Abstract

The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination on viral characteristics of breakthrough infections is unknown. In this prospective cohort study, incidence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection decreased following vaccination. Although asymptomatic positive tests were observed following vaccination, the higher cycle thresholds, repeat negative tests, and inability to culture virus raise questions about their clinical significance.

Keywords: COVID, SARS-CoV-2, pandemic, incidence, vaccine

Vaccination substantially reduces coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–related symptomatic infection, severe disease, hospitalization, and death in both clinical trial [1–3] and real-world settings [4, 5]. Less is known about the effect of vaccination on asymptomatic infection. Early reports from observational studies suggest reduced rates of asymptomatic infection among vaccinated individuals [6, 7], but studies so far have provided limited information on virologic characteristics of breakthrough infections. As asymptomatic infections have been important drivers of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission prior to vaccination [8, 9], improved understanding of postvaccination asymptomatic infections, including viral load and duration of shedding, is a public health priority.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a prospective cohort study of healthcare workers before, during, and after COVID-19 vaccination in a large healthcare system (Mass General Brigham [MGB]) in Boston, Massachusetts, from 30 December 2020 through 2 April 2021. Employees were eligible for participation if they were eligible for vaccination through MGB’s vaccination program, were planning to or had recently received the first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine through MGB, and were able to drop off weekly self-swab testing kits. We recruited healthcare workers through email announcements and posted advertisements in English and Spanish.

Study Procedures and Data Collection

Participants completed weekly self-administered anterior nasal swabs and online symptom surveys. Participants who developed symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 accessed additional testing through Occupational Health protocols. Weekly testing continued from study enrollment through 8 weeks after the first vaccine dose; if a participant enrolled >4 weeks after the first vaccine dose, testing continued for 4 weeks. Those who tested positive underwent independent symptom evaluation through Occupational Health. Nasal swabs underwent real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing at the Broad Institute of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts), with cycle thresholds reported for positive tests (3 cycles is about 1 log difference in viral load) [10]. Testing through Occupational Health was completed at either the Broad Institute or a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–approved, hospital-affiliated laboratory. Study investigators had access to all participants’ SARS-CoV-2 test results in the MGB system and Occupational Health symptom assessments during the study period.

Virologic Characteristics Substudy

On 29 January 2021, we initiated a substudy to elucidate virologic characteristics of postvaccination infection. For study participants who tested positive after their first vaccine dose, we conducted home visits approximately every other day for up to 14 days to collect self-administered nasal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing, viral culture, and sequencing (see Supplementary Materials).

Statistical Analysis

Our primary outcome was infection incidence rates in the prevaccination, partially vaccinated, and fully vaccinated intervals. Our primary exposure was vaccination period, classified based on time since the first and second vaccine doses, as prevaccination, partially vaccinated, and fully vaccinated intervals. For the 2-dose messenger RNA vaccine regimens, we defined the prevaccination period as observation time up to 5 days after the first vaccine dose, the partially vaccinated period as 6 days after the first vaccine dose through 13 days after the second vaccine dose, and the fully vaccinated period as 14 days after the second vaccine dose until the end of the follow-up interval. We completed sensitivity analyses varying the delineation between the prevaccination and partial vaccination periods.

Participants contributed observation time between their first and last swab. Observation time for participants who tested positive ended at the time of the positive test. We calculated incidence rates as the number of positive swabs divided by the total observation time in each vaccination period and estimated incidence rate ratios comparing the time periods using generalized estimating equations with a log link, Poisson distribution, and robust standard errors. Among those who tested positive, we compared cycle thresholds by symptom and vaccination status, compared the ratio of symptomatic to asymptomatic infections by vaccination status, and summarized the duration of culture positivity. Analyses were completed using Stata version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) and R (www.r-project.org) software. The study was approved by the MGB Human Subjects Review Committee.

RESULTS

In total, 2247 healthcare workers were included in the analytic cohort (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). More women enrolled (n = 1760 [78%]); the median age was 37 years (interquartile range [IQR], 30–50); the most common healthcare role was physician/nurse practitioner/physician assistant (n = 873 [39%]); and 84% (n = 1879) identified as white or Caucasian. Nearly half (n = 1015 [47%]) cared for COVID-19 patients during the study, and nearly all participants (n = 2243 [>99%]) were fully vaccinated by the end of the study period. The most common vaccine manufacturers were Moderna (n = 1428 [64%]) and Pfizer-BioNTech (n = 814 [36%]).

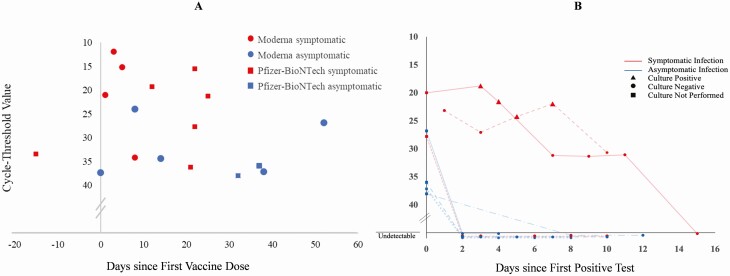

Participants completed 13 359 swabs (median, 6 swabs per participant [IQR, 3–8]) over 85 109 person-days (median, 42 person-days [IQR, 26–50]). Nineteen (0.8%) participants had a positive test during the study period (Figure 1A), an incidence rate of 81.5 infections per 1000 person-years (95% confidence interval [CI], 49.1–127.3). No participants were hospitalized for COVID-19–associated illness. Of these 19 infections, 6 (31.6%) occurred in the prevaccination period (median, 1.5 days after dose 1), 10 (52.6%) occurred during the partial vaccination period (median, 21.5 days after dose 1), and 3 (15.8%) occurred after full vaccination (median, 52 days after dose 1). Incidence was lower among those who were fully vaccinated (34.6 per 1000 person-years [95% CI, 7.1–101.1]; rate ratio, 0.052 [95% CI, .013–.21]; P < .001) and those who were partially vaccinated (72.8 per 1000 person-years [95% CI, 34.9–133.9]; rate ratio, 0.11 [95% CI, .040–.30]; P < .001), compared to those who were unvaccinated (666.3 per 1000 person-years [95% CI, 244.5–1450.3]) at the time of the positive test (Supplementary Table 3). Results were similar after varying the vaccine interval period definitions (Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 1.

Cycle thresholds in relation to time since first vaccine dose (A), duration of detectable severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and culture positivity (B) among participants with detectable SARS-CoV-2. In (B), each line represents a single participant over time. Samples collected after day 0 were tested with a quantitative viral load assay.

Cycle thresholds were available for 17 (89%) of the positive tests and were lower (indicating higher viral loads) in participants with symptomatic compared with asymptomatic infections (21.1 [IQR, 15.6–33.5] vs 36.0 [IQR, 26.8–37.4]; P = .01). Differences in cycle thresholds among those who tested positive before vaccination vs those with partial or full vaccination were not statistically significant (21.0 [IQR, 15.2–33.5] vs 31.0 [IQR, 21.3–36.2] or 31.4 [IQR, 26.8–36.0], respectively; P = .50). Five of 6 (83%) infections that occurred before vaccination were symptomatic, compared with 6 of 10 (60%) infections that occurred in the partial vaccination period and 1 of 3 (33%) infections that occurred after full vaccination (P = .39).

Seven participants with positive tests after the virologic substudy began (4 asymptomatic, 3 symptomatic individuals; all in the partially or fully vaccinated periods) underwent additional characterization (Supplementary Table 5). All 4 individuals with asymptomatic infections had undetectable viral loads a median of 2 days (IQR, 2–2) after their positive test and none had culturable virus at that time. One individual with symptomatic infection had an undetectable nasal swab viral load and negative culture 2 days after their positive test. Two of the 3 participants with symptomatic infections had a detectable viral load for 10 and 11 days, and culturable virus for 4 and 7 days, respectively (Figure 1B). Both were sequenced and determined to be the B.1.1.7 (Alpha) variant.

DISCUSSION

By coordinating a systematic testing infrastructure amid a large health system’s rapid COVID-19 vaccination rollout, we found that SARS-CoV-2 infection incidence decreased in a stepwise fashion following vaccination. We did identify asymptomatic infections in the partial and fully vaccinated periods; however, all asymptomatic individuals who underwent serial retesting had negative repeat PCR tests within 2 days and none had culturable live virus. This suggests a shorter duration of viral shedding in these asymptomatic individuals than has been previously reported for prevaccination symptomatic infections [11, 12]. These findings raise important questions about whether postvaccination asymptomatic, high-cycle-threshold positive tests represent transient infections or, alternatively, false-positive tests.

By contrast, 2 of 3 participants with symptomatic infection in the partial or fully vaccinated periods had prolonged viral shedding and culturable virus up to 7 days after the initial positive test. Future work to elucidate viral and immunologic contributors to postvaccination infection will be critical to understanding why some individuals are not protected from infection.

Strengths of this study are the prospective design, systematic weekly sampling regardless of symptoms, and in-depth virologic characterization among a subset of participants who tested positive. This study also has limitations. First, participants completed nasal swabs weekly, which may have been longer than the interval in which an asymptomatic participant could be infected and have stopped shedding, thereby underestimating asymptomatic infection incidence. Second, we were unable to enroll an unvaccinated control group in the healthcare setting, limiting our ability to definitively separate incidence trends in our study from regional trends during the study period. However, the incidence rate in our study cohort continued to decline while local test positivity began to increase (Supplementary Figure 1), suggesting that incidence rates in our cohort are not simply a mirror of community trends. Last, our cohort is comprised of healthcare workers who are predominantly young, female, and of white non-Hispanic race/ethnicity, and may not reflect the general population, including older adults and those who are immunosuppressed.

In summary, COVID-19 incidence decreased from pre- to postvaccination. Although positive tests were observed in asymptomatic individuals following vaccination, higher cycle thresholds, subsequent negative repeat PCR testing, and inability to culture the virus in those cases call into question the clinical significance of these asymptomatic infections.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Giancarlo Buonomo, Grace Chamberlin, Alan Chen, Brandon Duffy, Gina Endres, Eliana Epstein, Harmanjot Kaur, Hope Koene, Taryn Lipiner, Dan Morash, Jaclyn Pagliaro, Nicholas Rahim, Dakarai Saunders, Gary Smith, Tatiana Sultzbach, and Ryan Vyas for their effort in collecting samples, making this study possible.

Disclaimer. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of Mass General Brigham, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), or any of the other funders.

Financial support. This work was supported by Mass General Brigham and the Massachusetts General Hospital (COVID Clinical Trials Pilot Grant, Executive Committee on Research, and Department of Medicine) and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, with philanthropic support from F/Prime Capital. The BSL3 portion of this work was supported by the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness and the Harvard Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (grant number P30AI060354). The viral genome sequencing portion of this work was supported by the Broad Institute Viral Genomics Group and funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (BAA 75D30120C09605). J. Z. L. is supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number P30AI060354) and a gift from Mark and Lisa Schwartz. C. M. N. is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant number K23HL154863).

Potential conflicts of interest. C. M. N. receives consulting fees from Axle Informatics for safety monitoring related to COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials. D. M. F. receives consulting fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals for serving on data safety and monitoring boards. J. E. L. received consulting fees from Sherlock Biosciences. B. C. H. has received grant support from Analysis Group, Celgene (Bristol-Myers Squibb), Verily Life Sciences, Novartis, Merck Serono, and Genzyme. A. E. W. received personal fees from COVAXX outside the submitted work. L. R. B. is involved in HIV and COVID vaccine clinical trials conducted in collaboration with the NIH, HIV Vaccine Trials Network, COVID Vaccine Prevention Network, International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, Crucell/Janssen, Moderna, Military HIV Research Program, Gates Foundation, and Ragon Institute. L. R. B. reports grants from Ragon Institute, NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Gates Foundation, and Wellcome Trust, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. ; COVE Study Group. . Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:403–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. ; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group. . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:2603–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, et al. Safety and efficacy of single-dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:2187–2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:1412–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Keehner J, Horton LE, Pfeffer MA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in health care workers in California. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:1774–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, et al. Interim estimates of vaccine effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among health care personnel, first responders, and other essential and frontline workers—eight U.S. locations, December 2020-March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:495–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tang L, Hijano DR, Gaur AH, et al. Asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections after BNT162b2 vaccination in a routinely screened workforce. JAMA 2021; 325:2500–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gandhi M, Yokoe DS, Havlir DV. Asymptomatic transmission, the Achilles’ heel of current strategies to control Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:2158–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johansson MA, Quandelacy TM, Kada S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission from people without COVID-19 symptoms. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e2035057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) summary: CRSP SARS-CoV-2 real-time reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR diagnostic assay clinical research sequencing platform (CRSP), LLC at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/139858/download. Accessed 21 July 2021.

- 11. Kim MC, Cui C, Shin KR, et al. Duration of culturable SARS-CoV-2 in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:671–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Kampen JJA, van de Vijver DAMC, Fraaij PLA, et al. Duration and key determinants of infectious virus shedding in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). Nat Commun 2021; 12:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.