Abstract

Background:

HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) 703/HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 081 is a phase 2b randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial to assess the safety and efficacy of passively infused monoclonal antibody (mAb) VRC01 in preventing HIV acquisition in heterosexual women between the ages of 18 and 50 at risk of HIV. Participants were enrolled at 20 sites in Botswana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. It is one of two Antibody Mediated Prevention (AMP) efficacy trials, with HVTN 704/HPTN 085, evaluating VRC01 for HIV prevention.

Methods:

Intense community engagement was utilized to optimize participant recruitment and retention. Participants were randomly assigned to receive intravenous (IV) VRC01 10 mg/kg, VRC01 30 mg/kg, or placebo in a 1:1:1 ratio. Infusions were given every eight weeks with a total of 10 infusions and 104 weeks of follow-up after the first infusion.

Results:

Between May 2016 and September 2018, 1924 women from sub-Saharan Africa were enrolled. The median age was 26 (IQR: 22-30) and 98.9% were Black. Sexually transmitted infection prevalence at enrollment included chlamydia (16.9%), trichomonas (7.2%), gonorrhea (5.7%) and syphilis (2.2%). External condoms (83.2%) and injectable contraceptives (61.1%) were the methods of contraception most frequently used by participants. In total, through April 3, 2020, 38,490 clinic visits were completed with a retention rate of 96% and 16,807 infusions administered with an adherence rate of 98%.

Conclusions:

This proof-of-concept, large-scale mAb study demonstrates the feasibility of conducting complex trials involving IV infusions in high-incidence populations in sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords: broadly neutralizing antibodies, AMP studies, HIV, African women, VRC01, passive immunization

Introduction

Forty years since the onset of the HIV epidemic, women and adolescent girls continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV and AIDS globally. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where over 90% of new HIV infections are acquired through unprotected heterosexual intercourse, women bear the heaviest burden of HIV/AIDS disease1. HIV-1 prevention modalities demonstrated to be effective in reducing HIV-1 risk are inadequate for African women. Interventions such as correct and consistent use of condoms and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing/treatment may require the consent of partners and may not be feasible for women unable to negotiate safe sex practices. Despite the efficacy of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in reducing sexual acquisition of HIV in men who have sex with men2,3, results in women are inconsistent4. It is not entirely clear why high adherence seems to be more important for women than men regarding oral PrEP efficacy, although there are differences in tenofovir pharmacokinetics and microbiota between the vaginal/cervical versus rectal mucosa5. As such, innovative, female-controlled HIV prevention tools are urgently needed for women in SSA.

An alternative approach to vaccination or oral or injectable PrEP for HIV prevention is passive administration of antibodies, a strategy in use for more than 100 years against diverse infectious diseases6,7. Examples include its use as post-exposure prophylaxis for rabies, measles, varicella zoster, and other infectious diseases. Recent advances in B-cell immunology and cloning techniques have led to the isolation of antibodies from HIV-infected individuals that target multiple sites of vulnerability on HIV-1 envelope (Env) and neutralize many variants, known as broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs)8. Among these bnAbs is VRC01 (VRC-HIVMAB060-00-AB), a CD4-binding site-directed human monoclonal antibody (mAb). Preclinical data demonstrated that VRC01 has high in vitro neutralization potency and wide breadth against a wide variety of HIV strains, including those most commonly occurring in SSA9. Dose ranges of VRC01 from 10 to 40 mg/kg given intravenously (IV) and 5 mg/kg subcutaneously (SC) have been assessed as well-tolerated and safe for further evaluation10,11.

VRC01 is the first mAb to proceed to late phase clinical trials for HIV prevention. The Antibody Mediated Prevention (AMP) studies, two harmonized test-of-concept phase 2b clinical trials, include the two populations in which novel biomedical interventions for HIV are needed most: heterosexual women and transgender (TG) persons and men who have sex with men (MSM). These parallel studies are assessing the safety and preventive efficacy of VRC01 among 2,700 MSM/TG persons in the Americas and Europe (HVTN 704/HPTN085, clinicaltrials.gov #NCT02716675) and 1,900 heterosexual women in sub-Saharan Africa (HVTN 703/HPTN 081, clinicaltrials.gov #NCT02568215). The cohort for HVTN 703/HPTN 081 was selected based on regional epidemiological data showing a disproportionate HIV incidence among sub-Saharan African women12,13. Here, we describe the study design, recruitment and retention of participants in HVTN 703/HPTN 081 and report the baseline characteristics of women who enrolled in the trial. A concurrent description of HVTN 704/HPTN085 is reported in a separate manuscript.

METHODS

Study design

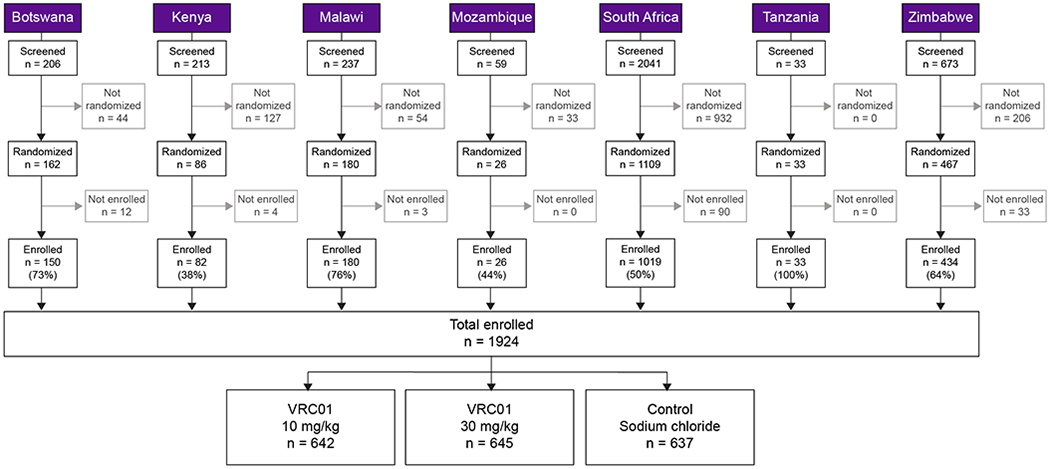

In this multicenter, randomized, controlled, double-blind, 3-arm trial, volunteers were randomly assigned to receive IV infusions of 10 mg/kg of VRC01, 30 mg/kg of VRC01, or placebo (Sodium Chloride for Injection 0.9%) in a 1:1:1 ratio to approximately 643 women per arm (Figure 1 and Supp Table 1). Infusions of study product were given every eight weeks with a total 10 infusions for a period of 104 weeks after the first infusion. Week 80 was the last study visit to evaluate efficacy and Week 104 was the final study visit to evaluate safety and tolerability.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Participants had safety blood draws and urine pregnancy testing before each infusion; testing for syphilis, chlamydia, trichomonas, and gonorrhea was performed at baseline and then approximately every 6 months. Volunteers completed questionnaires about sexual behavior and general health every 4-8 weeks.

Study objectives

The primary objectives were to evaluate the safety and tolerability of VRC01 administered by IV infusion and to determine its efficacy in preventing HIV-1 infection. Secondary objectives include identifying markers of VRC01 treatment that correlate with the level and antigenic specificity of protection against HIV-1 infection and providing insight into the mechanistic correlates of protection.

Screening and enrollment

The study was conducted at 20 clinical research sites (CRS) in Botswana (1 CRS), Kenya (1 CRS), Malawi (2 CRS), Mozambique (1 CRS), South Africa (11 CRS) Tanzania (1 CRS) and Zimbabwe (3 CRS). The CRSs included rural and urban sites, sites affiliated with major academic institutions and medical centers and freestanding clinics, large and small sites, and sites with and without ancillary clinical and social services. The population included healthy heterosexual women, 18 to 50 years old, who, in the 6 months prior to randomization, had engaged in vaginal and/or anal intercourse with a male partner. A participant was considered enrolled after receiving the first dose.

HIV and pregnancy prevention package

All participants were offered a comprehensive HIV prevention package comprised of behavioral, biomedical and structural interventions including provision of internal and external condoms, HIV/STI risk reduction counselling and testing for participant and partner/s, and free STI treatment for participant and partner/s on site, or through referral per local standard of care. Partners were offered referrals for voluntary medical male circumcision and in HIV sero-discordant couples, HIV-infected male partners were referred for antiretroviral (ARV) therapy (ART) as indicated. Risk reduction counselling was provided by trained counsellors at all study visits and included continued dialogue about PrEP (oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [TDF]/emtricitabine [FTC], Truvada®) and in-study provision of oral PrEP or referral to community programs or providers of PrEP per local and regional guidelines. As new data emerged and standards of care for HIV prevention evolved, the content of risk reduction counselling and referrals for biomedical interventions were updated to conform to current best practices for the populations enrolled in the trial. ARV-based PrEP use was assessed through serum/plasma drug level and self-reports.

Contraception was offered on site or through referral, according to local standards of care. Participants who become pregnant stopped receiving infusions, but remaining visits were completed unless medically contraindicated or the participant was unwilling. Product resumption eligibility post-pregnancy was determined by the Protocol Safety Review Team.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards (IRB), ethics review committees, drug regulatory authorities and other in-country regulators at all sites prior to implementation of the study. All participants provided written informed consent in the language of their choice before any study procedures were conducted. Sites utilized several simplified IRB-approved informed consent supplementary materials, including an informed consent video, animated videos providing background on mAbs for HIV prevention, graphic flipcharts, and factsheets to aid comprehension of this novel proof-of-concept study. The informed consent was re-visited at each scheduled visit and when indicated. All study procedures were conducted per international, regional and local ethical standards by experienced personnel with good clinical practice, human subject protection, and other appropriate certification.

Laboratory procedures

HIV testing and diagnosis

HIV testing was conducted every four weeks through Week 80 and at any time following report of possible exposure to HIV by a participant. Beyond Week 80, HIV testing was conducted every eight weeks. The date of HIV diagnosis was defined as the specimen collection date of the first sample that led to a positive result by the in-study HIV diagnostic algorithm. Before informing a participant that they had acquired HIV at or after enrollment, all HIV test results were reviewed by blinded, independent endpoint adjudicators. Participants who acquired HIV remained in the study for follow-up but received no further infusions.

Dried blood spot sampling for tenofovir

ARV testing was performed on dried blood spot (DBS) samples to measure the level of tenofovir-diphosphate (a metabolite of tenofovir) in red blood cells. This test utilizes a DBS as the sample source and analyzes for tenofovir diphosphate by liquid chromatography and tandem mass-spectroscopy, as previously described14. Tenofovir diphosphate has a long half-life; high amounts of the metabolite in DBS correspond with consistent dosing of Truvada (FTC/TDF), while low amounts correspond with inconsistent dosing2. Samples were collected and stored on regularly scheduled calendar days throughout the study and testing was performed periodically on batched samples. This allowed prospective monitoring of FTC/TDF use during the trial to inform assessments of the potential impact of FTC/TDF use on prevention efficacy of the study product.

Feasibility and safety monitoring

After the first 120 enrolled participants combined from both AMP trials completed the Week 32 visit, an interim feasibility analysis was conducted to evaluate whether an adequate percentage of participants attended study visits and received infusions per the protocol. Trial retention, as defined below, by the Week 32 visit, pooled over the three study groups, had to be greater than 80% for the trials to continue as planned. This milestone was achieved and accrual and retention rates and data integrity were monitored throughout the study.

Team clinical safety specialists and regional medical liaisons monitored adverse events (AEs) blinded by treatment assignment daily. The full Protocol Safety Review Team (PSRT) periodically reviewed AEs and reactogenicity events (REs) blinded by treatment assignment. Biannual and ad hoc review of unblinded feasibility, data management and safety data were conducted by the DSMB.

Statistical considerations

The trial is designed with 90% power to detect prevention efficacy (PE) of 60% (rejecting the null hypothesis of 0% PE) comparing the pooled VRC01 and control groups, based on reasonable assumptions of a background HIV-1 incidence of 5.5%, annual dropout rate of 10% and infusions taking place every eight weeks. The sample size calculations assume 30 months of enrolment and 80 weeks of total follow-up per participant for observing the primary HIV-1 infection endpoint.

Descriptive statistics were reported for baseline participant characteristics. An inverse sampling probability estimator was used to estimate the percent person-years with detectable and effective PrEP uptake. Confidence intervals for the quantitative assessment of tenofovir-diphosphate levels in DBS were calculated using a bootstrap method to account for repeated measures across study participants.

Study dropout was defined as 1) having terminated early from the study, or 2) not having a specimen collected for a least 20 weeks prior to the Week 104 visit. The dropout date was defined as the earliest of 1) the expected date of the first missed visit prior to study termination, 2) the study termination date, or 3) the date 20 weeks from the last collected specimen date. For the purpose of assessing dropout incidence, if a participant acquired HIV, follow-up time was censored at their diagnosis date. If a participant did not acquire HIV and did not drop out of the study, then follow-up time was censored at their last specimen collection date. Incidence rates of events are calculated as the number of events per 100 person-years of follow-up. For each of the AMP trials, the primary efficacy analysis in a future manuscript will assess PE defined as one minus the ratio of the cumulative incidence of the primary endpoint of HIV-1 infection at the Week 80 visit in the two mAb groups pooled versus the control group (2:1 randomization active: control).

Community engagement

Prior to study implementation, the HVTN 703/HPTN 081 protocol team held two stakeholders’ consultative meetings that brought together governmental and nongovernmental organizations, public health advocates, IRB members, research staff, community officials and traditional and/or spiritual healers who were committed to identifying HIV prevention strategies that address the diverse needs of research communities in sub-Saharan Africa. The consultations provided a platform for stakeholder discussions related to the implementation of the AMP trial in their communities in order to improve study implementation and develop strategies for ongoing engagement. Each site developed a Community Engagement Work Plan, which was reviewed and approved by the Community Working Group (CWG) and Community Advisory Boards (CABs) and implemented 4-6 months before study initiation15. Sites regularly updated the CWG on recruitment, adherence and retention, discussing challenges and mitigatory strategies and sharing best practices.

Retention

Retention is defined as the number of participants who completed the visit divided by the number of participants expected for the visit plus participants who completed the visit when not expected. Visits were considered “completed” based on submission of the Infusion or Specimen Collection case report form (CRF). Visits were considered “expected” when the visit window was closed on or before the report date, subject to the additional conditions: the 5 day and 4 week follow-up visits were not expected if the base (i.e., infusion) visit was missed or if study product was not administered at the base visit; visits were not expected after a visit where study product was permanently discontinued; and visits in the infusion schedule were not expected following an HIV diagnosis. Visit expectation is based on the product discontinuation visit, where applicable, and based on the HIV diagnosis date otherwise. Visits where the target date occurs after the termination date are not considered “expected” and are not included in the denominator.

Adherence

Adherence is defined as the number of participants who received an infusion divided by the number of participants who completed an infusion visit.

RESULTS

Study schema, participant accrual and enrollment

Between May 2016 and September 2018, a total of 3,462 heterosexual women were screened for study eligibility and 1,924 were enrolled across 20 CRS in seven sub-Saharan African countries, with a screen-to-enrollment ratio of 1.8:1 (Figure 1). Two participants were inappropriately enrolled; one was determined to be under 18 years of age, and one was determined to be co-enrolled in another ongoing interventional HIV prevention trial. The study took approximately 28 months to accrue. South Africa enrolled 1,019 (53.2%), Zimbabwe 434 (22.3%), Malawi 180 (9.4%), Botswana 150 (7.8%), Kenya 82 (4.3%), Tanzania 33 (1.7%) and Mozambique 26 (1.3%) women. Out of the 1,538 women screened who were ineligible, the most common reasons for not enrolling included abnormal physical exam findings (647, 42.1%), HIV test results (189, 12.3%) and site assessment of participant’s availability (159, 10.3%) (Supp Tables 2&3).

Demographics and baseline risk factors

Figure 1 provides the number of participants who were screened, randomized and enrolled for all countries. Most women enrolled were Black (1,902, 98.9%); the remaining minority were Asian, Multiracial, or Other (Table 1). Participants enrolled per protocol were 18 to 49 years old, with a median age of 26 years (interquartile range [IQR] 22–30) (Table 1). In total, 49.9% of women were ≤25 years of age, a well-documented risk factor for HIV acquisition16.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline risk factors.

| n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botswana | Kenya | Malawi | Mozambique | South Africa | Tanzania | Zimbabwe | Total | |

| Total enrolled | 150 | 82 | 180 | 26 | 1019 | 33 | 434 | 1924 |

| Age | ||||||||

| <18 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1%) |

| 18-21 | 24 (16.0%) | 17 (20.7%) | 45 (25.0%) | 12 (46.2%) | 248 (24.3%) | 6 (18.2%) | 37 (8.5%) | 389 (20.2%) |

| 22-25 | 46 (30.7%) | 33 (40.2%) | 33 (18.3%) | 6 (23.1%) | 324 (31.8%) | 6 (18.2%) | 111 (25.6%) | 559 (29.1%) |

| 26-30 | 46 (30.7%) | 25 (30.5%) | 40 (22.2%) | 6 (23.1%) | 256 (25.1%) | 12 (36.4%) | 155 (35.7%) | 540 (28.1%) |

| 31-40 | 33 (22.0%) | 7 (8.5%) | 62 (34.4%) | 2 (7.7%) | 185 (18.2%) | 8 (24.2%) | 129 (29.7%) | 426 (22.1%) |

| 41-50 | 1 (0.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (0.5%) | 1 (3.0%) | 2 (0.5%) | 9 (0.5%) |

| Age median (IQR) | 26 (22-30) | 24 (22-27) | 27 (22-32) | 23 (19-26) | 24 (21-29) | 27 (24-36) | 27 (24-32) | 26 (22-30) |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black | 150 (100%) | 150 (100%) | 150 (100%) | 24 (92.3%) | 999 (98.0%) | 33 (100%) | 434 (100%) | 1902 (98.9%) |

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (0.5%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | 11 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (0.6%) |

| Multiracial | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Risk factors | ||||||||

| Number of sex partners in last 60 days | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.7%) | 1 (3.8%) | 18 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.2%) | 27 (1.4%) |

| 1 | 61 (40.7%) | 3 (3.7%) | 92 (51.1%) | 16 (61.5%) | 428 (42.0%) | 5 (15.2%) | 226 (52.1%) | 831 (43.2%) |

| 2 | 56 (37.3%) | 10 (12.2%) | 41 (22.8%) | 8 (30.8%) | 316 (31.0%) | 5 (15.2%) | 67 (15.4%) | 503 (26.1%) |

| 3-4 | 24 (16.0) | 19 (23.2%) | 14 (7.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 120 (11.8%) | 10 (30.3%) | 49 (11.3%) | 236 (12.3%) |

| ≥5 | 0 (0.0%) | 46 (56.1%) | 28 (15.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 82 (8.0%) | 7 (21.2%) | 69 (15.9%) | 232 (12.1%) |

| Median (min, max) | 2 (1, 4) | 6 (1, 60) | 1 (0, 200) | 1 (0, 2) | 2 (0, 269) | 3 (1, 21) | 1 (0, 300) | 2 (0, 300) |

| Condom use | ||||||||

| Always | 26 (17.3%) | 22 (26.8%) | 33 (18.3%) | 7 (26.9%) | 188 (18.4%) | 1 (3.0%) | 101 (23.3%) | 378 (19.6%) |

| Sometimes | 94 (62.7%) | 47 (57.3%) | 68 (37.8%) | 16 (61.5%) | 602 (59.1%) | 16 (48.5%) | 228 (52.5%) | 1071 (55.7%) |

| Never | 19 (12.7%) | 8 (9.8%) | 73 (40.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 143 (14.0%) | 10 (30.3%) | 70 (16.1%) | 323 (16.8%) |

| Missing | 11 (7.3%) | 5 (6.1%) | 6 (3.3%) | 3 (11.5%) | 86 (8.4%) | 6 (18.2%) | 35 (8.1) | 152 (7.9%) |

| Unprotected sex with HIV+ partner | ||||||||

| No | 104 (69.3%) | 32 (39.0%) | 131 (72.8%) | 19 (73.1%) | 700 (68.7%) | 14 (42.4%) | 277 (63.8%) | 1277 (66.4%) |

| Don’t know | 13 (8.7%) | 24 (29.3%) | 21 (11.7%) | 2 (7.7%) | 87 (8.5%) | 10 (30.3%) | 33 (7.6%) | 190 (9.9%) |

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (3.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 6 (0.3%) |

| Missing | 33 (22.0%) | 25 (30.5%) | 27 (15.0%) | 5 (19.2%) | 230 (22.6%) | 8 (24.2%) | 123 (28.3%) | 451 (23.4%) |

| Unprotected vaginal sex | ||||||||

| No | 15 (10%) | 8 (10%) | 18 (10%) | 3 (12%) | 131 (13%) | 1 (3%) | 56 (13%) | 232 (12%) |

| Yes | 123 (82%) | 69 (84%) | 152 (84%) | 22 (85%) | 709 (70%) | 26 (79%) | 344 (79%) | 1445 (75%) |

| Missing | 12 (8%) | 5 (6%) | 10 (6%) | 1 (4%) | 179 (18%) | 6 (18%) | 34 (8%) | 247 (13%) |

| Exchange of sex for money/gifts | ||||||||

| No | 122 (81.3%) | 25 (30.5%) | 127 (70.6%) | 24 (92.3%) | 788 (77.3%) | 13 (39.4%) | 350 (80.6%) | 1449 (75.3%) |

| Yes | 18 (12.0%) | 50 (61.0%) | 46 (25.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 137 (13.4%) | 13 (39.4%) | 58 (13.4%) | 322 (16.7%) |

| Missing | 10 (6.7%) | 7 (8.5%) | 7 (3.9%) | 2 (7.7%) | 94 (9.2%) | 7 (21.2%) | 26 (6.0%) | 153 (8.0%) |

This cohort of women had engaged in vaginal and/or anal intercourse with a male partner in the 6 months prior to randomization. The median number of sexual partners in the 60 days preceding enrollment was 2 (range 0-300) (Table 1). Reports of inconsistent condom use were high; over half of participants (55.7%) reported frequency of condom use as “sometimes” and 16.8% as “never.” Additionally, 75% reported unprotected vaginal sex and almost 17% of women reported transactional sex at baseline.

Of the 1,924 women who enrolled in the trial, 26.4% (n=508) had a bacterial STI at baseline (Table 2). The most common STI, Chlamydia trachomatis, was reported in 326 (16.9%) participants, followed by Trichomonas vaginalis in 139 (7.2%), Neisseria gonorrhoeae in 109 (5.7%) and Treponema pallidum (syphilis) in 43 (2.2%) participants. STI prevalence varied by site, with the highest rates of any STI observed in Maputo, Mozambique (46.2%) and Cape Town, South Africa (42.9%). The burden of STIs remained high through Week 104; with 45.5% (n=875) of participants reporting any bacterial STI.

Table 2.

STI prevalence (%) by country.

| Botswana | Kenya | Malawi | Mozambique | South Africa | Tanzania | Zimbabwe | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | 20.7 | 14.6 | 7.2 | 19.2 | 20.4 | 15.2 | 12.0 | 16.9 |

| GC | 5.3 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 9.1 | 5.8 | 5.7 |

| Syphilis | 0.7 | 1.2 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 6.1 | 3.5 | 2.2 |

| Trichomonas | 0.0 | 2.4 | 10.6 | 23.1 | 5.6 | 9.1 | 12.0 | 7.2 |

| Any STI | 24.7 | 22.0 | 23.9 | 46.2 | 27.6 | 33.3 | 24.4 | 26.4 |

CT = Chlamydia trachomatis. GC = Gonococcal (Neisseria gonorrhea).

Pregnancy prevention and rate

The most common method of birth control at enrollment included external condoms (83.2%). This was followed by injectable contraceptives (61.1%), implants (25.4%), oral contraceptive (10.0%), intrauterine device (2.5%), female condoms (2.1%), and sterilization (1.1%). Less than 1% of participants reported the patch, natural methods (both 0.1%) and other methods (0.2%).

Over the course of the trial, 131 (5.08%) women became pregnant for a total of 2,816.7 person-years or rate of 5.08% (95% CI: 4.28, 5.98) (Table 3). Twelve participants became pregnant more than once during the trial. The incidence of pregnancy was highest in women between the ages of 18 and 30. When stratified by whether the participant was provided contraception at the CRS, the pregnancy rate for those who received contraception was 4.78% (95% CI: 3.99, 5.68) compared to 10.91% (95% CI: 6.11, 18.00) for those who did not.

Table 3.

Pregnancy incidence by age and contraception provision.

| # Participants | # Pregnant participants | # Pregnancies | Person-years | Rate | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| <18 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.00 | (0.00,1604) |

| 18 - 20 | 259 | 22 | 23 | 370.2 | 6.21 | (3.94,9.32) |

| 21 - 30 | 1235 | 90 | 100 | 1810.0 | 5.52 | (4.50,6.72) |

| 31 - 40 | 420 | 19 | 20 | 621.2 | 3.22 | (1.97,4.97) |

| 41 - 50 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 15.1 | 0.00 | (0.00,24.44) |

| Contraception provision | ||||||

| Yes | 1828 | 118 | 128 | 2679.3 | 4.78 | (3.99,5.68) |

| No | 96 | 13 | 15 | 137.5 | 10.91 | (6.11,18.00) |

| Total | 1924 | 131 | 143 | 2816.7 | 5.08 | (4.28,5.98) |

Cutoff date for pregnancy calculations was April 3, 2020.

PrEP Use

Ten (0.5%) participants self-reported PrEP use at enrollment. PrEP use was measured by DBS specimens. Fifty-four of 1,860 DBS samples collected through 14 June 2019 (from 1106 participants) had a detectable concentration above the lower limit of quantitation. However, only two of these samples had a concentration above the threshold of effective PrEP use (1,000 fmol/punch). Based on study data, PrEP use did not increase significantly over time; with samples collected through 16 July 2020, showing six samples from six participants with levels consistent with effective PrEP use collected over 3,300 person-years of follow-up.

Retention and adherence

All 1,924 women enrolled were included in the retention and adherence analysis. The total number of expected visits, including 10 infusion and 14 follow-up visits, for all sites combined was 40,320. Of those, 38,490 or 96% were completed (Table 4). On a per-site basis, retention ranged from 92% to 99%. As of April 3, 2020, the annual dropout rate was 6.3% per year, below the 10% annual dropout rate included in the trial’s initial design assumptions.

Table 4.

Retention and adherence by infusion number.

| Infusion number | Retention | Adherence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1924/1924 (100%) | 1924/1924 (100%) |

| 2 | 1841/1889 (98%) | 1824/1841 (99%) |

| 3 | 1788/1852 (97%) | 1769/1788 (99%) |

| 4 | 1764/1823 (97%) | 1734/1764 (98%) |

| 5 | 1719/1789 (96%) | 1676/1719 (98%) |

| 6 | 1677/1765 (95%) | 1631/1677 (97%) |

| 7 | 1648/1747 (94%) | 1594/1648 (97%) |

| 8 | 1626/1718 (95%) | 1576/1626 (97%) |

| 9 | 1615/1696 (95%) | 1559/1615 (97%) |

| 10 | 1581/1657 (95%) | 1520/1581 (96%) |

| Total | 38490/40320* (96%) | 14883/15259 (98%) |

Total retention includes 10 infusion and 14 follow-up visits.

A total of 17,183 infusions were planned. For all sites combined, the adherence rate was 98% (16,807) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This paper describes the successful enrollment of women in sub-Saharan Africa in the HVTN 703/HPTN 081 AMP study, the first large-scale use of a mAb for prevention of HIV-1. Study sites were able to enroll and retain over 1,900 women at high risk of HIV-1 over the 104-week study period, with a remarkable retention rate of over 90% and adherence to infusions of 98%. This retention was markedly higher than recorded in studies of oral PrEP conducted in similar populations in SSA16,17. Robust, on-going community engagement strategies including face-to-face community outreach meetings and stakeholder consultation led to the phenomenal success in enrollment and retention15.

The prevalence of treatable STIs was high, as one in four women had at least one STI at enrollment, reflecting the high-incidence profile of this population. STIs not only can lead to severe complications and long-term sequelae, including pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and perinatal complications in infants, but are an important cofactor of increased risk of HIV acquisition and transmission18,19. The prevention, screening and control of STIs should be an integral part of comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services and the HIV prevention package.

PrEP uptake and adherence was exceedingly low and mirrored the national status in the different host countries. A key principle the study team heard from SSA collaborators was that PrEP access should be comparable for both study and community members, with no “undue inducement” to trial participation. South Africa and Kenya were the first two participating countries to approve the use of fixed-dose combination TDF/FTC as an HIV prevention tool, followed closely by Zimbabwe. As plans for rollout in these three countries were developed, trial participants were linked to these programs as closely as possible, with any access gaps filled through study-provided oral PrEP. Over the course of the trial, national policies continued to evolve in each host country around the use of PrEP as an HIV prevention tool. As such, risk reduction counselling and PrEP messaging were adapted in line with in-country guidelines.

Women in SSA continue to have relatively high fertility rates, averaging 4.7 births per woman20. In South Africa, the rates of unintended pregnancy demonstrate high levels of unmet need, especially among young black women21. High pregnancy rates are one of the challenges of conducting HIV prevention trials in sub-Saharan Africa22. Despite on-going pregnancy prevention counselling at each visit, at the time of analysis, pregnancy rates were high in this cohort, particularly at sites where contraception was not directly provided. These observations illustrate that in addition to frequent ongoing pregnancy prevention counselling, provision of contraception on-site may be a beneficial approach in reducing pregnancy risk among women in HIV prevention trials. In addition, where on-site provision of contraceptives cannot be achieved, participants should be assisted to effortlessly access contraception in public health facilities.

In addition to providing risk reduction counseling to all participants, we prioritized community engagement to educate and motivate women about participating in the AMP trial. These robust community engagement activities, beginning with stakeholder consultations before the trial opened, were instrumental in allaying myths and misconceptions in African research communities, resulting in timely recruitment and excellent retention. Retention of clinical trial participants and adherence to study interventions is a global challenge. HVTN 703/HPTN 081 has maintained exceptional retention and adherence to infusion visits with over 17,000 infusions administered in this cohort. Annual drop-out rates remained below the pre-specified acceptable rates of 10%. Excellent recruitment and adherence resulted from robust community engagement efforts and on-going site-specific participant engagement activities15. Participants received IRB-approved tokens of appreciation for achieving certain study milestones, for example after completing all the required 10 infusions. Some sites held regular retention meetings during which participants received retention gifts to encourage retention. Lengthy visits are consistently cited as a top reason for participant dissatisfaction in previous studies and can lead to poor retention and adherence. The protocol implemented Rapid Processing Improvement (RPI) strategies for participants, making the visits extremely efficient and reducing time spent at clinic. Additionally, the remarkable safety profile of the product potentially contributed to the exceptional adherence and retention. Both AMP trials are scheduled to complete all follow-up in early 2021 and the efficacy results will be reported in future publications.

In conclusion, HVTN 703/HPTN 081 successfully enrolled and retained HIV-1 seronegative African women at risk of HIV-1 acquisition, a population that is readily identifiable for targeted implementation and delivery of this intervention. The retention and adherence to this IV infusion schedule is a marked success. In addition, the 3-arm design of the AMP trials, evaluating a higher and a lower dose against placebo, has the advantages of allowing inferences about causal effects of the mAb, resolution of correlates of protection, and determination of dose-dependent prevention efficacy. HVTN 703/HPTN 081 paves the way for future mAb studies for HIV prevention in this population.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. Schedule of VRC01 antibody infusions.

Supplementary Table 2. Reasons for screened participants not enrolling.

Supplementary Table 3. Reasons for randomized participants not enrolling.

Acknowledgements

This trial was conducted by the HIV Vaccine Trials Network. We gratefully acknowledge the support and contribution of our colleagues and staff on the protocol team and at the sites, and are especially grateful for the participation of the HVTN 703/HPTN 081 study participants. A full list of site staff can be found in Supplemental Materials. For their roles in protocol development and study implementation, we thank Mark Barnes, Ken Mayer, LaRon Nelson, Manuel Villarán, and Sinead Delany-Moretlwe. We also thank our colleagues Katherine Shin, Keitumetse Diphoko, and Robert De La Grecca for their contributions to the original protocol and Nicole Na for contributing to this manuscript. We are grateful to Karan Shah and Bharathi Lakshminarayanan for their assistance in statistical programming. We thank our many colleagues at VRC/NIAID who contributed to the clinical development and manufacturing of VRC01 for this trial.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) U.S. Public Health Service Grants UM1 AI068614 [LOC: HIV Vaccine Trials Network], UM1 AI068635 [HVTN SDMC FHCRC], UM1 AI068618 [HVTN Laboratory Center FHCRC], and UM1AI068619 (HPTN Leadership and Operations Center). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Sources of funding:

NIAID Award AI068614 for the HVTN Leadership and Operations Center (LOC)

NIAID Award AI068635 for the HVTN Statistical and Data Management Center (SDMC)

NIAID Award AI068618 for the HVTN Laboratory Center (LC)

NIAID Award AI068619 HPTN Leadership and Operations Center

References

- 1.UNAIDS. UNAIDS Data 2019. Geneva, Switzerland: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janes H, Corey L, Ramjee G, et al. Weighing the Evidence of Efficacy of Oral PrEP for HIV Prevention in Women in Southern Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2018;34(8):645–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson KB, Prince HA, Kraft E, et al. Penetration of tenofovir and emtricitabine in mucosal tissues: implications for prevention of HIV-1 transmission. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(112):112re114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winokur PL, Stapleton JT. Immunoglobulin prophylaxis for hepatitis A. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14(2):580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Advisory Committee on Immunization P, Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-7):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen MS, Corey L. Broadly neutralizing antibodies to prevent HIV-1. Science. 2017;358(6359):46–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu X, Wang C, O’Dell S, et al. Selection pressure on HIV-1 envelope by broadly neutralizing antibodies to the conserved CD4-binding site. Journal of virology. 2012;86(10):5844–5856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ledgerwood JE, Coates EE, Yamshchikov G, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and neutralization of the broadly neutralizing HIV-1 human monoclonal antibody VRC01 in healthy adults. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;182(3):289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer KH, Seaton KE, Huang Y, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and immunological activities of multiple intravenous or subcutaneous doses of an anti-HIV monoclonal antibody, VRC01, administered to HIV-uninfected adults: Results of a phase 1 randomized trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11):e1002435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNAIDS. AIDSinfo. https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- 13.We’ve got the power — Women, adolescent girls and the HIV response [press release]. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, March5, 20202020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Zheng JH, Rower JE, et al. Tenofovir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots for determining recent and cumulative drug exposure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(2):384–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broder GB, Lucas JP, Davis J, et al. Standardized Metrics Can Reveal Region-Specific Opportunities in Community Engagement to Aid Recruitment in HIV Prevention Trials. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0239276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372(6):509–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(5):411–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Global Burden of Disease Study C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes K Sexually transmitted diseases. 4th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Bank. Fertility rate, total (births per woman) - Sub-Saharan Africa. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=ZG. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- 21.Mbelle N, Mabaso M, Setswe G, Sifunda S. Predictors of unplanned pregnancies among female students at South African Technical and Vocational Education and Training colleges: Findings from the 2014 Higher Education and Training HIV and AIDS survey. S Afr Med J. 2018;108(6):511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagakos SW, Gable AR. Challenges to HIV prevention--seeking effective measures in the absence of a vaccine. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358(15):1543–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Schedule of VRC01 antibody infusions.

Supplementary Table 2. Reasons for screened participants not enrolling.

Supplementary Table 3. Reasons for randomized participants not enrolling.