ABSTRACT

Clinical development of Ebola virus vaccines (EVV) was accelerated by the West African Ebola virus epidemic which remains the deadliest in history. To compare and rank the EVV according to their immunogenicity and safety. A total of 21 randomized controlled trial, evaluating seven different vaccines with different doses, and 5,275 participants were analyzed. The rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (2 × 10 7) vaccine was more immunogenic (P-score 0.80). For pain, rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (≤10 5) had few events (P-score 0.90). For fatigue and headache, the DNA-EBOV (≤ 4 mg) was the best one with P-scores of 0.94 and 0.87, respectively. For myalgia, the ChAd3 (10 10) had a lower risk (P-score 0.94). For fever, the Ad5.ZEBOV (≤ 8 × 10 10) was the best one (P-score 0.80). The best vaccine to be used to stop future outbreak of Ebola is the rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine at dose of 2 × 107 PFU.

KEYWORDS: Ebolavirus, network meta-analysis, vaccine, healthy volunteer

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the 2013–16 West African Ebola Virus epidemic (EBOV) was the largest and deadliest in history with more than 28,600 confirmed infections and over 11,300 deaths.1,2

Since this epidemic, many efforts have been made to accelerate the development of candidate vaccines against Ebola virus disease (EVD). To date, only the recombinant replication competent vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine expressing the glycoprotein of a Zaire Ebolavirus licensed as ERVEBO® (rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP) at a dose of 2 × 107 plaque-forming unit (PFU) has been proven to have a high efficacy and effectiveness to prevent EVD in contacts and contacts of contacts of recently confirmed cases in Guinea (Conakry) and Sierra-Leonne.3 However, some safety concerns related to this vaccine, in particular one anaphylaxis,3 four arthralgia,4 and 19 arthritis4 have been reported. The need for an alternative vaccine is all the more crucial since vaccination not only prevents infection but also limits its severity: in a recent therapeutic study including affected patients during the 2018 EVD outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (RDC), those who had been vaccinated had less severe clinical forms at baseline.5

Many other vaccines have been tested in healthy volunteers, with promising results on both safety and immunogenicity, but with very different protocols (design, dose administered or timing of evaluation).6,7 With the multiplicity of clinical trials against EVD, data on an effective vaccine with the optimal dose are needed to control any future outbreak like the one that happened in West Africa or more recently in the Democratic Republic of Congo.5

To our knowledge, no systematic review or meta-analysis has been conducted to summarize published data on candidate vaccines from clinical trials studies in healthy adults to identify the most effective in terms of safety and immunogenicity. We therefore conducted a network meta-analysis (NMA) to compare and rank candidate vaccines tested in healthy adults in terms of safety and immunogenicity to prevent EVD.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched through MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane library (CENTRAL) for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated Ebola virus vaccine safety and immunogenicity in healthy adults. Despite the extensively safety and immunogenicity databases mainly for rVSV and Ad26 or MVA vaccines, we choose to restrict our search to the RCTs which gives the highest evidence level. The search was restricted to any phase trials (1, 2, and 3) conducted in human, and published in English before November 30, 2020. For studies that involve prime/boost, only data from the prime vaccination evaluated 28 days was considered. Studies in which participant were nonrandomly allocated to receive Ebola virus vaccine, or in which a combination of vaccines was used, or in which participants were aged less than 18 years, or in which information on outcomes was lacking were excluded. Using the search terms listed in the Methods in the Supplement, two authors (ADi and VW) identified all relevant studies, then independently reviewed their full texts, and in case of disagreement, differences were resolved through the arbitration by another author (MCB). Extracted data included: first author name and year of publication, country, RCTs design, study follow-up, age (range), proportion of men participants, vaccine type and dosing information, sample size, proportion or number of participants with seroconversion or seroresponse and adverse events, and study sponsorship (Government and/or Industry). The study protocol was registered in the International Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), number CRD42018109473.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was immunogenicity assessed by either the seroconversion rate-proportion of participants who showed at least a four-fold increase in antibody titer for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) 28 days after vaccination-, or seroresponse rate – proportion of participants who had a protective titer (seropositivity) measured by ELISA titer above a prespecified threshold 28 days after vaccination. Because of the variability of the method used to assess immunogenicity of Ebola virus vaccine, we considered only seroconversion or seroresponse rates based on ELISA titers at 28 days. In case both seroconversion and seroresponse were available in a study, only the seroconversion rate was used, as it is less sensitive to baseline status. Secondary outcomes were the most common Adverse Events (AEs) occurring within the first 14 days post vaccination, and recorded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.8 The two categories of Adverse Events outcomes considered in this network meta-analysis were the solicited local reaction, mainly injection-site pain, and the systematic reactions including fatigue, headache, fever, and myalgia. Because of the limited number of recorded Grade 3 adverse events, we subtracted them from the analysis, leaving only the reported mild (Grade 1) and moderate (Grade 2), which were analyzed together as a single outcome.

Data analysis

The original clinical trials were described using table of study characteristics and forest plot. The Cochrane risk of bias tools9 and Revman version 5.3 were used to assess the risk of bias and to generate the corresponding figures. We opted for a frequentist approach to compare safety and immunogenicity between candidates vaccine using a random-effects network meta-analysis (NMA) for binary endpoint. Summary estimates were reported as odds ratio (OR) with their reported 95% confidence intervals. For immunogenicity, beneficial vaccine effects are described by ORs > 1, while for the safety outcomes, beneficial vaccine effects are described by ORs < 1. Because of the large variety of tested dose by vaccine, we grouped them in 12 categories (≤ 4 mg, 8 mg, ≤ 105, 106, 107, 2 × 107, 5 × 107, 108, 1010, ≤8 × 1010, 1011, and 1.6 × 1011), then we considered these categories as separate nodes in the network. For each dose group, we distinguished between placebo, Ad26.ZEBOV, Ad5-EBOV, Chad3-ZEBOV, DNA-EBO, MVA-BN-Filo, rVSVN4CT1-EBOVGP1, and rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP, thereby giving 18 different groups of vaccine to compare. Full names of these acronyms are defined in appendix (page 6). To display the relative efficacy on immunogenicity and adverse events outcomes of all available pairwise comparisons between vaccine, league tables were used. A P-score ranging from 0 (worst vaccine) to 1 (best vaccine) was computed for each vaccine, then the vaccine with the highest P-score was selected as the preferred vaccine regimen for each considered outcome. Heterogeneity and inconsistency were quantified using the global Q test proposed by Rucker.10 The Q statistic is the sum of statistic for heterogeneity, which represent the proportion of the total variation in study estimates (within-designs), and a statistic for inconsistency (between-designs), which represents the variability of the vaccines effect between direct and indirect comparisons at the meta-analytic level.10 To visualize and identify nodes of single-design inconsistency, we used a network heat plot. Consistency between direct and indirect comparisons was checked using the so-called node-splitting. We conducted three sensitivity analyses, first to assess sponsorship bias by excluding studies sponsored by industrial companies, second to test for differences between health care system by excluding studies conducted in Africa, and finally to assess the impact of the risk of bias by excluding studies with a moderate risk of bias. No subgroup analysis was performed. All analyses were performed using R package ‘netmeta’;10 P-values <.05 were considered significant for the difference between vaccines.

Results

Included studies

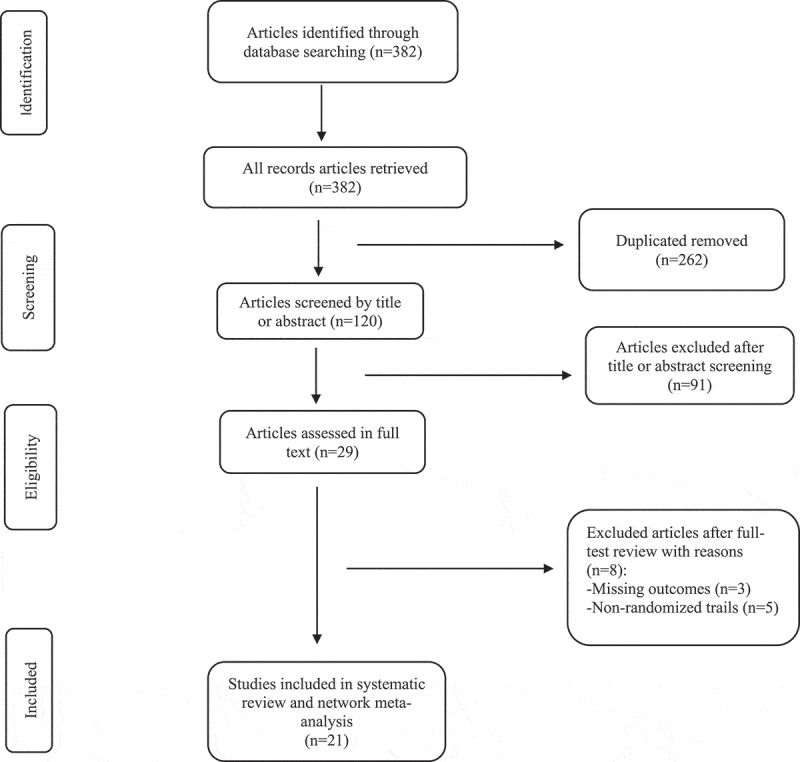

The initial search through all database identified 382 citations, of which 120 were screened by title and abstract after removing duplicates. Of the 29 full-text citations reviewed, 21 RCTs4,11–31 that met the inclusion criteria were finally included in the quantitative network meta-analysis (Figure 1). These RCTs were published from 2006 to 2020, 13 in high impact factor journals (9 in The Lancet, 3 in The NEJM, 1 in JAMA). Fifteen were phase 1 trial, 2 were phase 3 trials, 17 were blinded, 15 were conducted in high-income countries, and 18 were sponsored by Government institutions. For the phase 3 study conducted in Sierra-Leonne, we included only the participants involved in the safety sub-study (n = 449). Together, these 21 RCTs included 5,275 healthy volunteers aged 18 and 65 years, of whom 2,983 (56.5%) were male. A total of 62 comparisons for immunogenicity (Figure 2) were investigated in a follow-up time ranging from 12 weeks to 12 months (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of studies selected for meta-analysis of RCT Ebola vaccine

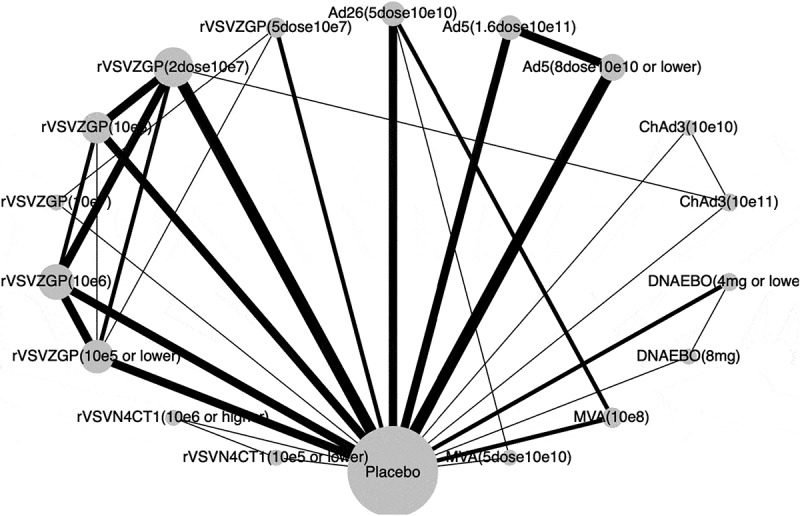

Figure 2.

Network graph of eligible Ebola vaccines comparisons for immunogenicity

Line width is proportional to the number of trials comparing every pair of vaccine. The size of the circle is proportional to the number of participants assigned to receive the vaccine. rVSVZGP (10e5 or lower), (10e6), (10e7), (2dose10e7), (5dose10e7), and (10e8) were the recombinant replication competent vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine expressing the glycoprotein of a Zaire Ebolavirus (rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP) at doses of ≤ 105 plaque-forming unit (PFU), 106 PFU, 107 PFU, 2 × 107 PFU, 5 × 107 PFU, and 108 PFU; ChAd3 (10e10) and (10e11) were the replication-defective chimpanzee adenovirus 3 vector expressing Zaire-Ebola virus glycoprotein (ChAd3-EBO-Z) at doses of 1010 viral particles (VP) and 1011 VP; MVA (10e8) was the modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) expressing Zaire Ebola virus glycoprotein and other filovirus antigens (MVA-BN-Filo) at doses of 1 × 108 50% tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50); Ad5 (8dose10e10 or lower) and (1.6dose10e11) were the adenovirus type-5 vector-based Ebola vaccine (Ad5-ZEBOV) at doses of ≤ 5 × 1010 VP and 1.6 × 1011 VP; Ad26 (5dose10e10) was the adenovirus type-26 vector-based Ebola vaccine (Ad26-ZEBOV) at doses of 5 × 1010 VP; and DNAEBO (4 mg or lower) and 8 mg were the Ebola virus glycoprotein DNA vaccine (EBODNA012-00-VP) at doses of ≤ 4 mg/ml and 8 mg/ml; rVSVN4CT1 (10e5 or lower), and (10e6) were the recombinant replication competent vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine expressing HIV-1 gag and glycoprotein of Ebolavirus (rVSVN4CT1-EBOVGP1) at doses of 2.5 × 104 PFU, 2.5 × 105 PFU, and 2 × 106 PFU.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included trials investigating the immunogenicity and safety of Ebola virus vaccination

| Study | Country | Design | Age (years) | Follow-up | Proportion of men participants | Vaccine type | Dosing Information | Main outcomes at 14 days for Safety and 28 days for Immunogenicity measured by ELISA | Sponsorship | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martin et al.10 | USA | RCT, phase 1, double-blind | 18–44 | 12 months | 67% | DNA | EBODNA012-00-VP (2 mg), EBODNA012-00-VP (4 mg), EBODNA012-00-VP (8 mg), placebo | ELISA positive response rate to GP [Z], pain, myalgia, headache, fever, myalgia, malaise, nausea, induration, skin discoloration | NR | |

| Ledgerwood et al.11 | USA | RCT, phase 1, double-blind | 18–50 | 48 weeks | 53% | rAd5.ZEBOV-GP | rAd5.ZEBOV.GP (2 × 109 VP), rAd5.SBOV.GP (2 × 1010 VP), placebo | ELISA positive response rate to GP [Z], pain, myalgia, headache, fever, myalgia, malaise, chills, nausea, redness, swelling | NR | |

| Zhu et al. 12 | China | RCT, phase 1, double-blind | 18–60 | 4 weeks | 49% | rAd5.ZEBOV-GP | rAd5.ZEBOV.GP high dose (1.6 × 1011 PV), rAd5.ZEBOV.GP low dose (4 × 1010 PV), placebo | ELISA EC90 positive response, pain, myalgia, headache, fever, myalgia, fatigue, vomiting, cough, diarrhea, induration, redness, swelling, joint pain | Government and Industry | |

| Huttner et al.13 | Switzerland (Geneva) | RCT, phase 1–2, double-blind | 18–65 | 12 weeks | 54% | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (3 × 105 PFU), rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (1 × 107 PFU), rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (5 × 107 PFU), placebo | ELISA seropositivity rate, local pain, fever, fatigue, headache, myalgia, chills, | Wellcome Trust through WHO | |

| Kibuuka et al.14 | Uganda (Kampala) |

RCT, phase 1b, double-blind | 18–50 | 24 months | 82% | DNA | EBO vaccine (4 mg), placebo | Proportion of positive response by ELISA titer of 30 or higher, pain, tenderness, swelling, redness, chills, aching joints, fatigue, headache, fever, nausea, muscle aches | Government | |

| Agnandji et al.a 15 | Switzerland (Geneva) | RCT, phase 1, double-blind | 18–65 | 6 months | 61% | rVSV-ZEBOV-GP | rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (1 × 107 PFU), rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (5 × 107 PFU), placebo | Seropositivity rate measured by ELISA of 50 or more, erythema, swelling/induration, pain, fever, chills, myalgia, headache, fatigue, gastro-intestinal symptoms, oral vesicle, arthralgia, arthritis | Government | |

| D Tapia et al.b,d 16 | USA, Mali (groups 3B and 3 C) | RCT, phase 1, double-blind | 18–65 | 5 months | 45% (USA), 80% (Mali) | ChAd3-EBO-Z | ChAd3-EBO-Z (1 × 1010 VP), ChAd3-EBO-Z (1 × 1011 VP), ChAd3-EBO-Z (2.5 × 1010 VP), ChAd3-EBO-Z (5 × 1010 VP), | Proportion of positive ELISA GP [Z] response or responses of more than reference value, pain and tenderness, fever, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, chills, nausea | Government | |

| De Santis et al.17 | Switzerland (Lauzanne) |

RCT, phase 1–2a, double-blind | 18–65 | 6 months | 49% | ChAd3-EBO-Z | ChAd3-EBO-Z (2.5 × 1010 VP), ChAd3-EBO-Z (5 × 1010 VP), placebo | Proportion of positive ELISA GP [Z] response, pain, swelling, erythema, axillary lymphatic-node, chills, fatigue or malaise, headache, fever, nausea, musculo- articular pain, abdominal pain, conjunctivitis, rhinitis, sweating | Government | |

| Milligan et al.c, d 18 | UK | RCT, phase 1, observer-blind | 18–50 | 8 months | 36% | Ad26.ZEBOV, MVA-BN-Filo | Ad26.ZEBOV (5 × 1010 VP), MVA-BN-Filo (1 × 108 TCID50), placebo | Percentages of vaccine responders assessed by ELISA, pain, erythema, warmth, pruritus, swelling, induration, fatigue, headache, fever, nausea, myalgia, chills, rash, nausea, pyrexia, arthralgia, vomiting | Government and Industry | |

| Heppner et al.19 | USA | RCT, phase 1, double-blind | 18–61 | 12 months | 53% | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (3 × 103 PFU), rVSV-ZEBOV-GP (3 × 104 PFU), rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (3 × 105 PFU), rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (3 × 106 PFU), rVSV-ZEBOV-GP (9 × 106 PFU), rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (2 × 107 PFU), rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (1 × 108 PFU), placebo | Seroconversion for IgG ELISA as four times or more than baseline titer, abdominal pain, diarrhea, fatigue, shivering or chills, headache, joint aches and pain, joint swelling or tenderness, vomiting, myalgia, nausea, fever, sweats arm pain, local tenderness | Government | |

| Agnandji et al.4 | Gabon (Lambaréné) |

RCT, phase 1, open-label | 18–50 | 6 months | 82% | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP | rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (3 × 103 PFU), rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (3 × 104 PFU), rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (3 × 105 PFU), rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (3 × 106 PFU), rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (2 × 107 PFU), placebo | Seropositivity rates as percentage of participants having arbitrary ELISA units (AEU) > a cutoff per vaccine, Seroconversion rates as % of converted in each group, pain, swelling, chills, fatigue, headache, fever, nausea, myalgia, arthralgia, mouth ulcer, skin lesion, blister, malaria, rhinitis, cough, gastro-intestinal symptoms | Government | |

| Zhu et al.20 | Sierra Leone | RCT, phase 2, double-blind | 18–50 | 6 months | 54% | rAd5.ZEBOV-GP | rAd5.ZEBOV-GP (1.6 × 1011 VP), rAd5.ZEBOV-GP (8 × 1010 VP), placebo | Number of responders assessed by neutralizing antibody titer against Ad5 > 1:200, induration, swelling, rash, fever, headache, fatigue, cough, pain, joint pain, muscle pain, throat pain, diarrhea, itch, vomiting | Government and Industry | |

| Kennedy et al.21 | Liberia | RCT, phase 2, double-blind | 18 or more | 12 months | 63% | ChAd3-EBO-Z, rVSV-ZEBOV-GP | ChAd3-EBO-Z (1 × 1011 VP), rVSV-ZEBOV-GP (2 × 107 VP), placebo | Positive antibody response as IgG antibody titer against EBOV-GP of more than 607 EU, headache, muscle pain, feverishness, fatigue, joint pain, rash, nausea, abnormal sweating, mouth ulcer | Government | |

| Elsherif et al.22 | Canada | RCT, phase 1, observer-blind |

18–65 | 6 months | 42% | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (1 × 105 PFU), rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (5 × 105 PFU), rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (3 × 106 PFU), placebo | Seroconversion as at least 4-fold increase from ELISA baseline, pain, abdominal pain, chills, arthralgia, fever, diaphoresis, diarrhea, fatigue, headache, myalgia, nausea | Government | |

| Li et al.d 23 | China | RCT, phase 1, double-blind | 18–60 | 6 months | 48% | rAd5.ZEBOV-GP | rAd5.ZEBOV-GP (1.6 × 1011 VP), rAd5.ZEBOV (4 × 1010 VP), placebo | Number of responders assessed by neutralizing antibody titer against Ad5 > 1:200, induration, swelling, itch, fever, headache, fatigue, cough, pain, joint pain, muscle pain, throat pain, diarrhea, vomiting | Government | |

| Regules et al.24 | USA | RCT, phase 1, observer-blind | 18–50 | 8.5 months | 71% | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (3 × 106 PFU), rVSVΔG -ZEBOV-GP (2 × 107 PFU), rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (1 × 108 PFU), placebo | Positive response for ELISA was a titer of 50 or more, Seroconversion was a quadrupling of the titer over the baseline value, abdominal pain, site pain, headache, myalgia, nausea, fever, fatigue, chills, arthralgia, diaphoresis, diarrhea | Government | |

| Mutua et al.d 25 | Kenya (Nairobi) | RCT, phase 1, observer-blind | 18–50 | 12 months | 68% | Ad26.ZEBOV, MVA-BN-Filo | Ad26.ZEBOV (5 × 1010 VP), MVA-BN-Filo (1 × 108 TCID50) | ELISA positive response rate to GP [Kikwit], injection site pain, injection site pruritus, injection site warmth, headache, fatigue, fever, myalgia, arthralgia, chills, nausea, vomiting, rash, pyrexia, pruritus (generalized) | Government and Industry | |

| Anywaine et al.d 26 | Uganda (Masaka), Tanzania (Mwanza) | RCT, phase 1, observer-blind | 18–50 | 8 months | 79% | Ad26.ZEBOV, MVA-BN-Filo | Ad26.ZEBOV (5 × 1010 VP), MVA-BN-Filo (1 × 108 TCID50) | ELISA positive response rate to GP [Kikwit], injection site pain, injection site pruritus, injection site warmth, headache, fatigue, fever, myalgia, arthralgia, chills, nausea, vomiting, rash, pyrexia, pruritus (generalized) | Government and Industry | |

| Samai et al.27 | Sierra Leone | RCT, phase 2/3 unblinded |

≥18 year older | 6 months | 60.6% | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (single dose 2 × 107 PFU) | Vaccine efficacy ≥ 50% or there was a 2-fold infection risk increase; safety outcome | Government | |

| Halperin et al.28,29 | USA, Spain, Canada | RCT, phase 3, double blind, placebo controlled | 18–65 | 24 months | 45.9% | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP | rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP 2x107 PFU, High dose 1 × 108 PFU |

ELISA positive response rate to GP, PRNT seroresponse rate, injection site adverse events, fever, headache, arthralgia, pain, chills, fatigue | Government and industry | |

| Clark et al.30 | Melbourne, USA | RCT, phase 1, Double blind, placebo controlled |

27–60 | 6 months | 46% | rVSVN4CT1-EBOVGP1 | rVSVN4CT1-EBOVGP1 2 doses (d0, d28) low dose 2.5 × 104 intermediate dose 2.0 × 105 High dose 1.8x108 |

ELISA positive response rate to GP, fever, malaise or fatigue, myalgia, headache, nausea, vomiting, chills, arthralgia, diarrhea | Government | |

RCT: randomized controlled trials; rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP: recombinant replication competent vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine expressing the glycoprotein of a Zaire Ebolavirus; ChAd3-EBO-Z: replication-defective chimpanzee adenovirus 3 vector expressing Zaire-Ebola virus glycoprotein; MVA-BN-Filo: modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) expressing Zaire Ebola virus glycoprotein and other filovirus antigens; Ad5.ZEBOV: adenovirus type-5 vector-based Ebola vaccine; Ad26.ZEBOV: adenovirus type-26 vector-based Ebola vaccine; EBODNA012-00-VP: Ebola virus glycoprotein DNA vaccine; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. a Studies in Lambaréné, Kilifi, and Hamburg were open-label, uncontrolled phase 1 trials; b Group 3A and group 4 from Malian trials were open-label, and Nested randomized Malian trial is a nested booster study, these trials were excluded from the review and network meta-analysis. c Additional nonrandomized open-label group received Ad26.ZEBOV (5 × 107 VP) prime and MVA-BN-Filo (1 × 108 TCID50) boost on 15-day were excluded in this study. d These studies included both prime and boost on days 29 or 56 or later; only data for the first vaccination (prime) were considered in this study. PFU: plaque-forming unit; TCID50: 50% tissue culture infectious doses; VP: viral particles. NR: not reported.

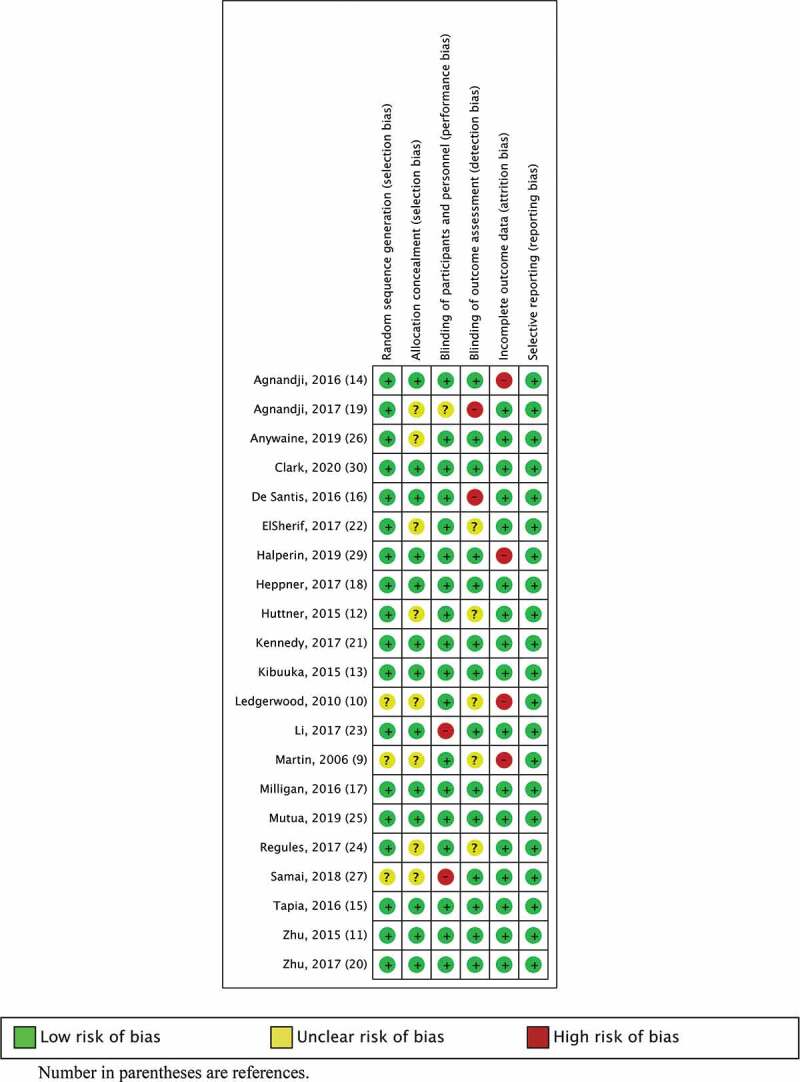

The methodological quality of the included RCTs is shown in Figure 3. Overall, the risk of bias was low in nine RCTs, and moderate in the others (Figure S1 and Table S1 in the Supplement). A higher risk of attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), detection bias (blinding outcome assessment), and performance bias (blinding participants and personnel) occurred in 4, 2, and 2 of 21 RCTs respectively.

Figure 3.

Summary of risk bias assessment for RCTs Ebola vaccines comparisons

Number in parentheses are references.

Immunogenicity

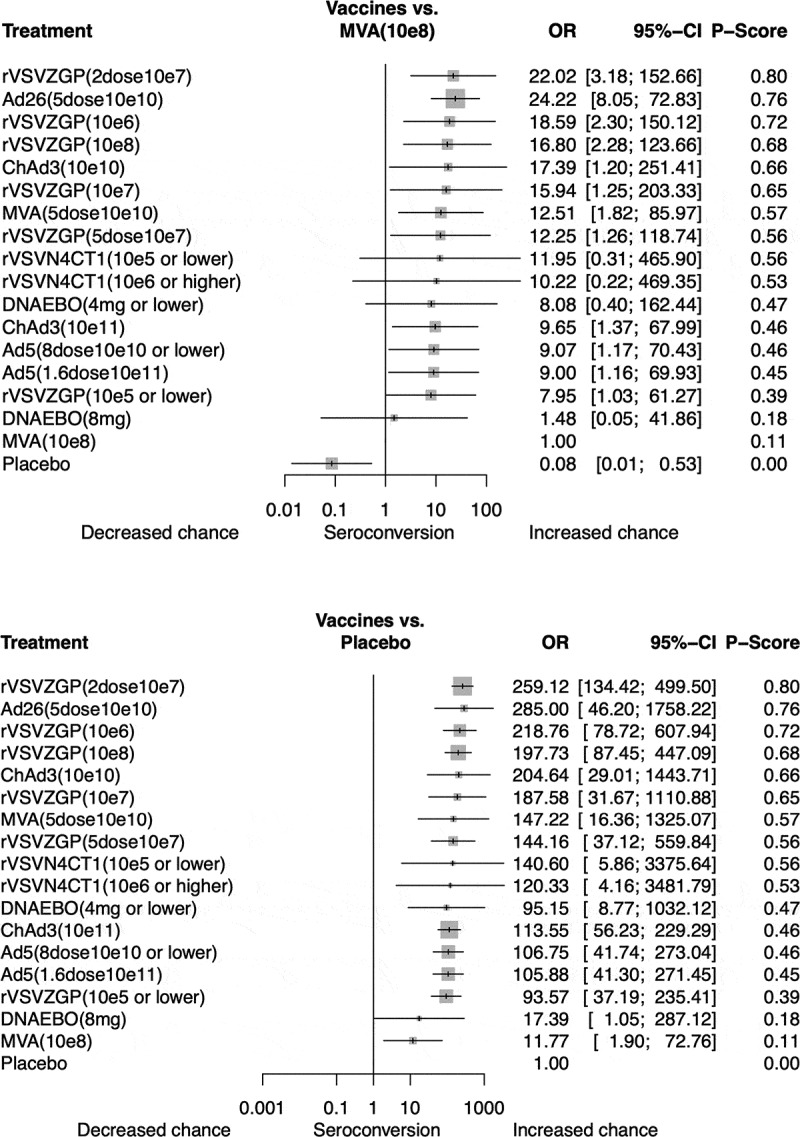

Of the 5,275 participants, 3,110 (59.0%) had seroconverted at 28-days post-vaccination. Figure 2 shows the network for immunogenicity captured by the immunogenicity of candidate vaccine against Ebola virus. All vaccines were significantly more immunogenic than placebo (Figure 4), and the corresponding pairwise comparisons are summarized in the Supplement (Table S2). The vaccine with the highest probability of giving the highest seroconversion rate was the recombinant vesicular virus-based vaccine expressing a Zaire Ebola virus glycoprotein (rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP) at the dose of 2 × 107 PFU, with a P-score of 0.80, and an OR over Placebo of 259.1 (95% CI 134.4–449.5). Among vaccines, we found that the MVA-BN-Filo at dose of 108 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious doses) was significantly less immunogenic. Compared to the latter, patients in the adenovirus type-26 vector-based Ebola group (Ad26-ZEBOV) at doses of 5 × 1010 VP had 24 times more likely to be immunized 28-days after vaccination (Figure S2). Only 2 others pairwise comparisons were significant: the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine with doses of 2 × 107 PFU (OR 2.77, 1.24–6.21) and 106 PFU (2.34, 1.08–5.06) conferred more immunogenicity than lower dose (≤ 5 × 105 PFU). Likewise, no significant differences were found between direct and indirect treatment estimates comparisons or evidence of publication bias according to the comparison-adjusted funnel plot (Figure S3 in the Supplement).

Figure 4.

Pairwise comparisons in network meta-analysis for immunogenicity

Safety

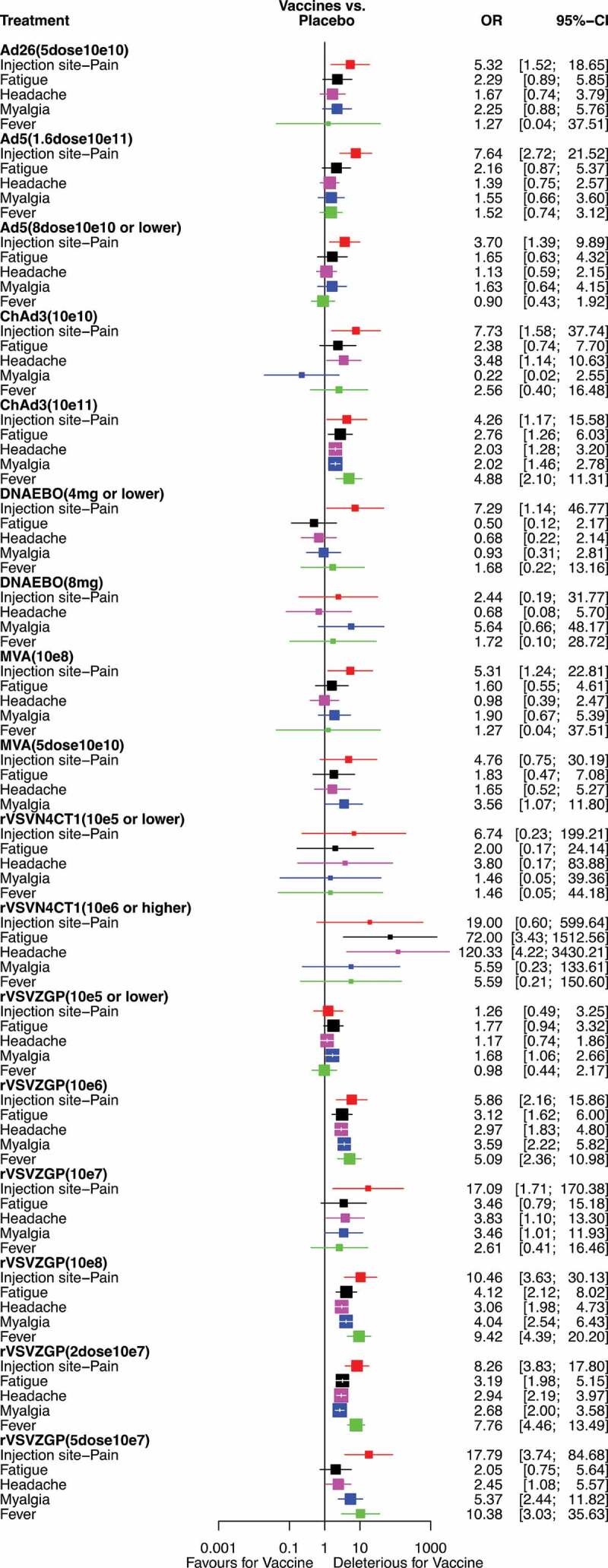

A total of 9,194 adverse events were reported between seven- and 14-days post-vaccination, in which 127 (1.4%) were severe (SAEs). The ratio of adverse events per participant was 1.7 (9,194/5,275) meaning that on average each participant reported at least more than one adverse reaction (local or systemic). The most commonly reported mild-to-moderate AEs were injection-site pain (1,544 AEs), headache (1,578), fatigue (1,007), myalgia (810), and fever (1,145). Likewise, among the 127 severe reported adverse reactions, the most prevalent were headache (33), fever (32), fatigue (20), chills (15), and myalgia (13).

rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (≤105) was associated with a 90% lower probability of injection-site pain (P-score 0.90). Importantly, the lower dose (≤ 105 PFU) of the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine induced a lower risk of pain compared to the same vaccine at higher doses. The corresponding risk reduction of pain were 78% (0.22, 0.08–0.60) for 106 PFU, 85% (0.15, 0.06–0.41) for 2 × 107 PFU, 88% (0.12, 0.04–0.40) for 108 PFU, 93% (0.07, 0.01–0.76) for 107 PFU, and 93% (0.07, 0.02–0.33) for 5 × 107 PFU. In addition, the lower dose (105 PFU) of the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine reduced by 83% (0.17, 0.04–0.67) the risk of injection site pain when compared to the Ad5 (1.6 × 1011) vaccine (Table S3 in the Supplement).

For fatigue, the network meta-analysis was conducted in 19 RCTs involving 17 groups of vaccines and 59 pairwise comparisons. We found that the DNA-EBOV vaccine at dose of ≤ 4 mg was associated with less fatigue symptoms with a higher probability (P-score 0.94) of being the best one. The fatigue risk reduction for DNA-EBOV vaccine (≤ 4 mg) was 82% (0.18, 0.03–0.95) compared to the ChAd3 vaccine at dose of 1011, 84% (0.16, 0.03–0.80) for 106 PFU, 84% (0.16, 0.03–0.73) for 2 × 107 PFU, and 88% (0.12, 0.02–0.61) for 108 PFU. Compared to placebo, the highest dose of ChAd3 vaccine (1011) multiplied by 2.76 (1.26–6.03) the risk of fatigue (Figure 5). The corresponding increased risk of fatigue compared with rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine were 3.12 (1.62–6.00) for 106 PFU, 3.19 (1.98–5.15) for 2 × 107 PFU, and 4.18 (2.12–8.02) for 108 PFU. In addition, a higher dose (106 PFU) of rVSVN4CT1-EBOVGP1 vaccine was significantly associated with an increased risk of fatigue compared with other vaccines, except for the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine at dose of 107 PFU (0.05, 0.00–1.42) and 108 PFU (0.06, 0.00–1.29) (Table S4 in the Supplement). Finally, a lower dose (≤ 105) of rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine was associated with 57% (0.43, 0.20–0.91) risk reduction of fatigue compared with a higher dose (108 PFU).

Figure 5.

Pairwise comparisons in network meta-analysis for safety outcomes (injection site-pain, fatigue, headache, myalgia, and fever)

OR: odds ratio; CI: 95% confidence interval; rVSVZGP (10e5 or lower), (10e6), (10e7), (2dose10e7), (5dose10e7), and (10e8) were the recombinant replication competent vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine expressing the glycoprotein of a Zaire Ebolavirus (rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP) at doses of ≤ 105 plaque-forming unit (PFU), 106 PFU, 107 PFU, 2 × 107 PFU, 5 × 107 PFU, and 108 PFU; ChAd3 (10e10) and (10e11) were the replication-defective chimpanzee adenovirus 3 vector expressing Zaire-Ebola virus glycoprotein (ChAd3-EBO-Z) at doses of 1010 viral particles (VP) and 1011 VP; MVA (10e8) was the modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) expressing Zaire Ebola virus glycoprotein and other filovirus antigens (MVA-BN-Filo) at doses of 1 × 108 50% tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50); Ad5 (8dose10e10 or lower) and (1.6dose10e11) were the adenovirus type-5 vector-based Ebola vaccine (Ad5-ZEBOV) at doses of ≤ 5 × 1010 VP and 1.6 × 1011 VP; Ad26 (5dose10e10) was the adenovirus type-26 vector-based Ebola vaccine (Ad26-ZEBOV) at doses of 5 × 1010 VP; and DNAEBO (4 mg or lower) and 8 mg were the Ebola virus glycoprotein DNA vaccine (EBODNA012-00-VP) at doses of ≤ 4 mg/ml and 8 mg/ml; rVSVN4CT1 (10e5 or lower), and (10e6) were the recombinant replication competent vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine expressing HIV-1 gag and glycoprotein of Ebolavirus (rVSVN4CT1-EBOVGP1) at doses of 2.5 × 104 PFU, 2.5 × 105 PFU, and 2 × 106 PFU.

For headache, pairwise comparisons were performed in all RCTs. As for fatigue, the DNA-EBOV vaccine at dose of ≤ 4 mg gave the best results (P-score 0.87). A significantly lower risk of headache was seen in 39 of the 63 indirect comparisons (Table S5 in the Supplement). The specific risk reductions of headache for DNA-EBOV vaccine (≤ 4 mg) were 80% (0.20, 0.04–0.97) and 99% (0.01, 0.00–0.20) compared to the ChAd3 vaccine at dose of 1011 and to the rVSVN4CT1-EBOVGP1 at dose of 106 PFU, respectively. The corresponding risk reductions of headache compared to the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine were 77% (0.23, 0.07–0.79) for 106 PFU, 77% (0.23, 0.07–0.75) for 2 × 107 PFU, 78% (0.22, 0.07–0.76) for 108 PFU, and 82% (0.18, 0.03–0.97) for 107 PFU. In addition, when compared with rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP at dose of 2 × 107 PFU, the risk of headache was reduced by 67% (0.33, 0.12–0.94) for MVA-BN-Filo (108 TCID50), 62% (0.38, 0.19–0.78) for Ad5-EBOV (≤ 8 × 1010), 60% (0.40, 0.25–0.64) for rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (≤ 105), and 60% (0.40, 0.25–0.64) for Ad5-EBOV (1.6 × 1011). The corresponding risk reduction of headache compared with rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP at dose of 106 and 108 PFU were shown in supplemental Table S5. As for fatigue, a higher dose (106 PFU) of rVSVN4CT1-EBOVGP1 vaccine was significantly associated with an increased risk of headache, except for the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine at dose of 107 PFU (0.03, 0.00–1.13).

The risk of myalgia was assessed in 19 RCTs involving 18 different groups of vaccines and 61 pairwise comparisons. ChAd3 at dose of 1010 VP was associated with a lower risk of myalgia (P-score 0.94). A total of 26 indirect comparisons were significant, with a 40% to 96% risk reduction of myalgia (Table S6 in the Supplement). These specific risk reductions were more important for ChAd3 vaccine (1010 VP) compared with rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP: 92% (0.08, 0.01–0.95) for 2 × 107 PFU, 94% (0.06, 0.00–0.98) for 107 PFU, 94% (0.06, 0.01–0.73) for 106 PFU, 94% (0.06, 0.00–0.65) for 108 PFU, and 96% (0.04, 0.00–0.53) for 5 × 107 PFU (Figure 5).

For fever, data were available in 19 RCTs with 17 different groups vaccines yielding 57 pairwise comparisons. Ad5-EBOV at dose of ≤ 8 × 1010 was ranked as giving the best results (P-score 0.80). This vaccine was associated with a lower risk of fever (0.19, 0.06–0.57) compared with ChAd3 vaccine (1011). The corresponding specific risk reduction of fever for Ad5-EBOV vaccine (8 × 1010) compared with rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP were 82% (0.18, 0.06–0.52) for 106 PFU, 88% (0.12, 0.05–0.30) for 2 × 107 PFU, 90% (0.10, 0.03–0.28) for 108 PFU, and 91% (0.09, 0.02–0.37) for 5 × 107 PFU. In addition, ChAd3 (1011) and rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccines (106, 2 × 107, 5 × 107, and 108) were associated with more fever than placebo, a lower dose of rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine (≤ 105), and Ad5-EBOV vaccine (≤ 8 × 1010 and 1.6 × 1011) (Table S7 in the Supplement). The remaining significant comparisons for headache, myalgia, and fever were showed in the Supplement (Table S5 to Table S7).

Heterogeneity, consistency, and sensitivity

Except for injection-site pain, fatigue, and fever, no general heterogeneity or inconsistency of vaccine effect was found (P value greater than 0.05; I2 ranging from 0% to 18%). These finding were supported by the heat plot displayed in the Supplemental Figures S4 to S9. In sensitivity analysis, after excluding the nine studies12–14,19,21,24,27–30 sponsored by the Industrial companies or the seven ones conducted in Africa,15,17,20,21,26–28 the Ad5.ZEBOV (1.6 × 1011) became the most immunogenic vaccine (P-score 0.91 and 0.88, respectively). Finally, after considering only the nine studies with a lower risk of bias,4,13,15,17,19,21,22,26,31 the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (108) became the most immunogenic vaccine (P-score 0.76).

Discussion

This study, based on 21 RCTs involving 5,275 healthy volunteers randomly assigned to 18 different groups of candidate vaccines, is the first network meta-analysis of vaccines against Ebola virus. Considering immunogenicity, we found that the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine at the dose of 2 × 107 PFU was the most effective available option. These findings support the high protective role of this treatment option to prevent Ebola virus disease, as previously reported from individual phase 1 and/or 2 studies, and data from phase 3 conducted in contacts and contacts of contacts in Guinea (Conakry) and Sierra-Leonne.3 We found a good overall consistency of the network meta-analysis for immunogenicity.

Despite a rapid immune response, the safety profile of the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine (2 × 107) would be questionable for mass vaccination in the absence of immediate risk of exposure. Compared with others vaccines, we found increased injection site-pain and fever reported by patients who received a single dose of this vaccine. These findings are in lines with those reported in Ebola ça Suffit trial where 80 serious adverse events were identified, of which two were judged to be related to vaccination (one febrile reaction and one anaphylaxis). A high reactogenicity may increases vaccine hesitancy, especially in Africa where unfavorable socioeconomic factors, low level of health education, lack of disease awareness, religious and cultural beliefs may decrease vaccination uptake. Future studies should be conducted in African populations that have experienced Ebola disease to investigate risk factors and barriers to vaccination.

In the sensitivity analysis, we found a substantial change in vaccines effect estimates from those seen in the overall network meta-analysis for immunogenicity. When excluding studies sponsored by the industry companies12–14,19,21,24,27–30 or those conducted elsewhere other than Africa area,15,17,20,21,26–28 the Ad5.ZEBOV (1.6 × 1011 VP) became the most immunogenic vaccine, suggesting that Ad26.ZEBOV might be a possible alternative vaccine. Compared to placebo, the Ad26.ZEBOV vaccine gives the highest immunogenic level, and was associated with a lower rate of reactogenicity. Moreover, no difference in terms of risk difference (0.04 [95% CI; −0.13 to 0.20]) were observed as compared to the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (2 × 107) vaccine. Pending the results of a large randomized trial between these two vaccines, we recommend to use the Ad26.ZEBOV (5 × 1010 VP) vaccine with an MVA boost in cases of contraindication or limited availability of the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (2 × 107) vaccine to stop future outbreak of Ebola. However, in both indirect comparisons, the precision (95% CI) of vaccine effect estimates for Ad26.ZEBOV (1.6 × 1011) compared with rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (2 × 107) is high, reflecting the relatively small number of participants contributing to the network meta-analysis. The rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine (2 × 107) ranked 4th out of 15 groups of vaccines and 5th out of 17 groups of vaccines, respectively (sensitives analyses). In addition, after taking into account only studies with a low risk of bias, the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (108) become the most immunogenic vaccine, while the same vaccine at dose of 2 × 107 was ranked 3th out of 14 groups of treatments. Nevertheless, these sensitivity analyses were performed on a small number of RCTs with few participants which may have reduced the power of the test.

Some limitations were present in this study. First, the classification used to define these 18 groups of vaccines for comparisons is disputable, and possibly other categorization would result in different conclusions. In addition, the conclusions of the overall network analysis differ substantially from those of the sensitivity analyses, mainly after exclusion of studies sponsored by industrial companies or those conducted outside Africa, suggesting caution in interpretating the data. Second, the different ELISA assays methods and the different thresholds used to define seroconversion rates for immunogenicity may influence the results of the efficacy analysis. Standardized methods would be preferable in order to improve the conclusion in future studies.32 An alternative approach to the use of a single time point of ELISA data would be to focus on peak titers regardless of time point, although neglecting the value of the onset of protection is a problem with this method. Third, the use as a single time-point of the outcome analysis, 28-day after single immunization which limits the ability to assess immunogenicity of Ebola vaccines of more than one dose regimen. Moreover, the methods of comparing vaccines with different immunization regimens in a network meta-analysis remains an open question due to transitivity requirement. Finally, as the search was restricted to English language trials, a residual publication bias is possible despite our effort to locate unpublished trials through ClinicalTrial.gov. Nevertheless, Jüni Peter et al. suggest that bias induces by excluding non-language English trials has only modest effects on aggregated treatment effect estimates.33

Our findings suggest that the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine with dose of 2 × 107 has the strongest evidence for being the most effective vaccine in terms of immunogenicity to prevent the next outbreak of Ebola virus disease. These findings have implications on the design of future clinical trials, and management of the next outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease. Future large prospective RCTs are needed to draw final conclusions.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

| RCT | randomized controlled trials |

| rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP | recombinant replication competent vesicular stomatitis virus-based vaccine expressing the glycoprotein of a Zaire Ebolavirus |

| ChAd3-EBO-Z | replication-defective chimpanzee adenovirus 3 vector expressing Zaire-Ebola virus glycoprotein |

| MVA-BN-Filo | modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) expressing Zaire Ebola virus glycoprotein and other filovirus antigens |

| Ad5.ZEBOV | adenovirus type-5 vector-based Ebola vaccine |

| Ad26.ZEBOV | adenovirus type-26 vector-based Ebola vaccine |

| EBODNA012-00-VP | Ebola virus glycoprotein DNA vaccine |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| PFU | plaque-forming unit |

| TCID50 | 50% tissue culture infectious doses |

| VP | viral particles |

| NR | not reported. |

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

We declare no competing interests in relation to this work.

Author contributions

ADi conceived the study design, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript, MCB supervision of data collection, and critical revision of the manuscript, VW collected data, MHD analyzed the data, BDD, AD, MCG, and FG interpreted and substantially revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data are available upon request (alhassane.diallo@inserm.fr).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1932214.

References

- 1. WHO: Ebola virus disease [situation report] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016 http://apps.who.int/ebola/ebola-situation-reports .

- 2.Urbanowicz RA, McClure CP, Sakuntabhai A, Sall AA, Kobinger G, Müller MA, Holmes EC, Rey FA, Simon-Loriere E, Ball JK, et al. Human adaptation of Ebola virus during the West African outbreak. Cell. 2016;167:1079–1087.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henao-Restrepo AM, Camacho A, Longini IM, Watson CH, Edmunds WJ, Egger M, Carroll MW, Dean NE, Diatta I, Doumbia M, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine in preventing Ebola virus disease: final results from the Guinea ring vaccination, open-label, cluster-randomised trial (Ebola Ça Suffit!). Lancet. 2017;389(10068):505–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32621-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heppner D, Kemp T, Martin B, Ramsey W, Nichols R, Dasen E, Link CJ, Das R, Xu ZJ, Sheldon EA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the rVSV∆G-ZEBOV-GP Ebola virus vaccine candidate in healthy adults: a phase 1b randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:854‐866. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulangu S, Dodd LE, Davey RT, Tshiani Mbaya O, Proschan M, Mukadi D, Lusakibanza Manzo M, Nzolo D, Tshomba Oloma A, Ibanda A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of Ebola virus disease therapeutics. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2293–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martins KA, Jahrling PB, Bavari S, Kuhn JH.. Ebola virus disease candidate vaccines under evaluation in clinical trials. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15:1101–12. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2016.1187566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Li J, Hu Y, Liang Q, Wei M, Zhu F.. Ebola vaccines in clinical trial: the promising candidates. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2017;13:153–68. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1225637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute . Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. 2017Nov27.

- 9.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC, et al. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928–d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Rücker G. Meta-analysis with R. Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin J, Sullivan N, Enama M, Gordon I, Roederer M, Koup R, Bailer RT, Chakrabarti BK, Bailey MA, Gomez PL, et al. A DNA vaccine for Ebola virus is safe and immunogenic in a phase I clinical trial. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:1267‐1277. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00162-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ledgerwood J, Costner P, Desai N, Holman L, Enama M, Yamshchikov G, Mulangu S, Hu Z, Andrews CA, Sheets RA, et al. A replication defective recombinant Ad5 vaccine expressing Ebola virus GP is safe and immunogenic in healthy adults. Vaccine. 2010;29:304‐313. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu F-C, Hou L-H, Li J-X, Wu S-P, Liu P, Zhang G-R, Hu Y-M, Meng F-Y, Xu -J-J, Tang R, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a novel recombinant adenovirus type-5 vector-based Ebola vaccine in healthy adults in China: preliminary report of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2272–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huttner A, Dayer J, Yerly S, Combescure C, Auderset F, Desmeules J, Eickmann M, Finckh A, Goncalves AR, Hooper JW, et al. The effect of dose on the safety and immunogenicity of the VSV Ebola candidate vaccine: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:1156‐1166. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kibuuka H, Berkowitz N, Millard M, Enama M, Tindikahwa A, Sekiziyivu A, Costner P, Sitar S, Glover D, Hu Z, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of Ebola virus and Marburg virus glycoprotein DNA vaccines assessed separately and concomitantly in healthy Ugandan adults: a phase 1b, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015;385:1545‐1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agnandji S, Huttner A, Zinser M, Njuguna P, Dahlke C, Fernandes J, Yerly S, Dayer J-A, Kraehling V, Kasonta R, et al. Phase 1 trials of rVSV Ebola vaccine in Africa and Europe. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1647‐1660. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tapia M, Sow S, Lyke K, Haidara F, Diallo F, Doumbia M, Traore A, Coulibaly F, Kodio M, Onwuchekwa U, et al. Use of ChAd3-EBO-Z Ebola virus vaccine in Malian and US adults, and boosting of Malian adults with MVA-BN-Filo: a phase 1, single-blind, randomised trial, a phase 1b, open-label and double-blind, dose-escalation trial, and a nested, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:31‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Santis O, Audran R, Pothin E, Warpelin-Decrausaz L, Vallotton L, Wuerzner G, Cochet C, Estoppey D, Steiner-Monard V, Lonchampt S, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a chimpanzee adenovirus-vectored Ebola vaccine in healthy adults: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding, phase 1/2a study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:311‐320. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milligan I, Gibani M, Sewell R, Clutterbuck E, Campbell D, Plested E, Nuthall E, Voysey M, Silva-Reyes L, McElrath MJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of novel adenovirus type 26- and modified vaccinia ankara-vectored Ebola vaccines: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1610‐1623. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agnandji S, Fernandes J, Bache E, Obiang Mba R, Brosnahan J, Kabwende L, Pitzinger P, Staarink P, Massinga-Loembe M, Krähling V, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of rVSVDELTAG-ZEBOV-GP Ebola vaccine in adults and children in Lambarene, Gabon: a phase I randomised trial. Plos Med. 2017;14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu F, Wurie A, Hou L, Liang Q, Li Y, Russell J, Wu SP, Li JX, Hu YM, Guo Q, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus type-5 vector-based Ebola vaccine in healthy adults in Sierra Leone: a single-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2017;389:621‐628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy S, Bolay F, Kieh M, Grandits G, Badio M, Ballou R, Eckes R, Feinberg M, Follmann D, Grund B, et al. Phase 2 placebo-controlled trial of two vaccines to prevent Ebola in Liberia. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1438‐1447. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ElSherif M, Brown C, MacKinnon-Cameron D, Li L, Racine T, Alimonti J, Rudge TL, Sabourin C, Silvera P, Hooper JW, et al. Assessing the safety and immunogenicity of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus Ebola vaccine in healthy adults: a randomized clinical trial. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J. 2017;189:E819‐E827. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, Hou L, Meng F, Wu S, Hu Y, Liang Q, Chu K, Zhang Z, Xu -J-J, Tang R, et al. Immunity duration of a recombinant adenovirus type-5 vector-based Ebola vaccine and a homologous prime-boost immunisation in healthy adults in China: final report of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e324‐e334. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regules J, Beigel J, Paolino K, Voell J, Castellano A, Hu Z, Muñoz P, Moon JE, Ruck RC, Bennett JW, et al. A recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus Ebola vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:330‐341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mutua G, Anzala O, Luhn K, Robinson C, Bockstal V, Anumendem D, Douoguih M. Safety and Immunogenicity of a 2-dose heterologous vaccine regimen with Ad26.ZEBOV and MVA-BN-filo Ebola vaccines: 12-month data from a phase 1 randomized clinical trial in Nairobi, Kenya. J Infect Dis. 2019;220:57‐67. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anywaine Z, Whitworth H, Kaleebu P, Praygod G, Shukarev G, Manno D, Kapiga S, Grosskurth H, Kalluvya S, Bockstal V, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a 2-dose heterologous vaccination regimen with Ad26.ZEBOV and MVA-BN-filo Ebola vaccines: 12-month data from a phase 1 randomized clinical trial in Uganda and Tanzania. J Infect Dis. 2019;220(1):46‐56. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samai M, Seward JF, Goldstein ST, Mahon BE, Lisk DR, Widdowson MA, Jalloh MI, Schrag SJ, Idriss A, Carter RJ, et al. The Sierra Leone trial to induce a vaccine against Ebola: an evaluation of rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine tolerability and safety during the West Africa Ebola outbreak. J Infect Dis. 2018;217:S6‐15. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halperin SA, Arribas JR, Andrews CP, Chu L, Das R, Simon JK, Simon JK, Onorato MT, Liu K, Martin J, et al. Six-month safety data of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus ebola envelope glycoprotein vaccine in a phase 3 double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study in healthy adults. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1789‐98. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halperin SA, Das R, Onorato MT, Lui K, Martin J, Grant-Klein R, Nichols R, Coller B-A, Helmond FA, Simon JK, et al. Immunogenicity, lot consistency, and extended safety of rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine: a phase 3 double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study in healthy adults. J Infect Dis. 2019;220:1127‐35. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark DK, Xu R, Matassov D, Latham TE, Ota-Setlik A, Gerardi C, Luckay A, Witko SE, Hermida L, Higgins T, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a highly attenuated rVSVN4CT1-EBOVGP1 Ebola virus vaccines: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:455‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niemuth NA, Rudge TL Jr, Sankovich KA, Anderson MS, Skomrock ND, Badorrek CS, Sabourin CL. Method feasibility for cross-species testing, qualification, and validation of the Filovirus animal nonclinical group anti-Ebola virus glycoprotein immunoglobulin G enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for non-human primate serum samples. Plos ONE. 2020;15(10):e0241016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jüni P, Holenstein F, Sterne J, Bartlett C, Egger M. Direction and impact of language bias in meta-analysis of controlled trials: empirical study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:115–23. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request (alhassane.diallo@inserm.fr).