ABSTRACT

The success of COVID-19 vaccination depends on individual’s vaccine acceptance. There has been misinformation on the media that doubts its effectiveness, safety, and long-term risk. Such controversy could affect the acceptance toward the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine. The objective of this study was to assess the factors influencing the acceptance and hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine in Saudi Arabia. A cross-sectional study was conducted. An online survey was conducted with four parameters: Demographics, medical history, knowledge and information sources about COVID-19 and vaccine, and hesitancy/acceptance of vaccinations. Bivariate analysis between several survey items and the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine was conducted using Chi-square test. Logistic regression was used to assess to what degree each variable affects the acceptance and the hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine. Approximately 64% show a desire to accept the vaccine while 18.3% were extremely hesitant to take the vaccine. Non-demographic factors that were associated with the acceptance toward the COVID-19 vaccine were the source of health information about COVID-19 (OR:1.63; 95% CI:1.07–2.47), perception toward whether the vaccine is effective on other variants of the virus (OR:7.24; 95% CI:4.58–11.45), previous uptake of the influenza vaccine (OR:1.62; 95% CI:1.07–2.47), and potential mandatory of vaccination in order to travel internationally (OR:16.52; 95% CI:10.23–26.68). This study provides an insight into factors – other than the sociodemographic – influencing the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine in Saudi Arabia. The government should address the COVID-19-related misinformation and rumors to increase acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, vaccine, acceptance, hesitancy, questionnaire, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has approximately affected 113 million individuals worldwide; of which around 2.5 million people lost their lives.1 Global efforts have been directed toward developing a vaccine to control the pandemic and achieve population immunity.2 Early 2020, scientists across the world started their vaccine trials to fight the pandemic.3 By the end of the year, several vaccine candidates were approved for emergency purposes.4 On December 8, 2020, a 91-year-old woman was the first person to receive Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (two-dose vaccine; 21 days apart) in the world.5 The vaccine was approved for emergency purposes by the food and drug administration (FDA) in the United States on December 11, 2020.6 It later has gained approvals from many countries worldwide.7

In Saudi Arabia, there were over 390,000 confirmed cases and approximately 6600 deaths.8 The Saudi Food and Drug Authority approved the first COVID-19 Vaccine on December 10, 2020,9 and the vaccination campaign was launched later on that week.10 The Ministry of Health (MOH) in Saudi Arabia has facilitated the vaccination registration through a governmental site portal for the public.11,12

The government has been encouraging the public to register for the vaccine through the COVID-19 daily press conference,13 and they have been assuring the general public regarding their safety and effectiveness.14,15 Additionally, individuals who will have received the full two doses will be granted a health-passport without implying the vaccine will be mandated for traveling purposes.16

Despite the oncoming evidence supporting the vaccine’s positive impact, there has been misinformation on the media that doubts its effectiveness, safety, and long-term risk.17–19 Such controversy could increase the hesitancy and affect the acceptance toward the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine.20,21 Previous studies have examined the acceptance level of COVID-19 vaccination from different countries;22–28 however, the variation in the context of the immunization, the geographical area, and culture limit the generalizability of those finding to the Saudi population. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the factors that could influence the acceptance and hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine in Saudi Arabia.

Materials and methods

Design and participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted in January 2021. An online google form questionnaire composed of 29 questions – in the Arabic language – was distributed electronically (Supplementary Material - Appendix A). To identify the respondents, the study used non-probability snowball sampling techniques across the five main regions of Saudi Arabia (Southern, Northern, Central, Eastern, and Western). The use of snowball sampling helps to reach out to as more representative sample as possible to the target population.29 To ensure that only target population has participated in the survey, the study has asked a question from the participant about their current geographic location of residents inside the Saudi Arabia irrespective of their nationality because the vaccine is offered to all residents in Saudi Arabia without any discrimination. To be included in the final analytic sample, the respondents must be 18 years or older, Arabic speaker, and currently reside in Saudi Arabia. Excluded respondents were those who partially submitted their responses, those who filled the survey more than once, and Saudi nationals who reside outside Saudi Arabia. The initial total responses collected were 772. Of which, 14 were excluded because of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final sample size included was 758 participants, which would secure a margin of error of less than 4%.30

Questionnaire development

The questionnaire was implemented in the Arabic language, and the first draft was reviewed by two experts in the survey design; hence, another draft was revised accordingly. The survey was then pretested through randomly selected two individuals by face-to-face interviews to respond to the questionnaire. The Interviews were conducted for each of them after they completed the questionnaire to make sure they had understood the questions in the way they were intended to achieve. Modifications for some questions and choices were further revised to ensure the clarity of the questions and to meet the minimum face validity. The final version was then distributed. The survey comprises four sections: Demographics, medical history, knowledge and information sources about COVID-19 and vaccine, and hesitancy/acceptance of vaccinations. Some items were added to validate responses from previously asked questions to assess the survey’s internal validity. At the end of the survey, one question was included asking whether participants have filled this exact survey before the current time to account for multiple responses by the same participant.

Assessment of outcomes

The main outcomes of the study were 1) the acceptance toward the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine (1. Are you going to take the COVID-19 vaccine when it is available in your region? (Yes/No)), and 2) the degree of hesitancy toward the uptake of COVID-19 vaccine (2. To what degree are you hesitant about getting the vaccine? (scale of 1–5; 1 indicates extremely hesitant, and 5 indicates extremely not hesitant).

Assessment of covariates

Other factors of interest were chosen as a priori based on their potential influence on the acceptance and hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine. These covariates were as follows: Gender, age group, education, being a health practitioner, having chronic diseases, previous infection with COVID-19 of the respondents or their relatives, knowledge about COVID-19 precautions, previous uptake of the influenza vaccine, source of health information about COVID-19, perception of whether the COVID-19 vaccine is effective for other variants of the SARS-COV-2, and desire to take the vaccine if it is required to travel internationally.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported using n (%). For the outcome variables, the acceptance toward the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine was used as a dichotomous variable; however, the scale used for the degree of hesitancy toward the uptake of COVID-19 vaccine was dichotomized by collapsing the first three levels as hesitant, and levels 4 and 5 as not hesitant. Although level 3 was considered neutral, it may indicate a degree of hesitancy or uncertainty; thus, it was grouped with the hesitant category.

For covariate variables, they were used as listed in the questionnaire including gender, age group, being a health practitioner, having chronic diseases, previous uptake of the influenza vaccine, perception of whether the COVID-19 vaccine is effective for other variants of the SARS-COV-2, and desire to take the vaccine if it is required to travel internationally. We collapsed secondary school and high school in one level for the education variable. The variable “previous infection with COVID-19 of the respondents or their relatives” was calculated utilizing two items in the questionnaire: “Have you been diagnosed with COVID-19 and confirmed by PCR testing?” and “Has any of your relatives been diagnosed with COVID-19?”. Each of these questions gave choices to determine the severity of the diagnoses among the respondents and their relatives. The final variable determining the previous infection with COVID-19 of the respondents or their relatives used in the analysis includes three levels “yes, previously infected and have a relative previously infected as well; no, not previously infected, but having a relative previously infected; neither previously infected nor having a relative previously infected.” Knowledge about COVID-19 precautions was used in the analysis as binary utilizing the choices given under the item in the questionnaire, in which the respondents were given multiple precaution measures and were requested to check all that apply. Those who checked all the precautions were categorized as “knowing all precautions,” whereas those who missed any of the precautions listed were categorized as “not knowing all precautions.” The variable “source of health information” was dichotomized using either the respondents get COVID-19 information from Ministry of Health (MOH) official accounts only or from other sources such as social media besides MOH official accounts.

Bivariate analysis between several survey items and the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine was conducted using Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact when appropriate.31 Binary logistic regression was also used to assess to what degree each variable affects the acceptance and the hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine after mutual adjustment of the covariates.32 The model assumption regarding the independence of the observation was met as we excluded those who responded more than once, and we do not have repeated measures in the current analysis.33 Goodness of fit was assessed using Hosmer–Lemeshow test.34 Furthermore, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed, and the area under the curve (AUC) was obtained to assess the model performance as well as its predictive ability.35 Multicollinearity was investigated, which all covariates demonstrated less than 10 of variance inflation factor (VIF).36 Alpha of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all statistical tests. SPSS version 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform the current analyses.

Results

A total of 758 respondents were included in this analysis; of which 60% were males, 32.6% aged between 25 and 34, 70.4% had a university education, 36.5% were health practitioners, 15.3% had a chronic disease, 52.4% ever had taken the influenza vaccine. Furthermore, approximately 64% show a desire to accept the vaccine while 18.3% were extremely hesitant to take the vaccine (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the respondents (N = 758)

| Variable | Class | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 458 | (60.4) |

| Female | 300 | (39.6) | |

| Region of residence | Southern | 320 | (42.2) |

| Central | 158 | (20.8) | |

| Eastern | 132 | (17.4) | |

| Western | 95 | (12.5) | |

| Northern | 53 | (7.0) | |

| Age group | 18–24 | 205 | (27.0) |

| 25–34 | 247 | (32.6) | |

| 35–44 | 183 | (24.1) | |

| 45–54 | 90 | (11.9) | |

| ≥55 | 33 | (4.4) | |

| Education level | High school or less | 105 | (13.9) |

| University graduates | 534 | (70.4) | |

| Postgraduates | 119 | (15.7) | |

| Are you a health practitioner? | Yes | 277 | (36.5) |

| No | 481 | (63.5) | |

| Do you have chronic diseases? | Yes | 116 | (15.3) |

| No | 642 | (84.7) | |

| Have you taken Flu shot before? | Yes | 397 | (52.4) |

| No | 361 | (47.6) | |

| Are you willing to take the vaccine? | Yes | 484 | (63.9) |

| No | 274 | (36.1) | |

| How hesitant are you to take the vaccine? | Not hesitant at all | 241 | (31.8) |

| Not hesitant | 115 | (15.2) | |

| Neutral | 186 | (24.5) | |

| Hesitant | 77 | (10.2) | |

| Extremely hesitant | 139 | (18.3) |

Results from bivariate analysis show that those who report that they accept the COVID-19 vaccine were likely to be males, have obtained COVID-19 information only from MOH official accounts, previously had taken influenza vaccine, and believing that COVID-19 vaccine is effective against new COVID-19 variants. Also, those who think international traveling would require the uptake of COVID-19 vaccine demonstrated a high rate of acceptance toward the COVID-19 vaccine (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of the associations between multiple factors and the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine

| Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes |

No |

||

| n (%) | n (%) | P-value* | |

| Gender | .024 | ||

| Female | 177 (36.6) | 123 (44.9) | |

| Male | 307 (63.4) | 151 (55.1) | |

| Age group | .116 | ||

| 18–24 | 132 (27.3) | 73 (26.6) | |

| 25–34 | 166 (34.3) | 81 (29.6) | |

| 35–44 | 103 (21.3) | 80 (29.2) | |

| 45–54 | 63 (13.0) | 27 (9.9) | |

| ≥55 | 20 (4.1) | 13 (4.7) | |

| Education level | .310 | ||

| High school or less | 74 (15.3) | 31 (11.3) | |

| University graduates | 336 (69.4) | 198 (72.3) | |

| Postgraduates | 74 (15.3) | 45 (16.4) | |

| Are you a health practitioner? | .112 | ||

| Yes | 187 (38.6) | 90 (32.8) | |

| No | 297 (61.4) | 184 (67.2) | |

| Do you have chronic diseases? | .822 | ||

| Yes | 73 (15.1) | 43 (15.7) | |

| No | 411 (84.9) | 231 (84.3) | |

| Where do you get COVID 19 information from? | <.001 | ||

| Only from MOH official accounts | 226 (46.7) | 86 (31.4) | |

| Other sources besides MOH | 258 (53.3) | 188 (68.6) | |

| What are COVID 19 precautions? | .171 | ||

| Knowing all precautions | 383 (79.1) | 205 (74.8) | |

| Not knowing all precautions | 101 (20.9) | 69 (25.2) | |

| Do you think the vaccine work for the new COVID 19 variants? | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 428 (88.4) | 120 (43.8) | |

| No | 56 (11.6) | 154 (56.2) | |

| Have you ever taken Flu shot before? | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 284 (58.7) | 113 (41.2) | |

| No | 200 (41.3) | 161 (58.8) | |

| COVID-19 previous infection (self or relatives) | .106 | ||

| Yes, previously infected and have a relative previously infected as well. | 64 (13.2) | 48 (17.5) | |

| Yes, having a relative previously infected but not previously infected myself. | 308 (63.6) | 177 (64.6) | |

| Neither previously infected nor having a relative previously infected | 112 (23.1) | 49 (17.9) | |

| Would you take the vaccine if it is required to travel outside KSA? | |||

| Yes | 449 (92.8) | 107 (39.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 35 (7.2) | 167 (60.9) | |

* Fisher’s exact Chi-square.

Logistic regression results show that factors that appeared to be associated with the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine were gender, education, source of health information about COVID-19, perception of whether the COVID-19 vaccine works for other variants of the SARS-COV-2, previous uptake of the influenza vaccine, neither previously infected nor having a relative previously infected, and potential mandatory of vaccination in order to travel internationally (Table 3). That is, men were significantly more likely to accept to take the vaccine as compared to women (OR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.01–2.53); postgraduates were significantly less likely to accept to take the vaccine as compared to university level graduates (OR: 0.54; 95% CI: 030–0.96); those who have obtained COVID-19 information only from MOH official accounts were more likely to accept to take the vaccine as compared to those who have obtained COVID-19 information from other sources such as social media besides MOH official accounts (OR: 1.63; 95% CI: 1.07–2.49); those who believe that COVID-19 vaccine is effective against new COVID-19 variants were more likely to accept to take the vaccine as compared to those who do not believe so (OR: 7.24; 95% CI: 4.58–11.45); those who had ever taken the influenza vaccine were more likely to accept to take the vaccine as compared to those who had never taken the influenza vaccine (OR: 1.62; 95% CI: 1.07–2.47); the respondents who were never nor having relatives previously infected with COVID-19 were more likely to accept to take the vaccine as compared to those who were ever and having relatives previously infected with COVID-19 (OR: 2.76; 95% CI: 1.35–5.62). Furthermore, the potential mandatory of COVID-19 vaccine was significantly associated with the acceptance toward the vaccine (OR: 16.52; 95% CI: 10.23–26.68) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Influencing factors associated with the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine

| Variable | Accept to take COVID-19 vaccine |

|

|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P-value* | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | Ref | |

| Male | 1.60 (1.01, 2.53) | .046 |

| Age group | ||

| 18–24 | Ref | |

| 25–34 | 0.89 (0.50, 1.57) | .681 |

| 35–44 | 0.65 (0.34, 1.24) | .188 |

| 45–54 | 1.40 (0.63, 3.14) | .408 |

| ≥55 | 0.95 (0.30, 3.06) | .931 |

| Education level | ||

| High school or less | 1.29 (0.69, 2.41) | .416 |

| University graduates | Ref | |

| Postgraduates | 0.54 (0.30, 0.96) | .036 |

| Are you a health practitioner? | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.11 (0.70, 1.77) | .654 |

| Do you have chronic diseases? | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.26 (0.67, 2.36) | .478 |

| Where do you get COVID 19 information from? | ||

| Other sources besides MOH | Ref | |

| Only from MOH official accounts | 1.63 (1.07, 2.49) | .023 |

| What are COVID 19 precautions? | ||

| Not knowing all precautions | Ref | |

| Knowing all precautions | 1.08 (0.66, 1.78) | .761 |

| Do you think the vaccine work for the new COVID 19 variants? | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 7.24 (4.58, 11.45) | <.001 |

| Have you ever taken Flu shot before? | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.62 (1.07, 2.47) | .024 |

| COVID-19 previous infection (self or relatives) | ||

| Yes, previously infected and have a relative previously infected as well. | Ref | |

| No, not previously infected, but having a relative previously infected. | 1.27 (0.71, 2.30) | .422 |

| Neither previously infected nor having a relative previously infected. | 2.76 (1.35, 5.62) | .005 |

| Would you take the vaccine if it is required to travel outside KSA? | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 16.52 (10.23, 26.68) | <.001 |

* Logistic regression adjusting for all the covariates in the final model

Regarding the hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine, those with high school or less were more likely to be hesitant compared with university-level graduates (OR: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.17–3.24); those who have obtained COVID-19 information only from MOH official accounts were less likely to be hesitant compared with those who have obtained COVID-19 information from other sources such as social media besides from MOH official accounts (OR: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.40–0.78); those who believe that COVID-19 vaccine is effective against new COVID-19 variants were less likely to be hesitant compared with those who do not believe so (OR: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.18–0.42). Furthermore, those who would like to travel internationally would be less hesitant to take the vaccine compared with those who do not have the desire to travel internationally (OR: 0.19; 95% CI: 0.12–0.29) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Influencing factors associated with the hesitancy toward the COVID-19 vaccine

| Variable | Hesitant to take COVID-19 vaccine | |

|---|---|---|

| |

OR (95%CI) |

P-value* |

| Gender | ||

| Male | Ref | |

| Female | 1.17 (0.80, 1.70) | .431 |

| Age group | ||

| 18–24 | Ref | |

| 25–34 | 1.52 (0.95, 2.42) | .082 |

| 35–44 | 1.30 (0.76, 2.23) | .332 |

| 45–54 | 0.91 (0.48, 1.71) | .770 |

| ≥55 | 0.67 (0.26, 1.86) | .419 |

| Education level | ||

| High school or less | 1.95 (1.17, 3.24) | .010 |

| University graduates | Ref | |

| Postgraduates | 0.87 (0.54, 1.40) | .568 |

| Are you a health practitioner? | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.07 (0.73, 1.56) | .730 |

| Do you have chronic diseases? | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.12 (0.68, 1.84) | .659 |

| Where do you get COVID 19 information from? | ||

| Other sources besides MOH | Ref | |

| Only from MOH official accounts | 0.56 (0.40, 0.78) | .001 |

| What are COVID 19 precautions? | ||

| Not knowing all precautions | Ref | |

| Knowing all precautions | 0.91 (0.61, 1.37) | .655 |

| Do you think the vaccine work for the new COVID 19 variants? | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 0.27 (0.18, 0.42) | <.001 |

| Have you ever taken Flu shot before? | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 0.76 (0.54, 1.06) | .109 |

| COVID-19 personal history and experience | ||

| Yes, previously infected and have a relative previously infected as well. | Ref | |

| No, not previously infected, but having a relative previously infected. | 0.74 (0.45, 1.19) | .214 |

| Neither previously infected nor having a relative previously infected. | 0.74 (0.42, 1.30) | .299 |

| Would you take the vaccine if it is required to travel outside KSA? | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 0.19 (0.12, 0.29) | <.001 |

* Logistic regression adjusting for all the covariates in the final model.

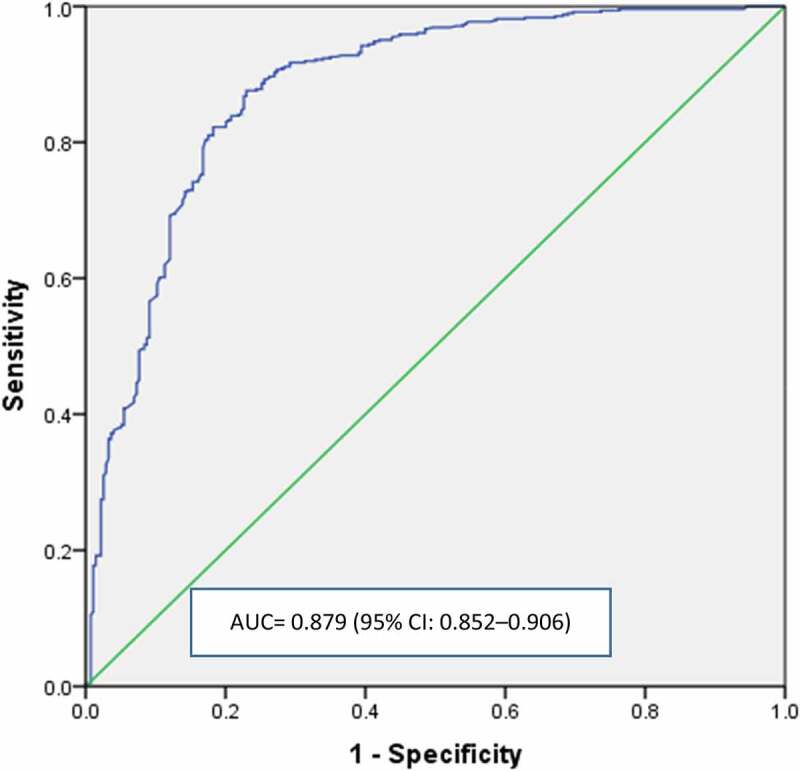

Finally, Hosmer–Lemeshow test was not significant, which suggested that the models we chose fit the data. Also, the survey items used in the logistic regression to predict the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine yielded AUC = 0.879 (95% CI: 0.852–0.906) using ROC analysis, indicating that the predictivity of the model used is very good (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of the predictivity of the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine using several items of the questionnaire as predictors

Discussion

This study provides insights on the factors influencing the acceptance and hesitancy toward the COVD-19 vaccine. The factors that were significantly associated with acceptance and/or hesitancy included gender, education, source of health information about COVID-19, perception of whether the COVID-19 vaccine works for other variants of the SARS-COV-2, previous uptake of the influenza vaccine, neither previously infected nor having a relative previously infected, and potential mandatory of vaccination in order to travel internationally.

In the present study, it was evident that men were more likely to accept the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine than women, which has been documented in several previous studies.37–39 Kose et al. conducted a cross-sectional study in Izmir, which involved 1138 participants in assessing the factors of accepting COVID-19 vaccination.38 Despite that 27.5% of the respondents were men, the study’s findings conform to this research, reporting men to be more likely to accept the vaccine.38

In addition, the source of COVID-19 information was a strong predictor. Those who seek the information only from official MOH sources have a higher desire to take the vaccine compared to those who receive information from social media and non-official accounts. Thus, social media contain lots of misinformation regarding the pandemic and can increase the hesitance toward the effectiveness and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine.40–42 Also, the effect of the source of information in this study was reflected on those who believe that the vaccine is effective against the new emerging COVID-19 variants.43–45

Furthermore, those who have previously taken the influenza vaccine show high acceptance. This corresponds to findings from several studies.37–39,46,47 Such a predictor can reflect the general acceptance of vaccines as preventive measures. Those who abstain from taking the seasonal influenza vaccine may suggest a need for enhanced educational programs emphasizing the positive public health impact of vaccinations against infectious diseases.

Additionally, the study found those who were never infected with COVID-19 nor have a relative infected were more likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. This can be attributable to the potential fear and the risk of the infection, unlike those who have previously been infected, who believe they are already immune, or those who have seen relatives infected with only mild symptoms without severe complications.

Another significant predictor of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in our study was the potential mandatory vaccination requirement for travel internationally. The Ministry of Health provides those who completed the two-doses of the vaccine a health passport,16 which has also been applied by the Danish government.48 Although one may question the ethics behind forcing individuals to take the vaccine to travel,49,50 vaccine mandatory for traveling purposes has proven to have beneficial impacts as preventive measures against infectious diseases worldwide.51–54

This present study included several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the factors – other than sociodemographics – influencing vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia. Besides, this study included all provinces of Saudi Arabia. Also, the sample size is considered sufficient as it yields a margin of error of less than 4%. Moreover, the model used in this analysis showed a very good predictive performance, indicating that the findings were statistically reliable. On the other hand, the study has several limitations, which are mainly related to the measurement tool used. One prominent limitation was that the questionnaire had not been validated prior to the use for this study. However, its development has gone through multiple revisions by experts and had been pretested face-to-face. Another limitation was not collecting the nationality of respondents. However, since it is a global pandemic and all Saudi Arabia residents were under the same COVID-19 healthcare measurements, the nationality factor did not merit being an influential factor. Also, such type of surveys is prone to measurement error, particularly misclassification. However, we believe the misclassification is non-differential, and it would only drive the magnitude of the prediction toward the null.55 Furthermore, the survey was in the Arabic language; hence, non-Arabic speakers were not included in the sampling frame. Also, the tool used did not provide a response rate since it was distributed through social media; however, the margin of error was reduced by the number of respondents included in the analysis. Finally, the respondents were only those who possess smartphones or have internet access due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the difficulty of obtaining paper surveys, which makes those without smartphones or internet access eliminated from the chance of being selected during sampling. Nonetheless, according to the General Authority for Statistics in Saudi Arabia, over 90% of people in Saudi Arabia have access to the internet or use smartphones;56 thus, the majority of the population would be represented by our sample and such a bias – if occurred – would be minimal.

Implications

This study provides insightful information about factors influencing the acceptance and hesitancy of the COVID-19 vaccine beyond just sociodemographic factors and perceptions that have been previously reported.28,57 The Saudi government, particularly MOH, should address the misinformation spreading in social media, doubting the effectiveness and the safety of COVID-19 vaccine. Also, travel regulations and new policies could be implemented – without violating individuals’ liberties – to encourage the public to vaccinate. Finally, the positive association between the previous influenza uptake and the desire to accept the vaccine may suggest that some individuals in the population refuse the general concept of vaccination. Therefore, extensive educational programs through TV and social media are mandatory to emphasize the importance of vaccination against infectious diseases in general as one of the greatest public health preventive measures throughout history.

Conclusion

Our study provides an insight toward factors – other than the sociodemographics – influencing the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine in Saudi Arabia. These results may help the Saudi government and policymakers to address the issues of misinformation spreading in social media. Also, some measures related to travel regulations may be implemented to improve the vaccine’s acceptance rate. Finally, advanced educational health programs are needed to increase the acceptance of vaccinations against infectious diseases, particularly against COVID-19 during the current pandemic.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude and thank all the participants in this study. We also would like to thank our colleagues from multiple institutes across the country for their help in distributing the survey.

Appendix A.

- Gender Please choose one answer.

- Male

- Female

- Age Please choose one answer.

- 18-24

- 25-34

- 35-44

- 45-54

- 55 or more

- Level of education Please choose one answer.

- Middle school or less

- High school

- Graduate

- Postgraduate

- Which Saudi province do you live in? Please choose one answer.

- Northern

- Southern

- Central

- Eastern

- Western

- Do you work in the health sector? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- Are you a health practitioner? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- Do you suffer from chronic diseases? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- Do you have any of the following conditions? Please check all that apply.

- None

- Heart condition

- Diabetes

- Blood pressure

- Other

- Have you been diagnosed with COVID-19 and confirmed by PCR testing? Please choose one answer.

- Yes, but was not hospitalized

- Yes, and was admitted to hospital

- Yes, and I was placed in ICU

- No, I tested negative

- Never been tested.

- Has any of your relatives been diagnosed with COVID-19? Please check all that apply.

- Yes, but was not hospitalized

- Yes, and was admitted to hospital

- Yes, and was placed in ICU

- Yes, and passed away

- No

- How do you assess your level of knowledge regarding the signs and symptoms of COVID-19? Please choose one answer.

- Excellent

- Very well

- Well

- Acceptable

- Weak

- From what sources do you get your information regarding COVID-19? Please check all that apply.

- Memos from work

- Television

- Ministry of Health via official accounts

- Social media platforms

- Talking to people

- Based on your information, which of the following is a COVID-19 symptom? Please check all that apply.

- Coughing

- Shortness of breath

- Loss of taste and smell

- Which of the following is COVID-19 precautions? Please check all that apply.

- The use of facemask

- Hand washing with soap and water

- The use of sanitizers

- Do you think the medications used to treat COVID-19 are effective? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- Did you hear about the COVID-19 vaccination? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- How many doses are recommended for the COVID-19 vaccine being used by the Ministry of Health? Please choose one answer.

- 1

- 2

- 3

- I don’t know

- Are you going to take the COVID-19 vaccine when it is available in your region? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- Did you register to take the vaccine via Sehty Application? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

To what degree are you hesitant about getting the vaccine? Please choose one answer.

Very hesitant 1 2 3 4 5 Not at all hesitant

- Would you recommend that those close to you register for vaccination? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- Would you take the vaccine if it is related to international travel? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- Have you ever taken the seasonal flu vaccine? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- When was the last time you got the seasonal flu shot? Please choose one answer.

- During the last 3 months

- 3-6 months ago

- 6-12 months ago

- Over a year ago

- I have never had a seasonal flu shot

- Are you or were you previously committed to the vaccination schedule for your children? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- I don’t have children

- Has the pandemic affected your attendance at work or study? Please choose one answer.

- Yes, and I work / study remotely most of the time

- No, as I have to come to work / study place almost daily

- I work in freelance work and partially affected

- I work in freelance work and fully affected

- I don’t work

- Will the government or private employer force you to take the vaccine? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- Maybe

- I don’t work

- Do you think that the vaccine is effective against the COVID-19 new variants? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

- Have you ever filled out this same questionnaire before this time? Please choose one answer.

- Yes

- No

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee at King Khalid University with approval number: [(ECM#2020-197)—(HAPO-06-B-001)]. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. They were assured that their participation is voluntary, and all responses would be anonymous and confidential. In addition, the participants’ answers would be used for scientific research only.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center . COVID-19 map. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- 2.Yen M-Y, Schwartz J, Chen S-Y, King C-C, Yang G-Y, Hsueh P-R.. Interrupting COVID-19 transmission by implementing enhanced traffic control bundling: implications for global prevention and control efforts. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:377–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaur SP, Gupta V.. COVID-19 vaccine: a comprehensive status report. Virus Res. 2020;288:198114. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGill COVID19 Vaccine Tracker Team . COVID19 vaccine tracker. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://covid19.trackvaccines.org/.

- 5.BBC NEWS . Covid-19 vaccine: first person receives Pfizer jab in UK. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-55227325#:~:text=A%20UK%20grandmother%20has%20become,%22best%20early%20birthday%20present%22.

- 6.Tanne JH. Covid-19: FDA panel votes to approve Pfizer BioNTech vaccine. BMJ2020;371:m4799. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierri F, Pavanetto S, Brambilla M, Ceri S. VaccinItaly: monitoring Italian conversations around vaccines on Twitter. arXiv Preprint arXiv. 2101.03757. 2021. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.03757v3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health . COVID-19 dashboard. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://covid19.moh.gov.sa/.

- 9.Saudi Press Agency . SFDA approves registration of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2166947.

- 10.Saudi Press Agency . Health minister launches a vaccination campaign against Coronavirus, free of charge for citizens and residents. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2170026.

- 11.Saudi Press Agency . MOH announces starting registration of taking COVID-19 vaccine for citizens and residents. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2168246.

- 12.Saudi Press Agency . MoH: registration for taking COVID-19 vaccine via Sehaty App, receiving a date within 24 hours. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2175202.

- 13.Saudi Press Agency . COVID-19 Follow-up Committee Holds Daily Briefing. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2074704.

- 14.Saudi Press Agency . HRH crown prince receives 1st dose of coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccine. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2172364.

- 15.Reuters . Saudi king receives first dose of a coronavirus vaccine -SPA. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-saudi-king-idUSKBN29D2PM.

- 16.Saudi Press Agency . Ministry of health and SDAIA launch “Medical Passport” Via (Tawakkalna). [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2176874.

- 17.Fridman A, Gershon R, Gneez A. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: a longitudinal study. PloS One. 2021;16:e0250123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bish A, Yardley L, Nicoll A, Michie S. Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2011;29:6472–84. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cordina M, Lauri MA. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, vaccine hesitancy and intention to take the vaccine. Pharmacy Practice (Granada). 2021;19:2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9:160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreps S, Prasad S, Brownstein JS, Hswen Y, Garibaldi BT, Zhang B, Kriner DL. Factors associated with US adults’ likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3:e2025594–e2025594. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ditekemena JD, Nkamba DM, Mavoko AM, Hypolite M, Fodjo JNS, Luhata C, Obimpeh M, Hees SV, Nachega JB, Colebunders R. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccines. 2021;9:153. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saied SM, Saied EM, Kabbash IA, Abdo SAE. Vaccine hesitancy: beliefs and barriers associated with COVID‐19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. J Med Virol. 2021;93:4280–91. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan YH, Mallhi TH, Alotaibi NH, Alzarea AI, Alanazi AS, Tanveer N, Hashmi FK. Threat of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Pakistan: the need for measures to neutralize misleading narratives. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:603–04. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almaghaslah D, Alsayari A, Kandasamy G, Rajalakshimi Vasudevan COVID-19. Vaccine hesitancy among young adults in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional web-based study. Vaccines. 2021;9:330. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machida M, Nakamura I, Kojima T, Saito R, Nakaya T, Hanibuchi T, Takamiya T, Odagiri Y, Fukushima N, Kikuchi H. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines. 2021;9:210. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harapan H, Wagner AL, Yufika A, Winardi W, Anwar S, Gan AK, Setiawan AM, Rajamoorthy Y, Sofyan H, Mudatsir M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in southeast Asia: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Front Public Health. 2020;8. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Mohaithef M, Padhi BK. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1657. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S276771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadler GR, Lee H, Lim RS, Fullerton J. Recruitment of hard‐to‐reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nurs Health Sci. 2010;12:369–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan TP. Sample size determination and power. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Upton GJG. Fisher’s exact test. J R Stat Soc. 1992;155:395–402. doi: 10.2307/2982890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts G, Rao NK, Kumar S. Logistic regression analysis of sample survey data. Biometrika. 1987;74:1–12. doi: 10.1093/biomet/74.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lemeshow SA, Hosmer JR. Logistic regression. In: Armitage P, Colton T, editors. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. Vol 2. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2005. p. 2870–2888. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fagerland MW, Hosmer DW. A generalized Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for multinomial logistic regression models. Stata J. 2012;12:447–53. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1201200307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanley JA. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) methodology: the state of the art. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1989;29:307–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mansfield ER, Helms BP. Detecting multicollinearity. Am Stat. 1982;36:158–60. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gagneux-Brunon A, Detoc M, Bruel S, Tardy B, Rozaire O, Frappe P. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: a cross sectional survey. J Hosp Infect. 2021;108:168–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.020. PMID: 33259883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kose S, Mandiracioglu A, Sahin S, Kaynar T, Karbus O, Ozbel Y. Vaccine hesitancy of the COVID-19 by health care personnel. Int J Clin Pract. 2021; 75:e13917. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines. 2020;8:482. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8030482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bell S, Clarke R, Mounier-Jack S, Walker JL, Paterson P. Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine. 2020;38:7789–98. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loomba S, de Figueiredo A, Piatek, SJ. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat Hum Behav5. 2021:337–348. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson SL, Wiysonge C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5:e004206. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahase E. Covid-19: What new variants are emerging and how are they being investigated?. BMJ. 2021;372:n158. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n158. PMID:33462092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wise J. Covid-19: new coronavirus variant is identified in UK. Br Med J Publ Group. 2020;m4857. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saudi Press Agency . Minister of health reassures the public: variant mutant strain not more infectious than the current coronavirus, vaccines deemed effective against it. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2171215.

- 46.Fu C, Wei Z, Pei S, Li S, Sun X, Liu P. Acceptance and preference for COVID-19 vaccination in health-care workers (HCWs). medRxiv. Preprint. Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.09.20060103v1. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.09.20060103v1. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grech V, Gauci C, Agius S. Vaccine hesitancy among Maltese healthcare workers toward influenza and novel COVID-19 vaccination. Early Hum Dev. 2020:105213. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reuters . Denmark developing digital COVID-19 ‘vaccine passport’. [accessed 2021 February 4]. https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-denmark-travel/denmark-developing-digital-covid-19-vaccine-passport-idUSL8N2JJ20U.

- 49.Pennings S, Symons X. Persuasion, not coercion or incentivisation, is the best means of promoting COVID-19 vaccination. J Med Ethics. 2021;medethics-2020-107076. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-107076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Voo TC, Clapham H, Tam CC. Ethical implementation of immunity Passports during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:715–18. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I, Jezek Z, Ladnyi ID. Developments in vaccination and control. In: Smallpox and its Eradication Chapter 7. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1988. p. 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Tigerstrom BJ, Halabi SF, Wilson KR. The International Health Regulations (2005) and the re-establishment of international travel amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. J Travel Med. 2020;27:taaa127. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.World Health Organization . Statement on the sixth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Geneva. 15;2021January:2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54..World Health Organization . 2008. International health regulations (2005). Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Copeland KT, Checkoway H, McMichael AJ, Holbrook RH. Bias due to misclassification in the estimation of relative risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105:488–95. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.General Authority for statistics . Bulletin of Individuals and Households’ ICT Access and Usage Survey. 2019. [accessed 2021 February 4]. https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/952.

- 57.Magadmi RM, Kamel FO. Beliefs and Barriers Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination Among the General Population in Saudi Arabia. Research Square; 2020. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-48955/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.