ABSTRACT

The aim was to summarize pneumococcal disease burden data among adults in Southern Europe and the potential impact of vaccines on epidemiology. Of 4779 identified studies, 272 were selected. Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) incidence was 15.08 (95% CI 11.01–20.65) in Spain versus 2.56 (95% CI 1.54–4.24) per 100,000 population in Italy. Pneumococcal pneumonia incidence was 19.59 (95% CI 10.74–35.74) in Spain versus 2.19 (95% CI 1.36–3.54) per 100,000 population in Italy. Analysis of IPD incidence in Spain comparing pre-and post- PCV7 and PCV13 periods unveiled a declining trend in vaccine-type IPD incidence (larger and statistically significant for the elderly), suggesting indirect effects of childhood vaccination programme. Data from Portugal, Greece and, to a lesser extent, Italy were sparse, thus improved surveillance is needed. Pneumococcal vaccination uptake, particularly among the elderly and adults with chronic and immunosuppressing conditions, should be improved, including shift to a higher-valency pneumococcal conjugate vaccine when available.

KEYWORDS: Pneumococcal disease burden, pneumococcal vaccine, PCV13, incidence, surveillance, adults, Spain, Italy, Greece, Portugal

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae infections are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and pose a major threat to public health.1 S. pneumoniae produces a polysaccharide capsule essential for its pathogenicity, serving as a virulence factor that hampers host immune clearance mechanisms.2 Currently, there are up to 100 recognized polysaccharide serotypes.3 Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) have successfully targeted several of them reducing the risk of infection by conferring serotype-specific protection.

Streptococcus pneumoniae causes a spectrum of invasive diseases, including sepsis, meningitis, and bacteremic pneumonia,4 and is the most frequent causative agent identified in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).5 Children under 5 years of age, the elderly population, and people with respiratory disease, diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and immunosuppression are at greater risk of pneumococcal disease.6

The true burden of pneumococcal disease remains undetermined in Europe. Despite the existence of a European enhanced surveillance of the invasive pneumococcal disease, notification rates vary markedly among countries. Apart from diverse population characteristics, the variations in the notification rate are most likely due to differences in medical and surveillance practices, and diverse implementation of pneumococcal vaccination (e.g., date of introduction, vaccine type, and vaccination schedules and policies).7 These differences particularly relate to CAP, as prevalence estimates among adults differ across settings and are affected by under-detection.8

In 2001, the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) was first authorized for its use in children in Europe, and the authorization was extended to the ten-, and thirteen-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV10/PCV13) in mid-2010. PCV13 was licensed in 2012 as the first pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for adults. In the Community-Acquired Pneumonia Immunization Trial (CAPiTA study), PCV13 showed an efficacy of 75% in preventing the first vaccine-type IPD episode, whereas efficacy against vaccine-type noninvasive pneumococcal pneumonia was estimated at 45%,9 and at 70% in a real-world effectiveness study.10

Many of the European countries have issued national guidelines for pneumococcal vaccination in adults. Guidelines are either age-based or risk-based11 with Southern European countries, such as Spain, Greece, and Italy implementing advanced age-based PCV13 recommendations at the national level or for many of their regions.12–14 However, PCV13 uptake among adults is still modest in those countries.15,16

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to summarize the evidence of the burden of pneumococcal disease among adults in Southern European countries (Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece).

Methods

This manuscript reports a systematic review of observational studies and was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.17 For the formulation of the PICO question (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome), the CoCoPop (Condition, Context, Population) model was used.18

Search strategy

A comprehensive search was performed in MEDLINE through OVID, EMBASE, SCOPUS, and SCIELO databases. To search for gray literature, Open Grey and OpenDOAR databases were included. Search terms were (“Streptococcus pneumoniae” OR pneumococcus OR pneumococcal infection) AND (meningitis OR pneumonia OR bacteremia OR “invasive pneumococcal disease”) AND (epidemiolog* OR prevalence OR incidence) LIMITS ([1990– 2019] AND [Spain, Portugal, Greece, Italy]). No language restrictions were applied to the search. Additional articles were identified and retrieved from references of found articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The review included observational studies (including prospective, retrospective, registry-, and population-based designs) according to the following criteria: (1) studies containing information about adult patients (≥18 years of age); (2) published between 1990 and 2019; (3) referring to settings located in Spain, Italy, Portugal or Greece; (4) studies containing information concerning invasive pneumococcal disease or CAP; and (5) articles reporting on pneumococcal disease prevalence, pneumococcal disease incidence, or vaccine-type related incidence [PCV7, PCV13 or the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23)].

It excluded studies that did not contain information on pneumococcal disease cases; that addressed pneumococcal disease cases having diagnostics other than pneumonia or isolation of S. pneumoniae from a normally sterile site; studies not including adult patients or outside the publication timeframe (1990–2019), or studies that did not have information on prevalence or incidence of pneumococcal disease.

Study selection and data extraction

After deduplication, titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers using the selection criteria. Then, full-text article screening was carried out and the following data were extracted: age group of patients (adult or elderly), time frame of study, country of study, pneumococcal disease type, number of patients with condition and number of them being pneumococcal, incidence rates, number of cases attributed to any of the vaccine serotypes and conditions that might increase susceptibility to pneumococcal infection (i.e., cancer, diabetes, immunosuppression, HIV infection, chronic kidney disease, cirrhosis, COPD). Age cutoffs of either 60 or 65 years were used to define the “elderly” age group.19

Any disagreement between the two reviewers was resolved after discussion and reaching consensus based on the predefined selection criteria.

The quality of the articles was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute´s Critical Appraisal Tool for prevalence/incidence systematic reviews. This Critical Appraisal Tool provides a checklist that covers nine domains: appropriateness of sample frame, recruitment of participants, adequacy of sample size, description of study subjects and setting, coverage of identified samples, valid methods for identification of the condition, a standardized and reliable measurement of the condition, appropriateness of the statistical analysis, and adequacy of the response rate.18,20

Data analysis

A pooled analysis of the included papers was performed, and a quantitative synthesis and meta-analyses were undertaken. Prevalence was expressed as the percentage of cases attributed to pneumococcus among all the cases of the disease, and incidence was expressed as cases per 100,000 population. Meta-analyses of the values expressed as a proportion were conducted using the metaprop package in R software (v.3.6.1). Proportions were treated by double arcsin transformation.21 Random effects models were fitted for the global effect size as significant heterogeneity across studies was detected.

Subgroup analyses were pre-specified for different conditions and countries and were included if enough data was available for the indicated subgroup. IPD incidence was also analyzed in subgroups to evaluate differences in reported serotypes causing disease. The year of marketing approval for each vaccine in the different countries was used as cutoff to compare incidence between the pre- (2001 for PCV7, and 2010 for PCV13), and post-vaccine introduction periods. If a manuscript contained values for different times of analysis but that occurred in the same segment respect to the cutoff (for example, both occurred after some vaccine introduction), duplicated labels can appear due to values coming from the same study but from different times of measurement.

To assess the impact of several covariates on estimates from the meta-analyses, a meta-regression method was utilized. Similar to a conventional regression, this method calculates a coefficient for each variable included in the analysis. This coefficient could be either positive, indicating that the estimate value increases as the predictor value increases, or negative, demonstrating a negative correlation, meaning that the estimate value decreases as the predictor value increases.

Results

Study characteristics

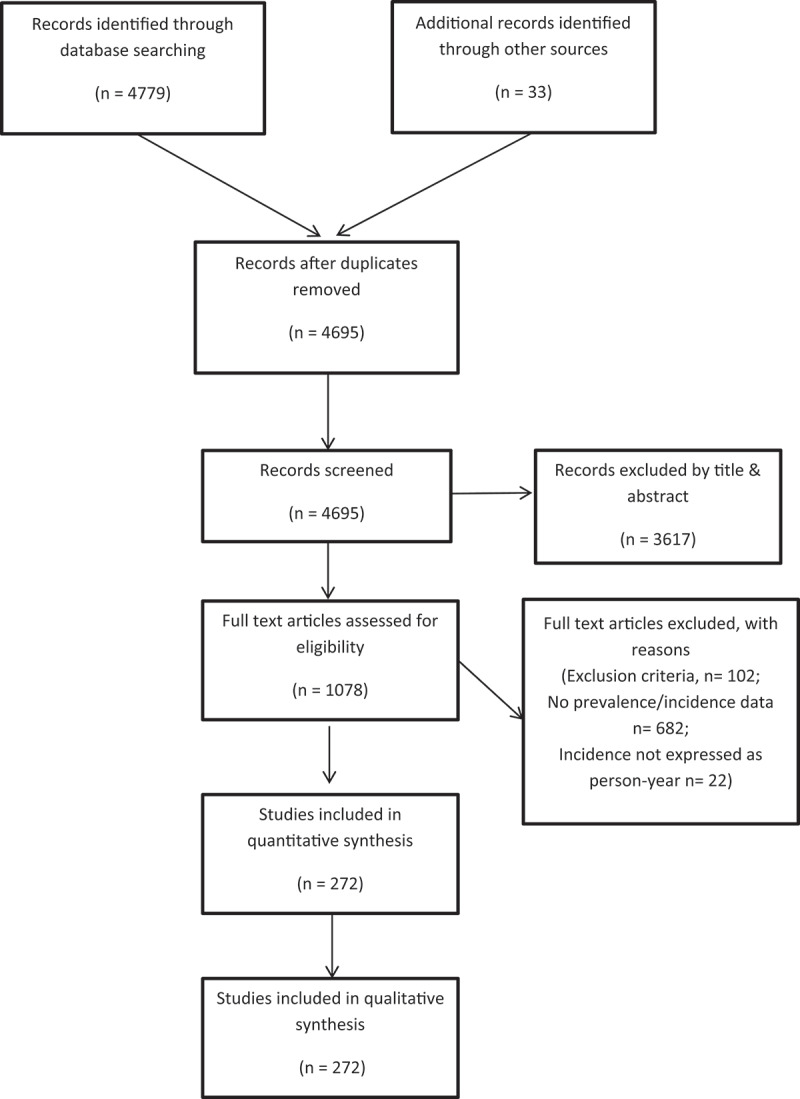

Of the 4779 screened studies, 272 were selected according to the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). From these, 232 records were obtained for prevalence analysis, with 182 containing information about pneumonia, 31 about bacteremia, 18 about meningitis and 1 about peritonitis; 108 records were retrieved for the incidence analysis, with 59 about IPD, 15 about pneumonia, 13 about bacteremia, 13 on meningitis and 8 related to other sites.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Information on prevalence were more frequently identified from studies carried out in hospital settings and incidence data were mostly provided by population-, or database-based studies. Most of the studies had an adequate level of quality, although in some studies there was a lack of representativeness of the sample or the information about methods used to diagnose the different conditions was missing.

Funnel plots to assess publication bias showed great variability, as expected from observational studies, with some deviation toward greater values.

The characteristics of the included studies are described in the online supplement (Supplemental material).16,22–286

Prevalence and incidence of pneumococcal disease in Southern European countries

Invasive pneumococcal disease

Frequency of IPD infections was rarely reported as prevalence. Therefore, only IPD incidence data were analyzed. Incidence of IPD was only available for Spain and Italy (Table 1) and no articles were retrieved from Portugal or Greece. The pooled analysis showed significant differences between Spain and Italy, with an incidence of 15.08 per 100,000 population (95% CI 11.01–20.65) in Spain and 2.56 per 100,000 population (95% CI 1.54–4.24) in Italy. Italy contributed with fewer records, but its pooled estimate had a narrow confidence interval (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary values for incidence of pneumococcal disease in Southern European countries*

| Pneumococcal disease type | Country | Number of records | Incidence (cases per 100.000 person-years) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPD | Overall | 59 | ||

| Spain | 50 | 15.08 | 11.01–20.65 | |

| Italy | 9 | 2.56 | 1.54–4.24 | |

| Portugal | 0 | - | - | |

| Greece | 0 | - | - | |

| Bacteremia | Overall | 13 | - | - |

| Spain | 13 | 4.13 | 2.38–7.20 | |

| Italy | 0 | - | - | |

| Portugal | 0 | - | - | |

| Greece | 0 | - | - | |

| Pneumonia | Overall | 15 | ||

| Spain | 13 | 19.59 | 10.74–35.74 | |

| Italy | 2 | 2.19 | 1.36–3.54 | |

| Portugal | 0 | - | - | |

| Greece | 0 | - | - | |

| Meningitis | Overall | 13 | ||

| Spain | 11 | 1.22 | 0.86–1.73 | |

| Italy | 2 | 2.12 | 0.58–7.71 | |

| Portugal | 0 | - | - | |

| Greece | 0 | - | - |

*Random effects summary estimates from meta-analyses.

Pneumococcal pneumonia

Spain had the highest prevalence of pneumococcal pneumonia with a prevalence of 19% (95% CI 17%-20%) (Table 2) followed by Portugal with 11% (95% CI 5%-18%), Italy with 8% (95% CI 7%-9%), and Greece with 5% (95% CI 2%-10%). Differences were only statistically significant for Spain compared to Italy and Greece, whereas the confidence intervals partially overlapped for Spain and Portugal (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary values for prevalence of pneumococcal disease in Southern European countries*

| Pneumoccocal disease type | Country | Number of records | Prevalence | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteremia | Overall | 31 | 6% | 4%-8% |

| Spain | 29 | 6% | 4%-8% | |

| Italy | 2 | 5% | 0%-24% | |

| Portugal | 0 | - | - | |

| Greece | 0 | - | - | |

| Pneumonia | Overall | 182 | 16% | 15%-18% |

| Spain | 140 | 19% | 17%-20% | |

| Italy | 26 | 8% | 7%-9% | |

| Portugal | 12 | 11% | 5%-18% | |

| Greece | 4 | 5% | 2%-10% | |

| Noninvasive pneumonia | Overall | 31 | 64% | 56%-71% |

| Spain | 28 | 64% | 55%-71% | |

| Italy | 2 | 77% | 53%-95% | |

| Portugal | 1 | 40% | 21%-60% | |

| Meningitis | Overall | 18 | 25% | 17%-35% |

| Spain | 11 | 21% | 9%-35% | |

| Italy | 6 | 33% | 23%-42% | |

| Portugal | 1 | 35% | 29%-42% | |

| Greece | 0 | - | - |

*Random effects summary estimates from meta-analyses.

The analysis of the pneumococcal pneumonia incidence data showed an incidence of 19.59 per 100,000 population (95% CI 10.74–35.74) for Spain whereas Italy presented a lower incidence at 2.19 per 100,000 population (95% CI 1.36–3.54). The difference was statistically significant (Table 1). No information was retrieved on pneumococcal pneumonia incidence from Portugal or Greece.

Noninvasive pneumococcal pneumonia

Noninvasive pneumococcal pneumonia was defined as community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) for which the pneumococcus was isolated from sites other than normally sterile sites. The selected studies clearly stated that pneumonia was noninvasive.

Overall, 31 studies were selected, and prevalence was 64% (95% CI 55%-71%), 77% (95% CI 53%-95%), and 40% (95% CI 21%-60%) for Spain, Italy, and Portugal, respectively. Again, differences between any two of the four countries were not statistically significant.

Bacteremia

Portugal and Greece did not contribute records to the pneumococcal bacteremia prevalence pooled estimate whilst Spain had a prevalence of 6% (95% CI 4%-8%) and Italy of 5% (95% CI 0%-24%). Differences were not statistically significant and only two records for Italy were captured (Table 2), thus a higher number of records would be desirable for sound comparisons.

In relation to incidence, Spain was the only country with studies on pneumococcal bacteremia and it was estimated at 4.13 per 100,000 population (95% CI 2.38–7.20).

Meningitis

The summary values for pneumococcal meningitis prevalence were 35% (95% CI 29%-42%), 33% (95% CI 23–42%), and 21% (95% CI 9–35%) for Portugal, Italy, and Spain, respectively. Differences between countries were not statistically significant.

Pneumococcal meningitis incidence was 1.22 per 100,000 population (95% CI 0.86–1.73) for Spain, and 2.12 per 100,000 population (95% CI 0.58–7.71) for Italy with overlapping confidence intervals.

Incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease caused by vaccine serotypes

Data analysis about incidence of IPD stratified by vaccine type was only performed for Spain, as information from Portugal and Greece was not found and there was only one article from Italy. Information on other clinical presentations was very scarce and excluded from the analysis.

The pooled analysis was carried out for the general (≥18 years of age) and the elderly (≥60 years or ≥65 years of age) populations.

Among adults 18 years of age and older, the analysis showed a decrease in PCV7 type IPD incidence from the pre-vaccine introduction period to the post-vaccine introduction period: from 8.00 per 100,000 population (95% CI 3.73–17.18) to 2.85 per 100,000 population (95% CI 2.06–3.94), respectively, and nearly reached statistical significance (Table 3). In the same age group, a non-significant decrease in PCV13 type IPD incidence was observed between the pre-vaccine introduction period and the post-marketing period, from 10.45 per 100,000 population (95% CI 7.12–15.32) to 4.92 per 100,000 population (95% CI 3.17–7.64), respectively. Comparing the pre- and post-periods, non-PCV13 type (serotypes not included in PCV13) IPD incidence increased from 5.25 per 100,000 population (95% CI 3.16–8.74) to 6.79 per 100,000 population (95% CI 4.15–11.12), although confidence intervals overlapped.

Table 3.

Distribution of IPD incidence by vaccine type pre-, and post-marketing introduction among the general and elderly populations in Spain

| IPD vaccine type | Year of introduction of the vaccine | Period | Ns | Nr | Incidence (cases per 100.000) | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 18 years | ||||||

| PCV7 | 2001 | Pre | 4 | 6 | 8.00 | 3.73– 17.18 |

| Post | 12 | 40 | 2.85 | 2.06– 3.94 | ||

| PCV13 | 2010 | Pre | 7 | 14 | 10.45 | 7.12– 15.32 |

| Post | 6 | 15 | 4.92 | 3.17– 7.64 | ||

| Non-PCV13 | 2010 | Pre | 4 | 9 | 5.25 | 3.16– 8.74 |

| Post | 5 | 13 | 6.79 | 4.15– 11.12 | ||

| ≥ 60 years or ≥ 65 years | ||||||

| PCV7 | 2001 | Pre | 3 | 3 | 19.10 | 17.69– 20.62 |

| Post | 10 | 21 | 5.50 | 3.84– 7.86 | ||

| PCV13 | 2010 | Pre | 6 | 8 | 17.10 | 13.64– 22.96 |

| Post | 6 | 8 | 9.55 | 6.97– 13.09 | ||

| Non-PCV13 | 2010 | Pre | 4 | 5 | 9.63 | 7.18– 12.91 |

| Post | 5 | 7 | 14.04 | 10.41– 18.94 |

PCV7: hepta-valent pneumococcal conjugate Pre: pre-vaccine introduction period

PCV13: thirteen-valent pneumococcal conjugatePost: post-vaccine introduction period

Non-PCV13: non-thirteen-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine type Ns: number of studies; Nr: number of records

After age stratification, among the elderly group (≥60 years or ≥65 years of age), there was a significant decrease in PCV7 type IPD incidence from 19.10 per 100,000 population (95% CI 17.69–20.62) to 5.50 per 100,000 population (95% CI 3.84–7.86) comparing the two time periods. PCV13 type IPD incidence also declined from 17.10 per 100,000 population (95% CI 13.64–22.96) to 9.55 per 100,000 population (95% CI 6.97–13.09) (Table 3), reaching statistical significance. However, non-PCV13 type IPD incidence increased non-significantly from 9.63 per 100,000 population (95% CI 7.18–12.91) in the pre-vaccine introduction period to 14.04 per 100,000 population (95% CI 10.41–18.94) in the post-period.

Case fatality ratio

A total of 92 papers contained information that allowed the calculation of the case fatality ratio (CFR) among patients suffering from pneumococcal disease. Overall CFR was 11% (95% CI 10%-12%), 12% (95% CI 10%-14%), and 8% (95% CI 3%-16%) for Spain, Italy, and Portugal, respectively. Differences between countries were not statistically significant.

The CFR analysis by pneumococcal disease type showed statistically significant differences between IPD and pneumonia, at 15% (95% CI 12%-19%) and 8% (95% CI 6%-9%), respectively. CFR due to meningitis at 14% (95% CI 10%-18%) did not differ from bacteremia at 17% (95% CI 11%-23%).

Risk factors for pneumococcal disease

To identify the risk factors for pneumococcal pneumonia prevalence, a meta-regression model was fitted including the country of study, age group, PCV13 authorization period and PPV23 vaccination as covariates. Data coming from Italy and old age (≥60 years or ≥65 years of age) were found to be positive predictors, although non-significantly. PCV13 post-authorization period appeared as negative predictor (albeit non-significantly) whereas both PPV23-vaccinated and PPV23-non-vaccinated were also negative predictors. This apparent contradiction may relate to the fact that those PPV23 studies showed a low prevalence of pneumococcal pneumonia, independently of the vaccination status.

A meta-regression sub-analysis for meningitis prevalence in Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece indicated that HIV-positive status was a significant positive predictor, whereas immunosuppressed population, solid organ transplant patients, and data from Spain were negative predictors (the first two being significant).

A meta-regression of overall bacteremia prevalence indicated that mechanical ventilation was the only negative significant predictor. Other negative predictors were old age (≥60 years or ≥65 years of age), immunosuppressed patients, and solid organ transplant patients. The only positive predictor was HIV-positive status, being marginally non-significant.

Discussion

This systematic review highlights the high burden of pneumococcal disease among adults as well as the changes in the epidemiology of pneumococcal disease in Southern European countries. This review has revealed differences in the prevalence and incidence of pneumococcal disease between the Southern European countries. These differences have been previously identified, particularly in relation to the prevalence of CAP in adults, and hold true after adjusting for potential confounders, including patient characteristics, diagnostic tests, antimicrobial resistance, and healthcare setting.8 Geographical variations in the epidemiology of pneumococcal disease have been reported as most likely due to selection of patients, or blood-culture practices,287 but also the spread of resistant clones may have contributed to these differences.288 Apart from clinical practices and patients characteristics, decreasing trends in the incidence of pneumococcal bacteremia or meningitis have been associated with improvement in socioeconomic factors (i.e., reduced crowding), the widespread use of antibiotics, and the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines289 in the European countries.7 Records from Portugal, Greece and to some extent from Italy were scarce in this review and it may well correspond to incomplete surveillance systems and not fully developed diagnostics and ascertainment strategies.290–292

This review unveiled significant differences in incidence of IPD between Spain and Italy, with Spain showing a larger disease burden. Divergence in IPD notification rates between both countries has remained constant since the inception of the European IPD surveillance programme.293 The potential reasons have been profusely explained above. Similarly, pneumonia incidence among adults in Spain was significantly higher compared to Italy and consistent with that in other reports.294

A sub-analysis of noninvasive pneumococcal pneumonia revealed a high prevalence in Italy, Spain, and Portugal (77%, 64%, and 40%, respectively). The considerable high prevalence in Italy may reflect that there were only two records identified and the study included special populations, either injection drug users including HIV-positive patients42 or a general HIV-positive cohort.121 Papers from Spain mainly included elderly populations, and HIV or COPD patients.49,263,276,278,279,282

There were no differences in meningitis incidence between Spain and Italy and this was consistent with published figures.295 Unfortunately, the selected articles did not contain enough information to assess pneumococcal serotype distribution before and after the different pneumococcal conjugate vaccines introduction.

Data on incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease from Spain allowed to analyze vaccine-type evolution comparing the pre-, and post-vaccine introduction periods. Among the overall adult population, PCV7 and PCV13 type IPD incidence declined non-significantly between the two periods. These differences were larger and statistically significant after stratifying by age (≥60 years or ≥65 years of age). In the context of recent introduction of PCV13 and a low PCV13 uptake among adults, this decrease may be attributed to indirect effects of the pediatric pneumococcal immunization programmes as reported for other settings.152,296,297 A recent analysis points to the impact of pneumococcal childhood vaccination on the reduction of adult PCV13 type IPD in Spain before the implementation of adult vaccination programmes.298 Regarding any potential impact of direct vaccination of adults with PPV23, we were not able to explore, because there was identified only one article referring to PPV23-specific serotypes, and we decided not to include it in this analysis. Conversely, several articles with information about disease caused by non-PCV13 serotypes were included in this analysis.

The analysis also identified an increasing trend in non-PCV13 type IPD incidence comparing the pre-, and post-vaccine introduction periods, both for the overall adult population and for the elderly. These epidemiological changes showing the emergence of non-vaccine serotypes have been attributed to the implementation of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, but this is a complex phenomenon and there are a number of other factors implicated, such as selective pressure of antibiotics and carriage and transmission dynamics. This holds true particularly among children, who are affected by pneumococcal carriage and transmission due to factors, such as child care attendance, crowding, or birth rate.299 Whether the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines is the sole cause for serotype replacement remains unclear since there are regions with high serotype replacement rate but low vaccine uptake.300 In addition, regional differences in the reporting systems and other non-vaccine environmental factors295 may have contributed to this phenomenon.

Published data show that the case fatality ratio for pneumococcal disease overall has been estimated at 15% whereas it was as high as 10–30% among pneumococcal meningitis patients.301 Results from our review allineate with those figures and do not differ among Spain, Italy, and Portugal at 11%, 12%, and 8%, respectively. As expected, CFR of invasive disease, either overall IPD, meningitis or bacteremia, was considerably higher compared to pneumonia CFR.

An assessment of the risk factors for pneumococcal pneumonia prevalence demonstrated that older age and articles from Italy correlated with higher prevalence. In the elderly, pneumococcal pneumonia is a key contributor to the burden of pneumococcal disease. The presence of underlying conditions and phenomena such as immunosenescence and inflammageing is associated with an increased risk for pneumococcal pneumonia in this age group.302,303 The meta-regression of studies that contained information on PCV13 from the post-authorization period, showed an inverse correlation with pneumococcal pneumonia prevalence pointing to the ability of PCV13 to protect against vaccine-type pneumococcal pneumonia.

HIV-positive status correlated with higher prevalence of pneumococcal meningitis and bacteremia as already highlighted in a recent review.304 In contrast, immunosuppressed patients and patients with solid organ transplant correlated inversely with pneumococcal bacteremia and meningitis. This aligns with some studies that have showed that patients using immunosuppressive treatment are less likely to present with typical characteristics of meningitis, have less alterations in their cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and often their CFS culture predominantly yields atypical causative microorganisms.305

Previous studies have identified younger age as an independent risk factor for bacteremia in patients with community-acquired pneumonia306,307; although statistically non-significantly, our results are in agreement with this. The reasons for younger patients being at higher risk of bacteremia still need to be elucidated. Pneumococcal vaccination and serotype distribution may be partly responsible for it. The pneumococcal vaccines are recommended in the Southern European countries, depending on the regions, for adults aged ≥60 or ≥65 years to prevent invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia. Younger adults are not expected to be vaccinated against pneumococcal disease, except for those with certain at-risk conditions, likely putting them at a higher risk for pneumococcal bacteremia. Unfortunately, sparsity of data on serotype distribution among bacteremic cases did not allow an in-depth analysis of its impact on age distribution. Mechanical ventilation has been associated with pneumococcal bacteremic pneumonia.306 Our data are not consistent with this finding since we found that mechanical ventilation negatively correlated with bacteremia. However, respiratory complications (including mechanical ventilation) have been associated to older age in bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia.308

This review has strengths and limitations. One key strength of the review is that it consisted of a large number of records for Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Greece, including gray literature sources. One limitation of our study is the heterogeneity observed in the meta-analyses. We applied a quality appraisal tool, and fitted random effects models and subgroup analyses but among the research community, there is still no consensus on the optimal methodology for the conduct of systematic reviews and meta-analyses for observational studies.309,310 Additionally, data from Portugal, Greece, and Italy were scant which may have resulted in the underestimation of the true burden of pneumococcal disease in those countries.

Despite these limitations, this review aims to trigger awareness among policy and decision makers of the need to inform policies and strategies to tackle pneumococcal disease among adults in the Southern European countries.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, the results of this review point to a considerable pneumococcal disease burden and PCV13 type IPD burden among adults even with the indirect effects of the pediatric PCV13 vaccination programmes. It has also unveiled an increase in the incidence of non-PCV13 serotypes over time. Based on this review, we suggest it is worth considering the expansion of pneumococcal vaccination recommendations to the elderly and adults with chronic diseases, HIV-positive, and other immunosuppressing conditions.

Moreover, improving surveillance of pneumococcal disease and the harmonization of reporting systems are warranted among the Southern European countries to ensure close monitoring of changes in the epidemiology of the pneumococcal disease, and the impact of vaccines.

At present, next-generation pneumococcal conjugate vaccines with a wider serotype coverage are being developed. Therefore, switching to extended-valency pneumococcal conjugate vaccines when they become available would be advisable. At the same time, every effort should be made to take advantage of existing recommendations in the Southern European countries and to enhance pneumococcal vaccination uptake both in the elderly and in adults with comorbidities that put them at increased risk for pneumococcal disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Francisco Andrés Fernández and his team from Content Medicine for conducting the systematic review and providing insights in the interpretation of the results.

Funding Statement

Editorial support was provided by Qi Yan at Pfizer, Inc. and was funded by Pfizer.

Highlights

Pneumococcal disease among adults poses a significant burden on Southern European countries

Indirect effects of childhood pneumococcal vaccination are noted among adults in Spain

Pneumococcal surveillance and reporting need improvement in Italy, Greece, and Portugal

Changes in epidemiology suggest the need for higher-valency conjugate vaccines

Contributors

A. Navarro-Torné designed, interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript; Eva Agostina Montuori, Vasiliki Kossyvaki, and Cristina Méndez critically revised the manuscript, contributed comments, and gave final approval to the manuscript.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

All author(s) are Pfizer employees and may hold company stocks.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1923348

References

- 1.Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, Casey DC, Charlson FJ, Chen AZ, Coates MM, et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paton JC, Trappetti C.. Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7(2):2. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0019-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganaie F, Saad JS, McGee L, van Tonder AJ, Bentley SD, Lo SW, Gladstone RA, Turner P, Keenan JD, Breiman RF, et al. A new pneumococcal capsule type, 10D, is the 100th serotype and has a large cps fragment from an oral Streptococcus. mBio. 2020;11(3):e00937–20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00937-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch JP, Zhanel GG.. Streptococcus pneumoniae: epidemiology, risk factors, and strategies for prevention. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30(2):189–209. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welte T, Torres A, Nathwani D. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe. Thorax. 2012;67(1):71–79. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.129502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalmers JD, Campling J, Dicker A, Woodhead M, Madhava H. A systematic review of the burden of vaccine preventable pneumococcal disease in UK adults. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navarro-Torné A, Dias JG, Quinten C, Hruba F, Busana MC, Lopalco PL, Gauci AJA, Pastore-Celentano L. European enhanced surveillance of invasive pneumococcal disease in 2010: data from 26 European countries in the post-heptavalent conjugate vaccine era. Vaccine. 2014;32(29):3644–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rozenbaum MH, Pechlivanoglou P, van der Werf TS, Lo-Ten-Foe JR, Postma MJ, Hak E. The role of Streptococcus pneumoniae in community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(3):305–16. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1778-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonten MJM, Huijts SM, Bolkenbaas M, Webber C, Patterson S, Gault S, Van Werkhoven CH, Van Deursen AMM, Sanders EAM, Verheij TJM, et al. Polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(12):1114–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaughlin JM, Jiang Q, Isturiz RE, Sings HL, Swerdlow DL, Gessner BD, Carrico RM, Peyrani P, Wiemken TL, Mattingly WA, et al. Effectiveness of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia in older US adults: a test-negative design. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(10):1498–506. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnave C, Mertens D, Peetermans W, Cobbaert K, Ghesquiere B, Deschodt M, Flamaing J. Adult vaccination for pneumococcal disease: a comparison of the national guidelines in Europe. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38(4):785–91. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03485-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greek Ministry of Health . Greek national immunization program for adults 2018–2019. 2020. [accessed 2020 Sept 14]. https://www.moh.gov.gr/articles/health/dieythynsh-dhmosias-ygieinhs/emboliasmoi/ethniko-programma-emboliasmwn-epe-enhlikwn/6356-ethniko-programma-emboliasmwn-epe-enhlikwn-2018-2019.

- 13.Ministry of Health Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare . Vaccination schedules in the Autonomous Communities in Spain. 2020. [accessed 2020 Sept 14]. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/Calendario_CCAA.htm.

- 14.Italian Ministry of Health . National immunization plan 2017–2019. 2017. [accessed 2020 Sept 16]. http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.pdf.

- 15.Bertsias A, Tsiligianni IG, Duijker G, Siafakas N, Lionis C. Studying the burden of community-acquired pneumonia in adults aged ≥50 years in primary health care: an observational study in rural Crete, Greece. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24(1):14017. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Càmara J, Marimón JM, Cercenado E, Larrosa N, Quesada MD, Fontanals D, Cubero M, Pérez-Trallero E, Fenoll A, Liñares J, et al. Decrease of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in adults after introduction of pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine in Spain. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–53. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. WHO . Proposed working definition of an older person in Africa for the MDS Project. 2002. [accessed 2020 Aug 3]. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/.

- 20.Joanna Briggs Institute . Critical appraisal checklist for prevalence studies. 2017. [accessed 2020 Aug 3]. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools.

- 21.Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:974–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdallah Kassab N, Saiz Sánchez-Buitrago M, Pérez Jaén A, Castellanos González M, Ruiz-Giardín J. Bacteriemias en pacientes adultos que acuden a urgencias, estudio descriptivo años 2012–2013. Universidad Rey Juan Carlos; 2014. [accessed 2020 May 21]. https://eciencia.urjc.es/handle/10115/13140.

- 23.Adamuz Tomás J, Viasus D, Campreciós Rodríguez P, Cañavate Jurado O, Jiménez Martínez E, Isla Pera MP, García-vidal C, Carratalà J. A prospective cohort study of healthcare visits and rehospitalizations after hospital discharge in community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2011;16(7):1119–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aguilar-Guisado M, Jiménez-Jambrina M, Espigado I, Rovira M, Martino R, Oriol A, Borrell N, Ruiz I, Martín-Dávila P, de la Cámara R, et al. Pneumonia in allogeneic stem cell transplantation recipients: a multicenter prospective study: pneumonia in allogeneic HSCT recipients. Clin Transplant. 2011;25(6):E629–E38. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almirall J, Morat I, Riera F, Verdaguer A, Priu R, Coll P, Vidal J, Murgui L, Valls F, Catalan F, et al. Incidence of community-acquired pneumonia and Chlamydia pneumoniae infection: a prospective multicentre study. Eur Respir J. 1993;6(1):14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almirall J, Bolibar I, Vidal J, Sauca G, Coll P, Niklasson B, Bartolome M, Balanzo X. Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based study. Eur Respir J. 2000;15(4):757–63. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15d21.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almirall J, Boixeda R, Bolíbar I, Bassa J, Sauca G, Vidal J, Serra-Prat M, Balanzó X. Differences in the etiology of community-acquired pneumonia according to site of care: a population-based study. Respir Med. 2007;101(10):2168–75. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almirall J, Rofes L, Serra-Prat M, Icart R, Palomera E, Arreola V, Clavé P. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a risk factor for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(4):923–28. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00019012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Álvarez Rodríguez V. Manejo en urgencias de las neumonías adquiridas en la comunidad que requieren ingreso hospitalario. Madrid (Spain): Universidad Complutense de Madrid; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Álvarez-Lerma F, Palomar M, Martínez-Pellús A, Álvarez-Sánchez B, Pérez-Ortiz E, Jordá R. Aetiology and diagnostic techniques in intensive care-acquired pneumonia: a Spanish multi-centre study. Clin Intensive Care. 1997;8(4):7. doi: 10.3109/tcic.8.4.164.170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amodio E, Costantino C, Boccalini S, Tramuto F, Maida CM, Vitale F. Estimating the burden of hospitalization for pneumococcal pneumonia in a general population aged 50 years or older and implications for vaccination strategies. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(5):1337–42. doi: 10.4161/hv.27947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ardanuy C, Tubau F, Pallares R, Calatayud L, Domínguez María A, Rolo D, Grau I, Martín R, Liñares J. Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among adult patients in Barcelona before and after pediatric 7‐valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction, 1997–2007. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(1):57–64. doi: 10.1086/594125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arencibia Jiménez M, Navarro Gracia JF, Delgado de los Reyes JA, Pérez Torregrosa G, López Parra D, López García P. Missed opportunities in antipneumococcal vaccination. Can something more be done for prevention? Arch Bronchoneumol 2014;50:93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Artiles F, Horcajada I, Cañas AM, Álamo I, Bordes A, González A, Santana M, Lafarga B. Aspectos epidemiológicos de la enfermedad neumocócica invasiva antes y después del uso de la vacuna neumocócica conjugada en Gran Canaria. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2009;27(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balaguer Rosello A, Bataller L, Lorenzo I, Jarque I, Salavert M, González E, Piñana JL, Sevilla T, Montesinos P, Iacoboni G, et al. Infections of the central nervous system after unrelated donor umbilical cord blood transplantation or human leukocyte antigen–matched sibling transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(1):134–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baldo V, Cocchio S, Gallo T, Furlan P, Clagnan E, Zotto SD, Saia M, Bertoncello C, Buja A, Baldovin T, et al. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination: a retrospective study of hospitalization for pneumonia in North-East Italy. J Prev Med Hyg. 2016;57(2):E61–E8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baldovin T, Russo F, Lazzari R, Bertoncello C, Furlan P, Cocchio S, Baldo V. Surveillance of invasive pneumococcal diseases in Veneto region, Italy. Pneumonia. 2014;3:154. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baldovin T, Lazzari R, Russo F, Bertoncello C, Buja A, Furlan P, Cocchio S, Palù G, Baldo V. A surveillance system of invasive pneumococcal disease in North-Eastern Italy. Ann Ig. 2016;28(1):15–24. doi: 10.7416/ai.2016.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartoletti M. End-stage liver disease: the hidden immunosuppressive condition. From an epidemiological update to therapeutic management models. Bologna (Italy): University of Bologna; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bello S, Mincholé E, Fandos S, Lasierra AB, Ruiz MA, Simon AL, Panadero C, Lapresta C, Menendez R, Torres A, et al. Inflammatory response in mixed viral-bacterial community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14(1):123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bermejo-Martin JF, Cilloniz C, Mendez R, Almansa R, Gabarrus A, Ceccato A, Torres A, Menendez R. Lymphopenic community acquired pneumonia (l-CAP), an immunological phenotype associated with higher risk of mortality. EBioMedicine. 2017;24:231–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boschini A, Smacchia C, Di Fine M, Schiesari A, Ballarini P, Arlotti M, Gabrielli C, Castellani G, Genova M, Pantani P, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in a cohort of former injection drug users with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection: incidence, etiologies, and clinical aspects. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(1):107–13. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bouza E, Pintado V, Rivera S, Blázquez R, Muñoz P, Cercenado E, Loza E, Rodríguez-Créixems M, Moreno S. Nosocomial bloodstream infections caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11(11):919–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bouza E, Arenas C, Cercenado E, Cuevas O, Vicioso D, Fenoll A. Microbiologic workload and clinical significance of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated during one week in spain. Microbial Drug Resist. 2007;13(1):52–61. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2006.9997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruschini L, Fortunato S, Tascini C, Ciabotti A, Leonildi A, Bini B, Giuliano S, Abbruzzese A, Berrettini S, Menichetti F, et al. Otogenic meningitis: a comparison of diagnostic performance of surgery and radiology. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(2):1–7. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burgos J, Lujan M, Falco V, Sanchez A, Puig M, Borrego A, Fontanals D, Planes AM, Pahissa A, Rello J, et al. The spectrum of pneumococcal empyema in adults in the early 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(3):254–61. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burgos J, Falcó V, Borrego A, Sordé R, Larrosa MN, Martinez X, Planes AM, Sánchez A, Palomar M, Rello J, et al. Impact of the emergence of non-vaccine pneumococcal serotypes on the clinical presentation and outcome of adults with invasive pneumococcal pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(4):385–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pallares R, Viladrich PF, Liñares J, Cabellos C, Gudiol F. Impact of antibiotic resistance on chemotherapy for pneumococcal infections. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4(4):339–47. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Camon S, Quiros C, Saubi N, Moreno A, Marcos MA, Eto Y, Rofael S, Monclus E, Brown J, McHugh TD, et al. Full blood count values as a predictor of poor outcome of pneumonia among HIV-infected patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Capdevila O, Pallares R, Grau I, Tubau F, Liñares J, Ariza J, Gudiol F. Pneumococcal peritonitis in adult patients: report of 64 cases with special reference to emergence of antibiotic resistance. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(14):1742. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.14.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carabaña S, Pilar M. Presentación clínica, etiología y pronóstico de la bacteriemia extrahospitalaria (1998–2011). Madrid (Spain): Autonomous University of Madrid; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cardoso TC, Lopes LM, Carneiro AH. A case-control study on risk factors for early-onset respiratory tract infection in patients admitted in ICU. BMC Pulm Med. 2007;7(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Carlo A, Roda R, Rossi MR, Ceruti S, Ghinelli F, Libanore M. Attuali aspetti epidemiologici e clinici delle meningiti in un’area del Nord-Italia. Infez Med. 2000;3:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caro Orozco S. Elaboración de un modelo de predicción de bacteriemia en pacientes con neumonia comunitaria [Ph.D. Thesis]. Leida (Spain): University of Lleida; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carratalà J, Mykietiuk A, Fernández-Sabé N, Suárez C, Dorca J, Verdaguer R, Manresa F, Gudiol F. Health care–associated pneumonia requiring hospital admission: epidemiology, antibiotic therapy, and clinical outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(13):1393. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.13.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nuvials Casals X. Infecciones respiratorias relacionadas con la ventilación mecánica. Impacto en el uso de antimicrobianos. Barcelona (Spain): Autonomous University of Barcelona; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cascini S, Agabiti N, Incalzi RA, Pinnarelli L, Mayer F, Arcà M, Fusco D, Davoli M. Pneumonia burden in elderly patients: a classification algorithm using administrative data. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cazzadori A, Perri GD, Vento S, Bonora S, Fendt D, Rossi M, Lanzafame M, Mirandola F, Concia E. Aetiology of pneumonia following isolated closed head injury. Respir Med. 1997;91(4):193–99. doi: 10.1016/S0954-6111(97)90038-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ceccato A, Torres A, Cilloniz C, Amaro R, Gabarrus A, Polverino E, Prina E, Garcia-Vidal C, Muñoz-Conejero E, Mendez C, et al. Invasive disease vs urinary antigen-confirmed pneumococcal community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2017;151(6):1311–19. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ceccato A, Cilloniz C, Martin-Loeches I, Ranzani OT, Gabarrus A, Bueno L, Garcia-Vidal C, Ferrer M, Niederman MS, Torres A, et al. Effect of combined β-lactam/macrolide therapy on mortality according to the microbial etiology and inflammatory status of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2019;155(4):795–804. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ceccato A, Panagiotarakou M, Ranzani OT, Martin-Fernandez M, Almansa-Mora R, Gabarrus A, Bueno L, Cilloniz C, Liapikou A, Ferrer M, et al. Lymphocytopenia as a predictor of mortality in patients with ICU-acquired pneumonia. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):843. doi: 10.3390/jcm8060843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chiappini E, Inturrisi F, Orlandini E, de Martino M, de Waure C. Hospitalization rates and outcome of invasive bacterial vaccine-preventable diseases in Tuscany: a historical cohort study of the 2000–2016 period. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):396. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3316-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chiner E, Llombart M, Valls J, Pastor E, Sancho-Chust JN, Andreu AL, Sánchez-de-la-torre M, Barbé F. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and community-acquired pneumonia. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cilloniz C, Ewig S, Polverino E, Marcos MA, Esquinas C, Gabarrus A, Mensa J, Torres A. Microbial aetiology of community-acquired pneumonia and its relation to severity. Thorax. 2011;66(4):340–46. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.143982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cilloniz C, Torres A, Polverino E, Gabarrus A, Amaro R, Moreno E, Villegas S, Ortega M, Mensa J, Marcos MA, et al. Community-acquired lung respiratory infections in HIV-infected patients: microbial aetiology and outcome. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(6):1698–708. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00155813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cilloniz C, Albert RK, Liapikou A, Gabarrus A, Rangel E, Bello S, Marco F, Mensa J, Torres A. The effect of macrolide resistance on the presentation and outcome of patients hospitalized for Streptococcus pneumoniae Pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(11):1265–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201502-0212OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cilloniz C, Ewig S, Gabarrus A, Ferrer M, Puig de la Bella Casa J, Mensa J, Torres A. Seasonality of pathogens causing community-acquired pneumonia: seasonality of pathogens in CAP. Respirology. 2017;22(4):778–85. doi: 10.1111/resp.12978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cilloniz C, Ferrer M, Liapikou A, Garcia-Vidal C, Gabarrus A, Ceccato A, Puig de la Bellacasa J, Blasi F, Torres A. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in mechanically ventilated patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(3):1702215. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02215-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cillóniz C, Ewig S, Ferrer M, Polverino E, Gabarrús A, Puig de la Bellacasa J, Mensa J, Torres A. Community-acquired polymicrobial pneumonia in the intensive care unit: aetiology and prognosis. Critical Care. 2011;15(5):R209. doi: 10.1186/cc10444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cillóniz C, Ewig S, Polverino E, Muñoz-Almagro C, Marco F, Gabarrús A, Menéndez R, Mensa J, Torres A. Pulmonary complications of pneumococcal community-acquired pneumonia: incidence, predictors, and outcomes. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(11):1134–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cillóniz C, Ewig S, Menéndez R, Ferrer M, Polverino E, Reyes S, Gabarrús A, Marcos MA, Cordoba J, Mensa J, et al. Bacterial co-infection with H1N1 infection in patients admitted with community acquired pneumonia. J Infect. 2012;65(3):223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cillóniz C, Gabarrús A, Almirall J, Amaro R, Rinaudo M, Travierso C, Niederman M, Torres A. Bacteraemia in outpatients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(2):654–57. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01308-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cillóniz C, Ceccato A, de la Calle C, Gabarrús A, Garcia-Vidal C, Almela M, Soriano A, Martinez JA, Marco F, Vila J, et al. Time to blood culture positivity as a predictor of clinical outcomes and severity in adults with bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cillóniz C, Liapikou A, Martin-Loeches I, García-Vidal C, Gabarrús A, Ceccato A, Magdaleno D, Mensa J, Marco F, Torres A, et al. Twenty-year trend in mortality among hospitalized patients with pneumococcal community-acquired pneumonia. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ciruela P, Martínez A, Izquierdo C, Hernández S, Broner S, Muñoz-Almagro C, Domínguez À, Of Catalonia Study Group TMRS. Epidemiology of vaccine-preventable invasive diseases in Catalonia in the era of conjugate vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(3):681–91. doi: 10.4161/hv.23266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ciruela P, Broner S, Izquierdo C, Hernández S, Muñoz-Almagro C, Pallarés R, Jané M, Domínguez A. Invasive pneumococcal disease rates linked to meteorological factors and respiratory virus circulation (Catalonia, 2006–2012). BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):400. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ciruela P, Izquierdo C, Broner S, Muñoz-Almagro C, Hernández S, Ardanuy C, Pallarés R, Domínguez A, Jané M, Esteva C, et al. The changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease after PCV13 vaccination in a country with intermediate vaccination coverage. Vaccine. 2018;36(50):7744–52. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ciruela P, Broner S, Izquierdo C, Pallarés R, Muñoz-Almagro C, Hernández S, Grau I, Domínguez A, Jané M, Ciruela P, et al. Indirect effects of paediatric conjugate vaccines on invasive pneumococcal disease in older adults. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;86:122–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cisneros JM, Munoz P, Torre‐Cisneros J, Gurgui M, Rodriguez‐Hernandez MJ, Aguado JM, Echaniz A. Pneumonia after heart transplantation: a multiinstitutional study. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(2):324–31. doi: 10.1086/514649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cisterna R, Cabezas V, Gómez E, Busto C, Atutxa I, Ezpeleta C. Community-acquired bacteremia. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2001;14:369–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cobo Martínez F, Manchado Mañas P. Bacteriemia nosocomial: epidemiología y situación actual de resistencias a antimicrobianos. Rev Clin Esp. 2005;205(3):108–12. doi: 10.1157/13072966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Comes Castellano AM, Rodrigo JAL, Alonso AP, Pastor E, Sanz Valero M. Incidencia de las neumonías neumocócicas en el ámbito hospitalario en la comunidad valenciana durante el período 1995–2001. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2004;78(4):9. doi: 10.1590/S1135-57272004000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cosentini R, Blasi F, Raccanelli R, Rossi S, Arosio C, Tarsia P, Randazzo A, Allegro L. Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia: a Possible Role for Chlamydia pneumoniae. Respiration. 1996;63(2):61–65. doi: 10.1159/000196519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Crisafulli E, Menéndez R, Huerta A, Martinez R, Montull B, Clini E, Torres A. Systemic inflammatory pattern of patients with community-acquired pneumonia with and without COPD. Chest. 2013;143(4):1009–17. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cuomo G, Brancaccio G, Stornaiuolo G, Manno D, Gaeta GL, Mussini C, Puoti M, Gaeta GB. Bacterial pneumonia in patients with liver cirrhosis, with or without HIV co-infection: a possible definition of antibiotic prophylaxis associated pneumonia (APAP). Infect Dis. 2018;50(2):125–32. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2017.1367414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Curran A, Falcó V, Crespo M, Martinez X, Ribera E, Villar del Saz S, Imaz A, Coma E, Ferrer A, Pahissa A, et al. Bacterial pneumonia in HIV-infected patients: use of the pneumonia severity index and impact of current management on incidence, aetiology and outcome. HIV Med. 2008;9(8):609–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dambrava PG, Torres A, Valles X, Mensa J, Marcos MA, Penarroja G, Camps M, Estruch R, Sanchez M, Menendez R, et al. Adherence to guidelines‘ empirical antibiotic recommendations and community-acquired pneumonia outcome. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):892–901. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00163407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dancona F, Salmaso S, Barale A, Boccia D, Lopalco PL, Rizzo C, Monaco M, Massari M, Demicheli V, Pantosti A, et al. Incidence of vaccine preventable pneumococcal invasive infections and blood culture practices in Italy. Vaccine. 2005;23(19):2494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dancona F, Caporali MG, Manso MD, Giambi C, Camilli R, D’Ambrosio F, Del Grosso M, Iannazzo S, Rizzuto E, Pantosti A. Invasive pneumococcal disease in children and adults in seven Italian regions after the introduction of the conjugate vaccine, 2008–2014. Epidemiol Prev. 2015;5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.de Egea V, Muñoz P, Valerio M, de Alarcón A, Lepe JA, Miró JM, Gálvez-Acebal J, García-Pavía P, Navas E, Goenaga MA, et al. Characteristics and outcome of Streptococcus pneumoniae endocarditis in the XXI century: a systematic review of 111 cases (2000–2013). Medicine. 2015;94(39):e1562. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.de Oliveira MJMN. Vigilância de infecções associadas aos cuidados de saúde e importância do consumo de anti-microbianos em cuidados intensivos. Lisboa (Portugal): University of Lisboa; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 92.de Roux A. Mixed community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalised patients. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(4):795–800. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00058605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.de Roux A, Cavalcanti M, Marcos MA, Garcia E, Ewig S, Mensa J, Torres A. Impact of alcohol abuse in the etiology and severity of community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2006;129(5):1219–25. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.de Sousa Carlos IS. Demora média no tratamento da pneumonia adquirida na comunidade. Estudo sobre os hospitais públicos portugueses entre 2009 e 2011. Lisboa (Portugal): Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Díaz-Ravetllat V, Ferrer M, Gimferrer-Garolera JM, Molins L, Torres A. Risk factors of postoperative nosocomial pneumonia after resection of bronchogenic carcinoma. Respir Med. 2012;106(10):1463–71. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dimakou K, Triantafillidou C, Toumbis M, Tsikritsaki K, Malagari K, Bakakos P. Non CF-bronchiectasis: aetiologic approach, clinical, radiological, microbiological and functional profile in 277 patients. Respir Med. 2016;116:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Domingo P, Suarez-Lozano I, Torres F, Pomar V, Ribera E, Galindo MJ, Cosin J, Garcia-Alcalde ML, Vidal F, Lopez-Aldeguer J, et al. Bacterial meningitis in HIV-1-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(5):582–87. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181adcb01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Domingo P, Pomar V, de Benito N, Coll P. The spectrum of acute bacterial meningitis in elderly patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Domingo P, Pomar V, Benito N, Coll P. The changing pattern of bacterial meningitis in adult patients at a large tertiary university hospital in Barcelona, Spain (1982–2010). J Infect. 2013;66(2):147–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dominguez A. The epidemiology of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae disease in Catalonia (Spain). A hospital-based study. Vaccine 2002;20(23–24):2989–94. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Esperatti M, Ferrer M, Theessen A, Liapikou A, Valencia M, Saucedo LM, Zavala E, Welte T, Torres A. Nosocomial pneumonia in the intensive care unit acquired by mechanically ventilated versus nonventilated patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(12):1533–39. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0094OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cabezón Estévanez I. Uso de la procalcitonina como marcador pronóstico en la neumonía adquirida en la comunidad. Madrid: Complutense University of Madrid (Spain); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ewig S, Torres A, El-Ebiary M, Fàbregas N, Hernández C, González J, Nicolás J, Soto L. Bacterial colonization patterns in mechanically ventilated patients with traumatic and medical head injury: incidence, risk factors, and association with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):188–98. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9803097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Falcón Vega MS. Epidemiología y sensibilidad antibiótica de Streptococcus pneumoniae en muestras invasivas en el HCU “Lozano Blesa” de Zaragoza (2013–2016). Zaragoza (Spain): University of Zaragoza; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Falcone M, Russo A, Giannella M, Cangemi R, Scarpellini MG, Bertazzoni G, Alarcón JM, Taliani G, Palange P, Farcomeni A, et al. Individualizing risk of multidrug-resistant pathogens in community-onset pneumonia. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0119528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Falcone M, Tiseo G, Russo A, Giordo L, Manzini E, Bertazzoni G, Palange P, Taliani G, Cangemi R, Farcomeni A, et al. Hospitalization for pneumonia is associated with decreased 1-year survival in patients with type 2 diabetes: results from a prospective cohort study. Medicine. 2016;95(5):e2531. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Falguera M, Sacristán O, Nogués A, Ruiz-González A, García M, Manonelles A, Rubio-Caballero M. Nonsevere community-acquired pneumonia: correlation between cause and severity or comorbidity. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(15):1866. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Falguera M, Ruiz-Gonzalez A, Schoenenberger JA, Touzon C, Gazquez I, Galindo C, Porcel JM. Prospective, randomised study to compare empirical treatment versus targeted treatment on the basis of the urine antigen results in hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2010;65(2):101–06. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.118588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Faustini A, Fabrizi E, Sangalli M, Bordi E, Cipriani P, Fiscarelli E, Perucci C. Role of laboratories in population-based surveillance of invasive diseases in Lazio, Italy, 1998–2000. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;21(11):824–26. doi: 10.1007/s10096-002-0830-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fenoll A, Granizo JJ, Aguilar L, Gimenez MJ, Aragoneses-Fenoll L, Hanquet G, Casal J, Tarrago D. Temporal trends of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes and antimicrobial resistance patterns in Spain from 1979 to 2007. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(4):1012–20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01454-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fernández-Sabé N, Carratalà J, Rosón B, Dorca J, Verdaguer R, Manresa F, Gudiol F. Community-acquired pneumonia in very elderly patients: causative organisms, clinical characteristics, and outcomes. Medicine. 2003;82(3):159–69. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000076005.64510.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fernández-Serrano S, Dorca J, Garcia-Vidal C, Fernández-Sabé N, Carratalà J, Fernández-Agüera A, Corominas M, Padrones S, Gudiol F, Manresa F, et al. Effect of corticosteroids on the clinical course of community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Critical Care. 2011;15(2):R96. doi: 10.1186/cc10103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fernández-Serrano S, Dorca J, Coromines M, Carratalà J, Gudiol F, Manresa F. Molecular inflammatory responses measured in blood of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10(5):813–20. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.5.813-820.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Fernández Guerrero ML, Ramos JM, Marrero J, Cuenca M, Fernández Roblas R, Górgolas MD. Bacteremic pneumococcal infections in immunocompromised patients without AIDS: the impact of β-lactam resistance on mortality. Int J Infect Dis. 2003;7(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/S1201-9712(03)90042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ferré C, Llopis Roca F, Jacob J, Juan i Pastor A, Palom X, Bardés I, Salazar Soler A. Evaluación de la uitilidad de la tinción de Gram del esputo para el manejo de la neumonía en urgencias. Emergencias. 2011;23:108–11. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nogueira Ferreira LM. Características das infecções respiratórias em idosos internados. Coimbra (Portugal): University of Coimbra; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ferrer M, Travierso C, Cilloniz C, Gabarrus A, Ranzani OT, Polverino E, Liapikou A, Blasi F, Torres A. Severe community-acquired pneumonia: characteristics and prognostic factors in ventilated and non-ventilated patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0191721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ferrer M, Sequeira T, Cilloniz C, Dominedo C, Bassi GL, Martin-Loeches I. Ventilator-associated pneumonia and PAO2/FIO2 diagnostic accuracy: changing the paradigm? J Clin Med. 2019;8(8):1217. doi: 10.3390/jcm8081217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Fiasca F, Necozione S, Mattei A. Analisi epidemiologica delle ospedalizzazioni per meningite batterica in Italia (anni 2006–2015). Società Italiana di Igiene e medicina preventiva; 2017. [accessed 2020 Aug 27]. https://ricerca.univaq.it/handle/11697/121676#.Xsai6BNKg1I.

- 120.Franco Moreno AI, Casallo Blanco S, Marcos Sánchez F, Sánchez Casado M, Gil Ruiz MT, Martínez de la Casa Muñoz AM. Martínez de la Casa Muñoz AM. Estudio de las bacteriemias en el Servicio de Medicina Interna de un hospital de grupo 2: análisis de los tres últimos años. An Med Interna. 2005;22(5):217–21. doi: 10.4321/s0212-71992005000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Franzetti F, Grassini A, Piazza M, Degl’Innocenti M, Bandera A, Gazzola L, Marchetti G, Gori A. Nosocomial bacterial pneumonia in HIV-infected patients: risk factors for adverse outcome and implications for rational empiric antibiotic therapy. Infection. 2006;34(1):9–16. doi: 10.1007/s15010-006-5007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Fuentes-Antrás J, Ramírez-Torres M, Osorio-Martínez E, Lorente M, Lorenzo-Almorós A, Lorenzo O, Górgolas M. Acute community-acquired bacterial meningitis: update on clinical presentation and prognostic factors. New Microbiol. 2019;41:81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gagliotti C, Morsillo F, Moro ML, Masiero L, Procaccio F, Vespasiano F, Pantosti A, Monaco M, Errico G, Ricci A, et al. Infections in liver and lung transplant recipients: a national prospective cohort. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37(3):399–407. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Garau J, Baquero F, Pérez-Trallero E, Pérez JL, Martín-Sánchez AM, García-Rey C, Martín-Herrero JE, Dal-Ré R. Factors impacting on length of stay and mortality of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(4):322–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.García López FA. Neumonía asociada a ventilación mecánica: papel de la aspiración de las secreciones subglóticas en su prevención e identificación de factores de riesgo. Madrid (Spain): Autonomous University of Madrid; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 126.García Ordóñez MA, Moya Benedicto R, López González JJ, Colmenero Castillo JD. Bacteriemia neumocócica en el adulto en un hospital de tercer nivel. An Med Interna. 2003;20:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.García Vidal C. Optimización del manejo de la neumonía adquirida en la comunidad. Barcelona (Spain): University of Barcelona; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Garcia-Vidal C, Calbo E, Pascual V, Ferrer C, Quintana S, Garau J. Effects of systemic steroids in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(5):951–56. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00027607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Garcia-Vidal C, Carratalà J, Fernández-Sabé N, Dorca J, Verdaguer R, Manresa F, Gudiol F. Aetiology of, and risk factors for, recurrent community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(11):1033–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Garcia-Vidal C, Ardanuy C, Gudiol C, Cuervo G, Calatayud L, Bodro M, Duarte R, Fernández-Sevilla A, Antonio M, Liñares J, et al. Clinical and microbiological epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia in cancer patients. J Infect. 2012;65(6):521–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gattarello S, Lagunes L, Vidaur L, Solé-Violán J, Zaragoza R, Vallés J, Torres A, Sierra R, Sebastian R, Rello J, et al. Improvement of antibiotic therapy and ICU survival in severe non-pneumococcal community-acquired pneumonia: a matched case–control study. Critical Care. 2015;19(1):335. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1051-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Giannella M. Estudio de neumonía en Medicina Interna en españa. Madrid (Spain): Complutense University of Madrid; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Giannella M, Pinilla B, Capdevila JA, Alarcón JM, Muñoz P, Álvarez JL, Bouza E. Pneumonia treated in the internal medicine department: focus on healthcare-associated pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(8):786–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gil-Prieto R, García-García L, Álvaro-Meca A, Méndez C, García A, Gil de Miguel Á. The burden of hospitalisations for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and pneumococcal pneumonia in adults in Spain (2003–2007). Vaccine. 2011;29(3):412–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ginesu F, Pirina P, Deiola G, Ostera S, Mele S, Fois AG. Etiology and therapy of community-acquired pneumonia. J Chemother. 1997;9(4):285–92. doi: 10.1179/joc.1997.9.4.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Gómez J, Baños V, Gómez JR, Herrero F, Núñez ML, Canteras M, Valdés M. Clinical significance of pneumococcal bacteraemias in a general hospital: a prospective study 1989–1993. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36(6):1021–30. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.6.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Gómez J, Baños V, Gómez JR, Soto MC, Muñoz L, Nuñez ML, Canteras M, Valdés M. Prospective study of epidemiology and prognostic factors in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15(7):556–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01709363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gómez CG. Estudio descriptivo y análisis de los factores pronósticos de las bacteriemias en el Hospital José María Morales Meseguer (Murcia). Murcia (Spain): University of Murcia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Gómez-Junyent J, Garcia-Vidal C, Viasus D, Millat-Martínez P, Simonetti A, Santos MS, Ardanuy C, Dorca J, Carratalà J. Clinical features, etiology and outcomes of community-acquired pneumonia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.González-Díaz A, Càmara J, Ercibengoa M, Cercenado E, Larrosa N, Quesada MD, Fontanals D, Cubero M, Marimón JM, Yuste J, et al. Emerging non-13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) serotypes causing adult invasive pneumococcal disease in the late-PCV13 period in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(6):753–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.González-Echavarri C, Capdevila O, Espinosa G, Suárez S, Marín-Ballvé A, González-León R, Rodríguez-Carballeira M, Fonseca-Aizpuru E, Pinilla B, Pallarés L, et al. Infections in newly diagnosed Spanish patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: data from the RELES cohort. Lupus. 2018;27(14):2253–61. doi: 10.1177/0961203318811598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gordo-Remartínez S, Calderón-Moreno M, Fernández-Herranz J, Castuera-Gil A, Gallego-Alonso-Colmenares M, Puertas-López C, Nuevo-González JA, Sánchez-Sendín D, García-Gámiz M, Sevillano-Fernández JA, et al. Usefulness of midregional proadrenomedullin to predict poor outcome in patients with community acquired pneumonia. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0125212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Grau I, Ardanuy C, Liñares J, Podzamczer D, Schulze M, Pallares R. Trends in mortality and antibiotic resistance among HIV-infected patients with invasive pneumococcal disease. HIV Med. 2009;10(8):488–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Grau I, Ardanuy C, Calatayud L, Rolo D, Domenech A, Liñares J, Pallares R. Invasive pneumococcal disease in healthy adults: increase of empyema associated with the clonal-type Sweden1-ST306. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Guevara M, Barricarte A, Gil-Setas A, García-Irure JJ, Beristain X, Torroba L, Petit A, Polo Vigas ME, Aguinaga A, Castilla J, et al. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease following increased coverage with the heptavalent conjugate vaccine in Navarre, Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(11):1013–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Guevara M, Ezpeleta C, Gil-Setas A, Torroba L, Beristain X, Aguinaga A, García-Irure JJ, Navascués A, García-Cenoz M, Castilla J, et al. Reduced incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease after introduction of the 13-valent conjugate vaccine in Navarre, Spain, 2001–2013. Vaccine. 2014;32(22):2553–62. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Guglielmo L, Leone R. Aetiology and therapy of community-acquired pneumonia: a hospital study in northern Italy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;51(6):437–43. doi: 10.1007/s002280050227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Gutiérrez F, Masiá M, Rodríguez JC, Mirete C, Soldán B, Padilla S, Hernández I, Ory FD, Royo G, Hidalgo AM, et al. Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia in adult patients at the dawn of the 21st century: a prospective study on the Mediterranean coast of Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11(10):788–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Gutiérrez F, Masiá M, Mirete C, Soldán B, Carlos Rodríguez J, Padilla S, Hernández I, Royo G, Martin-Hidalgo A. The influence of age and gender on the population-based incidence of community-acquired pneumonia caused by different microbial pathogens. J Infect. 2006;53(3):166–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Gutiérrez Rodríguez MÁ, Ordobás Gavín M, Ramírez Fernández R, García Comas L, García Fernández C, Rodero Garduño I. Incidencia de enfermedad neumocócica en la Comunidad de Madrid en el período 1998–2006. Med Clin (Barc). 2008;130(2):51–53. doi: 10.1157/13115027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Guzmán Avalos JA. Epidemiología de la infección neumocócica en la población de Tarragona 2002–2009 incidencia, factores de riesgo asociados, distribución de serotipos e impacto de la vacunación. Barcelona (Spain): Autonomous University of Barcelona; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hanquet G, Krizova P, Valentiner-Branth P, Ladhani SN, Nuorti JP, Lepoutre A, Mereckiene J, Knol M, Winje BA, Ciruela P, et al. Effect of childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive disease in older adults of 10 European countries: implications for adult vaccination. Thorax. 2019;74(5):473–82. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Herrera Lara S. Estacionalidad de la neumonía adquirida en la comunidad (NAC) y su influencia con el clima. Barcelona (Spain): Autonomous University of Barcelona; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 154.Herrera-Lara S, Fernández-Fabrellas E, Cervera-Juan Á, Blanquer-Olivas R. ¿Influyen la estación y el clima en la etiología de la neumonía adquirida en la comunidad? Arch Bronconeumol. 2013;49(4):140–45. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]