Abstract

Objectives

The Australian COVID-19 Frontline Healthcare Workers Study investigated coping strategies and help-seeking behaviours, and their relationship to mental health symptoms experienced by Australian healthcare workers (HCWs) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Australian HCWs were invited to participate a nationwide, voluntary, anonymous, single time-point, online survey between 27th August and 23rd October 2020. Complete responses on demographics, home and work situation, and measures of health and psychological wellbeing were received from 7846 participants.

Results

The most commonly reported adaptive coping strategies were maintaining exercise (44.9%) and social connections (31.7%). Over a quarter of HCWs (26.3%) reported increased alcohol use which was associated with a history of poor mental health and worse personal relationships. Few used psychological wellbeing apps or sought professional help; those who did were more likely to be suffering from moderate to severe symptoms of mental illness. People living in Victoria, in regional areas, and those with children at home were significantly less likely to report adaptive coping strategies.

Conclusions

Personal, social, and workplace predictors of coping strategies and help-seeking behaviour during the pandemic were identified. Use of maladaptive coping strategies and low rates of professional help-seeking indicate an urgent need to understand the effectiveness of, and the barriers and enablers of accessing, different coping strategies.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed unprecedented challenges on healthcare systems globally, with significant impacts on the mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. While it has been demonstrated that HCWs have higher resilience scores than the general population [5], they face unique workplace demands and are at increased risk of depression, burnout and suicide during daily life outside of crises [6,7]. During the pandemic, frontline HCWs have reported even higher levels of anxiety, depression and PTSD [8]. How frontline HCWs manage and respond to these psychosocial harms during the unique circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic is poorly understood. Yet, knowledge regarding the types of coping strategies that HCWs utilise and find effective is crucial for informing policies and processes, and implementing evidence-based practices to mitigate psychosocial hazards during crises.

Coping strategies can be broadly classified as adaptive, such as seeking social support, or maladaptive such as excessive alcohol use; with types of coping strategies used being an important modifier for mental health outcomes in HCWs [[9], [10], [11], [12]]. It is well recognised that both mental illness and the treatments available for these conditions are associated with stigma, which forms an important barrier to HCWs seeking formal help or engaging with professional support services, despite high burdens of mental health issues [18,19].

A handful of studies have examined the types of coping strategies that HCWs utilise when facing stressful working conditions, natural disasters and other infectious disease outbreaks [[13], [14], [15]]. Additionally, there is some evidence regarding the coping strategies adopted by the general public during the current COVID-19 pandemic [16,17]. However, to date, no large-scale studies have investigated the coping strategies utilised by frontline HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic, or explored the personal and workplace predictors that are associated with coping strategies utilised. Knowledge regarding the patterns and predictors of coping and help-seeking behaviours (particularly understanding if certain HCW groups are more or less likely to engage with specific psychological wellbeing support programs) is critical to informing and developing targeted interventions to safeguard frontline workforces during current and future crises.

This paper reports a subset of findings from the Australian COVID-19 Frontline Healthcare Workers Study, an initiative led by frontline clinicians in partnership with academics to investigate the severity and prevalence of mental health issues, as well as the social, workplace and financial disruptions experienced by Australian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic [8]. This paper builds on our previously reported findings regarding the prevalence and predictors of mental illness among Australian frontline HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic [8], and aims to identify the types of coping strategies and help-seeking behaviours utilised, the predictors associated with these behaviours, and the relationship between coping strategies utilised, help seeking and mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesised that Australian frontline HCWs would report limited engagement with both adaptive coping strategies and help-seeking behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and sample

A nationwide, voluntary, online survey was conducted between 27th August and 23rd October 2020, concurrent with the second wave of the pandemic in Australia. At the time of survey closure, caseload was low relative to international settings, with 27,484 cases recorded, the majority of which were in Melbourne, Victoria [20]. Severe lockdown restrictions had been instituted locally, including (but not limited to): mandatory mask wearing, travel limited to 5 km from home, an evening curfew, one-hour limit for outdoor exercise per day, limits on seeing extended family, working from home, home schooling, the closure of most shops, hospitality and entertainment venues, and closure of international and interstate borders.

Healthcare workers from all professions and backgrounds, who self-identified as frontline healthcare workers in primary or secondary care, were invited to participate. Participants did not need to have cared for people with COVID-19 to take part. Participants were recruited through multiple strategies. Information regarding the survey was emailed to CEOs and departmental directors of frontline areas of all public hospitals throughout Victoria, and to multiple hospitals around Australia. Hospital leaders were asked to share the survey information with colleagues. Thirty-six professional societies, colleges, universities, associations and government health department staff also disseminated information about the survey across Australia. Additionally, the study was promoted through 117 newspapers, 8 television and radio news items and 30 social media sites.

2.2. Data collection

Each participant completed the survey only once, either directly via the online survey link or the study website (https://covid-19-frontline.com.au/). Data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools [21]. The survey questionnaire collected data regarding demographics, home life, professional background, work arrangements and finances, strategies for staying healthy, and mental health symptoms (Supplement 1). Further detail regarding the questionnaire design has been published elsewhere [8]. Thirteen multiple choice format and free text questions regarding self-reported illnesses and strategies to manage mental and physical health issues experienced during the pandemic were included in the section on relaxing and staying healthy. Participants provided online consent to participate in the study. The Royal Melbourne Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (HREC/67074/MH-2020).

2.3. Statistical methods and data analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software version 26.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Data are reported descriptively with counts, frequencies and summary statistics. Predictors of coping strategies and help-seeking behaviour were identified through univariable logistic regression then entered into a multivariable logistic regression model. Multivariable models were developed using stepwise selection and backward elimination procedures before undergoing a final assessment for clinical and biological plausibility. Variables with a p value of less than 0.10 on univariable analyses or those deemed to be clinically significant were considered for inclusion in the multivariable model. Results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). p < 0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance. Covariates examined in the regression analyses included: age; sex; Australian state of residence; occupation; others living at home; children living at home; practice location; improved relationship with partner, family, friends, or colleagues; worse relationship with partner, family, friends, or colleagues; frontline area; experiencing close friends or relatives infected with COVID-19; concerns regarding household income and having a pre-existing mental health condition. To examine relationships between coping strategies or behaviours and mental health, the outcomes of each mental health scale were merged into dichotomous categories (no or minimal symptoms versus moderate to severe symptoms). A chi-square test of independence was performed to test association between mental health outcomes and coping strategies or help-seeking predictors.

3. Results

3.1. Participants' characteristics, health & coping strategies

Survey responses were received from 9518 participants, with complete data from 7846 (82.4%) participants reported in this article. Most (4110, 52.4%) participants were younger than 40 years and 6344 (80.9%) were women (Table 1 ). Over one quarter (2250, 28.7%) had caring responsibilities at home and 2133 (27.2%) had children home schooling.

Table 1.

Participants' characteristics.

| Characteristic | Frequency (n = 7846) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–30 | 1860 | 23.7 |

| 31–40 | 2250 | 28.7 |

| 41–50 | 1738 | 22.2 |

| >50 | 1998 | 25.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1458 | 18.6 |

| Female | 6344 | 80.9 |

| Non-binary | 19 | 0.2 |

| Prefer not to say | 25 | 0.3 |

| State | ||

| Victoria | 6685 | 85.2 |

| All other Australian states | 1161 | 14.8 |

| Occupation | ||

| Nursing | 3088 | 39.4 |

| Medical ⁎ | 2436 | 31.1 |

| Allied Health | 1314 | 16.7 |

| Administrative Staff | 485 | 6.2 |

| Other roles ⁎⁎ | 523 | 6.7 |

| Number of people in the household | ||

| Lives alone (1 person) | 1087 | 13.9 |

| Lives with 1 or more others | 6759 | 86.1 |

| Number of children < 16 years at home | ||

| 1–2 | 2253 | 28.7 |

| 3+ | 491 | 6.2 |

| Lives with ≥ 1 elderly person/people at home | 697 | 8.9 |

| Current physical health (self-reported) | ||

| Excellent | 1975 | 25.2 |

| Good | 4456 | 56.8 |

| Fair | 1260 | 16.1 |

| Poor | 155 | 2.0 |

| Underlying health conditions that increase their risk of becoming unwell with COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 2132 | 27.2 |

| No | 5714 | 72.8 |

Medical staff comprised 389 general practitioners, 1221 senior medical staff, 745 junior medical staff and 81 students.

Other = Pharmacists: 185, clinical laboratory scientists or technicians: 176, paramedics: 95, support staff (including cleanings, security, facilities management personnel): 43, leadership role: 9 and other role: 15.

One third of respondents (2389, 30.4%) reported having a pre-existing diagnosed mental illness. Many participants self-reported experiencing symptoms of anxiety (4875, 62.1%), burnout (4575, 58.3%), or depression (2175, 27.7%) since the onset of the pandemic. Mental health symptoms, measured using validated scales, were identified in significant numbers of participants, including moderate to severe symptoms of: anxiety (2216, 28.3%), depression (2192, 28.0%), depersonalisation (2877, 37.4%), and emotional exhaustion (5458, 70.9%). Depersonalisation and emotional exhaustion are both subdomains of burnout [22]. A third of respondents reported a low sense of personal accomplishment, the third subdomain of burnout (2243, 29.1%). Although only 5.4% (427) of participants self-reported PTSD, nearly half (3155, 40.5%) scored moderate to severe for symptoms of PTSD in the validated IES-6 instrument. The personal and workplace predictors for experiencing adverse mental health outcomes in this HCW study have been published [8].

In indicating strategies for ‘relaxing and staying healthy’ (Part E of the survey) respondents indicated a range of positive and negative strategies to support mental health during the pandemic (Table 2 ). The most common strategy adopted since the onset of the pandemic was physical exercise, which was maintained (3524, 44.9%) or increased (1994, 25.4%) by most participants. A minority (1112, 14.2%) used psychological wellbeing applications (Apps) on their smartphone or tablet. Among those who did, most found them helpful (969, 87.1%) and used them long-term (790, 71.0%). A quarter of participants (2066, 26.3%) reported increasing their alcohol intake, which was classified as a negative coping strategy in this study.

Table 2.

Coping strategies & health seeking behaviours.

| Characteristic | Frequency (n = 7846) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Activities to manage possible mental health issues since the pandemic started | ||

| Maintained exercise | 3524 | 44.9 |

| Increased exercise | 1994 | 25.4 |

| Yoga, meditation or similar | 1999 | 25.5 |

| Maintained or increased social interaction with family and friends | 2484 | 31.7 |

| Used a psychological wellbeing App (e.g. Smiling Mind, Headspace or other) | 1112 | 14.2 |

| Increased alcohol use | 2066 | 26.3 |

| None of the above | 939 | 12.0 |

| Was the App used to support psychological wellbeing useful | ||

| Yes | 969 | 12.4 |

| No | 95 | 1.2 |

| Are you still using the App to support psychological wellbeing | ||

| Yes | 790 | 10.1 |

| No | 272 | 3.5 |

| Sought help for stress or mental health issues from other sources | ||

| Doctor or psychologist | 1436 | 18.3 |

| Employee support program at place of work | 474 | 6.0 |

| Professional support program outside of work | 246 | 3.1 |

| None of the above | 5793 | 73.8 |

3.2. Predictors of coping strategies and help-seeking behaviour

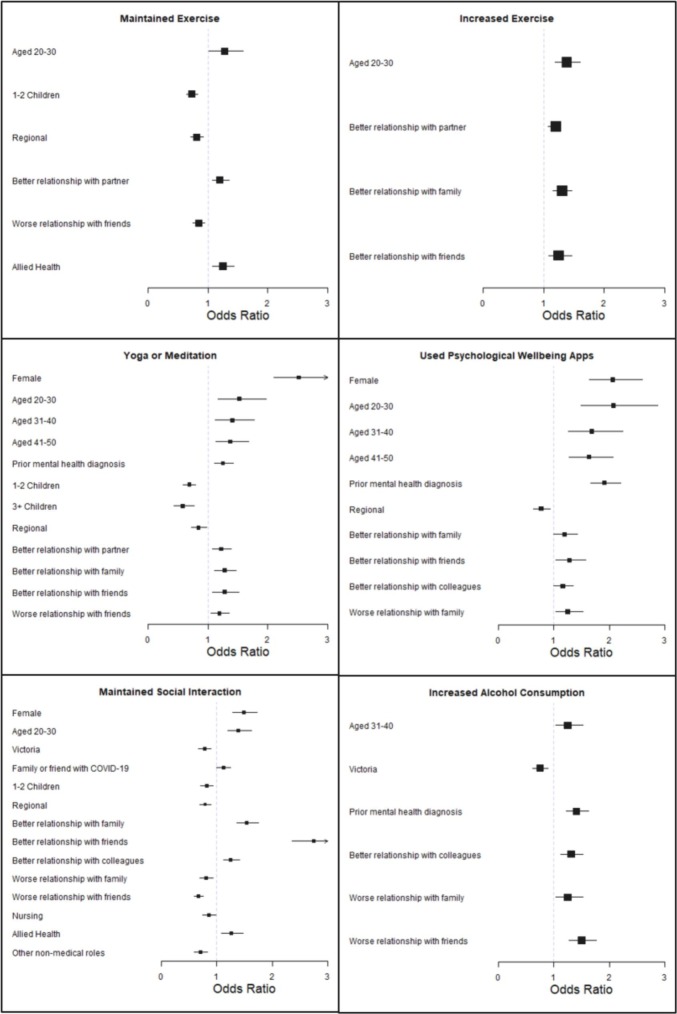

In the multivariable model, independent, significant predictors of adopting positive coping strategies included: being female, younger age, having a prior mental health condition, experiencing positive relationship changes, and working in an allied health compared to medical role (Fig. 1 ; Supplementary Table 1). People living in Victoria, with children at home, or working in regional areas were significantly less likely to adopt positive coping strategies. Increased alcohol use to cope with mental health issues during the pandemic was significantly associated with being aged 31–40 years (compared to age over 50 years), having a prior mental health diagnosis, worse relationships with family or friends, and better relationships with colleagues. Other characteristics (including but not limited to: frontline area, currently working with COVID-19 patients, elderly people living at home, concerns regarding household income and income changes) were not associated with particular coping strategies.

Fig. 1.

Personal and professional predictors of coping strategies (multivariable analysis). Boxes are indicative of odds ratio (OR) with error bars indicating upper and lower 95% confidence intervals. Only variables with significant associations are included. Baseline reference categories for each variable were: sex = male; age ≥ 50 years; state = other states; pre-existing mental health conditions = negative response; family/friend infected with COVID-19 = negative response; number of children = none; regional work location = metropolitan, experienced changed relationships = neutral response; and occupation = medical staff.

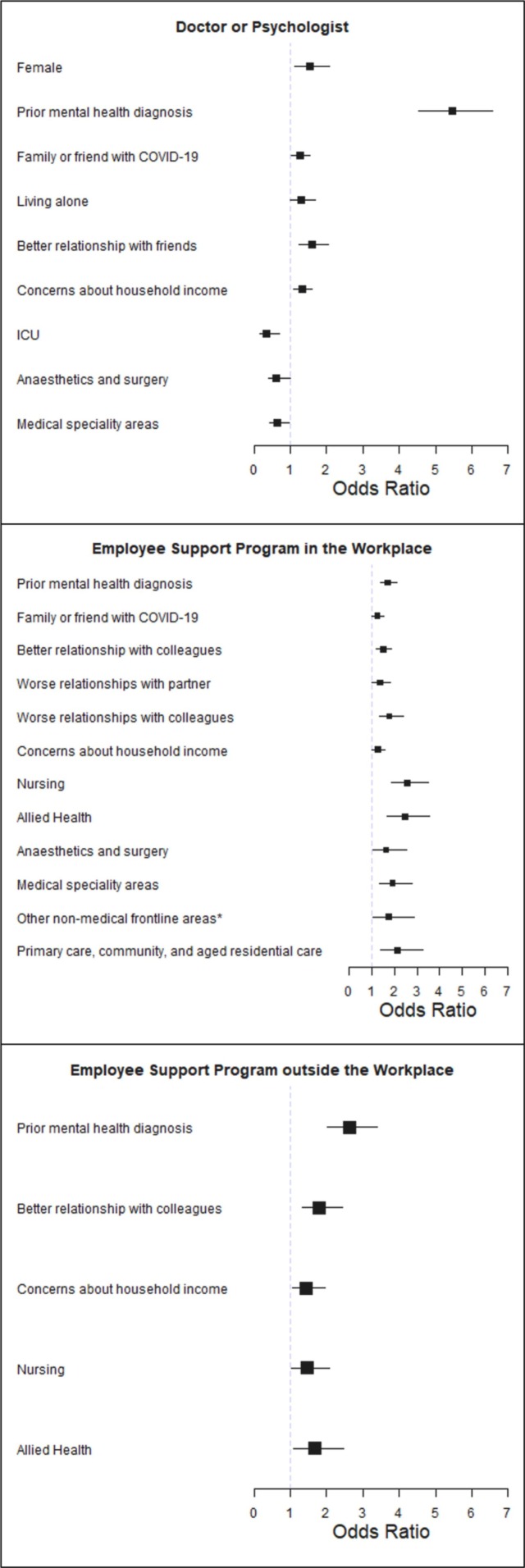

Independent, significant predictors of seeking help from health professionals, such as a general practitioner or psychologist, or accessing support programs included: being female, having a prior mental illness, having family or friends infected with COVID-19, living alone, experiencing altered relationships, having concerns regarding income, occupation and frontline area of work (Fig. 2 ; Supplementary Table 2). Other characteristics (including but not limited to: age, state, regional practice, currently working with COVID-19 patients, elderly people living at home, and income changes) were not associated with seeking help from a health practitioner or support programs.

Fig. 2.

Personal and professional predictors of help-seeking behaviour (multivariate analysis). Boxes are indicative of odds ratio (OR) with error bars indicating upper and lower 95% confidence intervals. Only variables with significant associations are included.Baseline reference categories were: gender = male; pre-existing mental health conditions = negative response; family/friend infected with COVID-19 = negative response; lives alone = lives with others; experienced changed relationships = neutral response; concerns about income = negative response; occupation = medical staff, and frontline area = people working in ED. *Other non-medical frontline area included people working in paramedicine, radiology, pharmacy, pathology and clinical laboratories, or other areas.

3.3. Impact of coping strategies and help-seeking on mental health

Compared to participants with no or only mild mental health symptoms, participants with moderate to severe mental health symptoms were significantly more likely to adopt certain positive coping strategies such as yoga or meditation (anxiety 27.8% vs 24.6%, p = 0.003; depression 28.2% vs 24.6%, p = 0.002; PTSD 28.4% vs 23.5%, p = 0.001, EE 27.0% vs 21.8%, p = 0.001) and psychological wellbeing Apps (anxiety 18.9% vs 12.3%; depression 18.8% vs 11.5%; PTSD 18.2% vs 11.5%; DP 16.1% vs 13.2%; EE 16.3% vs 9.4%; p = 0.001 for all; Supplementary Table 3). Those with moderate to severe symptoms were also, however, significantly less likely to adopt other positive coping strategies such as maintaining exercise (anxiety 40.1% vs 46.8%, p = 0.001; depression 38.0% vs 47.1%, p = 0.001; PTSD 42.3% vs 46.8%, p = 0.001; DP 43.6% vs 45.9%, p = 0.047; EE 43.9% vs 47.9%, p = 0.001), increasing exercise, (anxiety 24.1% vs 25.9%, p = 0.049; depression 23.1% vs 26.2%, p = 0.004; PTSD 26.8% vs 24.6%, p = 0.028) or maintaining social interactions (anxiety 26.7% vs 33.6%; depression 26.7% vs 33.2%; DP 29.0% vs 33.5%; EE 30.5% vs 34.8%; p = 0.001 for all; Supplementary Table 3). Additionally, compared to participants with no or only mild mental health symptoms, having moderate to severe mental health symptoms was significantly associated with increased alcohol use (anxiety 36.0% vs 22.5%; depression 36.6% vs 23.2%; PTSD 34.6% vs 20.8%; DP 34.1% vs 21.8%; EE 30.6% vs 16.3%; p = 0.001 for all; Supplementary Table 3).

Although help-seeking from resources such as clinicians or support programs was generally infrequent with 73.8% (5793) utilising no formal supports, participants with moderate to severe mental health symptoms were significantly more likely than those with no or only mild symptoms to seek help from a doctor or psychologist (anxiety 32.5% vs. 12.7%; depression 29.6% vs. 14.9%; PTSD 27.5% vs. 12.0%; DP 21.6% vs. 16.2%; EE 22.0% vs. 8.9%; p 0.001 for all), employee assistance program (anxiety 10.2% vs. 4.4%; depression 9.1% vs. 5.1%; PTSD 9.2% vs. 3.9%; EE 7.0% vs. 3.6%; p 0.001 for all) or professional support program outside of work (anxiety 5.6% vs.2.2%; depression 4.8% vs. 2.6%; PTSD 4.9% vs. 1.9%; DP 4.0% vs. 2.6%; EE 3.8% vs.1.6%; p 0.001 for all).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge this is the largest study in the world to examine the coping strategies and help-seeking behaviours used by HCWs, across primary and secondary care and all health professions, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prevalence of pre-existing mental health diagnoses was comparable with lifetime incidence for the Australian general public [23]. Many participants experienced moderate to severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, burnout, and PTSD during the pandemic, and reported recognising they were experiencing these symptoms [8]. Yet adoption of positive coping strategies was variable and help-seeking from doctors, psychologists, or support programs was extremely limited. We identified important personal, social and workplace predictors for coping strategies and help-seeking behaviours.

4.1. Predictors and impact of coping strategies

Use of positive coping strategies was more common among HCWs who were younger in age, female, worked in allied health, and had a prior mental health diagnosis. Previous studies have shown that mindfulness offers a helpful way to live with constant change [24], and that a positive thinking style has helped HCWs in Italy [1] and Singapore [25]. Overall, relatively few HCWs in our study used yoga, meditation, or psychological wellbeing apps. These coping strategies were more commonly used by women and by people experiencing moderate to severe symptoms of mental health issues. One possible explanation is that these groups may have better insight into the impact of the pandemic on their mental health and the benefits of these practices. People with children, nurses, those practicing in regional areas, and Victorian residents were less likely to maintain social support during the pandemic. This could reflect a reduced capacity to engage in these activities due to home responsibilities, workplace demands, or lockdown restrictions during the pandemic.

HCWs with moderate to severe mental health symptoms were less likely to engage in other popular positive coping strategies, including physical exercise and maintaining social interactions. While physical exercise and social connections [26] are effective and widely-used strategies for dealing with perceived stress among HCW [27,28], symptoms of mental illness such as reduced energy and anhedonia may make it more difficult for people to maintain or increase exercise levels or social interactions once their symptoms reach a certain severity.

Increased alcohol consumption was more common in those with a prior mental health diagnosis, people aged 31 to 50, people with a family member or friend diagnosed with COVID-19, and those experiencing worse relationships with family and friends. Alcohol consumption is a frequently reported coping strategy for HCWs and often correlates with burnout [29] and workplace stress [30]. Our study similarly found that HCWs with moderate to severe mental health issues were more likely to have increased their alcohol consumption than those with no or minimal symptoms. Notably, a study of Chinese HCWs in the aftermath of SARS found that increased alcohol consumption during the crisis was associated with prolonged increased alcohol consumption up to three years later, highlighting the importance of targeting maladaptive coping strategies early [31]. Interestingly, residents in Victoria, where most of the COVID-19 cases and the strictest lockdowns occurred, were less likely to increase alcohol consumption. This may reflect reduced access to alcohol due to strict lockdown restrictions or the efficacy of targeted campaigns initiated in August 2020 by the Alcohol and Drug Foundation to reduce alcohol consumption during the lockdown [32].

4.2. Predictors and impact of help-seeking behaviour

Although respondents with moderate to severe symptoms of various mental health conditions were more likely to seek help, the vast majority of respondents did not report using any psychological support services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cultural stigma and resistance towards help-seeking behaviour in healthcare is not a new phenomenon and represents a serious concern even prior to the onset of prolonged crises such as COVID-19 [18,19,33,34]. By contrast HCWs with a prior mental health diagnosis were more likely to utilise psychological support services. This may reflect greater familiarity with, and trust in, available services among those with prior experience of them, or prior experience that early engagement with support services is beneficial in times of stress.

Of concern is the prevalence of moderate to severe mental health symptoms in people without a formal diagnosis who were not engaging with any psychological support services. Stigma around mental illness, both internalised and within the health professions, is a long-standing barrier to seeking help among health practitioners [35,36]. The pandemic may also have introduced additional barriers to help-seeking, such as increased pressures on time, difficulty accessing face-to-face care, and a perception that an independent provider or support service may not understand the experience of HCWs on the frontline of the pandemic. In Australia, fears of mandatory reporting to a regulatory authority have previously been cited as another barrier to help seeking [37]. However, mandatory reporting laws and guidelines clearly indicate that such reports are only required where an impaired practitioner places the public at risk of substantial harm, and that notification is not required where effective strategies are in place to manage an illness, such as a practitioner undergoing treatment or taking sick leave.

Our findings demonstrate that there are unmet needs for appropriate mental health care and support services among HCWs. The growth of peer support services during the pandemic suggests that some clinicians may prefer to engage with people who are able to understand their experience [38]. Targeted outreach programs developed in response to COVID-19 in the US have shown efficacy in generating mental health referrals for up to a third of participants [39].

Women were more likely to utilise formal psychological support services than men. This is reflective of trends seen in the Australian general public [40] with only a quarter of men indicating they would be likely to seek help if facing a mental health crisis, and only 40% sought help from a mental health professional while experiencing depression, anxiety, or suicidal ideation [41]. Notably, certain frontline areas were less likely to engage support services. People working in ICU, anaesthetics, surgical areas, and medical speciality areas were all less likely to speak to a doctor or psychologist than emergency department staff. However, people working in anaesthetics, and medical speciality areas were more likely to use a workplace employee support service. Occupational trends were also noted, with nurses and allied health workers being more likely to utilise employee and professional support services at their workplace or externally compared to medical staff. This may be partly explained by the unionisation of nursing workforces and is indicative of an unmet need in medical staff.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

This study has a number of strengths. It is the largest survey in the world to explore the experiences of HCWs in multiple health professions and roles across both primary or secondary care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although most respondents were female, this is consistent with the observed demographic trends of the Australian health workforce, with both the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency demonstrating that 75% of the Australian health workforce is female [[42], [43], [44]]. The broad survey dissemination strategy prevented calculation of a response rate. Voluntary participation in the study may have introduced selection bias, with people experiencing mental health symptoms potentially more likely to engage in the survey, which may have resulted in over-reporting of mental health issues. Nevertheless, voluntary participation in research is a core ethical principle. Participant responses were measured at only one time-point. In practice there is likely to be a complex inter-relationship among stressors at home and at work, lockdown restrictions, coping strategies, and poor mental health symptoms [45] that cannot be untangled with a cross-sectional survey alone. Longitudinal research is urgently required to better understand the relationship among these factors. In addition, qualitative research is needed to explore the barriers to accessing support services, and the extent to which these reflect long-standing patterns of poor help-seeking behaviour among HCWs or whether there were unique factors associated with the pandemic.

5. Conclusion

This study highlights concerning mental health issues among frontline HCWs in Australia during the second wave of the pandemic, with few HCWs utilising support services and some engaging in maladaptive coping strategies. There is an immediate need for better access to psychological support services that are both desired and acceptable to HCWs in both day to day, but even more so during crisis events. Targeted outreach services that address maladaptive coping strategies and overcome resistance or inability to access support services by at-risk groups and occupations are urgently needed to protect the frontline health workforce.

Funding

The Royal Melbourne Hospital Foundation and the Lord Mayor's Charitable Foundation kindly provided financial support for this study. Funding bodies had no role in the research activity. All authors were independent from the funders and had access to the study data.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge and thank the Royal Melbourne Hospital Foundation and the Lord Mayor's Charitable Foundation for financial support for this study. We wish to thank the numerous health organisations, universities, professional societies, associations and colleges, and many supportive individuals who assisted in disseminating the survey. We thank the Royal Melbourne Hospital Business Intelligence Unit who provided and hosted the REDCap electronic data capture tools.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.08.008.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Survey questionnaire

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Babore A., Lombardi L., Viceconti M.L., Pignataro S., Marino V., Crudele M., et al. Psychological effects of the COVID-2019 pandemic: Perceived stress and coping strategies among healthcare professionals. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113366. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson H., Malpas C.B., Burrell A.J.C., Gurvich C., Chen L., Kulkarni J., et al. Burnout and psychological distress amongst Australian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Australasian Psychiatry. 2020;29(1):1–5. doi: 10.1177/1039856220965045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hummel S., Oetjen N., Du J., Posenato E., Resende de Almeida R.M., Losada R., et al. Mental Health Among Medical Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Eight European Countries: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e24983. doi: 10.2196/24983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W.R., Wang K., Yin L., Zhao W.F., Xue Q., Peng M., et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(4):242–250. doi: 10.1159/000507639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West C.P., Dyrbye L.N., Sinsky C., Trockel M., Tutty M., Nedelec L., et al. Resilience and Burnout Among Physicians and the General US Working Population. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9385. [e209385-e] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milner A.J., Maheen H., Bismark M.M., Spittal M.J. Suicide by health professionals: a retrospective mortality study in Australia, 2001–2012. Medical Journal of Australia. 2016;205(6):260–265. doi: 10.5694/mja15.01044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shanafelt T.D., Boone S., Tan L., Dyrbye L.N., Sotile W., Satele D., et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smallwood N., Karimi L., Bismark M., Putland M., Johnson D., Dharmage S., et al. High levels of psychosocial distress among australian frontline health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. General Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2021-100577. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gloria C.T., Steinhardt M.A. Relationships Among Positive Emotions, Coping. Resilience and Mental Health. Stress Health. 2016;32(2):145–156. doi: 10.1002/smi.2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garnett C., Jackson S.E., Oldham M., Brown J., Steptoe A., Fancourt D. Factors associated with drinking behaviour during COVID-19 social distancing and lockdown among adults in the UK. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2021;219:108461. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang L., Ren H., Cao R., Hu Y., Qin Z., Li C., et al. The Effect of COVID-19 on Youth Mental Health. Psychiatr Q. 2020;91(3):841–852. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bu F., Steptoe A., Mak H.W., Fancourt D. Time-use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a panel analysis of 55,204 adults followed across 11 weeks of lockdown in the UK. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.18.20177345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alosaimi F.D., Alawad H.S., Alamri A.K., Saeed A.I., Aljuaydi K.A., Alotaibi A.S., et al. Stress and coping among consultant physicians working in Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2018;38(3):214–224. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2018.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hugelius K., Adolfsson A., Ortenwall P., Gifford M. Being Both Helpers and Victims: Health Professionals’ Experiences of Working During a Natural Disaster. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2017;32(2):117–123. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X16001412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maunder R.G., Leszcz M., Savage D., Adam M.A., Peladeau N., Romano D., et al. Applying the lessons of SARS to pandemic influenza: an evidence-based approach to mitigating the stress experienced by healthcare workers. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(6):486–488. doi: 10.1007/BF03403782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran T.D., Hammarberg K., Kirkman M., Nguyen H.T.M., Fisher J. Alcohol use and mental health status during the first months of COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:810–813. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2020. Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey: Coronavirus (COVID-19) impacts on jobs, unpaid care, domestic work, mental health and related services, and life after COVID-19 restrictions. 6–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes B., Prihodova L., Walsh G., Doyle F., Doherty S. What’s up doc? A national cross-sectional study of psychological wellbeing of hospital doctors in Ireland. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Kelly F., Manecksha R.P., Quinlan D.M., Reid A., Joyce A., O’Flynn K., et al. Rates of self-reported ‘burnout’ and causative factors amongst urologists in Ireland and the UK: a comparative cross-sectional study. BJU international. 2016;117(2):363–372. doi: 10.1111/bju.13218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Australian Government Department of Health . In: Coronavirus (COVID-19) at a glance – 23 October 2020. Do Health., editor. Department of Health; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maslach C., Jackson S.E., Leiter M.P. Scarecrow Education; Lanham, MD, US: 1997. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Third edition. Evaluating stress: A book of resources; pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slade T., Johnston A., Teesson M., Whiteford H., Burgess P., Pirkis J., et al. Department of Health and Ageing; Canberra: 2007. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing; p. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedderman E., O’Doherty V., O’Connor S. Mindfulness moments for clinicians in the midst of a pandemic. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chew Q.H., Chia F.L., Ng W.K., Lee W.C.I., Tan P.L.L., Wong C.S., et al. Perceived Stress, Stigma, Traumatic Stress Levels and Coping Responses amongst Residents in Training across Multiple Specialties during COVID-19 Pandemic-A Longitudinal Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):09. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zwack J., Schweitzer J. If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? Resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):382–389. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318281696b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shechter A., Diaz F., Moise N., Anstey D.E., Ye S., Agarwal S., et al. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;66:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garber M.C. Exercise as a Stress Coping Mechanism in a Pharmacy Student Population. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(3):50. doi: 10.5688/ajpe81350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lebares C.C., Braun H.J., Guvva E.V., Epel E.S., Hecht F.M. Burnout and gender in surgical training: A call to re-evaluate coping and dysfunction. American journal of surgery. 2018;216(4):800–804. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medisauskaite A., Kamau C. Does occupational distress raise the risk of alcohol use, binge-eating, ill health and sleep problems among medical doctors? A UK cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu P., Liu X., Fang Y., Fan B., Fuller C.J., Guan Z., et al. Alcohol abuse/dependence symptoms among hospital employees exposed to a SARS outbreak. Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire) 2008;43(6):706–712. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alcohol and Drug Foundation Break the Habit Campaign 2020. https://www.littlehabit.com.au/about/break-the-habit-campaign Available from:

- 33.Fitzpatrick O., Biesma R., Conroy R.M., McGarvey A. Prevalence and relationship between burnout and depression in our future doctors: a cross-sectional study in a cohort of preclinical and clinical medical students in Ireland. BMJ open. 2019;9(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forbes M.P., Iyengar S., Kay M. Barriers to the psychological well-being of Australian junior doctors: a qualitative analysis. BMJ open. 2019;9(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mackinnon K., Everett T., Holmes L., Smith E., Mills B. Risk of psychological distress, pervasiveness of stigma and utilisation of support services: Exploring paramedic perceptions. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine. 2020;17 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beyond Blue . 2019. National Mental Health Survey of Doctors and Medical Students. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bismark M.M., Morris J.M., Clarke C. Mandatory reporting of impaired medical practitioners: protecting patients, supporting practitioners. Internal Medicine Journal. 2014;44(12a):1165–1169. doi: 10.1111/imj.12613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bridson T.L., Jenkins K., Allen K.G., McDermott B.M. PPE for your mind: a peer support initiative for health care workers. Medical Journal of Australia. 2021;214(1) doi: 10.5694/mja2.50886. [8–11.e1] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mellins C.A., Mayer L.E.S., Glasofer D.R., Devlin M.J., Albano A.M., Nash S.S., et al. Supporting the well-being of health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The CopeColumbia response. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;67:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milner A., Disney G., Byars S., King T.L., Kavanagh A.M., Aitken Z. The effect of gender on mental health service use: an examination of mediation through material, social and health-related pathways. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2020;55(10):1311–1321. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01844-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terhaag S., Quinn B., Swami N., Daraganova G. In: Mental health of Australian males: depression, suicidality and loneliness. Australian Government Department of Health AIoFS, editor. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Health workforce [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2020. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-workforce [cited 2021 Feb. 14]. Available from:

- 43.Medical Board of Australia . 2021. Registration Data Table - December 2020 2020 10th February. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nursing and Midwifery Board . 2020. Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia Registrant data. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu W., Wei Y., Meng X., Li J. The mediation effects of coping style on the relationship between social support and anxiety in Chinese medical staff during COVID-19. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1007. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05871-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Survey questionnaire

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.