Abstract

Despite increasing interest in how voice assistants like Siri or Alexa might improve health care delivery and information dissemination, there is limited research assessing the quality of health information provided by these technologies. Voice assistants present both opportunities and risks when facilitating searches for or answering health-related questions, especially now as fewer patients are seeing their physicians for preventive care due to the ongoing pandemic. In our study, we compared the 4 most widely used voice assistants (Amazon Alexa, Apple Siri, Google Assistant, and Microsoft Cortana) and their ability to understand and respond accurately to questions about cancer screening. We show that there are clear differences among the 4 voice assistants and that there is room for improvement across all assistants, particularly in their ability to provide accurate information verbally. In order to ensure that voice assistants provide accurate information about cancer screening and support, rather than undermine efforts to improve preventive care delivery and population health, we suggest that technology providers prioritize partnership with health professionals and organizations.

Key words: preventive medicine, early detection of cancer, artificial intelligence

INTRODUCTION

Voice assistants, powered by artificial intelligence, interact with users in natural language and can answer questions, facilitate web searches, and respond to basic commands. The use of this technology has been growing; in 2017, nearly one-half of US adults reported using an assistant, most commonly through their smartphones.1 Many individuals search for health information online; when assistants facilitate searches for and answer health-related questions, they present both opportunities and risks.

Because fewer patients are seeing their physicians for preventive care due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,2 it is important to better understand the health information patients access digitally. This study aims to compare how 4 widely used voice assistants (Amazon Alexa, Apple Siri, Google Assistant, and Microsoft Cortana) respond to questions about cancer screening.

METHODS

The study was conducted in the San Francisco Bay Area in May 2020 using the personal smartphones of 5 investigators. Of the 5 investigators (2 men, 3 women), 4 were native English speakers. Each voice assistant received 2 independent reviews; the primary outcome was their response to the query “Should I get screened for [type of] cancer?” for 11 cancer types. From these responses, we assessed the assistants’ ability to (1) understand queries, (2) provide accurate information through web searches, and (3) provide accurate information verbally.

When evaluating accuracy, we compared responses to the US Preventive Services Task Force’s (USPSTF) cancer screening guidelines (Table 1). A response was deemed accurate if it did not directly contradict this information and if it provided a starting age for screening consistent with these guidelines (Supplemental Appendix 1, available at https://www.AnnFamMed.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1370/afm.2713/-/DC1).

Table 1.

Current USPSTF Screening Guidelines for the 11 Cancer Types Queried

| Cancer Type | Screening Guideline |

|---|---|

| Bladder | The USPSTF concludes the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for bladder cancer in asymptomatic adults. |

| Breast | The USPSTF recommends biennial screening mammography for women aged 50 to 74 years. |

| Cervical | The USPSTF recommends screening for cervical cancer every 3 years with cervical cytology alone in women aged 21 to 29 years. For women aged 30 to 65 years, the USPSTF recommends screening every 3 years with cervical cytology alone, every 5 years with high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) testing alone, or every 5 years with hrHPV testing in combination with cytology (cotesting). |

| Colorectal | The USPSTF recommends screening for colorectal cancer starting at age 50 years and continuing until age 75 years. |

| Lung | The USPSTF recommends annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) in adults aged 55 to 80 years who have a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years. Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years or develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy or the ability or willingness to have curative lung surgery. |

| Ovarian | The USPSTF recommends against screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women. |

| Pancreatic | The USPSTF recommends against screening for pancreatic cancer in asymptomatic adults. |

| Prostate | For men aged 55 to 69 years, the decision to undergo periodic prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based screening for prostate cancer should be an individual one. Before deciding whether to be screened, men should have an opportunity to discuss the potential benefits and harms of screening with their clinician and to incorporate their values and preferences in the decision. |

| Skin | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of visual skin examination by a clinician to screen for skin cancer in adults. |

| Testicular | The USPSTF recommends against screening for testicular cancer in adolescent or adult men. |

| Thyroid | The USPSTF recommends against screening for thyroid cancer in asymptomatic adults. |

USPSTF = US Preventive Services Task Force.

If the assistant responded with a web search, verbally, or both, we noted that it was able to understand the query. To evaluate web searches, we visited the top 3 web pages displayed as research shows these results get 75% of all clicks.3 Then, we read through each web page and noted if the information is consistent with USPSTF guidelines. Similarly, for verbal responses, we transcribed each response and noted whether it provided accurate information.

RESULTS

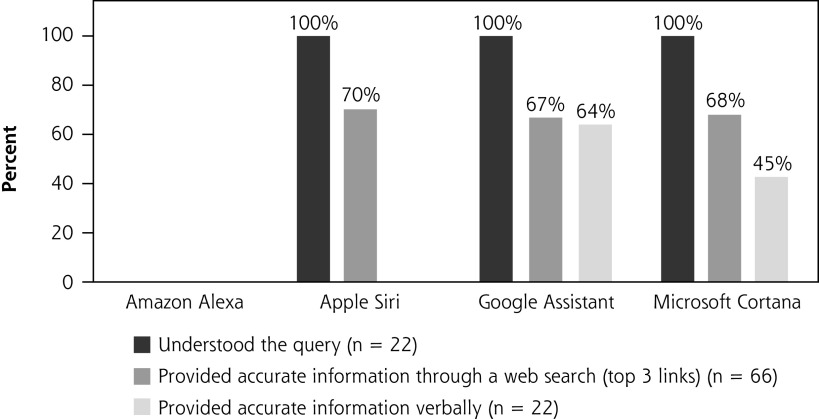

Figure 1 compares the voice assistants’ ability to understand and respond accurately to questions about cancer screening. Siri, Google Assistant, and Cortana understood 100% of the queries, consistently generating a web search and/or a verbal response. On the other hand, Alexa consistently responded, “Hm, I don’t know that” and was unable to understand or respond to any of the queries. Regarding the accuracy of web searches, we found that Siri, Google Assistant, and Cortana performed similarly, and the top 3 links they displayed provided information consistent with USPSTF guidelines roughly 7 in 10 times. The web searches we assessed came from a total of 34 different sources, with 47% of responses referencing the American Cancer Society or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For-profit websites, including WebMD and Healthline, were referenced 14% of the time (Supplemental Appendix 2, available at https://www.AnnFamMed.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1370/afm.2713/-/DC1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of voice assistants’ ability to understand and respond accurately to questions about cancer screening.

Verbal response accuracy varied more among the assistants. Google Assistant matched USPSTF guidelines 64% of the time, maintaining an accuracy rate similar to its web searches. Cortana’s accuracy of 45% was lower than its web searches and Siri was not able to provide a verbal response to any of the queries.

Cohen’s κ was used to measure the level of agreement between the 2 investigators that assessed each assistant’s responses. For Siri, Google Assistant, and Cortana respectively, the κ values were 0.956 (95% CI, 0.872-1.000), 0.785 (95% CI, 0.558-1.000), and 0.893 (95% CI, 0.749-1.000).

DISCUSSION

In terms of responding to questions about cancer screening, there are clear differences among the 4 most popular voice assistants, and there is room for improvement across all assistants. Almost unanimously, their verbal responses to queries were either unavailable or less accurate than their web searches. This could have implications for users who are sight-impaired, less techsavvy, or have low health literacy as it requires them to navigate various web pages and parse through potentially conflicting health information.

Our study has several limitations. We used standardized questions, whereas patients using their personal smartphones may word their questions differently, influencing the responses they receive. Furthermore, because the investigators work in the medical field and have likely used their devices to search for medical evidence before this study, they may have received higher quality search results for health-related questions than the average user.

Our findings are consistent with existing literature assessing the quality of assistants’ answers to health-related questions. Miner et al found that assistants responded inconsistently and incompletely to questions about mental health and interpersonal violence.4 Alagha and Helbing found that Google Assistant and Siri understood queries about vaccine safety more accurately and drew information from expert sources more often than Alexa.5

Sezgin et al acknowledge that assistants have the potential to support health care delivery and information dissemination, both during and after COVID-19, but state that this vision requires partnership between technology providers and public health authorities.6 Our findings support this assessment and suggest that software developers might consider partnering with health professionals—in particular guideline developers and evidence-based medicine practitioners—to ensure that assistants provide accurate information about cancer screening given the potential impact on individuals and population health.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, go to https://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/19/5/447/tab-e-letters.

Previous presentations: Society of Teachers of Family Medicine’s 53rd Annual Conference; August 2020; Salt Lake City, Utah

Supplemental materials: Available at https://www.AnnFamMed.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1370/afm.2713/-/DC1.

References

- 1.Pew Research Center . Nearly half of Americans use digital voice assistants, mostly on their smartphones. Published December12, 2017. Accessed Sep 23, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/12/12/nearly-half-of-americans-use-digital-voice-assistants-mostly-on-their-smartphones/

- 2.Prevent Cancer Foundation . Leading nonprofit works with nation’s cancer experts on importance of screening. Published August6, 2020. Accessed Sep 23, 2020. https://www.preventcancer.org/2020/08/prevent-cancer-foundation-announces-back-on-the-books-a-lifesaving-initiative-in-the-face-of-covid-19/

- 3.Dean B. Here’s what we learned about organic click through rate. Backlinko. Published August27, 2019. Accessed Sep 23, 2020. https://backlinko.com/google-ctr-stats

- 4.Miner AS, Milstein A, Schueller S, Hegde R, Mangurian C, Linos E. Smartphone-based conversational agents and responses to questions about mental health, interpersonal violence, and physical health. JAMA Intern Med. 2016; 176(5): 619-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alagha EC, Helbing RR. Evaluating the quality of voice assistants’ responses to consumer health questions about vaccines: an exploratory comparison of Alexa, Google Assistant and Siri. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2019; 26(1): e100075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sezgin E, Huang Y, Ramtekkar U, Lin S. Readiness for voice assistants to support healthcare delivery during a health crisis and pandemic. NPJ Digit Med. 2020; 3(122): 1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.