Abstract

In 2016, the Children’s Commissioner for England reported that the most frequent provision for young carers (YCs) comes from dedicated YC services. This study formed one part of a three-year evaluation of support for YCs and their families provided by the Hampshire YCs Alliance (HYCA), a county-wide collaboration of ten YC services in the UK. It set out to explore the following primary questions; (a) what are the most important changes that the YC services made to YCs and their families? (b) what is it about the services that creates those changes? Semi-structured interviews were carried out in 2017, with YCs aged 9–17 (n = 8), their parents (n = 5), HYCA staff (n = 6) and professionals from other stakeholder organisations (n = 5) and a thematic analysis was undertaken. Reflecting previous research that YCs and their families have a broad range of needs, findings also reveal how YC services support them through a diverse range of interventions. Support led to a diverse range of positive changes for YCs and their families. A number of service features that facilitate change for YCs, as well as ‘key dynamics’ important in facilitating change were identified. These findings have led to a conceptual framework of how YC services facilitate change for YCs and are important for understanding the impact these dedicated services can make to the lives of YCs and how they facilitate change. Together they have implications for the development and commissioning of interventions for YCs and families and how service providers promote their support provision.

Keywords: Young carers, Qualitative evaluation, Impact, Intervention and support, Health and wellbeing

The National Policy Perspective

In England, the implementation of the Children and Families Act 2014 (HM Government (2014a) gave all YCs under the age of 18 the right to an assessment of their needs. This is a responsibility of the local authority. The legislation also placed a duty on local authorities in England to “take reasonable steps to identify the extent to which there are YCs within their area who have needs for support” HM Government (2014a). Moreover, the Children and Families Act 2014, together with the Care Act 2014 HM Government (2014b) set out a preventative focus on supporting children through a ‘whole family approach’ (Department for Health, 2014).

Dedicated Support for YCs in England

The most frequent support provision for YCs provided by local authorities (67%) in England is a referral to a YC service (Children’s Commissioner for England, 2016). These dedicated support groups (or ‘projects’) provide YCs with a break from their caring responsibilities and offer a range of support which provides opportunities for these children and young people to socialise; have fun; meet others with similar experiences; talk about their concerns; receive information, receive advice and advocacy and provide support for parents (e.g., Aldridge et al., 2016). Although “YCs and their families have access to a range of different health, social care and educational support services” (Aldridge et al., 2016, p.6), research by the Children’s Commissioner for England indicated that “the emphasis on identification and assessment in legislation may lead to support for young carers being overlooked” (Children’s Commissioner for England, 2016, p.5) and that approximately 80% of YCs may not be receiving support from their local authority (Children’s Commissioner for England, 2016). However, despite the fact that many may not be receiving support, the UK remains ahead of other countries with awareness and policy responses for YCs and their families (Leu & Becker, 2016) with the existence of dedicated YC projects undoubtedly playing a significant role. Around a decade ago, according to Becker (as cited in Stamatopoulos, 2016), the number of YC projects in the UK had grown to more than 350. The current number of dedicated YC services in the UK may have reduced in recent years although a definitive number appears not to be known (partly due to there being various programmes and other support for young carers). However the number still remains at over 260 services (Leadbitter, H and Morgan, V, personal communications, 2020).

The Hampshire Young Carers Alliance (HYCA)

HYCA is an alliance of ten YC projects within the English county of Hampshire. The projects differ in capacity and composition. Some are local charities working specifically for YCs, whereas others form part of broader charitable services with broader remits and one is a national charity for supporting children more generally. Originally composed of five YC projects, the Alliance was formed around 2005 in order for the individual services to work closer together, share good practice and resources, to develop a single county-wide voice and to advocate and campaign for YCs within the county. HYCA projects are currently funded by a broad range of funding streams, including funding from the local authority. As has taken place nationally over the last ten to fifteen years, some of the HYCA projects have complemented their general offer of respite activities through clubs and trips (which have historically been common to most YC services), with work within schools and a ‘whole family approach’ to supporting YCs and their families. For some of the HYCA projects this has involved employing specific staff to work with families and staff to provide targeted work within schools. In 2017, HYCA projects were in contact with 1856 YCs, actively providing support to 1139 YCs (including 610 within schools) and supporting 952 families.

In 2016, HYCA was awarded funding from The Big Lottery in order to roll out and embed a previously developed ‘3-pronged’ support model (offering respite activities, family support and support for YCs in schools) to bring about a more consistent county-wide service across the ten districts where the projects operated. Using an allocation of this funding, HYCA commissioned the University of Winchester to undertake an independent evaluation of the work of the Alliance over the three year period from September 2016 to August 2019. This current study, carried out between December 2016 and August 2017, was undertaken as a first stage of this evaluation.

Methods

The primary study aims were to explore (a) what are the most important changes that the YC services made to YCs and their families and (b) what it is about the services that creates those changes? A total of (n = 24) semi-structured interviews were carried out between January and March 2017 with three different types of participants; YCs aged 9–17 (n = 8), their parents (n = 5), HYCA staff (n = 6) and professionals from other stakeholder organisations in contact with one of the ten local projects (n = 5).

Questions primarily explored what participants considered to be the most important changes that the YC projects bring about for YCs and their families and what it is about the projects that made these changes. Additional questions explored the support needs of YCs and families.

On average the interviews lasted 31 min (ranging from 20 to 60 min), with 21 of the interviews being in the range of 20–40 min. Interviews were recorded and then fully transcribed, before being analysed thematically using three levels of coding.

Sorting Exercises

Each interview was preceded by two short sorting exercises where participants were asked to rank in importance two different sets of descriptors; (a) different HYCA interventions and (b) statements about how different interventions help YCs and families. This exercise was carried out for two reasons. Firstly, as an ‘icebreaker’ to set participants at ease before the main semi-structured interview and secondly as a way of reminding participants about the range of support the projects provided.

Participants

Participants represented nine of the ten HYCA services. Five of the projects were represented by a parent participant (all were mothers) with three of the mothers being the person with care needs. Of the five professionals from the stakeholder services, three were from social care services and two from schools. As far as possible, YCs were selected in a purposeful way in order to have representation from YCs with different characteristics (project; age; gender; duration of support; support type and who they cared for) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants

| Participants | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Young carers | 8 |

| Parents of young carers | 5 |

| HYCA young carer service (project) managers (staff) | 6 |

| Professionals from other organisations that had contact with one of the local young carer services | 5 |

| Total | 24 |

Ethical Approval and Consent

Ethical approval was granted under the Research and Knowledge Exchange ethics procedures of the University of Winchester and informed, written consent was obtained from participants. From YCs, informed verbal consent was obtained in addition to informed parental written consent. Principles of confidentiality were upheld.

Strengths and Limitations

Limitations of the study need to be recognised and considered. Firstly, since the YC services acted as gatekeepers for the YCs and parents (and facilitated contact with the professionals who participated in the interviews), a random sampling of participants was not possible. Although this is a common practice with this type of research it is potentially problematic since the YC services might be identifying only participants who are known to positively engage with their service and be available to participate. This therefore may result in interviewing participants who are more likely to respond positively to interview questions.

One particular strength of the study is that four different types of participant were interviewed. This provides four different perspectives (data triangulation) as well as a more comprehensive set of findings (Noble & Smith, 2015). A second strength was that ten different services were included which again provided a breadth of perspectives.

Results

What YCs Need

Reflecting previous research (e.g., Aldridge & Becker, 1993; Aldridge et al., 2016; Mcandrew et al., 2012), the YCs reported a wide range of different needs reflecting their individual circumstances. These needs fell under four categories; (a) emotional support, (b) time out and opportunities to relax, socialise and make friends (c) support with and understanding of their caring role and (d) knowing they were not alone in being a YC.

Emotional Support

YCs reported needing emotional support to help them deal with anger, stress or with “feeling down”. One YC stated “I think the emotional side of it, I can't really deal with seeing my mum in pain so that bit I need support on”. This was reflected also by the other participants (HYCA staff, stakeholder professionals and parents) who all thought YCs needed to have someone outside the family to talk to, for example, as one parent said, “I can talk to our son a lot, but I do think it helps that there’s somebody outside of the unit that can help and talk to him as well and give their view on things as well”.

Time Out and Opportunities to Relax, Socialise and Make Friends

All participants felt that YCs needed time out from their family situations and caring roles in order to have free time to relax, socialise and experience new activities. One YC reported that “I think the most support that I think would be good, would be just relaxing and getting free time to do what we need to do”, whilst another, stated “getting a bit of a break I guess, it can be a bit overwhelming at home, so coming here [their YC project] it's a bit more sort of chilled”. The importance of being able to make friends and having friendships was strongly emphasised. One parent felt that their child needed “just like building friendships up really… so it's just enabling them to have more, more social time really” and similarly one YC stated that what they needed was “probably like being, like getting friends, cos sometimes I would like try and make friends but it doesn't always work”.

Support with and Understanding of Their Caring Role

The third category of support need related to the YC’s caring role and fell into two camps. Firstly, the need for support with the caring role itself was briefly reported, with one YC expressing this need as knowing “how to care for them. So I'm making sure that I'm doing everything right and making sure that they're happy as well”. A couple of YCs discussed needing to acquire life skills including skills for dealing with money. Some participants also felt it was important for YCs to better understand the condition of their family member and to manage their caring roles alongside their education.

Knowing they were not Alone in Being a YC

Participants commonly reported that YCs needed an awareness that they were “not the only ones” and that there were other young people who were in similar situations to themselves. One YC expressed it this way, “because it's knowing that you're not alone that you're not the only one who's going through the same situation on a day-to-day basis” and one parent put it like this, “and it’s just nice for him to have somewhere to come with other children and to know that he’s not the only one cos I think at times he did feel isolated and felt you know, it was difficult to cope with things at times”.

What Families Need

Families, like the YCs were also found to have a diverse range of needs, although the parents themselves were less clear in articulating these. Support staff were the most consistent in stating that families needed a wider support network, including information about support available locally and being signposted to it. Both YCs and some professionals reported that families needed support with family relationships and managing situations better. One professional stated “I think they need the support with, so to keep together as a family unit”.

The Support Interventions

Interventions to Support YCs Directly

Through a combination of individual support and group work, the projects support YCs through a package of support interventions aimed at providing emotional support, respite from caring and opportunities to meet others in similar situations, as well as opportunities to develop new skills and experience new activities. Projects aimed to take a preventative approach.

With varying frequency according to their capacity, projects run both trips and young carer ‘clubs’ or ‘groups’. Clubs and activity days offer a mix of activities such as cooking, sports or crafts; eating together as a group; a forum to share experiences and have group discussions, and free time to relax and ‘chill out’ with peers through for example, playing pool, table football, or table top games. One project had established a ‘YC Choir’. YCs can also access support in school. The majority of projects employed staff to work within both primary and secondary schools, run ‘drop-in’ sessions during lunch times, or support students individually. One YC reported that their project gave them information that supported them as a YC.

Interventions to Support Families

In order to improve the situation for YCs, the projects also aim to provide a ‘whole family approach’. The majority of projects achieve this through a dedicated role of ‘Family Support Worker’ which enables them to support families in a number of different ways, such as ‘home-visits’, referring and signposting to other services, and providing direct support and advice to parents on parenting and family relational issues.

Projects commonly initiate wider support for families by working collaboratively with other services. Support for families had been triggered for example, from adult’s and children’s social care, local housing associations and services providing parenting courses. Projects work flexibly and creatively in order to source and initiate other support, as illustrated by one parent, ‘‘if they couldn't support me, they would find somebody else that would be able to do it, they wouldn't just go ‘Oh no we can't support you with that’. They would find somebody that could support me with that, make sure that I felt comfortable with that”.

Projects provide support for families with housing and accommodation issues in very practical ways (such as clearing a house) and by initiating support from other agencies to help families with their rent, or with changing and modifying accommodation and acquiring vital furniture. Projects have also helped families with their finances by informing them of benefits they are entitled to and practically with financial documentation.

In addition, some projects provide activities and trips for the whole family to enable the family unit to share experiences and have fun together. Activities have included family trips to a fireworks display, a family picnic and swim and a Christmas gala. Some projects run coffee mornings to enable parents to meet others in similar situations, reduce their isolation and find mutual support.

What Projects have Changed for YCs: Positive Changes for YCs

The interventions by the YC projects led to a diverse range of positive changes for YCs at home, with their schooling and with their socialisation. As one parent put it, “the positives that we’ve seen at home and at school I think really, the changes that we’ve seen, it’s going in the right direction. We’re seeing progress if you like. We’re not stuck in the same place we were you know, six months ago, we have some positive changes”.

Being able to Relax and Reducing Stress

The most common change cited by YCs was being able to relax and de-stress, since projects gave them opportunities to relax, have space away from their caring role and to feel supported. This was highlighted simply by one YC: “it's definitely helped with stress, I mean being at home all the time is quite stressful, so getting a break is quite relaxing”. Another YC reported, “before this group I stressed really badly, like I’m stressing 24/7, but now I’ve come here I’m not as stressed. I know that there’s always someone out there that can help me if I need it”.

YCs make Friends and Develop Social Skills

Being able to meet and make new friends with others with caring responsibilities was also commonly identified by all types of participant as being very important for YCs. Projects provide the space for YCs to socialise, and in contrast to other peers who may not understand the challenges that YCs face, the YCs attending the projects had a common understanding of what it is like to be a YC which seemed to help facilitate friendships. This is illustrated by one YC: “All together I've made new friends definitely. I've met new people who share similar problems and different problems. I mean not everyone has disabled parents”.

Several YCs talked about how attending their project had helped them develop their own social skills, including increasing their patience, being able to be a ‘good sport’ and developing the ability to ignore others, if for example, someone was ‘being mean’ to them.

Improvements in School

For some YCs projects also led to improvements in school, or with their schooling. This was for some as a consequence of joining their project and being able to relax and not worry as much about the person they cared for. Parents and YCs themselves reported that support led to YCs becoming calmer and being less stressed. One YC expressed it like this: “If this wasn’t here I wouldn’t like have no support and I’d like always feel stressed and angry and upset and like, I wouldn’t have support in school and so the teachers would…I’d be getting detentions all the time and stuff like that”, whilst one parent reported that “year four was challenging and year five, since he’s started, he’s much calmer. Year five has been a lot better. And I do think coming here does help”. Furthermore, one YC reported that their exam grades had improved, attributing this to the revision they had done with others at their YC club.

Internal Changes

The projects were also found to bring about more internal changes for the YCs. These changes related to how the YCs felt, their confidence and how they perceived things:

How YCs Feel

Being part of and attending the YC projects also helped improve how YCs felt. Several YCs reported that the fun activities they took part in gave them something fun to do and made them feel happier, and parents similarly reported improvements in how their children felt when attending the groups. One YC expressed it this way: “Well before I was quite unhappy because I was always busy and stressing at school and stuff, but being here I've noticed that quite a big change in emotions as well. But for good reasons, because made friends, had a laugh and done some activities with them”.

Participants reported how the projects made YCs feel better about themselves in other ways and used terms such as ‘special’, ‘valued’ and ‘normal’ to describe these positive changes. One parent stated, “I don't know whether it's the atmosphere, the people, I don't know what it is. I think you feel special coming to young carers, that sounds silly, but it's good to celebrate, I'm really, [sic] cos they are important and you know, they do an amazing job”. One professional described in this way: “they feel valued when they go there and you know, yeah that's about it I think” and a project staff member in this way: ‘It just gives them a chance to be themselves and to, I don’t want to say for them, but to feel more normal”.

Increased General Confidence

Increased general confidence in YCs as a result of attending their project was reported by parents, project staff and YCs themselves which enabled them to take part in activities and helped some to speak out about their caring roles.

Gaining Understanding and New Perspectives about Their Situation and Themselves as Carers

A further common change or ‘set of changes’ that was clearly very important for YCs came from meeting other YCs in similar situations, which transformed how they understood and perceived their own situation as a YC:

Knowing they are not alone in Being a YC

One significant change highlighted by several parents and reflected by project staff and professionals, was that the groups enabled YCs to know that they were ‘not alone’ in being a YC. By meeting other children in similar situations they did not feel they were unique in having caring responsibilities. For some YCs, joining their project was the first time they had met other young people who were carers—and this was important to them. One YC spoke about meeting others who went to the same school as they did and who they had not previously known was a YC. The value of meeting other YCs is illustrated clearly by one YC: “Because it's knowing that you're not alone, that you're not the only one who's going through the same situation on a day-to-day basis” and similarly by a parent: “Knowing that they're not the only ones, it is knowing. To begin with my children thought that they were the only ones so yeah, them knowing that they're not the only ones there, and that there's other people the same as them, and they can get on and they can talk to other people and stuff”.

I’m a Young Carer—but it’s OK!

Another important change in perception highlighted by staff, professionals and parents was that the projects—by introducing YCs to each other—helped them to feel that it was ‘OK’ to be a YC. One parent expressed this way: “But yeah, I try and make it more of a positive thing and he's very proud to come. He loves coming and he's the first one to show off and say “I'm a young carer” and when we get into places well you know, he'll say I'm disabled, “I'm a carer yeah, I'm a young carer, I go to [YC project]”. So he's very proud of it, he wears it almost like a badge”. It was suggested by one professional the realisation that it was ‘OK to be a young carer’ was foundational, and important in reassuring YCs that “no one's going to take [them] away”. Projects ‘gave them a licence’ to be a YC and to feel comfortable about being a carer.

A Greater Understanding and Confidence about Their Caring Role and What to Expect

Being part of a project helped change the perception that YCs held of their caring roles. Some described how seeing others in similar circumstances to their own, seeing them cope, talking with them and learning about their experiences, had helped them gain fresh insight and confidence about their specific family circumstances and in their own capabilities to care for family members. This is expressed by one YC: “I think I'm more confident about my mum's disability. When I was younger, I didn't officially understand it, and now I think because there are more people who have shared similar experiences, I can understand like and what to expect, or how to deal with these problems because they've experienced the same sort of thing, maybe before me, so I can see what might be coming, which is good”. Another YC highlighted how information and support helped them: “When I come here, I get more support and information of like what to do and how to control stuff”.

What Projects have Changed for Families: Positive Changes for Families

Families also experienced a diverse range of positive changes as a result of project support. Parents themselves benefitted directly from knowing their child was receiving support. They were pleased and reassured that their child was meeting other YCs and having a break from their caring roles, and being able to socialise and have fun. This is illustrated by one parent: “One of the biggest changes that have made for me is seeing a smile on my children's face, which means there's a smile on my face”.

Projects help to Improve Family Relations and have Fun Together

Both YCs and parents credited the projects for improving and stabilising family relations, calming their households, and keeping, or bringing their family closer together. Parents felt that when their children had respite at the clubs and on trips, they became calmer, which “calms the whole house down and breaks things up, so it’s more manageable”. One YC stated that the biggest change the service had made to their family, was that there were “not as many arguments” and when asked how else the project helped them and their family, one YC replied: “I don't know, they've just brought us together more. Yeah, brought us together”. Through the projects, families simply had opportunities to have fun together as a family unit which as some YCs indicated, was often not usually possible due to their family situation.

Access to Further Support and Parents Knowing there is Support to Turn to

Projects enabled families to access a range of additional support interventions—either directly from projects themselves (e.g., someone to talk to over the phone), or from other services (e.g., an accommodation agency) facilitated by the projects, or indirectly for example from being referred to the Early Help Hub.

The direct support that parents received from projects also enabled them to move from a place where they had felt alone, to ‘knowing’ that they were not alone and ‘knowing’ that there was support out there for them, if they needed it. This was expressed simply by one parent: “It’s just knowing that we're not alone”.’ This assurance of a support network for them and their family and access to someone who they could talk to was highly valued by parents, as illustrated: “It's knowing that they're at the end of the phone. So if I am having a bad day, they're always willing to, to talk to me, things and like there's the Facebook page so I can message them privately, so you know at some point they can, they will respond or signpost me to the right people if, if it's something out of their remit, sort of thing, so yeah it's been you know, valuable all the way through”.

The Important Features of the YC Services for Facilitating Change

A number of different features of the YC projects were identified as being important for helping to bring about the changes. These relate to (a) how projects are staffed (b) how they operate and (c) the environment that projects create:

A: How Projects are Staffed

YCs and parents strongly emphasised the significant and positive role played by project staff who were viewed as extremely helpful and supportive to both YCs and parents. Participants stressed the importance of the character of staff and described them for example as being “really nice”, “caring”, “kind” and having “compassion” and “loyalty”. How staff engaged with the YCs was also highlighted as playing an important role as well as their personalities which were described as “fun” and “laid back”. It was clear that the staff brought a positivity to the groups which encouraged and enthused YCs to take part and enjoy activities. One parent stated, “I just think that they're an amazing bunch of people and they're always, they're supportive. If I walked in today and say I've got this problem, that problem and they'd say ‘Right well, let's try and sort it. Can I help?’” and one YC expressed their view of the staff simply as “they're amazing, they really are yeah”.

Staff Understand YCs and Families

The skills, knowledge and experience that staff brought to the role were also clearly valued by YCs and parents, but particularly by professionals. It was recognised that since projects provided dedicated support for YCs, staff had a deep understanding of YC issues – their needs and their families’ needs. Consequently, YCs and parents had confidence in staff and felt comfortable and safe being supported by them. One parent put it like this: “Again it's someone that knows, and they might have been through those things with other people, and I haven't been there, so it's always good to have someone with more experience than I have”.

B: How Projects Operate

Projects are Relational

Another key feature of projects is their relational nature. Relationships are built not only between the YCs, but the project staff also had time to get to know the YCs and families and build positive relationships with them. This in turn supports engagement with the projects. Two parents gave clear examples of this: “My daughter has anxiety issues and if she didn't have that one-to-one relationship with them [staff], she wouldn't feel comfortable and she wouldn't want to come, so which meant that she wouldn't get a break from me”; “I know that they're being well looked after. They [staff] get to know the children very well so if, they can pick up very easily if there's anything wrong. I know it's confidential as well, it's just having yeah, they've enabled us to build up trust in them which is quite difficult to gain sometimes”.

Consistent Support

The consistent support that projects provided over a number of years and the consistency of staff was identified as helpful in building the confidence of families and in the ability of projects to help them. This also helped enable staff to get to know the young people and build relationships with them. Furthermore, the consistency of support groups throughout the year and especially throughout the school holiday periods was further recognised.

A Diverse Range of Early Intervention and Support Initiatives

Participants highlighted the importance of the diverse and unique range of interventions and opportunities offered by projects to meet the diverse needs of YCs as well as their early intervention approach.

Specialist and Tailored Support

Finally, there was both recognition of the importance of projects providing specialist and tailored support for YCs (i.e. not generic young people’s support) and how projects targeted the support needs of individuals in responsive way, through bespoke activities. This ability of at least some of the services to be responsive, flexible and to offer bespoke and creative interventions, targeted at the needs of individual groups of YCs, was summed up by one project Manager: “If they have any particular issues then we can do work on that, so self-harming or anything else that’s going on. Focus sort of focus groups, we got sexual health to come in to talk to the kids because we had quite a few who were struggling with that, so whatever the need is, we can tailor it and pretty much do anything…”.

C: The Environment that Projects Create

The environment created by the projects was clearly another significant factor in facilitating the positive changes facilitated by projects:

A Safe, Accepting and Supportive Environment

All the YCs and parents, staff and professionals, agreed that the groups were somewhere safe and supportive for YCs. One reason for this was that projects had guidelines in place and group contracts were developed to ensure confidentiality. One YC (and some project staff) reported that there was never any bullying in their group.

Being with other Young People who Understand

The value of YCs being with others similar situations who ‘understand’ or ‘know’ each other’s background was commonly reported. Simply knowing that others within the group understand seems to be extremely important for the YCs and helps them to feel comfortable, relax, make friends and talk to each other about their lives, without the fear of being judged. As one YC stated: “The carers themselves, because we all doing a caring role, being able to relax together and just having a break. All in all, knowing that we have sort of similar roles, it's quite nice to know”.

Services Build Trust with YCs and Families

The trusting atmosphere that the projects engendered was another important factor. YCs felt they could open up to others with confidence that what they said would not be discussed outside. This is expressed clearly by one YC: “Knowing that everything's confidential, knowing that people aren't going to judge on you and judge on the situation that you're in with your family.’ Similarly, the importance of trust built up between the services and families was also commonly recognised”.

A Balance of Structure and Freedom

YCs valued the fact that the club activities were “not forced” on them, but were offered as a choice. The importance of achieving a ‘balance’, or ‘combination’ of structure and free time within the sessions; where YCs could talk about issues, simply ‘be children’ and have fun with peers, was highlighted by project staff.

How do the HYCA Services help Facilitate Change for YCs?

In addition to these important key features of YC projects above, a small number of factors or ‘key dynamics’ were found to be particularly significant in helping to bring about the positive changes experienced by YCs.

Talking to others Helps YCs

As well as being something that ‘has changed’ for YCs, ‘being able to talk to someone’ outside of the family about issues, concerns, or things they were struggling with, was commonly highlighted as extremely important for the YCs and a ‘key dynamic’ for facilitating change. Talking with others encompassed talking with peers, talking with staff and talking in structured groups. Different terms were used by participants to describe the benefits of talking including, “having emotional support”, “offloading”, “having an outlet”, “sharing” and “having a listening ear”. Even simply knowing that they can talk if needed was helpful, as expressed by one YC: “It's just knowing that you can talk about that if you want to and not having to hesitate and divert around the conversation”.

Having Mutual Support

The majority of YCs reported the benefit of mutual support within their projects that they experienced with other young people. This was often articulated by YCs as being able to talk to others about problems, but it also included supporting each other with revision and gaining ideas that supported them in their own caring role. Project managers discussed how YCs looked out for and supported each other and the close bonds they formed.

Being a Child or Young Person, Having Fun and Having Something to Look Forward to

Participants highlighted the value of how projects provided YCs with opportunities to have a break from, and to forget about their caring role. Projects enabled YCs to take part in activities and to simply ‘be children’ or young people and have fun. As expressed by one professional: “By accessing YCs [the project] they have had opportunity to be a young person, undertake all those things that young people do and to just shelve the responsibilities as a carer for some time”. Finally, the value of projects enabling YCs to have something to look forward to was emphasised, as illustrated by one YC: “It's a bit of a change. It's something to look forward to, something new and exciting usually”.

Discussion

The main focus of the study was to explore what were the most important changes that the YC services made to YCs and their families and what it is about the services that creates those changes. Interviews initially also explored the support needs of the YCs and families.

The Needs of YCs and Families

YCs were found to have the following broad range of needs that fell under four categories; (a) emotional support, (b) time out and opportunities to relax, socialise and make friends (c) support with and understanding of their caring role and (d) knowing they were not alone in being a YC. Similarly, families also have a range of needs, although parents tended to focus primarily on their children’s needs; for them it was important to know their children were being supported, had opportunities to forget about their caring roles and were able to ‘be children’.

The diverse needs or ‘support needs’ of YCs identified in the study clearly reflect that of previous research. Aldridge et al. (2016) for example found that almost all the YCs and families in their study agreed that emotional and social support as well as practical support and information would be of value. This range of needs is to be expected since the YCs are not a homogenous group—they are different ages, have different caring roles and different backgrounds, and have been caring and accessing support from the projects for varying lengths of time. It is also likely as (Aldridge et al., 2016) points out that support needs change over time. As Joseph et al., (2019, p.11) assert, (based on their concentric circles conceptualization of caring) “that the policy targets for all young people will not be the same”. The ongoing need for effective and timely needs assessments (Frank & Mclarnon, 2008) is therefore evident as well as a support offer that responds to changing needs over time.

A Diverse Range of Support

The services were found to offer a diverse range of support interventions for YCs, providing emotional support, respite from caring, opportunities to meet others in similar situations, opportunities to develop new skills and experience new activities and access support in schools. Services provide support for families through a ‘whole family approach’ which includes initiating further support through other agencies.

This diverse interventions approach provides a logical response to the above findings that YCs accessing the projects have a range of needs. It also aligns with the propositions of others for multifaceted policy and support responses. Joseph et al. (2019) for example, posit a model of caring using three concentric circles that relate to differing intensities of caring. Young people from each of these groups they propose, have their own distinctive needs. Having recognised this, they state that “policy targets can be more nuanced and responsive to the needs in families” (Joseph et al., 2019, p.7). They also advocate the analytical framework proposed by Purcal et al. (2012) that categorises YC support services in order to provide a structure for assessing their effectiveness. Their framework groups the goals of YC support into (a) assisting young people who provide care; (b) mitigating the care-giving responsibility; and (c) preventing the entrenchment of a young person's caring role. The interventions delivered by the projects within this study clearly aim to meet all three of these goals. Matzka and Nagl-Cupal (2020) identified two sets of psychosocial resources used by YCs to respond to the care burden (i.e. personal resources and interpersonal resources). Again the project interventions in this present study support both these types of resources, for example by enabling leisure time (personal resource) and fostering meaningful friendships (interpersonal resource) including promoting cohesion within the nuclear family (Matzka & Nagl-Cupal, 2020).

Positive Changes from Accessing Projects

A diverse range of positive changes took place for both YCs and families, with YCs themselves experiencing positive changes at home, at school and in their social life. Knowing other children with caring responsibilities, making friends and having regular groups to attend, helped reduce isolation. YCs felt more relaxed, less stressed and happier. They gained understanding, new perspectives and were more confident about being a YC and about their family situation. Families felt better from knowing that the YC services were there to support them if needed, as well as from the additional support that is facilitated by the services. Family relations are improved and parents gain comfort from knowing their children are supported and able to socialise.

This identification of a diverse range of positive changes for YCs accessing these projects is significant considering these dedicated services are the YCs primary source of support for YCs (Children’s Commissioner for England, 2016). Indeed, the value of dedicated YC services has been consistently found in studies (e.g., Aldridge et al., (2016); Dearden & Becker, 2000; Price & Jarvis, 2017). Moreover, many of the positive changes reflect the diverse range of needs of YCs and their families, which implies that this type of project support is indeed effective.

Key Project Features

A large number of project features were identified that appear to facilitate the positive changes experienced by YCs. These included the diverse range of support interventions; the specialist nature of the services; a safe, accepting and supportive environment; the significant role played by staff; the relational nature of the services; the consistency of the support provided by individual services and the early intervention approach.

What is significant about this finding is the large number of features associated with the projects that appear to be important in enabling their effectiveness and facilitating change. Several of these features stem from the specialised nature YC projects, such as their understanding of YC needs and the skills of staff, as well as being able to provide a forum for YCs to meet others in similar situations. These features should be recognised in the commissioning and development of services, as should the importance of the relational nature of YC projects which previous studies have also identified (e.g., Aldridge et al., 2016; Price & Jarvis, 2017). This holds especially true during times such as experienced in the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Key Dynamics

A small number of factors or ‘key dynamics’ were found to be particularly important in facilitating change for YCs. These were: having mutual support, talking to others, being a child or young person, having fun and having something to look forward to. Again, these have previously been found to be important to YCs (e.g., Aldridge et al., 2016; Barry, 2011; Children’s Commissioner for England, 2016). What is important to recognise here is that there is nothing unusual or exceptional about these dynamics. Indeed, this recognition mirrors the assertion made by (Matzka & Nagl-Cupal, 2020) that what allows YCs and their families to deal with the challenges they face are “basic, yet effective, human adaptational systems that may be cultivated and promoted with systemic support” (p.9). The fact that these dynamics have been identified in this study as being key for facilitating change for YCs, implies that they are not being sufficiently enabled for these young people within other environments such as at home or in school. Mutual support for example, may be enabled at a YC project because of the trust between YCs who understand each other and who feel safe, accepted and supported—whereas in school this may not be the case. Gough and Gulliford (2020) recently identified three factors (perceived self-efficacy, social support and school connectedness) associated with adjustment outcomes for YCs which the findings in the current study resonate with. The ‘key dynamic’ of mutual support in the present study reflects the social support that Gough & Gulliford identified, whilst the finding that YCs gain greater understanding and confidence about their caring role echoes their perceived self-efficacy.

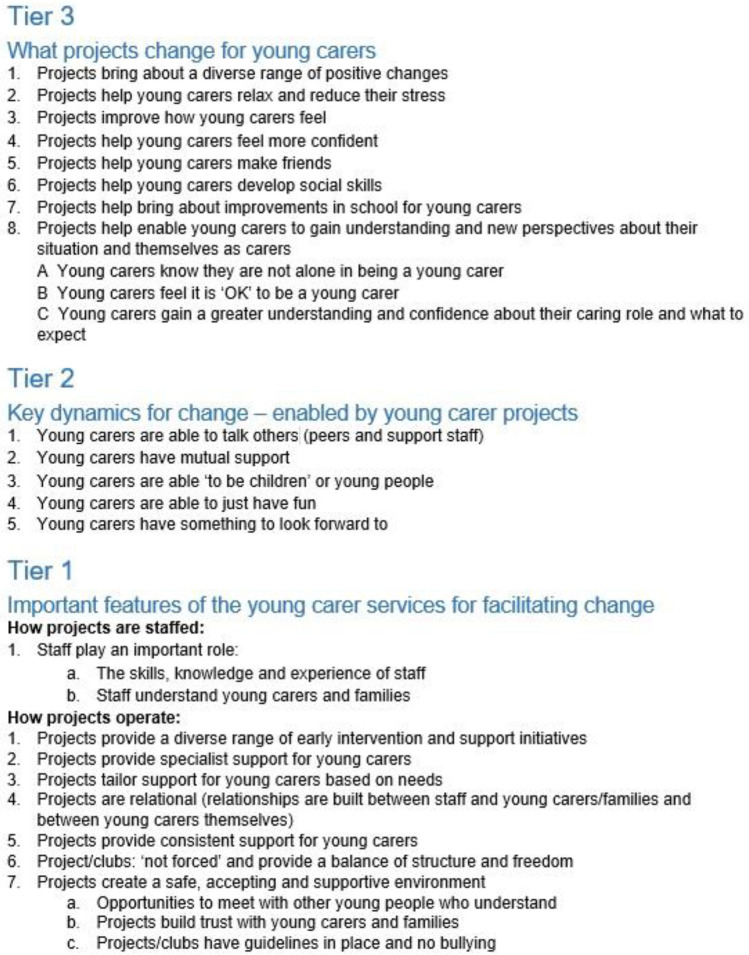

Taken together, these findings have led to a three-tiered conceptual framework (Fig. 1) that attempts to differentiate between the key features of the YC projects (Tier 1) that underpin and enable an environment in which ‘key dynamics’ (Tier 2) are able to bring about positive changes for YCs (Tier 3). This framework that focuses solely on facilitating change for YCs (rather than families), holds potential to be used in the evaluation of support services.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework for how young carer projects support change for young carers

It may well be argued that certain features set out in a particular tier could be placed in another. For example, ‘young carers being able to talk’, or ‘young carers just having fun’ could be viewed as changes in themselves—rather than the dynamic that engenders a change. Conversely, it could be reasoned that ‘young carers gaining new understanding and new perspectives about their caring role’ e.g., know they are not alone in being a YC (identified in the study as a change) might also be a ‘key dynamic’ for change and included in Tier 2. Furthermore, it is not proposed that the lists contained within the framework are comprehensive. They are however the main changes, dynamics and important features of YC services found within the present study. Projects giving information to YCs (e.g., Dearden & Becker, 2000; Price & Jarvis, 2017) or enabling participation (e.g., Phelps, 2017) are examples of additional features that could also be included.

Conclusion

Through a range of interventions, the YC projects bring about a diverse range of positive changes for YCs and families that reflect their diverse needs that were identified. Key features of these projects that are important in enabling these changes and ‘key dynamics’ that facilitate these changes were also identified. Together, these findings are important for understanding the impact and potential that dedicated YC services can make to the lives of YCs and their families. A conceptual framework has been developed to contribute an additional perspective to the existing frameworks that categorise YC support interventions and resources used by YCs to improve their outcomes. This attempts for the first time—as far as the author is aware—to set out and differentiate between the key features of YC projects, the ‘key dynamics’ that engender change and the actual changes experienced by YCs. The findings have implications for the development, commissioning and evaluation of interventions and services for YCs and families and how service providers promote their support provision. The findings also re-emphasise the importance of ongoing refinement of assessment tools to identify the varying needs of YCs and families. Future research should further explore the diverse needs of different YC populations and the different factors that enable services to bring about successful outcomes for YCs.

Funding

This study forms part of a wider evaluation of the Hampshire Young Carers Alliance (HYCA) (2016–2019) funded by the Big Lottery Fund (0010270108).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aldridge J, Becker S. Children who care. Inside the world of young carers. Loughborough University, Young Carers Research Group; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge J, Clay D, Connors C, Day N, Gkiza M. The lives of young carers in England qualitative report to DfE TNS BMRB. Loughborough University, Young Carers Research Group; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barry M. “I realised that i wasn’t alone”: The views and experiences of young carers from a social capital perspective. Journal of Youth Studies. 2011;14(5):523–539. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2010.551112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Commissioner for England. (2016). Young carers: The support provided to young carers in England. Retrieved from http://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/publications/support-provided-young-carers-england

- Dearden C, Becker S. Meeting Young Carers’ Needs: An Evaluation of Sheffield Young Carers Project. Loughborough University, Young Carers Research Group; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2014). Care and support statutory guidance. Retrieved November 15, 2020, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/care-act-statutory-guidance/care-and-support-statutory-guidance

- Frank J, Mclarnon J. Young carers, parents and their families: key principles of practice: Supportive practice guidance for those who work directly with, or commission services for, young carers and their families. The Childrens Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gough G, Gulliford A. Resilience amongst young carers: Investigating protective factors and benefit-finding as perceived by young carers. Educational Psychology in Practice. 2020;00(00):1–21. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2019.1710469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HM Government (2014b): The care act 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2019, from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted

- HM Government (2014a): Children and families act (96: young carers). Retrieved November 15, 2019, from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/6/section/96/enacted

- Joseph S, Sempik J, Leu A, Becker S. Young carers research, practice and policy: An overview and critical perspective on possible future directions. Adolescent Research Review. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s40894-019-00119-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leu A, Becker S. A cross-national and comparative classification of in-country awareness and policy responses to ‘young carers’. Journal of Youth Studies. 2017;20(6):750–762. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2016.1260698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matzka M, Nagl-Cupal M. Psychosocial resources contributing to resilience in Austrian young carers—A study using photo novella. Research in Nursing and Health. 2020;43:1–11. doi: 10.1002/nur.22085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcandrew S, Warne T, Fallon D, Moran P. Young, gifted, and caring: A project narrative of young carers, their mental health, and getting them involved in education, research and practice. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2012;21(1):12–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble H, Smith J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence-Based Nursing. 2015;2015(18):34–35. doi: 10.1136/eb-2015-102054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps D. The voices of young carers in policy and practice. Social Inclusion. 2017;5(3):113–121. doi: 10.17645/si.v5i3.965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Price K, Jarvis A. Evaluation of YES: Young carers’ exceptional stories. Final report 2017. Social Futures Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Purcal C, Hamilton M, Thomson C, Cass B. From assistance to prevention: Categorizing young carer support services in Australia, and international implications. Social Policy and Administration. 2012;46(7):788–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2011.00816.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatopoulos V. Supporting young carers: A qualitative review of young carer services in Canada. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2016;21(2):178–194. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2015.1061568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]