere 2020; 5:e00637-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanrath AT, Payne BAI, Duncan CJA. Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with protection against symptomatic reinfection. J Infect 2021; 82:e29–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isho B, Abe KT, Zuo M, et al. Persistence of serum and saliva antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike antigens in COVID-19 patients. Sci Immunol 2020; 5:eabe5511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iyer AS, Jones FK, Nodoushani A, et al. Persistence and decay of human antibody responses to the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in COVID-19 patients. Sci Immunol 2020; 5:eabe0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen LR, Samira S, Vuong N. Lack of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in a large cohort of previously infected persons [manuscript published online ahead of print 4 November 2020]. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekine T, Perez-Potti A, Rivera-Ballesteros O, et al. Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Cell 2020;183:158–68.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.