To the Editor:

The stepwise approach to the pharmacologic treatment of asthma is a core foundation of asthma guidelines (1). Through this approach, treatment intensity is increased in discrete steps to obtain symptom control and reduce exacerbation risk and is decreased after a period of prolonged control. The stepwise approach is usually shown by an algorithm, as illustrated in the 2020 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) strategy update (Figure 1). Here, we review the 2020 GINA stepwise algorithm and suggest alternative evidence-based algorithms that address potential problems with the currently recommended approach.

Figure 1.

Personalized management for adults and adolescents to control symptoms and minimize future risk. The 2020 Global Initiative for Asthma algorithm. Reprinted by permission from Reference 1. BDP = beclomethasone dipropionate; HDM = house dust mite; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β2-agonist; LTRA = leukotriene receptor antagonist; OCS = oral corticosteroids; SABA = short-acting β2-agonist; SLIT = sublingual immunotherapy.

Currently at each step, the GINA algorithm aligns treatment recommendations based on inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/formoterol reliever therapy with those of the traditional short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) reliever therapy. This assumes that the efficacy of treatment incorporating ICS/formoterol reliever therapy at each step aligns more closely with the corresponding alternative treatment incorporating a SABA reliever at the same step, rather than at adjacent higher or lower steps, which is not the case (2–4). This is illustrated by the recent systematic review and network meta-analysis that reported that the relative risk of a severe exacerbation with low-dose ICS/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy at GINA step 3 compared with low-dose ICS/long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) plus SABA therapy (GINA step 3), medium-dose ICS/LABA plus SABA (GINA step 4), and high-dose ICS/LABA plus SABA (GINA step 5) was 0.55 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.47–0.64), 0.71 (95% CI, 0.56–0.91), and 0.78 (95% CI, 0.51–1.21) respectively (3). Thus, low-dose ICS/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy at GINA step 3 aligns most closely in terms of efficacy with high-dose ICS/LABA plus SABA therapy at GINA step 5 and then progressively aligns to a lesser extent with medium-dose ICS/LABA plus SABA therapy at GINA step 4 and then with low-dose ICS/LABA plus SABA therapy at GINA step 3. This ranking of efficacy is thus discordant with the current algorithm. This structural problem could be resolved by separating the instructions for the stepwise approach incorporating ICS/formoterol reliever therapy from those incorporating SABA reliever therapy by using two separate algorithms, as was undertaken in the New Zealand asthma guidelines in 2020 (5). This avoids the problem of step misalignment and the potential inadvertent mixing of the two approaches. It is possible to simplify the algorithms further by not including other less effective “second-line” alternative treatments.

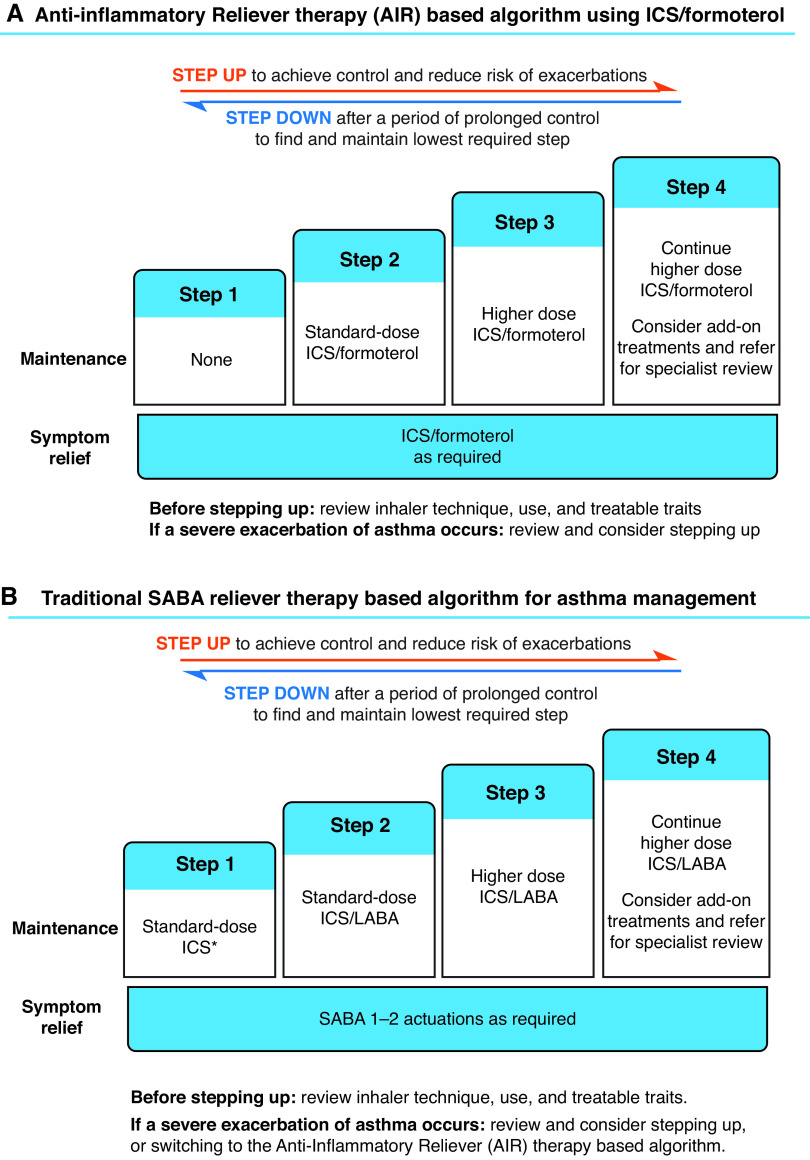

The antiinflammatory reliever–based algorithm using ICS/formoterol can be based on four steps, the first step being use of ICS/formoterol as the sole reliever therapy (Figure 2A), which is currently proposed at GINA steps 1 and 2 (Figure 1). Steps 2 and 3/4 are use of “standard”-dose (low-dose) and “higher”-dose (medium-dose) ICS/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy, corresponding to the current GINA steps 3 and 4/5; the add-on therapies in severe asthma are introduced at step 4 (currently GINA step 5) (Figures 1 and 2A). The antiinflammatory reliever–based algorithm can be considered the preferred strategy, as it outperforms the traditional SABA reliever–based algorithm at each step in reducing the risk of severe exacerbations (2–4).

Figure 2.

The prototypic algorithms based on (A) antiinflammatory reliever therapy and (B) SABA reliever therapy. *Or standard-dose ICS taken whenever SABA is taken. AIR = antiinflammatory reliever therapy; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β2-agonist; SABA = short-acting β2-agonist.

The traditional SABA reliever–based algorithm can also comprise four steps (Figure 2B). With the recommendation that a SABA should no longer be used as the sole reliever therapy without an ICS (1), regularly scheduled maintenance ICS therapy together with SABA reliever therapy (currently one of the preferred treatment options at GINA step 2) is recommended for step 1. At steps 2 and 3/4, “standard”-dose (low-dose) and “higher”-dose (medium- or high-dose) maintenance ICS/LABA and SABA reliever therapies are recommended, corresponding to the current GINA steps 3 and 4/5: the add-on therapies in severe asthma are introduced at step 4 (previously GINA step 5). Although the option to prescribe either medium- or high-dose ICS/LABA therapy is provided, including them at the same step is based on the similar efficacy yet greater risk of adverse systemic effects with the high-dose ICS regimen (6) and the known reluctance to step down from high doses of ICS/LABA therapy (7), which may contribute to the common prescription of inappropriately excessive doses of ICSs (6).

One of the main uncertainties with both algorithms is the paucity of evidence on which to base the thresholds for changing treatment steps, a limitation that is shared with the current GINA algorithm (8). Current evidence suggests that the presence of biomarkers of type 2 airway inflammation is the most effective way to identify patients likely to respond to higher-intensity ICS treatment (9). In their absence, a reasonable approach is to base changes in treatment on two key factors, namely whether there has been a recent severe exacerbation and the frequency of reliever use. A severe exacerbation could prompt medical review for consideration of an increase in the treatment step, as such an event is associated with an increased risk of future severe exacerbations (10). Transition points based on high SABA use could be used for the traditional SABA reliever–based algorithm, as increasing use is a marker of poor asthma control and exacerbation risk (10, 11). However, there is a different relationship with increasing ICS/formoterol use, in which higher use reduces the level of risk of an exacerbation, compared with SABA use (11). This could be addressed by guiding the patient to assign the higher reliever use to a higher regularly scheduled maintenance dose for the period of increased use. For both algorithms, “treatable traits” would be identified and managed in their own right (9).

In conclusion, the scientific evidence that ICS/formoterol reliever therapy is more effective at reducing severe exacerbation risk than SABA reliever therapy, either alone or when received together with maintenance ICS/formoterol therapy, has led to a paradigm shift in asthma management, which has the potential to cause confusion, as it replaces the long-established clinical practice that all patients should receive SABA reliever therapy. The potential confusion is evident from the current stepwise treatment algorithm’s complexity, due to the attempt to represent all treatment options, and the inclusion of two reliever therapy regimens with differing efficacy in a single figure (Figure 1). These structural problems can be addressed by separating the current algorithm into two separate algorithms based on antiinflammatory ICS/formoterol and SABA reliever therapy strategies. The priority now is to investigate the practical implementation of the algorithms to better inform their use in clinical practice.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the critique of the stepwise approach to asthma treatment and the development of the prototypic algorithms. C.K. created Figure 2, R.B. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to the manuscript’s revision.

The Medical Research Institute of New Zealand receives Independent Research Organisation funding from the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202101-0224LE on March 30, 2021

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Asthma. Fontana, WI: Global Initiative for Asthma; 2020. www.ginasthma.org [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sobieraj DM, Weeda ER, Nguyen E, Coleman CI, White CM, Lazarus SC, et al. Association of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β-agonists as controller and quick relief therapy with exacerbations and symptom control in persistent asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319:1485–1496. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rogliani P, Ritondo BL, Ora J, Cazzola M, Calzetta L. SMART and as-needed therapies in mild-to-severe asthma: a network meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2000625. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00625-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beasley R, Braithwaite I, Semprini A, Kearns C, Weatherall M, Harrison TW, et al. ICS-formoterol reliever therapy stepwise treatment algorithm for adult asthma. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1901407. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01407-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beasley R, Beckert L, Fingleton J, Hancox RJ, Harwood M, Hurst M, et al. Asthma and respiratory foundation NZ adolescent and adult asthma guidelines 2020: a quick reference guide. N Z Med J. 2020;133:73–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beasley R, Harper J, Bird G, Maijers I, Weatherall M, Pavord ID. Inhaled corticosteroid therapy in adult asthma: time for a new therapeutic dose terminology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:1471–1477. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1868CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heaney LG, Busby J, Hanratty CE, Djukanovic R, Woodcock A, Walker SM, et al. investigators for the MRC Refractory Asthma Stratification Programme. Composite type-2 biomarker strategy versus a symptom-risk-based algorithm to adjust corticosteroid dose in patients with severe asthma: a multicentre, single-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:57–68. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30397-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beasley R, Braithwaite I, Semprini A, Kearns C, Weatherall M, Pavord ID. Optimal asthma control: time for a new target. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1480–1487. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201910-1934CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pavord ID, Beasley R, Agusti A, Anderson GP, Bel E, Brusselle G, et al. After asthma: redefining airways diseases. Lancet. 2018;391:350–400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30879-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patel M, Pilcher J, Reddel HK, Qi V, Mackey B, Tranquilino T, et al. SMART Study Group. Predictors of severe exacerbations, poor asthma control, and β-agonist overuse for patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:751–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, Barnes PJ, Zheng J, Gustafson P, et al. Effect of a single day of increased as-needed budesonide-formoterol use on short-term risk of severe exacerbations in patients with mild asthma: a post-hoc analysis of the SYGMA 1 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]