Abstract

Desbuquois dysplasia type 1 (DBQD1) is a very rare skeletal dysplasia characterized by growth retardation, short stature, distinct hand features, and a characteristic radiological monkey wrench appearance at the proximal femur. We report on 2unrelated Egyptian patients having the characteristic features of DBQD1 with different expressivity. Patient 1 presented at the age of 45 days with respiratory distress, short limbs, faltering growth, and distinctive facies while patient 2 presented at 5 years of age with short stature and hypospadias. The 2 patients shared radiological features suggestive of DBQD1. Whole-exome sequencing revealed a homozygous frameshift mutation in the CANT1 gene (NM_001159772.1:c.277_278delCT; p.Leu93ValfsTer89) in patient 1 and a homozygous missense mutation (NM_138793.4:c.898C>T; p.Arg300Cys) in patient 2. Phenotypic variability and variable expressivity of DBQD was evident in our patients. Hypoplastic scrotum and hypospadias were additional unreported associated findings, thus expanding the phenotypic spectrum of the disorder. We reviewed the main features of skeletal dysplasias exhibiting similar radiological manifestations for differential diagnosis. We suggest that the variable severity in both patients could be due to the nature of the CANT1 gene mutations which necessitates the molecular study of more cases for phenotype-genotype correlations.

Keywords: Desbuquois dysplasia, CANT1, Hyperphalangism, Prominent lesser trochanter, Genotype-phenotype correlation

Introduction

Desbuquois dysplasia (DBQD; OMIM #251450) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim), first described by Desbuquois et al. [1966], is a very rare skeletal dysplasia with autosomal recessive inheritance. DBQD is considered as one of the multiple dislocation group disorders according to the International Nosology of Genetic Skeletal Disorders [Mortier et al., 2019]. The disease has variable expressivity [Nishimura et al., 1999] and severe prenatal cases were reported [Baynam et al., 2010; Laccone et al., 2011; Inoue et al., 2014]. It is characterized by pre- and postnatal growth failure, micromelic dwarfism, spondylometaphyseal abnormalities, osteopenia, advanced carpotarsal ossification, joint laxity, and progressive scoliosis. It is associated with characteristic dysmorphic features including a flat round face, prominent eyes, flat nasal bridge, midface hypoplasia, short nose, microstomia, high-arched palate, and microretrognathia resembling Pierre Robin anomaly. There also may be cognitive impairment. Patients often suffer from recurrent chest infections due to thoracic cage hypoplasia resulting in respiratory failure and death very early in life. The radiological finding of metaphyseal flaring with prominent lesser trochanter, resembling a monkey wrench “Swedish key” appearance of the proximal femora is considered as a hallmark for the diagnosis. In addition, there are other characteristic radiological features such as horizontal acetabular roofs with dislocation of the femoral heads, and coronal clefting of the vertebrae with delayed maturation of the long bone epiphysis. Hand radiological findings include a small delta-shaped extraphalangeal bone, “hyperphalangism of the index finger” distal to the second metacarpal, leading to radial deviation of the index finger, bifid distal phalanx of the thumb, and phalangeal dislocations [Le Merrer et al., 1991; Shohat et al., 1994; Gillessen-Kaesbach et al., 1995; Faivre et al., 2003, 2004a, b; Al Kaissi et al., 2009a, b; Furuichi et al., 2011]. These findings are not universal for all patients; thus, DBQD was divided into 2 subgroups based on the presence (type 1) or absence (type 2) of an extra phalanx or an extra ossification center of the index finger, and thumb changes [Faivre et al., 2004c]. The mortality rate for type 1 Desbuquois dysplasia (DBQD1) is nearly 33% [Hall, 2001]. Type 2 (DBQD2) accounts for more than 50% of the DBQD cases which only presents with minor hand changes such as malalignment of the interphalangeal joints and brachydactyly [Faivre et al., 2004c]. There is a clinical subtype resembling type 2 called Kim variant [Kim et al., 2010] in which the hand shape is apparently normal; however, there are radiographic findings in the hands in the form of short metacarpals, elongated phalanges, advanced carpal bone age, and osteoarthritis of the hand and spine [Kim et al., 2010; Furuichi et al., 2011].

DBQD1 is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the calcium-activated nucleotidase 1 gene (CANT1) [Huber et al., 2009]. The mutation is located in 17q25.3 [Faivre et al., 2003]. CANT1 is an extracellular protein that acts as a nucleotide tri- and diphosphatase. Its main function is the hydrolysis of uridine diphosphate (UDP), guanosinediphosphate (GDP), uridine triphosphate (UTP), and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) [Failer et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2002; Smith and Kirley, 2006]. CANT1 is expressed in the chondrocytes [Huber et al., 2009]. Type 2 is caused by mutations in the XYLT1 gene in chromosome 16p12 [Bui et al., 2014]. Type 2 can also be caused by mutations in CANT1, and so the presence or absence of hand anomalies cannot predict the molecular etiology of the disease [Furuichi et al., 2011]. Hence, all 3 variants of the disorder (DBQD1, DBQD2, and Kim variant) representing a phenotypic spectrum are caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the CANT1 gene [Baynam et al., 2010; Faden et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2010; Furuichi et al., 2011; Laccone et al., 2011; Forster et al., 2019; Kuang et al., 2020].

Here, we report 2 unrelated Egyptian patients with classical features of DBQD1 carrying homozygous CANT1 mutations confirmed by whole-exome sequencing. Their phenotype showed different grades of severity.

Case Presentations

Patient 1

A full-term 40-day-old female infant was the second child of healthy, consanguineous parents. They are first cousins. The mother was a 31-year-old female and the father was 37 years old at the time of delivery. Her elder brother is healthy. Pregnancy history was uneventful. No history of repeated abortions, early infant deaths, or maternal drug administration was recorded.

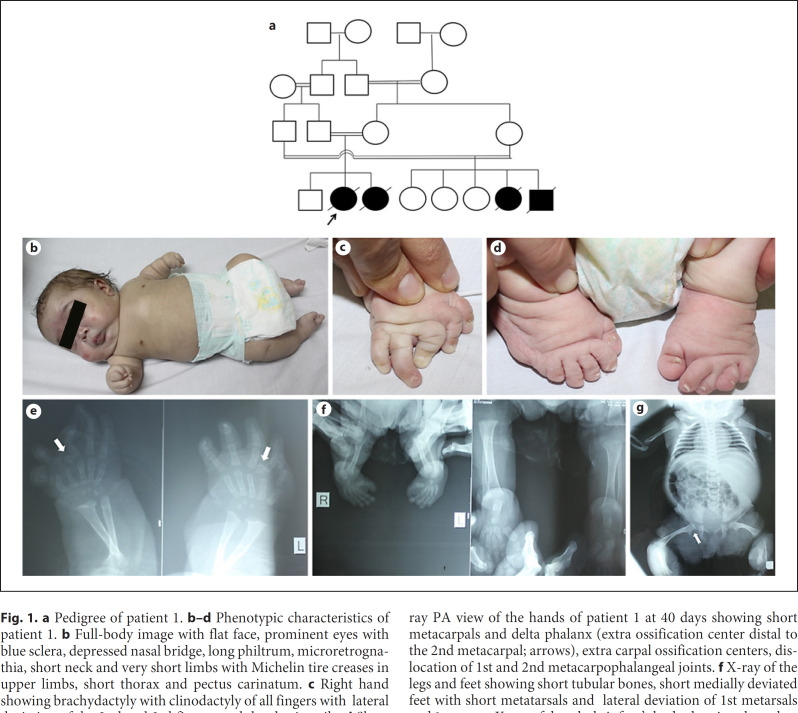

The baby was delivered by cesarean section at 38 weeks of gestation. Birth weight was 1.85 kg (−2.7 SD). She was incubated after birth for 1 month due to respiratory distress and was put on mechanical ventilation. She was discharged with a nasogastric tube for feeding. Her family history was positive with 2 similarly affected cousins as shown in Figure 1a. She was referred to the clinical genetics department of the National Research Center due to respiratory distress, short limbs, and faltering growth. On examination, weight, length, and head circumference were 1.7 kg (−4.5 SD), 35 cm (−9.5 SD), and 32 cm (−3 SD), respectively. She presented with short limbs and dysmorphic facies, including a round flat face, prominent eyes with blue sclera, depressed nasal bridge, low-set ears, long philtrum, microstomia, microretrognathia, and midface hypoplasia. She had a short neck and very short limbs with Michelin tire creases in the upper limbs, narrow chest with widely spaced nipples, and pectus carinatum (Fig. 1b). She had bilateral clasped thumbs, brachydactyly, clinodactyly of all fingers with lateral deviation of 2nd and 3rd fingers, camptodactyly of the right middle finger, and dysplastic nails (Fig. 1c). Short flat feet were present bilaterally with low insertion of the big toe, dysplastic nails, medial deviation of left 2nd to 5th toes, and overlapping left 2nd and 4th toes over the 3rd toe (Fig. 1d). She also had generalized joint laxity and showed tachypnea with chest retractions. She had a history of recurrent chest infections and poor feeding with subsequent failure to thrive. Radiological evaluation was done at the age of 45 days with findings suggestive of DBQD1. Plain X-ray of the hands revealed advanced carpal ossification, an extra-ossification center at the base of the proximal phalanx of the index finger (delta-shaped extra phalanx) with radial deviation of index fingers, dislocation of 1st and 2nd metacarpophalangeal joints, bilateral clinodactyly and brachydactyly with camptodactyly of the right middle finger (Fig. 1e). The radiological findings of the pelvis and lower limbs included a “Swedish key” appearance of the proximal femora and metaphyseal flaring with medial spike and exaggerated lesser trochanter, bilateral short tubular bones, short medially deviated feet with short metatarsals, and lateral deviation of the 1st metatarsals and 1st toes (Fig. 1f). Plain X-ray of the chest depicted a short thorax with narrow horizontal ribs (Fig. 1g). Complete blood count revealed mild normochromic normocytic anemia. Cranial ultrasound and duplex revealed mild to moderate cerebral hypoxia. Pelvic-abdominal ultrasound revealed hepatomegaly, bilateral mild hydronephrosis, and distended urinary bladder with bilateral vesico-ureteral pelvic reflux (atonic bladder). Chromosomal analysis showed a normal 46,XX karyotype. The child died at the age of 6 months from respiratory failure. Follow-up of the next pregnancy by fetal ultrasound at 22 weeks of gestation revealed similarly affected fetal features with severe shortening of the long bones, and deviated fingers, depressed nose, small mandible, and short neck. The baby was incubated immediately after birth and died at 5 days of age from severe respiratory failure.

Fig. 1.

a Pedigree of patient 1. b–d Phenotypic characteristics of patient 1. b Full-body image with flat face, prominent eyes with blue sclera, depressed nasal bridge, long philtrum, microretrognathia, short neck and very short limbs with Michelin tire creases in upper limbs, short thorax and pectus carinatum. c Right hand showing brachydactyly with clinodactyly of all fingers with lateral deviation of the 2nd and 3rd fingers and dysplastic nails. d Short flat feet with low insertion of the big toes, dysplastic nails, medial deviation of left 2nd to 5th toes and overlapping left 2nd and 4th toes over the 3rd toe. e–g Radiographic features of patient 1. e X-ray PA view of the hands of patient 1 at 40 days showing short metacarpals and delta phalanx (extra ossification center distal to the 2nd metacarpal; arrows), extra carpal ossification centers, dislocation of 1st and 2nd metacarpophalangeal joints. f X-ray of the legs and feet showing short tubular bones, short medially deviated feet with short metatarsals and lateral deviation of 1st metarsals and 1st toes. g X-ray of the whole infant's body showing short thorax with narrow space between ribs, flat acetabular roof and prominent lesser trochanter giving the appearance of Swedish key of the proximal femur (notched arrow).

Patient 2

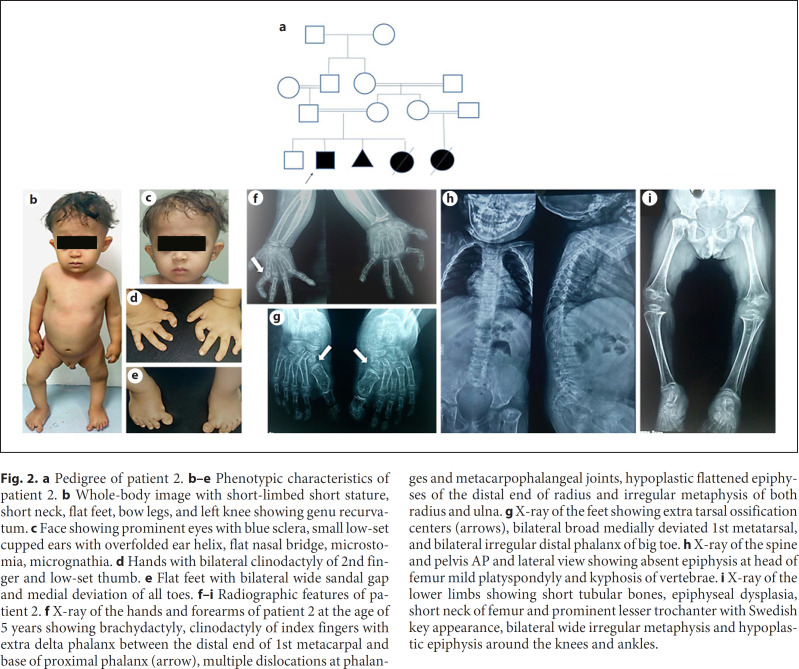

A 5-year-old male child was referred to the Multiple Congenital Anomalies Clinic of the National Research Center because of short stature and hypospadias. His parents gave a history of spontaneously closed cardiac septal defect. He is the second child of healthy first-degree consanguineous parents. The pregnancy history revealed no history of maternal illness nor any drug or hormone intake. Prenatal ultrasound revealed intrauterine growth retardation and limb deformities. Pedigree analysis showed a previous spontaneous abortion at 2 months of unknown cause, a similarly affected female sib with coronary heart disease and severe skeletal and limb deformities who died in the first week of life due to her heart condition. The parents also gave a history of a similarly affected family member (proband's cousin) who died at 3 days of age of the same clinical condition as shown in Figure 2 a. The proband was short with a severe low birth weight of 1 kg (−4.7 SD) at delivery. General physical examination showed that the child had growth retardation, delayed motor development, and limb anomalies with waddling gait. Anthropometric measurements revealed severe growth delay in all parameters: weight was 8.5 kg (−4.5 SD), length was 71 cm (−7.8 SD), and head circumference was 44 cm (−5.8 SD). Facial examination showed abnormal features with characteristic dysmorphic facies including broad wide forehead with sparse hair, sparse eye brows, round flat face, prominent wide anti-mongoloid eyes with blue sclera, mid-face hypoplasia, short nose, depressed nasal bridge, microstomia, long flat philtrum, microretrognathia, small low-set cupped ears with overfolded helix, and short neck (Fig. 2b, c). Neurological examination showed hypotonia with brisk tendon reflexes. Genital examination showed penile hypospadias and hypoplastic scrotum but with normal-sized palpable gonads. Chest examination revealed narrow thorax, wide-spaced asymmetric nipples, and scoliosis. Skeletal examination confirmed disproportionate short stature with short limbs, narrow thorax, thoraco-lumber kyphosis, lordosis, and severe joints hyperextensibility. Brachydactyly of fingers was present in both hands with clinodactyly of all fingers except the 3rd finger on the left hand. Thumbs were broad and clasped, and index fingers were deformed and radially deviated (Fig. 2d). Micromelia was noticed affecting the 4 limbs with bilateral bowing of both legs, genu recurvatum of the left knee, and wide, broad hyperextensible knee joints. Both feet were short, stubby, and broad, with brachydactyly, medially deviated toes, deformed big toes, pes planus, and sandal gap (Fig. 2e). Skeletal survey showed severe generalized osteopenia. Skull X-ray depicted enlarged wide sella turcica and wormian bone appearance. X-ray of the upper limbs showed short long bones with hypoplastic flattened epiphyses of the distal end of the radius, and irregular metaphysis of both radius and ulna. Broadening of metaphyses of the long bones was less severe than those of the lower limbs. Radioulnar dislocation was evident in both upper limbs. X-ray hands at 5 years revealed brachydactyly with radial deviation of both little fingers, ulnar deviation of both index fingers, and deformed distal phalanx of the thumbs. Accessory ossification center distal to the 2nd metacarpal bone (delta-shaped extra phalanx), and short 1st and 2nd metacarpals were evident in both hands with multiple dislocations at phalanges and metacarpophalangeal joints (Fig. 2f). X-ray of the lower limbs showed short long bones, bilateral genu vara, nonvisualized femoral capital epiphyses, broad metaphysis, and “monkey wrench” appearance of the femoral heads. Short femur, tibia and fibula were evident in both lower limbs with flat epiphysis, irregular broad metaphyseal ends, and overgrowth of the proximal end of the fibula. X-ray of the feet showed brachydactyly, medial deviation, and enlarged broad 1st metatarsals with irregular distal phalanx of the big toes, phalangeal dislocations, and delta-like phalanx (Fig. 2g). X-ray of the spine showed osteoporosis, lumbar lordosis, kyphosis, narrowing of the intervertebral disc spaces, and platyspondyly mainly at the thoracic vertebrae (Fig. 2h). Chest X-ray revealed a narrow thorax with deformed thoracic cage and broad, flat anterior ribs. X-ray of the pelvis showed a typical “Swedish key” proximal femur (flat proximal femoral metaphysis with medial spike and exaggerated lesser trochanter), elevated greater trochanter, short wide femoral neck, and shallow acetabular roof (Fig. 2i). MRI brain, echocardiography, pelvic-abdominal ultrasound, hearing test, and fundus examination were all normal.

Fig. 2.

a Pedigree of patient 2. b–e Phenotypic characteristics of patient 2. b Whole-body image with short-limbed short stature, short neck, flat feet, bow legs, and left knee showing genu recurvatum. c Face showing prominent eyes with blue sclera, small low-set cupped ears with overfolded ear helix, flat nasal bridge, microstomia, micrognathia. d Hands with bilateral clinodactyly of 2nd finger and low-set thumb. e Flat feet with bilateral wide sandal gap and medial deviation of all toes. f–i Radiographic features of patient 2. f X-ray of the hands and forearms of patient 2 at the age of 5 years showing brachydactyly, clinodactyly of index fingers with extra delta phalanx between the distal end of 1st metacarpal and base of proximal phalanx (arrow), multiple dislocations at phalanges and metacarpophalangeal joints, hypoplastic flattened epiphyses of the distal end of radius and irregular metaphysis of both radius and ulna. g X-ray of the feet showing extra tarsal ossification centers (arrows), bilateral broad medially deviated 1st metatarsal, and bilateral irregular distal phalanx of big toe. h X-ray of the spine and pelvis AP and lateral view showing absent epiphysis at head of femur mild platyspondyly and kyphosis of vertebrae. i X-ray of the lower limbs showing short tubular bones, epiphyseal dysplasia, short neck of femur and prominent lesser trochanter with Swedish key appearance, bilateral wide irregular metaphysis and hypoplastic epiphysis around the knees and ankles.

Coventional chromosome banding showed a normal 46,XY karyotype. Table 1 shows the main clinical and radiographic features of our 2 DBQD patients.

Table 1.

Clinical and radiographic features of the 2 reported Desbuquois dysplasia patients

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at presentation | 40 days* | 5 years |

| Sex | Female | Male |

| Parental consanguinity | + | + |

| Family history | + | + |

|

| ||

| Anthropometric measurements | ||

| Weight/kg (SD) | 1.7 (−4.5) | 8.5 (−4.5) |

| Lenght/cm (SD) | 35 (−9.5) | 71 (−7.8) |

| Head circumference/cm (SD) | 32 (−3) | 44 (−5.8) |

| Growth failure | + | + |

| Short stature | + | + |

| Microcephaly | + | + |

|

| ||

| Characteristic facial dysmorphism | ||

| Flat round face | + | + |

| Midface hypoplasia | + | + |

| Prominent eyes | + | + |

| Flat nasal bridge | + | + |

| Short nose | + | + |

| Microstomia | + | + |

| Microretrognathia | + | + |

| Cleft palate | − | − |

| Short neck | + | + |

| Narrow chest | + | + |

| Joint laxity | + | + |

| Joint dislocation | + | + |

|

| ||

| Radiological findings | ||

| Upper limb and hand anomalies | ||

| Osteoporosis | − | + |

| Short long bones | + | + |

| Broad metaphyses | + | + |

| Delta-shaped extraphalangeal bone of index finger | + | + |

| Clinodactyly | + | + |

| Advanced carpal/tarsal ossification | +/+ | |

| Dislocation of metacarpophalangeal joint of index finger | + | + |

| Bifid distal phalanx of the thumb | − | − |

| Pelvis and lower limb anomalies | ||

| Metaphyseal flaring with prominent lesser trochanter (Swedish key) | + | + |

| Flat acetabular roof | + | + |

| Feet anomalies | ||

| Brachdactyly | + | + |

| Medial deviation, bilateral enlarged broad 1st metatarsals | + | + |

| Phalangeal dislocations | + | + |

| Delta-like phalanx | + | + |

| Spinal abnormalities | ||

| Coronal or sagittal clefting of vertebrae | − | + |

| Kyphoscoliosis | − | + |

| Platyspondyly | − | + |

| Cervical spine abnormalities | − | − |

| Wide anterior ribs | + | + |

| Other abnormalities | ||

| Respiratory distress | + | |

| Congenital heart disease | − | + |

| Visceral anomalies | + (hepatomegaly, bilateral mild hydronephrosis) | − |

| Hearing loss | NA | − |

| Penile hypospadias and hypoplastic scrotum | + | |

| Molecular testing | Homozygous deletion mutation in CANT1 (g.76993427_76993428delAG; p.leu93 fs) | Homozygous missense mutation in exon 4 in CANT1 (c.898C>T; p. R300C) |

Patient died at 6 months of age. NA, not available. +, present; −, absent.

Molecular Methods and Results

Peripheral blood samples were collected from the patients and genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood lymphocytes of the patients. DNA was extracted using the PAX gene Blood DNA Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Concentration and purity were measured by Nanodrop spectrophotometer. Whole-exome sequencing was performed according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, exon enrichment was performed using Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon exome. FASTQ were generated from the sequencing platform. BAM files were performed with Samtools. Analysis of variants was done by a range of web-based bioinformatics tools (IlluminaBaseSpace, GenecardsVarelect, Ensembl SNP Effect Predictor, dbSNP, Human Gene Mutation Database, and Exome Variant Server). Whole-exome sequencing for patient 1 revealed a homozygous frameshift mutation (rs587776897) in the CANT1 gene (NM_001159772.1:c.277_278delCT; p.Leu93ValfsTer89) thus confirming the diagnosis of DBQD1. Whole-exome sequencing for patient 2 revealed a homozygous missense mutation (rs267606701) in CANT1 (NM_138793.4:c.898C>T; p.Arg300Cys) also confirming the diagnosis of DBQD1.

Discussion

Desbuquois syndrome is an autosomal recessive chondrodysplasia characterized by severe pre- and postnatal growth retardation, joint laxity, short extremities, and characteristic skeletal findings in the femur and hands with progressive scoliosis.

Herein, we presented 2 unrelated patients with the classical features of DBQD1 but with variable severities. The onset of presentation in patient 1 was very early (since birth), and she died at 6 months. In patient 2, age at onset was 5 years with a milder form.

Full pedigree analysis revealed consanguineous parents with positive family history supporting the autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. This is in agreement with previous studies reporting the autosomal recessive inheritance pattern of DBQD type 1 [Faivre et al., 2004b].

On clinical examination, both patients shared the same diagnostic features of DBQD1 including short limb dwarfism, growth failure, thoracic hypoplasia, joint laxity, and characteristic dysmorphic features. They both displayed the typical skeletal characteristics including a “Swedish key” appearance of the proximal end of femur with metaphyseal flaring. Radiological findings of the hands revealed advanced carpal ossification, an extra-ossification center (hyperphalangism) at the base of the proximal phalanx of the index finger (delta-shaped extra phalanx) with radial deviation of the index fingers. This was consistent with previous studies [Le Merrer et al., 1991; Ogle et al., 1994; Shohat et al., 1994; Gillessen-Kaesbach et al., 1995]. Supernumerary ossification centers and thumb changes were reported in 46% of the patients. 54% of the cases were described as having atypical changes [Faivre et al., 2004c].

The first patient exhibited more severe clinical manifestations mostly in form of lung hypoplasia which was the cause of death very early in life, while the other patient presented with mild respiratory complications and better survival outcome. The second patient was also severely affected but with a milder course and disease outcome. Differences in disease severity have been reported in many studies [Le Merrer et al., 1991; Jequier et al., 1992; Al-Gazeli et al., 1996; Nishimura et al., 1999; Hall, 2001; Lloyd et al., 2006; Al Kaissi et al., 2009b; Faden et al., 2010; Laccone et al., 2011; Inoue et al., 2014].

In the present study, kyphosis and scoliosis were more evident in patient 2 as compared to patient 1. This could be due to the age difference and long-term complications emerging with age progression. These complications commonly include pneumonia [Jequier et al., 1992], aspiration [Shohat et al., 1994], psychomotor delay [Jequier et al., 1992; Shohat et al., 1994; Faivre et al., 2004a], joint deformities [Shohat et al., 1994], and chest and spine deformities [Ogle et al., 1994] which usually require orthopedic surgery and often result in walking difficulties [Faivre et al., 2004a].

In this study, patient 2 had penile hypospadias and hypoplastic scrotum. To the best of our knowledge, these new findings have not been reported before in the literature in cases with DBQD1, expanding the clinical spectrum of the disorder.

The phenotype of our patients diagnosed with DBQD1 should be differentiated from DBQD2 [OMIM #615777] which shares clinical and radiological similarities but with the absence of the delta phalanx and only presents with minor changes of the hand, such as malalignment of the inter-phalangeal joints and brachydactyly [Faivre et al., 2004c]. There is a subtype of DBQD2 called Kim type [OMIM #251450) resembling type 2 Desbuquois dysplasia with short metacarpals and elongated phalanges together with advanced carpal bone age and severe precocious osteoarthritis of the hand and spine. It is due to mutation in the CANT1 gene [Kim et al., 2010].

DBQD1 is clinically and radiologicaly heterogeneous and should be differentiated from other skeletal dysplasias having brachydactyly, hyperphalangism, and abnormal carpal bones with extra skeletal manifestations such as Temtamy preaxial brachydactyly syndrome, brachydactyly typ C, Catel-Manzke syndrome, and Chitayat syndrome. DBQD1 should also be differentiated from other bone dysplasias with multiple joint dislocations such as Larsen syndrome, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia recessive type, dyssegmental dysplasia (Silverman-Handmaker and Rolland-Desbuquois types), lethal neonatal short limb dysplasia with multiple dislocations, and spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia with joint dislocations. Syndromes with overlapping features are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overlapping syndromes with Desbuquois dysplasia type 1

| OMIM number | Mode of inheritance | Overlapping features | Other characteristic features | Reference | Gene mutation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temtamy preaxial brachydactyly syndrome | 605282 | AR | Brachydactyly, hyperphalangism, abnormal carpal bones with extra skeletal manifestations | Psychomotor delay, growth retardation, SNHL, dental abnormalities (misalignment of teeth, talon cusps, microdontia), and characteristic facies (plagiocephaly, round face, hypertelorism, malar hypoplasia, malformed ears, microstomia, micro/retrognathia) | Temtamy et al., 1998 | CHSY1, Li et al., 2010 |

|

|

|

|||||

| Brachydactyly typ C | 113100 | AD | Brachydactyly of the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th fingers, unusually shaped bones and/or epiphysis | Temtamy and Aglan, 2008 | GDF5, Everman et al., 2002 | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Catel-Manzke syndrome | 616145 | AR | Pierre Robin sequence (micrognathia, cleft palate, glossoptosis) | Manzke et al., 2008 | TGDS, Ehmke et al., 2014 | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Chitayat syndrome | 617180 | AD | Mild facial dysmorphism and respiratory complications since birth | Chitayat et al., 1993 | ERF, Suter et al., 2020 | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Chondrodysplasia gPAPP type (includes Catel-Manzke-like syndrome) | 280586 | AR | Micrognathia, posterior cleft palate, dysmorphic facies, psychomotor delay, hearing impairment | Vissers et al., 2011 | IMPAD1, Vissers et al., 2011 | |

|

| ||||||

| Larsen syndrome | 150250 | AD | Bone dysplasias with multiple joint dislocations | Foot deformities, cervical spine dysplasia, scoliosis, spatula-shaped distal phalanges, cleft palate, characteristic facies (prominent forehead, depressed nasal bridge, hypertelorism) | Larsen et al., 1950 | FLNB, Krakow et al., 2004 |

|

|

|

|||||

| Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, recessive type | 617719 | AR | Irregularly shaped capital femoral epiphyses, short femoral neck, resembling the “Swedish key” appearance of the proximal femur, anterior wedging of vertebral bodies, small epiphyses at the knees with metaphyseal flare, advanced carpal ossification in the hands | Balasubramanian et al., 2017 | CANT1, Balasubramanian et al., 2017 | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Dyssegmental dysplasia | ||||||

|

|

|

|||||

| (a) Silverman–Handmaker (lethal) type | 224410 | AR | Anisospondyly, severe short stature, dysmorphic facies (flat face, abnormal ears, short neck, narrow thorax), joint contractures, bowed limbs, talipes equinovarus, urogenital and cardiovascular abnormalities | Aleck et al., 1987 | HSPG2, Arikawa-Hirasawaet al., 2001 | |

|

|

||||||

| (b) Rolland-Desbuquois type | 224400 | AR | ||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Severe (lethal) neonatal short limb dysplasia with multiple joint dislocations | − | AR | Phenotype resembles Desbuquois dysplasia | FAM20B, Kuroda et al., 2019 | ||

|

|

|

|||||

| Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia with joint dislocations | 143095 | − | Clubfoot, elbow joint dysplasia with subluxation and limited extension, short stature, progressive kyphosis developing in late childhood | Unger et al., 2010 | CHST3, Unger et al., 2010 | |

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; SNHL, sensorineural hearing loss.

In the present study, whole-exome sequencing of the 2 patients revealed 2 different homozygous mutations in the CANT1 gene, 1 frameshift and 1 missense. Both mutations were reported before in patients with DBQD1. The c.277_278delCT (p.Leu93ValfsTer89) found in patient 1 is located in exon 2 of the gene and was reported before in heterozygous state in 2 unrelated patients of German and French origin [Laccone et al., 2011; Houdayer et al., 2019]. Our patient showed a severe phenotype just as the previously reported German patient with compound heterozygous frameshift mutations in exon 2, p.Leu93ValfsTer89/p.Trp77LeufsTer13; moreover, the German patient died at the age of 5 months from respiratory problems. This confirms the severe effect of the frameshift mutation, which showed comparable phenotypes. Patient 1 in this study was severely affected and died early. Huber et al. [2009], who studied 9 patients, noted that while all the affected cases had similar skeletal features, those with nonsense mutations died early due to cardio-respiratory failure. Additionally, a previously reported patient and fetus from a subsequent pregnancy had frameshift mutations and were similarly severely affected in agreement with previous studies [Huber et al., 2009; Houdayer et al., 2019].

On the other hand, the c.898C>T (p.Arg300Cys) mutation identified in patient 2 is located in the last exon of the gene and was described before in 3 unrelated families, 2 from Turkey and 1 from Iran [Huber et al., 2009]. Interestingly, another missense mutation affecting the same amino acid (c.899 G>A; p.Arg300His) was also found in 2 unrelated patients by Huber et al. [2009]. The Arg300 position is located in the catalytic site of CANT1, and functional studies have shown that mutations affecting this position are likely to disrupt the electrostatic interactions in the salt bridge leading to a marked decreased enzyme activity [Huber et al., 2009].

Conclusion

In conclusion, our observation of a severe phenotype and early death in patient 1, who had a frameshift mutation in the CANT1 gene, agrees with the previous study that nonsense mutations are associated with early death. Also, the recorded hypospadias, a finding not reported before, expands the phenotypic spectrum of the disorder. We recommend molecular studies for more patients with DBQD in order to better understand the genotype-phenotype correlation.

Statement of Ethics

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki protocols and was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Research Committee of the National Research Center (approval reference No. 20066). Written informed consent was obtained from the children's parents.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

None.

Author Contributions

All the authors have contributed significantly and approved the final content of the manuscript.

Manal M. Thomas contributed to the literature search and clinical evaluation, collected references, prepared the final manuscript, and is corresponding author.

Engy A. Ashaat contributed to the clinical evaluation and manuscript writing.

Ghada A. Otaify, Samira Ismail, Sonia A. Alsaiedi, Mona Aglan, and Mona O. El Ruby contributed to the clinical evaluation.

Mona L. Essawi, Mohamed S Abdel-Hamid, and Heba A. Hassan performed molecular testing and analysis.

Samia Temtamy, the senior professor, revised the clinical and molecular data.

References

- 1.Aleck KA, Grix A, Clericuzio C, Kaplan P, Adomian GE, Lachman R, et al. Dyssegmental dysplasias: clinical, radiographic, and morphologic evidence of heterogeneity. Am J Med Genet. 1987;27:295–312. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320270208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Gazeli LI, Aziz SAA, Bakalinova D. Desbuquois syndrome in an Arab Bedouin family. Clin Genet. 1996;50:255–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1996.tb02639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Kaissi A, Klaushofer K, Grill F. Synophyrs, curly eyelashes and Pterygium colli in a girl with Desbuquois dysplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2009a;2:7873. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-7873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Kaissi A, Radler C, Klaushofer K, Grill F. Advanced ossification of the carpal bones, and monkey wrench appearance of the femora, features suggestive of a propable mild form of desbeqious dysplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2009b;2:45. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arikawa-Hirasawa E, Wilcox WR, Le AH, Silverman N, Govindraj P, Hassell JR, et al. Dyssegmental dysplasia, Silverman-Handmaker type, is caused by functional null mutations of the perlecan gene. Nat Genet. 2001;27:431–4. doi: 10.1038/86941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balasubramanian K, Li B, Krakow D, Nevarez L, Ho PJ, Ainsworth JA, et al. MED resulting from recessively inherited mutations in the gene encoding calcium-activated nucleotidase CANT1. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173:2415–21. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baynam G, Kiraly-Borri C, Goldblatt J, Dickinson JE, Jevon GP, Overkov A. A recurrence of a hydrops lethal skeletal dysplasia showing similarity to Desbuquois dysplasia and a proposed new sign: the Upsilon sign. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152:966–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bui C, Huber C, Tuysuz B, Alanay Y, Bole-Feysot C, Leroy JG, et al. XYLT1 mutations in Desbuquois dysplasia type 2. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:405–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chitayat D, Haj-Chahine S, Stalker HJ, Azouz EM, Cote A, Halal F. Hyperphalangism, facial anomalies, hallux valgus, and bronchomalacia: A new syndrome? Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:1–4. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320450103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desbuquois G, Grenier B, Michel J, Rossignol C. Chondrodystrophic dwarfism with anarchic ossification and polymalformations. Arch Franc Pediat. 1966;23:573–87. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehmke N, Caliebe A, Koenig R, Kant SG, Stark Z, Cormier-Daire V, et al. Homozygous and compound-heterozygous mutations in TGDS cause Catel-Manzke syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:763–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Everman DB, Bartels CF, Yang Y, Yanamandra N, Goodman FR, Mendoza-Londono JR, et al. The mutational spectrum of brachydactyly type C. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:291–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faden M, Al-Zahrani F, Arafah D, Alkuraya FS. Mutation of CANT1 Causes Desbuquois Dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:1157–60. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Failer BU, Braun N, Zimmermann H. Cloning, expression, and functional characterization of a Ca(2+)-dependent endoplasmic reticulum nucleoside diphosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36978–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faivre L, Le Merrer M, Al-Gazali LI, Ausems MG, Bitoun P, Bacq D, et al. Homozygosity mapping of a Desbuquois dysplasia locus to chromosome 17q25.3. J Med Genet. 2003;40:282–4. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.4.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faivre L, Cormier-Daire V, Young I, Bracq H, Finidori G, Padovani JP, et al. Long-term outcome in Desbuquois dysplasia: A follow-up in four adult patients. Am J Med Genet A. 2004a;124A:54–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faivre L, Le Merrer M, Zerres K, Hariz MB, Scheffer D, Young ID, et al. Clinical and genetic heterogeneity in Desbuquois dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2004b;128A:29–32. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faivre L, Cormier-Daire V, Eliott AM, Field F, Munnich A, Maroteaux P, et al. Desbuquois dysplasia, a reevaluation with abnormal and “normal” hands: radiographic manifestations. Am J Med Genet A. 2004c;124A:48–53. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forster K, Hooper JE, Blakemore KJ, Baschat AA, Hoover-Fong J. Prenatal diagnosis of Desbuquois dysplasia Type 1: Utilization of high-density SNP array to map homozygosity and identify the gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2019;179:2490–3. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furuichi T, Dai J, Cho T-J, Sakazume S, Ikema M, Matsui Y, et al. CANT1 mutation is also responsible for Desbuquois dysplasia, type 2 and Kim variant. J Med Genet. 2011;48:32–7. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.080226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Meinecke P, Ausems MG, Nöthen M, Albrecht B, Beemer FA, et al. Desbuquois syndrome: three further cases and review of the literature. Clin Dysmorphol. 1995;4:136–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall BD. Lethality in Desbuquois Dysplasia: Three New Cases. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:43–7. doi: 10.1007/s002470000358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houdayer C, Ziegler A, Boussion F, Blesson S, Bris C, Toutain A, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of Desbuquois dysplasia type 1 by whole exome sequencing before the occurrence of specific ultrasound signs. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;1–4:1. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1657084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber C, Oules B, Bertoli M, Chami M, Fradin M, Alanay Y, et al. Identification of CANT1 mutations in Desbuquois dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:706–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue S, Ishii A, Shirotani G, Tsutsumi M, Ohta E, Nakamura M, et al. Case of Desbuquois dysplasia type 1: Potentially lethal skeletal dysplasia. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:e26–9. doi: 10.1111/ped.12383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jéquier S, Perreault G, Maroteaux P. Desbuquois syndrome presenting with severe neonatal dwarfism, spondylo-epiphyseal dysplasia and advanced carpal bone age. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:440–2. doi: 10.1007/BF02013506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim OH, Nishimura G, Song HR, Matsui Y, Sakazume S, Yamada M, et al. A variant of Desbuquois dysplasia characterized by advanced carpal bone age, short metacarpals, and elongated phalanges: report of seven cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:875–85. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krakow D, Robertson SP, King LM, Morgan T, Sebald ET, Bertolotto C, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding filamin B disrupt vertebral segmentation, joint formation and skeletogenesis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:405–10. doi: 10.1038/ng1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuang L, Liu B, Peng R, Xi D, Gao Y. A novel homozygous variant in CANT1 causes Desbuquois dysplasia type 1 in a Chinese family and review of literatures. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2020;13:2137–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuroda Y, Murakami H, Enomoto Y, Tsurusaki Y, Takahashi K, Mitsuzuka K, et al. A novel gene (FAM20B encoding glycosaminoglycan xylosylkinase) for neonatal short limb dysplasia resembling Desbuquois dysplasia. Clin Genet. 2019;95:713–7. doi: 10.1111/cge.13530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laccone F, Schroner K, Krabichler B, Kluge B, Schwerdtfeger R, Schulze B, et al. Desbuquois dysplasia type I and fetal hydrops due to novel mutations in the CANT1 gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:1133–7. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larsen LJ, Schottstaedt ER, Bost FD. Multiple congenital dislocations associated with characteristic facial abnormality. J Pediatr. 1950;37:574–81. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(50)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Merrer M, Young ID, Stanescu V, Maroteaux P. Desbuquois syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 1991;150:793–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02026714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Laue K, Temtamy S, Aglan M, Kotan LD, Yigit G, et al. Temtamy preaxial brachydactyly syndrome is caused by loss-of-function mutations in chondroitin synthase 1, a potential target of BMP signaling. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:757–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lloyd AR, Ragosta KG, Bryke CR, Hoo JJ. Desbuquois syndrome in three sisters with significantly different lengths of survival. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1253–5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manzke H, Lehmann K, Klopocki E, Caliebe A. Catel-Manzke syndrome: two new patients and a critical review of the literature. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51:452–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mortier GR, Cohn DH, Cormier-Daire V, Hall C, Krakow D, Mundlos S, et al. Nosology and classification of genetic skeletal disorders: 2019 revision. Am J Med Genet A. 2019;179:2393–419. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishimura G, Hong HS, Kawame H, Sato S, Cai G, Ozono K. A mild variant of Desbuquois dysplasia. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158:479–83. doi: 10.1007/s004310051124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogle RF, Wilson MJ, Kozlowski K, Sillence DO. Desbuquois syndrome complicated by obstructive sleep apnoea and cervical kyphosis. Am J Med Genet. 1994;51:216–21. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320510308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shohat M, Lachman R, Gruber HE, Hsia YE, Golbus MS, Witt DR, et al. Desbuquois syndrome: clinical, radiographic, and morphologic characterization. Am J Med Genet. 1994;52:9–18. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320520104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith TM, Kirley TL. The calcium activated nucleotidases: a diverse family of soluble and membrane associated nucleotide hydrolyzing enzymes. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:327–33. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5300-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith TM, Hicks-Berger CA, Kim S, Kirley TL. Cloning, expression, and characterization of a soluble calcium-activated nucleotidase, a human enzyme belonging to a new family of extracellular nucleotidases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;406:105–15. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suter A-A, Santos-Simarro F, Toerring PM, Perez AA, Ramos-Mejia R, Heath KE, et al. Variable pulmonary manifestations in Chitayat syndrome: Six additional affected individuals. Am J Med Genet A. 2020;182:2068–76. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Temtamy SA, Aglan MS. Brachydactyly. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Temtamy SA, Meguid NA, Ismail SI, Ramzy MI. A new multiple congenital anomaly, mental retardation syndrome with preaxial brachydactyly, hyperphalangism, deafness and orodental anomalies. Clin Dysmorphol. 1998;7:249–55. doi: 10.1097/00019605-199810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unger S, Lausch E, Rossi A, Megarbane A, Sillence D, Alcausin M, et al. Phenotypic features of carbohydrate sulfotransferase 3 (CHST3) deficiency in 24 patients: congenital dislocations and vertebral changes as principal diagnostic features. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2543–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vissers LELM, Lausch E, Unger S, Campos-Xavier AB, Gilissen C, Rossi A, et al. Chondrodysplasia and abnormal joint development associated with mutations in IMPAD1, encoding the Golgi-resident nucleotide phosphatase, gPAPP. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:608–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]