Abstract

Background:

Complex Care for Kids Ontario (CCKO) is a multi-year strategy aimed at expanding a hub-and-spoke model to deliver coordinated care for children with medical complexity (CMC) across Ontario.

Objective:

This paper aims to identify the facilitators, barriers and lessons learned from the implementation of the Ontario CCKO strategy.

Method:

Alongside an outcome evaluation of the CCKO strategy, we conducted a process evaluation to understand the implementation context, process and mechanisms. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 38 healthcare leaders, clinicians and support staff from four regions involved in CCKO care delivery and/or governance.

Results:

Facilitators to CCKO implementation were sustained engagement of system-wide stakeholders, inter-organizational partnerships, knowledge sharing and family engagement. Barriers to CCKO implementation were resources and funding, fragmentation of care, aligning perspectives between providers and clinical staff recruitment and retention.

Conclusion:

A flexible approach is required to implement a complex, multi-centre policy strategy. Other jurisdictions considering such a model of care delivery would benefit from attention to contextual variations in implementation setting, building cross-sector engagement and buy-in, and offering continuous support for modifications to the intervention as and when required.

Abstract

Contexte:

La stratégie pluriannuelle Complex Care for Kids Ontario (CCKO) vise la diffusion d'un modèle en étoile pour offrir des soins coordonnés aux enfants présentant une complexité médicale en Ontario.

Objectif:

Ce document vise à identifier les facilitateurs, les obstacles et les leçons apprises de la mise en œuvre de la stratégie du CCKO en Ontario.

Méthode:

Parallèlement à une évaluation des résultats de la stratégie du CCKO, nous avons mené une évaluation du processus pour en comprendre le contexte, les procédés et les mécanismes de mise en œuvre. Des entretiens semi-structurés ont été menés auprès de 38 dirigeants, cliniciens et personnel de soutien de quatre régions impliquées dans la prestation des soins ou la gouvernance du CCKO.

Résultats:

Les facilitateurs de la mise en œuvre du CCKO étaient l'engagement soutenu des intervenants à l'échelle du système, les partenariats interorganisationnels, le partage des connaissances et l'engagement des familles. Les obstacles à la mise en œuvre du CCKO étaient les ressources et le financement, la fragmentation des soins, l'harmonisation des perspectives entre les prestataires ainsi que le recrutement et la rétention du personnel clinique.

Conclusion:

Une approche flexible est nécessaire pour mettre en œuvre une stratégie politique complexe et multicentrique. D'autres autorités qui envisagent un tel modèle de prestation de soins bénéficieraient d'une attention accrue aux variations contextuelles de la mise en œuvre, notamment en renforçant l'engagement et l'adhésion intersectoriels et en offrant un soutien continu pour les modifications de l'intervention au besoin.

Introduction

Children with medical complexity (CMC) are characterized by chronic medical conditions, technology dependence, functional limitations and high healthcare utilization with multiple care providers from hospital to home (Cohen et al. 2011b). CMC account for less than 1% of Canada's children but a strikingly disproportionate use of healthcare across sectors of care, including 57% of all paediatric hospital costs (CIHI 2020). CMC may have substantial benefits from targeted and structured complex care interventions that aim to integrate care by providing a dedicated care coordinator, team-based care or shared plans of care (Berry et al. 2014; Cohen et al. 2012; Kuo et al. 2016). Building upon locally existing best practice models for CMC (Cohen et al. 2011a; Major-Cook et al. 2014), a provincial policy strategy known as Complex Care for Kids Ontario (CCKO) was launched in 2015 to expand integrated care for CMC across Ontario.

Advancements in medical technology, the growing burden of chronic diseases and fiscal constraints are putting immense pressure on health systems to restructure service delivery to reduce inefficiencies and improve quality of care (Goodwin et al. 2012; Valentijn et al. 2013). As the optimal care of patients with complex care needs requires a comprehensive understanding of the multi-system factors contributing to their well-being and a dedicated interprofessional team to monitor and address concerns, a variety of care delivery models have been developed and tested to support patients with complex needs (Coleman et al. 2017; Frankel and Bourgeois 2018; Poot et al. 2017). These complex interventions may contain many interconnected parts, target more than one group or organizational level, address multiple outcomes and work best when tailored to local contexts (Campbell et al. 2000; Craig et al. 2008). Process evaluations assessing the conditions of implementation and how delivery is achieved can shed important light on why an intervention was effective or ineffective, how the intervention works in practice and how a future design of similar families of interventions can be improved (Craig et al. 2008). To date, little is known about how context influences the implementation of multi-centre care integration interventions that have locally tailored activities targeting multiple professional groups and healthcare organizations (French et al. 2020; O'Cathain et al. 2013).

This paper presents a process evaluation conducted alongside a pragmatic randomized controlled trial of CCKO. It describes the contextual facilitators and barriers shaping intervention delivery and discusses the learnings for real-world implementation of population-level integrated care strategies. The findings of this study address current knowledge gaps around evaluating complex integrated care interventions, and offer insights and guidance for future design, implementation and evaluation of similar interventions – not just for CMC, but also for other complex patient populations whose care needs span multiple life domains and systems of care.

Background: CCKO Provincial Strategy

The CCKO strategy is based on a hub-and-spoke care delivery model for CMC, whereby each of the four tertiary paediatric hospitals ("hubs") in Ontario are responsible for both running an ambulatory complex care program within their centre and working collaboratively with care providers in the community to establish tertiary-integrated complex care clinics ("spokes") in different parts of their defined region (Major et al. 2018; Rosenbaum 2008). Northern Ontario is a dedicated region, which is a shared responsibility between the four regional hub sites.

CCKO clinics aim to improve care continuity and coordination, facilitate communication between the patient's family and members of the care team and reduce health system costs (Orkin et al. 2019; PCMCH 2017). In active partnership with the children, their family and multidisciplinary providers, a tertiary-care-based nurse practitioner (NP) functions as a clinical key worker coordinating services in concert with medical specialists, allied health professionals, home and community care coordinators and community hospital physicians (Orkin et al. 2019). The NP develops and manages another important feature of the strategy – an individualized medical care plan that is used to facilitate care coordination among providers in multiple settings by streamlining information sharing and consolidating clinical visits (Gresley-Jones et al. 2015).

Setting for CCKO Implementation

The Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health (PCMCH) is accountable to the Ontario Ministry of Health in leading the maternal-child healthcare system (Hepburn and Booth 2012). PCMCH oversees the implementation of the CCKO strategy by engaging and collaborating with the four regional hub sites, community partners and representatives from other sectors that deliver essential care to CMC.

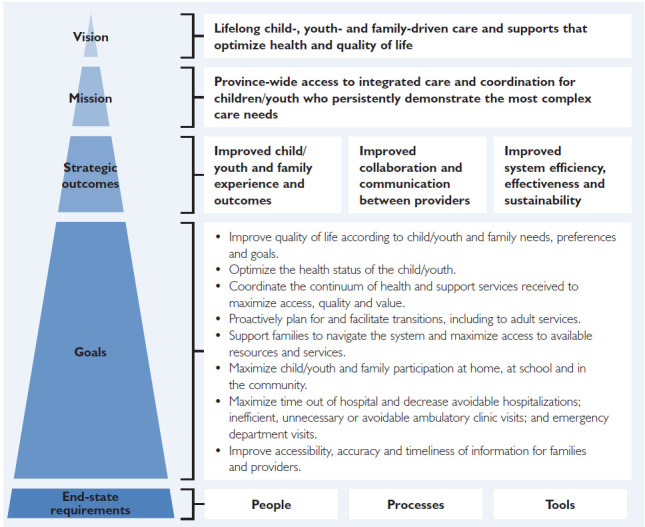

The CCKO strategy was launched in 2015 as a five-year demonstration project based on cumulative recommendations from key stakeholders (PCMCH 2013) that were consolidated into a strategic framework (Figure 1). Funding has been allocated to each region according to the proportion of eligible children. All regions used the bulk of the funds to support the role of the NP.

Figure 1.

CCKO strategic framework

Provincial Policy Context

The CCKO strategy was developed in alignment with larger government-funded programs, including Health Links (2012) and the Ontario Special Needs Strategy (2014) designed to support people with chronic complex conditions and their families (Government of Ontario 2012, 2014). The CCKO strategy also aligned with Ontario's health system transformations, including the Patients First Strategy (2015), aimed at improving patient-centredness and health system accountability for important outcomes (Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care 2015).

CCKO Project Governance

Within its mandate as a provincial program, the PCMCH provides project oversight and implementation support for the CCKO strategy. PCMCH has convened a CCKO-focused Leadership Table that provides strategic oversight and shared accountability for the planning and implementation of the CCKO strategy (Box 1).

Box 1. CCKO Leadership Table.

|

Mandate Meet at least quarterly and provide strategic direction for the following:

|

Composition

|

Evaluation of The CCKO Strategy

Pragmatic Trial

An outcome evaluation of the CCKO strategy is being conducted using a pragmatic, randomized, waitlist control trial that compares the effectiveness of the CCKO model to usual, uncoordinated care for CMC in Ontario. A detailed protocol for the outcome evaluation of CCKO has been reported elsewhere (Orkin et al. 2019), and results will be published separately (anticipated in 2022).

Process Evaluation

A process evaluation of the CCKO strategy reported in this paper was conducted in the final year of the demonstration project to understand how implementation was achieved across the regions and to identify contextual issues necessary for implementation success. Findings will help determine the best approach for stabilizing and expanding paediatric ambulatory complex care programs in Ontario.

Method

This is a qualitative study with healthcare leaders, clinicians and support staff from healthcare delivery and policy/planning organizations involved in CCKO implementation. Administrative and program monitoring data collected and maintained by the PCMCH from 2015 to 2019 were used to corroborate and augment the interview data. This work was guided by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) process evaluation framework, which includes three major domains: (1) implementation (how the intervention is implemented); (2) mechanisms of impact (intermediate mechanisms by which the intervention generates its outcomes); and (3) context (facilitators and barriers that affect an intervention's implementation or its effects) (Moore et al. 2015). This study was approved by The Hospital for Sick Children Research Ethics Board (REB number: 1000062809). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants and Recruitment

Regional hub sites based in tertiary paediatric hospitals (n = 4) and complex care clinics (n = 10) based either in a community hospital or a children's treatment centre that implemented the CCKO strategy were identified for study inclusion. The administrative lead at each regional hub site facilitated access to eligible participants from their region. In May 2019, we used purposive sampling to recruit medical and administrative leads, front-line healthcare providers and support staff and Leadership Table ex officio members involved in CCKO implementation between October 2015 and May 2019. A maximum variation sampling approach guided the selection of participants with heterogeneity in their professions, care settings and sectors, level and region of CCKO implementation. We reached theoretical saturation of perspectives that reflect the experiences of diverse individuals involved in CCKO. Potential participants were recruited via e-mail invitation letters.

Data Collection

Between June and August 2019, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 38 participants who provided informed written consent to participate. Open-ended interview questions (Appendix 1, available online at here) informed by the MRC process evaluation components explored the processes entailed in implementing the CCKO strategy from the perspectives of healthcare leaders, clinicians and support staff. The interview questions also focused on how participants responded to and interacted with the CCKO strategy, and the facilitators and barriers that influenced the CCKO's delivery. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy.

Data Analysis

Coding of the interview transcripts was conducted by three members of the research team (Samantha Quartarone, Jia Lu Lilian Lin and Carol Y. Chan). Interpretive description analysis was performed to make sense of participants' experiences related to CCKO implementation in the context of the practice setting (Thorne 2008; Thorne et al. 1998). Interview transcripts were organized and coded using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo 12. High-level codes were developed deductively from the MRC framework (Moore et al. 2014). Sub-codes were generated inductively through repeated data immersion and iterative coding based on “emergent” themes (Thorne et al. 1998). The codebook was continually refined through the addition, grouping and regrouping of codes and team discussions to develop and refine context-sensitive interpretations and explanations.

Results

Table 1 provides a detailed breakdown of study participants according to their role in implementing the CCKO strategy. Among the 38 participants, 11 (29%) were members of the CCKO Leadership Table and included clinical and administrative leads of regional hub sites and ex officio members, 23 (61%) were front-line healthcare providers and the remaining four (11%) were involved in CCKO delivery in an administrative role within a complex care clinic.

Table 1.

Participant breakdown by CCKO role

| CCKO role | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Leadership Table member | 11 (29) |

| Clinical lead of regional hub site | 4 (11) |

| Administrative lead of regional hub site | 4 (11) |

| Ex officio member* | 3 (8) |

| Healthcare provider (not on Leadership Table) | 23 (61) |

| Nurse practitioner | 8 (21) |

| Physician | 6 (16) |

| Allied health professional | 4 (11) |

| Home and community care coordinator | 5 (13) |

| Administrative staff (not on Leadership Table) | 4 (11) |

| Program manager | 2 (5) |

| Administrative coordinator† | 2 (5) |

| Total | 38 (100) |

Members of the CCKO Leadership Table who had no direct involvement in care delivery at any CCKO clinic

Individuals responsible for scheduling and coordinating patient appointments and other nonmedical matters

The CCKO strategy was implemented via a low-to-high fidelity approach, encouraging regions at various levels of paediatric complex care development to use their dedicated funding to stimulate start-up as they best saw fit. Newer regions were supported to gradually increase fidelity to the CCKO model by adhering to the core components of CCKO (i.e., clinical key worker, complex care plan and care coordination). This paper reports on the contextual influences on CCKO's implementation as this understanding will be crucial for explaining potential variation in intervention effects and identifying optimal approaches for scaling up and adapting the CCKO to other settings or populations (Craig et al. 2018).

Facilitators and Barriers to CCKO Implementation

Table 2 summarizes the facilitators and barriers to implementing the CCKO strategy.

Table 2.

Facilitators and barriers to CCKO implementation

| Facilitators | Barriers |

|---|---|

|

|

Facilitators

Provincial project governance and community of practice

Participants described how the provincial project governance, including convening a CCKO-specific Leadership Table, facilitated implementation. Context-specific challenges and gaps in the provincial service delivery system for CMC were voiced. For instance, the CCKO standardized enrollment criteria were liberalized to include rurality as a criterion to promote equitable access to care. Leadership Table members appreciated the opportunity to share and learn about practices for creatively implementing CCKO locally. One Leadership Table member recalled the following:

I really liked the creativity of some of the sites. [F]or example, in the … region, they had their complex care clinic … embedded in their children's treatment centre… We thought that was really innovative in that region [be]cause it was getting closer to home and was putting less of a burden on families to come to a more urbanized bigger city. … Each region came up with their own interesting approaches to what was best for their geography and their resources.

Moreover, through the work of the Leadership Table in fostering stronger cross-regional relationships, the more established regions hosted multiple site visits for clinicians and administrators from newer regions to gain a thorough understanding of how the complex care program operates. This community of practice furthered the capacity of newer regions to build their own complex care delivery model based on local conditions.

The Leadership Table promoted the exchange and integration of perspectives between hospital and non-hospital actors. Healthcare leaders from community and rehabilitation care saw CCKO as “the biggest opportunity to build relationships, and essentially establish the credibility of community-based providers.”

Inter-organizational Partnerships

Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs) are Ontario's regional health authorities that plan, fund and integrate local healthcare services (Ronson 2006). The 14 geographically defined LHINs are important system partners in the CCKO strategy, with LHIN care coordinators providing case management and coordination of home and community services for CMC (Cohen et al. 2011a). Given the sustained relationships that LHIN care coordinators establish with families, and CMC's almost universal need for LHIN-based resources (e.g., home care), strong partnerships between complex care clinics and LHINs is essential for delivering holistic care and bridging the gaps between the medical and community service sectors. Since the initiation of the CCKO strategy, LHIN care coordinators have attended complex care clinic visits more consistently. LHINs that were well integrated with complex care clinics tended to have a longer history of collaboration with complex care; LHIN-initiated care coordination services targeting CMC; and/or dedicated LHIN care coordinators to attend complex care clinic visits.

Despite the separate funding streams for tertiary hub sites and children's developmental and rehabilitation services (e.g., children's treatment centres in Ontario), novel partnerships occurred through the CCKO strategy, whereby healthcare providers from tertiary hub sites ran collaborative clinics at children's treatment centres in smaller, less urbanized communities. A CCKO Leadership Table member described this innovative adaptation to the CCKO model as demonstrating

the capacity and expertise that lives within the community [and providing] the opportunity to deliver care close to home, enable a better care experience and bring a hospital team and a community team together around the family.

Stronger relationships between complex care teams and rehabilitation providers streamlined information sharing and increased the frequency of co-located appointments.

Knowledge Sharing Between Tertiary Hub Sites and Complex Care Clinics

The CCKO's hub-and-spoke care delivery model – whereby NPs from tertiary complex care teams travelled to community clinics to work in collaboration with the local care team – enabled cross-site knowledge sharing, which was instrumental in the expansion of complex care clinics. The NPs brought specialized paediatric complex care knowledge and logistics experience for new clinics. In one CCKO region, the tertiary hub site had a centralized referral system to triage new patient referrals, which lessened the administrative burdens on community clinics.

Family Engagement In Care Delivery, Program Design and Governance

Family engagement occurred on three levels of the CCKO strategy: (1) at the clinical level as a key member of the multidisciplinary complex care team; (2) at the regional level on the tertiary care centre's complex care family advisory council; and (3) at the provincial level as a member of the CCKO Leadership Table.

Some regions had established strong partnerships with family advisors in developing new complex care clinics by involving families of CMC in program co-design and advocacy for clinic funding alongside clinical leaders. At the provincial level, family advisors sat on the Leadership Table, and families from across the province participated in annual CCKO symposia and contributed to CCKO strategic planning.

Barriers

Resources and Funding

The common Canadian challenge with scaling up innovative healthcare practices was reflected in the CCKO strategy, which was created as a demonstration project with concurrent evaluation of its effectiveness (Bégin et al. 2009; Health Canada 2015). This pilot project status created a sense of uncertainty about sustainability. Disparities in resourcing and access to specialized healthcare services across Ontario complicated the CCKO strategy's goal of delivering consistent access to and quality of complex care services regardless of geographic location. The greatest disparities in resource availability, provider expertise and service system capacity were seen between urban centres and Northern Ontario, which is a large and dispersed region. A disjointed funding structure that requires both provincial and federal funding streams in some Northern Ontario communities was another barrier to CCKO's consistent care delivery.

Social workers played an integral role in helping families access counselling, social supports and funding. However, most CCKO clinics functioned without a dedicated complex care social worker and often had to “borrow” social workers from other departments. For families, a lack of nursing care and mental health support were among their biggest challenges. As discussed by several complex care providers,

these families are some of the most complex, stressed families [that] need a very specialized type of support.

The legislated service maximums exacerbated families' struggles when their care needs exceeded the amount of nursing and personal support services for which they qualified. Although funding for the CCKO strategy began to encompass allied health professionals in the strategy's later years, it remained insufficient to sustain dedicated allied health professionals (e.g., dietitians, social workers) who were endorsed as critical members of complex care teams.

A Fragmented System of Healthcare Delivery

A lack of policy-level integration of the service sectors that CMC and their families depend on hindered complex care providers' ability to provide continuity of care using a provincially standardized approach. One such example highlighted in the interviews was the disconnect between ambulatory complex care programs and primary care. A complex care provider described the situation:

We need to better formalize those partnerships with the family physicians and primary care to work together. … [T]hat's something that has to happen in the future to really provide the wraparound services for these kids so that they have good community care in addition to the complex care in the hospital or in their local hospital or community.

Moreover, the gaps in social and mental health supports for family caregivers of CMC were evident in the pervasiveness of parental burnout, which was beyond the CCKO strategy's capacity to target and support. A healthcare provider stated the following:

I think these children are well looked after from a medical perspective … but the bigger gap that I'm seeing is that these families are struggling from a mental health perspective. A lot of them have severe fatigue, possibly diagnosed mental illness [and] post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Disconnect in Perspectives Between Providers in Different Settings of Care

A misalignment in perspectives was found between hospital and community providers regarding which resources can be provided in a community setting. From the perspectives of LHIN care coordinators, their role was not fully understood by some members of the hospital-based complex care team, and this created challenges for LHINs to become fully integrated into complex care programs. One LHIN care coordinator said:

One of the things that we do struggle with a lot of times is the assumption that it's just a one-stop shop with the LHIN, and that we have this abundant amount of money that we can just [use to] provide nursing support to every child in the same amount or the maximum amount. And that's not always the case. … We're continuing to work with the complex care team to ensure that families [understand the LHIN's limitations], and to find other options that might be out there to fill in the gaps.

Inconsistencies in organizational policies, standards and health information platforms further challenged interagency providers' ability to collaborate as an “integrated team.” Although a lack of alignment in perspectives discouraged information sharing between sites, LHIN care coordinators felt optimistic because communication between the hospital and community providers has been steadily improving as complex care programs become more established.

Limitations in Clinical Infrastructure

Shortage of available clinic space made it necessary to limit the frequency of clinic days and appointment length at sites. For example, one complex care clinic could only allot two hours for each intake appointment and 45 minutes for each follow-up. The NP shared the following:

[T]hat puts a lot of pressure [on] the appointments. … 45 minutes is not enough time to have a dietitian see them and do a comprehensive history, do a full med[ication] reconciliation, do a systems review, talk about the issues, do a physical exam and have a multidisciplinary team approach. [I]t becomes even more challenging when you have an interpreter and communication takes a little bit longer.

The lack of clinic space with specialized equipment and medical technology was a barrier for clinics to accommodate highly medically complex or acutely unwell patients.

Challenges with Recruitment and retention of Healthcare Professionals

During the CCKO expansion, clinics farther away from urban centres encountered serious workforce shortages – particularly regarding NP hiring and retention – that slowed down the establishment of new complex care clinics. Some regions were impacted by a shortage of bilingual healthcare providers to serve francophone communities.

Shortages of administrative staff sometimes pushed complex care NPs to assume additional administrative tasks related to appointment coordination, which diminished the clinics' ability to attract and retain NPs. At one site, the high provider turnover made families reluctant to enroll in the program and weakened their trust in the clinic.

Conversely, clinical staff recruitment was less challenging in clinics based in urban centres, where most of Ontario's specialized training programs in paediatric complex care are offered, enabling these complex care clinics to hire more NPs with a high level of expertise.

Across the province, especially in rural and remote communities, engaging community paediatricians to support care for CMC was difficult due to fee-for-service billing structures and the need for longer appointments. Suboptimal engagement from community paediatricians in one region led to the adoption of an adapted model whereby the entire tertiary complex care team travelled to community clinics to provide comprehensive care. While this was beneficial for some families, it incurred additional costs and burden to the tertiary centre, was unsustainable in the long term and likely did not help empower local communities in caring for CMC.

Discussion

The CCKO strategy's strong engagement of cross-disciplinary stakeholders – underpinned by consistent alignment with Ontario's healthcare policy priorities throughout project establishment and implementation – made it a unique case study of the influence of context on a large-scale complex policy strategy. The MRC framework, which recognizes that complex interventions may work better if they are sensitive and tailored to the local context and culture, helped understand how contextual factors facilitated or hindered the implementation of CCKO (Craig et al. 2018; Craig et al. 2019).

The use of a low-to-high fidelity approach to CCKO implementation allowed regions that had more established complex care programs to share their expertise and experience with newer regions by hosting site visits and engaging in ongoing knowledge exchange. Newer regions were supported to gradually adopt components of the CCKO model in line with regional capacity, resources and circumstances. However, this flexible implementation approach has likely contributed to variations in CCKO impact across regions, based on interactions between the intervention components and differential regional contexts. Our results demonstrated that the geographical, cultural, organizational and financial domains of the context from a recent MRC framework played predominant roles in CCKO implementation (Craig et al. 2018). In expanding the CCKO strategy, greater attention to the provisions that already exist in each region and assessment of these key domains of context is needed to avoid reinforcing inequitable access to care across Ontario.

The fragmentation of the healthcare system and compartmentalization of services across sectors are known barriers to complex care program implementation (Altman et al. 2018; Foster et al. 2017; Miller et al. 2009). In our study, healthcare professionals voiced concerns that the disjointed healthcare system with siloed funding streams impeded their capacity to provide continuous and holistic care to families. These findings echo those of an Ontario study of health systems integration, which showed that complex rules, top-down control and rigid structures constrained integrated care development (Tsasis et al. 2012). Healthcare professionals in our study sometimes needed to use ad hoc approaches to bridge cross-sectoral services for CMC. Similar to Tsasis et al. (2012), we observed a disconnect in perspectives and communication difficulties among providers from different care settings.

Extending prior research on the influence of geographic factors on care coordination for CMC (Cady and Belew 2017; Miller et al. 2009), we found the geographical context to be a strong determinant for other implementation barriers and facilitators, including health system structure, resources and funding, cross-sector partnerships and provider recruitment and retention. For example, the costs of scaling up CCKO was likely higher in a region with a more dispersed population, as was the difficulty in recruiting and retaining providers with specialized paediatric expertise.

Based on team discussions of study findings grounded in the complex intervention implementation literature, we present the following recommendations for stabilizing and expanding paediatric ambulatory complex care programs in Ontario as the CCKO strategy moves from a demonstration project to an annually funded initiative:

A collaborative governance structure with representation from a wide array of stakeholders is essential for implementing large-scale initiatives that require cross-discipline and cross-sector partnerships (Suter et al. 2009). The PCMCH should continue to serve as the oversight organization for CCKO to facilitate the engagement of system-wide stakeholders, co-development of provincial care delivery standards and inter-organizational partnerships.

Considerable asymmetries in access to resources between CCKO regions due to geographical factors warrant an adaptable approach to expanding complex care programs in each region. Stable funding support is needed for tailoring the intervention to address the unique social, cultural, organizational and financial barriers to care integration in each region. This implementation approach should be fluid as needs change in each region.

Finally, complex care scaling-up efforts should prioritize the building of local capacity by strengthening partnerships between tertiary hub sites and community partners, such as the 26 children's treatment centres in Ontario, to operate complex care clinics. Strategic partnerships will nurture a holistic understanding and shared vision for systems integration (Humowiecki et al. 2018) and enable optimal leveraging of existing human resources, clinic space and remote care technologies in the community to provide high-quality care closer to home.

The findings from this process evaluation of CCKO will enrich our interpretation of the pragmatic trial results in three key ways. First, a nuanced understanding of the differential contexts across implementing regions will allow us to draw links between issues in the external environment and possible variation in CCKO effectiveness between regions. Second, mapping out how CCKO implementation was tailored to meet the needs of local context will help us identify potential reasons that the intervention's actual impact may have differed from its expected impact. Finally, we will be able to contextualize the pragmatic trial results to generate new learnings about the transferability of the CCKO strategy to other jurisdictions that have a different set of implementation circumstances.

Future research on large-scale implementation of complex interventions may explore how domains of context shape intervention modifications and shed light on key considerations when developing intervention modifications tailored to local context. Process evaluation frameworks for complex interventions should incorporate clearer guidance that accounts for variations in the context of implementation and intervention modifications, particularly for multi-site interventions (Evans et al. 2019). Future research on paediatric complex care should build on current knowledge of its theoretical active ingredients, and investigate how contextual variables could be systematically incorporated into intervention design to achieve intervention effectiveness in adapted settings (Feudtner and Hogan 2021).

Limitations

This multi-centre study included a heterogeneous sample of healthcare leaders, clinicians and support staff from diverse care delivery settings serving CMC. Recruiting a maximum variation sample enabled the collection of rich data. While almost one third of participants were members of the CCKO Leadership Table, the remaining participants held mostly clinical roles. The heavy representation of healthcare providers in our sample may have led the perspectives of clinicians to dominate in our findings. This study did not report on implementation fidelity, reach or process, or family member perspectives. These will be reported in ongoing research assessing the outcomes of CCKO.

Conclusion

This study provided insights into the barriers and facilitators to implementing a provincial policy strategy for improving system-wide care delivery for CMC. Contextual factors are found to be interconnected but varied across regions, highlighting the significant role played by context on implementation and program effectiveness (Craig et al. 2018). A flexible approach to CCKO implementation was welcomed by regions that tailored the program to meet local resources and circumstances. Other jurisdictions considering such a model of care delivery would benefit from attention to contextual variations in implementation setting, building engagement and buy-in from cross-sector stakeholders and offering continuous support for modifications to the intervention as and when required.

Contributor Information

Jia Lu Lilian Lin, PhD Candidate, Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

Samantha Quartarone, Clinical Research Project Coordinator, Child Health Evaluative Sciences, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON.

Nasra Aidarus, Senior Program Manager, Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health, Toronto, ON.

Carol Y. Chan, Clinical Research Project Manager, Child Health Evaluative Sciences, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON.

Jackie Hubbert, Clinical Director, Labatt Family Heart Centre and Critical Care Services, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON.

Julia Orkin, Medical Officer, Integrated Community Partnerships and Complex Care Program, The Hospital for Sick Children; Associate Professor, Department of Paediatrics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

Nora Fayed, Assistant Professor, School of Rehabilitation Therapy, Queen's University, Kingston, ON.

Nathalie Major, Medical Director, Champlain Complex Care Program, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario; Assistant Professor, Department of Paediatrics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON.

Joanna Soscia, Nurse Practitioner and Clinical Practice Lead, Complex Care Program, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON.

Audrey Lim, Medical Lead, Complex Care Program, McMaster Children's Hospital – Hamilton Health Sciences; Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON.

Simon D. French, Professor, Department of Chiropractic, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.

Myla E. Moretti, Health Economist and Senior Research Associate, Clinical Trials Unit, Ontario Child Health Support Unit, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON.

Eyal Cohen, Professor, Department of Paediatrics and Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto; Senior Scientist and Program Head, Child Health Evaluative Sciences, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON.

Funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (funding reference number: FDN-143315).

References

- Altman L., Zurynski Y., Breen C., Hoffmann T., Woolfenden S.. 2018. A Qualitative Study of Health Care Providers' Perceptions and Experiences of Working Together to Care for Children with Medical Complexity (CMC). BMC Health Services Research 18: 70. 10.1186/s12913-018-2857-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bégin M., Eggertson L., Macdonald N.. 2009. A Country of Perpetual Pilot Projects. CMAJ 180(12): 1185. 10.1503/cmaj.090808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J.G., Hall M., Neff J., Goodman D., Cohen E., Agrawal R. et al. 2014. Children with Medical Complexity and Medicaid: Spending and Cost Savings. Health Affairs 33(12): 2199–206. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady R.G., Belew J.L.. 2017. Parent Perspective on Care Coordination Services for Their Child with Medical Complexity. Children 4(6): 45. 10.3390/children4060045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M., Fitzpatrick R., Haines A., Kinmonth A.L., Sandercock P., Spiegelhalter D. et al. 2000. Framework for Design and Evaluation of Complex Interventions to Improve Health. BMJ 321: 694. 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes for Health Information (CIHI). 2020. Children and Youth with Medical Complexity in Canada. Retrieved November 21, 2020. <https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/children-youth-with-medical-complexity-report-en.pdf>.

- Cohen E., Bruce-Barrett C., Kingsnorth S., Keilty K., Cooper A., Daub S.. 2011a. Integrated Complex Care Model: Lessons Learned from Inter-Organizational Partnership. Healthcare Quarterly 14(Spec No 3): 64–70. 10.12927/hcq.0000.22580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E., Kuo D.Z., Agrawal R., Berry J.G., Bhagat S.K.M., Simon T.D. et al. 2011b. Children with Medical Complexity: An Emerging Population for Clinical and Research Initiatives. Pediatrics 127(3): 529–38. 10.1542/peds.2010-0910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E., Lacombe-Duncan A., Spalding K., MacInnis J., Nicholas D., Narayanan U.G. et al. 2012. Integrated Complex Care Coordination for Children with Medical Complexity: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of Tertiary Care-Community Collaboration. BMC Health Services Research 12(1): 366. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman K.J., Magnan S., Neely C., Solberg L., Beck A., Trevis J. et al. 2017. The Compass Initiative: Description of a Nationwide Collaborative Approach to the Care of Patients with Depression and Diabetes and/or Cardiovascular Disease. General Hospital Psychiatry 44: 69–76. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig P., Di Ruggiero E., Frohlich K.L., Mykhalovskiy E., White M.; on behalf of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)–National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Context Guidance Authors Group (listed alphabetically). 2018. Taking Account of Context in Population Health Intervention Research: Guidance for Producers, Users and Funders of Research. NIHR Journals Library. 10.3310/cihr-nihr-01. [Google Scholar]

- Craig P., Dieppe P., Macintyre S., Michie S., Nazareth I., Petticrew M.. 2008. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: The New Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ 337: a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig P., Dieppe P., Macintyre S., Michie S., Nazareth I., Petticrew M.. 2019. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: Following Considerable Development in the Field since 2006, MRC and NIHR Have Jointly Commissioned an Update of This Guidance to Be Published in 2019. Medical Research Council. Retrieved March 5, 2021. <https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance/>.

- Evans R.E., Craig P., Hoddinott P., Littlecott H., Moore L., Murphy S. et al. 2019. When and How Do ‘Effective’ Interventions Need to Be Adapted and/or Re-Evaluated in New Contexts? The Need for Guidance. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 73(6): 481–82. 10.1136/jech-2018-210840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feudtner C., Hogan A.K.. 2021. Identifying and Improving the Active Ingredients in Pediatric Complex Care. JAMA Pediatrics 175(1): e205042. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster C.C., Mangione-Smith R., Simon T.D.. 2017. Caring for Children with Medical Complexity: Perspectives of Primary Care Providers. The Journal of Pediatrics 182: 275–82.e4. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel S., Bourgeois J.A. (eds.). 2018. Integrated Care for Complex Patients: A Narrative Medicine Approach. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- French C., Pinnock H., Forbes G., Skene I., Taylor S.J.C.. 2020. Process Evaluation within Pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trials: What Is It, Why Is It Done, and Can We Find It? – A Systematic Review. Trials 21(1): 916. 10.1186/s13063-020-04762-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin N., Smith J., Davies A., Perry C., Rosen R., Dixon A. et al. 2012. A Report to the Department of Health and the NHS Future Forum. Integrated Care for Patients and Populations: Improving Outcomes by Working Together. The King's Fund. Retrieved February 22, 2021. <https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/integrated-care-patients-populations-paper-nuffield-trust-kings-fund-january-2012.pdf>.

- Government of Ontario. 2012, December06. About Health Links [Archived]. Retrieved November 10, 2020. <https://news.ontario.ca/en/backgrounder/22834/about-health-links>.

- Government of Ontario. 2014, August27. Helping Children and Youth with Special Needs Achieve Their Goals [News release]. Retrieved November 10, 2020. <https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/30209/helping-children-and-youth-with-special-needs-achieve-their-goals>.

- Gresley-Jones T., Green P., Wade S., Gillespie R.. 2015. Inspiring Change: How a Nurse Practitioner-Led Model of Care Can Improve Access and Quality of Care for Children with Medical Complexity. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 29(5): 478–83. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. 2015, July. Unleashing Innovation: Excellent Healthcare for Canada. Report of the Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation. Retrieved July 20, 2020. <https://healthycanadians.gc.ca/publications/health-system-systeme-sante/report-healthcare-innovation-rapport-soins/alt/report-healthcare-innovation-rapport-soins-eng.pdf>.

- Hepburn C.M., Booth M.. 2012. Ontario's Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health: Building a Productive, System-Level, Change-Oriented Organization. Healthcare Quarterly 15 (Special Issue 4): 54–62. 10.12927/hcq.2013.22940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humowiecki M., Kuruna T., Sax R., Hawthorne M., Hamblin A., Turner S. et al. 2018, December. Blueprint for Complex Care: Advancing the Field of Care for Individuals with Complex Health and Social Needs. The National Center for Complex Health and Social Needs, the Center for Health Care Strategies and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Retrieved March 5, 2021. <https://www.nationalcomplex.care/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Blueprint-for-Complex-Care_UPDATED_030119.pdf>.

- Kuo D.Z., Berry J.G., Glader L., Morin M.J., Johaningsmeir S., Gordon J.. 2016. Health Services and Health Care Needs Fulfilled by Structured Clinical Programs for Children with Medical Complexity. The Journal of Pediatrics 169: 291–296.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major-Cook N., Ridha S., Krantz C., Marcotte A., Tatartcheff-Quesnel N., Budge A.. 2014. 30: Impact of Implementing a Complex Care Program. Paediatrics & Child Health 19(6): e46. 10.1093/pch/19.6.e35-29. [Google Scholar]

- Major N., Rouleau M., Krantz C., Morris K., Séguin F., Allard M. et al. 2018. It's About Time: Rapid Implementation of a Hub-and-Spoke Care Delivery Model for Tertiary-Integrated Complex Care Services in a Northern Ontario Community. Healthcare Quarterly 21(2): 35–40. 10.12927/hcq.2018.25624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.R., Condin C.J., McKellin W.H., Shaw N., Klassen A.F., Sheps S.. 2009. Continuity of Care for Children with Complex Chronic Health Conditions: Parents' Perspectives. BMC Health Services Research 9: 242. 10.1186/1472-6963-9-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore G., Audrey S., Barker M., Bond L., Bonell C., Hardeman W. et al. 2014. Process Evaluation of Complex Interventions: UK Medical Research Council (MRC) Guidance. MRC Population Health Science Research Network. Retrieved February 26, 2020. <https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/mrc-phsrn-process-evaluation-guidance-final>. [Google Scholar]

- Moore G., Audrey S., Barker M., Bond L., Bonell C., Hardeman W. et al. 2015. Process Evaluation of Complex Interventions: Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ 350: h1258. 10.1136/bmj.h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Cathain A., Thomas K.J., Drabble S.J., Rudolph A., Hewison J.. 2013. What Can Qualitative Research Do for Randomised Controlled Trials? A Systematic Mapping Review. BMJ Open 3: e002889. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. 2015, February. Patients First: Action Plan for Health Care. Retrieved May 20, 2020. <http://health.gov.on.ca/en/ms/ecfa/healthy_change/docs/rep_patientsfirst.pdf>.

- Orkin J., Chan C.Y., Fayed N., Lin J.L.L., Major N., Lim A. et al. 2019. Complex Care for Kids Ontario: Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Randomised Controlled Trial of a Population-Level Care Coordination Initiative for Children with Medical Complexity. BMJ Open 9: e028121. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poot A.J., de Waard C.S., Wind A.W., Caljouw M.A.A., Gussekloo J.. 2017. A Structured Process Description of a Pragmatic Implementation Project: Improving Integrated Care for Older Persons in Residential Care Homes. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 54. 10.1177/0046958017737906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health (PCMCH). 2013. Pursuing the Possible: An Action Plan for Transforming the Experiences of Children and Youth Who Are Medically Fragile and/or Technology Dependent. Retrieved July 20, 2020. <http://www.pcmch.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Pursuing-the-Possible_PCMCH-Action-Plan_-Final_Jan-2013.pdf>.

- Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health (PCMCH). 2017, September26. CCKO Functions of a Complex Care Clinic and Program Standard. Retrieved November 16, 2020. <http://www.pcmch.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CCKO-Functions-of-a-Complex-Care-Clinic-and-Program-Standard-.pdf>.

- Ronson J.2006. Local Health Integration Networks: Will “Made in Ontario” Work? Healthcare Quarterly 9(1): 46–49. 10.12927/hcq.2006.17903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum P.2008, May. Report of the Paediatric Complex Care Coordination Expert Panel. Retrieved July 12, 2021. <https://www.pcmch.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Report-of-the-Paediatric-Complex-Care-Coordation-Expert-Panel-2008.pdf>.

- Suter E., Oelke N.D., Adair C.E., Armitage G.D.. 2009. Ten Key Principles for Successful Health Systems Integration. Healthcare Quarterly 13(Spec No): 16–23. 10.12927/hcq.2009.21092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S.2008. Interpretive Description. Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S., Kirkham S.R., MacDonald-Emes J.. 1998. Interpretive Description: A Noncategorical Qualitative Alternative for Developing Nursing Knowledge. Research in Nursing & Health 20(2): 169–177. 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199704)202<169aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsasis P., Evans J.M., Owen S.. 2012. Reframing the Challenges to Integrated Care: A Complex-Adaptive Systems Perspective. International Journal of Integrated Care 12(5). 10.5334/ijic.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentijn P.P., Schepman S.M., Opheij W., Bruijnzeels M.A.. 2013. Understanding Integrated Care: A Comprehensive Conceptual Framework Based on the Integrative Functions of Primary Care. International Journal of Integrated Care 13(1). 10.5334/ijic.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]