ABSTRACT

Vaccination is the most effective and cost-efficient approach to protect both individual and community health. Decreased vaccination rates have been reported in many countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, we compared the vaccination rates of the current year with those of the same period of 2019 in Ankara and presented the physicians’ thoughts about effects of COVID-19 pandemic on vaccinations in Turkey. An online survey was sent to family practitioners, pediatricians, and pediatric infectious disease specialists to ascertain their thoughts on vaccination during the pandemic. A majority of family practitioners stated that, despite hesitations, families brought their children for vaccination. They noted that vaccination should be emphasized, physicians should be supported by health authorities, and all related media and social media channels should be used to promote maintaining vaccinations. In contrast, pediatricians and pediatric infectious disease specialists were of the opinion that families were expressing greater hesitation and would not bring their children for vaccination. Vaccination rates in Ankara have decreased 2–5% during the pandemic, and the greatest decrease was observed for vaccines administered after 18 months of age. Outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases can threaten community health worldwide. Thus, vaccinations must continue, and effective regulations and recommendations need to be implemented by healthcare authorities to promote it.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, pandemic, vaccination, vaccine hesitancy

Introduction

The first cases of COVID-19 were detected in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and a new coronavirus was announced as the pathogenic microorganism. The virus, later named SARS-CoV-2, continued to spread from person to person and became a global pandemic within a few weeks. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in tens of millions of infections and more than one million deaths worldwide.1

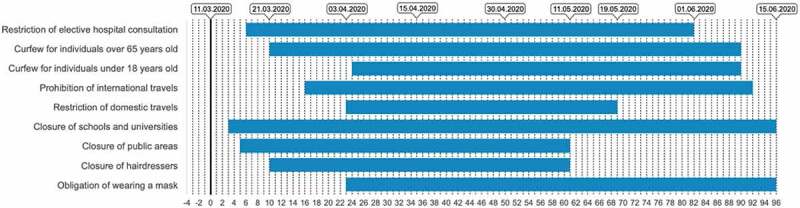

Different approaches have been implemented in various parts of the world to control the pandemic. Terminating face-to-face learning in schools and universities; shutting down communal spaces, such as restaurants, coffee shops, and shopping centers; postponing community events; and travel prohibitions were some of the measures taken in Turkey to bring the spread of the virus under control. In addition, isolating individuals at home and postponing routine follow-ups and elective hospital consultations were recommended. A curfew for individuals under 20 years of age and over 65 of age was commenced, but a long-term lockdown was never initiated for the general public (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Some of the measures taken in Turkey to control of COVID-19 pandemic.2–10

The majority of hospitals treated COVID-19 patients, and an interruption of protective healthcare services has occurred in most of the countries that experienced rapid increases in the number of cases. In addition, anxiety regarding COVID-19 transmission during hospital admissions and prohibitions implemented by the countries for pandemic control may contribute to the decline in accessing to this services. Thus, some setbacks in vaccination, as a protective healthcare service, have occurred in many countries during the pandemic.11,12 Following the declaration of a national emergency in the United States, a drastic decrease in the rate of vaccine administration, especially those given after the age of 2 years, was observed.13

Due to the prevention and restriction approaches applied for controlling the spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the early period of the pandemic in Turkey, there may be some changes in physicians’ and parents’ attitudes regarding routine childhood vaccination services. As in the U.S., vaccination rates may have been affected by these changes in Turkey.

A comprehensive vaccination program is carried out in Turkey for children, with 10 vaccines administered before the age of 2 years, including vaccines against hepatitis B (HBV), conjugated pneumococcal (CPV), diphtheria-tetanus toxoids-acellular pertussis (DTaP), inactivated polio (IPV), Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), oral polio (OPV), BCG, varicella zoster (VZV), measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), and hepatitis A (HAV).14 All of the vaccines in the schedule are free for citizens and accessible via family health services. Family practitioners are responsible for implementing and following routine childhood vaccinations in Turkey.

According to the 2019 data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TSI), the overall population of Turkey is approximately 83.1 million, with approximately 5.6 million in the capital and second largest city Ankara. The number of live births in Turkey in 2019 was approximately 1.1 million (5.7% in Ankara).15 Thus, the vaccination status in Ankara may reflect the country in general.

This cross-sectional study was designed to ascertain the perspectives of family practitioners, pediatricians, and pediatric infectious disease specialists in Turkey on the continuity of vaccination, attitude of parents about vaccination, and needs/recommendations for preventing setbacks in vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also determined the change in vaccination rates in Ankara during the pandemic by comparing the rate thus far in 2020 to the previous year.

Methods

Family practitioners and pediatricians are the major types of physicians who deal with child health and diseases in general, and pediatric infectious disease specialists have made great contributions to the management of pediatric patients with COVID-19 during the pandemic. Therefore, we selected these groups of physicians as the study group. A three-question survey regarding vaccination in Turkey during the pandemic was conducted with the physicians on a volunteer basis between April 1 and 7, 2020. The first COVID-19 case in Turkey had been detected on March 11, 2020, and the highest number of cases was determined on April 20, 2020. The survey was filled out by family practitioners and pediatricians during their participation on an education/training webpage prior to webcast training, which was carried out on separate occasions for the two groups. The same survey was filled out by pediatric infectious disease specialists on WhatsApp on the same day, but in different time frames, by asking each question individually to collect the answers. No personal data were requested from the participating physicians.

A total of 2860 family practitioners, 1908 pediatricians, and 70 pediatric infectious disease specialists participated in the study, representing approximately 10% of family practitioners, 25% of pediatricians, and 80% of pediatric infectious disease specialists in the country.

Fundamentally, it is the responsibility of family practitioners to implement and follow routine childhood vaccinations in Turkey. Therefore, the first question of the survey for family practitioners was, “Do you recommend routine vaccination to your patients during the COVID-19 pandemic?” Pediatricians and pediatric infectious disease specialists were asked, “Do you think that there have been setbacks in routine vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic?” The second question was directed to all physicians: “What was the attitude of your patients regarding routine vaccination during the pandemic?” They had three options for the response: “they do not want to come for vaccination due to the pandemic,” “there is no problem in vaccination during the pandemic,” and “other.” The third question was also directed to all physicians: “What are your needs/recommendations for preventing setbacks in routine vaccination during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic?” They had five options for the response: “preparing a national guideline on routine vaccination services during the COVID-19 pandemic,” “the importance of the continuation of childhood vaccines could be emphasized through written and visual media and social media with short films (public service ad) aimed at informing the public,” “designating special service areas reserved for immunization services,” “all of these,” and “no need/recommendation.” Questions on the survey are found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questions of the survey collecting opinions of physicians about vaccination in Turkey during the pandemic and distribution of the answers

| Family practitioners(%) | Pediatricians(%) | Pediatric infectious diseases specialists(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you recommend routine vaccination to your patients during the COVID-19 pandemic? -Yes -No Do you think that there have been setbacks in routine vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic? -Yes -No |

91.6 8.4 (n = 2860) |

73.9 25.4 (n = 1908) |

94.2 5.8 (n = 70) |

| Which was the attitude of your patients regarding the routine vaccination during the pandemic?* -They do not want to come for vaccination due to the pandemic. -There is no problem in vaccination during the pandemic. -other than these |

38.3 57.0 4.5 (n = 2580) |

74.4 10.5 7.6 (n = 1644) |

65.8 11.4 12.8 (n = 70) |

| What are your needs/recommendations for the prevention of setbacks in routine vaccination during the course of COVID-19 pandemic? -preparing a national guideline on routine vaccination services during COVID-19 pandemic -the importance of the continuation of childhood vaccines could be emphasized through written and visual media and social media with short films (public service ad) aimed at informing the public -designating special service areas reserved for immunization services -all of these -no need/recommendation |

4.0 21.7 10.8 62.5 2.7 (n = 1670) |

5.5 20.7 6.6 57.7 5.1 (n = 1620) |

5.7 27.1 30.0 37.2 0.0 (n = 70) |

* The chi-square statistic with Yates correction is 42.0022. The p-value is < 0.00001. Significant at p < .05 for family physician with pediatrician

To assess changes in vaccination rates, the vaccination rates in Ankara in March, April, and May 2020 were compared to the same period in 2019. Data were obtained from the vaccination verification and implementation records of Ankara Provincial Health Directorate.

Results

A summary of the participants’ answers to the survey questions is given in Table 1. For the first question, the majority of family practitioners stated that they recommended vaccination. Nevertheless, the majority of pediatricians and pediatric infectious disease specialists thought there were setbacks in routine vaccination.

In terms of the question related to patients’ attitudes toward routine vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic, more than half of family practitioners stated there were no setbacks, and approximately one-third indicated that parents hesitated about bringing their children for vaccinations. More than half of the pediatricians and pediatric infectious disease specialists indicated that parents did not want to bring their children for vaccination due to the pandemic.

Only one-tenth of pediatricians and pediatric infectious disease specialists emphasized that families gave importance to vaccination and would ensure that their children would receive vaccines under any circumstances. One-third to one-half of the physicians’ felt that all of the recommendations would be useful to prevent setbacks in routine vaccination.

Table 2 shows the vaccination rates for children under 24 months of age during March, April, and May of 2020 and the same period in 2019. OPV dose 2, HAV dose 1, and DAPT-IPV-HIB booster were the vaccines with the lowest administration rates, which occurred in May 2020 (Table 2). All of them belong to the 18th month routine vaccination calendar. In terms of changes in administration rates, a 6.9% decrease in HAV dose 1 and 6.8% decrease in OPV dose 2 and the DaPT-IPV-HIB booster in May 2020 compare to May 2019 were the most prominent changes (Figure 2). Based on these findings, the answers of the family practitioners to the first and second questions regarding continuity of vaccination and vaccine hesitancy among parents during the pandemic reflect estimates of the actual vaccination rates in Ankara.

Table 2.

Vaccination rates of children under the age of 24 months during March, April, and May 2020 in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic and those of the same period of the year 2019 in Ankara, Turkey

| 2019% |

2020% |

Percent change % |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of Vaccine (age of vaccination) | March | April | May | March | April | May | March | April | May |

| Hepatitis B Dose 1 (birth) | 98.6 | 98.5 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 96.2 | −0.8 | −0.7 | −1.6 |

| Hepatitis B Dose 2 (1. month) | 98.5 | 97.8 | 98.5 | 98.5 | 98 | 96.8 | 0 | +0.2 | −1.7 |

| Hepatitis B Dose 3 (6. month) | 98.8 | 98.5 | 98.8 | 98.2 | 98.5 | 94.5 | −0.6 | 0 | −4.3 |

| BCG (2. month) | 98.8 | 98.7 | 98.8 | 98.1 | 98.3 | 96.9 | −0.7 | −0.4 | −1.9 |

| DAPT IPV HIB dose 1 (2. month) | 98.8 | 98.6 | 98.5 | 98.3 | 98.6 | 97.3 | −0.5 | 0 | −1.2 |

| DAPT IPV HIB dose 2 (4. month) | 98.9 | 98.6 | 98.7 | 98.1 | 98.3 | 96.1 | −0.8 | −0.3 | −2.6 |

| DAPT IPV HIB dose 3 (6. month) | 98.8 | 98.6 | 98.6 | 98.1 | 98.3 | 94.6 | −0.7 | −0.3 | −4.0 |

| DAPT IPV HIB booster (18. month) | 98.3 | 98.1 | 98.3 | 97.8 | 97.5 | 91.5 | −0.5 | −0.6 | −6.8 |

| CPV dose 1 (2. month) | 98.8 | 98.7 | 98.5 | 98.3 | 98.6 | 97.4 | −0.5 | −0.1 | −1.1 |

| CPV dose 2 (4. month) | 98.9 | 98.6 | 98.7 | 98.1 | 98.4 | 96.2 | −0.8 | −0.2 | −2.5 |

| CPV booster (12. month) | 98.5 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 97.6 | 97.7 | 94.6 | −0.9 | −0.7 | −3.8 |

| OPV dose 1 (6. month) | 98.1 | 98.3 | 94.7 | 98.1 | 98.3 | 94.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| OPV dose 2 (18. month) | 97.6 | 97.9 | 98.2 | 97.7 | 97.4 | 91.4 | +0.1 | −0.5 | −6.8 |

| MMR (12. month) | 98.5 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 97.6 | 97.6 | 94.5 | −0.9 | −0.8 | −3.9 |

| Varicella (12. month) | 97.8 | 97.9 | 98 | 97.2 | 97.3 | 94.3 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −3.7 |

| HAV dose 1 (18. month) | 98.3 | 98.3 | 98.3 | 97.8 | 97.6 | 91.4 | −0.5 | −0.7 | −6.9 |

| HAV dose 2 (24. month) | 98.5 | 98.3 | 97.9 | 97.5 | 97.4 | 92.2 | −1.0 | −0.9 | −5.7 |

Figure 2.

Mean vaccination ratios of children under the age of 24 months during March, April, May 2019 and 2020 in Ankara, Turkey

Discussion

Though most family practitioners stated that they recommended routine childhood vaccination during the pandemic period, pediatricians and pediatric infectious disease specialists indicated that they expected a setback in vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic. Each vaccine we evaluated had an administration rate >90%. Family practitioners implement and follow routine childhood vaccinations in Turkey. In the event of setbacks, district health directorates must be informed of a justifiable reason for the setback. In terms of non-medical or mandatory reasons, a deduction in the physicians’ salary is enforced. Therefore, family practitioners generally follow and implement childhood vaccines strictly. As a result, their answers to the first question reflected the real vaccination rates in Ankara. Pediatric infectious disease specialists and pediatricians may be much more restless about the possible negative effects of the pandemic. Limited information on approaches to promoting vaccination during the pandemic may have increased their restlessness. All the mothers has to be followed up by at least 7 times during pregnancy and there is a home visit within the first week of birth. And then, in first month at least 3 more visit must be performed. So family physician has so close contact with the mother. And there is budget performence system for routine vaccination for family physician. The trust between families and family practitioners may contribute to the family practitioners not having a problem with recommending vaccination.

The vaccination rates in Ankara demonstrate that, despite the hesitations noted by some of the physicians, parents brought their children to get vaccinated. However, the answers from the pediatricians and pediatric infectious disease specialists show that even field specialists who should recommend vaccination and ease the minds of the families with hesitations have hesitations and differing opinions. Vaccine hesitancy among health care providers exists around the world, mostly due to safety issues and the level of awareness of why vaccines are needed.16 The risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 during a routine vaccination visit may have created vaccine hesitation among physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Physicians are still the most trusted advisor and influencer of vaccination behavior in patients.16,17 This situation emphasizes the importance of education/training and necessitates that the subject matter be addressed by health authorities and related associations to promote the role of physicians and health care providers in vaccination.

When the months March and April were compared between 2020 and 2019, the difference between vaccination rates was 0.4–1%. When May was compared between the two years, it was 5.7–6.9% for the second dosage of OPV, first dosage of HAV, second dosage of HAV, and booster for DaPT IPV HIB. These vaccines are administered to children aged 18 and 24 months in Turkey. The decrease in vaccination rates for children in this age range is much more significant than in the younger age groups.

Though it is evident that families in Ankara were more attentive to the implementation of vaccinations in infancy, the slight decrease observed in the implementation of the vaccines given at 18 months suggest that these vaccines were considered to be postponed to a later time. The World Health Organization (WHO) pointed out more than 30 measles vaccination campaigns were postponed during the pandemic period,18 and postponing vaccinations creates a risk for outbreaks in the future. Although the vaccination rate currently remains high in Turkey, education targeting both parents and health care providers is needed to improve future numbers as the pandemic continues.

A report from the US regarding the impact of the pandemic on pediatric vaccination noted a substantial decrease in vaccinations between January 6, 2020, and April 19, 2020, compared to the same period in 2019. The difference between the aforementioned periods surpassed 3 million dosages. Following the “national emergency” announcement on March 16, 2020, a decrease in all childhood vaccinations, specifically those implemented between 2 and 18 years of age, was observed.13 A study in the UK compared the first 17 weeks of 2020 and 2019, finding a 6.7% and 19.8% decrease in hexavalent and MMR vaccines, respectively, 3 weeks after nationwide social isolation was announced.19 A similar trend was seen in Turkey as in the USA and UK. The first COVID-19 case in Turkey was reported on March 11, 2020, with a rapid increase in the number of cases in April. The daily new number of cases peaked with 5138 cases on April 11, 2020. The daily new number of cases dropped below 1000 on May 20, 2020.20 A more evident decrease was observed in vaccination rates in May, following the high number of cases in April.

Globally, 80 million children under the age of 1 years in 68 countries are at risk due to the setbacks in vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic.21 Upon observing the decrease in vaccination rates during the pandemic, many countries have taken local precautions. International institutions have published recommendations and guidelines. In Turkey, the Ministry of Health issued vaccine implementation recommendations for the pandemic on April 20, 2020, and continuing vaccinations has previously been recommended by webcasts. The rapid decrease in vaccinations in the first months of the pandemic in the US changed its course toward a slight increase as of the end of March, with regulations and recommendations made by national healthcare programs regarding the continuation of vaccine implementation during the pandemic.13

UNICEF has issued an informative note to parents recommending the continuation of routine childhood vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic,22 and the WHO has published a guideline related to vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic. The WHO recommends not delaying routine childhood vaccinations, if possible, making a catch-up plan as quickly as possible in countries with a rapid increase in the number of COVID-19 cases and in the event of conditions necessitating the suspension of vaccination programs. Other suggestions are for the healthcare personnel to wear personal protective equipment while administering the vaccine, formulating a daily schedule for administering vaccinations, maintaining social distance, decreasing the number of applications by combining vaccination applications with other protective healthcare services, using the outdoors, if possible, continuing vaccinations with home visits, and giving priority to those with underlying diseases.11 Most physicians agreed that a national guideline could be prepared for routine vaccination services during the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of continuing childhood vaccines could be emphasized through written and visual media and social media with short films (public service ad) aimed at informing the public, and special service areas should be reserved for immunization services. In Africa, an estimated 101 child deaths can be prevented by the routine vaccination schedule against one child death due to SARS-CoV-2 acquired during hospital referral for routine vaccination.23 Therefore, these recommendations should be considered by nationally and internationally authorized healthcare institutions to continue vaccine implementation during the pandemic.

Unvaccinated children can be at risk of diseases, such as measles, an outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases during this period of time when social distancing and isolation in houses have started to decrease. Both parents and clinicians must be reminded of the severity of vaccine-preventable diseases and the fact that children should be protected against these severe diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. [accessed 2020 Jun 28]. https://covid19.who.int/.

- 2.[accessed 2020 May 14]. https://www.saglik.gov.tr/TR,63724/fahrettin-koca-koronaviruse-iliskin-aciklamalar-yapti.html.

- 3.[accessed 2020 May 14]. https://www.saglik.gov.tr/TR,64414/cumhurbaskanligi-kulliyesinde-koronavirus-zirvesi-duzenlendi.html.

- 4.[accessed 2020 May 14]. https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/81-il-valiligine-koronavirus-tedbirleri-konulu-ek-genelge-gonderildi.

- 5.[accessed 2020 May 14]. https://www.iletisim.gov.tr/turkce/haberler/detay/altun-koronaviruse-karsi-amansiz-bir-mucadele-yurutuyoruz.

- 6.[accessed 2020 May 14]. https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/bakanligimiz-81-il-valiligine-koronavirus-tedbirleri-konulu-ek-bir-genelge-daha-gonderdi.

- 7.[accessed 2020 May 14]. http://web.shgm.gov.tr/tr/genel-duyurular/6344-covid-19-tedbirleri-kapsaminda-27-mart-tarihli-ucus-kisitlamalari-hakkinda.

- 8.[accessed 2020 May 14]. https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/sehir-giriscikis-tebirleri-ve-yas-sinirlamasi.

- 9.[accessed 2020 May 14]. https://www.saglik.gov.tr/TR,63434/saglik-bakani-koca-koronaviruse-iliskin-aciklama-yapti.html.

- 10.[accessed 2020 May 14]. https://www.saglik.gov.tr/TR,64493/saglik-bakani-koca-koronaviruse-iliskin-son-durumu-degerlendirdi.html.

- 11.Guiding principles for immunization activities during the COVID-19 pandemic interim guidance. World Health Organization; 2020March26[accessed 2020 Jun 28]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331590/WHO-2019-nCoV-immunization_services-2020.1-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Immunization in the context of COVID-19 pandemic Frequently asked questions. World Health Organization; 2020April16[accessed 2020 Jun 28]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331818/WHO-2019-nCoV-immunization_services-FAQ-2020.1-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santoli JM, Lindley MC, DeSilva MB, Daley MF, Galloway L, Gee J, Glover M, Herring B, Kang Y.. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Pediatric Vaccine Ordering and Administration — united States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020May15;69(19):591–93. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health Vaccination Schedule of Childhood. [accessed 2020 Oct 10]. https://asi.saglik.gov.tr/asi-takvimi/.

- 15.TÜİK Gösterge Uygulaması. [accessed 2020 Jun 25]. https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/ilgosterge/?locale=tr.

- 16.Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, Glismann S, Rosenthal SL, Larson HJ.. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34:6700–06. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karafillakis E, Dinca I, Apfel F, Cecconi S, Wűrz A, Takacs J, Suk J, Celentano LP, Kramarz P, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in Europe: a qualitative study. Vaccine. 2016;34(41):5013–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.[accessed 2020 Jul 20]. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/15-07-2020-who-and-unicef-warn-of-a-decline-in-vaccinations-during-covid-19.

- 19.Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health COVID-19 Information. [accessed 2020 Oct 10]. https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/TR-66935/genel-koronavirus-tablosu.html.

- 20.McDonald HI, Tessier E, White JM, Woodruff M, Knowles C, Bates C, Parry J, Walker JL, Scott JA, Smeeth L. Early impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and physical distancing measures on routine childhood vaccinations in England, January to April 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020May14;25(19):2000848. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.19.2000848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weller C. While we wait for a COVID-19 vaccine, let’s not forget the importance of the vaccines we already have. [accessed 2020 Jun 28]. https://wellcome.ac.uk/news/while-we-wait-covid-19-vaccine-lets-not-forget-importance-vaccines-we-already-have.

- 22.Benefit-risk analysis of health benefits of routine childhood immunisation against the excess risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections during Covid-19 pandemic in Africa. [accessed 2020 Jun 26]. http://immunizationeconomics.org/recent-activity/2020/4/29/benefit-of-routine-immunization-outweighs-covid-19-risks. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Vaccinations and COVID-19: what parents need to know. [accessed 2020 Jun 25]. https://www.unicef.org/turkey/en/stories/vaccinations-and-covid-19-what-parents-need-know.