Abstract

Objective

There is increasing evidence that amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease impacting large-scale brain networks. However, it is still unclear which structural networks are associated with the disease and whether the network connectomics are associated with disease progression. This study was aimed to characterize the network abnormalities in ALS and to identify the network-based biomarkers that predict the ALS baseline progression rate.

Methods

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed on 73 patients with sporadic ALS and 100 healthy participants to acquire diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance images and construct white matter (WM) networks using tractography methods. The global and regional network properties were compared between ALS and healthy subjects. The single-subject WM network matrices of patients were used to predict the ALS baseline progression rate using machine learning algorithms.

Results

Compared with the healthy participants, the patients with ALS showed significantly decreased clustering coefficient Cp (P = 0.0034, t = 2.98), normalized clustering coefficient γ (P = 0.039, t = 2.08), and small‐worldness σ (P = 0.038, t = 2.10) at the global network level. The patients also showed decreased regional centralities in motor and non-motor systems including the frontal, temporal and subcortical regions. Using the single-subject structural connection matrix, our classification model could distinguish patients with fast versus slow progression rate with an average accuracy of 85%.

Conclusion

Disruption of the WM structural networks in ALS is indicated by weaker small-worldness and disturbances in regions outside of the motor systems, extending the classical pathophysiological understanding of ALS as a motor disorder. The individual WM structural network matrices of ALS patients are potential neuroimaging biomarkers for the baseline disease progression in clinical practice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40035-021-00255-0.

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, White matter, DTI, Network, Connectomics, Machine learning, Psychoradiology

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is an intractable progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized classically by neurodegeneration and loss of upper motor neurons of the corticospinal tract and lower motor neurons of the brainstem and spinal cord anterior horns [1]. While symptoms such as muscular weakness, spasticity and hyperreflexia may initially be manageable, the progressive loss of respiratory muscle innervation can lead to respiratory failure, typically within 2–4 years of symptom onset [2]. There is increasing evidence that ALS also affects multiple neural systems beyond the motor cortex and corticospinal tract [3] and there is an urgent need to identify reliable biomarkers for ALS progression in clinical practice and pharmacological trials [4].

Typically, decreased fractional anisotropy (FA) within focal brain regions including motor, frontal and prefrontal areas are found in white matter (WM) studies in ALS using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) tractography [5] and tract‐based spatial statistics [6–8]. DTI metrics are sensitive markers for WM change [9], and have been recommended for ALS diagnosis [9] and assessment of disease progression [10, 11]. However, the direct correlations between focal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) metrics and neuropsychological measures are questionable, because the motor, cognitive and behavioral functions are mediated by multisynaptic brain networks [12]. Therefore, the notion of selective anatomic vulnerability [13] is being supplemented and to some extent replaced by the syndrome-specific network vulnerability notion [14], which is supported by concepts such as network-wise degeneration [15], circuit-specific vulnerability [16] and disease progression along structural connectivity patterns [17]. DTI studies based on graph theory offer a valuable tool to analyze the topological organization of brain networks and inter-regional connections [18], which may be indicators of ALS progression [19]. In the ‘connectomics’ analysis, cortical and subcortical brain regions are parcellated into nodes, and the WM metrics of tracks between them taken as the edges of a mathematical graph. Such studies show that the brain networks have a “small-world” organization [18], intermediate between random networks, whose shorter overall path length is associated with a low level of local clustering, and regular networks or lattices, whose high level of clustering is accompanied by a long path length [18]. The small-world network architecture reconciles relatively independent functioning (i.e. segregation) with fast information transfer (i.e. integration) [20]. Application of this powerful approach to the brain structural and functional connectome in ALS has, however, yielded inconsistent results [19, 21–23].

Incorporating the interaction information across the whole brain, the single-subject network approach has value in characterizing objective brain features to distinguish patients from healthy individuals [24] as well as for predicting clinical outcomes after drug treatment [25]. Several clinical prognostic factors have been identified for ALS, including age, site of onset, functional and respiratory status, cognitive function, noninvasive ventilation, some genetic mutations [26], and clinical phenotypes [27]. In addition, there are some biological markers proposed as related to the ALS outcome, including dyslipidemia [28, 29], uric acid [30, 31], creatinine, albumin [4], and granulocyte count [32]. However, it is still unclear whether the WM network parameters have predictive value for the ALS baseline progression rate.

In the present study, we applied graph theoretical analysis to DTI data to compare the topological properties of brain WM networks between ALS patients and healthy controls (HC) at the global, regional and connection levels, and also evaluated the predictive value of the DTI-based connectome for the baseline ALS progression.

Methods

Participants

Seventy-three patients with ALS and 100 age- and sex-matched HCs were included in this study. All patients with ALS fulfilled the El Escorial revised criteria of the World Federation of Neurology for definite or probable ALS and none of them had affected family members. The severity of the disease was evaluated by the ALS functional rating scale-revised (ALSFRS-R). The exclusion criteria for patients were: (1) severe dysarthria and hand weakness; (2) meeting the criteria of ALS-frontotemporal dementia; and (3) a history of other neurologic conditions that could affect the assessment. The cognitive abilities of the ALS patients were estimated using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–revised, Chinese Version. No patient showed significant cognitive impairment according to our prior studies [33, 34] at the time of their neuropsychological assessment. The ALSFRS-R assessed three latent domains corresponding to bulbar, motor and respiratory functions [35, 36], defined as follows: bulbar score = sum of ALSFRS-R questions 1–3 (maximum score 12); motor score = sum of ALSFRS-R questions 4–9 (maximum score 24); respiratory score = sum of ALSFRS-R questions 10–12 (maximum score 12) [35]. The baseline ALS progression rate was calculated as (48 – ALSFRS-R)/time since disease onset [37]. The disease onset time was obtained based on patients’ recall and cross-checked by at least one of the close family members or against medical records if available. The anxiety and depression level of patients was measured by the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Rating Scale. Healthy participants were recruited from local community through poster advertisements. The exclusion criteria for all participants were: (1) presence of focal brain lesions on routine MRI; (2) claustrophobia or standard MRI incompatibility; (3) history of alcohol/substance abuse; (4) comorbidity with neurological or psychiatric disorders or serious physical disease (including traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, chronic liver disease, or other chronic systemic disorders); and (5) poor image quality or severe head motion via visual inspection. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of West China Hospital and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Image acquisition

All participants were scanned using the same magnetic resonance scanner (3.0 T Siemens Trio, Erlangen, Germany) with a 12-channel head coil. Head motion was minimized by foam padding. DTI images were acquired using a spin-echo echo-planar sequence with the following parameters: 64 noncollinear diffusion directions with b = 1000 s/mm2 and a reference image without diffusion weighting (b value = 0), 3 mm slice thickness with no interslice gap, repetition/echo time (TR/TE) 6800/91 ms, field of view 1920 × 1920 mm2, flip angle 90°, voxel 0.94 × 0.94 × 3.0 mm3 and 2 excitations. High-resolution 3D T1-weighted images were acquired using a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence with the following parameters: resolution 1.0 mm × 1.0 mm × 1.0 mm, TR/TE 1900/2.26 ms, inversion time 900 ms; flip angle 9°, FOV 256 × 256 mm2, matrix size 256 × 256, slice thickness 1 mm, no interslice gap, voxel 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 and 176 slices.

Image data processing and network construction

Data preprocessing and WM network construction were conducted mainly using the PANDA software (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/panda/; a pipeline tool for diffusion MRI analysis) [38]. The patient and control samples did not differ in scanning head motion for rotation, transition, and frame-wise displacement (all P > 0.05, Additional file 1: Table S1).

Whole-brain anatomical networks were constructed according to the approach used previously [39]. First, to define the nodes of the network, we used the automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlas to divide the whole brain into 90 cortical and subcortical regions [40], as discussed and used previously [39, 41]. The connections between each pair of brain anatomical regions were determined by the FA value, which resulted in a 90 × 90 matrix for each participant. More details regarding the image processing and network construction work can be found in Additional file 2.

Brain WM network topological measure analyses

We applied a network sparsity parameter, S, to give each network the same number of edges. According to previous studies [42, 43], we selected a range of S thresholds for the WM connectivity network such that: (1) the averaged degree over all nodes of each thresholded network was > 2 × log 90; and (2) the small‐worldness σ of all thresholded networks was > 1.1 in all participants. Based on these criteria, we defined S ranging from 0.1 to 0.34. For each network, the area under the curve (AUC), calculated over the range of S values with an interval step of 0.01, provides a summarized scalar for the topological characterization of brain networks unbiased by any single threshold.

Graph theoretical analysis was carried out on each participant’s WM network using the GRETNA software (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/gretna/) [44]. Both global (clustering coefficient Cp, characteristic path length Lp, normalized clustering coefficient γ, normalized characteristic path length λ, small‐worldness σ, local efficiency Eloc and global efficiency Eglob) and regional metrics (nodal degree, betweenness and efficiency) were used to characterize network topology. For global measures, high values of Cp, γ, and Eloc reflect network segregation, i.e., the ability for specialized neuronal processing carried out among densely interconnected regions; while low values of Lp, λ, and high Eglob reflect network integration, i.e., the ability for global information communication or distributed network integration; σ characterizes an optimized balance between network segregation and integration [45, 46]. For nodal measures, the three kinds of nodal centrality measurements can reflect the topological importance of nodes in the network in different ways. More detailed explanation of topological measures can be found in the Additional file 2.

To detect the altered connectivity networks in patients with ALS, we used an NBS approach (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/nbs/) [47] to define a set of supra-threshold links in which any of the connected components and their sizes could be determined (threshold, t = 2.62, P < 0.05 equal to Cohen’s d = 0.2). The significance of each supra-threshold link among the connected components was estimated using a nonparametric permutation method (10,000 permutations).

Statistical analyses

The demographic characteristics of the ALS and HC groups were compared using the R software (version 4.0.0). A nonparametric permutation test (repeated 10,000 times) was used to analyze between‐group differences in the AUC of global and nodal network metrics. After balancing statistical power against the risk of type I error, for all the nodal metrics, only the nodal centralities that changed in the same direction in at least two out of three different measures were reported [48]. After identification of the between-group differences in global and regional network metrics, partial Pearson’s correlation analyses were performed to assess their relationship with symptom severity including ALSFRS-R and its subscores, depression level and anxiety level, controlling for age, sex and illness duration.

Prediction of the baseline progression rate using single-subject WM network

We further studied whether the single-subject WM network of patients with ALS can be used to predict their baseline progression rate. To increase the robustness of the prediction, the progression rate was binarized to “fast progression” and “slow progression” using a cut-off value of 0.68 per month based on previous studies [49, 50]. To reduce the feature dimension, we converted the raw connection data into principal components (PCs) using principal component analysis (PCA). We fed the PCs which explained 80% variance of the connection data into the linear kernel support vector machine (SVM) algorithm (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). To get the unbiased classification accuracy estimation and tune the hyperparameter C for the SVM, nested cross-validation was used (details found in Additional file 2).

To assess the significance of the prediction and to make sure that the proposed results did not reflect overfitting, we re-ran the study on a randomly permuted dataset. To do this, we shuffled the progression rate tags (slow and fast progression), breaking the relationship between ALS progression and MRI data and re-ran the analysis. This process was repeated for 5000 iterations and thus quantified the ability of the model to predict noise.

Finally, the top 10 PCs with highest weights in the SVM model were then mapped back from PCA space to WM connectivity space to identify the most important brain connections for ALS progression prediction. The predictor importance score for connections was defined as the product of the absolute value of the weight of the PC in SVM model and principal component scores of the connections [51].

Results

Demographic and clinical data

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups in age, sex or years of education (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

| ALS | CON | Statistical significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 73 | 100 | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 49.8 (7.9) | 49.8 (8.7) | t = 0.98, n.s |

| Sex (female/male) | 33/40 | 57/43 | χ2 = 1.9, n.s |

| Education level, mean (SD), years | 9.0 (3.2) | 8.9 (4.1) | t = -0.16, n.s |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 22.4 (2.7) | 22.9 (2.8) | t = -1.3, n.s |

| Bulbar onset (%) | 23.5% | n.a | |

| Disease duration, mean (SD), months | 10.58 (5.86) | n.a | |

| Progression rate, mean (SD), units/montha | 0.71 (0.63) | n.a | |

| Exposure to toxic substances (yes/no)b | 15/58 | n.a | |

| Anxiety level, mean (SD)c | 4.1 (5.2) | n.a | |

| Depression level, mean (SD)d | 7.2 (7.2) | n.a | |

| ALSFRS-R, mean (SD) | 42.0 (3.9) | n.a | |

| ALSFRS-R_bulbar, mean (SD)e | 10.8 (1.8) | n.a | |

| ALSFRS-R_motor, mean (SD)f | 19.1 (3.5) | n.a | |

| ALSFRS-R_resp mean (SD)g | 12 (0) | n.a |

ALS amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, CON healthy controls, ALSFRS-R Revised Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale, n.a. not available, n.s not significant

aCalculated as (48 – ALSFRS-R score)/time since disease onset

bThe toxic substances included pesticides, heavy metals, and organic solvents

cAnxiety level was evaluated by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

dDepression level was evaluated by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

eBulbar score = the sum of ALSFRS-R questions 1–3 (maximum score of 12)

fMotor score = the sum of ALSFRS-R questions 4–9 (maximum score of 24)

gRespiratory score = the sum of ALSFRS-R questions 10–12 (maximum score of 12)

Global and nodal topological alterations of the WM networks

Both the ALS and the HC groups exhibited small-world properties of the WM structural network architecture, with γ > 1 and λ ≈ 1. The patients with ALS showed decreased Cp (P = 0.0034, t = 2.98), γ (P = 0.039, t = 2.08) and σ (P = 0.038, t = 2.10) compared with HC (Fig. 1). These differences were still significant after taking account of the outliers.

Fig. 1.

Abnormal global metrics in patients with ALS compared with HC. The clustering coefficients (a), normalized clustering coefficients (b) and small-worldness index (c) in ALS were significantly decreased compared with HC. Abbreviations: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; HC, healthy controls; Cp, clustering coefficients; Gamma, normalized clustering coefficients; Sigma, small-worldness index

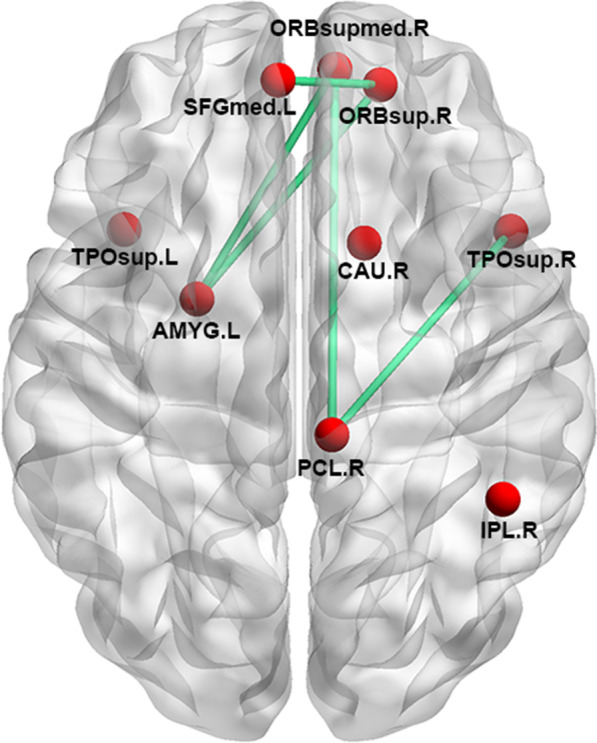

The nodal topological centralities were decreased in patients with ALS compared with the HCs in the right medial orbital frontal cortex, the left medial superior frontal cortex, the right gyrus rectus, the right paracentral lobule, the right inferior parietal cortex, the bilateral superior temporal pole, the left amygdala and the right caudate (P < 0.05, with significant change in the same direction in at least two of three centrality measures) (Fig. 2, Additional file 1: Table S2). Comparing the connections measured by FA values, we found a network less connected in ALS than in HC, with 6 nodes and 5 edges after NBS correction (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Nodal centrality and connection abnormalities in patients with ALS compared with the healthy controls. Nodal centralities in nine nodes (red) were decreased in ALS compared with the HC. Using NBS, 5 connections (green) were decreased in ALS compared with HC. SFGmed, superior frontal gyrus (medial part); TPOsup, temporal pole (superior part); AMYG, amygdala; IPL, inferior parietal lobe; CAU, caudate; ORBsupmed, orbital frontal cortex (superior medial part); ORBsup, orbital frontal cortex (superior part)

Although the head motion parameters between patients and HCs were not significantly different (all P > 0.05, Additional file 1: Table S1), to further minimize the impacts of head motion on the primary results, we also re-ran the between-group comparisons taking all head motion parameters (including 3 translation, 3 rotation and 2 frame-wise displacement measures) as covariates. As expected, all between-group comparisons led to the same results as that obtained before.

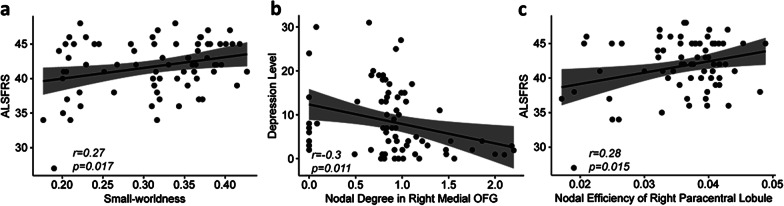

Relationships between topological properties and clinical variables

Exploratory partial Pearson’s correlation analyses showed that the small-worldness indices were positively correlated with ALSFRS (r = 0.27, P = 0.017, Fig. 3a); the degree centrality of the right medial orbital frontal cortex was negatively correlated with depression symptoms (r = − 0.30, P = 0.011) (Fig. 3b) and the nodal efficiency of the right paracentral lobule was positively correlated with ALSFRS (r = 0.28, P = 0.015) (Fig. 3c). After excluding outliers, the correlation between the degree centrality of the right medial orbital frontal cortex and depression symptoms did not reach statistical significance (r = − 0.24, P = 0.051), but all other correlation results remained significant. We also found correlation relationships between network metrics and ALSFRS-R subscores (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Correlations between topological metrics and clinical variables in patients with ALS. a Small-worldness indexes were positively correlated with ALSFRS. b Nodal degree centralities in right medial OFG were negatively correlated with the Hamilton depression scores. c Nodal efficiency centralities in right paracentral lobule were positively correlated with the ALSFRS. Abbreviations: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ALSFRS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale; OFG, orbital frontal gyrus

Table 2.

Correlation between the network metrics and ALSFRS-R subscores

| Network metrics | Class of subscores | r value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cp | Motor | 0.25 | 0.035 |

| Nodal betweenness in R paracentral lobule | Bulbar | 0.29 | 0.013 |

| Nodal efficiency in R paracentral lobule | Bulbar | 0.44 | 0.00013 |

| Nodal efficiency in R caudate | Bulbar | 0.24 | 0.046 |

Cp clustering coefficient, R right

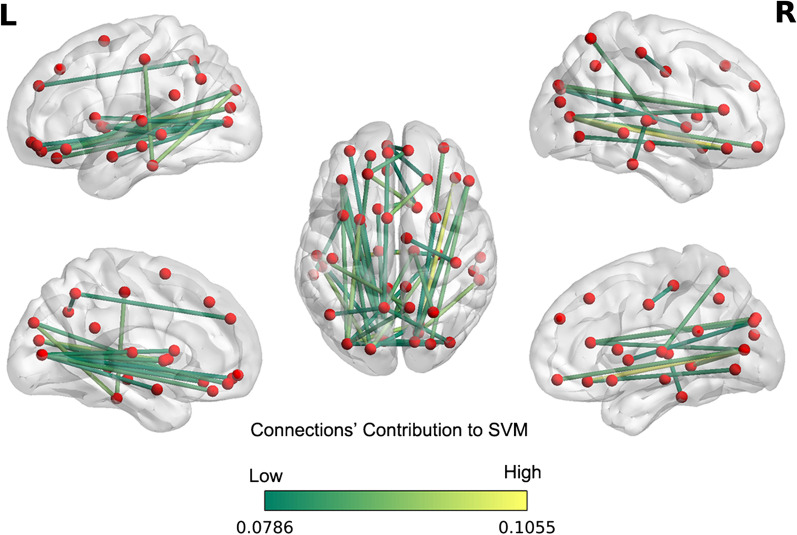

Machine learning analysis using single-subject WM networks to predict ALS progression

The demographic and head motion variables were comparable between the subgroups of fast and slow progression rate (Additional file 1: Table S3). Using WM matrices, the mean balanced classification accuracy for predicting ALS baseline progression rate was 85%, which is well above the chance expectation using the same model (P < 0.05, Additional file 1: Fig. S2). We calculated the predictive importance score for each connection in the WM network. The 50 most relevant WM connections contributing to the SVM classification are shown in Fig. 4 and Table 3.

Fig. 4.

The connections which contributed most to the Support Vector Machine classification. Linear kernel SVM weights of the top 10 principal components were mapped back onto white matter connectivity data. Only the top 50 connections are shown: the color bar represents the predictive importance scores of connections in the WM network feature space. Abbreviations: L, Left; R, right

Table 3.

Top 50 relevant connections contributing to the SVM classification

| White matter connection | Predictive weight |

|---|---|

| Hippocampus L to Thalamus R | 0.105 |

| Inferior orbital frontal gyrus R to Calcarine R | 0.104 |

| Lingual gyrus R to Middle occipital gyrus L | 0.095 |

| Middle occipital gyrus L to Putamen L | 0.095 |

| Calcarine R to Middle temporal gyrus R | 0.094 |

| Superior occipital gyrus L to Inferior temporal gyrus L | 0.093 |

| Superior frontal gyrus L to Caudate R | 0.093 |

| Hippocampus R to Superior occipital gyrus L | 0.092 |

| Superior frontal gyrus R to Supplemental motor area L | 0.092 |

| Postcentral gyrus L to Inferior temporal gyrus L | 0.091 |

| Precuneus R to Superior temporal gyrus L | 0.090 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus (triangular part) R to Superior occipital gyrus R | 0.089 |

| Posterior cingulum R to Calcarine L | 0.088 |

| Middle orbital frontal gyrus R to Calcarine R | 0.087 |

| Inferior orbital frontal gyrus L to Middle occipital gyrus L | 0.087 |

| Precuneus L to Thalamus R | 0.087 |

| Posterior cingulum L to Calcarine R | 0.086 |

| Olfactory R to Caudate L | 0.086 |

| Rectus L to Calcarine L | 0.086 |

| Superior parietal gyrus R to Thalamus R | 0.086 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus (triangular part) R to Cuneus R | 0.085 |

| Superior frontal gyrus L to Medial superior frontal gyrus R | 0.084 |

| Superior orbital frontal gyrus L to Middle occipital gyrus L | 0.084 |

| Inferior orbital frontal gyrus L to Superior occipital gyrus L | 0.084 |

| Middle occipital gyrus L to Precuneus R | 0.084 |

| Calcarine L to Putamen L | 0.084 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus (triangular part) R to Calcarine R | 0.083 |

| Insula L to Calcarine L | 0.083 |

| Inferior orbital frontal gyrus R to Lingual R | 0.082 |

| Calcarine L to Caudate L | 0.082 |

| Superior temporal gyrus R to Inferior temporal gyrus R | 0.082 |

| Middle occipital gyrus R to Precuneus L | 0.082 |

| Medial superior frontal gyrus L to Precuneus L | 0.081 |

| Inferior orbital frontal gyrus L to Calcarine L | 0.081 |

| Insula L to Middle temporal gyrus L | 0.081 |

| Calcarine L to Middle occipital gyrus R | 0.081 |

| Superior medial frontal gyrus R to Medial orbital frontal gyrus L | 0.081 |

| Hippocampus R to Thalamus L | 0.081 |

| Cuneus R to Occipital Mid L | 0.080 |

| Amygdala L to Calcarine L | 0.080 |

| Hippocampus R to Occipital Mid L | 0.079 |

| Middle cingulum R to Postcentral gyrus R | 0.079 |

| Angular L to Precuneus L | 0.079 |

| Medial superior frontal gyrus L to Caudate R | 0.079 |

| Superior occipital gyrus R to Middle occipital gyrus L | 0.079 |

| Middle orbital frontal gyrus L to Calcarine L | 0.079 |

| Lingual R to Superior occipital gyrus L | 0.079 |

| Calcarine L to Superior temporal gyrus L | 0.079 |

| Superior frontal gyrus R to Medial orbital frontal gyrus L | 0.079 |

| Cuneus R to Putamen R | 0.079 |

L left, R right

Discussion

In the present study, we found significant changes in the topological architecture of brain structural network at different levels. At the global level, the whole‐brain WM network showed decreased small-worldness in patients with ALS, reflected by lower σ, and decreased segregation reflected by lower Cp and λ. At the regional level, several nodes located mainly in the frontal, temporal and subcortical regions showed decreased topological centralities in patients with ALS. At the connection level, we found decreased WM connections between the nodes with decreased centralities. In addition, the machine leaning model showed that the single-subject structural connection network can be used as a biomarker to predict the ALS progression rate, which may inspire further clinical practice.

The WM structural networks in patients with ALS showed weaker small-worldization, evidenced by decreased clustering coefficients and small-worldness index. The small‐world organization reflects an optimal balance between network segregation (reflected by Cp, γ, or Eloc) and network integration (reflected by Lp, λ, or Eglob) of information processing [20], and the balance can be measured as σ [52]. Despite having an overall small‐world architecture qualitatively similar to HC, patients with ALS showed lower Cp and γ, resulting in a lower small-worldness index σ. These alterations of small-worldness were positively correlated with ALSFRS, suggesting a clinical relevance.

These results are consistent with a recent multicenter study that reported altered global structural brain network properties in patients with ALS [53]. In contrast, several early studies on WM connectomics have reported no global topological alterations in patients with ALS [21, 22, 54]. Although these studies utilized similar MRI sequences and tracking methods, their sensitivity to these topological changes may have been limited by relatively small sample sizes and/or relatively low numbers of non-collinear diffusion directions in the DTI sequence. Zhang et al. have reported that patients with ALS show a consistent rearrangement towards a regularized architecture evidenced by increased path length and clustering coefficient [23]. This difference may result from different network definitions, as they used the structural covariance networks, in which the connections were defined by the Pearson correlation coefficients between two regions of interest in gray matter. However, rearrangement toward a regularized network itself reflects a breakdown of the original optimal small-world network architecture. No doubtfully, different modalities can provide different perspectives on network abnormalities. In future connectome studies on ALS, different modalities can be combined to include functional MRI, diffusion MRI and gray matter MRI in larger sample sizes.

In addition to the global topological abnormalities, we found topological alterations in several brain regions. Consistent with the recent multicenter study [53], we found decreased nodal centralities in ALS patients in both motor and nonmotor networks including the secondary motor regions, the prefrontal regions, the temporal regions (superior temporal pole), the basal ganglia regions and the parietal region.

The cortical motor system is a distributed network of areas involved in different aspects of specific motor execution. Even simple movements are associated with activation of multiple cortical areas of the primary motor cortex and the secondary motor regions [55–57], including the supplementary cortex, the premotor cortex, the paracentral lobule and the superior parietal motor areas, which are highly inter-connected, converging on the primary motor cortex [58]. Our results suggest that deficits of the secondary motor regions may be an important trait in ALS. Consistent with this, earlier neuroimaging studies have reported decreased cortical thickness and gray matter volume of the secondary motor regions in patients with ALS [59–61].

The pathological hallmarks of ALS are tau-negative and ubiquitin-positive intraneuronal inclusions, and the 43-kDa TAR DNA-binding protein (pTDP-43) is a major component of the inclusions specific for frontotemporal lobar degeneration and ALS [62]. Initially, the TDP-43 burden is greatest in the agranular motor cortex and brainstem motor nuclei [63]. As the disease progresses, the pTDP-43 lesions increasingly involve the prefrontal (gyrus rectus and orbital gyri), striatum, amygdala and temporal lobe along axonal pathways [63, 64]. Consistently, neuroimaging studies in ALS have also confirmed the spread of atrophy and/or hypometabolism to the frontal and temporal cortices [65–67]. DTI studies have also reported WM deficits in the frontotemporal regions [68, 69]. Longitudinal and combined structural and functional MRI studies are needed to validate our hypothesis of disease progression along the functional and structural connections of the frontotemporal network.

We also found that the single-subject networks can predict the disease progression rate with an accuracy of 85%. Earlier studies also found that MRI abnormalities can be used to predict outcome in ALS. More severe abnormalities of the corticospinal tract and the spinal cord predict a poorer long-term clinical outcome in patients with ALS [70, 71]. FA has been proven to be a sensitive DTI metric for both diagnosis [72] and progression modeling [73]. An earlier WM network study has also found a relationship between the FA-based connectivity degree in the frontal area and disease progression rate of patients with ALS [19]. Similarly, using deep learning, van der Burgh and colleagues also predicted outcomes of ALS patients with high accuracy by combining the WM network, morphology and clinical information [74]. As an important alternative approach to studying ALS pathology progression, earlier studies [75–78] also found that alterations of network and other imaging features provide useful information associated with disease progression [79] in the spatial domain. All this evidence indicates that the brain network information has significant predictive potential to predict disease progression in patients with ALS as a supplement to other clinical measures.

The study has several limitations. First, although the method for echo plane imaging-distortion correction (i.e. non-linear registration) used in the current study is common in the field, state-of-the-art distortion correction methods like file-mapping [80], topup-based approach [81–83], or machine learning approaches [84, 85] are encouraged to be used in future studies. Second, currently there is no widely accepted optimal approach to defining nodes and edges. We used the widely used AAL 90 template regions as nodes and mean FA values of fibers as the weighting factor in the construction of graphs. Other measures such as Harvard–Oxford atlas can also be considered for calculating network metrics [38]. Third, this study was cross-sectional; how the WM network architecture associated with ALS evolves dynamically and how the WM network evolves in the progress of disease remain to be clarified in longitudinal studies. Fourth, in this study the progression rate was based on a retrospective interview. As ALS progression is dynamic, a prospective study design would be more suitable for the prediction analysis. Fifth, we did not collect genetic information of the ALS patients. Although genetic factors have less impact on sporadic ALS compared with familial ALS [86], further studies should also collect the genetic information to study the interactions between MRI and genetic information. Finally, to reduce the scanning time and thus limit obstacles to participation, we chose 3-mm slice thickness DWI. This has led to non-isotropic voxels which might have a negative effect on the FA estimation and tractography. High-resolution diffusion-weighted images with isotropic voxel size would be a better choice in future studies, if scanner timing permits.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated disruption of the WM structural networks in ALS, indicated by weaker small-worldness and regional disturbance in the regions outside of the motor systems, which might extend our typical understanding of ALS as a motor disorder; further, the WM structural network has potential to serve as the neuroimaging biomarkers for predicting the progression of ALS. This study also adds to the field of psychoradiology [87–89], an evolving subspecialty of radiology, which is primed to be of major clinical importance in guiding diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making in patients with neuropsychiatric disorders.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Head motion metrics in the participants. Table S2. Nodal topological metrics showing differences between ALS patients and healthy controls. Table S3. Demographic and head motion variables of two subgroups with different progression rate. Figure S1. Scree plot of the proportion of variance explained by each principal component. Figure S2. Classification performance for real and permutated data

Additional file 2. Materials and Methods

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants and their families who supported them.

Abbreviations

- AAL

automated anatomical labelling

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ALSFRS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating

- AUC

area under the curve

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- FA

fractional anisotropy

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PCA

principal component analysis

- PC

principal component

- pTDP-43

43-KDa TAR DNA-binding protein

- SVM

support vector machine

- WM

white matter

Authors' contributions

QQW, YBH, QYG and HFS were involved in study design and participant recruitment. Eligibility and clinical examinations were performed by QQW and YBH. Imaging data collection and assessments were performed by JY, YA, KQ, DL and WBL. Image processing and statistical analysis were performed by WBL and DL. WBL, QQW, DL and GJK drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the funding of 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC18038), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81621003, 81820108018, 81871000, 81761128023), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (PCSIRT, IRT16R52) of China, the Changjiang Scholar Professorship Award (T2014190) of China, the CMB Distinguished Professorship Award (F510000/G16916411) administered by the Institute of International Education, the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019M653427), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2020YFS0220) and Post-Doctor Research Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (2019HXBH029). D.L. was supported by the Newton International Fellowship from the Royal Society.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data and code sharing adopted by the authors comply with the requirements of the funding institute and comply with institutional ethics approval.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of West China Hospital (Registration Name: The clinical and neuroimaging study of neurological diseases; Approval ID: 2013(243)).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

All authors had no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wenbin Li and Qianqian Wei have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Huifang Shang, Email: hfshang2002@163.com.

Qiyong Gong, Email: qiyonggong@hmrrc.org.cn.

References

- 1.Turner MR. MRI as a frontrunner in the search for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis biomarkers? Biomark Med. 2011;5(1):79–81. doi: 10.2217/bmm.10.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, Turner MR, Eisen A, Hardiman O, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):942–955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lomen-Hoerth C, Murphy J, Langmore S, Kramer JH, Olney RK, Miller B. Are amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients cognitively normal? Neurology. 2003;60(7):1094–1097. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000055861.95202.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiò A, Calvo A, Bovio G, Canosa A, Bertuzzo D, Galmozzi F, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis outcome measures and the role of albumin and creatinine: a population-based study. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(9):1134–1142. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarro L, Agosta F, Canu E, Riva N, Prelle A, Copetti M, et al. Cognitive functions and white matter tract damage in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a diffusion tensor tractography study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(10):1866–1872. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciccarelli O, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Talbot K, Orrell RW, Howard RS, et al. Investigation of white matter pathology in ALS and PLS using tract-based spatial statistics. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30(2):615–624. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prudlo J, Bißbort C, Glass A, Grossmann A, Hauenstein K, Benecke R, et al. White matter pathology in ALS and lower motor neuron ALS variants: a diffusion tensor imaging study using tract-based spatial statistics. J Neurol. 2012;259(9):1848–1859. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6420-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Yin X, Zhao L, Evans AC, Song L, Xie B, et al. Regional alterations in cortical thickness and white matter integrity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol. 2014;261(2):412–421. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang M, Chen X, Zhou Q, Liu B, Liu Y, Liu S, et al. Quantitative assessment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with diffusion tensor imaging in 3.0T magnetic resonance. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(5):8295–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agosta F, Pagani E, Petrolini M, Caputo D, Perini M, Prelle A, et al. Assessment of white matter tract damage in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a diffusion tensor MR imaging tractography study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(8):1457–1461. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menke RA, Abraham I, Thiel CS, Filippini N, Knight S, Talbot K, et al. Fractional anisotropy in the posterior limb of the internal capsule and prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(11):1493–1499. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Callaghan C, Bertoux M, Hornberger M. Beyond and below the cortex: the contribution of striatal dysfunction to cognition and behaviour in neurodegeneration. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(4):371–378. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bede P, Iyer PM, Schuster C, Elamin M, McLaughlin RL, Kenna K, et al. The selective anatomical vulnerability of ALS: 'disease-defining' and 'disease-defying' brain regions. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2016;17(7–8):561–570. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2016.1173702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo CC, Tan R, Hodges JR, Hu X, Sami S, Hornberger M. Network-selective vulnerability of the human cerebellum to Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 5):1527–1538. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed RM, Devenney EM, Irish M, Ittner A, Naismith S, Ittner LM, et al. Neuronal network disintegration: common pathways linking neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(11):1234–1241. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warren JD, Rohrer JD, Schott JM, Fox NC, Hardy J, Rossor MN. Molecular nexopathies: a new paradigm of neurodegenerative disease. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36(10):561–569. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verstraete E, Veldink JH, van den Berg LH, van den Heuvel MP. Structural brain network imaging shows expanding disconnection of the motor system in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(4):1351–1361. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bullmore E, Sporns O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(3):186–198. doi: 10.1038/nrn2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortanier E, Grapperon AM, Le Troter A, Verschueren A, Ridley B, Guye M, et al. Structural connectivity alterations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a graph theory based imaging study. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1044. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubinov M, Sporns O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. Neuroimage. 2010;52(3):1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimond D, Ishaque A, Chenji S, Mah D, Chen Z, Seres P, et al. White matter structural network abnormalities underlie executive dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2017;38(3):1249–1268. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verstraete E, Veldink JH, Mandl RC, van den Berg LH, van den Heuvel MP. Impaired structural motor connectome in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Qiu T, Yuan X, Zhang J, Wang Y, Zhang N, et al. Abnormal topological organization of structural covariance networks in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;21:101619. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.101619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei D, Pinaya WHL, van Amelsvoort T, Marcelis M, Donohoe G, Mothersill DO, et al. Detecting schizophrenia at the level of the individual: relative diagnostic value of whole-brain images, connectome-wide functional connectivity and graph-based metrics. Psychol Med. 2020;50(11):1852–1861. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719001934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lei D, Li W, Tallman MJ, Patino LR, McNamara RK, Strawn JR, et al. Changes in the brain structural connectome after a prospective randomized clinical trial of lithium and quetiapine treatment in youth with bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46:1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-00989-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiò A, Logroscino G, Hardiman O, Swingler R, Mitchell D, Beghi E, et al. Prognostic factors in ALS: a critical review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10(5–6):310–323. doi: 10.3109/17482960802566824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiò A, Calvo A, Moglia C, Mazzini L, Mora G. Phenotypic heterogeneity of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(7):740–746. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.235952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein MR, Mascitelli L, Pezzetta F. Dyslipidemia is a protective factor in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 2008;71(12):956. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327866.54482.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorst J, Kühnlein P, Hendrich C, Kassubek J, Sperfeld AD, Ludolph AC. Patients with elevated triglyceride and cholesterol serum levels have a prolonged survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol. 2011;258(4):613–617. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5805-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keizman D, Ish-Shalom M, Berliner S, Maimon N, Vered Y, Artamonov I, et al. Low uric acid levels in serum of patients with ALS: further evidence for oxidative stress? J Neurol Sci. 2009;285(1–2):95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikeda K, Hirayama T, Takazawa T, Kawabe K, Iwasaki Y. Relationships between disease progression and serum levels of lipid, urate, creatinine and ferritin in Japanese patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. Intern Med. 2012;51(12):1501–1508. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paillisse C, Lacomblez L, Dib M, Bensimon G, Garcia-Acosta S, Meininger V. Prognostic factors for survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients treated with riluzole. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2005;6(1):37–44. doi: 10.1080/14660820510027035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu T, Hou Y, Wei Q, Yang J, Luo C, Chen Y, et al. Patterns of brain regional functional coherence in cognitive impaired ALS. Int J Neurosci. 2020;130(8):751–758. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2019.1705806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei Q, Chen X, Zheng Z, Huang R, Guo X, Cao B, et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in a Chinese ALS population. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16(1–2):40–45. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2014.966311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rooney J, Burke T, Vajda A, Heverin M, Hardiman O. What does the ALSFRS-R really measure? A longitudinal and survival analysis of functional dimension subscores in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(5):381–385. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franchignoni F, Mora G, Giordano A, Volanti P, Chiò A. Evidence of multidimensionality in the ALSFRS-R scale: a critical appraisal on its measurement properties using Rasch analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(12):1340–1345. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wainger BJ, Macklin EA, Vucic S, McIlduff CE, Paganoni S, Maragakis NJ, et al. Effect of ezogabine on cortical and spinal motor neuron excitability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(2):186–196. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cui Z, Zhong S, Xu P, He Y, Gong G. PANDA: a pipeline toolbox for analyzing brain diffusion images. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:42. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong G, He Y, Concha L, Lebel C, Gross DW, Evans AC, et al. Mapping anatomical connectivity patterns of human cerebral cortex using in vivo diffusion tensor imaging tractography. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(3):524–536. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gong G, Rosa-Neto P, Carbonell F, Chen ZJ, He Y, Evans AC. Age- and gender-related differences in the cortical anatomical network. J Neurosci. 2009;29(50):15684–15693. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2308-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suo X, Lei D, Li W, Chen F, Niu R, Kuang W, et al. Large-scale white matter network reorganization in posttraumatic stress disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40(16):4801–4812. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suo X, Lei D, Chen F, Wu M, Li L, Sun L, et al. Anatomic insights into disrupted small-world networks in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder. Radiology. 2017;282(3):826–834. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016160907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J, Wang X, Xia M, Liao X, Evans A, He Y. GRETNA: a graph theoretical network analysis toolbox for imaging connectomics. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:386. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dai Z, Lin Q, Li T, Wang X, Yuan H, Yu X, et al. Disrupted structural and functional brain networks in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;75:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao T, Xu Y, He Y. Graph theoretical modeling of baby brain networks. Neuroimage. 2019;185:711–727. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zalesky A, Fornito A, Bullmore ET. Network-based statistic: identifying differences in brain networks. Neuroimage. 2010;53(4):1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lei D, Li K, Li L, Chen F, Huang X, Lui S, et al. Disrupted functional brain connectome in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Radiology. 2015;276(3):818–827. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15141700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gordon PH, Cheung YK. Progression rate of ALSFRS-R at time of diagnosis predicts survival time in ALS. Neurology. 2006;67(7):1314–1315. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000243812.25517.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kimura F, Fujimura C, Ishida S, Nakajima H, Furutama D, Uehara H, et al. Progression rate of ALSFRS-R at time of diagnosis predicts survival time in ALS. Neurology. 2006;66(2):265–267. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194316.91908.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zandvakili A, Barredo J, Swearingen HR, Aiken EM, Berlow YA, Greenberg BD, et al. Mapping PTSD symptoms to brain networks: a machine learning study. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):195. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00879-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bassett DS, Bullmore ET. Small-world brain networks revisited. Neuroscientist. 2017;23(5):499–516. doi: 10.1177/1073858416667720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Basaia S, Agosta F, Cividini C, Trojsi F, Riva N, Spinelli EG, et al. Structural and functional brain connectome in motor neuron diseases: a multicenter MRI study. Neurology. 2020;95(18):e2552–e2564. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buchanan CR, Pettit LD, Storkey AJ, Abrahams S, Bastin ME. Reduced structural connectivity within a prefrontal-motor-subcortical network in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41(5):1342–1352. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanji J. The supplementary motor area in the cerebral cortex. Neurosci Res. 1994;19(3):251–268. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rizzolatti G, Luppino G, Matelli M. The organization of the cortical motor system: new concepts. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;106(4):283–296. doi: 10.1016/S0013-4694(98)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grèzes J, Decety J. Functional anatomy of execution, mental simulation, observation, and verb generation of actions: a meta-analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;12(1):1–19. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200101)12:1<1::AID-HBM10>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krings T, Töpper R, Willmes K, Reinges MH, Gilsbach JM, Thron A. Activation in primary and secondary motor areas in patients with CNS neoplasms and weakness. Neurology. 2002;58(3):381–390. doi: 10.1212/WNL.58.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Senda J, Kato S, Kaga T, Ito M, Atsuta N, Nakamura T, et al. Progressive and widespread brain damage in ALS: MRI voxel-based morphometry and diffusion tensor imaging study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12(1):59–69. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2010.517850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mezzapesa DM, D'Errico E, Tortelli R, Distaso E, Cortese R, Tursi M, et al. Cortical thinning and clinical heterogeneity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e80748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mohammadi B, Kollewe K, Cole DM, Fellbrich A, Heldmann M, Samii A, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis affects cortical and subcortical activity underlying motor inhibition and action monitoring. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36(8):2878–2889. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Okamoto K. Ubiquitin-positive tau-negative intraneuronal inclusions in dementia with motor neuron disease: the 50th anniversary of Japanese Society of Neuropathology. Neuropathology. 2010;30(5):486–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2010.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Toledo JB, Robinson JL, Irwin DJ, Grossman M, et al. Stages of pTDP-43 pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(1):20–38. doi: 10.1002/ana.23937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoshida M. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with dementia: the clinicopathological spectrum. Neuropathology. 2004;24(1):87–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2003.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buhour MS, Doidy F, Mondou A, Pélerin A, Carluer L, Eustache F, et al. Voxel-based mapping of grey matter volume and glucose metabolism profiles in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EJNMMI Res. 2017;7(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13550-017-0267-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ogura A, Watanabe H, Kawabata K, Ohdake R, Tanaka Y, Masuda M, et al. Semantic deficits in ALS related to right lingual/fusiform gyrus network involvement. EBioMedicine. 2019;47:506–517. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Machts J, Loewe K, Kaufmann J, Jakubiczka S, Abdulla S, Petri S, et al. Basal ganglia pathology in ALS is associated with neuropsychological deficits. Neurology. 2015;85(15):1301–1309. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Canu E, Agosta F, Riva N, Sala S, Prelle A, Caputo D, et al. The topography of brain microstructural damage in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis assessed using diffusion tensor MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(7):1307–1314. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Du XQ, Zou TX, Huang NX, Zou ZY, Xue YJ, Chen HJ. Brain white matter abnormalities and correlation with severity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an atlas-based diffusion tensor imaging study. J Neurol Sci. 2019;405:116438. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.116438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agosta F, Pagani E, Petrolini M, Sormani MP, Caputo D, Perini M, et al. MRI predictors of long-term evolution in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32(9):1490–1496. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Querin G, El Mendili MM, Lenglet T, Delphine S, Marchand-Pauvert V, Benali H, et al. Spinal cord multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging for survival prediction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(8):1040–1046. doi: 10.1111/ene.13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bede P, Iyer PM, Finegan E, Omer T, Hardiman O. Virtual brain biopsies in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: diagnostic classification based on in vivo pathological patterns. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;15:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Müller HP, Turner MR, Grosskreutz J, Abrahams S, Bede P, Govind V, et al. A large-scale multicentre cerebral diffusion tensor imaging study in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(6):570–579. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-311952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van der Burgh HK, Schmidt R, Westeneng HJ, de Reus MA, van den Berg LH, van den Heuvel MP. Deep learning predictions of survival based on MRI in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;13:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Trojsi F, Caiazzo G, Corbo D, Piccirillo G, Cristillo V, Femiano C, et al. Microstructural changes across different clinical milestones of disease in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0119045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sorrentino P, Rucco R, Jacini F, Trojsi F, Lardone A, Baselice F, et al. Brain functional networks become more connected as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis progresses: a source level magnetoencephalographic study. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;20:564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Serra A, Galdi P, Pesce E, Fratello M, Trojsi F, Tedeschi G, et al. Strong-weak pruning for brain network identification in connectome-wide neuroimaging: application to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis disease stage characterization. Int J Neural Syst. 2019;29(7):1950007. doi: 10.1142/S0129065719500072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Canosa A, Calvo A, Moglia C, Manera U, Vasta R, Di Pede F, et al. Brain metabolic changes across King's stages in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a (18)F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose-positron emission tomography study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(4):1124–1133. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05053-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roche JC, Rojas-Garcia R, Scott KM, Scotton W, Ellis CE, Burman R, et al. A proposed staging system for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 3):847–852. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jezzard P, Balaban RS. Correction for geometric distortion in echo planar images from B0 field variations. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(1):65–73. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Andersson JL, Skare S, Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2003;20(2):870–888. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Irfanoglu MO, Modi P, Nayak A, Hutchinson EB, Sarlls J, Pierpaoli C. DR-BUDDI (Diffeomorphic Registration for Blip-Up blip-Down Diffusion Imaging) method for correcting echo planar imaging distortions. Neuroimage. 2015;106:284–299. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Holland D, Kuperman JM, Dale AM. Efficient correction of inhomogeneous static magnetic field-induced distortion in Echo Planar Imaging. Neuroimage. 2010;50(1):175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zahneisen B, Baeumler K, Zaharchuk G, Fleischmann D, Zeineh M. Deep flow-net for EPI distortion estimation. Neuroimage. 2020;217:116886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hu Z, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Zhang H, Guo C, et al. Distortion correction of single-shot EPI enabled by deep-learning. Neuroimage. 2020;221:117170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gill AL, Premasiri AS, Vieira FG. Hypothesis and theory: roles of arginine methylation in C9orf72-mediated ALS and FTD. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:633668. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.633668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Huang X, Gong Q, Sweeney JA, Biswal BB. Progress in psychoradiology, the clinical application of psychiatric neuroimaging. Br J Radiol. 2019;92(1101):20181000. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20181000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sun H, Chen Y, Huang Q, Lui S, Huang X, Shi Y, et al. Psychoradiologic utility of mr imaging for diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a radiomics analysis. Radiology. 2018;287(2):620–630. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li F, Sun H, Biswal BB, Sweeney JA, Gong Q. Artificial intelligence applications in psychoradiology. Psychoradiology. 2021;1(2):94–107. doi: 10.1093/psyrad/kkab009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Head motion metrics in the participants. Table S2. Nodal topological metrics showing differences between ALS patients and healthy controls. Table S3. Demographic and head motion variables of two subgroups with different progression rate. Figure S1. Scree plot of the proportion of variance explained by each principal component. Figure S2. Classification performance for real and permutated data

Additional file 2. Materials and Methods

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data and code sharing adopted by the authors comply with the requirements of the funding institute and comply with institutional ethics approval.