Abstract

Bovine mastitis, caused by Prototheca bovis, has received much attention worldwide. To investigate the status of P. bovis infection in dairy farms of Hubei, we collected 1,158 milk samples and 90 environmental samples from 14 dairy farms of Hubei, China. The isolates were identified with traditional biological methods and molecular biological techniques, and their pathogenicity was tested through mice infection experiments. Isolates from 57 milk and 20 environmental samples were identified as P. bovis. The mice infection tests proved that the isolated P. bovis could cause mastitis in mice, manifesting as severe red swelling of the mammary glands. Histopathological analysis of tissue sections showed necrosis and nodules lesions formed in the infected mice mammary tissue, accompanied by macrophage and neutrophil infiltration. These results suggested the existence of pathogenic P. bovis in dairy farms of the Hubei province, China, with brewer’s grains and fresh feces possibly playing important roles in the spread of this disease.

Keywords: bovine mastitis, dairy farm, histopathological change, pathogen identification, Prototheca bovis

Prototheca is an alga of the class Trebouxiophyceae (phylum Chlorophyta) with a diameter of 7 to 30 µm. There are two main lineages in this genus, which predominantly comprise dairy cattle-associated and human-associated species. The dairy cattle-associated species include P. ciferrii (formerly P. zopfii genotype 1), P. bovis (formerly P. zopfii genotype 2), and P. blaschkeae [9]. Prototheca was first identified as a pathogen causing clinical mastitis in dairy cows [11]. Since then, researchers worldwide have reported on bovine mastitis caused by Prototheca [3, 6, 22]. The vast majority of P. bovis isolates from milk samples of cows with mastitis have been identified as genotype 2. Moreover, studies have shown P. ciferrii and P. bovis are present throughout dairy farm environments [1, 8]. Most isolates from bedding samples, feces, feed, and drinking water are usually P. bovis, while few belong to P. ciferrii or P. blaschkeae [5, 16, 18]. These data seem to imply that environmental P. bovis is a potential source of infection.

As Prototheca is a concern worldwide, a variety of Prototheca identification methods have been developed. Initially, Prototheca was identified by growth characteristics, biochemical reactions, and serotyping [19, 20]. Subsequently, a biotype-specific PCR method was devised based on the analysis of 18S rRNA gene sequences [21]; this facilitated the creation of genotype-specific restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assays using three genotype-specific endonucleases [13]. Previously, a specific quantitative PCR assay was developed for the detection and identification of P. ciferrii, P. bovis, and P. blaschkeae in clinical samples, which showed high specificity and sensitivity [15]. The species-specific differences in the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences, together with their considerable length variation, have allowed species-specific PCR to successfully identify P. bovis and P. blaschkeae in milk samples [12]. Based on the species-specific polymorphisms in the partial cytb gene, Jagielski et al. developed a PCR-RFLP method for identification and differentiation of all Prototheca species described so far, which was proposed as a new gold standard in diagnostics of protothecal infections in humans and animals [7].

P. bovis has been isolated and identified in the Beijing, Tianjin, Shandong, and Jiangsu provinces of China [4, 14] and, therefore, may be present in more areas of China. At present, there is a lack of information about P. bovis infection in the dairy cows of Hubei province. So far, not much is known about the situation of P. bovis infection in dairy cows of the Hubei province. Our study aims to investigate P. bovis infection and analyze environmental P. bovis in dairy farms of the Hubei province. In addition, a mouse infection test was conducted to verify the pathogenicity of the P. bovis isolates. This study lays the foundation for further epidemiological research as well as prevention and control of diseases caused by P. bovis in Hubei, China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Milk samples (n=1,158) were collected from 14 dairy farms of the Hubei province, China. Environmental samples (n=90) from silage, brewer’s grains, concentrated feed, Leymus chinensis, straw, water from the drinking trough, fresh feces, mattress material, and stall soil were collected from a P. bovis positive dairy farm. All the primers were synthesized by Wuhan Tianyihuiyuan Biotechnology Co., Inc., Wuhan, China. The P. bovis strain used was stored in our laboratory. Premix Taq was purchased from Takara Biomedical Technology Co., Inc., Beijing, China. The restriction endonucleases RsaI and TaiI were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA. The equipment included an ETC811 PCR machine from EASTWIN Biotech Co., Beijing, China, a DYY-6C electrophoresis unit from Beijing LIUYI Biotechnology Co., Beijing, China, and a BIO-BEST 135A Gel imaging analysis system from the GOLD-SIM International Group, Beijing, China. Barbital was bought from Tianjin Guangfu Fine Chemical Research Institute, Tianjin, China.

Animals and ethics statement

Thirty specific pathogen-free (SPF) BALB/c pregnant female mice at 14 days of gestation were purchased from Hunan Slack Jingda Experimental Animal Co., Inc., SCXK2016-0002; Hunan, China.

All mice were routinely raised in clean cages at a constant temperature and humidity, were given sufficient nutrient pellet feed and sterilized drinking water. We prevented unnecessary suffering of the animals via proper management and laboratory techniques. Our animal research was reviewed and approved by the Animal Experimental Ethical Inspection of Laboratory Animal Centre, Huazhong Agriculture University, China. Approval number: HZAUMO-2018-029.

Isolation and purification of P. bovis

All milk samples, internal environmental samples of the dairy farm, and transport environment samples were aseptically collected and stored at 4°C. Samples were immediately sent to the laboratory for inspection. Under sterile conditions, milk samples were shaken and mixed. The dilution method was used for environmental samples (10 g of every environmental sample was added to 100 ml sterile saline solution for reserve). Then, 100 µl of samples was evenly spread on the Prototheca isolation medium (PIM) [17] and incubated at 37°C for 48–72 hr. Each suspected single colony was selected for subculture and purification. The suspected isolates were stored in glycerol at −80°C until further use.

Identification of P. bovis

P. bovis was identified through examination of colony characteristics, staining along with microscopic examination, and biochemical identification. Preliminary morphology of a single colony was observed with the naked eye. Size, shape, and color of the bacteria were observed under a microscope by staining with gram staining and lactophenol cotton blue stain solutions. A GEN III 96-well microplate (Biolog Inc., Hayward, CA, USA) inoculated with the P. bovis suspension was tested by the kinetic method [20, 23]. The whole detection reaction time was set to 60 hr, and the time interval between each detection point was 15 min. After the reaction was complete, data were collected.

Furthermore, based on the species-specific polymorphisms in the partial cytb gene, PCR-RFLP methods were used to identify P. bovis. The primers used are shown in Table 1. The cytb PCR program comprised the initial denaturing step at 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 50°C, and 30 sec at 72°C; followed by the final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The target fragment of the PCR product was 644 bp. This target fragment was digested using TaiI and RsaI. PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel, while the DNA fragments after RFLP required electrophoresis on a 4% agarose gel. The electrophoresis results were analyzed by a gel imaging system [7].

Table 1. The sequences of the primers used in this study for detecting Prototheca bovis.

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Target fragment size |

|---|---|---|

| cytb-F | GyGTwGAACAyATTATGAGAG | 644 bp |

| cytb-R | wACCCATAArAArTACCATTCwGG |

y, h, r, and w represent degenerate nucleotides. y could be C or T; h could be A, C, or T; r could be A or G; w could be A or T.

Three-month monitoring of a dairy farm with P. bovis infection

The relationship between P. bovis infection and its somatic cell count (SCC) in lactating cows was investigated by monitoring a dairy farm with the highest positive rate of P. bovis for three consecutive months. During this period, the cows used for sampling were not treated with drugs. After the milk samples from the dairy cows were collected regularly every month, the samples were spread on the PIM. The milk samples were sent to the Dairy Herd Improvement testing center of Hubei province to determine the SCC of each milk sample. Finally, a statistical analysis was conducted.

Testing P. bovis infection in mice

Here, P. bovis isolated from milk samples of cows with mastitis and high SCC from a dairy farm in Hubei was selected for an inoculum, and prepared as a saline suspension containing 104–107 colony forming units (CFU)/ml; the inoculum was stored at 4°C before use. Pregnant mice were maintained normally until 3–5 days after delivery, when the mothers were subjected to the test. Thirty mice were randomly distributed into six groups (n=5): 104 CFU, 105 CFU, 106 CFU, 107 CFU, a saline control group, and a blank control group. The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of barbital sodium (50 mg/kg of body weight), and P. bovis was inoculated into the fourth pair of mammary glands of each mouse by perfusion (perfusion volume: 100 µl). The clinical manifestations and body weight of the mice were monitored daily until one day before the infection and for seven days after the infection. At day seven after infection, blood samples were collected from all the mice after they were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The blood samples were used for white-blood cell (WBC) counting to assess the inflammatory response. The fourth pair of mammary glands was aseptically excised. One side of the mammary gland was taken and weighed, added to sterile PBS (1 ml per 0.5 g tissue), and then homogenized. Next, 100 µl of the homogenate was diluted to 10−1, 10−2, and 10−3, coated on PIM medium, cultured at 37°C for 48 hr and CFUs were counted. The other side was subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining for histopathological analysis of the thin tissue sections [2].

Statistical analyses

One-way analysis of variance was performed using SPSS 18.0 and GraphPad Prism 7. Experimental data were expressed as mean ± SD, P>0.05 indicated non-significant, P<0.05 and P<0.01 indicated a significant difference and extremely significant difference, respectively.

RESULTS

Isolation and identification of P. bovis

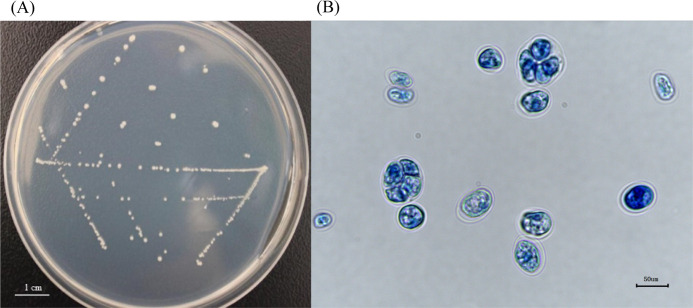

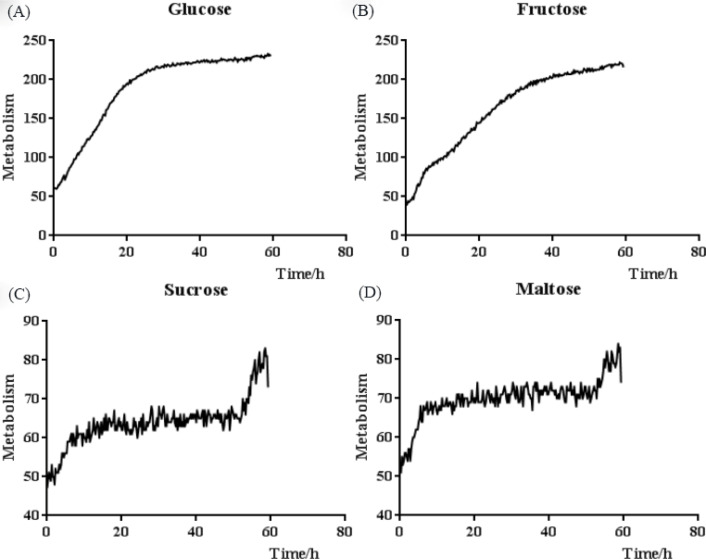

The isolates obtained from the milk and environmental samples were purified. The purified stand-alone colonies appear as regular circles of 0.3 mm diameter on the PIM; their color is white or yellowish-white, and their edges are smooth and dull, with small protrusions at the center (Fig. 1A). When the isolates were stained with lactophenol cotton blue, blue-stained or light-blue-stained, rounded thallus can be seen under an optical microscope (400× magnification), with endospores at different proliferative stages; most of the endospores were irregularly segregated. A transparent outer wall encircled the outermost layer of the algae (Fig. 1B). The continuous kinetic curve analysis showed that the isolates can utilize monosaccharides, such as glucose and fructose (Fig. 2A and 2B), but not maltose, sucrose, or other disaccharides (Fig. 2C and 2D).

Fig. 1.

Growth and staining of Prototheca bovis on the Prototheca isolation medium. (A) Isolates appear as approximate round white colonies. (B) Endospores at different proliferative stages under an optical microscope (400× magnification).

Fig. 2.

Biochemical continuous kinetic curve analysis of Prototheca bovis. (A) and (B) show that the isolates utilizing glucose or fructose yielded a distinct exponential phase. (C) and (D) show that the isolates with maltose or sucrose do not yield an exponential phase.

Out of 1,158 milk samples from 14 dairy farms in Hubei province, 57 isolates originating from four dairy farms were identified as P. bovis. The rate of test-positive dairy farms was 28.6% (4/14), and the infection rate of P. bovis was 4.9% (57/1,158). The positive rates of milk samples from these four dairy farms were 7.1%, 9.9%, 12.0%, and 27.4%, respectively (Table 2). Furthermore, 20 positive samples (10 from brewer’s grains and 10 from fresh feces) were isolated from 90 environmental samples collected in a P. bovis positive dairy farm (Table 3). Notably, P. bovis was found on the inner panels and in the brewer’s grains of the transport truck carrying the brewer’s grains to the dairy farm.

Table 2. Results of isolation and identification of Prototheca bovis in milk samples from different dairy farms.

| Farms | No. of samples | P. bovis isolates (%) | Genotype identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28 | 2 (7.1%) | P. bovis |

| 2 | 28 | 0 | n |

| 3 | 111 | 0 | n |

| 4 | 106 | 0 | n |

| 5 | 294 | 29 (9.9%) | P. bovis |

| 6 | 27 | 0 | n |

| 7 | 93 | 0 | n |

| 8 | 103 | 0 | n |

| 9 | 95 | 0 | n |

| 10 | 25 | 3 (12.0%) | P. bovis |

| 11 | 84 | 23 (27.4%) | P. bovis |

| 12 | 62 | 0 | n |

| 13 | 52 | 0 | n |

| 14 | 50 | 0 | n |

n, Negative Prototheca detection.

Table 3. Results of isolation and identification of Prototheca bovis in environmental samples from different sources.

| Source | Samples | Prototheca spp. positive samples | Genotype identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silagea | 10 | 0 | n |

| Brewer’s grainsa | 10 | 10 | P. bovis |

| Concentrated feeda | 10 | 0 | n |

| Leymus chinensisa | 10 | 0 | n |

| Strawa | 10 | 0 | n |

| Water from the drinking trough | 10 | 0 | n |

| Fresh feces | 10 | 10 | P. bovis |

| Mattress material | 10 | 0 | n |

| Stall soil | 10 | 0 | n |

n, Negative Prototheca detection. aFull mixed diet.

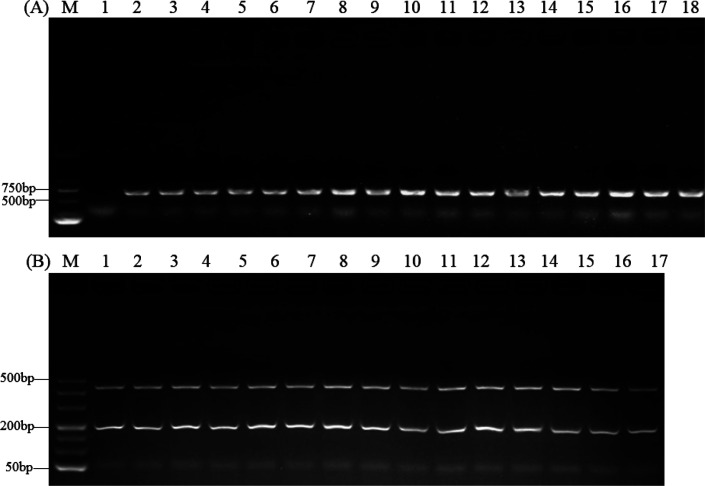

The PCR-RFLP identification results are presented in Fig. 3 (only some isolates are illustrated); the isolates were identified as P. bovis and preliminarily believed to be the main Prototheca algae infection in dairy farms in the Hubei province.

Fig. 3.

Identification of Prototheca bovis by cytb PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). (A) PCR amplification of the partial cytb gene. The target fragment of the PCR product was 644 bp. Lanes 2–18: Isolated strains (only some isolates are illustrated), 1: Negative control, M: Marker. (B) Cytb PCR-RFLP results of isolates. After the PCR products was digested using TaiI and RsaI, the PCR product (644 bp) of all isolates (only some isolates are illustrated) was split into fragments of 47, 161, and 411 bp. Lanes 1–17: Isolated strains (only some isolates are illustrated), M: Markers.

Three-month monitoring of a dairy farm with P. bovis infection

The prevalence of P. bovis infection over three months increased from 15.5% to 48.2%, to 76.4%. Simultaneously, the prevalence of milk samples with high SCC (>2 × 106/ml, does not meet the national standard of China) also increased from 27.4% to 37.6% to 48.3%. Among the P. bovis positive samples, the prevalence of milk samples with high SCC was 38.5%, 46.3%, and 54.4%, across the three months. In P. bovis positive samples, the SCC value was significantly higher (P<0.05) than the average level. Nevertheless, the SCC score of some milk samples was low despite the cow being infected with P. bovis (Table 4).

Table 4. Results of three-month monitoring of a dairy farm including total number of milk samples and the number of samples positive for Prototheca bovis.

| Month | Milk samples | Samples positive for P. bovis |

|---|---|---|

| First month | 84 (23) | 13 (5) |

| Second month | 85 (32) | 41 (19) |

| Third month | 89 (43) | 68 (37) |

Numbers in brackets represent samples with somatic cell count (SCC) that do not meet the national standard of China (SCC >2 × 106/ml).

P. bovis infection test in mice

After mice mammary glands were perfused with different amounts of P. bovis, no mice died within seven days of infection. During the experiment, the clinical manifestations of mastitis were not seen in the 104 CFU group, saline control and blank control group. Nevertheless, the mice in the 105 CFU, 106 CFU, and 107 CFU groups showed various degrees of clinical manifestations like unkemptness, emaciation, and listlessness. The groin near the hind limbs was heavily swollen and the fourth pair of infected mammary glands was seen to have extensive adhesions within the subcutaneous tissue and peritoneum. The mammary glands were severely swollen and appeared to have a white or yellowish-white color with a brittle texture. No significant lesions were found in the upper and lower mammary glands. These pathological changes were not found in the saline control and blank control group.

After continuous monitoring of the body weight in each group (Table 5), a significant decrease in body weight (P<0.01) was observed from day two to seven compared to day zero in the 106 and 107 CFU groups. A significant difference (P<0.05) was seen in the body weight of the 105 CFU group on days three and four compared to day zero. In contrast, in the 104 CFU group and saline control group, no difference (P>0.05) in body weight was seen between days seven and zero.

Table 5. Results of continuous weight (in g) monitoring (mean ± standard deviation) in each group.

| Days | 104 CFU (n=5) | 105 CFU (n=5) | 106 CFU (n=5) | 107 CFU (n=5) | Saline control (n=5) | Blank control (n=5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 26.4 ± 1.9 | 29.6 ± 2.2 | 29.8 ± 1.5 | 31.2 ± 2.1 | 26.4 ± 1.6 | 27.2 ± 0.4 |

| 1 | 26.6 ± 1.0 | 29.0 ± 1.3 | 27.6 ± 0.8* | 29.0 ± 1.3 | 26.8 ± 1.3 | 25.8 ± 1.2 |

| 2 | 26.2 ± 0.7 | 27.2 ± 1.3 | 25.0 ± 1.1** | 25.4 ± 2.4** | 26.6 ± 1.6 | 25.6 ± 1.0* |

| 3 | 26.0 ± 1.1 | 26.2 ± 1.3* | 25.0 ± 1.8** | 25.6 ± 2.4** | 25.8 ± 1.7 | 25.4 ± 0.8** |

| 4 | 26.0 ± 0.9 | 25.8 ± 1.8* | 25.0 ± 1.8** | 25.0 ± 2.4** | 25.4 ± 0.8 | 26.0 ± 1.1 |

| 5 | 26.2 ± 1.2 | 26.2 ± 2.0 | 25.0 ± 1.1** | 24.8 ± 2.0** | 26.4 ± 0.8 | 25.8 ± 1.7 |

| 6 | 26.2 ± 1.2 | 26.8 ± 1.5 | 26.2 ± 1.5** | 25.4 ± 1.4** | 27.0 ± 1.3 | 26.0 ± 1.7 |

| 7 | 26.2 ± 1.0 | 27.2 ± 1.5 | 25.6 ± 1.0** | 25.0 ± 1.9** | 25.6 ± 0.8 | 26.0 ± 1.1 |

Compared to day zero, * indicates significance at P<0.05, ** indicates significance at P<0.01. CFU, colony forming units.

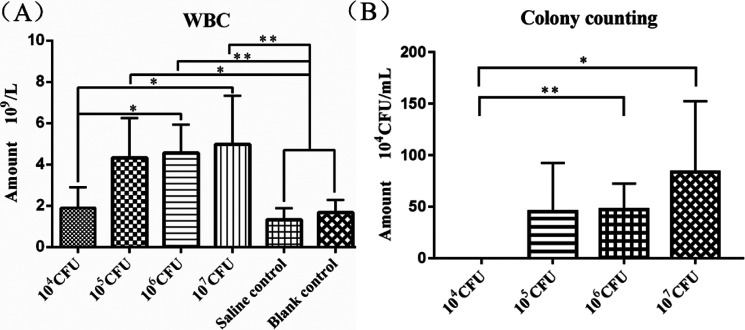

The WBC count was significantly higher in the 105 CFU group (P<0.05), 106 CFU group (P<0.01), and 107 CFU group (P<0.01) than in the two control groups. It was also significantly higher in the 106 CFU group (P<0.05) and 107 CFU group (P<0.05) than in the 105 CFU group (Fig. 4A). The colony counting assay of the mammary gland homogenates showed a significant increase in colony numbers in the 106 (P<0.05) and 107(P<0.05) CFU groups compared to the 104 CFU group, while no colonies were seen in the 104 group and the two control groups (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

White-blood cell (WBC) counting and colony counts in the experimental and control groups. (A) WBC counts in blood of the four experimental groups and the two control groups. (B) Colony counting in mammary glands of the four experimental groups.

Figure 5 shows the histopathologic changes of mammary glands tissue in mice infected with P. bovis. All four doses of infection could lead to varying degrees of pathological changes including infiltration of epithelioid cells (macrophages) and neutrophils (Fig. 5A–D). Connective tissue reactions, consisting of fibroblast proliferation, neovascularization, and collagen deposition, were observed around the necrotic mammary ducts (Fig. 5A–C). In addition to inflammation and connective tissue reactions, many pathogens corresponding to P. bovis were present within the mammary duct lesions (Fig. 5D). In contrast, the mammary glands in the saline control and blank control groups had normal acinar and glandular structures (Fig. 5E and 5F).

Fig. 5.

Histopathological analysis of mice mammary tissues after infected with Prototheca bovis: The hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining images show histopathological findings of the mammary gland of the 104 colony forming units (A, B), 105 colony forming units (C, D), saline control (E), and blank control (F) groups. Panels B and D (1,000×) are higher magnification of panels A and C (400×), respectively. (A, B) Multifocal necrosis of mammary ducts of variable sizes is infiltrated by epithelioid cells and neutrophils, and surrounded by hyperplasia of fibrous connective tissue. (C) Coagulative necrosis of mammary duct epithelia is surrounded by a layer of epithelioid cells, and connective tissue hyperplasia with inflammatory infiltrate. (D) Many pathogens corresponding to Prototheca bovis (solid arrows) in the necrotic lesion. (E, F) The mammary gland tissue depicts normal acinar and glandular structures.

DISCUSSION

With the advancement of research on P. bovis, many researchers have devised new identification methods providing multiple options for P. bovis identification. Jagielski et al. verified that the cytb gene can serve as a reference for research on P. bovis identification [7]. Our results showed that P. bovis is present in dairy cows of the Hubei province, China. Among the 14 dairy farms investigated in this study, four dairy farms were positive for P. bovis, and the positive rate of samples ranged from 7.1% to 27.4%. The positive rate of P. bovis was between 10.0% and 18.1% in milk samples from six Holstein dairy herds in Beijing, Tianjin and Shandong. This indicated that the infection of P. bovis was different in different areas of China [14]. Further epidemiological investigation is required to confirm if P. blaschkeae or P. ciferrii have clinically important roles in bovine mastitis in China.

We found that P. bovis was present in brewer’s grains and fresh feces after analyzing environmental samples from a dairy farm with P. bovis infections. Brewer’s grains, an important feed additive for dairy cattle breeding in China, are the main by-product of the beer industry. These grain residues from beer fermentation provide good conditions for microbial growth and reproduction, especially in warm and humid areas, such as Hubei province in China. Moreover, we isolated P. bovis from the truck that transported the brewer’s grains to the affected dairy farm. This finding suggests that vehicles transporting brewer’s grains may be a critical means of P. bovis infection and proliferation. However, we found that P. bovis also exists in cow feces, consistent with the findings of a recent report from Japan [10], suggesting that the incidence of bovine protothecal mastitis was related to persistent infection of the intestine, and the source of infection may be feces. Nevertheless, the entry of P. bovis into the dairy farm and its transmission in the field requires further investigation.

In addition, we found that P. bovis could be isolated from milk samples with different SCC values. Therefore, focus should be on cows with higher SCC values or clinical bovine mastitis and on those without mastitis symptoms with normal SCC values. These results are in line with earlier studies [22]. Asymptomatic dairy cows infected with P. bovis may also transmit P. bovis; however, this might relate to the developmental stage of the disease, the virulence of P. bovis, autoimmunity, and other factors.

A murine protothecal mastitis model was used in this study [2]. The results showed that 104 CFU P. bovis inoculation could cause pathological changes including mammary duct epithelial cell necrosis, shedding, the proliferation of fibrous connective tissue around the duct and acinus, and a large number of infiltrating neutrophils. Also, the results of the WBC count showed that the 104 CFU P. bovis inoculation could increase WBCs in mice. With increases in the challenge dose, the number of WBCs in mice also increased. The two results are basically consistent. Furthermore, the results of HE staining showed that P. bovis could be seen in the mammary duct of mice in the 105 CFU group, which was consistent with the colonization results. In conclusion, P. bovis isolated from milk samples of cows in this study could induce mastitis. More attention should be paid to P. bovis in mastitis, and further research on prevention and control is needed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Science and Technology Innovation Platform Projects from Science and Technology Department of Hubei Province (2018BEC494) and the Wuhan Science and Technology Bureau ([2015] No. 37), China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adhikari N., Bonaiuto H. E., Lichtenwalner A. B.2013. Short communication: dairy bedding type affects survival of Prototheca in vitro. J. Dairy Sci. 96: 7739–7742. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-6773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang R., Yang Q., Liu G., Liu Y., Zheng B., Su J., Han B.2013. Treatment with gentamicin on a murine model of protothecal mastitis. Mycopathologia 175: 241–248. doi: 10.1007/s11046-013-9628-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbellini L. G., Driemeier D., Cruz C., Dias M. M., Ferreiro L.2001. Bovine mastitis due to Prototheca zopfii: clinical, epidemiological and pathological aspects in a Brazilian dairy herd. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 33: 463–470. doi: 10.1023/A:1012724412085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai D., Liao J., Feng Q., Huang P., Liang X. H., Wang J., Qin A. J., Jin W. J.2018. Isolation and identification of 4 Prototheca zopfii sourced from cow. Anhui Nongye Kexue 46: 78–86 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao J., Zhang H. Q., He J. Z., He Y. H., Li S. M., Hou R. G., Wu Q. X., Gao Y., Han B.2012. Characterization of Prototheca zopfii associated with outbreak of bovine clinical mastitis in herd of Beijing, China. Mycopathologia 173: 275–281. doi: 10.1007/s11046-011-9510-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jagielski T., Lassa H., Ahrholdt J., Malinowski E., Roesler U.2011. Genotyping of bovine Prototheca mastitis isolates from Poland. Vet. Microbiol. 149: 283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jagielski T., Gawor J., Bakuła Z., Decewicz P., Maciszewski K., Karnkowska A.2018. cytb as a new genetic marker for differentiation of prototheca species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 56: 10. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00584-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jagielski T., Krukowski H., Bochniarz M., Piech T., Roeske K., Bakuła Z., Wlazło Ł., Woch P.2019. Prevalence of Prototheca spp. on dairy farms in Poland-a cross-country study. Microb. Biotechnol. 12: 556–566. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagielski T., Bakuła Z., Gawor J., Maciszewski K., Kusber W.H., Dyląg M., Nowakowska J., Gromadka R., Karnkowska A.2019. The genus Prototheca (Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta) revisited: Implications from molecular taxonomic studies. Algal Res. 43: 101639. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2019.101639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurumisawa T., Kano R., Nakamura Y., Hibana M., Ito T., Kamata H., Suzuki K.2018. Is bovine protothecal mastitis related to persistent infection in intestine? J. Vet. Med. Sci. 80: 950–952. doi: 10.1292/jvms.17-0710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lerche M.1952. Eine durch Algen (Prototheca) hervorgerufene Mastitis der Kuh. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 65: 64–69 (in German). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marques S., Huss V. A., Pfisterer K., Grosse C., Thompson G.2015. Internal transcribed spacer sequence-based rapid molecular identification of Prototheca zopfii and Prototheca blaschkeae directly from milk of infected cows. J. Dairy Sci. 98: 3001–3009. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-9271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Möller A., Truyen U., Roesler U.2007. Prototheca zopfii genotype 2: the causative agent of bovine protothecal mastitis? Vet. Microbiol. 120: 370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morandi S., Cremonesi P., Capra E., Silvetti T., Decimo M., Bianchini V., Alves A. C., Vargas A. C., Costa G. M., Ribeiro M. G., Brasca M.2016. Molecular typing and differences in biofilm formation and antibiotic susceptibilities among Prototheca strains isolated in Italy and Brazil. J. Dairy Sci. 99: 6436–6445. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-10900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onozaki M., Makimura K., Satoh K., Hasegawa A.2013. Detection and identification of genotypes of Prototheca zopfii in clinical samples by quantitative PCR analysis. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 66: 383–390. doi: 10.7883/yoken.66.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osumi T., Kishimoto Y., Kano R., Maruyama H., Onozaki M., Makimura K., Ito T., Matsubara K., Hasegawa A.2008. Prototheca zopfii genotypes isolated from cow barns and bovine mastitis in Japan. Vet. Microbiol. 131: 419–423. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pore R. S.1973. Selective medium for the isolation of Prototheca. Appl. Microbiol. 26: 648–649. doi: 10.1128/am.26.4.648-649.1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricchi M., Goretti M., Branda E., Cammi G., Garbarino C. A., Turchetti B., Moroni P., Arrigoni N., Buzzini P.2010. Molecular characterization of Prototheca strains isolated from Italian dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 93: 4625–4631. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roesler U., Scholz H., Hensel A.2001. Immunodiagnostic identification of dairy cows infected with Prototheca zopfii at various clinical stages and discrimination between infected and uninfected cows. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39: 539–543. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.2.539-543.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roesler U., Scholz H., Hensel A.2003. Emended phenotypic characterization of Prototheca zopfii: a proposal for three biotypes and standards for their identification. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53: 1195–1199. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02556-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roesler U., Möller A., Hensel A., Baumann D., Truyen U.2006. Diversity within the current algal species Prototheca zopfii: a proposal for two Prototheca zopfii genotypes and description of a novel species, Prototheca blaschkeae sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56: 1419–1425. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63892-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shahid M., Ali T., Zhang L., Hou R., Zhang S., Ding L., Han D., Deng Z., Rahman A., Han B.2016. Characterization of Prototheca zopfii genotypes isolated from cases of bovine mastitis and cow barns in China. Mycopathologia 181: 185–195. doi: 10.1007/s11046-015-9951-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shao Y., Lu N., Wu Z., Cai C., Wang S., Zhang L. L., Zhou F., Xiao S., Liu L., Zeng X., Zheng H., Yang C., Zhao Z., Zhao G., Zhou J. Q., Xue X., Qin Z.2018. Creating a functional single-chromosome yeast. Nature 560: 331–335. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0382-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]